Abstract

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family of genes has been implicated in the clinical development of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). A previous study identified associations between gene expression of VEGF family members in the prefrontal cortex and cognitive performance and AD pathology. This study explored if those associations were also observed in the blood. Consistent with previous observations in brain tissue, higher blood gene expression of placental growth factor (PGF) was associated with a faster rate of memory decline (p=0.04). Higher protein abundance of FMS-related receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (FLT4) in blood was associated with biomarker levels indicative of lower amyloid and tau pathology, opposite the direction observed in brain. Also, higher gene expression of VEGFB in blood was associated with better baseline memory (p=0.008). Notably, we observed that higher gene expression of VEGFB in blood was associated with lower expression of VEGFB in the brain (r=−0.19, p=0.02). Together, these results suggest that the VEGFB, FLT4, and PGF alterations in the AD brain may be detectable in the blood compartment.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, VEGF, blood biomarkers

1. Introduction

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family of signaling proteins are known to be involved in the processes of the growth and maintenance of vascular cells (de Almodovar et al., 2009). The family consists of five genes encoding ligands (VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC, VEGFD, and PGF), 3 receptor genes (FLT1, KDR, and FLT4), and 2 co-receptor genes (NRP1, NRP2). These genes play additional roles in several biological pathways, including the growth and maintenance of neural cells (de Almodovar et al., 2009). Vascular and neural cells grow along similar paths, both appearing to be guided by VEGF proteins (de Almodovar et al., 2009).

In the context of neurodegenerative disease, members of the VEGF family have shown to play a role in neuroprotection (Garcia et al., 2014; Hohman et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2013). Most studies have focused on the role of VEGFA in particular. While VEGFA is the most studied gene in the family, there is mixed evidence on its role in neurodegenerative disease. Some report VEGFA gene expression in blood is associated with reduced cerebral blood flow which contributes to vascular alterations associated with AD (Bennett et al., 2018). However, this conflicts with the protective mechanisms reported when looking at expression within the brain (Hohman et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2020), and when looking at VEGFA levels in serum where levels are lower among AD cases compared to controls (Silva, 2023). The mixed evidence may be due in part to the importance of genetic context (Moore et al., 2020), complex AD biomarker interactions (Hohman et al., 2015), or the counterintuitive role of VEGFA in promoting capillary stalling recently published (Ali, 2022). These conflicting results for only one of the VEGF family members highlight the need to look deeper into peripheral differences across the gene family to better understand the role of the VEGF genes in AD.

When looking in the brain, the family members VEGFB, FLT1, PGF, and FLT4 appear to show the most striking transcriptomic alterations in relation to clinical AD (Mahoney et al., 2019). However, these genes have not been well characterized in the context of aging and AD at the transcript or protein levels in the blood. While changes in the entire VEGF family have been deeply characterized in the brain (Guo et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2013; Miners et al., 2018; Provias & Jeynes, 2014; Tang et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2015), it is not known whether similar associations with AD neuropathology and cognition are also observed in the periphery.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether our group’s previous VEGF prefrontal cortex associations with AD cognition and neuropathology are also observed in the blood (Mahoney et al., 2019). We hypothesize that increases in VEGFB, FLT1, FLT4, and PGF gene and protein expression in whole blood will be associated with a decrease in cognitive performance and an increase in AD neuropathology, as previously observed in the brain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Data were acquired from a cohort study of aging and vascular health. The Vanderbilt Memory & Aging Project (VMAP) collected data from 335 participants beginning in September 2012 enrolling older adults without dementia but enriched for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (n = 132) as previously described (Jefferson et al., 2016). Every 18 months participants complete a physical examination, fasting blood draw, and neuropsychological assessment. A subset of participants underwent lumbar puncture to collect CSF samples (n = 155). Written informed consent was acquired from participants and research was carried out in accordance with Vanderbilt University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols (IRB00000475, ≥6 voting members required for quorum). (https://www.vmacdata.org/vmap)

2.2. Cognitive Measures

Neuropsychological testing included 15 tests covering multiple domains. For the present analysis, we focused on a memory composite that was calculated using item-level data from the California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition (CVLT-II) and the Biber Figure Learning Test (BFLT) including both the learning, recall, and recognition components of each test and a bi-factor modeling approach to account for test-specific effects. Model performance parameters were used for item selection and final bifactor model selection previously separate from the present analysis. The final composite is on a standardized scale with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Given our choice to focus on the memory domain, sensitivity analyses evaluated all significant effect with a composite measure of executive function calculated in a comparable manner incorporating item level data from a letter fluency task (FAS), the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Color–Word Inhibition Test, Tower Test, and Letter–Number Switching Test (Jefferson et al., 2016).

2.3. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers

Blood draw and lumbar puncture were completed at every study visit. For this study we used baseline blood draw and baseline CSF, both of which were acquired on the same day for each participant. Some participants underwent an optional morning fasting lumbar puncture (n=155) at baseline. Out of the 25 mL of CSF collected, 20 mL were immediately mixed and centrifuged. Samples were analyzed using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to determine the levels of Aβ1–42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau (ptau) at threonine 181. Board certified laboratory technicians blinded to clinical information performed sample processing. All specific methods of sample processing were previously characterized (Jefferson et al., 2016).

2.4. Measures of VEGF Gene Expression

Baseline blood samples were obtained in the morning under fasting conditions. Approximately 2.5 mL of whole blood were frozen at −80°C in a PAXgene tube (QIAGEN, 761115) until processed (Jefferson et al., 2016). The VANTAGE Core (Vanderbilt University, TN, USA) performed the RNA extraction, preparation, and RNA sequencing as previously described (Seto, 2022). The QIASymphony RNA Kit (QIAGEN, 931636) was used to extract total RNA from whole blood, and ribosomal RNA and hemoglobin were depleted with the NEBNext Globin and rRNA Depletion Kit (New England BioLabs, Inc., E7750). The NEBNext Ultra Directional Library Prep Kit (New England BioLabs, Inc., E7750) was used to complete library preparation. Sequencing was performed using 150 base pair (bp) paired end reads on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina), with an average of 50 million reads per sample being targeted. QC methods included quantile normalization, removal of principal component outliers, and adjustment for batch effects (Seto, 2022). Sensitivity analyses leveraged RNA sequencing data that was additionally adjusted for a number of covariates, the methods previously described (Seto, 2022). The final data included RNA sequencing data for 325 VMAP participants.

2.5. Measures of VEGF Protein Expression

VEGF receptor protein expression was quantified using a bottom-up proteomics strategy incorporating immunodepletion tandem mass tags, nanoflow liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on 335 VMAP plasma samples at baseline. This strategy used a robust workflow that addresses reproducibility issues of sample preparation in large cohorts (N>100) through quality-controlled automation using a robotic liquid handler (Oliver, 2022). MS spectral information was searched against the Uniprot human reviewed proteome data base (04/02/2021, 79740 sequences) using the Proteome Discoverer (version 2.4; https://www.thermofisher.com). Normalization of the resulting proteomic data adjusted for batch effects, high levels of missingness, and log2 transformation. This quantification yielded measurements for FLT4 and NRP1 in 335 samples.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were completed using R (version 4.1.0; https://www.r-project.org/) and code is available on request from the authors. Significance was set at a priori to α=0.05. Our primary analyses sought to replicate previous associations in the brain using transcriptomics and proteomics in the blood. Corrections for multiple comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni method, resulting in an a priori α=0.0035. Secondarily, we explored all VEGF family members in relation to both cognition and AD biomarker outcomes.

We evaluated associations between VEGF gene expression levels and VEGF protein abundance in whole blood with cross-sectional memory (at the first visit) as well as longitudinally (over the following three visits) with an additional model covarying for baseline performance. Cross-sectional memory associations were evaluated using linear regression covarying for age at first visit and sex. Longitudinal associations were evaluated using mixed effect regression where the outcome was the memory composite score at each visit and longitudinal change was modeled in a linear fashion with a fixed and random effect of both the intercept and slope entered into the model. The model included an interaction term of gene or protein expression x interval, with interval modeled as time in years after first visit. Fixed effects included age at first visit, sex, gene or protein expression level, and interval. The intercept and interval were entered as random effects. The composite memory score was entered as a continuous outcome, reflecting the scores across the four time points. For both cross-sectional and longitudinal models, the predictor and outcome variables were scaled to produce standardized coefficients.

Associations between VEGF gene expression levels and protein abundance, biomarkers of AD pathology, and diagnosis were also evaluated. Associations with continuous outcomes of β-amyloid, total tau, and ptau were analyzed using linear models. A binary logistic regression model was used to analyze gene and protein expression associations with cognitive diagnosis at baseline as a binary categorical outcome. All models co-varied for age at first visit and sex.

Sensitivity analyses evaluated additional technical and confounding variables including vascular risk factors, body mass index, technical covariates, and diagnostic interaction effects.

2.7. Posthoc Analyses: VEGF Correlation in Brain and Blood from GTEx

Pearson correlations between VEGF gene expression levels in whole blood and brain tissues were evaluated for the genes with significant associations to better contextualize the results. RNA sequencing data from 137 participants with both post-mortem blood and brain tissue measurements from the Genotype Tissue Expression Project (GTEx) were used (GTexportal.org; (Lonsdale et al., 2013). Correlation between whole blood and 13 different brain regions with available VEGF measurements were evaluated including the frontal cortex, nucleus accumbens basal ganglia, cerebellum, putamen basal ganglia, substantia nigra, spinal cord, hypothalamus, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellar hemisphere, caudate basal ganglia, anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala.

3. Results

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants were mostly well-educated, between the ages of 50 and 92 years old (mean=73, standard deviation=7.3), and had clinical diagnoses of normal cognition (61%) or MCI (39%). Most participants self-reported to be non-Hispanic White (87%), with fewer participants self-reporting as non-Hispanic black (10%), or either Hispanic White, Asian, or American Indian/Alaska Native (3%).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Clinical Diagnosis | Total (n=335) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Cognition (n=203) | Mild Cognitive Impairment (n=132) | |||

| Age at baseline, yrs | 72.62+/− 7.1 | 73.37 +/− 7.6 | 72.92 +/− 7.3 | 0.360 |

| Education, yrs | 16.40 +/− 2.5 | 15.06 +/− 2.7 | 15.87+/− 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Memory Composite Score | 0.48 +/− 0.8 | −0.75 +/− 0.8 | −0.005+/− 1.0 | <0.001 |

| MOCA Score | 26.79 +/− 2.3 | 23.14 +/− 3.4 | 25.35 +/− 3.3 | <0.001 |

| Male, no. (%) | 124 (61) | 74 (56) | 198 (59) | 0.424 |

| Non-Hispanic White, no. (%) | 177 (87) | 114 (86) | 291 (87) | 0.801 |

| APOE4 Carrier, no. (%) | 56 (28) | 58 (44) | 114 (34) | 0.004 |

Boldface signifies p < 0.05.

3.1. Associations with Cognition and Biomarkers of AD Pathology

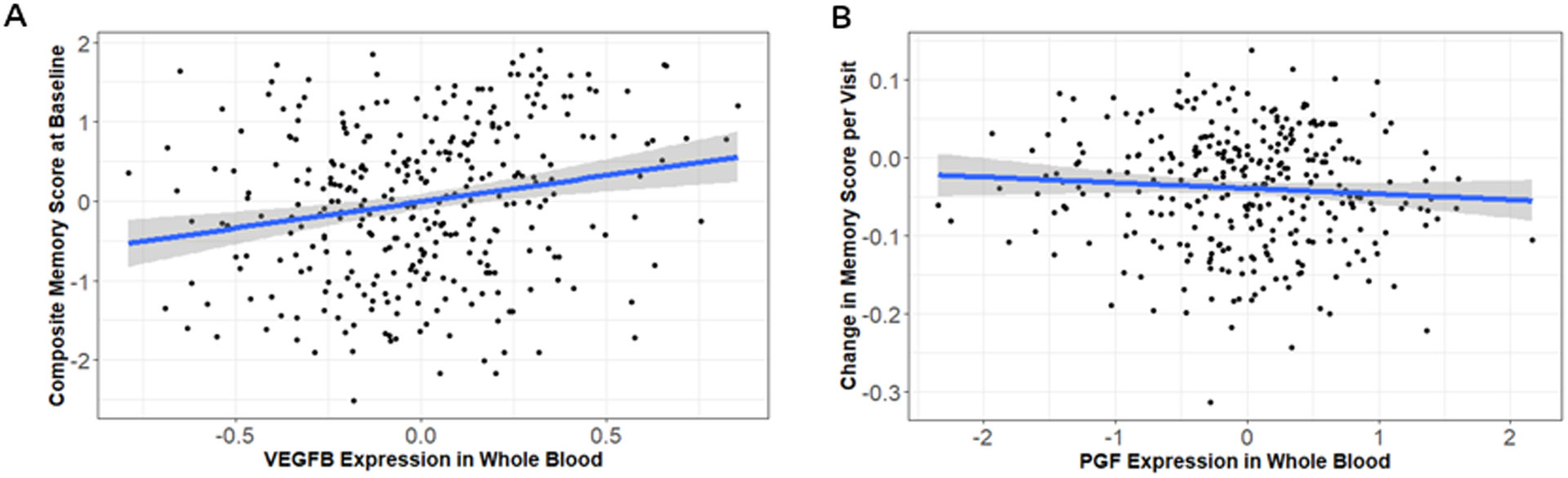

Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with composite memory scores are presented in Table 1. In cross-sectional analyses, higher VEGFB gene expression in whole blood was associated with better cognition (Table 2, Figure 1A, β=0.15, p=0.0075). In longitudinal analyses, higher baseline PGF gene expression in whole blood was associated with a faster rate of memory decline (Table 2, Figure 1B, β=−0.02, p=0.04). PGF results were slightly attenuated when covarying for baseline memory performance (β = −0.015, p=0.08) representing a 6% reduction in the point estimate. The significant memory associations did not extend to executive function. Associations between the VEGF genes and neuropathology were also tested. Results for biomarkers of AD pathology are presented in Table 2. Associations between Aβ42, tau burden, p-tau181 burden, and VEGF gene expression were tested. No significant associations were found between VEGF gene expression and biomarkers of AD pathology (p<0.05). When correcting for multiple comparisons, neither the PGF association with longitudinal memory nor the VEGFB association with baseline memory remained significant.

Table 2.

VEGF Expression and Protein Abundance Associations with Composite Memory Score

| Longitudinal | Cross-Sectional | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | β | SE | P | β | SE | P |

| VEGFA | −0.004 | 0.02 | 0.60 | −0.10 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| VEGFB | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.007 |

| VEGFC | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

| VEGFD | −0.008 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.51 |

| PGF | −0.020 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.008 | 0.08 | 0.89 |

| FLT1 | −0.001 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.68 |

| KDR | −0.007 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.60 |

| FLT4 | −0.010 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.45 |

| NRP1 | −0.010 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.74 |

| NRP2 | −0.007 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.007 | 0.09 | 0.90 |

| Protein | β | SE | P | β | SE | P |

| FLT4 | −0.020 | < −1.0e-S | 0.07 | −0.02 | 2.72e-7 | 0.75 |

| NRP1 | −0.003 | < −1.0e-S | 0.72 | 0.01 | 1.25e-7 | 0.83 |

Boldface signifies P<0.05.

The reported beta coefficients are standardized.

Figure 1. VEGFB and PGF Whole Blood Expression Association with Baseline and Longitudinal Changes in Memory.

Whole blood expression of VEGFB (A) was associated with better memory performance in baseline analyses (β=0.48, p=0.0075). Whole blood expression of PGF (B) was associated with more rapid decline in memory (β=−0.02, p=0.04).

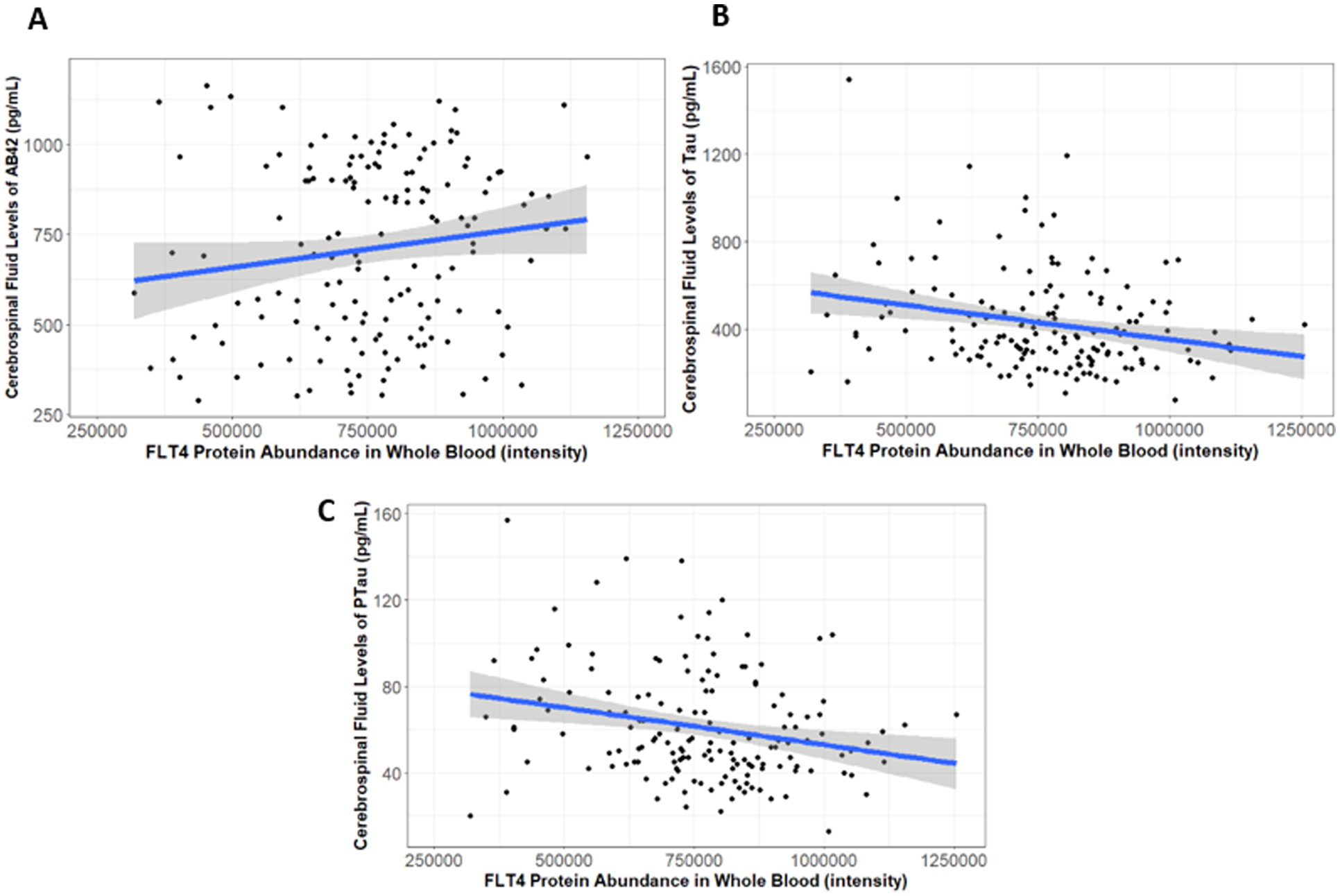

When associations between VEGF protein levels in whole blood and biomarkers of AD pathology were tested, higher abundance of FLT4 in whole blood was associated with higher levels of CSF β-amyloid, indicative of less amyloid-β in the brain (Table 3, Figure 2A, β=0.17, p=0.0420). Similarly, higher abundance of FLT4 in blood was associated with lower levels of tau in CSF (Table 3, Figure 2B, β= −0.25, p=0.0022), and decreased levels of phosphorylated tau in CSF (Table 3, Figure 2C, β=−0.25, p=0.0029), both of which are indicative of lower levels of tau pathology in the brain. Both FLT4 associations with CSF tau and phosphorylated tau passed correction for multiple comparisons. No significant associations were observed between NRP1 protein abundance in blood and biomarkers of AD pathology. No significant associations were found between VEGF family protein abundance and cognition or diagnosis.

Table 3.

VEGF Expression and Protein Abundance Associations with AD Pathology

| B-amyloid | Tau | Ptau | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P |

| VEGFA | −0.03 | 57.50 | 0.75 | −0.09 | 52.86 | 0.27 | −0.11 | 6.05 | 0.20 |

| VEGFB | 0.14 | 67.65 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 62.92 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 7.20 | 0.29 |

| VEGFC | 0.09 | 20.21 | 0.20 | −0.01 | 18.75 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 2.14 | 0.71 |

| VEGFD | −0.01 | 24.85 | 0.95 | 0.01 | 22.72 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 2.59 | 0.61 |

| PGF | 0.02 | 25.75 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 23.65 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 2.71 | 0.44 |

| FLT1 | −0.03 | 32.00 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 29.42 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 3.36 | 0.11 |

| KDR | 0.07 | 16.92 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 15.65 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 1.79 | 0.77 |

| FLT4 | 0.05 | 30.07 | 0.47 | 0.09 | 27.65 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 3.16 | 0.16 |

| NRP1 | 0.08 | 30.29 | 0.32 | −0.04 | 28.07 | 0.65 | −0.04 | 3.21 | 0.61 |

| NRP2 | 0.13 | 32.75 | 0.12 | −0.11 | 30.09 | 0.17 | −0.09 | 3.44 | 0.26 |

| Protein | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P |

| FLT4 | 0.17 | 0.001 | 0.04 | −0.25 | 9.93e-5 | 0.002 | −0.25 | 1.13e-5 | 0.003 |

| NRP1 | −0.01 | 4.74e-5 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 4.41e-5 | 0.88 | −0.007 | 5.03e-6 | 0.94 |

Boldface signifies P<0.05.

The reported beta coefficients are standardized.

Figure 2. FLT4 Whole Blood Protein Abundance Associations with AD CSF Biomarkers.

Whole blood protein abundance of FLT4 was associated with higher CSF levels of Aβ−42 (A, (β=41.34, p=0.042), lower CSF levels of tau (B, β=−57.34, p=0.002), and lower levels of phosphorylated tau (C, β=−6.34, p=0.003).

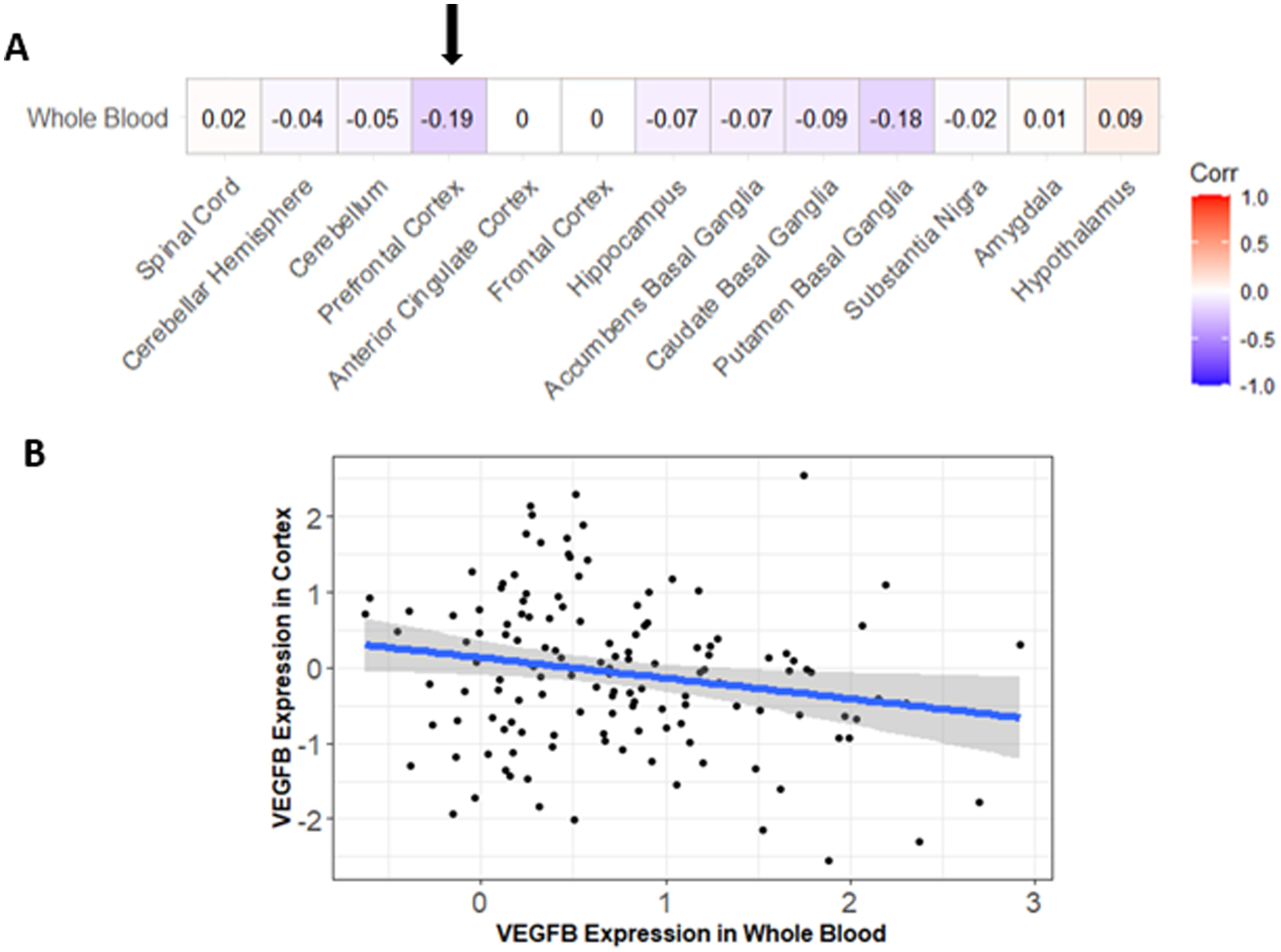

2.3. Posthoc Analysis in GTEx

Higher gene expression of VEGFB in whole blood was correlated with lower expression in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 3, r=−0.19, p=0.02). No other significant correlations between VEGFB gene expression in whole blood and brain tissues were observed. PGF tissue gene expression correlations did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 3. Correlation Between VEGFB Expression in Whole Blood and Brain Regions in GTEx.

Pearson correlations were calculated between VEGFB expression in various brain regions and whole blood within GTEx (A). The most significant correlation was between expression in the prefrontal cortex and whole blood, indicated by the arrow (A). Higher levels of VEGFB expression in whole blood were associated with lower levels of VEGFB expression in the prefrontal cortex (B). No other significant correlations were observed.

4. Discussion

In this study we examined the associations between VEGF gene expression and protein abundance in blood with cognition and AD biomarkers in a cohort of older adults enriched for MCI. The only finding that survived correction for multiple comparisons was the association between protein levels of FLT4 with CSF biomarkers of tau pathology, whereby higher blood levels of FLT4 were associated with lower biomarkers of tau pathology. In transcriptomic analyses, we observed nominal associations that did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. Higher whole blood expression of the VEGFB gene was associated with better memory scores, while higher PGF gene expression in whole blood was associated with worsening memory scores over time. Notably, the association between PGF and longitudinal memory performance was slightly attenuated when covarying for baseline memory performance. Together, these findings provide strong supportive evidence of FLT4 alterations in AD, while providing some exciting preliminary evidence that some of the brain changes in VEGFB and PGF may be detectable in the blood. Future work with a larger sample size will be needed to replicate the present results and clarify when along the disease cascade blood alterations in the VEGF family become detectable.

We previously observed an association between FLT4 mRNA levels in the brain with AD neuropathology, but it is notable that the effect observed here in blood was in the opposite direction. Unfortunately, we did not have a proteomics dataset with both blood and brain protein levels of FLT4 available for analysis, so it is hard to decipher whether the inverted direction is due to differences in blood compared to brain, differences in protein compared to mRNA, or are completely unrelated to one another. FLT4 is a particularly interesting candidate in blood given its known biological function. Flips in the direction of association are also observed in the brain depending on the brain region assessed (Weijts, 2013), leaving open the possibility that the difference in direction from blood to brain is biologically meaningful. For example, while higher levels of FLT4 are associated with worse outcomes when measured in the prefrontal cortex in ROS/MAP (Mahoney et al., 2019) and four other brain regions in AMP-AD (https://agora.adknowledgeportal.org/genes/(genes-router:gene-details/ENSG00000037280), the opposite direction of effect is observed within in the caudate nucleus in ROS/MAP (currently under review) and in the anterior cingulate in AMP-AD. Therefore, it will be critical to determine whether blood levels of FLT4 reflect any of the changes observed in the brain or whether they are independent of any brain alterations. Regardless, the present result provides supportive evidence of an association between FLT4 and AD neuropathology that extends to the blood compartment.

The present results also provide nominal supportive evidence for associations between both PGF and VEGFB blood transcript levels with cognition, however it is important to note that these associations did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. Interestingly, the whole blood PGF association with cognition was consistent in direction with our previous observation in brain, while the VEGFB association showed an opposite direction of effect (Mahoney et al., 2019). For that reason, we leveraged data from the GTEx project to assess whether brain and blood levels of VEGFB are anti-correlated in those without disease. Indeed, we observed higher gene expression of VEGFB in whole blood was correlated with lower gene expression in the prefrontal cortex, the same region in which we previously observed the association with cognition (Mahoney et al., 2019), suggesting higher blood levels may be indicative of lower brain levels of VEGFB. This is an observation not previously reported in the literature. Therefore, further studies are needed to replicate these results and provide more clarity on potential mechanistic effects. The associations we saw in memory did not extend to executive function, leaving open the possibility that these associations are domain specific. Replication will be critical to confirm these results given the possibility of type I error, and larger studies will be needed to determine domain specificity.

It is quite interesting that the correlation between blood and brain VEGFB appears to vary by region. The data from GTEx vary in sample size by brain region, so that is one potential contributor, particularly given that the number of participants with both brain and blood is low (n=6). There is also heterogeneity in VEGFB correlations across brain regions. Regardless of the mechanism, it is quite interesting that there is a correlation between blood VEFB and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex VEGFB expression, given that is the region that we had previously observed robust VEGFB effects.

It is also notable that in our previous work (Mahoney et al., 2019), VEGFB gene expression in the brain was strongly correlated with the expression of its primary receptor FLT1 in the brain, and that both genes showed robust associations with cognition and amyloid. In contrast, the blood results in the present manuscript are restricted to VEGFB with a smaller effect size compared to the brain, perhaps due to the weak correlation between brain and blood gene expression of VEGFB and the lack of a correlation between brain and blood for FLT1.

There are several possible explanations for the observed VEGFB association in blood, though we note that these are speculative given the preliminary level of evidence provided. First, VEGFB plays an active role in vascular repair in response to injury, including CNS injury (Linton, 2021), stroke (Greenberg, 2013; Ng et al., 2019), and neurodegeneration (Melincovici, 2018). Repair mechanisms are thought to include both angiogenic and immune cell recruitment and activation, so it may be that peripheral changes reflect a peripheral immune migration process towards a site of injury. However, it is also possible that blood levels reflect sequestration of VEGFB in the brain when more actively bound in response to injury. The present results do not provide a clear mechanism but do suggest that peripheral levels of VEGFB are relevant to cognition and should be further explored in larger studies in the future.

Given that the associations reported in this manuscript were observed in blood, it is quite likely that circulating and systemic factors, rather than brain-related changes, are key to both the gene/protein levels and cognitive/neuropathology associations. That said, the correlation between expression of these genes in the blood and the brain even in the absence of disease highlights the exciting possibility that common factors, or even direct interactions between peripheral and central factors, may be relevant to VEGF associations with cognition and warrant future investigation.

4.1. Conclusions

Our results highlight the potential of FLT4 as a potential blood biomarker in aging and AD that warrants future investigation. Preliminary evidence of alterations in VEGFB and PGF in the blood are also provided, though the transcript evidence for these two genes did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. The present study has multiple strengths, including a well characterized cohort, longitudinal follow-ups, comprehensive assessment of AD biomarkers, and fasting protocols for blood and CSF collection. Limitations include the lack of measurement of many VEGF family members at the protein level, the lack of diversity which limits generalizability to cohorts of non-European ancestry, and the fact that a few of the transcript associations do not survive correction for multiple comparisons. Limitations also include how preparation of plasma samples and materials used can influence the ability to compare results across various studies. Future work will further characterize the VEGF family at the protein level in the brain and assess other assays for measuring VEGF proteins in the blood.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Alector, Eisai, Denali, Roche Diagnostics, Wave, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Pinteon Therapeutics, Nervgen, AZTherapies, CogRx and Red Abbey Labs, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure and Biogen, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work). KB has served as a consultant, at advisory boards, or at data monitoring committees for Abcam, Axon, Biogen, JOMDD/Shimadzu. Julius Clinical, Lilly, MagQu, Novartis, Prothena, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthineers, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (all outside the work presented in this paper). TH is a member of the scientific advisory board for Vivid Genomics (also outside the work presented herein).

References

- Ali M (2022). VEGF Paradoxically Reduces Cerebral Blood Flow in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Neuroscience Insights, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RE, Robbins AB, Hu M, Cao X, Betensky RA, Clark T, Das S, & Hyman BT (2018). Tau induces blood vessel abnormalities and angiogenesis-related gene expression in P301L transgenic mice and human Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 10.1073/pnas.1710329115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almodovar CR, Lambrechts D, Mazzone M, & Carmeliet P (2009). Role and therapeutic potential of VEGF in the nervous system. Physiological Reviews, 89(2), 607–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia KO, Ornellas FLM, Martin PKM, Patti CL, Mello LE, Frussa-Filho R, Han SW, & Longo BM (2014). Therapeutic effects of the transplantation of VEGF overexpressing bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in the hippocampus of murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 6–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DA (2013). Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors (VEGFs) and Stroke. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 70(10), 1753–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L-H, Alexopoulos P, & Perneczky R (2013). Heart-type fatty acid binding protein and vascular endothelial growth factor: Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates for Alzheimer’s disease. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 263(7), 553–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman TJ, Bell SP, & Jefferson AL (2015). The Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Neurodegeneration and Cognitive Decline: Exploring Interactions With Biomarkers of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurology, 72(5), 520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Jia J, & Liu R (2013). Decreased serum levels of the angiogenic factors VEGF and TGF-β1 in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroscience Letters, 550, 60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AL, Gifford KA, Acosta LMY, Bell SP, Donahue MJ, Taylor Davis L, Gottlieb J, Gupta DK, Hohman TJ, & Lane EM (2016). The Vanderbilt Memory & Aging Project: Study Design and Baseline Cohort Overview. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Preprint, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Tong M, Hang S, Deochand C, & de la Monte S (2013). CSF and Brain Indices of Insulin Resistance, Oxidative Stress and Neuro-Inflammation in Early versus Late Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism, 3, 128. 10.4172/2161-0460.1000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton AE (2021). Pathologic sequelae of vascular cognitive impairment and dementia sheds light on potential targets for intervention. Cerebral Circulation-Cognition and Behavior, 2, 100030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, Phillips R, Lo E, Shad S, Hasz R, Walters G, Garcia F, Young N, Foster B, Moser M, Karasik E, Gillard B, Ramsey K, Sullivan S, Bridge J, Magazine H, Syron J, … Moore HF (2013). The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nature Genetics, 45(6), 580–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2653 http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v45/n6/abs/ng.2653.html#supplementary-information [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney ER, Dumitrescu L, Moore AM, Cambronero FE, De Jager PL, Koran MEI, Petyuk VA, Robinson RAS, Goyal S, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Jefferson AL, & Hohman TJ (2019). Brain expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene family in cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 10.1038/s41380-019-0458-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melincovici CS (2018). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) – key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Romanian Journal of Morphology & Embryology, 59(2), 455–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miners JS, Schulz I, & Love S (2018). Differing associations between Aβ accumulation, hypoperfusion, blood–brain barrier dysfunction and loss of PDGFRB pericyte marker in the precuneus and parietal white matter in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 38(1), 103–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AM, Mahoney E, Dumitrescu L, De Jager PL, Koran MEI, Petyuk VA, Robinson RA, Ruderfer DM, Cox NJ, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Jefferson AL, & Hohman TJ (2020). APOE epsilon4-specific associations of VEGF gene family expression with cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging, 87, 18–25. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TKS, Ho CSH, Tam WWS, Kua EH, & Ho RC-M (2019). Decreased Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Levels in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci, 20(2), 257. 10.3390/ijms20020257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver N (2022). Establishing Quality Control Procedures for Sample Preparation of High-Throughput Plasma Proteomics [Poster]. US HUPO, Charleston, South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Provias J, & Jeynes B (2014). Reduction in Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression in the Superior Temporal, Hippocampal, and Brainstem Regions in Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Neurovascular Research, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto M (2022). RNASE6 is a novel modifier of APOE-ε4 effects on cognition. Neurobiology of Aging, 118, 66–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva T (2023). Circulating levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A case-control study. Behavioural Brain Research, 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Mao X, Xie L, Greenberg DA, & Jin K (2013). Expression level of vascular endothelial growth factor in hippocampus is associated with cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 34(5), 1412–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Miners S, & Love S (2015). Post-mortem assessment of hypoperfusion of cerebral cortex in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Brain, 138(Pt 4), 1059–1069. 10.1093/brain/awv025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijts BGMW (2013). Atypical E2fs Control Lymphangiogenesis through Transcriptional Regulation of Ccbe1 and Flt4. PloS One, 8(9), e73693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]