Abstract

mTORC1, the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, is a key regulator of cellular physiology. The lipid metabolite phosphatidic acid (PA) binds to and activates mTORC1 in response to nutrients and growth factors. Here, we review structural findings and propose a model for PA activation of mTORC1. PA binds a highly conserved sequence on α4 helix of the FKBP12-rapamycin binding domain of mTOR. It is proposed that PA binding to two adjacent positively charged amino acids breaks and shortens the C-terminal region of α4-helix. This leads to profound consequences for substrate binding and catalytic activity of mTORC1.

Keywords: mTOR, FRB, phosphatidic acid, phospholipase D, Rheb, structure

Background

mTORC1 – mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 – is a conserved [1] serine/threonine catalytic complex containing mTOR, Raptor and mLST8, that integrates signals from nutrients and growth factors to regulate cell growth, proliferation, survival and metabolism [2]. Activation of mTORC1 is thought to be a two-step process whereby amino acids induce Rag-dependent translocation of mTORC1 [3] from the cytoplasm to the lysosome, followed by mTOR kinase activation by the lysosomal GTPase Rheb [3]. mTORC1 phosphorylates substrates that regulate ribosome biogenesis, protein translation initiation, lipid synthesis, nucleotide synthesis, and inhibition of autophagy [2,4], collectively promoting cellular anabolism that leads to biomass accumulation before progression into S phase and ultimately mitosis.

We have recently reported that amino acids induce phosphatidic acid (PA)-dependent transport of mTORC1 to the lysosome where it binds the Rag GTPases, that lock mTORC1 on the lysosome [5]. Moreover, we found that growth factor stimulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome also requires PA [5]. mTOR kinase activation by PA is induced by growth factor stimulation of the lysosomal small GTPase Rheb and activation of the PA-generating enzyme, phospholipase D (PLD) [6], which also translocates to the lysosome in response to amino acids [7]. Critically, we were able to induce mTORC1 translocation and substrate phosphorylation with PA in the absence of amino acids, growth factors, Rag GTPases and Rheb [5]. These findings suggest that PA binding to mTORC1 is sufficient for mTORC1 substrate binding and catalytic activity. Here, we review important structural findings that support a model whereby PA binding to mTORC1 displaces inhibitory substrates such as PRAS40, but allows positive substrate binding such as S6K1, and provides a Rheb memory signal to mTORC1 that would allow mTORC1 to leave the lysosome and encounter substrates in a maximally activated state.

mTORC1 structure

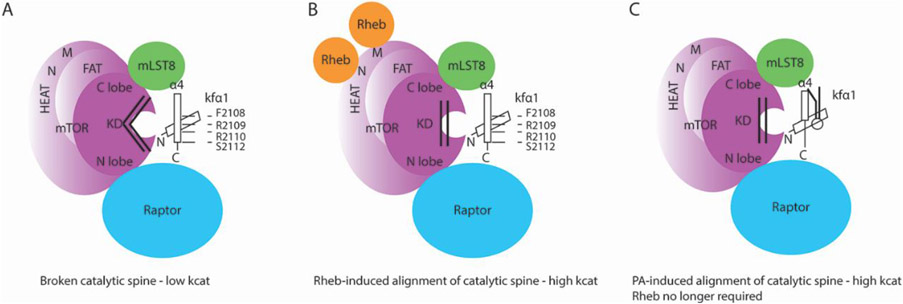

While much is known about the cues, upstream pathways and downstream targets that govern mTORC1 signaling, the precise mechanisms of complex assembly, target recruitment and kinase activity remained largely unresolved until studies employing cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) [8-10]. Such studies started shedding light on the mTORC1 structure at the amino acid residue level on a global scale (Figure 1). mTORC1 is an obligate dimer. In each monomer, the kinase domain forms a recessed catalytic cleft surrounded by Raptor and mLST8, and covered by the FK506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12)-rapamycin binding (FRB) domain (Figure 2A). The reported structures for mTORC1 have been reviewed in [11,12]. Substrate recruitment occurs via Raptor binding to TOR signaling (TOS) motifs on mTORC1 substrates, and via a secondary substrate binding site located in the FRB domain. The latter acts like a recruitment docking site that allows correct positioning and binding of substrate target loop in the catalytic cleft of the kinase domain of mTOR for phosphorylation. The FRB domain also binds to PA, a lipid metabolite required for mTORC1 assembly and activity [13-15], which has recently been shown to induce mTORC1 translocation to the lysosome in the absence of amino acids [5]. Recent data suggest that Rheb activates mTORC1 through distal binding that triggers a series of conformational changes that result in the correct alignment of ATP and Mg2+ charged residues with catalytic residues in the catalytic cleft [10,12]. Rheb thusly changes a broken catalytic spine into a narrow and aligned catalytic spine [10,12].

Figure 1.

Summary of structural studies used in this review. (A) Twenty-five year timeline of mTORC1 structural data achievement. The first crystal structure of an mTOR domain – the FRB domain, in a ternary complex with rapamycin and FKBP12 was achieved in 1996 at a resolution of 2.7 Å. Approximately 25 years later, the structure of whole mTORC1, as well as several mTORC1 subunits in complex with substrates and regulators have been solved at resolutions that range from 1.75 to 3.4 Å. (B) Study description: reference, species, methodology, and resolution for crystal structures. NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; CDS: circular dichroism spectroscopy; Cryo-EM: cryo-electron microscopy; SPR: surface plasmon resonance.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of mTORC1 with data provided from structural studies included in this review. (A) mTORC1 contains the subunits mTOR, raptor and mLST8. Raptor and mLST8 are positioned near the kinase domain of mTOR. The mTOR domains N and M HEAT are the farthest from the kinase domain. The FAT domain of mTOR is positioned between the HEAT and the kinase domain of mTOR. The FRB domain is positioned on top, and restricts access, to the catalytic cleft (hollow area) of the kinase domain of mTOR. Substrate phosphorylation by mTORC1 requires 1) substrate binding to raptor through the TOS motif, 2) substrate binding to the FRB recruitment docking site which positions the nearby substrate target loop correctly into the catalytic cleft, and 3) catalytic cleft phosphorylation of substrate target loop. (B) Detailed representation of the kinase domain of mTOR covered by the FRB domain. The catalytic cleft of the kinase domain (hollow area) is enclosed by the FRB α-helices α1 and α4. The crossing of α1-α4 generates a hydrophobic pocket that starts at residue F2108 of α4. α4 ends at residue P2112 [16]. The first two residues outside the pocket are positively charged and highly conserved – R2109 and R2110 [21]. Spatial organization of the side chains of the two adjacent positively charged amino acids R2109 and R2110 can interfere with α4 stability at the C terminal region that follows the hydrophobic pocket.

Structure of the FRB domain of mTORC1

The first crystal structure of an mTOR domain came from a study of the ternary complex made by FRB-rapamycin-FKBP12 [16]. Upon entering the cell rapamycin binds to FKBP12 and then binds to mTOR at the FRB domain forming a ternary, inhibitory complex [16]. This study revealed the structure of FRB for the first time. Since then, many other studies have observed the same secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure of the FRB domain bound to rapamycin-FKBP12 [8,9,17] (Figure 1). Structural studies of FRB alone show identical secondary and tertiary structures [14] (Figure 1). Importantly, studies reporting crystal structures (crystallography and cryo-EM) or solution structures (nuclear magnetic resonance - NMR, circular dichroism spectroscopy – CD spectroscopy, and surface plasmon resonance - SPR) of FRB are overall in agreement, although not completely identical [8-10,14,16-19] (Figure 1). The FRB domain contains a disordered, flexible N-terminal region (residues 2014 – 2018), followed by a well-defined structure of 4 helices (α1: W2023-G2040; α2: V2044 – R2060; α3: L2065 – L2090; α4: V2094 – S2112), and ends with a disordered C-terminal region (residues 2113 and 2114) [14,16,17]. Importantly, α1 and α4 form a deep hydrophobic cleft near their crossing point that is lined by six aromatic side chains [16] (Figure 2B). This cleft forms the hydrophobic pocket where rapamycin binds [16] (Figure 2B and 3A). Choi et al. [16], showed that residues F2039 (α1), W2101 (α4), Y2105 (α4) and F2108 (α4) are especially important for binding to rapamycin (Table 1). Residues S2035 (α1), L2031 (α1), T2098 (α4), D2102 (α4) and Y2038 (α1) also connect to rapamycin (Table 1). This study indicated that upon binding to FRB, rapamycin induced allosteric conformational changes that inhibited the kinase domain of mTOR (allosteric inhibitor). However, recent studies show that the FRB domain sits on top of, and restricts access to the kinase domain. Upon rapamycin-FKBP12 binding to FRB, substrate access to the catalytic site in the kinase domain is completely blocked by FKBP12 [8,9]. In addition, the FRB domain mediates substrate binding (discussed below) [8,10] and rapamycin inhibits mTORC1 activity by preventing substrate binding near the catalytic cleft, which in turn prevents target loop binding to the catalytic cleft [8,10]. These studies suggest that rapamycin may not act through allostery, but by affecting substrate binding to the catalytic site. However, it is reasonable to accept that both mechanisms – allostery and substrate binding inhibition co-exist since data from live cells indicate that upon rapamycin binding mTORC1 falls apart [20]. Of significance, PA binds to the α4 helix of the FRB domain adjacent to the binding site for rapamycin in a manner that is competitive with rapamycin [13,15]. Without PA, similar to rapamycin treatment, mTOR and raptor dissociate making mTORC1 functionally compromised [15,20]. Below we provide a detailed discussion of the FRB-PA interaction and consequences regarding substrate binding and catalytic activity.

Figure 3.

Interactions mediated by the recruitment docking site of FRB positioned above the kinase domain of mTORC1. (A) Interactions with rapamycin, S6K1 and PRAS40. Rapamycin binds to the hydrophobic pocket at the crossing of α1 and α4. Rapamycin inhibits substrate recruitment and induces allosteric changes in the kinase domain. A short α-helix of S6K1 makes few contacts with α4, mainly insertion of L396 at the beginning of the hydrophobic pocket. A long α-helix of PRAS40 makes many contacts with α4, including C-terminal areas immediately outside the pocket. (B) Interactions between PA and FRB. The negatively charged PA headgroup makes ionic interactions with two highly conserved positively charged residues, R2109 and R2110, positioned on α4 immediately outside of the hydrophobic pocket. The hydrophobic acyl chains of PA are inserted into the hydrophobic pocket. The interaction of doubly deprotonated PA (−2) with two adjacent positively charged side chains induces side chain spatial rearrangement that destabilizes the C terminal region of α4. PA breaks α4 immediately after the hydrophobic pocket generating a shorter α4 with consequences for substrate binding and tertiary structure conformational changes that affect the kinase domain. (C) PA binding to FRB allows S6K1, but not PRAS40 or rapamycin binding. PA can accommodate S6K1 insertion of L396 into the beginning of the hydrophobic pocket. However, PA disrupts the C-terminal α4 region that makes several interactions with PRAS40. In addition, occupancy of the hydrophobic pocket by the acyl chains of PA prevents many interactions of the pocket with PRAS40 and rapamycin.

Table 1.

FRB residue interactions that regulate mTORC1 catalytic activity. The crossing of α1 and α4 of FRB generates a hydrophobic pocket that is part of the FRB recruitment docking site. There is extensive overlap of FRB residues that interact with rapamycin, S6K1, PRAS40 and PA. Some FRB residues interact with more than one residue of the binding protein or molecule. Residues are listed according to importance of interactions. Specific correspondence between interacting residues is fully described in the text. The FRB recruitment docking site is critical for substrate binding and phosphorylation. Drugs that inhibit mTORC1 activity, such as rapamycin, bind to the hydrophobic pocket and prevent substrate recruitment (Km) and induce conformational changes that affect catalytic turn-over (kcat). PA binds to the FRB recruitment docking site allowing binding of positive substrates such as S6K1, but not negative substrates, such as PRAS40, or rapamycin. The high sequence conservation of the FRB domain is explained by the positive role of PA on selective substrate recruitment and conformational changes that lead to catalytic clef alignment that no longer requires Rheb binding. N/A: not applicable.

| Interacting molecule |

Interacting residues on molecule |

Interacting residues on FRB: α4 |

Interacting residues on FRB: α1 |

Effect on mTOR kinase |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin | N/A | W2101 | F2039 | Km | [16] |

| Y2105 | S2035 | kcat (?) | |||

| F2108 | L2031 | ||||

| T2098 | Y2038 | ||||

| D2102 | |||||

| S6K1 | L396 | F2108 | F2039 | Km | [10] |

| V395 | W2101 | ||||

| V399 | Y2105 | ||||

| PRAS40 | M222 | Y2105 | Y2038 | Km | [10] |

| L215 | F2108 | F2039 | |||

| I218 | S2112 | ||||

| A219 | |||||

| L225 | |||||

| V226 | |||||

| PA | N/A | R2109 | L2031 | Km | [14] |

| W2101 | F2039 | kcat (?) | [18] | ||

| Y2105 | [19]. | ||||

| S2102 | |||||

| Y2105 | |||||

| H2106 |

The FRB domain contains a recruitment docking site for mTORC1 substrates

Raptor provides a substrate binding site, which binds to the substrate TOS motif. An additional site for substrate binding was later discovered in the FRB domain. [8,10]. The FRB site positions the substrate target loop correctly into the catalytic cleft. The precise interactions between the FRB domain and the mTORC1 targets PRAS40 and S6K1, have been characterized by the Pavletich group [10] (Figure 3A). It is important to note that surprisingly, the Pavletich group found that α4 of FRB extends to P2116 [10] and not S2112 [14,16,17]. Structural data showed that 7 amino acid residues (S394 – K400) of S6K1 adopt an amphipathic α-helix that aligns with the rapamycin binding site of FRB [10]. S394-K400 is very close to the phosphorylation site T389 on S6K1 (5 residues distance). The side chain of L396 extends from the helix and inserts into the FRB pocket made by helices α1 and α4 [10]. This pocket is lined by F2039 (α1), W2101 (α4), Y2105 (α4), and F2108 (α4) – residues that were shown to be critical for binding to rapamycin [16] (Table 1). Additional FRB contacts are made by V395 and V399 that flank L396, and which interact with FRB α1 residues (not clear for V395, and F2039 for V399) [10] (Table 1). It is important to note that a 7 amino acid α-helix in S6K1 is a small helix with less than two turns. It is important to note that rapamycin appears to make more and deeper contacts than S6K1 [10]. S6K1 is positioned at the surface of the cleft with mostly L396 inserted in the hydrophobic pocket made by α1 and α4 of FRB (Figure 3A). Importantly, mutation of L396 to A396 induced a strong reduction of mTOR kinase activity in vitro, while a transient transfection of the mutant lead to reduced S6K1 phosphorylation (37% of wild type) [10]. A broader look at other mTORC1 substrates [10], confirmed the notion that substrates bind to the FRB recruitment docking site in order to access the catalytic cleft.

The structural study that characterized the FRB interaction with S6K1 also showed that PRAS40, a negative regulator of mTORC1, interacts with both the FRB domain on mTOR and the TOS motif on Raptor [10]. PRAS40 forms an amphipathic α-helix between residues 212 and 232 (20 amino acids – about 5 turns). The PRAS40 helix is longer than the S6K1 helix and makes more contact with α4 of the FRB [10] (Figure 3A). In PRAS40, the M222 side chain inserts into the same rapamycin pocket that L396 of S6K1 does, and interacts with Y2105 of FRB (Table 1). However, PRAS40 has 5 additional contacts mediated by hydrophobic side chains of L215 (Y2038, α1 FRB), I218 (Y2038, α1 FRB), A219 (F2039, α1 FRB), L225 (F2108, α4 FRB) and V226 (S2112, α4 FRB) (Table 1). In agreement with PRAS40 binding to the FRB recruitment docking site, deletion of 33 residues of PRAS40 (residues 206-256) reduced mTORC1 phosphorylation of PRAS40 by a factor of four [10]. The interaction of PRAS40 with α4 of FRB is severely compromised upon PA binding to FRB [15]. This indicates that PA can modify substrate affinity toward the FRB recruitment docking site. Consistent with this idea, suppressing PA production increased association between mTOR and PRAS40, while PA addition to cells completely displaced PRAS40 from mTORC1 [15]. Thus, PA binding to the FRB domain apparently disrupts the forces that stabilize the interaction between PRAS40 and FRB (Figure 3B and 3C). As described above, there is an interaction between F2108 of helix α4 and PRAS40. The PA binding site is R2109 and R2110 [21] – two positively charged amino acids immediately adjacent to F2108 that binds PRAS40 (Figure 3B and 3C). A plausible conclusion is that PA binding disrupts and shortens the end of α4 (Box 1) and reduces the affinity for PRAS40. PA binding still allows S6K1 binding because S6K1 binds above the lost region of α4 (Figure 3B and 3C). A recent report shows the crystal structure of mTORC1 bound to the negative substrate DEPTOR [22]. However, in this report, the region of DEPTOR that potentially binds to FRB and the region that is phosphorylated by mTORC1 remained unresolved [22]. Because PA has been shown to displace DEPTOR from mTORC1 [23] in response to mitogens, it is possible that PA prevents binding of DEPTOR to the FRB recruitment docking site, similar to PRAS40 (both DEPTOR and PRAS40 are negative regulators of mTORC1).

Box 1. Two adjacent charged amino acids can break α-helices.

The α-helix was first identified by Linus Pauling [29,33]. The α-helix is right-handed, just like the DNA double-helix. There are 3.6 amino acid residues per turn of the helix, and for every turn, the helix rises 5.4 Å along the axis [29]. In the α-helix , the carbonyl oxygen of each residue forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone NH group four residues ahead [29]. The backbone hydrogen-bonding tendencies are therefore met, except for the four residues at each end of the helix [29]. This supports the idea that it is easier to destabilize an α-helix at the ends. α4 of the FRB domain ends at S2112 [14,16-18], suggesting that an interaction with PA with R2109 and R2110 (within the last four amino acid residues) could disrupt the helix. Most α-helices are 12 amino acid residues long [29]. The α-helix is solid, where the atoms of the polypeptide backbone are in van der Waals contact [29]. In the α-helix, the side chains extend outward from the helix [29]. This is a very important aspect of α-helices. In fact, the two major factors that stabilize the α-helix are intrachain hydrogen bonding and minimization of steric interference between side chains. This brings us to the question: how can two adjacent positively charged amino acids allow α-helix formation? Identical charges repel each other. The side chains may be able to point outward from the backbone in opposite directions, allowing the charges to be as far away from each other as possible. However, when PA binds to R2109 and R2110, both positively charged side chains will adopt a new orientation. They will point outward from the polypeptide backbone but right next to each other and sustained by the interaction with the negatively charged headgroup of PA. PA binding thus induces strong side chain spatial orientation changes, that in turn break the H-bonds that stabilize α-helix formation and in doing so – making the α4 helix in the FRB domain shorter at the C terminal end. We propose that the lost region of α4 has critical consequences in terms of mTORC1 substrate binding to the FRB recruitment docking site. It also has an impact in overall FRB conformation that ripples to the kinase domain of mTORC1 and induces catalytic spine alignment and increased mTORC1 catalytic activity (Figure 4).

PA binds the FRB domain and determines substrate binding selectivity

Extensive data shows that the FRB domain of mTOR binds to PA to promote mTORC1 assembly and stability [14,15,18,19,21]. We recently reported that the interaction between mTORC1 and PA is required for mTORC1 translocation to the lysosome and full activation of mTORC1 by Rheb [5]. Three studies have provided solution structures for the interaction between FRB and PA [14,18,19]. These studies employed water-soluble PA with short fatty-acyl chain (C6). It is important to note that PA is a lipid and likely difficult to introduce into in vitro protein complex reconstitution. This is likely the main reason why PA has been missed by crystallography and cryo-EM studies.

Veverka et al. [14] showed that R2109 (α4) interacts with the negatively charged phosphomonoester (See Glossary) headgroup of PA [24] (Table 1); the acyl chain at carbon 1 of the glycerol backbone (away from the monophosphate headgroup of PA) makes van der Waals interactions with the side chains of L2031 (α1), F2039 (α1), W2101 (α4), and Y2105 (α4) (note that this acyl chain occupies part of the rapamycin binding site) (Table 1); the acyl chain at carbon 2 of the glycerol backbone binds to the side chains of S2102 (α4), Y2105 (α4) and H2106 (α4) [14] (Table 1). The FRB residues are identical or immediately adjacent to residues that interact with rapamycin [16]. This suggests that PA binding to FRB prevents interactions involved in rapamycin binding. This is confirmed by live cultured cell studies that show that rapamycin and PA bind competitively to the FRB domain [13,15,25]. These studies also show that PA has the exact opposite effect of rapamycin and promotes mTORC1 complex assembly and stability [15], while rapamycin causes the dissociation of mTOR and Raptor and loss of mTORC1 activity [20]. Moreover, while rapamycin inhibits mTORC1 phosphorylation of substrates [26], PA increases substrate phosphorylation [5-7,13,15,27]. Importantly, R2109 and R2110 of the FRB domain show high sequence conservation [21], with some eukaryotes displaying different combinations of R and K at these two positions [21] (both with positively charged side chains). The high sequence conservation of FRB represents a positive regulatory function of this domain, exerted through PA. PA binding is so important for mTORC1 activity, that bacteria developed a compound that targets the exact same area – rapamycin. Rapamycin would allow bacteria to thrive over unicellular eukaryotes while living in the same environment and competing for the same resources.

It was recently reported that a compound known as ICSN3250 inhibited mTORC1 by displacing PA from the FRB domain [19]. The effect of ICSN3250 was similar to the effect of rapamycin, which competes with PA for binding to the FRB domain of mTORC1 [13,15,25,28]. This study provided additional solution structure insight for the interaction between FRB and PA that is blocked by ICSN3250. In this study the negatively charged phosphate headgroup of PA was found to interact with R2109 at the surface of the hydrophobic pocket made by α1 and α4 of FRB, while the hydrophobic tails of PA were found deeply buried and making extensive contacts with the hydrophobic pocket. These data confirm previous findings [14]. It is of potential significance that in the FRB-PA structural interaction model provided by Nguyen et al., α4 is shorter [19] than in FRB observed in other structural studies where PA was missing [10,16]. It is of interest that other structural studies of PA do not present ribbon models for the interaction between FRB-PA so we cannot assess where α4 ends in these two studies [14,18]. A shorter α4 of FRB in response to PA binding is consistent with the negatively charged phosphate headgroup binding to adjacent positively charged amino acids at 2109 and 2110 (Box 1) [29] (Figure 3B). It is possible that this is fundamental for mTORC1 target selectivity in the presence of PA. A short α4 would significantly reduce the extended interactions with PRAS40, but would still allow for the fewer interactions between FRB and S6K1, which does not require the end of α4 [10] (Figure 3C). The interaction between the FRB domain and S6K1 is mostly dependent on the introduction of L396 on S6K1 into the hydrophobic pocket on the FRB domain. This could be accommodated by long hydrophobic tails of PA. Binding of S6K1 L396 to the hydrophobic pocket in the presence of PA is unlike rapamycin and PRAS40, which make several interactions with the hydrophobic pocket and would thus be prevented from binding in the presence of PA (Figure 3C). Binding of PA to the FRB domain may well represent a mechanism of target selectivity that displaces negative targets such as PRAS40, but allows positive substrate binding, such as S6K1, and phosphorylation. In this sense PA could play the role of a gatekeeper for access to the recruitment binding site of the FRB domain without which, substrates cannot be phosphorylated in the catalytic cleft. PA would contribute to the catalytic efficiency of mTORC1 toward S6K1 by allowing S6K1 binding to the recruitment docking site and thus reducing the Km for mTORC1 toward S6K1.

PA can bind to FRB as part of membranes

Another structural study examined the interaction between FRB and membranes [18], especially PA-rich membranes. This study proposed that the FRB domain behaves like a reversible peripheral membrane domain. The interactions identified by this study were identical to interactions previously described [14]. Importantly, Camargo et al. [18] found that membrane binding to FRB induces strong conformational changes that largely maintain the α-helical secondary structure but not the tertiary structure (different from free FRB), where helices are now dispersed in the lipid environment. This could have an impact at the interface between FRB and kinase domain. In agreement with the competitive nature between PA and rapamycin, binding of rapamycin-FKBP12 to FRB prevents the domain from interacting with PA-rich membranes at lower lipid concentrations (lower than 10mM), but can be overcome by high lipid concentrations (higher than 10mM) [18]. The first study that described the interaction between PA and FRB [13] showed that the isolated FRB domain bound strongly to liposomes containing PA between 10 and 50%. Importantly, Camargo et al show that the FRB domain can bind to lipids below the critical micelle concentration, meaning that the FRB domain can bind to a lipid outside of a membrane structure (Box 2). This favors the idea that mTORC1 interacts with PA in membranes, translocates to the lysosome, interacts with Rag GTPases and Rheb, and later interacts with Rheb-induced PA produced by PLD at the lysosomal membrane (Box 2). Single PA binding to the FRB domain could represent a memory signal from previous Rheb activation of mTORC1 and promote catalytic activity (kcat) and selective substrate recruitment (Km) with a very high impact on mTORC1 catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km).

Box 2. PA is unique for generating two negative charges.

PA binding proteins lack a consensus lipid binding amino acid sequence. Instead, PA binding is mediated through ionic interactions between positively charged amino acids - especially R and K, in the binding protein, and the negatively charged phosphomonoester headgroup of PA [24]. Most PA binding domains also have interspersed hydrophobic amino acids that interact with the hydrophobic tails of PA and allow insertion into the membrane bilayer [24]. The FRB recruitment docking site of mTORC1 – where PA binds, has two adjacent positively charged residues R2109 and K2110 [21], preceded by a hydrophobic pocket that accommodates the fatty acid tails of PA.

PA is a unique phospholipid for two reasons. Firstly, PA contains a phosphomonoester headgroup instead of a phosphodiester. This means that PA can have two negative charges instead of one. Secondly, PA is kept at very low cellular concentrations [24]. This means that generation of PA upon specific cues triggers specific cellular events. PA is generated by PLD in response to amino acids and growth factors. PLD hydrolyzes the most abundant membrane phospholipid, phosphatidylcholine, to generate PA. PA binding proteins are initially attracted to at least one negative charge in the headgroup of PA in a membrane bilayer. The ionic interaction with one negative charge in PA promotes the dissociation of the second proton, which has a pKa slightly higher than physiologic pH - 7.9 [24]. This generates a second negative charge that locks the interaction between PA and the binding protein. Because the pKa of the phosphomonoester headgroup of PA is within physiologic range (6.9 – 7.9 [24]), PA has been proposed as an intracellular pH sensor. Of significance, the lysosomal v-ATPase, which participates in mTORC1 signaling [3], pumps protons from outside to inside of the lysosome. This pH increase outside the lysosome could lead to complete deprotonation of PA. We propose that PA with at least one negative charge binds to mTORC1 as part of membrane vesicles and brings mTORC1 to the lysosome [5]. At the lysosome, Rheb-induced PLD generates PA with two negative charges. The stronger interaction with mTORC1 would allow PA to detach from the membrane and travel with mTORC1 as a memory signal of Rheb activation. PA-bound activated mTORC1 could then phosphorylate substrates elsewhere in the cell, in agreement with studies showing that mTORC1 translocation and substrate phosphorylation have different kinetics [31], and that substrate phosphorylation can happen in the absence of Rheb [5].

Role of Rheb in mTORC1 activation – activation of lysosomal PLD to generate PA

It was recently reported that Rheb binds cooperatively to N and M-Heat repeats of mTOR distally positioned relative to the kinase domain [10]. However, the two interactions induce conformational changes that ripple through mTOR and end up inducing catalytic cleft alignment in a way that ATP and Mg2+ charged residues are optimally positioned relative to catalytic residues [10,12] (Figure 4A and 4B). While the structural mechanism of Rheb activation of mTORC1 is very appealing, it does not explain how mTORC1 retains activity outside the lysosome and away from Rheb. Rheb has a lipid modification that embeds the protein onto the lysosome membrane. This means that Rheb does not leave the lysosome [30]. It was reported that the kinetics for activation of mTOR by amino acids was not correlated with the kinetics for lysosomal translocation of mTORC1 [31]. Lysosomal translocation occurred substantially faster than substrate phosphorylation – suggesting that mTORC1 may be activated at the lysosome, but likely travels to other sites where substrates are located. We recently reported that PA drives mTORC1 to the lysosome and promotes mTORC1 activity in the absence of amino acids, Rag GTPases, growth factors and Rheb [5]. It is well known that upon amino acid stimulation, mTORC1 travels to the lysosome, but so does PLD1 [7]. Once on the lysosome, PLD1 is in close contact with its activator, Rheb [6]. Unlike mTOR [32], Rheb binds to PLD in a GTP-dependent manner to promote PLD activity and increased PA production at the lysosome [6]. mTOR can bind Rheb regardless of its GDP/GTP content, even though only GTP-Rheb can activate mTORC1 activity [6,32]. This and the fact that we were able to induce mTORC1 activity with PA in absence of Rheb suggests that the key step in mTORC1 activation downstream of Rheb is PA production by PLD1 at the lysosome [5]. Rheb would induce catalytic cleft alignment of the kinase domain of mTOR and increased production of PA by PLD1. Once a single PA bound to the FRB domain of mTOR, FRB conformational changes would be induced, leading to catalytic cleft alignment, and making Rheb no longer required. mTORC1 could then leave the lysosome and encounter its targets in a fully activated state. PA would therefore constitute a Rheb memory signal leading to catalytic spine alignment and activation of mTORC1 outside of the lysosome (Box 2).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of Rheb activation of mTOR kinase. (A) The catalytic spine of the kinase domain of mTOR is not well aligned, or broken, in the absence of Rheb [10]. (B) Upon Rheb cooperative interaction with distal N and M HEAT domains, a ripple of conformational changes in mTOR ends up aligning critical residues of the catalytic cleft optimally for phosphorylation [10]. This leads to high catalytic turn-over (kcat) [10]. (C) PA binding to the FRB domain induces conformational changes that similarly to Rheb, align the catalytic spine of the mTOR kinase. PA production at the lysosome is induced by growth-factor activated Rheb. Upon lysosomal PA generation and binding to mTOR at the FRB, Rheb is no longer required for maximal activity of mTORC1 [5].

Concluding remarks

We propose a model for PA regulation of mTORC1 (Figure 5, Key Figure) where: 1) PA-rich membranes bind to the FRB domain of mTORC1 and bring mTORC1 to the lysosome; 2) detachment of PA from PA-rich membranes or from increased PA production at the lysosome upon growth factor activation of Rheb and PLD1, would allow a single PA molecule to bind FRB; 3) PA binding to the FRB domain would break and shorten the C-terminus of the α4 helix, thus preventing rapamycin binding, promoting displacement of PRAS40, but allowing S6K1 binding; 4) PA binding to the FRB domain would keep catalytic cleft alignment and provide a memory signal of Rheb activation of mTORC1 – but Rheb would no longer be required, allowing mTOR to travel to substrate location in a fully activated state; 5) PA would have an overall effect that lowers the Km for effector substrates such as S6K1, while keeping the catalytic spine aligned, thus keeping kcat high. Therefore, PA would increase the catalytic efficiency of mTORC1 (kcat/Km) – this would explain why PA can induce mTORC1 activity in the absence of amino acids, Rag GTPases, growth factors and Rheb [5]. Our model explains important questions in the field that remain unanswered (see Outstanding Questions).

Figure 5.

Proposed model of PA activation of mTORC1. PA binding to the FRB domain breaks and shortens the C-terminus of the α4 helix, with important consequences for substrate binding and catalytic activity of mTORC1. PA binding reduces the Km for S6K1 binding but increases the Km for PRAS40 and rapamycin. PA binding also induces tertiary structure conformational changes that lead to alignment of the catalytic spine of the kinase domain of mTOR, resulting in increased catalytic turn-over (kcat). The two effects combined lead high mTOR catalytic efficiency (kcat /Km) that no longer requires Rheb. Upon PA binding, a fully activated mTORC1 can leave the lysosome and phosphorylate target substrates elsewhere in the cell. Our model is based on structural evidence available in literature, reviewed here.

Outstanding Questions.

Rapamycin and PA bind to the same FRB region, which highly conserved. It is very unlikely that the sequence was evolutionarily kept with the purpose of binding rapamycin – an inhibitor. Was the sequence highly conserved because it binds PA, and PA binding is critical for mTORC1 assembly, translocation, substrate binding and catalytic activity?

The majority of mTORC1 effector substrates do not localize at the lysosome. Does mTORC1 leave the lysosome to phosphorylate its substrates?

Does mTORC1 require vesicle trafficking to reach its substrates outside of the lysosome?

If mTORC1 is activated through Rheb binding at the surface of the lysosome, how does mTORC1 keep its catalytic activity outside of the lysosome, where substrates exist? Does Rheb leave the lysosome with mTORC1? Rheb has not been found in the cytoplasm.

Even though GTP-Rheb activates mTORC1, Rheb interacts with mTOR in a GTP-independent manner. Does this mean that Rheb activity (GTP-Rheb) is required to activate PLD and generate PA for maximal mTORC1 activity even outside of the lysosome?

How does PA induce mTORC1 activity in the absence of Rheb?

What is the crystal structure of mTORC1 bound to PA?

Highlights.

mTORC1 plays a critical role in cellular physiology. Amino acids lead to mTORC1 lysosomal translocation where it is activated by growth factors via Rheb.

PLD and its lipid metabolite PA are required for both amino acid and growth factor input to mTORC1. PA induces mTORC1 lysosomal translocation and activation in the absence of amino acids, Rag GTPases, growth factors and Rheb.

We review recent structural findings and propose that PA binds to a highly conserved sequence on the α4 helix of the FRB domain of mTOR. Critically, by binding to two adjacent positively charged amino acids, PA disrupts the helix with consequences for substrate binding and catalytic activity.

α4-helix disruption by PA allows S6K binding to FRB, but not PRAS40 or rapamycin. α4-helix disruption by PA induces FRB conformational changes that allow mTORC1 catalytic activity in the absence of Rheb.

Abbreviations:

- FKBP12

FK506 binding protein 12

- FRB

FKBP12-rapamycin binding

- mTOR

mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

mTOR Complex 1

- PA

phosphatidic acid)

- S6K1

S6 Kinase 1

Glossary

- kcat

Catalytic turn-over number or catalytic rate constant. It is the maximal number of molecules of substrate converted to product per active site per time unit. The higher kcat is, the higher the catalytic efficiency is in terms of product formation over time.

- kcat/Km

The ratio between catalytic turn-over number and Michaelis-Menten constant, also known as catalytic efficiency. The Higher kcat and the lower Km, the higher catalytic efficiency is.

- Km

Michaelis-Menten constant. It is a ratio between reaction rate constants that can be experimentally determined as the concentration of substrate at which one half of the reaction maximal velocity is reached. It reflects substrate binding or substrate affinity, even though the relationship is complex. The lower the Km, the more efficient a reaction is in terms of substrate binding.

- pH

the negative logarithm of the concentration of protons or H+. Physiologic pH is 7.4. The lower the pH, the more acidic the solution, or the environment is. Conversely, the higher the pH, the more basic a solution, or environment, is.

- Phosphomonoester

a phosphate group that mediates one phosphoester bond. It can generate up to two negative charges.

- Phosphodiester

a phosphate group that mediates two phosphoester bonds. It can only generate one negative charge.

- pKa

the negative logarithm of the acid dissociation constant Ka. It is the pH at which there is 50% deprotonation or release of H+.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gonzalez A and Hall MN (2017) Nutrient sensing and TOR signaling in yeast and mammals. EMBO J 36, 397–408. 10.15252/embj.201696010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dibble CC and Manning BD (2013) Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nat Cell Biol 15, 555–564. 10.1038/ncb2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Efeyan A et al. (2012) Amino acids and mTORC1: from lysosomes to disease. Trends Mol Med 18, 524–533. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laplante M and Sabatini DM (2012) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frias MA et al. (2019) Phosphatidic acid drives mTORC1 lysosomal translocation in the absence of amino acids. J Biol Chem. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Y et al. (2008) Phospholipase D1 is an effector of Rheb in the mTOR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 8286–8291. 10.1073/pnas.0712268105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon MS et al. (2011) Class III PI-3-kinase activates phospholipase D in an amino acid-sensing mTORC1 pathway. J Cell Biol 195, 435–447. 10.1083/jcb.201107033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H et al. (2013) mTOR kinase structure, mechanism and regulation. Nature 497, 217–223. 10.1038/nature12122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aylett CH et al. (2016) Architecture of human mTOR complex 1. Science 351, 48–52. 10.1126/science.aaa3870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H et al. (2017) Mechanisms of mTORC1 activation by RHEB and inhibition by PRAS40. Nature 552, 368–373. 10.1038/nature25023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan HX and Guan KL (2016) Structural insights of mTOR complex 1. Cell Res 26, 267–268. 10.1038/cr.2016.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao LH and Avruch J (2019) Cryo-EM insight into the structure of MTOR complex 1 and its interactions with Rheb and substrates. F1000Res 8. 10.12688/f1000research.16109.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang Y et al. (2001) Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science 294, 1942–1945. 10.1126/science.1066015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veverka V et al. (2008) Structural characterization of the interaction of mTOR with phosphatidic acid and a novel class of inhibitor: compelling evidence for a central role of the FRB domain in small molecule-mediated regulation of mTOR. Oncogene 27, 585–595. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toschi A et al. (2009) Regulation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 complex assembly by phosphatidic acid: competition with rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol 29, 1411–1420. MCB.00782-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi J et al. (1996) Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science 273, 239–242. 10.1126/science.273.5272.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang J et al. (1999) Refined structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin-FRB ternary complex at 2.2 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 55, 736–744. 10.1107/s0907444998014747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez Camargo DC et al. (2012) The FKBP-rapamycin binding domain of human TOR undergoes strong conformational changes in the presence of membrane mimetics with and without the regulator phosphatidic acid. Biochemistry 51, 4909–4921. 10.1021/bi3002133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TL et al. (2018) mTOR Inhibition via Displacement of Phosphatidic Acid Induces Enhanced Cytotoxicity Specifically in Cancer Cells. Cancer Res 78, 5384–5397. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DH et al. (2002) mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell 110, 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster DA (2013) Phosphatidic acid and lipid-sensing by mTOR. Trends Endocrinol Metab 24, 272–278. 10.1016/j.tem.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walchli M et al. (2021) Regulation of human mTOR complexes by DEPTOR. Elife 10. 10.7554/eLife.70871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon MS et al. (2015) Rapid mitogenic regulation of the mTORC1 inhibitor, DEPToR, by phosphatidic acid. Mol Cell 58, 549–556. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin JJ and Loewen CJ (2011) Putting the pH into phosphatidic acid signaling. BMC Biol 9, 85. 10.1186/1741-7007-9-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y et al. (2003) Phospholipase D confers rapamycin resistance in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene 22, 3937–3942. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fingar DC and Blenis J (2004) Target of rapamycin (TOR): an integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 23, 3151–3171. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu L et al. (2011) Phospholipase D mediates nutrient input to mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). J Biol Chem 286, 25477–25486. M111.249631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhopadhyay S et al. (2016) The Enigma of Rapamycin Dosage. Mol Cancer Ther. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pratt CW, Cornely K (2011) Essential Biochemistry Second edn), Wiley, John Wiley & Sons, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sancak Y et al. (2008) The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science 320, 1496–1501. 10.1126/science.1157535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manifava M et al. (2016) Dynamics of mTORC1 activation in response to amino acids. Elife 5. 10.7554/eLife.19960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Long X et al. (2005) Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase. Curr Biol 15, 702–713. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pauling L et al. (1951) The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 37, 205–211. 10.1073/pnas.37.4.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]