Abstract

Purpose

Post-operative outcome after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the treatment of end-stage osteoarthritis correlates strongly with pre-operative impairment-driven patient treatment goals. However, a clinical tool for measuring patient treatment goals in correlation to impairments is still missing, which impedes patient-oriented indication in TKA.

Methods

Patients scheduled for TKA were recruited in four German hospitals. All patients were handed the INDICATE Knee Score pre-operatively. The score contains 31 treatment goals with respective impairments, subdivided into seven categories. They were asked to rank all treatment goals and impairments on a 3-point scale. Treatment goals and impairments were then checked for frequency of occurrence. Correlation of goal and impairment was tested. Analysis for associations of treatment goals and different cohort characteristics (age, sex, BMI) was conducted.

Results

1.298 patients were included in the study. Seven treatment goals were categorised as “main goal” from more than 90% of all patients (“knee pain”, “range of motion”, “walking distance”, “overall physical function”, “climbing stairs”, “quality of life”, “implant survival”). Comparing age groups, there were significant associations towards higher expectations regarding working, physical and sports related treatment goals in younger patients (< 65y) (“ability to work” (P ≤ .001), “sports activities” (P ≤ .001), “sex life” (P ≤ .001), “dependence on help of others” (P = .015), “preventing secondary impairment” (P = .03), “dependence on walking aids” (P = .005)). Higher BMI resulted in increasing relevance of “weight reduction” (P ≤ .001), “climbing stairs” (P = .039) “global health status” (P = .015) and “long standing” (P = .007) as a “main goal”. Analysis for differences in treatment goals regarding sex showed women choosing more treatment goals as “main goals” than men.

Conclusion

Seven treatment goals which were expected by > 90% in our collective can be classified as general treatment goals for TKA. Demographic factors (age, sex, BMI) were significantly associated with patients’ expectations for TKA. We conclude physicians should clearly assess their patients’ demands prior to TKA to maximise post-operative outcome.

Level of evidence

Prognostic Level III.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Patient expectation, Impairment, Treatment goal, Satisfaction, INDICATE Knee Score

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a common and frequent orthopaedic procedure for the treatment of end-stage knee osteoarthritis (OA), and its cost-effectiveness and improvement of quality of life are well proven [14]. A large number of studies have shown that patients after TKA are satisfied in most cases, but a relevant amount remains unsatisfied [4, 29]. Among other factors (i.e. surgical or patient related factors), fulfillment of patients’ expectations has been linked with post-operative satisfaction [20, 28]. It is known, that patients tend to have overly optimistic pre-operative expectations in TKA [23], and that patients dissatisfied after TKA were most likely those who had unfulfilled expectations [4, 8].

Consequently, it seems highly necessary to discover patient expectations prior to surgery for adequate shared decision-making (SDM) in indication for TKA, and hereby maximising post-operative satisfaction. Many instruments to measure expectations in orthopaedic procedures are physician derived [30]. To gain more objective, patient-derived data on patients’ expectations, the most widespread instruments for measuring pre-operative expectations are the patient-derived Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) Hip and Knee Replacement Expectations Surveys, published by Mancuso et al. in 1997 and 2001, respectively [5, 22]. In these questionnaires, Mancuso et al. did not observe the association between patients’ actual impairments and their expectations. However, studies have shown that severe symptoms are a significant predictor for patient expectations in total joint arthroplasty [31]. Despite the high relevance of patients’ impairments for their expectations, a clinical instrument for measuring expectations in correlation to impairments is still missing [30].

Furthermore, expectations may vary between geographical and cultural regions. Therefore, a questionnaire based on previously published known expectations and patient-defined treatment goals in relation to their respective impairments has been developed [12].

The objective of this study was to assess patients’ pre-operative impairments, treatment goals, and their correlation in a cross-sectoral large cohort using this new questionnaire. It was hypothesised that demographic factors (age, sex, BMI) significantly influence pre-operative treatment goals in TKA.

Materials and methods

Prior to this study, the INDICATE Knee Score questionnaire containing a set of consensus-based treatment goals was developed via a 3-stage Delphi study [17, 18]. Based on the previously published known expectations for TKA, the patients were able to add further treatment goals during the Delphi process. The Delphi survey technique is a common method to achieve a group consensus across disciplines in which individual opinions are combined into group consensus [13].

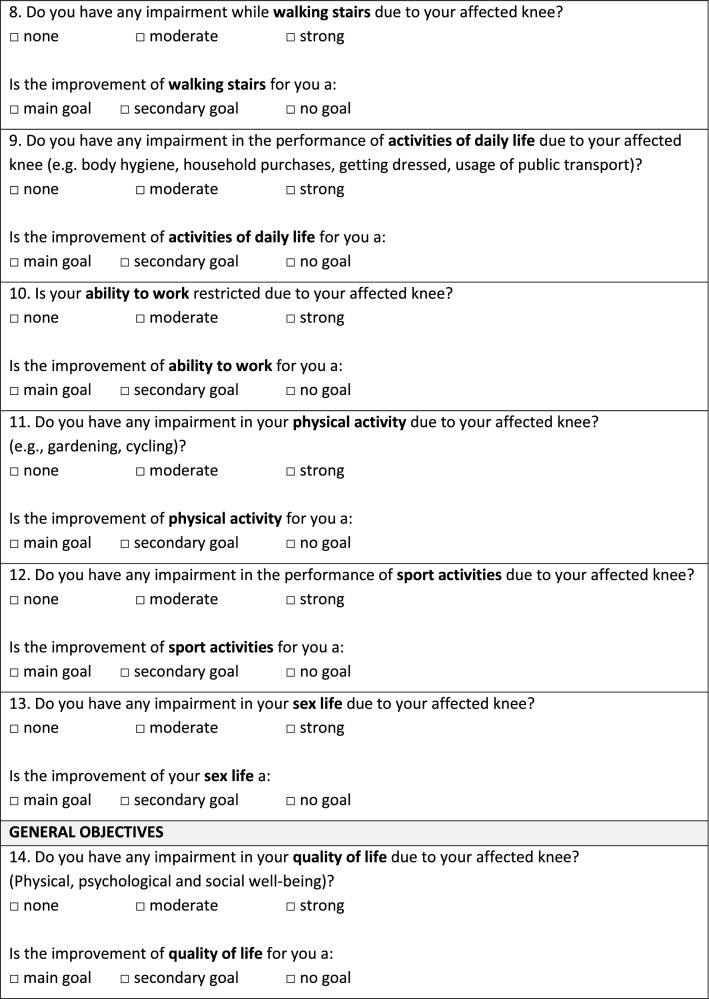

As shown in Fig. 1, the questionnaire contains 31 patient treatment goals assorted into seven categories (symptoms, physical function, activities of daily life, quality of life, physical activity, coping strategies, and various issues). Patients were asked to rank all proposed treatment goals on a 3-point Likert scale (“main goal”, “secondary goal”, “no goal”). “Main goals” were defined as an outcome that must be reached through TKA, otherwise the procedure would not be considered successful by the patient. “Secondary goals” were desirable goals but were not necessary for the success of the surgery. “No goals” were defined as unimportant. Patients could select as many goals as “main goals”, “secondary goals” or “no goal” as they desired. Additionally, the current subjective perception of impairment was asked for each treatment goal via a 3-point scale (“no impairment”, “moderate impairment”, “severe impairment”).

Fig. 1.

Questionnaire

After approval from all ethics committees in the participating states, all patients older than 18 years that met standardised criteria for surgery [27] and were scheduled for TKA due to advanced OA of the knee were included. Exclusion criteria were German language inability, noncompliance of signing a written consent, life expectancy less than 1 year as judged by the treating physician, and any health factors that would preclude elective surgery.

Participants eligible for the study were recruited in four different types of German hospitals: two tertiary referral university hospitals, one orthopaedic specialised arthroplasty hospital and one regional hospital. A large sample of patients were included in this study via the PROMISE Trial [3]. All eligible patients were asked to participate and the questionnaire was handed out after informed consent,

Data collection was conducted in an outpatient clinic at time of surgery indication 1–8 weeks prior to TKA. Included patients were handed the survey during their outpatient clinic visit. Qualified study nurses on site explained the questionnaire and the participants were asked to complete the survey on their own. The questionnaire was then checked for completion. In addition to the expected treatment goals, baseline data were collected to describe the study population including age, sex, side of surgery, diagnosis, BMI, and socioeconomic data (education, living with partner, working situation). Data were assembled from all study sites and stored pseudonymised in an electronic database.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics, impairments and treatment goals were expressed as mean or percentage values as appropriate. Univariate comparisons of treatment goals and age, sex, and BMI were performed using Chi-Square and Fisher-Exact Tests. Spearman rank correlation was used for correlation of treatment goals and the respective impairments. Ranges for correlation strength were considered as “very strong” (0.80–1), “strong” (0.60–0.79), “medium” (0.40–0.59), “weak” (0.20–0.39) and “very weak” (0.00–0.19) [15]. Post hoc power calculation showed that there was a power above 80% to detect weak correlations given the used sample and an alpha-level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R (R version 3.5.1, Core Team (2017)) [34].

Results

1.298 patients with complete data sets were included in the study. Mean age was 67.4 years (SD 9.74), 55% were women. 92.1% of all patients received TKA because of primary osteoarthritis. Side of surgery was nearly evenly distributed (46.3% left vs. 49.2% right) with 59 patients (4.5%) receiving simultaneous bilateral TKA. All baseline data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) (mean [SD]) | 67.35 (9.74) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 45.0% (584) |

| Female | 55.0% (714) |

| Side of surgery | |

| Left | 46.3% (601) |

| Right | 49.2% (638) |

| Both | 4.5% (59) |

| Reason for surgery | |

| Primary osteoarthritis | 92.1% (1196) |

| Posttraumatic osteoarthritis | 5.0% (65) |

| Other | 2.6% (34) |

| Missing | 0.2% (3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean[SD]) | 30.6 (7.4) |

| Education | |

| < Ten years | 41.1% (533) |

| Ten years | 34.1% (442) |

| > Ten years | 22.3% (289) |

| Other | 0.4% (5) |

| Missing | 2.2% (29) |

| Living with partner | |

| Yes | 75.0% (974) |

| No | 23.6% (306) |

| Missing | 1.5% (18) |

| Working situation | |

| Unemployed / Not working | 3.9% (51) |

| Working | 30.0% (389) |

| Retired | 63.3% (821) |

| Other | 0.9% (12) |

| Missing | 1.9% (25) |

BMI body mass index

Impairments

The most frequently chosen “severe impairments” were “walking distance”, “physical endurance”, “knee pain”, “overall physical function”, “climbing stairs”, “long standing”, “sports”, and “physical activity”. The impairments “noise from the joint”, “sex life” and “managing personal hygiene” were least frequently chosen as “severe impairment”. One percent of patients (N = 13) chose all impairments as “severe impairment”. Distribution of impairments is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Impairments of patients

Expectations

Evaluation of treatment goals showed seven treatment goals being categorised as “main goal” from more than 90% of all patients (“knee pain”, “range of motion”, “walking distance”, “overall physical function”, “climbing stairs”, “quality of life”, “implant survival”). Thirty-five (2.7%) patients chose all treatment goals as “main goal”. Figure 3 illustrates the ranked proportions of main goal, secondary goal, and no goal in the study population.

Fig. 3.

Treatment goals of patients

Statistically significant differences could be shown between age (< 55, 55–65, > 65 years), sex (male, female), and BMI (< 25, 25–30, > 30 kg/m2) and treatment goals (Table 2). When stratified by age, “ability to work” and “sex life” were more often chosen as “main goal” by younger patients (< 55 years). “Weight reduction” showed higher percentages as “main goal” in young patients < 55 years than in patients > 65 years (68.4% vs 48.3%), whereas “sports activities” was more often chosen as “main goal” by patients between 55 and 65 years (70.7% vs 75.9% vs 68.8%). There were also significant differences when stratifying treatment goals by sex, with women choosing more treatment goals as “main goals” than men. The categories “walking distance”, “ability to work”, “sex life”, “physical activities” and “long standing” were more often chosen as “main goal” by men, although without any statistical significance. With increasing BMI (< 25, 25–30, > 30 kg/m2), “weight reduction” was more often chosen as “main goal”.

Table 2.

Percentage of “main goals” chosen in each group and overall statistical significant differences (as p-values*) between “treatment goals” in different subgroups (statistical significant results in bold type)

| Category | Age | BMI | Sex | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 55 y | 55–65y | > 65y | p-value | < 25 | 25–35 | > 35 | p-value | Male | Female | p-value | |

| Reduction of knee pain | 94.7% (126) | 94.5% (380) | 93.7% (714) | .454 | 89.3% (184) | 95.4% (456) | 94.8% (579) | .007 | 94.0% (549) | 94.1% (672) | .041 |

| Range of motion (ROM) | 93.2% (124) | 91.5% (368) | 93.8% (715) | .700 | 89.3% (184) | 92.7% (443) | 94.6% (578) | .047 | 91.3% (533) | 94.5% (675) | .002 |

| Leg strength | 82.0% (109) | 82.8% (333) | 82.8% (631) | .370 | 80.1% (165) | 82.6% (395) | 83.6% (511) | .696 | 79.6% (465) | 85.1% (608) | .002 |

| Knee stability | 85.7% (114) | 86.6% (348) | 88.1% (671) | .417 | 88.3% (182) | 86.6% (414) | 87.4% (534) | .758 | 84.4% (493) | 89.6% (640) | .002 |

| Malalignment | 54.9% (73) | 62.4% (251) | 62.3% (475) | .03 | 62.6% (129) | 64.0% (306) | 59.2% (362) | .619 | 57.7% (337) | 64.7% (462) | .001 |

| Physical function | 93.2% (124) | 92.3% (371) | 89.8% (684) | .290 | 89.3% (184) | 90.2% (431) | 92.0% (562) | .140 | 89.7% (524) | 91.9% (656) | .06 |

| Walking distance | 87.2% (116) | 92.0% (370) | 92.0% (701) | .120 | 88.8% (183) | 91.8% (439) | 92.1% (563) | .068 | 92.0% (537) | 91.2% (651) | .108 |

| Climbing stairs | 91.7% (122) | 89.6% (360) | 92.5% (705) | .306 | 88.3% (182) | 91.6% (438) | 92.6% (566) | .039 | 90.8% (530) | 92.2% (658) | .044 |

| Activities of daily life | 85.0% (113) | 79.9% (321) | 82.9% (632) | .766 | 77.7% (160) | 80.1% (383) | 85.4% (522) | .035 | 77.6% (453) | 86.0% (614) | < .001 |

| Ability to work | 85.0% (113) | 76.1% (306) | 63.8% (486) | < .001 | 64.6% (133) | 68.4% (327) | 72.5% (443) | .164 | 70.7% (413) | 69.0% (493) | .067 |

| Physical activities | 88.0% (117) | 89.1% (358) | 88.6% (675) | .839 | 84.5% (174) | 89.7% (429) | 89.0% (544) | .227 | 88.7% (518) | 88.5% (632) | .784 |

| Sport activities | 70.7% (94) | 75.9% (305) | 68.8% (524) | < .001 | 71.4% (147) | 72.8% (348) | 69.7% (426) | .275 | 70.7% (413) | 71.6% (511) | .454 |

| Sex life | 30.1% (40) | 25.6% (103) | 13.6% (104) | < .001 | 18.0% (37) | 17.6% (84) | 20.3% (124) | .342 | 21.4% (125) | 17.1% (122) | .054 |

| Quality of life | 93.2% (124) | 95.3% (383) | 94.4% (720) | .274 | 91.7% (189) | 95.2% (455) | 95.1% (581) | .328 | 94.3% (551) | 94.8% (677) | .113 |

| Global health status | 76.7% (102) | 74.4% (299) | 72.2% (550) | .307 | 67.5% (139) | 70.5% (337) | 77.3% (472) | .015 | 72.1% (421) | 74.2% (530) | .319 |

| Participating in social life | 72.9% (97) | 72.6% (292) | 72.4% (552) | .672 | 67.5% (139) | 70.3% (336) | 75.8% (463) | .038 | 67.6% (395) | 76.5% (546) | < .001 |

| Less dependence on help of others | 56.4% (75) | 56.2% (226) | 63.3% (482) | .015 | 54.4% (112) | 56.5% (270) | 65.1% (398) | .011 | 54.8% (320) | 64.8% (463) | < .001 |

| Implant survival | 88.7% (118) | 94.8% (381) | 91.3% (696) | .003 | 88.8% (183) | 92.5% (442) | 93.0% (568) | .161 | 92.0% (537) | 92.3% (659) | .57 |

| Short hospitalisation | 59.4% (79) | 65.7% (264) | 66.0% (503) | .450 | 62.1% (128) | 65.9% (315) | 65.8% (402) | .478 | 64.4% (376) | 66.0% (471) | .6 |

| Preventing secondary impairments | 82.0% (109) | 83.6% (336) | 76.5% (583) | .03 | 77.7% (160) | 77.4% (370) | 81.0% (495) | .620 | 77.1% (450) | 81.0% (578) | .206 |

| Noise from the joint | 35.3% (47) | 42.0% (169) | 37.8% (288) | .035 | 35.4% (73) | 41.6% (199) | 37.8% (231) | .105 | 38.0% (222) | 39.5% (282) | .403 |

| Reduction of Swelling | 63.2% (84) | 63.2% (254) | 56.8% (433) | .003 | 54.4% (112) | 57.9% (277) | 62.4% (381) | .044 | 54.1% (316) | 63.9% (456) | < .001 |

| Managing household | 70.7% (94) | 68.2% (274) | 73.5% (560) | .072 | 64.6% (133) | 70.1% (335) | 75.0% (458) | .016 | 62.7% (366) | 78.7% (562) | < .001 |

| Transport related mobility | 91.7% (122) | 86.6% (348) | 87.4% (666) | .533 | 86.9% (179) | 84.7% (405) | 89.9% (549) | .036 | 84.4% (493) | 90.1% (643) | < .001 |

| Sleeping | 62.4% (83) | 60.7% (244) | 56.7% (432) | .246 | 51.0% (105) | 58.25 (278) | 61.2% (374) | .100 | 52.9% (309) | 63.2% (451) | < .001 |

| Long standing | 85.0% (113) | 82.3% (331) | 83.7% (638) | .918 | 77.2% (159) | 84.5% (404) | 84.6% (517) | .007 | 83.7% (489) | 83.2% (594) | .556 |

| Managing personal hygiene | 33.1% (44) | 35.3% (142) | 42.7% (325) | .028 | 33.0% (68) | 40.4% (193) | 40.6% (248) | .318 | 38.0% (222) | 40.5% (289) | .315 |

| Less dependence on walking aids | 43.6% (58) | 52.7% (212) | 57.3% (437) | .005 | 54.9% (113) | 51.7% (247) | 56.5% (345) | .389 | 53.1% (310) | 55.6% (397) | .488 |

| Physical endurance | 85.7% (114) | 84.8% (341) | 88.3% (673) | .093 | 82.5% (170) | 88.1% (421) | 87.6% (535) | .104 | 85.5% (505) | 87.4% (624) | .242 |

| Less use of drugs | 59.4% (79) | 51.5% (207) | 49.2% (375) | .347 | 47.6% (98) | 50.0% (239) | 52.5% (321) | .707 | 47.3% (276) | 53.9% (385) | .007 |

| Weight reduction | 68.4% (91) | 63.7% (256) | 48.3% (368) | < .001 | 17.5% (36) | 47.5% (227) | 73.8% (451) | < .001 | 50.7% (296) | 58.7% (419) | .005 |

*All p-values generated via Chi-Square and Fisher-Exact Test

Correlations

Positive correlation between impairment and the respective treatment goal could be shown for all categories (Table 3). Only one “very strong” correlation occurred in the category “sex life” (0.80), whereas no category showed a “very weak” (0.00–0.19) correlation.

Table 3.

Spearman's correlation rank test: treatment goals and impairments

| Category | Spearman’s Rho* |

|---|---|

| Sex life | 0.801 |

| Swelling | 0.749 |

| Personal hygiene | 0.749 |

| Sleeping | 0.744 |

| Noises | 0.731 |

| Drugs and its side effects | 0.691 |

| Leg alignment | 0.650 |

| Dependence on walking aids | 0.644 |

| Dependence on others | 0.638 |

| Ability to work | 0.622 |

| Global health status | 0.599 |

| Participation on social life | 0.593 |

| Managing household | 0.523 |

| Strength | 0.519 |

| Stability | 0.503 |

| Activities of daily life | 0.500 |

| Physical function | 0.461 |

| Transport-related mobility | 0.456 |

| Sport activities | 0.444 |

| Long standing | 0.436 |

| Walking distance | 0.382 |

| Joint mobility | 0.356 |

| Climbing stairs | 0.353 |

| Physical activity | 0.346 |

| Physical endurance | 0.335 |

| Quality of life | 0.306 |

| Knee pain | 0.246 |

*00–.19 “very weak”; .20–.39 “weak”; .40–.59 “moderate”

60–.79 “strong”; .80–1.0 “very strong”; Sorted order by strength of correlation

Discussion

The most important findings of this study were the seven treatment goals chosen as “main goal” from over 90% of all patients. Those can, therefore, be considered as generalised treatment goals for TKA. Patients’ expectations for TKA showed significant differences related to demographic factors (age, sex, BMI). Correlation between impairments and the respective treatment goals differed considerably. Overall, expectations were generally high.

This study describes the first implementation of a new, systematically developed, impairment-driven questionnaire (INDICATE Knee Score) [18], containing 31 items to cover a wide range of expectations in patients undergoing TKA. In contrast to the pre-existing patient expectations questionnaires of Mancuso et al. [5], a 3-point rather than a 5-point Likert scale was used, which has a good translation into clinical context and has been shown to be far easier to use, especially by patients with intellectual disability or non-readers [6, 9, 17]. The possibility to put patients’ expectations into context with their existing impairments could achieve better understanding of patients’ frames-of-reference concerning their pre-operative degree of activity. Different frames-of-reference have a significant influence on validity of current expectation surveys, as stated by Hepinstall et al. in 2011 [12]. A strength of this study is the large, heterogeneous sample of patients, based on the recruitment of participants in four different hospitals representing all levels of care. The cohort matches the reported distributions for age, sex, and BMI in TKA in Germany and other countries [1, 2, 10].

Assessing the distribution of patient expectations in our study, Hawker et al. showed similar results in a prospective study in a Canadian cohort [11]. Nevertheless, one has to take into account the previously described influence of ethnicity on expectations in patients undergoing TKA [16, 19]. Well-known treatment goals (e.g. “pain reduction”, “improvement of range of motion”, or “physical ability”) could be confirmed in our cohort. A potentially less known goal with high importance in our study was “long implant survival”. Because it can be presumed that surgeons generally expect a long implant survival, it might not always be addressed in the pre-operative discussion, even though it tends to be from great importance for patients undergoing TKA. This could lead to unfulfilled patient expectations in the post-operative care, if the estimated implant survival cannot be achieved. Unfulfilled expectations have been demonstrated to be a main reason for dissatisfaction after TKA [4], which is even more important under the aspect of overly optimistic pre-operative patient expectations in TKA, as shown by Mannion et al. [23]. The seven most chosen treatment goals discovered in this study should be considered as universal treatment goals and should hence be queried in addition to the patients’ individual treatment goals before surgery. Physicians should mandatorily assess and discuss the probability of their patients achieving these universal treatment goals during SDM and additionally should inquire for further, more individual patient treatment goals to detect special needs. Because of its precise 31 Items, the INDICATE Knee Score seems to be superior for these matters than the currently available expectations questionnaires. Surgeons could then exert a modifying influence on their patients’ expectations during the pre-surgical phase to guide them to more realistic treatment goals and hereby ensure post-operative realisation of expectations to improve overall satisfaction. The questionnaire further could help to close the previously demonstrated gap between patients’ overly optimistic, and surgeons’ realistic expectations [23, 24], which might support dissatisfaction after TKA.

Significant differences were demonstrated in expectations expressed as treatment goals regarding different demographic factors (age, sex, BMI). Previous literature is contradictory regarding the influence of age and sex on expectations [19, 21], with newer studies describing female and older patients having lower expectations on the outcome of TKA [12, 31]. This could not be confirmed in our study, with women having generally higher expectations on TKA and choosing more goals as “main goals” than men. As expected and in line with previous studies [32], this study showed a trend towards higher expectations regarding working, physical and sports related treatment goals in younger patients (< 65y) and men. In contrast, women chose treatment goals regarding everyday work (e.g. “managing household”, “activities of daily life”) significantly more often. This could be based on the conservative idea of womanhood predominating in the older population that was mostly included in our study. While overall data is scarce, Razmjou et al. [25] showed analogous trends in sex-specific expectations, meaning men having higher levels of expectations of returning to leisure-, recreational-, or work-related activities than women, although using a self-constructed, non-joint-specific questionnaire. Since existing questionnaires do not inquire expectations in these categories in detail, an implementation of the INDICATE Knee Score questionnaire in a different cultural context or an overall younger cohort would be interesting.

BMI had a significant influence on prioritisation of the treatment goal “weight reduction”, suggesting that obese patients expect TKA as a mean for weight reduction, probably through regaining the ability to exercise after surgery. Recent studies described both, weight loss and weight gain after TKA, with substantial effect on post-operative outcome [7, 26, 33]. It is, therefore, of particular importance to guide obese patients to realistic expectations in the pre-operative SDM process.

Younger, obese, and female patients in our cohort tend to rate the reduction of swelling more often as “main goal”, which might be for cosmetic reasons. The significant influence of female sex on the treatment goal “Malalignment” in our cohort might support this assumption. However, to the author’s knowledge no studies exist, describing women having higher cosmetic expectations on surgical outcomes. Surprisingly, “Less dependence on help of others” was more often chosen as main goal from older (> 65-year) patients, while one would usually anticipate that younger patients want to regain autonomy through TKA, as they are expected to care for themselves in a typical community. On the other hand, younger patients might have a larger scale of compensatory mechanisms in dealing with dependence (e.g. better social surroundings, better preparations), and therefore are less cowed of dependence on help of others.

Consistent with a previous study by Lange et al. [18], correlations between treatment goals and related impairments were low on a variety of variables in our cohort. Overall, an increase in correlation from more general to specific variables was observed. Thus, variables like “Knee pain”, “Quality of life”, “Joint mobility”, “Climbing stairs” and “Walking distance” showed low to modest correlation with their respective impairment, suggesting these over-arching treatment goals apply to every patient undergoing TKA and are independent of the impairment prior to surgery. Supporting this presumption is the high correlation in specific variables such as “Sleeping”, “Noise from the joint”, “Swelling” or “Sex life”. Patients with impairments in these categories seem to suffer from a high and specific psychological strain, seeking relief through TKA. These impairments are not typically induced exclusively by knee OA, and hence the probability of improving these impairments through TKA should be discussed during pre-operative SDM.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Only patients already enrolled in a TKA surgery process were included, thereby only the expectations of patients with end-stage osteoarthritis are reflected. However, this is typical for patients undergoing TKA and we, therefore, believe this cohort to be representative. The time of elicitation of the questionnaire differed between the participating hospitals, ranging from 1 to 8 weeks before surgery. A potential weakness of the questionnaire could be the mixture of general and specific treatment goals. However, we think this variety reflects the diversity and individuality of patients’ treatment goals for TKA and is helpful for physicians to better understand their patients’ motivation for surgery. In this study, the questionnaire was used paper based; a digital version should be generated for future application. Only patients from Germany were included; therefore, expectations might be different in other countries and cultures.

Conclusion

Seven treatment goals which were expected by > 90% of patients in our collective can be classified as general treatment goals for TKA. Influence of demographic factors (age, sex, BMI) on pre-operative expectations underline the need for knowing individual patient expectations, allowing physicians to guide their patients to realistic expectations and consequently improve satisfaction after TKA.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- TKA

Total knee arthroplasty

- BMI

Body mass index

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- SDM

Shared decision-making

- HSS

Hospital for special surgery

- SD

Standard deviation

Author contributions

FW participated in the design of the study, performed surgery, carried out data collection and abstraction, and drafted the manuscript. LE participated in the design of the study, performed surgery, carried out data abstraction and helped to draft the manuscript. MB performed statistical analysis. PD and JL conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination, performed surgery, acquired the funding, and helped to draft the manuscript. PD, UB and JK coordinated the data collection in the different centres, carried out data abstraction, and helped to draft the manuscript. TL and JL invented the questionnaire, participated in the study design, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the grant from the German Federal Joint Committee (01NVF16015).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Speakers bureau/paid presentations for a company or supplier: Aesculap, Mathys, Pfizer. Research support from a company or supplier as a Principal Investigator: Aesculap, Link, Mathys, Smith&Nephew, Stryker, ZimmerBiomet. Other financial or material support from a company or supplier: 2020: BMBF AutoPräz 30.000€; 2021: iDIERS: 28.031€. Medical/Orthopaedic publications editorial/governing board: BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology and Arthroscopy.

Ethical approval

Submission No.: 837.533.17 (11367), Ethics Committee at the State Chambers of Physicians of Rhineland-Palatinate. Submission No.: B-F-2018-042, Ethics Committee at the State Chambers of Physicians of Baden-Wuerttemberg. Submission No.: MC 84/2018, Ethics Committee at the State Chambers of Physicians of Hesse. Submission No.: EK 135042014 Ethics committee at the TU Dresden, Saxony.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.AOANJRR (2020) Annual 2020. Aust Orthop Assoc Natl Jt Replace Regist 2020 Annu Rep 219–289. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/. Accessed 05 Apr 2021

- 2.Ben-Shlomo Y, Blom A, Boulton C, Brittain R, Clark E, Craig R, et al (2020) National Joint Registry - 17th Annual Report 2020. Natl Jt Regist 138. https://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/default.aspx. Accessed 05 Apr 2021 [PubMed]

- 3.Betz U, Langanki L, Heid F, Spielberger J, Schollenberger L, Kronfeld K, et al. The PROMISE study protocol: a multicenter prospective study of process optimization with interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral care for German patients receiving hip and knee endoprostheses. Acta Orthop. 2021;92:156–162. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1853927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KDJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: Who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Wickiewicz TL, Jones EC, Robbins L, Warren RF, et al. Patients’ expectations of knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg - Ser A. 2001;83:1005–1012. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chachamovich E, Fleck MP, Power M. Literacy affected ability to adequately discriminate among categories in multipoint Likert Scales. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JY, Xu S, Pang HN, Tay DKJ, Chia SL, Lo NN, et al. Change in body mass index after total knee arthroplasty and its influence on functional outcome. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:718–722. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conner-Spady BL, Bohm E, Loucks L, Dunbar MJ, Marshall DA, Noseworthy TW. Patient expectations and satisfaction 6 and 12 months following total hip and knee replacement. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:705–719. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang J, Fleck MP, Green A, Mcvilly K, Hao Y, Tan W, et al. The response scale for the intellectual disability module of the WHOQOL: 5-point or 3-point? J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011;55:537–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimberg A, Jansson V, Lützner J, Melsheimer O, Morlock M, Steinbrück A (2020) Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD) Jahresbericht 2020. Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. https://www.eprd.de/de. Accessed 05 Apr 2021

- 11.Hawker GA, Conner-Spady BL, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Jones CA, Ravi B, Noseworthy T, et al. Patients’ preoperative expectations of total knee arthroplasty and satisfaction with outcomes at one year: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:223–231. doi: 10.1002/art.41510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hepinstall MS, Rutledge JR, Bornstein LJ, Mazumdar M, Westrich GH. Factors that impact expectations before total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones J, Hunter D. Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamaruzaman H, Kinghorn P, Oppong R. Cost-effectiveness of surgical interventions for the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1540-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krehbiel TC. Correlation coefficient rule of thumb. Decis Sci J Innov Educ. 2004;2:97–100. doi: 10.1111/j.0011-7315.2004.00025.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudibal MT, Kallemose T, Troelsen A, Husted H, Gromov K. Does ethnicity and education influence preoperative disability and expectations in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty? World J Orthop. 2018;9:220–228. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i10.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange T, Kopkow C, Lützner J, Günther KP, Gravius S, Scharf HP, et al. Comparison of different rating scales for the use in Delphi studies: Different scales lead to different consensus and show different test-retest reliability. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-0912-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange T, Schmitt J, Kopkow C, Rataj E, Günther KP, Lützner J. What do patients expect from total knee arthroplasty? a delphi consensus study on patient treatment goals. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2093–2099.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lingard EA, Sledge CB, Learmonth ID. Patient expectations regarding total knee arthroplasty: Differences among the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. J Bone Joint Surg - Ser A. 2006;88:1201–1207. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lützner C, Postler A, Beyer F, Kirschner S, Lützner J. Fulfillment of expectations influence patient satisfaction 5 years after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:2061–2070. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, Daltroy LH, Fortin PR, Fossel AH, et al. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol Canada. 2002;29:1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancuso CA, Salvati EA, Johanson NA, Peterson MGE, Charlson ME. Patients’ expectations and satisfaction with total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:387–396. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannion AF, Kämpfen S, Munzinger U, Kramers-de Quervain I (2009) The role of patient expectations in predicting outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Res Ther 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Noble PC, Fuller-Lafreniere S, Meftah M, Dwyer MK. Challenges in outcome measurement: Discrepancies between patient and provider definitions of success. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3437–3445. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3198-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razmjou H, Finkelstein JA, Yee A, Holtby R, Vidmar M, Ford M. Relationship between preoperative patient characteristics and expectations in candidates for total knee arthroplasty. Physiother Canada. 2009;61:38–45. doi: 10.3138/physio.61.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razzaki T, Mak WK, Bin Abd Razak HR, Tan HCA. Patterns of weight change and their effects on clinical outcomes following total knee arthroplasty in an asian population. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitt J, Lange T, Günther K-P, Kopkow C, Rataj E, Apfelbacher C, et al. Indication criteria for total knee arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis - a multi-perspective consensus study. Z Orthop Unfall. 2017;155:539–548. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-115120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott CEH, Bugler KE, Clement ND, MacDonald D, Howie CR, Biant LC. Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg Ser. 2012;94B:974–981. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B7.28219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott CEH, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: A prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg - Ser B. 2010;92:1253–1258. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swarup I, Henn CM, Gulotta LV, Henn RF. Patient expectations and satisfaction in orthopaedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolk JJ, Janssen RPA, Haanstra TM, Van Der Steen MMC, Bierma Zeinstra SMA, Reijman M. Outcome expectations of total knee arthroplasty patients: the influence of demographic factors, pain, personality traits, physical and psychological status. J Knee Surg. 2020;33:1034–1040. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1692632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witjes S, van Geenen RCI, Koenraadt KLM, van der Hart CP, Blankevoort L, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, et al. Expectations of younger patients concerning activities after knee arthroplasty: are we asking the right questions? Qual Life Res. 2017;26:403–417. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1380-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zan P, Yao JJ, Liu K, Yang D, Li W, Li G. Weight changes after total knee arthroplasty in Chinese patients: A matched cohort study regarding predictors and outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:20–26. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1184-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Core Team (2018) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/