Abstract

Contouring during adaptive radiotherapy (ART) can be a time-consuming process. This study describes the generation of patient specific contouring regions of interest (CRoI) for evaluating the high dose fall-off in stereotactic abdominal ART. An empirical equation was derived to determine the radius of a cylindrical patient specific CRoIs. These CRoIs were applied to 60 patients and their adaptive fractions (301 unique treatment plans). Out of the 301 unique treatment plans, 284 (94%) treatment plans contained the high dose fall-off within the CRoI. There was an expected predicted average timesaving of 2.9-min-per case. Patient specific CRoIs improves the efficiency of ART.

Keywords: Adaptive radiotherapy, SBRT, Gastrointestinal SBRT, MRgRT, CBCTgRT

1. Introduction

Abdominal stereotactic adaptive radiotherapy (ART) is associated with improved dosimetric and clinical outcomes [1], [2]. However, ART can be both a time and resource consuming process, including the need to recontour the daily anatomy [3], [4], [5]. To limit contouring time during ART while also ensuring that all relevant organs-at-risk (OARs) dose objectives are evaluated, a confined-expansion contouring region-of-interest (CRoI) is typically defined around the target. Many guidelines and multi-institutional studies suggest that this CRoI should comprise a 3 cm axial (1.2 cm craniocaudal for coplanar plans) expansion upon the PTV [6], [7]; OARs falling outside of this do not need to be recontoured daily. It is within this confined space that the relevant high dose fall-off occurs and is more likely to increase risk of toxicity [8].

However, based upon other disease sites and treatment paradigms, such as intracranial and extracranial stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), dose fall-off is actually dependent upon tumor size [9]. For example, in smaller tumors, this may enable a more confined CRoI. In this technical note, we aim to derive an empirical patient-specific CRoI equation, demonstrate its ability to contain all relevant portions of dose fall-off for ART planning dose evaluation, and project contouring time savings at the machine.

2. Materials and methods

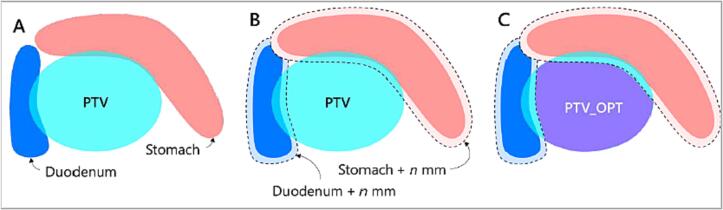

Our institution’s method for stereotactic abdominal ART has been described previously [2], [10], [11]. The patients reviewed in this study were treated with adaptive abdominal SBRT to 50 Gy or 35 Gy in 5 fractions, using both the ViewRay MRIdian (Mountain View, CA) and Varian Ethos (Palo Alto, CA). The patients’ treatment sites included in this study were pancreas (31), liver (20), adrenal (6), retroperitoneal node (3), para-aortic node (2), and spleen (1). The high dose-limiting luminal structures in close proximity were stomach, duodenum, small bowel, and large bowel (SDSL), which were limited to 36 Gy or 25 Gy to 0.5 cm3 of each specific organ when treated to 50 Gy or 35 Gy, respectively. This dose limit was approximately 72 % of the prescription isodose line (72 %IDL) in both scenarios. All patients included in this study respected this SDSL dose limit. To achieve these dosimetric goals, an optimization structure called the PTV_Opt was generated by subtracting the SDSL, plus a 5 mm margin, from the PTV.

However, when factoring in target volume, this 72 %IDL volume will actually be patient-target-dependent, and should roughly follow a logarithmic trend based upon target size [8]. Borrowing from similar experience evaluating SBRT dose gradients by target size, RTOG 0813 provides a useful table that relates the ratio of the 50 % prescription isodose volume to the PTV volume (R50%). This R50% value is indeed dependent upon the PTV volume. Using this validated table as our starting point for custom CRoIs, we multiplied the PTV volume by the R50% to get the volume of the 50 % isodose. We then extracted both the 50 % and 72 % isodose volumes from the initial plans from 113 pancreatic patients who were treated using a stereotactic ART technique at our institution, to calculate the ratio between the 50 % and 72 % volume. This ratio was then used to convert the volume derived in the RTOG 0813 trial to that specific to our treatment technique. We added one standard deviation to this ratio to be more conservative.

Since the RTOG 0813 was described for lung, we then multiplied this volume value by the ratio of densities for water to lung (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

We subsequently logarithmically fitted the above equation for the volumes and the equivalent uniform radius. However, we often compromise PTV coverage to safely keep the 72 %IDL away from the SDSL, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This often creates more high dose spill away from the target. Due to this, the fitted logarithmic function is multiplied by the ratio of the PTV volume to PTV_Opt volume, which factors in this plan complexity on an individual target basis (Eq. (2)). The equation requires two simple inputs to calculate the final CRoI radius.

| (2) |

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the approach for abdominal adaptive radiotherapy [11].

If the equation calculated a result greater than 3 cm, we would limit the CRoI radius to 3 cm, which had been the standard at our institution for contouring during adaptive replanning. We applied this CRoI radius to a set of 60 patients. The majority of patients had multiple adaptive fractions, which allowed us to evaluate the robustness of this method. The volume of the 72 %IDL extending beyond the newly defined CRoI was calculated. For any scenarios where the 72 %IDL was found outside the CRoI, details were gathered to determine what clinical factors impacted deviation. Finally, expected contouring time-savings were projected from this method by applying a volumetric ratio of the CRoI radius from the patient-specific CRoI to the traditional 3 cm CRoI radius. This volumetric ratio assumes a cylindrical volume with the height of the CRoI staying the same while the radius changes (Eq. (3)). The average contour time of 11.93 min was extracted from the paper by Güngör et al. [3].

| (3) |

Results

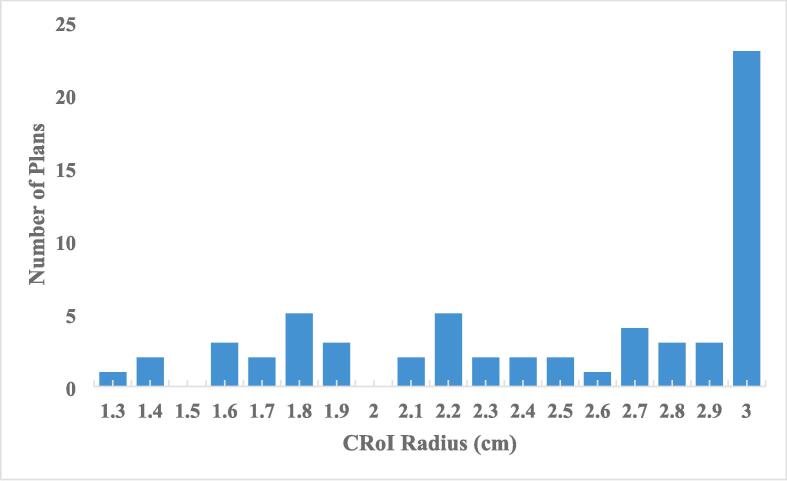

The majority of patients, 37, had CRoIs less than the radius limit of 3 cm. One patient had a 3 cm calculated CRoI while 22 patients had the 3 cm radius cut-off applied. The distribution of patient specific CRoI radii are presented in Fig. 2. Among the 60 patients, there were 301 unique treatment plans on which to test the new CRoI method. Of the 301 unique treatment plans, 284 (94.4 %) plans contained the 72 %IDL volume within the CRoI. Only 5 patients had plans that were outside the CRoI, 2 of which had 72 %IDL outside the CRoI in the initial plan. The treatment sites that had the 72 %IDL extend beyond the CRoI were adrenal (2), pancreas (1), liver (1), and retroperitoneal node (1). The median volume of 72 %IDL outside the CRoI for those cases was 3.1 cm3 [0.1 cm3-15 cm3]. For these 5 patients, the CRoI size was less than 3 cm. In 4 of the 5 above mentioned cases, a 3 cm CRoI would have sufficiently contained the 72 %IDL.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the contouring region-of-interest radii across all patient plans.

Of the 5 patients with 72 %IDL outside the CRoI, 1 had prior irradiation and 2 had stricter than normal volumetric constraints of nearby structures that resulted in increased dose spill to achieve the volumetric constraints. The other 2 patients had technical/planning limitations such as larger patient and target size (35 cm diameter & 444.2 cm3) and distance off-axis (13.5 cm), respectively, that limited conformal treatment plans within the CRoI. In all five patients that had 72 %IDL outside the CRoI, all SDSL were still spared from the 72 %IDL. Thus, use of the custom CRoIs would have been clinically safe in each of these cases. In summary, treatment plans that had more restrictive OAR dosing or had technical machine limitations increased the likelihood of 72 %IDL extending outside the CRoI.

When using a standard 3 cm radius CRoI approach, the projected average total time spent re-contouring was 59.8 h. However, with Eq. (2) applied (use of a custom CRoI), there was an average of a 2.9-min-per case decrease in contouring/patient-on-table time across all patients. Excluding patients with a 3 cm radius, the average time saving would be greater per case. This led to an average total projected time of 45.3 h across the 301 cases, or a 14.5-hour time savings for the clinic.

4. Discussion

In this study, we derived and evaluated patient-specific CRoIs for contour review and editing within the setting of stereotactic ART for abdominal treatment sites. For the majority of patients, we can utilize a CRoI smaller than an established standard within the field with minimal dosimetric consequences. Additionally, we have shown that this will lead to an anticipated reduction in ART planning and patient on-table time.

At this moment, there is minimal guidance within the field regarding appropriateness or accuracy of contouring during adaptation that accounts for both relevant dosimetric assessment as well as ensuring efficiency and limited on-table time [12], [13]. This contouring assessment is also site, dose, and clinical scenario dependent which further limits a single approach for all scenarios. For example, there are suggestions of contouring all OARs within 2 cm of prostate targets or 1.5 cm superior to bladder targets [14], [15]. For pancreas, machine-learning applications determined contouring extent (3 cm radial) for pancreatic stereotactic ART but was developed for a now obsolete MR-guided cobalt machine [6]. These were standard guidelines across all patients and did not account for patient-specific target sizes. However, we know target volumes, surface area, shape complexity, and distance to OARs impact dose fall-off [16], [17], [18] Similar to our approach, population-based empirical equations were developed for spine SBRT to generate gradient margins to properly spare the spinal cord [18]. These studies are not directly applicable to our present work on ART plan optimization, but highlight similar, fundamental principles of plan optimization for SBRT. The treatment planning approach utilized in our study is similar to the methodology used in two separate stereotactic pancreatic ART multi-institutional studies using separate adaptive platforms. This indicates that our work is complementary to and building upon standard planning foundations for online ART. However, our work could benefit from further investigation into the complexity and spatial component of SDSL-PTV overlap on its impact on dose-fall off. Although there is possibility for future refinement, our work further develops this concept of limiting contouring within a certain region for ART to increase efficiency based on a given patient’s anatomy. For certain patients, this will limit on-table time, thus potentially limiting patient movement over the course of treatment and improving patient satisfaction.

Auto-segmentation has the promise to improve the online ART process by limiting the laborious contouring processes [19], [20]. Additionally, it has also led to the exploration of adaptation without contour edits to increase efficiency. In Ethos-based conventional fractionation prostate ART where volumetric goals are used and OAR auto-contouring is in good agreement with expert contours, it is with minimal dosimetric consequence to not edit OARs, thus limiting the need for a CRoI [21]. However, in settings where serial or max dose based objectives are used and within close proximity to the target, such as spinal cord for head and neck treatments, auto-contouring techniques can still have negative dosimetric consequences and still require manually editing [22], [23]. Therefore, even during auto-segmentation review, using a CRoI to focus evaluation would still be a valuable tool during online ART and aid in the efficiency of contour review. These findings are relevant to our study using stereotactic ART within the abdomen where auto-contours that are close to being accurate may still not be clinically acceptable [23].

Due to the empirical nature of our method, the CRoI can be quickly updated during the adaptive process if there are significant changes to patient anatomy. In the setting of stereotactic abdominal ART, there are expected changes in the luminal structures’ positions from day to day such as an approximate median and max displacement of both the small and large bowel of approximately 0.6–1.0 cm and 3.5 cm-4.8 cm, respectively [24]. Due to this high inter-fractional mobility of the luminal OARs, we would expect the dose distributions to change from fraction to fraction. Leading us to conclude that we find it necessary to have a method that can quickly re-update the CRoI size before plan re-optimization to eliminate missed contours that would have received clinically unacceptably high doses.

There are limitations to our work presented here. First, our method does over-estimate CRoI size for certain patients and is corrected by having an upper-bound of the CRoI radius. This is most likely due to the assumptions made during the empirical derivation. In future work, we will incorporate machine learning approaches to further refine appropriate CRoIs for all patients. Second, our calculated time savings were based on estimates and not on prospective data collection. In a future clinical trial, we will include this analysis into our secondary analysis.

We have demonstrated that the use of patient-specific contouring regions of interest can be utilized during the online adaptive planning process. Our institution now clinically uses the patient specific CRoI method for all abdominal stereotactic ART patients. This can potentially minimize time during the course of multiple adaptive fractions within a given day.

5. Statement on ethics board approval

This research was performed under an IRB approved prospective registry (IRB# 2013111222).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Mr. Price reports honoraria and support for travel from Sun Nuclear Corporation, honoraria from ViewRay, Inc., outside the submitted work. Dr. Henke reports honoraria from and participation in an advisory board with ViewRay Inc., grants, honoraria, and consulting fees from Varian Medical Systems, and honoraria and support for travel from LusoPalex outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Kutuk T., Herrera R., Mustafayev T.Z., Gungor G., Ugurluer G., Banu A., et al. Multi-institutional outcomes of stereotactic magnetic resonance image guided adaptive radiation therapy with a median biologically effective dose of 100 Gy10 for non-bone oligometastases. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2022.100978. 100978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudra S., Jiang N., Rosenberg S.A., Olsen J.R., Roach M.C., Wan L., et al. Using adaptive magnetic resonance image-guided radiation therapy for treatment of inoperable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 2019;8:2123–2232. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Güngör G., Serbez İ., Temur B., Gür G., Kayalılar N., Mustafayev T.Z., et al. Time analysis of online adaptive magnetic resonance-guided radiation therapy workflow according to anatomical sites. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021;11:e11–e21. doi: 10.1016/J.PRRO.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meeks S.L., Shah A.P., Sood G., Dvorak T., Zeidan O.A., Meeks D.T., et al. Effect of proposed episode-based payment models on advanced radiotherapy procedures. J Clin Oncol Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e1943–e1948. doi: 10.1200/op.20.00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palm R.F., Eicher K.G., Sim A.J., Peneguy S., Rosenberg S.A., Wasserman S., et al. Clinical medicine assessment of MRI-Linac economics under the RO-APM. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4706. doi: 10.3390/jcm10204706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohoudi O., Bruynzeel A.M.E., Senan S., Cuijpers J.P., Slotman B.J., Lagerwaard F.J., et al. Fast and robust online adaptive planning in stereotactic MR-guided adaptive radiation therapy (SMART) for pancreatic cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2017;125:439–444. doi: 10.1016/J.RADONC.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuong M, Parikh PJ, Lee P, Low DA. Stereotactic MRI-guided On-table Adaptive Radiation Therapy (SMART) for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03621644. Updated November 22, 2021. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03621644.

- 8.Hoyer M., Roed H., Sengelov L., Traberg A., Ohlhuis L., Pedersen J., et al. Phase-II study on stereotactic radiotherapy of locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley J, Gaspar L, Capote R, Jeraj R, Ma C-M, Rogers DWO, et al. RTOG 0813 Protocol.; 2006.

- 10.Hassanzadeh C., Rudra S., Bommireddy A., Hawkins W.G., Wang-Gillam A., Fields R.C., et al. Ablative five-fraction stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable pancreatic cancer using online MR-guided adaptation. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiff J.P., Price A.T., Stowe H.B., Laugeman E., Chin R.-I., Hatscher C., et al. Simulated computed tomography-guided stereotactic adaptive radiotherapy (CT-STAR) for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2022;175:144–151. doi: 10.1016/J.RADONC.2022.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonke J.J., Aznar M., Rasch C. Adaptive radiotherapy for anatomical changes. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2019;29:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glide-Hurst C., Lee P., Yock A.D., Olsen J.R., Cao M., Siddiqui F., et al. Adaptive radiation therapy (ART) strategies and technical considerations: a state of the ART review from NRG oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2021;109:1054–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willigenburg T., de Muinck Keizer D.M., Peters M., Claes A., Lagendijk J.J.W., de Boer H.C.J., et al. Evaluation of daily online contour adaptation by radiation therapists for prostate cancer treatment on an MRI-guided linear accelerator. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2021;27:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricci J.C., Rineer J., Shah A.P., Meeks S.L., Kelly P. Proposal and evaluation of a physician-free, real-time, on-table adaptive radiotherapy (PF-ROAR) workflow for the MRIdian MR-guided linac. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1189. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman D., Dragojević I., Hoisak J., Hoopes D., Manger R. Lung Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) dose gradient and PTV volume: a retrospective multi-center analysis. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:162. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1334-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desai D.D., Cordrey I.L., Johnson E.L. A physically meaningful relationship between R50% and PTV surface area in lung SBRT. Radiat Oncol Phys. 2020;21:45–56. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weksberg D.C., Palmer M.B., Vu K.N., Rebueno N.C., Sharp H.J., Dershan L., et al. Generalizable class solutions for treatment planning on spinal stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2012;84:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne M., Archibald-Heeren B., Hu Y., Teh A., Beserminji R., Cai C., et al. Varian Ethos online adaptive radiotherapy for prostate cancer: early results of contouring accuracy, treatment plan quality, and treatment time. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2021;23:e13479. doi: 10.1002/acm2.13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao W., Riess J., Kim J., Vance S., Chetty I.J., Movsas B., et al. Evaluation of auto-contouring and dose distributions for online adaptive radiation therapy of patients with locally advanced lung cancers. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12:e329–e338. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moazzezi M., Rose B., Kisling K., Moore K.L., Ray X. Prospects for daily online adaptive radiotherapy via ethos for prostate cancer patients without nodal involvment using unedited CBCT auto-segmentation. J App Clin Med Phys. 2021;22:82–93. doi: 10.1002/acm2.13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nash D., Palmer A.L., van Herk M., McWilliam A., Vasquez O.E. Suitability of propagated contours for adaptive replanning for head and neck radiotherapy. Phys Med. 2022;102:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2022.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magallon-Baro A., Milder M.T.W., Granton P.V., den Toom W., Nuyttens J.J., Hoogeman M.S. Impact of using unedited CT-based DIR-propagated autocontours on online ART for pancreatic SBRT. Front Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.910792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam S., Veeraraghavan H., Tringale K., Amoateng E., Subashi E., Wu A.J., et al. Inter- and intrafraction motion assessment and accumulated dose quantification of upper gastrointestinal organs during magnetic resonance-guided ablative radiation therapy of pancreas patients. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2022;21:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.phro.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]