Abstract

This article is based on the lecture for the 2014 American Geriatrics Society Outstanding Scientific Achievement for Clinical Investigation Award. Elder abuse is a global public health and human rights problem. Evidence suggests that elder abuse is prevalent, predictable, costly, and sometimes fatal. This review will highlight the global epidemiology of elder abuse in terms of its prevalence, risk factors, and consequences in community populations. The global literature in PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, BIOSIS, Science Direct, and Cochrane Central was searched. Search terms included elder abuse, elder mistreatment, elder maltreatment, prevalence, incidence, risk factors, protective factors, outcomes, and consequences. Studies that existed only as abstracts, case series, or case reports or recruited individuals younger than 60; qualitative studies; and non-English publications were excluded. Tables and figures were created to highlight the findings: the most-detailed analyses to date of the prevalence of elder abuse according to continent, risk and protective factors, graphic presentation of odds ratios and confidence intervals for major risk factors, consequences, and practical suggestions for health professionals in addressing elder abuse. Elder abuse is common in community-dwelling older adults, especially minority older adults. This review identifies important knowledge gaps, such as a lack of consistency in definitions of elder abuse; insufficient research with regard to screening; and etiological, intervention, and prevention research. Concerted efforts from researchers, community organizations, healthcare and legal professionals, social service providers, and policy-makers should be promoted to address the global problem of elder abuse.

Keywords: AGS award, elder abuse, systematic review

This article is based on the lecture for the 2014 American Geriatrics Society Outstanding Scientific Achievement for Clinical Investigation Award. Elder abuse is a global public health and human rights problem that crosses sociodemographic and socioeconomic strata. Elder abuse, sometimes called elder mistreatment or elder maltreatment, includes psychological, physical, and sexual abuse; neglect (caregiver neglect, self-neglect); and financial exploitation.1 Physical abuse consists of infliction of physical pain or injury to an older adult and may result in bruises, welts, cuts, wounds, and other injuries. Sexual abuse refers to nonconsensual touching or sexual activities with older adults when they are unable to understand, unwilling to consent, threatened, or physically forced into the act. Psychological abuse includes verbal assault, threat of abuse, harassment, or intimidation, which may result in resignation, hopelessness, fearfulness, anxiety, or withdrawn behaviors. Neglect is failure by a caregiver (caregiver neglect) or oneself (self-neglect) to provide the older adult with necessities of life and may result in being underweight or frail, unclean appearance, or dangerous living conditions. Financial exploitation includes the misuse or withholding of an older adult’s resources to their disadvantage or the profit or advantage of another person and may consist of overpayment for goods or services; unexplained changes in power of attorney, wills, or legal documents; missing checks or money; or missing belongings.2

Although elder abuse is a newer field of violence research than domestic violence and child abuse, research indicates that elder abuse is a common, fatal, and costly yet understudied condition.3–6 An estimated 10% of U.S. older adults have experienced some form of elder abuse, yet only a fraction is reported to Adult Protective Services (APS).1

For decades, professionals and the public have viewed elder abuse and broader violence as predominantly social or family problems. Since the first scientific literature citing in the British Medical Journal in 1975,7 there has been increasing attention from public health, social services, health, legal, and criminal justice professionals. In 2003, the National Research Council brought together national experts to examine the state of science on elder abuse and recommended priority strategies to advance the field.8 Despite multidisciplinary efforts to screen, treat, and prevent elder abuse, speed of progress has lagged behind the scope and effect of the issue.

In March 2011, the Senate Special Committee on Aging held a hearing: “Justice for All: Ending Elder Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation.” Based on a Government Accountability Office report,9 individuals who had been abused and experts highlighted the lack of research, education, training, and prevention strategies. The Government Accountability Office estimated that, in 2009, national spending by federal agencies was $11.9 million for all activities related to elder abuse ($1.1 million according to the National Institutes of Health), which is much less than the annual funding for violence against women programs ($649 million) and for child abuse programs ($7 billion).10 On June 14, 2012, the World Elder Abuse Awareness Day commemoration was held at the White House, and President Obama proclaimed the importance of advancing the field of elder abuse.11 In March 2013, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services held a national symposium to highlight elder abuse as a Physician Quality Reporting System measure (#181) to promote screening of elder abuse in healthcare settings.12 In April 2013, the Institute of Medicine held a 2-day workshop dedicated to elder abuse prevention, bringing together global experts to advance the field. In October 2013, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended elder abuse as a research priority area in its report to Congress.13

This review highlights the global epidemiology of elder abuse in terms of its prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. It covers major gaps in research and policy issues for the field of elder abuse and discussed implications for researchers, health professionals, and policy-makers.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Selection

The global literature in PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, BIOSIS, Science Direct and Cochrane Central was searched. The search was limited to studies published in English. Search terms included elder abuse, elder mistreatment, elder maltreatment, prevalence, incidence, risk factors, protective factors, outcomes, and consequences. Review studies were identified and their reference lists examined for relevant articles. Studies existing only as abstracts, case series, or case reports or that recruited individuals younger than 60; qualitative studies; and non-English publications were excluded (online Figure S1).

For prevalence studies, it was not the intention to present every published study in community populations. Rather, this study aimed to demonstrate the heterogeneity of elder abuse definitions and prevalence on the major continents: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. Because there is limited research in developing countries, studies were included from as many different countries as available. For studies in developed countries (e.g., North America and Europe), studies representative of cultural diversity, definitional variations, and psychometric testing and large-scale epidemiological studies were selected.

For risk and protective factors, only studies in which elder abuse was clearly defined as the primary dependent variable, potential confounding factors were considered in the analyses, and the risks and confidence intervals were shown were included. A similar approach was used for consequences, and only studies in which elder abuse was the primary independent variable and confounding factors were used were included. Studies in which primary analyses were bivariate in nature were not included, articles identified using the search methods were independently reviewed, and studies were selected according to the criteria.

Data Synthesis

Epidemiology of Elder Abuse

Elder abuse is a worldwide health problem. Prevalence of elder abuse varies depending on the population, settings, definitions, and research methods (Table 1 and online Figure S2).3,4,14–22 In North and South America, the prevalence of elder abuse in this review ranges from 10% in cognitively intact older adults to 47.3% in older adults with dementia.3,23 In Europe, the prevalence has been found to vary from 2.2% in Ireland to 61.1% in Croatia.24,25 In Asia, the highest 1-year prevalence in this review has been found in older adults in mainland China (36.2%) and lowest was in India (14.0%).21,26,27 Only two studies conducted in Africa have been found, and the prevalence ranged from 30% to 43.7%.20,28 A more-detailed version of Table 1 showing the specific cutoff point methods for prevalence estimates is supplied as online Table S1.

Table 1.

Prevalence Estimates of Elder Abuse According to Population, Survey Method, and Definition

| Author, Year | Population | Age; Sex; Race and Ethnicity | Survey Method | Participation rate, % | Measure | No. item | Cutoff Points | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North/South America | ||||||||

| Dong, 201433 | 3,159 elderly Chinese In Chicago | ≥60; 58.9% female | In person | 91.9 | H-S/EAST, VASS | 10 | ≥1 Items | 15.0% since age 60 |

| Dong, 201433 | 3,159 elderly Chinese In Chicago | ≥60; 58.9% female | In person | 91.9 | CTS; caregiver neglect assessment; financial exploitation assessment | 56 | a | 13.9–25.8% since age 60 |

| Deliema, 201214 | 198 Hlspanics In Los Angeles | ≥66; 56% female | In person | 65 | University of Southern California Older Adult Conflict Scale | 54 | ≥1 items | 1-year, 40.4%; multiple, 21% |

| Dong, 201258 | 4,627 adults in Chicago | ≥65; 64.4% female | In person | N/A | Chicago Elder Self-Neglect Scale | 21 | ≥1 Items | Black: men, 13.2%; women, 10.9% White: men, 2.4%; women, 2.6% |

| Lachs, 201154 | 4, 156 English- or Spanish-speaking community; cognitively Intact older New Yorkers | 60–101; 35.5% female; 19.0% black, 75.5% white, 6.0% Hispanic, 0.8% American Indian, 1.2% Asian | Telephone | N/A | CTS | 31 | a | 14.1% since age 60 |

| Acierno, 20103 | 5,777 cognitively intact U.S. community population | 60–97, 60% female; 88% white, 7% black, 4% Hispanic, 2% American Indian, 1% Asian | Random-diglt dialing and computer-assisted interview | 69 | Interpersonal Violence Measure and Acierno EM Measure | 22 | ≥1 items | Any elder abuse (exclude financial): 10% |

| Wiglesworth, 201023 | 129 older adults with dementia and their caregiver; | 77.1 ± 8.0; 45.7% female; 93.8 white, 8.5% Hispanic | In-person survey of caregivers | N/A | CTS, Elder Abuse Instrument, Self-Neglect Assessment Scale | NA | a | 1-year 47.3%; multiple, 14.6%. |

| Beach, 201037 | 903 U.S. community-dwelling older adults with landline, English-speaking, no severe cognitive Impairment | ≥60; 73.3% female; 23.3% black, 72.8% white, 3.9% other | Random-dlgit dialing, In-person, self-administered | 37.7 | Modified CTS | 12 | a | 6-month financial exploitation, 3.5%; 6-month psychological mistreatment, 8.2% |

| Laumann, 200817 | 3,005 older adults In the National, Social Life, Health and Aging project | 57–85; 51.2% female; 80.7% white, 10.0% black; 6.8% Hispanic; 2.5% other | In-person and mall survey | 75.5 | H-S/EAST, VASS | 3 | ≥1 Items | 1-year: verbal, 9%; financial, 3.5%; physical, 0.2% |

| Buri, 200681 | 498 older adults In the Iowa Medicaid Waiver Program | 65–101; 70.9% female; 96% white, 3% black | Mail survey | 49 | Elder Abuse Screen | 5 | ≥1 items | 20.9%: 1 type, 15.8%; 2 types, 4.0%; 3 types, 1.0% |

| Europe | ||||||||

| Lindert, 201319 | 4,467 older adults from seven countries in Europe | 60–84; 57.3% female | In-person and mail survey | 45.2 | Modified CTS | 52 | ≥1 Items | 1-year, 12.7–30.8% |

| Naughton, 201124 | 2,021 community-dwelling older people In Ireland | ≥65; 55% female | In person | 83 | CTS, UK and NY prevalence studies | NA | a | 1-year, 2.2% |

| Kissai, 201182 | 331 older adults In Izmir, Turkey | ≥65; 56.8% female | In person | N/A | Investigator-determined | 5 | a | 6-month, 13.3% |

| Biggs, 200983 | 2,111 older adults In the community In United Kingdom | ≥66 | In person | 65 | Built on literature | 34 | a | 2.6% with neglect; 1.6% without neglect |

| Ajdukovic, 200925 | 303 older adults in Croatia | 65–97; 76.6% female | In person | NA | Elder Abuse in the Family questionnaire | 20 | NA | 1-year, 61.1% |

| Cooper, 200984 | 220 UK caregivers of people with dementia | 58–99, 72% female | In person | 69 | Modified CTS | 10 | Score ≥2 | 3-month, 52% |

| Garre-Olmo, 200985 | 676 community-dwelling older adults In Girona, Spain | ≥75; 58.2% female. | In person | 82 | AMA Screen | 9 | ≥1 Items | 1-year, 29.3%; 2 types, 3.6%; 3 types, 0.1% |

| Perez Carceles, 200886 | 460 older adults in health center in Spain | ≥65; 53.3% female | In person | N/A | Canadian Task Force, AMA Screen | 19 | ≥1 items | 44.6% |

| Comijs, 199831,32 | 1,797 older people living Independently In Amsterdam, the Netherlands | 69–89; 62.8% female | Interview | 44.4 | CTS, Measure of Wife Abuse, Violence Against Man Scale | NA | a | 1-year, 5.6%; ≥2 types, 0.4% |

| Asia/Austria | ||||||||

| Wu, 201221 | 2,039 Chinese older adults in rural China | ≥60; 59.9% female | In person | 90.8 | H-S/EAST, VASS | NA | ≥1 Items | 1-year, 36.2%; ≥2 types, 10.5% |

| Somjinda Chompunud, 201087 | 233 cognitively functioning older adults in Thailand | 60–90; 73.4% female | In person | 73.3 | Interview guideline for screening for elder abuse | 6 | ≥1 items | 1-year, 14.6%; 1 time, 9.9%; ≥2 times, 4.7% |

| Lowenstein, 200927 | 1,045 community-living older adults from the first national survey In Israel | ≥65; 62.5% female | In person | 75 | CTS2, short situational descriptions, Respondents’ Reactions to Aggression | NA | a | 1-year, 35.0% |

| Oh, 200922 | 15,230 older adults In Seoul, Korea | ≥65; 65.3% female | In person | N/A | Compiled through literature | 25 | ≥2 times | 1-month, 6.3% |

| Lee, 200888 | 1,000 primary caregivers of family members with disabilities In Seoul, Korea | 65–102; 69.5% female | In person | N/A | N/A | 6 | a | Not answered question, 10.5%; yelled, 10.9%; confined, 18%; hit, 9.7%; neglected, 13.6% |

| Dong, 200744 | 412 cognitively intact community-living persons from medical clinics in China | ≥60, 34% female | Self-administered survey | 82.4 | H-S/EAST, VASS | 13 | ≥1 items | 35.2% since age 60; 1 type, 64%; 2 types, 16%; ≥3 types, 20% |

| Sasaki, 200789 | 412 pairs of disabled older adults and family caregivers in Japan | Mean 80.5, 60.1% female | Self-administrated survey | 70.0 | Checklist developed by literature | 9 | ≥1 Items | 6-month, 34.9% |

| Chokkanathan, 200626 | 400 community-living cognitively intact older adults In India | ≥65; 49.5% female | In person | 80 | CTS | 18 | a | 1-year, 14% |

| Yan, 200131 | 355 community-living older adults In Hong Kong, China | ≥60; 62% female | Self-administered | N/A | Revised CTS | 25 | ≥1 items | 1-year, 21.4%; types, 17.1% multiple |

| Africa | ||||||||

| Cadmus, 201220 | 404 elderly women In Oyo state, southwestern Nigeria | ≥60; 100% female; 100% Yoruba | Semistructured questionnaires | N/A | Standardized questionnaire developed by World Health Organization | 18 | Score ≥1 | 1-year, 30% |

| Rahman, 201228 | 1,106 older adults living at home In rural area of Mansoura city, Dakahilia Governate, Egypt | ≥60; 53.2% female | In-person interview | 95.3 | Questionnaire to elicit abuse | 15 | ≥1 Items | 1-year, 43.7%; 1 type, 35.4%; 2 types, 3.8%; 3 types, 3.8%; 4 types, 0.6% |

For detailed table on the definitional criteria for specific subtypes of elder abuse and its prevalence, see online Table S1.

Cutoff varies according to subtype of abuse and more detailed information regarding the cut-off point of each type of abuse please see the appendix.

H-S/EAST = Hwalek-Sengstok Elder Abuse Screening Test; VASS = Vulnerability to Abuse Screening Scale; CTS = Conflict Tactics Scale; AM A = American Medical Association, N/A = not applicable.

Elder abuse is common in minority older adults. Financial exploitation is three times as high and psychological abuse four times as high in black populations.4 A study of Hispanics indicated that 40% had experienced elder abuse, yet only 2% was reported to authorities.14 In a study of 4,627 older adults in the Chicago Health and Aging Project, older black men were three times as likely to experience elder self-neglect as older white men, and older black women were two times as likely to report elder self-neglect as older white women.16 In a Chinese population, despite cultural expectations of filial piety, 35% of older adults self-reported elder abuse.29 Understanding culturally specific elements of elder abuse will be critical to designing prevention and intervention strategies used in culturally specific contexts.

Although there is no consensus on a singular measure, the Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS)30 remains one of the most widely used to measure physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. Despite using the same measurement, the cutoff point for definite elder abuse differs greatly across studies, leading to large variation in prevalence estimates. For instance, one study used the revised CTS and regarded older adults who endorsed any item of the measurement as having experienced verbal abuse and found a 1-year prevalence of 21%.31 Another study used the modified CTS but included those who endorsed 10 or more items as having experienced psychological abuse and therefore found a 1-year prevalence of only 1.2%.24 A third likewise used the “10 or more items” criteria and suggested a 1-year prevalence of psychological abuse of 3.2%.32 Such inconsistency in definitions was also observed in measuring elder neglect, with some studies using the “any item” approach and others using the “10 or more items” approach. In comparison, the operational definitions of physical and sexual abuse remain more consistent across studies, with the majority of studies using the “any item” approach. A recent study used different operational definitions to examine elder abuse and its subtypes in the same population cohort and suggested that the prevalence of elder abuse and its subtypes varied with the strictness of the definition.33

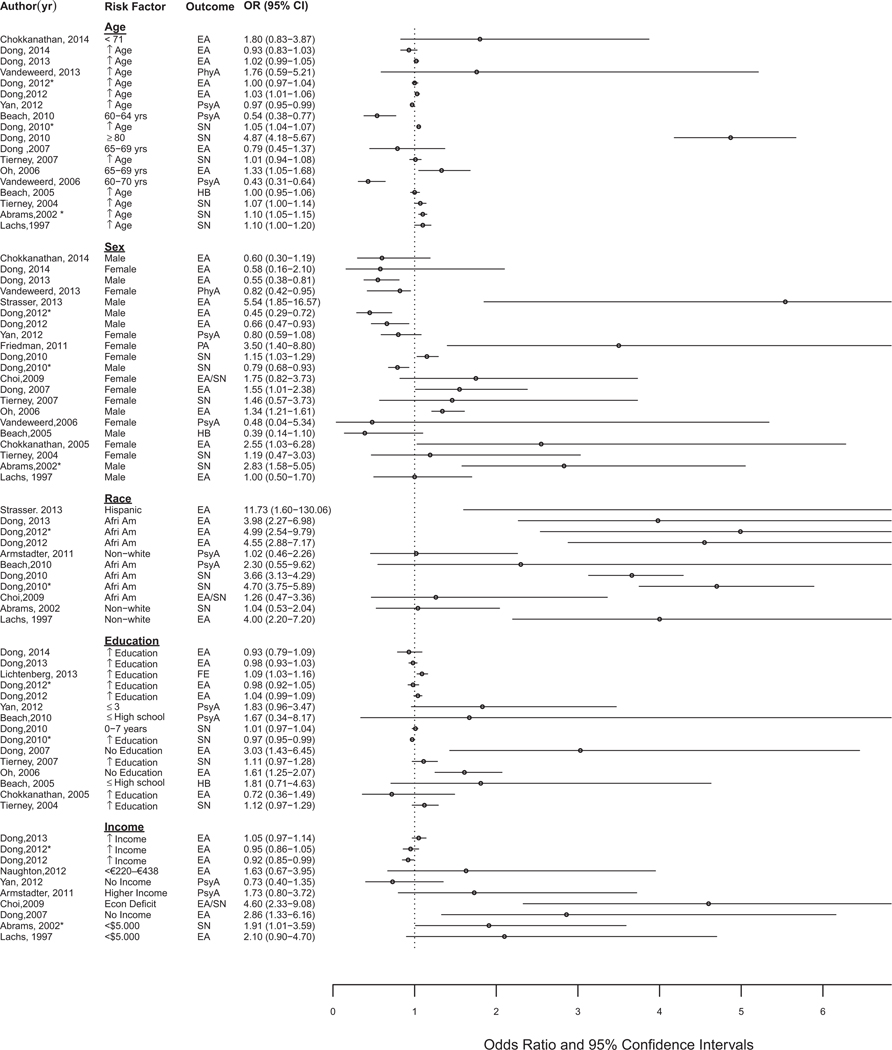

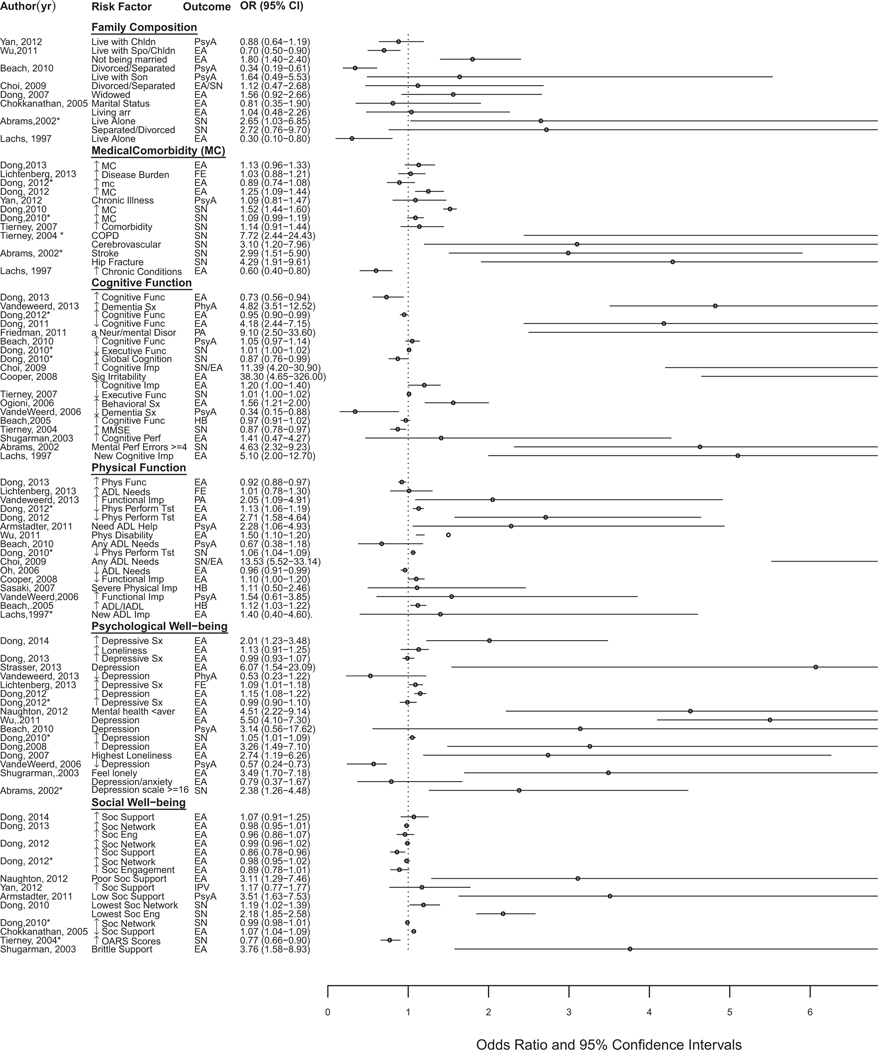

Risk factors for elder abuse are highlighted in Table 2 and visually plotted in Figure 1. Associations between sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics and elder abuse have been inconsistent.4,22,24, 26,34–36 Physical function impairment has been linked with elder abuse,37–43 as has psychological distress and social isolation.36,40,44–47 Of various risk factors, cognitive impairment seemed to be consistently associated with greater risk of elder abuse. For example, 254 caregivers and 76 older adults with dementia were surveyed, and it was found that older adults with Alzheimer’s disease were 4.8 times as likely to experience elder abuse as those without.48 Another study assessed 2,005 samples of reported APS cases and found that cognitive impairment was significantly associated with elder self-neglect.49 The wide variations of odds ratios and confidence intervals in Figure 1 represent the diversity of the studies with respect to population, sample size, settings, definitions, and categorization of independent and dependent variables.

Table 2.

Risk Factors Associated with Elder Abuse (EA)

| Author, Year | Type | Study Description | Age; Sex; Race | Independent Variables | Outcome | Confounding Factors | Key Findings of Risk for EA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dong, 201258 | PS | 6,159 elderly adults from CHAP | ≥65; 61% female | Physical function | EA | Sociodemographic, medical conditions, depressive symptoms, social network and social participation | Physical performance testing (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.06–1.19), lowest tertile of physical performance testing (OR = 4.92, 95% CI = 1.39–17.46) |

| Dong, 201034 | PS | 5,519 elderly adults from CHAP | ≥65; 61% female; 64% black | Cognitive function | SN | Sociodemographic, medical condition, physical function, depression, social networks | Executive function (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00–1.02) |

| Dong, 201034 | PS | 5,570 elderly adults from CHAP | ≥65; 66.9% female | Physical function | SN | Sociodemographic, medical condition, depression, cognition, social networks | Decline in physical performance (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04–1.09), increase in Katz impairment (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.03–1.13), Rosow-Breslau impairment (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.14–1.32), Nagi impairment (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.02–1.13) |

| Tierney, 200743 | PS | 130 community-living participants who scored <131 on DRS | ≥65; 70.8% female | Executive function, judgment, attention and concentration, verbal fluency | SN | Age, sex, education, Charlson Comorbidity Index, MMSE | Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test recognition (OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.89–0.98), Trail-Making Test Part B (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00–1.02), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised similarities (OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.81–0.98) |

| Tierney, 200490 | PS | 139 community-living adults who scored <131 on DRS | ≥65; 70.8% female | MMSE, medical conditions, medications, OARS | SN | Age, sex, education, international classification of disease, Charlson index, OARS, MMSE | Higher MMSE score (OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.78–0.97), chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (OR = 7.72, 95% CI = 2.44–24.43), higher OARS score (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.66–0.89), stroke (OR = 3.09, 95% CI = 1.20–7.96) |

| Abrams, 200235 | PS | 2,812 elderly adults from New Haven EPESE cohort | ≥65; 65.4% female | Depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment | SN | Age, sex, race, education, income, marital status, living situation, medical morbidity | Depressive symptoms (CES-D score ≥16) (OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.26–4.48), cognitive impairment (≥4 errors on the Pfeiffer Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, OR = 4.63, 95% CI = 2.32–9.23) |

| Lachs, 199742 | PS | 6,222 elderly adults in EPESE cohort | ≥65; 64.8% female | ADL impairment, cognitive disability | EA | Age, sexual, race, and income | New ADL impairment (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.4–4.6), new cognitive impairment (OR = 5.1, 95% CI = 2.0–12.7) |

| Dong, 201433 | CS | 78 older Chinese in United States | ≥60; 52% female | Depressive symptomatology | EA | Sociodemographic, marital status, health status, quality of life, physical function, loneliness and social support | Depressive symptomatology (OR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.23–3.48) |

| Chokkanathan, 201426 | CS | 902 older adults in Nadu, India | ≥61; 54.3% female | Older adults: physically abuse family members Family members: age, education, alcohol consumption, mistreatment of other family members Environment: family cohesion, stress | EA | Older adults (age, sex, employment, dependency, physically abused) Family member (age, education, alcohol use, mistreat others) Environment (family cohesion, family stress, wealth index) | Older adults: physically abusing family members (OR = 9.06, 95% CI = 2.82–29.04) Family members: middle age (OR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.01–4.23), tertiary education (OR = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.11–0.97), alcohol (OR = 3.08, 95% CI = 1.68–5.70), mistreatment of other family (OR = 6.24, 95% CI = 2.11–18.41), reported more conflicts with their family members (OR = 14.14, 95% CI = 6.63–30.14), low family cohesion (OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.43–2.15) |

| Dong, 201361 | CS | 10,333 older adults in Chicago | ≥65; 39% female | Elder self-neglect | EA | Sociodemographic, medical comorbidities, cognitive and physical function and psychosocial well-being | Elder abuse (OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.18, 2.59), financial exploitation (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.01, 2.95), caregiver neglect (OR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.24, 3.52), multiple forms of elder abuse (OR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.22, 3.48) |

| Lichtenberg, 201391 | CS | 4,440 older adults from Health and Retirement Study | Mean 65.8; 61.9% female; 85.4% white | Education, depressive symptoms, financial satisfaction, social needs | Financial abuse | Sociodemographic, marital status, CES-D, physical function, self-rated health, financial status, psychological factors | More education (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.03–1.16), more depressive symptoms (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01–1.18), less financial satisfaction (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.63–0.90), greater ADL needs (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.78–1.30), greater disease burden (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.88–1.21) |

| Strasser, 201347 | CS | 112 older adults who participated in legal program | ≥60; 68.2% female | Sex, ethnicity, depression depression, visits to a mental health provider | EA | Sex, ethnicity, cohabitation, | Male (OR = 5.54, 95% CI = 1.85–16.57), Hispanic (OR = 11.73, 95% CI = 1.06–130.06), depression (OR = 6.07, 95% CI = 1.54–23.09) |

| Vandeweerd, 201348 | CS | 254 caregivers and 76 older adults with dementia | ≥60; 59% female, 85% white, 10.3% Hispanic, 4.5% black | Sex, functional Impairment, dementia symptoms, violence by older adult, self-esteem, caregiver alcoholism | Phy A | Sex, number of dementia symptoms, level of functional Impairment, violence by older adult, caregiver self-esteem, caregiver alcoholism | Sex (OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.42–0.95), functional Impairment (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.09–4.91), dementia symptoms (OR = 4.82, 95% CI = 3.51–12.52), older adults used violence OR = 4.167 (2.18–8.40), depression (OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.23–1.22), caregiver with high self-esteem (OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.59–8.40) |

| Dong, 201260 | CS | 8,932 elderly adults from CHAP | ≥65; 76% female | Physical function | EA | Soclodemographlc, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes mellltus, stroke, cancer, hip fracture, depression symptoms | Lowest level of physical performance testing: EA (OR = 2.71, 95% CI = 1.58–4.64) psychological abuse (OR = 2.69, 95% CI = 1.27–5.71), caregiver neglect (OR = 2.66, 95% CI = 1.22–5.79), financial abuse (OR = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.21–4.55) |

| Naughton, 201224 | CS | 2,021 older people In Ireland | ≥65; 55% female | Mental health, social support | EA | Age, sex, Income, physical health, mental health, social support | Mental health below average (OR = 4.51, 95% CI = 2.22–9.14), lower social support (OR = 3.11, 95% CI = 1.29–7.46) |

| Wu, 201221 | CS | 2,039 adults In three rural communities In Hubei, China | ≥60; 59.9% female | Marital status, physical disability, living arrangement, depression | EA | Education, living status, living source, chronic disease, physical disability, labor Intensity, depression | Not being married (OR = 1.80, 95% CI = 1.40–2.40), physical disability (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.10–2.20), living with spouse and children (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.50–0.90), depression (OR = 5.50, 95% CI = 4.10–7.30) |

| Yan, 201231 | CS | 937 married or cohabiting older adults In Hong Kong | ≥60; 42.4% female | Age, sex, education, Income, living arrangement, chronic Illness, social support | Intimate partner violence | Sociodemographic, living arrangement, Immigrants or not, employment, receiving social security, Indebtedness, chronic Illness, social support | Age (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95–0.99), female (OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.59–1.08), education levels ≤3 years (OR = 1.83, 95% CI = 0.96–3.47), no Income (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.40–1.35), living with children (OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.64–1.19), chronic Illness (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.81 –1.47), lower social support (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.77–1.77) |

| Amstadter, 201192 | CS | 902 community-dwelling older adults | 60–97; 59.9% female; 77% white, 17.3% black, 1.9% Native American, 0.1% Aslan | Functional status, race, social support, and health status | Psychological, financial abuse | Age, income, having experienced prior traumatic event | Emotional mistreatment: low social support (OR = 3.51, 95% CI = 1.63–7.53), needing assistance with ADLs (OR = 2.28, 95% CI = 1.06–4.93) Neglect: nonwhite (OR = 3.49, 95% CI = 1.37–8.89), low social support (OR = 6.74, 95% CI = 1.54–29.62), poor health (OR = 3.79, 95% CI = 1.46–9.81) Financial exploitation: needing assistance with ADLs (OR = 2.75, 95% CI = 1.17–6.48) |

| Dong, 201116 | CS | 8,932 elderly adults from CHAP | ≥65; 76% female | Cognitive function | EA | Sociodemographic, medical conditions, depressive symptoms, social network, social participation | Lowest turtles of cognition (OR = 4.18, 95% CI = 2.44–7.15), lowest levels of global cognitive function and physical abuse (OR = 3.56, 95% CI = 1.08–11.67), emotional abuse (OR = 3.02, 95% CI = 1.41–6.44), caregiver neglect (OR = 6.24, 95% CI = 2.68–14.54), financial exploitation (OR = 3.71, 95% CI = 1.88–7.32) |

| Friedman, 201141 | CS | 41 elderly adults from trauma unit In Chicago and 123 controls from trauma registry | ≥60; 58.5% female | Having a neurological or mental disorder | Physical abuse | Age, Injury severity, hospital, length of stay | Eurological or mental disorder (OR = 9.10, 95% CI = 2.50–33.60) |

| Beach, 20104 | CS | Population-based survey of 903 adults in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania | ≥60, 73% female, 23% black, 73% white, 4% other | Race | Psychological abuse | Sociodemographic, marital status, household composition, cognitive function, physical disability, and depression symptoms | Black race (OR = 2.30, 95% CI = 0.55–9.62) |

| Choi, 200949 | CS | Assessment of 2,005 samples reported to APS for self-neglect | ≥60; 64.4% female; 44.2% white, 15.9% black, 27.5% Hispanlc | Economic resources, healthcare and social service programs | SN | Age, sex, race, marital status, language, living arrangement | Economic resource deficit (OR = 4.60, 95% CI = 2.33–9.08), any ADL Impairment (OR = 13.53, 95% CI = 5.52–33.14), cognitive Impairment (OR = 11.39, 95% CI = 4.20–30.90) |

| Dong, 20095 | CS | 9,056 elderly adults from CHAP cohort | ≥65; 62.2% female | Social networks, social engagement | SN | Age, sex, race, education, medical morbidity, physical function, depression, body mass Index | Lower social network (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.01–1.04), lower social participation (OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.09–1.22) |

| Oh, 200922 | CS | 15,230 older adults In Seoul, Korea | ≥65; 65.3% female | Sex, age, support, physical function, health, living arrangement, economic level, family relationships | EA | Elderly: sex, age, education, economic capacity, ADLs, lADLs, sick days Family: household type, economic level, family relations | Older men (OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.21–1.61), aged 65–69 (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.05–1.68), partially supported (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.57–0.96), ADLs (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.91–0.99), lADLs (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.00 –1.06), living with family of married children (OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.16–3.32), lowest economic level (OR = 4.84, 95% CI = 3.03–7.75), good family relations (OR = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.01–0.04) |

| Cooper, 200893 | CS | 86 community-living adults with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers | Mean 82.4; 69.8% female | Caregiver: sex, burden Care recipient: behavioral, cognitive, physical function | EA | Caregiver: burden, anxiety Care recipient: receiving 24-hour care, ADLs, Irritability | Caregiver: male (OR = 6.80, 95% CI = 1.70—27.80), reporting greater burden (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.00–1.10) Care recipient: clinically significant Irritability (OR = 38.30, 95% CI = 4.60–326.00), less functional Impairment (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.00–1.20), greater cognitive Impairment (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.00–1.40) |

| Dong, 200894 | CS | 412 Individuals In n urban medical center In Nanjing, China | ≥60; 34% female | Depression | EA | Age, Income, number of children, level of education | Dissatisfaction with life (OR = 2.92, 95% CI = 1.51–5.68), being bored (OR = 2.91, 95% CI = 1.53–5.55), feeling helpless (OR = 2.79, 95% CI = 1.35–5.76), feeling worthless OR = 2.16, (1.10–4.22), depression (OR = 3.26, 95% CI = 1.49–7.10) |

| Dong, 200744 | CS | 412 adults In a medical clinic In Nanjing, China | ≥60; 34% female | Loneliness | EA | Age, sex, education, Income, marital status, depressive symptoms | Loneliness (OR = 2.74, 95% CI = 1.19–6.26), lacking companionship (OR = 4.06, 95% CI = 1.49–11.10), left out of life (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.01–2.84) |

| Dong, 200744 | CS | 412 adults in a medical clinic in Nanjing, China | ≥60; 34% female | Age, sex, education, Income, marital status | EA | Age, sex | Aged 65–69 (OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.45–1.37), female (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.01–2.38), illiterate (OR = 3.03, 95% CI = 1.43–6.45), no Income (OR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.33–6.16), widowed (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 0.92–2.66) |

| Ogioni, 200795 | CS | 4,630 adults receiving home care In Italy | ≥65; 59.6% female | Behavioral symptoms | EA | Age, sex, marital status, ADLs, cognition, delirium, depression, medical condition, loneliness, distress, social support, pain | Behavioral symptoms (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.21–2.00) |

| Sasaki, 200789 | CS | 412 pairs of disabled older adults and caregivers In Japan | Mean 80.5; 60.1% female | Behavioral disturbance, adult child as caregiver | Potentially harmful behaviors | Severity of physical impairment, hearing problems, caregiver burden | Greater behavioral disturbance (OR = 3.61, 95% CI = 1.65–7.90), adult child as caregiver (OR = 2.69, 95% CI = 1.23–5.89) |

| VandeWeerd, 200648 | CS | 254 caregivers and 76 elderly adults | Mean 78.6, 59% female | Age, sex, cognitive Impairment, physical function, depression | Psychological abuse | Age, sex, race, dementia symptoms, functional impairment, depression, medication, verbal aggression, violence | Age (OR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.31–0.64), sex (OR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.04–5.34), number of dementia symptoms (OR = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.15–0.88), level of functional Impairment (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 0.61–3.85), depression (OR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.24–0.73) |

| Beach, 200537 | CS | 265 caregiver-care recipient dyads for impaired, community-dwelling family members | ≥60; 58% female | ADL and IADL needs, caregiver cognitive impairment, caregiver physical symptoms, caregiver depression | Potentially harmful behaviors | Care recipient age, sex, education, cognitive status self-rated health Caregiver age, sex, education, self-rated health | Greater care recipient ADL and IADL needs (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.03–1.22), spouse caregiver vs other (OR = 8.00, 95% CI = 1.71–37.47), greater caregiver cognitive impairment (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.04–1.38), more caregiver physical symptoms (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.01–1.13), caregiver at risk for clinical depression (OR = 3.47, 95% CI = 1.58–7.62) |

| Chokkanathan, 200526 | CS | 400 community-living cognitively intact older adults In Chennai, India | 60–90; 73.4% female | Sex, social support, subjective physical health | EA | Sex, marital status, education, living status, subjective health, income, social support | Female (OR = 2.55, 95% CI = 1.03–6.28), less social support (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.04–1.09), poorer subjective health status (OR = 3.26, 95% CI = 1.43–7.42) |

| Shugarman, 200346 | CS | 701 adults seeking home- and community-based services in Michigan | ≥60; 71.3% female | Memory problems, disease, abuses alcohol, not at ease Interacting with others, expresses conflict with family or friends, Indicates feels lonely, brittle support system | EA | Sex, cognitive symptoms, disease diagnoses, physical functioning, behavioral problems, social functioning, support | Memory problems (OR = 2.66, 95% CI = 1.28–5.34), psychiatric disease (OR = 2.48, 95% CI = 1.18–5.23), alcohol (OR = 10.26, 95% VI=2.73–38.5), not at ease Interacting with others (OR = 2.75, 95% CI = 1.21–6.21), conflict with family or friends (OR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.08–4.23), lonely (OR = 3.49, 95% CI = 1.70 –7.18), brittle support (OR = 3.76, 95% CI = 1.58–8.93) |

| Comijs, 199932 | CS | 147 elderly adults reporting chronic verbal aggression, physical aggression, and financial abuse in Amsterdam | ≥65 | Hostility and coping capacity | EA | Age, sex, other matching variables (Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, Utrechtse Copinglijst) | Verbal aggression: direct aggression (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.05–1.62), locus of control (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.01–1.41) Physical aggression: coping (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.01–1.51), avoidance (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.08–1.47) Financial mistreatment: Indirect aggression (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.07–1.42), perceived self-efficacy (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.02–1.20) |

PS = prospective; CS = cross-sectional; CHAP = Chicago Health Aging Project; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; SN = self-neglect; DRS = Dementia Rating Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; OARS = Older American Resources and Services; EPESE = Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; ADL = activity of daily living; IADL = instrumental activity of daily living; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale.

Figure 1.

Risk Factors for Elder Abuse.

Elder abuse is associated with significant adverse health outcomes (Table 3), including psychosocial distress,50–52 morbidity, and mortality.5,53–55 Two longitudinal cohort studies have demonstrated and association between elder abuse and premature mortality,5,54 especially in black populations.56 Elder abuse is also associated with greater health service use;57–59 especially emergency department use60 and hospitalization and 30-day readmission rates.58,59,61 See online Appendix for references for Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Table 3.

Consequences of Elder Abuse (EA)

| Author, Year | Type | Study Description | Age; Sex; Race | Predictor | Outcomes | Confounding Factors | Critical Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schofield, 201396 | PS | 1,266 older women In Australia | 70–75; 100% female | EA | Disability mortality | Demographic factors, social support, health behaviors, health condition | Mortality: coercion (HR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.06–1.40), dejection (HR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.03–1.23) Disability: vulnerability (HR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.06–1.49), dejection (HR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.38–1.73) |

| Dong, 201260 | PS | 6,864 community-living older adults participating In CHAP | ≥65; 61% female | SN | Emergency department use | Soclodemographlc, medical conditions, cognitive and physical function | SN (RR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.29–1.58), greater SN severity (mild: PE = 0.27, SE = 0.04, P< .001; moderate: PE = 0.41, SE = 0.03, P < .001; severe: PE = 0.55, SE = 0.09, P< .001) |

| Dong, 201097 | PS | 7,841 community-older adults participating In CHAP | ≥65, 52.6% female | EA | All-cause mortality across levels of depression, social network, social participation | Soclodemographlc, medical conditions, weight loss, marital status, cognitive and physical function, smoking, alcohol Intake | CES-D fertile: highest (HR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.36–4.36), middle (HR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.19–3.99), lowest (HR = 1.61, 95% CI = 0.79–3.27) Social network fertile: lowest: (HR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.52–3.85), middle (HR = 2.65, 95% CI = 1.52–4.60), highest (HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.36–2.61) Social engagement fertile: lowest: (HR = 2.32, 95% CI = 1.47–3.68), middle (HR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.41–4.77), highest (HR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.52–2.72) |

| Mouton, 201051 | PS | 93,676 from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study | 50–79; 100% female | Physical, verbal abuse | Depressive symptoms, MCS score | Soclodemographlc, marital status, smoking, alcohol, religion comfort, living alone, baseline psychosocial characteristics | Physical abuse: 3-year change In depressive symptoms (PE = 0.20, 95% CI = −0.21–0.60), change In MCS score (PE = −1.12, 95% CI = −2.45 to −0.21) Verbal abuse: 3-year change In depressive symptoms (PE = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.11–0.24), change In MCS score (PE = 0.55, 95% CI = −0.75 to −0.34) Physical and verbal abuse: 3-year change In depressive symptoms (PE = 0.15, 95% CI = −0.05 to 0.36), change In MCS score (PE = −0.44, 95% CI = −1.11 to −0.22) |

| Baker, 200953 | PS | 160,676 community women from WHI | 50–79; 100% female | Physical, verbal abuse | All-cause, cause-specific mortality | Sociodemographic, BMI, smoking, alcohol, health status, medical conditions, frailty, and psychosocial factors | Physical abuse (HR = 1.40, 95% CI = 0.93–2.11), verbal abuse (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.94–1.10), physical and verbal abuse (HR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.86–1.33) |

| Dong, 20095 | PS | 9,318 community-older adults participating in CHAP | ≥65; 61% female | EA, SN | All-cause mortality, cause-specific mortality, mortality stratified according to cognitive and physical function | Sociodemographic, medical conditions, weight loss, marital status, cognitive and physical function, BMI, CES-D, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, social well-being | SN: 1-year mortality (HR = 5.76, 95% CI = 5.11–6.49), >1-year mortality (HR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.64–2.14) SN severity: mild (HR = 4.71, 95% CI = 3.59–6.17), moderate (HR = 5.87, 95% CI = 5.12–6.73), severe HR = 15.47, 95% CI = 11.18–21.41). EA: all-cause mortality (HR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.48–2.88), cardiovascular mortality (HR = 3.86, 95% CI = 2.04–7.29) |

| Schofield,200455 | PS | 10,421 older women in Australia | 73–78; 100% female | EA | Physical function, bodily pain, general health, social function, role emotional difference, mental health difference, PCS T2–1, MCS T2–1 difference | Baseline Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Survey scores, four EA scores, age, sum of acute illnesses, chronic conditions, life events, stress score, violent relationship, BMI, smoking, marital status, education, country of birth | Dejection predicted physical function (β = −2.81, SE = 0.81), bodily pain (β = −1.99, SE = 0.97), general health (β = −1.61, SE = 0.70), vitality (β = −3.54, SE = 0.71), social function (β = –5.27, SE = 1.00), role emotional difference (β = −7.88, SE = 1.60), mental health difference (β = −4.63, SE = 0.60), PCS T2–1 difference (β = −0.75, SE = 0.36), MCS T2–1 difference (β = −0.41, SE = 0.74), |

| Lachs, 200257 | PS | 2,812 community-living older adults from New Haven EPESE cohort | ≥65; 58.4% female | EA, SN | Long-term nursing home placement | Sociodemographic, BMI, medications, physical and cognitive function, social ties, incontinence, CES-D, emotional support, chronic conditions | SN (HR = 5.23, 95% CI = 4.07–6.72), EA (HR = 4.02, 95% CI = 2.50–6.47) |

| Lachs, 199818 | PS | 2,812 community-living older adults from New Haven EPESE | ≥65; 58.4% female | EA, SN | All-cause mortality | Sociodemographic, chronic conditions, BMI, cognition, psychosocial well-being | SN (OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.20–2.50), EA (OR = 3.10, 95% CI = 1.40–6.70) |

| Dong, 201361 | CS | 6,674 community-living older adults participating in CHAP | ≥65; 58.4% female; 56.3% black | EA; psychological, financial abuse; neglect | Hospitalization | Sociodemographic, medical comorbidities, cognitive and physical function, psychological well-being | Elder abuse (RR = 2.72, 95% CI = 1.84–4.03), psychological abuse (RR = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.44–3.43), financial exploitation (RR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.06–2.90), caregiver neglect (RR = 2.43, 95% CI = 1.60–3.69), ≥2 types of elder abuse (RR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.82–3.66) |

| Dong, 201361 | CS | 10,333 community-older adults participating in CHAP | ≥65; 39% female | SN | EA | Sociodemographic, medical comorbidities, cognitive and physical function, psychosocial | EA (OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.19–2.59), financial exploitation (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.01–2.95), caregiver neglect (OR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.24–3.52), multiple forms of EA (OR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.22–3.48) |

| Dong, 201361 | CS | 6,674 community-older adults participating in CHAP | ≥65; 58.4% female | EA | Rate of emergency department use | Sociodemographic, comorbidities, cognitive and physical function, psychosocial | EA (RR = 2.33, 95% CI = 1.60–3.38), psychological abuse (RR=1.98, 95% CI = 1.29–3.00), financial exploitation (RR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.01–2.52), caregiver neglect (RR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.38–2.99) |

| Dong, 201361 | CS | 6,674 community-older adults participating in CHAP | ≥65; 58.4% female | EA | Rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities | Sociodemographic, medical comorbidities, cognitive and physical function, psychosocial | EA (RR = 4.60, 95% CI = 2.85–7.42), psychological (RR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.17–4.56), physical (RR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.19–4.66), financial (RR = 2.81, 95% CI = 1.53–5.17), neglect (RR = 4.73, 95% CI = 3.03–7.40) |

| Olofsson, 201252 | CS | 9,360 older adults from nationwide public health survey in Sweden | 65–84; 53.1% female | Psychological and physical abuse | Physical and mental health, use of healthcare | Age, civil status, work history, smoking | Psychological abuse (women): poor general health (OR = 3.80, 95% CI = 2.70–5.30), anxiety (OR = 6.30, 95% CI = 3.70–11.00), stress (OR = 6.30, 95% CI = 4.20–9.30), GHQ-12 (OR = 5.90, 95% CI = 4.40–7.90), suicidal thought (OR = 3.50, 95% CI = 2.30–5.20), use of healthcare (OR = 2.60, 95% CI = 1.90–3.50) Physical abuse (women): anxiety (OR = 7.40, 95% CI = 3.60–15.0), sleeping problem (OR = 2.30, 95% CI = 1.40–4.50), stress (OR = 3.80, 95% CI = 1.90–7.60), GHQ-12 (OR = 4.00, 95% CI = 2.40–6.70), pharmaceutical (OR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.20–3.40), use of healthcare (OR = 1.80, 95% CI = 1.00–3.10). Psychological abuse (men): poor general health (OR = 2.20, 95% CI = 1.40–3.40), anxiety (OR = 10.00, 95% CI = 5.30–19.00), sleeping problem (OR = 3.50, 95% CI = 2.10–5.90), stress (OR = 5.70, 95% CI = 3.50–9.50), GHQ-12 (OR = 3.90, 95% CI = 2.70–5.70), suicidal thought (OR = 7.30, 95% CI = 4.60–11.00), suicide attempt (OR = 5.30, 95% CI = 2.30–12.00) Physical abuse (men): poor general health (OR = 2.20, 95% CI = 1.20–4.10), anxiety (OR = 7.1, 95% CI = 3.0–16.0), stress (OR = 5.90, 95% CI = 3.10–11.00), GHQ-12 (OR = 3.20, 95% CI = 1.90–5.50), suicidal thought (OR = 4.70, 95% CI = 2.40–9.00), suicide attempt (OR = 5.40, 95% CI = 1.80–16.00) |

| Begle, 201150 | CS | 902 adults aged ≥60 using stratified random digit dialing, computer-assisted telephone interview | ≥60; 59.9% female | Emotional, sexual, physical abuse | Negative emotional symptoms (anxious, depressed, irritable) | Sociodemographic, health status, social support, social services, physical function | Emotional abuse (OR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.04–4.36), physical abuse (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.22–2.03) |

| Cisler, 201098 | CS | 902 adults aged ≥60 in South Carolina | ≥60; 60% female | EA | Self-rated physical health | Income, needing help with ADLs, emotional symptoms | Prior exposure to potentially traumatic events (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.18–3.03) |

| Fisher, 200699 | CS | 842 community-living women who completed telephone survey | ≥60; 100% female | EA | Health status, medical conditions, psychological distress, digestive problems | Age, sex, race, education, marital status, income, Appalachian heritage | Greater depression or anxiety (OR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.70–2.96), greater digestive problems (OR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.22–2.09), greater chronic pain (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.28–2.15) |

| Smith, 2006100 | CS | 80 APS referrals along with matched control subjects from clinical population | Mean 76; 62.5% female | SN | Complete blood count and chemistry, oxidative damage and antioxidants, fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B-12 and folate, calcium and bone metabolism | N/A | Serum concentration of total homocysteine 13.6 ± 4.5, μmol/L, P < .05; red blood cell folate concentration 1,380 ± 514 nmol/L, P < .05; plasma b-carotene 0.28 ± 0.2 μmol/L, P < .05; X-tocopherol 23.2 ± 9.3 μmol/L, P < .05; 25-hydroxyvitamin-D serum concentration 33.7 ± 16.4 nmol/L, P < .05 |

| Franzini, 2008101 | CC | 131 APS clients and 131 matched controls to an interdisciplinary geriatric medicine clinic | ≥65; 69.5% female | SN | Health utilization, clinic visits, house calls, hospital stays, length of stay healthcare costs | Age, sex, race, mental disorders | Total cost: $12,466 for SN vs $19,510 for control (P = .36) Physician costs, PE −0.29 (0.40); outpatient payments, PE −0.24 (0.45); inpatient costs, PE −0.20 (0.28); total Medicare costs, PE —0.36 (0.33); clinic visits, PE −0.24 (0.10); hospital stays, PE −0.51 (0.05) |

| Mouton, 1999102 | CS | 257 women aged 50 | 50–79; 100% female | Psych Abuse | Mental health | Age, race, marital status, family income, and education | Being threatened (PE −3.32, P = .01) |

Parameter estimate (PE) is a coefficient of change in the outcome for every unit increase in the predictor variable of interest.

PS = prospective; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; CHAP = Chicago Health Aging Project; SN = self-neglect; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale; RR = risk ratio; SE = standard error; WHI = Women’s Health Initiative; BMI = body mass index; MCS = Mental Component Summary; EPESE = Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly; GHQ-12 = General Health Questionnaire; APS = Adult Protective Services.

DISCUSSION

Elder abuse is prevalent in older adults across five continents, especially minority older adults. Because different research methodologies are used in the literature, a variety of risk factors have been found to be associated with elder abuse. Among the risk factors, cognitive and physical impairment and psychosocial distress seem to be consistently associated with elder abuse. Elder abuse may lead to deleterious health outcomes and increase healthcare use.

There are various limitations in the field of elder abuse that add to the challenges of synthesizing data in this systematic review. One particular limitation is that no consistent elder abuse instrument has been used to measure elder abuse, making it difficult to compare the prevalence and understand the risk factors between studies. Despite using the same instrument, the cutoff for definite elder abuse varies greatly across studies. Many studies have used an “any positive item” approach, whereas others have more systematically considered the heterogeneity of the definitions and have been stricter in the categorization of elder abuse cases. In addition, some studies have used an extensive version of the screening instrument, whereas others chose a shorter version that may contain only one question. Recently, to address the question of inconsistencies in elder abuse instruments, operational definitions of different strictness have been used to examine elder abuse in the same population cohort, and the prevalence of elder abuse and its subtypes varied greatly in the same population through using different measurements.33 The present study provided important empirical evidence of the effect of different instruments on the prevalence, but future studies should expand efforts to develop a more-consistent instrument and cutoff score. Another limitation is that most of the existing studies do not provide reliability and validity information for the instrument. Lack of consistency and precision in the assessment of elder abuse may prevent clear understanding of the accurate prevalence and risk and protective factors and impede the development of prevention and intervention programs.

In addition, the number and quality of studies varied greatly according to region and cultural group. The majority of studies of elder abuse were conducted in North America, Europe, and Asia, with only two studies identified in Africa. Almost all studies in North America were conducted in the United States. A lack of representative studies in certain regions, including Africa, Canada, Australia, and South America, has impeded the comparison and understanding of prevalence of elder abuse across continents, and the number of studies in U.S. minority populations such as Asian American and Hispanic older adults is not enough to perform a rigorous analysis of the differences in elder abuse between cultural groups.

In terms of the analysis of risk factors of elder abuse, existing studies have primarily focused on victim characteristics, but perpetrator characteristics such as caregiver burden, mental health, substance abuse, and premorbid relationship may also affect the occurrence of elder abuse. Moreover, the majority of studies of risk factors of elder abuse have used a cross-sectional design, which further hampers the ability to determine the causal relationship between vulnerability risk factors and elder abuse.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Longitudinal Studies on Elder Abuse

Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the incidence of elder abuse subtypes in diverse settings and the associated risk and protective factors. Longitudinal research may also help to understand potential perpetrators’ characteristics, relationships, settings, and contexts with respect to elder abuse victims. The fields of child abuse and domestic violence have demonstrated the feasibility of conducting research on potential perpetrators. Innovative approaches for understanding perpetrators’ perspectives are necessary for the design and implementation of future interventions. Moreover, research is needed to understand pathway by which elder abuse leads to adverse outcomes, especially the risk, rate, and intensity of health services use with respect to elder abuse. Given the complexity of elder abuse research in older adults with lower cognitive function, more-rigorous studies are needed to improve understanding of the issue. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses are also needed to examine the costs associated with elder abuse and utilities of existing intervention programs. Because many cost–benefit analyses are biased against older adults, innovative strategies are needed to capture the range of personal, community, financial, and societal costs of elder abuse.

Elder Abuse in Minority Populations

The prevalence of elder abuse in ethnic minority groups was found to be higher than in whites.14–16 With the increasingly diverse aging population, national priorities to better understand the cultural factors related to elder abuse in racial and ethnic populations should be set.62 The last decade has seen a population growth rate of 5.7% for whites, 43.0% for Hispanics, 43.3% for Asians, 18.3% for Native Americans, and 12.3% for African Americans.63 Quantitative and qualitative studies are needed to better define the conceptual and cultural variations in the constructions and definitions of elder abuse subtypes. Significant challenges exist in conducting aging research in minority communities, especially regarding culturally sensitive matters.64 Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches could be frameworks for addressing elder abuse.65 CBPR necessitates equal partnership between academic and community organizations and stakeholders to examine relevant issues. This partnership requires reciprocal transfer of expertise and sustainable infrastructure building. Recent elder abuse research (Population Study of Chinese Elderly) in the Chicago Chinese community has demonstrated enhanced infrastructure and networks for community-engaged research and community–academic partnerships.66

Prevention and Intervention Studies on Elder Abuse

Although elder abuse is common and universal, few evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies have been developed to assist victims of elder abuse.67 Common forms of intervention programs may include advocacy service intervention, support groups, care coordination, and public education. Interventions on elder abuse could employ CBPR and multidisciplinary team (M-Team) approaches.

Through implementing the CBPR approach, elder abuse intervention programs could build on strengths and resources in the community. Using the CBPR approach, the Family Care Conference (FCC) was developed in a northwestern Native American community. The pilot study demonstrated that the FCC approach helped to bring family members’ attention to the problem of elder abuse and to incorporate their efforts into intervention.68 In a qualitative study of the perception of effectiveness, challenges, and cultural adaptations of elder abuse interventions, older adults participating in the study appraised the community-based intervention module and have positive attitudes toward interventions that community-based social services organizations delivered.69 Future research efforts should promote and sustain the collaboration between community organizations and research institutions to better address the needs and concerns of older adults. At the same time, more evidence-based studies should be conducted to examine the efficacy and sustainability of intervention programs in diverse settings.

M-Teams exist in the field of elder abuse, despite a dearth of data regarding the efficacy, sustainability, and cost effectiveness of the M-team approach. An M-Team usually comprises a healthcare provider, a social worker, social services, a legal professional, an ethicist, a mental health specialist, community leaders, and residents. Although many state aging departments such as the Illinois Department on Aging recommended M-teams, systematic studies are needed, as well as rigorously designed intervention studies with relevant outcome measures. Given the different types of elder abuse and variation in risk and protective factors and perpetrator characteristics, intervention and prevention studies should begin to focus on specific high-risk dyads. Prevention and intervention studies must also consider cost effectiveness and scalability at the broad levels.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Health professionals are well situated to screen for elder abuse and detect vulnerabilities.70,71 How older adults manage their daily lives can suggest predisposing factors that may impair their ability to live independently and protect themselves. Assessing functional, cognitive, and psychosocial well-being is important for understanding the predisposing and precipitating risk factors associated with elder abuse. A recent validation study of the elder abuse vulnerability index suggests that older adults with three or four vulnerability factors have almost 4 times the risk of elder abuse, whereas those with five or more factors have more than 26 times the risk.72

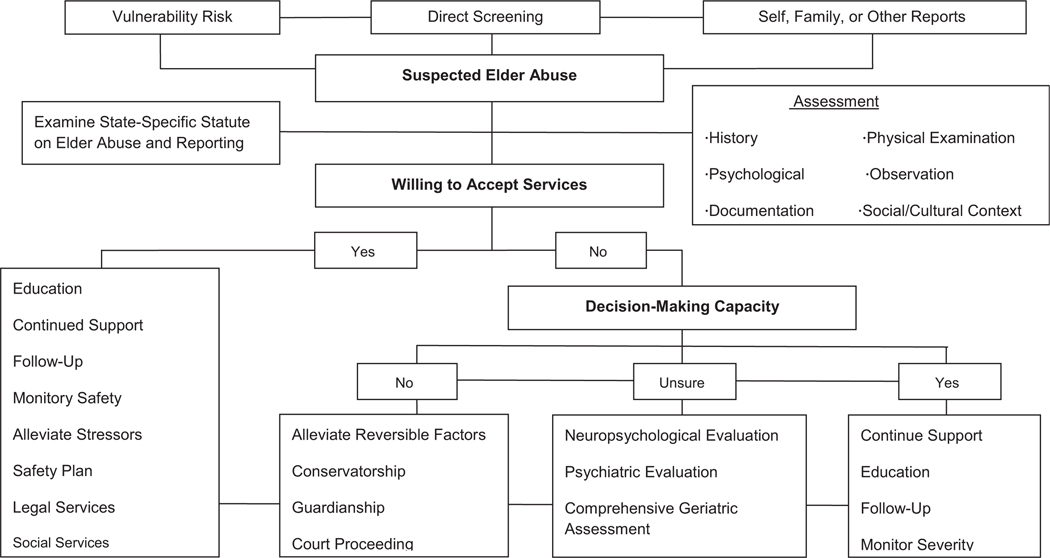

Because elder abuse victims often interact with health systems, increased screening and treatment should be instituted in healthcare settings. Primary care outpatient practices, inpatient hospitalization episodes, and discharge planning and home health could play pivotal roles in identifying potentially unsafe situations that could jeopardize the safety and well-being of older adults.73 Early detection and interventions, such as incorporating effective treatment of underlying problems, providing community-based services, and appropriately involving family, may help delay or prevent elder abuse (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Healthcare professional management strategies for elder abuse. APS = Adult Protective Services.

When health professionals suspect elder abuse, detailed histories should be gathered, especially psychosocial and cultural aspects. In addition, specific findings from physical examinations that may further indicate elder abuse should be documented. Moreover, health professionals should document observations of patient behavior, reactions to questions, and family dynamics and conflicts. Whenever indicated, health professionals should order laboratory tests and imaging tests. These types of documentation are critical for supporting the interdisciplinary team and APS to ameliorate elder abuse and protect vulnerable older adults. Furthermore, health professionals should devise patient-centered plans to provide support, education, and follow-up and should monitor ongoing abuse and institute safety plans.

Almost all states have mandatory reporting legislation requiring health professionals to report reasonable suspicions of elder abuse. Elder abuse reports can come from variety of sources and could be anonymous if within the authorization of the statute, but in most states, reporting of elder abuse by health professionals is not anonymous, because follow-up may be needed with the reporter to provide further evidence and assessment. When health professionals suspect elder abuse, they should contact the state office on aging, the ElderCare Locator (800–677–1116), or the National Center on Elder Abuse.

Health professionals may be reluctant to report elder abuse because of subtlety of signs, victim denial, and lack of knowledge about reporting procedures.71 Other reasons for reluctance include concern about losing physician–patient rapport, concern over potential retaliation by perpetrators, time limitation, doubt regarding the effect of APS, and perceived contradictions between mandatory reporting and a provider’s ability to act in the patient’s best interests.74 A common misconception for reporting elder abuse is that convincing evidence is needed to report. In addition, given the fear of liability, the physician may ask for proof rather than suspicion of abuse to report elder abuse.74 On the contrary, elder abuse should be reported to APS whenever a reasonable suspicion arises.

Health professionals promote a patient’s rights to autonomy and self-determination, maintain a family unit whenever possible, and provide recommendations for the least-restrictive services and safety plan. It must be presumed that an older adult has decision-making capacity (DMC) and accept the person’s choices until a healthcare provider or the legal system determines that the person lacks capacity. One of the most difficult dilemmas is under what types of situations the medical community and society at large have a responsibility to override personal wishes. The presence or absence of capacity is often a determining factor in what health professionals, the community and society need to do next,75 but capacity is not present or absent; rather it is a gradient relationship between the problems in question and an older adult’s ability to make these decisions. Complex health problems require higher levels of DMC. For simpler problems, even a cognitively impaired adult could have DMC, but health providers are often forced to make gray areas black and white for purposes of guiding next steps such as guardianship or conservatorship. Commonly used brief screening tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination are inadequate for determining capacity except at the extremes of the score. A more-useful test for assessing DMC is the Hopkins Competency Assessment Test.76

IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL SERVICE PROVIDERS

Community Organizations

Community organizations play a critical role in reducing the risk of elder abuse in community-dwelling older adults. Education should be provided to increase awareness of elder abuse in the community. In particular, given the cultural and linguistic barriers facing minority older adults, community organizations should improve minority older adults’ access to culturally sensitive services related to elder abuse. Meanwhile, community organizations should sustain and promote collaboration with academic organizations to explore and tackle elder abuse.

Adult Protective Services

APS programs, typically run by local or state health departments, provide protection for adults against abuse and investigate and substantiate reports. After a report of elder abuse, an assigned APS worker would make an in-person home visit to investigate the nature and severity of the abuse. From a comprehensive list of indicators and input from older adults, family members, and other involved parties, elder abuse is substantiated, partially substantiated, or not substantiated, but even if it is not substantiated, it does not necessarily mean there was no elder abuse because there are often barriers to assessing older adults and obtaining the information needed to substantiate a case.

As the aging population continues to grow, investigations by APS have become increasingly complex.77 A recent systematic review of elder abuse and dementia suggested that insufficient financial resources, insufficient access to information needed to resolve elder abuse cases, inadequate administrative systems, and lack of cross-training with other disciplines in the aging field serving clients with mental health disabilities may hinder the role of APS workers in ameliorating abusive situations.77 The M-Team could help confirm abuse, document impaired capacity, review medications and medical conditions, facilitate the conservatorship process, persuade the client or family to take action, and support the need for law enforcement involvement.78

HEALTH POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Two important federal laws address elder abuse: the Older Americans Act (OAA) and the Elder Justice Act (EJA). The OAA authorizes funding for National Ombudsman Resource Center, National Center on Elder Abuse, Office of State Long Term Care Ombudsman, legal and justice services for victims, funding of demonstration projects, outreach activities, and State Legal Assistance Developer to enhance coordinated care. The EJA was passed in the 110th Congress to unify federal systems and respond to elder abuse. It required the Secretary of Health and Human Services to promulgate guidelines for human subject protections to assist researchers and establish elder abuse forensic centers across the United States. The EJA authorized funding and incentives for long-term care staffing; builds electronic medical records technology; collects and disseminates annual APS data; and sponsors and supports training, services, reporting, and the evaluation program for elder justice, although the majority of programs and activities under the EJA have not received funding, and the EJA is in danger of being dissolved. The authorization of appropriations for EJA provisions expired on September 30, 2014, and the likelihood of continuing Congressional resolution and reauthorization is uncertain.79 The EJA plays an important role in elder abuse research and prevention. The Government Accountability Office described the EJA as providing “a vehicle for setting national priorities and establishing a comprehensive multidisciplinary elder justice system in this country.”9 Comprehensive, systematic, coordinated, multilevel advocacy and policy efforts are needed to address elder abuse in legislation at the national level.80

CONCLUSION

This review highlights the epidemiology of elder abuse and the complexities of research and practice. National longitudinal research is needed to better define the incidence, risk and protective factors, and consequences of elder abuse in diverse racial and ethnic populations. Health professionals should consider integrating routine screening of elder abuse in clinical practice, especially in high-risk populations. Patient-centered and culturally appropriate treatment and prevention strategies should be instituted to protect vulnerable populations. Although vast gaps remain in the field of elder abuse, unified and coordinated efforts at the national level must continue to preserve and protect the human rights of vulnerable aging populations.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Flowchart Describing Review Process for Identification of Eligible Studies.

Figure S2. Range of Prevalence Across Five Continents.

Table S1. Prevalence Estimates of Elder Abuse by Population, Survey Methods and Definitions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the APS staff and other front-line aging professionals around the globe for their continued dedication and commitment to protecting vulnerable victims of elder abuse in diverse populations.

Dr. Dong was supported by National Institute on Aging Grants R01 AG042318, R01 MD006173, R01 NR 14846, R01 CA163830, R34MH100443, R34MH100393, and RC4 AG039085; a Paul B. Beeson Award in Aging; the Starr Foundation; the American Federation for Aging Research; the John A. Hartford Foundation; and the Atlantic Philanthropies.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Dong declares no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Confronting Chronic Neglect. The Education and Training of Health Professionals on Family Violence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center on Elder Abuse. Types of Abuse, 2014. [on-line]. Available at http://ncea.aoa.gov/FAQ/Type_Abuse/ Accessed March 15, 2014.

- 3.Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health 2010;100:292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach SR, Schulz R, Castle NG et al. Financial exploitation and psychological mistreatment among older adults: Differences between African Americans and non-African Americans in a population-based survey. Gerontologist 2010;50:744–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong X, Simon M, de Leon CM et al. Elder self-neglect and abuse and mortality risk in a community-dwelling population. JAMA 2009;302:517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien JG. A physician’s perspective: Elder abuse and neglect over 25 years. J Elder Abuse Negl 2010;22:94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burston GR. Granny battering. BMJ 1975;iii:592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Research Council. Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation in an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government Accountability Office. Elder Justice: Stronger Federal Leadership Could Enhance National Response To Elder Abuse [on-line]. Available at http://agingsenategov/events/hr230kb2pdf2011 Accessed March 10, 2014.

- 10.Stoltzfus E. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA): Background, Programs, and Funding. Congressional Research Service 2009;7–5700.

- 11.White House. Presidential Proclaimation: World Elder Abuse Awareness Day [on-line]. Available at http://wwwwhitehousegov/the-press-office/2012/06/14/presidential-proclamation-world-elder-abuse-awareness-day-2012 Accessed March 15, 2014.

- 12.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Elder Mistreatment Quality Measurement Initiative, 2013. [on-line]. Available at http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Global/ViolenceForum/2013-APR-17/Presentations/02–07-McMullen.pdf Accessed March 27, 2014.

- 13.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Third Annual Report to Congress on High-Priority Evidence Gaps for Clinical Preventive Services, 2013. [on-line]. Available at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/third-annual-report-to-congress-on-high-priority-evidence-gaps-for-clinical-preventive-services. Accessed March 18, 2014. [PubMed]

- 14.DeLiema M, Gassoumis ZD, Homeier DC et al. Determining prevalence and correlates of elder abuse using promotores: Low-income immigrant Latinos report high rates of abuse and neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1333–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong X, Chen R, Simon MA. Prevalence and correlates of elder mistreatment in a community-dwelling population of U.S. Chinese older adults. J Aging Health 2014;26:1209–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong X, Simon MA, Evans DA. Prevalence of self-neglect across gender, race, and socioeconomic status: Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Gerontology 2011;58:258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ et al. Mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2008;63B:S248–S254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachs M, Berman J. Under the radar: New York State elder abuse prevalence study. Prepared by Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, and New York City Department for the Aging, 2011. [on-line]. Available at http://www.preventelderabuse.org/library/documents/UndertheRadar051211.pdf Accessed April 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindert J, de Luna J, Torres-Gonzales F et al. Abuse and neglect of older persons in seven cities in seven countries in Europe: A cross-sectional community study. Int J Public Health 2013;58:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadmus EO, Owoaje ET. Prevalence and correlates of elder abuse among older women in rural and urban communities in south western Nigeria. Health Care Women Int 2012;33:973–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu L, Chen H, Hu Y et al. Prevalence and associated factors of elder mistreatment in a rural community in People’s Republic of China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e33857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh J, Kim HS, Martins D et al. A study of elder abuse in Korea. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43:203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiglesworth A, Mosqueda L, Mulnard R et al. Screening for abuse and neglect of people with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naughton C, Drennan J, Lyons I et al. Elder abuse and neglect in Ireland: Results from a national prevalence survey. Age Ageing 2012;41:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajdukovic M, Ogresta J, Rusac S. Family violence and health among elderly in Croatia. J Aggression Maltreatment Trauma 2009;18:261–279. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chokkanathan S. Factors associated with elder mistreatment in rural Tamil Nadu, India: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;29:863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowenstein A, Eisikovits Z, Band-Winterstein T et al. Is elder abuse and neglect a social phenomenon? Data from the First National Prevalence Survey in Israel. J Elder Abuse Negl 2009;21:253–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel Rahman TT, El Gaafary MM. Elder mistreatment in a rural area in Egypt . Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012;12:532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong X, Simon MA, Gorbien M. Elder abuse and neglect in an urban Chinese population. J Elder Abuse Negl 2007;19:79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (ct) Scales . J Marriage Fam 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan E. Tang CS-K. Prevalence and psychological impact of Chinese elder abuse. J Interpers Violence 2001;16:1158–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comijs HC, Pot AM, Smit JH et al. Elder abuse in the community: Prevalence and consequences. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong X. Do the definitions of elder mistreatment subtypes matter? Findings from the PINE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69(Suppl 2):S68–S75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong XQ, Simon M, Evans D. Cross-sectional study of the characteristics of reported elder self-neglect in a community-dwelling population: Findings from a population-based cohort. Gerontology 2010;56:325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abrams RC, Lachs M, McAvay G et al. Predictors of self-neglect in community-dwelling elders. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1724–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan E, Chan KL. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among older Chinese couples in Hong Kong . Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1437–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beach SR, Schulz R, Williamson GM et al. Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong X, Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF et al. Self-neglect and cognitive function among community-dwelling older persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong X, Simon MA, Wilson RS et al. Decline in cognitive function and risk of elder self neglect: Finding from the Chicago Health Aging Project. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:2292–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong X, Simon M, Rajan K et al. Association of cognitive function and risk for elder abuse in a community-dwelling population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2011;32:209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman LS, Avila S, Tanouye K et al. A case control study of severe physical abuse of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lachs MS, Williams C, O’Brien S et al. Risk factors for reported elder abuse and neglect: A nine-year observational cohort study. Gerontologist 1997;37:469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tierney MC, Snow WG, Charles J et al. Neuropsychological predictors of self-neglect in cognitively impaired older people who live alone. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong X, Simon MA, Gorbien M et al. Loneliness in older Chinese adults: A risk factor for elder mistreatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1831–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong X, Chang E-S, Wong E et al. Association of depressive symptomatology and elder mistreatment in a US Chinese population: Findings from a community-based participatory research study. J Aggression Maltreatment Trauma 2014;23:81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shugarman LR, Fries BE, Wolf RS et al. Identifying older people at risk of abuse during routine screening practices. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strasser SM, Smith M, Weaver S et al. Screening for elder mistreatment among older adults seeking legal assistance services. West J Emerg Med 2013;14:309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.VandeWeerd C, Paveza GJ, Walsh M et al. Physical mistreatment in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Aging Res 2013;2013:920324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi NG, Kim J, Asseff J. Self-neglect and neglect of vulnerable older adults: Reexamination of etiology. J Gerontol Soc Work 2009;52:171–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Begle AM, Strachan M, Cisler JM et al. Elder mistreatment and emotional symptoms among older adults in a largely rural population: The South Carolina Elder Mistreatment Study. J Interpers Violence 2011;26:2321–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]