Abstract

SM22α is a 22-kDa smooth muscle cell (SMC) lineage-restricted protein that physically associates with cytoskeletal actin filament bundles in contractile SMCs. To examine the function of SM22α, gene targeting was used to generate SM22α-deficient (SM22−/−LacZ) mice. The gene targeting strategy employed resulted in insertion of the bacterial lacZ reporter gene at the SM22α initiation codon, permitting precise analysis of the temporal and spatial pattern of SM22α transcriptional activation in the developing mouse. Northern and Western blot analyses confirmed that the gene targeting strategy resulted in a null mutation. Histological analysis of SM22+/−LacZ embryos revealed detectable β-galactosidase activity in the unturned embryonic day 8.0 embryo in the layer of cells surrounding the paired dorsal aortae concomitant with its expression in the primitive heart tube, cephalic mesenchyme, and yolk sac vasculature. Subsequently, during postnatal development, β-galactosidase activity was observed exclusively in arterial, venous, and visceral SMCs. SM22α-deficient mice are viable and fertile. Their blood pressure and heart rate do not differ significantly from their control SM22α+/− and SM22α+/+ littermates. The vasculature and SMC-containing tissues of SM22α-deficient mice develop normally and appear to be histologically and ultrastructurally similar to those of their control littermates. Taken together, these data demonstrate that SM22α is not required for basal homeostatic functions mediated by vascular and visceral SMCs in the developing mouse. These data also suggest that signaling pathways that regulate SMC specification and differentiation from local mesenchyme are activated earlier in the angiogenic program than previously recognized.

Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) subserve a variety of functions in higher vertebrates, including the regulation of arterial tone, the control of airway resistance, and the modulation of gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract contractility and basal tone. Despite the myriad of functions mediated by SMCs, relatively little is understood about the developmental programs that regulate SMC specification and differentiation. This is due, in part, to the complex embryological origins of the SMC lineage(s) and the lack of definitive SMC markers (27, 28). In contrast to striated muscle cells which terminally differentiate, SMCs retain their capacity to proliferate and modulate their phenotype during postnatal development (27, 34, 36, 37). This characteristic presumably evolved to facilitate reparative processes such as wound healing. However, it has also been implicated in the pathophysiology of a number of disease processes, including hypertension, restenosis following angioplasty, posttransplant arteriopathy, and asthma (13, 25, 32, 34).

Cytoskeletal dynamics and organization play an important role in regulating SMC morphology and phenotype (for a review, see reference 41). The SMC cytoskeleton is composed of actin filaments, as well as intermediate filaments and their associated proteins. The insoluble network of intermediate filaments has been implicated in the maintenance of SMC shape (42). The intermediate filaments colocalize with a subpopulation of F-actin filament bundles that is distinct from the contractile apparatus (26). The cytoskeletal actin filaments and smooth muscle actin converge upon α-actinin-containing dense bodies that serve as a possible coupling point between the SMC contractile apparatus and the cytoskeleton (26). Cytoskeletal actin filaments are anchored within focal adhesions which form rib-like arrays over the entire SMC surface (40). The geometric organization of these arrays assures that contractile tension is distributed uniformly over the SMCs to the extracellular matrix.

SM22α is a 22-kDa cytoskeletal protein that is expressed abundantly and exclusively in visceral and vascular SMCs during postnatal development. SM22α has been variably designated SM22α (17, 37), transgelin (16), WS3-10 (45), and p27 (1). SM22α mRNA has been detected in the dorsal aorta of the mouse embryo as early as embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) (18). Like most other markers of the SMC lineage, SM22α is also expressed in embryonic cardiac and skeletal muscle through mid-gestation (6, 17, 18, 37). SM22α is downregulated in concert with other SMC-restricted myofibrillar proteins in late-passage primary aortic SMCs and in neointimal SMCs that arise in response to arterial injury (35, 36). In human atherosclerotic lesions, SM22α is downregulated within neointimal SMCs but is expressed in SMCs that form the fibrous caps of complicated atherosclerotic lesions (35, 36). Our group, and others, reported that the mouse SM22α promoter restricts transgene expression to arterial SMCs, suggesting that distinct transcriptional programs may distinguish previously unrecognized SMC sublineages (14, 19, 22, 43). The activity of the mouse SM22α promoter is critically dependent upon two CArG box-containing elements that bind the MADS box transcription factor SRF (14, 19, 22, 43).

Despite the fact that SM22α is expressed abundantly in SMCs and has been localized within the cytoskeletal apparatus, relatively little is understood about its function. SM22α shares high-level amino acid sequence identity with several other proteins, including the thin filament SMC-restricted myofibrillar regulatory protein calponin (33, 44), the Caenorhabditis elegans body wall muscle protein Unc-87 (8), the Drosophila muscle protein Mp20 (2), and the neuronal-restricted protein NP25 (31). Mutation of the unc-87 and mp20 genes results in paralysis of the C. elegans body wall and of the Drosophila flight muscle, respectively (2, 8). SM22α colocalizes to actin filament bundles and stress fibers (41). Purified SM22α protein binds directly to actin filaments at a ratio of 1:6 actin monomers (38, 39). These data suggest that SM22α may serve to organize the spatial relationships of actin filaments in SMCs (38, 39, 41). In this regard, it is also noteworthy that SM22α gene expression is downregulated when vascular SMCs assume a synthetic phenotype and by cellular transformation processes that involve major cytoskeletal rearrangements (35, 37). Taken together, these data suggest that SM22α may play a role in organization of the cytoskeleton and directly, or indirectly, regulate SMC morphology or other processes involving the cytoskeleton.

In the studies described here, gene targeting was used to define precisely the spatial and temporal patterns of SM22α transcriptional activation during vascular development and to examine the function of the SM22α protein in SMCs. Surprisingly, in E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryos β-galactosidase activity was observed in the dorsal aorta. This is 24 to 36 h prior to the documented expression of genes encoding vascular SMC markers in the embryonic mouse. During postnatal development, SM22α gene was activated exclusively in visceral and vascular SMCs. SM22α-deficient embryos (SM22−/−) are viable and fertile and develop normally. SMC-containing tissues from SM22α-deficient mice are histologically indistinguishable from the tissues of their control littermates, and only subtle defects in the arrangement of actin filaments are observed in SM22α-deficient SMCs. These data demonstrate that SM22α is not required for the normal development of the mouse embryo and basal homeostatic functions mediated by SMCs. In addition, these data demonstrate that the devleopmental program leading to vascular stabilization and patterning during embryonic development is initiated earlier than was suggested by previous studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular cloning and generation of SM22α mutant embryonic stem (ES) cells and mice.

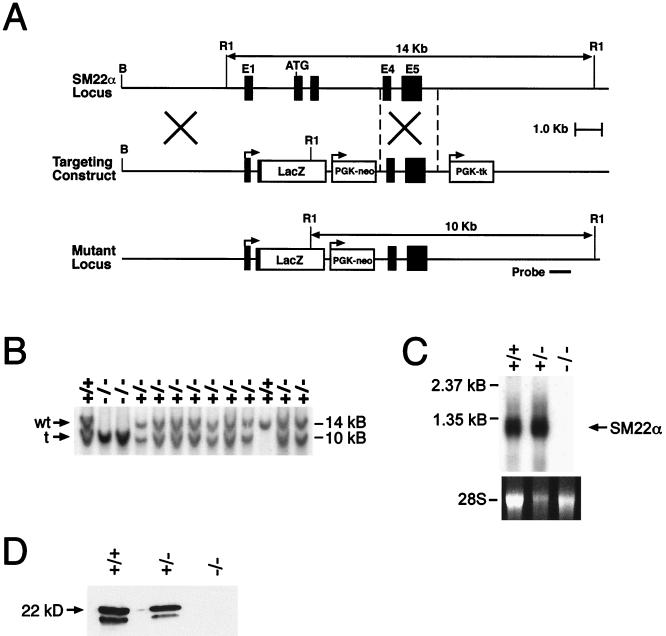

A genomic clone including the 5′ end of the murine SM22α gene was isolated from an SV129 mouse library (43). The targeting vector was generated in the pPNT plasmid (46), which contains the PGK-neo-poly(A) and PGK-tk-poly(A) cassettes for positive and negative selection, respectively. As schematically represented in Fig. 1A, the pPNTSM22.LacZ targeting vector contains a genomic subfragment that includes approximately 5-kb of the SM22α 5′ flanking sequence, exon 1, intron 1, and exon 2 sequence through the initiation codon (denoted as ATG). This was cloned in frame to the bacterial lacZ reporter gene (denoted as LacZ), which in turn was subcloned into NotI/XhoI-digested pPNT. The targeting vector also includes the 2.6-kb BamHI/NcoI SM22α genomic subfragment that spans exon 4 through intron 5 sequences subcloned into the EcoRI site of pPNT. In pPNTSM22.LacZ, sequences 3′ of the initiation codon of exon 2 are replaced by the lacZ reporter gene and the PGK-neo cassette.

FIG. 1.

Targeted disruption and insertion of lacZ gene into the SM22α gene. (A) Schematic representation of the SM22α targeting strategy. (Top) Partial restriction endonuclease map of the murine SM22α genomic locus showing BamHI (B) and EcoRI (R1) sites. Exons are shown in black. (Middle) SM22α targeting vector containing the neomycin resistance (neo) and herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (tk) genes under the control of the PGK promoter. (Bottom) Structure of the targeted mutant SM22α allele and location of the probe used in Southern blot analyses. (B) Southern blot analysis of DNA prepared from the offspring of SM22+/−LacZ × SM22+/−LacZ mating. DNA was digested with EcoRI and hybridized to the radiolabeled SM22α genomic probe shown in Fig. 1A. The positions of the wild-type (14-kb) and targeted (10-kb) allele are indicated with arrows at left. (C) (Top) Northern blot analysis of SM22α gene expression in aortic RNA harvested from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous-null (−/−) mice. (Bottom) Loading and integrity of RNA was assessed by ethidium bromide staining of the 28S RNA in the gel prior to membrane transfer. (D) Western blot analysis of protein lysates prepared from the aorta of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous-null (−/−) mice. Protein was fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to Immobilon-P membrane, incubated with rabbit α-mouse SM22α polyclonal antiserum, and visualized with goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody. The 22-kDa marker is shown to the right.

The SM22α targeting construct was linearized with NotI and electroporated into RW ES cells as described previously (24). After 24 h, neomycin-resistant transfectants were selected in 250 μg of G418 per ml and 1 μM gancyclovir for 8 to 10 days. DNA from resistant ES cell clones was analyzed by Southern blot analysis after EcoRI digestion with a radiolabeled probe derived from genomic sequences located 3′ of the targeting vector (see Fig. 1A). To generate SM22α-deficient mice, ES cells from two independently derived SM22+/−LacZ clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 donor blastocysts that were implanted into pseudopregnant CD1 females (3, 12). The resulting male chimeras were mated with C57BL/6 females, and agouti offspring were genotyped by Southern blot analysis as described previously (24). SM22+/−LacZ mice were then outbred with C57BL/6 and CD1 mice to generate heterozygous SM22−/−LacZ mice that were interbred for phenotype analysis. All animal experimentation was performed according to National Institutes of Health guidelines in the University of Pennsylvania Animal Care Facility.

Preparation of SM22α polyclonal antiserum.

The pGEX4TSM22α expression plasmid encoding the glutathione S-transferase (GST)–mouse SM22α (amino acids 1 to 201) fusion protein was transformed into bacteria, and GST-SM22α fusion protein was induced and purified from bacterial extracts as described previously (23). Rabbits were immunized with the purified GST-SM22α fusion protein according to the standard protocol of Cocalico Biologicals, Inc. (Reamstown, Pa.). Preimmune immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-SM22α polyclonal IgG (no. 1387-4) were isolated from the serum by GST-SM22α affinity chromatography and protein A-Sepharose chromatography.

Northern and Western blot analyses.

RNA was isolated from tissues of wild-type, heterozygous SM22+/−LacZ, and homozygous SM22−/−LacZ mice as described elsewhere (24). Northern blot analyses were performed using 10 μg of RNA/sample, and the radiolabeled 754-bp (bp 29 to 811) mouse SM22α cDNA probe as described previously (29). Western blot analyses were performed as described earlier using the affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal α-SM22α antiserum and control rabbit preimmune IgG (17).

Cardiovascular physiological assessment.

The systolic blood pressure (SBP) and heart rate (HR) of conscious wild-type, heterozygous (SM22+/−LacZ), and homozygous-null (SM22−/−LacZ) adult male mice were compared using a mouse physiological recording system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Visitech System, Apex, N.C.). Each measurement was performed in triplicate and was repeated the following day to ensure reproducibility. To assess cardiac function in wild-type, heterozygous (SM22+/−LacZ), and homozygous-null (SM22−/−LacZ) adult male mice, echocardiography was performed using an S12 transducer (5 to 12 MHz) and a HP5500 Sonos system as described earlier (7). M-mode tracings were made at the level of the papillary muscle in the left ventricular (LV) short-axis view. The heart rate was determined from the M-mode and pulsed-Doppler tracings of the peak aortic flow velocity in the ascending aorta. On-line measurement of LV dimensions was made using a Tom Tec Imaging System. End-systolic and diastolic dimensions were determined by plainimetry. The percent left ventricular fractional shortening was calculated using a standard formula: [(LVEDd − LVESd)/LVEDd] × 100. The percent ejection fraction was estimated from the fractional area change (FAC) in the LV short-axis view as follows: FAC = [(LVEDa − LVESa)/LVEDa] × 100. Color flow mapping and pulsed Doppler wave forms were obtained across the pulmonary artery to evaluate patent ductus arteriosus. The statistical significance was calculated by analysis of variance ANOVA and by two-tailed unpaired Student t test (a P value of <0.05 was considered significant).

Cell biology, histology, and ultrastructural analyses.

Tissues from adult wild-type and SM22−/−LacZ mice were fixed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (24). Embryos and tissue sections from adult mice were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (5). A7r5 SMCs were stably transfected with an expression plasmid encoding Ds-RED epitope-tagged mouse SM22α as described previously (15). Three-dimensional (3-D) fluorescence images of A7r5 cells and primary SMCs were acquired using a Delta Vision microscopy system (Applied Precision, Issaquah, Wash.) equipped with an appropriate barrier filter set (Chroma, Battleboro, Vt.) for Ds-Red or rhodamine (λex = 555 nm, λem = 617 nm). Spatial and temporal normalization of the illumination intensity allowed quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity (11). A constrained iterative deconvolution algorithm (11) using an experimentally measured point spread function was applied to 3-D arrays of optical sections to yield a high-resolution spatial distribution of fluorescence intensity that accurately represented the 3-D cytoskeletal structure (9). Image restoration and volume projections were computed using SoftWoRx software (Applied Precision). For electron microscopy, the aorta and bladder from wild-type and SM22−/−LacZ mice were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde and then postfixed with 2% aqueous osmium tetroxide as described previously (4). The samples were washed and dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in LX-112 medium that was polymerized at 70°C for 48 h. Ultrathin sections (80 nm) were cut with a diamond knife and stained with uranyl acetate. Immunogold labeling of tissue sections was performed as described previously (4). Samples were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.05% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h, treated with 10 mM NH4Cl for 30 min, dehydrated at −20°C, and embedded in Lowicryl K4M medium. The samples were polymerized with UV light (365 nm), and ultrathin sections (90 nm) were cut, mounted on Formvar-coated nickel grids, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin and 2% goat serum, and incubated with affinity-purified anti-SM22α polyclonal antiserum or control rabbit IgG at a 1:100 dilution. The sections were then incubated with 15-nm gold-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and stained with uranyl acetate, and the images were visualized with a Philips CM100 electron microscope at 60 kV.

RESULTS

Targeted disruption of the SM22α gene and insertion of lacZ in ES cells and mice.

To produce a targeted disruption and insertion of the lacZ reporter gene in the mouse SM22α locus, a targeting vector was constructed in which the lacZ gene was inserted in-frame at the SM22α initiation codon (ATG), and the remainder of exon 2, intron 2, exon 3, and part of intron 3 were replaced with the phosphoglycerokinase-neomycin (neo) cassette (Fig. 1A). The linearized targeting vector was electroporated into RW ES cells. Of 89 G418- and gancyclovir-resistant ES cell colonies screened, 6 were shown to be homologous recombinants by Southern blot analyses. Each of these SM22+/−LacZ clones contained a single site of integration of the vector in the host genome as determined by Southern blot analyses performed with a neo probe (data not shown).

Two independently derived SM22+/−LacZ ES cell lines were used to generate chimeric mice, and these mice were crossed to C57BL/6 mice to transmit the targeted allele through the germ line as determined by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B). Heterozygous SM22+/−LacZ mice were phenotypically normal and fertile. These mice were outbred to the BL/6 and CD1 background to produce heterozygotes that were intercrossed to generate homozygous SM22−/−LacZ mice. To confirm that a null mutation was created with this targeting strategy, Northern blot analyses were performed on RNA isolated from SMC-containing tissues (aorta and uterus) harvested from wild-type (SM22+/+), heterozygous (SM22+/−LacZ), and homozygous (SM22−/−LacZ) null mice. As anticipated, a 1.3-kb transcript corresponding to the expected size of SM22α mRNA was observed in samples of RNA prepared from the aorta (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 2) and uterus (data not shown) of wild-type and heterozygous mice. In contrast, hybridization of the radiolabeled SM22α cDNA probe to RNA samples prepared from the tissues of SM22−/−LacZ mice was not detected (Fig. 1C, lane 3). Western blot analyses performed with SM22α-specific polyclonal antiserum and tissue lysates prepared from the aorta of wild-type (SM22+/+), heterozygous (SM22+/−LacZ), and homozygous (SM22−/−LacZ) null mice revealed the expected 22-kDa band (Fig. 1D, lanes 1 and 2). In addition, a 20-kDa signal was reproducibly observed in lysates prepared from the aorta of wild-type (SM22+/+) and heterozygous (SM22+/−LacZ) mice. In contrast, no hybridization signal was detected in tissue lysates prepared from the aorta (Fig. 1D, lane 3) and uterus (data not shown) of homozygous SM22−/−LacZ null mice. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the gene targeting strategy utilized generated a null mutation in the gene encoding SM22α.

Transcriptional activation of the SM22α gene in the embryonic and adult mouse.

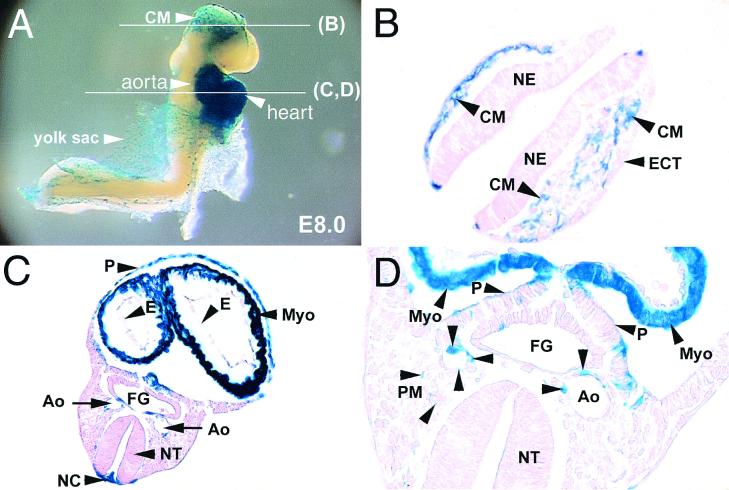

The gene targeting strategy effectively knocked in the bacterial lacZ reporter gene under the transcriptional control of the endogenous SM22α promoter, as well as other unidentified elements flanking and within the SM22α gene. To determine when and where in the postgastrulation embryo the SM22α gene is transcribed, E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryos were harvested from staged matings of SM22+/−LacZ × SM22+/−LacZ mice and stained for β-galactosidase activity. At E8.0, the process of “embryonic turning” is initiated, the heart consists of common atrial and ventricular chambers, and the unfused dorsal aortae are easily recognizable. In the E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryo, β-galactosidase activity (blue staining) was obvious within the head, heart, cardiac outflow tract, dorsal aorta, and yolk sac membranes (Fig. 2A). Sections obtained through the headfold revealed that lacZ-positive cells were restricted to the cephalic mesenchyme (Fig. 2B). No staining was observed within the neuroepithelium or surface ectoderm (Fig. 2B). Sections through the superior thoracic cavity revealed blue-stained pericardial and myocardial cells. In contrast, the single layer of endocardial cells did not express β-galactosidase (Fig. 2C). In addition, blue-stained cells were reproducibly observed surrounding the paired dorsal aorta (Fig. 2C and D, A.). Of note, this is 24 to 36 h prior to the reported expression of genes encoding SMC markers in the mouse embryo (27). Finally, scattered blue stained cells were observed within the paraxial mesoderm (Fig. 2D), which gives rise to the somites and in the notochord (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

The SM22α gene is activated in the dorsal aorta of the E8.0 embryo. E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryos harvested from staged matings of SM22+/−LacZ × SM22+/−LacZ mice genotyped by Southern blot analyses and stained for β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Whole-mount β-galactosidase activity in an E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryo. β-Galactosidase activity (blue staining) is observed in the embryonic heart, aorta, cephalic mesenchyme (CM), and yolk sac. The planes of the sections shown in panels B, C, and D are indicated by white lines. (B) Cross-section through the head of an E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryo showing β-galactosidase activity restricted to cells within the cephalic mesenchyme (CM). Staining was not observed in the surface ectoderm (ECT) or neuroepithelium (NE). (C) Cross-section through the thoracic cavity of an E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryo demonstrating β-galactosidase activity in the myocardium (Myo), pericardium (P), aorta (Ao), and notochord (NC). (D) High-power view of a section through the thoracic cavity of an E8.0 SM22+/−LacZ embryo demonstrating β-galactosidase activity in cells surrounding the paired dorsal aorta (Ao). In addition, faint blue staining is observed in scattered cells within the paraxial mesoderm (PM), which gives rise to the somites.

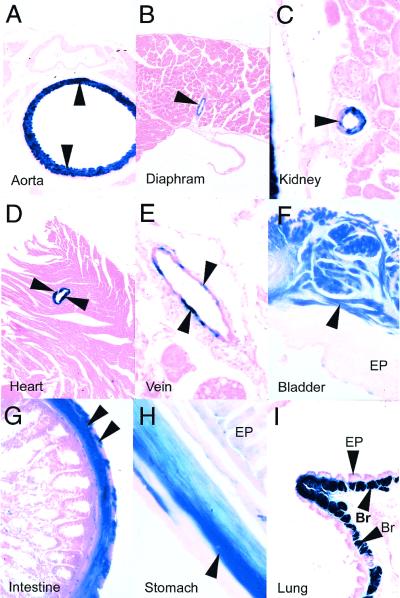

Histochemical analyses of adult SM22+/−LacZ mice revealed, as anticipated, β-galactosidase activity (blue-stained cells) in the tunica media of the major and branch arteries, including the aorta (Fig. 3A) and the diaphragmatic arteries (Fig. 3B). Blue staining was also observed within arterioles (Fig. 3C, arrow) located within the kidneys and other tissues. This pattern of expression recapitulated the pattern of lacZ expression observed in transgenic mice harboring the mouse SM22α promoter (14, 19, 22). However, in contrast to the pattern of β-galactosidase activity observed in SM22α promoter-driven transgenic mice, the coronary arteries, which have a unique embryological derivation, also stained dark blue (Fig. 3D). Similarly, venous (Fig. 3E) and visceral SMCs, including those in the bladder (Fig. 3F), intestine (Fig. 3G), and stomach (Fig. 3H), as well as the bronchial SMCs (Fig. 3I, Br), were β-galactosidase positive in SM22+/−LacZ mice. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the SM22α gene is activated at least 24 to 36 h prior to the documented expression of SMC markers in presumptive vascular SMCs. In addition, these data demonstrate that the knock-in of the lacZ gene into the endogenous SM22α locus restricts β-galactosidase gene expression to vascular and visceral SMCs during postnatal development in the mouse.

FIG. 3.

β-Galactosidase activity in SM22+/−LacZ mice is restricted to vascular and visceral SMCs. Tissues were harvested from SM22+/−LacZ mice, fixed, stained with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase activity (blue staining) was observed in the tunica media of the aorta (A), the diaphragmatic arteries (B), the tunica media of resistance arterioles (arrow) within the kidneys (C), the right coronary artery (D), veins (E), the muscular wall of the bladder (F), the lamina propria of the small intestine (G), and the muscular wall of the stomach (H), as well as in bronchial SMCs (Br) surrounding the bronchial epithelium (EP) (I).

Analyses of SM22α-deficient mice.

As shown in Table 1, among 127 live-born offspring from SM22+/−LacZ × SM22+/−LacZ matings, 32 wild-type (SM22+/+), 55 heterozygous (SM22+/−LacZ), and 40 homozygous (SM22−/−LacZ)-null mice were generated. This ratio does not differ significantly from the expected Mendelian distribution, demonstrating that SM22α-deficient mice survive to birth. The weight of age-matched littermates also did not differ significantly between wild-type, heterozygous, and SM22α-null mice. In addition, the SBP and HR of conscious adult wild-type (SM22+/+) and SM22α-deficient mice (SM22−/−LacZ) did not differ significantly (Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest that SM22α is not required for basal homeostatic functions mediated by SMCs in the developing mouse.

TABLE 1.

Physiological parameters in wild-type and SM22α-deficient mice

| Mouse group | No. of animals | Mean SBP ± SEM | Mean HR ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (+/+) | 32 | 119.4 ± 7.0 | 672.6 ± 28.5 |

| Heterozygous (+/−) | 55 | NDa | ND |

| Homozygous null (−/−) | 40 | 109.9 ± 14.9b | 643.8 ± 31.8b |

ND, not determined.

P > 0.05 (+/+ mice versus −/− mice).

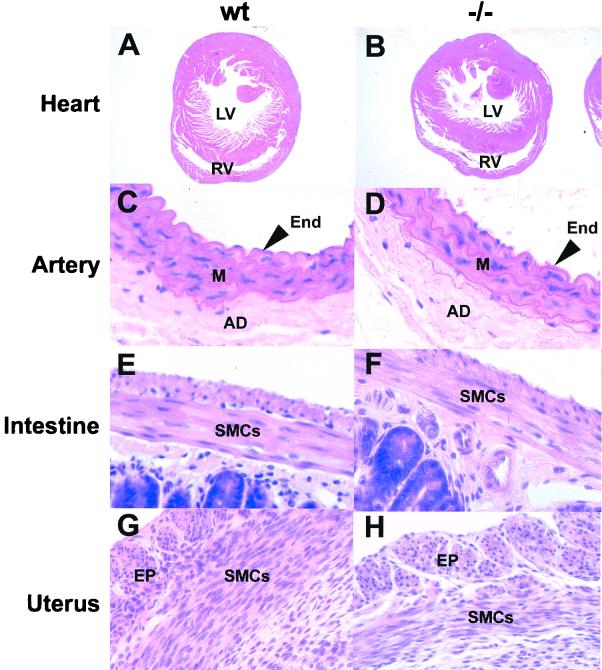

To determine whether SM22α was required for the normal development of the mouse, tissues obtained from SM22α-deficient mice and their control littermates were compared (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 2, the SM22α gene is expressed at high levels in the embryonic heart. However, hearts obtained from SM22α-deficient mice were indistinguishable from their control littermates (compare Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, the results of an echocardiographic comparison of chamber size, ventricular wall thickness, and indices of contractile function, including left ventricular fractional shortening and ejection fraction, did not differ significantly (data not shown). Similarly, the arteries and veins of wild-type and SM22α-deficient adult mice were virtually indistinguishable, including quantitative morphometric analyses of the arterial intima to media ratios (compare Fig. 4C and D). In addition, visceral organs obtained from wild-type and SM22α-deficient mice, including the small intestine (compare Fig. 4E and F) and uterus (compare Fig. 4G and H), developed normally and were histologically indistinguishable.

FIG. 4.

SMC-containing tissues develop normally in SM22α-deficient mice. Tissues harvested from wild-type (wt) and SM22α-deficient (−/−) mice were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described in Materials and Methods. (A and B) Comparison of hearts from wild-type (A) and −/− (B) mice demonstrating normal left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) chamber dimensions and morphology. (C and D) Comparison of the aorta harvested from a wild-type (C) and −/− (D) adult mouse demonstrating normal tunica intima (End), tunica media (M), and adventitia (AD). (E and F) Comparison of small intestine harvested from wild-type (E) and −/− (F) mice demonstrating intact lamina propria and intestinal epithelium (EP). (G and H) Comparison of uterus harvested from wild-type (G) and −/− (H) mice demonstrating normal SMC arrangement within the muscular layers (SMCs) of the uterus.

Ultrastructural analyses of SM22α-deficient SMCs.

SM22α colocalizes to the cytoskeleton of SMCs (38, 39, 41). Therefore, it was of interest to define the subcellular localization of SM22α in SMCs and to determine whether SM22α-deficient SMCs exhibited alterations in cytoskeletal architecture. A 3-D reconstruction of A7r5 SMCs that stably expressed a Ds-Red-tagged SM22α protein revealed localization to the F-actin filament bundles (Fig. 5A). This pattern of expression was identical to that observed when these cells were stained with the actin-binding protein phalloidin (data not shown). Immunogold localization of SM22α protein performed using affinity-purified SM22α polyclonal antiserum revealed gold particles (black dots) localizing to longitudinally oriented actin filaments in the cytoplasm and patches at the cell periphery (Fig. 5B). In addition, gold-labeled SM22α protein was also observed on the surface of some myosin bundles (dark patches in Fig. 5B). Signal (black dots in Fig. 5B) was not detected in the extracellular space, fibroblasts, or endothelial cells (data not shown). Hybridization to actin filaments (or other subcellular structures and organelles) was not observed in control experiments performed by substituting rabbit IgG for affinity-purified rabbit anti-SM22α IgG. These data confirm that SM22α is a component of the SMC cytoskeleton that colocalizes localizes with filamentous actin.

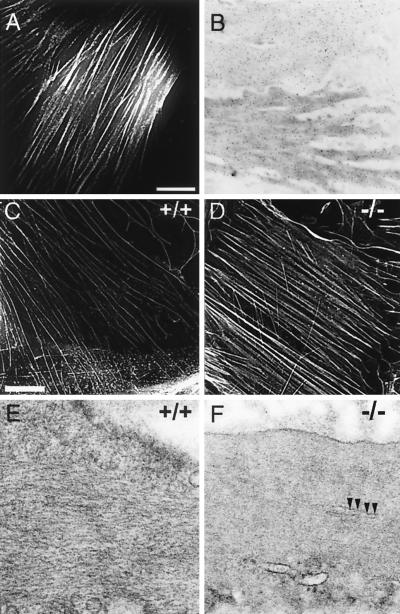

FIG. 5.

Cytoskeletal organization of wild-type and SM22α-deficient SMCs. (A) Cellular localization of Ds-Red-tagged SM22α in A7r5 SMCs. 3-D fluorescence images of A7r5 cells that stably express Ds-RED epitope-tagged SM22α were acquired using a Delta Vision micrscopy system, and image restoration and volume projections were computed as described in Materials and Methods. SM22α protein (white lines) localized to actin filament bundles. (B) Subcellular distribution of SM22α in the intact mouse aorta. Ultrathin sections of mouse aorta were incubated with affinity-purified anti-SM22α polyclonal antiserum. The sections were then incubated with gold-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and stained with uranyl acetate. The anti-SM22α antibody (black dots) hybridized to longitudinally oriented actin filaments located throughout the cytoplasm and at the cell periphery. (C and D) 3-D fluorescence images of primary mouse aortic SMCs isolated from a wild-type (C) and SM22α-deficient (D) mouse stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin. Actin filament bundles (white lines) form well-organized rib-like arrays in the SM22α-deficient mouse (−/−, D) and its control littermate (+/+, C). No significant differences in fluorescence intensity in staining were detected. Bar, 1 μm. (E and F) Ultrastructural comparison of SMCs in the intact bladder of wild-type (E) and SM22α-deficient (F) mice. The bladder was fixed, embedded, sectioned, and stained, and images were generated with a Philips CM-100 electron microscope as described in Materials and Methods. Compared to the SMCs in the wild-type bladder which demonstrate obvious well-spaced, longitudinally oriented actin filaments (+/+, F), the cytoplasm of SM22α-deficient SMCs appears to be homogeneous, reflecting differences in spacing of the actin filaments. This resulted in more-condensed-appearing cytoplasmic bundles (arrows). Magnification, ×104,125.

To determine whether SM22α-deficient SMCs display normal cytoskeletal organization, 3-D fluorescence images of primary aortic SMCs isolated from wild-type (SM22+/+) and SM22α-null (SM22−/−LacZ) mice were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin and then compared after deconvolution and image restoration. In both wild-type aortic SMCs (Fig. 5C) and SM22α-deficient SMCs (Fig. 5D), rib-like arrays of actin filament bundles were observed throughout the cytoplasm. Consistent with this observation, no significant differences were observed in the pattern of α-actinin, desmin, and β-tubulin expression in aortic SMCs isolated from wild-type and SM22α-deficient mice (data not shown). Electron microscopic examination of SM22α-deficient SMCs within the tunica media of the aorta and the bladder revealed no obvious ultrastructural abnormalities (compare Fig. 5E and F). There were no signs of cell death, degeneration, or fragmentation in SM22α-deficient SMCs. SM22α-null SMCs demonstrated a centrally located nucleus, normal organelle content and structure, and an intact plasma membrane with marginal vesicles (data not shown). Many of the wild-type and SM22−/−LacZ SMCs showed indentation of the nuclear envelope caused by muscular contraction. All of the SM22α-deficient SMCs contained abundant cytoskeletal filaments in the form of nonbanding bundles that ran parallel to the longitudinal axis of the cells. In addition, dense bodies were observed within the cytoplasm and at the cell periphery. The only discernible difference observed between wild-type (+/+) and SM22α-deficient (−/−) SMCs was the more homogeneous appearance of the cytoplasm in SM22α-deficient SMCs that reflects a difference in the spacing of myofilaments. This resulted in condensed-appearing ctyoplasmic bundles in SM22α-deficient SMCs within the bladder (arrow in Fig. 5F) and aorta (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that targeted mutation in the gene encoding SM22α does not result in a gross disruption of cytoskeletal organization.

DISCUSSION

SM22α is a cytoskeletal protein that is expressed abundantly and exclusively in SMCs during postnatal development. In the studies described here, gene targeting was used to generate mice harboring a null mutation in the gene encoding SM22α and insertion of the lacZ gene into the SM22α locus. Analyses of heterozyogous SM22+/−LacZ embryos revealed that the SM22α gene is transcribed in the dorsal aorta at E8.0, serving to identify this as the earliest recognized event in the developmental program leading to differentiation of vascular SMCs from undifferentiated mesenchyme. During postnatal development, β-galactosidase activity was restricted to visceral and vascular SMCs. This pattern of distribution recapitulates the expression pattern of the endogenous SM22α gene but differs significantly from SM22α promoter-driven transgenic mice (14, 19, 22, 43). SM22α-deficient mice are viable and fertile and exhibit no obvious phenotypic abnormalities. SMC-containing tissues, including the vasculature, heart, uterus, stomach, intestine, and bladder, all developed normally. Consistent with these findings, the cytoskeletal organization of SM22α-deficient and wild-type vascular and visceral SMCs is virtually indistinguishable.

Our group and others have reported that the SM22α promoter restricts expression of a lacZ reporter gene to arterial SMCs in transgenic mice (14, 19, 22, 43). In SM22α promoter-driven transgenic mice, β-galactosidase activity is not observed in venous, coronary arterial, or visceral SMCs despite the fact that the endogenous SM22α gene is expressed in these cells. This led to the hypothesis that distinct transcriptional programs distinguish tissue-restricted subsets of SMCs or SMC sublineages. This hypothesis was supported by the finding that the smooth muscle α-actin promoter and intragenic enhancer (20), the smooth muscle myosin heavy-chain promoter and intragenic enhancer (21), the telokin promoter (10), and the γ-enteric actin promoter (30) restrict transgene expression to unique tissue-restricted subsets of SMCs in transgenic mice. It is noteworthy that each of these transcriptional regulatory elements also contains a functionally important CArG box that binds directly to the MADS box transcription factor SRF. The observed β-galactosidase activity in visceral and vascular SMCs of SM22+/−LacZ mice is consistent with this model and leads us to predict that additional, as-yet-unidentified, transcriptional regulatory elements required for expression in venous, coronary arterial, and visceral SMCs exist and are located in distant regions flanking the SM22α gene. Identification and characterization of these regulatory elements should provide fundamental insights into the transcriptional programs that distinguish SMC sublineages.

Relatively little is currently understood about the transcriptional programs and signaling pathways that regulate the specification of SMCs from undifferentiated mesenchyme during embryonic development (for a review, see references 27 and 28). The differentiation of SMCs from mesenchyme is a critical event in angiogenic patterning that ultimately distinguishes arteries, veins, and capillary beds. In the mouse, SMC markers, including SM–α-actin, calponin, and SM22α, had been detected as early as E9.5 in the dorsal aorta (27). Therefore, we were surprised to detect β-galactosidase activity in the dorsal aorta of E8.0 unturned SM22+/−LacZ embryos. These data suggest that the signaling pathways that regulate the specification and the differentiation of vascular SMCs from the mesenchyme are activated earlier in the developing mouse embryo than was recognized previously. As such, the SM22+/−LacZ mouse and lacZ-tagged SMCs isolated from these mice may serve as valuable experimental reagents for studying the molecular basis of SMC differentiation. Moreover, because SM22α is downregulated in concert with other contractile proteins in atherosclerotic lesions (35–37), these mice may be used to examine the molecular mechanisms that modulate SMC phenotype and to examine the pathological mechanisms underlying vascular proliferative syndromes.

What then is the function of the cytoskeletal protein SM22α in SMCs and other embryonic tissues, including the developing heart and skeletal muscle? SM22α colocalizes with actin filaments and is abundantly expressed in contractile SMCs. It has been conserved through evolution and shows high-level sequence identity to the myofibrillar regulatory protein calponin. However, SM22α-deficient mice are viable and fertile and exhibit no overt phenotype. SMC-containing tissues, including arteries, veins, heart, gut, uterus, and bladder, develop normally. Basal homeostatic functions regulated in whole or in part by SMCs, including the regulation of blood pressure, bladder control, uterine contraction, and gastrointestinal motility, are not grossly altered in SM22α-deficient mice. Consistent with these data, the SMC ultrastructure and cytoskeletal organization in SM22α-deficient mice is virtually indistinguishable from their control littermates. It remains theoretically possible that SM22α is partially redundant with another structurally related protein such as calponin. In this regard, it is noteworthy that we recently cloned a novel mouse cDNA encoding a protein with greater than 70% sequence identity to SM22α that is also expressed in some SMC containing tissues (J. Zhang and M. Parmacek, unpublished data). Alternatively, SM22α may not be required for basal homeostatic functions but may be required for stress responses such as wound healing. The availability of SM22α-deficient mice allows these and other possibilities to be examined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lisa Gottschalk for her help preparing the figures, Angie Boyce for expert secretarial assistance, and Theodore J. Plappert for technical assistance in performing echocardiography.

This project was supported in part by NIH NRSA grants HL10058 to B.P.H. and NIH-R0156915 to M.S.P. M.S.P. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almendral J M, Santaren J F, Perera J, Zerial M, Bravo R. Expression, cloning and cDNA sequence of a fibroblast serum-regulated gene encoding a putative actin-associated protein (p27) Exp Cell Res. 1989;181:518–530. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayme-Southgate A, Lasko P, French C, Pardue M L. Characterization of the gene for mp20: a Drosophila muscle protein that is not found in asynchronous oscillatory flight muscle. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:521–531. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley A. Production and analysis of chimaeric mice. In: Robertson E J, editor. Teratocarcinomas and embryonic stem cells: a practical approach. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1987. pp. 113–151. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan Y M, Yu Q C, Fine J D, Fuchs E. The genetic basis of Weber-Cockayne epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7414–7418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang M W, Barr E, Seltzer J, Jiang Y-Q, Nabel G J, Nabel E G, Parmacek M S, Leiden J M. Cytostatic gene therapy for vascular proliferative disorders with a constitutively active form of the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1995;267:518–522. doi: 10.1126/science.7824950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duband J L, Gimona M, Scatena M, Sartore S, Small J V. Calponin and SM22 as differentiation markers of smooth muscle: spatiotemporal distribution during avian embryonic development. Differentiation. 1993;55:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1993.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fentzke R C, Korcarz C E, Lang R M, Lin H, Leiden J M. Dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative CREB transcription factor in the heart. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2415–2426. doi: 10.1172/JCI2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goetinck S, Waterston R H. The Caenorhabditis elegans muscle-affecting gene unc-87 encodes a novel thin filament associated protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:79–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmke B P, Goldman R D, Davies P F. Rapid displacement of vimentin intermediate filaments in living cells exposed to flow. Circ Res. 2000;86:745–752. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herring B P, Smith A F. Telokin expression is mediated by a smooth muscle cell-specific promoter. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1656–C1665. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.6.C1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiraoka Y, Sedat J W, Agard D A. Determination of three-dimensional properties of a light microscope system: partial confocal behavior in epifluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1990;57:325–333. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82534-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan B, Beddington R, Constantini F, Lacy E, editors. Manipulating the mouse embryo. 2nd ed. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.James A L, Pare P D, Hogg J C. The mechanics of airway narrowing in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:242–246. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Ip H S, Lu M M, Clendenin C, Parmacek M S. A serum response factor-dependent transcriptional regulatory program identifies distinct smooth muscle cell sublineages. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2266–2278. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo C T, Morrisey E E, Anandappa R, Sigrist K, Lu M M, Parmacek M S, Soudais C, Leiden J M. GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1048–1060. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawson D, Harrison M, Shapland C. Fibroblast transgelin and smooth muscle SM22α are the same protein, the expression of which is down-regulated in many cell lines. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1997;38:250–257. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)38:3<250::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lees-Miller J P, Heeley D H, Smillie L B. An abundant and novel protein of 22 kDa (SM22) is widely distributed in smooth muscles. Purification form bovine aorta. Biochem J. 1987;244:705–709. doi: 10.1042/bj2440705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Miano J M, Cserjesi P, Olson E N. SM22α, a marker of adult smooth muscle, is expressed in multiple myogenic lineages during embryogenesis. Circ Res. 1996;78:188–195. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Miano J M, Mercer B, Olson E N. Expression of the SM22α promoter in transgenic mice provides evidence for distinct transcriptional regulatory programs in vascular and visceral smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:849–859. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack C P, Owens G K. Regulation of smooth muscle α-actin expression in vivo is dependent on CArG elements within the 5′ and first intron promoter regions. Circ Res. 1999;84:852–861. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madsen C S, P. R C, Hungerford J E, White S L, Manabe I, Owens G K. Smooth muscle-specific expression of the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene in transgenic mice requires 5′-flanking and first intronic DNA sequence. Circ Res. 1998;82:908–917. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moessler H, Mericskay M, Li Z, Nagl S, Paulin D, Small J V. The SM22 promoter directs tissue-specific expression in arterial but not in venous or visceral smooth muscle cells in transgenic mice. Development. 1996;122:2415–2425. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrisey E E, Ip H S, Tang Z, Parmacek M S. GATA-4 activates transcription via two novel domains that are conserved within the GATA-4/5/6 subfamily. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8515–8524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrisey E E, Tang Z, Sigrist K, Lu M M, Jiang F, Ip H S, Parmacek M S. GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3579–3590. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newby A C, Zaltsman A B. Fibrous cap formation or destruction—the critical importance of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration and matrix formation. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:345–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.North A J, Gimona M, Lando Z, Small J V. Actin isoform compartments in chicken gizzard smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:445–455. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens G K. Molecular control of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:623–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1998.tb10706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parmacek, M. S. Transcriptional programs regulating vascular smooth muscle cell development and differentiation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Parmacek M S, Leiden J M. Structure and expression of the murine slow/cardiac troponin C gene. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13217–13225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian J, Kumar A, Szuscik J C, Lessard J L. Tissue and developmental specific expression of murine smooth muscle γ-actin fusion genes in transgenic mice. Dev Dyn. 1996;207:135–144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199610)207:2<135::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren W, Ng G Y K, Wang R-X, Wu P H, O'Dowd B F, George S, Osmond D H, Liew C. The identification of NP25: a novel protein that is differentially expressed by neuronal subpopulations. Mol Brain Res. 1994;22:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross R. Mechanisms of disease: atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samaha F F, Ip H S, Morrisey E E, Seltzer J, Tang Z, Solway J, Parmacek M S. Developmental pattern of expression and genomic organization of the calponin-h1 gene; a contractile smooth muscle cell marker. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:395–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz S M, Murry C E. Proliferation and the monoclonal origins of atherosclerotic lesions. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:437–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanahan C M, Cary N R B, Metcalfe J C, Weissberg P L. High expression of genes for calcification-regulating proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:2393–2402. doi: 10.1172/JCI117246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanahan C M, Weissberg P L. Smooth muscle cell heterogeneity: Patterns of gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;183:333–338. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shanahan C M, Weissberg P L, Metcalfe J C. Isolation of gene markers of differentiated and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1993;73:193–204. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapland C, Hsuan J J, Totty N F, Lawson D. Purification and properties of transgelin: a transformation and shape change sensitive actin-gelling protein. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1065–1073. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.5.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapland C, Lowings P, Lawson D. Identification of new actin-associated polypeptides that are modified by viral transformation and changes in cell shape. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:153–161. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Small J V. Geometry of actin-membrane attachments in the smooth muscle cell: the localisations of vinculin and α-actinin. EMBO J. 1985;4:45–49. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb02315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Small J V, Gimona M. The cytoskeleton of the vertebrate smooth muscle cell. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:341–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Small J V, Sobieszek A. Studies on the function and composition of the 10-nm (100-A) filaments of vertebrate smooth muscle. J Cell Sci. 1977;23:243–268. doi: 10.1242/jcs.23.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solway J, Seltzer J, Samaha F F, Kim S, Alger L E, Niu Q, Morrisey E E, Ip H S, Parmacek M S. Structure and expression of a smooth muscle cell-specific gene, SM22α. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13460–13469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi K, Nadal-Ginard B. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of smooth muscle calponin. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:13284–13288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thweatt R, Lumpkin C K, Goldstein S. A novel gene encoding a smooth muscle protein is overexpressed in senescent human fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Commun. 1992;187:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tybulewicz V L J, Crawford C E, Jackson P K, Bronson R T, Mulligan R C. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell. 1991;65:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]