Abstract

Purpose

The mobilization of most available hospital resources to manage coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may have affected the safety of care for non-COVID-19 surgical patients due to restricted access to intensive or intermediate care units (ICU/IMCUs). We estimated excess surgical mortality potentially attributable to ICU/IMCUs overwhelmed by COVID-19, and any hospital learning effects between two successive pandemic waves.

Methods

This nationwide observational study included all patients without COVID-19 who underwent surgery in France from 01/01/2019 to 31/12/2020. We determined pandemic exposure of each operated patient based on the daily proportion of COVID-19 patients among all patients treated within the ICU/IMCU beds of the same hospital during his/her stay. Multilevel models, with an embedded triple-difference analysis, estimated standardized in-hospital mortality and compared mortality between years, pandemic exposure groups, and semesters, distinguishing deaths inside or outside the ICU/IMCUs.

Results

Of 1,870,515 non-COVID-19 patients admitted for surgery in 655 hospitals, 2% died. Compared to 2019, standardized mortality increased by 1% (95% CI 0.6–1.4%) and 0.4% (0–1%) during the first and second semesters of 2020, among patients operated in hospitals highly exposed to pandemic. Compared to the low-or-no exposure group, this corresponded to a higher risk of death during the first semester (adjusted ratio of odds-ratios 1.56, 95% CI 1.34–1.81) both inside (1.27, 1.02–1.58) and outside the ICU/IMCU (1.98, 1.57–2.5), with a significant learning effect during the second semester compared to the first (0.76, 0.58–0.99).

Conclusion

Significant excess mortality essentially occurred outside of the ICU/IMCU, suggesting that access of surgical patients to critical care was limited.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-023-07000-3.

Keywords: COVID-19, Critical care, Surgical mortality, Patient safety

Take-home message

| This nationwide study demonstrated a considerable increase in surgical mortality among non-COVID-19 patients during periods of high hospital exposure to many COVID-19 cases in their ICU/IMCU beds. Excess in-hospital mortality resulted essentially from inpatient deaths outside of the ICU/IMCU, suggesting that access of surgical patients to critical care was limited |

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in millions of deaths worldwide in 2020 [1]. Successive waves of SARS-CoV-2 had both direct and indirect effects on population mortality in high-income countries [2, 3]. In addition to the high mortality of COVID-19 itself [4, 5], the pandemic necessitated the sudden freeze of surgical services to liberate critical care beds and staff [6]. This, in turn, resulted in a significant reduction in patient access to necessary surgical procedures [7], as well as a lack of available resources to care for patients who experienced surgical complications [8, 9].

France experienced two significant pandemic waves in 2020, one each semester, triggering nationwide lockdowns and the cancelation of surgeries. Between the two periods, a tremendous amount of knowledge was rapidly shared worldwide regarding pandemic management strategies, enabling many health systems to adapt and restore access to safe surgery [10, 11]. However, the mobilization of most available resources and the prioritization placed on treating COVID-19 cases at the hospital may have affected the care of non-COVID-19 surgical patients due to restricted access to intensive or intermediate care units (ICU/IMCUs) [12].

We hypothesized that high occupancy of ICU/IMCU beds with COVID-19 cases may have jeopardized surgical safety and the capacity to treat patients experiencing complications. This nationwide investigation of a global health crisis sought to estimate excess mortality among operated patients potentially attributable to ICU/IMCUs overwhelmed by COVID-19, and to identify any hospital learning effect between two successive waves during the pandemic’s first year.

Methods

Study design and population

We used a triple-difference approach to investigate the association between hospital exposure to COVID-19 within the ICU/IMCU (definition in electronic supplementary material (ESM), sMethod 1) and in-hospital mortality risk among non-COVID-19 surgical patients and to evaluate possible improvement across semesters [13]. The first difference measured the changes in surgical mortality between the exposure year (2020) and the year preceding exposure (2019). The second compared changes in mortality among the 2 years between patients who underwent surgery in hospitals differentially exposed to COVID-19 within their ICU/IMCUs over time. The third estimated whether the differences across years and pandemic exposure changed between the first (January 1 to June 30) and second (July 1 to December 31) semesters to underline a learning effect between the two pandemic waves (design in ESM 1, sMethod 2).

The population included all adults admitted to French public and private hospitals that provided regular surgical care for non-ambulatory surgery from Jan 1, 2019 to Dec 31, 2020. We only selected patients who underwent open or videoscopic surgical procedures with a potential death risk greater than 0.1% in the following specialties: cardiovascular, digestive, neurological, orthopedic, thoracic, and urogenital. We excluded surgical patients experiencing symptomatic COVID-19-infection during their hospital stay from analyses, formally diagnosed with acute respiratory infection or other symptoms (e.g., diarrhea), and with biologically identified SARS-CoV-2 virus or other positive signs (e.g., chest scan).

For each operated patient, the corresponding pandemic exposure was determined a priori using the median of the daily proportion of COVID-19 patients among all patients treated within the ICU/IMCUs of the same hospital during his/her stay (calculation in sMethod 3). Patients were then categorized into low-or-no (< 30%), moderate (from 30 to 60%), and high-exposure (> 60%) categories using official thresholds established by the French Ministry of Health to distinguish levels of ICU/IMCU occupancy in hospitals during the pandemic [14]. This definition of pandemic exposure considered change in exposure day by day during the study period for each hospital [15]. On the one hand, exposure of patients operated during the pandemic in 2020 corresponded to the “true exposure” they experienced during their stay. On the other hand, exposure of control patients operated in 2019, before the pandemic, corresponded to a mirrored “fictional exposure” that each of those patients would have endured during their stay, should they have undergone a surgery on the same dates and within the same hospital in 2020.

Data sources

We analyzed the nationwide French hospital database (Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d’Information, source: ATIH). The data are prospectively collected by the clinicians in charge of their patients and completed by professionals from the medical information department present in each hospital. The database relies on a coding system with strict definitions for variables, and experts from national health insurance regularly audit a subset of records in every hospital to avoid coding errors. Inpatient stays are recorded as standard discharge abstracts containing compulsory information about patients and their diagnoses using the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision as well as procedural codes associated with the care provided. Because of the exhaustive data collection from the PMSI database, no patients were lost to follow-up.

We extracted the patients’ demographics, comorbidities [16], frailty scores [17], emergency room admission before surgery, the date of the surgical procedure performed with the corresponding specialty and severity, ICU/IMCU admission following the surgery, patient vital status at discharge from ICU/IMCU and hospital stay, as well as the hospital status (academic, public-not-for-profit, and private-for-profit) and location area (Greater Paris, North–East, South–East, North–West, South–West). Patient median household income was obtained from their residential codes. Missing incomes were imputed using the median value of inpatient stays performed that year in the same hospital.

The study outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality up to 30 days following surgery. We considered deaths among all surgical patients occurring inside or outside the ICU/IMCUs separately.

This study was strictly observational and based on anonymous data. In accordance with the French ethical directives, informed consent from its participants was waived and the study was approved by the National Data Protection Commission (CNIL N°F20210401171145).

Statistical analysis

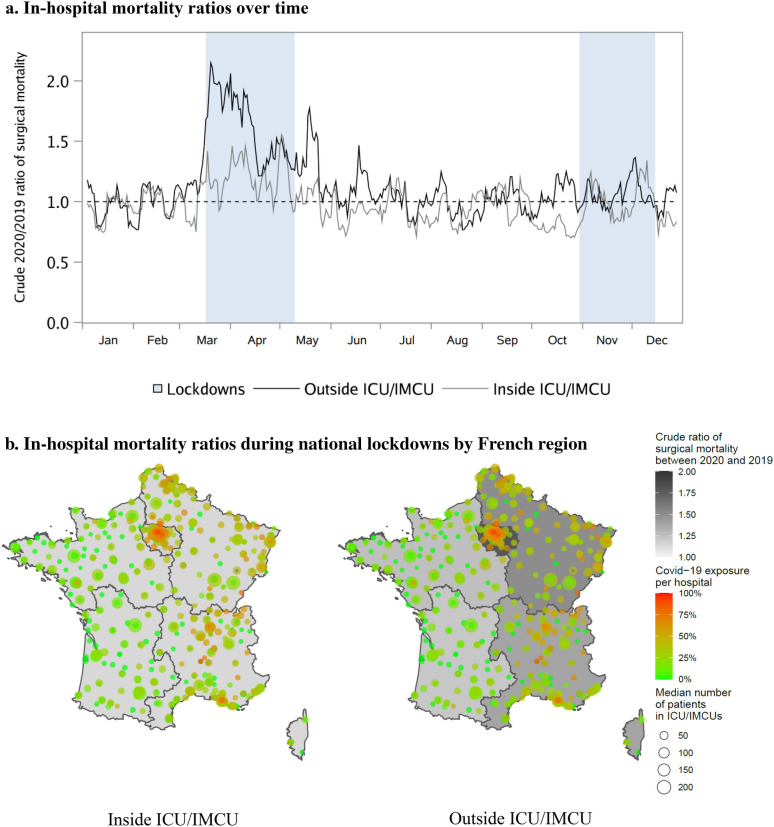

We described characteristics of inpatient stays across years and pandemic exposure levels. Crude ratios of surgical mortality between 2020 and 2019 were plotted over time and mapped by geographic area in relation to hospital ICU/IMCU exposure to the pandemic.

We modeled the triple-difference between years, pandemic exposure and semesters with surgical mortality using multilevel logistic regression based on Generalized Estimating Equations (SAS proc genmod) and an exchangeable working correlation structure to account for patients clustering within hospitals [18]. For each semester, we first compared mortality change between the pre-exposure period (2019) and the exposure period (2020) within pandemic exposure groups using odds-ratios (ORs). The ratios of odds-ratios (RORs) then captured the changes on outcomes from 2019 to 2020 between high and low-or-no, high and moderate, and moderate and low-or-no exposure groups for each semester. A ROR greater than one indicated an increased mortality risk for patients. Finally, the ratios-of-ratios of odds-ratios (RRORs) captured the learning effect between the second and the first semesters for each of the previous comparisons. A RROR less than one indicated a decreased risk for the second semester. Models were adjusted for potential confounders, including patient age, sex, median household income, surgical procedure specialty and their related severity (quartiles of mortality by procedure in 2019), Elixhauser comorbidity index (0, 1, 2+), Hospital Frailty Risk Score (< 5, 5–15, > 15), emergency admission, ICU/IMCU admission following surgery, hospital status and location area, as well as any relevant or significant interaction between those variables. Model discrimination was assessed using the C-statistic. We added sensitivity analyses according to patient admission status for elective or emergency surgery, and subpopulation of patients admitted to the ICU/IMCU.

Using estimated parameters from these models and a marginal standardization method to control case-mix differences between exposure groups, we determined standardized in-hospital mortality rates and their absolute changes among each subgroup [19, 20]. Furthermore, we estimated excess deaths in 2020 among patients operated on in high- and moderate-exposure groups compared to the low-or-no exposure group. Mortality potentially attributable to pandemic exposure was derived from calculating etiologic fractions applied to the number of deaths observed. Associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed using non-parametric bootstrap based on 1000 replicates. We described inpatient stays using postoperative death inside versus outside ICU/IMCU by pandemic exposure group.

The Health Data Department of the Lyon University Hospital analyzed data using SAS (version 9.4 SASInstituteInc) and R (version 3.6.1 RCoreTeam) software for cartography (packages raster, sf and ggplot2).

Results

Among 1,870,515 stays of non-COVID-19 patients admitted for surgery in 655 hospitals (flowchart in ESM 1, sFigure 1), 37,666 (2%) experienced death, including 21,284 (1.1%) inside the ICU/IMCU and 16,382 (0.9%) outside the ICU/IMCU. Table 1 presents the characteristics of operated patients before and after the pandemic by exposure group. Patients underwent more urgent and severe surgeries with lower ICU/IMCU admission rates during periods of medium to high COVID-19 exposure (ESM 1, sFigures 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of surgical inpatient stays by pandemic exposure group

| Characteristic | Low-or-no COVID-19 exposurea [0–30%] |

Moderate COVID-19 exposurea [30–60%] |

High COVID-19 exposurea [60–100%] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | Differenceb | 2019 | 2020 | Differenceb | 2019 | 2020 | Differenceb | |

| n = 860,208 | n = 795,016 | − 65,192 | n = 100,244 | n = 69,964 | − 30,280 | n = 31,258 | n = 13,825 | − 17,433 | |

| Mean patient age (years) | 64.7 | 65 | 0.3 | 64.7 | 65.3 | 0.6 | 63.8 | 64.8 | 1 |

| Male patient sex (%) | 50.3 | 50.3 | 0.1 | 49.5 | 49.2 | − 0.3 | 48.1 | 46.9 | − 1.2 |

| Mean patient household income (k€)c | 21.8 | 21.8 | 0 | 22.1 | 22.1 | 0.1 | 22.9 | 22.6 | − 0.2 |

| Mean patient Elixhauser (score) | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.1 |

| Mean patient hospital frailty risk (score) | 4.3 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 0.8 |

| Emergency admission (%) | 25.2 | 26.4 | 1.2 | 33.8 | 40 | 6.2 | 30.6 | 45.5 | 14.9 |

| Surgical procedure specialty (%) | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular | 13.8 | 14.1 | 0.3 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 0.1 | 10 | 8.3 | − 1.6 |

| Digestive | 31.8 | 31.9 | 0.1 | 32.7 | 33.6 | 0.8 | 36.2 | 37.9 | 1.7 |

| Neurological | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Orthopedic | 40.9 | 40.4 | − 0.5 | 42.8 | 40.8 | − 1.9 | 42.4 | 42.6 | 0.3 |

| Thoracic | 3.6 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 3 | 3.3 | 0.3 |

| Urogenital | 6.4 | 6.4 | − 0.1 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 0 | 6.5 | 5.9 | − 0.6 |

| Surgical procedure access (%) | |||||||||

| Open | 86.1 | 85.8 | − 0.3 | 85.6 | 85.2 | − 0.5 | 84.2 | 83.9 | − 0.3 |

| Videoscopic | 13.9 | 14.2 | 0.3 | 14.4 | 14.8 | 0.5 | 15.8 | 16.1 | 0.3 |

| Surgical procedure severityd (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 38.8 | 38.5 | − 0.2 | 37.6 | 35.1 | − 2.5 | 39.7 | 36.6 | − 3.1 |

| 2 | 29.7 | 29.2 | − 0.5 | 28.3 | 26 | − 2.3 | 29.5 | 24.2 | − 5.3 |

| 3 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 12.8 | 13.4 | 0.6 | 12.1 | 11.7 | − 0.3 |

| 4 | 18.5 | 19.2 | 0.7 | 21.3 | 25.5 | 4.2 | 18.7 | 27.4 | 8.7 |

| ICU/IMCU admissione (%) | 24.4 | 24.2 | − 0.2 | 19.2 | 18.3 | − 1 | 18 | 13.6 | − 4.5 |

| ICU admissione (%) | 8.1 | 8.4 | 0.3 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 0.3 | 7.4 | 6.5 | − 0.8 |

| IMCU admissione (%) | 20.3 | 19.6 | − 0.7 | 14.4 | 12.6 | − 1.9 | 13.4 | 9.2 | − 4.3 |

| Hospital status (%) | |||||||||

| Academic | 26.8 | 26.4 | − 0.3 | 31.6 | 30.2 | − 1.4 | 22.9 | 20.7 | − 2.2 |

| Public not for profit | 32.7 | 32.8 | 0 | 50.5 | 52.6 | 2.1 | 52.2 | 55.9 | 3.7 |

| Private for profit | 40.5 | 40.8 | 0.3 | 17.9 | 17.2 | − 0.7 | 24.9 | 23.5 | − 1.4 |

| Hospital location area (%) | |||||||||

| Greater Paris | 13.2 | 13.4 | 0.1 | 23.4 | 24.6 | 1.2 | 45.9 | 39.5 | − 6.4 |

| North–East | 22.2 | 22.3 | 0 | 26.2 | 25.2 | − 1 | 28.4 | 28.5 | 0 |

| North–West | 21.2 | 21.4 | 0.1 | 10.5 | 10.3 | − 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.1 |

| South–East | 26.8 | 26.6 | − 0.2 | 34 | 33.9 | − 0.1 | 23 | 29.1 | 6.1 |

| South–West | 16.5 | 16.4 | − 0.1 | 5.9 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise. Percentages might not sum to 100 because of rounding

aFor each operated patient, the corresponding pandemic exposure was determined a priori using the median of the daily proportion of COVID-19 patients among all patients treated within the ICU/IMCU beds of the same hospital during his/her stay, and then categorized into three categories of low-or-no [0–30%], moderate [30–60%], and high exposure [60–100%]. Exposure of patients operated during the pandemic in 2020 corresponded to the “true exposure” they experienced during their stay. Exposure of control patients operated in 2019, before the pandemic, corresponded to a mirrored “fictional exposure” that those patients would have endured during their stay, should they have undergone a surgery at the same dates and within the same hospital in 2020

bDifference was defined as 2020 minus 2019

c€1.00 (£0.83; US$1.11) as of March 2022

dSurgical procedure severity was considered in increasing quartiles according to the observed in-hospital mortality of each procedure in 2019

eICU/IMCUs were defined as intensive or intermediate care units

Figure 1 illustrates that observed surgical mortality ratios peaked during the national lockdowns. In-hospital mortality outside ICU/IMCUs culminated at 2.1 and 1.4 during the first and second lockdowns, and reached 1.6 and 1.3 inside ICU/IMCUs. Mapping of France during lockdown periods also revealed higher mortality ratios outside ICU/IMCUs in areas where hospitals were exposed to many COVID-19 cases (ratios ranging 1.22–1.8), while mortality inside ICU/IMCUs was similar across territories (1.14–1.17).

Fig. 1.

Crude ratios of surgical mortality rates between 2020 and 2019. a In-hospital mortality ratios over time. b In-hospital mortality ratios during national lockdowns by French region. ICU/IMCUs were defined as intensive or intermediate care units. Values in (a) are 7-day moving averages of 2020 to 2019 in-hospital mortality rate ratios from January to December. A mortality ratio of 2.0 means that the mortality rate in 2020 was twice the mortality rate in 2019. Bands mark the two periods of national lockdowns in France. The first lockdown took place from Mar 17 to May 10, 2020, and the second from Oct 30 to Dec 15, 2020. The timeframe of the maps in (b) consists of a combination of the two national lockdowns. Death rate ratios were defined as the ratio of the 2020 observed death rates divided by the 2019 observed death rates. The inside ICU/IMCU mortality ratio was greatest in the Greater Paris (1.17), followed very closely by the North–East (1.15), and the three other regions (1.14 for each). Outside ICU/IMCU, the greatest values were observed in the Greater Paris (1.80), followed by the North–East (1.51), the South–East (1.39), the North–West (1.26), and finally the South–West (1.22) of France. Circles on the map correspond to all hospitals included in this study. For each one of them, the COVID-19 exposure was calculated as the median of the daily proportion of COVID-19 patients in ICU/IMCUs during the lockdown periods

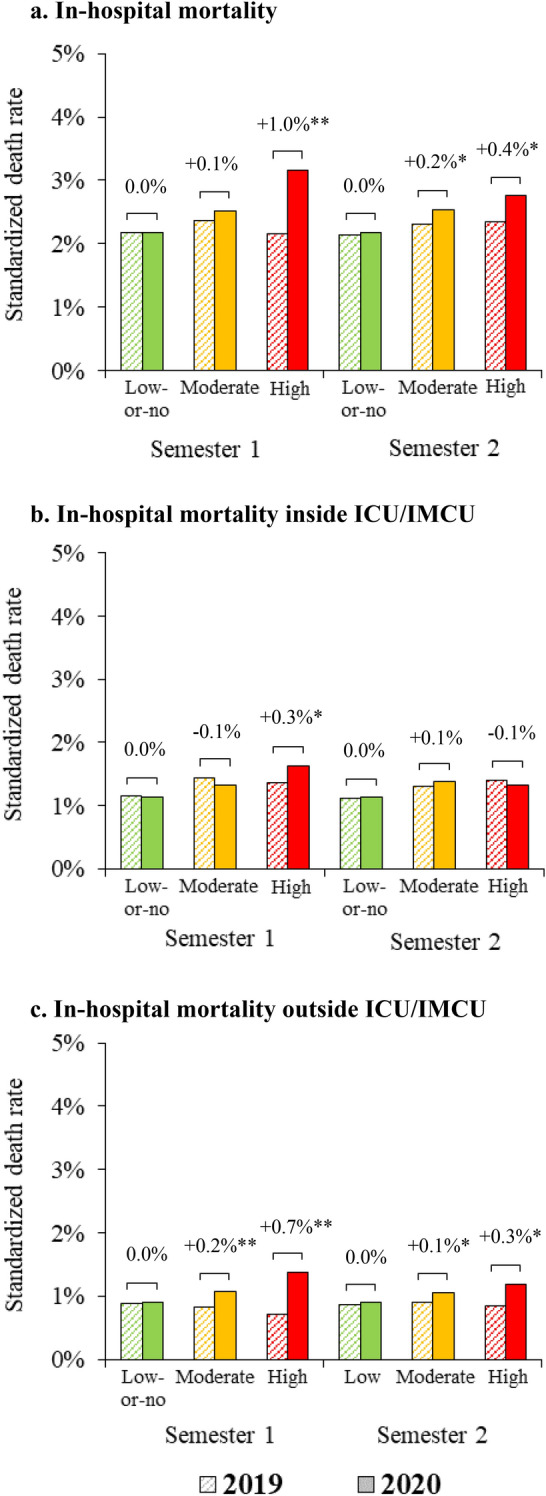

Figure 2 and sTable 1 in ESM 1 present differences in standardized mortality rates. No difference was demonstrated before and after the pandemic in the hospital groups with low-or-no exposure. Compared to 2019, overall mortality increased by 1.0% (95% CI 0.6–1.4%, P < 0.001) and 0.4% (0–1%, P = 0.05) among patients operated in hospitals highly exposed to the pandemic during the first and second semesters of 2020, representing a learning effect of − 0.6% (− 1.3–0%, P = 0.04). Regarding mortality outside of the ICU/IMCU, there was a 0.7% (0.3− 1%, P < 0.001) and 0.3% (0–0.7%, P = 0.03) increase in the high-exposure group during each semester, and a 0.2% (0–0.4%, P < 0.001) and 0.1% (0–0.3%, P = 0.03) increase in the moderate-exposure group. Such deterioration was not consistently observed for mortality inside the ICU/IMCU.

Fig. 2.

Difference in standardized surgical mortality rates between years by pandemic exposure group and semester. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001. ICU/IMCUs were defined as intensive or intermediate care units. The bar charts represent the standardized outcome rates per year, COVID-19 exposure group and semester (first Jan–June and second July–Dec). These standardized rates were calculated using estimated regression coefficients obtained from the triple-difference GEE models and a marginal standardization method to control case-mix differences between exposure groups. Differences above brackets indicate absolute differences in standardized rates between 2020 (exposure period) and 2019 (pre-exposure period) per semester in each pandemic exposure group (low-or-no [0–30%], moderate [30–60%], and high [60–100%])

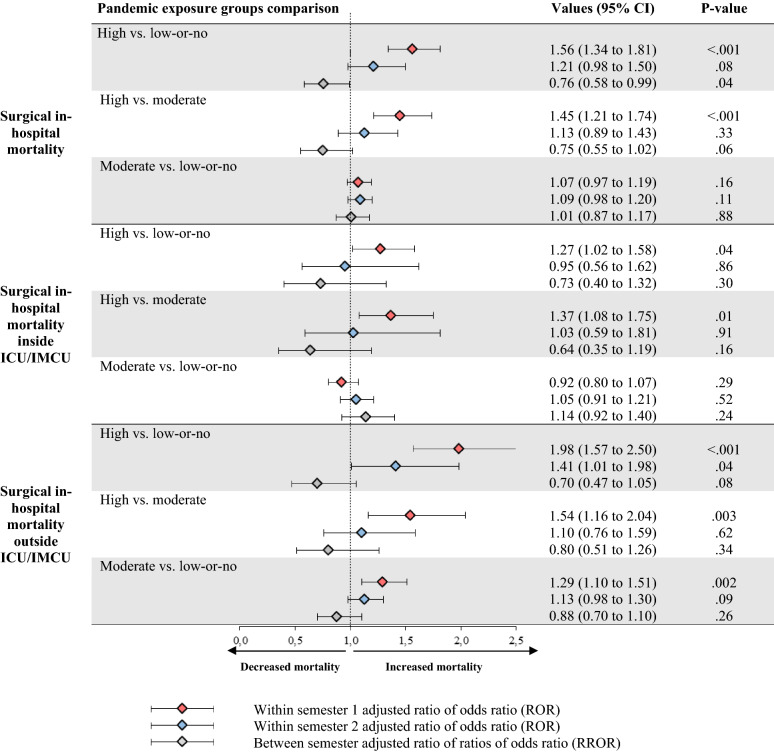

Figure 3 compares death risk between pandemic exposure groups across semesters. During the first semester, a significant increase in mortality (adjusted ratio of odds-ratios [aROR] 1.56, 95% CI 1.34–1.81) both inside ICU/IMCU (1.27, 1.02–1.58) and outside the ICU/IMCU (1.98, 1.57–2.5) was found in the high exposure compared to the low-or-no exposure group. The same trends were observed for the high versus the moderate-exposure group. In comparison with the first semester, a learning effect was observed during the second semester in the case of high exposure to the pandemic compared to low-or-no exposure (adjusted ratio of ratios of odds-ratios [aRROR] 0.76, 95% CI 0.58–0.99). Those estimates remained consistent in sensitivity analyses (ESM 1, sFigure 4).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of surgical mortality risk between pandemic exposure groups by semester with related learning effect. ICU/IMCUs were defined as intensive or intermediate care units. Adjusted ratios of odds-ratios (RORs) and adjusted ratios of ratio of odds ratio (RRORs) were obtained from the triple-difference GEE models. The RORs captured the changes on primary and secondary outcomes from the pre-exposure period (2019) to the exposure period (2020) between high and low-or-no, high and moderate, and finally moderate and low-or-no exposure groups for each semester (first Jan–June and second July–Dec). A ROR greater than one indicated an increased in-hospital mortality risk for patients in the given exposure group in comparison to the exposure reference. The between semester RRORs captured the learning effect between the second and the first semesters for each of the previous comparisons. A RROR less than one indicated a decreased risk of mortality for the second semester of the year in comparison to the first. C-statistics obtained from models were 0.91 for mortality, 0.95 for mortality inside ICU/IMCU and 0.89 for mortality outside ICU/IMCU

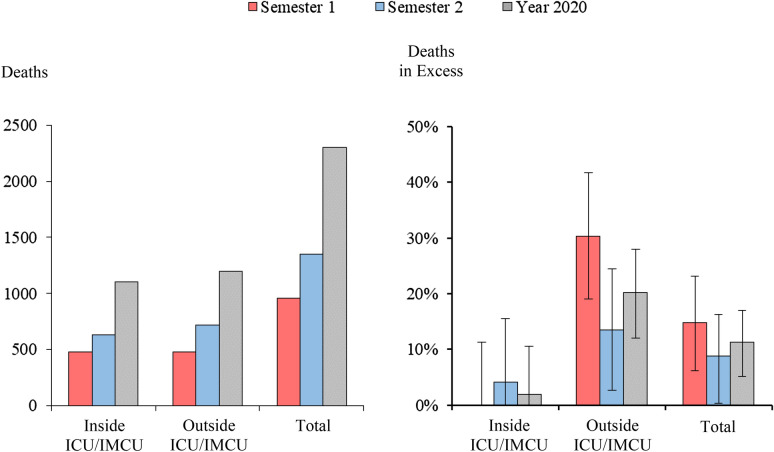

In 2020, 83,789 patients were operated in hospitals that experienced periods of moderate to high pandemic exposure. Among them, 2304 (2.7%) patients died, including 260 (95% CI 120–393) excess deaths, of which 242 (145–336) occurred outside the ICU/IMCU (Fig. 4 and ESM 1, sTable 2). Overall death in excess accounted for 11.3% (95% CI 5.2–17%) of mortality, including 1.9% (− 8.2–10.5%) inside and 20.2% (12.1–28%) outside of the ICU/IMCU. Excess mortality outside of the ICU/IMCU reached 15.2% (6.7–24.4%) and 42.1% (26.4–59.2%) in the case of moderate to high hospital exposure to the pandemic. The number of patient deaths was greater outside than inside the ICU/IMCU during periods of high COVID-19 exposure. Patients who died inside the ICU/IMCU tended to be less frail and undergo more risky surgical procedures (ESM 1, sTable 3 and sFigure 5).

Fig. 4.

Deaths in excess among surgical patients in moderate to high pandemic exposure groups. ICU/IMCUs were defined as intensive or intermediate care units. Excess in-hospital deaths for moderate- and high-exposure groups were calculated in comparison to the low-or-no exposure group. They were calculated separately and subsequently summed up. Using the RORs (ratios of odds-ratios) obtained from the triple-difference GEE models, we calculated the etiologic fraction, i.e., the share of deaths that would have been avoided if the exposure was low-or-no, and multiplied this value by the observed number of deaths in 2020. The corresponding 95% CIs were computed from non-parametric bootstrap based on 1000 replications

Discussion

Main findings

This nationwide study reports collateral damage of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical patient safety. We observed significantly increased mortality among non-COVID-19 patients who underwent surgery in hospitals concomitantly exposed to COVID-19 cases in their ICU/IMCU. Excess mortality following surgery essentially resulted from deaths outside of the ICU/IMCU. Furthermore, a learning effect occurred within hospital organizations between two successive semesters of pandemic waves.

Comparison with other studies

Worldwide, scientists broadly investigated how COVID-19 and the resulting pandemic response affected surgical patient outcomes [21]. Poor access to surgery and delays caused by massive cancelations of procedures may have led to more advanced disease and worse long-term postoperative prognosis [7, 22, 23]. Other studies showed that patients who underwent surgery with underlying SARS-CoV2 infection presented a higher death risk related to postoperative pulmonary complications [5, 24, 25]. Our findings shed further light on the indirect impacts of the pandemic by focusing on non-COVID-19 surgical patients. These findings are consistent with prior studies revealing an increase in overall hospital mortality for non-COVID diseases during national lockdown periods [3], and for critically ill non-COVID-19 patients admitted to ICUs experiencing high rates of critical cases of COVID [15, 26]. In the particular context of emergency and trauma surgery, higher mortality or failure to rescue also coincided with the peak months of the first wave [8, 9, 12, 27, 28]. Our study corroborates and goes beyond these results because it encompassed a much larger population of both elective and emergency surgeries, and considered pandemic exposure within every hospital countrywide throughout 2020. In addition to using 2019 as a simple historical control, the triple-difference design enabled us to better control for potential confounders and evaluate the learning effect. Glance et al. used a similar approach to demonstrate that the first wave of COVID-19 was associated with an elevated risk of postoperative mortality, but their analysis did not consider daily variations in each hospital’s exposure to the pandemic or distinguish between deaths inside or outside of the ICU/IMCU [29].

Strengths and limitations

This study is based on an exhaustive inpatient sample of surgical care provided in all facilities nationwide. Triple-difference design with distinct control groups allowed us to test both the influence of pandemic exposure on surgical mortality and the existence of a learning effect. By comparing mortality changes between group exposures among patients who were operated within the same hospital at the same period from 1 year to the other, we intended to control for differences in case mix and surgical outcomes that may exist across hospitals. Adding the semester into the analyses allowed us to assess improvements in managing surgical patients between the two waves of COVID-19 cases at the hospital. The absence of available vaccination or effective treatment against SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 also offered the opportunity to investigate hospital resilience over time in homogeneous pandemic response context.

This study has limitations. First, it relied on analyzing large hospital databases not initially introduced for evaluating surgical safety. Since this information is critical for billing purposes, surgical procedures, intensive care stays, and inpatient deaths are accurately collected in hospital claims databases. However, we were not able to consider deaths occurring outside the hospital setting, which may have led to underestimated mortality risk [30]. In addition, owing to some inaccuracies inherent to the medico-administrative data, we cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured confounders influenced our findings, as in any observational analysis. Our analysis may not have sufficiently controlled for the increased severity of hospitalized patients during periods of high pandemic exposure. Second, we assume that national COVID-19 directives were applied across all hospitals in France throughout 2020 with systematic perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection screening for every operated patient [10, 11, 31]. However, as rigorous monitoring systems for the directives were not implemented in every hospital, non-exhaustive identification of patients infected with COVID-19 could partially explain the observed excess mortality and learning effect. Third, it is potentially misleading to attribute the inpatient death outside of the ICU/IMCU uniquely to flaws in critical care access. Failure to rescue ideally requires the measurement of death following complications [32] and systematic ICU admission does not necessarily reduce death after surgery [33, 34]. Apart from restricted ICU/IMCU access, pandemic exposure may also translate a broader degradation of the hospital-wide surgical quality that incorporates all aspects of perioperative care continuity, including changes in operated patient allocation or shortage of personnel. Fourth, our results may not offer generalizability abroad. Pandemic consequences on surgical outcomes in each country probably depend on the intensity of the COVID-19 waves they were exposed to. The great heterogeneity existing across healthcare organizations worldwide and their available resources may also determine hospital resilience capacity.

Policy implications

As vividly highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, ICU/IMCU beds and staff are resources of utmost importance that guide national healthcare policies. Unanticipated creation of additional ICU/IMCU capacities to manage the massive influx of COVID-19 cases was a core challenge during the first year of the pandemic [35]. The reshaping of surgical wards to boost the critical capacity, transforming postoperative recovery rooms and classical care units to manage patients with COVID-19, disrupted standard perioperative pathways [10]. The fact that surgical outcomes deteriorated suggests that the hospital organizations lacked resiliency, even though we observed notable improvements from one semester to the other [36]. Stressful work conditions caused by staffing shortages, overwork and reallocation from operating rooms to ICU/IMCUs, may have compromised the wellbeing of health professionals and their routine safety practices [37–41]. To mitigate the heterogeneous burden of the pandemic between facilities over time, health authorities organized inter-hospital transfers of critically ill COVID-19 patients [42]. Since ICU/IMCU beds and available staff were reallocated to prioritize COVID-19 cases, the remaining capacities dedicated to non-COVID-19 surgical patients were insufficient.

A major assumption of our study is that if patients were admitted to the ICU/IMCU, their death could potentially have been avoided. A plausible reason for the higher risk of death outside of the ICU/IMCU could be that admission into ICU/IMCU was restricted, and access was primarily given to the surgical patients who were most likely to survive and benefit from these resources [43]. There are limits to high occupancy rates that can be safely achieved without considerable risk to patients. To avoid bed crises, maintaining spare capacity with some empty, but staffed, beds is a cost that must be incurred if safe care is to be sustained [44]. Considering that hospitals aim to maintain standard care during pandemic surges [45], a reserve system could protect a hospital’s ability to deliver safe surgery [46]. Compared to France, other countries have higher ICU/IMCU reserve capacities [47]. The provision of additional ICU/IMCU capacity could help hospitals provide better care to surgical and non-surgical patients, including those with COVID-19. Customized process simulation can also support decision-making to anticipate temporary ICU capacity expansion [48].

Conclusions

Surgical death risk increased among hospitals whose ICU/IMCUs experienced high exposure to COVID-19. The majority of excess in-hospital mortality occurred outside of the ICU/IMCU, suggesting that patients’ access to ICU/IMCUs following surgery could have been limited. Our findings call for reserving sufficient postoperative ICU/IMCU capacities in anticipation of future public health emergencies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the following people for their helpful contribution to the study: Pascal Auquier, Karine Baumstarck, Violaine Fernandez, Guillaume Fond, Veronica Orléans, Léa Pascal, Vanessa Pauly, Cécile Payet, Sarah Skinner, and Marie Viprey.

Author contributions

AD and LB contributed to obtaining funding and supervising study. AD, LB, and QC contributed to study conception and design. AD, CC, JCL, LB, MJC, QC, SP, and TR contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. AD, QC, and SP had full access to the data and directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. AD and SP contributed to data management. AD and QC contributed to statistical analysis. AD, QC, and SP contributed to manuscript drafting. AD, CC, JCL, LB, MJC, QC, SP, and TR contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AD and SP contributed to administrative, technical, or material support. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. AD had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AD is the guarantor, had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication and attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health (Programme de Recherche Appliquée sur le Coronavirus COVID-19). The funder of the study had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This observational study was based on retrospective analysis of anonymous data. The protocol was approved by the National Data Protection Commission (CNIL, N°F20210401171145) and recorded on the Health Data Hub French national registry prior any data management and analysis (available at: https://www.health-data-hub.fr/projets/consequences-de-la-pandemie-covid-19-sur-lacces-et-la-securite-des-soins-hospitaliers).

Data sharing statement

Anonymized participant data extracted from the nationwide hospital data warehouse are available from the ATIH Institutional Data Access Platform for researchers who meet the legal and ethical criteria for access to confidential data by the French national commission governing the application of data privacy laws. To obtain this dataset for an international researcher, please see the procedure at https://www.atih.sante.fr/bases-de-donnees/commande-de-bases (email: demande_base@atih.sante.fr). All materials, including the study protocol and statistical analysis plan, are freely available.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–21. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1513–1536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02796-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ, et al. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ. 2021;373:n1137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodilsen J, Nielsen PB, Søgaard M, et al. Hospital admission and mortality rates for non-covid diseases in Denmark during COVID-19 pandemic: nationwide population based cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rimmelé T, Pascal L, Polazzi S, Duclos A. Organizational aspects of care associated with mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(1):119–121. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06249-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.COVIDSurg Collaborative Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396(10243):27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kibbe MR. Surgery and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1151–1152. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose L, Mattingly AS, Morris AM, Trickey AW, Ding Q, Wren SM. Surgical procedures in veterans affairs hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2021;273(4):e129–131. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winter Beatty J, Clarke JM, Sounderajah V, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency adult surgical patients and surgical services: an international multi-center cohort study and department survey. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):904–912. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osorio J, Madrazo Z, Videla S, et al. Analysis of outcomes of emergency general and gastrointestinal surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2021;108(12):1438–1447. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020;107(10):1250–1261. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.COVIDSurg Collaborative Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107(9):1097–1103. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driessen MLS, Sturms LM, Bloemers FW, et al. The detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on major trauma outcomes in the Netherlands: a comprehensive nationwide study. Ann Surg. 2022;275(2):252–258. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton M, Nikolova S, Boaden R, Lester H, McDonald R, Roland M. Reduced mortality with hospital pay for performance in England. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1114951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.République française (2022) Indicateurs de suivi de l’épidémie de COVID-19 [data.gouv.fr]. https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/indicateurs-de-suivi-de-lepidemie-de-covid-19/#description. Accessed 20 Nov 2022.

- 15.Payet C, Polazzi S, Rimmelé T, Duclos A. Mortality among non-coronavirus disease 2019 critically Ill patients attributable to the pandemic in France. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(1):138–143. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haviari S, Chollet F, Polazzi S, et al. Effect of data validation audit on hospital mortality ranking and pay for performance. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(6):459–467. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert T, Cordier Q, Polazzi S, et al. External validation of the hospital frailty risk score in France. Age Ageing. 2022;51(1):afab126. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC. Absolute risk reductions, relative risks, relative risk reductions, and numbers needed to treat can be obtained from a logistic regression model. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):962–970. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patzer RE, Fayanju OM, Kelz RR. Using health services research to address the unique challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(10):903–904. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aubert O, Yoo D, Zielinski D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide organ transplantation: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(10):e709–719. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fotopoulou C, Khan T, Bracinik J, et al. Outcomes of gynecologic cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international, multicenter, prospective CovidSurg-Gynecologic Oncology Cancer study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(5):735.e1–735.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doglietto F, Vezzoli M, Gheza F, et al. Factors associated with surgical mortality and complications among patients with and without coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):691–702. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.COVIDSurg Collaborative Outcomes and their state-level variation in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection in the USA: a prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2022;275(2):247–251. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zampieri FG, Bastos LSL, Soares M, Salluh JI, Bozza FA. The association of the COVID-19 pandemic and short-term outcomes of non-COVID-19 critically ill patients: an observational cohort study in Brazilian ICUs. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(12):1440–1449. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06528-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchings A, Moonesinghe R, Moler Zapata S, et al. Impact of the first wave of COVID-19 on outcomes following emergency admissions for common acute surgical conditions: analysis of a national database in England. Br J Surg. 2022;109(10):984–994. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znac233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boukebous B, Maillot C, Neouze A, et al. Excess mortality after hip fracture during COVID-19 pandemic: more about disruption, less about virulence-Lesson from a trauma center. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glance LG, Dick AW, Shippey E, et al. Association between the COVID-19 pandemic and insurance-based disparities in mortality after major surgery among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2222360. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dony P, Pirson M, Boogaerts JG. In- and out-hospital mortality rate in surgical patients. Acta Chir Belg. 2018;118(1):21–26. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2017.1353236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention (2020) Dans les établissements de santé : recommandations COVID-19 et prise en charge. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-infectieuses/coronavirus/professionnels-de-sante/article/dans-les-etablissements-de-sante-recommandations-covid-19-et-prise-en-charge. Accessed 3 Jan 2023.

- 32.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care. 1992;30(7):615–629. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahan BC, Koulenti D, Arvaniti K, et al. Critical care admission following elective surgery was not associated with survival benefit: prospective analysis of data from 27 countries. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(7):971–979. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wunsch H, Gershengorn HB, Cooke CR, et al. Use of intensive care services for medicare beneficiaries undergoing major surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(4):899–907. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taccone FS, Van Goethem N, De Pauw R, et al. The role of organizational characteristics on the outcome of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU in Belgium. Lancet Region Health. 2021;2:100019. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleisher LA, Schreiber M, Cardo D, Srinivasan A. Health Care safety during the pandemic and beyond—building a system that ensures resilience. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):609–611. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2118285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duclos A, Payet C, Baboi L, et al. Nurse-to-nurse familiarity and mortality in the critically ill. A multicenter observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202204-0696OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez R, Lord H, Halcomb E, et al. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111:103637. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Abbasi S, Mardani A, Maleki M, Vlaisavljevic Z. Experiences of intensive care unit nurses working with COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1034624. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1034624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burns KEA, Moss M, Lorens E, et al. Wellness and coping of physicians who worked in ICUs during the pandemic: a multicenter cross-sectional North American Survey. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(12):1689–1700. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruyneel A, Smith P, Tack J, Pirson M. Prevalence of burnout risk and factors associated with burnout risk among ICU nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in French speaking Belgium. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65:103059. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turc J, Dupré HL, Beaussac M, et al. Collective aeromedical transport of COVID-19 critically ill patients in Europe: a retrospective study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40(1):100786. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aziz S, Arabi YM, Alhazzani W, et al. Managing ICU surge during the COVID-19 crisis: rapid guidelines. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1303–1325. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bagust A, Place M, Posnett JW. Dynamics of bed use in accommodating emergency admissions: stochastic simulation model. BMJ. 1999;319(7203):155–158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher D, Teo YY, Nabarro D. Assessing national performance in response to COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;396(10252):653–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31601-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Persad G, Pathak PA, Sönmez T, Ünver MU. Fair access to scarce medical capacity for non-covid-19 patients: a role for reserves. BMJ. 2022;376:o276. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2021) Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators [OECD Publishing, Paris]. 10.1787/ae3016b9-en. Accessed 3 Jan 2023

- 48.Alban A, Chick SE, Dongelmans DA, Vlaar APJ, Sent D, Study Group ICU capacity management during the COVID-19 pandemic using a process simulation. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1624–1626. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.