Abstract

Background

Inflammation plays an important role in the development of acute kidney injury (AKI). However, there are few studies exploring the prognostic influence of C-reactive protein to albumin ratio (CAR) among AKI patients. In this study, we investigated whether CAR could be a useful marker to predict the mortality of AKI.

Methods

A total of 358 AKI patients were extracted from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC III) database. C-reactive protein (CRP) and albumin were measured at ICU admission. The clinical outcome was 365-day mortality. Cox proportional hazards model and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were conducted to evaluate the association between CAR and outcome.

Results

Compared with patients in the survival group, nonsurvivors had higher CAR levels. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of CAR was higher than that of CRP and albumin for mortality (0.64 vs. 0.63, 0.59, respectively). The cut-off point of CAR for mortality was 7.23. In Cox proportional-hazard regression analysis, CAR (hazards ratio (HR) =2.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) =1.47-2.85, p < 0.001 for higher CAR) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (HR = 1.02, 95%CI = 1.00-1.03, p = 0.004) were independent predictors of 365-day mortality.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that a higher level of CAR was associated with 365-day mortality in AKI patients.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, Albumin, Acute kidney injury, Mortality

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and serious syndrome in hospitalized patients, referring to an abrupt decrease in glomerular filtration. It is well-know that diagnostic criteria of AKI are based on urine output reduction and serum creatinine rise [1]. The presence of AKI is associated with increased mortality in patients, especially in critical illness [2]. In addition, AKI patients often fail to complete recover renal function and need renal replacement therapy (RRT), which is costly and has a negative influence on patients’ quality of life [3, 4]. Given the high incidence of AKI and its poor outcomes in critical illness, an increasing number of observational studies have been devoted to seeking for reliable predictors of mortality in AKI [5].

The mechanisms of AKI are characterized by inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic alterations and tubular injury. Recently, several studies have suggested that inflammation played an important role in the pathogenesis of AKI [6–8]. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute-phase protein, markedly increases within hours after inflammation. It could be a useful monitor for inflammatory disease due to the relatively short half-life of approximately 19 hours [9]. Meanwhile, serum albumin has been considered to be a negative acute phase protein in inflammation and associated with AKI development [10, 11]. By merging CRP and albumin into a single index, the CRP to albumin ratio (CAR) is an easily available marker and has been considered to be related to increased risk of AKI in patients after cardiovascular surgery [10]. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that increased CAR was associated with mortalities in a variety of diseases, including cancer, ischemic stroke, liver failure and infection [12–14]. Therefore, we hypothesized that CAR could predict the outcome of AKI patients. However, it is surprised that little study has examined the relationship between mortality and CAR in AKI patients. In our present study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of CAR for mortality in AKI patients.

Methods

Study subjects

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC III) database (version 1.4) is a large, single-center database comprising information of patients admitted to critical care units at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston between 2001 and 2012 [15]. The establishment of this database was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). This database contains detailed information of distinct patients including demographic characteristics, laboratory data, therapeutic interventions, survival data and more [15, 16]. After completing a training course on the website of National Institutes of Health named ‘Protecting Human Research Participants’, one author was permission to access the database for research purposes (Certification number: 27454094).

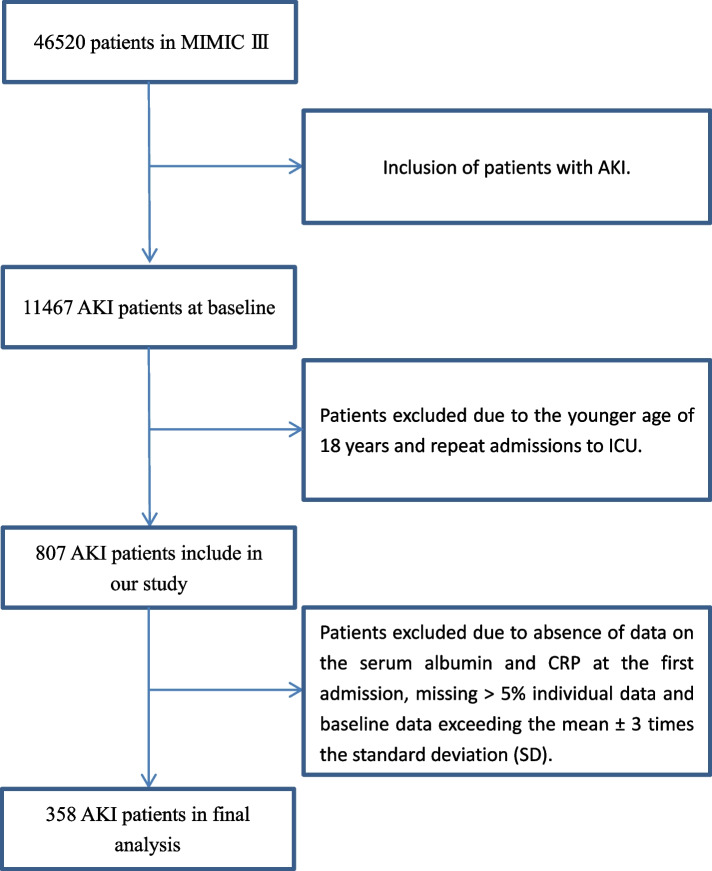

In this study, we collected 358 consecutive patients with AKI admitted to ICU. Eligible patients met the following inclusion criteria: age 18 years or older at first admission and the primary diagnosis was AKI. The exclusion criteria were: absence of data on the serum albumin and CRP at the first admission, missing > 5% individual data and baseline data exceeding the mean ± 3 times the standard deviation (SD) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of inclusion and exclusion procedure

Data extraction

All data were extracted from MIMIC III using the Structured Query Language (SQL) with PostgreSQL tools (version 12.0). The data contained clinical parameters, laboratory parameters, comorbidities, and scoring systems. The clinical parameters included age, gender, heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), percutaneous oxygen saturation (SPO2), vasopressin used and RRT. The following laboratory parameters were extracted: CRP, albumin, chloride, anion gap, bicarbonate, lactate, creatinine, potassium, sodium, platelet, glucose and white blood cell (WBC). The comorbidities included the congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease and malignancy. We also calculated sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II). The outcome of our study was 365-day mortality.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables were presented as the mean ± SD and percentage, respectively. One-way ANOVA, X2 test, and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare differences between the clinical characteristics of survivors and nonsurvivors as appropriate. We used One-way ANOVA or Mann-Whitney U test to explore CRP between low and normal albumin group. When results were significant, we added the possible confounders to the Cox regression model to examine the relationship between CAR and outcome. The results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Furthermore, survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimates and comparisons were constructed based on the log-rank test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were performed to evaluate the ability of CAR, CPR and albumin to predict mortality in AKI patients. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant in all tests.

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 358 eligible participants collected from the MIMIC III database were enrolled into our study. The mean age of participants was 69.43 ± 13.70 years, of which 210 (60.9%) participants were male. The 365-day mortality was 69.6% (n = 250); these patients were defined as nonsurvivors. The characteristics of survivors and nonsurvivors are presented in Table 1. Compared with survivors, patients were more likely to be elderly, male and had higher CRP, CAR and SAPS II score, whereas systolic blood pressure was lower in nonsurvival group (all P<0.05). There were no significant differences in age and other parameters. Moreover, we divided patients into two groups according to the albumin level. There was no significant difference in CRP between low and normal albumin group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Characteristics | Survivors (n = 108) | Nonsurvivors (n = 250) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Age (years) | 67.26 ± 14.43 | 70.37 ± 13.28 | 0.048 |

| Gender (male) [n(%)] | 57 (52.80) | 161 (64.40) | 0.039 |

| Heart rate (mean ± SD) | 87.63 ± 13.64 | 88.74 ± 18.33 | 0.571 |

| Respiratory rate (mean ± SD) | 19.82 ± 4.87 | 20.11 ± 4.54 | 0.588 |

| SBP(mean ± SD)(mmHg) | 116.17 ± 21.07 | 111.83 ± 18.05 | 0.049 |

| DBP(mean ± SD)(mmHg) | 56.28 ± 11.88 | 57.50 ± 11.57 | 0.366 |

| MAP(mean ± SD)(mmHg) | 75.01 ± 13.62 | 73.61 ± 12.53 | 0.348 |

| SPO2 (%) | 97.03 ± 2.02 | 96.78 ± 2.94 | 0.420 |

| Vasopressin used [n(%)] | 56 (51.90) | 158 (63.20) | 0.044 |

| RRT used [n(%)] | 6 (5.60) | 26 (10.40) | 0.140 |

| Laboratory parameters (mean ± SD) | |||

| Lactate (mg/dl) | 2.70 ± 1.91 | 2.91 ± 2.01 | 0.396 |

| Glucose (md/dl) | 156.65 ± 72.61 | 154.53 ± 70.10 | 0.796 |

| White blood cell (109/l) | 15.58 ± 14.76 | 14.13 ± 9.89 | 0.280 |

| Platelet (109/l) | 228.41 ± 111.73 | 229.68 ± 138.27 | 0.933 |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 138.27 ± 6.13 | 138.16 ± 6.50 | 0.882 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 4.35 ± 0.74 | 4.35 ± 0.69 | 0.981 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | 21.95 ± 5.08 | 22.14 ± 4.98 | 0.752 |

| Chloride (mmol/l) | 105.02 ± 7.89 | 104.56 ± 7.59 | 0.603 |

| Anion gap (mmol/l) | 15.72 ± 3.55 | 15.95 ± 3.81 | 0.586 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.07 ± 1.45 | 1.97 ± 1.20 | 0.504 |

| C-Reactive protein(mg/dl) | 72.54 ± 79.13 | 99.61 ± 83.44 | 0.004 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.07 ± 0.62 | 2.85 ± 0.58 | 0.001 |

| CAR | 25.05 ± 27.47 | 36.50 ± 31.96 | 0.001 |

| Clinical scores (mean ± SD) | |||

| SOFA | 5.69 ± 2.83 | 6.34 ± 3.62 | 0.097 |

| GCS | 13.62 ± 2.47 | 13.45 ± 2.61 | 0.561 |

| SAPS II | 42.48 ± 11.61 | 46.37 ± 14.40 | 0.014 |

| Comorbidity [n(%)] | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 40 (37.00) | 110 (44.00) | 0.220 |

| Hypertension | 29 (26.90) | 56 (22.40) | 0.364 |

| Diabetes | 48 (44.40) | 98 (39.20) | 0.354 |

| Stroke | 3 (2.80) | 17 (6.80) | 0.128 |

| Chronic renal disease | 33 (30.60) | 75 (30.00) | 0.916 |

| Chronic liver disease | 11 (10.20) | 29 (11.60) | 0.697 |

| Malignancy | 6 (5.60) | 30 (12.00) | 0.063 |

CAR C-Reactive protein/albumin, DBP diastolic blood pressure, MAP mean arterial pressure, RRT renal replacement therapy, SPO2 percutaneous oxygen saturation, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score II, SBP systolic blood pressure, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale

Association between CAR and mortality

Using ROC curves, the optimal CAR cut-off point was 7.23 at admission for predicting 365-day mortality, with high sensitivity and modest specificity [82.0 and 43.5%, respectively; area under the curve (AUC) = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.57-0.70; P<0.001]. CAR had a higher prognostic accuracy for 365-day mortality compared to CRP [AUC 0.63 (0.56-0.69), P<0.001] and Albumin [AUC 0.59 (0.52-0.66), p = 0.007] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for different models to predict 365-day mortality

Using Cox proportional hazard model, we analyzed the influence of age, gender, SBP, Vasopressin used, SAPS II score and CAR on 365-day mortality (Table 2). Patients were divided into two groups according to CAR for survival analysis. The relative risk for mortality was significantly related to CAR (HR =2.04, 95% CI = 1.47-2.85, P<0.001 for high CAR) and SAPS II score (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00-1.03, P = 0.004). These results suggested that CAR>7.23 had a strong ability to predict 365-day mortality.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for mortality

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 0.278 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.40 | 1.07-1.82 | 0.014 |

| SBP | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.698 |

| Vasopressin used | 1.20 | 0.90-1.60 | 0.210 |

| SAPS II | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 | 0.004 |

| CAR≤7.23 | Reference | ||

| CAR>7.23 | 2.04 | 1.47-2.85 | <0.001 |

CAR C-Reactive protein/albumin, SBP systolic blood pressure, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

Discussion

In our study, we explored the possible association between CAR and mortality in AKI patients. The main finding of our study was that CAR could predict mortality in AKI patients admitted to the ICU. In addition, we found that the higher level of CAR was positively associated with increased risk of 365-day mortality.

The CAR is a combination of CRP and albumin that has been proposed as an inflammation-based prognostic score in diseases and has a potential ability of predicting the prognostic outcome of patients. For example, Park et al. considered that CAR was correlated with high mortality in medical intensive care unit patients [17], which was in line with our results. Another study performed by Ren et al. reported that an increased CAR was closely associated with mortality risk in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [18]. In addition, Kocaturk et al. suggested that acute ischemic stroke patients with a higher CAR had a lower survival probability [14]. A study conducted by Wang et al. showed that a higher CAR was positively correlated with 30-day mortality in patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis [13]. Finally, Llop-Talaveron et al. showed that a high CAR was positively associated with more complications during parenteral nutrition treatment [12]. Taken together, these studies suggested that CAR may be a potentially useful prognostic tool for predicting outcome in patients.

The mechanism of relationship between CAR and mortality in AKI patients may be explained by the inflammation reaction. It has been described that ischemia reperfusion injury and inflammation played important roles in AKI development [6–8, 19]. Ischemic injury to kidney can promote the activation of endothelial renal cells that express adhesion molecules, resulting in inflammatory response [20]. CRP, a marker of inflammation, has been considered to be associated with activated coagulation and platelet system, which may reduce renal blood flow and oxygen delivery to the kidneys [21, 22]. CRP also could mediate the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and decreased nitric oxide production [23]. The elevated CRP may cause endothelium dysfunction and alter the vascular equilibrium to vasoconstrictive, proinflammatory and prothrombotic status [24]. Serum albumin is considered a vital protective antioxidant and abundant circulating protein in plasma [25]. The decrease in the serum albumin level may aggravate the renal dysfunction due to oxidative stress damage [26]. Meanwhile, inflammation may reduce albumin concentration by decreasing its synthesis rate. Therefore, the CRP is positively associated with the inflammatory response, and albumin is negatively related to inflammation, resulting in higher CAR. Recently, a cohort study suggested that severe inflammation with increased plasma proinflammatory cytokine could predict mortality in AKI patients [27]. Meanwhile, Doi et al. suggested that the mortality of AKI patients could decrease by using anti-inflammatory cytokines [28]. Taken together, the relationship between CAR and mortality may be associated to the involvement of inflammation.

There are some limitations in our study. First, we only measured CRP and albumin in patients admitted to the ICU once and did not evaluate changes during treatment, which may have a biased influence on the results. Second, the inherent biases of analysis were present in our research because of retrospective study. Third, we did not know the state of nutrition of patients before admitting to the ICU, which may lead to deviation with the actual situation. Fourth, several important data, including insurance status, income and education which may be related to mortality were missing. Fifth, in our study, the dataset between 2001 and 2012 used may have a biased influence on the results. Hence, further studies should be conducted to clarify the relationship between CAR and mortality in AKI patients using newest data. Finally, there was a potential selection bias existing due to our study of patients exclusively collected from a single center, which may limit the generalization of our findings.

Conclusion

In summary, our study suggested that a higher level of CAR was related to increased risk of 365-day mortality in AKI patients. Our findings need to be confirmed by further prospective studies.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

BL and DL conceived of the study, supervised the statistical analyses and prepared manuscript. DL had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for integrity of the data. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The establishment of this database was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dezhao lv was permission to access the database for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care (London, England) 2007;11(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lameire NH, Bagga A, Cruz D, De Maeseneer J, Endre Z, Kellum JA, et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet (London, England) 2013;382(9887):170–179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiffl H, Fischer R. Five-year outcomes of severe acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(7):2235–2241. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365–3370. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng CF, Liu WY, Zeng FF, Zheng MH, Shi HY, Zhou Y, et al. Prognostic value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Crit Care (London, England) 2017;21(1):238. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega-Hernandez J, Springall R, Sanchez-Munoz F, Arana-Martinez JC, Gonzalez-Pacheco H, Bojalil R. Acute coronary syndrome and acute kidney injury: role of inflammation in worsening renal function. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):202. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0640-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dirkes S. Sepsis and inflammation: impact on acute kidney injury. Nephrol Nurs J. 2013;40(2):125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu C, Sheng Y, Qian Z. Current understanding of inflammatory responses in acute kidney injury. Curr Gene Ther. 2017;17(6):405–410. doi: 10.2174/1566523218666180214092219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Q, Zhou Y, Xu Z, Yang Y, Kuang D, You H, et al. The ratio of CRP to prealbumin levels predict mortality in patients with hospital-acquired acute kidney injury. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karabag Y, Cagdas M, Rencuzogullari I, Karakoyun S, Artac I, Ilis D, et al. The C-reactive protein to albumin ratio predicts acute kidney injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Lung Circul. 2019;28(11):1638–45. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiedermann CJ, Wiedermann W, Joannidis M. Hypoalbuminemia and acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of observational clinical studies. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(10):1657–1665. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1928-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llop-Talaveron J, Badia-Tahull MB, Leiva-Badosa E. An inflammation-based prognostic score, the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts the morbidity and mortality of patients on parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2018;37(5):1575–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CJ, Wu JP, Zhou WQ, Mao WL, Huang HB. The C-reactive protein/albumin ratio as a predictor of mortality in patients with HBV-related decompensated cirrhosis. Clin Lab. 2019;65(8):1531–37. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.190215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocaturk M, Kocaturk O. Assessment of relationship between C-reactive protein to albumin ratio and 90-day mortality in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2019;53(3):205–211. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2019.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson AE, Pollard TJ, Shen L, Lehman LW, Feng M, Ghassemi M, et al. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Scientific Data. 2016;3:160035. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saeed M, Villarroel M, Reisner AT, Clifford G, Lehman LW, Moody G, et al. Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care II: a public-access intensive care unit database. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(5):952–960. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a92c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JE, Chung KS, Song JH, Kim SY, Kim EY, Jung JY, et al. The C-reactive protein/albumin ratio as a predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. J Clin Med. 2018;7(10):333. doi: 10.3390/jcm7100333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren Y, Fan X, Chen G, Zhou D, Lin H, Cai X. Preoperative C-reactive protein/albumin ratio to predict mortality and recurrence of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Med Clin. 2019;153(5):183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonventre JV, Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: an inflammatory disease? Kidney Int. 2004;66(2):480–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molitoris BA, Sandoval R, Sutton TA. Endothelial injury and dysfunction in ischemic acute renal failure. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5 Suppl):S235–S240. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bisoendial RJ, Kastelein JJ, Levels JH, Zwaginga JJ, van den Bogaard B, Reitsma PH, et al. Activation of inflammation and coagulation after infusion of C-reactive protein in humans. Circ Res. 2005;96(7):714–716. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163015.67711.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liss P, Nygren A, Olsson U, Ulfendahl HR, Erikson U. Effects of contrast media and mannitol on renal medullary blood flow and red cell aggregation in the rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1996;49(5):1268–1275. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feinbloom D, Bauer KA. Assessment of hemostatic risk factors in predicting arterial thrombotic events. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(10):2043–2053. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000181762.31694.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CD, Emeis JJ, Coppack SW. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: a potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(4):972–978. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu ML, Louie S, Cross CE, Motchnik P, Halliwell B. Antioxidant protection against hypochlorous acid in human plasma. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;121(2):257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawai Y, Masutani K, Torisu K, Katafuchi R, Tanaka S, Tsuchimoto A, et al. Association between serum albumin level and incidence of end-stage renal disease in patients with immunoglobulin a nephropathy: a possible role of albumin as an antioxidant agent. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmons EM, Himmelfarb J, Sezer MT, Chertow GM, Mehta RL, Paganini EP, et al. Plasma cytokine levels predict mortality in patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2004;65(4):1357–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doi K, Hu X, Yuen PS, Leelahavanichkul A, Yasuda H, Kim SM, et al. AP214, an analogue of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, ameliorates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury and mortality. Kidney Int. 2008;73(11):1266–1274. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.