Abstract

Erv14p is a conserved integral membrane protein that traffics in COPII-coated vesicles and localizes to the early secretory pathway in yeast. Deletion of ERV14 causes a defect in polarized growth because Axl2p, a transmembrane secretory protein, accumulates in the endoplasmic reticulum and is not delivered to its site of function on the cell surface. Herein, we show that Erv14p is required for selection of Axl2p into COPII vesicles and for efficient formation of these vesicles. Erv14p binds to subunits of the COPII coat and binding depends on conserved residues in a cytoplasmically exposed loop domain of Erv14p. When mutations are introduced into this loop, an Erv14p-Axl2p complex accumulates in the endoplasmic reticulum, suggesting that Erv14p links Axl2p to the COPII coat. Based on these results and further genetic experiments, we propose Erv14p coordinates COPII vesicle formation with incorporation of specific secretory cargo.

INTRODUCTION

Intracellular transport pathways between organelles of the early secretory pathway depend on coat protein complexes that deform membranes and collect specific cargo molecules. Activated small GTPases are thought to attract coat proteins to specific membrane export sites and physically link coats to export cargo. As coats polymerize, vesicles form and are budded from membrane-bound organelles (reviewed in Springer et al., 1999). Although vesicle coats and coat recognition motifs have been identified for some transmembrane cargo (Cosson and Letourneur, 1994; Nishimura and Balch, 1997), many trafficking proteins do not contain known motifs and the molecular mechanisms underlying selective export are not understood.

Transport of newly synthesized secretory proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) depends on a coat complex termed COPII, which consists of the small GTPase Sar1p, the Sec23/24p complex, and the Sec13/31p complex (Barlowe et al., 1994). Morphological and biochemical experiments have demonstrated that certain secretory proteins are concentrated into ER-derived vesicles during transport from this compartment (Quinn et al., 1984; Salama et al., 1993; Balch et al., 1994; Bednarek et al., 1995). Furthermore, specific COPII–cargo complexes have been characterized that in many instances depend on the activated form of the Sar1p GTPase (Aridor et al., 1998; Kuehn et al., 1998; Springer et al., 1999). These results indicate that specific vesicle cargo is concentrated into ER-derived vesicles through direct or indirect interactions with COPII subunits. Additional evidence suggests that cargo receptors are required in some instances to link soluble secretory cargo to vesicle coats (Kuehn et al., 1998; Muniz et al., 2000). However, some soluble cargo does not appear to be concentrated during export from the ER and instead is concentrated during transport through other compartments of the early secretory pathway (Martinez-Menarguez et al., 1999). Clearly, the mechanisms that govern export of distinct secretory cargo from the ER remain to be elucidated. Toward this goal, we have identified a set of membrane-bound ER vesicle (Erv) proteins that bind to subunits of the COPII coat and function in protein transport between the ER and Golgi (Belden and Barlowe, 1996; Powers and Barlowe, 1998; Otte et al., 2001). In this report, we focus on Erv14p and dissect its function in COPII-dependent transport from the ER.

Yeast Erv14p was identified on COPII-coated vesicles and localizes to ER and Golgi membranes. Deletion of ERV14 produces viable cells that display a defect in bud site selection because a transmembrane secretory protein, Axl2p, is not delivered to the cell surface (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). Axl2p is required for selection of axial growth sites and normally localizes to nascent bud tips of the mother bud neck (Halme et al., 1996; Roemer et al., 1996). In erv14Δ strains, Axl2p accumulates in the ER, whereas other secretory proteins are transported at near wild-type rates. Based on these findings, we proposed that Erv14p cycled between the ER and Golgi compartments and served a role in export of secretory cargo from the ER (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). Erv14p is highly conserved and in Drosophila melanogaster the homologous protein, known as Cornichon, is essential for polarity establishment during the early stages of oogenesis (Roth et al., 1995). Indeed, it has been proposed that cornichon operates similarly in ER export of a distinct secretory protein, the transforming growth factor α-like signaling molecule Gurken (Queenan et al., 1999). Thus, a mechanistic understanding of Erv14p function should contribute to a general understanding on sorting during export from the ER.

Herein, we demonstrate that Erv14p associates with both the COPII coat and the transmembrane secretory protein Axl2p. In addition, our data indicate that Erv14p acts in selecting Axl2p into COPII vesicles and for efficient formation of these vesicles. Previous reports have shown that integral membrane secretory proteins such as the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein and plasma membrane ATPase bind to subunits of the COPII coat (Aridor et al., 1998; Shimoni et al., 2000). However, there are no examples indicating that integral membrane secretory proteins depend on vesicle adaptors for export from the ER. Therefore, our findings may have important implications for transport of a variety of other integral membrane secretory cargo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and Growth Conditions

All yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cultures were grown at 30°C in either rich medium (1% Bacto-yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, and 2% dextrose) or minimal medium (0.67% nitrogen base without amino acids and 2% dextrose) containing the appropriate supplements for plasmid selection (Sherman, 1991). Manipulations of recombinant DNA were performed in Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Ausubel et al., 1987). Thermosensitive sec mutants (Kaiser and Schekman, 1990) were mated to CBY356 or CBY358 and resulting diploids induced to sporulate. Tetrads were dissected and allowed to germinate on YPD plates at room temperature. An increase in thermosensitivity was more finely explored by growing identically struck YPD plates at 23, 28, 34, and 37°C. Temperature-sensitive sec mutants that displayed an enhanced thermosensitivity when combined with erv14Δ were backcrossed through the erv14Δ parent strain twice more to confirm that genetic interactions were specific and not due to variation in strain backgrounds.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CBY355 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δl lys2Δ202 trpl Δ63 | Powers and Barlowe, 1998 |

| CBY356 | MATα his3 Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 trp1 Δ63 erv14::HIS3 | Powers and Barlowe, 1998 |

| CBY409 | CBY356 containing pRS-ERV14HA | Powers and Barlowe, 1998 |

| CBY601 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 | This study |

| CBY602 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 erv14::HIS3 | This study |

| CBY603 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 erv14::HIS3 sec13-1 | This study |

| CBY604 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 sec 13-1 | This study |

| CBY615 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 sec 23-1 | This study |

| CBY616 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 | This study |

| CBY617 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 erv14::HIS3 sec23-1 | This study |

| CBY618 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 lys2Δ202 trp1Δ63 erv14::HIS3 | This study |

| CBY663 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 erv14::HIS3 sec16-2 | This study |

| CBY664 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 sec16-2 | This study |

| CBY665 | MATα his3Δ200 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 lys2Δ202 erv14::HIS3 | This study |

| CBY707 | CBY356 containing pRS316-ERV14-(V44)-HA | This study |

| CBY731 | CBY356 containing pRS316-ERV14-(L92)-HA | This study |

| CBY732 | CBY356 containing KS-ERV14-pro-α-factor-HA | This study |

| CBY800 | CBY356 with AXL2::13MYC | This study |

| CBY807 | CBY355 with AXL2::13MYC | This study |

| CBY808 | CBY356 containing KS-ERV14-(91-95A)-HA | This study |

| CBY809 | CBY356 containing KS-ERV14-(97-101A)-HA | This study |

| CBY812 | CBY800 containing pRS316 | This study |

| CBY813 | CBY800 containing pRS316-ERV14 -HA | This study |

| CBY816 | CBY800 containing KS-ERV14-(91-95A)-HA | This study |

| CBY817 | CBY800 containing KS-ERV14-(97-101A)-HA | This study |

| CBY866 | CBY800 containing pRS315-ERV14 | This study |

| CBY867 | CBY800 containing KS-ERV14-(Y80A)-HA | This study |

| CBY868 | CBY800 containing KS-ERV14-(D93A)-HA | This study |

Antibodies and Immunoblotting

Antibodies used in these studies against Bos1p (Cao and Barlowe, 2000), Emp47p, Erv25p, Kar2p, Sec12p, Sec61p, anti-hemagglutinin (HA), and anti-c-myc, have been described (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). Polyclonal antiserum specific for Erv14p was raised against the peptide LDATEIFRTLGKHKRESFLK, representing residues 92–111 of Erv14p. This peptide was linked to KLH and the peptide-carrier conjugate used for rabbit immunization (Quality Controlled Biochemicals, Hopkinton, MA). Protein samples were resolved either by SDS-PAGE or by Tris/tricine polyacrylamide gels (Schagger and von Jagow, 1987) and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). Peroxidase-catalyzed chemiluminescence was used to detect filter-bound antibodies (ECL method; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Scanning densitometry of immunoblots was performed using NIH Image. Calcofluor staining of bud scars (Pringle, 1991) and subcellular fractionation of membranes on sucrose density gradients were performed as described (Powers and Barlowe, 1998).

Plasmid Construction

Construction of Erv14p-fXa Fusion Proteins.

A double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding the factor Xa protease cleavage recognition site IEGR was created by annealing the complimentary oligonucleotides JP22 (5′-ATCGAGGGTAGA-3′) and JP23a (5′-TCTACCCTCGAT-3′). The annealed oligonucleotides were then inserted independently into each region of ERV14 predicted to encode loop domains. For the first loop, the oligonucleotide encoding the factor Xa recognition motif was inserted into a unique HpaI site at nucleotide 132 of ERV14 in pRS316-ERV14-HA (Powers and Barlowe, 1998), creating the plasmid pRS316-ERV14-(V44)-HA. For the second loop, site-directed mutagenesis was used to create a unique NruI site at nucleotide 276 in the plasmid pRS316-ERV14-HA. The CLONTECH Transformer Mutagenesis kit (Palo Alto, CA) was used for this construct and others that required site-directed mutagenesis. Oligonucleotide primers JP28 (5′-GGGGGGGCCC AGTACTCAGC TTTTGTTCC-3′) and JP30 (5′-GAATATTTCG GTAGCT-CGCG AAAGTTGAAC TTTATTGTAG-3′) were used for the selection mutation (changing the unique KpnI site in pRS316 to a ScaI site) and for the site-directed mutation, respectively. The oligonucleotide encoding the factor Xa recognition motif was then cloned into the new NruI site, creating the construct pRS316-ERV14-(L92)-HA. In both insertion constructs, proper integration and orientation of a single factor Xa protease cleavage site was confirmed by sequence analysis.

Construction of Erv14p-proα-factor-HA Fusion Protein.

Proα-factor was fused to the C terminus of Erv14p by using the MFα1 gene contained on plasmid pDJ100 (Hansen et al., 1986) as template in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers JP20 (5′-CGGGGTACCG CTCCAGTCAA CACTACAACA GAAG-3′) and JP21 (5′-GCCGGTACCG TACATTGGTT GGCCGGGTTT TAACTG-3′). JP20 annealed to the 5′ end of the MFα1 open reading frame after the codon for Ala 19. This eliminated the signal sequence or “pre” region of the MFα1 gene product. JP21 annealed directly 5′ to the stop codon of MFα1. Both of these primers included a KpnI site for cloning the amplified product into KS-ERV14-2NXT-HA. The resulting plasmid encoded full-length Erv14p with proα-factor fused to the carboxy terminus followed by the HA epitope and was referred to as KS-ERV14-proα-factor-HA.

Single Residue Change Mutants.

Single codon mutations (Y80A and D93A) were made by site-directed mutagenesis. Oligonucleotide JP28 was used as the selection primer in conjunction with JP31 (5′-GTAGATCTTG TTTAGATTGG CAGCTAGAAC TGGTAAGTT-3′), which was used to create a site-directed mutation converting a tyrosine residue to an alanine at position 80 of ERV14 in the plasmid pRS316-ERV14-HA, resulting in the plasmid KS-ERV14-(Y80A)-HA. Similarly, KS-ERV14-(D93A)-HA was constructed using oligonucleotides JP28 and JP33 (5′-TCTGAATAT TTCGGTAGCA GCCAAAAGTT GAACTTTATTG-3′) to convert the codon for aspartic acid 93 to an alanine.

Construction of Alanine Stretch Mutants.

The codons for amino acid residues 91 through 95 were mutated to encode alanines in pRS316-ERV14-HA by site-directed mutagenesis. Oligonucleotides JP28 and JP36 (5′-GCCTAAAGTT CTGAATATTT CGGCAGCTGC AGCAGCTTGA ACTTTATTGT AGATCTTG-3′) were used for selection mutation and for site-directed mutation, respectively. Similarly, the codons for amino acids 97–101 were converted to alanines by using JP28 with JP37 (5′-GGAAACTCTC CCTTTTATGT TTGCCTGCAG CTGCGGCTGC TTCGGTAGCA TCCAAAAGTT GAAC-3′). These plasmids were referred to as KS-ERV14(91-95A)-HA and KS-ERV14(97-101A)-HA. In all instances, constructs were subjected to DNA sequence analysis to confirm correct synthesis.

Strain Construction

Oligonucleotides JP34 (5′-GGTCAAGTTA AGGACATTCA CGGACGCATC CCAGAAATGC TGCGGATCCC CGGGTTAATT AA-3′) and JP35 (5′-ACAGGAAAAT AAAATTAAGC AAAAT-ATCGT TGCGTATAAG AATTCGAGCT CGTTTAAAC-3′) were used with plasmid template pFA6a-13Myc-TRP1 in a one-step PCR-mediated technique to C-terminally tag the chromosomal allele of AXL2 with 13 sequential c-myc epitopes (Longtine et al., 1998). One of the positive isolates (CBY800) was characterized and used for further studies. A similar procedure was used to introduce myc-tagged Axl2p in strain CBY355 to generate strain CBY807, except the template pFA6a-13Myc-His3MX6 was used.

COPII-dependent Transport and Binding Assays

Reconstituted assays to measure the budding and transport efficiency of [35S]glyco-proα-factor (gpαF) have been previously described (Barlowe, 1997). The data plotted in these experiments are the average of duplicate determinations and the error bars represent the range. To measure the efficiency of protein packaging into COPII vesicles, reconstituted vesicle synthesis reactions were performed from isolated microsomes as described (Barlowe et al., 1994). In Sar1-GST binding assays, ternary complexes were formed and isolated from microsomes after incubation with Sar1p-GST and Sec23/24p complex as described (Kuehn et al., 1998).

Factor Xa Cleavage of Erv14p-fXa Fusion Proteins

Factor Xa digests were performed on isolated microsomal membranes containing Erv14p-fXa-(V44)-HA or Erv14p-fXa-(L92)-HA (Nagai and Thørgersen, 1984). Microsomes (3 μg of total membrane protein) in 10 μl of factor Xa buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 250 mM sorbitol) were incubated with or without 0.2% NP-40 for 15 min on ice. Samples were then treated with or without 1 μg of factor Xa (Promega, Madison, WI) and incubated at 4°C for 18 h. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of tricine sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 3 min. Samples were resolved on 16.5% Tris/tricine gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblots were probed with the anti-HA antibody. For proteinase K digests, 10 μg of total membrane protein was treated with 3 μg of proteinase K in 25 μl of factor Xa buffer plus or minus 0.2% NP-40 for indicated times at 4°C.

Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) Digestion of Glycosylated Erv14p-proα-factor-HA

Microsomal membranes (200 μg of total membrane protein) were solubilized in 1% SDS, heated for 2 min at 95°C, and diluted with 1 ml of concavalin A (Con A) buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100). After a centrifugation at 14 K for 5 min, 1 ml was removed to a new tube and incubated with 30 μl of 20% Con A-Sepharose for 2 h at room temperature. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of Con A buffer then with 1 ml of IP buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100). After the final wash, the contents of the tube were aspirated to ∼20 μl and bound proteins were released from beads by the addition of an equal volume of 2% SDS/1% β-mercaptoethanol and heated at 95°C for 3 min. The pH was reduced by addition of 20 μl of 100 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.5. Samples were then incubated overnight at 37°C with or without 5 mU of endoglycosidase H (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). Reactions were terminated with 15 μl of 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heated for 3 min at 95°C. Total and Con A-precipitated samples were analyzed by immunoblot for Erv14p-proα-factor-HA and Sec12p.

Immunoprecipitation Experiments

For immunoprecipitation of Erv14p-HA, 50 μl of microsomes (160 μg of total membrane protein) was solubilized in an equal volume of 0.5% digitonin/buffer88-8 at 25°C for 10 min (Kuehn et al., 1998). After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to remove unsolubilized material, the supernatant fluid (100 μl) was transferred to a fresh tube. Solubilized material was diluted with 3 volumes of 0.5% digitonin/buffer88-8 and HA-tagged proteins immunoprecipitated by addition of 0.6 μg of anti-HA monoclonal antibody and 25 μl of 20% protein A-Sepharose beads. In extract mixing experiments, equal amounts of solubilized extracts were mixed before dilution. After binding for 60 min at 4°C, beads with bound protein were washed a total of three times with 0.5% digitonin/buffer88-8. Finally, the bound protein was released from beads by addition of 25 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 3 min. Complexes from one-half of the immunoprecipitates were resolved on polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted for Sec61p, Kar2p Erv14p-HA, or Axl2p-myc.

RESULTS

Erv14p Is Required for Incorporation of Axl2p into COPII-coated Vesicles

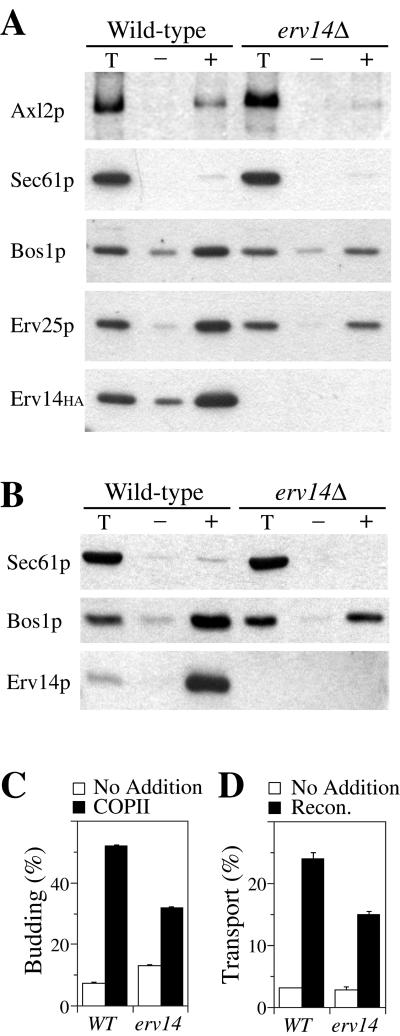

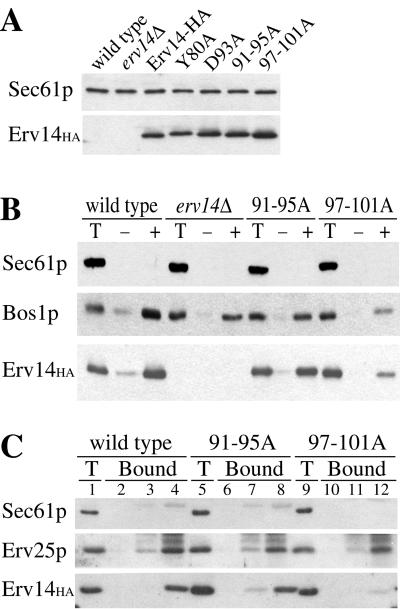

Our previous studies showed that erv14Δ strains accumulated Axl2p in the ER by an unknown mechanism. To determine whether Erv14p acts in packaging of Axl2p into ER-derived transport vesicles, we first monitored the incorporation of specific proteins into COPII vesicles by using an in vitro budding assay that reconstitutes vesicle formation from washed ER membranes (Salama et al., 1993). For these experiments, the detection of Axl2p was facilitated by modifying the chromosomal copy of AXL2 to express 13 tandem c-myc epitopes (Longtine et al., 1998). The tagged version of Axl2p was functional as assessed in bud site selection assays (Table 2) and the ER form of Axl2p-myc migrates as a 180-kDa glycoprotein. Wild-type membranes budded Axl2p-myc more efficiently (4.2%) than erv14Δ membranes (0.7%) (Figure 1A). Sec61p, an integral membrane protein that acts in protein translocation and resides in the ER (Stirling et al., 1992), served as a negative control and was not efficiently packaged into vesicles from either strain. Bos1p and Erv25p are vesicle proteins that cycle between the ER and Golgi compartments (Newman et al., 1992; Belden and Barlowe, 1996) and were packaged into ER-derived vesicles from both membranes. However, we observed that the overall budding efficiency in erv14Δ membranes was lower than in wild-type membranes. In wild-type reactions, Bos1p budding efficiency was 15% compared with 8.3% in erv14Δ reactions and Erv25p budding efficiency was 14% in wild-type compared with 8.4% in erv14Δ reactions. This effect was not related to the presence of epitope tags on Axl2p or Erv14p because the same decrease was observed when untagged strains were used (Figure 1B) and when budding (Figure 1C) and transport (Figure 1D) of the soluble secretory protein gpαf was monitored (Barlowe, 1997). Thus, erv14Δ also appears to have a general effect on the efficiency of COPII vesicle formation in vitro and we investigate this further in later sections of the report. To summarize, erv14Δ caused a strong block in Axl2p packaging (6-fold reduction), whereas other cargo monitored (Bos1p, Erv25p, and gpαf) were reduced 1.3–1.8-fold. These results demonstrated that ER membranes lacking Erv14p bud COPII vesicles but that Axl2p was not efficiently incorporated.

Table 2.

Complementation of nonaxial budding phenotype with ERV14 constructs Of log phase cells bearing at least six bud scars, those that had at least one scar on an opposite pole were classified as exhibiting a nonaxial phenotype.

| Strain | No. of cells exhibiting nonaxial budding/300 cells | % Nonaxial budding |

|---|---|---|

| CBY807 (WT) | 0 | 0.0 |

| CBY800 (erv14) | 37 | 12.3 |

| CBY812 (erv14/pRS316) | 29 | 9.7 |

| CBY813 (erv14/pRS316-ERV14-HA) | 0 | 0.0 |

| CBY867 (erv14/KS-ERV14-(Y80A)-HA) | 0 | 0.0 |

| CBY868 (erv14/KS-ERV14-(D93A)-HA) | 0 | 0.0 |

| CBY816 (erv14/ KS-ERV14-(91-95A)-HA) | 8 | 2.7 |

| CBY817 (erv14/ KS-ERV14-(97-101A)-HA) | 52 | 17.3 |

| CBY866 (erv14/ pRS315-ERV14) | 0 | 0.0 |

Figure 1.

Erv14p is required for packaging of Axl2p into COPII vesicles. (A) Immunoblot analysis of reconstituted budding reactions with membranes prepared from wild-type (CBY813; ERV14-HA, AXL2-myc) and erv14Δ (CBY800; erv14Δ, AXL2-myc) strains. One-tenth of the total budding reaction (Total) is compared with isolated budded vesicles formed after incubations in the absence (−) or presence of COPII proteins (+). (B) COPII budding reactions as in A except untagged wild-type (CBY355) and erv14Δ (CBY356) strains were used and Erv14p detected with anti-Erv14p serum. (C) COPII-dependent budding of [35S]gpαF from semi-intact cell membranes prepared from CBY355 (WT) and CBY356 (erv14) strains. Membranes were incubated alone (open bars) or with purified COPII proteins (solid bars). (D) Reconstituted transport between the ER and Golgi complex. Amount of outer-chain modified [35S]gpαF in semi-intact cell membranes incubated alone (open bars) or in the presence of COPII, Uso1p, and LMA1 (solid bars).

Erv14p Binds to Subunits of COPII Coat

The COPII coat consists of the small GTPase Sar1p and two larger heteromeric proteins, Sec23/24p complex and Sec13/31p complex. The activated form of Sar1p is thought to bind cargo proteins on the membrane surface of the ER, and then attract Sec23/24p, followed by Sec13/31p (Springer et al., 1999). Previous studies have demonstrated that components of the COPII coat form prebudding complexes with vesicle cargo proteins. More specifically, ternary complexes between GST-Sar1p, Sec23/24p and vesicle cargo can be formed in vitro and then isolated from detergent-solubilized membranes by binding to glutathione agarose. Stable ternary complex formation depends on locking the Sar1p GTPase into an activated conformation by inclusion of a nonhydrolyzable form of GTP, such as guanylyl-imidophosphate GMP-PNP (Aridor et al., 1998; Kuehn et al., 1998).

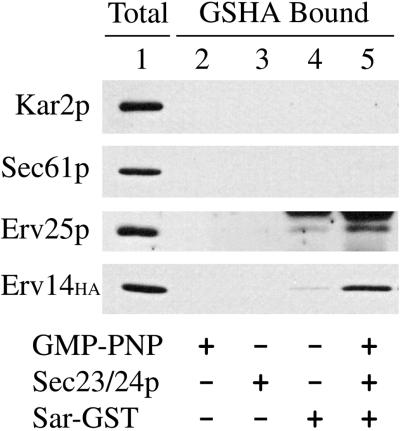

Using this approach, we tested the hypothesis that Erv14p forms a specific prebudding complex with COPII subunits. We performed in vitro COPII binding assays (Kuehn et al., 1998), incubating microsomes prepared from an epitope-tagged form of Erv14p with various combinations of GST-Sar1p, Sec23/24p, and GMP-PNP. After solubilization of membranes with digitonin, GST-Sar1p complexes were isolated by binding to glutathione agarose. As seen in Figure 2, Erv14p bound to GST-Sar1p in a reaction that depended on the presence of Sec23/24p and GMP-PNP. Omission of either one of these components resulted in at least 10-fold less binding (our unpublished data). As negative controls for this experiment, Kar2p (a soluble ER resident chaperone) and Sec61p, which are not efficiently packaged into COPII vesicles, were not detected in complex with GST-Sar1p. Erv25p, a transmembrane protein that is efficiently packaged into COPII vesicles, served as a positive control and was found to associate with COPII subunits as has been reported for other p24 proteins (Kuehn et al., 1998). Under these conditions, ∼2% of the total Erv14p-HA was recovered in complex with GST-Sar1p. These results demonstrate that Erv14p forms a specific complex with activated Sar1p and Sec23/24p through direct or indirect interactions. To gain further insight into the molecular nature of this complex, we next investigated the membrane topology of Erv14p.

Figure 2.

Erv14p forms a complex with COPII subunits. Microsomes prepared from strain CBY409 (expressing Erv14p-HA) were incubated with GMP-PNP, Sec23/24p complex, and Sar-GST as indicated. Proteins recovered on glutathione Agarose (GSHA Bound) were detected by immunoblot. The total lane (Total) represents 2% of binding reactions.

Membrane Topology of Erv14p

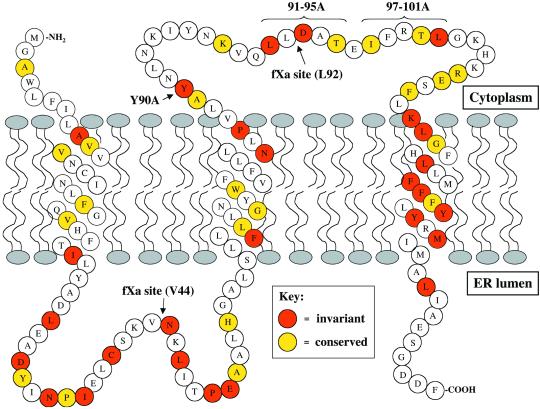

Erv14p is an integral membrane protein that possesses three segments of adequate length and hydrophobicity to span the membrane. The N terminus of Erv14p does not contain a predicted signal sequence (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). These features are shared among all reported Erv14p homologs. One predictor of membrane topology is the “positive-inside rule,” which is based on the empirical observation that positive charges are statistically enriched in the cytosolic domains of polytopic membrane proteins (von Heijne and Gavel, 1988). The topology of Erv14p predicted by this rule places the N terminus in the cytoplasm followed by three transmembrane segments and a lumenal orientation for the C terminus (Figure 7). To test this model, we first determined the accessibility of the HA-epitope when fused to the C terminus of Erv14p, to generate Erv14p-HA (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). Controlled immunofluorescence studies indicated that this epitope was accessible to antibody only in the presence of detergent (our unpublished data) and supported a lumenal location for the C terminus. However, to unambiguously determine the membrane topology for Erv14p, we performed a series of experiments by first characterizing versions of Erv14p-HA with factor Xa protease sites inserted into the predicted loop regions and then by fusing proα-factor to the C terminus.

Figure 7.

Model depicting Erv14p structure. The N terminus is cytoplasmically exposed, whereas the C terminus is in the lumen. Orange indicates invariant residues and yellow indicates conserved (4 of 5 species) residues in alignment of sequences from S. cerevisiae, C. elegans, D. melanogaster, D. virilis, and M. musculus. Arrows show sites of specific mutations described in the text and amino acids 97–101 are proposed to function in COPII interactions.

The insertion of protease sites into proteins has been used to determine the topology of polytopic membrane proteins (Preston et al., 1994; Wilkinson et al., 1996). Factor Xa is a highly specific serine protease that catalyzes the activation of prothrombin to thrombin and cleaves on the C-terminal side of a tetrapeptide repeat, IEGR (Magnusson et al., 1975). Therefore, factor Xa sites were inserted independently into each of the putative loop domains of Erv14p-HA. If inserted sites are accessible to protease in the absence of detergent, a cytosolic location is suggested, whereas protease protection is indicative of a lumenal orientation. Factor Xa protease sites were introduced into the more N-terminal hydrophilic loop at position V44 (Erv14p-V44-HA) or the more C-terminal hydrophilic loop at position L92 (Erv14p-L92-HA) (Figure 7). Expression of these modified versions of Erv14p-HA from CEN-based vectors in an erv14Δ strain resulted in wild-type expression levels and proper localization to the ER (our unpublished data).

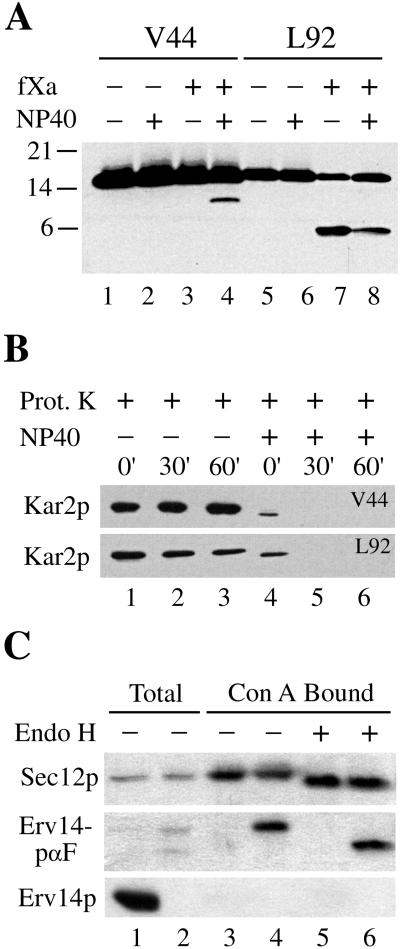

To determine the protease accessibility of these factor Xa sites, microsomes were prepared and subjected to protease digestion in the presence and absence of detergent (Figure 3A). The resulting products were analyzed by immunoblot by using the anti-HA antibody that recognizes the C-terminal epitope on these constructs. The full-length protein of both constructs was predicted to be ∼17 kDa. The appearance of the ∼12-kDa cleavage product detected by anti-HA antibody from microsomes with the Erv14p-V44-HA construct depended on membrane solubilization with detergent. In contrast, the ∼6.5-kDa immunoreactive cleavage product from the Erv14p-L92-HA construct was detected in the presence or absence of detergent. The integrity of these microsomal membrane preparations was demonstrated by the protection of Kar2p, an ER lumenal protein, from proteinase K digestion in the absence of detergent (Figure 3B). These results indicated that the N-terminal hydrophilic loop was located in the ER lumen and was protease protected, whereas the C-terminal loop was cytoplasmically exposed.

Figure 3.

Membrane topology of Erv14p. (A) Factor Xa cleavage of Erv14p-(V44)-HA and Erv14p-(L92)-HA proteins in microsomes prepared from CBY707 and CBY731, respectively. Where indicated, membranes were solubilized with 2% NP-40. Proteolytic fragments were resolved on 16% Tris/tricine gels and immunoblotted with anti-HA. (B) Proteinase K protection of Kar2p to demonstrate integrity of V44 and L92 containing microsomal membranes. (C) Microsomes prepared from CBY409 expressing Erv14p-HA (lanes 1, 3, 5) and CBY732 expressing the Erv14p-proα-Factor-HA fusion protein (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were solubilized with detergent. Total solubilized proteins (lanes 1 and 2) were compared with Con A-bound glycoproteins (lanes 3 and 4) and glycoproteins treated with endoglycosidase H (lanes 5 and 6).

We chose an independent method to confirm this topology that does not rely on protease sensitivity. We reasoned that if the C terminus of Erv14p faces the ER lumen, a C-terminal fusion with a protein containing consensus sequences for asparagine-linked (N-linked) glycosylation should result in the expression of a glycoprotein. The α-factor pheromone precursor prepro-α-factor contains a cleavable signal sequence and acquires three N-linked core-glycosylation residues in the ER lumen. This protein is further modified and proteolytically processed as it traverses the yeast secretory pathway and ultimately secreted as mature α-factor (Fuller et al., 1988). We fused the proα-factor region (lacking the signal sequence) to the C terminus of Erv14p, directly before the HA tag to generate Erv14-proα-factor-HA (Erv14-pαF-HA). As seen in Figure 3C, expression of this chimera from a CEN plasmid (strain CBY732) resulted in the production of two immunoreactive species corresponding to sizes expected for a fully glycosylated fusion protein (∼38 kDa) and an unglycoslyated form (∼32 kDa). The fusion protein was expressed at an apparently lower level than observed for Erv14p-HA (strain CBY409), perhaps due to heterogeneity in outer-chain modification or proprotein processing and loss of the HA epitope in the Golgi complex. To confirm that the immunoreactive species migrating at 38 kDa was a glycoprotein, microsomes from this strain were solubilized and total glycosylated proteins were precipitated with Con A bound to Sepharose beads. This method concentrated the 38-kDa HA-tagged species, Erv14-pαF-HA, whereas Erv14p-HA was not precipitated (Figure 3C, lanes 3 and 4). As a positive control for this procedure, the ER glycoprotein Sec12p (Nakano et al., 1988) bound Con A to an equal extent from both of these solubilized membrane preparations. Finally, treatment of the Con A-precipitated proteins with Endo H, to cleave core-linked oligosaccharides, reduced the size of Erv14p-αF-HA (Figure 3C, lane 6). As expected, this treatment resulted in an ∼6-kDa shift, which probably corresponds to the removal of three N-linked oligosaccharides (Orlean et al., 1991). Sec12p, which contains two core-linked oligosaccharides (Nakano et al., 1988), served as a control for this method and displayed Endo H sensitivity in our assay, shifting from 70 to ∼65 kDa in both strains. These collective results provide convincing evidence that the C terminus of Erv14p is located in the lumen and support the topology predicted by the positive inside rule.

Molecular Dissection of Erv14p

Based on the membrane topology of Erv14p, we focused our attention on the cytoplasmic loop region spanning amino acid residues 79–110 and hypothesized that this region may interact with the COPII budding machinery. To test this idea, we mutated conserved amino acid residues in this region to alanines. In aligning the sequence of Erv14p with homologs across several species (S. cerevisiae, C. elegans, D. melanogaster, D. virilis and M. musculus) remarkable regions of identity were observed (Figure 7) with invariant amino acid residues found at tyrosine 80, leucine 91, aspartate 93, and leucine 101. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we made modest changes, independently converting tyrosine 80 or aspartate 93 to alanines, and more drastic changes mutating residues 91–95 or 97–101 to alanines. We then expressed these constructs from CEN-based plasmids in an erv14Δ strain and determined their expression levels and assessed their ability to complement the defect in bud site selection (Table 2). All of these mutant forms of Erv14p-HA were expressed to similar levels as the wild-type protein when analyzed by anti-HA immunoblot (Figure 4A). In bud site selection assays, the alanine stretch mutant Erv14p(91-95A)-HA displayed a modest defect in axial bud site selection and the mutant Erv14p(97-101A)-HA displayed a defect as severe as the erv14Δ strain (Table 2). No defects were detected in the Y80A or D93A mutants by this assay. In strains where nonaxial budding patterns were observed, the ER form of Axl2p accumulated (our unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Residues in the cytoplasmic loop of Erv14p are required for COPII binding. (A) Expression levels of Erv14p-HA in CBY355 (wild-type), CBY800 (erv14Δ), CBY813 (Erv14p-HA), CBY867 (Y80A), CBY868 (D93A), CBY816 (91-95A), and CBY817 (97-101A) strains determined by immunoblot. (B) COPII vesicle budding from CBY409 (wild-type) CBY356 (erv14Δ), CBY808 (91-95A) and CBY809 (97-101A) microsomes as in Figure 1. (C) Isolation of COPII complexes from CBY409 (wild-type), CBY808 (91-95A), and CBY809 (97-101) microsomes as in Figure 2 except lanes 2, 6, and 10 are beads alone; lanes 3, 7, and 11 are complete reactions minus GMP-PNP; and lanes 4, 8, and 12 are complete reactions (GMP-PNP, Sec23p/24p complex, and Sar1-GST).

We next tested the influence of the Erv14p(91-95A)-HA and Erv14p(97-101A)-HA mutations on COPII-dependent vesicle formation from the ER. In the first set of experiments, the efficiency of [35S]gpαF budding efficiencies in the absence and presence of COPII was determined as follows: 7.7 ± 0.7 and 37 ± 0.5% from Erv14p-HA membranes; 9.8 ± 0.7 and 29 ± 0.2% from erv14Δ membranes; 10.2 ± 0.5 and 40.3 ± 1.5% from Erv14p(91-95A)-HA membranes; and 8.1 ± 0.2 and 25 ± 0.3% from Erv14p(97-101A)-HA membranes. These results indicated that loss of function mutations in ERV14 reduced the budding efficiency of [35S]gpαF as we had observed in Figure 1. To monitor the packaging efficiency of other vesicle cargo proteins, COPII vesicles were generated from these membranes and specific cargo detected by immunoblot (Figure 4B). In general, these results mirrored what was observed for [35S]gpαF budding. Erv14p-HA was packaged at 13%, whereas Erv14p(91-95A)-HA and Erv14p(97-101A)-HA were packaged at 11 and 4%, respectively. The vesicle protein Bos1p was incorporated into vesicles at an efficiency of 14% from wild-type membranes, 8% from Erv14p(91-95A)-HA membranes, and 4% from Erv14p(97-101A)-HA membranes. Therefore, the more severe alanine stretch mutant, Erv14p(97-101A)-HA, appeared to be a stable loss of function protein that was not efficiently packaged into COPII vesicles.

Mutations in Cytoplasmic Loop of Erv14p Influence COPII Binding

Alanine mutations in the cytoplasmic loop of Erv14p caused defects in axial bud site selection in vivo and decreased its packaging efficiency into COPII vesicles in vitro. Together, these results suggested that mutation of residues 97–101 in Erv14p to alanines interfered with an association between Erv14p and the COPII coat. To test this possibility, we performed GST-Sar1p binding assays to determine whether Erv14p(91-95A)-HA and Erv14p(97-101A)-HA formed ternary complexes as efficiently as wild-type Erv14p-HA. As in previous experiments, wild-type Erv14p-HA specifically bound to glutathione agarose under conditions where GST-Sar1p, Sec23/24p, and GMP-PNP were present (Figure 4C). In contrast, Erv14p(91-95A) displayed a slight decrease in binding level and Erv14p(97-101A)-HA failed to bind in this assay. Similar levels of Erv25p from all three membrane preparations were captured in GST-Sar1p complexes, indicating these membranes were competent for COPII binding. Other ER-resident proteins were excluded from GST-Sar1p complexes, indicating specificity of the COPII–cargo interactions. Based on these observations, we propose that residues 97–101 in Erv14p are critical for COPII binding and recruitment of this protein into vesicles.

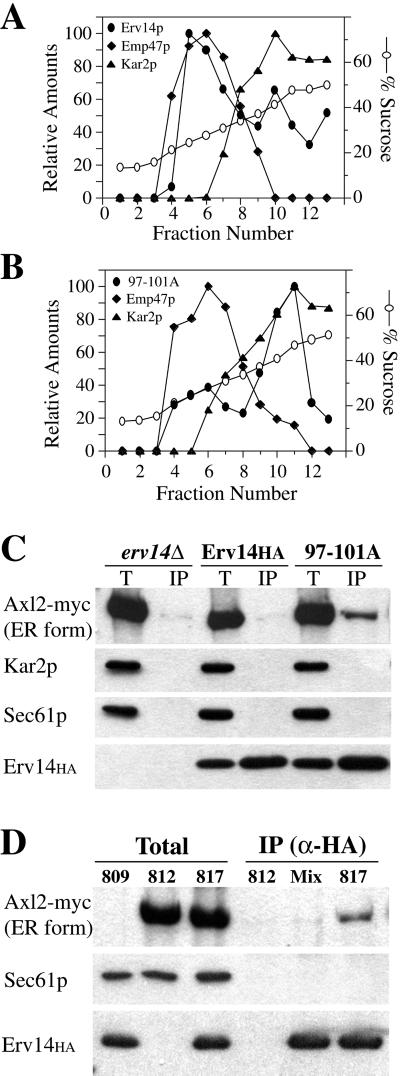

Erv14p Associates with Axl2p in ER Membranes

Previous whole cell immunofluorescence experiments and sucrose gradient fractionation of membrane organelles documented an ER/Golgi localization pattern for Erv14p and suggested that this protein cycles between these compartments (Powers and Barlowe, 1998). To determine the subcellular distribution of Erv14p(97-101A)-HA compared with wild-type Erv14p-HA, cell membranes were prepared and organelles resolved as previously described (Antebi and Fink, 1992; Powers and Barlowe, 1998). As seen in Figure 5B, conversion of amino acid residues 97–101 to alanines shifted Erv14p localization to the ER. In these gradients, Kar2p served as an ER marker that peaked in fractions 10 and 11 and Emp47p, a Golgi membrane marker, peaked in fractions 5 and 6. In wild-type cells, approximately equal amounts of Erv14p were detected in the ER and Golgi fractions, whereas >75% of Erv14p(97-101A)-HA localized to the ER fractions. These results indicate that the reduced budding efficiency of Erv14p(97-101A)-HA from ER membranes causes an accumulation of Erv14p(97-101A)-HA in this compartment.

Figure 5.

Erv14p(97-101A)-HA accumulates in the ER and is detected in complex with Axl2p. Subcellular distribution of Erv14p-HA (A) compared with Erv14p(97-101A)-HA (B). Emp47p serves as a Golgi-localized marker and Kar2p serves as an ER-localized marker. (C) Immunoblots of native anti-HA immunoprecipitations from CBY800 (erv14Δ), CBY813 (Erv14HA), and CBY817 (97-101A)-solubilized microsomes. Total lanes (Total) represent 5% of immunoprecipitation (IP) lanes. Note specific coimmunoprecipitation of Axl2-myc with Erv14p(97-101A)-HA. (D) Solubilized microsomes were prepared from CBY809 [Erv14p(97-101A)-HA], CBY812 (Axl2-myc), and CBY817 [Erv14p(97-101A)-HA/Axl2-myc]. Native anti-HA immunoprecipitations from CBY812 (812), mixed extracts from CBY809 plus CBY812 (Mix), and CBY817 (817). Note specific coimmunoprecipitation of Axl2-myc from the CBY817 extract but not from mixed extracts of CBY809 plus CBY812.

Our results are consistent with the idea that Erv14p connects Axl2p to the COPII coat during export from the ER. However, we have been unable to detect an association between wild-type Erv14p and the secretory cargo Axl2p. We reasoned that the Erv14p(97-101A)-HA mutant may accumulate an Erv14p/Axl2p complex in the ER, allowing for detection of this putative intermediate. To test this possibility, we constructed strains expressing Erv14p(97-101A)-HA and Axl2p-myc for immunoprecipitation experiments. Microsomal membranes from strains expressing Erv14-HA or Erv14p(97-101A)-HA and Axl2p-myc were solubilized with digitonin. HA-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated and the amount of Axl2p-myc associated with these native immune complexes determined by immunoblot (Figure 5C). Strikingly, an Erv14p-Axl2p complex was detected only in membranes expressing Erv14p(97-101A)-HA and Axl2p-myc. In membranes lacking Erv14p or expressing wild-type Erv14p-HA, Axl2p-myc was not detected even though the erv14Δ strain accumulates maximum levels of Axl2p-myc in the ER. Together with the observation that other abundant ER proteins (e.g., Kar2p and Sec61p) were not detected in any of these immunoprecipitations, the data indicate that this association was specific. Approximately 10% of the total Erv14p(97-101A)-HA and 0.7% of the total Axl2p-myc were recovered in these anti-HA immunoprecipitations. To further investigate the specificity of this association, we found that the Erv14p-Axl2p complex is present in membranes and does not occur after detergent solubilization (Figure 5D). In this experiment, solubilized membranes from strains expressing either Erv14p(97-101A)-HA or Axl2p-myc were mixed before immunoprecipitation. An Erv14p-Axl2p association was not detected in mixed extracts but was observed when the proteins originate in the same membrane (Figure 5D). These results suggest that this Erv14p-Axl2p complex represents an intermediate in export of Axl2p from the ER and that Erv14p performs a direct role in loading Axl2p into COPII vesicles.

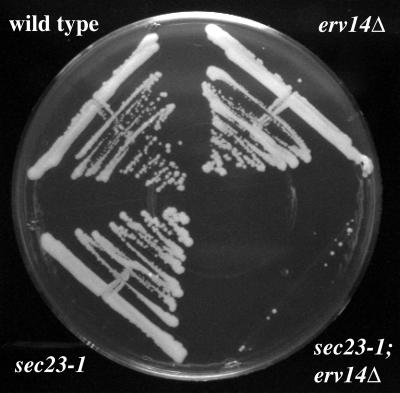

Genetic Analysis of ERV14

In vitro budding experiments shown in Figure 1 and elsewhere indicated that Erv14p was required for packaging of Axl2p into ER-derived vesicles but was also required for optimal budding of COPII vesicles. This appears to be a general effect on COPII vesicle formation because Bos1p, Erv25p, and [35S]gpαF budding efficiencies were reduced in vitro when Erv14p was absent. However, deletion of ERV14 has a modest impact on growth and overall secretion rates in vivo (Powers and Barlowe, 1998; Otte et al., 2001). To provide further insight on a general role of ERV14 in budding, we tested whether deletion of ERV14 influenced the phenotypes associated with temperature-sensitive sec mutants involved in budding and transport between the ER and Golgi complex. Examples of suppression and exacerbation of temperature sensitivity have been previously reported for other nonessential genes that operate in protein export from the ER (Elrod-Erickson and Kaiser, 1996; Gilstring et al., 1999). To test this possibility, an erv14Δ strain was mated with strains that carried thermosensitive alleles involved in COPII vesicle formation (sec12, sec13, sec16, sec23), vesicle fusion (sec18), or COPI vesicle formation (sec21). After sporulation of these diploids and dissection at room temperature, four viable spores were recovered from each tetrad. Haploids were scored for growth at room temperature (23°C), 28, 34, and 37°C to determine the impact of erv14Δ on thermosensitivity. Although no phenotype, as defined by synthetic growth effect, was observed when ERV14 was deleted in a sec12-4 background, an increased thermosensitivity was observed for double mutant segregants containing the sec13-1, sec16-2, or sec23-1 alleles (Table 3). A slow growth phenotype was observed for the erv14Δ sec13-1 strain at 23°C and this strain was inviable at 28°C. When the sec23-1 allele was present in an erv14Δ background, there was again no growth at 28°C (Figure 6), although colony size was similar to that of the wild-type strain at room temperature (our unpublished data). Similar results were obtained for the sec16-2 allele. In contrast, an erv14Δ mutation had no impact on the growth or thermosensitivity of strains containing either the sec18-1 or sec21-1 allele (Table 3). The lack of a synthetic phenotype in strains carrying either sec18-1 or sec21-1 in an erv14Δ background may indicate that these genes do not act in the same stage of transport as Erv14p. That is, Erv14p would not be predicted to function at either vesicle fusion or in retrograde vesicle trafficking between the Golgi and ER. However, the exacerbation of temperature sensitivity by erv14Δ when combined with genes involved in COPII vesicle formation suggests that Erv14p participates in this stage of the pathway.

Table 3.

Influence of erv14Δ on sec mutations Relative growth rates for erv14Δ and sec/erv14Δ haploids compared with a wild-type haploid.

| Thermosensitive allele | 23°C | 28°C | 34°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| sec12-4 | 219 | + | − |

| sec12-4 erv14Δ | 219 | + | − |

| sec13-1 | 219 | − | − |

| sec13-1 erv14Δ | + | − | − |

| sec16-2 | 219 | ++ | − |

| sec16-2 erv14Δ | 219 | − | − |

| sec23-1 | 219 | 219 | − |

| sec23-1 erv14Δ | 219 | − | − |

| sec18-1 | 219 | 219 | − |

| sec18-1 erv14Δ | 219 | 219 | − |

| sec21-1 | 219 | 219 | − |

| sec21-1 erv14Δ | 219 | 219 | − |

, signifies similar growth to wild-type, ++ and + signify varying degrees of poor growth, and − signifies no growth.

Figure 6.

Disruption of ERV14 exacerbates the thermosensitivity of a sec23-1 strain. An erv14Δ strain was crossed with a sec23-1 strain and the resulting haploid spores were tested for growth at 28°C.

These genetic experiments corroborate our in vitro budding results and suggest that Erv14p performs a role in COPII vesicle formation. It was possible that erv14Δ somehow impaired our recovery of budding competent microsomes used for in vitro assays. However, the specific genetic relationships between erv14Δ and genes encoding COPII subunits indicate that the in vitro assay reflects an authentic role for Erv14p in vesicle formation. In other instances, we have found the in vitro assays provide a more sensitive method than in vivo approaches to monitor defects in transport between the ER and Golgi (Conchon et al., 1999; Otte et al., 2001). Based on these results, we conclude that Erv14p acts in cargo selection and also facilitates COPII vesicle formation.

DISCUSSION

Erv14p was previously shown to be selectively packaged into COPII vesicles and required for in vivo export of an integral membrane secretory protein, Axl2p, from the ER. In this study, we demonstrate that Erv14p genetically and physically interacts with subunits of the COPII coat. To identify regions of the Erv14p protein responsible for this interaction, we determined the membrane topology of Erv14p and found that the protein spans the bilayer three times and possesses a cytoplasmically oriented ∼30 amino acid loop region. Residues 97–101 within this conserved loop region of Erv14p were found to be critical for function, for recruitment into COPII vesicles and for association with subunits of the COPII coat. Finally, a mutant form of Erv14p that failed to engage the COPII budding machinery accumulated in the ER and was detected in association with the secretory cargo Axl2p. Based on these observations, we propose that Erv14p serves as an adaptor that links an integral membrane secretory protein to the COPII vesicle coat.

The mechanisms underlying selective transport of proteins between the ER and Golgi remain unclear. Evidence indicates that certain integral membrane cargoes are recruited and concentrated into COPII vesicles during export from the ER (Klumperman, 2000). For example, Bet1p binds directly to subunits of the COPII coat (Springer and Schekman, 1998) and is concentrated into COPII-coated vesicles (Martinez-Menarguez et al., 1999). Other transmembrane secretory proteins, such as histidine permease, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein, and plasma membrane ATPase have been shown to bind specific subunits of the COPII coat (Aridor et al., 1998; Kuehn et al., 1998; Shimoni et al., 2000). In the case of the histidine permease, an ER resident protein, termed Shr3p, appears to coordinate the association of permease with coat (Kuehn et al., 1996; Gilstring et al., 1999). For lumenal secretory proteins, evidence for concentration during export from the ER has also been reported (Mizuno and Singer, 1993; Kuehn et al., 1998). In one well characterized example, the Emp24 complex was shown to bind a GPI anchored secretory protein in the ER and was required for packaging of this cargo into ER-derived vesicles (Muniz et al., 2000). However, evidence for bulk flow of lumenal secretory cargo from the ER has also been provided (Wieland et al., 1987; Martinez-Menarguez et al., 1999). Indeed, both receptor-mediated and bulk flow export mechanisms may operate, depending on cell type and expression levels of a given secretory cargo (Warren and Mellman, 1999).

In comparison with other documented examples of selective export, Erv14p seems to act through a novel mechanism. Herein, export of a specific integral membrane secretory protein, Axl2p, depends on a second integral membrane protein, Erv14p, that cycles between the ER and Golgi compartments. Erv14p function resembles the role that Shr3p performs in export of amino acid permeases from the ER but is clearly distinct because Shr3p is not efficiently packaged into COPII vesicles (Kuehn et al., 1996). It is not clear why Axl2p alone lacks sufficient information for packaging into COPII vesicles as appears to be the case for other integral membrane cargo (Aridor et al., 1998; Springer and Schekman, 1998; Shimoni et al., 2000). The cytoplasmic region of Axl2p is thought to interact with other bud site selection proteins to orient axial bud sites (Halme et al., 1996; Roemer et al., 1996). Therefore, this function in bud site selection may be incompatible with sequences imparting efficient sorting into COPII vesicles. It remains to be determined whether association of Erv14p and Axl2p is mediated by transmembrane segments or other domains. Both the first lumenal loop domain and the third transmembrane domain of Erv14p possess a high percentage of invariant amino acids (Figure 7) and could participate in intermolecular interactions. The interaction between Erv14p and Axl2p appears to be transient because our recovery of Erv14p-Axl2p complex was low. Alternatively, Erv14p may engage several distinct secretory proteins with Axl2p, representing a small fraction of the occupied Erv14p molecules. It is also possible that stable association of Axl2p with Erv14p depends on additional factors (e.g., COPII subunits) during export from the ER. Future experiments with purified proteins can test whether activated Sar1p and Sec23/24p complex stabilizes associations between Axl2p and Erv14p. Regardless of the precise arrangement of the Erv14p-Axl2p complex, we propose that the association is reversible such that binding is favored in the ER and disfavored at some point after export from the ER. Disassembly of the COPII coat or a different chemical environment in post-ER compartments could promote dissociation. Finally, Erv14p is probably returned to the ER through a COPI-dependent pathway. Additional studies will be required to identify signals for retrograde transport of Erv14p, although residues 97–101 could also be involved in this process.

In addition to a specific role in Axl2p export, our experiments revealed a general decrease in COPII vesicle formation in strains that lack functional Erv14p. This defect was observed in cell-free assays that reproduce COPII-dependent budding of glycopro-α-factor, Bos1p, and Erv25p. Moreover, a general role in budding was supported by genetic experiments showing that erv14Δ exacerbated the growth phenotypes exhibited by temperature-sensitive mutations in genes that function in budding from the ER (SEC13, SEC16, and SEC23), whereas vesicle fusion (SEC18) and COPI (SEC21) mutants were not influenced. A molecular explanation for this defect remains to be determined. There could be indirect consequences of cargo accumulation or Erv14p could facilitate budding by recruiting COPII subunits to bud sites on the ER membrane. In this second scenario, COPII prebudding complexes would form on many different vesicle proteins, including Erv14p, and a threshold level of prebudding complexes would be required to produce a COPII vesicle. Accordingly, the total number of COPII prebudding complexes would be significantly reduced in erv14Δ membranes and the extent of vesicle budding decreased. In support of this idea, Erv14p appears to be an abundant integral membrane constituent of COPII vesicles (Otte et al., 2001), is very efficiently packaged into these transport intermediates, and forms a tight ternary complex with the coat subunits Sar1p and Sec23p. Other components of ER/Golgi transport vesicles have been proposed to act similarly in providing a coat scaffold (Sohn et al., 1996; Bremser et al., 1999) or to serve as primers for coat formation (Springer and Schekman, 1998). However, it also seems possible that different integral membrane cargo are collectively required for efficient formation of coated vesicles and loss of a single abundant constituent such as Erv14p could reduce but does not prevent vesicle budding.

In summary, we have provided molecular insight on Erv14p function, indicating this protein acts in concert with the COPII coat in sorting an integral membrane secretory protein during export from the ER. The cross-species conservation of Erv14p is remarkable, suggesting a conserved mechanism of action. Cornichon, the Erv14p homolog in Drosophila, has been proposed to fulfill a similar role in the selective export of a transforming growth factor α-like signaling molecule, Gurken, to the oocyte cell surface. Although Gurken and Axl2p are type I transmembrane proteins that traffic to the cell surface, they do not share any apparent sequence homology. Interestingly, the transmembrane residues in Gurken are critical for its transport to the cell surface, whereas the cytoplasmic domain is dispensable (Queenan et al., 1999). Therefore, it may be informative to test a model whereby the transmembrane residues in Axl2p promote association with Erv14p and incorporation into COPII-coated vesicles. Finally, our findings suggest that other integral membrane secretory cargo may rely on adaptor-like proteins for efficient export from the ER.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Colin Stirling for advice on Factor X digests. This work was supported by a grant from The National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.01–10–0499. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/10.1091/mbc.01–10–0499.

REFERENCES

- Aridor M, Weissman J, Bannykh S, Nouffer C, Balch WE. Cargo selection by the COPII budding machinery during export from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:61–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antebi A, Fink GR. The yeast Ca2+-ATPase homologue, PMR1, is required for normal Golgi function and localizes in a novel Golgi-like distribution. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:633–654. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.6.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, R.M., Brent, R., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., and Struhl, K. (1987). Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience, 3.01–3.18.7.

- Balch W, McCaffery J, Plutner H, Farquhar M. Vesicular stomatitus virus glycoprotein is sorted and concentrated during export from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1994;76:841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe C. Coupled ER to Golgi transport reconstituted with purified cytosolic proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1097–1108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe C, Orci L, Yeung T, Hosobuchi M, Hamamoto S, Salama N, Rexach MF, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Schekman R. COPII: a membrane coat formed by Sec proteins that drive vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1994;83:895–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek SY, Ravazzola M, Hosobuchi M, Amherdt M, Perrelet A, Schekman R, Orci L. COPI- and COPII-coated vesicles bud directly from the endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. Cell. 1995;83:1183–1196. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belden WJ, Barlowe C. Erv25p, a component of COPII-coated vesicles, forms a complex with Emp24, that is required for efficient endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26939–26946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremser M, Nickel W, Schweikert M, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Hughes CA, Sollner TH, Rothman JE, Wieland FT. Coupling of coat assembly and vesicle budding to packaging of putative cargo receptors. Cell. 1999;96:495–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Barlowe C. Asymmetric requirements for a Rab GTPase and SNARE proteins in fusion of COPII vesicles with acceptor membranes. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:55–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conchon S, Cao X, Barlowe C, Pelham HRB. Got1p and Sft2p: membrane proteins involved in traffic to the Golgi complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:3934–3946. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson P, Letourneur F. Coatomer interaction with di-lysine endoplasmic reticulum retention motifs. Science. 1994;263:1629–1631. doi: 10.1126/science.8128252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod-Erickson MJ, Kaiser CA. Genes that control the fidelity of endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport identified as suppressors of vesicle budding mutations. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1043–1958. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.7.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RS, Sterne RE, Thorner J. Enzymatic regulation for yeast propheromone processing. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:345–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilstring CF, Melin-Larsson M, Ljungdahl PO. Shr3p mediates specific COPII coatomer-cargo interactions required for the packaging of amino acid permeases into ER-derived transport vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3549–3565. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halme A, Michelitch M, Mitchell E, Chant J. Bud10p directs axial cell polarization in budding yeast and resembles a transmembrane receptor. Curr Biol. 1996;6:570–579. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen W, Garcia PD, Walter P. In vitro protein translocation across the yeast endoplasmic reticulum: ATP-dependent post-translational translocation of the prepro-a-factor. Cell. 1986;45:397–406. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C, Schekman R. Distinct sets of SEC genes govern transport vesicle formation and fusion early in the secretory pathway. Cell. 1990;61:723–733. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90483-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumperman J. Transport between ER, and Golgi. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn MJ, Herrman JM, Schekman R. COPII-cargo interactions direct protein sorting into ER-derived transport vesicles. Nature. 1998;391:187–190. doi: 10.1038/34438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn MJ, Schekman R, Ljungdahl PO. Amino acid permeases require COPII components and the ER resident membrane protein Shr3p for packaging into transport vesicles in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:585–595. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie III A, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional Modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson S, Peterson TE, Sottrup-Jensen L, Claeys H. Proteases and biological control. In: Reich E, Rifkin DB, Shaw E, editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1975. pp. 127–185. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Menarguez JA, Geuze HJ, Slot JW, Klumperman J. Vesicular tubular clusters between the ER and Golgi mediate concentration of soluble secretory proteins by exclusion from COPI-coated vesicles. Cell. 1999;98:81–90. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80608-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno M, Singer SJ. A soluble secretory protein is first concentrated in the endoplasmic reticulum before transfer to the Golgi apparatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5732–5736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz M, Nuoffer C, Hauri H-P, Riezman H. The Emp24 complex recruits a specific cargo molecule into endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:925–930. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K, Thørgersen HC. Generation of a β-globin by sequence specific proteolysis of a hybrid produced in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1984;309:810–812. doi: 10.1038/309810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano A, Brada D, Schekman R. A membrane glycoprotein, Sec12p, required for transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:851–863. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.3.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AP, Groesch ME, Ferro-Novick S. Bos1p, a membrane protein required for ER to Golgi transport in yeast, co-purifies with the carrier vesicles and with Bet1p and the ER membrane. EMBO J. 1992;11:3609–3617. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N, Balch WE. A di-acidic signal required for selective export from the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1997;277:556–558. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlean P, Kuranda MJ, Albright DF. Analysis of glycoproteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:682–697. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94050-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte S, Belden WJ, Heidtman M, Liu J, Jensen ON, Barlowe C. Erv41p and Erv46p: new components of COPII vesicles involved in transport between the ER and Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:503–517. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers J, Barlowe C. Transport of Axl2p depends on Erv14p, an ER-vesicle protein related to the Drosophila cornichon gene product. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1209–1222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM, Jung JS, Guggino WB, Agre P. Membrane topology of aquaporin CHIP. Analysis of functional epitope-scanning mutants by vectorial proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1668–1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JR. Staining of bud scars and other cell wall chitin with calcolfuor. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:732–734. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94055-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queenan AM, Barcelo G, Van Buskirk C, Schupbach T. The transmembrane region of Gurken is not required for biological activity, but is necessary for transport to the oocyte membrane. Mech Dev. 1999;89:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P, Griffiths G, Warren G. Density of newly synthesized plasma membrane proteins in intracellular membranes II. Biochemical studies. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:2142–2147. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.6.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer T, Madden K, Chang J, Snyder M. Selection of axial growth sites in yeast requires Axl2p, a novel plasma membrane glycoprotein. Genes Dev. 1996;10:777–793. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.7.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Neuman-Silberberg FS, Barcelo G, Schübach T. Cornichon and the EGF receptor signaling processes are necessary for both anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral pattern formation in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:967–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama NR, Yeung T, Schekman R. The Sec13p complex and reconstitution of vesicle budding from the ER with purified cytosolic proteins. EMBO J. 1993;12:4073–4082. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–20. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni Y, Kurihara T, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Orci L, Schekman R. Lst1p and Sec24p cooperate in sorting of the plasma membrane ATPase into COPII vesicles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:973–984. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn K, Orci L, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Bremser M, Lottspeich F, Fiedler K, Helms JB, Wieland FT. A major transmembrane protein of Golgi-derived COPI-coated vesicles involved in coatomer binding. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1239–1248. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer S, Schekman R. Nucleation of COPII vesicular coat complex by endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi vesicle SNAREs. Science. 1998;281:698–700. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer S, Spang A, Schekman R. A primer on vesicle budding. Cell. 1999;97:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling CJ, Rothblatt J, Deshaies R, Schekman R. Protein translocation mutants defective in the insertion of integral membrane proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:129–142. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G, Gavel Y. Topogenic signals in integral membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1988;174:671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren G, Mellman I. Bulk flow redux? Cell. 1999;98:125–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland FT, Gleason ML, Serafini TA, Rothman JE. The rate of bulk flow from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell surface. Cell. 1987;50:289–300. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson BM, Critchley AJ, Stirling CJ. Determination of the transmembrane topology of yeast Sec61p, an essential component of the endoplasmic reticulum translocation complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25590–25597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]