Abstract

The soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis has developed a highly controlled system for the utilization of a diverse array of low-molecular-weight compounds as a nitrogen source when the preferred nitrogen sources, e.g., glutamate plus ammonia, are exhausted. We have identified such a system for the utilization of purines as nitrogen source in B. subtilis. Based on growth studies of strains with knockout mutations in genes, complemented with enzyme analysis, we could ascribe functions to 14 genes encoding enzymes or proteins of the purine degradation pathway. A functional xanthine dehydrogenase requires expression of five genes (pucA, pucB, pucC, pucD, and pucE). Uricase activity is encoded by the pucL and pucM genes, and a uric acid transport system is encoded by pucJ and pucK. Allantoinase is encoded by the pucH gene, and allantoin permease is encoded by the pucI gene. Allantoate amidohydrolase is encoded by pucF. In a pucR mutant, the level of expression was low for all genes tested, indicating that PucR is a positive regulator of puc gene expression. All 14 genes except pucI are located in a gene cluster at 284 to 285° on the chromosome and are contained in six transcription units, which are expressed when cells are grown with glutamate as the nitrogen source (limiting conditions), but not when grown on glutamate plus ammonia (excess conditions). Our data suggest that the 14 genes and the gde gene, encoding guanine deaminase, constitute a regulon controlled by the pucR gene product. Allantoic acid, allantoin, and uric acid were all found to function as effector molecules for PucR-dependent regulation of puc gene expression. When cells were grown in the presence of glutamate plus allantoin, a 3- to 10-fold increase in expression was seen for most of the genes. However, expression of the pucABCDE unit was decreased 16-fold, while expression of pucR was decreased 4-fold in the presence of allantoin. We have identified genes of the purine degradation pathway in B. subtilis and showed that their expression is subject to both general nitrogen catabolite control and pathway-specific control.

Purines are major components of nucleic acids and nucleotides and are continuously formed and degraded in the biosphere. The purine nucleotides are synthesized de novo from phosphoribosylpyrophosphate, amino acids, CO2, and formate. When nucleotides are degraded to nucleobases and nucleosides, they may be reutilized via purine salvage pathways (29) or further degraded. The ability to degrade purine compounds has been found in all kingdoms and can occur either aerobically or anaerobically, but by separate pathways (9, 46). In the aerobic pathway, the committed step in the degradation of purine bases is the oxidation of hypoxanthine and xanthine to uric acid, catalyzed by xanthine dehydrogenase. The various purine-degradative pathways are unique and differ from other metabolic pathways because they may serve quite different purposes, depending on the organism or tissue. The purines or their immediate degradation products, which are subjected to further degradation, are abundant in nature. They arise from decaying tissue or organisms or are excreted by living cells. While some organisms degrade the naturally occurring purines to CO2 and ammonia, other organisms contain only some of the steps of the purine degradation pathways, resulting in partial degradation of purines or certain intermediary compounds of the degradation pathways. In human, anthropoid apes, birds, uricotelic reptiles, and almost all insects, uric acid is the end product (18, 52), and it is subsequently excreted. Allantoin is the end product in uricolytic organisms such as most mammals, some insects, and gastropods (13, 18). Fish, amphibians, and lamellibranchs completely degrade purines to urea, ammonia, and CO2 (17, 18, 27). In most higher plants, degradation of purine bases gives rise to CO2 and ammonia (1). However, in certain plant tissues, e.g., in the root nodules of legumes, newly fixed nitrogen incorporated into purine nucleotides by the nodule bacteria is converted to allantoin and allantoic acid, which play an important and major role in the storage and translocation of nitrogen to other tissues (26, 41).

Bacteria and fungi have the capacity to utilize a diverse array of compounds, including purines, as nitrogen source and often also as carbon sources (24). In Bacillus subtilis, the natural purine bases all serve as nitrogen sources when the preferred nitrogen sources, e.g., glutamate plus ammonia or glutamine, are exhausted. When the preferred nitrogen sources are not present in the growth medium, genes are activated that enable the cell to utilize alternative nitrogen sources, and both global and pathway-specific signals may be involved (12). Three proteins, GlnA, GlnR, and TnrA, regulate the expression of several operons governing nitrogen metabolism (39, 48, 50). Recently we found that expression of the gde gene, encoding guanine deaminase, is subject to general nitrogen control and a pathway-specific control mechanism (30).

In spite of the importance of the purine degradation pathways, there are only a few reports about the genetics of the pathway in bacteria. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the genes that encode the initial deamination step in the utilization of adenine and guanine as nitrogen sources are located separately on the chromosome, while the genes encoding the enzymes catalyzing the degradation of hypoxanthine to ureidoglycolic acid are linked (24). Aerobically grown Escherichia coli is not known to use purines other than adenosine as the sole nitrogen source, by the deamination of adenosine to inosine and ammonia (29). Recently it was reported that E. coli possesses a gene encoding guanine deaminase (25) and several genes encoding enzymes and proteins of the purine catabolic pathway (53). The expression of these genes is most likely not high enough to support growth on purines as the sole nitrogen source; however, purines stimulated growth when aspartate served as the nitrogen source (53). E. coli can utilize allantoin but not hypoxanthine as a nitrogen source under anaerobic conditions. The genes encoding enzymes of allantoin and glyoxylic acid metabolism are clustered (8), and the expression of these genes is controlled by the allR gene product, with allantoin and glyoxylic acid serving as the effector molecules.

The most detailed information about the genetic control of purine degradation has been obtained in fungi, namely Aspergillus nidulans (37), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5), and Neurospora crassa (23). Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, genes of the hypoxanthine degradation pathway in A. nidulans are induced by a globally acting protein and a pathway-specific regulatory protein, UAY, with uric acid acting as the effector molecule. UAY is required for the expression of at least nine unlinked genes involved in uptake and metabolism of purine compounds (42–44). The uaY gene is expressed constitutively and is not subject to nitrogen control (11). S. cerevisiae uses exogenous allantoin as a nitrogen source and can also store allantoin for later use. The genes necessary for allantoin utilization are clustered, and gene expression is subject to nitrogen catabolite repression and induced by intermediary compounds that can be degraded to allophanate (6).

This work is a comprehensive study on the function and regulation of genes involved in purine degradation in bacteria. Fifteen genes encoding proteins involved in the degradation of guanine have now been identified with respect to function and pattern of expression. The expression is governed by the general nitrogen control system plus a pathway-specific control most likely exerted by the PucR protein and an intermediary compound of the purine degradation pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and DNA primers used in this work are listed in Table 1. B. subtilis was grown in Spizizen minimal salt medium (36), in which disodium sulfate (0.1% final concentration) was substituted for ammonium sulfate. The minimal medium was supplemented with 40 mg of l-tryptophan per liter and with 0.4% glucose as the carbon source. As nitrogen sources, ammonia, purines, or intermediary compounds of the purine catabolic pathway were added as indicated. L broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was used as a rich medium. Culturing of cells was performed at 37°C. For selection of antibiotic resistance, antibiotics were used at the following final concentrations: ampicillin, 100 mg/liter; erythromycin, 1 mg/liter; lincomycin, 25 mg/liter; neomycin, 5 mg/liter; and chloramphenicol, 6 mg/liter.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and DNA primers used in this work

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant characteristics | Source or 5′-linked restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | C. Anagnostopoulosa |

| BFA2232 | trpC2 ywoE::pE1 (erm) | This workb |

| BFA2276 | trpC2 yunH::pYUNH (erm) | This work |

| BFA2277 | trpC2 yunI::pYUNI (erm) | This work |

| BFA2278 | trpC2 yunJ::pYUNJ (erm) | This work |

| BFA2279 | trpC2 yunK::pYUNK (erm) | This work |

| BFA2280 | trpC2 yunL::pYUNL (erm) | This work |

| BFA2281 | trpC2 yunM::pYUNM (erm) | This work |

| BFA2282 | trpC2 yurB::pYURB (erm) | This work |

| BFA2283 | trpC2 yurD::pYURD (erm) | This work |

| BFA2284 | trpC2 yurE::pYURE (erm) | This work |

| BFA2285 | trpC2 yurG::pYURG (erm) | This work |

| BFA2286 | trpC2 yurH::pYURH (erm) | This work |

| BFA2308 | trpC2 yurC::pYURC (erm) | This work |

| BFA2309 | trpC2 yurF::pYURF (erm) | This work |

| CZ01 | trpC2 amyE::[pPUCR pucR′-lacZ(neo)] | Transformation of 168 by pPUCR, Neo |

| CZ02 | trpC2 amyE::[pPUCR pucR′-lacZ (neo)] pucR::pBOER (cat) | Transformation of CZ01 by pBOER, Cm |

| E. coli MC1061 | F−araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7696 galE15 galK16 Δ(lac)X74 rpsl (Strr) hsdR2 (r− m−) mcrA mcrB | Laboratory stock |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMutin1 | Apr (E. coli), Err (B. subtilis); integration vector for knockout mutations and formation of transcriptional lacZ fusions; IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter introduced to ensure expression of downstream genes | 45 |

| pDG268neo | Apr (E. coli), Neor (B. subtilis); vector used for integration of transcriptional lacZ fusions into amyE gene of B. subtilis | 36 |

| pBOE335 | Apr (E. coli), Cmr (B. subtilis); integration vector, pUC19 containing cat gene cloned into KasI site | 36 |

| pBOER | pBOE335 digested with HindIII and BamHI and ligated to 226-bp PCR fragment (primers 03 + 04) digested with the same enzymes | This work |

| pPUCR | pDG268neo digested with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated to a PCR fragment (primers 01 + 02) digested with the same enzymes | This work |

| DNA primersc | ||

| pucR-lacZ fusion | ||

| 01 | 5′-GCGGGATCCCCCCTCCTGCTTTTCC-3′ | BamHI |

| 02 | 5′-GCCGAAGCTTCGCACCTTTTATCACC-3′ | HindIII |

| pucR knockout | ||

| 03 | 5′-GCCGAAGCTTACATCCTTCAGCTTCCC-3′ | HindIII |

| 04 | 5′-GCGGGATCCATCCTTTGTCGCCTGCC-3′ | BamHI |

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Jouy-en-Josas, France.

BFA strains constructed during this work have been deposited in the database of the European Bacillus subtilis Gene Function Analysis Framework. All necessary information about the construction of the strains is accessible at http://locus.jouy.inra.fr/cgi-bin/genmic/madbase_home.pl.

Underlining indicates the position of the 5′-linked restiction site.

DNA manipulations and genetic techniques.

B. subtilis chromosomal DNA and plasmid DNA from E. coli were isolated and transformed into E. coli and B. subtilis as previously described (36). A standard PCR was performed as described previously (56). The correct sequence of all PCR products was controlled by DNA sequencing using the Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Cleveland, Ohio) Thermo Sequenase radiolabeled termination cycle sequencing kit.

Construction of BFA strains.

The use of the pMutin plasmid series for the generation of plasmid insertion mutations in B. subtilis has been described by Vagner et al. (45). All necessary information about the primers, plasmids, and bacterial strains used in the construction of the BFA knockout mutants has been deposited in the public part of the Micado database (http://locus.jouy.inra.fr /cgi-bin/genmic/madbase_home.pl).

Enzyme assays.

Cells were harvested in the exponential growth phase and homogenized by sonication in 30 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5)–1 mM EDTA–1 mM dithiothreitol. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation. To prepare the uricase solution, 0.2 mM [14C]hypoxanthine (15 mCi/mmol) in 50 mM glycine–NaOH (pH 9.0) was incubated with xanthine oxidase (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), 0.1 U/ml. After 2 h, during which all labeling was converted to [14C]uric acid, xanthine oxidase was inactivated by heating the reaction mixture to 100°C. Uricase activity was determined by measuring the formation of 14C-labeled allantoin from [14C]uric acid. The assay mixture contained 40 μl of uricase solution plus 10 μl of cell extract (3 to 6 mg of protein/ml). After 1, 4, 7, and 10 min of incubation, 10-μl samples were removed and spotted on a polyethyleneimine-impregnated thin-layer chromatography plate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The chromatogram was dried and developed in methanol to the application line and then in water to separate uric acid from allantoin. The plate was dried, and radioactivity was measured in an InstantImager (Packard, Hartford, Conn.). Guanine deaminase activity was determined as previously described (30). Allantoinase and allantoate amidohydrolase activity were determined as described by Vogels and van der Drift (47) and Pineda and coworkers (33), respectively. β-Galactosidase and xanthine dehydrogenase activities were determined as described before (4). All enzyme determinations were repeated at least three times. One unit of enzyme activity is defined as nanomoles of product formed per minute. Total protein was determined by the Lowry method.

RESULTS

Localization of purine catabolic genes on the B. subtilis chromosome.

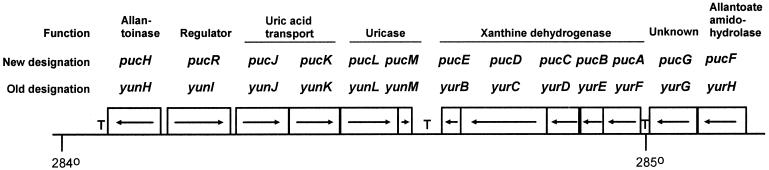

The list of the deduced amino acid sequences for all the potential open reading frames (ORFs) of the B. subtilis genome (19) was examined for ORFs with similarity to known purine-catabolic enzymes. The ORFs yunH, yunL, yurC, and yurH showed amino acid sequence identity to allantoinase (yunH, 29% to S. cerevisiae allantoinase DAL1, accession no. M69294), uricase (yunL, 42% to Bacillus sp. uricase, accession no. D49974), xanthine dehydrogenase (yurC, 28% in a 678-amino-acid overlap with A. nidulans xanthine dehydrogenase, accession no. X82827), and allantoate amidohydrolase (yurH, 47% to E. coli AllC, accession no. U89279). All four genes are located around position 284 to 285° on the B. subtilis chromosome (Fig. 1). ORF ywoE shows amino acid sequence identity to allantoin permease (27% in a 449-amino-acid overlap with S. cerevisiae allantoin permease DAL4, accession no. Z15121) and is located at 321°. The ORFs located next to yunH, yunL, yurC, and yurH showed amino acid sequence identity to proteins with functions other than purine catabolism. The ORFs yurB and yurD have amino acid sequence identity to nicotine dehydrogenase B chain (accession no. X75338) and CO dehydrogenase medium chain (accession no. U80806), respectively; yurG has amino acid sequence identity to an aminotransferase (accession no. D13368); yunJ and yunK show extensive amino acid sequence identity (51 and 42%, respectively) to B. subtilis xanthine permease PbuX (accession no. X83878). The deduced amino acid sequence of the yunI ORF showed low amino acid sequence identity (14% over a 517-amino-acid segment) to the SrmR transcription regulator (14). Interestingly, the highest degree of amino acid sequence identity between the two sequences was found in the absolute C-terminal part. This 27-amino-acid segment showed some homology to the DNA-binding domain of the LysR-type transcriptional regulators. The ORFs yunM, yurE, and yurF did not show any significant amino acid sequence identity to proteins with a known function. The gene organization in the 284 to 285° region is shown in Fig. 1. None of the ORFs located in the vicinity of ywoE encode purine catabolic enzymes.

FIG. 1.

Organization of gene cluster at 284 to 285° on the B. subtilis genome that encodes most of the functions for purine degradation. One degree of the B. subtilis chromosome equals 11.7 kb of DNA. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. Correlations between the new puc gene designations, the systematic gene names, and gene function are indicated. T's in bold type indicate positions of possible factor-independent transcription termination nucleotide sequences.

Growth of wild-type B. subtilis and mutant strains in liquid medium containing purines or purine catabolic intermediates as a nitrogen source.

ywoE and 13 ORFs in the 284 to 285° region were inactivated by integration of the plasmid pMutin1. Internal segments of the genes were amplified by PCR and cloned into pMutin1, and the resulting plasmids were transformed into the wild-type B. subtilis strain. Integration of pMutin derivatives results in three things: the target gene is inactivated, a transcriptional lacZ fusion to the upstream regulatory region is generated, and the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible Pspac promoter is inserted so that expression of downstream genes is induced by the addition of IPTG (45).

It has previously been reported that B. subtilis 168 can use uric acid, allantoin, allantoic acid, adenine, hypoxanthine, xanthine, guanine (supplied in the form of guanosine, which is converted to guanine after transport in to the cell), and urea as sole nitrogen sources (7, 30, 31, 35). As a first attempt to identify the effect of inactivation of the individual genes, mutant strains were grown in liquid glucose minimal medium containing purines or intermediates of the purine catabolic pathway as the sole nitrogen source. All media contained IPTG to ensure that genes located downstream of the pMutin1 insertion point were expressed (45). Table 2 presents the result of a growth yield experiment obtained with 13 mutant strains defective in the genes in the 284 to 285° region of the chromosome. yurB, yurC, yurD, yurE, and yurF mutants could utilize all the compounds tested except guanosine and hypoxanthine. This indicates that the first step of the pathway catalyzed by xanthine dehydrogenase is defective in these mutants. yunL and yunM mutants were defective in the utilization of guanosine, hypoxanthine, and uric acid, which indicates a defective uricase enzyme. The yunH strain could utilize hypoxanthine, guanosine, uric acid, or allantoin as a nitrogen source. As mentioned above, the amino acid sequence identity between the YunH reading frame and the allantoinase from S. cerevisiae is high. This indicates that yunH encodes an allantoinase. The yurH mutant exhibits the same growth phenotype as the yunH mutant strain. However, amino acid sequence alignment studies indicate that YurH has identity with allantoate amidohydrolase and not allantoinase. Allantoic acid is unstable in solution and disintegrates into ammonia and ureidoglycolic acid, and we observed that ureidoglycolic acid disintegrates into urea and glyoxylic acid (data not given). We therefore suggest that growth of the yurH mutant strain on allantoic acid as the sole nitrogen source is due to the spontaneous degradation of allantoic acid to ammonia and ureidoglycolic acid, which is then converted to urea and glyoxylic acid by spontaneous degradation and by the action of ureidoglycolase. The yurG strain grew poorly on allantoic acid but like the wild type on ureidoglycolic acid. The amino acid sequence identity of YurG to known aminotransferases could indicate that yurG encodes a ureidoglycolase and that the observed growth on ureidoglycolic acid was due to spontaneous degradation of the substance to urea and glyoxylic acid. Finally, the yunI strain could not grow on any of the compounds tested. This phenotype could be due either to a defect in the terminal step of the pathway catalyzed by ureidoglycolase or to a defective positive regulator of the purine catabolic pathway.

TABLE 2.

Suggested phenotype based on growth yield of cultures of B. subtilis BFA mutant strains after 72 h of growth in minimal medium supplemented with ammonia or different intermediates of the purine catabolic pathway as the sole source of nitrogena

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Relative growth yield (% of wild type) with

different nitrogen sourcesb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonia | Guanosine | Hypoxanthine | Uric acid | Allantoin | Allantoic acid | Ureidoglycolic acid | ||

| 168 | Wild type | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| BFA2309 | yurF | 90–100 | 1–10 | 1–10 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2284 | yurE | 90–100 | 1–10 | 1–10 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2283 | yurD | 90–100 | 1–10 | 1–10 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2308 | yurC | 90–100 | 1–10 | 1–10 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2282 | yurB | 90–100 | 60–70 | 1–10 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2280 | yunL | 90–100 | 10–20 | 10–20 | 1–10 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2281 | yunM | 90–100 | 10–20 | 10–20 | 10–20 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2276 | yunH | 90–100 | 1–10 | 1–10 | <1 | <1 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2286 | yurH | 90–100 | 1–10 | 10–20 | <1 | <1 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2285 | yurG | 90–100 | 20–30c | 20–30c | 10–20c | 1–10c | 1–10c | 90–100 |

| BFA2277 | yunI | 90–100 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1–10 | 1–10 |

| BFA2278 | yunJ | 90–100 | 60–70 | 10–20 | <1 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

| BFA2279 | yunK | 90–100 | 60–70 | 10–20 | <1 | 90–100 | 90–100 | 90–100 |

Cells were grown for 72 h in glucose minimal medium supplemented with 0.1 mM IPTG in microtiter plates (100 μl per well) at 37°C. Nitrogen sources were added at the following concentrations: ammonia, 1.5 mM; guanosine, 0.88 mM; hypoxanthine, 1 mM; uric acid, 1.5 mM; allantoin, 1.6 mM; allantoic acid, 1.6 mM; and ureidoglycolic acid, 2 mM. Every 12 h the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was monitored in an EL X 800 Bio-Tek Instruments enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. The start OD450 was 0.005 for all cultures.

Growth yield data from three different experiments calculated as percent wild-type growth fell within the indicated range.

After another 30 h of incubation, the level approached 90 to 100% of the wild-type growth yield.

Mutants defective in yunJ and yunK, which encode proteins with extensive amino acid sequence identity to the B. subtilis PbuX xanthine transporter, could not utilize uric acid and showed a reduced ability to utilize guanosine and hypoxanthine. Both the yunJ and yunK mutants excrete uric acid when grown on hypoxanthine, and this may explain why hypoxanthine is used less efficiently by these mutant strains (data not shown). These results indicate that yunJ and yunK mutants most likely have lost the capacity for uric acid uptake. The ywoE mutant could grow on all tested compounds except allantoin (data not shown). Since the ywoE mutant can grow on uric acid and utilization of uric acid requires allantoinase activity, this mutant is most likely defective in the uptake of allantoin.

Gene-enzyme relationships.

To confirm the results of the growth analysis, selected enzymes of the purine-degradative pathway were determined (Table 3). Unfortunately, we were unable to find assay conditions for the measurement of ureidoglycolase. The yunI strain BFA2277 has no xanthine dehydrogenase, uricase, allantoinase, or allantoate amidohydrolase activity. Since these enzyme activities should be unaffected in a ureidoglycolase-defective mutant, we conclude that yunI most likely encodes a trans-acting activator protein which is essential for induction of the purine catabolic pathway in B. subtilis. It is interesting that only the yunI mutant was unable to utilize ureidoglycolic acid as the sole nitrogen source. The spontaneous degradation of ureidoglycolic acid to urea results in formation of urea and glyoxylic acid, which is toxic to the cell unless degraded (34). We therefore suggest that the metabolism of glyoxylic acid might also be activated by YunI. However, this was not analyzed further. The yunI gene was renamed pucR for purine catabolism regulator (Fig. 1). Mutants with inactivated yurB, yurC, yurD, yurE, or yurF were found to lack xanthine dehydrogenase activity, and these genes were renamed pucE, pucD, pucC, pucB, and pucA, respectively (Fig. 1). yunL and yunM mutant strains lack uricase activity, and the genes were renamed pucL and pucM, respectively (Fig. 1). The yunH mutant lacks allantoinase activity, and the gene was renamed pucH (Fig. 1). Since yunJ and yunK mutants showed decreased ability to utilize compounds leading to uric acid formation (Table 2, guanosine and hypoxanthine), uricase levels were determined in these strains. The uricase-encoding genes pucL and pucM are expressed from the Pspac promoter of the pMutin1 insertion in strains BFA2278 (yunJ::pYUNJ) and BFA2279 (yunK::pYUNK). The growth medium contained the same concentration of IPTG (0.1 mM) as the one used in the growth yield experiment (Table 2). As shown in Table 3, the presence of IPTG resulted in the production of only low levels of uricase activity compared to the wild-type strain. This can explain why yunJ and yunK mutants have reduced growth yield when grown with guanosine or hypoxanthine as the nitrogen source (Table 2). yunJ and yunK were renamed pucJ and pucK, respectively (Fig. 1). The yurH strain lacks allantoate amidohydrolase activity and was renamed pucF (Fig. 1). The yurG mutant is defective in the utilization of all purines and intermediary compounds. YurG is similar to aminotransferases, and the yurG mutant strain contains allantoinase and allantoic acid amidohydrolase activity. Due to the lack of a suitable assay for ureidoglycolase and because of the instability of ureidoglycolic acid, we were unable to conclude whether yurG encodes ureidoglycolase or not. However, since YurG is involved in purine catabolism (Table 2), we renamed yurG pucG (Fig. 1). The ywoE gene, which encodes the allantoin transporter, was renamed pucI.

TABLE 3.

Xanthine dehydrogenase, uricase, allantoinase, and allantoate amidohydrolase activity in B. subtilis wild type and selected mutant derivativesa

| Strain | Gene inactivated by pMutin1 | Enzyme activity (U/mg of protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XDHase | Uricase | Allantoinase | Allantoate amidohydrolase | ||

| 168 | None | 7.3 ± 1.3 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 1,861 ± 215 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| BFA2282 | yurB | <0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| BFA2308 | yurC | <0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| BFA2283 | yurD | <0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| BFA2284 | yurE | <0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| BFA2309 | yurF | <0.1 | nd | nd | nd |

| BFA2280 | yunL | nd | <0.1 | nd | nd |

| BFA2281 | yunM | nd | 0.6 ± 0.1 | nd | nd |

| BFA2276 | yunH | nd | nd | <20 | nd |

| BFA2277 | yunI | <0.1 | <0.1 | 26 ± 4 | <0.1 |

| BFA2278 | yunJ | nd | 0.3 ± 0.1 | nd | nd |

| BFA2279 | yunK | nd | 1.0 ± 0.6 | nd | nd |

| BFA2286 | yurH | nd | nd | 2,415 ± 546 | <0.1 |

| BFA2285 | yurG | nd | nd | 1,791 ± 713 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

Cells were grown in glucose minimal medium supplemented with 0.1 mM IPTG and with 14 mM glutamate and 1.6 mM allantoin as the nitrogen source. In cultures in which xanthine dehydrogenase (XDHase) activity was measured, allantoin was omitted. Enzyme assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means of three separate measurements. nd, not determined.

Expression of purine catabolic genes.

Based on the position of putative transcription terminator sequences in the 284 to 285° region and on the length of the intercistronic regions, we suggest five potential transcription units in this region, pucH, pucR, pucJKLM, pucABCDE, and pucFG (Fig. 1). pucI, in the 321° region, apparently consists of a monocistronic transcription unit. To analyze the expression of these transcription units during growth on different nitrogen sources, β-galactosidase activity was determined in strains with pMutin1 integrated into pucH (BFA2276), pucR (BFA2277), pucJ (BFA2278), pucL (BFA2280), pucA (BFA2309), pucF (BFA2286), and pucI (BFA2232). As demonstrated by Vagner and coworkers (45), proper integration of pMutin1 plasmids leads to the formation of a transcriptional fusion between the target gene and the lacZ reporter gene of the plasmid. During growth with excess nitrogen (ammonia plus glutamate), the β-galactosidase levels in the puc-lacZ cells were similar to the levels present in cells lacking a lacZ fusion (strain 168; Table 4). Growth under limiting nitrogen conditions (glutamate) resulted in induced levels of β-galactosidase activity in all of the strains. When the intermediary compound allantoin was added together with glutamate, a threefold induction of pucH, pucJ, and pucF expression was observed, while expression of the inactivated pucR gene in strain BFA2277 was unaffected. On the contrary, the expression of pucA was significantly repressed in the presence of allantoin. The expression of the rest of the genes of the proposed polycistronic transcription units (pucJKLM, pucABCDE, and pucFG) was determined under the same growth conditions, and they all showed the same regulatory pattern as the selected representative genes (data not shown). Since strains BFA2276 (allantoinase negative) and BFA2232 (allantoin permease negative) are unable to metabolize allantoin, these strains were also grown in the presence of allantoic acid. An increase in the β-galactosidase level for both strains was observed. When uric acid was added together with glutamate to strain BFA2280 (defective in uricase activity), the level of expression was similar to that observed with allantoin. This indicates that uric acid, allantoin, and allantoic acid or products related to these compounds can act as the inducer substance.

TABLE 4.

Effect of excess and limiting-nitrogen growth conditions and of the presence of allantoin, allantoic acid, and uric acid on the level of β-galactosidase expressed from the transcriptional lacZ fusions of a series of BFA strainsa

| Strain | Gene fusion | Gene fused to lacZ | Nitrogen sourceb | Mean β-galactosidase activityc (U/mg of protein) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 168 | None | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 | |

| Glutamate | 1 ± 0.5 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 1 ± 0.5 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoate | 1 ± 0.5 | |||

| BFA2276 | yunH::(pYUNH yunH′-lacZ) | pucH | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 12 ± 2 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 37 ± 4 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoate | 113 ± 4 | |||

| BFA2278 | yunJ::(pYUNJ yunJ′-lacZ) | pucJ | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 18 ± 4 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 66 ± 13 | |||

| BFA2280 | yunL::(pYUNL yunL′-lacZ) | pucL | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 58 ± 9 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 230 ± 36 | |||

| Glutamate + uric acid | 213 ± 78 | |||

| BFA2309 | yurF::(pYURF yurF′-lacZ) | pucA | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 212 ± 8 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 13 ± 4 | |||

| BFA2286 | yurH::(pYURH yurH′-lacZ) | pucF | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 646 ± 77 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 1,839 ± 199 | |||

| BFA2232 | ywoE::(pE1 ywoE′-lacZ) | pucI | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 5 ± 2 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 52 ± 10 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoate | 435 ± 53 | |||

| BFA2277 | yunI::(pYUNI yunI′-lacZ) | pucR | Glutamate + NH4+ | 1 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 660 ± 181 | |||

| Glutamate + allantoin | 632 ± 123 |

Cells were grown in glucose minimal medium supplemented with 14 mM glutamate and 0.1 mM IPTG. NH4+, allantoin, allantoate, and uric acid were added at the concentrations indicated in Table 2, footnote a.

Glutamate plus NH4+ defines excess nitrogen conditions, whereas glutamate, glutamate plus allantoin, allantoic acid, or uric acid defines limiting-nitrogen conditions.

Enzyme levels are given as mean ± standard deviation calculated from at least five independent growth experiments.

In order to analyze whether PucR regulates its own synthesis, we cloned the upstream regulatory region of pucR in front of lacZ in plasmid pDG268neo, which integrates into the amyE locus upon transformation into B. subtilis. Expression of the pucR′-lacZ fusion was analyzed in the wild type and a pucR knockout mutant. As shown in Table 5, addition of allantoin during limiting-nitrogen growth conditions resulted in a fourfold decrease in pucR expression. In the pucR genetic background, high constitutive pucR expression was observed. It was therefore evident that pucR expression is subject to autoregulation. We also determined the level of guanine deaminase encoded by gde as affected by PucR in cells growing with glutamate plus allantoin as the nitrogen source. The level was 40 ± 4 U/mg of protein in the wild type and 1.0±0.1 U/mg of protein in the pucR strain BFA2277.

TABLE 5.

β-Galactosidase produced from transcriptional fusions between lacZ and the regulatory region upstream of pucR integrated amyE locus of the wild-type B. subtilis strain and a pucR derivative grown under different nitrogen conditionsa

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-galactosidase activity (U/mg of protein)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate + NH4+ | Glutamate | Glutamate + allantoin | ||

| CZ01 | amyE::(pPUCR pucR′-lacZ) | 1 | 66 | 15 |

| CZ02 | amyE::(pPUCR pucR′-lacZ) pucR::pBOER | 1 | 511 | 433 |

Cells were grown in glucose minimal medium supplemented with the stated nitrogen source. Enzyme levels are given as means of three experiments. The variation was less than 20%.

DISCUSSION

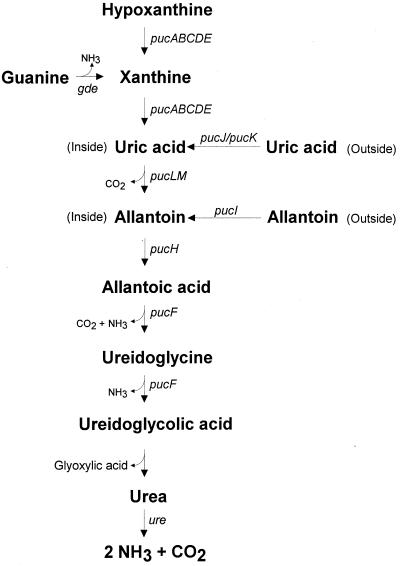

From the results of the growth phenotype analysis and the enzyme activity measurements of the different BFA strains and from work by Nygaard and coworkers (30), we conclude that B. subtilis contains the aerobic purine degradation pathway illustrated in Fig. 2 and that the genes most likely are organized as single genes and small operons.

FIG. 2.

Purine degradation pathway of B. subtilis. The gene-enzyme relationships of the pathway are given in Fig. 1. The guanine deaminase (gde)-catalyzed step has been identified by Nygaard and coworkers (30), and the urease-encoding ure operon was found by Wray and coworkers (49).

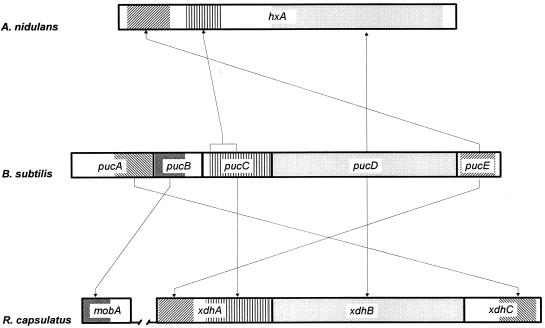

All the genes of the pucABCDE operon were found to be essential for xanthine dehydrogenase activity in B. subtilis. PucD is a 745-amino-acid peptide that has amino acid sequence identity to the XdhB subunit of xanthine dehydrogenase of Rhodobacter capsulatus (20) and to the C-terminal part of the 1,365-amino-acid multidomain xanthine dehydrogenase polypeptide found in A. nidulans (16) and in many other eukaryotic organisms, including Homo sapiens (51). We therefore suggest that PucD consists of the subunit of B. subtilis xanthine dehydrogenase that binds the substrate xanthine and the molybdenum cofactor. pucE and pucC both encode polypeptides with amino acid sequence identity to subunits of different dehydrogenases (2, 15, 40). The function of these subunits is to bind essential prosthetic groups like [2Fe-2S] clusters and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) involved in the oxidation reaction catalyzed by the dehydrogenase holoenzymes. In R. capsulatus, three genes, xdhA, xdhB, and xdhC, encode all functions required for xanthine dehydrogenase activity (20), whereas in A. nidulans, xanthine dehydrogenase is encoded by a single gene, hxA (16).

When the amino acid sequence of the pucABCDE gene products was compared to the deduced amino acid sequence of R. capsulatus xdhABC and to the A. nidulans protein, we were able to establish an alignment based on the organization of the different domains of the various xanthine dehydrogenases. As illustrated in Fig. 3, PucE and PucC have similarity to the N- and C-terminal part, respectively, of R. capsulatus XdhA xanthine dehydrogenase subunit and to the N-terminal part of A. nidulans HxA. XdhA and the N-terminal part of HxA have been shown to encode the binding domain for two [2Fe-2S] clusters and for FAD binding (20). From this alignment, we suggest that PucE is the [2Fe-2S] cluster-binding subunit of B. subtilis xanthine dehydrogenase and that PucC encodes the binding domain for the FAD cofactor. We therefore expect that both PucE and PucC are subunits of the xanthine dehydrogenase in B. subtilis. While the functional domains of PucE ([2Fe-2S] binding) and PucC (FAD binding) are encoded by separate genes in B. subtilis, they are fused in R. capsulatus and A. nidulans. The xdhC gene product of R. capsulatus is required for proper insertion of the molybdopterin cofactor in to the XdhB subunit (21). As illustrated in Fig. 3, B. subtilis PucA and XdhC show amino acid identity (22%) in their C-terminal half. This could indicate that PucA exerts an XdhC-like molybdenum cofactor recruiting function in B. subtilis. Finally, we found that PucB of B. subtilis and MobA from R. capsulatus show amino acid sequence identity (26%) in their N-terminal half. mobA in R. capsulatus encodes an enzyme required for the synthesis of the molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide cofactor—a modified form of molybdopterin cofactor. The gene is not linked to the xdhABC operon (22). PucB has the same similarity to the MobA homolog in B. subtilis (19). Since pucB is coexpressed with genes that encode subunits of xanthine dehydrogenase and since disruption of pucB results in the loss of xanthine dehydrogenase activity, it is tempting to suggest that the pucB gene product is involved in formation of the molybdenum cofactor required by xanthine dehydrogenase. This cofactor derivative may very well be different from the molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide cofactor, which is the product formed by the mobA-encoded molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide synthase.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the xanthine dehydrogenase-encoding genes of the prokaryotes B. subtilis and R. capsulatus and the eukaryote A. nidulans. Various segments of the reading frames are highlighted in order to indicate a certain functional domain of the protein. The domains are xanthine and molybdenum cofactor binding domain (light shading), [2Fe-2S] cluster binding domain (Z hatching), and FAD binding domain (striped). The other highlighted segments indicate amino acid sequences that are similar among the aligned reading frames and encode the following putative functions: putative molybdenum cofactor recruiting function (S hatching) and putative molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis function (dark shading). Arrows pointing from the B. subtilis reading frames indicate the localization of the corresponding amino acid segments in R. capsulatus and A. nidulans. The bracket above pucC shows that only a restricted segment is similar to the corresponding hxA segment.

The pucJKLM operon encodes functions required for uric acid uptake and oxidation. The high degree of amino acid sequence identity between PucJ, PucK, and the pbuX-encoded xanthine permease of B. subtilis (4) strongly indicates a transport function for these proteins. Even though strains that harbor a disrupted copy of pucJ or pucK contain uricase activity, they still showed a reduced capacity for uric acid utilization (Table 2) and excreted uric acid, which could be explained by a partial uric acid transport deficiency. It is interesting that B. subtilis has two highly similar transporters (50% identity) devoted to uric acid uptake. The membrane-embedded PbuX-type of transporter promotes facilitated diffusion of purine and pyrimidine bases (4). Facilitated diffusion requires that the imported molecules be instantly metabolized in order to sustain a suitable concentration gradient over the membrane. Accumulation of uric acid intracellularly is not preferable because of its low solubility. Therefore uric acid is most likely immediately converted to allantoin by uricase. Two genes, pucL and pucM, encode functions required for uricase activity in B. subtilis (Table 3). As mentioned above, PucL shows amino acid sequence identity to several uricases. However, the similarity to known uricases starts at amino acid position 171, which is a methionine residue. Inspection of the nucleotide sequence located 7 bp upstream of methionine 171 reveals a sequence (5′-GGAGAGA-3′) that resembles a ribosome-binding site. Four nucleotides upstream of this putative ribosome-binding site, a translational stop signal (UGA) is located. So, insertion or deletion of nucleotides upstream of this potential stop codon could result in two separate reading frames, of which the reading frame from amino acids 171 to 494 encodes a sequence highly similar to uricase from Bacillus sp. strain TB-90 (54) and A. nidulans (32). Furthermore, the calculated molecular mass (36.8 kDa) of the putative peptide encoded by residues 171 to 494 is similar to the subunit size of Bacillus fastidiosus uricase (3). The N-terminal part (amino acids 1 to 170) of PucL show amino acid sequence identity to similar-sized reading frames in Deinococcus radiodurans (accession no. AAF10731), Streptomyces coelicolor (accession no. CAB36617), and the ahpG-encoded polypeptide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (accession no. S70169). M. tuberculosis AhpC is an alkyl hydroxyperoxide reductase that cleaves reactive oxygen intermediates (10). We therefore speculate that the N-terminal part of PucL might encode peroxide reductase activity that is involved in the removal of toxic hydrogen peroxide formed in the uricase-catalyzed oxidation of uric acid to allantoin. Whether the putative reductase domain and the uricase domain are placed on the same polypeptide or whether they are encoded by separate reading frames remains to be tested.

Inactivation of the pucM gene also resulted in a uricase-defective phenotype (Tables 2 and 3). PucM shows amino acid sequence identity to the extracellular transthyretin (prealbumin) thyroid hormone-binding protein from several eukaryotic organisms. PucM-like reading frames are also found in many prokaryotes. At the moment we do not know the role of this gene product in uric acid oxidation in B. subtilis. One suggestion could be that PucM is involved in the formation of some sort of superstructure comprising the transporters, the uricase, and the peroxide reductase subunits and that correct assembly of this structure is required for wild-type uricase activity.

The pucFG operon encodes functions responsible for the conversion of allantoic acid to urea. As documented in this report (Tables 2 and 3) and also suggested earlier (49), B. subtilis degrades allantoic acid by the allantoate amidohydrolase pathway, resulting in formation of ureidoglycolic acid and 2 mol of ammonia and not by the allantoicase pathway found in S. cerevisiae (5), which results in the formation of ureidoglycolic acid and 1 mol of urea. We demonstrated that pucF encodes allantoate amidohydrolase and that PucF showed significant (47%) amino acid sequence identity to E. coli allantoate amidohydrolase encoded by allC (8). In E. coli and S. cerevisiae, the final conversion of ureidoglycolic acid to glyoxylate and urea is catalyzed by ureidoglycolase. The ureidoglycolase of E. coli (8) and S. cerevisiae (55) is encoded by allA and dal3, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences of the two gene products (AllA is 160 and DAL3 is 195 amino acids) show 29% sequence identity. A pucG mutant grows slowly with allantoin or allantoic acid as the sole nitrogen source (Table 2); however, utilization of ureidoglycolic acid as a nitrogen source was not impaired. The same kind of conflicting results were obtained with an E. coli allA mutant defective in ureidoglycolase (8). This mutant contains a defective allA gene but could still utilize allantoin as the sole nitrogen source. E. coli and S. cerevisiae ureidoglycolases belong to the same enzyme family indicated above; however, B. subtilis PucG (416 amino acids) shows no amino acid sequence identity to AllA or DAL3. PucG shows extensive amino acid sequence similarity (29% over 393 amino acids) to the 392-amino-acid human l-alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase, which is located in liver cell peroxisomes, where it is involved in glyoxylate detoxification by catalyzing the reaction l-alanine + glyoxylate → pyruvate + glycine (34). Our current working hypothesis is that pucG encodes ureidoglycolase or l-alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase or perhaps both activities.

Finally, we can suggest a function for the pucR gene product. PucR is most likely a transcriptional activator involved in the induction of the purine degradation pathway. Allantoin, allantoic acid, and uric acid were all found to act as true inducer molecules. When aligned with amino acid sequences in the databases, limited sequence identity to hypothetical proteins from various organisms was detected. Many of these show identity to regulatory proteins. Two entries with a known function (Streptomyces ambofaciens SrmR and E. coli SdaR) were recorded. Both proteins have been identified as transcriptional activators. SrmR activates genes involved in macrolide biosynthesis (14), and SdaR activates transcription of genes involved in d-galactarate and d-glucarate metabolism (28). Amino acid sequence similarity among PucR, SrmR, and SdaR is limited to the C-terminal residues. Furthermore, when aligned with the consensus sequence of the DNA-binding domain of the LysR-like family of transcriptional regulators (38), the number of conserved amino acids in PucR, SrmR, and SdaR indicates that these regulators may contain a LysR-like DNA-binding domain. However, neither SrmR nor SdaR has been analyzed for the localization of their DNA-binding domains. PucR resamples LysR regulators in that (i) the pucR gene is transcribed from a promoter that overlaps a divergently oriented promoter of one of the regulated target genes (pucH) and (ii) PucR represses its own synthesis. Due to the lack of similarity to other classes of regulatory proteins, we suggest that PucR and perhaps SrmR and SdaR may define a new class of transcription factors.

Analysis of the expression of the different puc-lacZ fusions revealed that the expression level was very low in excess nitrogen (ammonia plus glutamate) and was induced during limiting-nitrogen conditions (glutamate). When allantoin or allantoic acid was added during limiting-nitrogen conditions pucH, pucJKLM, pucFG, and pucI expression was further induced. The same expression pattern was also reported for gde (guanine deaminase) expression (30). The pucR strain BFA2277 exhibits very low levels of guanine deaminase during growth with glutamate plus allantoin. This indicates that the putative pathway-specific activator of gde expression suggested by Nygaard and coworkers (30) is PucR. Nygaard and coworkers also demonstrated that gde expression could not be induced in a tnrA genetic background (30). During limiting-nitrogen conditions, we have found that a tnrA mutant strain cannot use purines or intermediates of the purine catabolic pathway as the sole nitrogen source (data not given). These results indicate that TnrA is involved in the activation of puc gene expression during nitrogen-limiting conditions. TnrA is also the activator of nrgAB, ure, gabP, nasA, and nasBCDEF transcription during nitrogen-limiting conditions (48). In contrast to the purine catabolic genes, these genes are expressed constitutively during nitrogen-limiting conditions. We suggest that the reason for subjecting purine degradation to pathway-specific induction may be that constitutive high expression of this pathway could result in the drainage of purine bases for nucleotide synthesis and thereby reduce the capacity for nucleic acid synthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jenny Steno Christensen and Kirsten Hansen for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by EU contract BIO2-CT95-0278 and by Danish Natural Science Research Council grant 9901855. This project also received financial support from the Novo Nordisk Foundation and from the Saxild Family Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashihara H, Crozier A. Biosynthesis and metabolism of caffeine and related purine alkaloids in plants. Adv Bot Res. 2000;30:117–205. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blase M, Bruntner C, Tshisuaka B, Fetzner S, Lingens F. Cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of the three genes encoding quinoline 2-oxidoreductase, a molybdenum-containing hydroxylase from Pseudomonas putida86. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23068–23079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bongaerts G P, Uitzetter J, Brouns R, Vogels G D. Uricase of Bacillus fastidiosus: properties and regulation of synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;527:348–358. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(78)90349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christiansen L C, Schou S, Nygaard P, Saxild H H. Xanthine metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of the xpt-pbuXoperon and evidence for purine- and nitrogen-controlled expression of genes involved in xanthine salvage and catabolism. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2540–2550. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2540-2550.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper T G. Regulation of allantoin catabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Brambl R, Marzluf G A, editors. The mycota III: biochemistry and molecular biology. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper T G, Chisholm V T, Cho H J, Yoo H S. Allantoin transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis regulated by two induction systems. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4660–4667. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4660-4667.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Ramos H, Glaser P, Wray L V, Jr, Fisher S H. The Bacillus subtilis ureABCoperon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3371–3373. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3371-3373.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusa E, Obradors N, Baldoma L, Badia J, Aguilar J. Genetic analysis of a chromosomal region containing genes required for assimilation of allantoin nitrogen and linked glyoxylate metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7479–7484. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7479-7484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMoll E, Auffenberg T. Purine metabolism in Methanococcus vannielii. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5754–5761. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5754-5761.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deretic V, Philipp W, Dhandayuthapani S, Mudd M H, Curcic R, Garbe T, Heym B, Via L E, Cole S T. Mycobacterium tuberculosisis a natural mutant with an inactivated oxidative-stress regulatory gene: implications for sensitivity to isoniazid. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:889–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diallinas G, Scazzocchio C. A gene coding for the uric acid-xanthine permease of Aspergillus nidulans: inactivational cloning, characterization, and sequence of a cis-acting mutation. Genetics. 1989;122:341–350. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher S H. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: vive la difference! Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:223–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiwara S, Noguchi T. Degradation of purines: only ureidoglycollate lyase out of four allantoin-degrading enzymes is present in mammals. Biochem J. 1995;312:315–318. doi: 10.1042/bj3120315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geistlich M, Losick R, Turner J R, Rao R N. Characterization of a novel regulatory gene governing the expression of a polyketide synthase gene in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2019–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson J, Dispensa M, Harwood C S. 4-Hydroxybenzoyl coenzyme A reductase (dehydroxylating) is required for anaerobic degradation of 4-hydroxybenzoate by Rhodopseudomonas palustrisand shares features with molybdenum-containing hydroxylases. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:634–642. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.634-642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glatigny A, Scazzocchio C. Cloning and molecular characterization of hxA, the gene coding for the xanthine dehydrogenase (purine hydroxylase I) of Aspergillus nidulans. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3534–3550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi S, Jain S, Chu R, Alvares K, Xu B, Erfurth F, Usuda N, Rao M S, Reddy S K, Noguchi T. Amphibian allantoinase: molecular cloning, tissue distribution, and functional expression. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12269–12276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keilin J. The biological significance of uric acid and guanine excretion. Biol Rev. 1959;34:265–296. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leimkuhler S, Kern M, Solomon P S, McEwan A G, Schwarz G, Mendel R R, Klipp W. Xanthine dehydrogenase from the phototrophic purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatusis more similar to its eukaryotic counterparts than to prokaryotic molybdenum enzymes. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:853–869. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leimkuhler S, Klipp W. Role of XdhC in molybdenum cofactor insertion into xanthine dehydrogenase of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2745–2751. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2745-2751.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leimkuhler S, Klipp W. The molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein MobA from Rhodobacter capsulatusis required for the activity of molybdenum enzymes containing MGD, but not for xanthine dehydrogenase harboring the MPT cofactor. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marzluf G A. Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:17–32. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.17-32.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto H, Ohta S, Kobayashi R, Terawaki Y. Chromosomal location of genes participating in the degradation of purines in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;167:165–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00266910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maynes J T, Yuan R G, Snyder F F. Identification, expression, and characterization of Escherichia coliguanine deaminase. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4658–4660. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4658-4660.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendel R R, Schwarz G. Molybdoenzymes and molybdenum cofactor in plants. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1999;18:33–69. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mommsen T P, Walsh P J. Biochemical and environmental perspectives on nitrogen metabolism in fishes. Experientia. 1992;48:583–593. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monterrubio R, Baldoma L, Obradors N, Aguilar J, Badia J. A common regulator for the operons encoding the enzymes involved in d-galactarate, d-glucarate, and d-glycerate utilization in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2672–2674. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2672-2674.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nygaard P. Utilization of preformed purine bases and nucleosides. In: Munch-Petersen A, editor. Metabolism of nucleotides, nucleosides and nucleobases in microorganisms. London, U.K: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 27–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nygaard P, Bested S M, Andersen K A K, Saxild H H. Bacillus subtilis guanine deaminase is encoded by the yknAgene and is induced during growth with purines as the nitrogen source. Microbiology. 2000;146:3061–3069. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-12-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nygaard P, Duckert P, Saxild H H. Role of adenine deaminase in purine salvage and nitrogen metabolism and characterization of the ade gene in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:846–853. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.846-853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oestreicher N, Scazzocchio C. Sequence, regulation, and mutational analysis of the gene encoding urate oxidase in Aspergillus nidulans. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23382–23389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pineda M, Piedras P, Cardenas J. A continuous spectrophotometric assay for ureidoglycolase activity with lactate dehydrogenase or glyoxylate reductase as coupling enzyme. Anal Biochem. 1994;222:450–455. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purdue P E, Lumb M J, Fox M, Griffo G, Hamon-Benais C, Povey S, Danpure C J. Characterization and chromosomal mapping of a genomic clone encoding human alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase. Genomics. 1991;10:34–42. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90481-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouf M A, Lomprey R F. Degradation of uric acid by certain aerobic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:617–622. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.3.617-622.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saxild H H, Andersen L N, Hammer K. dra-nupC-pdp operon of Bacillus subtilis: nucleotide sequence, induction by deoxyribonucleosides, and transcriptional regulation by the deoR-encoded DeoR repressor protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:424–434. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.424-434.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scazzocehio C, Darlington A J. The induction and repression of the enzymes of purine breakdown in Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;166:557–568. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(68)90243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schell M A. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreier H J, Rostkowski C A, Kellner E M. Altered regulation of the glnRA operon in a Bacillus subtilismutant that produces methionine sulfoximine-tolerant glutamine synthetase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:892–897. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.892-897.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schubel U, Kraut M, Morsdorf G, Meyer O. Molecular characterization of the gene cluster coxMSL encoding the molybdenum-containing carbon monoxide dehydrogenase of Oligotropha carboxidovorans. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2197–2203. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2197-2203.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schubert K R, Boland M J. The ureides. In: Stumph P K, Cohn E E, editors. The biochemistry of plants. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 197–282. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suarez T, de Queiroz M V, Oestreicher N, Scazzocchio C. The sequence and binding specificity of UaY, the specific regulator of the purine utilization pathway in Aspergillus nidulans, suggest an evolutionary relationship with the PPR1 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:1453–1467. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suarez T, Oestreicher N, Kelly J, Ong G, Sankarsingh T, Scazzocchio C. The uaY positive control gene of Aspergillus nidulans: fine structure, isolation of constitutive mutants and reversion patterns. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:359–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00280292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suarez T, Oestreicher N, Penalva M A, Scazzocchio C. Molecular cloning of the uaY regulatory gene of Aspergillus nidulansreveals a favored region for DNA insertions. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:369–375. doi: 10.1007/BF00280293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich D. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1998;144:3097–3104. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogels G D, van der Drift C. Degradation of purines and pyrimidines by microorganisms. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:403–469. doi: 10.1128/br.40.2.403-468.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogels G D, van der Drift C. Differential analyses of glyoxylate derivatives. Anal Biochem. 1970;33:143–157. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wray L V, Jr, Ferson A E, Rohrer K, Fisher S H. TnrA, a transcription factor required for global nitrogen regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;165:349–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wray L V, Jr, Ferson A E, Fisher S H. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis ureABCoperon is controlled by multiple regulatory factors including CodY, GlnR, TnrA, and Spo0H. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5494–5501. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5494-5501.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wray L V, Jr, Zalieckas J M, Fisher S H. Purification and in vitro activities of the Bacillus subtilisTnrA transcription factor. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:29–40. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wright R M, Vaitaitis G M, Wilson C M, Repine T B, Terada L S, Repine J E. cDNA cloning, characterization, and tissue-specific expression of human xanthine dehydrogenase/xanthine oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10690–10694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X W, Lee C C, Muzny D M, Caskey C T. Urate oxidase: primary structure and evolutionary implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9412–9416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xi H, Schneider B L, Reitzer L. Purine catabolism in Escherichia coliand function of xanthine dehydrogenase in purine salvage. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5332–5341. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.19.5332-5341.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto K, Kojima Y, Kikuchi T, Shigyo T, Sugihara K, Takashio M, Emi S. Nucleotide sequence of the uricase gene from Bacillussp. TB-90. J Biochem. 1996;119:80–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoo H S, Cooper T G. The ureidoglycollate hydrolase (DAL3) gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1991;7:693–698. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeng X, Saxild H H. Identification and characterization of a DeoR-specific operator sequence essential for induction of dra-nupC-pdp operon expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1719–1727. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1719-1727.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]