Abstract

Fungi are a prolific source of bioactive molecules. During the past few decades, many bioactive natural products have been isolated from marine fungi. Chile is a country with 6435 Km of coastline along the Pacific Ocean and houses a unique fungal biodiversity. This review summarizes the field of fungal natural products isolated from Antarctic and Chilean marine environments and their biological activities.

Keywords: marine natural products, marine fungi, Chilean marine fungi, biological activities

1. Introduction

Natural products (NPs) represent a rich and vast biologically relevant chemical space that remains extremely difficult to access with the current arsenal of tools in chemical synthesis [1]. NPs are characterized by enormous scaffold diversity and structural complexity. Nature, via evolution, has optimized secondary metabolites to serve pivotal biological functions, including endogenous defense mechanisms as well as interaction with other organisms [2]. Natural products-based medicines can be traced back thousands of years and still contribute to many approved drugs. Indeed, natural products and their derivatives represented 27% of all therapeutics approved by the FDA between 1981 and 2019 [3,4]. In recent years, this proportion has increased, illustrating the continued importance of NPs. Research programs focused on unveiling new NPs from understudied microorganisms, such as fungi isolated from Chilean marine environments, are crucial to the future drug development pipeline.

Fungi represent one of the largest groups of organisms. They are widely distributed across both mild and extreme ecosystems on our planet [5]. They have developed a unique metabolic plasticity, allowing them to rapidly adapt and survive through the biosynthesis of an array of fascinating natural products [6]. A recent analysis of fungal genomes has revealed many secondary metabolite pathways that can be tuned or modified, producing novel and valuable chemical scaffolds [7]. Fungal-derived natural products are pharmaceutically abundant, with several important biological applications ranging from highly potent toxins to approved drugs [8]. Since the discovery of penicillin, an antibiotic of fungal origin, many efforts around the globe have been devoted to searching for fungal-derived bioactive products. Fungi are a vast yet untapped source to search for pharmaceutically relevant molecules displaying a range of bioactivity, including anti-cancer, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antibacterial, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory capabilities.

Oceans are the source of a wide variety of natural products with unique structures mainly produced by marine macro-organisms, such as invertebrates (e.g., sponges, soft corals, tunicates) and algae. Additionally, many marine natural products have proved to be pharmacologically relevant [9,10,11].

Secondary metabolites obtained from marine fungi have been particularly interesting, mainly because of their unique chemical structures and biomedical applications [8,12]. In 1949, cephalosporin C was discovered from a culture of Cephalosporium fungus species obtained from the Sardinian coast [13]. Since then, extensive efforts over decades of work have revealed the vast chemical and biological potential of marine fungal natural products. Strains of marine fungi have been obtained from practically every possible marine habitat, including inorganic, marine microbial communities, marine plants, and marine vertebrates [10]. While the number of cultivable marine fungi is extremely low (1% or less) compared to their global biodiversity [8,9,10], the number of natural products that have been isolated and characterized from marine fungi exceeds 1000 molecules [14]. These include alkaloids, lipids, peptides, polyketides, prenylated polyketides, and terpenoids [14,15,16,17].

Chile has 6435 km of coastline and exercises exclusive rights over its maritime space called the Chilean Sea. This comprises four zones: the Territorial Sea (120,827 km2), the contiguous zone (131,669 km2), the exclusive economic zone (3,681,989 km2), and that corresponding to the Continental shelf (161,338 km2) [18].

The Chilean maritime territory, in the Pacific Ocean, consists of highly structured geographic sections displaying unique features that arise from the interactions of water masses with the seabed, emerged relief, air masses and centers of atmospheric action [19]. These phenomena lead to an environment suitable for a rich biodiversity ranging from microscopic organisms that swarm the waters in incredible numbers to large fish and other organisms [20]. Along the lengthy coastline, Chilean waters also differ in terms of important characteristics, e.g., mineral and saline composition [19].

The cold waters associated with both the Humboldt and Antarctic currents are characterized by a high gas and nitrogen content, unlike in temperate and warm waters. Consequently, phytoplankton is abundant in the Chilean sea and supports the growth of various marine organisms, specifically fungi. Therefore, Chile´s coastline provides a distinct environment for fungal biodiversity to flourish [21].

Despite its importance, there are not many reports about secondary metabolites from marine fungi or marine-derived fungi in Chile. Reports included in this review cover the period from 1996 until present. In this work, we have made a comprehensive review of compounds that have been isolated and chemically characterized during this time. Their biological activities are also reported.

2. Secondary Metabolites Isolated from Chilean Marine Fungi in Continental Coasts

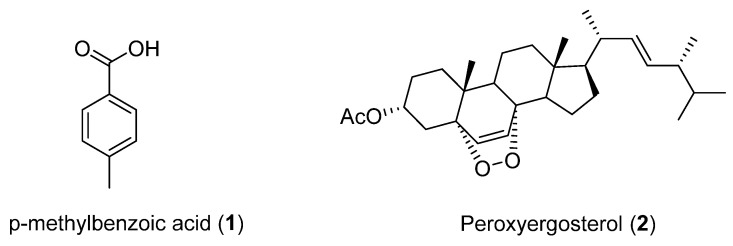

Studies carried out on cultures of Cladosporium cladosporioides, a fungus isolated from the marine sponge Cliona sp. collected in Region IV of Chile in 2004, led to the identification of p-methylbenzoic acid (1) and peroxyergosterol (2) (Figure 1). This was the first time that 1 had been isolated as a natural product. It was reported that peroxyergosterol from Inonotus obliquus inhibited the growth of cancer cells and showed cytotoxic effects on the same cell lines. Additionally, peroxyergosterol displayed potent inhibition of lipid peroxidation and higher antioxidant activity than well-known antioxidants, such as α-tocopherol and thiourea. A recent study also revealed inhibitory effects of peroxyergosterol on inflammation and tumor promotion in mouse skin [22]. In addition, compounds 1 and 2 did not show antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis) or Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecalis) in the agar plate diffusion assay. Both compounds were inactive against Artemia salina [23].

Figure 1.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Cladosporium cladosporioides.

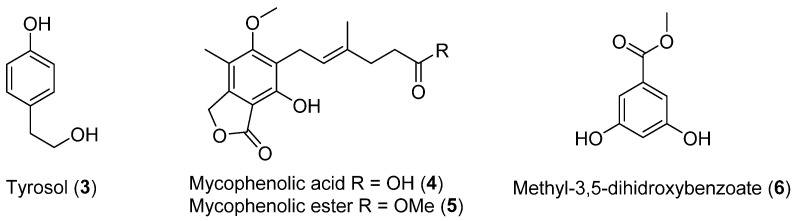

Four previously reported metabolites (3–6, Figure 2) were isolated from Penicillium brevicompactun, collected in Quintay, Chile (region V). The mycelium and broth were extracted with ethyl acetate, and the solvent was evaporated to provide a crude extract that showed in vitro antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecalis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [24].

Figure 2.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Penicillium brevicompactun.

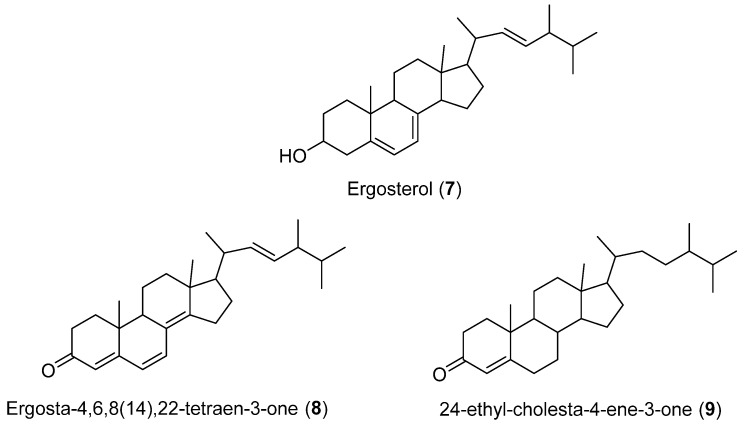

Four steroids (2, 7–9) (Figure 1 and Figure 3) were isolated from cultures of Geotrichum sp., a fungus obtained from marine sediment collected in Concepción Bay, Chile (Region VIII). Compound 7 is commonly found in fungal extracts since it plays a structural role in the cytoplasmic membrane. Similarly, 2 is a ubiquitous NP present in a variety of lichens, fungi, sponges, and marine organisms. Compound 8 has been isolated from Lampteromyces japonicus and a luminous bacterium. Additionally, 8 has been found in non-luminous basidiomycete fungi, including Fomes officinalis and Scleroderma polyrhizum. It has also been isolated from a marine sponge Dictyonella incisa [25]. This is the first time this compound has been identified in a facultative marine fungus [26].

Figure 3.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Geotrichum sp.

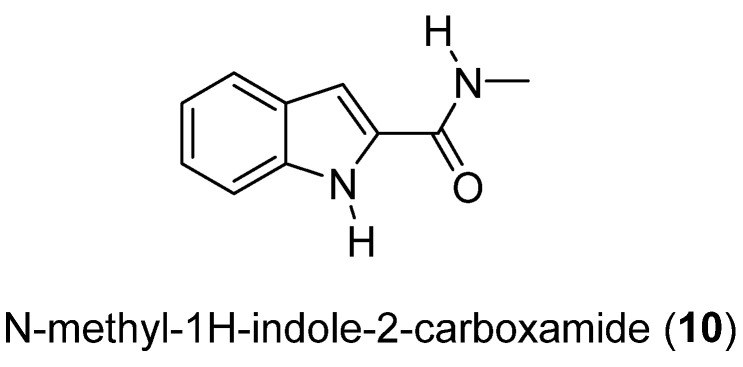

Compound 10 is the first indole derivative isolated from a marine fungus (Cladosporium cladosorioides). The crystal structure of N-methyl-1H-indole-2-carboxamide (10) (Figure 4) was determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction [27].

Figure 4.

Secondary metabolite isolated from Cladosporium cladosorioides.

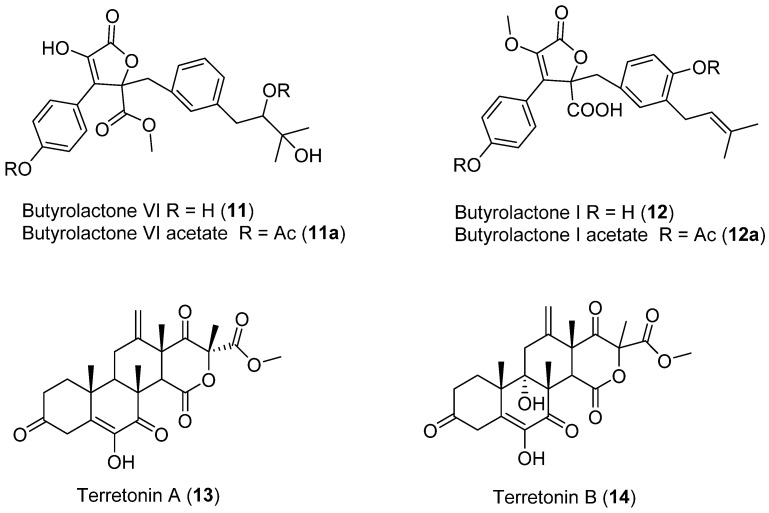

Two dibenzylbutyrolactones (11,12) (Figure 5) and two sesterterpenoids (13,14) (Figure 5) were obtained from Aspergillus sp. (2P-22) isolated from the marine sponge, Cliona chilensis collected in Los Molles, Chile (Region IV) [28]. Spectroscopic data highlighted compound 11 as a novel compound named butylrolactone-VI. All four compounds were then tested for antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (Clavibacter michiganensis 807) and Gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas syringae pv syringae, Xanthomonas arboricola pv juglandis 833, Erwinia carotovora, Agrobacterium tumefaciens A348), vasorelaxant effects, and antitumor bioactivities employing a broth culture of A. tumefaciens [28].

Figure 5.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Aspergillus sp.

3. Secondary Metabolites Isolated from Antarctic Marine Fungi

The Antarctic continent represents one of the most extreme environments on earth for life to exist [29]. This ecosystem is characterized by high-stress conditions, including low temperatures, scarce availability of nutrients, high acidity, and high levels of ultra-violet radiation [30]. In order to survive under these highly demanding conditions, fungi living in the Antarctic have had to adapt their biochemical machinery and have done so through modifications in gene expression as well as the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. Thus, Antarctic fungi represent a unique, biologically relevant chemical space with tremendous potential to contribute to the development of effective therapeutics [31]. Indeed, a number of efforts have reported unique NPs isolated from fungi living in Antarctic environments [31] and this emerging field promises a vast capacity for expansion.

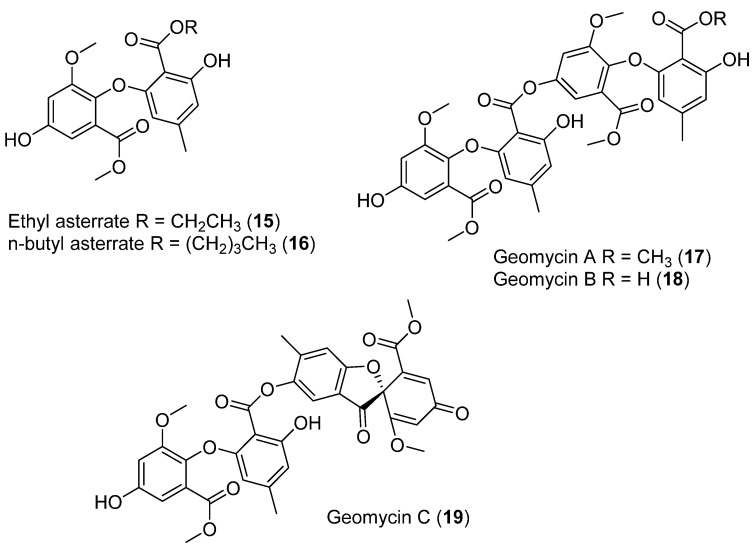

In cold marine ecosystems, the presence of fungi has been associated with macroalgae and invertebrates, although some species have also been recorded in seawater and sediments [32,33]. Five new asterric acid derivatives were identified and isolated from the fermentation of the Antarctic ascomycete Geomyces sp.: ethyl asterrate (15) (Figure 6), n-butyl asterrate (16) (Figure 6), and geomycins A–C (17–19) (Figure 6). These compounds were evaluated for antifungal and antibacterial properties. Geomycin B (18) showed significant activity against Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 10894, with IC50/MIC values of 0.86/29.5 µM, indicating much higher antifungal activity than the positive control fluconazole, which showed IC50/MIC values of 7.35/163.4 µM [31,34].

Figure 6.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Geomyces sp.

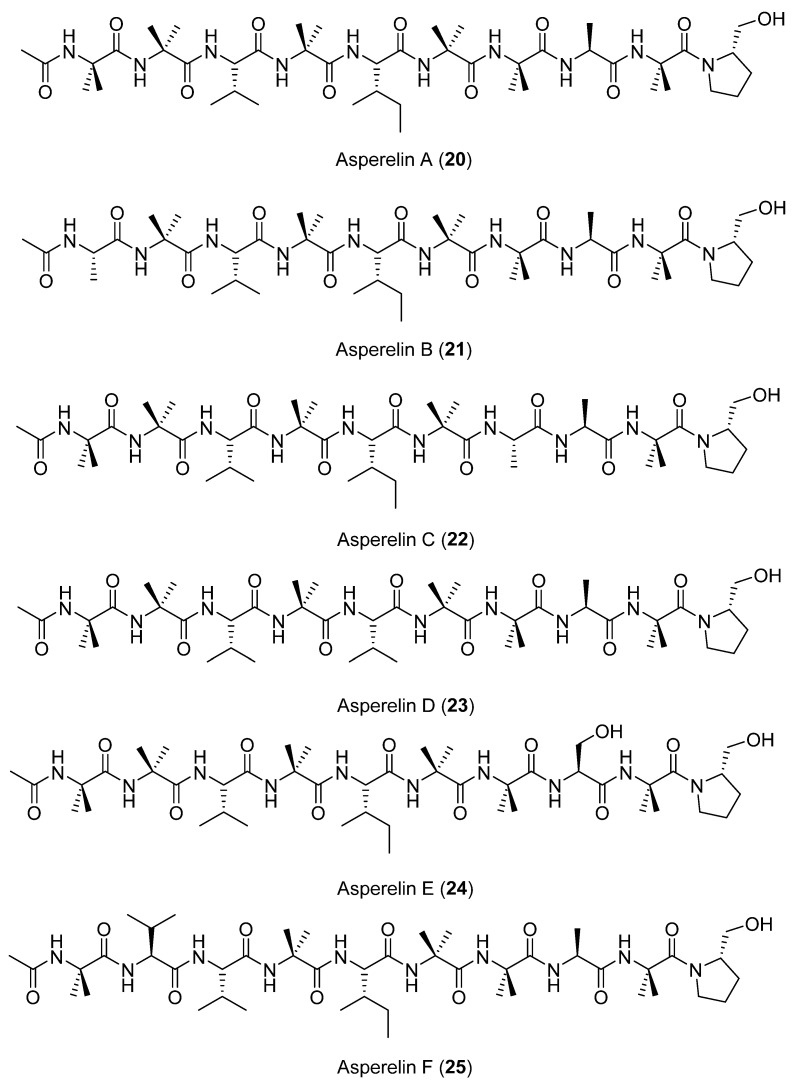

Six new peptaibols (linear or cyclic peptides), named asperelines A–F (20–25) (Figure 7), were characterized from the fermentation of the marine-derived fungus Tridocherma asperellum collected from the sediment of the Antarctic Penguin Island. Chemical structures were determined using 1D and 2D NMR techniques as well as ESIMS/MS [35].

Figure 7.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Tridocherma asperellum.

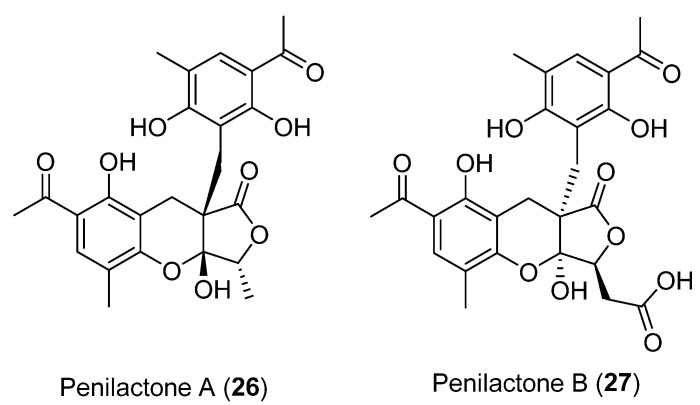

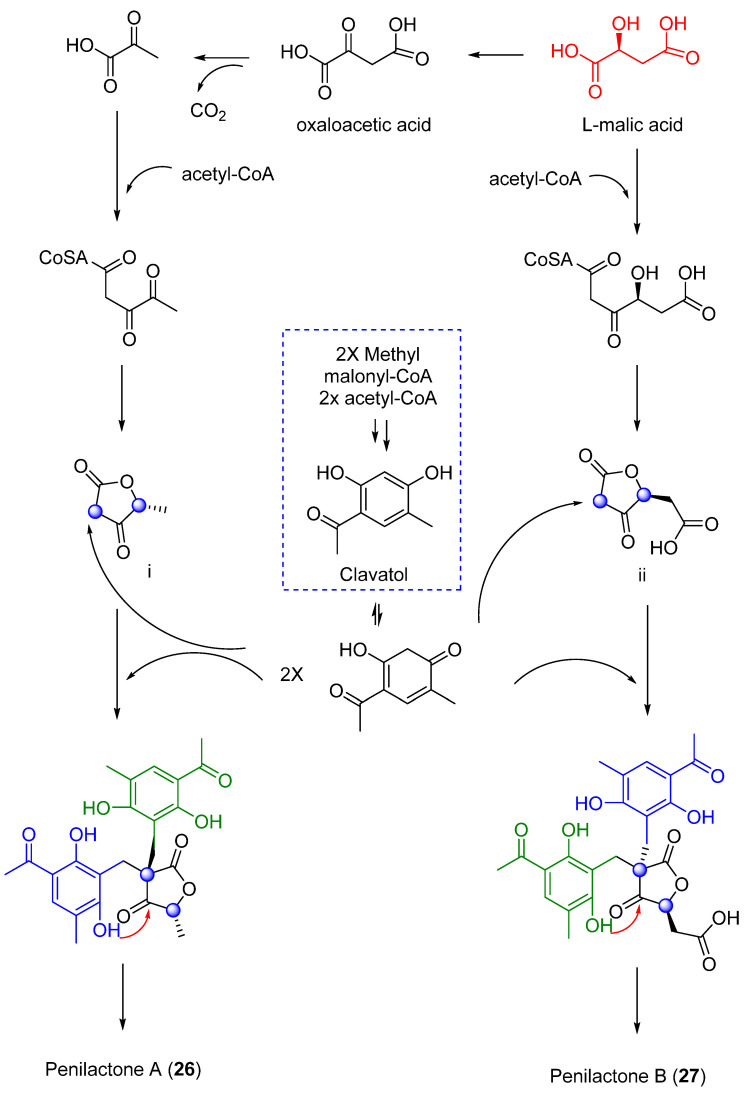

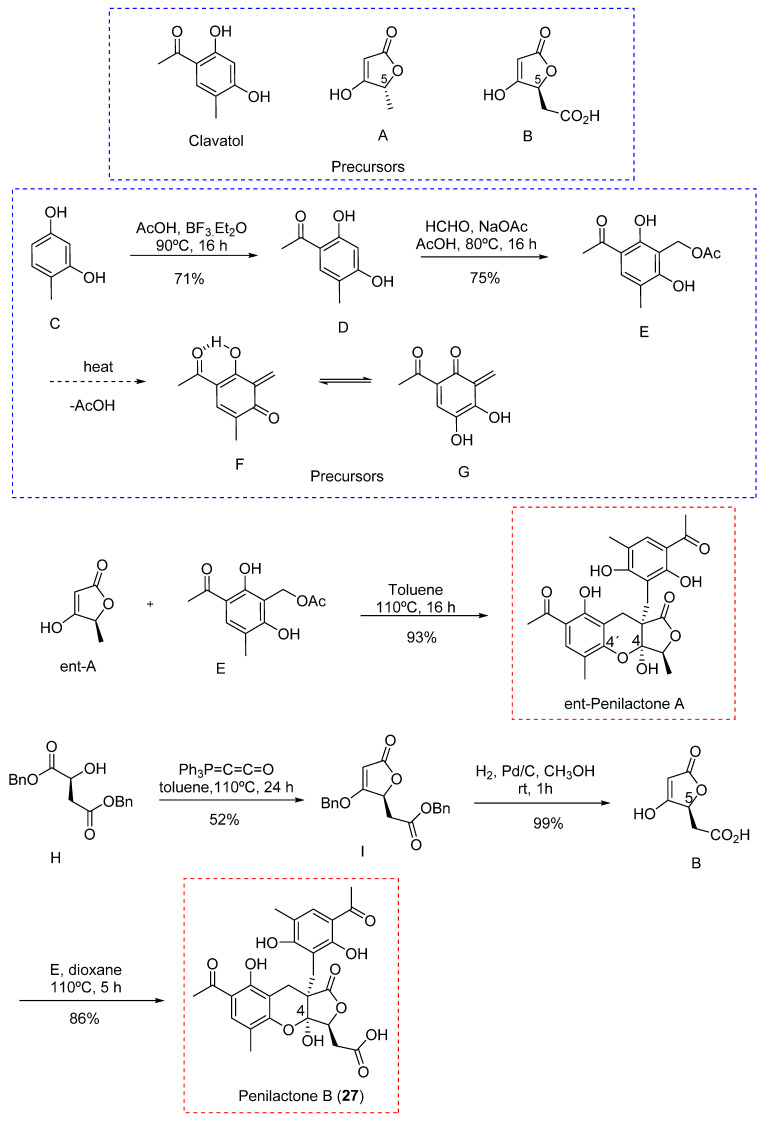

Next, two highly oxygenated polyketides, penylactones A and B (26 and 27) (Figure 8) were isolated and identified from Penicillium crustosum PRB-2. These compounds had a similar chemical structure but opposite absolute stereochemistry. Compounds 26 and 27 were tested for their ability to inhibit nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) via transient transfection and reporter gene expression assays. Of the two compounds, only 27 showed inhibitory activity with a relatively weak effect of 40% inhibitory rate at a concentration of 10 µM [36]. The authors also proposed a biosynthetic pathway for both compounds, shown in Scheme 1 [36]. These penylactones are characterized by a new carbon skeleton formed from two units of 3,5-dimethyl-2,4-diol-acetophenone and γ-butyrolactone. Six compounds were subsequently synthesized through a novel biomimetic synthesis pathway, as shown in Scheme 2 [37].

Figure 8.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Penicillium crustosum PRB-2.

Scheme 1.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway to 26 and 27.

Scheme 2.

Biomimetic synthesis of ent-Penilactone A and Penilactone B.

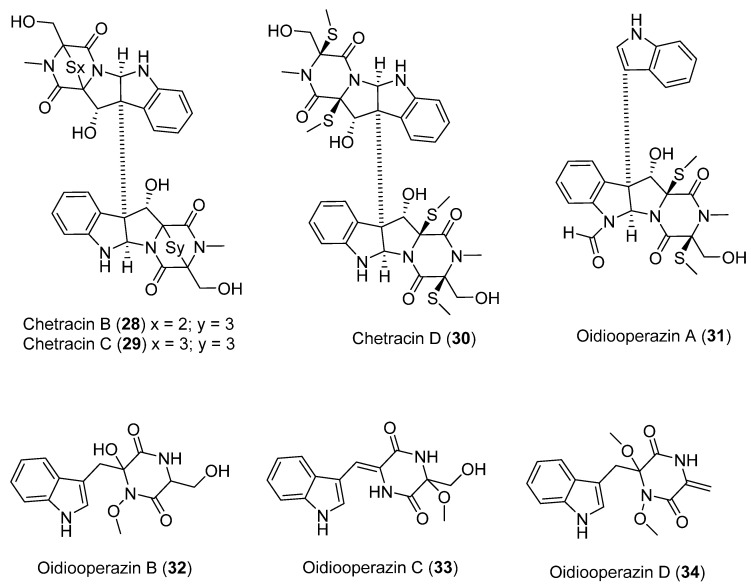

A study of the Antarctic fungus Oidiodendron truncatum GW3-13 isolated two new epipolythiodioxopiperazines, chetrazins B (28) and C (29), together with five new diketopiperazines, chetracin D (30), and oidiooperazines A–D (31–34) (Figure 9). In vitro studies using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) showed that compound 28 exhibits potent biological activity in the nanomolar range against a panel of five human cancer lines (HCT-8, BEL-7402, BGC-823, A-549, and A-2780) [38].

Figure 9.

Secondary metabolites isolated from the Antarctic fungus Oidiodendron truncatum.

In the same study, compounds 29 and 30 exhibited significant cytotoxicity at micromolar concentration. Finally, it was observed that compounds 31–34 did not show cytotoxicity at a concentration of 10 µM. This led to the conclusion that the sulfide bridge was a determining factor in the biological activity presented by these compounds. In contrast, the number of sulfur atoms in the bridge did not seem to influence the bioactivity [38].

Organic extracts of several fungi were isolated from samples of Porifera collected on King George Island. Although pure compounds could not be isolated, the presence of biological activities and potential as antimicrobial agents could be investigated. Antimicrobial activity was tested using strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25922, Clavibacter michiganensis 807, and Xanthomonas campestris 833. Antitumoral activity was assessed using Agrobacterium tumefaciens At348 as a model, and antioxidant activity was determined by comparing the absorbance of ascorbic acid obtained from each extract. Approximately 50% of the 101 extracts showed antibacterial activity against at least one of the bacteria tested, being more active against Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus. Moreover, 43 extracts showed 50% inhibition of crown gall tumor growth on potato. Antioxidant studies revealed that 97 fungal extracts displayed decent activities varying from very low to mild, and only three isolates showed high antioxidant activities [39].

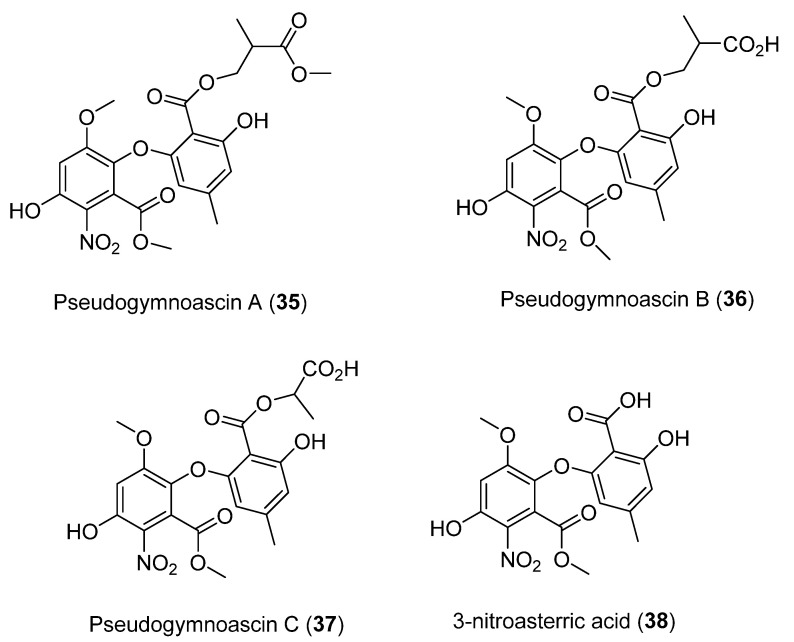

Four new compounds, namely Pseudogymnoascins A–C (35–37) and 3-nitroasterric acid (38) (Figure 10), were characterized from a culture of Pseudogymnoascus sp., obtained from an Antarctic marine sponge of the genus Hymeniacidon [40]. Remarkably, these compounds were the first nitro derivatives of asterric acid identified. The antimicrobial activity of compounds 35–38 was evaluated against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, Actinobacter baumannii CL5973, Escherichia coli MB2884, Staphylococcus aureus EP1167, and S. aureus MB5394. Their antifungal activity was also tested against Candida albicans MY1055, C. albicans ATCC64124, and Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC46645. Cytotoxicity against the tested microorganisms was not observed, suggesting that the presence of the nitro group in the structure may negatively influence the biological activity of these compounds [40].

Figure 10.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Pseudogymnoascus sp.

One hundred fungal strains were isolated from 55 samples of maritime Antarctic and classified into 35 fungal taxa within 20 genera. Extracts from these strains were tested against human tumoral cells, parasitic protozoa (Leishmania amazonensis, Trypanosoma cruzi), fungi, and bacteria. The extracts from Purpureocillum lilacinum displayed high trypanocidal, antibacterial, and antifungal activities with moderate toxicity over normal cells [41].

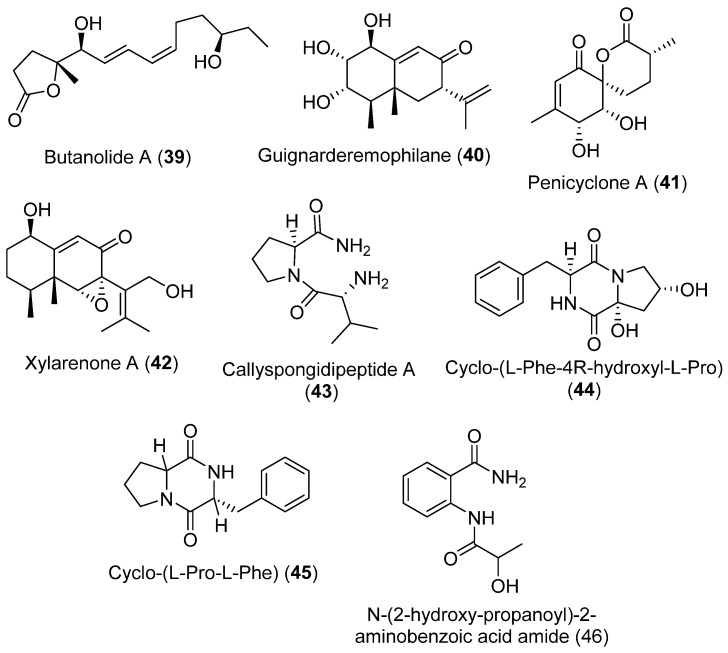

In recent years the chemical compounds of Penicillium sp. S-1-18 isolated from Antarctic seabed sediments has been extensively investigated. Butanolide A (39), a new furanone derivative, and guignarderemophilane F (40), a new sesquiterpene, together with six known compounds: penicyclone A (41), xylarenone A (42), callyspongidipeptide A (43), cyclo-(L-Phe-4R-hydroxyl-L-Pro) (44), cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Phe) (45), and N-(2-hydroxy-propanoyl)-2-aminobenzoic acid amide (46), were isolated (Figure 11). The structures of these metabolites were determined using 1D- and 2D-NMR spectroscopic methods. Inhibitory effects against PTP1B activity were tested for all compounds. Only compound 39 showed activity against PTP1B, which was moderate compared with the positive control oleanolic acid [42].

Figure 11.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Penicillium sp. S-1-18.

An interesting study of the distribution of marine fungi found that Pseudogymnoascus sp. and species of the genus Penicillium were present in all marine samples. Samples collected at 20 m or more in depth, at temperatures near 0 °C, had higher diversity those from the intertidal zone (superficial samples) [43].

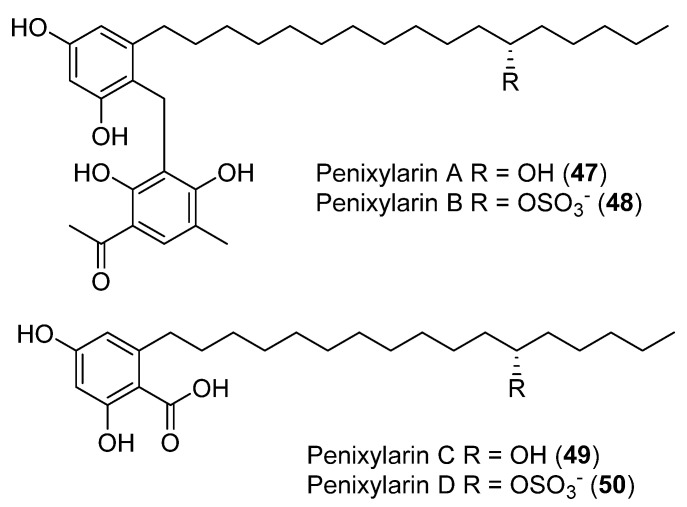

The antibacterial activity was assessed for four new compounds, Penixylarins A–D (47–50), obtained from a culture of the Antarctic fungus Penicillium crustosum PRB-2 and the mangrove-derive fungus Xylaria sp. HDN12-249 (Figure 12). Compounds 48 and 49 showed antibacterial activity against B. subtilis, M. phlei, and V. parahemolyticus. Compound 49 additionally displayed potential antituberculosis effects against Mycobacterium phlei [44].

Figure 12.

Penixylarins A–D, isolated from Penicillium crestosum PRB-2 and the fungus Xylaria sp. HDN12-249.

In a 2018 review, Tripathi et al. described more than two hundred natural products isolated from prokaryotes and eukaryotes living in polar regions, including fungi. Their pharmacology, relevant bioactivity, and chemical structures were reported in the review [45]. One year later, anticancer compounds were isolated from seaweed-derived endophytic fungi [46].

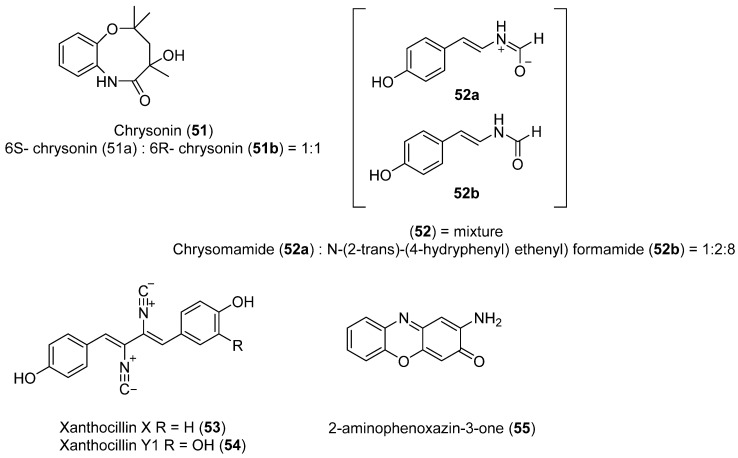

Using a different sampling strategy, pieces of excrement from Adelie penguins allowed the isolation of Penicillium chrysogenum. Although the sample was not collected from a marine environment per se, the feeding habits of the penguins support the idea that the microorganisms isolated are marine. The exact location of the sample collection site was not stated but is presumably near the Chinese Great Wall Antarctic base. A new compound Chrysonin (51) was obtained as a pair of enantiomers 6S- and 6R-chrysonin (51a and 51b) (Figure 13). These compounds display an eight-membered heterocycle fused with a benzene ring. Interestingly, there is no precedent of one natural compound with this structure. Compound 52 was also isolated as a mixture of a new zwitterionic compound chrysomamide (52a) and N-[2-trans-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethenyl] formamide (52b) (Figure 13). Compound 53, shown in Figure 13, contains the unusual isocyanide functional group. This functional group has been found in several marine organisms, such as cyanobacteria, Penicillium fungi, marine sponges, and nudibranchs. Furthermore, there is no precedent of one natural compound with an eight-membered heterocycle fused with a benzene ring. Antibacterial activity of each compound against eight microorganisms was determined. Compound 53 (Figure 13) was active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii. The same metabolite and compound 54 (Figure 13) both showed significant cytotoxicity against four cancer cell lines: A. baumannii ATCC 19606, E. coli ATCC 25922, M. luteus SCSIO MLO1, and MRSA, shhs-A1. Compound 55 (Figure 13) displayed the best alpha glucosidase inhibition [47].

Figure 13.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Penicillium chrysogenum.

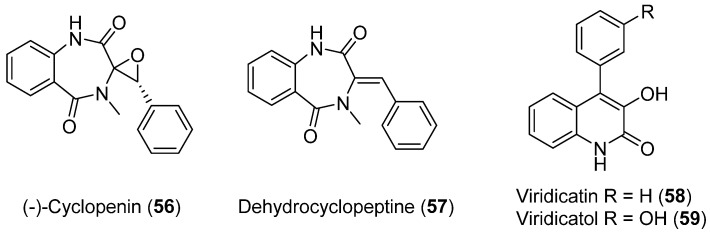

Penicillium echinulatum was isolated from the surface of the alga Adenocystis utricularis collected on a beach close to Comandante Ferraz Brazilian station on King George Island. In this study, photosafety was evaluated using photoreactivity (OECD TG 495) and phototoxicity assays performed by 3T3 neutral red uptake (3T3 NRU PT, OECD TG 432) and the RHS model. The purification of four alkaloids was achieved in a bio-guided process. Four known metabolites were identified: (−)-cyclopenin (56), dehydrocyclopeptine (57), viridicatin (58), and viridicatol (59) (Figure 14), and their photoprotective and antioxidant activities were shown [48].

Figure 14.

Alkaloids isolated from Penicillium echinulatum.

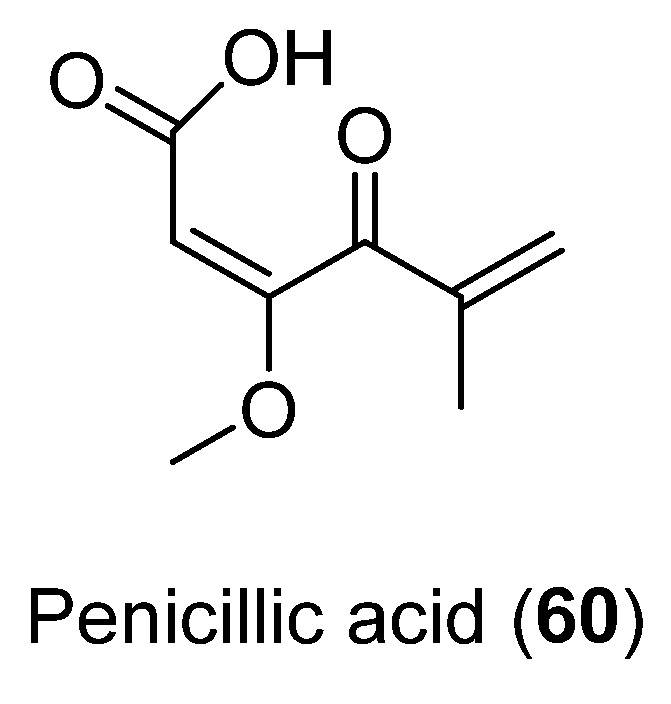

The antibacterial activity of Penicillic acid (60) (Figure 15), isolated from Penicillium sp. CRM-1540 found in Antarctic marine sediment at King George Island, was evaluated. This compound was obtained as the major bioactive fraction through a bioguided study. Results showed 90% bacterial inhibition in vitro at 25 µg mL−1 against Xanthomonas citri [49].

Figure 15.

Penicillic acid isolated from Penicillium sp. CRM-1540.

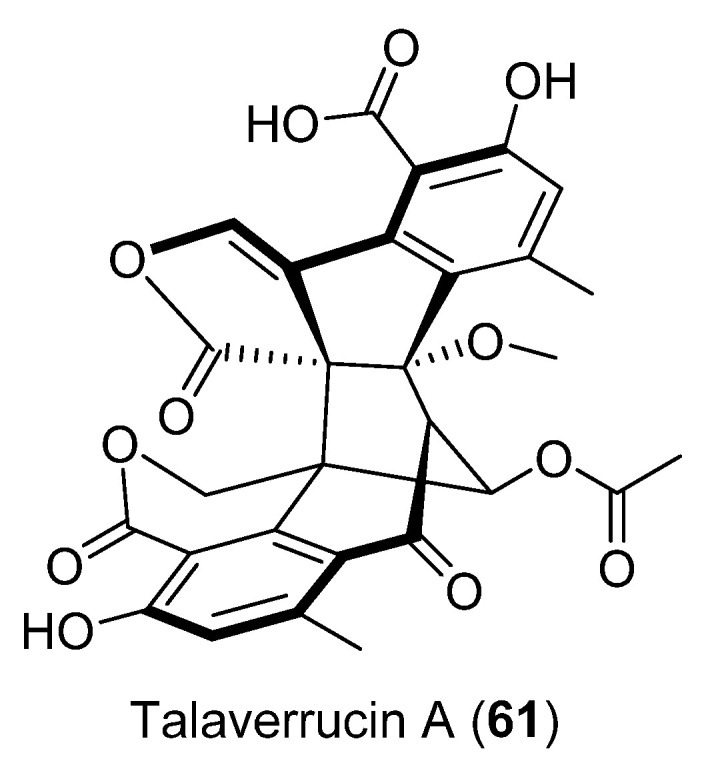

Talaverrucin A (61) (Figure 16), a heterodimeric oxaphenalenone with a rare fused ring system, was isolated from Talaromyces sp. HDN151403 (Prydz Bay, Antarctica). The oncogenic Wnt/β-catecin inhibitory effect was tested and showed inhibitory activity in zebrafish embryos in vivo and cultured mammalian cells in vitro [50].

Figure 16.

Talaverrucin A isolated from Penicillium sp. CRM-1540.

The cytotoxic activity of Citromycin (62) (Figure 17) was tested against ovarian cancer SKOV3 and A2780 cells. No cytotoxic activity was observed. The compound 62 was obtained from Sporothrix sp. and showed inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1/1 [51].

Figure 17.

Citromycin isolated from Sporothrix sp.

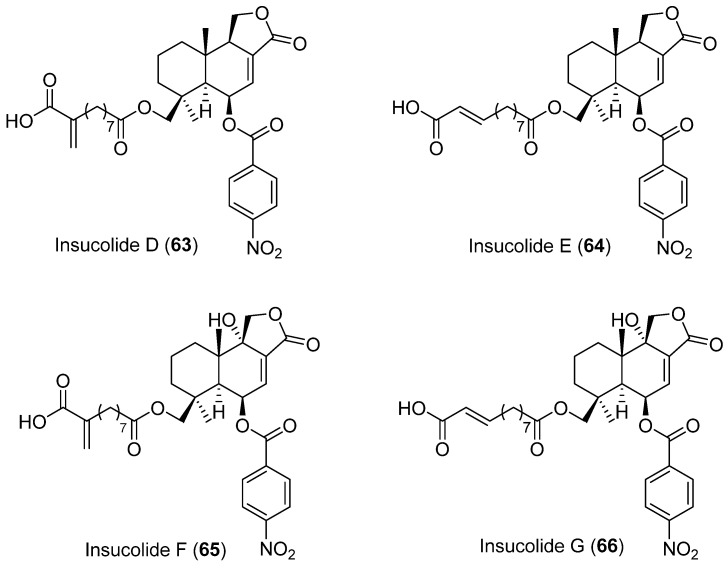

Four new cytotoxic nitrobenzoyl sesquiterpenoids, insulicolides D–G (63–66) (Figure 18), were isolated from Aspergillus insulicola HDN151418, which was obtained from an unidentified Antarctica sponge (Prydz Bay). Compounds 65 and 66 showed selective inhibition against human PDAC cell lines [52].

Figure 18.

Insucolides (D–G) isolated from Aspergillus insulicola HDN151418.

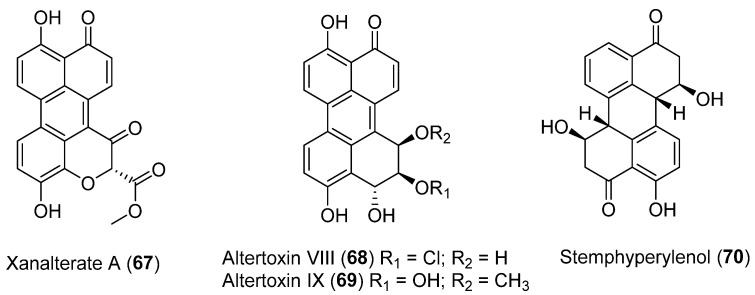

Three new perylenequinone derivatives (Xanalterate A, 67, Altertoxin VIII, 68 and IX, 69) together with a known natural product, Stemphyperylenol (70) (Figure 19), were isolated from Alternaria sp. HDN19-690 associated to an Antarctic sponge. Compound 67 exhibited promising antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant coagulase negative Staphylococcus (MRCNS), Bacillus subtilis, Proteus mirabilis, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, and Mycobacterium phlei with MIC values ranging from 3.13 to 12.5 µM [53].

Figure 19.

Perylenequinones isolated from Aspergillus insulicola HDN151418.

4. Materials and Methods

Scifinder database and the repositories of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and Universidad Técnica Federico Santa Maria were used to search for reports published from 1996 to date. The search criteria focused on marine fungi obtained from Chilean coasts, the South Shetland Islands, and Antarctic peninsula and reports of novel marine NPs that were spectroscopically characterized and presented biological or pharmaceutical properties. Descriptions involving vegetable extracts or primary metabolites were omitted.

5. Conclusions

Natural products from Chilean marine fungi represent a prolific and yet underexplored source of chemical structures with remarkable biomedical applications (Table 1). Alkaloids, polyketides, terpenoids, isoprenoids, non-isoprenoid compounds, and quinones display the most relevant biological activities. There are few studies on secondary metabolites isolated from marine fungi collected in Chile, highlighting the antimicrobial activity presented by some crude extracts and the antitumor activity of some of the isolated compounds. The dearth of studies may be attributed to the difficulties in cultivating microorganisms, some of which cannot survive under standard laboratory conditions and therefore cannot be cultured using traditional techniques. It is complicated to reproduce the conditions found inside the host marine organisms. The culture medium used is suitable for facultative fungi but probably inadequate for natural marine fungi. Recent advances in chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques now open a world of possibility for isolating secondary metabolites of these organisms that are abundant in Chilean marine ecosystems.

Table 1.

Secondary metabolites isolated from Chilean and Antarctic Fungi.

| Compounds | Fungi | Region | Bioactivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cladosporium cladosporioides | Chilean coasts | Not antimicrobial activity showed | [23] |

| 2 |

Inonotus obliquus Geotrichum sp. |

Cytotoxic activity, Lipid-peroxidation, Antioxidant activity | [22,23,26] | |

| 3 | Penicillium brevicompactum | Antibacterial activity | [24] | |

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | Geotrichum sp. | Not tested | [26] | |

| 8 |

Scleroderma polyrizum Geotrichum sp. Lampteromyces japonicus Fomes officinalis |

Not tested | [25,26] | |

| 9 | Geotrichum sp. | Not tested | [26] | |

| 10 | Geomyces sp. | Not tested | [27] | |

| 11 | Aspergillus sp. | Antibacterial activity | [28] | |

| 12 | Antitumor activity | |||

| 13 | Vasorelaxant activity | |||

| 14 | Aspergillus sp. | Not tested | [28] | |

| 15 | Geomyces sp. | Antarctic | Not antimicrobial, and antifungal activity showed |

[31,32,33,34] |

| 16 | Not antimicrobial, and antifungal activity showed |

|||

| 17 | Not antimicrobial, and antifungal activity showed |

|||

| 18 | Antifungal activity | |||

| 19 | Antibacterial activity | |||

| 20 | Tridocherma asperellum | Not tested | [35] | |

| 21 | Not tested | |||

| 22 | Not tested | |||

| 23 | Not tested | |||

| 24 | Not tested | |||

| 25 | Not tested | |||

| 26 | Penicillium crustosum | Not cytotoxic activity showed | [36,37] | |

| 27 | Inhibit nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) | |||

| 28 | Oidiodendron truncatum GW3-13 | Cytotoxic activity | [38] | |

| 29 | ||||

| 30 | ||||

| 31 | No significant cytotoxic activity showed | |||

| 32 | No significant cytotoxic activity showed | |||

| 33 | No significant cytotoxic activity showed | |||

| 34 | No significant cytotoxic activity showed | |||

| 35 | Pseudogymnoascus sp. | Not antimicrobial and antifungal activity showed | [40] | |

| 36 | Not antimicrobial and antifungal activity showed | |||

| 37 | Not antimicrobial and antifungal activity showed | |||

| 38 | Not antimicrobial and antifungal activity showed | |||

| 39 | Penicillium sp. | Antarctic | Antiproliferative effect | [42] |

| 40 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 41 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 42 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 43 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 44 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 45 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 46 | Not antiproliferative effect showed | |||

| 47 | Penicillium crestosum (PRB-2) | No cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | [44] | |

| 48 | Antibacterial activity | |||

| 49 | Antibacterial activity | |||

| 50 | No cytotoxic, and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 51 | Penicillium chrysogenum | Moderate alpha glucosidase inhibition, no cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | [47] | |

| 51a | Moderate alpha glucosidase inhibition, no cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 51b | Moderate alpha glucosidase inhibition, no cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 52a | Moderate alpha glucosidase inhibition, no cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 52b | Moderate alpha glucosidase inhibition, no cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 53 | Antibacterial activity | |||

| 54 | Cytotoxic activity | |||

| 55 | Alpha glucosidase inhibition | |||

| 56 | Penicillium echinulatum | Photoprotective and antioxidant activity | [48] | |

| 57 | No cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 58 | Cytotoxic activity | |||

| 59 | Cytotoxic activity | |||

| 60 | Penicillium sp. CRM-1540 | Antibacterial activity | [49] | |

| 61 | Talaromyces sp. HDN151403 | Cytotoxic activity | [50] | |

| 62 | Sporothrix sp. | Cytotoxic activity | [51] | |

| 63 | Aspergillus insulicola HDN151418 | No cytotoxic activity showed | [52] | |

| 64 | No cytotoxic activity showed | |||

| 65 | Cytotoxic activity | |||

| 66 | Cytotoxic activity | |||

| 67 | Alternaria sp. HDN19-690 | Antibacterial activity, no cytotoxic activity showed | [53] | |

| 68 | No cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 69 | No cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed | |||

| 70 | No cytotoxic and antibacterial activity showed |

Acknowledgments

J.R.C.-P thanks Instituto Antártico Chileno (INACH), for grant RT_16-21, D.A express thanks to the Dirección de Postgrado y Programas (DPP), Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María. The authors thank Ellen Leffler for critical reading and suggestions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A. and J.R.C.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.; resources, D.A.; H.C., A.S.-M. and J.R.C.-P.; writing—review and editing, L.T., H.C., J.R.C.-P. and A.S.-M. All authors participated in similar measure in the preparation of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicting interest in the publication.

Funding Statement

Instituto Antártico Chileno (INACH) RT_16-21.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Tong Y., Deng Z. An Aurora of Natural Products-Based Drug Discovery Is Coming. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2020;5:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:629–661. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:770–803. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clardy J., Walsh C. Lessons from Natural Molecules. Nature. 2004;432:829–837. doi: 10.1038/nature03194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J., Kim S.-H. A Genome Tree of Life for the Fungi Kingdom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:9391–9396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711939114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo A.M., Wilson R.A., Bok J.W., Keller N.P. Relationship between Secondary Metabolism and Fungal Development. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:447–459. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.447-459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen J.C., Grijseels S., Prigent S., Ji B., Dainat J., Nielsen K.F., Frisvad J.C., Workman M., Nielsen J. Global Analysis of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters Reveals Vast Potential of Secondary Metabolite Production in Penicillium Species. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:17044. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schueffler A., Anke T. Fungal Natural Products in Research and Development. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31:1425–1448. doi: 10.1039/C4NP00060A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll A.R., Copp B.R., Davis R.A., Keyzers R.A., Prinsep M.R. Marine Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021;38:362–413. doi: 10.1039/D0NP00089B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll A.R., Copp B.R., Davis R.A., Keyzers R.A., Prinsep M.R. Marine Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022;39:1122–1171. doi: 10.1039/D1NP00076D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montuori E., De Pascalle D., Lauritano C. Recent Discoveries on Marine Organism Immunomodulatory Activities. Mar. Drugs. 2022;20:422. doi: 10.3390/md20070422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durães F., Szemerédi N., Kumla D., Pinto M., Kijjoa A., Spengler G., Sousa E. Metabolites from Marine-Derived Fungi as Potential Antimicrobial Adjuvants. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:475. doi: 10.3390/md19090475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De la Calle F. Fármacos de Origen Marino. Treballs de la SCB. 2007;58:141–155. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.02.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rateb M.E., Ebel R. Secondary Metabolites of Fungi from Marine Habitats. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:290. doi: 10.1039/c0np00061b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hafez Ghoran S., Kijjoa A. Marine-Derived Compounds with Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Activities. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:410. doi: 10.3390/md19080410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang M., Wu Z., Guo H., Liu L., Chen S. A Review of Terpenes from Marine-Derived Fungi: 2015–2019. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:321. doi: 10.3390/md18060321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Demerdash A., Kumla D., Kijjoa A. Chemical Diversity and Biological Activities of Meroterpenoids from Marine Derived-Fungi: A Comprehensive Update. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:317. doi: 10.3390/md18060317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuestro País. [(accessed on 24 October 2022)]. Available online: https://www.gob.cl/nuestro-pais/

- 19.Masas de Agua En El Mar Chileno. [(accessed on 24 October 2022)]. Available online: http://www7.uc.cl/sw_educ/geo_mar/html/h43.html.

- 20.Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional | SIIT | Chile Nuestro País. [(accessed on 24 October 2022)]. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/siit/nuestropais/index_html.

- 21.Núñez-Pons L., Shilling A., Verde C., Baker B.J., Giordano D. Marine Terpenoids from Polar Latitudes and Their Potential Applications in Biotechnology. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:401. doi: 10.3390/md18080401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasukawa K., Akihisa T., Kanno H., Kaminaga T., Izumida M., Sakoh T., Tamura T., Takido M. Inhibitory Effects of Sterols Isolated from Chlorella Vulgaris on 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-Acetate-Induced Inflammation and Tumor Promotion in Mouse Skin. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1996;19:573–576. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.San Martin A., Painemal K., Diaz Y., Martinez C., Rovirosa J. Metabolites from the marine fungus Cladosporium cladosporioides. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2005;93:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rovirosa J., Diaz-Marrero A., Darias J., Painemal K., San Martin A. Secondary metabolites from the marine Penicillium brevicompactum. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2006;51:775–778. doi: 10.4067/S0717-97072006000100004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciminiello P., Fattorusso E., Magno S., Mangoni A., Pansini M. A Novel Conjugated Ketosteroid from the Marine Sponge Dictyonella Incisa. J. Nat. Prod. 1989;52:1331–1333. doi: 10.1021/np50066a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.San-Martín A., Orejarena S., Gallardo C., Silva M., Becerra J., Reinoso R., Chamy M.C., Vergara K., Rovirosa J. Steroids from the marine fungus Geotrichum sp. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2008;53:1377–1378. doi: 10.4067/S0717-97072008000100011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manríquez V., Galdámez A., Veliz B., Rovirosa J., Díaz-Marrero A.R., Cueto M., Darias J., Martínez C., San-Martín A. N-methyl-1H-indole-2-carboxamide from the marine fungus Cladosporium cladosporioides. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2009;54:314–316. doi: 10.4067/S0717-97072009000300023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.San-Martín A., Rovirosa J., Vaca I., Vergara K., Acevedo L., Viña D., Orallo F., Chamy M.C. New butyrolactone from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2011;56:625–627. doi: 10.4067/S0717-97072011000100023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson Z.E., Brimble M.A. Molecules Derived from the Extremes of Life. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:44–71. doi: 10.1039/B800164M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusman Y., Held B.W., Blanchette R.A., He Y., Salomon C.E. Cadopherone and Colomitide Polyketides from Cadophora Wood-Rot Fungi Associated with Historic Expedition Huts in Antarctica. Phytochemistry. 2018;148:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian Y., Li Y.-L., Zhao F.-C. Secondary Metabolites from Polar Organisms. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15:28. doi: 10.3390/md15030028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosa L.H., editor. Fungi of Antarctica: Diversity, Ecology and Biotechnological Applications. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cong M., Pang X., Zhao K., Song Y., Liu Y., Wang J. Deep-Sea Natural Products from Extreme Environments: Cold Seeps and Hydrothermal Vents. Mar. Drugs. 2022;20:404. doi: 10.3390/md20060404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., Sun B., Liu S., Jiang L., Liu X., Zhang H., Che Y. Bioactive Asterric Acid Derivatives from the Antarctic Ascomycete Fungus Geomyces Sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1643–1646. doi: 10.1021/np8003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren J., Xue C., Tian L., Xu M., Chen J., Deng Z., Proksch P., Lin W. Asperelines A−F, Peptaibols from the Marine-Derived Fungus Trichoderma Asperellum. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:1036–1044. doi: 10.1021/np900190w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu G., Ma H., Zhu T., Li J., Gu Q., Li D. Penilactones A and B, Two Novel Polyketides from Antarctic Deep-Sea Derived Fungus Penicillium Crustosum PRB-2. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:9745–9749. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2012.09.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spence J.T.J., George J.H. Biomimetic Total Synthesis of ent-Penilactone A and Penilactone B. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3891–3893. doi: 10.1021/ol4017832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L., Li D., Luan Y., Gu Q., Zhu T. Cytotoxic Metabolites from the Antarctic Psychrophilic Fungus Oidiodendron Truncatum. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:920–927. doi: 10.1021/np3000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henríquez M., Vergara K., Norambuena J., Beiza A., Maza F., Ubilla P., Araya I., Chávez R., San-Martín A., Darias J., et al. Diversity of Cultivable Fungi Associated with Antarctic Marine Sponges and Screening for Their Antimicrobial, Antitumoral and Antioxidant Potential. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;30:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Figueroa L., Jiménez C., Rodríguez J., Areche C., Chávez R., Henríquez M., de la Cruz M., Díaz C., Segade Y., Vaca I. 3-Nitroasterric Acid Derivatives from an Antarctic Sponge-Derived Pseudogymnoascus Sp. Fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:919–923. doi: 10.1021/np500906k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonçalves V.N., Carvalho C.R., Johann S., Mendes G., Alves T.M.A., Zani C.L., Junior P.A.S., Murta S.M.F., Romanha A.J., Cantrell C.L., et al. Antibacterial, Antifungal and Antiprotozoal Activities of Fungal Communities Present in Different Substrates from Antarctica. Polar Biol. 2015;38:1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1672-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Y., Li Y.-H., Yu H.-B., Liu X.-Y., Lu X.-L., Jiao B.-H. Furanone Derivative and Sesquiterpene from Antarctic Marine-Derived Fungus Penicillium Sp. S-1-18. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;20:1108–1115. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2017.1385604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wentzel L.C.P., Inforsato F.J., Montoya Q.V., Rossin B.G., Nascimento N.R., Rodrigues A., Sette L.D. Fungi from Admiralty Bay (King George Island, Antarctica) Soils and Marine Sediments. Microb. Ecol. 2019;77:12–24. doi: 10.1007/s00248-018-1217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu G., Sun Z., Peng J., Zhu M., Che Q., Zhang G., Zhu T., Gu Q., Li D. Secondary Metabolites Produced by Combined Culture of Penicillium crustosum and a Xylaria Sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2019;82:2013–2017. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tripathi V.C., Satish S., Horam S., Raj S., lal A., Arockiaraj J., Pasupuleti M., Dikshit D.K. Natural Products from Polar Organisms: Structural Diversity, Bioactivities and Potential Pharmaceutical Applications. Polar Sci. 2018;18:147–166. doi: 10.1016/j.polar.2018.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teixeira T.R., Santos G.S.d., Armstrong L., Colepicolo P., Debonsi H.M. Antitumor Potential of Seaweed Derived-Endophytic Fungi. Antibiotics. 2019;8:205. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8040205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khan I., Zhang H., Liu W., Zhang L., Peng F., Chen Y., Zhang Q., Zhang G., Zhang W., Zhang C. Identification and Bioactivity Evaluation of Secondary Metabolites from Antarctic-Derived Penicillium chrysogenum CCTCC M 2020019. RSC Adv. 2020;10:20738–20744. doi: 10.1039/D0RA03529G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teixeira T.R., Rangel K.C., Tavares R.S.N., Kawakami C.M., dos Santos G.S., Maria-Engler S.S., Colepicolo P., Gaspar L.R., Debonsi H.M. In Vitro Evaluation of the Photoprotective Potential of Quinolinic Alkaloids Isolated from the Antarctic Marine Fungus Penicillium echinulatum for Topical Use. Mar. Biotechnol. 2021;23:357–372. doi: 10.1007/s10126-021-10030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vieira G., Khalil Z.G., Capon R.J., Sette L.D., Ferreira H., Sass D.C. Isolation and Agricultural Potential of Penicillic Acid against Citrus Canker. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022;132:3081–3088. doi: 10.1111/jam.15413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun C., Liu Q., Shah M., Che Q., Zhang G., Zhu T., Zhou J., Rong X., Li D. Talaverrucin A, Heterodimeric Oxaphenalenone from Antarctica Sponge-Derived Fungus Talaromyces Sp. HDN151403, Inhibits Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Org. Lett. 2022;24:3993–3997. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi H.Y., Ahn J.-H., Kwon H., Yim J.H., Lee D., Choi J.-H. Citromycin Isolated from the Antarctic Marine-Derived Fungi, Sporothrix Sp., Inhibits Ovarian Cancer Cell Invasion via Suppression of ERK Signaling. Mar. Drugs. 2022;20:275. doi: 10.3390/md20050275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun C., Liu X., Sun N., Zhang X., Shah M., Zhang G., Che Q., Zhu T., Li J., Li D. Cytotoxic Nitrobenzoyl Sesquiterpenoids from an Antarctica Sponge-Derived Aspergillus Insulicola. J. Nat. Prod. 2022;85:987–996. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hou Z., Sun C., Chen X., Zhang G., Che Q., Li D., Zhu T. Xanalterate A, Altertoxin VIII and IX, Perylenequinone Derivatives from Antarctica-Sponge-Derived Fungus Alternaria Sp. HDN19-690. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022;96:153778. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.153778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]