Abstract

The region upstream of the Escherichia coli bgl operon is an insertion hot spot for several transposons. Elements as distantly related as Tn1, Tn5, and phage Mu home in on this location. To see what characteristics result in a high-affinity site for transposition, we compared in vivo and in vitro Mu transposition patterns near the bgl promoter. In vivo, Mu insertions were focused in two narrow zones of DNA near bgl, and both zones exhibited a striking orientation bias. Five hot spots upstream of the bgl cyclic AMP binding protein (CAP) binding site had Mu insertions exclusively with the phage oriented left to right relative to the direction of bgl transcription. One hot spot within the CAP binding domain had the opposite (right-to-left) orientation of phage insertion. The DNA segment lying between these two Mu hot-spot clusters is extremely A/T rich (80%) and is an efficient target for insertion sequences during stationary phase. IS1 insertions that activate the bgl operon resulted in a decrease in Mu insertions near the CAP binding site. Mu transposition in vitro differed significantly from the in vivo transposition pattern, having a new hot-spot cluster at the border of the A/T-rich segment. Transposon hot-spot behavior and orientation bias may relate to an asymmetry of transposon DNA-protein complexes and to interactions with proteins that produce transcriptionally silenced chromatin.

Transposable elements are intimately involved in the evolution of prokaryotic and eukaryotic chromosomes (5). In bacteria, transposons cause chromosomal rearrangements that include inversions, deletions, and translocations; in addition, they are a major pathway for interspecies transfer, resulting in dissemination of drug resistance genes and genes that facilitate the spread of bacterial diseases in plants and animals (25). Understanding how transposons contribute to bacterial evolution requires (i) knowledge of the regulation of the proteins that stimulate transposition and (ii) deciphering of the mechanisms by which transposons select chromosomal sites for insertion.

A few sites in Escherichia coli have been noted to be hot spots for various transposons. One phage Mu hot spot is in the E. coli lamB gene of the maltose operon (10). At this site, more than 25% of all Mu insertions in the maltose operon occur in a region that represents only 3% of the maltose DNA. Another example is the bgl operon, which encodes proteins for transport and utilization of aromatic β-glucosides such as arbutin and salicin (19). Normally, the bgl operon is transcribed at low levels in wild-type (WT) cells, but high-level expression can be induced by mutation. Activation can be caused by point mutations in gyrA or gyrB (9), hns (12), bglJ (11), or the cyclic AMP binding protein (CAP) binding site of the bgl promoter (17, 24). Surprisingly, the most frequent mechanism for activation involves insertion sequence (IS) elements (22–24, 27). IS element insertion in a 50-bp target upstream of the CAP binding site results in fiftyfold activation of the bgl operon. Such activating insertions occur more frequently when cells are grown on poor carbon sources than when cells are grown in rich medium, and in certain strains the frequency of activation approaches 10−4 (22). Once activated, the bgl operon is regulated by β-glucosides through antitermination of transcription (2, 13, 19, 26).

“Muprinting” is a PCR-based technique that allows reproducible determination of transposition target selection in vivo (30). This method utilizes primers that match sites in the bacterial chromosome and primers that match sites at the left and right ends of Mu to detect transposition target site selection and determine its efficiency. Using the Muprint method, we have previously demonstrated changes in chromosome structure at the lac operator when cells are induced by addition of either lactose or isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (30). Muprinting also allows a quantitative assessment of transposition in specified fields; we have demonstrated that transposition immunity, which is the negative influence exerted by a Mu transposase binding site in a bacterial chromosome on Mu transposition into neighboring sequences, is diminished to 50% at a distance of 20 kb (20).

The bgl operon is an excellent model for studying gene silencing in E. coli (6, 28). We have previously shown that bgl is a hot spot for Mu transposition (30). In the present study, we expanded our analysis of the bgl region and cloned individual Muprint bands to reveal Mu target selection in vivo at base-pair-level resolution. At the bgl locus, Mu transposition occurs near the borders of the A/T-rich patch that contains the sites for activating IS1 insertions. In addition to strong site specificity, there is a striking orientation bias: all Mu inserts upstream of the binding site have a left-to-right (L-R) orientation, and a single Mu hot spot downstream of the CAP binding site is uniquely oriented right to left (R-L). PCR analysis also showed a strong orientation bias in the appearance of stationary-phase IS1 insertions near the bgl operon. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo Mu transposition patterns indicated that orientation bias is intrinsic to Mu transposition proteins. Deletion of the A/T-rich tract eliminated all Mu hot spots; therefore, the in vivo chromosome structure of the A/T tract creates high-affinity target sites for Mu transposition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and phages.

Bacteria used in this work were derivatives of E. coli K-12 strain MC4100, and the genetic makeup of each strain is given in Table 1. The phage used in Muprinting experiments was Mucts62pAp1 (16). Bacteria were grown in Luria broth (LB) or minimal media supplemented with Casamino Acids or salicin as indicated. Solid media were made by adding 15 g of Bacto Agar per liter of liquid medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Straina | Genotypeb | Source |

|---|---|---|

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR | Lab stock |

| NH1126 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 | This work |

| NH3285 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 bgl-678::IS1 | This work |

| NH3286 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 bgl-679::IS1 | This work |

| NH3287 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 bgl-680::IS1 | This work |

| NH3288 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 bgl-681::IS1 | This work |

| NH3386 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 hns651 trpB83::Tn10 | This work |

| NH3387 | MC4100 bgl-682 (ΔAT) | This work |

| NH3388 | MC4100 Mucts62pAp1 bgl-682 (ΔAT) | This work |

All strains are derivatives of E. coli K-12.

The chromosomal location of the Mucts62pAp1 insertion is not known.

Strains were converted to Mu lysogens by infecting exponentially growing cells with Mucts62pAp1 at a multiplicity of 0.1 and plating aliquots at 30°C on LB-agar plates containing ampicillin (25 μg/ml). Putative lysogens were purified on LB containing ampicillin and tested for Mu phage production after thermoinduction of liquid cultures. About 1% of the infected cells were converted to Mu lysogens under these conditions.

Deletion of the A/T-rich region upstream of the bgl promoter.

The A/T-rich patch (base pair [bp] −131 to bp −76 in Fig. 2) was precisely deleted from the bacterial chromosome by using the lambda Red recombination method as described by Yu et al. (31). A single-stranded oligomer 80 nucleotides long with the sequence AGATAGCGACAAATAATTCACCAGACAAATCCCAATAACTAATAACTGCGAGCATGGTCATATTTTTATCAATAGCGCAT was synthesized. In this molecule, 40 bases match the region upstream and 40 bases match the region downstream of the A/T-rich tract near bglC. Recombinants that had undergone the 56-bp deletion were identified by their ability to grow on salicin as the sole carbon source. The limits of the deletion were confirmed by PCR product analysis using the bgl-specific primers BglC1 and PhoUI. Mucts62pAp1 lysogens of the deletion mutant were subsequently isolated by infecting the strain with a phage and selecting for resistance to ampicillin.

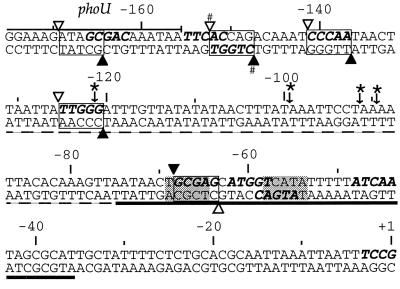

FIG. 2.

Sequenced Mu and IS1 insertions in the bgl control region. The sequence of 175 bp of DNA preceding the bglC transcriptional start site is shown. A thin overline marks the 5′ end of the phoU gene. The A/T-rich IS1 target zone is indicated by a dashed underline; this sequence was deleted for the experiment shown in Fig. 7. A thick line under the sequence shows the CAP binding site, and shaded boxes indicate the CAP binding consensus sequence. The bglC transcription start site is indicated as +1. Mu insertion hot spots are indicated by open (Mu left end) and closed (Mu right end) triangles. Positions having the symmetric 5-bp Mu consensus cleavage sequence favored by the Mu A protein (5′-N-Y-G/C-R-N-3′) are shown as bold italic letters on the top strands, and positions at which two consensus sites overlap are indicated the same way on the bottom strands. IS1 insertions that cause activation of bgl transcription are indicated by arrows below asterisks. Boxed sequences represent 5-bp duplications generated by Mu insertion. #, primary hot spot.

Chromosomal DNA for Muprint reactions.

Bacterial chromosomal DNA was prepared from 10-ml portions of broth cell cultures. Cells were grown in LB at 30°C with shaking and then shifted to a 42°C water bath, where growth was continued for another 30 min. Cultures were chilled to 4°C, and cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1-ml volumes of EDTA solution (EDTA, 150 mM; NaCl, 150 mM; Sigma lysozyme, 4 mg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Cells were lysed by the addition of 1.5 ml of lysis solution (Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M; NaCl, 0.1 M; sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1%). Proteinase K was added (100 μl of a 10-mg/ml solution), and incubation was carried out at 37°C for 1 h. After being sheared by passage through a 22-gauge needle five times, DNA was extracted twice with an equal volume of a 1:1 mixture of Tris-saturated phenol and chloroform. To the extracted solution was added 1/10 volume of sodium acetate (3 M, pH 7.0), and DNA was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol. The DNA pellet was washed in 70% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in TE buffer (Tris-Cl [pH 7.0], 10 mM; EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mM).

DNA primers for PCR.

Chromosomal DNA primers used were BglC1 (GGTGATTTGCATGTTCATAGC; positions +147 to +126), PhoUI (CGGATGGACATTGACGAAG; −441 to −422), and PhoUII (GGTATTGTTCGTCAACTGATGACC; −375 to −351). The bases are numbered relative to the transcription start site of bglC. Mu primers used were MuL (TTTTTCGTACTTCAAGTGAATC; the reverse complement of bp 7 to 28) and MuR (CCGAATTCGCATTTATCGTGAAACGCTTTC; bp 36671 to 36696). Italicized bases are nontemplate bases, and the sequence numbering is relative to the full Mu sequence (GenBank accession no. AF083977.) The IS1-specific primer ISrev matches the reverse complement of bp 65 to 86 (AGCTGATAGAAACAGAAGCCAC; accession no. for IS1 sequence is AF205566).

Muprinting PCRs.

Each Muprint PCR mixture contained a radiolabeled chromosomal primer, nonradioactive (“cold”) MuL or MuR primer, and bacterial genomic DNA. Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were radiolabeled by using phage T4 polynucleotide kinase (BRL). Labeling reaction mixtures (10-μl volumes) contained 2 μl of oligonucleotide (10 μM solution), 1 μl of kinase buffer (Tris-Cl [pH 7.8], 600 mM; MgCl2, 100 mM; KCl, 1 M), 1 μl of dithiothreitol (150 mM solution), 0.5 μl of T4 polynucleotide kinase (1-U/μl solution), and 5 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (NEN; 3,000 Ci/mmol). Labeling was done at 37°C for 30 min followed by 90°C for 5 min. The quantity of radiolabeled primer from each reaction was sufficient for four Muprint PCRs.

Muprint PCR mixtures contained 2.5 μl of radiolabeled oligonucleotide (described above), 2.5 μl of MuL or MuR primer (10 μM solution), 5 μl of 10× Taq PCR buffer (Tris-Cl [pH 8.3], 100 mM; KCl, 500 mM), 6 μl of MgCl2 solution (25 mM), 1 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (2.5 U), and 2 μl of bacterial genomic DNA (1-mg/ml solution), with water added so that the final volume was 50 μl. Thermocycling was done in three steps of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C for 30 cycles. PCR products were ethanol precipitated, air dried, and resuspended in 10 μl of sequencing stop solution (deionized formamide, 95%; EDTA [pH 8.0], 10 mM; bromophenol blue, 0.1% [wt/vol]; xylene cyanol, 0.1% [wt/vol]). Two microliters of this preparation was loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide denaturing sequencing gel, and electrophoresis was carried out at a constant 1,600 V. After electrophoresis, gels were dried and autoradiographed.

In vitro Mu transposition.

Assembly of in vitro Mu transposition reaction mixtures was done as described by Millner and Chaconas (21). Briefly, standard type 1 in vitro transposition reaction mixtures were assembled with mini-Mu plasmid, MuA protein, HU protein, integration host factor (IHF), 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and 140 mM NaCl. Supercoiled target plasmid pAW6, which has a 1-kb insert containing the bglR region cloned between the BamHI and HindIII sites of pBR322 (24), was incubated with 0.5 mM ATP and Mu B protein and mixed with type 1 transpososomes at 30°C for 10 min. Reactions were stopped by addition of EDTA, and products were subsequently deproteinized with proteinase K.

RESULTS

Mu orientation is biased near bgl.

The normally poorly expressed bgl operon can be activated by IS1 or IS5 insertions to yield high-level expression. Previously, we showed that the bgl region was a hot spot for Mu transposition (30). To compare the transposition patterns of Mu and IS1 in the segment of DNA that regulates bgl expression, Muprints were generated using primers matching either the Mu right end (MuR) or Mu left end (MuL) in combination with a radiolabeled primer matching sequences in the bglC or phoU gene. The organization of genes and cis elements at the bgl promoter is shown at the top of Fig. 1. A CAP binding site spans positions −35 to −75, and an A/T-rich patch in positions −76 to −125 is the target region for the most common type of bgl-activating IS1 insertions.

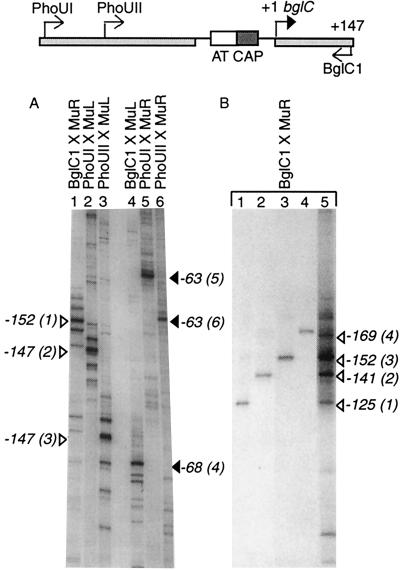

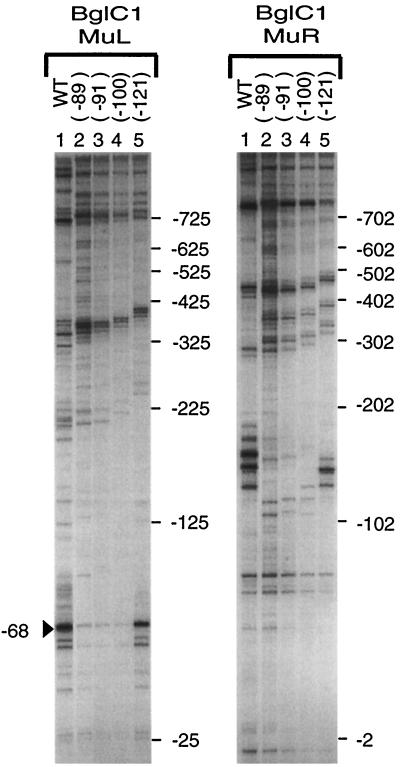

FIG. 1.

Mu transposition hot spots in the transcriptional control region of the bglC gene. At the top is the structure of the bglC control region and the positions of DNA primers used for Muprint PCRs. The A/T-rich IS target (AT), the CAP binding site (CAP), and the bglC transcription start site (+1) are indicated. (A) Muprints were developed using the following primer combinations: BglC1 and MuR (lane 1), PhoUI and MuL (lane 2), PhoUII and MuL (lane 3), BglC1 and MuL (lane 4), PhoUI and MuR (lane 5), and PhoUII and MuR (lane 6). Insertion sites of the strongest hot spot in each lane are indicated to the left and right of the autoradiographic image. (B) Examples of cloned Muprint bands were run alongside a Muprint PCR. Lanes 1 through 4 include products of PCRs (using primers BglC1 and MuR) of four cloned Muprint band, and their insertion sites, determined from sequencing, are indicated on the right. Lane 5 shows the Muprint reaction done with the BglC1-MuR primer combination.

In the first experiment, E. coli NH1126 was induced for Mu transposition, chromosomal DNA was isolated, and Muprints were made with the BglC1 primer, which matches positions +147 to +126 of the bglC template strand, and the MuR primer (Fig. 1A, lane 1). Each Muprint is the sum of the BglC1 primer (21 bp), the intervening sequence, and MuR end sequences (51 bp). Muprints of between 100 and 500 bp can be resolved on DNA sequencing gels with base-pair-level resolution. The striking result with the MuR-BglC1 primer combination was a five-band cluster with the most intense band positioned at the center. The size of each band was measured relative to internal size markers; the most prominent hot spot for Mu right-end integration was near position −150 on the bglC nontemplate strand, and the second-most-intense band was 11 bp nearer the primer. A distance ranging from 11 to 17 bp separated each band in this cluster from the next band. This result demonstrated a five-hot-spot cluster in which Mu was inserted with the left end upstream and the right end downstream, which we refer to as the L-R orientation. When the same template DNA preparation was examined with the MuL-BglC1 primer combination, a different pattern emerged. In this case, just a single hot spot appeared, positioned near −68 (Fig. 1, lane 4). This was the only prominent bgl region hot spot for Mu in which its right end was upstream and its left end was downstream (R-L orientation), and it was well separated from the L-R cluster by the A/T-rich region. These results demonstrate both site and orientation specificity for Mu transposition near bgl.

Whereas Muprinting has great precision, all PCR-based techniques include the possibility of artifacts. The most common artifact in Muprinting is “ghost” bands that come from adventitious matching of one primer to unknown sequences in the genome (see reference 20 for a discussion of these artifacts). To confirm the orientation selectivity of Mu transposition at bgl, primers that match sequences in the phoU gene were used. Relative to the start site of bglC transcription (+1), PhoUI and PhoUII match nucleotides at positions −441 to −422 and positions −375 to −351, respectively. Any transposition events detected by the MuR-BglC1 primer combination should produce bands complementary to those obtained with the MuL-PhoUI and MuL-PhoUII combinations. PCRs carried out with PhoUI and MuL generated five hot spots, each band being separated from its nearest neighbor by 11 to 17 bp (Fig. 1A, lane 2). Again, the central band was most dramatic, but the second-most-intense band was 11 bp above this band, rather than below it as in the reciprocal experiment. With the PhoUII-MuL primer combination, five hot spots were again obtained; this time, each band was shorter by 66 bp because of the proximity of primer PhoUII to the hot spot. These results confirmed the cluster of five hot spots for the L-R Mu orientation upstream of the A/T-rich region of the bgl operon. Complementary experiments with the PhoUI-MuR and PhoUII-MuR primer combinations also confirmed the absence of R-L insertions near position −150 and the existence of a single hot spot near position −68 (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6). We also checked to see whether the orientation of the original Mu lysogen was responsible for the striking pattern near bgl. Muprints made using independent lysogens and by phage infection all had identical patterns. Thus, the orientation bias of Mu transposition at bgl is an intrinsic property of the locus.

Precise Muprint map by cloning.

Mu transposition should generate a 5-bp duplication of DNA at each insertion point. To confirm this duplication pattern in Muprints at bgl, precise mapping information was needed. PCR products are difficult to analyze at base-pair-level resolution for two reasons. First, Taq polymerase adds a non-template-encoded nucleotide (usually dAMP) at the 3′ end of the synthetic product (8, 18). This nontemplate addition can differ depending on the sequence and conditions. Second, size markers derived from DNA with a sequence different from that of bgl may not match bgl-derived bands because of sequence-dependent variations in electrophoretic mobility. To obviate such problems, individual Muprint bands were cloned and sequenced. Individual bands could then be included in sequencing gels to map insertion points precisely (Fig. 1B). Using this method, the predicted 5-bp duplications were detected, and most of the hot spots were found to occur at Mu transposition consensus duplication sites of 5′-N-Y-G/C-R-N, where N is any nucleotide, Y is a pyrimidine, and R is a purine. Four of five L-R hot spots and the single R-L hot spot are depicted in Fig. 2; most insertions occur at a consensus site, but six consensus sites in the region are not used.

Orientation bias in IS1 transposition.

Insertion of IS1 elements upstream of the bgl promoter activates bgl operon expression, probably by destabilizing “silenced” chromatin (6, 28). Activation by IS insertions in the A/T-rich segment could indicate that the bgl promoter is a novel hot spot for IS insertions. To address this question, IS insertion sites in cells of a 1-day stationary-phase culture grown in LB (without salicin) and in cells grown for 7 days on salicin selection plates, in which colony growth is stimulated by bgl operon activation, were mapped by PCR.

In stationary-phase cultures, the ISrev primer, located at position +86 from the left end of IS1, and the BglC1 primer yielded seven bands, spaced at roughly 100-bp intervals (Fig. 3A, lane 1). In contrast, these bands were much weaker in log-phase cells and were at least fivefold stronger in a 7-day culture (data not shown). Thus, IS1 transposition occurs throughout the bgl region after starvation, but there seem to be only a few specific insertion targets. With the primer combination ISrev-PhoUI (Fig. 3A, lane 3), which scans for IS1 inserts in the opposite orientation, 10 bands were detected, and again these target sites were broadly scattered throughout the region. At each position, IS1 transposition was orientation specific since no single site became occupied by IS1 elements in both orientations.

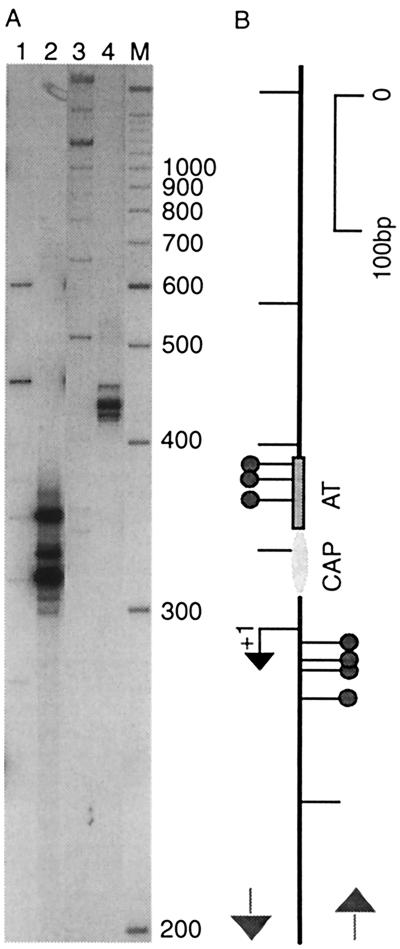

FIG. 3.

Selected versus unselected IS insertions in the bgl control region. (A) IS insertions from a population of WT cells (lanes 1 and 3) and a population of cells selected for Bgl+ (lanes 2 and 4) were detected using radiolabeled BglC1 and cold ISrev (lanes 1 and 2) or radiolabeled PhoU1 and unlabeled ISrev (lanes 3 and 4) primer pairs. Positions of molecular size markers (in bases) are indicated on the right. (B) Positions and orientations of IS insertions on the DNA segment, as deduced from PCR band sizes, are shown relative to the bgl transcriptional start site (+1). Insertions that resulted in the Bgl+ phenotype are marked with circles. On the left are insertions mapped with the BglC1-ISrev primer pair, and on the right are insertions mapped with the PhoUI-ISrev primer pair. Also shown are the CAP binding site (CAP) and the A/T-rich segment (AT) immediately upstream of the bgl promoter.

To analyze the class of insertions that activate bgl gene expression, spontaneous Bgl+ colonies were pooled (about 10,000) from minimal plates on which cells had been incubated 7 days with supplemental salicin. DNA was extracted, and PCR was performed with the BglC1-ISrev primer combination. Although bgl activation can occur because of point mutations in a number of different genes, it is clear from the PCR profile that IS1 transposition is a very frequent activating mechanism when cells are starved and under selection for growth on salicin (Fig. 3). Three strong IS1 bands resulted from R-L-oriented insertions into the A/T-rich zone. The strongest band proved to be a doublet (Fig. 3, lane 2; see also below). Two of the bands in the Sal+ population were much weaker bands in the nonselected population of stationary-phase cells grown in LB without supplemental salicin (Fig. 3A, lane 1). To identify precisely where IS1 insertions occurred, individual Bgl+ strains were purified and PCR analysis was carried out to identify the transposition target. Four activating insertions were sequenced, and their positions are indicated in Fig. 2 and 4B.

FIG. 4.

Targets for activating IS insertions at the bgl control region. Most of the activating IS insertions occurred at one of four sites in the A/T-rich segment upstream of the bgl promoter. (A) PCR with ISrev and BglC1 primers on DNA from Sal+ strains NH3285 (lane 1), NH3286 (lane 2), NH3287 (lane 3), and NH3288 (lane 4). These positions are also indicated by asterisks in Fig. 2. Positions of molecular size markers (M; in bases) are indicated on the right. (B) Map of the IS insertion sites as determined by PCR product analysis. Also shown are the A/T-rich region (AT) and the CAP binding site (CAP).

IS1 insertions with the opposite orientation (L-R) were identified by PCR using the PhoUI-ISrev primer combination. From the same population that revealed abundant IS1 insertions with L-R polarity in the A/T-rich zone, no IS1 insertions with the reverse (R-L) orientation were found in the A/T-rich patch. All Bgl+ insertions with L-R orientation were clustered between positions +10 and +51 of the bglC gene transcript (Fig. 3A, lane 4). These insertions map to the leader region of the bglC transcript (Fig. 3B) (29). Thus, like those of Mu, IS1 insertions have a dramatic orientation bias in vivo, and this holds for both selected and nonselected transposition events in vivo.

Four conclusions about IS target selection in the bgl region can be drawn from these data. First, in liquid culture, IS transposition occurs late in stationary phase. On selective salicin plates, those insertions that produced a Bgl+ phenotype, and kept accumulating even after 7 days, were a small subset of the unselected IS1 transposition population. Second, IS insertions have a strong orientation bias. Unselected insertions, which were spaced at roughly 100-bp intervals, were found in only one orientation. Moreover, selected insertions in the A/T-rich patch were exclusively oriented R-L, while inserts that activated expression from inside the bglC transcription start were all oriented exclusively L-R. Third, the strongest activating mutations (the ones associated with the fastest growth rates on minimal salicin plates) occurred in the middle of the A/T-rich zone. Strains with IS1 insertions upstream of the CAP binding site grew faster than those with IS1 insertions with L-R polarity in the bglC transcript. Of the four IS1 insertions occurring in this region, the insertion at position −121, which is near the border of the A/T-rich patch (Fig. 2), was associated with the slowest growth rate (Fig. 4A).

Influence of IS1 insertions on bgl Muprints.

Two nonexclusive explanations could account for the bias in Mu orientation near bgl. First, there may be an intrinsic asymmetry in the Mu transposition mechanism that causes L-R bias when the virus integrates near an A/T-rich region. Second, proteins that bind to the bgl operon to silence transcription might interact with transposition proteins in either negative or positive ways to cause a Mu site and orientation bias. To test these two possibilities, we analyzed Muprints of the bgl region in strains carrying one of four activating IS1 insertions in the A/T-rich region (Fig. 5). When Muprinting templates are carefully matched, PCR products are quantitatively comparable, as shown by our analysis of transposition immunity in the his-cob region of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (20). DNA templates were matched by carrying out control reactions with primers that target the proU region of the chromosome (results not shown). Each IS1 mutant strain tested had the R-L hot spot at position −68, but each IS1 insertion showed diminished intensity of Mu transposition at this position (Fig. 5, left panel, lanes 2 to 5). At first approximation, the greater the degree of bgl activation, the less Mu transposition into the −68 hot spot occurred; this hot spot was at least fivefold less intense in mutants with IS1 at positions −89, −91, and −100 than in the WT. For the L-R orientation, shown for the BglC1-MuR primer combination, strains with a disrupted A/T-rich zone lacked the hot spots near the −150 site; this was not unexpected because the original target sequences are displaced about 1 kb upstream by the IS1 insertion. However, the IS1 mutant with an insertion at position −121 has a nearly complete A/T-rich region, and a new cluster of three hot spots that were about 30% as efficient as Mu transposition targets in the WT appeared inside the IS1 sequence (Fig. 5, right panel, lane 5). These results suggest that the integrity of the A/T-rich zone influences both the silencing of bgl expression and the efficiency of Mu transposition near bgl.

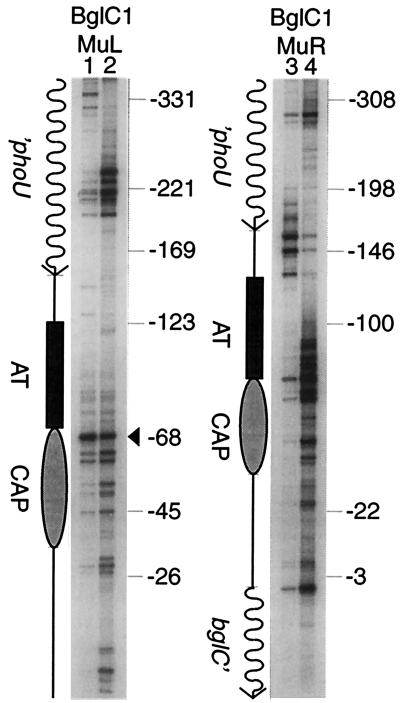

FIG. 5.

Activating IS insertions reduce Mu transposition at the CAP binding site to different extents. Muprint reactions were carried out with primers BglC1 and MuL (left panel) or BglC1 and MuR (right panel). Muprints were done with template from WT strain NH1126 (lane 1) or from strains activated for Bgl expression by IS1 insertion (NH3285 [lane 2], NH3286 [lane 3], NH3287 [lane 4], and NH3288 [lane 5]). Markers on the right indicate the positions of Mu insertion sites relative to the bglC transcription start (+1). The arrowhead next to the left panel indicates the strong Mu hot spot within the CAP binding site, at position −68 with respect to the transcription start for bgl.

In vitro Muprints of bgl.

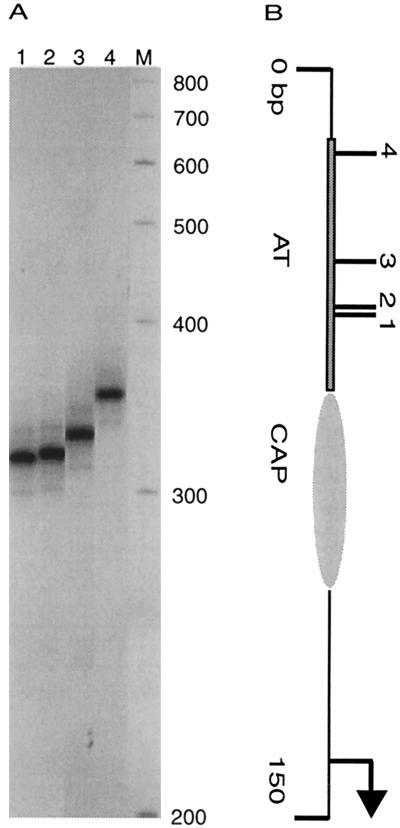

To test the influence on Mu transposition of factors bound near bgl, we compared in vivo Muprints with in vitro Muprints generated using purified components and a supercoiled plasmid containing the bgl control region as a target. In vitro transposition complexes for this experiment were made in the lab of George Chaconas, and after deproteinization they were subjected to PCR analysis. For the R-L orientation, the in vitro and in vivo Muprint patterns were remarkably similar (Fig. 6, lanes 1 and 2). The major hot spot at position −68 was an excellent target in vitro. In addition, there were bands both upstream in the phoU gene and in the vicinity of the CAP site and early bglC transcript that were more efficient targets in vitro than in vivo. These data suggest that chromatin structure protects specific target sites from transposition in vivo. For the L-R orientation, which was revealed by the BglC1-MuR primer combination, the in vitro pattern was quite different from that seen in vivo. The major hot spot at position −152 was visible in vitro, but the five-hot-spot cluster was much less prominent than it was in vivo, suggesting that chromatin enhances transposition at this location in vivo (Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 4). However, a cluster of hot spots was found in the proximal half of the A/T-rich region, and this cluster extended through the CAP binding site. Despite its lack of a consensus site (Fig. 2), this region was an excellent target for Mu transposition in vitro. Therefore, chromatin appears to exert a strong inhibitory effect on Mu transposition within the A/T-rich zone, and chromatin structure might create hot spots as well.

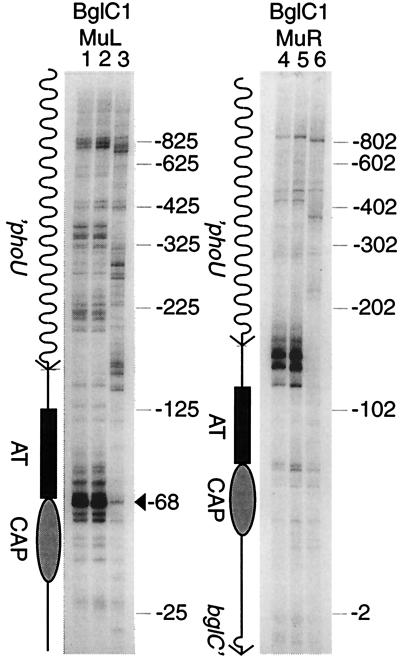

FIG. 6.

Comparison of in vivo and in vitro Muprint patterns at the bgl control region. Muprint reactions were carried out with either primer pair BglC1-MuL (lanes 1 and 2) or primer pair BglC1-MuR (lanes 3 and 4). Templates for Muprint reactions underwent Mu transposition either in vivo (lanes 1 and 3) or in vitro (lanes 2 and 4). Also shown (to scale) is the DNA segment with the phoU gene, the bglC gene, the A/T-rich region (AT), and the CAP binding site (CAP) marked. Markers on the side indicate insertions relative to the bglC transcription start site (+1).

Deletion of the A/T-rich tract.

The combined results from in vitro and in vivo Muprints suggested that the A/T-rich patch influences Mu transposition patterns. To directly test this hypothesis, we deleted a 56-bp segment of the region upstream of the bgl operon by using a single-stranded oligonucleotide and the lambda Red recombination system described by Yu et al. (31). Four of the five in vivo 5-bp duplication targets for Mu insertion remained in the region upstream of bglC, but the 80% A/T segment was lost (Fig. 2). Again, control reactions were done with the DNA templates to match Muprint intensity in the proU region of the chromosome. The striking result was that hot spots for Mu almost disappeared in the A/T deletion mutant. A weak reaction was detectable in the A/T deletion mutant at position −68, but the intensity of this hot spot was diminished much more than 10-fold relative to the WT pattern (Fig. 7; compare lanes 1 and 3). Even more striking were hot spots upstream of the A/T-rich patch, which correspond to positions −125, −141, −152, and −169 in the WT sequence. At three of these positions, the insertions disappeared completely (Fig. 7; compare lanes 4 and 6), whereas the fourth site, at −125, has been deleted in the A/T deletion strain. This is compelling evidence that the A/T-rich region (plus associated proteins in vivo) is responsible for Mu's selection of the bgl operator as a high-affinity insertion site.

FIG. 7.

Effect of a mutation in hns and a deletion of the A/T-rich patch on Mu transposition near the bgl promoter. Muprint reactions were carried out with either BglC1 and MuL (lanes 1 to 3) or BglC1 and MuR (lanes 4 to 6). The template for Muprint reactions was WT strain NH1126 (lanes 1 and 4), hns-651 mutant NH3386 (lanes 2 and 5), or the ΔAT derivative NH3388 (lanes 3 and 6). Markers on the right side indicate Mu insertion sites relative to the bglC transcription start in the WT strain. The arrowhead in the left panel indicates the strong Mu hot spot within the CAP binding site (−68). Also shown is the DNA segment, drawn to scale, with phoU, bglC, the A/T-rich region (AT), and the CAP binding site (CAP) indicated.

We also tested the impact of the hns-651 mutation on chromosome structure at bgl. This allele was introduced into the MC4100 background by P1 transduction and subsequent selection for a linked Tn10-derived tetracycline resistance gene (in strain NH3386.) The hns mutant caused a weak activation of the bgl operon, which was evidenced by slow growth on minimal plates with salicin as the sole carbon source. We have noted strain-dependent effects of moving identical hns alleles into E. coli strains with different backgrounds. In MC4100-derived strains, we saw no measurable influence of hns-651 on Mu transposition patterns (Fig. 7; compare lanes 1 and 2 and lanes 4 and 5). Thus, something other than H-NS protein must bind to the A/T-rich patch to influence Mu transposition patterns.

DISCUSSION

Mu and IS1 transposons exhibit two striking features in the region that controls transcription of the bgl operon. First, both elements have pronounced orientation bias. PCR profiles for IS1 transposition after 24 h of stationary-phase growth show that the element transposes with widely spaced target sites in the region surrounding the bgl operon (Fig. 3). In a population that is under selection for growth with salicin, the most prominent insertions are found to lie within the A/T-rich patch, and all have only one orientation. For Mu, six hot spots flank the 80-bp A/T-rich DNA segment. On the 5′ side of this A/T patch, Mu inserts into five target sites with L-R orientation, while on the opposite side of the A/T-rich patch, a single hot spot is oriented R-L (Fig. 1 and 2). This pattern and orientation bias persisted when transposition reactions were carried out in an in vitro system with a bgl target region cloned in a plasmid (Fig. 6). Second, numerous Mu transposition targets in the 5′-proximal segment of the bglC gene were much less prominent in vivo than in vitro, while several sites were stronger in vivo than in vitro (Fig. 6). What mechanisms cause these striking patterns?

To explain the clustering of Mu L-R hot spots and the single R-L hot spot, there must be asymmetry in the MuA transposase-DNA complex (see reference 7 for a recent review). Several factors might contribute to asymmetry. First, the arrangements of transposase binding sites at the left and right ends of Mu are different. Moreover, near Mu's left end is a supercoil-dependent high-affinity site for HU protein that is not duplicated at the right end (14). Both facts suggest that there are structural differences which could skew type I transpososome interactions with target DNA.

Second, an asymmetric (and as-yet-unrecognized) DNA-binding consensus sequence for Mu transposition proteins could exist. In target site selection by Mu and Tn10, preferred transposase cleavage sites have been noted. Tn10 transposase recognizes a 9-bp sequence with a defined 6-bp inverted symmetric sequence, 5′-NGCTNAGCN-3′, and Mu creates 5-bp duplications according to a symmetric consensus, 5′-NYG/CRN-3′, where N is any nucleotide, Y is a pyrimidine, R is a purine, and G/C represents either G or C. For Tn10, sequences flanking the 9-bp core site (by about 6 bp on either side) clearly exert an influence on target selection (4). However, for Mu, a target preference restricted to 20 bp near a 5-bp consensus sequence fails to explain the specificity observed in vivo and in vitro. Mu's orientation bias is focused on the 80-bp A/T-rich patch (Fig. 1 and 2). Of the six hot spots identified, four fit the consensus rules (Fig. 2); six consensus sites are not utilized, and many nonconsensus sites in the A/T-rich 80 bp are efficient targets for the in vitro transposition system (Fig. 6).

Asymmetry might also be caused by interaction of Mu B with target DNA. Mu B selects transposition target sites after binding DNA and hydrolyzing ATP in a cooperative reaction (1). Like the highly cooperative RecA protein interactions that make filaments on partially single-stranded DNA (15), the Mu B protein's entry and departure from DNA substrates might be influenced by DNA sequences or structures.

In addition to an asymmetric transposition complex, other factors are needed to explain the differences in target selection seen for in vitro and in vivo Mu transposition reactions. Because certain sites are better transposition targets in vitro than in vivo (Fig. 6), a barrier(s) must exist in vivo that is missing in vitro. Evidence from several labs indicates that proteins bound to the A/T-rich region generate a chromatin structure that resists transcription (6, 28). Muprints confirmed these observations in three ways that are summarized in Fig. 8. First, when the A/T-rich patch is disrupted by an IS1 insertion that activates bgl expression, Mu transposition at position −68 is diminished severalfold. Second, when the A/T-rich patch is nearly full size, a new R-L hot-spot cluster appears in the IS1 sequences at about the −150 position (Fig. 5, right panel, lane 5). Third, when the A/T-rich segment is eliminated, all Mu hot spots disappear or dramatically weaken, even though the Mu 5-bp consensus and flanking sites remain (Fig. 7). Thus, the A/T-rich region is responsible for Mu target selection near the bgl operon.

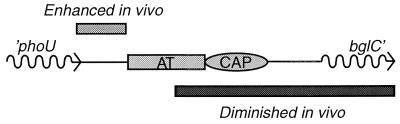

FIG. 8.

Map of the bgl promoter showing target segments that are either enhanced (above the map) or diminished (below the map) relative to in vitro Mu transposition efficiencies. AT, A/T-rich region; CAP, CAP binding site.

In E. coli and other bacteria, A/T-rich sequences are often positioned near the control regions of genes. Proteins credited with influencing general chromosome condensation and modulating gene expression include HU, H-NS, IHF, Lrp, FIS, and DPS. The abundance of each of these proteins changes with growth phase (3), and pinning down the mechanism by which these proteins modulate gene expression has been a difficult challenge. Creating the proper chromatin structure in vitro has been a daunting challenge, primarily because there has been no physical assay to determine when the proper structure exists. Muprinting now provides such an assay. Experiments are under way to see if properly organized chromatin structures can be isolated directly from E. coli cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant (MCB-9604875) from the National Science Foundation.

We thank George Chaconas and A. Millner for performing in vitro Mu transposition reactions. We thank Andrew Wright for the gift of plasmids and an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the A/T deletion experiment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adzuma K, Mizuuchi K. Steady-state kinetic analysis of ATP hydrolysis by the B protein of bacteriophage Mu. Involvement of protein oligomerization in the ATPase cycle. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6159–6167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amster-Choder O, Wright A. Modulation of the dimerization of a transcriptional antiterminator protein by phosphorylation. Science. 1992;257:1395–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.1382312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azam T A, Iwata A, Nishimura A, Ueda S, Ishihama A. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6361–6370. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6361-6370.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender J, Kleckner N. Tn10 insertion specificity is strongly dependent upon sequences immediately adjacent to the target-site consensus sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caramel A, Schnetz K. Lac and lambda repressors relieve silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter. Activation by alteration of a repressing nucleoprotein complex. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:875–883. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaconas G, Lavoie B D, Watson M A. DNA transposition: jumping gene machine, some assembly required. Curr Biol. 1996;6:817–820. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00603-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark J M. Novel non-templated nucleotide addition reactions catalyzed by procaryotic and eucaryotic DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9677–9686. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiNardo S, Voelkel K A, Sternglanz R, Reynolds A E, Wright A. Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I mutants have compensatory mutations in DNA gyrase genes. Cell. 1982;31:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emr S D, Silhavy T J. Mutations affecting localization of an Escherichia coli outer membrane protein, the bacteriophage λ receptor. J Mol Biol. 1980;141:63–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(80)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giel M, Desnoyer M, Lopilato J. A mutation in a new gene, bglJ, activates the bgl operon in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics. 1996;143:627–635. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins C F, Dorman C J, Stirling D A, Waddell L, Booth I R, May G, Bremer E. A physiological role for DNA supercoiling in the osmotic regulation of gene expression in S. typhimurium and E. coli. Cell. 1988;52:569–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90470-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houman F, Diaz-Torres M R, Wright A. Transcriptional antitermination in the bgl operon of E. coli is modulated by a specific RNA binding protein. Cell. 1990;62:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90392-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobryn K, Lavoie B D, Chaconas G. Supercoiling-dependent site-specific binding of HU to naked Mu DNA. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:777–784. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauder S D, Kowalczykowski S C. Asymmetry in the RecA protein-DNA filament. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5450–5458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leach D, Symonds N. The isolation and characterization of a plaque-forming derivative of bacteriophage Mu carrying a fragment of Tn3 conferring ampicillin resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;172:172–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00268280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopilato J, Wright A. Mechanisms of activation of the cryptic bgl operon of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Drlica K, Riley M, editors. The bacterial chromosome. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnuson V L, Ally D S, Nylund S J, Karanjawala Z E, Rayman J B, Knapp J I, Lowe A, Ghosh S, Collins F S. Substrate nucleotide-determined non-templated addition of adenine by Taq DNA polymerase: implications for PCR-based genotyping and cloning. BioTechniques. 1996;21:700–709. doi: 10.2144/96214rr03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahadevan S, Reynolds A E, Wright A. Positive and negative regulation of the bgl operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2570–2578. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2570-2578.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manna D, Higgins N P. Phage Mu transposition immunity reflects supercoil domain structure of the chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:595–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millner A, Chaconas G. Disruption of target DNA binding in Mu DNA transposition by alteration of position 99 in the Mu B protein. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:233–243. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynolds A E, Felton J, Wright A. Insertion of DNA activates the cryptic bgl operon of E. coli K-12. Nature. 1981;293:625–629. doi: 10.1038/293625a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds A E, Mahadevan S, Felton J, Wright A. Activation of the cryptic bgl operon: insertion sequences, point mutations, and changes in supercoiling affect promoter strength. In: Simon M, Herskowitz I, editors. Genome rearrangement. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss; 1985. pp. 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds A E, Mahadevan S, LeGrice S F, Wright A. Enhancement of bacterial gene expression by insertion elements or by mutation in a CAP-cAMP binding site. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salyers A A, Amábile-Cuevas C F. Why are antibiotic resistance genes so resistant to elimination? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2321–2325. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnetz K, Rak B. Regulation of the bgl operon of Escherichia coli by transcriptional antitermination. EMBO J. 1988;7:3271–3277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnetz K, Rak B. IS5: a mobile enhancer of transcription in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1244–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnetz K, Wang J C. Silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter: effects of template supercoiling and cell extracts on promoter activity in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2422–2428. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz E, Herberger C, Rak B. Second-element turn-on of gene expression in an IS1 insertion mutant. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;211:282–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00330605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Higgins N P. ‘Muprints’ of the lac operon demonstrate physiological control over the randomness of in vivo transposition. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:665–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu D G, Ellis H M, Lee E-C, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Court D L. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]