Abstract

Background: Among cancer-related deaths, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks fourth, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treatment is an important complementary alternative therapy for HCC. Curcumin is a natural ingredient extracted from Curcuma longa with anti-HCC activity, while the therapeutic mechanisms of curcumin remain unclear, especially on ferroptosis and cuproptosis. Methods: Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of curcumin treatment in PLC, KMCH, and Huh7 cells were identified, respectively. The common genes among them were then obtained to perform functional enrichment analysis and prognostic analysis. Moreover, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was carried out for the construction of the co-expression network. The ferroptosis potential index (FPI) and the cuproptosis potential index (CPI) were subsequently used to quantitatively analyze the levels of ferroptosis and cuproptosis. Finally, single-cell transcriptome analysis of liver cancer was conducted. Results: We first identified 702, 515, and 721 DEGs from curcumin-treated PLC, KMCH, and Huh7 cells, respectively. Among them, HMOX1, CYP1A1, HMGCS2, LCN2, and MTTP may play an essential role in metal ion homeostasis. By WGCNA, grey60 co-expression module was associated with curcumin treatment and involved in the regulation of ion homeostasis. Furthermore, FPI and CPI assessment showed that curcumin had cell-specific effects on ferroptosis and cuproptosis in different HCC cells. In addition, there are also significant differences in ferroptosis and cuproptosis levels among 16 HCC cell subtypes according to single-cell transcriptome data analysis. Conclusions: We developed CPI and combined it with FPI to quantitatively analyze curcumin-treated HCC cells. It was found that ferroptosis and cuproptosis, two known metal ion-mediated forms of programmed cell death, may have a vital effect in treating HCC with curcumin, and there are significant differences in various liver cancer cell types and curcumin treatment which should be considered in the clinical application of curcumin.

Keywords: curcumin, hepatocellular carcinoma, ferroptosis, cuproptosis

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks fourth among cancer-related deaths worldwide, accounting about 90% of all primary liver cancers [1,2]. As an aggressive and malignant tumor, HCC incidence has been rising in recent decades [3,4]. Most confirmed HCC patients are in advanced stage, although radical surgery is the effective therapy for HCC, the effectiveness of which has decreased significantly [5,6]. Besides surgical intervention, drug treatment for HCC is another effective choice. [7]. Current first-line therapy drug against advanced HCC is sorafenib (a multi-kinase inhibitor) [8], but its curative effect is not satisfactory [9,10]. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), a complementary alternative therapy, shows significant benefits on prolonging median survival time and improving quality of life among patients with HCC [11].

Curcumin is well-known to be a polyphenol obtained from the plant Curcuma longa and has long been used to treat a wide spectrum of chronic diseases, including cancer [12]. Multiple mechanisms have been identified by numerous studies to reveal the anti-liver cancer effects of curcumin. For instance, curcumin could inhibit the proliferation of HCC cells via regulating non-coding RNA [13] and mitochondrial apoptosis [14]. Curcumin also has an impact on the tumor microenvironment [15]. Multiple molecular signaling pathways, including the Wnt/β-catenin [13], PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β [14], and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) [15] pathways, have been shown to be involved in curcumin-mediated liver protection.

Ferroptosis, identified and named a decade ago, is a unique type of programmed cell death primarily driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation [16,17]. Growing evidence has revealed that ferroptosis plays a crucial part in treatment with curcumin against various cancers, such as non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [18], clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) [19], and breast cancer [20,21]. Despite these findings, however, the precise action of curcumin-modulated ferroptosis in HCC remains unclear. As another metal ion-dependent cell death, cuproptosis (a distinct form of copper-induced cell death) was recently reported by Tsvetkov et al. [22]. Some research has suggested an underlying connection between HCC and cuproptosis [23,24]. Therefore, further study on the effect of ferroptosis and cuproptosis in treating HCC with curcumin is necessary.

This study was performed to first explore the transcriptomic change in various HCC cells after curcumin treatment and then explore the involved biological processes, focusing on the underlying role of ferroptosis and cuproptosis in curcumin against HCC. Finally, we investigated the differences in ferroptosis and cuproptosis levels among cell subtypes of HCC.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in HCC Cells Treated with Curcumin

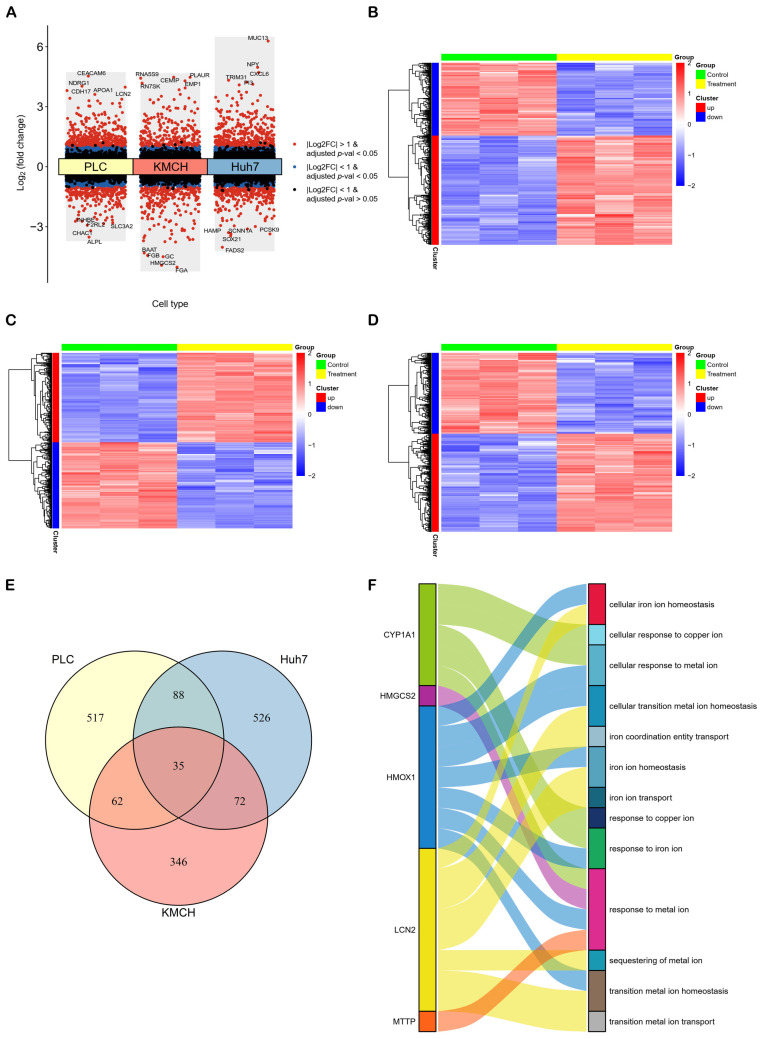

Based on the thresholds of |log2 fold change| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05, we first identified 702 (421 up-regulated and 281 down-regulated), 515 (263 up-regulated and 252 down-regulated), 721 (395 up-regulated and 326 down-regulated) DEGs from curcumin-treated PLC, KMCH and Huh7 cells, respectively (Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). A volcano plot (Figure 1A) and three heatmaps (Figure 1B–D) were established to exhibit the distribution of DEGs in different liver cancer cell lines with curcumin treatment. Furthermore, we found that 35 genes were identical among the DEGs of the three cell lines (Figure 1E). Among the 35 genes, CYP1A1, HMGCS2, HMOX1, LCN2, and MTTP could be enriched in iron and copper ion related biological processes (Figure 1F), implicating the curcumin-mediated regulation of metal ion homeostasis through these genes.

Figure 1.

Differential expression analysis and functional annotation. (A) A volcano plot and (B–D) three heatmaps of DEGs showed that significant changes in mRNAs caused by curcumin in PLC, KMCH and Huh7 cell lines, respectively. (E) Thirty-five common genes were significantly regulated by curcumin in all three cell lines. (F) Among the 35 genes, CYP1A1, HMGCS2, HMOX1, LCN2 and MTTP were enriched in biological processes related to metal ion homeostasis.

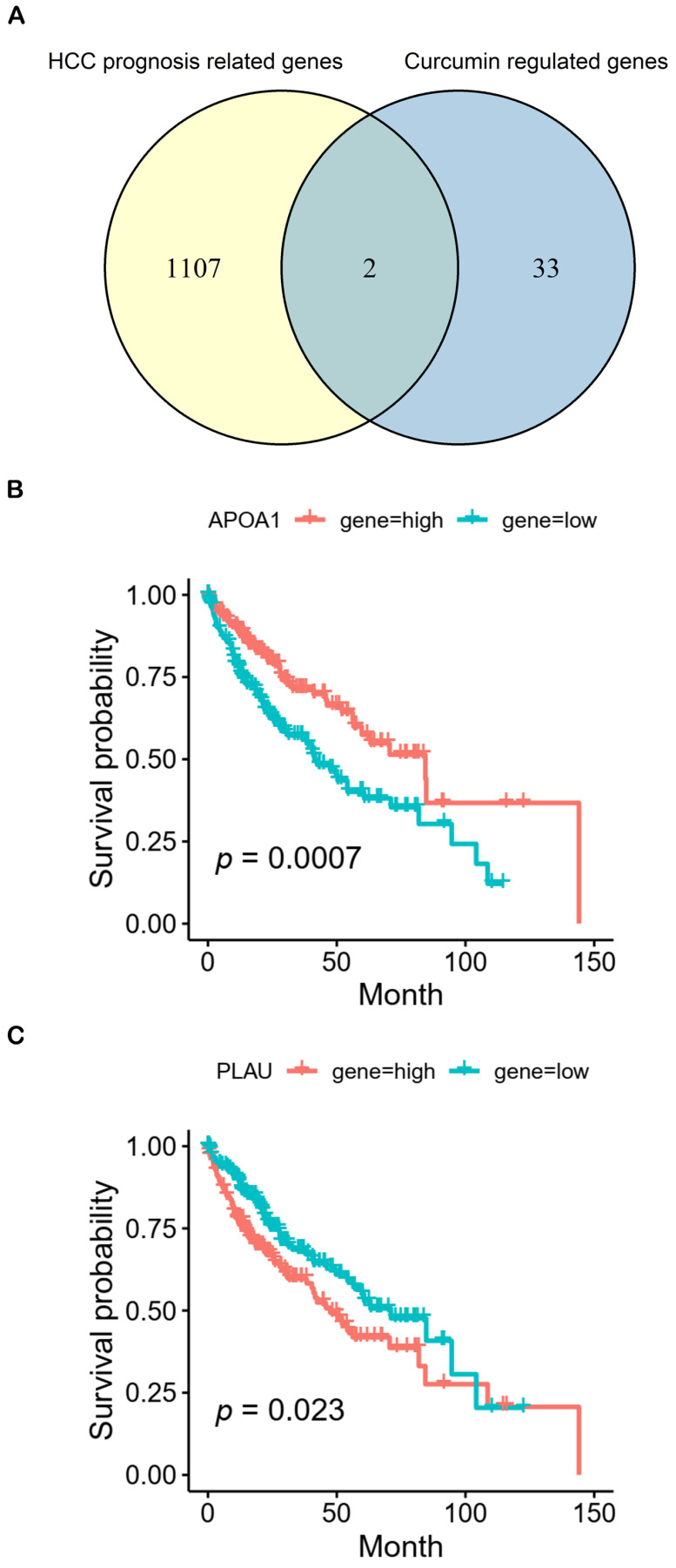

In addition, we also analyzed the potential role of 35 DEGs in HCC prognosis. Hence, 1109 genes (p < 0.05) associated with HCC prognosis were identified from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) in total (Table S2). Based on the intersection of 1109 HCC prognosis related genes and 35 DEGs, APOA1 and PLAU were common genes (Figure 2A). Figure 2B shows that high expression of APOA1 and low expression of PLAU were related to the good prognosis of HCC. These results implied that curcumin might regulate other pathways than ferroptosis and cuproptosis to affect prognosis via APOA1 and PLAU.

Figure 2.

Prognostic analysis. (A) There are two common genes (APOA1 and PLAU) between 1109 genes (p < 0.05) related to prognosis of HCC (yellow) and 35 DEGs (blue). (B,C) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival for APOA1 and PLAU, respectively.

2.2. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) of HCC Cells after Curcumin Treatment

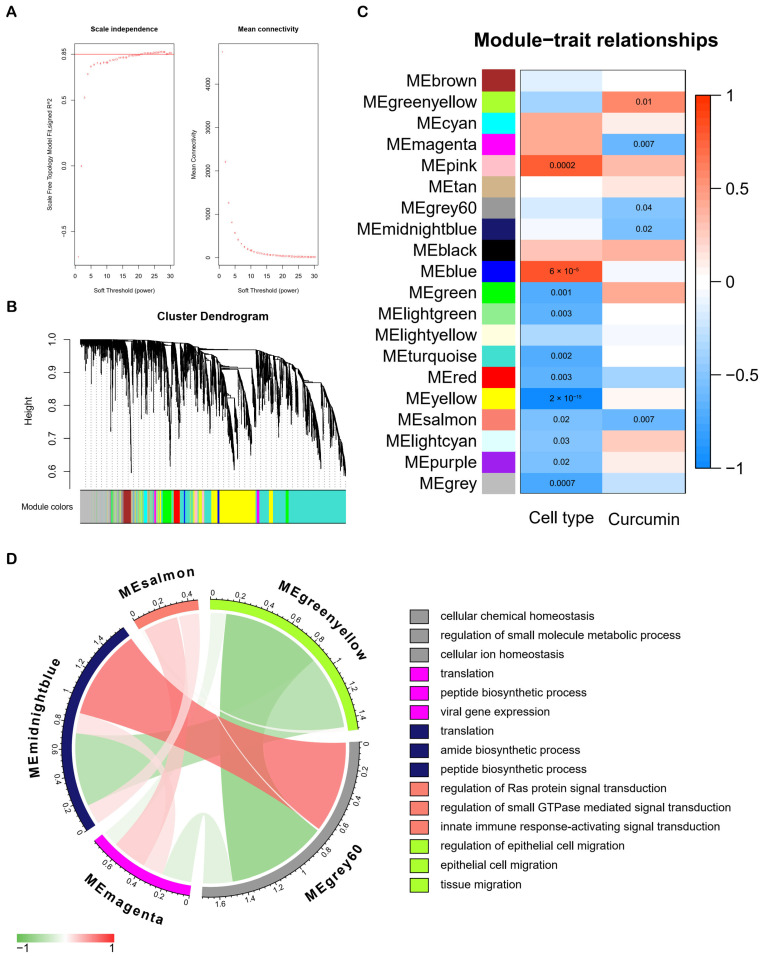

WGCNA was performed in order to build the co-expression network. The power of β = 21 (scale-free R2 = 0.85) was selected as the soft-thresholding parameter in order to ensure a scale-free network (Figure 3A). Hence, 20 modules in total were constructed through hierarchical clustering, and the number of genes in each module ranged from 40 to 5429 (Figure 3B). According to the eigengene values (the first principal component of the module gene expression level) of modules, we associated the co-expression modules with traits (Figure 3C). MEgreenyellow, MEmagenta, MEgrey60, MEmidnightblue, and MEsalmon were significantly correlated with curcumin treatment (Figure 3C). Figure 3D shows the correlation among the five modules, and we performed module functional annotation using HumanBase for the five modules. Interestingly, the function of the grey60 module was annotated as cellular chemical homeostasis, regulation of small molecule metabolic process and cellular ion homeostasis (Figure 3D), reflecting the modulation of curcumin for ion homeostasis as well.

Figure 3.

WGCNA analysis and module annotation. (A) The soft threshold is set to 21 for WGCNA analysis. (B) Twenty modules were constructed through hierarchical clustering. (C) The heatmap showed the correlations between modules and traits. (D) Correlations among five modules related to curcumin treatment and annotations.

2.3. Curcumin Promotes Ferroptosis of Part of HCC Cells

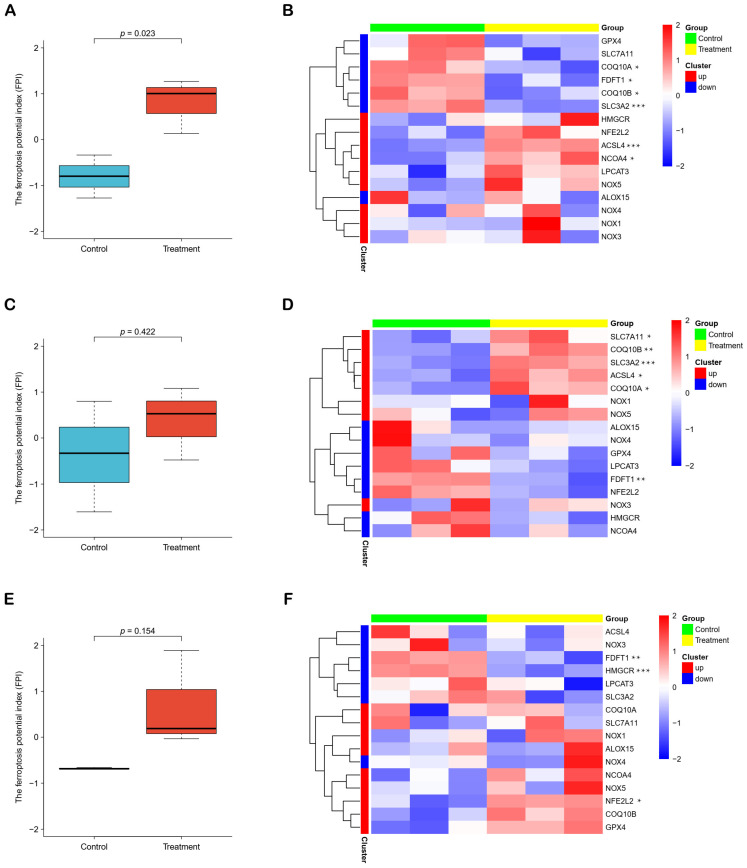

Given that iron ion related biological processes was involved in treatment with curcumin against HCC, we further explored the effect of curcumin on ferroptosis of HCC and calculated the Ferroptosis Potential Index (FPI) to assess ferroptosis level of liver cancer cells with or without curcumin treatment. FPI was significantly increased in PLC cells after curcumin treatment (Figure 4A), while remained unchanged in KMCH and Huh7 cells (Figure 4C,E). Heatmaps displayed the expression of genes used to calculate FPI in different cell lines (Figure 4B,D,F). These results suggested that curcumin exerted different effects on ferroptosis due to HCC cellular heterogeneity.

Figure 4.

The ferroptosis potential index. (A,C,E) Three boxplots showed the levels of ferroptosis in PLC, KMCH and Huh7 cell lines after curcumin treatment, respectively. (B,D,F) Three heatmaps showed the expression of genes used to calculate FPI. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

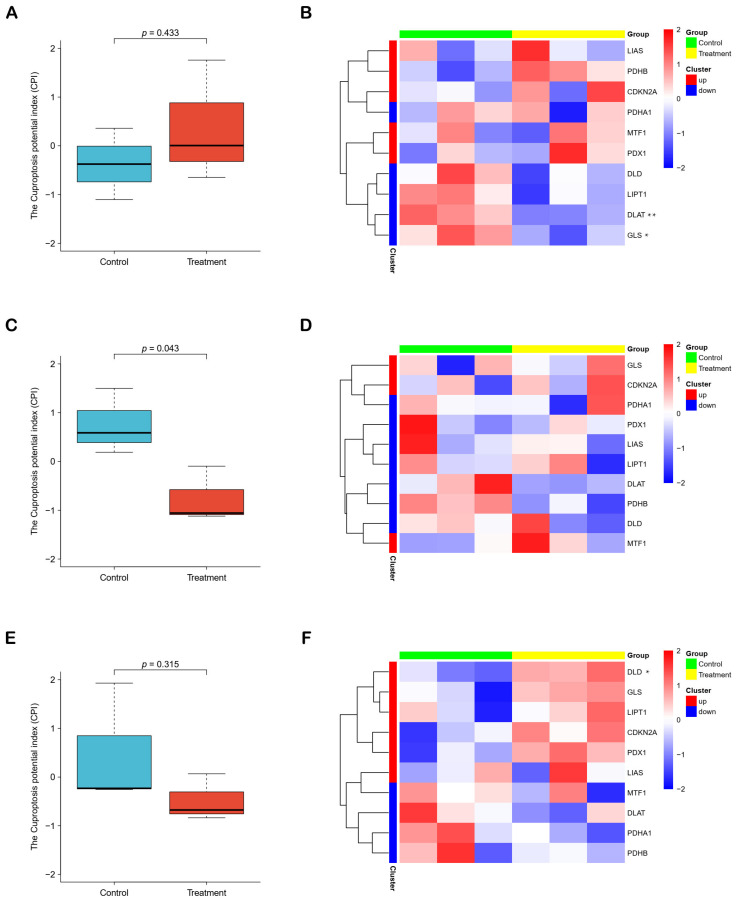

2.4. Cuproptosis Potential Index (CPI) Reflects the Cuproptosis Levels of HCC Cells

Except FPI, we developed an index (CPI) to quantitatively assess the level of cuproptosis. In KMCH cells, we found a significant reduction in the CPI of the curcumin treatment group (Figure 5B). Nevertheless, there was no significant change of CPI in curcumin-treated PLC and Huh7 cells (Figure 5A,E). Heatmaps showed the expression of genes used to calculate CPI in different cell lines (Figure 5B,D,F). These results demonstrated that the role of curcumin on cuproptosis was cell-specific as well.

Figure 5.

The cuproptosis potential index. (A,C,E) Three boxplots showed the levels of cuproptosis in PLC, KMCH and Huh7 cell lines after curcumin treatment, respectively. (B,D,F) Three heatmaps showed the expression of genes used to calculate CPI. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

2.5. Single-Cell RNA Analysis of HCC Cells on Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis

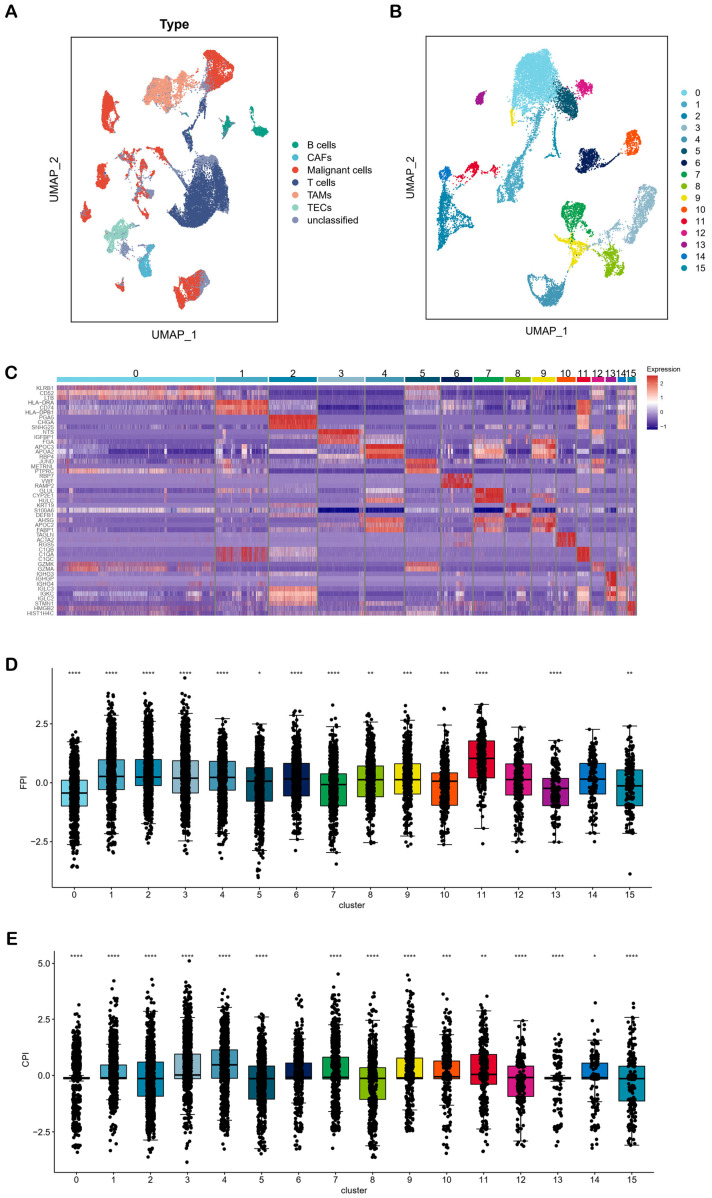

Considering the cell specificity of ferroptosis and cuproptosis in HCC, we performed single-cell transcriptome analysis. Based on the GSE151530 dataset, we performed a UMAP dimensionality reduction analysis on 56,721 single cells from 46 HCC patients (Figure 6A). After extracting the malignant cells and performing subcluster analysis, we were able to identify 16 subclusters (Figure 6B). By calculating the marker genes of these 16 subclusters, we drew a heatmap and found that the top three marker genes were able to separate the subclusters significantly, indicating that the subclusters were reliable (Figure 6C, Table S3). We calculated FPI and CPI for each subcluster and observed that the levels of ferroptosis and cuproptosis differed significantly among the different subclusters (Figure 6D,E). These results implied that different types of liver cancer cells had specificity in ferroptosis and cuproptosis levels, which needs to be considered in curcumin treatment.

Figure 6.

Single cell transcriptome analysis of HCC. (A) The UMAP plot of 56,721 single cells from 46 liver tumor samples showed 7 cell types, including B cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), malignant cells, T cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), tumor-associated endothelial cells (TECs) and unclassified. (B) The UMAP plot showed 16 subcluster of malignant cells. (C) The heatmap showed the marker genes with significant differences among the 16 subclusters. (D,E) FPI and CPI were significantly different among the 16 subclusters. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001. **** p < 0.0001.

3. Discussion

There is a growing body of convincing evidence that natural compounds could be seen as promising drug candidates for a variety of diseases including cancer. Curcumin, an active component isolated from Curcuma longa, exerted anti-cancer activities orchestrated through key signaling pathways related to cancer [12]. Although there were advances in curcumin-mediated anti-liver cancer effects via different mechanisms [13,14,15], challenges remain ahead regarding the understanding of molecular mechanisms that would be pharmacologically necessary to explain the therapeutic potential of curcumin against HCC.

In this study, we first found that curcumin induced changes in the expression of CYP1A1, HMGCS2, HMOX1, LCN2, and MTTP, which are enriched in metal ion homeostasis, in all three liver cancer cell lines (Figure 1F). In addition, we identified four co-expression modules (greenyellow, magenta, grey60 and midnightblue) associated with curcumin treatment but not with cell type by WGCNA analysis (Figure 3C). Among them, the grey60 module was involved in the regulation of cellular ion homeostasis in the liver. These analyses suggested that ion homeostasis might play a crucial part in treating HCC with curcumin. Ferroptosis and cuproptosis are two forms of metal ion-mediated programmed cell death. It is worth noting that curcumin could affect the ferroptosis pathway in a variety of cancers. For example, in NSCLC, curcumin could induce ferroptosis via autophagic activation to improve the therapeutic efficacy [18]. In ccRCC, curcumin promoted ferroptosis to reverse sunitinib resistance [19]. In breast cancer, curcumin suppressed tumorigenesis via enhancing SLC1A5-mediated ferroptosis [21]. Although there was no direct evidence that curcumin affected cancer development through cuproptosis, a study has shown that cuproptosis-related genes were closely associated with the prognosis and drug sensitivity of HCC [25]. On this basis, these results implied that ferroptosis and cuproptosis may be important pathways in its anti-HCC effect of curcumin.

As a stress-induced enzyme, heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) catalyzes the degradation of heme to carbon monoxide, iron, and biliverdin, a potential therapeutic target for many diseases [26]. Indeed, curcumin could activate ferroptosis in breast cancer cells, and HMOX1 could promote curcumin-induced ferroptosis [20]. EF24, a synthetic analogue of curcumin, induced ferroptosis through up-regulating HMOX1 in osteosarcoma cells [27]. In our study, the expression level of HMOX1 gene was significantly raised in all three curcumin-treated liver cancer cell lines (Table S1), and HMOX1 was enriched in these biological processes, such as cellular iron ion homeostasis, cellular transition metal ion homeostasis, cellular response to metal ion, iron ion homeostasis, response to iron ion, response to metal ion and transition metal ion homeostasis (Figure 1F), indicating the possibility that curcumin regulated ferroptosis via HMOX1.

Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) is highly expressed in adipose tissue and regulates lipid metabolism by promoting the transport of triglycerides between membrane vesicles. A recent study revealed that MTTP protein could inhibit ferroptosis and enhance chemoresistance in colorectal cancer [28]. Moreover, the overexpression of MTTP could reduce hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, implying that it may play an important role in the occurrence and development of HCC [29]. Lipocalin 2 (LCN2), a protein with antioxidant capacity, is upregulated under various cellular stress conditions, particularly in cancer. Valashedi et al. claimed that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of LCN2 significantly promoted erastin-mediated ferroptosis and enhanced cisplatin vulnerability in MDA-MB-231 (a kind of human breast cancer cell line) [30]. Yao et al. found that the LIFR/NF-κB/LCN2 axis could regulate the liver tumorigenesis and vulnerability to ferroptosis [31]. In addition, a recent study showed that there was a significant positive correlation between LCN2 protein and copper in serum [32]. Interestingly, several studies have shown that curcumin could obviously inhibit the expression of LCN2 (at both the protein and mRNA levels) in vivo and in vitro [33,34]. These studies suggest that curcumin may regulate ferroptosis and cuproptosis via LCN2 gene.

HMGCS2, or 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase 2, is known as a key ketogenic enzyme, mediating ketone production and regulating the proliferation and metastasis of HCC [35]. Recently, Duan et al. claimed that activated PPARa/HMGCS2/NRF2/ARE pathway might induce ferroptosis [36]. In addition, HMGCS2 (at both the protein and mRNA levels) may be involved in ceruloplasmin-mediated copper metabolism [37], implying that HMGCS2 may play a regulatory role in the process of ferroptosis and cuproptosis. Cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1 (CYP1A1) is one of the main P450 enzymes and is highly expressed in the liver and urinary bladder. A recent study reported that kynurenine could provoke the activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), the expression of CYP1A1, and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and ultimately lead to cell ferroptosis [38]. Furthermore, copper ion could significantly induce the expression of CYP1A1 mRNA [39], suggesting that CYP1A1 may be involved in cuproptosis.

To further explore the changes in the levels of ferroptosis and cuproptosis after curcumin treatment of hepatoma cells, we calculated FPI and developed CPI (Figure 4 and Figure 5). In addition, we found that some characterized events of ferroptosis were evoked in PLC cells (Figure S1A,B), and several signature pathways of cuproptosis were inhibited in KMCH cells (Figure S1C,D). These results further support the reliability of the FPI and CPI. The results demonstrated that curcumin could significantly promote the ferroptosis level of PLC cells and inhibit the cuproptosis level of KMCH cells, suggesting that curcumin was likely to affect HCC through ferroptosis and cuproptosis pathways. However, ferroptosis had no significant changes in curcumin-treated KMCH and Huh7 cells, and cuproptosis did not change significantly in curcumin-treated PLC and Huh7 cells, reflecting that ferroptosis and cuproptosis in different liver cancer cell types are differentially sensitive to curcumin treatment.

To confirm the cell-type specificity of ferroptosis and cuproptosis in HCC, we analyzed the data of single-cell transcriptome sequencing. Significant differences existed in levels of ferroptosis and cuproptosis among different cell subtypes of HCC (Figure 6D,E). A previous study also showed that HCC cell lines exposed to curcumin reacted differently, which were classified as sensitive or resistant [40]. The dual effects of curcumin on various HCC cell lines may be, at least in part, due to different ferroptosis and cuproptosis levels. Therefore, the specificity of ferroptosis and cuproptosis should be considered in the clinical application of curcumin.

At the phenotypic level, the article (public data source in our study) indicated that curcumin could significantly increase hepatoma cell death (PLC: 18% cell death, KMCH: 31% cell death, Huh7: 41% cell death) in vitro and inhibit the activity of cancer stem cells in vitro and in vivo [40]. These results suggest that curcumin could cause good overall killing effects on these hepatoma cells. In the three curcumin-treated liver cancer cell lines, 702, 515 and 721 DEGs were generated, respectively (Table S1). However, only 35 DEGs are shared among them (Figure 1E). Moreover, Figure 3C indicated that there are a large number of different gene co-expression networks in different hepatoma cell types, implying significant differences in the response of different cell types to curcumin. In addition, single-cell RNA analysis showed that ferroptosis and cuproptosis were significantly different among multiple liver cancer subtypes (Figure 6). Therefore, on the one hand, curcumin has a different ability to affect ferroptosis and cuproptosis in different liver cancer subtypes, and on the other hand, the anti-cancer effect of curcumin is exerted through multiple pathways.

In our study, we investigated the mechanism by which curcumin affected HCC via ferroptosis and cuproptosis. In addition to the metal ion-mediated programmed cell death, curcumin could affect HCC through other pathways. Curcumin effectively inhibits oncogenic NF-κB signaling and restrains stemness features in liver cancer [40]. Zhou et al. found that curcumin could restrain cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via regulating the miR-21-5p/SOX6 axis in HCC [41]. A recent study reported that curcumin could provoke mitochondrial apoptosis in HCC by BCLAF1-mediated PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway [14]. In addition, the gut microbiota is also involved in the treatment of HCC with curcumin. Jin et al. found that the bioavailability of curcumin could be improved with the help of gut microbiota in HCC [42]. Wu et al. reported that curcumin could inhibit the growth of HCC via regulating gut microbiota-mediated zinc homeostasis [43]. These results suggest that gut microbiota may play an essential role in the process of curcumin affecting ferroptosis and cuproptosis.

Additionally, we found that curcumin may regulate the prognosis of HCC through APOA1 and PLAU (Figure 2). Quantitative proteomic analysis showed that the expression of APOA1 protein was significantly down-regulated by 22% in HCC with hepatitis C virus (HCV) [44]. Guo et al. reported that the expression level of APOA1 mRNA in the serum of HCC patients with liver cancer was significantly lower than that of healthy people, and high expression of APOA1 mRNA obviously correlated with better overall survival in the Chinese cohort [45]. These independent studies support the credibility of our results. Although the correlation of APOA1 with HCC has been confirmed by several studies, the mechanisms of APOA1 downregulation in liver cancer remain incompletely clear. A study showed that hepatitis B virus (HBV) could induce the DNA hypermethylation of CpG island, leading to epigenetic silencing of APOA1 gene expression, and then contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) [46]. Since CHB is a major risk for liver cancer, it may be one of the mechanisms of APOA1 downregulation in liver cancer. It is worth noting that the expression of APOA1 protein was seven-fold higher in African American HCC patients compared to Caucasian American HCC patients [47], suggesting that the changes of APOA1 expression are not only cell type specific, but also race specific. In short, APOA1 may be a potential therapeutic target for HCC in spite of the fact that further evidence is needed. Interestingly, a study reported that curcumin could increase the expression of APOA1 in the sorafenib-treated mice and enhance the antitumor effects of sorafenib through regulating the metabolism and tumor microenvironment [48]. In liver cancer, there are not many studies related to the PLAU gene. It is worth noting that a study declared that the high expression of serum PLAU protein could be used to predict poor prognosis in HCC after resection [49]. Similarly, our results also showed that a high expression of PLAU was related to a poor prognosis in HCC. A study claimed that PLAU was associated with chronic inflammation in the liver [50]. Chronic inflammation is an important risk of HCC, so curcumin may improve the prognosis of HCC by regulating the inflammatory response through PLAU. These mechanisms are worth further investigation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of DEGs

GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accessed on 24 August 2022) provided DEGs of curcumin (Series: GSE59713, Samples: GSM1444129, GSM1444130, GSM1444131, GSM1444132, GSM1444133, GSM1444134, GSM1444141, GSM1444142, GSM1444143, GSM1444144, GSM1444145, GSM1444146, GSM1444147, GSM1444148, GSM1444149, GSM1444150, GSM1444151, GSM1444152,). In GSE59713, total RNA was isolated from KMCH, Huh7 and PLC cells treated with or without 25 μM curcumin for 72 h in vitro, and three liver cancer cell lines were significantly inhibited by curcumin [40]. Differential analysis was performed by limma R package (v.3.52.2) [51], and the thresholds of DEGs were |log2 fold change| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05.

4.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis

The biological process of Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed via clusterProfiler v.4.4.4 (a kind of R package) [52], and module functional annotation was performed using HumanBase (a data-driven, tissue-specific, and network-guided biological function annotation tool) [53].

4.3. Prognostic Analysis

The Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) data enabled us to identify 1109 genes (p < 0.05) associated with the prognosis of HCC using the Kaplan–Meier (K-M) survival curves. The survival curves of APOA1 and PLAU were visualized using survminer R package, version 0.4.9.

4.4. WGCNA

WGCNA is a system biology algorithm commonly used to examine the correlation between gene sets and clinical characteristics by constructing free-scale gene co-expression networks. The expression profile of mRNA was applied to build a gene co-expression network via the package WGCNA implemented in R software, and the version is 1.71 [54]. The WGCNA::blockwiseModules() function was used with the following settings: soft threshold power = 21, TOMType = “unsigned”, minModuleSize = 30, deepSplit = 4 and mergeCutHeight = 0.25.

4.5. The FPI Calculating

According to the previous work by Zekun Liu et al., we calculated the FPI [55]. The FPI was used to quantitatively reflect ferroptosis level via transcriptome data.

4.6. The CPI Constructing

We constructed the CPI by the expression for essential genes of cuproptosis, including positive components (PDX1, LIAS, LIPT1, DLD, DLAT, PDHA1, PDHB) and negative components (MTF1, GLS, CDKN2A) [22]. Through single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA), the enrichment score (ES) was calculated, including positively or negatively regulated cuproptosis. Then, normalized differences between the ES of the positive components minus negative components are referred to as the CPI.

4.7. Single-Cell RNA Analysis

We performed single-cell RNA analysis of liver cancer based on GEO dataset GSE151530 [56]. GSE151530 is an atlas of liver cancer, and a total of 46 tumor samples from HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients were profiled. Seurat R package (v.4.1.1) was used for data analysis [57].

5. Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that the regulation of ion homeostasis, especially on ferroptosis and cuproptosis, may play a crucial part in the treatment of HCC with curcumin. We quantitatively analyzed different HCC cell lines treated with curcumin and HCC cell subtypes by FPI and CPI. We found that the levels of ferroptosis and cuproptosis are cell specific in various liver cancer cell types and curcumin treatments. Our study is helpful to explore the potential mechanisms of natural compounds and provide preliminary data to assist their clinical application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28041623/s1, Table S1: DEGs from curcumin-treated PLC, KMCH and Huh7 cells; Table S2: Genes associated with HCC prognosis; Table S3: Marker genes of 16 subclusters of malignant cells; Figure S1: Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of characterized events in ferroptosis and cuproptosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Z.L. (Zhili Liu) and Z.L. (Zelin Lai); formal analysis, Z.L. (Zhili Liu) and H.M.; writing—original draft, Z.L. (Zhili Liu); writing—review & editing, H.M. and Z.L. (Zelin Lai); visualization, Z.L. (Zhili Liu) and H.M.; supervision, Z.L. (Zelin Lai); funding acquisition, Z.L. (Zelin Lai). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the GEO repository, GSE59713 and GSE151530.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M701643) to Zelin Lai.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Craig A.J., von Felden J., Garcia-Lezana T., Sarcognato S., Villanueva A. Tumour evolution in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:139–152. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sia D., Villanueva A., Friedman S.L., Llovet J.M. Liver cancer cell of origin, molecular class, and effects on patient prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:745–761. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z., Jiang Y., Yuan H., Fang Q., Cai N., Suo C., Jin L., Zhang T., Chen X. The trends in incidence of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 and implications for liver cancer prevention. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J., Tang W., Budhu A., Forgues M., Hernandez M.O., Candia J., Kim Y., Bowman E.D., Ambs S., Zhao Y., et al. A Viral Exposure Signature Defines Early Onset of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell. 2020;182:317–328.e310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jun L., Yang G., Zhisu L. The utility of serum exosomal microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;111:1221–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye Q., Ling S., Zheng S., Xu X. Liquid biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:114. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1043-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foerster F., Galle P.R. The Current Landscape of Clinical Trials for Systemic Treatment of HCC. Cancers. 2021;13:1962. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S.K., Jang J.W., Nam H., Sung P.S., Kim H.Y., Kwon J.H., Lee S.W., Song D.S., Kim C.W., Song M.J., et al. Sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma provides better prognosis after liver transplantation than without liver transplantation. Hepatol. Int. 2021;15:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimassa L., Personeni N., Czauderna C., Foerster F., Galle P. Systemic treatment of HCC in special populations. J. Hepatol. 2021;74:931–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z., Sun Y., Zhen H., Nie C. Network Pharmacology Integrated with Transcriptomics Deciphered the Potential Mechanism of Codonopsis pilosula against Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2022;2022:1340194. doi: 10.1155/2022/1340194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X., Li M., Wang X., Dang Z., Yu L., Wang X., Jiang Y., Yang Z. Effects of adjuvant traditional Chinese medicine therapy on long-term survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2019;62:152930. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weng W., Goel A. Curcumin and colorectal cancer: An update and current perspective on this natural medicine. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;80:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao J., Shi C.J., Li Y., Zhang F.W., Pan F.F., Fu W.M., Zhang J.F. LincROR Mediates the Suppressive Effects of Curcumin on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Through Inactivating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:847. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai C., Zhao J., Su J., Chen J., Cui X., Sun M., Zhang X. Curcumin induces mitochondrial apoptosis in human hepatoma cells through BCLAF1-mediated modulation of PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β signaling. Life Sci. 2022;306:120804. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao S., Duan W., Xu Q., Li X., Han L., Li W., Zhang D., Wang Z., Lei J. Curcumin Suppresses Hepatic Stellate Cell-Induced Hepatocarcinoma Angiogenesis and Invasion through Downregulating CTGF. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;2019:8148510. doi: 10.1155/2019/8148510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z., Ma H., Lai Z. Revealing the potential mechanism of Astragalus membranaceus improving prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma by combining transcriptomics and network pharmacology. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021;21:263. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03425-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockwell B.R. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell. 2022;185:2401–2421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang X., Ding H., Liang M., Chen X., Yan Y., Wan N., Chen Q., Zhang J., Cao J. Curcumin induces ferroptosis in non-small-cell lung cancer via activating autophagy. Thorac. Cancer. 2021;12:1219–1230. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu B., Zhu W.J., Peng Y.J., Cheng S.D. Curcumin reverses the sunitinib resistance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) through the induction of ferroptosis via the ADAMTS18 gene. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021;10:3158–3167. doi: 10.21037/tcr-21-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li R., Zhang J., Zhou Y., Gao Q., Wang R., Fu Y., Zheng L., Yu H. Transcriptome Investigation and In Vitro Verification of Curcumin-Induced HO-1 as a Feature of Ferroptosis in Breast Cancer Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020;2020:3469840. doi: 10.1155/2020/3469840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao X., Li Y., Wang Y., Yu T., Zhu C., Zhang X., Guan J. Curcumin suppresses tumorigenesis by ferroptosis in breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0261370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsvetkov P., Coy S., Petrova B., Dreishpoon M., Verma A., Abdusamad M., Rossen J., Joesch-Cohen L., Humeidi R., Spangler R.D., et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 2022;375:1254–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.abf0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang G., Sun J., Zhang X. A novel Cuproptosis-related LncRNA signature to predict prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:11325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15251-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z., Zeng X., Wu Y., Liu Y., Zhang X., Song Z. Cuproptosis-Related Risk Score Predicts Prognosis and Characterizes the Tumor Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:925618. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.925618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Zhang Y., Wang L., Zhang N., Xu W., Zhou J., Zhao Y., Zhu W., Zhang T., Wang L. Development and experimental verification of a prognosis model for cuproptosis-related subtypes in HCC. Hepatol. Int. 2022;16:1435–1447. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn L.L., Kong S.M.Y., Tumanov S., Chen W., Cantley J., Ayer A., Maghzal G.J., Midwinter R.G., Chan K.H., Ng M.K.C., et al. Hmox1 (Heme Oxygenase-1) Protects Against Ischemia-Mediated Injury via Stabilization of HIF-1α (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021;41:317–330. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H., Chen X., Zhang C., Yang T., Deng Z., Song Y., Huang L., Li F., Li Q., Lin S., et al. EF24 induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells through HMOX1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;136:111202. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q., Deng T., Zhang H., Zuo D., Zhu Q., Bai M., Liu R., Ning T., Zhang L., Yu Z., et al. Adipocyte-Derived Exosomal MTTP Suppresses Ferroptosis and Promotes Chemoresistance in Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2022;9:e2203357. doi: 10.1002/advs.202203357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai W.C., Hsu S.D., Hsu C.S., Lai T.C., Chen S.J., Shen R., Huang Y., Chen H.C., Lee C.H., Tsai T.F., et al. MicroRNA-122 plays a critical role in liver homeostasis and hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2884–2897. doi: 10.1172/jci63455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valashedi M.R., Roushandeh A.M., Tomita K., Kuwahara Y., Pourmohammadi-Bejarpasi Z., Kozani P.S., Sato T., Roudkenar M.H. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of Lcn2 in human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 ameliorates erastin-mediated ferroptosis and increases cisplatin vulnerability. Life Sci. 2022;304:120704. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao F., Deng Y., Zhao Y., Mei Y., Zhang Y., Liu X., Martinez C., Su X., Rosato R.R., Teng H., et al. A targetable LIFR-NF-κB-LCN2 axis controls liver tumorigenesis and vulnerability to ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:7333. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27452-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demerdash H.M., Sabry A.A., Arida O.E. Impact of Zinc to Copper Ratio and Lipocalin 2 in Obese Patients Undergoing Sleeve Gastrectomy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022;2022:9278531. doi: 10.1155/2022/9278531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He Y., Wang R., Zhang P., Yan J., Gong N., Li Y., Dong S. Curcumin inhibits the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells by targeting the chemerin/CMKLR1/LCN2 axis. Aging. 2021;13:13859–13875. doi: 10.18632/aging.202980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan Q., Liu Z.Y., Yang Y.P., Liu S.M. Effect of curcumin on inhibiting atherogenesis by down-regulating lipocalin-2 expression in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Bio. Med. Mater. Eng. 2016;27:577–587. doi: 10.3233/bme-161610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y.H., Liu C.L., Chiu W.C., Twu Y.C., Liao Y.J. HMGCS2 Mediates Ketone Production and Regulates the Proliferation and Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers. 2019;11:1876. doi: 10.3390/cancers11121876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duan J.Y., Lin X., Xu F., Shan S.K., Guo B., Li F.X., Wang Y., Zheng M.H., Xu Q.S., Lei L.M., et al. Ferroptosis and Its Potential Role in Metabolic Diseases: A Curse or Revitalization? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:701788. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.701788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie L., Yuan Y., Xu S., Lu S., Gu J., Wang Y., Wang Y., Zhang X., Chen S., Li J., et al. Downregulation of hepatic ceruloplasmin ameliorates NAFLD via SCO1-AMPK-LKB1 complex. Cell Rep. 2022;41:111498. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eleftheriadis T., Pissas G., Filippidis G., Liakopoulos V., Stefanidis I. Reoxygenation induces reactive oxygen species production and ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021;23:41. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korashy H.M., El-Kadi A.O. The role of redox-sensitive transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1 in the modulation of the Cyp1a1 gene by mercury, lead, and copper. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;44:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marquardt J.U., Gomez-Quiroz L., Arreguin Camacho L.O., Pinna F., Lee Y.H., Kitade M., Domínguez M.P., Castven D., Breuhahn K., Conner E.A., et al. Curcumin effectively inhibits oncogenic NF-κB signaling and restrains stemness features in liver cancer. J. Hepatol. 2015;63:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou C., Hu C., Wang B., Fan S., Jin W. Curcumin Suppresses Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion Through Modulating miR-21-5p/SOX6 Axis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2020. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Jin M., Kong L., Han Y., Zhang S. Gut microbiota enhances the chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to 5-fluorouracil in vivo by increasing curcumin bioavailability. Phytother. Res. PTR. 2021;35:5823–5837. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu R., Mei X., Ye Y., Xue T., Wang J., Sun W., Lin C., Xue R., Zhang J., Xu D. Zn(II)-curcumin solid dispersion impairs hepatocellular carcinoma growth and enhances chemotherapy by modulating gut microbiota-mediated zinc homeostasis. Pharmacol. Res. 2019;150:104454. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mustafa M.G., Petersen J.R., Ju H., Cicalese L., Snyder N., Haidacher S.J., Denner L., Elferink C. Biomarker discovery for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C-infected patients. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP. 2013;12:3640–3652. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo Y., Huang B., Li R., Li J., Tian S., Peng C., Dong W. Low APOA-1 Expression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Is Associated With DNA Methylation and Poor Overall Survival. Front. Genet. 2021;12:760744. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.760744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y., Hao J., Liu X., Wang H., Zeng X., Yang J., Li L., Kuang X., Zhang T. The mechanism of apoliprotein A1 down-regulated by Hepatitis B virus. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:64. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0232-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dillon S.T., Bhasin M.K., Feng X., Koh D.W., Daoud S.S. Quantitative proteomic analysis in HCV-induced HCC reveals sets of proteins with potential significance for racial disparity. J. Transl. Med. 2013;11:239. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Man S., Yao J., Lv P., Liu Y., Yang L., Ma L. Curcumin-enhanced antitumor effects of sorafenib via regulating the metabolism and tumor microenvironment. Food Funct. 2020;11:6422–6432. doi: 10.1039/C9FO01901D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai M.C., Yen Y.H., Chang K.C., Hung C.H., Chen C.H., Lin M.T., Hu T.H. Elevated levels of serum urokinase plasminogen activator predict poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1169. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6397-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connolly B.M., Choi E.Y., Gårdsvoll H., Bey A.L., Currie B.M., Chavakis T., Liu S., Molinolo A., Ploug M., Leppla S.H., et al. Selective abrogation of the uPA-uPAR interaction in vivo reveals a novel role in suppression of fibrin-associated inflammation. Blood. 2010;116:1593–1603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., Smyth G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu T., Hu E., Xu S., Chen M., Guo P., Dai Z., Feng T., Zhou L., Tang W., Zhan L., et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2:100141. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greene C.S., Krishnan A., Wong A.K., Ricciotti E., Zelaya R.A., Himmelstein D.S., Zhang R., Hartmann B.M., Zaslavsky E., Sealfon S.C., et al. Understanding multicellular function and disease with human tissue-specific networks. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:569–576. doi: 10.1038/ng.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langfelder P., Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Z., Zhao Q., Zuo Z.-X., Yuan S.-Q., Yu K., Zhang Q., Zhang X., Sheng H., Ju H.-Q., Cheng H., et al. Systematic Analysis of the Aberrances and Functional Implications of Ferroptosis in Cancer. iScience. 2020;23:101302. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma L., Wang L., Khatib S.A., Chang C.W., Heinrich S., Dominguez D.A., Forgues M., Candia J., Hernandez M.O., Kelly M., et al. Single-cell atlas of tumor cell evolution in response to therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2021;75:1397–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hao Y., Hao S., Andersen-Nissen E., Mauck W.M., 3rd, Zheng S., Butler A., Lee M.J., Wilk A.J., Darby C., Zager M., et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184:3573–3587.e3529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the GEO repository, GSE59713 and GSE151530.