Abstract

The Streptomyces coelicolor fab (fatty acid biosynthesis) gene cluster (fabD-fabH-acpP-fabF) is cotranscribed to produce a leaderless mRNA transcript. One of these genes, fabH, encodes a ketoacyl synthase III that is essential to and is proposed to be responsible for initiation of fatty acid biosynthesis in S. coelicolor.

Streptomyces spp. synthesize the majority of their fatty acids from branched starters such as isobutyryl, isovaleryl, and anteisovaleryl units to give odd- and even-numbered fatty acids with a methyl branch at the ω-terminus (80 to 90% of total fatty acid content); the remainder are synthesized from straight starters such as acetyl and butyryl units (11, 21). The fatty acid synthase (FAS) of Streptomyces spp. is, like that found in many other bacteria (including the best-studied example, that of Escherichia coli), a type II or dissociable system (13, 18). The type II FAS consists of several discrete proteins that form loose associations to synthesize the fatty acid. The assembly of fatty acids is initiated by the condensation of an acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) starter unit and a malonyl-acyl carrier protein (malonyl-ACP) extender unit; this condensation is catalyzed by β-ketoacyl ACP synthase III (FabH), the product of the fabH gene. In vitro biochemical studies suggest that FabH determines the choice of starter unit to be used. E. coli FabH is specific for an acetyl-CoA starter unit, whereas Bacillus subtilis and Streptomyces glaucescens FabHs can accept a broader range of substrates, including branched- and straight-chain units (2, 8). In the case of the S. glaucescens FabH, the order of reactivity towards the different starters is isobutyryl-CoA > butyryl-CoA > acetyl-CoA. If FabH were solely responsible for the initiation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Streptomyces species, then one could hypothesize that its biochemical activity, together with the relative pool sizes of the different starter units in vivo, would account for the mix of branched and straight fatty acids (8). But when S. glaucescens was grown in the presence of high concentrations (480 μM) of the FAS inhibitor thiolactomycin, branched-chain fatty acid biosynthesis was inhibited and the proportion of straight-chain fatty acids increased (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] for purified S. glaucescens FabH 20 μM) (8). This result may be interpreted as evidence for a second; FabH-independent mechanism for fatty acid initiation in Streptomyces spp. Based on this second hypothesis, fabH should be dispensable to Streptomyces spp. In this study we provide further biochemical evidence for the role of a small cluster of presumed fab genes (which includes fabH) in Streptomyces coelicolor and a transcriptional analysis of the fab cluster, and we have attempted to disrupt fabH to determine if it is essential for the viability of the cells.

The acpP gene product stimulates long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis in vitro.

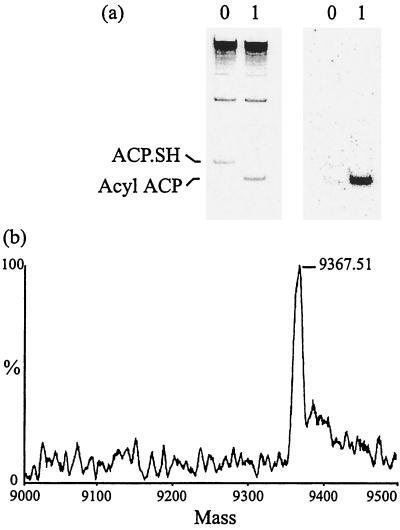

The S. coelicolor FAS is still relatively poorly understood; a cluster of four fab-like genes has been identified on the S. coelicolor chromosome in the order fabD-fabH-acpP-fabF (cosmid SC4A7, S. coelicolor genome project [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor/]; nucleotide sequence accession number AL133423). The deduced amino acid sequences of the fab genes are highly similar to components of the E. coli FAS, and at least some of the S. coelicolor genes are essential (13). We used a biochemical assay of fatty acid biosynthesis, dependent on the acpP gene product (ACP), to strengthen the evidence that these genes do encode the FAS of S. coelicolor. Cell extracts were prepared from S. coelicolor M145 grown for 20 h in YEME medium (12) and broken as previously described (3), with an additional clearing step by ultracentrifugation for 1 h at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was adjusted to 5 mg of protein/ml, a fresh ice-cold 10% (wt/vol) solution of streptomycin sulfate was added slowly while stirring on ice water to a final concentration of 1%; the mixture was then stirred for a further 20 min and centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 × g. Endogenous ACP was removed from the cell extract by fractionation with a 60 to 80% ammonium sulfate cut as previously described (4), and this cut was dialyzed overnight against 1 liter of cell disruption buffer containing 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Pure FAS holo-ACP was prepared as previously described (14) and reduced to the active monomeric form just prior to each assay by incubation at 30°C for 30 min in a solution containing 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, and 10 mM DTT. Typical assay incubation conditions were as follows: 0.5 mg of S. coelicolor (60 to 80% ammonium sulfate cut) per ml, 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.2), 2 mM DTT, 100 mM NADH, 100 mM NADPH, 20 μM ACP, and 100 μM [2-14C]malonyl-CoA (0.02 Bq/pmol) in a total volume of 18 μl were preincubated for 10 min at 30°C; then 2 μl of isobutyryl-CoA was added (20 μM final concentration) to initiate the reaction (alternatively, buffer alone was added as a negative control), and the incubation was continued for a total of 60 min. Assay products were analyzed in two different ways. First, conformationally sensitive polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (CS-PAGE) was used to determine if any acyl-ACP product had been formed in the assay. The small highly acidic ACPs typically migrate faster than other proteins in CS-PAGE (9, 15), and this technique has been used previously to differentiate acyl adducts of the S. coelicolor ACP (14). After incubation in the presence of isobutyryl-CoA, ACP was depleted and a new, faster-migrating band appeared (Fig. 1a, left panel). The phosphorimage of this gel (Fig. 1a, right panel) showed that the new, faster-migrating ACP species was labeled by the extender unit, consistent with a role for this ACP in stimulating at least one round of condensation between the starter and extender units, catalyzed by the FAS components in the cell extract. Second, electrospray mass spectrometry (ESMS) was used to determine the exact mass of the acyl-ACP product identified by CS-PAGE. The assay incubation was run as described above, but it was scaled up 10-fold and cold malonyl-CoA was used. The acyl-ACP species were purified from the assay mixtures (with or without isobutyryl-CoA) using the Biocad Sprint purification system (Perkin-Elmer) with a POROS HQ/M column (4.6 by 100 mm) and eluted in a linear gradient of 0 to 800 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris–bis-Tris propane, pH 7.2, over 15 column volumes (10 ml/min). Unmodified ACP (no isobutyryl-CoA, negative control) was eluted at 509 mM NaCl, and the acyl-ACP reaction product was eluted at 327 mM NaCl. After desalting (PD10; Pharmacia), the ACPs were analyzed by ESMS by John Crosby, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Bristol, England, as described previously (3). ACP purified from the assay mixture that lacked isobutyryl-CoA had a measured mass (mean ± standard deviation) of 9,126.6 ± 2 Da (expected mass, 9,128 Da), and the acyl-ACP (isobutyryl-CoA dependent) had a measured mass of 9,367.5 ± 2.9 Da, in close agreement with that expected for C16 acyl-ACP (9,366 Da) (Fig. 1b). This demonstrated that the acpP gene product is able to stimulate isobutyryl-CoA-dependent long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis in cell extracts of S. coelicolor. These data provide further evidence to substantiate the argument that acpP, and by implication its surrounding genes, does encode the FAS of S. coelicolor.

FIG. 1.

Identification of the acyl-ACP products formed by in vitro FAS assay. (a) Left panel, CS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of material incubated in the assay. Lane 0, no acyl-CoA starter unit added; lane 1, isobutyryl-CoA added as a starter. Right panel, phosphorimage of the gel shown on the left. (b) Transformed electrospray mass spectrum of the repurified acyl-ACP after incubation with the isobutyryl-CoA starter. The major peak, with a molecular mass of 9,367.5 Da (±2.9Da) is in close agreement with the calculated mass of C16 acyl-ACP (9,366 Da).

Transcriptional analysis of the fab genes.

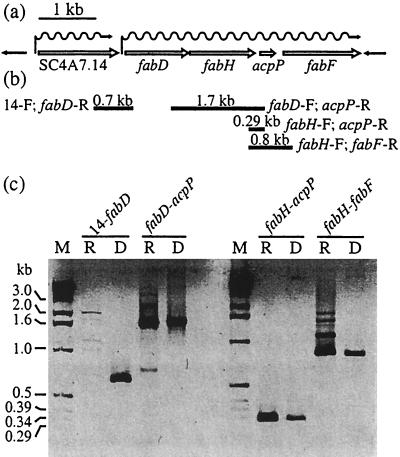

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was used to detect the presence or absence of continuous mRNA spanning the junctions between each of the fab genes and between fabD and SC4A7.14 (the gene on cosmid SC4A7 upstream of and colinear with fabD, named as such in the S. coelicolor genome project) (Fig. 2a). RNA was isolated from cultures of S. coelicolor M145 grown for 20 h in YEME medium as previously described (12) and incubated with DNase (free of RNase; Roche Diagnostics) to remove traces of contaminating DNA. Cotranscription of genes was analyzed by RT-PCR of intergenic regions using the Titan One Tube RT-PCR system (Roche Diagnostics) by following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. The temperature profile was as follows: 1 cycle at 60°C for 30 min, 30 cycles of PCR (denaturation for 1 min at 96°C, annealing for 1 min at 65°C, and extension for 4 min at 72°C), and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 min. The total reaction volume was 50 μl, and 10 μl was analyzed on an agarose gel. Oligonucleotides were as follows (Fig. 2b): SC4A7.14 forward, 5′-AAGTCGCTGATCGGGCCGTTCG-3′; fabD reverse, 5′-CGAGATCGAGTCCGATGGCGTC-3′, fabD forward, 5′-GGCGAACGTGAACGGCGCCGGT-3′; fabH forward, 5′-GGAGCGGCTCCTGGCGACCGGC-3′; acpP reverse, 5′-TGACGTCCTCGACCGGGATGCC-3′; and fabF reverse, 5′-CGATCAGCGCGAACTGCGCCGA-3′. RT-PCR products were generated across the fabD-fabH, fabH-acpP, and acpP-fabF junctions but not across the fabF-SC4A7.19c interval (SC4A7.19c is downstream of and convergent with fabH, and so this served as a negative control) or the SC4A7.14-fabD junction. In all cases, the expected PCR product was generated when genomic DNA served as the template (initial RT incubation omitted), providing a positive control for each PCR (Fig. 2c). Because the fabF-SC4A7.19c-convergent genes gave a PCR product with genomic DNA as a template, but they did not give an RT-PCR product with RNA as a template (data not shown); there was no contaminating DNA in the RNA preparation. Additional controls included the following: no DNA or RNA template (no product seen), RNA template treated with RNase (no product), and DNA template treated with DNase (no product). These results strongly suggest that one long transcript originated from a promoter upstream of fabD and continued through all four fab genes to terminate just 3′ of fabF. The gene upstream of and colinear with fabD, SC4A7.14, has end-to-end similarity with genes found in every prokaryote sequenced so far, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, in which it is also located immediately upstream of fabD, though their functions are unknown. Even though a transcript was not detected between SC4A7.14 and fabD, this does not rule out a role for the SC4A7.14 gene product in fatty acid biosynthesis; it merely indicates that it is not cotranscribed with the fab genes, at least in cells grown to mid-log phase in a rich liquid medium.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR analysis to detect transcriptional readthrough between fab genes. (a) Schematic representation of the fab cluster to show the organization of the genes on the chromosome (gene names are as in the S. coelicolor genome project). (b) Positions of oligonucleotides used in RT-PCR experiments and expected RT-PCR products. (c) Agarose gel of RT-PCR products showing no transcriptional readthrough between SC4A7.14 and fabD, whereas fabD and fabH, fabH and acpP, and acpP and fabF are cotranscribed. M, DNA molecular size markers; R, RNA template; D, DNA template.

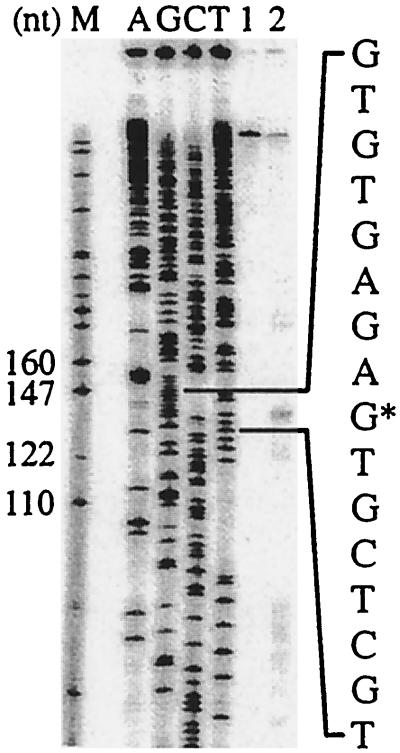

High-resolution S1 nuclease protection analysis was used to locate the 5′ end of the long fab transcript. A SmaI-to-StyI DNA fragment (883 nucleotides [nt], negative strand) encompassing the start of fabD was prepared with a γ-32P label on the 5′ end of the minus strand (140 nt downstream of the fabD translational start site) and hybridized with RNA as previously described (12). A single 5′ end was identified which coincides with the GUG translational start point for fabD (Fig. 3) when run alongside a sequence ladder generated from the oligonucleotide 5′-CTTGGTGCCGAAGTGGGCGAGA-3′ (140 nt downstream of the fabD translational start site). This means that the fab operon is transcribed in the absence of an mRNA leader sequence, an unusual situation in bacteria but not uncommon in Streptomyces (10, 17). To confirm that this was the true transcriptional initiation point, we used an in vitro transcription assay comprising purified S. coelicolor holo-RNA polymerase, dinucleotide primers, and the same restriction fragment encompassing the promoter region of fabD as that used for S1 nuclease protection (12). A 140-nt runoff transcript was generated corresponding to that expected from initiation at the first nucleotide of the GUG translational start codon (data not shown). The translational start point had previously been determined from N-terminal sequence analysis of the purified protein (13). Interactions between the 3′ end of the bacterial 16S rRNA and sequences downstream of the start codon must initiate translation of mRNA sequences that lack a leader. A putative downstream box was identified within fabD (nt +13 to +24) that aligns well with consensus Streptomyces downstream box sequences (10, 17) and with a complementary sequence near the 3′ end of S. coelicolor 16S rRNA. Downstream-box-like sequences have also been found within acpP and fabF but not in fabH; the start codon of fabH overlaps the stop codon of fabD such that fabD and fabH could potentially be cotranslated, and so one may not necessarily expect to find a ribosome binding site. To our knowledge, this is the first example of this phenomenon for a primary metabolic gene in Streptomyces.

FIG. 3.

High-resolution mapping of fabD promoter. A protected fragment (139 nt) of the fabD promoter probe (lane 2) comigrating with the GUG translational start point is indicated on the corresponding sequence ladder (lanes A to T). Lane 1, tRNA instead of mRNA mixed with the fabD promoter probe (negative control).

With these results we were able to design a strategy for the disruption of fabH such that there would be no unwanted polar effects on the transcription of the surrounding genes.

S. coelicolor fabH (encoding FabH) is essential for viability.

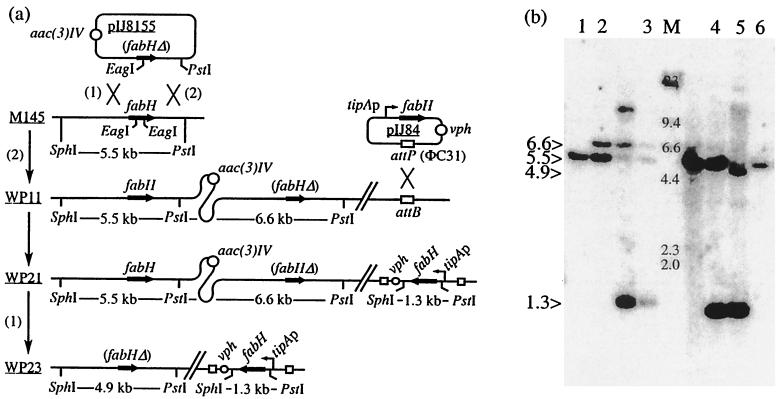

So far, four homologues of fabH have been found in the S. coelicolor genome (with 90% of the genome complete), and each has an amino acid sequence approximately 40% identical to the fabH product (S. coelicolor genome project). The roles of two of these open reading frames are unknown, but one possibility is that they might encode alternative FabHs for fatty acid initiation. pIJ8155 (Table 1) was introduced into S. coelicolor by conjugation from E. coli (as described in reference 6); apramycin-resistant colonies were picked, and putative single-crossover recombinants were confirmed by Southern hybridization. Eleven out of 12 of the colonies showed integration of the plasmid by homologous recombination through the sequence to the left of the deletion in fabH (event 1) (Fig. 4a), and 1 (S. coelicolor WP11) out of 12 showed integration by homologous recombination through the right-hand sequence (event 2) (Fig. 4a and b, lane 2). Neither event was expected to disrupt transcription of the fab operon. WP11 was chosen as a parent from which to attempt to isolate a fabH disruptant because its low frequency of occurrence suggested that the recombination event leading to the deletion of fabH would be favored. Twenty-four apramycin-sensitive segregants were isolated among 21,553 colonies screened after three rounds of growth in the absence of apramycin. All had reverted to wild type via a reversal of the first crossover (event 2); as shown by Southern hybridization (Fig. 4b, lane 6); none had undergone the second crossover event to delete the fabH gene.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | ||

| M145 | Prototrophic SCP1-SCP2 (wild type) | 12 |

| WP11 | M145/pIJ8155 | This work |

| WP21 | WP11/pIJ84 (2nd copy of fabH) | This work |

| WP23 | ΔfabH (fab cluster) derivative of WP21 | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | General host for cloning | 16 |

| ET12567/pUZ8002 | For conjugation with Streptomyces | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC118 | General cloning vector | 20 |

| pOJ260 | Suicide vector for Streptomyces containing oriT RK2 for conjugation from E. coli to Streptomyces | 1 |

| pIJ8600 | Integrating vector for inducible expression of genes cloned under control of the tipAp promoter | 19 |

| pIJ8155 | Derivative of pOJ260 containing 3.1 kb of S. coelicolor fab DNA (BglII to PstI) spanning a 650-bp in-frame deletion in fabH (EagI-EagI); used for deletion of fabH | This work |

| pIJ84 | Derivative of pIJ8600, with a SacI-to-SalI fragment encompassing fabH cloned (with BglII linkers) under control of the tipAf promoter and with vph (for viomycin resistance) cloned in place of aacC(IV) (for apramycin resistance); used to complement the deletion of fabH | This work |

FIG. 4.

Disruption of fabH by double crossover. (a) Schematic representation of the disruption events. (b) Southern hybridization analysis of the recombinant strains at each stage of the disruption. Genomic DNA from each strain was digested with SphI and PstI. The hybridization probe was radiolabeled fabH. Lane M, λ-HindIII molecular size standards (sizes are indicated in kilobases); lane 1, M145 (parental strain); lane 2, WP11 (integration of pIJ8155 through event 2); lane 3, WP21 (same as WP11 but with a second copy of fabH integrated at the ΦC31 att site on pIJ84); lane 4, WP22 (pIJ8155 excised through a reversal of the original integration event); lane 5, WP23 (pIJ8155 excised through event 1 leaving the disrupted copy of fabH in the fab cluster); lane 6, apramycin-sensitive revertant of WP11 (as M145). Note that irrelevant lanes are unidentified.

The likely interpretation of this result is that fabH is essential. To address this issue further, a second copy of fabH was introduced into strain WP11 on pIJ84 such that it would be expressed under the control of the thiostrepton-inducible promoter tipAp. The resulting strain, WP21, was confirmed by Southern hybridization to contain the second copy of fabH integrated at the ΦC31 att site (Fig. 4b, lane 3). WP21 was propagated through one round of growth and sporulation on a medium containing thiostrepton at 2.5 μg/ml but lacking apramycin. Southern hybridization showed that of 16 apramycin-sensitive segregants isolated, 10 had reverted to wild type (for an example, see Fig. 4b, lane 4) and the other 6 had undergone the second crossover (event 1) to create an in-frame deletion in fabH from the fab gene cluster; one segregant of the latter type was named WP23 (Fig. 4b, lane 5). This demonstrated that fabH can readily be deleted from the chromosome to yield a viable strain, but only if a second copy of fabH is available to complement the deletion. In parallel, apramycin-sensitive segregants from WP21 grown in the absence of thiostrepton (for induction of tipAp) were also sought. One out of seven apramycin-sensitive colonies was confirmed by Southern analysis to have undergone deletion of fabH, reflecting the known low level of tipAp promoter activity even in the absence of the thiostrepton inducer.

It appears that fabH can be deleted without causing lethality only when a second fabH copy is expressed in the same cells, implying that fabH is involved in an essential primary metabolic process, most likely fatty acid biosynthesis. This result does not rule out alternative mechanisms for initiation of fatty acid biosynthesis in S. coelicolor (e.g., any of the homologues of FabH that have been identified as part of the S. coelicolor genome project; a separate acetyl-CoA:ACP acyltransferase might bypass the action of FabH, as is the case in plant FASs [7]; decarboxylation of malonyl-ACP might provide an acetyl starter unit for straight-chain fatty acid biosynthesis, and a second FAS might also exist [5]). It merely shows that, if they exist, their activities are insufficient to suppress the effect of a deletion of fabH. The physiological target of thiolactomycin in Streptomyces remains an enigma, but these results suggest that alternative components of the FAS may be targets for thiolactomycin (e.g., FabF, the condensing enzyme thought to be responsible for elongation of fatty acids) and that these too might have some influence on the ratio of branched- to straight-chain fatty acids.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mervyn Bibb for the gift of S. coelicolor holo-RNA polymerase; John Crosby for ESMS analysis of the ACPs; and Tobias Kieser, Keith Chater, and Mark Buttner for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by BBSRC, the John Innes Foundation, and grant B102-CT94-2067 from the European Community.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno E T, Rao R N, Schoner B E. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi K-H, Heath R J, Rock C O. β-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) is a determining factor in branched-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:365–370. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.365-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby J, Sherman D H, Bibb M J, Revill W P, Hopwood D A, Simpson T J. Polyketide synthase acyl carrier proteins from Streptomyces: expression in Escherichia coli, purification and partial characterisation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1251:32–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00053-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Englard S, Seifter S. Precipitation techniques. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:285–300. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82024-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flatman S, Packter N M. Partial purification of fatty acid synthase from Streptomyces coelicolor. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983;11:597. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flett F, Mersinias V, Smith C P. High efficiency intergeneric conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to methyl DNA-restricting streptomycetes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;155:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb13882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulliver B S, Slabas A R. Acetoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase from avocado: its purification, characterization and clear resolution from acetyl CoA:ACP transacylase. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00023236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han L, Lobo S, Reynolds K A. Characterization of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III from Streptomyces glaucescens and its role in initiation of fatty acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4481–4486. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4481-4486.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath R J, Rock C O. Enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (fabI) plays a determinant role in completing cycles of fatty acid elongation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26538–26542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen G R. Eubacterial, archaebacterial, and eucaryotic genes that encode leaderless mRNA. In: Baltz R H, Hegeman G D, Skatrud P L, editors. Industrial microorganisms: basic and applied molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaneda T. Iso- and anteiso-fatty acids in bacteria: biosynthesis, function, and taxonomic significance. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:288–302. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.2.288-302.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J, Chater K F, Hopwood D A. Practical Streptomyces genetics. John Innes Foundation. Norwich, England: John Innes Centre; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revill W P, Bibb M J, Hopwood D A. Purification of a malonyltransferase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and analysis of its genetic determinant. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3946–3952. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3946-3952.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revill W P, Bibb M J, Hopwood D A. Relationships between fatty acid and polyketide synthases from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): characterization of the fatty acid synthase acyl carrier protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5660–5667. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5660-5667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rock C O, Cronan J E, Jr, Armitage I M. Molecular properties of acyl carrier protein derivatives. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:2669–2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch F E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strohl W R. Compilation and analysis of DNA sequences associated with apparent streptomycete promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:961–974. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Summers R G, Ali A, Shen B, Wessel W A, Hutchinson C R. Malonyl-coenzyme A:acyl carrier protein acyltransferase of Streptomyces glaucescens: a possible link between fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9389–9402. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun J, Kelemen G H, Fernandez-Abalos J M, Bibb M J. Green fluorescent protein as a reporter for spatial and temporal gene expression in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbiology. 1999;145:2221–2227. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vieira J, Messing J. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;153:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace K K, Zhao B, McArthur H A, Reynolds K A. In vivo analysis of straight-chain and branched-chain fatty acid biosynthesis in three actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]