Abstract

The siderophore transport activities of the two outer membrane proteins FhuA and FecA of Escherichia coli require the proton motive force of the cytoplasmic membrane. The energy of the proton motive force is postulated to be transduced to the transport proteins by a protein complex that consists of the TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins. In the present study, TonB fragments lacking the cytoplasmic membrane anchor were exported to the periplasm by fusing them to the cleavable signal sequence of FecA. Overexpressed TonB(33-239), TonB(103-239), and TonB(122-239) fragments inhibited transport of ferrichrome by FhuA and of ferric citrate by FecA, transcriptional induction of the fecABCDE transport genes by FecA, infection by phage φ80, and killing of cells by colicin M via FhuA. Transport of ferrichrome by FhuAΔ5-160 was also inhibited by TonB(33-239), although FhuAΔ5-160 lacks the TonB box which is involved in TonB binding. The results show that TonB fragments as small as the last 118 amino acids of the protein interfere with the function of wild-type TonB, presumably by competing for binding sites at the transporters or by forming mixed dimers with TonB that are nonfunctional. In addition, the interactions that are inhibited by the TonB fragments must include more than the TonB box, since transport through corkless FhuA was also inhibited. Since the periplasmic TonB fragments cannot assume an energized conformation, these in vivo studies also agree with previous cross-linking and in vitro results, suggesting that neither recognition nor binding to loaded siderophore receptors is the energy-requiring step in the TonB-receptor interactions.

The TonB protein is hypothesized to transduce energy from the inner membrane of gram-negative bacteria, to which it is anchored, to outer membrane siderophore transporters, such as FhuA, FecA, and FepA in Escherichia coli. This allows transport of the siderophores, which have bound to high-affinity binding sites of the transporters, to the periplasmic side of the membrane for transport across the inner membrane. A carboxyl-terminal fragment of TonB was recently crystallized and shown to be a dimer (10). The protein is thought to be able to recognize loaded transporters, and a mechanism for this was suggested by the crystal structures of FhuA and FepA. The TonB box of FepA (residues 12 to 18) is located inside the barrel and is exposed to the periplasm (9). In the FhuA crystal, the TonB box (residues 7 to 11), in which mutations could be suppressed by mutations in TonB (42), is not ordered, but Trp-22 is exposed to the periplasm and alters its position by 17 Å when FhuA is loaded with ferrichrome (14, 31). Genetic and biochemical studies with isolated FhuA and with FhuA in living cells indicate the functional relevance of the structural transition. Upon binding of ferrichrome, detergent-solubilized FhuA undergoes a TonB-independent structural transition that reduces the binding efficiency of monoclonal antibodies that recognize residues 21 to 59 (38) and decreases the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of FhuA (32). In vivo, ferrichrome binding causes fluorescence quenching of fluorescein-maleimide bound to the genetically introduced Cys-336 residue (3) and enhances the formation of a chemically cross-linked complex between FhuA and TonB (37).

Functional evidence for a substrate-induced change in the conformation of an outer membrane transporter was also obtained in studies of the ferric citrate transport system of E. coli (18). Transport of ferric citrate across the outer membrane is mediated by FecA and is TonB dependent. The FecA transporter, when loaded with ferric citrate, also induces transcription of the ferric citrate transport genes. In addition to the TonB box, FecA contains an N-terminal extension compared to the other outer membrane transporters of E. coli K-12 (6, 25). This extension mediates transcription initiation by binding to the FecR anti-sigma factor protein in the cytoplasmic membrane, which transmits the signal to the FecI sigma factor in the cytoplasm (13). Transcription initiation is TonB dependent and can occur without ferric citrate transport (18).

A number of studies have also addressed the role of the transmembrane domain of TonB and the proton motive force in the interactions between TonB and the outer membrane receptors. Subcellular fractionation experiments showed binding of TonB to both the outer membrane and the cytoplasmic membrane (30). In mutants devoid of ExbB and ExbD, TonB was localized to the outer membrane. However, dissipation of the proton motive force which is required for TonB activity (4) did not alter the distribution of TonB between the outer membrane and the cytoplasmic membrane (30), suggesting that energization does not enhance association of TonB with the transporters. This conclusion is also supported by cross-linking studies and in vitro experiments which demonstrated specific TonB-receptor interactions in the absence of a proton motive force (21, 36, 37). Replacement of the transmembrane segment of TonB by transmembrane domains of penicillin-binding protein 3 (23) or the TetA tetracycline exporter (21) resulted in inactive proteins. In addition, the TetA-TonB fusion was shown to be localized to the outer membrane and formed all of the cross-links that native TonB did (21, 30). Replacement of the TonB transmembrane domain with the OmpA signal sequence resulted in a fusion protein which was partially processed and secreted but was inactive in phage sensitivity assays (23). Modification of TonB to create a signal peptidase cleavage site without altering the sequence of the transmembrane domain also resulted in a fusion that was inactive when processed (21). In the latter study it was shown that the TonB derivative with a cleavable signal sequence displayed dominant-negative interference of the activity of wild-type TonB. However, it was not certain what caused the interference, since both the cleaved signal sequence and the periplasmic TonB fragment would have been capable of interference via interactions with other components such as the ExbB protein and the siderophore receptors. Taken together, these data suggest that energized and unenergized TonB associates physically with the outer membrane but that functional interaction with the transporters may require energization of TonB and substrate loading of the transporters. In addition, although it is now clear that the TonB box of the various receptors and the Q160 region of TonB physically interact (11), little is known about the specific residues that are involved in TonB-receptor interactions that allow ligand transport through the receptors.

In this study we have employed periplasmic fragments of TonB to determine whether they interfere with TonB-dependent outer membrane functions. These fragments did not contain the cytoplasmic membrane anchor and therefore could not respond to the proton motive force. They were thus also missing a major (but not necessarily the only) region of interaction between TonB and ExbB within the cytoplasmic membrane (21, 28, 46). The functional assays performed were those involving the FhuA and FecA transporters. FhuA is a multifunctional protein that is involved in infection by bacteriophages, the uptake of colicins, and the transport of certain antibiotics in addition to ferrichrome transport. Also of interest was the ability of the TonB fragments to affect activity of FhuAΔ5-160, a deletion derivative of the FhuA outer membrane transporter that lacks the globular cork which closes the channel of the FhuA β-barrel. This derivative still displays all FhuA activities, including the TonB-dependent functions, except transport of microcin J25 (8). Therefore, periplasmic TonB fragments might indicate those regions of TonB that are required for the interaction with the TonB box, as well as those that interact with other regions of FhuA. FecA was also chosen as a transporter for these studies because FecA mutants have been isolated which still initiate transcription of the fecABCDE transport genes but no longer transport ferric citrate. It was possible that specific periplasmic TonB fragments might interfere with signaling but not with transport and vice versa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The media used were tryptone-yeast extract (YT) (35) and nutrient broth (NB) (Difco), and incubation was at 37°C for all experiments. Ampicillin and neomycin were used at a concentration of 50 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol was used at a concentration of 10 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains of E. coli K-12 and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| AB2847 | aroB tsx malT thi | 17 |

| HK97 | MC4100 aroB fhuA412 fhuE::λplacMu53 | 24 |

| DH5α | Δ(argF lac)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi1 gyrA1 relA1 (F′ φ80 lacZΔM15) | 16 |

| BL21(DE3) | hsdS ompT; phage T7 RNA polymerase gene | 43 |

| ZI418 | araD139 Δ(argF lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR thi aroB fecB::Mud1(Ap, lac) | 47 |

| GM1 | ara thi Δlac pro F′(lac pro) | 44 |

| TPS13 | GM1 tolQ(R) | 44 |

| HE12 | TPS13 tonB | 7 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMALp2 | ColE1 ori, malE, Apr | J. Höltje |

| pMALc2G | ColE1 ori, malE, Apr | Gibco-BRL |

| pET30a | ori ColE1, T7 promoter, Kmr | Novagen |

| pTon137SH | ′tonB fusion in pET30a | This study |

| pCSTon30 | ′tonB fusion in pET30a | This study |

| pMFT | fecA′ ′tonB fusion in pMALc2G | This study |

| pMFTC | pMFT with cat inserted | This study |

| pMFT137 | fecA′ ′tonB fusion in pMALc2G | This study |

| pMFTLP | fecA′ ′tonB fusion in pMALc2G | This study |

| pSU767 | fhuA in pSU18 | 8 |

| pSUBK17 | fhuAΔ5-160 in pSU18 | 8 |

| pCG754 | pT7-5 containing tonB exbB exbD | 15 |

| pSUSK | ori pSC101, Cmr, 0.65-kb HaeII, fragment of pBCKS+ in pSU19 | R. Schönherr |

| pCH9 | ori ColE1, Apr, containing exbB exbD 1.6-kb XhoI/EcoRI fragment | This study |

| pSKBD | exbB exbD fragment of pCH9 in pSUSK | This study |

| pColE1 | K. Hantke | |

| pTU3 | cma and cmi in pUC19 | 39 |

Construction of plasmids encoding TonB fusion proteins.

All constructions involving cloning of PCR products included the preliminary cloning of the product into an intermediate vector. The oligodeoxynucleotides used are listed in Table 2. The plasmid pCSTon30 contains the tonB gene fragment encoding residues 33 to 239 of the periplasmic domain of TonB amplified from strain W3110 and cloned into the BamHI site of pET30a (Novagen). This fused the tonB fragment to an amino-terminal domain provided by pET30a consisting of 50 amino acids encoding six histidines and a number of protease cleavage sites. Standard PCR conditions and the oligonucleotides UR90 and UR91 (Table 2) were used for this construct. The insert pCSTon30 was sequenced and found to contain no mutations (41). Another recombinant (pTon137SH), encoding a smaller TonB periplasmic fragment encompassing residues 103 to 239 fused to a Met and six His residues, was constructed by performing PCR on pCSTon30 by using oligonucleotides HisT137 and HindTonB. The NdeI-HindIII-digested product was cloned into pCSTon30 digested with the same enzymes. The EcoRV-NotI fragment of pCSTon30 was then cloned into the vector pFecAN2.5, which contains a fecA gene fragment encoding the first 34 amino acids of the protein, followed by a 15-bp linker containing the recognition sites for PstI, SacI, and EcoRV (Uwe Stroeher, unpublished data) in the vector pGEMT (Promega). This intermediate construction (pFSST) was then used in a further PCR with the oligonucleotides FsstATG and HindTonB, producing a product containing the fecA-tonB fusion gene. The fragment was digested with NdeI and HindIII and cloned into the vector pMALc2G (New England Biolabs), producing pMFT. pMFTC was constructed by amplifying the cat gene of pBCSKII+ (Stratagene) by using the oligonucleotides Cam01 and Cam02, digestion of the product with HindIII, and ligation into HindIII-digested pMFT. The plasmid pMFT137 was constructed by using PCR and the oligonucleotides T137BP and HindTonB with pMFT as the template and then cloning the product into pMFT digested with BamHI and HindIII. pMFTLP was constructed in a similar manner, by using PCR and oligonucleotides LPP and HindTonB and cloning the product into pMFT digested with PstI and HindIII. DNA sequence analysis of the inserts of pMFT, pMFT137, and pMFTLP demonstrated that no mutations had been introduced. The sequences of these plasmids are available upon request.

TABLE 2.

Oligodeoxynucleotides used in this study

| Oligodeoxy- nucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| UR90 | 5′-TACCGGATCCCATCAGGTTATTGAACTACC |

| UR91 | 5′-ACCTGGATCCTTACCTGTTGAGTAATAG |

| HisT137 | 5′-GCCGCATATGCACCATCATCATCATCATGTGAAAAAGGTACAGGAG |

| FsstATG | 5′-GGAACATATGACGCCGTTACGCGTTTTTC |

| HinDTonB | 5′-GAATTCAAGCTTTTACCTGTTGAGTAATAGTCA |

| Cam01 | 5′-TGTCAAGCTTTTCAGGAGCTAAGGAAGC |

| Cam02 | 5′-CCAGAAGCTTAAGGGCACCAATAACTGCC |

| T137BP | 5′-GGATCCGTGAAAAAGGTACAGGAGCAG |

| LPP | 5′-GCTGCAGCATCACCGTTTGAAAATACG |

Protein purification.

Transformants of E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pCSTon30 or pTon137SH were grown in YT and, at an optical density at 578 nm of 0.7 to 0.8, were induced by the addition of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) to a final concentration of 0.4 mM and incubated for a further 2 h. The cultures were harvested and resuspended at 1/20 of the original volume of buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9; 500 mM NaCl; 5 mM imidazole). After the addition of protease inhibitors (Complete-EDTA; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), used at the recommended dilution, and DNase I (10 μg/ml) and RNase III (20 μg/ml), the cells were ruptured by two passes through a French pressure cell at a pressure of 16,000 lb/in2. After centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min to remove unbroken cells and cell debris, the supernatant was applied in 5-ml aliquots to a nickel-NTA column (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) washed with buffer A. The H6′TonB (from pCSTon30) and H6′TonB137 (from pTon137SH) proteins were eluted with a gradient of 5 to 250 mM imidazole in buffer A. Peak fractions of the proteins were desalted on a Sephadex G25 column equilibrated with 50 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.0]–1 mM EDTA and applied to either MonoS (H6′TonB) or ResourceS (H6′TonB137) columns (Pharmacia) equilibrated in the same buffer. The proteins were then eluted with a 0.0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient in this buffer and used to raise polyclonal rabbit antisera.

Localization of TonB fragments and quantitation of relative expression levels.

Cells expressing the various TonB fragments were grown in YT medium containing 0.1 mM IPTG and harvested at an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm. Then, 1.5-ml portions of the cultures were osmotically shocked by plasmolysing the cells with a buffer containing 20% sucrose, followed by sudden dilution into ice-cold water, as previously described (48), except that a general protease inhibitor cocktail (P2714; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) was added to the solutions used. The shocked cell pellets were resuspended directly in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer, while the shock fluids were precipitated by the addition of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to a final concentration of 5%. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with 90% acetone in water, and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

A CF4400 ChemiImager (Kodak) was used to quantitate the relative expression level of the periplasmic TonB fragments. Samples were taken from cultures grown in YT to an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm, mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, electrophoresed, and then immunoblotted with the H6′TonB137 antiserum. The chemiluminescent signals from the blots (containing samples from each of the cultures on the same membrane) were then quantitated in arbitrary units and compared. Twofold dilution series of the various preparations analyzed in this manner showed that quantitation by this method yielded values within ±5% of the expected values.

Assay of bacteriophage and colicin M susceptibility.

Susceptibility to bacteriophage φ80 was measured by dropping 5-μl aliquots of 10-fold dilutions of the phage onto freshly poured overlays (ca. 108 cells in 3 ml of YT soft agar overlaid on YT plates) of the various strains. When the effect of IPTG induction level on the susceptibility of the cells was being assayed, the lawns were poured onto plates which contained the indicated concentration of IPTG and were made with cells which had been grown in the presence of the same IPTG concentration. The susceptibility was scored as the −log of the greatest dilution which resulted in complete clearing of the lawn. Colicin susceptibility tests were conducted in a similar manner, except that crude extracts of the colicins, from strains DH5α(pTU3) (39) for colicin M and DH5α(pColE1) for colicin E, were used and the dilutions were made in phosphate-buffered saline, which also contained 0.1% Triton X-100 for colicin M.

Assay of siderophore-dependent growth and iron transport.

The ability of strains to obtain iron from either ferrichrome or ferric citrate was assayed on NB agar plates made limiting for iron by the addition of 250 μM dipyridyl. Paper disks (6 mm) were impregnated with 10 μl of 1 mM ferrichrome or 10 or 100 mM sodium citrate and placed on lawns containing ca. 108 bacteria in 3 ml of NB soft agar. When the effect of induction level was being measured, various concentrations of IPTG as indicated were added to the media. After overnight incubation of the plates at 37°C, the diameter of the growth zones surrounding the disks were recorded. Quantitative assays of siderophore transport employed [55Fe3+]ferrichrome and [55Fe3+]ferric citrate and were performed as previously described (8, 25). In each case, the assays were performed with strains which had been freshly transformed with the required plasmids.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE was performed using 10 or 12% acrylamide gels prepared as described by Laemmli (26), and the proteins were transferred to membranes and incubated in solutions of primary and secondary antibody as previously described (45) except that polyvinyidene difluoride membranes were used and the solutions contained skim milk powder as the blocking agent. Polyclonal antisera, obtained by immunizing rabbits with the purified H6′TonB and H6′TonB137 proteins, were first adsorbed with an acetone powder of the tonB strain BR158 and then used as the primary antibody at dilutions ranging from 1/2,000 to 1/10,000. The secondary antibody was an anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G preparation conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), used at a dilution of 1/10,000. The immunoblots were developed for periods of time ranging from 10 s to 3 min using the Luminol system (Boehringer).

Assay of induction of the fec operon by citrate.

The induction of the fec operon by citrate in the growth medium was assayed in strain ZI418 (47) transformed with pMFTC. Cultures were inoculated at 1% from an overnight culture, with or without 1 mM IPTG and, after 1.5 h of incubation at 37°C, various concentrations of sodium citrate were added. At hourly intervals, the optical density was recorded and 100-μl aliquots of the cultures were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as previously described (36).

RESULTS

Expression of periplasmic TonB fragments as exported proteins.

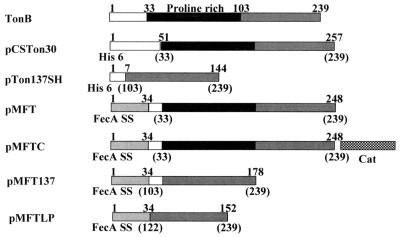

To obtain plasmids which express TonB fragments which would be exported to the periplasm in vivo, a PCR fragment encoding His-33 to Gln-239 was ligated to a segment of the fecA gene, encoding its 34-amino-acid signal sequence, creating a fusion gene encoding FecA(1-34) linked via the peptide Glu-Leu-Asn-Asp-Ile-Gly-Ser to TonB(33-239) (Fig. 1). The fusion gene was then cloned behind the lac promoter of the vector pMALc2G (pMFT, Fig. 1). A similar plasmid (pMFTC) was constructed by inserting a cat gene that encodes chloramphenicol acetyltransferase into pMFT so that it could be maintained in cells of the ampicillin-resistant E. coli ZI418 for studies of induction of the fec operon by citrate (see below). Two shorter constructs, TonB(103-239) (pMFT137) and TonB(122-239) (pMFTLP), were made; in the latter the TonB fragment was directly fused tho the FecA signal sequence (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagrams of the structures of TonB and the fusion proteins expressed by the various fusion genes constructed are shown. The numbers at the top of the diagrams refer to the amino acids of the fusion proteins, while the numbers in brackets refer to the TonB amino acids contained in the fusion. The shaded regions represent domains shared among the fusions.

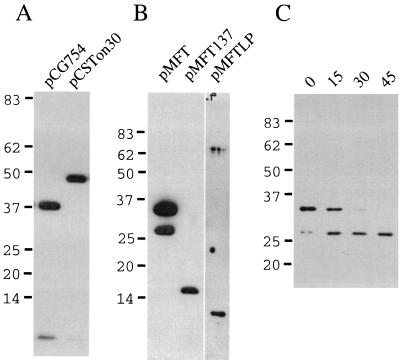

The expression of periplasmic domains of TonB from pMFT, pMFT137, and pMFTLP was monitored by immunoblotting with antiserum obtained by using purified H6′TonB, a soluble fusion protein containing the last 207 amino acids of TonB fused to an amino-terminal histidine tag (see Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods). As controls for the specificity of the immunoblots, cells containing the expression vector pCG754, which overexpresses TonB (15), and cells expressing H6′TonB were also immunoblotted. As shown in Fig. 2, the antisera recognized the 46-kDa (the apparent molecular mass) protein we had purified from cells containing pCSTon30, which encodes H6′TonB. The 46-kDa value is too large, as is the 38-kDa value for native TonB overexpressed by the cells containing pCG754 (calculated mass, 26 kDa) (29). Two bands of 35 and 27 kDa were synthesized by transformants of pMFT (Fig. 2) of which the 35-kDa protein is larger than the calculated molecular mass of the biosynthetic precursor protein (27 kDa). Since this clone synthesizes a fusion protein which contains the proline-rich region of TonB, which causes aberrant, slower migration of the protein on SDS-PAGE gels (29), it is quite likely that the higher-molecular-mass band observed on the gel in Fig. 2 represents the mature protein expressed by pMFT after cleavage of the FecA signal sequence. The 27-kDa protein was likely caused by proteolytic digestion of the mature protein or by translation commencing at an internal codon of the fusion protein mRNA. To determine which of these was the case, protein synthesis was inhibited by addition of chloramphenicol 1 h after induction of an AB2847(pMFT) culture, and the fate of the two major protein bands was monitored by taking samples for the following 45 min and immunoblotting them with the anti-TonB antiserum. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the 35-kDa protein band decreased in quantity, whereas the 27-kDa band increased in quantity, indicating a precursor-product relationship between the two forms of the protein. The process was too slow for the conversion of the biosynthetic precursor form into a mature form, the size difference was too large (8 kDa) for the removal of the signal sequence and, in Fig. 3, the likely precursor form can be seen in the cell fraction (labeled C) but not in the periplasmic fraction (labeled S). Transformants of pMFT137 and pMFTLP produced single proteins with apparent molecular masses of 16 and ca. 12 kDa, respectively. For cells expressing pMFT and pMFT137, overdeveloped blots of the proteins showed the presence of small amounts of an additional protein band running with a slightly higher apparent molecular mass, which may represent unprocessed precursor of the fusion proteins (Fig. 3). The fusion gene of the pMFT137 would produce a precursor protein with a calculated molecular mass of 19 kDa, which after cleavage of the FecA signal sequence would have a molecular mass of 15 kDa, while pMFTLP would be expected to produce a precursor protein of 16 kDa and a mature protein of 12 kDa. The observed size of the proteins produced by pMFT137 and pMFTLP thus matched closely with the expected molecular masses after cleavage of the FecA signal sequence. These results demonstrate that each of the three clones express a protein which reacts with the anti-TonB antiserum and is most likely the processed form of the periplasmic TonB fragment encoded by the respective fusion gene. In addition, it appears that the largest of the periplasmic fragments, containing the entire periplasmic domain of TonB, is subject to partial proteolytic degradation, as is also observed for the intact protein (28).

FIG. 2.

Expression of the periplasmic domains of TonB as secretory proteins. BL21(DE3) (A) or AB2847 (B) cells containing the indicated plasmids were grown in media containing 0.1 mM IPTG, and culture samples were solubilized with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The samples were electrophoresed and then immunobloted with anti-H6TonB antiserum. (C) AB2847(pMFT) cells were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG and, after 1 h of further incubation, 20 μg of chloramphenicol/ml was added, and samples of the culture taken 0, 15, 30, and 45 min later as indicated. The samples were electrophoresed and immunoblotted with the anti-H6TonB antiserum.

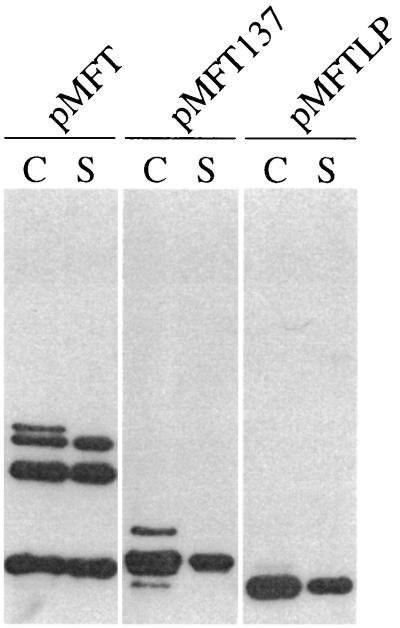

FIG. 3.

Localization of TonB fragments. AB2847 cells containing the indicated plasmids were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG, and culture samples were osmotically shocked. Shocked cells (C) were resuspended in 1/5 the original culture volume, and shock fluids (S) were resuspended in 1/25 the original culture volume before equal volumes (5 μl) were loaded on the SDS-PAGE gel used for the immunoblot.

The appearance on overexposed blots of small amounts of slightly higher apparent molecular mass forms suggested that the FecA signal sequence mediated the translocation of the fusion proteins across the inner membrane and into the periplasm. To confirm this, AB2847 cells expressing the fusion proteins were osmotically shocked to release their periplasmic contents (48). Comparison of immunoblots of the proteins present in extracts prepared before and after the osmotic shock procedures indicated that the majority of each of the proteins was degraded during the shock procedure (data not shown), and for the TonB(33-239) fragment in particular, the procedure resulted in the appearance of large amounts of a much smaller degradion product (Fig. 3), even though the procedure was performed with protease inhibitors and the samples were TCA precipitated as soon as they were obtained. As shown in Fig. 3, for each protein the major band(s) that had been observed in the whole-cell samples could be observed in both the shock fluids and the shocked cells, whereas the slightly higher molecular mass bands, which may represent the precursors of the proteins, were found only in the shocked cells.

An estimate of the comparative expression level of the periplasmic TonB fragments was determined by using chemiluminescent blots of whole-cell samples of the strains expressing the proteins when induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. So that the polyclonal antibodies would predominantly recognize epitopes present in all three of the variously sized periplasmic fragments, the antiserum raised against H6′TonB137, a TonB fusion protein containing only the last 137 amino acids of TonB was used in these blots (see Materials and Methods). Quantification of the signals emitted on these blots indicated that the TonB(33-239) fragment produced by pMFT, plus its degradation fragment, and the TonB(122-239) fragment encoded by pMFTLP were both expressed at a level of 90% of that of the TonB(103-239) fragment. Thus, although both the degradation state as well as the conformation of the proteins on the blot membranes could affect the accuracy of this analysis, the results suggest that all of the periplasmic TonB fragments constructed here are expressed at approximately equal rates. With respect to the level of expression of these fragments compared to the level of expression of native TonB, it should be noted that on the blots used to quantitate the periplasmic TonB fragments, native TonB was present at levels that were too low to detect. In highly overexposed films, native TonB could be observed in shocked cells but, as expected, not in the shock fluid (data not shown). Given the sensitivity of the chemiluminescence imager used to quantify the periplasmic fragments, this indicates that, at this induction level, the fragments were expressed at greater than 100 times the expression level of native TonB in these cells.

Periplasmic TonB fragments inhibit growth on iron-limited media containing ferrichrome or citrate.

Cells containing the plasmids encoding the three forms of periplasmic TonB were assayed for ability to grow on iron-limited media when provided with the siderophores ferrichrome and ferric citrate. Dipyridyl (250 μM) was added to NB plates to limit the available iron, and the plates also contained various concentrations of IPTG in order to vary the level of synthesis of the periplasmic TonB fragments. After the plates were seeded with the producing cells, disks to which 10 μl of a ferrichrome solution (1 mg/ml) or 10 or 100 mM sodium citrate had been added were placed on the plates. Cells containing the plasmid pMALp2, expressing the maltose-binding protein MalE were used as a control. As shown in Table 3, cells expressing any one of the secretory TonB fragments did not grow to the same extent as the AB2847(pMALp2) cells around the disks containing the siderophores. In addition, when the plates contained increasing concentrations of IPTG, the cells expressing the periplasmic TonB fragments were progessively more inhibited, such that those containing either pMFT or pMFTLP were incapable of growing at all in the presence of either siderophore at 1 mM IPTG. (The number 6 represents the diameter of the paper disk and indicates no visible growth zone.) At the intermediate IPTG concentrations, the largest TonB product, which was produced by the plasmid pMFT, was the most effective at inhibiting the function of wild-type TonB, while the product of pMFTLP was slightly less effective and the pMFT137 product was markedly less effective, so that it only slightly inhibited the growth around the disks containing sodium citrate. Growth on ferrichrome appeared to be much more sensitive to inhibition than growth on ferric citrate. For the pMFT transformants, even on plates that did not contain any IPTG, growth on ferrichrome was completely inhibited, whereas a concentration of 0.1 mM IPTG was required to completely inhibit the growth around the disks to which 10 or 100 mM citrate had been added. A similar pattern was observed for the cells containing either pMFTLP or pMFT137.

TABLE 3.

Growth of E. coli AB2847 transformants on NB medium containing dipyridyl

| Strain and solution (mM) | Growtha with IPTG at (mM):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | |

| AB2847(pMALp2) | ||||

| FC (1) | 25 | ND | ND | 25 |

| Cit (100) | 28 | ND | ND | 27 |

| Cit (10) | 19 | ND | ND | 18 |

| AB2847(pMFT) | ||||

| FC (1) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Cit (100) | 28 | 25 | 6 | 6 |

| Cit (10) | 17 | 16 | 6 | 6 |

| AB2847(pMFT137) | ||||

| FC (1) | 27 | 25 | 6 | 6 |

| Cit (100) | 28 | 26 | 26 | 25 |

| Cit (10) | 18 | 16 | 17 | 16 |

| AB2847(pMFTLP) | ||||

| FC (1) | 22 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Cit (100) | 28 | 25 | 20 | 6 |

| Cit (10) | 18 | 15 | 14 | 6 |

Growth was measured as the diameter in millimeters of the growth zone around 6-mm filter disks which had been saturated with 10 ml of the indicated solution of ferrichrome (FC) or sodium citrate (Cit). A value of “6” indicates there was no visible growth. ND, not determined.

Iron transport through FecA, FhuA, and corkless FhuA is inhibited by periplasmic TonB fragments.

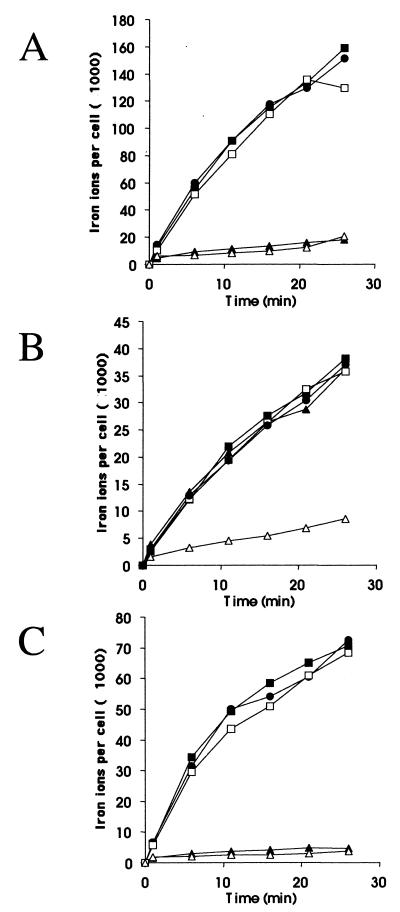

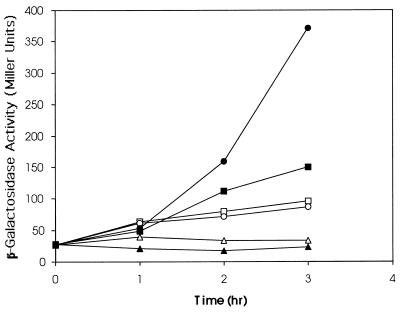

The most likely cause of the inhibition of growth on the iron-limited media by the periplasmic TonB fragments was interference with energy dependent transport of the siderophores across the outer membrane. Transport of [55Fe3+]citrate and [55Fe3+]ferrichrome were measured in AB2847 cells containing pMFT, no plasmid, or the control plasmid pMALp2. As shown in Fig. 4A, transport of [55Fe3+]ferrichrome was completely inhibited in the pMFT transformants, even when no IPTG was added to the medium used to grow the cells. The presence of the pMFT also inhibited transport of [55Fe3+]citrate by the cells, but in this case cells grown without IPTG showed only slightly decreased transport levels, whereas the transport was strongly inhibited in the cells grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG (Fig. 4B). These assays therefore also suggested that the interactions between TonB and FhuA were more sensitive to inhibition by the periplasmic TonB fragments than were those between TonB and FecA. Similar assays of ferrichrome and ferric citrate transport by pMFT137 transformants expressing TonB(103-239) and pMFTLP transformants expressing TonB(122-239) showed that both of these fragments inhibited transport of the ferric siderophores as well (see Table 6 below and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

[55Fe3+]ferrichrome transport through FhuA, [55Fe3+] citrate transport through FecA, and [55Fe3+]ferrichrome transport through FhuAΔ5-160 in cells expressing periplasmic TonB fragments. (A) AB2847 cells containing pMALp2 (squares), pMFT (triangles), or no plasmid (circles) were grown in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of 1 mM IPTG, and the time-dependent transport of [55Fe3+]ferrichrome was measured. (B) AB2847 cells containing pMALp2 (squares), pMFT (triangles), or no plasmid (circles) were grown in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of 1 mM IPTG, and the time-dependent transport of [55Fe3+]citrate was measured. (C) HK97(pSUBK17) cells containing pMALp2 (squares), pMFT (triangles), or no additional plasmid (circles) were grown in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of 1 mM IPTG, and the time-dependent transport of [55Fe3+]ferrichrome was measured.

TABLE 6.

Effect of overexpressed ExbBD on colicin E1 sensitivity and ferrichrome transport

| E. coli strain | Sensitivity to colicin E1a | E. coli strain | Relative transport of [55Fe3+]ferrichromeb (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM1 wild type | 6 | AB2847 | 100 | |

| TPS13 tolQ(R) | (3) | AB2847(pSKBD) | 100 | |

| TPS13(pMFLP) | (3) | AB2847(pMFLP) | 9 | |

| HE12 tolQ(R) tonB | 4 | AB2847(pMFLP, pSKBD) | 5 | |

| HE12(pSKBD) | 5 | AB2847(pMFT) | 7 | |

| HE12(pMFT) | 4 | AB2847(pMFT, pSKBD) | 4 | |

| HE12(pMFT, pSKBD) | 4 | AB2847(pMFT137) | 21 | |

| HE12(pMFTLP) | 4 | AB2847(pMFT137, pSKBD) | 24 | |

| HE12(pMFTLP, pSKBD) | 4 | |||

| HE12(pMFT137) | 4 | |||

| HE12(pMFT137, pSKBD) | 4 |

The value “6” means that the colicin stock solution could be diluted six times in a fivefold dilution series (final dilution, 15,625-fold) to yield a clear (in parentheses, turbid) zone of growth inhibition. The growth inhibition zone of E. coli TPS13 was turbid with undiluted E1 up to the 125-fold-diluted solution. The cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG, and the plates were inspected after 7 h of incubation at 37°C.

The values represent the percentage of transport related to the transport rate of E. coli AB2847.

It has recently been shown that a deletion derivative of FhuA which does not contain the amino-terminal cork region functions in nearly all of the TonB-dependent transport functions of FhuA and still requires TonB for this residual activity (8). FhuAΔ5-160 does not contain the TonB box region of FhuA which interacts with the Q160 region of TonB, suggesting that there must be other regions of interaction between TonB and FhuA, including parts of the FhuA β-barrel itself. We therefore determined whether the periplasmic fragments of TonB were also capable of inhibiting [55Fe3+]ferrichrome transport through the corkless FhuA derivative. E. coli HK97 with a chromosomal fhuA mutation was transformed with the plasmid pSUBK7, which encodes the FhuAΔ5-160 derivative, and either pMFT or the control plasmid pMALp2 and were assayed for [55Fe3+]ferrichrome transport as described above. The results in Fig. 4C show that as for transport of [55Fe3+]ferrichrome via wild-type FhuA, the presence of the pMFT plasmid in the cells was enough to completely inhibit transport through FhuAΔ5-160, whether or not the cells were induced with IPTG.

Expression of periplasmic TonB rescues cells from the lethal action of colicin M and bacteriophage φ80.

TonB also plays a determining role in the energy-dependent susceptibility of E. coli cells to killing by a number of bacteriophages and the type B colicins. To determine whether the expression of the periplasmic TonB fragments would have any effect on these kinds of processes, AB2847 cells containing the plasmids expressing the periplasmic fragments of TonB or the control pMALp2 were grown in various concentrations of IPTG and challenged with either bacteriophage φ80 or colicin M. As shown in Table 4, killing of the AB2847 cells by both colicin M and φ80 was inhibited, again in an expression-dependent manner, by the periplasmic TonB fragments. For both lethal agents, the cells containing pMFT were much more resistant at the highest concentrations of IPTG tested, whereas cells containing the control pMALp2 remained fully sensitive. Again, the intermediate TonB(103-239) fragment was much less effective at interfering with the function of TonB, providing protection to the cells only when fully induced with 1 mM IPTG. The TonB(122-239) fragment was nearly as effective as the full-length fragment.

TABLE 4.

Susceptibility of E. coli AB2847 transformants to colicin M and phage φ80

| Strain and treatment | Strain susceptibilitya with IPTG at (mM):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | |

| AB2847(pMALp2) | ||||

| Colicin M | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| φ80 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| AB2847(pMFT) | ||||

| Colicin M | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| φ80 | 8 | 8 | (4) | (3) |

| AB2847(pMFT137) | ||||

| Colicin M | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| φ80 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| AB2847(pMFTLP) | ||||

| Colicin M | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| φ80 | 8 | 8 | (5) | (4) |

Samples (5 μl) containing 10-fold dilutions of bacteriophage φ80 or colicin M stock solutions were spotted onto lawns of the indicated bacteria. The results are presented as the −log of the highest dilution that resulted in a confluent lysis zone. Numbers in parentheses indicate that, although the lysis zone was confluent, it was cloudy, indicating poor propagation of the phage.

Periplasmic TonB fragments inhibit the FecARI-dependent induction of the fec operon by citrate.

For the ferric citrate uptake system, TonB plays a direct role in the Fec signal transduction pathway as well as in the actual transport of the siderophore (25). In order to assess the effect of the periplasmic TonB on the FecARI-mediated induction of the fec operon, pMFTC was transformed into E. coli ZI418, which contains a fecB-lacZ fusion (47). The transformed cells were then grown in various concentrations of citrate, and the level of induction of the fec operon was measured as the increase in β-galactosidase activity of the cultures. Figure 5 shows that the control cells displayed a citrate concentration-dependent increase in β-galactosidase activity, reflecting increased fec transcription even though there is no transport because of the fecB-lacZ gene fusion. In the presence of 1 mM IPTG, the induction was clearly inhibited, so that at a concentration of 0.1 mM citrate, the β-galactosidase activity remained close to the uninduced level and, even at 1 mM citrate, attained a level after 3 h of induction only about 30% of that shown by the cells growing in 1 mM citrate in the absence of IPTG.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of citrate-dependent induction of the fec operon by periplasmic TonB. ZI418 cells containing pMFT were grown in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of 1 mM IPTG, and 0, 0.1, or 1 mM sodium citrate was added to the cultures. At this time and for the following 3 h, the cultures were assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Symbols: triangles, 0 mM sodium citrate; squares, 0.1 mM sodium citrate; circles, 1 mM sodium citrate.

Overexpression of FhuA reverses the inhibitory effects of the periplasmic TonB fragments.

The inhibition of ferrichrome and ferric citrate transport, as well as fec gene induction, and the rescue of cells from colicin M and bacteriophage φ80 could all be caused by the interference by the periplasmic TonB fragments of interactions between the outer membrane siderophore receptors and native TonB. However, it is also possible that the fragments could form nonfunctional mixed dimers with native TonB (10). We therefore examined the ability of the periplasmic fragments to inhibit transport functions in cells that were also overproducing FhuA. AB2847 cells expressing the various fragments as well as the fhuA gene on the multicopy plasmid pSU767 were assayed for ability to grow on ferrichrome and ferric citrate, as well as for sensitivity to colicin M and bacteriophage φ80 as described above. As shown in Table 5, cells containing the fhuA plasmid were restored to essentially wild-type levels with respect to ability to grow on ferrichrome and sensitivity to colicin M while remaining only slightly resistant to bacteriophage φ80. We also observed that even though the transport of ferric citrate requires FecA rather than FhuA, the presence of the fhuA plasmid also restored somewhat the ability of the cells to grow using ferric citrate as the siderophore (Table 5). In both cases, the restoration suggests that the overproduction of the siderophore receptor acts to reduce the ability of the periplasmic TonB fragments to successfully compete with native TonB for an available receptor.

TABLE 5.

Effect of overexpressed FhuA on siderophore-dependent growth and sensitivity to colicin M and bacteriophage φ80

| Strain | Plasmid | Growtha on:

|

Sensitivityb with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC at 1 mM | Cit at 10 mM | Cit at 100 mM | φ80 | Colicin M | ||

| AB2847(pMALp2) | pACYC184 | 20 | 14 | 22 | 6 | 3 |

| pSU767 | 20 | 14 | 23 | 6 | 3 | |

| AB2847(pMFT) | pACYC184 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (3) | 1 |

| pSU767 | 20 | 13 | 17 | 5 | 2 | |

| AB2847(pMFT137) | pACYC184 | 6 | 15 | 23 | 5 | 2 |

| pSU767 | 21 | 14 | 20 | 6 | 3 | |

| AB2847(pMFTLP) | pACYC184 | 6 | 13 | 21 | 4 | 2 |

| pSU767 | 20 | 14 | 21 | 5 | 3 | |

Growth was measured as the diameter in millimeters of the growth zone around 6-mm filter disks which had been saturated with 10 μl of the indicated solution of ferrichrome (FC) or sodium citrate (Cit). The cells were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG.

Tenfold dilutions of bacteriophage φ80 or colicin M were spotted onto lawns of the indicated bacteria induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. The results are presented as the −log of the highest dilution that resulted in a confluent zone of lysis. Numbers in parentheses indicate a zone of lysis that was confluent but cloudy, indicating poor propagation of the phage.

Overexpression of ExbB and ExbD does not restore siderophore transport to cells expressing the periplasmic TonB fragments.

If TonB interacts in the periplasm with ExbB and ExbD, the TonB fragments may also inhibit the activities of ExbB and ExbD by direct binding to ExbB and ExbD or by preventing complex formation between TonB, ExbB, and ExbD (15, 20, 46). We employed two approaches to test this possibility. As we have shown previously, there is partial cross-reactivity between ExbBD and TolQR in that ExbBD contribute to TolA activity in tolQR mutants and TolQR contribute to TonB activity in exbBD mutants (5, 7). The tonB tolQ(R) mutant E. coli HE12 with a polar effect on tolR is remarkably sensitive to colicin E1 even though tolQR are required for the TolA-dependent uptake of the colicin. The colicin E1 sensitivity of E. coli HE12 was related to the lack of TonB activity in this strain since the sensitivity of the tolQ(R) parent strain TPS13 tonB+ was lower. The conclusion was that, in the absence of TonB, ExbBD activated TolA more than it did in the presence of TonB, to which ExbBD preferentially binds (7). Therefore, if the periplasmic TonB fragments bind to ExbBD, the increase in colicin E1 sensitivity of HE12 should not be observed. In the second approach, the ExbBD proteins were overexpressed with the view that if the TonB fragments inhibit by binding to ExbBD, then a surplus of ExbBD should overcome the titration of ExbBD and thus relieve the inhibition of TonB-dependent functions.

As shown in Table 6, the TonB fragments encoded by pMFT, pMFT137, and pMFTLP did not reduce the sensititivity of E. coli HE12 to colicin E1. In addition, inhibition of FhuA-mediated ferrichrome transport by pMFT, pMFT137, and pMFTLP was not reversed by the presence of pSKBD (Table 6). Citrate-mediated iron transport into E. coli AB2847 transformed by pMFT, pMFT137, or pMFTLP was inhibited to ca. 11% of the untransformed cells and remained on a similar level after overexpression of ExbBD encoded by pSKBD (13% transport rate). In addition, all of the fragments were capable of inhibiting ferrichrome and ferric citrate transport even in the presence of overexpressed ExbBD. Growth in the absence of IPTG (no tonB fragment induction) did not alter colicin E1 sensitivity but increased ferrichrome transport rates of AB2847(pMFLP) to 17% and of AB2847(pMFLP, pSKBD) to 33% of the AB2847 transport level. The latter result shows an effect of ExbBD overexpression in the presence of low amounts of the TonB fragment.

DISCUSSION

In this study, TonB fragments which encompass part or all of the large periplasmic domain but do not contain the membrane anchor domain essential for TonB activity were expressed in E. coli. The full-length periplasmic domain, as well as smaller ones, was expressed as a fusion protein containing the FecA signal sequence, resulting in its localization to the periplasm.

The periplasmic domain of TonB apparently engages in many of the interactions with siderophore transporters that native TonB is involved in. Overexpression of the periplasmic TonB fragments in E. coli abolished sensitivity of cells to bacteriophage φ80 and the lethal action of colicin M, both of which use FhuA as the receptor. Cells producing the periplasmic TonB fragments were also unable to grow on low-iron media when supplemented with either ferrichrome, for which FhuA is the transporter, or ferric citrate, which is transported into the periplasm by FecA. Transport assays employing 55Fe3+-loaded ferrichrome or ferric citrate confirmed that the transport of both of these siderophores was inhibited when the periplasmic TonB fragments were overproduced. It is not clear which specific region(s) of the fragments is responsible for the inhibitions observed, especially in the case of the largest fragment, which was subject to degradation. However, it is clear that a fragment encompassing only the last 118 amino acids of the protein is sufficient to interfere with TonB function.

Of particular interest was the interference of the TonB(33-239) fragment with ferrichrome transport mediated by FhuAΔ5- 160, since it can be compared with the previous finding that FhuAΔ5-160 exhibits TonB-dependent ferrichrome transport despite the removal of the TonB box along with the cork (8). The conclusion that FhuA must engage in specific interactions with TonB not only through the TonB box but also via the FhuA barrel is supported by the inhibition of FhuAΔ5-160 transport activity by the TonB fragment observed here.

β-Galactosidase assays of a fecB::lacZ E. coli strain expressing TonB(33-239) and grown in the presence or absence of citrate demonstrated that TonB(33-239) also inhibited the FecA- and TonB-dependent induction of the fecABCDE operon (12). For inhibition of fecB induction, synthesis of the TonB(33-239) fragment had to be induced by IPTG, which is consistent with the finding that inhibition of growth on ferric citrate also required IPTG induction. In contrast, ferrichrome-dependent growth and transport of 55Fe3+-loaded ferrichrome were inhibited by TonB(33-239) even when it was expressed at basal levels from uninduced cells containing pMFT. The need for higher amounts of TonB(33-239) for inhibition of ferric citrate-mediated induction and transport may result from the signaling peptide in front of the TonB box that comprises 78 residues of mature FecA (25), which for steric reasons may limit the access of the TonB box and other regions to which TonB might bind. Steric hindrance of the access of the TonB fragments to FecA may be more pronounced than steric hindrance of complete and energized TonB since the fragments may not assume the conformation of wild-type TonB and the shorter fragments may lack regions of interaction with FecA. The TonB fragments may also bind less well to the regions with which FecA interacts with TonB than to the FhuA interacting regions. The need for a large surplus of the fragments over wild-type TonB to inhibit wild-type TonB activity supports this notion.

Another possibility that would explain the results oberved in the cells expressing the TonB fragments is that they interfere with interactions between TonB and ExbB and/or ExbD. If interactions between the TonB fragments and these proteins occurred in the periplasm, they could either inhibit ExbB and ExbD activity by direct binding to a complex that contains native TonB or by preventing (by titration) proper complex formation between TonB, ExbB, and ExbD (15, 20, 46). The remarkable sensitivity of HE12 tolQ(R) tonB to colicin E1, despite the fact that tolQR are required for TolA activity, provided a means to test this possibility. As found previously, the tonB mutant (HE12) displayed a higher sensitivity to colicin E1 than TPS13 tolQ(R) tonB+ from which it was derived. Overexpression of ExbBD somewhat increased colicin E1 sensitivity. The TonB fragments expressed in HE12 did not decrease colicin E1 sensitivity, but they inhibited enhancement of colicin E1 sensitivity by overexpressed ExbBD. This result and the enhancement of ferrichrome transport by overexpressed ExbBD when low amounts of the TonB(122-239) fragment are in the cells suggests some influence of TonB fragments on ExbBD activity which, however, is much lower than their direct effect on transport protein activities.

In vivo competition between wild-type and mutant TonB was determined previously (1). In this case, both proteins were anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane and could respond to the proton motive force. Overexpressed wild-type TonB prevented activation of chromosomally encoded BtuB(L8P) by chromosomally encoded mutant TonB(Q160K). These regions of TonB and BtuB, which include the TonB box residues for BtuB (19), have since been shown to interact by in vivo disulfide cross-linking and site-directed spin-labeling studies (11, 34). These competition experiments did not address the question, as was done here, of whether TonB that cannot be energized since it is devoid of the portion located in the cytoplasmic membrane can functionally interfere with wild-type TonB.

TonB(33-239) inhibited growth on ferrichrome and ferric citrate more strongly than TonB(103-239) or TonB(122-239) did, even though all three fragments were produced in approximately equal amounts according to estimates from chemiluminescent blots. However, it was not only the size of the TonB fragments that was important for inhibition, since inhibition by TonB(122-239) was stronger than inhibition by the larger TonB(103-239) fragment. The TonB(122-239) fragment does not contain the seven-amino-acid linker sequence incorporated during the construction of the TonB(33-239) and TonB(103-239) fusion proteins. As a result, the TonB fragments may differ somewhat in folding, or these differences may directly affect binding to the transport proteins. Previously, a truncated tonB gene with an amber mutation in codon 175 was inactive (27) and 90% of the protein was found in the cytoplasmic membrane (30). This TonB fragment was not chemically cross-linked to FepA in the outer membrane. If the C terminus was intact, TonB was found to be associated with the outer membrane regardless of whether it was energized or not, as shown by the dissipation of the proton motive force by CCCP and by the association with the outer membrane of an inactive TetA-TonB hybrid protein in which the cytoplasmic membrane portion of TonB was replaced by the cytoplasmic membrane fragment of TetA. The in vivo competition experiments described here suggest that the fragments partake in functionally relevant interactions as opposed to physical but possibly unproductive interactions. The experiments suggest that unenergized TonB fragments with N-terminal deletions interact with the FecA and FhuA proteins and prevent TonB-dependent signaling and transport. It is also possible that the TonB fragments could form mixed (nonfunctional) dimers with wild-type TonB, the carboxyl-terminal domain of which was recently shown to be a dimer (10). The relief of the inhibition by overexpression of the outer membrane receptors, however, suggests that it is competition for the receptors which causes the inhibition. Alternatively, but perhaps less likely, a few wild-type TonB homodimers may be formed in competition with heterodimers formed between wild-type TonB and the large surplus of TonB fragments. Increasing the amount of FhuA would then increase the probability of interaction with the TonB homodimers. However, the restoration of growth on ferrichrome to nearly wild-type levels by a few functional TonB homodimers is difficult to envisage. In any case, these findings may explain why plasmid-encoded overexpressed wild-type TonB displays less activity than chromosomally encoded TonB (33). It may be that the excess TonB cannot be energetically charged, perhaps because of a shortage of ExbBD or through a shortage of sites in the cell at which this can take place. In this case, the portion of TonB that is unenergized may interfere with the function of energized TonB.

Under iron-limiting aerobic conditions transcription of the six ferric siderophore transport genes of E. coli K-12 is increased up to 30-fold, whereas transcription of the tonB gene is increased only 2- to 3-fold (40). In addition, competition for TonB function has been demonstrated by the mutual inhibition of ferrichrome and cobalamin uptake (22). The direct evidence of competition, the low numbers of TonB molecules relative to receptor proteins, the crystal structure evidence of a large reorientation of the TonB box of the receptors following ligand binding, and the cross-linking and in vitro binding studies all suggest that, in vivo, TonB must recognize and bind only to loaded receptors in the outer membrane. The results obtained with the periplasmic TonB fragments suggest that TonB must be able to select these loaded receptors whether or not it is in an energized state, since the fragments could not be energized and yet still interfered with these interactions. In addition, the results provide further evidence that the interactions between TonB and the siderophore transporters extend beyond the interaction between the Q160 region of TonB and the TonB box sequence of the siderophore transporters (2, 11, 42). Experiments are under way to isolate noninhibitory single site mutants of the TonB fragments with the aim of identifying sites that are involved in the interactions of these fragments with the outer membrane transporters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Klaus Hantke, Universität Tübingen, for expert advice and stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants SFB 323, B1, and BR330/20–1 to V.B.) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MT10470 to S.P.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anton M, Heller K J. The wild-type allele of tonB in Escherichia coli is dominant over the tonB1 allele, encoding TonBQ160K, which suppresses the btuB451 mutation. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:371–377. doi: 10.1007/BF00276935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell P E, Nau C D, Brown J T, Konisky J, Kadner R E. Genetic suppression demonstrates interaction of TonB protein with outer membrane transport proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3826–3829. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3826-3829.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bös C, Lorenzen D, Braun V. Specific in vivo labeling of cell surface-exposed protein loops: reactive cysteines in the predicted gating loop mark a ferrichrome binding site and a ligand-induced conformational change of the Escherichia coli FhuA protein. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:605–613. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.605-613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradbeer C. The proton motive force drives the outer membrane transport of cobalamin in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3146–3150. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3146-3150.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V. The structurally related exbB and tolQ genes are interchangeable in conferring tonB-dependent colicin, bacteriophage, and albomycin sensitivity. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6387–6390. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6387-6390.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun V. Surface signaling: novel transcription initiation mechanism starting from the cell surface. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s002030050451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun V, Herrmann C. Evolutionary relationship of uptake systems for biopolymers in Escherichia coli: crosscomplementation between the TonB-ExbB-ExbD and the TolA-TolQ-TolR proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun M, Killmann H, Braun V. The β-barrel domain of FhuAΔ5-160 is sufficient for TonB-dependent FhuA activities of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1037–1049. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan S K, Smith B S, Venkatramani L, Xia D, Esser L, Palnitkar M, Chakraborty R, van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang C, Mooser A, Plückthun A, Wlodawer A. Crystal structure of the dimeric domain of TonB reveals a novel fold. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27535–27540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cadieux N, Kadner R J. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals an interaction site between energy-coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enz S, Braun V, Crosa J H. Transcription of the region encoding the ferric dicitrate-transport system in Escherichia coli: similarity between promoters for fecA and for extracytoplasmic function signa factors. Gene. 1995;163:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00380-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enz S, Mahren S, Stroeher U H, Braun V. Surface signaling in ferric citrate transport gene induction: interaction of the FecA, FecR, and FecI regulatory proteins. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:637–646. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.637-646.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson A D, Hofmann E, Coulton J W, Diederichs K, Welte W. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1998;282:2215–2220. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer E, Günter K, Braun V. Involvement of ExbB and TonB in transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: phenotypic complementation of exb mutants by overexpressed tonB and physical stabilization of TonB by ExbB. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5127–5134. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5127-5134.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanahan D. Studies in transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hantke K, Braun V. Functional interaction of the tonA/tonB receptor system in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:190–197. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.1.190-197.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Härle C, Kim I, Angerer A, Braun V. Signal transfer through three compartments: transcription initiation of the Escherichia coli ferric citrate transport system from the cell surface. EMBO J. 1995;14:1430–1438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heller K J, Kadner R J, Günther K. Suppression of the btuB451 mutation by mutations in the tonB gene suggests a direct interaction between TonB and TonB-dependent receptor proteins in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;64:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgs P I, Myers P S, Postle K. Interactions in the TonB-dependent energy transduction complex: ExbB and ExbD form homomultimers. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6031–6038. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.6031-6038.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaskula J C, Letain T E, Roof S K, Skare J T, Postle K. Role of the TonB amino terminus in energy transduction between membranes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2326–2338. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2326-2338.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadner R J, Heller K J. Mutual inhibition of cobalamin and siderophore uptake systems suggests their competition for TonB function. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4829–4835. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4829-4835.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson M, Hannavy K, Higgins C F. A sequence-specific function for the N-terminal signallike sequence of the TonB protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:379–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killmann H, Braun V. An aspartate deletion mutation defines a binding site of the multifunctional FhuA outer membrane receptor of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3479–3486. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3479-3486.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim I, Stiefel A, Plantör S, Angerer A, Braun V. Transcription induction of the ferric citrate transport genes via the N-terminus of the FecA outer membrane protein, the Ton system and the electrochemical potential of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:333–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2401593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen R A, Foster-Hartnett D, McIntosh M A, Postle K. Regions of Escherichia coli TonB and FepA proteins essential for in vivo physical interactions. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3213–3221. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3213-3221.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen R A, Thomas M G, Postle K. Protonmotive force, ExbB and ligand-bound FepA drive confomational changes in TonB. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1809–1824. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen R A, Wood G E, Postle K. The conserved proline-rich motif is not essential for energy transduction by Escherichia coli TonB protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:943–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Letain T E, Postle K. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3331703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locher K P, Rees B, Koebnik R A, Mitchler, Moulinier L, Rosenbusch R, Moras D. Transmembrane signaling across the ligand-gated FhuA receptor: crystal structures of free and ferrichrome-bound states reveal allosteric changes. Cell. 1998;95:771–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locher K P, Rosenbusch J P. Oligomeric states and siderophore binding of the ligand-gated FhuA protein that forms channels across Escherichia coli outer membranes. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:770–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann B J, Holroyd C D, Bradbeer C, Kadner R J. Reduced activity of TonB-dependent functions in strains of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;33:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merianos H J, Cadieux N, Lin C H, Kadner R J, Cafiso D S. Substrate-induced exposure of an energy-coupling motif of a membrane transporter. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:205–209. doi: 10.1038/73309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moeck G S, Letellier L. Characterization of in vitro interactions between a truncated TonB protein from Escherichia coli and the outer membrane receptors FhuA and FepA. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2755–2764. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2755-2764.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moeck G S, Coulton J W, Postle K. Cell envelope signaling in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28391–28397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moeck G S, Tawa P, Xiang H, Ismail A A, Turnbull J L, Coulton J W. Ligand-induced conformational change in the ferrichrome-iron receptor of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:459–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilsl H, Glaser C, Gross P, Killmann H, Ölschläger T, Braun V. Domains of colicin M involved in uptake and activity. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;240:103–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00276889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Postle K. Aerobic regulation of the Escherichia coli tonB gene by changes in iron availability and the fur locus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2287–2293. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2287-2293.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schöffler H, Braun V. Transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12 via the FhuA receptor is regulated by the TonB protein of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02464907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Studier F W, Moffat B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun T-P, Webster R E. fii, a bacterial locus required for filamentous phage infection and its relation to colicin-tolerant tolA and tolB. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:107–115. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.1.107-115.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Traub I, Gaisser S, Braun V. Activity domains of the TonB protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:409–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Hove B, Staudenmaier H, Braun V. Novel two-component transmembrane transcription control: regulation of iron dicitrate transport in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6749–6758. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6749-6758.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willis R C, Morris R G, Cirakoglu C, Schellenberg G D, Gerber N H, Furlong C E. Preparation of the periplasmic binding proteins from Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;161:64–75. [Google Scholar]