Abstract

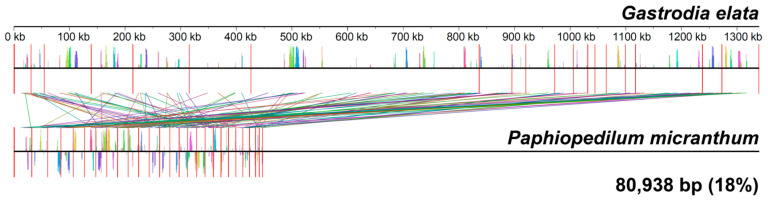

Orchidaceae is one of the largest families of angiosperms. Considering the large number of species in this family and its symbiotic relationship with fungi, Orchidaceae provide an ideal model to study the evolution of plant mitogenomes. However, to date, there is only one draft mitochondrial genome of this family available. Here, we present a fully assembled and annotated sequence of the mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) of Paphiopedilum micranthum, a species with high economic and ornamental value. The mitogenome of P. micranthum was 447,368 bp in length and comprised 26 circular subgenomes ranging in size from 5973 bp to 32,281 bp. The genome encoded for 39 mitochondrial-origin, protein-coding genes; 16 tRNAs (three of plastome origin); three rRNAs; and 16 ORFs, while rpl10 and sdh3 were lost from the mitogenome. Moreover, interorganellar DNA transfer was identified in 14 of the 26 chromosomes. These plastid-derived DNA fragments represented 28.32% (46,273 bp) of the P. micranthum plastome, including 12 intact plastome origin genes. Remarkably, the mitogenome of P. micranthum and Gastrodia elata shared 18% (about 81 kb) of their mitochondrial DNA sequences. Additionally, we found a positive correlation between repeat length and recombination frequency. The mitogenome of P. micranthum had more compact and fragmented chromosomes compared to other species with multichromosomal structures. We suggest that repeat-mediated homologous recombination enables the dynamic structure of mitochondrial genomes in Orchidaceae.

Keywords: Orchidaceae, slipper orchid, hybrid assembly, multichromosomal genome, intracellular gene transfer

1. Introduction

The mitochondrion is a key organelle involved in a series of cellular processes. Angiosperm mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) are characterized by a low mutation rate, a highly dynamic genome structure, extensive variation in genome size, long non-coding regions, frequent recombination, RNA editing, and widespread horizontal gene transfer [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. For instance, the smallest mitogenome is found in the hemiparasitic Viscum scurruloideum, with a length of 66 kb [8], whereas the mitogenome of Silene conica has expanded to 11.3 Mb [9]. Earlier studies have indicated that plant mitogenomes exist as circular structures. However, there is increasing evidence that the genomic conformation of mitogenomes can be more complex than just one circular structure. Electron micrographs of the mitochondria of Chenopodium album have shown a subgenome that is circular with a linear tail [10], while some species even show a complex branched structure [11], and a multichromosomal structure has been independently identified in multiple lineages [3,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. For example, the mitogenome of S. conica consists of 128 circular chromosomes ranging in size from 44 kb to 163 kb [9]. The number of mitochondrial chromosomes ranges from 2 in multiple species to 132 in Picea glauca [17]. Furthermore, the mitochondrial genes have shown a disparity in their substitution rates [20,21,22], and the synonymous substitution rate in Ajuga has shown a 340-fold range [20]. In contrast, Liriodendron tulipifera has a “fossilized” mitochondrial genome, which has undergone little change over the last 100 million years [23].

Angiosperm mitogenomes are poorly characterized compared to their plastomes or to animal mitogenomes (NCBI database, 351 land plants mitogenomes, 13 July 2022) and are dominated by species from the crop families, such as Brassicaceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, and Solanaceae [24]. In addition, the complexity of mitogenome assembly is exacerbated by their multichromosomal structure, recombination, lengthy repeat sequences in intergenic spacer regions and introns, and horizontal gene transfer events [11]. For instance, the intron of cox2 expanded to 11.4 kb in Nymphaea colorata, and the repeat sequences accounted for 49% of its mitogenome [25]. The total length of repeat sequences in S. conica even reaches 4621 kb and accounts for 40.8% of the mitogenome [9]. Repeat-mediated homologous recombinations have resulted in different conformations coexisting in the same species [19,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In some cases, the long, plastid-like sequences will lead to erroneous extensions that produce chimeric contigs comprising both mitogenomic and plastomic sequences [31]. With the rapid advances in long-read sequencing technologies and assembly methods, long repeat regions and plastid-derived fragments in the plant mitogenomes [32,33] can now be resolved, which will facilitate the study of angiosperm mitogenomes.

Orchidaceae is one of the largest families of angiosperms, with about 28,000 species (World Checklist of Orchidaceae). All orchids depend on mycorrhizal fungi for seed germination in their initial stage of development, and many orchids rely on mycorrhizal fungi for nutrients in their later life [34,35,36]. The symbiotic relationship between orchids and fungi makes orchids an outstanding candidate for investigating the evolution of mitogenomes. There has only been one draft-assembled mitogenome of Orchidaceae reported to date: the mitogenome of holo-heterotrophic Gastrodia elata, consisting of 19 contigs (13.5 kb to 410.3 kb) with a total length of 1340 kb, which is one of the largest mitogenomes of angiosperms sequenced, to date [37]. Further, there are six other orchid species from the subfamily Epidendroideae with multichromosomal structures available in GenBank (unpublished data). The general features of a mitogenome from other clades of Orchidaceae are unknown. Considering the large species number in this family, the mitogenome evolution of orchids needs more case studies. Furthermore, previous studies have shown widespread intracellular gene transfer or horizontal gene transfer, including plastome-to-mitogenome gene transfer, mitogenome-to-nuclear gene transfer, and horizontally transferred foreign sequences in the mitogenome obtained from unrelated plant species [3,12,16,23,31,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Zhao et al. [38] summarized that the mitochondrion is the source of horizontal gene transfer. For instance, the mitogenome of Amborella trichopoda contains entire mitogenomes from three green algae and one moss [3]. Choi et al. [41] identified non-retroviral endogenous RNA viral elements (NERVEs) and transposable elements across legume mitogenomes. Further, the symbiosis between orchids and fungi likely boosts the opportunities for horizontal gene transfer between them. Moreover, Sinn and Barrett [31] found two ancient horizontal transfer events between orchids and fungi: one 270 bp fragment encoding three tRNA genes obtained from the mitogenome of fungi and the other > 8 kb fragment encoding 14 genes from a fungal mitogenome to the mitogenome of ancestors of the subfamily Epidendroideae. Further, Sinn and Barrett [31] speculated that the horizontal events involving plant mitogenomes might be underestimated, owing to the lack of completely sequenced genomes. However, the work of Sinn and Barrett [31] did not cover species from the subfamily Cypripedioideae.

In this study, we report the sequencing, assembling, and annotation of the mitogenome of Paphiopedilum micranthum using a combination of Illumina and PacBio sequencing platforms. P. micranthum is a species that was first described in 1951; it is known as the “silver slipper orchid”, has high ornamental value, and is distributed from the north of Vietnam to the southwest of China [46]. We aimed to decipher the structure and gene content of the mitogenome of P. micranthum and compare the P. micranthum mitogenome with the G. elata mitogenome. Furthermore, we wanted to assess the intracellular gene transfer between the plastome and mitogenome of P. micranthum, and test the horizontal gene transfer between the mitogenome and fungi detected by Sinn and Barrett [31]. Finally, we calculated the recombination frequency of the repeat pairs and tested the relation between repeat length and the recombination frequency.

2. Results

2.1. The Multichromosomal Structure of the P. micranthum Mitogenome

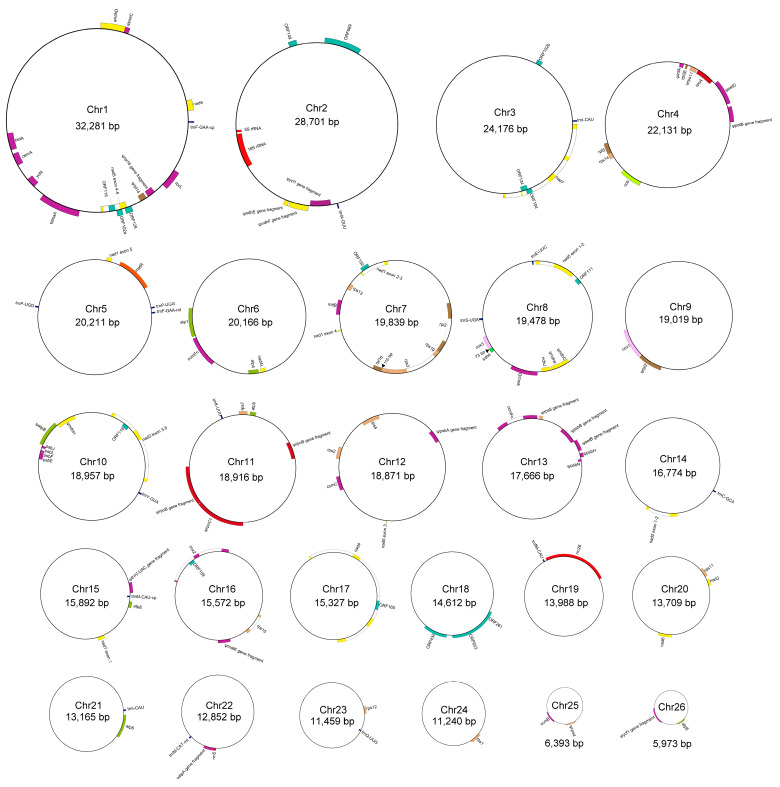

The mitogenome of P. micranthum was assembled into 26 circular chromosomes with lengths ranging from 5973 bp to 32,281 bp, with a total length of 447,368 bp (Figure 1). The average GC content of the P. micranthum mitogenome was 44.4%, ranging between 40.4% and 49.2% among chromosomes (Table 1). We obtained, for most of the chromosomes, a sequencing depth above 40× for the long reads and 500× for the short reads (Table S1). Both long- and short-read assemblies were almost identical, except for Chr5 (20,211 bp), which existed as one circular sequence in the short-read sample and fragmented into Chr5A (9033 bp) and Chr5B (11,178 bp) in the long-read sample. Both minicircles were supported by 32 and 102 long reads, respectively (Figure S1). The mitogenome of P. micranthum encoded 70 genes, including 39 mitochondrial protein-coding genes, 12 plastome-derived protein-coding genes, 16 tRNA genes, and three rRNA genes (rrn5, rrn18, and rrn26) (Figure 2, Table 2). Further, 16 ORFs coding for hypothetical proteins with BLAST hits were preserved (Figure 1, Table 2 and Table S2). In addition to the copy of rrn5 on Chr2, which is identical to the one annotated in G. elata [37], the copy on Chr22 was truncated at the 5’ end (88 bp) and relatively shorter than the normal one. Each chromosome had one to four genes, whereas Chr18, with a length of 14,612 bp, was devoid of functional genes (Figure 1). Further, the “empty” sequence presented no significant similarities to the sequences in GenBank.

Figure 1.

Map of the Paphiopedilum micranthum mitogenome. The genome consisted of 26 circular chromosomes. Genes drawn inside and outside each circle are transcribed clockwise and counterclockwise. Two triangles show the positions of the overlapping of cox3-sdh4 and rpl16-rps3, with the length of overlap indicated.

Table 1.

General features of the mitogenome of Paphiopedilum micranthum.

| Genome Feature | Paphiopedilum micranthum |

|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 447,368 |

| Numbers of contigs | 26 |

| Contig length | 5973 to 32,281 |

| GenBank Nos | OP465200–OP465225 |

| GC content (%) | 40.4% to 49.2% |

| Length of the coding region (%) | 40,029 (8.95%) |

| Length of rRNA genes (%) | 5563 (1.24%) |

| Length of tRNA genes (%) | 1206 (0.27%) |

| Length of cis-spliced introns (%) | 27,985 (6.26%) |

| length of the plastid-derived sequence (%) | 46,273 (10.34%) |

| Number of protein-coding genes (native) | 39 |

| Number of protein-coding genes (plastid derived) | 12 |

| Number of rRNA genes | 3 |

| Number of tRNA genes (native) | 13 |

| Number of tRNA genes (plastid derived) | 3 |

| Total genes | 70 |

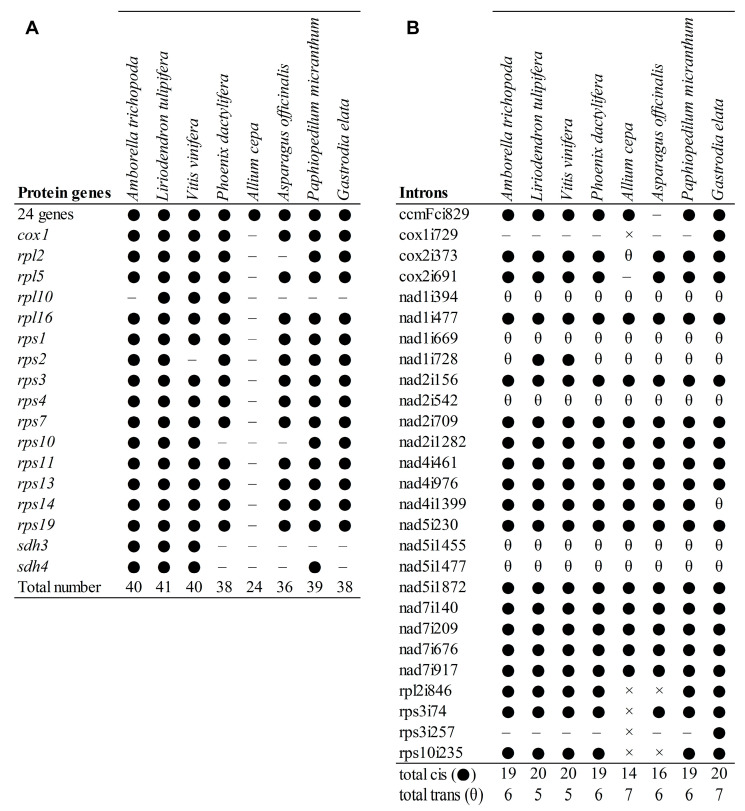

Figure 2.

Comparison of the protein-coding gene content and group II intron content of Paphiopedilum micranthum and selected angiosperms. (A) protein-coding gene content. ● indicates present, – indicates lost; the 24 genes present in all sampled species include atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, ccmFn, cob, cox2, cox3, matR, mttB, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, nad9, and rps12. (B) group II intron content. ● indicates cis-spliced intron present, – intron lost, θ trans-spliced intron present, × intron loss due to gene loss.

Table 2.

Gene content of the mitogenome of Paphiopedilum micranthum.

| Chromosome | Length (bp) |

GC Content (%) | Genes of Mitochondrial Origin | Genes of Chloroplast Origin | ORF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | 32,281 | 42.2 | nad5 exon 4, nad5 exon 5, nad9 | cemA, ψndhD, petA, ψpsaA, ψpsaC, rbcL, ψrpl14, ψrpl16 fragment, ycf4, trnF-GAA-cp | ORF102a, ORF116, ORF128 |

| Chr2 | 28,701 | 43.1 | rrn5, rrn18 | ψndhE fragment, ψndhF fragment, ψycf1 fragment, trnN-GUU | ORF149, ORF669 |

| Chr3 | 24,176 | 46.8 | nad7, trnI-CAU | — | ORF102b, ORF104, ORF124 |

| Chr4 | 22,131 | 42.7 | cob, rpl5, rps14 | ψpetB fragment, ψpetD fragment, rpoA, ψrps11, rpl36, ψinfA | |

| Chr5 | 20,211 | 45.3 | matR, nad1 exon 5, trnF-GAA-mt, trnP-UGG (2) | — | |

| Chr6 | 20,166 | 43.1 | atp1, atp4, ccmFn, nad4L | — | |

| Chr7 | 19,839 | 47.2 | mttB, rpl2, rpl16, rps3, rps13, rps19, nad1 exon 2, nad1 exon 3, nad1 exon 4 | — | ORF152 |

| Chr8 | 19,478 | 43.1 | nad5 exon1, nad5 exon2, trnE-UUC, trnS-UGA, cox3, sdh4 | ψaccD, ndhJ, ψndhK, ψndhC | ORF111 |

| Chr9 | 19,019 | 45.8 | cox1 | ψrpl2 | |

| Chr10 | 18,957 | 46.1 | nad2 exon 3, nad2 exon 4, nad2 exon 5, trnY-GUA | ψndhH, ψatpB, psbJ, psbL, psbF, psbE | ORF119 |

| Chr11 | 18,916 | 42.2 | atp9, rps7, trnK-UUU | ψrpoB fragment, ψrpoC1 | |

| Chr12 | 18,871 | 43.9 | ccmC, rps2, rps4, nad5 exon3 | ψpsbA fragment | |

| Chr13 | 17,666 | 44.6 | ccmFc | ψpsbN, ψpsbH, ψpetB fragment, ψpsbB fragment, ψrps8 fragment | |

| Chr14 | 16,774 | 44.9 | nad2 exon1, nad2 exon2, trnC-GCA | — | |

| Chr15 | 15,892 | 43.3 | nad1 exon1 | atpE, ψtrnV-UAC fragment, trnM-CAU-cp | |

| Chr16 | 15,572 | 46.1 | cox2, rps10 | ψmatK fragment | ORF109 |

| Chr17 | 15,327 | 49.2 | nad4 | — | ORF165 |

| Chr18 | 14,612 | 41.2 | — | — | ORF261, ORF432, ORF603 |

| Chr19 | 13,988 | 45.5 | rrn26, trnfM-CAU-mt | — | |

| Chr20 | 13,709 | 45.8 | nad3, nad6, rps11 | — | |

| Chr21 | 13,165 | 45.4 | atp6, trnI-CAU | — | |

| Chr22 | 12,852 | 46.3 | rrn5 fragment, trnM-CAU | ψatpA fragment | |

| Chr23 | 11,459 | 43.2 | rps12, trnQ-UUG | — | |

| Chr24 | 11,240 | 44.9 | rps1 | — | |

| Chr25 | 6393 | 40.4 | ccmB | ψrps4 | |

| Chr26 | 5973 | 42.2 | atp8 | ψycf1 fragment |

Most of the mitochondrial genes had a conserved gene length, whereas some genes varied greatly in length, e.g., atp6 expanded to 1272 bp, atp9 expanded to 327 bp, sdh4 contracted to 204 bp (Table S3), and these three genes underwent RNA editing according to the prediction in PREPACT. Furthermore, we identified 25 Group II introns, including 19 cis-spliced introns and six trans-spliced introns, located in seven cis-splicing genes (ccmFc, cox2, nad4, nad7, rpl2, rps3, and rps10) and three trans-splicing genes (nad1, nad2, and nad5) (Figure 1, Table 2 and Table S4). The exons of nad1, nad2, and nad5 were encoded on different chromosomes (Figure 1). For nad5, the five exons of nad5 separated across three chromosomes, with exon1 and exon2 in Chr8, exon3 in Chr12, and exon4 and exon5 in Chr1 (Figure 1).

The tRNAs of P. micranthum came from different origins, including twelve native mitochondrial-origin tRNAs (trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA-mt, trnfM-CAU, trnI-CAU×2, trnK-UUU, trnM-CAU-mt, trnP-UGG×2, trnQ-UUG, trnS-UGA, and trnY-GUA), three plastid-origin tRNAs (trnF-GAA-cp, trnM-CAU-cp, and trnN-GUU), and one bacteria-origin tRNAs (trnC-GCA) [42]. The plastome-originating tRNA, trnF-GAA-cp, had been reported before in angiosperm mitogenomes [42]. Notably, the mitogenome encoded both trnF-GAA-mt (74 bp) and trnM-CAU-mt (73 bp) from the mitochondrial origin, and trnF-GAA-cp (73 bp) and trnM-CAU-cp (73 bp) from the plastome origin. trnI-CAU and trnP-UGG had duplicated copies in the mitogenome and trnI-CAU duplicated in different chromosomes (Chr3 and Chr21), whereas trnP-UGG dispersed duplicated in Chr5 (Figure 1). In addition, Chr5 retained a truncated remnant of the plastome-origin trnV-UAC (Figure 1). However, some ancient plastome-to-mitogenome tRNAs (e.g., trnH-GUG and trnW-CCA) that appear in most sequenced angiosperm mitogenomes were not detected, which revealed that the mitogenome of P. micranthum experienced gene loss and gain.

Further, gene synteny analyses indicated that the mitogenome of P. micranthum retained eight of the 14 ancestral gene clusters reported across angiosperms [23], including atp4-nad4L, rpl2-rps19-rps3-rpl16, rpl5-rps14-cob, rps13-nad1.x2.x3, rrnS-rrn5, trnfM(CAU)-rrnL, trnF(GAA)-trnP(UGG), and trnY(GUA)-nad2.x3.x4.x5.

2.2. Horizontal Gene Transfer or the Intracellular Gene Transfer in the Mitogenome of P. micranthum

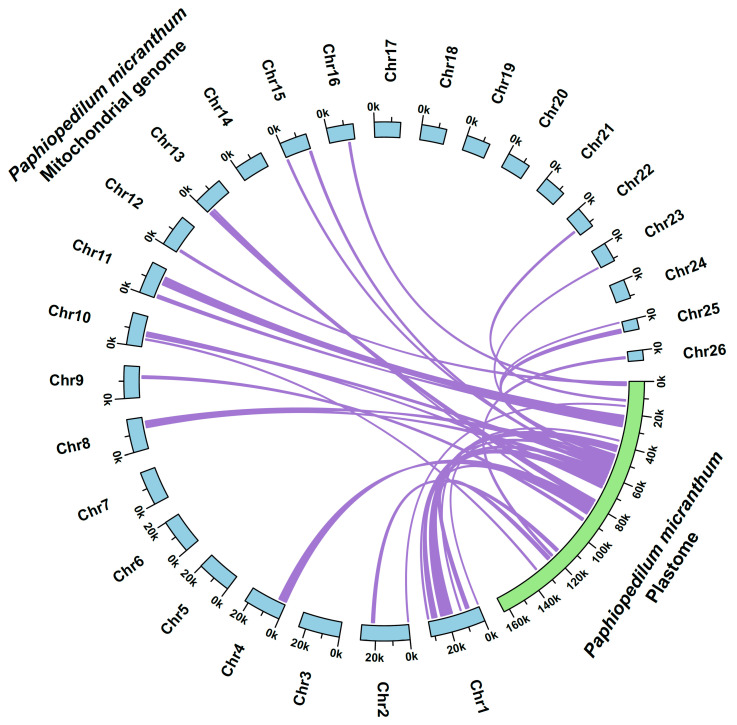

A total of 15 of the 26 chromosomes in the mitogenome of P. micranthum contained plastome-origin sequences, encoding 12 intact protein-coding genes, 3 tRNAs, and 29 pseudogenes (Table 2 and Table 3). All of these genes were identified by the plastome of P. micranthum, except for ψndhE, ψndhF, and ψndhH, which were identified by the plastome of Cypripedium tibeticum. However, the 270 bp fungal mitogenomic region identified by Sinn and Barrett [31] was not detected in the mitogenome of P. micranthum. The 25 plastome-derived fragments ranged from 165 bp to 7269 bp, with a total size of 46,273 bp, accounting for 10.34% of the whole mitogenome length and 28.32% of the P. micranthum plastome (Figure 3, Table 3). Even the smallest chromosome (Chr26—5973 bp) contained a 903 bp plastome-derived sequence. Most of the plastome-derived sequences showed high similarity to their conspecific plastome sequence (ranging from 84.2% to 99.6%) (Table 3), and 12 of the plastome origin genes were intact and potentially functional, including ycf4, cemA, petA, and a shortened rbcL (1047 bp) in Chr1; rpoA and rpl36 in Chr4; ndhJ in Chr8; psbE, psbF, psbJ, and psbL in Chr10; and a shortened atpE (345 bp) in Chr15 (Table 2 and Table 3). Particularly, psbE, psbF, and trnM-CAU-cp retained an identical copy with the plastome sequence of P. micranthum. However, other plastome-derived genes appeared as pseudogenes, e.g., ψndhD, ψpsaA, ψpsaC, and ψrpl14 in Chr1; and ψatpI, ψndhE, ψndhF, and ψycf1 in Chr2 (Table 2 and Table 3). Further, the chromosomes with plastome-origin fragments (40.4% to 46.3%) had lower GC content compared to chromosomes without plastome-origin sequences (41.2% to 49.2%), e.g., the GC content of Chr17 was 49.2%, while the GC content of Chr25 was 40.4% (Table 2).

Table 3.

Plastid-derived regions in the mitochondrial genome of Paphiopedilum micranthum.

| Chromosome | Length (bp) | Position | Genes Contained | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | 1862 | 6022–7883 | ψpsaC–ψndhD | 95.50 |

| Chr1 | 256 | 11,166–11,421 | none | 99.60 |

| Chr1 | 7269 | 16,713–23,981 | petA–cemA–ycf4–ψpsaA | 95.90 |

| Chr1 | 1024 | 26,693–27,716 | ψrpl14–ψrpl16 | 88.50 |

| Chr1 | 1549 | 28,034–29,582 | rbcL | 95.20 |

| Chr1 | 426 | (31,892–32,281) + (1–36) | trnF(GAA) | 85.20 |

| Chr2 | 165 | 5–169 | none | 94.80 |

| Chr2 | 1357 | 19,699–21,055 | ψndhE fragment–ψndhF fragment | 93.00 |

| Chr2 | 1583 | 21,146–22,728 | ψycf1 fragment–trnN(GUU) | 91.50 |

| Chr4 | 4719 | 157–4875 | ψpetB fragment–ψpetD fragment–rpoA–ψrps11–rpl36–ψinfA | 92.30 |

| Chr8 | 3976 | 12,854–16,829 | ψaccD–ndhJ–ψndhK–ψndhC | 93.80 |

| Chr9 | 1320 | 11,951–13,270 | ψrpl2 | 96.40 |

| Chr10 | 415 | 4673–5087 | none | 90.90 |

| Chr10 | 4310 | 5152–9461 | ψndhH–ψatpB–psbJ–psbL–psbF–psbE | 93.60 |

| Chr11 | 1749 | 566–2314 | ψrpoB fragment | 87.40 |

| Chr11 | 4823 | 9374–14,196 | ψrpoB fragment–ψrpoC1 | 92.60 |

| Chr12 | 947 | 1515–2461 | ψpsbA fragment | 92.20 |

| Chr13 | 2179 | 400–2578 | ψpsbN–ψpsbH–ψpetB fragment–ψpsbB fragment | 92.50 |

| Chr13 | 230 | 3792–4021 | ψrps8 fragment | 88.30 |

| Chr15 | 1552 | (14,959–15,892) + (1–618) | atpE–trnM(CAU)–ψtrnV(UAC) fragment | 90.90 |

| Chr16 | 729 | 11,631–12,359 | ψmatK fragment | 84.20 |

| Chr22 | 587 | 8861–9447 | ψatpA fragment | 88.30 |

| Chr23 | 203 | 10,708–10,910 | none | 85.80 |

| Chr25 | 2140 | (4328–6393) + (1–74) | ψrps4 | 84.20 |

| Chr26 | 903 | 3032–3934 | ψycf1 fragment | 89.40 |

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of gene transfer between the plastome and mitogenome of Paphiopedilum micranthum.

2.3. Repeat Sequences in the Mitogenome of P. micranthum

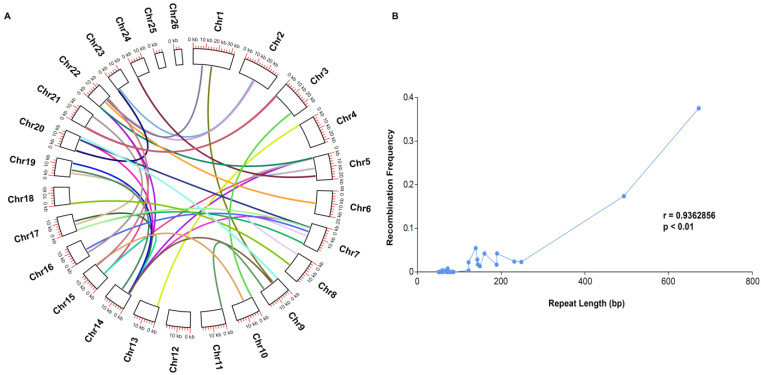

Overall, 27 tandem repeats, with lengths ranging from 27 bp to 308 bp, accounted for 1948 bp of the P. micranthum mitogenome; these repeats resided in the non-coding regions of the genome, except for a 48 bp repeat in rrn26, and some of the tandem repeats overlapped with the dispersed repeats. The mitogenome of P. micranthum possessed 89 dispersed repeats (34 types), ranging from 51 bp to 672 bp, with two to four copies and covering 9996 bp (2%) of the genome. The majority of these repeats (87 of 89, 97.7%) were intermediate-sized repeats (50 to 500 bp) and two repeats (672 bp) were large repeats (>500 bp) (Table S5), with most of these repeats residing in the noncoding regions. These repeats were distributed in 23 of the 26 chromosomes; Chr12, Chr25, and Chr26 did not contain dispersed repeats (Figure 4A). We found 16 pairs of repeats involved in the recombination of the mitogenome structure. The alternative conformations were supported by the long reads, and repeat length was positively correlated with the recombination frequency (r = 0.9379, p < 0.001), e.g., the recombination frequency of the longest repeat (672 bp) was 0.38; 116 long reads supported the alternative conformations, and 193 long reads supported the master circle conformation, while homologous recombination occurred sporadically among repeats shorter than 300 bp (Figure 4B, Table S5).

Figure 4.

Recombination frequency in the mitogenome of Paphiopedilum micranthum. (A) The distribution of the 34 pairs of repeats; (B) recombination frequency of 34 pairs of repeats (>50 bp) with 100% identity.

3. Discussion

3.1. General Features of the P. micranthum Mitogenome

The mitogenome of P. micranthum was conserved in gene number and gene content compared to other angiosperm mitogenomes, encoding for 39 of the 41 protein-coding genes present in the common ancestors of angiosperms [47]—except for sdh3 and rpl10, which were lost from the mitogenome of P. micranthum (Figure 2). Sdh3 and sdh4 encoded succinate dehydrogenase, and the two genes had been lost repeatedly in the mitogenomes of angiosperm [39]. While, in many other angiosperm lineages, both sdh3 and sdh4 are lost from the mitogenome, sdh4 was retained in the P. micranthum mitogenome. Notably, the sdh4 in P. micranthum contracted to 204 bp; the contraction of sdh4 was also observed in coconut palm (183 bp) [48], and we annotated a 222 bp of sdh4 in Asparagus officinalis (MT483994). Rpl10 has frequently been reported as lost in angiosperms [24] and pseudogenized or lost in sequenced monocots [49].

The mitogenome of P. micranthum and G. elata shared 18% (about 81 kb) of their mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences, including 37 protein-coding genes (33, 817 bp), and 47, 121 bp non-coding regions (Figure 5). The amount of shared mtDNA was relatively small compared to most other pairs of species in seed plants [50,51]. Compared to the mitogenome of G. elata, the gene content of the two species was quite similar, and even the length of the cis-splicing introns was similar (Table S4). The GC content of the 26 chromosomes of P. micranthum was more variable compared to the 19 chromosomes of G. elata. Owing to active recombination, the ancestral gene clusters conserved across angiosperms were lost in P. micranthum; only 8 of the 14 gene clusters conserved across angiosperms were preserved. Even the two gene clusters, nad9-trnY(GUA) and trnI(CAU)-trnD(GUC), restricted to monocots, broke in the P. micranthum mitogenome. Further, there were eight gene clusters shared between the mitogenome of P. micranthum and G. elata, including atp4-ndh4L, rpl2-rps19-rps3-rpl16, rpl5-rps14-cob, rps13-nad1.x2.x3, trnY(GUA)-nad2.x3.x4.x5, matR-nad1.x1, atp1-ccmFn, and apt9-rps7; the first five of them were conserved in most angiosperms, the other three were newly formed, and atp1-ccmFn was restricted to Orchidaceae.

Figure 5.

The colinear analysis of the mitogenome of Paphiopedilum micranthum and Gastrodia elata.

Five of the six trans-splicing introns (nad1i394, nad1i669, nad2i542, nad5i1455, and nad5i1477) were shared with the common ancestors of seed plants [24]. The trans-splicing of nad1i728 (the fourth intron) was sporadically distributed among angiosperms [24,52], and most of the species sequenced in monocots presented trans-splicing of this intron, e.g., Allium cepa [53] and A. officinalis [54], which indicates rampant recombination in the mitogenome evolution. In the P. micranthum mitogenome, the trans-splicing of nad1i728 was owed to the chromosome fragmentation, and exon4 and exon5 of nad1 were located in Chr7 and Chr5, respectively. Guo et al. [52] indicated that cis- shift to trans-splicing correlated with the rearrangement in the seed plants. The intrachromosomal trans-splicing to interchromosomal trans-splicing also indicates active recombination in the mitogenome.

3.2. Rampant Plastome Origin Sequences in the Mitogenome of P. micranthum

The plastome origin sequences accounted for 0.1% to 10.3% of the mitochondrial genome [47,55]. For instance, the plastome-derived sequence accounted for 1.98% (11,281 bp) in Hibiscus cannabinus [56], 1.16% (8937 bp) to 4.05% (37,483 bp) in kiwifruit [57], 6% (23 kb) in Citrullus lanatus [58], and 8.8% in vitis [59]. Further, the plastome-obtained sequences covered less than 5% of most angiosperm mitogenomes [55]. In contrast, 15 of the 26 chromosomes in the P. micranthum mitogenome contained plastome-derived fragments, covering 10.34% (~46 kb) of the P. micranthum mitogenome (Figure 3, Table 3). Compared to most other reported plastome-derived mitogenome fragments [44,60,61], the plastome-derived sequences in the mitogenome of P. micranthum were more pervasive and widespread, both in relative and absolute terms. The plastome-derived sequences in Chr1 even reached 12 kb (38% of Chr1) (Table 3). More than half (27,420 bp, 59%) of the plastome-origin mitogenome sequences were identical to the plastome of P. micranthum, with a range in size from 50 to 676 bp (Table 3). These properties suggest that the plastome-derived sequences stem from multiple transfer events, and following their intracellular transfer, these sequences experience multi-rounds of recombination.

Interestingly, ndh genes experienced different extents of degradation in the plastome of Paphiopedilum, and ndhE, ndhF, and ndhH have been lost from the plastome of P. micranthum [62]. However, the pseudo copies of ψndhE, ψndhF, and ψndhH were detected in P. micranthum mitogenome (Figure 1, Table 2 and Table 3). Additionally, ndhJ was reported as a pseudogene in the plastome of P. micranthum owing to the non-triplet, insertion-induced, premature-stop codons [62], whereas the mitogenome of P. micranthum encoded the potential functional copy of ndhJ. These data suggest that the transfer events of ndh genes predated the degradation of ndh in the P. micranthum plastome, or there was more than one donor of their plastome origin sequences. Furthermore, most of the plastome origin genes have been nonfunctional pseudogenes in previous studies [3,4,40,42], except for a few cases—for instance, psaA, ndhB, and rps7 in H. cannabinus [56] and petN, psaA, atpI, trnI-CAU, and trnC-GCA in Mangifera [63]. The mitogenome of P. micranthum contained 44 genes from plastid origin, and 12 of these genes are intact and potentially functional (ycf4, cemA, petA, rbcL, rpoA, rpl36, ndhJ, psbE, psbF, psbJ, psbL, and atpE), which has been rather rare in previous studies (Table 2 and Table 3).

3.3. The Multichromosomal Mitogenome Structure of P. micranthum

The mitogenome of P. micranthum fragmented into 26 minicircular genomes (5973 bp to 32,281 bp). The mitogenome size of other species with multichromosomal structures varied widely, from 66 kb in V. scurruloideum [8] to 11,318 kb in S. conica [9], and most of these angiosperm species had two to five contigs [17], except Cynomorium [64] Fagopyrum esculentum [65], G. elata [37], Geranium brycei [40], Lophophytum mirabile [16], Ombrophytum subterraneum [12], Rhopalocnemis phalloides [19], and Silene [9,66] (Table S6). Compared to most other species with multichromosomal structures, the mitogenome of P. micranthum showed a more compact and fragmented genome structure. Notably, the shortest mitogenome of P. micranthum was 5973 bp encoding atp8 and partially ψycf1; the size of the smallest chromosome was similar to the other species with multichromosomal structures, e.g., O. subterraneum (4900 bp) [12] and R. phalloides (4949 bp) [19]. The mitogenome fragmentation may facilitate the recombination between physically unlinked loci [66,67]. Further, 9 of the 26 chromosomes were autonomous chromosomes; these chromosomes did not contain repeats longer than 100 bp, and all the autonomous chromosomes in P. micranthum contained protein-coding genes, while the autonomous chromosomes in cucumber and Silene do not contain identifiable genes [9,15].

Repeat sequences are a source of constant rearrangement in the mitogenome [14,68,69,70]. Direct repeat-mediated recombination has been documented in previous studies, e.g., Brassica campestris [71] and Scutellaria tsinyunensis [27]. Li et al. [27] reported a pair of direct repeats (175 bp) mediated recombination in the mitogenome of S. tsinyunensis, and the 354,073 bp master circle was fragmented into two chromosomes with a length of 255,741 bp and 98,402 bp. According to the conventional multipartite model, large repeats in the master circle induced intragenomic recombination, resulting in a set of subgenomic circles [14]. Chr5 was fragmented into Chr5A and Chr5B due to a pair of 122 bp repeats (Figure S1). However, we did not detect the master circle that included the entire sequence of the P. micranthum mitogenome. Notably, P. micranthum had fewer repeat sequences, both in number and relative percentage compared to other monocot species tested [5]. Further, the number of repeat sequences (2%) was relatively less than most other species, e.g., Mangifera (3.5% to 4.5%) [63], Monsonia (3.9% to 6.9%) [68], Trifolium (6.6% to 8.6%) [72], and Silene vulgaris (18.8 to 28%) [69].

Long-read sequencing provided a reliable method to explore repeat-mediated homologous recombination. Though the mitogenome of P. micranthum does not contain repeats longer than 1 kb, we found alternative conformations that coexisted in the flanking regions of repeat sequences. Further, the repeat length was strongly correlated with the recombination frequency (r = 0.9379) (Figure 4, Table S5), which has also been identified in previous studies [8,9,73]. The mitogenome of P. micranthum was depicted as 26 minicircles for simplicity. In fact, long-read sequencing implied that the mitogenome of P. micranthum consisted of a population of alternative structures that resulted from dispersed repeats. Moreover, repeat sequences might play an important role in the mitogenome fragmentation of Orchidaceae.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

We collected two fresh leaf samples of P. micranthum from the National Orchid Conservation and Research Center of Shenzhen (NOCC). Total genomic DNA was extracted using the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method [74]. The extracted total genomic DNA was used for library construction with 350 bp and 20 kb insert sizes and then sequenced on MGI2000 (MGI, Shenzhen, China) and PacBio RS-II platforms (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) for short and long reads, respectively.

The long reads were error-corrected using Canu v2.0 [75]. Then, we used the mitogenome sequences, downloaded from GenBank, as reference sequences. The potential mitogenome long reads were filtered with BLASR v5.1 [76]; short reads were filtered with a perl script described in Wang, et al. [77], and the enriched reads were used for hybrid assembly in SPAdes v3.14.1 [78]. Mitogenome contigs were filtered using BLASTN [79] and used as reference sequences for further analysis. We repeated the above steps for multiple rounds in SPAdes to improve the assembly.

In parallel, we used the complete, uncorrected datasets to assemble the mitogenome with an unpublished hybrid assembly version of NOVOPlasty [80,81]. As a seed-and-extend assembler, it needs a mitochondrial seed to initiate the assembly. Since this mitogenome exists out of multiple circular genomes, we selected all the protein-coding genes shared among angiosperms as seed sequences. Furthermore, we used the mitochondrial contigs from the SPAdes assembly that were devoid of genes as additional seeds. The overlapped regions of the above-described methods are identical, and contigs obtained from SPAdes usually lost some parts of the circular genome. In addition, we mapped the long PacBio reads to these contigs to verify the results and we de novo assembled the lost genes (rpl10 and sdh3) with NOVOPlasty to confirm their absence.

The assembled contigs were annotated in Geneious Prime (Biomatters, Inc., Auckland, New Zealand) with L. tulipifera [23], G. elata [37], A. cepa [53], and A. officinalis as references [54], and refined manually. Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted and annotated using ORFfinder in Geneious Prime, starting with ATG and of length > 300 bp. tRNA genes were annotated using tRNAscan-SE v2.0 [82]. The obtained contigs were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers OP465200–OP465225 (Table 1). The genome maps were generated with OrganellarGenomeDRAW [83]. Additionally, we used PREPACT 3.12.0 [84] to predict RNA editing in three genes (atp6, atp9, and sdh4) reference to Amborella and Liriodendron.

4.2. Identification of Plastid-Derived Regions and Other Horizontally Derived Regions

Firstly, the mitogenome of P. micranthum was searched against the plastomes of P. micranthum (MN587791) [62] and C. tibeticum (MT937101) [85] to identify plastid-derived fragments with BLAST v2.11.0+ [79], using a word size of seven, an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−6, and a length > 100 bp. The paralogs in the mitogenomes and plastomes were excluded from the results (e.g., atp1/atpA, rrn26/rrn23, and rrn18/rrn16), following the procedures in Guo et al. [51]. Additionally, we compared the mitochondrial homologs with putative plastid regions to evaluate the mutations in the plastid-derived mitochondrial genes. Then, we use the mitogenome of Ustilago maydis as reference sequences to identify the horizontal gene transfer fragments mentioned in Sinn and Barrett [31].

4.3. Repeat and Repeats-Mediated Homologous Recombinations

Tandem repeats in the P. micranthum mitogenome were identified using Tandem Repeat Finder v4.09 [86] with default parameters. The dispersed repeats were detected using the python tool ROUSFinder.py [5] with a minimum repeat size of 50 bp. Then, we calculated the recombination frequency of 34 pairs of repeats with 100% identity, following the methods of Sullivan et al. [70]. For each repeat pair, we extracted ±2000 bp flanking regions and constructed two potentially alternative conformations. The recombination rate was calculated by dividing the number of recombinant reads by the total number of reads spanning each repeat. In addition, we tested whether the repeat length correlated with the recombination frequency.

5. Conclusions

We accurately assembled the mitogenome of P. micranthum with a combination of long- and short-read data. The mitogenome of P. micranthum presents typical multichromosomal structures and preserves a large amount of plastome-derived horizontal gene transfer fragments. Considering the genome size and chromosome number, the mitogenome of P. micranthum is more fragmented than most other species with multichromosomal genome structures. The long reads provide strong evidence for the plastome-to-mitogenome intracellular gene transfer and the repeat-mediated homologous recombination. The comparison of the P. micranthum mitogenome with the mitogenome of G. elata sheds light on the mitogenome evolution of Orchidaceae. Though the mitogenomes of the two species have similar gene content, the mitogenomes of the two species share only 81 kb of their mtDNA sequence. Considering the disparities in genome size and chromosome number, the high frequency of recombination, intraspecies genome structure variation, and the low collinearity of the two orchids, our understanding of the mitogenome evolution of orchids is rather limited. Further studies are needed to unravel the mitogenome evolution of orchids.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. The authors thank Guo-Qiang Zhang for help with sample collection and Fu-Chao Guo for help in the analysis of RNA editing.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms24043976/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-Y.G.; data curation, J.-X.Y. and Y.-Y.G.; formal analysis, J.-X.Y., N.D. and M.-Z.B.; funding acquisition, Y.-Y.G. and N.D.; methodology, Y.-Y.G.; resources, Y.-Y.G.; software, J.-X.Y. and N.D.; writing—original draft, J.-X.Y. and Y.-Y.G.; writing—review and editing, N.D. and Y.-Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The annotated mitogenomes generated in this study are deposited in GenBank under accession Nos. OP465200–OP465225.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number U1804117 to Y.-Y.G.) and KU Leuven (postdoctoral mandate PDMT1/21/033 to N.D.)

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Palmer J.D., Herbon L.A. Plant mitochondrial DNA evolved rapidly in structure, but slowly in sequence. J. Mol. Evol. 1988;28:87–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02143500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergthorsson U., Adams K., Thomason B., Palmer J. Widespread horizontal transfer of mitochondrial genes in flowering plants. Nature. 2003;424:197–201. doi: 10.1038/nature01743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice D.W., Alverson A.J., Richardson A.O., Young G.J., Sanchez-Puerta M.V., Munzinger J., Barry K., Boore J.L., Zhang Y., dePamphilis C.W., et al. Horizontal transfer of entire genomes via mitochondrial fusion in the angiosperm Amborella. Science. 2013;342:1468–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.1246275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mower J.P., Jain K., Hepburn N.J. The Role of Horizontal Transfer in Shaping the Plant Mitochondrial Genome. In: Maréchal-Drouard L., editor. Mitochondrial Genome Evolution. Volume 63. Academic Press; Berkeley, CA, USA: 2012. pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wynn E.L., Christensen A.C. Repeats of unusual size in plant mitochondrial genomes: Identification, incidence and evolution. G3-GENES GENOM GENET. 2019;9:549–559. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Small I.D., Schallenberg-Rüdinger M., Takenaka M., Mireau H., Ostersetzer-Biran O. Plant organellar RNA editing: What 30 years of research has revealed. Plant J. 2020;101:1040–1056. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knoop V. C-to-U and U-to-C: RNA editing in plant organelles and beyond. J. Exp. Bot. 2022:erac488. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skippington E., Barkman T.J., Rice D.W., Palmer J.D. Miniaturized mitogenome of the parasitic plant Viscum scurruloideum is extremely divergent and dynamic and has lost all nad genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E3515–E3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504491112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloan D.B., Alverson A.J., Chuckalovcak J.P., Wu M., McCauley D.E., Palmer J.D., Taylor D.R. Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backert S., Nielsen B.L., Börner T. The mystery of the rings: Structure and replication of mitochondrial genomes from higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:477–483. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01148-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozik A., Rowan B.A., Lavelle D., Berke L., Schranz M.E., Michelmore R.W., Christensen A.C. The alternative reality of plant mitochondrial DNA: One ring does not rule them all. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roulet M.E., Garcia L.E., Gandini C.L., Sato H., Ponce G., Sanchez-Puerta M.V. Multichromosomal structure and foreign tracts in the Ombrophytum subterraneum (Balanophoraceae) mitochondrial genome. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020;103:623–638. doi: 10.1007/s11103-020-01014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gualberto J.M., Newton K.J. Plant mitochondrial genomes: Dynamics and mechanisms of mutation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017;68:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloan D.B. One ring to rule them all? Genome sequencing provides new insights into the ‘master circle’ model of plant mitochondrial DNA structure. New Phytol. 2013;200:978–985. doi: 10.1111/nph.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alverson A.J., Rice D.W., Dickinson S.L., Barry K., Palmer J.D. Origins and recombination of the bacterial-sized multichromosomal mitochondrial genome of cucumber. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2499–2513. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.087189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Puerta M.V., García L.E., Wohlfeiler J., Ceriotti L.F. Unparalleled replacement of native mitochondrial genes by foreign homologs in a holoparasitic plant. New Phytol. 2017;214:376–387. doi: 10.1111/nph.14361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z.-Q., Liao X.-Z., Zhang X.-N., Tembrock L.R., Broz A. Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria—A review of multichromosomal structuring. J. Syst. Evol. 2022;60:160–168. doi: 10.1111/jse.12655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varré J.-S., D’Agostino N., Touzet P., Gallina S., Tamburino R., Cantarella C., Ubrig E., Cardi T., Drouard L., Gualberto J.M. Complete sequence, multichromosomal architecture and transcriptome analysis of the Solanum tuberosum mitochondrial genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:4788. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu R., Sun C., Zhong Y., Liu Y., Sanchez-Puerta M.V., Mower J.P., Zhou R. The minicircular and extremely heteroplasmic mitogenome of the holoparasitic plant Rhopalocnemis phalloides. Curr. Biol. 2022;32:470–479.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu A., Guo W., Jain K., Mower J.P. Unprecedented heterogeneity in the synonymous substitution rate within a plant genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014;31:1228–1236. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu F., Fan W., Yang J.-B., Xiang C.-L., Mower J.P., Li D.-Z., Zhu A. Episodic and guanine–cytosine-biased bursts of intragenomic and interspecific synonymous divergence in Ajugoideae (Lamiaceae) mitogenomes. New Phytol. 2020;228:1107–1114. doi: 10.1111/nph.16753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho Y., Mower J.P., Qiu Y.L., Palmer J.D. Mitochondrial substitution rates are extraordinarily elevated and variable in a genus of flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:17741–17746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408302101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson A.O., Rice D.W., Young G.J., Alverson A.J., Palmer J.D. The “fossilized” mitochondrial genome of Liriodendron tulipifera: Ancestral gene content and order, ancestral editing sites, and extraordinarily low mutation rate. BMC Biol. 2013;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mower J.P. Variation in protein gene and intron content among land plant mitogenomes. Mitochondrion. 2020;53:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong S., Zhao C., Chen F., Liu Y., Zhang S., Wu H., Zhang L., Liu Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of the early flowering plant Nymphaea colorata is highly repetitive with low recombination. BMC Genom. 2018;19:614. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4991-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H., Yu J., Yu X., Zhang D., Chang H., Li W., Song H., Cui Z., Wang P., Luo Y., et al. Structural variation of mitochondrial genomes sheds light on evolutionary history of soybeans. Plant J. 2021;108:1456–1472. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Xu Y., Shan Y., Pei X., Yong S., Liu C., Yu J. Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of an endemic plant, Scutellaria tsinyunensis, revealed the existence of two conformations generated by a repeat-mediated recombination. Planta. 2021;254:36. doi: 10.1007/s00425-021-03684-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J., Cullis C. The multipartite mitochondrial genome of marama (Tylosema esculentum) Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:787443. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.787443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong S., Zhao C., Zhang S., Zhang L., Wu H., Liu H., Zhu R., Jia Y., Goffinet B., Liu Y. Mitochondrial genomes of the early land plant lineage liverworts (Marchantiophyta): Conserved genome structure, and ongoing low frequency recombination. BMC Genom. 2019;20:953. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6365-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang J.S., Zhang H.R., Wang Y.R., Liang S.Q., Mao Z.Y., Zhang X.C., Xiang Q.P. Distinctive evolutionary pattern of organelle genomes linked to the nuclear genome in Selaginellaceae. Plant J. 2020;104:1657–1672. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinn B.T., Barrett C.F. Ancient mitochondrial gene transfer between fungi and the orchids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:44–57. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinkar L., Gasser R.B., Webster B.L., Rollinson D., Littlewood D.T.J., Chang B.C., Stroehlein A.J., Korhonen P.K., Young N.D. Nanopore sequencing resolves elusive long tandem-repeat regions in mitochondrial genomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:1811. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Achakkagari S.R., Tai H.H., Davidson C., De Jong H., Strömvik M.V. The complete mitogenome assemblies of 10 diploid potato clones reveal recombination and overlapping variants. DNA Res. 2021;28:dsab009. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsab009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sathiyadash K., Muthukumar T., Karthikeyan V., Rajendran K. Orchid Mycorrhizal Fungi: Structure, Function, and Diversity. In: Khasim S., Hegde S., González-Arnao M., Thammasiri K., editors. Orchid Biology: Recent Trends & Challenges. Springer; Singapore: 2020. pp. 239–280. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasmussen H.N. Terrestrial orchids: From Seed to Mycotrophic Plant. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacquemyn H., Merckx V.S. Mycorrhizal symbioses and the evolution of trophic modes in plants. J. Ecol. 2019;107:1567–1581. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan Y., Jin X., Liu J., Zhao X., Zhou J., Wang X., Wang D., Lai C., Xu W., Huang J. The Gastrodia elata genome provides insights into plant adaptation to heterotrophy. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1615. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao N., Wang Y., Hua J. The roles of mitochondrion in intergenomic gene transfer in plants: A source and a pool. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:547. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams K.L., Qiu Y.L., Stoutemyer M., Palmer J.D. Punctuated evolution of mitochondrial gene content: High and variable rates of mitochondrial gene loss and transfer to the nucleus during angiosperm evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9905–9912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042694899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S., Grewe F., Zhu A., Ruhlman T.A., Sabir J., Mower J.P., Jansen R.K. Dynamic evolution of Geranium mitochondrial genomes through multiple horizontal and intracellular gene transfers. New Phytol. 2015;208:570–583. doi: 10.1111/nph.13467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi I.-S., Wojciechowski M.F., Ruhlman T.A., Jansen R.K. In and out: Evolution of viral sequences in the mitochondrial genomes of legumes (Fabaceae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021;163:107236. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren J.M., Sloan D.B. Interchangeable parts: The evolutionarily dynamic tRNA population in plant mitochondria. Mitochondrion. 2020;52:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia L.E., Edera A.A., Palmer J.D., Sato H., Sanchez-Puerta M.V. Horizontal gene transfers dominate the functional mitochondrial gene space of a holoparasitic plant. New Phytol. 2021;229:1701–1714. doi: 10.1111/nph.16926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi K.-S., Park S. Complete plastid and mitochondrial genomes of Aeginetia indica reveal Intracellular Gene Transfer (IGT), Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT), and Cytoplasmic Male Sterility (CMS) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6143. doi: 10.3390/ijms22116143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mower J.P., Stefanovi S., Hao W., Gummow J.S., Jain K., Ahmed D., Palmer J.D. Horizontal acquisition of multiple mitochondrial genes from a parasitic plant followed by gene conversion with host mitochondrial genes. BMC Biol. 2010;8:150. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Z., Chen S., Chen L., Lei S. The Genus Paphiopedilum in China. Science Press; Beijing, China: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mower J.P., Sloan D.B., Alverson A.J. Plant Mitochondrial Genome Diversity: The Genomics Revolution. In: Wendel J.F., Greilhuber J., Dolezel J., Leitch I.J., editors. Plant Genome Diversity Volume 1: Plant Genomes, Their Residents, and Their Evolutionary Dynamics. Springer; Vienna, Austria: 2012. pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aljohi H.A., Liu W., Lin Q., Zhao Y., Zeng J., Alamer A., Alanazi I.O., Alawad A.O., Al-Sadi A.M., Hu S. Complete sequence and analysis of coconut palm (Cocos nucifera) mitochondrial genome. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mower J.P., Bonen L. Ribosomal protein L10 is encoded in the mitochondrial genome of many land plants and green algae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009;9:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Y., Liu Y., Zhang S., Zou R., Tang J., Mu W., Peng Y., Dong S. Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Sophora japonica ‘JinhuaiJ2’. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0202485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo W., Grewe F., Fan W., Young G.J., Knoop V., Palmer J.D., Mower J.P. Ginkgo and Welwitschia mitogenomes reveal extreme contrasts in gymnosperm mitochondrial evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1448–1460. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo W., Zhu A., Fan W., Adams R.P., Mower J.P. Extensive shifts from cis-to trans-splicing of gymnosperm mitochondrial introns. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:1615–1620. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim B., Kim K., Yang T.-J., Kim S. Completion of the mitochondrial genome sequence of onion (Allium cepa L.) containing the CMS-S male-sterile cytoplasm and identification of an independent event of the ccmFN gene split. Curr. Genet. 2016;62:873–885. doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheng W. The complete mitochondrial genome of Asparagus officinalis L. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020;5:2627–2628. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1780986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sloan D.B., Wu Z. History of plastid DNA insertions reveals weak deletion and AT mutation biases in angiosperm mitochondrial genomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014;6:3210–3221. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liao X., Zhao Y., Kong X., Khan A., Zhou B., Liu D., Kashif M.H., Chen P., Wang H., Zhou R. Complete sequence of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) mitochondrial genome and comparative analysis with the mitochondrial genomes of other plants. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12714. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30297-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang S., Li D., Yao X., Song Q., Wang Z., Zhang Q., Zhong C., Liu Y., Huang H. Evolution and diversification of kiwifruit mitogenomes through extensive whole-genome rearrangement and mosaic loss of intergenic sequences in a highly variable region. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019;11:1192–1206. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alverson A.J., Wei X.X., Rice D.W., Stern D.B., Barry K., Palmer J.D. Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae) Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:1436–1448. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goremykin V.V., Salamini F., Velasco R., Viola R. Mitochondrial DNA of Vitis vinifera and the issue of rampant horizontal gene transfer. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:99–110. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gandini C., Sanchez-Puerta M. Foreign plastid sequences in plant mitochondria are frequently acquired via mitochondrion-to-mitochondrion horizontal transfer. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43402. doi: 10.1038/srep43402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fang Y., Wu H., Zhang T., Yang M., Yin Y., Pan L., Yu X., Zhang X., Hu S., Al-Mssallem I.S. A complete sequence and transcriptomic analyses of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) mitochondrial genome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo Y.-Y., Yang J.-X., Bai M.-Z., Zhang G.-Q., Liu Z.-J. The chloroplast genome evolution of Venus slipper (Paphiopedilum): IR expansion, SSC contraction, and highly rearranged SSC regions. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21:248. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03053-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Niu Y., Gao C., Liu J. Complete mitochondrial genomes of three Mangifera species, their genomic structure and gene transfer from chloroplast genomes. BMC Genom. 2022;23:147. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08383-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bellot S., Cusimano N., Luo S., Sun G., Zarre S., Gröger A., Temsch E., Renner S.S. Assembled plastid and mitochondrial genomes, as well as nuclear genes, place the parasite family Cynomoriaceae in the Saxifragales. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8:2214–2230. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Logacheva M.D., Schelkunov M.I., Fesenko A.N., Kasianov A.S., Penin A.A. Mitochondrial genome of Fagopyrum esculentum and the genetic diversity of extranuclear genomes in buckwheat. Plants. 2020;9:618. doi: 10.3390/plants9050618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu Z., Cuthbert J.M., Taylor D.R., Sloan D.B. The massive mitochondrial genome of the angiosperm Silene noctiflora is evolving by gain or loss of entire chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10185–10191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421397112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rand D.M. ‘Why genomes in pieces?’ revisited: Sucking lice do their own thing in mtDNA circle game. Genome Res. 2009;19:700–702. doi: 10.1101/gr.091132.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cole L.W., Guo W., Mower J.P., Palmer J.D. High and variable rates of repeat-mediated mitochondrial genome rearrangement in a genus of plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:2773–2785. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sloan D.B., Muller K., Mccauley D.E., Taylor D.R., Storchova H. Intraspecific variation in mitochondrial genome sequence, structure, and gene content in Silene vulgaris, an angiosperm with pervasive cytoplasmic male sterility. New Phytol. 2012;196:1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sullivan A.R., Eldfjell Y., Schiffthaler B., Delhomme N., Asp T., Hebelstrup K.H., Keech O., Öberg L., Møller I.M., Arvestad L. The mitogenome of Norway spruce and a reappraisal of mitochondrial recombination in plants. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020;12:3586–3598. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palmer J.D., Shields C.R. Tripartite structure of the Brassica campestris mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1984;307:437–440. doi: 10.1038/307437a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi I.-S., Ruhlman T.A., Jansen R.K. Comparative mitogenome analysis of the genus Trifolium reveals independent gene fission of ccmFn and intracellular gene transfers in Fabaceae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1959. doi: 10.3390/ijms21061959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dong S., Chen L., Liu Y., Wang Y., Zhang S., Yang L., Lang X., Zhang S. The draft mitochondrial genome of Magnolia biondii and mitochondrial phylogenomics of angiosperms. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0231020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doyle J., Doyle J. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koren S., Walenz B.P., Berlin K., Miller J.R., Bergman N.H., Phillippy A.M. Canu: Scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chaisson M.J., Tesler G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with successive refinement (BLASR): Application and theory. BMC Bioinform. 2012;13:238. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang W., Schalamun M., Morales-Suarez A., Kainer D., Schwessinger B., Lanfear R. Assembly of chloroplast genomes with long- and short-read data: A comparison of approaches using Eucalyptus pauciflora as a test case. BMC Genom. 2018;19:977. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dierckxsens N., Mardulyn P., Smits G. Unraveling heteroplasmy patterns with NOVOPlasty. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2020;2:lqz011. doi: 10.1093/nargab/lqz011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dierckxsens N., Mardulyn P., Smits G. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chan P.P., Lin B.Y., Mak A.J., Lowe T.M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: Improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:9077–9096. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Greiner S., Lehwark P., Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3. 1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lenz H., Hein A., Knoop V. Plant organelle RNA editing and its specificity factors: Enhancements of analyses and new database features in PREPACT 3.0. BMC Bioinform. 2018;19:255. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo Y.-Y., Yang J.-X., Li H.-K., Zhao H.-S. Chloroplast genomes of two species of Cypripedium: Expanded genome size and proliferation of AT-biased repeat sequences. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:609729. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.609729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The annotated mitogenomes generated in this study are deposited in GenBank under accession Nos. OP465200–OP465225.