Abstract

In Escherichia coli expression of the genes of fatty acid degradation (fad) is negatively regulated at the transcriptional level by FadR protein. In contrast the unsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic gene, fabA, is positively regulated by FadR. We report that fabB, a second unsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic gene, is also positively regulated by FadR. Genomic array studies that compared global transcriptional differences between wild-type and fadR-null mutant strains, as well as in cultures of each strain grown in the presence of exogenous oleic acid, indicated that expression of fabB was regulated in a manner very similar to that of fabA expression. A series of genetic and biochemical tests confirmed these observations. Strains containing both fabB and fadR mutant alleles were constructed and shown to exhibit synthetic lethal phenotypes, similar to those observed in fabA fadR mutants. A fadR strain was hypersensitive to cerulenin, an antibiotic that at low concentrations specifically targets the FabB protein. A transcriptional fusion of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) to the fabB promoter produces lower levels of CAT protein in a strain lacking functional FadR. The ability of a putative FadR binding site within the fabB promoter to form a complex with purified FadR protein was determined by a gel mobility shift assay. These experiments demonstrate that expression of fabB is positively regulated by FadR.

Bacteria regulate membrane fluidity by manipulating the relative levels of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids within the phospholipids of their membrane bilayers (1, 13). There are eight known genes (fab) involved in fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli (reviewed in references 8 and 34). Of these, only fabA and fabB are specifically required for the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (4, 5, 12, 46). Likewise, there are at least five separate gene products involved in the degradation of long-chain fatty acids to acetyl coenzyme A (for a review, see reference 34). The FadR regulatory protein negatively controls expression of the genes of the fatty acid degradation pathway (33, 40) and also functions as a positive regulator of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (19, 29, 30, 38).

Only two unique biochemical reactions are required to specifically produce unsaturated fatty acids in the overall course of fatty acid biosynthesis in E. coli (4, 5, 12, 46). When the growing acyl chain coupled to acyl carrier protein (ACP) reaches the 3-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP stage, either of two enzymes can carry out the dehydration reaction to produce trans-2-decenoyl-ACP. In vitro, the 3-ketoacyl-ACP dehydratases, FabZ and FabA, both have broad and overlapping ranges of substrate chain length specificity (28). In vivo, FabZ is involved in the dehydration of all chain lengths of 3-hydroxyacyl-ACPs and seems especially important in lipid A biosynthesis (36). Genetic data argue that the activity of FabA in vivo is restricted to 10 carbon substrates. The enzyme not only catalyzes the dehydration of 3-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP but also isomerizes the trans-2-enoyl bond of the ACP-bound substrate to the cis-3 isomer (3, 28). This isomerization places the nascent acyl chain in the unsaturated fatty acid synthetic pathway. The 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase I (FabB) enzyme appears to be required for elongation of the cis-3 decenoyl-ACP produced by FabA and is known to be the primary factor in determining cellular unsaturated fatty acid content (10). The Claissen-type condensation of malonyl-ACP with cis-3 decenoyl-ACP catalyzed by FabB produces cis-5-ene-3-ketododecenoyl-ACP, which is competent to undergo all the subsequent reactions typical of fatty acid biosynthesis. Ultimately this results in production of cis-9 hexadecenoyl and cis-11 octadecenoyl chains, which are incorporated into phospholipid (34).

The regulation of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis is complex. The fabA gene is known to have a strong promoter that is positively regulated by FadR (19, 29, 30) as well as a weaker constitutive promoter. The reasons why a regulatory factor for fatty acid degradation is involved in regulating unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis remain obscure. A model advanced by Cronan and Subrahmanyam (15) addresses the issue of why it seems advantageous to have two promoters for fabA but fails to answer the question of why FadR regulates fabA per se. DiRusso and Nyström (21) have postulated that FadR interacts with a number of other regulatory activities to coordinate lipid biosynthesis and degradation in response to stress and aging. While this seems an attractive proposal, it still begs the question of why the synthesis of unsaturated acids in particular, as opposed to that of saturated fatty acids, is regulated by FadR. Experimental evidence that both genes involved in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis are regulated similarly would discount the possibility that FadR regulation of fabA is merely fortuitous or vestigial in nature. Computer-assisted searches for consensus FadR recognition sites within the E. coli genome identify fabB as a potential target of FadR regulation (45). It should be noted that although several reviews state that fabB is positively regulated by FadR, neither these reports (2, 18, 21) nor the specific reference cited therein (19) contains data supporting this claim. We report several different lines of evidence showing that FadR positively regulates fabB transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Unless otherwise indicated, strains were obtained from local laboratory stocks or from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (CGSC) (Yale University, New Haven, Conn.). Phage transductions and other basic genetic techniques were generally carried out as previously described in reference 53. Strain CAG18497 is from the ordered Tn10 collection of Singer and coworkers (48). Strains JWC264, JWC286, and JWC287 were made by P1vir transduction of the fadR613::Tn10 allele of CAG18497 into strains MG1655, M8, and M5, respectively. Strain JWC264 was selected on rich broth plates containing tetracycline at 37°C. Strain JWC276 is a fabB::CAT (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) transcriptional fusion in the strain MG1655 background containing a wild-type copy of the fabB gene expressed from the araBAD promoter of plasmid pARA14 (7). Strain JWC277 was made by transduction of fadR613::Tn10 from strain CAG18497 into strain JWC276 and selecting for tetracycline resistance at 30°C on rich broth plates supplemented with 0.01% oleate.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 | rph-1 fnr(?) | 56 |

| CAG18497 | fadR613::Tn10 rph-1 | 56 |

| M5 | serU84 fabB15(Ts) | 4 |

| M8 | serU84 fabA18(Ts) | 4 |

| JWC264 | fadR613::Tn10 rph-1 fnr(?) | This work |

| JWC286 | serU84 fabA18(Ts) fadR613::Tn10 | This work |

| JWC287 | serU84 fabB15(Ts) fadR613::Tn10 | This work |

| JWC288 | pRC1/rph-1 fnr(?) | This work |

| JWC289 | pRC1/fadR613::Tn10 rph-1 fnr(?) | This work |

| JWC276 | pARAfabB/rph-1 fnr(?) fabB::CAT | This work |

| JWC277 | pARAfabB/rph-1 fnr(?) fabB::CAT fabR613::Tn10 | This work |

Plasmid pRC1 carries a 4-kb fragment isolated from chromosomal E. coli DNA that includes intact fabA (20). Plasmid pARAfabB was made by PCR amplification of the fabB gene from MG1655 chromosomal DNA, followed by ligation of the fragment into pARA14 (7). The amplification reactions used a 5′ primer with the sequence 5′-CATTCGGATCCTTACTCTAT-GTGCG-3′ and a 3′ primer with the sequence 5′-GCCTGGATCCCCTTACCCGACC-3′. The unique 1.3-kb product was purified using a Qiagen (Valencia, Calif.) desalting column and digested with BamHI. Approximately 1 μg of plasmid pARA14 DNA was digested with BglII, treated with alkaline phosphatase, and ligated to the fabB PCR product. These reaction mixtures were then digested with BglII and transformed into strain DH5α (51). All enzymes and buffers were from Gibco-BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Recombinants were recovered on rich media containing 25 μg of a combination of clavulanate potassium and ticarcillin disodium (CPTD) (Timentin; SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pa.) per ml. Plasmid DNA was recovered from CPTD-resistant colonies and screened by restriction digestions for the presence of the fabB gene. Several constructs were transformed into M5, and the abilities of the recombinant strains to grow at 42°C in the presence of arabinose were examined. A plasmid capable of supporting growth at 42°C was retained as pARAfabB.

The fabB::CAT fusion strains were made by a modification of the λ Red-mediated recombination method of Datsenko and Wanner (16). A primer having 41 bases of homology to the start codon region of fabB at its 5′ end was synthesized. This primer also included an 11-base sequence containing translation stops (TAA) in all three reading frames immediately downstream of the fabB homologous sequence, followed by 27 bases of homology to the beginning of the CAT gene of plasmid pKD3 (23). The sequence of this primer was 5′-GAATGAAACGTGCAGTGATTACTGGCCTGGGCATTGTTTCCTAACTAACTAATCAGGAGCTAAGGAAGCTAAAATGGAG-3′. A second primer included 41 bases of homology to the reverse complement of the stop codon region of fabB at the 5′ end, and 25 bases of homology to the P1 site of pKD3 on the 3′ end. The sequence of this primer was 5′-GAATTAATCTTTCAGCT TGCGCATTACCAGCGTGGCGTTG-GTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC GAAG-3′. These primers were used to amplify the cat gene of plasmid pKD3 in a standard PCR. The enzyme and buffers in these reactions were from Gibco-BRL. The purified 1.5-kb PCR product was transformed into strain BW25113 (16), and the cells were plated onto rich broth agar containing chloramphenicol and supplemented with 0.01% oleate. Chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were isolated, and phage P1vir was grown on 10 ml cultures of these strains. The resulting lysates were used to transduce MG1655 to chloramphenicol resistance. The resulting strain, JWC276, contains the CAT gene, including its ribosome-binding site, downstream of 3 translational stop codons, which are located 12 codons upstream from the normal fabB start. In this strain, CAT is expressed from the fabB promoter. Strain JWC277 was made by transducing the fadR613::Tn10 insertion of CAG18497 into JWC276 and selecting for tetracycline resistance on rich-broth plates containing 0.01% oleate at 30°C.

Microbial methods.

Rich broth contained 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of NaCl and 1 g of yeast extract per liter. Minimal medium was M9 (44). Glucose was added to 0.2%, and acetate was added to 0.4% by weight. Oleic acid was neutralized with KOH, solubilized in Tergitol NP-40, and used at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: tetracycline HCl, 12 μg/ml; kanamycin sulfate, 50 μg/ml; and CPTD, 25 μg/ml. CPTD was used for the reasons previously described (51). Chloramphenicol was present at 34 μg/ml, unless otherwise indicated. The detergent, antibiotics, and most bulk chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Solid media contained 1.5% (wt/vol) BactoAgar (Difco, Milwaukee, Wis.). The phenotypes of the various fab mutants were verified by testing for a requirement for unsaturated fatty acids (oleate) on rich-broth plates.

Cultures for genomic expression analyses were grown in minimal M9 medium (35) with 0.4% glycerol as carbon source. Exponentially growing cultures (doubling time of about 2 h) were grown aerobically at 37°C with vigorous rotary shaking. The cultures were repeatedly diluted to ensure exponential growth and were harvested at a cell density of about 108 cells/ml (about 1/20 of the maximal cell density attained in this medium). The growth curves of the fadR and wild-type strains were indistinguishable in the exponential phase of growth in all of the media tested, although the wild-type strain reached a slightly higher maximal cell density.

Cerulenin was dissolved in chloroform, and various volumes of this solution were placed into empty sterile culture tubes and allowed to evaporate to dryness at room temperature. One milliliter of rich broth containing kanamycin was inoculated 1:200 with overnight cultures of strain JWC288 or strain JWC289 and was added to each tube, and the cultures were incubated for 6 h at 37°C in a roller drum. Cell growth was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm.

Genomic expression profiling analysis.

The Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, Tex.) E. coli Panorama array system was used to evaluate the expression of each of the 4,290 open reading frames (ORFs) in the E. coli genome. Experimentally this involved measuring differences in expression in cells grown in M9-glycerol medium with and without supplementation with 0.01% oleic acid. Differential expression was also measured between the reference strain, MG1655, and the isogenic fadR mutant, JWC264, when both strains were grown in M9-glycerol. A third experiment measured the transcriptional differences between the JWC264 (fadR) strain grown with and without oleate supplementation.

RNA isolation and sample handling procedures were those of Tao et al. (52). Briefly, early-log-phase cultures were removed from the shaking incubator and immediately decanted into an equal volume of boiling lysis buffer composed of 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 250 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5), and 20 mM EDTA. The lysed cells were extracted twice with 60°C phenol equilibrated with 100 mM sodium acetate at pH 4.5 and then extracted once with phenol-chloroform (1:1) at room temperature. Nucleic acids were precipitated in 0.5 volumes of 2-propanol and rinsed with a small volume of ice-cold 70% ethanol. The pellet was air dried for 10 to 15 min and dissolved in a small volume of sterile RNase-free water. Approximately 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was added. Residual DNA was removed by incubation with 10 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase I (Promega) at 37°C for about 1 h. The RNA samples were applied to RNeasy columns (Qiagen) and recovered in 30 μl of sterile diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. The RNA was quantitated by absorbance at 260 nm against a water blank. Sample purity was determined by the A260/A280 ratio. Total yields of 10 to 15 μg of RNA with A260/A280 ratios of 1.8 to 2.1 were routinely observed.

The RNA samples consist of a mixture of the various stable RNAs, including tRNA and rRNA, as well as mRNA. To restrict probe synthesis to mRNA, the Panorama E. coli cDNA labeling and hybridization kit (Sigma-Genosys) was used in a standard cDNA synthesis reaction. This kit consists of an equimolar mixture of each of 4,290 C terminus-specific primers. Sample RNA (1 μg) was added to a solution containing a 0.33 mM concentration each of dATP, dGTP, and dTTP and 4 μl of the Sigma-Genosys primer mix. The reaction mixture was brought to a total volume of 25 μl in first-strand synthesis buffer in a small, thin-walled Eppendorf tube. The reaction mixture was placed into a thermal cycler, heated to 90°C for 2 min, and then linearly cooled to 42°C over a 20-min period. On reaching 42°C, 200 U of Superscript II RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) was added along with 20 U of RNase Inhibitor (Promega) and 20 to 30 μCi of [α-33P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) (NEN Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, Mass.). The reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for an additional 3 h. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by centrifugation through Sephadex G-25 gel filtration columns (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). Incorporation levels of 80 to 90% of the total label were routinely achieved by this procedure.

Typically, about 10 to 15 ng of cDNA was recovered from the reverse transcriptase reactions. Estimates of the mRNA content of E. coli range from 3% of total RNA based on pulse-labeling studies to 1.4% based on hybridization experiments (6, 31). These estimates place the total amount of mRNA available in the reverse transcriptase reaction in the neighborhood of 14 to 30 ng. This closely matches the amount of cDNA recovered from the reaction. A crude estimate of the molar amounts of mRNA, based on an average mRNA length of 1 to 2 kb, places the total number of transcripts at about 100 pmol or approximately 1010 molecules. The available nucleoside triphosphates in the reaction mixture could theoretically support the synthesis of about 1011 molecules of 1-kb single-stranded DNA. Under these conditions, with limiting template concentration, excess nucleotides and primer, and a single annealing cycle, the cDNA products approximate both the complexity and the relative abundance of the individual ORFs within the mRNA population.

The hybridization and washing steps were carried out as recommended by the manufacturer of the array. Hybridization buffer consists of 5× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7]), 2% SDS, and 1× Denhardt's reagent supplemented with 100 μg of sheared and sonicated herring sperm DNA per ml. The membranes were prehybridized overnight at 65°C in a roller oven. After prehybridization, the buffer was exchanged for 6 ml of fresh, prewarmed buffer. The cDNA probe sample was heated to 94°C for a few minutes and then added to the hybridization bottle. Samples were hybridized for at least 18 h at 65°C in the roller oven.

When hybridization was complete the membranes were washed twice in 50 ml of a wash solution consisting of 0.5× SSPE and 0.2% SDS at room temperature. This was followed by two washes at 65°C with the same wash solution for 20 min each in the hybridization oven. After the final wash step, the membranes were placed onto blotting paper, wrapped in plastic food wrap, and placed in a PhosphorImager cassette (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The phosphor screen was exposed for 2 to 3 days prior to quantitation.

The TIFF images of each blot were analyzed for pixel depth at each spot position on the membrane using Molecular Dynamics ImageQuant software. The identity of each spot was determined by using a series of ad hoc Perl and AWK scripts and the final output was imported into a spreadsheet. The relative order of gene expression was determined by sorting the data set by ascending ratio value such that the denominator of each ratio is the control sample value. Relative rank was determined by vertical position within the sorted spreadsheet in a manner similar to that of Wei et al. (56). In E. coli, the gene having the greatest increase in expression relative to the control had a relative rank of 1 whereas the gene having the greatest decrease in gene expression had a relative rank of 4,290.

CAT protein assays.

Cells to be assayed were grown overnight in rich media containing the appropriate antibiotics and then diluted 1:200 into 10 ml of rich broth with no antibiotics present. The experimental cultures were incubated at 37°C for about 3 h. Cells were concentrated by low-speed centrifugation and washed twice in ice-cold lysis buffer consisting of 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 1 mM EDTA, and 150 mM NaCl. After cells were resuspended in a small volume of lysis buffer, they were sonicated three times for 15 s each with an S&M sonicator at 40% full power (Sonics and Materials, Inc., Danbury, Conn.). The sonicate was centrifuged for 30 min at high speed (approximately 10,000 × g) to remove insoluble material. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford using the Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

A CAT assay kit, produced by Roche, Inc., was used to measure the mass of CAT protein in cell extracts. The method is based on a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay involving antibodies to CAT bound to the surface of microtiter wells. The cells were lysed, and the cell extracts containing CAT enzyme were added to the wells. Following a 1-h incubation at 37°C the sample extract was discarded. The wells were then washed five times with 250 μl of a washing buffer composed of phosphate-buffered saline and Tween 20. A digoxigenin-labeled antibody to CAT was added, and the plate was incubated for another hour at 37°C. The unbound digoxigenin-labeled antibody was removed, and the wells were washed five times as before. A solution containing peroxidase conjugated to an anti-digoxigenin antibody was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for another hour at 37°C. The peroxidase conjugate was removed, and the plate was washed five times again. The final reaction involved adding the chromogenic peroxidase substrate, 2,2′-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate), and allowing color development for half an hour at room temperature. The absorbance of each well was read at 405 nm, and a reference was taken at 490 nm. A standard activity curve was generated using authentic CAT protein provided by the manufacturer. The standard curve and samples were plotted as A405 − A490 by CAT enzyme concentration.

Gel mobility shift analysis.

A 950-bp DNA fragment including approximately 500 bp of DNA on either side of the fabB start codon was produced by PCR amplification. In this case a standard Taq polymerase amplification reaction was carried out in the presence of a small quantity of [α-33P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) to generate a labeled DNA product. The primers were 5′-AATGTAAGCGTTGTAATTGC-3′ on the 5′ side and 5′-TGTGCGGAAGTCGCACACGC-3′ on the 3′ side. The 950-bp product was purified on a Qiagen PCR purification column.

An E. coli strain, pSS91/BL21(DE3), that produces large amounts of His-tagged FadR, was the generous gift of S. Subrahmanyam (50). Plasmid pSS91 carries the E. coli fadR gene (modified by addition of 13 amino acids including a hexahistidine sequence at the carboxyl terminus of the protein) inserted in the multicloning site of pET16b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). High-level expression of the recombinant fadR gene was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to the culture. The cells were concentrated by low-speed centrifugation and washed twice in a lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0) and 300 mM NaCl. After the cells were resuspended in a small volume of lysis buffer, they were sonicated for 1 min on ice at 40% of full power. The cell extract was centrifuged for 30 min at high speed (approximately 10,000 × g) to remove insoluble material. The fusion protein was prepared by nickel chelate chromatography of the cell-free lysate. The cleared lysate was loaded onto a (0.5 by 2 cm) nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen, Inc.) and washed with 40 ml of a buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. A 30-ml linear gradient of imidazole, from 0 to 500 mM, was used to elute the recombinant FadR. The protein-containing fractions were pooled and dialyzed against a buffer of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA containing 1 mM dithiothreitol. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showed the FadR protein to be substantially pure at this stage. Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 5 mM, and the protein was stored in small aliquots at −80°C until use. Protein concentrations were determined as above.

Gel retardation assays were performed essentially as described by Henry and Cronan (30). Briefly, the basic binding reaction consisted of adding 10 μg of FadR protein to 100 ng of labeled DNA (approximately 50,000 cpm) in a buffer composed of 12 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.9), 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 60 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 100 μg of bovine serum albumin and 12% (vol/vol) glycerol. Under these conditions an almost equimolar ratio of FadR dimer (173 pmol) to DNA (162 pmol) is present. The total volume of the binding assay reaction mixtures was 20 μl. The reaction mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 15 to 20 min and then loaded onto a low-ionic-strength, 4% polyacrylamide gel (8). The preequilibrated gel was run for approximately 3 h at 40 mA at 4°C with constant buffer recirculation. The gel was removed from the electrophoresis apparatus, placed on blotting paper, and dried at 80°C under vacuum. The dried gel was placed in an autoradiography cassette and exposed to Kodak (Rochester, N.Y.) XAR5 film overnight.

RESULTS

Genomic array experiments indicate that fabB is positively regulated by FadR.

Genomic array analysis of global differential transcription patterns in bacteria is useful in defining the extents of metabolic regulons in bacteria (44, 52, 56). A transcriptional regulator such as FadR, having both positive and negative regulatory roles, provides a good test of this experimental approach. Data sets of differential transcription analysis from three separate experimental conditions involving various combinations of FadR and long-chain fatty acid supplementation have been assembled and are available online at http://www.life.uiuc.edu/∼jwcampbe. Analysis of these data confirms a number of features of the current model of FadR regulation.

The FadR protein is known to bind long-chain fatty acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) at nanomolar concentrations (22, 30). When FadR binds acyl-CoA, the ability of the protein to bind DNA is greatly decreased and it no longer functions as an effective transcriptional repressor or activator (11, 19, 30). Transcription of fadBA (encoding the two subunits of the fatty acid degradation complex) is higher in wild-type strains grown in the presence of oleate than in the same strains grown without fatty acids (9) (Table 2). Conversely, transcription of fabA decreased in the absence of FadR or in the presence of long-chain fatty acids (29, 30) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Results of differential transcriptional array analysis of fadBA, fabA, and fabBa

| Gene | JWC264 fadR/MG1655

|

MG1655 + oleate/MG1655 − oleate

|

JWC264 fadR + oleate/JWC264 fadR − oleate

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Ratio | Rank | Ratio | Rank | Ratio | |

| fadA | 44 | 2.39 | 112 | 1.41 | 461 | 1.15 |

| fadB | 2 | 6.41 | 101 | 1.42 | 467 | 1.15 |

| fabA | 4,090 | 0.61 | 4,227 | 0.68 | 184 | 1.37 |

| fabB | 3,954 | 0.70 | 4,279 | 0.40 | 245 | 1.31 |

| All | 1.04 ± 0.32b | 1.03 ± 0.27 | 1.18 ± 0.29 | |||

Strain JWC264 is isogenic to the wild-type strain MG1655 except for introduction of fadR613::Tn10. Wei et al. (56) have established the precedent of using relative ranking to describe genomic array data. In this system, the differential expression ratios of each gene represented on the array are sorted by magnitude and the rank of a given gene is reported relative to the remaining 4,290 genes. For example, in E. coli K-12 the gene exhibiting the greatest increase in transcription under a given condition has a rank of 1, whereas the gene exhibiting the greatest decrease in transcription has a rank of 4,290. The ratio value denotes the transcriptional ratio derived from the raw phosphorimager data.

Values are means and standard deviations for all genes, providing an estimate of the quality of the data and the statistical significance of the ratio values. Complete data sets are available online (see text).

Three separate genomic differential transcriptional analyses were used to measure the effects of various fatty acid and FadR conditions on global gene expression patterns. The first experiment involved examining the differences in gene expression between a fadR null mutant, strain JWC264, with the otherwise isogenic wild-type reference strain, strain MG1655. It should be noted that this fadR null allele, fadR613::Tn10 (also called fadR13::Tn10), has been widely used (19, 20, 26, 29, 30, 47) and that recently the site of transposon insertion into the gene was determined (37). It seems likely that the truncated protein is degraded in vivo since the point of insertion is downstream of the regions important for DNA binding (54). If a protein having functional DNA binding activity was present in cells carrying this insertion, the insertion mutation should act as a dominant negative allele (43), which it does not (20). A second experiment examined transcriptional activity in strain MG1655 grown in the presence and absence of 0.01% oleic acid. This concentration of oleic acid is sufficient for maximal growth of unsaturated fatty acid auxotrophs (5, 12, 46), and similar concentrations result in full induction of the β-oxidation regulon (23, 40). The third data set was produced by comparing gene expression patterns in strain JWC264 grown in the presence and absence of 0.01% oleic acid. Not surprisingly, the magnitude of the differential transcriptional response of FadR regulated genes was greatest in the data set that compared the global transcriptional patterns of the FadR null mutant with the wild-type strain. The data set produced by comparing the global transcriptional activities in a wild-type FadR strain in the presence and absence of oleic acid was similar to that observed in the FadR mutant versus wild type experiment. However, the overall magnitude of the differential transcription of FadR regulated genes was generally lower. This was probably due to residual FadR DNA binding activity in the presence of long-chain acyl-CoAs, versus the complete absence of FadR in strain JWC264.

The fadBA β-oxidation operon is transcribed from a FadR-regulated promoter (9), and thus, the parallel behavior of these two genes within the global transcriptional arrays was expected. However, fabA and fabB are well-separated transcriptional units (one-fifth of the genetic map). The major fabA promoter is regulated by FadR and is downstream of a second weak constitutive promoter. The promoter of fabB is not as well characterized (32) but is likely to be complex. The similarity of the differential transcriptional responses of fabB to fabA under the various experimental conditions suggests that fabB expression is modulated by a mechanism similar to that of fabA.

Temperature-sensitive fabB mutations are synthetically lethal with fadR.

The first indications that fabA was positively regulated by FadR were the discoveries that fadR strains contained abnormally low levels of cellular unsaturated fatty acid and, more definitively, that fabA(Ts) fadR double mutants were unable to grow even at low temperature unless unsaturated fatty acids were provided (38). The explanation for this finding is that in the presence of functional FadR, sufficient mutant FabA is produced to provide a level of isomerase activity that satisfies cellular unsaturated fatty acid requirements. Indeed, fabA(Ts) strains have been shown to contain abnormally low levels of cellular unsaturated fatty acid at permissive temperatures (38). In contrast, even at the permissive temperature (30°C), fabA(Ts) fadR strains are unable to synthesize enough mutant FabA to provide sufficient unsaturated fatty acid for functional cell membranes (15). Our interpretation of these data is that E. coli can tolerate normal levels of expression of a FabA enzyme of compromised catalytic efficiency or low levels of expression of the wild-type enzyme but cannot survive low levels of expression of a catalytically compromised mutant enzyme.

To test whether fabB mutants might also be synthetically lethal with fadR mutations, the behaviors of fabB(Ts) and fabB(Ts) fadR strains grown under various conditions were examined. Each strain was grown overnight on medium supplemented with 0.01% oleate prior to inoculating experimental cultures. The cultures were incubated at 30 or 42°C overnight and then examined for growth (Table 3). The fabA(Ts) strain M8 grew at 30°C in the presence or absence of oleate, but at 42°C the strain grew only when supplemented with oleate (4, 5). In contrast, at either temperature a fabA(Ts) fadR double mutant grew only in the presence of exogenous oleate (38). A phenotypic behavior that paralleled the fabA case was shown by fabB(Ts) and fabB(Ts) fadR strains. The fabB(Ts) strain M5 required oleate for growth only at 42°C, whereas the fabB(Ts) fadR strain, JWC287, failed to grow at either temperature unless oleate was provided. Thus, the synthetic lethal behavior towards fadR reported for fabA(Ts) mutants was also found for a fabB(Ts) mutant. This result strongly suggests that FadR positively activates expression of fabB, as is the case with fabA. Two other observations support this hypothesis. The first is that the fabB(Ts) fadR strain grew at the permissive temperature on solid media, but the same strain failed to grow in liquid cultures shaken in flasks under standard conditions. However, the fabB(Ts) fadR strain grew in liquid medium when mechanical stress was minimized (in a thin film of liquid with minimal agitation as in Table 3). It therefore seems that the structural integrity of the membranes of these strains was compromised to the point that the cells became very sensitive to mechanical stress (5).

TABLE 3.

Growth of strains M5, M8, JWC286, and JWC287a

| Strain | Relevant genotype | OD600 at:b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C

|

42°C

|

||||

| With oleate | Without oleate | With oleate | Without oleate | ||

| M5 | fabB(Ts) | ++ | ++ | ++ | − |

| JWC287 | fabB(Ts) fadR | ++ | − | + | − |

| M8 | fabA(Ts) | + | ++ | ++ | − |

| JWC286 | fabA(Ts) fadR | + | − | + | − |

Growth was assayed after overnight incubation at the indicated temperatures in liquid cultures grown with maximal surface area and minimal agitation.

OD600, optical density at 600 nm; −, OD600 < 0.073; +, OD600 between 0.750 and 1.10; ++, OD600 > 1.10.

The second observation is based on the previously noted synthetic lethality seen in fabB(Ts) fabF strains (24). Such strains failed to grow at the nonpermissive temperature when supplemented with oleic acid, although the fabB(Ts) strain grew well under these conditions and fabF mutants lack a growth phenotype. The fabB(Ts) fabF strains grow well at permissive temperature with or without oleic acid supplementation, and the failure to grow at nonpermissive temperature is due to the lack of sufficient condensing enzyme activity for saturated fatty acid synthesis (17, 24, 53). We attempted to obtain fadR613::Tn10 transductants of a fabB(Ts) fabF strain at permissive temperature and failed even when the medium contained oleic acid. The triple mutant fabB(Ts) fabF fadR613::Tn10 strain could be constructed only when the recipient strain carried a plasmid expressing fabB (the pARAfabB plasmid was used). Apparently, in the absence of FabF and FadR, even at the permissive temperature the synthetic demand placed on the decreased level of the FabB(Ts) enzyme exceeded its capacity to produce sufficient fatty acids to support growth.

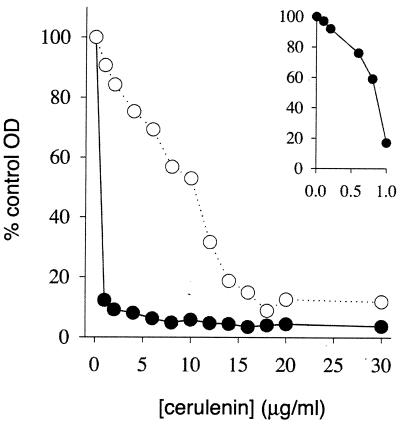

A fadR strain is hypersensitive to cerulenin.

The behavior of the fabB(Ts) strains with respect to FadR suggested that fadR mutants might be more susceptible to the specific 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase inhibitor cerulenin (39). Although both 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthases I and II are inhibited by this antibiotic, synthase I (FabB) is about sevenfold more sensitive than synthase II (FabF) in vitro (41). In vivo results indicate similar differential effects on the two enzymes (6, 53). Therefore we expected that, due to decreased FabB levels, fadR strains should be more sensitive to cerulenin than were wild-type strains. This was found to be the case (Fig. 1). The cerulenin concentration that gave one-half the maximal growth of the wild-type strain was between 8 and 16 μg/ml, which agrees well with the value of 12.5 μg/ml reported by Omura (39). In contrast, the fadR mutant strain failed to show detectable growth even at low cerulenin concentrations and almost complete growth inhibition was seen at 1 μg of cerulenin per mg. Therefore, the fadR strain was at least 10-fold more sensitive to cerulenin than was the wild-type strain, indicating lower levels of FabB, the primary target of the antibiotic. Both strains used in this experiment contained plasmid pRC1 which produces sufficient FabA enzyme to allow growth of fabA(Ts) mutants at the nonpermissive temperature (14). This plasmid was introduced to ensure that the effect of cerulenin was due to changes in the level of FabB and not to possible secondary effects of the fadR mutation on fabA expression.

FIG. 1.

Growth inhibition by cerulenin. Cells were grown overnight and inoculated (1:200) into rich broth. One-milliliter samples were placed into culture tubes containing the indicated amounts of cerulenin. The cultures were incubated for 6 h at 37°C prior to measuring growth. Open circles, parental fadR wild-type strain; solid circles, strain fadR613::Tn10; OD, optical density.

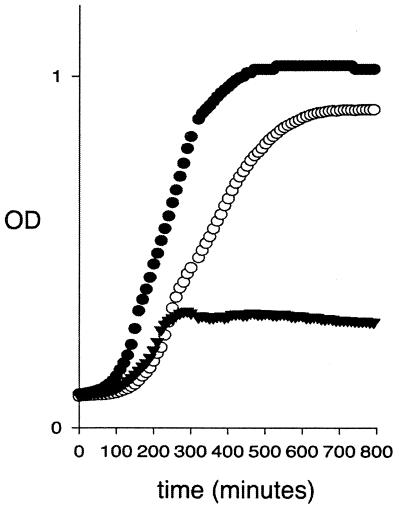

Decreased expression of fabB in fadR strains.

Our genomic array experiments indicated that fabB was positively regulated by FadR and that the level of expression was depressed in cultures of the fadR mutant strain, JWC264. Measuring fabB expression by assays of 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase activity is complicated by the presence of a second 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (FabF), which has a similar level of activity and overlapping substrate specificity. We therefore constructed a chromosomal transcriptional fusion in which the fabB promoter was used to drive expression of a promoterless CAT gene. Since FabB provides at least one essential cellular function, we provided a functional copy of fabB in trans to allow growth in the absence of unsaturated fatty acid supplementation. The plasmid used, pARAfabB, expresses fabB from the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium araBAD promoter. Although this promoter is generally considered to have low residual activity in the absence of inducer (7, 27), the basal level of activity from the uninduced promoter provided sufficient 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase activity to complement loss of the chromosomal fabB gene (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of fabB::CAT strains. Cells grown overnight in rich broth supplemented with 0.01% oleate were inoculated (1:200) into 200 μl of medium lacking oleate. The experimental cultures were placed in 96-well microtiter dishes at 37°C, and growth was monitored for 18 h. Solid circles, parental fabB wild-type strain; solid triangles, fabB::CAT strain; open circles, fabB::CAT strain carrying the pARAfabB plasmid. Similar results were found in the presence or absence of arabinose. OD, optical density.

The level of CAT enzyme produced in strain JWC276, carrying the transcriptional fusion and a functional fadR gene, was sufficient to allow growth on media supplemented with 34 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. However, when a fadR null mutation was transduced into this strain, the transductants could tolerate only low (<10 μg/ml) levels of chloramphenicol. The levels of CAT protein in these two strains were examined by an immunological assay. The strain producing functional FadR was found to have CAT protein levels more than twice those of strains lacking FadR. Strain JWC276 (wild type) was found to contain 1.95 ± 0.28 pg of CAT/μg of protein while JWC277 (fadR::Tn10) produced 0.86 ± 0.10 pg of CAT/μg of protein (means ± standard deviations of three separate measurements), a 2.3-fold difference.

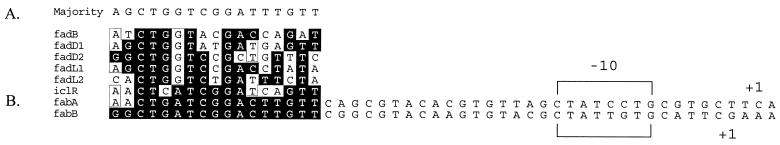

Purified FadR binds to DNA sequences upstream of the fabB −10 promoter region.

Scrutiny of the sequences in the promoter region of fabB showed that a region about 70 bp upstream of the fabB start codon had a good match to known FadR binding sites. Alignment of this sequence with those of the known FadR binding sites (listed at http://arep.med.harvard.edu/ecoli_matrices/dat/fadR.dat) is shown in Fig. 3 (data of Robison et al. [45]). The sequence of the putative fabB FadR binding site most closely matches those of the two positively regulated genes iclR and fabA. Both the iclR- and fabA-associated FadR binding sites are known to overlap the −35 regions of their respective promoters (26, 30). The fabB transcriptional start has been mapped (32), and the upstream region is typical of a promoter requiring positive activation in that the −10 region has a good match to the consensus for E. coli promoters, but there is no obvious −35 consensus sequence (25). As is the case for both iclR and fabA, the putative FadR binding site of fabB overlaps the −35 region of the promoter, which is thought to position FadR protein to act as a transcriptional activator.

FIG. 3.

Consensus alignment of known FadR binding sites and the putative fabB-associated site (alignment data from reference 45). (A) Consensus alignments within the FadR binding region are boxed, and sequences conserved in fabB are shaded. With the exception of fabB, all the sequences shown have been documented by published FadR footprinting or gel shift experiments (see reference 47 and references therein). (B) The entire promoter regions of fabA and fabB are shown. The transcriptional start sites, indicated as +1, are from the FadR-dependent fabA promoter (30) and the fabB promoter (32).

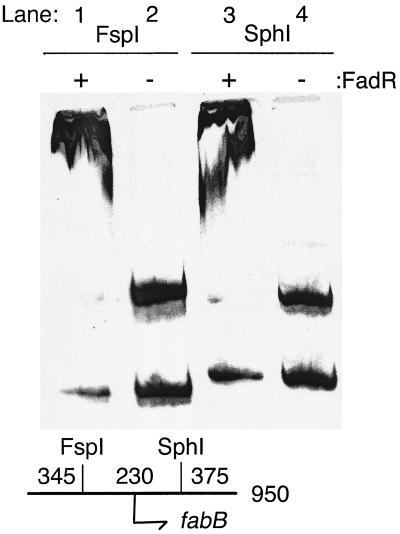

To determine whether or not the DNA upstream of the fabB coding sequence binds FadR, an in vitro gel shift analysis was conducted. A 950-bp 33P-labeled DNA fragment containing the fabB-associated, putative FadR binding site was produced from chromosomal DNA. The FadR protein was a His-tagged fusion protein known to be fully functional in vivo (50) that was purified by nickel chelate chromatography. Gel mobility shift experiments showed that the labeled fabB DNA was bound by FadR (Fig. 4). The specificity of FadR DNA binding was demonstrated by the finding that when the fabB DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes FspI and SphI, the DNA fragment containing the putative binding site was shifted by FadR whereas the other fragment migrated to its expected position. Although these gel shifts suffer from nonspecific trapping of DNA, they localize the fabB-associated FadR binding site to an approximately 230-bp region at the beginning of the fabB gene consistent with the site detected by sequence inspection. Additional characterization of FadR binding by fabB DNA will be the subject of future work.

FIG. 4.

Gel shift assays of FadR and the putative fabB-associated binding site. The assay tests the ability of FadR to specifically bind and retard the electrophoretic mobility of the fabB-associated putative FadR binding site. The binding conditions are given in the text, and the ratios of FadR dimer to target DNA are essentially equimolar. The presence or absence of FadR in the binding assay is indicated by + or − at the top of each lane. Lanes 1 and 2 are the products of an FspI restriction digest of the labeled fragment. In the presence of FadR, the 605-bp fragment was shifted, indicating that FadR specifically binds to that DNA fragment. Likewise, when the 950-bp fragment was digested with SphI only one of two resulting fragments was bound by FadR, as shown in lanes 3 and 4. The relative positions of the FspI and SphI sites and the fabB start codon are given in the lower left of the figure.

DISCUSSION

The evidence presented indicates that FadR positively regulates fabB transcription. The fact that both fabA and fabB, alone among the fatty acid biosynthetic genes, are directly regulated by FadR indicates that E. coli has a vested interest in regulating unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis even when exogenous fatty acids are available. In retrospect, coordinated regulation of fabA and fabB might have been anticipated since in Pseudomonas aeruginosa it was recently shown that the two genes are cotranscribed in a two-gene fabA-fabB operon (31), although there is no evidence of transcriptional regulation of the operon. The available partial genomic sequences of Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas syringae that fabA and fabB are also adjacent genes in these organisms (data not shown).

The two E. coli long-chain acyl-ACP elongation enzymes, FabB and FabF, play different roles in unsaturated fatty acid synthesis. Both enzymes catalyze the Claissen-like condensation of malonyl-ACP with the growing acyl chain. Although the two enzymes are structurally and functionally very similar, they play different roles in cellular metabolism, as shown by the very different phenotypes of fabB and fabF mutants and of strains carrying recombinant plasmids encoding either of the two enzymes. Null fabF mutants have no growth phenotype, whereas fabB mutants require an exogenous source of unsaturated fatty acids. Likewise, strains carrying recombinant fabB plasmids are well behaved, whereas similar plasmids carrying fabF are prone to deletion and rearrangement (34, 51). Recently, it has been shown that FabF effectively titrates FabD (malonyl coenzyme A:ACP transacylase) and that overproduction of FabD offsets the toxicity of fabF plasmids (51). The exact role of FabB in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis has not been directly demonstrated in vitro and currently seems to be a puzzle (41, 55). FabB is generally thought to catalyze elongation of the cis-3-decanoyl-ACP produced by FabA to 3-ketododecanoyl-ACP. This is inferred from the findings that fabF strains have no apparent growth phenotype and that fabB mutants require only unsaturated fatty acids for growth. In vitro tests with purified FabF and FabB proteins show that both enzymes are capable of catalyzing the condensation of malonyl-ACP and cis-3-decenoyl-ACP (24, 55). The discrepancy between the genetic and biochemical observations indicates that the biochemical characterization of these enzymes does not accurately reflect their behavior in vivo. Unfortunately, resolution of these issues is problematic, since double knockouts of fabB and fabF are nonviable and fabF(Ts) strains are not available. Furthermore, double mutant fabF fabB(Ts) strains are nonviable at high temperature despite supplementation with both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids probably due to the inability to provide precursors for lipid A biosynthesis (24).

The levels of FabA activity normally present do not limit the synthetic capacity for unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in E. coli. This has been shown by examining the effects of FabA overproduction on cellular fatty acid composition (10). Unexpectedly, the cellular content of unsaturated fatty acids did not change, but the content of saturated fatty acids increased markedly. This effect was reversed by introduction of a second plasmid encoding FabB. These results were interpreted as indicating that the level of FabB governs the overall rate of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. This is supported by studies that showed that overproduction of FabB about 10-fold (without manipulating FabA) results in increased unsaturated fatty acid production (17). Therefore, fabB may be the most effective point at which to regulate flux of this pathway. However, in order to regulate the level of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis without the complication of altering the level of saturated fatty acids produced, E. coli may need to simultaneously coordinate changes in expression of both fabA and fabB.

Why does FadR regulate only the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in response to exogenous supplementation? One clue may be that although exogenous supplementation can satisfy the entire unsaturated fatty acid requirement of E. coli, supplementation with saturated fatty acids cannot completely replace the function of that branch of the pathway. The reason for the differing efficiencies of supplementation is the fatty acid chains of the essential outer membrane component lipid A, which are derived from the saturated pathway. These fatty acids (mainly 3-hydroxymyristic acid) cannot be effectively supplied in the medium. Although when added to the culture medium 3-hydroxymyristic acid enters E. coli (and can serve as a carbon source), the supplied acid is not incorporated into lipid A (34). This is probably due to lack of conversion of the acid to the required ACP thioester (42). Therefore, if E. coli were to shut down both the saturated and unsaturated fatty acid synthetic pathways in response to exogenous supplementation, the organism would perish from a lack of the acyl chains needed to synthesize lipid A.

In general, the amplitudes of transcriptional regulation which we observed in our microarray analyses are less than those observed in enzyme assays, Northern blot analyses, and gene fusion experiments. To an unknown extent this may be due to the use of ratio values as the output of the current array techniques. If the expression signal of a gene in the control cultures is small and variable (for either technical or physiological reasons), these factors can have very large effects on the calculated ratios. Another possibility is that the differences might reflect mRNA decay. In our protocol we are primarily sampling the 3′ end of the mRNAs due to the use of primers that hybridize to the ORF C termini, whereas the other techniques measure the full-length mRNA (either directly or indirectly). Therefore, the systems may differ due to mRNA turnover. Bacterial mRNA turnover is not yet well understood and the patterns of degradation seem to be mRNA specific (49). Recent data argue that in many messages the 3′ end is the last segment degraded (49). (This is attributed to blocking of nuclease activity by the RNA hairpin left from factor-independent transcription termination.) Moreover, it is unclear whether or not the level of a given mRNA in E. coli can alter the rate or pattern of degradation of itself or of other mRNAs.

Many improvements to the existing array technologies seem possible. Quantitative tests of the various RNA isolation, priming, blotting, and detection methods have yet to be published. It is our opinion that even when the technology is fully developed this technology might best be viewed as a divining rod to find new regulatory circuitry, rather than as a quantitative tool.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI15650.

We thank C. O. Rock for free exchanges of information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldassare J J, Rhinehart K B, Silbert D F. Modification of membrane lipid: physical properties in relation to fatty acid structure. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2986–2994. doi: 10.1021/bi00659a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black P N, Faergeman N J, DiRusso C C. Long-chain acyl-CoA-dependent regulation of gene expression in bacteria, yeast and mammals. J Nutr. 2000;130:305S–309S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.305S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloch K. β-Hydroxythioester dehydrase. 3rd ed. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broekman J H. Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht, Holland: Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broekman J H, Steenbakkers J F. Growth in high osmotic medium of an unsaturated fatty acid auxotroph of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1973;116:285–289. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.1.285-289.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buttke T M, Ingram L O. Inhibition of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli by the antibiotic cerulenin. Biochemistry. 1978;17:5282–5286. doi: 10.1021/bi00617a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cagnon C, Valverde V, Masson J M. A new family of sugar-inducible expression vectors for Escherichia coli. Protein Eng. 1991;4:843–847. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chodosh L A. DNA-protein interactions. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J, Struhl A K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Interscience; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark D P. Regulation of fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: analysis by operon fusion. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:521–526. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.521-526.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark D P, DeMendoza D, Polacco M L, Cronan J E., Jr β-Hydroxydecanoyl thio ester dehydrase does not catalyze a rate-limiting step in Escherichia coli unsaturated fatty acid synthesis. Biochemistry. 1983;22:5897–5902. doi: 10.1021/bi00294a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronan J E., Jr In vivo evidence that acyl coenzyme A regulates DNA binding by the Escherichia coli FadR global transcription factor. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1819–1823. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1819-1823.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cronan J E, Jr, Birge C H, Vagelos P R. Evidence for two genes specifically involved in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1969;100:601–604. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.2.601-604.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronan J E, Jr, Gelmann E P. Physical properties of membrane lipids: biological relevance and regulation. Bacteriol Rev. 1975;39:232–256. doi: 10.1128/br.39.3.232-256.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronan J E, Jr, Li W B, Coleman R, Narasimhan M, de Mendoza D, Schwab J M. Derived amino acid sequence and identification of active site residues of Escherichia coli β-hydroxydecanoyl thioester dehydrase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4641–4646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cronan J E, Jr, Subrahmanyam S. FadR, transcriptional co-ordination of metabolic expediency. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:937–943. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datsenko K A, Wanner B L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Mendoza D, Klages Ulrich A, Cronan J E., Jr Thermal regulation of membrane fluidity in Escherichia coli. Effects of overproduction of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:2098–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiRusso C C, Black P N, Weimar J D. Molecular inroads into the regulation and metabolism of fatty acids, lessons from bacteria. Prog Lipid Res. 1999;38:129–197. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(98)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiRusso C C, Metzger A K, Heimert T L. Regulation of transcription of genes required for fatty acid transport and unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli by FadR. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiRusso C C, Nunn W D. Cloning and characterization of a gene (fadR) involved in regulation of fatty acid metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:583–588. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.583-588.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiRusso C C, Nystrom T. The fats of Escherichia coli during infancy and old age: regulation by global regulators, alarmones and lipid intermediates. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiRusso C C, Tsvetnitsky V, Hojrup P, Knudsen J. Fatty acyl-CoA binding domain of the transcription factor FadR. Characterization by deletion, affinity labeling, and isothermal titration calorimetry. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33652–33659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farewell A, Diez A A, DiRusso C C, Nystrom T. Role of the Escherichia coli FadR regulator in stasis survival and growth phase-dependent expression of the uspA, fad, and fab genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6443–6450. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6443-6450.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garwin J L, Klages A L, Cronan J E., Jr Structural, enzymatic, and genetic studies of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases I and II of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11949–11956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gralla J D, Collado-Vides J. Organization and function of transcription regulatory elements. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1232–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gui L, Sunnarborg A, LaPorte D C. Regulated expression of a repressor protein: FadR activates iclR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4704–4709. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4704-4709.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzman L M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath R J, Rock C O. Roles of the FabA and FabZ beta-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratases in Escherichia coli fatty acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27795–27801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry M F, Cronan J E., Jr Escherichia coli transcription factor that both activates fatty acid synthesis and represses fatty acid degradation. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:843–849. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90574-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry M F, Cronan J E., Jr A new mechanism of transcriptional regulation: release of an activator triggered by small molecule binding. Cell. 1992;70:671–679. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90435-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoang T T, Schweizer H P. Fatty acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: cloning and characterization of the fabAB operon encoding β-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase (FabA) and β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I (FabB) J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5326–5332. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5326-5332.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kauppinen M, Siggaard-Andersen M, von Wettstein-Knowles P. β-Ketoacyl-ACP synthase I of Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence of the fabB gene and identification of the cerulenin binding residue. Carlsberg Res Commun. 1988;53:357–370. doi: 10.1007/BF02983311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein K, Steinberg R, Fiethen B, Overath P. Fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli. An inducible system for the uptake of fatty acids and further characterization of old mutants. Eur J Biochem. 1971;19:442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magnuson K, Jackowski S, Rock C O, Cronan J E., Jr Regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:522–542. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.522-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohan S, Kelly T M, Eveland S S, Raetz C R, Anderson M S. An Escherichia coli gene (FabZ) encoding (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl acyl carrier protein dehydrase. Relation to fabA and suppression of mutations in lipid A biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32896–32903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nichols B P, Shafiq O, Meiners V. Sequence analysis of Tn10 insertion sites in a collection of Escherichia coli strains used for genetic mapping and strain construction. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6408–6411. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6408-6411.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nunn W D, Giffin K, Clark D, Cronan J E., Jr Role for fadR in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:554–560. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.554-560.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omura S. The antibiotic cerulenin, a novel tool for biochemistry as an inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:681–697. doi: 10.1128/br.40.3.681-697.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Overath P, Raufuss E M. The induction of the enzymes of fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;29:28–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(67)90535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price A C, Choi K H, Heath R J, Li Z, White S W, Rock C O. Inhibition of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases by thiolactomycin and cerulenin: structure and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6551–6559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raetz C R. Bacterial endotoxins: extraordinary lipids that activate eucaryotic signal transduction. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5745–5753. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5745-5753.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raman N, Black P N, DiRusso C C. Characterization of the fatty acid-responsive transcription factor FadR. Biochemical and genetic analyses of the native conformation and functional domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30645–30650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richmond C S, Glasner J D, Mau R, Jin H, Blattner F R. Genome-wide expression profiling in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3821–3835. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robison K, McGuire A M, Church G M. A comprehensive library of DNA-binding site matrices for 55 proteins applied to the complete Escherichia coli K-12 genome. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:241–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silbert D F, Vagelos P R. Fatty acid mutant of E. coli lacking a β-hydroxydecanoyl thioester dehydrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:1579–1586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.4.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simons R W, Egan P A, Chute H T, Nunn W D. Regulation of fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: isolation and characterization of strains bearing insertion and temperature-sensitive mutations in gene fadR. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:621–632. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.2.621-632.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singer M, Baker T A, Schnitzler G, Deischel S M, Goel M, Dove W, Jaacks K J, Grossman A D, Erickson J W, Gross C A. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steege D A. Emerging features of mRNA decay in bacteria. RNA. 2000;6:1079–1090. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subrahmanyam S. Ph.D. dissertation. Urbana: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Subrahmanyam S, Cronan J E., Jr Overproduction of a functional fatty acid biosynthetic enzyme blocks fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4596–4602. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4596-4602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tao H, Bausch C, Richmond C, Blattner F R, Conway T. Functional genomics: expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6425–6440. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6425-6440.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ulrich A K, de Mendoza D, Garwin J L, Cronan J E., Jr Genetic and biochemical analyses of Escherichia coli mutants altered in the temperature-dependent regulation of membrane lipid composition. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:221–230. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.221-230.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Aalten D M, DiRusso C C, Knudsen J, Wierenga R K. Crystal structure of FadR, a fatty acid-responsive transcription factor with a novel acyl coenzyme A-binding fold. EMBO J. 2000;19:5167–5177. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.von Wettstein-Knowles P, Olsen J, Arnvig Mcguire K, Larsen S. Molecular aspects of β-ketoacyl synthase (KAS) catalysis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:601–607. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0280601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei Y, Lee J M, Richmond C, Blattner F R, Rafalski J A, LaRossa R A. High-density microarray-mediated gene expression profiling of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:545–556. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.545-556.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]