Abstract

Skin epidermis constitutes the exterior barrier that protects the body from dehydration and environmental assaults. Barrier defects underlie common inflammatory skin diseases, but the molecular mechanisms that maintain barrier integrity and regulate epidermal–immune cell cross-talk in inflamed skin are not fully understood. In this study, we show that skin epithelia-specific deletion of Ovol1, which encodes a skin disease–linked transcriptional repressor, impairs the epidermal barrier and aggravates psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice in part by enhancing neutrophil accumulation and abscess formation. Through molecular studies, we identify IL-33, a cytokine with known pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory activities, and Cxcl1, a neutrophil-attracting chemokine, as potential weak and strong direct targets of Ovol1, respectively. Further-more, we provide functional evidence that elevated Il33 expression reduces disease severity in imiquimod-treated Ovol1-deficient mice, whereas persistent accumulation and epidermal migration of neutrophils exacerbate it. Collectively, our study uncovers the importance of an epidermally expressed transcription factor that regulates both the integrity of the epidermal barrier and the behavior of neutrophils in psoriasis-like inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

Skin epidermis is a self-renewing epithelium composed of stem/progenitor cells that terminally differentiate to produce stratum corneum, which constitutes a physical barrier at the skin’s outmost surface against myriad external assaults (Gonzales and Fuchs, 2017). Common inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis are associated with disruption of this epidermal barrier either as a trigger for disease or as a secondary consequence of immune cell dysregulation (Harden et al., 2015; Ring et al., 2012; Schmuth et al., 2015; Segre, 2006). Moreover, disease progression is facilitated by epidermal cell regulation of and response to immune cells (Kobayashi et al., 2019; Pasparakis et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019). However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate epidermally driven communication between epidermal and immune cells in coordination with barrier maintenance remain largely unknown.

Previously, we reported that germline deletion of Ovol1, which encodes a transcription factor known to regulate epidermal development (Dai et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2014; Nair et al., 2006; Teng et al., 2007), leads to exacerbated skin inflammation and epidermal hyperplasia in response to imiquimod (IMQ), an agent widely used to induce psoriasis-like symptoms in mice (Sun et al., 2021; van der Fits et al., 2009). Moreover, human OVOL1 is upregulated in psoriatic lesions (Sun et al., 2021). Neutrophil accumulation in differentiated layers of the epidermis (Munro’s abscesses) distinguishes a subset of human patients with psoriasis and is a key feature of psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice (Chiang et al., 2019; Pinkus and Mehregan, 1966; Sumida et al., 2014; Uribe-Herranz et al., 2013). Epidermal keratinocytes (KCs) play an important role in neutrophil recruitment by secreting cytokine/chemokines such as IL-1α, CXCL1, CXCL8, and LTB4 (Milora et al., 2015; Olaru and Jensen, 2010; Sumida et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2021). Although we found elevated levels of IL-1α in IMQ-treated Ovol1 null epidermis (Sun et al., 2021), it remains unclear whether Ovol1 functions within the epidermis to directly regulate epidermal neutrophil cross-talk and whether it promotes barrier integrity.

In this work, we generated and analyzed mice with skin epithelia–specific knockout (SSKO) of Ovol1 and examined their responses to IMQ. We found that epidermal loss of Ovol1 dramatically aggravates IMQ-induced barrier disruption, epidermal hyperplasia, and neutrophil accumulation. In contrast, there was a reduction of lymphocytes, except for regulatory T cells (Tregs). We detected upregulated expression of Il33—the human counterpart of which is suppressed by OVOL1 overexpression (Furue et al., 2019; Tsuji et al., 2020)—in the skin of Ovol1 SSKO mice but found IL-33 antibody neutralization to further enhance the psoriasis-like skin phenotypes of these mice. We showed that Ovol1 protein binds weakly to the Il33 promoter but strongly to the promoter of Cxcl1, and indeed Cxcll expression was elevated in Ovol1-deficient epidermis. Finally, we obtained evidence that Ovol1 loss facilitates neutrophil accumulation near and migration through the epidermis and that neutrophil depletion partially mitigates the psoriasis-like phenotypes of Ovol1-deficient mice. Together, our findings uncover an epidermal-intrinsic transcription factor that both promotes barrier integrity and directly suppresses neutrophil accumulation in psoriasis-like inflammation.

RESULTS

Ovol1 acts in the epidermis to promote robust barrier maintenance and to suppress IMQ-induced epidermal hyperplasia

The skin of Ovol1−/− mice exhibit elevated Il1a expression in response to IMQ (Sun et al., 2021). Because barrier disruption increases Il1a transcription (Wood et al., 1992), we asked whether Ovol1−/− skin is barrier defective by performing transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurements, a widely used method to assess epidermal barrier function (Alexander et al., 2018). During homeostasis (day 0), TEWL values were the same between Ovol1−/− and control littermates (Figure 1a and b). However, after IMQ treatment, which is known to induce transient barrier disruption (Barland et al., 2004), the Ovol1−/− mutants displayed significantly higher and longer-lasting TEWL increases than their control littermates (Figure 1a). Similarly, enhanced barrier disruption was observed in Ovol1−/− mice after tape stripping (Figure 1b).

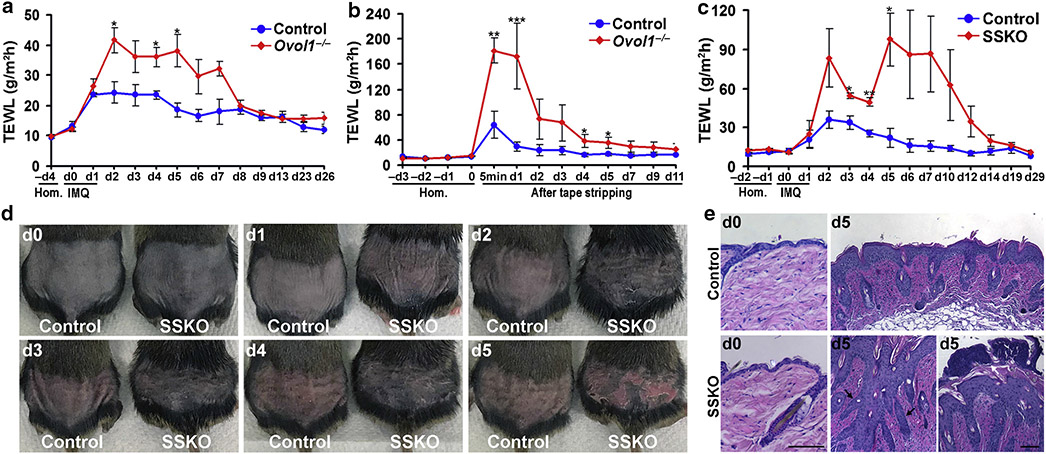

Figure 1. Loss of Ovol1 in the epidermis aggravates IMQ-induced barrier disruption and epidermal hyperplasia.

(a–c) TEWL measurements of (a, b) Ovol1−/− or (c) Ovol1 SSKO mice along with their control littermates after (a, c) IMQ treatment or (b) tape stripping, starting on d0, where d before perturbation represent Hom. n = 3 for control littermates in a–c. For mutants, (a) n = 5 (b, c) n =3. (d) External appearance at different d after the first IMQ application. (e) Skin histology on d0 and d5. Black and white arrows point to finger-like epidermal projections and neutrophil aggregates on the skin surface, respectively. Bar = 100 μm. *** P < 0.005; ** P < 0.01; * P < 0.05. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. d, day; Hom, homeostasis; IMQ, imiquimod; SSKO, skin epithelia–specific knockout; TEWL, transepidermal water loss.

To ask whether Ovol1 functions within the epidermis to regulate barrier maintenance, we generated Ovol1 SSKO (Ovol1−/f; K14-Cre, where Ovol1 is deleted in epithelial cells of the skin) mice in a congenic C57BL/6 (B6) background. Similar to Ovol1−/− mice, during homeostasis, TEWL values in Ovol1 SSKO mice showed no deviation from those of their control littermates (Figure 1c). Consistently, expression of epidermal terminal differentiation markers appeared largely normal in Ovol1 SSKO skin (Supplementary Figure S1a). On IMQ treatment, Ovol1 SSKO mice displayed significantly more dramatic and persistent TEWL increases than their control littermates (Figure 1c). Therefore, Ovol1 expression in the epidermis is required for maintaining a robust barrier when skin is under external physical or chemical assaults.

We also asked whether Ovol1 suppression of IMQ-induced inflammation is intrinsic to the epidermis. Ovol1 SSKO mice showed dramatically more severe psoriasis-like phenotypes that included erythema, scaling, and epidermal hyperplasia after 5 consecutive days of IMQ treatments than weight- and sex-matched littermate controls (Figure 1d and e). Exacerbated phenotypes of Ovol1 SSKO mice could also be observed after only 2 consecutive days of IMQ treatments (Supplementary Figure S1 b). Interestingly, under identical IMQ treatment conditions, the psoriatic-like symptoms, including epidermal hyperplasia, of Ovol1 SSKO mice appeared comparable with, if not more remarkable than, those of the Ovol1−/− mice, with the SSKO skin presenting finger-like projections reminiscent of the elongated rete ridges in psoriasiform hyperplasia of human patients (Murphy et al., 2007) (Figure 1e and Supplementary Figure S1c and d). Together, our findings show that Ovol1 is required in the epidermis to suppress IMQ-induced epidermal hyperplasia and the associated skin phenotypes.

Acute immune responses in IMQ-treated Ovol1 SSKO skin feature increased neutrophil abundance and decreased T cell presence

Next, we performed flow cytometry to compare the immune cell compositions between IMQ-treated control and Ovol1 SSKO mice. At 24 hours after the second IMQ treatment, we detected a ~3.7-fold increase in neutrophils (CD45+/Ly6G+/CD11b+) in Ovol1 SSKO skin compared with that in the control littermate skin, whereas similar numbers of total immune (CD45+) cells and macrophages (CD45+/F4/80+/CD11b+/Ly6G−) were observed (Figure 2a and b and Supplementary Figure S2a). These data show that loss of epidermal expression of Ovol1 results in an increased early influx of neutrophils in IMQ-treated skin.

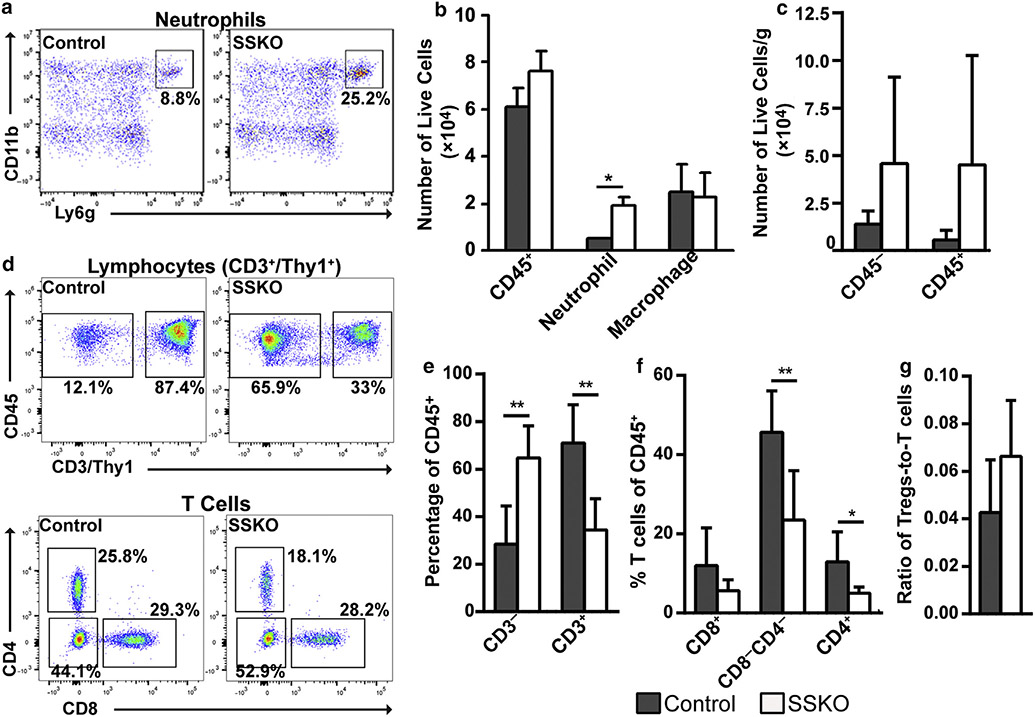

Figure 2. Immune cell profiles in IMQ-treated control and Ovol1 SSKO skin. Shown are summaries of the flow cytometry data collected.

(a) 24 hours and (b–e) 6d after the second IMQ application. Representative flow plots are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. (a) n = 3 pairs of Ovol1 SSKO and control littermates and (b–e) n = 7 control and n = 6 mutants. ** P < 0.01; * P < 0.05. Error bars represent mean ± SD. IMQ, imiquimod; SSKO, skin epithelia–specific knockout; Treg, regulatory T cell.

We also examined the impact of Ovol1 deletion on components of the adaptive immune response, which generally develops around 5–14 days after IMQ treatment (Miao et al., 2010). Specifically, we employed two consecutive IMQ applications to minimize indirect consequences from dramatic epidermal thickening and barrier disruption (Supplementary Figure S1a and b) and performed flow cytometry 6 days later. Compared with those in the control counterparts, the average numbers of both CD45+ (immune) and CD45− cells were increased in Ovol1 SSKO skin, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 2c and Supplementary Figure S2b and c). Importantly, the percentage of CD3+ lymphocytes (CD45+CD3/Thy1+) of total immune (CD45+) cells was significantly lower in Ovol1 SSKO skin than in control skin, whereas the percentage of nonlymphocytes was significantly elevated (Figure 2d and e). A significant reduction was observed for the relative abundance of both CD4+ T cells and CD8−CD4− T cells (which likely includes ɤδT cells [Cai et al., 2011; Tigelaar et al., 1990]) subsets (Figure 2d and f), whereas the relative abundance of Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) showed a trend of increase in the mutant mice (Figure 2g and Supplementary Figure S2c and d). All these differences were normalized 1 –3 months after IMQ treatment (Supplementary Figure S2e-h). Collectively, these data show that loss of epidermal Ovol1 biases the skin’s response to IMQ toward elevated neutrophil accumulation but reduced T cell abundance.

Ovol1 loss results in elevated Il33 expression in inflamed skin, and inhibition of IL-33 signaling aggravates the IMQ-induced skin phenotypes of Ovol1 SSKO mice

IL-33, a cytokine of the IL-1 family that is expressed in barrier tissues, has been identified as a risk factor and modulator of psoriatic inflammation (Balato et al., 2012; Duan et al., 2019; Griesenauer and Paczesny, 2017; Pichery et al., 2012). To seek the potential targets of Ovol1 in the epidermis of inflamed skin, we first considered Il33 as a candidate because recent reports show that OVOL1 depletion in normal human epidermal KCs induces IL33 expression (Tsuji et al., 2020). We found that both knockdown of OVOL1 in normal human epidermal KCs and adenovirus Cre-mediated acute knockout of Ovol1 in primary mouse KCs derived from Ovol1f/f mice resulted in elevated IL33/Il33 expression (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S3a). Thus, similar to OVOL1 in humans, Ovol1 is capable of suppressing Il33 expression in mouse epidermal cells.

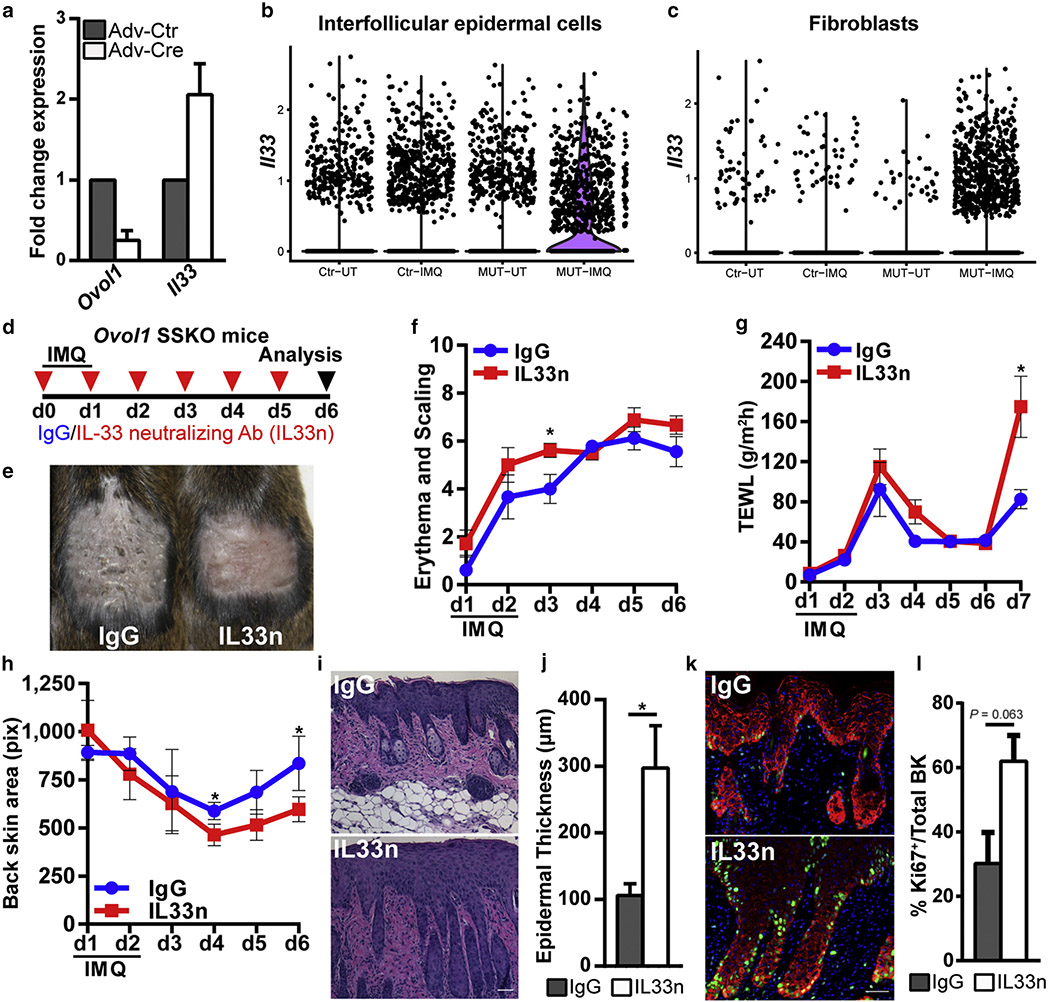

Figure 3. Expression and function of Il33 in Ovol1-deficient skin.

(a) RT-qPCR analysis on primary mouse keratinocytes derived from Ovol1f/f mice and infected with Adv-Ctr or Adv-Cre. Results from a single experiment are shown but are representative of three independent experiments. (b, c) Violin plots showing the expression of 1l33 in (b) interfollicular epidermal cells or (c) fibroblasts from scRNA-seq datasets (Sun et al., 2021). (d) The design of experiments for IL-33–neutralizing Ab (IL33n) or IgG control on Ovol1 SSKO mice in e–l. (e) The external appearance of the skin on d6. (f–h) Time courses showing (f) phenotype progression, (g) TEWL measurements, and (h) treated back skin area (using the images in Supplementary Figure S3e). (i) Skin histology and (j) quantification of epidermal thickness on d6. Bar = 50 μm. (k) Immunofluorescence and (l) quantification of proliferative basal (Ki-67+K14+) cells on d6. n = 3 pairs of IgG- and IL33n-treated Ovol1 SSKO mice. * P < 0.05. Error bars represent (a, g, j, l) mean ± SD and (f, h) SEM. Ab, antibody; Adv-Cre, Cre-expressing adenovirus; Adv-Ctr, control adenovirus; BK, basal keratinocytes; d, day; IMQ, imiquimod; K, keratin; MUT, mutant; pix, pixel; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; SSKO, skin epithelia–specific knockout; TEWL, transepidermal water loss; UT, untreated; Ctr, control.

Next, we asked whether the loss of Ovol1 alters Il33 expression in vivo. Interrogation of our previously published RNA-sequencing data on control and Ovol1−/− epidermis 6 hours after IMQ treatment (Sun et al., 2021) revealed elevated Il33 expression in the epidermis from Ovol1−/− mice (×3.2, P < 10−5). Having said this, RT-qPCR showed only a statistically nonsignificant increase for Il33 expression in IMQ-treated Ovol1−/− epidermis, whereas the increased expression of Il1a was significant (Supplementary Figure S3b). We also analyzed our published single-cell RNA-sequencing data on control and Ovol1−/− mice 24 hours after IMQ treatment (Sun et al., 2021). In the inter-follicular epidermis, Il33 was found to be predominantly expressed by basal KCs, and the number of Il33-expressing basal cells increased in the mutant after IMQ treatment compared with that in the control (Figure 3b and Supplementary Figure S3c-e). Moreover, control fibroblasts rarely showed detectable Il33 expression, but fibroblasts from Ovol1−/− mice became Il33-positive after IMQ treatment (Figure 3c). Finally, RT-qPCR on RNAs isolated from the whole skin of control and Ovol1 SSKO mice revealed potential increases 6 hours and 2–3 days as well as a statistically significant increase 6 days after IMQ treatment for Il33 expression (Kakkar and Lee, 2008) (Supplementary Figure S3f). Taken together, these results suggest that epidermal loss of Ovol1 results in mildly elevated expression of Il33 in the epidermis but remarkably increased expression in the dermis of inflamed skin.

To investigate the effect of excessive Il33 expression in the psoriasis-like microenvironment of IMQ-treated Ovol1-deficient mice, we intraperitoneally injected Ovol1 SSKO mice with either IgG control or an IL-33-neutralizing antibody (Byrne et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016; Ohno et al., 2011; Peng et al., 2018; Schmitz et al., 2005) before and every day succeeding two IMQ applications (Figure 3d). Interestingly, neutralization of IL-33 signaling led to more severe skin defects characterized by exacerbated erythema and scaling, enhanced epidermal barrier disruption, and apparent contraction of the IMQ-treated skin area (Figure 3e-h and Supplementary Figure S3g-i). Consistent with enhanced epidermal hyperplasia at a histological level (Figure 3i and j), Ki-67 immunostaining trended toward elevated proliferative activity in the epidermal basal layer, including cells lining the finger-like projections (Figure 3k and l). However, the expression of keratin 1 and loricrin appeared unchanged (Supplementary Figure S3j and k), suggesting that the process of epidermal terminal differentiation is not affected by IL-33 neutralization. Despite previous reports of IL-33’s effects on immune cell populations such as Tregs and neutrophils in other inflammatory models (Enoksson et al., 2013; Griesenauer and Paczesny, 2017; Lan et al., 2016; Matta et al., 2014), we did not detect any statistically significant change in nonlymphocytes and various T cell populations (including Tregs) after IL-33 neutralization in our model (Supplementary Figure S3l-p). Collectively, these data suggest that the upregulated expression of Il33 in Ovol1 SSKO skin functions to suppress rather than enhance the IMQ-induced skin phenotypes and epidermal hyperplasia.

Identification of an Ovol1–Cxcl1–neutrophil regulatory axis that enhances IMQ-induced skin inflammation in Ovol1 SSKO mice

To seek additional candidate targets that mediate the enhanced inflammation in Ovol1-deficient skin, we returned to the RNA-sequencing data on IMQ-treated Ovol1−/− and control epidermis (Sun et al., 2021), this time focusing on the chemokines known to be involved in neutrophil recruitment. We found Cxcl1 (×2.1), Cxcl2 (×3.0), and Cxcl3 (×3.1) to be significantly increased in IMQ-treated Ovol1−/− epidermis (P < 10−6). RT-qPCR analysis using independent samples confirmed the increased expression of Cxcl1 in Ovol1−/− epidermis both 6 and 24 hours after IMQ treatment, with the upregulation being more dramatic and statistically significant at 24 hours (Figure 4a and b). A possible increase in Cxcl3 expression was also observed (Figure 4b).

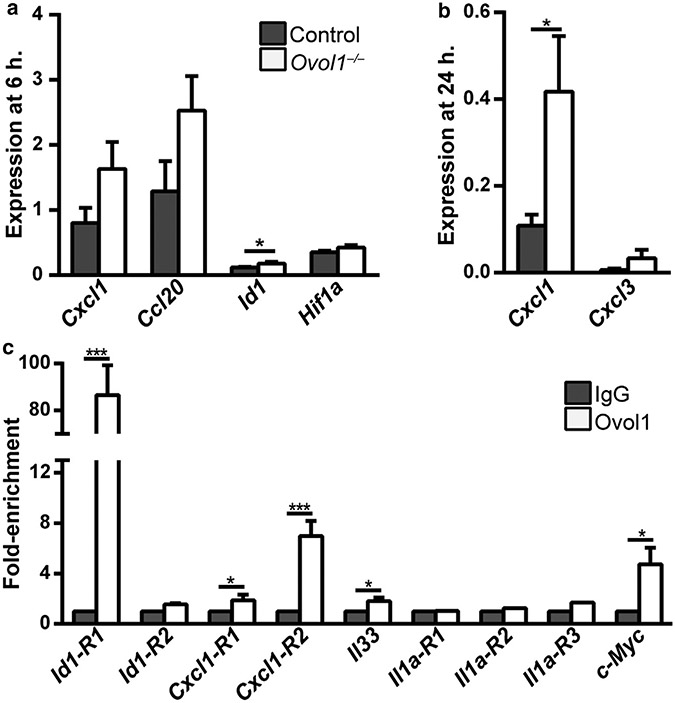

Figure 4. Molecular analysis of OVOL1 targets in the epidermis.

(a, b) RT-qPCR analysis at (a) 6 and (b) 24 h after IMQ treatment. n = 5 for Ovol1−/− and 4 for control littermates in a; note that two pairs of these mice were also used for RNA-seq analysis. n = 5 pairs in b. (c) ChIP-qPCR for the indicated genes in epidermal cells isolated from 2–6 h post-IMQ–treated adult skin. IgG control values were normalized to 1 for all. Results are summarized from one to four independent experiments. *** P < 0.005; * P < 0.05. P-values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s paired t-test. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. ChIP-qPCR, chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with real-time qPCR; h, hour; IMQ, imiquimod; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

Ovol1 encodes a transcriptional repressor (Nair et al., 2007, 2006). Thus, genes that were upregulated in its absence might be direct Ovol1 targets. Indeed, the Cxcl1 gene but not Cxcl2/3 contains OVOL1-binding consensus motifs (CCGTTA) (Nair et al., 2007) at two different regions (R1, −3505 to −3411; R2, +1262 − +1355). To validate Ovol1 binding, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with real-time qPCR on epidermal cells isolated from wild-type mice 2–6 hours after IMQ treatment. Chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with real-time qPCR revealed strong Ovol1 binding to the promoter of a known Ovol1 target, Id1 (Renaud et al., 2015), at −1073 to −997 (R1) but not at another site (R2, +1269 − +1368) (Figure 4c). Binding to another known Ovol1 target, c-Myc (Nair et al., 2006), was also detected. Importantly, chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with real-time qPCR revealed Ovol1 binding to the Cxcl1 gene at both predicted sites (Figure 4c). Weak but statistically significant Ovol1 enrichment was also detected upstream of the Il33 promoter at a region (−1986 to −1903) that contains an Ovol1-binding consensus motif. In contrast, no enrichment was seen for Il1a at three different regions (R1–R3). These results suggest that Cxcl1 is a strong candidate as a direct Ovol1 target in skin epidermis, whereas Il33 and Il1a are likely weakly or indirectly regulated by Ovol1.

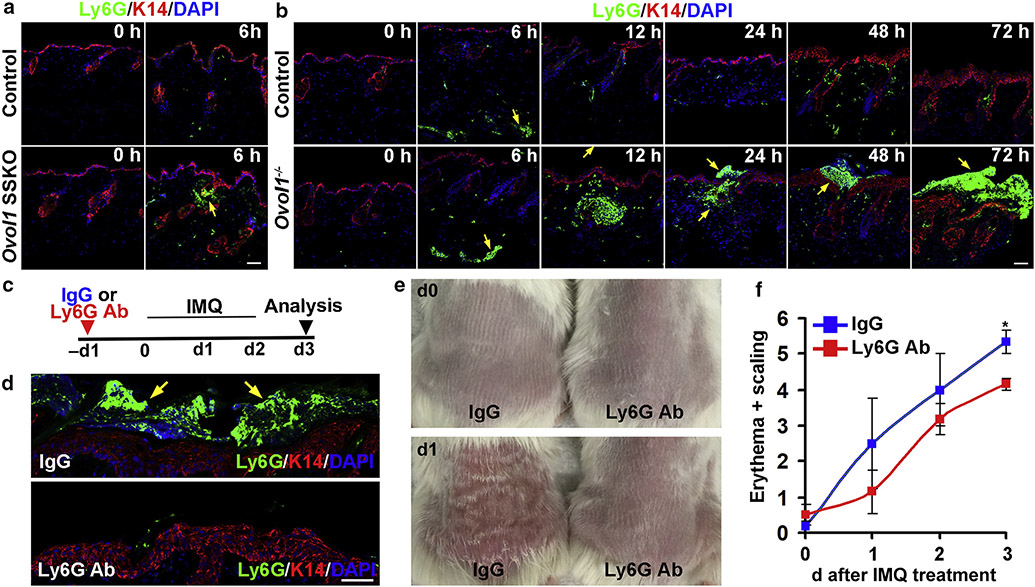

The identification of Cxcl1 as a potential Ovol1 target led us to look more closely at neutrophil dynamics in inflamed skin with Ovol1 ablation. At 6 hours after the first IMQ application, sizable neutrophil clusters (Ly6G positive) were already formed in Ovol1 SSKO skin near the epidermis but were lacking in control littermates (Figure 5a). In Ovol1−/− mice, neutrophils were detected in the dermis 6 hours after IMQ treatment, whereas visible large neutrophil aggregates were observed 12–72 hours after IMQ at locations near, across, and atop the epidermis (Figure 5b). At all time points examined, only scattered neutrophils were detected around the epidermis of control counterparts (Figure 5b). These data provide evidence that loss of Ovol1 in the epidermis results in increased neutrophil accumulation, trafficking, and abscess formation near the epidermis of IMQ-treated skin.

Figure 5. Ovol1 loss alters neutrophil dynamics, and neutrophil depletion rescues psoriasis-like phenotypes in Ovol1−/− skin.

(a, b) Shown are representative images of immunostaining in (a) Ovol1 SSKO and (b) Ovol1−/− mice. (a, b, d) Arrows point to neutrophils. (c) Design of neutrophil depletion experiments in d–f. IgG was used as a control. (d) Immunostaining on d3. (a, b) Bar = 50 μm and (d) Bar = 100 μm. (e) External appearance and (f) phenotypic score (n = 3) at the respective times. *P < 0.05. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Ab, antibody; d, day; h, hour; IMQ, imiquimod; K, keratin; SSKO, skin epithelia–specific knockout.

To assess the functional contribution of neutrophils to IMQ-induced skin pathology of Ovol1-deficient mice, we depleted neutrophils using a neutralizing antibody against Ly6G (Daley et al., 2008) (Figure 5c). Both immunostaining and histological analysis revealed a reduced presence of neutrophils in IMQ-treated Ovol1−/− skin after Ly6G antibody injection relative to that after IgG injection (Figure 5d and Supplementary Figure S4a). Epidermal thickness and the number of Ki-67–positive basal cells were not significantly different between IgG- and Ly6G antibody–injected skin at the endpoint of these experiments (day 3 after IMQ treatment) (Supplementary Figure S4b and c). However, external symptoms such as erythema and scaling/plaque formation in Ovol1−/− mice were significantly improved by Ly6G antibody injection (Figure 5e and f and Supplementary Figure S4d). These effects show that the accumulated neutrophils in Ovol1-deficient skin functionally contribute to IMQ-induced erythema and scaling/plaque formation.

DISCUSSION

Our work unravels previously unknown mechanisms by which an epidermal KC-intrinsic transcription factor modulates innate and adaptive immune responses in the skin in tandem with barrier maintenance. When the skin is chemically challenged or mechanically disrupted, Ovol1 helps to maintain a functional barrier to protect from such perturbations. It likely does so by regulating the proliferation and differentiation of epidermal cells by repressing the expression of genes such as Ovol1, c-Myc (Nair et al., 2007), Ovol2 (Teng et al., 2007), Flg(Tsuji et al., 2017), and Id1 (this work). Importantly, our work identifies a role for epidermally expressed Ovol1 to directly and indirectly regulate the expression of cytokines and chemokines such as Il1a, Il33, and Cxcl1, thereby modulating the ensuing immune response.

Interestingly, the epidermal hyperplasia in IMQ-treated Ovol1 SSKO mice appeared more severe than that in IMQ-treated Ovol1−/− mice (Sun et al., 2021). Moreover, neutrophil accumulation kinetics appears more rapid in Ovol1 SSKO skin than in Ovol1−/− skin. It is possible that this is due to differential IMQ responses of B6 versus of CD1 backgrounds (Swindell et al., 2017, 2011). Alternatively, non-epidermal cells in Ovol1−/− mice might play a modulatory role in the IMQ responses. In human psoriatic skin, neutrophils infiltrate into the dermis from blood vessels at the early inflammatory phase and migrate into the epidermis at the chronic phase of psoriasis (Albanesi et al., 2010). Neutrophil dynamics in inflamed tissues beyond neutrophil–vasculature interactions is an emerging area of research, and swarm-like migration patterns, termed neutrophil swarming, have been described in various tissue and disease contexts (Kienle and Lämmermann, 2016). The slower neutrophil kinetics in the Ovol1−/− model enabled our discovery that initial dermal infiltration of neutrophils does not depend on Ovol1, whereas Ovol1 loss primarily affects the accumulation of neutrophils near or at the epidermis and the migration through the epidermis to form abscesses with KCs. Our data suggest that Ovol1 expression in the epidermis constitutes a protective mechanism that prevents epidermal-proximal neutrophil accumulation and abscess formation in inflamed skin. Combined with our previous study (Sun et al., 2021), we propose that Ovol1 does so by direct transcriptional repression of Cxcl1 expression in KCs and by maintaining a robust barrier, which in turn suppresses KC expression of Il1a (Rider et al., 2011; Sawant et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2021). Although a possibility for this type of regulation was suggested (Hwang et al., 2011), to our knowledge, this study presents a previously unreported example of an epidermally expressed transcription factor modulating neutrophil behaviors in skin inflammation through direct target gene regulation.

Previous studies predominantly suggest a pro-inflammatory role of IL-33 in psoriasis (Balato et al., 2014; Duan et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2010; Sehat et al., 2018; Theoharides et al., 2010). However, it was recently reported that the introduction of recombinant IL-33 suppresses psoriatic inflammation and epidermal hyperplasia (Chen et al., 2020). Our results are consistent with this notion and suggest a protective role for IL-33 in the Ovol1-deficient mouse model against IMQ responses. It is possible that this protective function only manifests when the amount of IL-33 is excessive. IL-33 is an alarmin that can function both as a traditional cytokine (through receptor signaling) and as a nuclear transcriptional regulator (Haraldsen et al., 2009). Our antibody neutralization data implicate the signaling function of IL-33 in suppressing IMQ responses when Ovol1 and barrier are deficient. In other tissues, IL-33 can recruit a particularly suppressive form of Tregs through the ST2 receptor (Halvorsen et al., 2019; Pastille et al., 2019; Siede et al., 2016). However, despite a trending increase of Tregs in Ovol1 SSKO mice, after neutralizing IL-33, the total number of Tregs (including the ST2+ subset) did not drastically vary. In this context, the IL-33/ST2 signaling axis may alter cytokine production by Tregs or other immune cells rather than recruiting or inducing Treg proliferation (Hemmers et al., 2021). In T helper type 2 allergic response, IL-33 can induce immune cells to release secreted proteins that induce the proliferation of KCs (Ryu et al., 2015), potentially explaining the epidermal hyperplasia that we observed. Alternatively, KCs in Ovol1-deficient mice may respond directly to excessive IL-33 signals and hyperproliferate because ST2L and pathways such as extracellular signal–regulated kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase are activated by IL-33 (Du et al., 2016). Although future work outside the scope of this study is needed to characterize the downstream cellular and molecular mediators of IL-33 function, our findings identify OVOL1 as an upstream regulator that directly suppresses Il33 expression in mice.

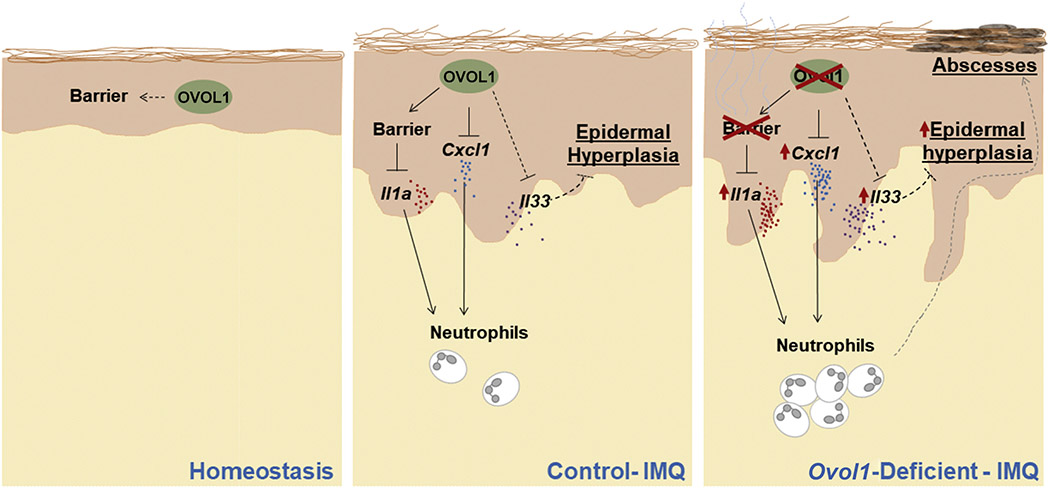

Collectively, this study adds Ovol1 to a growing list of skin barrier-protective transcription factors (Cangkrama et al., 2013; Gordon et al., 2014; Hwang et al., 2011; Koegel et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2013; Segre et al., 1999) but highlights its unique role in the adult epidermis to promote barrier robustness under external challenges in coordination with fine-tuning epidermal–immune cell cross-talk. In an Ovol1-deficient skin microenvironment, both anti-inflammatory (Il33) and proinflammatory (Cxcl1, Il1a, neutrophils) components are upregulated and functionally contribute to skin pathology (Figure 6). These data underscore Ovol1 function as part of a self-limiting, counter-balancing KC-intrinsic mechanism that maintains inflammation competence but at the same time keeps inflammation in check to restore tissue homeostasis. Dissecting the intricate and complex control of psoriasis-like inflammation by epidermal KCs sheds light on our understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis in human patients.

Figure 6. Working model of OVOL1 function in IMQ-induced skin inflammation.

In normal skin treated with IMQ, epidermally expressed Ovol1 not only promotes barrier maintenance, thereby suppressing alarmin (IL-1α) production, but also directly represses the gene expression of Cxcl1 chemokine and possibly Il33 cytokine to modulate the inflammatory and hyperproliferative responses. In Ovol17-deficient skin treated with IMQ, the barrier is disrupted and, Il1a and Cxcl1 are upregulated, resulting in excessive and persistent neutrophil accumulation and exacerbated inflammation. In contrast, Il33 is upregulated likely as a protective mechanism to suppress excessive epidermal hyperplasia. IMQ, imiquimod.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

B6N-Ovol1tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi/J mice, where a cassette composed of an FRT site—a LacZ sequence—and loxP sites are inserted into the Ovol1 locus, were purchased from Knockout Mouse Project Re-pository of the University of California, Davis (Davis, CA). These mice were crossed with B6.Cg-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/J (Rodriguez et al., 2000) mice to generate a floxed (i.e., f) Ovol1 allele. Ovol1+/−; K14-Cre males were crossed with Ovol1f/f females to generate Ovol1 SSKO (Ovol1f/−; K14-Cre) mice, which were then analyzed along with their sex- and weight-matched control litter-mates. Genotyping primers are provided in Supplementary Table Sl. All animal studies have been approved and abide by the regulatory guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Irvine (Irvine, CA).

IMQ-induced psoriasis model

Mice aged 7–8 weeks received a daily topical dose of 62.5 mg 5% IMQ cream (Perrigo, Dublin, Ireland) on shaved backs for 1–5 consecutive days or as indicated. Additional details are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Tape stripping and TEWL measurement

Tape stripping was performed as described in a study by Bruhs et al. (2018). In brief, hairs were removed from the mouse back by shaving. Three days later, shaved back skin was stripped with adhesive cellophane tape 20 times. For each stripping, a fresh piece of tape was lightly pressed onto the back and gently pulled off.

TEWL was measured on shaved mouse back skin using the Delfin VapoMeter (SWL4400, Delfin, Kuopio, Finland) under basal conditions (untapped or untreated), after tape stripping, or after two-time IMQ applications. TEWL values are output as g/m2h.

Flow cytometry

T cells were isolated as described in the study by Ali et al. (2017). Whole skin was digested in 2% collagenase, 0.5 mg/ml hyaluronidase, and 0.1 mg/ml DNase in RPMI with 1% 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 10% fetal calf serum at 37 °C for 45 minutes. Cells were filtered through 70- and 40-μm filters, rinsed in 5% fetal bovine serum/×1PBS, and stained for 10 minutes with Zombie NIR (423105; BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Cells were stained with cell surface markers and anti-mouse CD16/32 (101320; BioLegend) in FACS buffer (5% fetal bovine serum/×1PBS) on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were fixed with the Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (00-5523-00; eBioscience, Waltham, MA), stained for eFluor450 anti-Foxp3 (48-5773-82; eBioscience) for 1 hour at room temperature, and then analyzed on a FACS Aria Fusion. Surface markers include APC anti-CD45 (103112; BioLegend), PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-CD3 (100218; BioLegend), and anti-CD90.2 (140322; BioLegend), FITC anti-CD8a (100705; BioLegend), BV605 anti-CD4 (100548; BioLegend), and phycoerythrin anti-ST2 (145303; BioLegend). Additional details are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with real-time qPCR

The back skin of B6 mice was shaved and treated with IMQ for 2–6 hours. To separate epidermis from dermis, back skin was collected and digested with 2.5 U/ml dispase (07913; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) for 1 hour at 37 °C, scraped, minced, resuspended in 5% fetal bovine serum/×1PBS, and filtered through 70-μm and 40-μm filters. Epidermal cells in single-cell suspension were then cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde, followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay using rabbit anti-OVOL1 antibody (Dai et al., 1998) and SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Agarose Beads) (9002; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was then purified, and qPCR was performed using SYBRgreen reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1).

In vivo administration of IL-33-neutralizing and anti-Ly6G antibodies

For IL-33 neutralization experiments, same-sex/same-weight Ovol1 SSKO littermates were intraperitoneally injected with 15 μg of goat anti-mouse IL-33 Affinity Purified Polyclonal antibody (AF3626; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or goat IgG (AB0108-C; R&D Systems) 30 minutes before the two IMQ applications and at the same time of the day for a total of six applications. For neutrophil depletion studies, same-sex/same-weight Ovol1−/− littermates were intraperitoneally injected with 500 μg rat anti-mouse Ly-6G antibody (clone 1A8, eBioscience) or rat IgG2a (clone eBR2a, eBioscience) once 24 hours before IMQ application. In separate control experiments, same-sex/same-weight wild-type littermates were also treated and analyzed. Skin was harvested either 6 days after the first IMQ treatment (IL-33 neutralizing) or 24 hours after the third IMQ treatment (for Ly6G) and was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for H&E staining, embedded in optimum cutting temperature, and frozen for immunostaining, or single cells were isolated for flow cytometry analysis.

Statistics and reproducibility

Nearly all experiments were performed on at least three biological replicates or repeated at least twice. The sample size and number of independent experiments are indicated in the relevant figure legends. Disease pathology scoring was performed blindly. No data were excluded. For analysis of the differences between groups, Student’s unpaired two-tailed t-test was performed in Excel unless otherwise indicated. P-values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant and are indicated in the figures/legends. Those where P-values are not indicated are not statistically significant.

Additional information is provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bogi Andersen for use of the Vapometer and the Institute for Immunology FACS Core Facility at the University of California, Irvine for expert service. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-AR068074 and R01-GM123731 (XD). MD is partially supported by the National Institutes of Health T32 Immunology Research Training Grant (AI 060573). ZC was supported by the China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 201906260233). RV was supported by the National Science Foundation GRFP (DGE-1839285).

Abbreviations:

- IMQ

imiquimod

- KC

keratinocyte

- SSKO

skin epithelia–specific knockout

- TEWL

transepidermal water loss

- Treg

regulatory T cell

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.jidonline.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2021.08.397.

Data availability statement

No datasets were generated during this study. The analysis uses previously published datasets (Sun et al., 2021).

REFERENCES

- Albanesi C, Scarponi C, Bosisio D, Sozzani S, Girolomoni G. Immune functions and recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in psoriasis. Autoimmunity 2010;43:215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander H, Brown S, Danby S, Flohr C. Research techniques made simple: transepidermal water loss measurement as a research tool. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:2295–300.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N, Zirak B, Rodriguez RS, Pauli ML, Truong HA, Lai K, et al. Regulatory T cells in skin facilitate epithelial stem cell differentiation. Cell 2017;169: 1119–29.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balato A, Di Caprio R, Canta L, Mattii M, Lembo S, Raimondo A, et al. IL-33 is regulated by TNF-α in normal and psoriatic skin. Arch Dermatol Res 2014;306:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balato A, Lembo S, Mattii M, Schiattarella M, Marino R, De Paulis A, et al. IL-33 is secreted by psoriatic keratinocytes and induces pro-inflammatory cytokines via keratinocyte and mast cell activation [published correction appears in Exp Dermatol 2012;21:977]. Exp Dermatol 2012;21:892–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barland CO, Zettersten E, Brown BS, Ye J, Elias PM, Ghadially R. Imiquimod-induced interleukin-1 alpha stimulation improves barrier homeostasis in aged murine epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhs A, Proksch E, Schwarz T, Schwarz A. Disruption of the epidermal barrier induces regulatory T cells via IL-33 in mice. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne SN, Beaugie C, O’Sullivan C, Leighton S, Halliday GM. The immune-modulating cytokine and endogenous alarmin interleukin-33 is upregulated in skin exposed to inflammatory UVB radiation. Am J Pathol 2011;179:211–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing γδ T cells in skin inflammation [published correction appears in Immunity 2011;35:649]. Immunity 2011;35:596–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangkrama M, Ting SB, Darido C. Stem cells behind the barrier. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:13670–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Hu Y, Gong Y, Zhang X, Cui L, Chen R, et al. Interleukin-33 alleviates psoriatic inflammation by suppressing the T helper type 17 immune response. Immunology 2020;160:382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CC, Cheng WJ, Korinek M, Lin CY, Hwang TL. Neutrophils in psoriasis. Front Immunol 2019;10:2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Schonbaum C, Degenstein L, Bai W, Mahowald A, Fuchs E. The ovo gene required for cuticle formation and oogenesis in flies is involved in hair formation and spermatogenesis in mice. Genes Dev 1998;12:3452–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol 2008;83:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du HY, Fu HY, Li DN, Qiao Y, Wang QW, Liu W. The expression and regulation of interleukin-33 in human epidermal keratinocytes: a new mediator of atopic dermatitis and its possible signaling pathway. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2016;36:552–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Dong Y, Hu H, Wang Q, Guo S, Fu D, et al. IL-33 contributes to disease severity in psoriasis-like models of mouse. Cytokine 2019;119: 159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoksson M, Möller-Westerberg C, Wicher G, Fallon PG, Forsberg-Nilsson K, Lunderius-Andersson C, et al. Intraperitoneal influx of neutrophils in response to IL-33 is mast cell-dependent. Blood 2013;121:530–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furue K, Ito T, Tsuji G, Ulzii D, Vu YH, Kido-Nakahara M, et al. The IL-13–OVOL1–FLG axis in atopic dermatitis. Immunology 2019;158:281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales KAU, Fuchs E. Skin and its regenerative powers: an alliance between stem cells and their niche. Dev Cell 2017;43:387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon WM, Zeller MD, Klein RH, Swindell WR, Ho H, Espetia F, et al. A GRHL3-regulated repair pathway suppresses immune-mediated epidermal hyperplasia. J Clin Invest 2014;124:5205–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesenauer B, Paczesny S. The ST2/IL-33 axis in immune cells during inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 2017;8:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen EC, Franks SE, Wadsworth BJ, Harbourne BT, Cederberg RA, Steer CA, et al. IL-33 increases ST2 + Tregs and promotes metastatic tumour growth in the lungs in an amphiregulin-dependent manner. Oncoimmunology 2019;8:e1527497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsen G, Balogh J, Pollheimer J, Sponheim J, Küchler AM. Interleukin-33 - cytokine of dual function or novel alarmin? Trends Immunol 2009;30:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden JL, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM. The immunogenetics of psoriasis: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun 2015;64:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmers S, Schizas M, Rudensky AY. T reg cell-intrinsic requirements for ST2 signaling in health and neuroinflammation. J Exp Med 2021;218:e20201234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Kita R, Kwon HS, Choi EH, Lee SH, Udey MC, et al. Epidermal ablation of Dlx3 is linked to IL-17-associated skin inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:11566–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008;7:827–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienle K, Lämmermann T. Neutrophil swarming: an essential process of the neutrophil tissue response. Immunol Rev 2016;273:76–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Naik S, Nagao K. Choreographing immunity in the skin epithelial barrier. Immunity 2019;50:552–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel H, von Tobel L, Schäfer M, Alberti S, Kremmer E, Mauch C, et al. Loss of serum response factor in keratinocytes results in hyperproliferative skin disease in mice. J Clin Invest 2009;119:899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan F, Yuan B, Liu T, Luo X, Huang P, Liu Y, et al. Interleukin-33 facilitates neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in S. aureus-caused peritonitis. Mol Immunol 2016;72:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Villarreal-Ponce A, Fallahi M, Ovadia J, Sun P, Yu QC, et al. Transcriptional mechanisms link epithelial plasticity to adhesion and differentiation of epidermal progenitor cells. Dev Cell 2014;29:47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Teegarden A, Bauer EM, Choi J, Messaddeq N, Hendrix DA, et al. Transcription factor CTIP1/BCL11A regulates epidermal differentiation and lipid metabolism during skin development. Sci Rep 2017;7:13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Hindes A, Burns CJ, Koppel AC, Kiss A, Yin Y, et al. Serum response factor controls transcriptional network regulating epidermal function and hair follicle morphogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Tai Y, Achanta S, Kaelberer MM, Caceres AI, Shao X, et al. IL-33/ST2 signaling excites sensory neurons and mediates itch response in a mouse model of poison ivy contact allergy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:E7572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta BM, Lott JM, Mathews LR, Liu Q, Rosborough BR, Blazar BR, et al. IL-33 is an unconventional alarmin that stimulates IL-2 secretion by dendritic cells to selectively expand IL-33R/ST2+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2014;193:4010–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Hollenbaugh JA, Zand MS, Holden-Wiltse J, Mosmann TR, Perelson AS, et al. Quantifying the early immune response and adaptive immune response kinetics in mice infected with influenza A virus. J Virol 2010;84:6687–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Asquith DL, Hueber AJ, Anderson LA, Holmes WM, McKenzie AN, et al. Interleukin-33 induces protective effects in adipose tissue inflammation during obesity in mice. Circ Res 2010;107:650–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milora KA, Fu H, Dubaz O, Jensen LE. Unprocessed interleukin-36a regulates psoriasis-like skin inflammation in cooperation with interleukin-1. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:2992–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol 2007;25:524–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair M, Bilanchone V, Ortt K, Sinha S, Dai X. Ovol1 represses its own transcription by competing with transcription activator c-Myb and by recruiting histone deacetylase activity. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:1687–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair M, Teng A, Bilanchone V, Agrawal A, Li B, Dai X. Ovol1 regulates the growth arrest of embryonic epidermal progenitor cells and represses c-myc transcription. J Cell Biol 2006;173:253–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno T, Oboki K, Morita H, Kajiwara N, Arae K, Tanaka S, et al. Paracrine IL-33 stimulation enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated macrophage activation. PLoS One 2011;6:e18404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaru F, Jensen LE. Staphylococcus aureus stimulates neutrophil targeting chemokine expression in keratinocytes through an autocrine IL-1alpha signaling loop. J Invest Dermatol 2010;130:1866–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasparakis M, Haase I, Nestle FO. Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastille E, Wasmer MH, Adamczyk A, Vu VP, Mager LF, Phuong NNT, et al. The IL-33/ST2 pathway shapes the regulatory T cell phenotype to promote intestinal cancer. Mucosal Immunol 2019;12:990–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G, Mu Z, Cui L, Liu P, Wang Y, Wu W, et al. Anti-IL-33 antibody has a therapeutic effect in an atopic dermatitis murine model induced by 2, 4-dinitrochlorobenzene. Inflammation 2018;41:154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichery M, Mirey E, Mercier P, Lefrancais E, Dujardin A, Ortega N, et al. Endogenous IL-33 is highly expressed in mouse epithelial barrier tissues, lymphoid organs, brain, embryos, and inflamed tissues: in situ analysis using a novel Il-33-LacZ gene trap reporter strain. J Immunol 2012;188:3488–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. The primary histologic lesion of seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 1966;46:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud SJ, Chakraborty D, Mason CW, Rumi MA, Vivian JL, Soares MJ. OVO-like 1 regulates progenitor cell fate in human trophoblast development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:E6175–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider P, Carmi Y, Guttman O, Braiman A, Cohen I, Voronov E, et al. IL-1α and IL-1 β recruit different myeloid cells and promote different stages of sterile inflammation. J Immunol 2011;187:4835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring J, Möhrenschlager M, Weidinger S. Molecular genetics of atopic eczema. Chem Immunol Allergy 2012;96:24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez CI, Buchholz F, Galloway J, Sequerra R, Kasper J, Ayala R, et al. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet 2000;25:139–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu WI, Lee H, Kim JH, Bae HC, Ryu HJ, Son SW. IL-33 induces Egr-1-dependent TSLP expression via the MAPK pathways in human keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol 2015;24:857–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant KV, Xu R, Cox R, Hawkins H, Sbrana E, Kolli D, et al. Chemokine CXCL1-mediated neutrophil trafficking in the lung: role of CXCR2 activation. J Innate Immun 2015;7:647–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity 2005;23:479–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuth M, Blunder S, Dubrac S, Gruber R, Moosbrugger-Martinz V. Epidermal barrier in hereditary ichthyoses, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2015;13:1119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre JA. Epidermal barrier formation and recovery in skin disorders. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre JA, Bauer C, Fuchs E. Klf4 is a transcription factor required for establishing the barrier function of the skin. Nat Genet 1999;22:356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehat M, Talaei R, Dadgostar E, Nikoueinejad H, Akbari H. Evaluating serum levels of IL-33, IL-36, IL-37 and gene expression of IL-37 in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;17:179–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siede J, Fröhlich A, Datsi A, Hegazy AN, Varga DV, Holecska V, et al. IL-33 receptor-expressing regulatory T cells are highly activated, Th2 biased and suppress CD4 T cell proliferation through IL-10 and TGFb Release. PLoS One 2016;11:e0161507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida H, Yanagida K, Kita Y, Abe J, Matsushima K, Nakamura M, et al. Interplay between CXCR2 and BLT1 facilitates neutrophil infiltration and resultant keratinocyte activation in a murine model of imiquimod-induced psoriasis. J Immunol 2014;192:4361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Vu R, Dragan M, Haensel D, Gutierrez G, Nguyen Q, et al. OVOL1 regulates psoriasis-like skin inflammation and epidermal hyperplasia. J Invest Dermatol 2021;141:1542–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR, Johnston A, Carbajal S, Han G, Wohn C, Lu J, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of five mouse models identifies similarities and differences with human psoriasis. PLoS One 2011;6:e18266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR, Michaels KA, Sutter AJ, Diaconu D, Fritz Y, Xing X, et al. Imiquimod has strain-dependent effects in mice and does not uniquely model human psoriasis. Genome Med 2017;9:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng A, Nair M, Wells J, Segre JA, Dai X. Strain-dependent perinatal lethality of Ovol1-deficient mice and identification of Ovol2 as a downstream target of Ovol1 in skin epidermis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007;1772:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides TC, Zhang B, Kempuraj D, Tagen M, Vasiadi M, Angelidou A, et al. IL-33 augments substance P-induced VEGF secretion from human mast cells and is increased in psoriatic skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:4448–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigelaar RE, Lewis JM, Bergstresser PR. TCR damma/delta+ dendritic epidermal T cells as constituents of skin-associated lymphoid tissue. J Invest Dermatol 1990;94(Suppl. 6):58S–63S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji G, Hashimoto-Hachiya A, Kiyomatsu-Oda M, Takemura M, Ohno F, Ito T, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation restores filaggrin expression via OVOL1 in atopic dermatitis. Cell Death Dis 2017;8:e2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji G, Hashimoto-Hachiya A, Yen VH, Miake S, Takemura M, Mitamura Y, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation downregulates IL-33 expression in keratinocytes via Ovo-like 1. J Clin Med 2020;9:891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe-Herranz M, Lian LH, Hooper KM, Milora KA, Jensen LE. IL-1R1 signaling facilitates Munro’s microabscess formation in psoriasiform imiquimod-induced skin inflammation. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:1541–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman JSA, Kant M, Boon L, Laman JD, et al. Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis. J Immunol 2009;182:5836–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood LC, Jackson SM, Elias PM, Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. Cutaneous barrier perturbation stimulates cytokine production in the epidermis of mice. J Clin Invest 1992;90:482–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yin M, Zhang L. Keratin 6, 16 and 17-critical barrier alarmin molecules skin wounds and psoriasis. Cells 2019;8:807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated during this study. The analysis uses previously published datasets (Sun et al., 2021).