Abstract

Background:

Screening for unhealthy drug use is now recommended for adult primary care patients,1 but primary care providers (PCPs) generally lack the time and knowledge required to screen and deliver an intervention during the medical visit. To address these barriers, we developed a tablet computer-based ‘Substance Use Screening and Intervention Tool (SUSIT)’. Using the SUSIT, patients self-administer screening questionnaires prior to the medical visit, and results are presented to the PCP at the point of care, paired with clinical decision support (CDS) that guides them in providing a brief intervention (BI) for unhealthy drug use.

Methods:

PCPs and their patients with moderate-risk drug use were recruited from primary care and HIV clinics. A pre-post design compared a control ‘screening only’ (SO) period to an intervention ‘SUSIT’ period. Unique patients were enrolled in each period. In both conditions, patients completed screening and identified their drug of most concern (DOMC) before the visit, and completed a questionnaire about BI delivery by the PCP after the visit. In the SUSIT condition only, PCPs received the tablet with the patient’s screening results and CDS. Multilevel models with random intercepts and patients nested within PCPs examined the effect of the SUSIT intervention on PCP delivery of BI.

Results:

20 PCPs and 79 patients (42 SO, 37 SUSIT) participated. Most patients had moderate-risk marijuana use (92.4%), and selected marijuana as the DOMC (68.4%). Moderate-risk use of drugs other than marijuana included cocaine (15.2%), hallucinogens (12.7%), and sedatives (12.7%). Compared to the SO condition, patients in SUSIT had higher odds of receiving any BI for drug use, with an adjusted odds ratio of 11.59 (95% confidence interval: 3.39, 39.25), and received more elements of BI for drug use.

Conclusions:

The SUSIT significantly increased delivery of BI for drug use by PCPs during routine primary care encounters.

Keywords: Unhealthy drug use, substance use disorder, screening, brief intervention, primary care, HIV

INTRODUCTION

Screening for unhealthy drug use is now recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for adult primary care patients.1 Drug use is among the top ten causes of preventable death in the U.S., and deaths caused by drug overdose and alcohol use are now driving decreases in life expectancy in younger and middle-aged Americans.2–4 Substance use appears to be increasing since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to have persistent negative impacts on health.5,6 Of particular concern for primary care providers (PCPs) are patients with ‘moderate-risk’ drug use, who use drugs at hazardous levels but have not developed severe problems related to their use. These patients are at elevated risk for developing a substance use disorder and for experiencing negative health effects including medical complications of drug use, overdose, traumatic injury, and poor treatment of other medical conditions.7–11 Primary care settings offer an opportunity for early identification of moderate-risk drug use, and could provide early intervention to prevent the development of more severe health consequences.

While the USPSTF drug screening recommendation reflects a recent change, alcohol screening in primary care has been a guideline-recommended practice for over two decades.12 Primary care screening for unhealthy alcohol use followed by brief intervention ranks as the third highest prevention priority for adults in the US, and is one of the most cost-effective preventive services.12–17 Nonetheless, screening and brief intervention is rarely incorporated into routine medical care.18–21 Drug screening and interventions face even greater challenges, given the variety of substances included (ranging from cannabis to heroin and non-medical use of prescribed medications), the illegality of the substances used, and greater knowledge deficits on the part of medical providers.22–26

The most prominent barriers to implementing screening and brief intervention counseling for substance use in primary care are the time and knowledge required to screen, conduct a clinical assessment, and deliver a brief intervention (BI) during the brief medical visit.27–36 Recognizing that information technology has the potential to address these barriers, we developed the ‘Substance Use Screening and Intervention Tool (SUSIT)’. The SUSIT addresses time and workflow constraints by having patients complete screening on a tablet computer, prior to the clinical encounter, using validated self-administered screening instruments.37–39 Results are presented to the primary care provider at the point of care, and clinical decision support (CDS) assists the primary care provider in carrying out a BI. CDS has been an effective tool for changing provider behavior to address unhealthy behaviors such as tobacco use,40–42 but it has not been widely applied for counseling on drug use in primary care. The SUSIT was developed for use in adult primary care, and may be particularly useful in practices with increased prevalence of drug use, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis clinics.43–45 The objective of this study was to test the feasibility and effectiveness of a CDS tool for increasing the delivery of brief counseling on drug use by PCPs in adult primary care, including general medicine and HIV clinics.

METHODS

The NYU Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02893514).

Study design, setting, and recruitment

Study design:

A pre-post design compared a ‘screening only’ (SO) period, to an intervention (SUSIT) period. In the SO condition, patients completed screening but no information was communicated to the PCP. In the SUSIT condition, screening was followed by delivery of the SUSIT tablet, (which provided screening results and CDS) to the PCP. In both groups, the content of substance use BI delivered by the PCP was assessed immediately following the medical visit. An individual patient could participate in only one phase (i.e. SO or SUSIT).

Setting:

The study was conducted between January 2017 and July 2019 in adult outpatient clinics of two public hospitals located in lower Manhattan, New York City. The primary site had a general adult medicine primary care clinic and an HIV clinic that participated in both the SO and SUSIT study periods. One HIV clinic from the secondary site was added to augment recruitment of patients in the SUSIT condition only. The participating HIV clinics serve as the primary care location for their patients, handling general medical care in addition to HIV treatment. Visits were scheduled for 20 minutes in the general medicine clinic, and 30 minutes in the HIV clinics. All clinics offered office-based buprenorphine treatment and could refer to addiction treatment programs located at the primary site. The primary site also had one addiction counselor who worked in the general medicine and HIV clinics. In all clinics, screening was completed in the waiting room, and the PCP encounter occurred in a private exam room.

Participants:

Eligible PCPs were faculty providers with at least one direct patient care session in a participating clinic. Of all PCPs invited to participate, one declined due to competing demands. While a total of 27 PCPs enrolled, only 20 had patients who subsequently enrolled in the study, and thus were included in the analysis. Eligible patients were adults (18+) having a PCP in the study, who were fluent in spoken English and screened positive for current (past 3 months) moderate-risk use of at least one drug on the SUSIT screener. Individuals were excluded if they had high-risk use of alcohol or any drug, because BI alone is not sufficient to meaningfully impact severe substance use.46,47 Additional exclusion criteria were participation in formal addiction treatment in past 3 months, pregnancy, and prior enrollment in either phase of the study.

Study Interventions

Screening only (SO) condition (6/12/2017 – 4/20/18):

Patient participants completed the self-administered SUSIT screener. The screener was called a ‘healthy lifestyle survey’, and included substance use screening tools that have been validated for self-administration in primary care patients; the Substance Use Brief Screen (SUBS), followed by a tablet self-administered version of the World Health Organization’s Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).37–39 To increase acceptability to patients, substance use items were presented alongside questions about diet and exercise. PCPs were not informed whether patients enrolled in the study. Because screening was conducted for research purposes only in the SO group, PCPs did not receive the screening results.

SUSIT condition (4/23/18 – 3/30/19):

Patient participants completed the self-administered SUSIT screener, which was identical to that used in the SO condition. After completing the screening questions, they were prompted to view their substance use screening results, which indicated level of risk (low-, moderate-, or high-risk use) for each substance used in the past 3 months, and select their single drug of most concern (DOMC) if they had moderate-risk use of more than one drug. For participants with moderate-risk use of only one drug, that was the only drug that could be selected as the DOMC.

The SUSIT tablet was then transferred to the patient’s PCP immediately before the primary care encounter. Research staff minimized contact with the PCP by leaving the tablet in or outside the exam room, and did not discuss patients with the PCP. The opening screen of the tablet indicated the patient’s DOMC, and subsequent screens contained a summary of substance use screening information for each substance (including tobacco and alcohol, as well as each drug class), and brief advice tailored to the patient’s DOMC. The CDS was based on the Brief Negotiated Interview,48 which assists providers in conducting a brief (3–5 minute) intervention by guiding them through raising the subject, providing feedback, enhancing motivation, and negotiating a plan (see Supplement 1).

Study Procedures

PCPs gave written informed consent and took part in two trainings, each 20–30 minutes long. The first training, offered prior to the beginning of the SO phase, was a general introduction to screening and BI for drug use. The second training, offered just before the beginning of the SUSIT phase, focused on use of the SUSIT tablet, including interpreting screening results and using CDS to deliver counseling (for approximately 3–5 minutes) during the medical visit. Those enrolled only for the SUSIT phase received one session, covering material from both trainings. PCPs had the option of participating in a group training or having one-to-one training, depending on their availability. Training was led by the principal investigator (JM), and there was no test of competency. PCPs received no incentive for participating in training, and all completed it.

Adult patients presenting to clinic with a scheduled follow-up appointment with a participating PCP were invited to screen for study eligibility. These patients were consecutively approached in the waiting area by a research assistant (RA), who asked them to give verbal consent to complete a ‘questionnaire about health behavior’. Screening was self- administered on the SUSIT tablet in the waiting area, prior to the PCP visit. The RA offered those who met eligibility criteria participation in the study. Patients who screened ineligible were informed by the RA of the reason for ineligibility. Those with high-risk alcohol/drug use were offered a printed handout describing addiction treatment resources located at the main study hospital, and were recommended to speak with the clinic social worker or addiction counselor. For the SUSIT condition, consent for study participation included sharing screening results with the PCP. Following the PCP visit, patients met with the RA to complete the baseline assessments described below, and received a $20 cash payment.

Measures

Exit survey to assess brief intervention.

Following the PCP visit, the first assessment completed by patient participants was a self-administered 17-item exit survey to assess whether any discussion of drug, alcohol, or tobacco use occurred, and whether specific elements of a BI for drug use were delivered (See Supplement 2 for the instrument). Patient questionnaires conducted at the point of service are considered to be the optimal non-observational method for measuring provider delivery of outpatient treatment.49,50 Our exit survey was adapted from the brief patient-reported measurement tool for the assessment of provider delivery of tobacco treatment.51 Responses indicating that at least one element of a BI for drugs was done by the PCP were classified as having received BI; discussion of drug use alone did not count as BI.

Substance use measures.

Prior to the PCP encounter, patient participants self-administered the ASSIST, modified to include non-medical use of prescription sedatives, opioids, and stimulants.38,39 The ASSIST provided measures of current (past 3 months) use and of moderate-risk use (based on standard cutoff scores of 4–26 for drugs, 11–26 for alcohol). The DOMC was selected by the patient from the list of drugs (not including tobacco or alcohol) for which they had ASSIST scores indicating moderate-risk use. After the PCP encounter, the RA administered the Short Inventory of Problems for alcohol and drugs (SIP and SIP-DU), for which any score of 1+ indicated current problem use.52

Other measures.

PCPs self-completed a demographic questionnaire at baseline. Patients completed additional questionnaires, administered by the RA after the PCP encounter, to measure: demographics; depression (score 9+ on the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8)53; and anxiety (score 9+ on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7).54

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for PCP and patient characteristics. Differences between patients in the SO vs. SUSIT condition were tested using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. For analysis of the primary outcome, which is measured at the patient level, we first examined whether any BI occurred during the PCP encounter, based on the exit survey. For additional descriptive information, we counted the number of BNI elements received. Multilevel logistic regression55–58 with a random intercept and patients nested within primary care providers examined the effect of the SUSIT intervention on PCP delivery of BI. The key explanatory variable was treatment condition (SUSIT vs. SO). When the fixed effect of treatment condition is exponentiated, this coefficient indicates how the odds of receiving BI are multiplied when an individual receives the SUSIT condition rather than screening only. Because the type of DOMC was anticipated to be related to delivery of BI, the model was adjusted for DOMC type (marijuana vs. other drug).

RESULTS

Characteristics of participating PCPs (Table 1) are consistent with the characteristics of providers in the academic public clinics from which they were recruited. Two-thirds were specialized in general internal medicine, and others were specialized in HIV or infectious disease. On average, PCPs had been practicing for 9.7 years post-residency, and the range of experience was broad. In the SUSIT condition, PCPs accepted the SUSIT tablet from research staff at the baseline medical visit for 32 (86.5%) of the participating patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 20 primary care providers (PCPs) having patients enrolled in the study*

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 40.1 (8.1) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 37 [30.0, 62.0] |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (65.0) |

| Male | 7 (35.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 11 (55.0) |

| Asian | 5 (25.0) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2 (10.0) |

| Black/African American | 1 (5.0) |

| Other | 1 (5.0) |

| Medical Specialty | |

| General Internal Medicine | 13 (65.0) |

| Infectious Disease/HIV | 7 (35.0) |

| Years since residency | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.7 (8.5) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 7.5 [1.0, 33.0] |

Seven additional PCPs agreed to participate in the study, but did not have patients enrolled and thus are not included in this analysis.

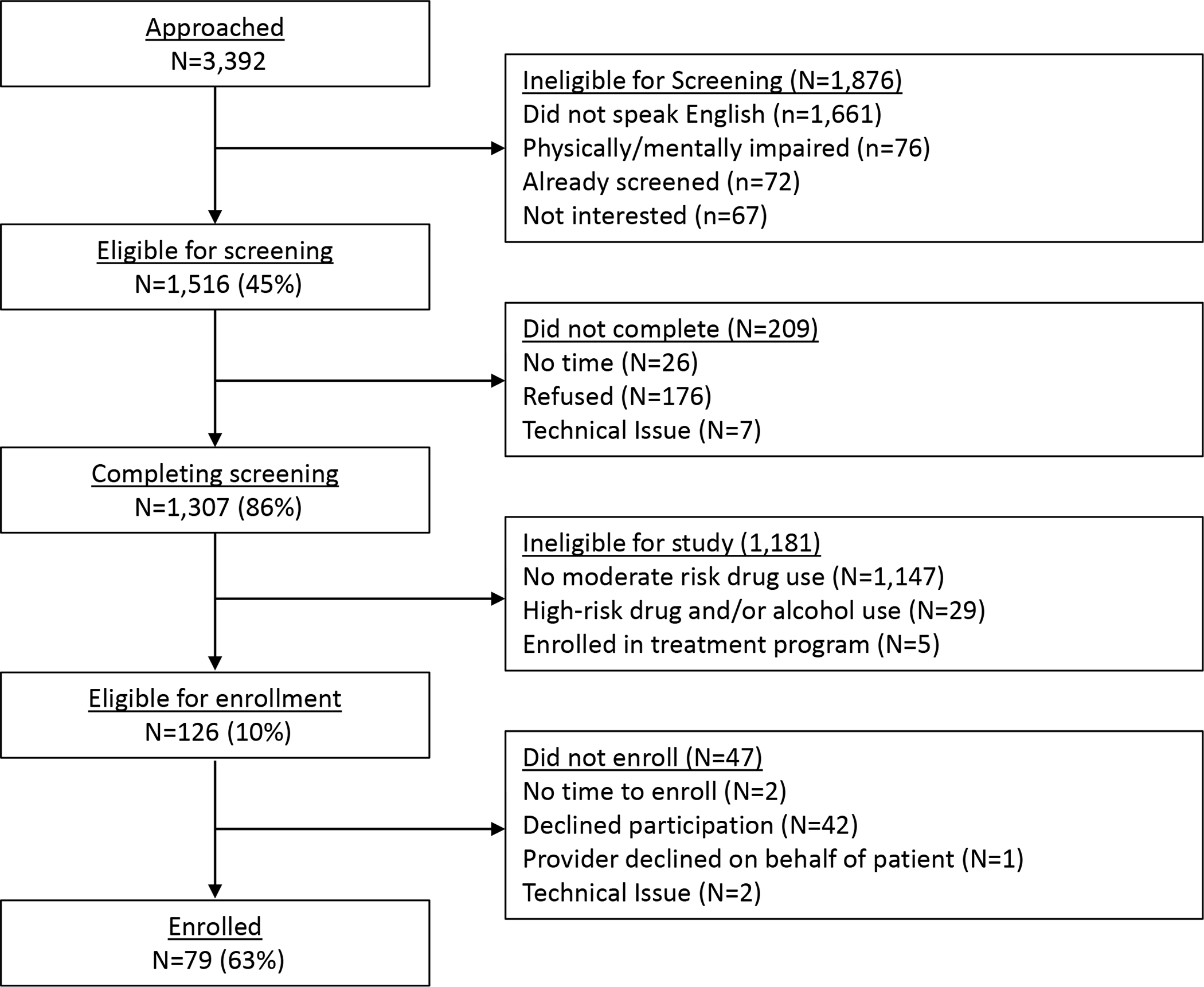

Results of patient recruitment are shown in Figure 1, and participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. In comparison to SO, a higher proportion of patients in the SUSIT condition were recruited from HIV clinics. Reflecting the higher proportion of male patients in the HIV clinics, significantly more males were enrolled in SUSIT (89.2%) than SO (64.3%). Patients had a mean age of 45.4 years, and were racially and ethnically diverse. Patients in the SUSIT condition generally had lower levels of education, and lower rates of anxiety and depression, in comparison to the SO group, but none of these differences were statistically significant.

FIGURE 1.

Study enrollment for patient participants in the SO and SUSIT study conditions

Table 2.

Characteristics of patient participants

| Overall (n=79) | SO (n=42) | SUSIT (n=37) | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Clinic type | 0.163 | |||

| Primary care | 31 (39.2) | 20 (47.6) | 11 (29.7) | |

| HIV | 48 (60.8) | 22 (52.4) | 26 (70.3) | |

| Gender | 0.006 | |||

| Male | 60 (75.9) | 27 (64.3) | 33 (89.2) | |

| Female | 18 (22.8) | 15 (35.7) | 3 (8.1) | |

| Other | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Age | 0.814 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.4 (13.4) | 45.7 (13.8) | 45.0 (13.1) | |

| Median [Min, Max] | 44.0 [20.0, 73.0] | 45.0 [20.0, 70.0] | 43.5 [24.0, 73.0] | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.992 | |||

| Black | 24 (30.4) | 12 (28.6) | 12 (32.4) | |

| White | 15 (19.0) | 7 (16.7) | 8 (21.6) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 28 (35.4) | 15 (35.7) | 13 (35.1) | |

| Other | 6 (7.6) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (8.1) | |

| Missing/Refused | 5 (6.3) | 4 (9.5) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Education | 0.166 | |||

| High school or less | 31 (39.2) | 13 (31.0) | 18 (48.6) | |

| More than high school | 48 (60.8) | 29 (69.0) | 19 (51.4) | |

| Mental health | ||||

| Anxiety (GAD score ≥9) | 15 (19.0) | 10 (23.8) | 5 (13.5) | 0.268 |

| Depression (PHQ-8 score ≥9)2 | 17 (21.5) | 11 (26.2) | 6 (16.2) | 0.345 |

| Moderate-risk Substance Use 3 | ||||

| Tobacco | 35 (44.3) | 22 (52.4) | 13 (35.1) | 0.189 |

| Alcohol | 17 (21.5) | 10 (23.8) | 7 (18.9) | 0.800 |

| Marijuana | 73 (92.4) | 38 (90.5) | 35 (94.6) | 0.792 |

| Inhalants | 13 (16.4) | 3 (7.1) | 10 (27.0) | 0.031 |

| Cocaine | 12 (15.2) | 6 (14.3) | 6 (16.2) | 1.000 |

| Hallucinogens | 10 (12.7) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (13.5) | 1.000 |

| Prescription sedatives | 10 (12.7) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (13.5) | 1.000 |

| Methamphetamine | 8 (10.1) | 3 (7.1) | 5 (13.5) | 0.463 |

| Prescription stimulants | 5 (6.3) | 1 (2.4) | 4(10.8) | 0.182 |

| Heroin | 3 (3.8) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 0.243 |

| Prescription Opioids | 3 (3.8) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.7) | 1.000 |

| >1 drug (excluding tobacco and alcohol) | 30 (38.0) | 14 (33.3) | 16 (43.2) | 0.501 |

| Drug of Most Concern (DOMC) | 0.271 | |||

| Marijuana | 54 (68.4) | 31 (73.8) | 23 (62.2) | |

| Cocaine | 7 (8.9) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (10.8) | |

| Methamphetamine | 6 (7.6) | 2 (4.8) | 4 (10.8) | |

| Heroin | 3 (3.8) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hallucinogens | 4 (5.1) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (8.1) | |

| Inhalants | 4 (5.1) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (8.1) | |

| Sedatives or sleeping pills | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| DOMC Marijuana or Other Drug Type | 0.335 | |||

| Marijuana | 54 (68.4) | 31 (73.8) | 23 (62.2) | |

| Other | 25 (31.6) | 11 (26.2) | 14 (37.8) | |

| Current Problem Use (SIP) | ||||

| Alcohol | 21 (26.6) | 12 (28.6) | 9 (24.3) | 0.800 |

| Drugs | 43 (54.4) | 20 (47.6) | 23 (62.2) | 0.285 |

P-value compares the SO vs. SUSIT group; P<0.05 shown in bold

Assessment missing for one participant

Sums to greater than 100% because some participants had moderate risk of using multiple substances

Most of the sample had moderate-risk marijuana use (92.4%), and a majority selected marijuana as the DOMC (68.4%). Moderate-risk use of drugs other than marijuana included cocaine (15.2%), hallucinogens (12.7%), and prescription sedatives (12.7%). Many participants (38.0%) had moderate-risk use of multiple drugs, and a majority (54.4%) reported drug-related problems on the SIP-DU. Moderate-risk tobacco and alcohol use were also prevalent, but at lower rates than moderate-risk marijuana use.

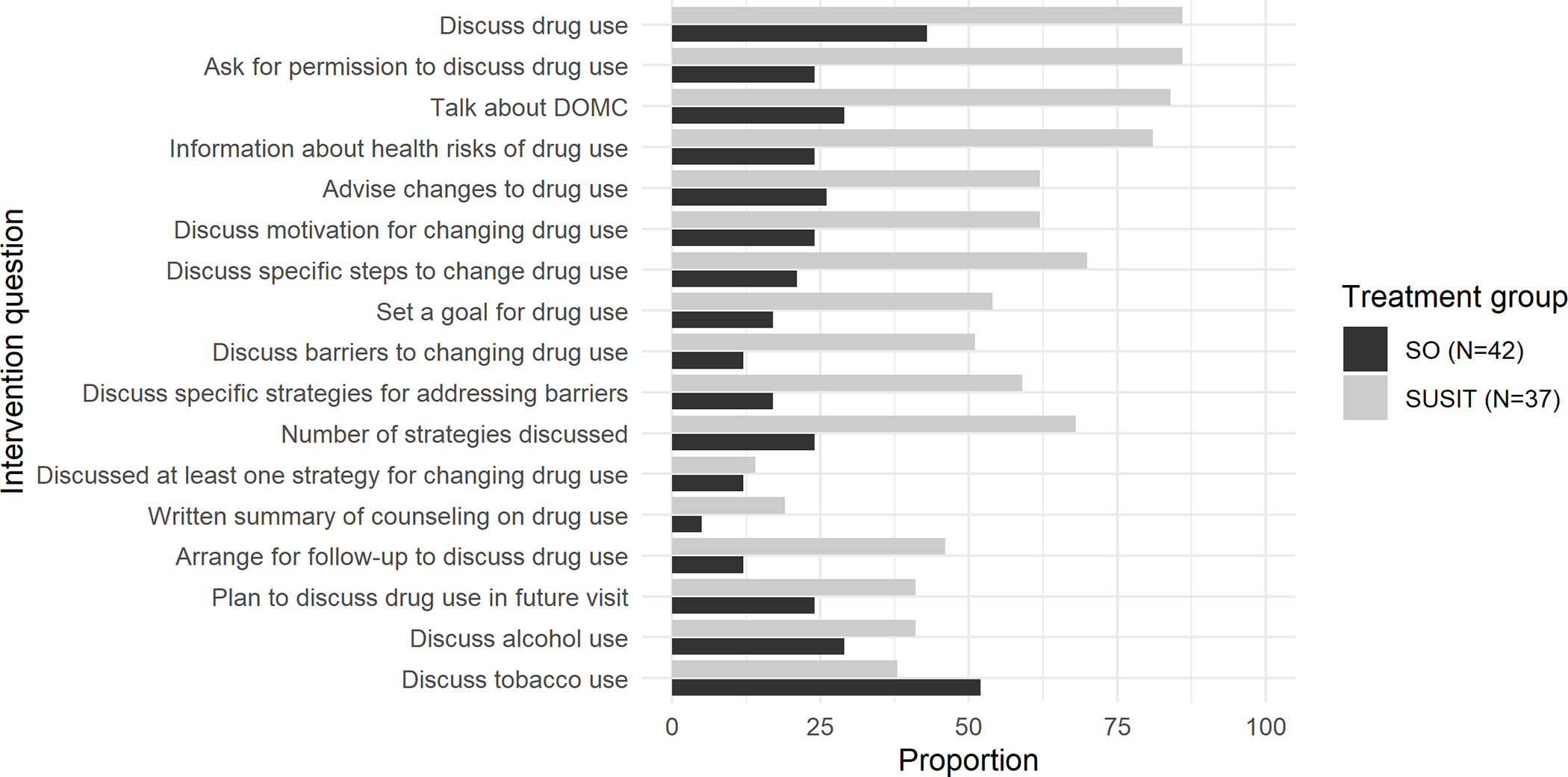

Based on the exit survey, 17 (40.5%) patients in the SO condition received one or more elements of BI for drug use, in comparison to 33 (89.2%) patients in the SUSIT condition. As shown in Table 3, patients in the SUSIT condition had higher odds of receiving BI for drug use, with an adjusted odds ratio of 11.59 (95% confidence interval 3.39, 39.25). SUSIT patients also received more elements of BI (Figure 2). The only counseling element that was delivered more frequently in the SO condition was tobacco counseling, which was reported by 22 (52.3%) of SO patients, and 14 (37.8%) of SUSIT patients. For most items specific to drug use, SUSIT patients reported at least double the rates of BI, in comparison to SO patients.

Table 3.

Receipt of brief intervention for drug use at the baseline visit, reported by patients in the SO (N=42) and SUSIT (N=37) conditions

| SO | SUSIT | |

|---|---|---|

|

Any BI received N (%) |

17 (40.5%)^ | 33 (89.2%)^^ |

|

Odds of receiving any BI Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

Ref | Unadjusted: 11.82 [3.60, 38.47] Adjusted*: 11.59 [3.39, 39.25] |

Model adjusted for drug of most concern (DOMC) being marijuana vs. other drug

In the SO condition, BI was received by 9/20 (45.0%) general medicine patients and by 8/22 (36.4%) HIV patients.

In the SUSIT condition, BI was received by 10/11 (90.9%) general medicine patients and by 23/26 (88.5%) HIV patients

FIGURE 2.

Elements of brief intervention for drug use, and discussion of alcohol or tobacco use by the PCP, as reported by patients in the SO and SUSIT conditions

DISCUSSION

Offering PCPs substance use screening results and decision support significantly increased, by more than 11-fold, their delivery of BI counseling for drug use. This represents a substantial shift in practice. Despite over a decade of concerted efforts to integrate substance use screening and interventions into routine care,59 primary care patients are rarely screened, counseled, or treated for unhealthy alcohol or drug use.2,18–21,60–62 Reflecting this norm, even the PCPs participating in our study, all of whom were practicing in urban public hospital primary care and HIV clinics where drug use is prevalent, discussed drug use with a minority of patients in the usual care (SO) condition.

Changing PCP behavior to provide BI for risky use of alcohol or drugs has proven challenging. In response, special federally funded screening, BI, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) programs have been implemented to address the need for early identification and intervention for substance use in primary care and other medical settings. These programs typically bring in additional clinical staff – often a designated SBIRT health educator – to conduct screening and deliver clinical interventions. Yet SBIRT programs have proven challenging to implement and sustain in the absence of grant funding. In contrast, our technology-assisted SUSIT intervention requires relatively limited resources because it does not require additional clinical providers. However, sustaining and scaling the SUSIT intervention will require an organizational commitment to integrating this system into EHRs and workflows. The high rates of tobacco counseling that we observed, even in the SO condition, reflect electronic health record-embedded best practice alerts and templates for screening and tobacco use treatment, which is prioritized at these clinical sites. The success with tobacco screening and interventions in primary care demonstrates that workflow integration is possible, if the appropriate tools and resources are provided.

The common approach of using specialized staff to conduct brief interventions fails to leverage the knowledge of the PCP or their ongoing relationship with the patient, and may account for the limited effectiveness of BI for drug use in prior studies.63–65 PCP-provided alcohol and tobacco counseling appears more effective than that delivered by other providers.66–68 The PCP is at the center of evidence-based approaches to chronic disease management in primary care, including collaborative care models for depression treatment.69–73 The importance of the PCP-patient relationship appears to hold true for drug use interventions as well; among 3 recent trials of screening and BI for drug use, the only one to demonstrate efficacy tested a model in which PCPs provided the BI.64,65,74,75 By taking full advantage of the existing therapeutic relationship and clinical interactions between the patient and their PCP, the SUSIT-assisted primary care-integrated approach could potentially have greater efficacy for reducing unhealthy drug use, and deserves further study.

Importantly, PCPs in the SUSIT condition were not only more likely to discuss drug use, they also employed more high-level BI skills. While the ‘active ingredients’ of BI have only been studied for alcohol interventions, the existing evidence indicates that giving personalized feedback, presenting options for behavior change, setting specific goals, and discussing strategies for moderation are more likely to lead to reductions in use.76 These elements, such as giving feedback on health risks of drug use, discussing motivation for change, setting goals, and discussing strategies for change and for overcoming barriers, were frequently reported by patients in the SUSIT condition.

It is notable that similar proportions of patients enrolled in the SO and SUSIT groups, even though patients recruited to the SUSIT group knew that screening results would be shared with their PCPs, while patients recruited to the SO group were assured that their results would be kept confidential. Beliefs that patients will not truthfully self-report drug use have been a barrier to implementing screening programs.77,78 Our findings are consistent with prior research indicating that patients can complete self-administered screening and may want to discuss substance use with their PCPs, although they may not be comfortable sharing this information with other clinic staff.79–82

Strengths and Limitations

This study is important because it advances knowledge about the feasibility and quality of drug screening and BI in the context of routine primary care visits. While our sample included PCPs with a broad range of experience, who were recruited from general adult primary care and HIV clinics, all were practicing in urban public hospital sites. Because these practices already have a relatively high awareness of substance use in their patient populations, they could represent a best-case scenario for the delivery of BI. However, it is notable that discussion of drug use and BI occurred infrequently in the SO condition. Because screening results were not shared with PCPs in the SO condition, we cannot know the independent impact of the SUSIT clinical decision support on PCP behavior. Another limitation is that the actual discussions of drug use between PCPs and patients were not recorded, and we do not know how much time was spent delivering BI. Recording visits in the SO condition would have biased our findings by revealing to the PCP that the patient had screened positive for moderate-risk drug use and was enrolled in the study. Instead, we relied on patient exit surveys, which have less information about the content and tone of the interaction, but may be a better reflection of what patients heard and remembered, and thus have the potential to be a better indicator of the type of counseling that could lead to behavior change. With a small sample of patients, a majority of which had marijuana as the DOMC, we cannot adequately explore how PCP counseling differed based on the type of substance used. Finally, our study design does not control for temporal changes. However, there were no major initiatives during this time that focused on increasing screening or interventions for drug or alcohol use. The draft drug use screening recommendation by the USPSTF was not issued until after data collection for our study was complete.

Conclusions

In order for drug screening to positively impact patient health, screening results need to be communicated to PCPs in a way that facilitates brief, focused, motivational discussions of unhealthy drug use with their patients. While more needs to be learned about what primary care interventions are effective for patients with unhealthy drug use, the technology-assisted SUSIT approach may offer a solution for integrating BI for substance use into routine primary care. This strategy warrants further study in a larger sample of patients, and potentially in more diverse primary care settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of the clinical leaders who supported and facilitated this research, including Annie Garment, Gregory Lee, and Andrew Wallach. They further acknowledge those who contributed to the development of the SUSIT tool, including Andre Kushniruk, Devin Mann, Michael Cantor, Barbara Porter, and Sarah Moore. They also wish to thank the many primary care providers and patients of the New York City Health + Hospitals system for participating in the study.

Funding:

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant R34DA040830. NIDA had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: Dr. McNeely reports intellectual property for the ‘Substance Use Screening and Intervention Tool’ that was developed with funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34DA040830) and is in the public domain. Dr. McNeely has served as a consultant to the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Unhealthy Drug Use: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2301–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edlund MJ, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Clinician screening and treatment of alcohol, drug, and mental problems in primary care: results from healthcare for communities. Medical care. 2004;42(12):1158–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czeisler M, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020;69(32):1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr, . Changes in Adult Alcohol Use and Consequences During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA network open. 2020;3(9):e2022942–e2022942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack KA. Drug-induced deaths - United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62(Suppl 3):161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertens JR, Lu YW, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Weisner CM. Medical and psychiatric conditions of alcohol and drug treatment patients in an HMO: comparison with matched controls. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MM, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1242–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, Davis NL. Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Reduce Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1899–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 2014;49(1):66–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(3):301–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Senger CA, et al. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Reduce Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. 2018;320(18):1910–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsen P Brief alcohol intervention--where to from here? Challenges remain for research and practice. Addiction. 2010;105(6):954–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsen P, Aalto M, Bendtsen P, Seppa K. Effectiveness of strategies to implement brief alcohol intervention in primary healthcare. A systematic review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24(1):5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaner E Brief alcohol intervention: time for translational research. Addiction. 2010;105(6):960–961; discussion 964–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Alcohol screening and brief intervention: dissemination strategies for medical practice and public health. Addiction. 2000;95(5):677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris BR, Yu J. Attitudes, perceptions and practice of alcohol and drug screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment: a case study of New York State primary care physicians and non-physician providers. Public Health. 2016;139:70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Back DK, Tammaro E, Lim JK, Wakeman SE. Massachusetts Medical Students Feel Unprepared to Treat Patients with Substance Use Disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):249–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakeman SE, Pham-Kanter G, Donelan K. Attitudes, practices, and preparedness to care for patients with substance use disorder: Results from a survey of general internists. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1–2):23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saitz R, Friedmann PD, Sullivan LM, et al. Professional satisfaction experienced when caring for substance-abusing patients: faculty and resident physician perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):373–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aira M, Kauhanen J, Larivaara P, Rautio P. Factors influencing inquiry about patients’ alcohol consumption by primary health care physicians: qualitative semi-structured interview study. Fam Pract. 2003;20(3):270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson P, Laurant M, Kaner E, Wensing M, Grol R. Engaging general practitioners in the management of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption: results of a meta-analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(2):191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson P, Wojnar M, Jakubczyk A, et al. Managing alcohol problems in general practice in Europe: results from the European ODHIN survey of general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(5):531–539. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu1043. Epub 2014 Jul 1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CASA. Missed Opportunity: National Survey of Primary Care Physicians and Patients on Substance Abuse. New York: The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedmann PD, McCullough D, Saitz R. Screening and intervention for illicit drug abuse: a national survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(2):248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(3):412–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ. Primary care physicians’ views on screening and management of alcohol abuse: inconsistencies with national guidelines. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(11):899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterling S, Kline-Simon AH, Wibbelsman C, Wong A, Weisner C. Screening for adolescent alcohol and drug use in pediatric health-care settings: predictors and implications for practice and policy. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoast RA, Wilford BB, Hayashi SW. Encouraging physicians to screen for and intervene in substance use disorders: obstacles and strategies for change. J Addict Dis. 2008;27(3):77–97. doi: 10.1080/10550880802122687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNeely J, Kumar PC, Rieckmann T, et al. Barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of substance use screening in primary care clinics: a qualitative study of patients, providers, and staff. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNeely J, Strauss SM, Saitz R, et al. A Brief Patient Self-administered Substance Use Screening Tool for Primary Care: Two-site Validation Study of the Substance Use Brief Screen (SUBS). Am J Med. 2015;128(7):784 e789–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar PC, Cleland CM, Gourevitch MN, et al. Accuracy of the Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ACASI ASSIST) for identifying unhealthy substance use and substance use disorders in primary care patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNeely J, Strauss SM, Rotrosen J, Ramautar A, Gourevitch MN. Validation of an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) version of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Addiction. 2016;111(2):233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(12):CD008743. doi: 10.001002/14651858.CD14008743.pub14651852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cresswell K, Majeed A, Bates DW, Sheikh A. Computerised decision support systems for healthcare professionals: an interpretative review. Inform Prim Care. 2012;20(2):115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, Rosenbloom ST, Aronsky D. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(3):311–320. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2555. Epub 2008 Feb 1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Grasso C, et al. Substance use among HIV-infected patients engaged in primary care in the United States: findings from the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems cohort. American journal of public health. 2013;103(8):1457–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sohler NL, Wong MD, Cunningham WE, Cabral H, Drainoni ML, Cunningham CO. Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blair JM, McNaghten AD, Frazier EL, Skarbinski J, Huang P, Heffelfinger JD. Clinical and behavioral characteristics of adults receiving medical care for HIV infection --- Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(11):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saitz R Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: Absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(6):631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Onofrio GP MV; Degutis LC; Fiellin DA; O’Connor P The Yale Brief Negotiated Interview manual. New Haven, CT: Yale University School of Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Silverman CB, et al. Measuring provider adherence to tobacco treatment guidelines: a comparison of electronic medical record review, patient survey, and provider survey. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2005;7 Suppl 1:S35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Smith TF, et al. How valid are medical records and patient questionnaires for physician profiling and health services research? A comparison with direct observation of patients visits. Medical care. 1998;36(6):851–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pbert L, Adams A, Quirk M, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Luippold RS. The patient exit interview as an assessment of physician-delivered smoking intervention: a validation study. Health Psychol. 1999;18(2):183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allensworth-Davies D, Cheng DM, Smith PC, Samet JH, Saitz R. The Short Inventory of Problems-Modified for Drug Use (SIP-DU): validity in a primary care sample. Am J Addict. 2012;21(3):257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of affective disorders. 2009;114(1–3):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCulloch CES SR Generalized, linear, and mixed models. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hox J Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raudenbush SWB AS Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods In: Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences 1. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Connell AAG J; Rogers HJ; Peng CJ Multilevel logistic models for dichotomous and ordinal data. In: Multilevel Modeling of Educational Data. Information Age Publishing, Inc.; 2008:199–242. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rieckmann T, Abraham A, Zwick J, Rasplica C, McCarty D. A Longitudinal Study of State Strategies and Policies to Accelerate Evidence-Based Practices in the Context of Systems Transformation. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1125–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, et al. Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Health Care: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Merrick EL, Hoyt A. Identification and treatment of mental and substance use conditions: health plans strategies. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107(5):957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, et al. Brief Intervention for Problem Drug Use in Safety-Net Primary Care Settings A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(5):492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saitz R, Palfai TPA, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and Brief Intervention for Drug Use in Primary Care The ASPIRE Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(5):502–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Braithwaite RS, Turner BJ, Fiellin DA. A Meta-analysis of the Efficacy of Nonphysician Brief Interventions for Unhealthy Alcohol Use: Implications for the Patient-Centered Medical Home. American Journal on Addictions. 2011;20(4):343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fiore M, United States Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating tobacco use and dependence : 2008 update. Rockville, Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9):645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:484–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G. Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician, and the practice nurse. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(3):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLellan ATS JL; Gordon AJ; Brown R; Ghitza U; Gourevitch MN; Stein J; Oros M; Horton T; Linblad R; McNeely J Can substance use disorders be managed using the chronic care model? Review and recommendations from a NIDA consensus group. Public Health Reviews. 2014;35(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Afifi AA, et al. Project QUIT (Quit Using Drugs Intervention Trial): a randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based multi-component brief intervention to reduce risky drug use. Addiction. 2015;110(11):1777–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Rico MW, et al. A pilot replication of QUIT, a randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for reducing risky drug use, among Latino primary care patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gaume J, McCambridge J, Bertholet N, Daeppen JB. Mechanisms of action of brief alcohol interventions remain largely unknown - a narrative review. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Thomas RM, et al. Factors Underlying Quality Problems with Alcohol Screening Prompted by a Clinical Reminder in Primary Care: A Multi-site Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Local Implementation of Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention at Five Veterans Health Administration Primary Care Clinics: Perspectives of Clinical and Administrative Staff. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spear SE, Shedlin M, Gilberti B, Fiellin M, McNeely J. Feasibility and acceptability of an audio computer-assisted self-interview version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Subst Abus. 2016;37(2):299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McNeely J, Kumar P, Rieckmann T, et al. Barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of substance use screening in primary care clinics: a qualitative study of patients, providers, and staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 2)(83):S128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCormick KA, Cochran NE, Back AL, Merrill JO, Williams EC, Bradley KA. How primary care providers talk to patients about alcohol: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):966–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McNeely J, Adam A, Rotrosen J, et al. Comparison of Methods for Alcohol and Drug Screening in Primary Care Clinics. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(5):e2110721–e2110721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.