Abstract

This study aimed at providing an update of SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology in Douala, the most populated and highly heterogeneous town of Cameroon. A hospital-based cross sectional study was conducted from January to September 2022. A questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic, anthropometric, and clinical data. Retrotranscriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to detect SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal samples. Of the 2354 individuals approached, 420 were included. The mean age of patients was 42.3 ± 14.4 years (range 21 - 82). The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection was 8.1%. The risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 was increased more than seven times in patients aged ≥ 70 years old (aRR = 7.12, p = 0.001), more than six times in married (aRR = 6.60, p = 0.02), more than seven times in those having completed secondary studies (aRR = 7.85, p = 0.02), HIV-positive patients (aRR = 7.64, p < 0.0001) and asthmatic patients (aRR = 7.60, p = 0.003), and more than nine times in those seeking health care regularly (aRR = 9.24, p = 0.001). In contrast, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection was reduced by 86% in patients attending Bonassama hospital (aRR = 0.14, p = 0.04), by 93% in patients of blood group B (aRR = 0.07, p = 0.04), and by 95% in COVID-19 vaccinated participants (aRR = 0.05, p = 0.005). There is need for ongoing surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Cameroon, given the position and importance of Douala.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Prevalence, Determinants, Update, Cameroon

1. Introduction

In December 2019, the first case of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in Hubei Province, China, in a patient presenting with pneumonia-evocating symptoms (WHO, 2020). The disease has spread rapidly across the world in few weeks, inflicting high morbidity and mortality burden (WHO, 2020). COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a positive single strand ribonucleic acid virus, belonging to Coronaviridae family (Safiabadi Tali et al., 2021).

Since March 2020, COVID-19 has been declared as pandemic by the World Health Organization (Safiabadi Tali et al., 2021). Health systems of several countries have been overwhelmed by COVID-19, and this impacted control of other major infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection - HIV (Dongang Nana et al., 2022; Hogan et al., 2020). The virus has a strong cell tropism for respiratory system, with clinical symptomatology mainly represented by respiratory signs, along with gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and neurologic manifestations (Bandeira et al., 2022; Gautret et al., 2020).

As of January 1st, 2023, there were more than 660 million confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases and ∼6.7 million deaths globally (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). COVID-19 is still reported in over 200 countries, with epidemiological patterns varying between countries and modulated by circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants and comorbidities (e.g. obesity, diabetes) (Frühbeck et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). The different regions of world are disproportionally affected by COVID-19, with the highest morbidity and mortality burden in Americas, Asia, and Europe. In contrast, COVID-19 burden is relatively low in most of African countries.

In Cameroon, an estimated ∼124000 cases and ∼2000 deaths were due to COVID-19 till the report of the first case in the country (https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/cm). Government of Cameroon implemented and scaled up several control strategies including lockdown, vaccination, campaigns for behaviour changes (e.g., social distancing, hand washing), and traditional medicine (Titanji, 2020). Current data suggest high circulation of SARS-CoV-2 in some regions of Cameroon, but there is paucity of epidemiological data especially in current context of COVID-19 vaccination (Table 1 ). This study was therefore conducted to provide an update of prevalence, characteristics and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection from nasopharyngeal samples collected between January and September 2022 in Douala, Cameroon.

Table 1.

Previous prospective studies on prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Cameroon.

| Area (Region) | Setting | Population | Symptoms | Period | Diagnostic method | Prevalence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All 10 regions of Cameroon | Health facility | General population (n = 14863) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | March - October 2020 | RT-qPCR | 17.4% | (Tejiokem et al., 2022) |

| Yaounde (Centre) | Health facility | General population (n = 1192) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | Not specified | RT-qPCR | 29.11% | (Fai et al., 2021) |

| Yaounde (Centre) | Health facility | General population (n = 313) | Symptomatic | April - July 2020 | RT-qPCR | 82.5% | (Mbarga Fouda et al., 2021) |

| Yaounde (Centre) | Community | General population (n = 971) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | October - November 2020 | Antibody-based RDT | 3.3% (IgM) and 31.1% (IgG) | (Nwosu et al., 2021) |

| Yaounde (Centre) | Health facility | Health care workers (n = 368) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | January - February 2021 | Antibody-based RDT | 6.79% (IgM) and 17.93% (IgG) | (Nguwoh et al., 2021) |

| Yaounde (Centre) | Community | General population (n = 786 & 1234) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | January -February 2021 & April - May 2021 | Antibody-based RDT | 18.6% & 51.3% | (Ndongo Ateba et al., 2022) |

| Yaounde (Centre) | Health facility | General population (n = 14119) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | April 2020 - January 2021 | RT-qPCR | 12.7% | (Fokam et al., 2022) |

| Douala (Littoral) | Health facility | Blood donors (n = 102) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | September 2020 - April 2021 | RT-qPCR | 11.8% | (Medi et al., 2022) |

| Douala (Littoral) | Health facility | General population (n = 1810) | Not specified | April - May 2021 | RT-qPCR | 1.93% | (Ngaba et al., 2021b) |

| Douala (Littoral) | Health facility | General population (n = 1107) | Not specified | April - May 2021 | RT-qPCR | 1.45% | (Ngaba et al., 2021a) |

| Douala (Littoral) | Health facility | General population (n = 179) | Asymptomatic and symptomatic | January - March 2022 | RT-qPCR | 0% | (Loteri et al., 2022) |

Ig: Immunoglobulin, RT-qPCR: Retrotranscriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction, RDT: Rapid diagnostic test.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

This cross sectional study was carried out at sites of seven health facilities in the town of Douala, Littoral region, Cameroon. Adequate sample size was defined to recruit patients attending the different study sites. Patients were informed about objectives, advantages and risks of the study, and then asked to sign informed consent form before their enrolment. After inclusion, a questionnaire form was administered to each participant to collect data of interest. Nasopharyngeal samples were collected for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2.

2.2. Study period and area

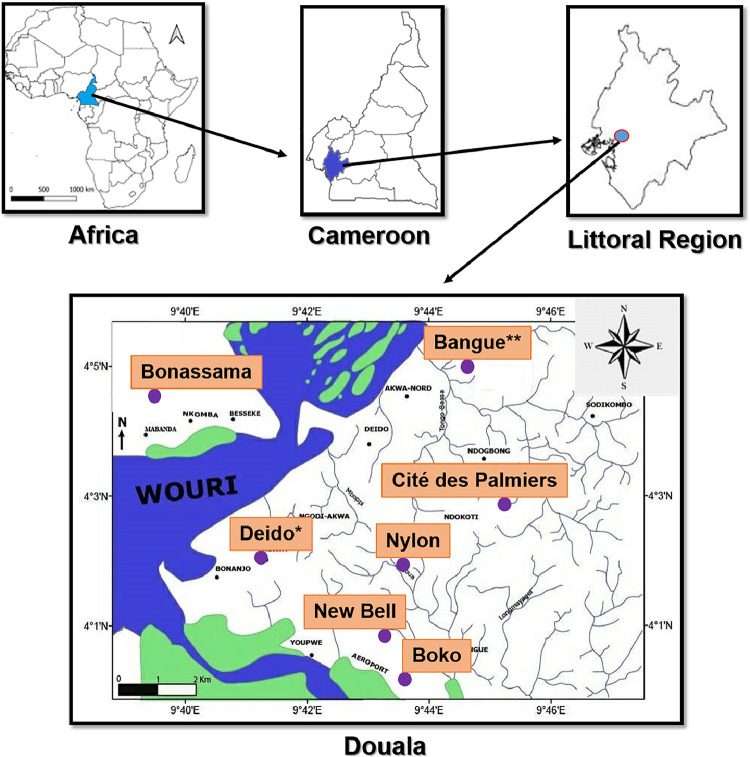

From January to September 2022, patients were recruited at sites of seven health facilities of Douala viz. Bangue district hospital, Boko health care centre, Bonassama district hospital, Cité des Palmiers district hospital, Deido district hospital, New Bell district hospital, and Nylon district hospital (Fig. 1 ). Douala is the economic capital of Cameroon. It is the most populated town in Central Africa, and the main port of entry to foreigners (airport and seaport). Populations living in Douala are highly diverse, with predominance of three ethnic groups (Duala, Bamileke, and Bassa) (Kojom Foko et al., 2021). The first case of COVID-19 in Cameroon was officially reported in Douala on 6th March, 2020 (Mbopi-Keou et al., 2020). Several reasons guided the choice of these health facilities as study sites: i) high frequency of patients attending for different health reasons, ii) sites officially endorsed by the Ministry of Public Health for management of COVID-19 patients, iii) close to multifunctional reference laboratory for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 1.

Map of Douala town depicting study sites.

Map was generated using the ArcGIS v8.1 software (Esri, Redlands, California, USA).

*For Deido district hospital, the sample collection site was located in Bonamoussadi neighbourhood.

**For Bangue district hospital, the sample collection site was located in Akwa neighbourhood.

2.3. Study population and sample size

The study population consisted of all Cameroonian patients attending sites of either of the seven above mentioned health facility, of both sexes, aged > 18 years old, settled in Douala, and having signed informed consent form. Conversely, patients who declined invitation and refused to sign informed consent form were excluded. Additionally, foreigner patients, those having recently travelled, those admitted at intensive care units, and individuals in whom blood collection was impossible were also excluded. To limit selection and information biases, patients were recruited consecutively through random sampling method. The sample size was determined using the Lorentz's formula n = [Z2 ×p × (1 - p)]/d2, where n = the required sample size, Z = statistics for the desired confidence interval (Z = 1.96 for 95% confidence level), d = accepted margin of error (d = 5%), and p = prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Littoral region (14.5%) (Tejiokem et al., 2022). The required sample size for this study was estimated as n = 190.5 ≈ 191 participants.

2.4. Data collection and management

A structured questionnaire form was used to sociodemographic information (health facility, gender, age, educational level, matrimonial status, occupation), anthropometric (weight, height) and clinical details (comorbidities, history of COVID-19 infection, presence of symptoms, blood group, COVID-19 vaccination status) (Table 1). Weight and height measured to compute body mass index (BMI) using Quetelet's formula: BMI (Kg/m2) = weight/(height)2. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 25 Kg/m2. ABO blood grouping was determined using Beth Vincent test (Godet and Chevillotte, 2013). Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected as per good clinical and laboratory practices.

2.5. Molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2

Nasopharyngeal swabs were transported to Clinical Virology Laboratory of Laquintinie hospital where extraction and amplification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome were performed. Viral genome was detected by retrotranscriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis of the RdRp, E, et N genes using a DaAnGene® kit (DaAn Gene Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China). Amplification of the SARS-CoV-2 genes were performed on a QuantStudioTM 7 real time thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Massachusetts, USA). Cycling conditions were as follows: reverse transcription (45°C/15 seconds) followed by initial denaturation (95°C/2 minutes), and 45 cycles of [denaturation (95°C/15 seconds), annealing (60°C/30 seconds), and extension (72°C/60 seconds)]. Internal control was included in each amplification. Cycle threshold (Ct) value of RT-qPCR was used to determine viremia and classified patients (negative or positive) as per manufacturer's instructions. The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as proportion of individuals with positive RT-qPCR.

2.6. Ethical considerations

National guidelines for human experimental models in clinical research were followed to conduct the present study. The study was approved by ethics committees of the University of Douala (N° 2945 CEI-UDo/12/2021/T), Littoral health regional delegation (N° 0038/AAR/MINSANTE/DRSPL/BCASS), and Douala Laquintinie Hospital (N° 08179/AR/MINSANTE/DHL). The study was explained to participants in the two official languages they understood best (French or English), and their questions were answered. Only patient who signed an informed consent form was enrolled. Participation in the study was strictly voluntary and patients were free to decline answering any question or totally withdraw if they so wished at any time.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were keyed in an Excel spreadsheet, coded, verified for consistency, and then analysed with GraphPad v5.03 (GraphPad PRISM, San Diego, Inc., CA, USA), SPSS v16 (SPSS IBM, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and StatView v5.0 (SAS Institute, Chicago, Inc., IL, USA) software. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Goodness-of-fit chi square, Pearson's independence chi square, and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare proportions. Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used to evaluate patterns of relationship between sociodemographic, clinical and virological characteristics of participants (Gower et al., 2010). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify determinants of infection with SARS-CoV-2. The association between independent variables and SARS-CoV-2 infection was quantified by computing crude and adjusted odds ratio (cOR and aOR), 95%CIs, and level of statistical significance. The resulting cOR and aOR values were then converted into crude and adjusted risk ratio (RR) as proposed earlier (Zhang and Yu, 1998). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Selection process of the participants

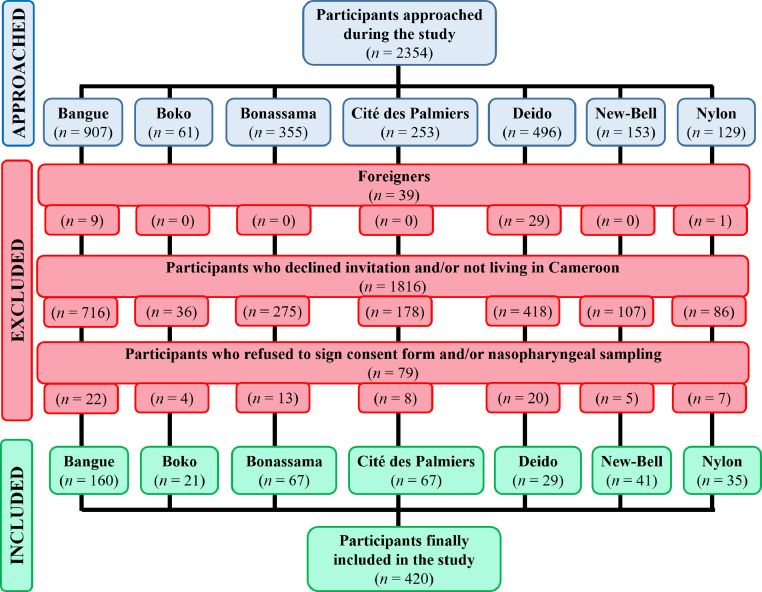

During the study, a total of 2354 patients were approached at the different health facilities. Of them, 1934 were excluded as per exclusion criteria. Finally, 420 patients were included in the study (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram depicting inclusion of participants in the study.

3.2. Sociodemographic details of the participants

The distribution of patients according to sociodemographic variables is summarized in Table 3. Patients aged < 30 years (23.3%) and 30 - 40 years (27.5%) cumulatively accounted for more than 50% of study population, and difference was statistically significant (p = 0.001). The mean age ± SD of patients was 42.3 ± 14.4 years (range 21 - 82). Likewise, most participants were married (53.1%, p = 0.02), had completed university studies (60.5%, p < 0.00001), and were working in non-medical formal sector (57.4%, p < 0.00001).

Table 3.

Distribution of the participants with regard to sociodemographic details.

| Variables | Categories | n | % | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years old) | < 30 | 98 | 23.3 | 0.001* |

| [30 - 40[ | 115 | 27.5 | ||

| [40 - 50[ | 78 | 18.6 | ||

| [50 - 60[ | 61 | 14.5 | ||

| [60 - 70[ | 51 | 12.1 | ||

| 70+ | 17 | 4.0 | ||

| Gender | Females | 198 | 47.1 | |

| Males | 222 | 52.9 | ||

| Matrimonial status | Single | 182 | 43.3 | 0.02* |

| Married | 223 | 53.1 | ||

| Divorced/Widow | 15 | 3.6 | ||

| Level of education | None | 2 | 0.5 | < 0.0001* |

| Primary | 23 | 5.5 | ||

| Secondary | 141 | 33.5 | ||

| University | 254 | 60.5 | ||

| Occupation | Student | 50 | 11.9 | < 0.0001* |

| Housewife | 34 | 8.1 | ||

| Retired | 16 | 3.8 | ||

| Medical formal sector | 26 | 6.2 | ||

| Non-medical formal sector | 241 | 57.4 | ||

| Informal sector | 53 | 12.6 |

Data are presented as frequency and percentage.

Goodness-of-fit chi square test was used to compare percentages.

Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3.3. Comorbidities reported in the participants

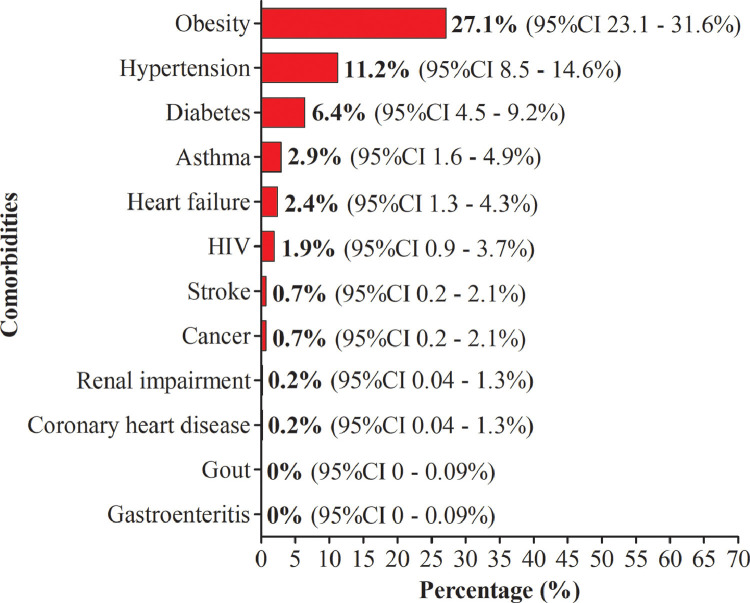

Of the 420 patients, 131 presented at least one comorbidity, giving an overall prevalence of 38.3% (95%CI 33.8 - 43.1%). Comorbidities were predominantly represented by obesity (27.1%, 95%CI 23.1 - 31.6%), hypertension (11.2%, 95%CI 8.5 - 14.6%) and diabetes (6.4%, 95%CI 4.5 - 9.2%). Other comorbidities including asthma, heart failure and HIV were also found (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of comorbidities seen in the participants.

3.4. Overall prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection

On analysis of RT-qPCR results, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in 34 of the 420 patients tested. Thus, the overall prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 was 8.1% (95%CI 5.9 - 11.1%).

3.5. SARS-CoV-2 infection and sociodemographic characteristics

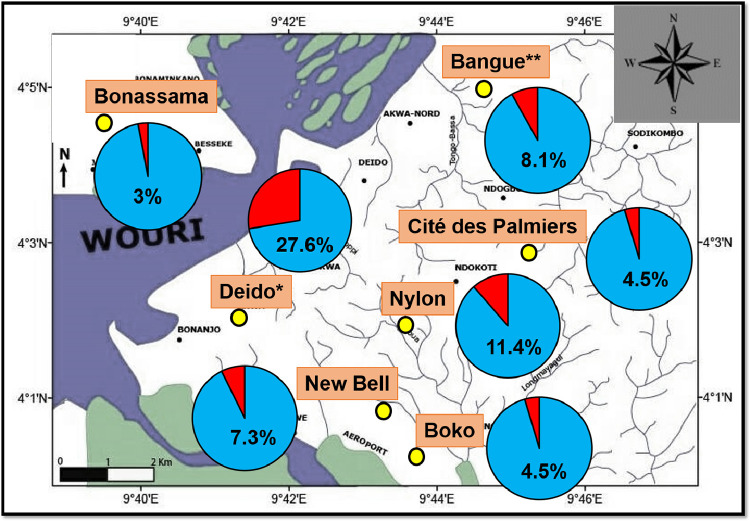

The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection varied significantly between study sites (p = 0.0038), with the highest prevalence estimates found at the Deido district hospital's site (27.6%) (Fig. 4 ). We found significant association between SARS-CoV-2 prevalence, matrimonial status and level of education (Table 4). Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection was highest in married (11.7%, p = 0.01) and those having completed primary studies (12.8%, p = 0.04).

Fig. 4.

Spatial variation of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Map was generated using the ArcGIS v8.1 software (Esri, Redlands, California, USA).

Study sites are presented as yellow circles.

The prevalence of viral infection at each study site is presented as pie charts (red section).

*For Deido district hospital, the sample collection site was located in Bonamoussadi neighbourhood.

**For Bangue district hospital, the sample collection site was located in Akwa neighbourhood.

Table 4.

Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 by sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variables | Categories | N | n (%) | χ2 (df) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years old) | < 30 | 98 | 7 (7.1%) | 6.27 (5) | 0.28 |

| [30 - 40[ | 115 | 7 (6.1%) | |||

| [40 - 50[ | 78 | 7 (9.0%) | |||

| [50 - 60[ | 61 | 5 (8.2%) | |||

| [60 - 70[ | 51 | 4 (7.8%) | |||

| 70+ | 17 | 4 (23.5%) | |||

| Gender | Females | 198 | 14 (7.1%) | 0.53 (1) | 0.46 |

| Males | 222 | 20 (9.0%) | |||

| Matrimonial status | Single | 182 | 7 (3.8%) | 8.26 (2) | 0.01* |

| Married | 223 | 26 (11.7%) | |||

| Divorced/Widow | 15 | 1 (6.7%) | |||

| Level of education | None | 25 | 1 (4.0%) | 6.34 (2) | 0.04* |

| Primary | 141 | 18 (12.8%) | |||

| Secondary | 254 | 15 (5.9%) | |||

| University | 50 | 4 (8.0%) | |||

| Occupation | Student | 34 | 2 (5.9%) | 1.18 (5) | 0.94 |

| Housewife | 16 | 1 (6.3%) | |||

| Retired | 26 | 1 (3.8%) | |||

| Medical formal sector | 241 | 21 (8.7%) | |||

| Non-medical formal sector | 53 | 5 (9.4%) |

Independence Pearson's chi square test was used to compare percentages.

χ2: Decision variable of chi square test, df: Degree of freedom.

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

3.6. SARS-CoV-2 infection and clinical characteristics

As depicted in Table 5, the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 was significantly higher in patients i) presenting at least one comorbidities (13.7%, p = 0.001), ii) diabetic (18.5%, p = 0.01), iii) hypertension (17%, p = 0.01), iv) asthmatic (13.7%, p < 0.0001), v) HIV-positive (62.5%, p < 0.0001), and vi) frequently seeking health care (13,9%; p < 0,0001). Only 18.6% (78/420) participants were COVID-19 vaccinated. SARS-CoV-2 infection suggesting symptoms such as fever and cough were found in patients irrespective of COVID-19 vaccination status. However, proportion of symptomatic patients was higher in unvaccinated individuals compared to their vaccinated counterparts (90.3% vs 9.7%, p < 0.0001).

Table 5.

Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection by clinical characteristics.

| Variables | Categories | N | n (%) | χ2 (df) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | No | 259 | 12 (4.6%) | 10.9 (1) | 0.001* |

| Yes | 161 | 22 (13.7%) | |||

| Obesity | No | 306 | 24 (7.8%) | 0.09 (1) | 0.75 |

| Yes | 114 | 10 (8.8%) | |||

| Diabetes | No | 393 | 29 (7.4%) | 4.2 (1) | 0.04* |

| Yes | 27 | 5 (18.5%) | |||

| Hypertension | No | 373 | 26 (7.0%) | 5.7 (1) | 0.01* |

| Yes | 47 | 8 (17.0%) | |||

| Asthma | No | 408 | 28 (6.9%) | 29.2 (1) | < 0.0001* |

| Yes | 12 | 6 (50.0%) | |||

| HIV | No | 412 | 29 (7.0%) | 32.4 (1) | < 0.0001* |

| Yes | 8 | 5 (62.5%) | |||

| Heart failure | No | 410 | 33 (8.0%) | - | 0.57 |

| Yes | 10 | 1 (10.0%) | |||

| Frequently seeking health care | No | 187 | 5 (2.7%) | 15.7 (1) | < 0.0001* |

| Yes | 209 | 29 (13.9%) | |||

| Blood group | A | 104 | 7 (6.7%) | 5.1 (3) | 0.16 |

| AB | 19 | 3 (15.8%) | |||

| B | 70 | 2 (2.9%) | |||

| O | 227 | 22 (9.7%) | |||

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | No | 342 | 30 (8.8%) | 1.1 (1) | 0.28 |

| Yes | 78 | 4 (5.1%) | |||

| History of COVID-19 | No | 353 | 33 (9.3%) | 4.7 (1) | 0.01* |

| Yes | 67 | 1 (1.5%) |

Independence Pearson's chi square test was used to compare percentages.

χ2: Decision variable of chi square test, df: Degree of freedom.

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

3.7. Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Nine variables were associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection viz. health facility, age, matrimonial status, presence of comorbidity, diabetes, HIV, asthma, and frequent sickness (Table 6). The risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection was ∼five times increased in patients attending the Deido district hospital's site (aRR = 4.46, 95%CI 1.56 - 6.25, p = 0.003), compared to those from the Bangue district hospital's site. This risk was multiplied by nearly four times in married (aRR = 3.51, 95%CI 1.38 - 6.19, p < 0.0001), and by more than six times in HIV-positive patients (aRR = 6.80, 95%CI 3.91 - 12.56, p < 0.0001) and those seeking health care regularly (aRR = 6.03, 95%CI 2.15 - 11.13, p = 0.004), and by more than eight times in asthmatic patients (aRR = 7.89, 95%CI 3.39 - 11.26, p = 0.003).

Table 6.

Univariate logistic regression of factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Variables | Categories | cOR (95%CI) | cRR (95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Health facility | Bangue | 1 | 1 | |

| Boko | 0.57 (0.07 - 4.56) | 0.67 (0.08 - 3.54) | 0.59 | |

| Bonassama | 0.35 (0.08 - 1.59) | 0.41 (0.09 - 1.52) | 0.17 | |

| Cité des Palmiers | 0.53 (0.15 - 1.92) | 0.63 (0.16 - 1.79) | 0.33 | |

| Deido | 4.31 (1.60 - 11.62) | 4.46 (1.53 - 6.25) | 0.003* | |

| New-Bell | 0.89 (0.24 - 3.29) | 1.05 (0.26 - 2.78) | 0.86 | |

| Nylon | 1.46 (0.45 - 4.78) | 1.70 (0.47 - 3.66) | 0.53 | |

| Age groups (years old) | < 30 | 1 | 1 | |

| [30 - 40[ | 0.84 (0.28 - 2.49) | 0.97 (0.30 - 2.25) | 0.76 | |

| [40 - 50[ | 1.28 (0.43 - 3.82) | 1.47 (0.45 - 3.18) | 0.66 | |

| [50 - 60[ | 1.16 (0.35 - 3.83) | 1.33 (0.37 - 3.19) | 0.81 | |

| [60 - 70[ | 1.11 (0.31 - 3.97) | 1.28 (0.33 - 3.28) | 0.87 | |

| 70+ | 4.00 (1.03 - 15.57) | 4.24 (1.03 - 7.65) | 0.04* | |

| Gender | Females | 1 | 1 | |

| Males | 1.30 (0.64 - 2.65) | 1.49 (0.66 - 2.37) | 0.47 | |

| Matrimonial status | Single | 1 | 1 | |

| Married | 3.30 (1.40 - 7.79) | 3.51 (1.38 - 6.19) | 0.006* | |

| Divorced/Widow | 1.79 (0.20 - 15.56) | 1.92 (0.21 - 10.02) | 0.59 | |

| Level of education | None/Primary | 1 | 1 | |

| Secondary | 3.51 (0.45 - 27.58) | 3.73 (0.46 - 13.37) | 0.23 | |

| University | 1.51 (0.19 - 11.91) | 1.63 (0.20 - 8.29) | 0.69 | |

| Occupation | Student | 1 | 1 | |

| Formal sector | 1.02 (0.34 - 3.08) | 1.20 (0.36 - 2.64) | 0.97 | |

| Informal sector | 1.01 (0.28 - 3.62) | 1.18 (0.30 - 2.99) | 0.99 | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Comorbidity | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 3.26 (1.56 - 6.78) | 3.50 (1.52 - 5.36) | 0.001* | |

| Obesity | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.52 - 2.44) | 1.34 (0.54 - 2.17) | 0.75 | |

| Diabetes | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.85 (1.01 - 8.09) | 3.16 (1.01 - 5.31) | 0.04* | |

| Hypertension | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.74 (1.16 - 6.46) | 2.99 (1.13 - 3.24) | 0.02* | |

| HIV | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 22.01 (5.01 - 96.74) | 6.80 (3.91 - 12.56) | < 0.0001* | |

| Heart failure | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.27 (0.16 - 10.33) | 1.48 (0.17 - 5.92) | 0.82 | |

| Asthma | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 13.57 (4.11 - 44.84) | 7.89 (3.39 - 11.26) | < 0.0001* | |

| Blood group | A | 1 | 1 | |

| AB | 2.60 (0.61 - 11.10) | 2.89 (0.63 - 6.62) | 0.19 | |

| B | 0.41 (0.05 - 2.02) | 0.47 (0.05 - 1.89) | 0.27 | |

| O | 1.49 (0.61 - 3.60) | 1.69 (0.63 - 3.07) | 0.37 | |

| Frequently seeking health care | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 5.86 (2.22 - 15.49) | 6.03 (2.15 - 11.13) | 0.004* | |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.56 (0.19 - 1.65) | 0.67 (0.20 - 1.56) | 0.29 | |

| History of COVID-19 | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.15 (0.02 - 1.09) | 0.18 (0.02 - 1.08) | 0.06 | |

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among the participants.

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, 95%CI: Confidence interval at 95%, cOR: Crude odds ratio, cRR: Crude risk ratio, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2.

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

Multivariate logistic analysis identified nine determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection - six risk factors (age, matrimonial status, level of education, HIV, asthma, and frequent sickness) and three protective factors (health facility, anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and blood group) (Table 7). Indeed, risk of infection was reduced by 93% in patients of blood group B (aRR = 0.07, 95%CI 0.00 - 0.89, p = 0.04), compared to those of blood group A. Likewise, the risk was reduced by 95% in vaccinated participants (aRR = 0.05, 95%CI 0.00 - 0.40, p = 0.005), compared to their unvaccinated counterparts (Table 7).

Table 7.

Multivariate logistic regression of factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Variables | Categories | aOR (95%CI) | aRR (95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Health facility | Bangue | 1 | 1 | |

| Boko | 0.36 (0.03 - 4.68) | 0.43 (0.03 - 3.61) | 0.43 | |

| Bonassama | 0.12 (0.01 - 0.91) | 0.14 (0.01 - 0.92) | 0.04* | |

| Cité des Palmiers | 0.19 (0.03 - 1.27) | 0.22 (0.03 - 0.92) | 0.08 | |

| Deido | 3.18 (0.67 - 15.14) | 3.49 (0.69 - 7.06) | 0.14 | |

| New-Bell | 0.14 (0.01 - 1.48) | 0.17 (0.01 - 1.42) | 0.11 | |

| Nylon | 0.59 (0.10 - 3.33) | 0.70 (0.11 - 2.80) | 0.55 | |

| Age groups (years old) | < 30 | 1 | 1 | |

| [30 - 40[ | 0.11 (0.01 - 0.88) | 0.13 (0.01 - 0.89) | 0.03* | |

| [40 - 50[ | 0.16 (0.02 - 1.33) | 0.19 (0.02 - 1.30) | 0.08 | |

| [50 - 60[ | 0.07 (0.01 - 0.82) | 0.08 (0.01 - 0.83) | 0.03* | |

| [60 - 70[ | 0.20 (0.02 - 2.54) | 0.23 (0.02 - 2.29) | 0.21 | |

| 70+ | 9.16 (1.10 - 209.35) | 7.12 (1.09 - 13.26) | 0.001* | |

| Gender | Females | 1 | 1 | |

| Males | 1.18 (0.37 - 3.77) | 1.36 (0.39 - 3.15) | 0.77 | |

| Matrimonial status | Single | 1 | 1 | |

| Married | 6.51 (1.28 - 33.11) | 6.60 (1.27 - 14.91) | 0.02* | |

| Divorced/Widow | 1.50 (0.05 - 48.32) | 1.62 (0.05 - 17.27) | 0.81 | |

| Level of education | None/Primary | 1 | 1 | |

| Secondary | 71.54 (1.70 - 3008.32) | 7.85 (1.65 - 24.80) | 0.02* | |

| University | 18.66 (0.41 - 854.41) | 12.62 (0.42 - 24.32) | 0.13 | |

| Occupation | Student | 1 | 1 | |

| Formal sector | 0.66 (0.09 - 4.84) | 0.78 (0.10 - 3.70) | 0.68 | |

| Informal sector | 0.41 (0.03 - 5.32) | 0.48 (0.03 - 3.95) | 0.49 | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Comorbidity | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.29 (0.35 - 14.76) | 2.49 (0.36 - 7.03) | 0.38 | |

| Obesity | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.15 (0.10 - 12.89) | 1.37 (0.11 - 6.30) | 0.91 | |

| Diabetes | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.35 (0.06 - 2.11) | 0.41 (0.06 - 1.95) | 0.25 | |

| Hypertension | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.62 (0.11 - 3.57) | 0.91 (0.13 - 2.43) | 0.59 | |

| HIV | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 289.9 (7.71 - 10879.88) | 7.64 (5.25 - 14.27) | < 0.0001* | |

| Heart failure | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.41 (0.08 - 24.11) | 1.64 (0.09 - 8.46) | 0.81 | |

| Asthma | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 10.43 (1.21 - 90.09) | 7.60 (1.19 - 12.76) | 0.03* | |

| Blood group | A | 1 | 1 | |

| AB | 1.43 (0.13 - 15.74) | 1.63 (0.14 - 7.92) | 0.19 | |

| B | 0.06 (3.00E−3 - 0.88) | 0.07 (0.00 - 0.89) | 0.04* | |

| O | 1.37 (0.37 - 4.99) | 1.56 (0.39 - 3.94) | 0.63 | |

| Frequently seeking health care | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 9.34 (2.33 - 37.40) | 9.24 (2.25 - 18.86) | 0.001* | |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.04 (3.50E−3 - 0.38) | 0.05 (0.00 - 0.40) | 0.005* | |

| History of COVID-19 | No | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.10 (0.01 - 1.44) | 0.12 (0.01 - 1.38) | 0.09 | |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among the participants.

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, 95%CI: Confidence interval at 95%, aOR: Adjusted odds ratio, aRR: Adjusted risk ratio, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2.

Statistically significant at p-value < 0.05

MCA was used as complementary analysis to logistic regression analysis, and results indicated that 63.78% of the total inertia was represented by factorial components (36.57% for factorial component 1 and 27.21% for factorial component 2) (Fig. 5 ). A correlation was found between comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, obesity), age and level of education (Fig. 5 a & b). For instance, the proportion of individuals with at least one comorbidity was significantly higher in those having completed secondary studies (47.5%) compared to those having completed primary studies (44%) and university studies (32.7%) (χ2 = 8.80, p = 0.01). Likewise, diabetes was more frequently reported in participants with secondary educational level (12.8%) compared to those with primary level (8%) and university level (2.8%) (χ2 = 15.21, p = 0.0006). Also, matrimonial status, frequent health care seeking and occupation variables were correlated each other (Fig. 5 a & b). The proportion of individuals seeking frequently health care was higher in married compared to single (58.2% vs 43.5%, χ2 = 13.64, p = 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Multiple correspondence analysis of variables (a) and variables’ categories (b).

4. Discussion

Here we present the first update of epidemiological situation of SARS-CoV-2 in the town of Douala, the economic capital of Cameroon. The findings of this study could be helpful to guide national control strategies implemented by Government of Cameroon.

The overall prevalence of the infection was 8.1% which is lower than that of previous report in Douala (Medi et al., 2022; Tejiokem et al., 2022). In contrast, our prevalence estimate is higher than that reported during different waves of COVID-19 in Douala and Yaoundé (Table 1). This prevalence is higher than that reported recently in Malawi (0.3 - 0.5%) and Austria (0.39 - 1.39%) (Theu et al., 2022; Willeit et al., 2021). Similarly, another study conducted in Denmark reported low incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection following vaccination campaigns (Heftdal et al., 2022). In contrast, higher RT-qPCR based prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection were found in Asian settings such as Iran (30.4%) (Monireh and Kiana, 2022). Several factors involving complex interplay between human, virus and environment could explain these discrepancies. First, the distribution of comorbidities in study populations is likely an important factor modulating SARS-CoV-2 infection risk. We reported that obesity, diabetes, and hypertension were predominant comorbidities, and this finding was also reported earlier (Ebongue et al., 2022; Kojom Foko et al., 2021; Loteri et al., 2022). Likewise, high prevalence values of diabetes and hypertension were found in hospitalized COVID-19 patients living in Douala and Yaoundé (Mbarga Fouda et al., 2021; Mekolo et al., 2021). Second, SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating in the country is also a plausible explanation (Raman et al., 2021). Some studies reported the circulation of different SARS-CoV-2 variants in Cameroon (Chouikha et al., 2022; Njouom et al., 2020). However, large epidemiological data on the extent of SARS-CoV-2 variants are still lacking in the country. Third, COVID-19 control measures such as vaccination could have play role in modulating SARS-CoV-2 prevalence (Schenten and Bhattacharya, 2021). Finally, differences in study population, detection method and sample size could also explain discrepancies between SARS-CoV-2 prevalence found in this study and elsewhere.

Advanced age (≥ 70 years), marital status (married), level of education (secondary studies), and comorbidities (HIV, asthma) were strong risk factors of infection with SARS-CoV-2. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies on determinants of COVID-19 infection, severity and mortality (Mbarga Fouda et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020). In elderly patients, global immune responses are decreased due to ageing, and this is could explain an increased COVID-19 risk in this social group (Chen et al., 2021). Furthermore, depletion in immunity is aggravated in immunocompromising disorders such as HIV and autoimmune diseases. In HIV-positive patients, levels of CD4 lymphocytes - crucial cell players in immunity - are profoundly decreased in absence of any anti-retroviral therapy (Deeks et al., 2015). All things being equal, the chances of COVID-19 are increased in married people compared to single people, and this is likely due to the presence of a partner. Also, we found that married participants were seeking more frequently health care than single participants, thereby suggesting higher susceptibility of married participants to health ailments. Consisting with our findings, some studies found an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with higher level of education (El-Ghitany et al., 2022). As per MCA results, we have noted that presence of comorbidities (obesity, diabetes, HIV) were highly correlated with secondary educational level. Thus, this strong association between level of education and SARS-CoV-2 infection could be explained by higher proportion of comorbidities among participants with secondary educational level.

Interestingly, vaccination and blood group were protective factors of SARS-CoV-2. Even though, coverage vaccination was low in this study, we reported reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection risk by 95% in vaccinated patients compared to their unvaccinated counterparts. Even though we did not genotype SARS-CoV-2 infections to determine circulating variants, this finding is in line with that of systematic reviews and meta-analyses that showed a moderately-to-highly protective effect of COVID-19 vaccines against Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta SARS-CoV-2 lineages (Kai et al., 2021; Korang et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022).

Existing evidences and pathophysiological mechanisms on the association between COVID-19 and blood group are contradictory and elusive (Goel et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021). In this study, we found protective effect of blood group B against COVID-19. A recent study reported an increased COVID-19 susceptibility in Indian patients of blood groups A and B (Rana et al., 2021). In China and Turkey, blood group A was associated with an increased risk of infection while blood group O was associated with a decreased risk (Solmaz and Araç, 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). In USA and Egyptian patients, no association was found between ABO group and COVID-19 susceptibility (El-Ghitany et al., 2022; Zietz et al., 2020).

5. Conclusion

The present study provided an update of epidemiological situation of SARS-CoV-2 in Douala, Cameroon. The SARS-CoV-2 was found in ∼10% of patients. Comorbidities were dominated by obesity, hypertension and diabetes. Advanced age, matrimonial status, level of education, comorbidities (HIV, asthma) and frequent seeking for health care were associated with increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, while health facility, blood group B and COVID-19 vaccination were protective factors against infection. The findings from this study outline the need for ongoing surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Cameroon. Table 2

Table 2.

Information collected from each patient.

| Type of data | Variables | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data |

|

Medical record and declaration of the patient |

| Anthropometric data |

|

Body measurement (scale and stadiometer) |

| Clinical data |

|

Medical record, medical doctors, declaration of the patient, laboratory experiment (Beth Vincent test) |

| Molecular data |

|

Laboratory experiment (RT-qPCR) |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, RT-qPCR: Retrotranscriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction, SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2.

Comorbidity was defined as the co-occurrence of more than one health disease in the same individual

Author statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Arlette Flore Moguem Soubgui: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Elisee Libert Embolo Enyegue: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Loick Pradel Kojom Foko: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Wilfried Steve Ndeme Mboussi: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Gildas Deutou Hogoue: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Suzy Pascale Mbougang: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Sandra Michelle Sanda: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Isaac Ulrich Fotso Chidjou: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Valery Fabrice Fotso: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Steve Armand Nzogang Tchonet: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Christiane Medi Sike: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Martin Luther Koanga Mogtomo: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to patients having accepted to participate in the study. We also acknowledge support and technical assistance of managing authorities, medical doctors and staff of health facilities. We are also grateful to Mr. Stephane Koum (Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, The University of Douala, Cameroon) for generating map.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bandeira L., Lazaretti-Castro M., Binkley N. Clinical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vitamin D. Rev. Endocrine Metabolic Disorders. 2022;23:287–291. doi: 10.1007/s11154-021-09683-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Klein S.L., Garibaldi B.T., Li H., Wu C., Osevala N.M., Li T., Margolick J.B., Pawelec G., Leng S.X. Aging in COVID-19: vulnerability, immunity and intervention. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021;65 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouikha A., Lagare A., Ghedira K., Diallo A., Njouom R., Sankhe S., Derrar F., Victoir K., Dellagi K., Triki H., Diagne M.M. SARS-CoV-2 lineage A.27: new data from African countries and dynamics in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Viruses. 2022;14:1007. doi: 10.3390/v14051007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks S.G., Overbaugh J., Phillips A., Buchbinder S. HIV infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2015;1:15035. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongang Nana R.R., Hawadak J., Kojom Foko L.P., Kumar A., Chaudhry S., Arya A., Singh V. Intermittent preventive treatment with Sulfadoxine pyrimethamine for malaria: a global overview and challenges affecting optimal drug uptake in pregnant women. Pathogens Global Health. 2022;00:1–14. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2022.2128563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebongue M.S.N., Lemogoum D., Endale-Mangamba L.M., Barche B., Eyoum C., Simo Yomi S.H., Mekolo D., Ngambi V., Doumbe J., Sike C.M., Boombhi J., Ngondi G., Biholong C., Kamdem J., Mbenoun L., Tegeu C.K., Djomou A., Dzudie A., Kamdem F., Ntock F.N., Mfeukeu L.K., Sobngwi E., Penda I., Njock R., Essomba N., Yombi J.C., Ngatchou W. Factors predicting in-hospital all-cause mortality in COVID 19 patients at the Laquintinie Hospital Douala, Cameroon. Travel Med. Infectious Dis. 2022;47 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghitany E.M., Ashour A., Farghaly A.G., Hashish M.H., Omran E.A. Predictors of anti-SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity: an Egyptian population-based study. Infectious Med. 2022;1:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.imj.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fai K.N., Corine T.M., Bebell L.M., Mboringong A.B., Nguimbis E.B.P.T., Nsaibirni R., Mbarga N.F., Eteki L., Nikolay B., Essomba R.G., Ndifon M., Ntone R., Hamadou A., Matchim L., Tchiasso D., Abah Abah A.S., Essaka R., Peppa S., Crescence F., Ouamba J.P., Koku M.T., Mandeng N., Fanne M., Eyangoh S., Mballa G.A.E., Esso L., Epée E., Njouom R., Okomo Assoumou M.C., Boum Y. Serologic response to SARS-CoV-2 in an African population. Scientific African. 2021;12:e00802. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokam J., Takou D., Nka A.D., Ka'e A.C., Yagai B., Ambe Chenwi C., Ngoufack Jagni Semengue E., Angong Beloumou G., Djupsa Ndjeyep S.C., Abba A., Pabo W., Gouissi D., Tommo Tchouaket M.C., Yatchou L., Zam K., Mama L., Ekitti R.C., Fainguem N., Kamgaing R., Sosso S.M., Ndembi N., Colizzi V., Perno C.-F., Ndjolo A. Epidemiological, virological and clinical features of SARS-CoV-2 among individuals during the first wave in Cameroon: baseline analysis for the EDCTP PERFECT-Study RIA2020EF-3000. J. Public Health Africa. 2022;13:1–7. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2022.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frühbeck G., Baker J.L., Busetto L., Dicker D., Goossens G.H., Halford J.C.G., Handjieva-Darlenska T., Hassapidou M., Holm J.C., Lehtinen-Jacks S., Mullerova D., O'Malley G., Sagen J.V., Rutter H., Salas X.R., Woodward E., Yumuk V., Farpour-Lambert N.J. European association for the study of obesity position statement on the global COVID-19 pandemic. Obesity Facts. 2020;13:292–296. doi: 10.1159/000508082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautret P., Million M., Jarrot P.A., Camoin-Jau L., Colson P., Fenollar F., Leone M., La Scola B., Devaux C., Gaubert J.Y., Mege J.L., Vitte J., Melenotte C., Rolain J.M., Parola P., Lagier J.C., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Natural history of COVID-19 and therapeutic options. Expert Rev. Clinic. Immunol. 2020;16:1159–1184. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2021.1847640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godet M., Chevillotte J. ABO compatibility testing with the Beth Vincent test. Revue de l'Infirmiere. 2013;62:53–54. doi: 10.1016/j.revinf.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel R., Bloch E.M., Pirenne F., Al-Riyami A.Z., Crowe E., Dau L., Land K., Townsend M., Jecko T., Rahimi-Levene N., Patidar G., Josephson C.D., Arora S., Vermeulen M., Vrielink H., Montemayor C., Oreh A., Hindawi S., van den Berg K., Serrano K., So-Osman C., Wood E., Devine D.V., Spitalnik S.L. ABO blood group and COVID-19: a review on behalf of the ISBT COVID-19 Working Group. Vox Sang. 2021;116:849–861. doi: 10.1111/vox.13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower J., Lubbe S., Roux N. Multiple correspondence analysis. Understanding Biplots. 2010:365–403. doi: 10.1002/9780470973196.ch8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heftdal L.D., Schulz M., Lange T., Dehlbaek Knudsen A., Fogh K., Bo HasselBalch R., Borgen Linander C., Kallemose T., Bundgaard H., Gronbaek K., Valentiner-Bra, th P., Iversen K., Dam Nielsen S. Incidence of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR after COVID-19 vaccination with up to eight months of follow-up: real life data from the Capital Region of Denmark. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022;24:e675–e682. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan A.B., Jewell B.L., Sherrard-Smith E., Vesga J.F., Watson O.J., Whittaker C., Hamlet A., Smith J.A., Winskill P., Verity R., Baguelin M., Lees J.A., Whittles L.K., Ainslie K.E.C., Bhatt S., Boonyasiri A., Brazeau N.F., Cattarino L., Cooper L.V., Coupland H., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Dighe A., Djaafara B.A., Donnelly C.A., Eaton J.W., van Elsland S.L., FitzJohn R.G., Fu H., Gaythorpe K.A.M., Green W., Haw D.J., Hayes S., Hinsley W., Imai N., Laydon D.J., Mangal T.D., Mellan T.A., Mishra S., Nedjati-Gilani G., Parag K.V., Thompson H.A., Unwin H.J.T., Vollmer M.A.C., Walters C.E., Wang H., Wang Y., Xi X., Ferguson N.M., Okell L.C., Churcher T.S., Arinaminpathy N., Ghani A.C., Walker P.G.T., Hallett T.B. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8:e1132–e1141. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30288-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai X., Xiao-Yan T., Miao L., Zhang-Wu L., Jiang-Nan C., Jiao-Jiao L., Li-Guo J., Fu-Qiang X., Yi J. Efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review. Chin. J. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2021;23:221–228. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2101133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Latz C.A., DeCarlo C.S., Lee S., Maximilian Png C., Kibrik P., Sung E., Alabi O., Dua A. Relationship between blood type and outcomes following COVID-19 infection. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2021;34:125–131. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojom Foko L.P., Nolla N.P., Nyabeyeu Nyabeyeu H., Lehman L.G. Prevalence, patterns, and determinants of malaria and malnutrition in Douala, Cameroon : a cross-sectional community-based study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5553344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korang S.K., von Rohden E., Veroniki A.A., Ong G., Ngalamika O., Siddiqui F., Juul S., Nielsen E.E., Feinberg J.B., Petersen J.J., Legart C., Kokogho A., Maagaard M., Klingenberg S., Thabane L., Bardach A., Ciapponi A., Thomsen A.R., Jakobsen J.C., Gluud C. Vaccines to prevent COVID-19: a living systematic review with Trial Sequential Analysis and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loteri O., Moguem Sobgui A.F., Kojom Foko L.P., Ndeme Mboussi W.S., Medi Sike C., Embolo Enyegue E.L., Koanga Mogtomo M.L. COVID-19 and comorbidities in Douala, Cameroon. Int. J. Tropical Dis. Health. 2022;43:21–38. doi: 10.9734/IJTDH/2022/v43i1730658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mbarga Fouda N., Epee E., Mbarga M., Ouamba P., Nanda H., Nkengni A., Guekeme J., Eyong J., Tossoukpe S., Sosso S.N., Ngono E.N., Ntsama L.M., Bonyomo L., Tchatchoua P., Vogue N., Metomb S., Ale F., Ousman M., Job D., Moussi C., Tamakloe M., Haberer J.E., Atanga S.N., Halle-Ekane G., Boum Y. Clinical profile and factors associated with COVID-19 in Yaounde, Cameroon: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbopi-Keou F.X., Pondi J.E., Sosso M.A. COVID-19 in Cameroon: a crucial equation to resolve. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:1367–1368. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30373-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medi C.I., Voundi E.V., Lobe S.A., Eyoum Bille B., Ngogang M.P., Ndoumba Mintya A., Embolo E.L., Essomba E.N., Nguedia J.A. COVID-19 in blood donors at Laquintinie hospital in Douala during the third wave: a cross sectional study. Open J. Epidemiol. 2022;12:367–379. doi: 10.4236/ojepi.2022.123030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mekolo D., Bokalli F.A., Chi F.M., Fonkou S.B., Takere M.M., Ekukole C.M., Balomoth J.M.B., Nsagha D.S., Essomba N.E., Njock L.R., Ngowe M.N. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in Douala. Cameroon. Pan African Med. J. 2021;38:246. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.246.28169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monireh R., Kiana K. Prevalence of the clinical symptoms and PCR test results on patients with COVID-19 in South of Tehran. Microbiol. Insights. 2022;15:1–4. doi: 10.1177/11786361221097680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndongo Ateba F., Guichet E., Mimbé E.D., Ndié J., Pelloquin R., Varloteaux M., Esemu L., Mpoudi-Etame M., Lamare N., Edoul G., Wouambo R.K., Djomsi D.M., Tongo M., Tabala F.N., Dongmo R.K., Diallo M.S.K., Bouillin J., Thaurignac G., Ayouba A., Peeters M., Delaporte E., Bissek A.C.Z.K., Mpoudi-Ngolé E. Rapid increase of community SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence during second wave of COVID-19, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022;28:1233–1236. doi: 10.3201/eid2806.212580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngaba G.P., Kalla G.C.M., Assob Nguedia J.C., Njouendou A.J., Jembe C.N., Mboudou E.T., Mbopi-Keou F.X. Comparative analysis of two molecular tests for the detection of covid-19 in Cameroon. Pan African Med. J. 2021;39:214. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.214.30718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngaba G.P., Kalla G.C.M., Nguedia Assob J.C., Njouendou A.J., Jembe C.N., Mboudou E.T., Mbopi-Keou F.X. Evaluation de deux tests de diagnostic antigénique du covid-19: BIOSYNEX® COVID-19 Ag BSS et BIOSYNEX® COVID-19 Ag+ BSS comparés à la PCR AmpliQuick® SARS-CoV-2. Pan African Med. J. 2021;39:228. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.228.30752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguwoh P.S., Mboringong A.B., Fokam J., Ngounouh Taheu C., Halilou I., Djieudeu Nouwe S.H., Moussa N.I., Al-Mayé Bit Younouss A., Likeng J.L.N., Tchoffo D., Essomba G.R., Kamga H.L., Okomo M.C.A. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) among health care workers in three health facilities of Yaounde, Center Region of Cameroon. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2021;3:89–94. doi: 10.24018/ejmed.2021.3.6.1109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Njouom R., Sadeuh-mba S.A., Tchatchueng J., Dia N., Tagnouokam Ngoupo P.A., Boum Y., Hamadou A., Esso L., Faye O., Tejiokem M.C., Okomo M.C., Etoundi A., Carniel E., Eyangoh S. Coding-complete genome sequence and phylogenetic relatedness of a SARS-CoV-2 strain detected in March 2020 in Cameroon. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020;3:e00093. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00093-21. -21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu K., Fokam J., Wanda F., Mama L., Orel E., Ray N., Meke J., Tassegning A., Takou D., Mimbe E., Stoll B., Guillebert J., Comte E., Keiser O., Ciaffi L. SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence and associated risk factors in an urban district in Cameroon. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5851. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25946-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman R., Patel K.J., Ranjan K. Covid-19: Unmasking emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, vaccines and therapeutic strategies. Biomolecules. 2021;11:993. doi: 10.3390/biom11070993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R., Ranjan V., Kumar N. Association of ABO and Rh blood group in susceptibility, severity, and mortality of coronavirus disease 2019: A hospital-based study from Delhi, India. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.767771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safiabadi Tali S.H., LeBlance J.J., Sadiq J. Tools and techniques for severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021;34:e00228. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00228-20. -20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenten D., Bhattacharya D. Immunology of SARS-CoV-2 infections and vaccines. Adv. Immunol. 2021;151:49–97. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmaz İ., Araç S. ABO blood groups in COVID-19 patients; cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75:e13927. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejiokem M.C., Serge S.-M., Brice T.M.J., Alain T.N.P., Grace N., Joseph F., Achta H., Gisèle N., Julius N., Marcel T., Melissa S., Lucy N., Ronald P., Claire O.A.M., Walter P.Y.E., Alain E.M.G., Richard N., Sara E. Clinical presentation of COVID-19 at the time of testing and factors associated with pre-symptomatic cases in Cameroon. IJID Regions. 2022;4:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theu J.A., Kabaghe A.N., Bello G., Chitsa-Banda E., Kagoli M., Auld A., Mkungudza J., O'Malley G., Bangara F.F., Peacocke E.F., Babaye Y., Ng'ambi W., Saussier C., MacLachlan E., Chapotera G., Phiri M.D., Kim E., Chiwaula M., Payne D., Wadonda-Kabondo N., Chauma-Mwale A., Divala T.H. SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in Malawi based on data from survey of communities and health workers in 5 high-burden districts, October 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022;28:76–84. doi: 10.3201/eid2813.212348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titanji V.P. Priority research themes in the fight against the COVID-19 with particular reference to Cameroon. J. Cameroon Acad. Sci. 2020;15:209–217. doi: 10.4314/jcas.v15i3.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak.

- Willeit P., Krause R., Lamprecht B., Berghold A., Hanson B., Stelzl E., Stoiber H., Zuber J., Heinen R., Köhler A., Bernhard D., Borena W., Doppler C., von Laer D., Schmidt H., Pröll J., Steinmetz I., Wagner M. Prevalence of RT-qPCR-detected SARS-CoV-2 infection at schools: first results from the Austrian School-SARS-CoV-2 prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Europe. 2021;5 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X, Xu S., Huang H., Zhang L., Zhou X, Du C., Zhang Y., Song J., Wang S., Chao Y., Yang Z., Xu J., Zhou X, Chen D., Xiong W., Xu L., Zhou F., Jiang J., Bai C., Zheng J., Song Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with sse 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020:E1–E10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng B., Gao L., Zhou Q., Yu K., Sun F. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2022;20:200. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02397-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Yu K.F. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Yang Y., Huang H., Li D., Gu D., Lu X., Zhang Z., Liu L., Liu T., Yukun L., HHe Y., Sun Bb., Wei M., Yang G., Wang X., Zhang L., Zhou X., Xing M., Wang P.G. Relationship between the ABO blood group and the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:328–331. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet North Am. Ed. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zietz M., Zucker J., Tatonetti N.P. Associations between blood type and COVID-19 infection, intubation, and death. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5761. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19623-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.