Abstract

Objectives

Using ultrasound (US) scanning to examine the correlation between increase of common fibular nerve's (CFN) cross sectional area (CSA) and functional impairment of foot dorsiflexor muscles as an early sign of peripheral neuropathy.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

In-patient rehabilitation unit between November 2020 and July 2021.

Participants

Twenty-six inpatients who underwent prolonged hospitalization in intensive care units (ICUs) and were diagnosed with critical illness myopathy and polyneuropathy after SARS-COV-2 infection (N=26). Physical examination and US scanning of the CFN and EMG/ENG were carried out on each patient.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

CFN's CSA at the peroneal head.

Results

We verified a significant increase in the CSA of the CFN measured at the peroneal head in more than 90% of the nerves tested. A cut off value of CFN's CSA of 0.20 cm was used to identify pathologic nerves. No correlations with other variables (body mass index, ICU days) were found.

Conclusion

US scanning of the CFN appears to be an early and specific test in the evaluation of CPN's abnormalities in post COVID-19 patients. US scanning is a reproducible, cost effective, safe, and easily administered bedside tool to diagnose a loss of motor function when abnormalities in peripheral nerves are present.

Keywords: COVID-19, Intensive care units, Peroneal nerve, Rehabilitation, Ultrasound

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic generated an extraordinarily high need for intensive care during its peak and, as a consequence, a series of health issues such as acquired neuromuscular disorders.1 , 2 It is widely acknowledged that COVID-19 can influence the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS).3

Effects on CNS, caused directly or indirectly by the virus, have been largely investigated: most of the patients developed encephalitis or hyper coagulable states leading to stroke. Acute neuropathies such as Guillan-Barré syndrome have also been found.4 , 5 However, the pathogenesis of peripheral nerve involvement has been rarely investigated.6, 7

An autoptic study of femoral nerve samples demonstrated inflammatory/immune-mediated damage, although no evidence of a direct SARS-CoV-2 invasion was found.8 It has been suggested that the primary cause for neurologic disease of CNS and PNS is an autoimmune mediated mechanism.9

Patients in intensive care units (ICUs) often develop several complications due to prolonged immobilization especially when in a prone position; these include neuromuscular complications, severe muscle weakness and fatigue, joint stiffness, dysphagia, psychological problems, reduced mobility, severely impaired quality of life, frequent falls, and even quadriparesis.10 , 11

Muscle wasting and paralysis are common clinical features, attributed to critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP), myopathy (CIM), or a combination of both (CRIMYNE).12 , 13

Diagnosis is challenging in comatose patients as Medical Research Council (MRC) is not applicable.14 Conventional electroneurographic and electromyographic (ENG/EMG) studies require specialized personnel, are time-consuming, and do not allow diagnosis of small intra-epidermal nerve fiber pathology. Considering the high prevalence of ICU-acquired neuromuscular disorders, it is unrealistic for conventional ENG/EMG to be used as a large-scale screening tool. As an effective diagnostic test, the peroneal nerve test (PENT) is used to diagnose critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy in the ICU. PENT can accurately exclude CIP or CIM if the result is in the norm but an abnormal result cannot discriminate between CIP, CIM, or CRIMYNE.15

In our clinical observation in a rehabilitation inpatient unit, many post-intensive care patients diagnosed with CRIMYNE had weakened foot dorsiflexor muscles, suggesting a peroneal nerve neuropathy. This condition has a severe effect on walking and may be described as “long-COVID disability” or “long ICU disability”.16

Nearly half of the patients presented unilateral signs, not a typical presentation of critical illness. The clinical picture could be attributed to a multifactorial mononeuropathy of the common fibular nerve (CFN).17

High-resolution ultrasound (US) scanning seems to be a very convenient first-line imaging modality for the diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment of peripheral nerve pathologies.12 , 18

The aim of this study is to investigate the association between US CFN modification and clinical foot dorsiflexion impairment.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This retrospective observational study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the LAZIO 2 Ethics Committee (Protocol number: 0202810/2021). All participants were fully informed of the study objectives and accepted data sharing and privacy policy. We received written consent from all patients.

Participants

Our sample was made up of 26 patients (18 men and 8 women) with critical illness myopathy and polyneuropathy diagnosed in previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Patients were evaluated, and data collected between November 2020 and July 2021 during a stay in an in-patient rehabilitation unit. All patients were between 40 and 80 years old, the average being 64.5 years, and had been diagnosed with COVID-19 infection that required respiratory support in an ICU. All patients had been intubated, mechanically ventilated, and had undergone prone positioning for a prolonged period of time in ICU (average time of ICU stay: 40 days). None of them had previous pathologic conditions of the CNS or PNS. Only 3 patients presented a normal body mass index (BMI), 15 patients were overweight, and 8 patients were obese class I or II (average BMI: 26.6) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Population's data.

| ID | Sex | Age | BMI | ICU Days | MRC TA/EHL R T0 | MRC TA/EHL L T0 | MRC TA/EHL R T1 | MRC TA/EHL L T1 | EMG/ENG | CSA CFN R (cm2) | CSA CFN L (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 53 | 27.8 | 32 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | Y | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| 2 | M | 66 | 26 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.23 | 0.32 |

| 3 | M | 40 | 29.3 | 33 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | Y | 0.24 | 0.12 |

| 4 | M | 69 | 36.9 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.17 | 0.34 |

| 5 | M | 40 | 29.3 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.49 | 0.27 |

| 6 | F | 78 | 27.2 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| 7 | F | 69 | 27.3 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 | Y | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| 8 | F | 70 | 28 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Y | 0.24 | 0.17 |

| 9 | F | 80 | 25 | 38 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Y | 0.22 | 0.26 |

| 10 | M | 58 | 23 | 37 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | Y | 0.28 | 0.24 |

| 11 | M | 72 | 27 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.29 | 0.36 |

| 12 | F | 61 | 28 | 37 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Y | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| 13 | M | 77 | 26.1 | 43 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Y | 0.23 | 0.27 |

| 14 | F | 76 | 24.2 | 53 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | Y | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| 15 | M | 58 | 29.3 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.31 | 0.24 |

| 16 | M | 69 | 30 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.28 | 0.32 |

| 17 | M | 57 | 30.4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| 18 | M | 77 | 35 | 51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Y | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| 19 | F | 78 | 35.1 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| 20 | M | 58 | 30 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | N | 0.22 | 0.20 |

| 21 | M | 62 | 36 | 59 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | N | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| 22 | M | 71 | 26 | 41 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Y | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| 23 | M | 58 | 30 | 38 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | Y | 0.20 | 0.09 |

| 24 | F | 67 | 24.9 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | N | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| 25 | M | 58 | 22.4 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | Y | 0.17 | 0.29 |

| 26 | M | 56 | 39.1 | 31 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | Y | 0.31 | 0.16 |

Abbreviations: F, female; ID, Identification number; L, left; M, male; N, not performed; R, right; T0, time zero at admission; T1, time 1 at discharge; TA, tibialis anterior muscle; Y, performed.

Data

A physical examination was performed upon admission (T0) and discharge (T1) including the MRC scale for muscle strength.14 , 19 Particular attention was given to the tibialis anterior muscle and extensor hallucis longus muscle (EHL).

US scanning of the CFN was carried out bilaterally for each patient as compression and entrapment neuropathies are frequent in ICUs.20, 21, 22 The exam was performed with Sonoscape X3 US system with a linear probe (4-16 MHz) by 2 physicians each with at least 5 years of experience in diagnostic and interventional skeletal-muscle US.

CFN was examined along its course from its origin as a terminal branch of the sciatic nerve at the superior angle of the popliteal fossa, to the peroneal head.23 The CFN nerve's CSA was measured in short axis at the peroneal head (Fig. 1 ).

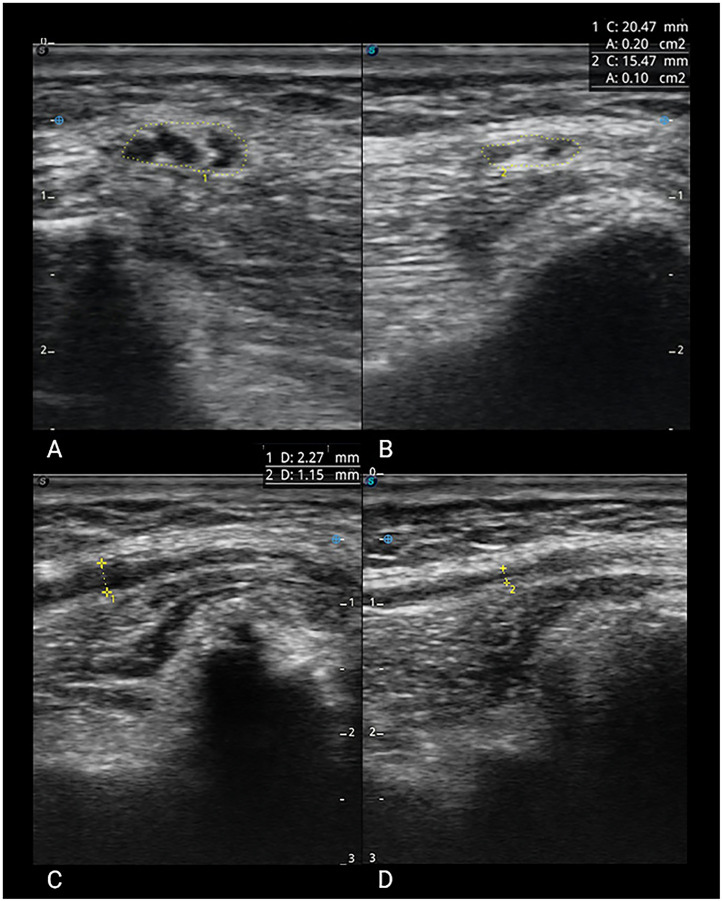

Fig 1.

Common fibular nerve. In purple: peroneal head: in yellow: CFN's CSA; in blue: focal intraneural fascicular hypoechoic enlargement.

We also studied the nerve in long axis in order to report potential qualitative abnormalities.24 , 25 All procedures described took place at bedside.

Neurophysiological investigations (ENG/EMG) of the main peripheral nerves were also done in those patients with an significant impairment of foot dorsiflexion and/or EHL dysfunction (MRC<3).

We examined a total sample of 52 CFNs and their corresponding CSA.

These 52 CSA values of CFN were divided into 2 groups, A and B, based on the associated dorsiflexor muscles MRC score.26 , 27 We also evaluated other variables that could influence the pathogenesis of the functional impairment. In particular, we analyzed the number of days in ICU and the patient's BMI at their admission in ICU.

Statistical analysis

Data distribution was checked using the Lilliefors test. Next, groups were compared by Student t test (P<.05) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig 2.

Group A (blue)-group B (red) normal distribution (ND).

In addition, we used Pearson correlation index to individually compare the nerve's cross sectional area with patients’ BMI and the ICU hospitalization days.

Data availability

Anonymized data from this study are available upon request.

Results

The data collected indicate a difference in terms of CSA between the 2 groups. Group A (37 CFN) presented a MRC<3 and group B (15 CFN) presented a MRC≥3 (Tables 2 and 3 ). Group A: mean=0.26 mm2, SD=0.06; Group B: mean=0.15 mm2, SD=0.04, P=.00000003 (Table 4 ; Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Group A statistical results: average, SD.

| Group A MRC <3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| MRC | CFN's CSA | ND |

| 0 | 0.17 | 2.2703794 |

| 0 | 0.17 | 2.2703794 |

| 1 | 0.18 | 2.8291444 |

| 0 | 0.20 | 4.0628121 |

| 0 | 0.20 | 4.06 |

| 0 | 0.21 | 4.6821107 |

| 0 | 0.21 | 4.6821107 |

| 0 | 0.21 | 4.6821107 |

| 2 | 0.22 | 5.2570574 |

| 0 | 0.22 | 5.2570574 |

| 0 | 0.22 | 5.2570574 |

| 0 | 0.23 | 5.7508209 |

| 2 | 0.23 | 5.7508209 |

| 0 | 0.23 | 5.7508209 |

| 0 | 0.23 | 5.7508209 |

| 0 | 0.24 | 6.1291896 |

| 0 | 0.24 | 6.1291896 |

| 2 | 0.24 | 6.1291896 |

| 0 | 0.24 | 6,1291896 |

| 1 | 0.24 | 6.1291896 |

| 0 | 0.25 | 6.3644717 |

| 0 | 0.26 | 6.4388417 |

| 0 | 0.27 | 6.3465723 |

| 0 | 0.27 | 6.3465723 |

| 0 | 0.28 | 6.0947627 |

| 0 | 0.28 | 6.0947627 |

| 0 | 0.29 | 5.7024366 |

| 0 | 0.29 | 5.7024366 |

| 1 | 0.31 | 4.6166404 |

| 0 | 0.31 | 4.6166404 |

| 0 | 0.31 | 4.6166404 |

| 0 | 0.32 | 3.9947351 |

| 0 | 0.32 | 3.9947351 |

| 0 | 0.32 | 3.9947351 |

| 0 | 0.34 | 2.7661142 |

| 0 | 0.36 | 1.7258243 |

| 0 | 0.49 | 0.0063417 |

| Average | 0.26 | |

| SD | 0.06 | |

Abbreviation: ND, normal distribution.

Table 3.

Group B statistical results: average, SD.

| Group B MRC≥3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| MRC | CFN's CSA | ND |

| 3 | 0.09 | 3.1660721 |

| 4 | 0.09 | 3.17 |

| 4 | 0.10 | 4.48 |

| 3 | 0.12 | 7.4274964 |

| 4 | 0.12 | 7.4274964 |

| 4 | 0.15 | 9.95 |

| 3 | 0.15 | 9.9514669 |

| 3 | 0.16 | 9.6866535 |

| 4 | 0.16 | 9.6866535 |

| 4 | 0.16 | 9.6866535 |

| 4 | 0.17 | 8.86 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 8.8599170 |

| 4 | 0.20 | 4.67 |

| 5 | 0.22 | 4.67 |

| 5 | 0.22 | 2.2297051 |

| Average | 0.15 | |

| SD | 0.04 | |

Abbreviation: ND, normal distribution.

Table 4.

Student t test Group A-Group B (P<.05).

| Group | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 37 | 15 |

| Average | 0.26 | 0.15 |

| Standard deviation | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Student t test | 6.52 | |

| Degrees of freedom | 50 | |

| P value | .00000003 | |

Statistical analysis did not indicate a linear correlation between the increase of CSA and a higher BMI at admission in ICU, or a linear correlation between CSA and a longer ICU hospitalization.

Discussion

All patients examined had previously had a prolonged ICU stay (from 7 to 90 days) for COVID-19 related complications. All of them had CRIMYNE diagnosis (based on clinical examination performed in ICU). Our clinical examination was performed at T0 with MRC. Most of the patients presented impairment in foot dorsiflexor muscles, suggesting a peroneal nerve neuropathy. This latter group underwent ENG/EMG examination that confirmed the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy.

50% of all patients presented bilateral impairment at admission. 37.5% presented unilateral signs atypical in a critical illness. In fact, critical illness polyneuropathy is typically symmetrical and often predominant in the proximal part of the limbs.19 , 28

Therefore, we performed US scanning of the CFN in order to confirm existence of an anatomic modification involving the nerve or the surrounding soft tissues that could explain the high unilateral rate of impairment.

The most consistent finding was an increase of the CSA of the affected CFN at the peroneal head.

When tibialis anterior muscle or EHL muscular impairment rated from 0 to 2 MRC points (0= no visible contraction, 1= visible contraction but no movement, 2= active movement but not against gravity), the corresponding CFN presented a major increase in CSA. On the contrary, the CSA of the CFN supplying unaffected muscles with a MRC≥3 (3= active movement against gravity, 4= active movement against gravity and resistance, 5= normal power) were usually within normal values.14

According to existent literature, normal values of CFN's CSA range from 11.7 mm2 to 17.8 mm2.29 , 30 No specific value for pathologic nerve's CSA has been clearly demonstrated.

In our sample, CSAs in Group B (MRC≥3) ranged from 0.09 cm2 to 0.22 cm2. Group A (MRC<3) showed values of CSA ranging from 0.17 cm2 to 0.49 cm2 (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 2).

Considering the mean value of CSA in each group and comparing their SD, we obtained a value of 0.20 cm2 which seems appropriate as a cut off to screen the presence of CFN neuropathy.

These encouraging data could be further supported by a larger sample which could confirm this significant statistical value.

In addition, during the US examination, we noted not only the abovementioned quantitative modifications but also significant qualitative abnormalities. Those most common were focal fascicular intraneural hypoechoic enlargement, fibrotic reactions, and changes in shape like “hourglass” aspect of the fascicles (Fig. 3 ).

Fig 3.

Comparison between normal and pathological CFN. (A) Short axis of abnormal nerve with CSA of 0.20 cm2. (C) Severe focal fascicular intraneural hypoechoic enlargement. (B) Short axis and (D) long axis of a normal nerve.

Considering other variables, we assumed that a high BMI could influence peripheral nerve abnormalities. According to Tagliafico et al, physiological nerve sizes had a minimum correlation with height and age but demonstrated a significant correlation with weight and BMI.30

Our data did not demonstrate a correlation between increased CSA and BMI alone. In fact, current literature underlines that BMI variations may facilitate the occurrence of peripheral neuropathies.20 , 31

According to Papagianni et al, BMI variations can be a predisposing factor of nerve mononeuropathy. Peroneal nerve is susceptible to injuries due to its anatomic course. Excessive weight loss can reduce the fatty cushion protecting the nerve and is considered a common underlying cause of peroneal palsy.31

Our study suggests that it's more important to consider ample weight fluctuations than BMI itself.

Because CRIMYNE is a frequent complication in ICU patients, we also focused on the length of stay in ICU.1 We evaluated the possibility of a correlation between a higher nerve's CSA (and therefore functional impairment) and a longer hospitalization in ICU. We found no correlation, probably due to our limited sample. We suggest further studies with more patients.

Based on our results, considering clinical and imaging findings, we are inclined to ascertain that the damage to the peripheral nerves could be co-induced by some mechanical factors present in ICUs.32

Indeed compression injuries can cause peripheral neuropathies, as observed in patients hospitalized in ICUs and submitted to invasive ventilation and prone positioning, as described by Brugliera et al.20

Prone positioning has been recommended to treat ARDS in COVID-19 patients because it improves ventilation. However, several neurologic issues may arise from prone positioning such as brachial plexus damage, radial, median, and sciatic nerve injury.33

As a result of these studies, we believe that an early diagnosis of neuropathy could allow for early treatment of this condition and promote a correct positioning of patients. The US scanning directly in ICU could be crucial in the diagnosis of nerve compression damages before they become clinically evident as a peripheral neuropathy.

Future studies could be useful in order to understand which positions could generate CFN damage and how to prevent it.

Study limitations

The limitations of this study are the retrospective nature, the small sample, and the fact that data collection occurred not directly in ICU but during the convalescence of patients in rehabilitation setting.

Possible selection bias could be related to the observational design of the study. One other defect in our study was the absence of a no post COVID control group affected by CFN neuropathy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that US could be a non-invasive, easily reproducible, sensitive and readily available method to recognize early signs of peripheral neuropathy of CFN.

A cut-off of 0.20 cm2 for CFN's CSA, confirmed by a larger sample in future studies, could also be used as a screening value during bedside US scanning of CFN neuropathy in ICU and post ICU patients. In addition, completion of conventional ENG/EMG may require up to 90 minutes, it is unrealistic as a large-scale screening tool and the PENT cannot discriminate between CIP, CIM, or CRIMYNE. On the other hand, US scanning of CFN can be used to discriminate between CIM and CIP.

We also insist on the importance of further study of the pathogenic mechanisms involved in CFN (and other peripheral nerves) damage, in order to suggest guidelines for care of patients in ICU units. Our goal is to avoid negative functional outcomes such as walking and balance impairment (with increased risk of falling) and postural pain (“long-COVID or long ICU disability”) that come with a high economic and social cost.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.Guarneri B, Bertolini G, Latronico N. Long-term outcome in patients with critical illness myopathy or neuropathy: the Italian multicentre CRIMYNE study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:838–841. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.142430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paliwal VK, Garg RK, Gupta A, Tejan N. Neuromuscular presentations in patients with COVID-19. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:3039–3056. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04708-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andalib S, Biller J, Di Napoli M, et al. Peripheral nervous system manifestations associated with COVID-19. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021;21:9. doi: 10.1007/s11910-021-01102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:767–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin JE, Asfour A, Sewell TB, et al. Neurological issues in children with COVID-19. Neurosci Lett. 2021;743 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estraneo A, Ciapetti M, Gaudiosi C, Grippo A. Not only pulmonary rehabilitation for critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Neurol. 2021;268:27–29. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10077-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diamond KB, Weisberg MD, Ng MK, Erez O, Edelstein D. COVID-19 peripheral neuropathy: a report of three cases. Cureus. 2021;13:e18132. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suh J, Mukerji SS, Collens SI, et al. Skeletal muscle and peripheral nerve histopathology in COVID-19. Neurology. 2021;97:e849–e858. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nersesjan V, Amiri M, Lebech AM, et al. Central and peripheral nervous system complications of COVID-19: a prospective tertiary center cohort with 3-month follow-up. J Neurol. 2021;268:3086–3104. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10380-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stam HJ, Stucki G, Bickenbach J. Covid-19 and post intensive care syndrome: a call for action. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52:19–22. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demeco A, Marotta N, Barletta M, et al. Rehabilitation of patients post-COVID-19 infection: a literature review. J Int Med Res. 2020;48 doi: 10.1177/0300060520948382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolton CF. Neuromuscular manifestations of critical illness. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:140–163. doi: 10.1002/mus.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bocci T, Campiglio L, Zardoni M, et al. Critical illness neuropathy in severe COVID-19: a case series. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:4893–4898. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05471-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanpee G, Hermans G, Segers J, Gosselink R. Assessment of limb muscle strength in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:701–711. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latronico N, Nattino G, Guarneri B, Fagoni N, Amantini A, Bertolini G. Validation of the peroneal nerve test to diagnose critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy in the intensive care unit: the multicentre Italian CRIMYNE-2 diagnostic accuracy study. F1000Res. 2014;3:127. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.3933.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oaklander AL, Mills AJ, Kelley M, et al. Peripheral neuropathy evaluations of patients with prolonged long COVID. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9:e1146. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daia C, Toader C, Scheau C, Onose G. Motor demyelinating tibial neuropathy in COVID-19. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120:2032–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2021.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kara M, Özçakar L, De Muynck M, Tok F, Vanderstraeten G. Musculoskeletal ultrasound for peripheral nerve lesions. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48:665–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, et al. Groupe de Réflexion et d'Etude des Neuromyopathies en Réanimation. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2002;288:2859–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugliera L, Filippi M, Del Carro U, et al. Nerve compression injuries after prolonged prone position ventilation in patients with SARS-CoV-2: a case series. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:359–362. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.10.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez CE, Franz CK, Ko JH, et al. Imaging review of peripheral nerve injuries in patients with COVID-19. Radiology. 2021;298:E117–E130. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020203116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoira E, Elzi L, Puligheddu C, Garibaldi R, Voinea C, Chiesa AF. High prevalence of heterotopic ossification in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1049–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reebye O. Anatomical and clinical study of the common fibular nerve. Part 1: anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26:365–370. doi: 10.1007/s00276-004-0238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nwawka OK, Lee S, Miller TT. Sonographic evaluation of superficial peroneal nerve abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:872–879. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beekman R, Visser LH. High-resolution sonography of the peripheral nervous system—a review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:305–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latronico N, Gosselink R. A guided approach to diagnose severe muscle weakness in the intensive care unit. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva. 2015;27:199–201. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20150036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carolus AE, Becker M, Cuny J, Smektala R, Schmieder K, Brenke C. The interdisciplinary management of foot drop. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int. 2019;116:347–354. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tankisi H, de Carvalho M, ZʼGraggen WJ. Critical illness neuropathy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;37:205–207. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cartwright MS, Passmore LV, Yoon JS, Brown ME, Caress JB, Walker FO. Cross-sectional area reference values for nerve ultrasonography. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:566–571. doi: 10.1002/mus.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tagliafico A, Cadoni A, Fisci E, Bignotti B, Padua L, Martinoli C. Reliability of side-to-side ultrasound cross-sectional area measurements of lower extremity nerves in healthy subjects. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:717–722. doi: 10.1002/mus.23417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papagianni A, Oulis P, Zambelis T, Kokotis P, Koulouris GC, Karandreas N. Clinical and neurophysiological study of peroneal nerve mononeuropathy after substantial weight loss in patients suffering from major depressive and schizophrenic disorder: suggestions on patients’ management. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2008;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1749-7221-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finsterer J, Scorza FA, Scorza CA, Fiorini C. Peripheral neuropathy in COVID-19 is due to immune-mechanisms, pre-existing risk factors, anti-viral drugs, or bedding in the intensive care unit. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2021;79:924–928. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X-ANP-2021-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goettler CE, Pryor JP, Reilly PM. Brachial plexopathy after prone positioning. Crit Care. 2002;6:540–542. doi: 10.1186/cc1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data from this study are available upon request.