Abstract

Morrison's pouch is the intraperitoneal space in the supramesocolic compartment located between the right liver lobe and right kidney. Pathological conditions that can involve this peritoneal space include fluid collections, infectious or inflammatory processes, and neoplasms. Frequent involvement by disease entities can be attributed to its dependent location, communication with the inframesocolic compartment, close proximity to the adjacent organs and peritoneal fluid dynamics. Knowledge of the appearance of pathological entities on various imaging modalities helps the radiologist in making the correct diagnosis.

Keywords: CT scan, Morrison's pouch, MRI, peritoneal space

Introduction

Morrison's pouch or hepatorenal pouch is the most dependent intraperitoneal space in the supramesocolic compartment. Because of its dependent location and close relation to various organs, numerous pathological entities can involve this space either directly or indirectly by peritoneal spread. In this review, we would like to present a brief radiological anatomy of Morrison's pouch and describe various pathological conditions involving this peritoneal space.

Peritoneal Anatomy

Peritoneum is a complex serous membrane derived from the mesoderm. It forms a closed sac in males, but in females it is open at lateral ostia of the fallopian tubes. One of its major functions is to limit the spread of a disease, but it is also a potential pathway for intraperitoneal and subperitoneal disease spread. 1

Peritoneum has two layers, parietal and visceral, which are lined by the mesothelium. Abdominal wall is lined by parietal peritoneum, whereas abdominal and pelvic organs are covered by visceral peritoneum. The space between parietal and visceral peritoneum is called peritoneal cavity, which is a single continuous fluid-containing space. Peritoneum folds to form ligaments, mesentery, and omentum. Mesentery, which is a double fold of peritoneum, is further divided into dorsal and ventral portions by primitive gut tube. Dorsal mesentery extends from the foregut to hindgut, whereas ventral mesentery exists only in the foregut. Development of the liver divides the ventral mesentery into lesser omentum and falciform ligament. These peritoneal reflections and mesentery divide the peritoneal cavity into several communicating spaces.

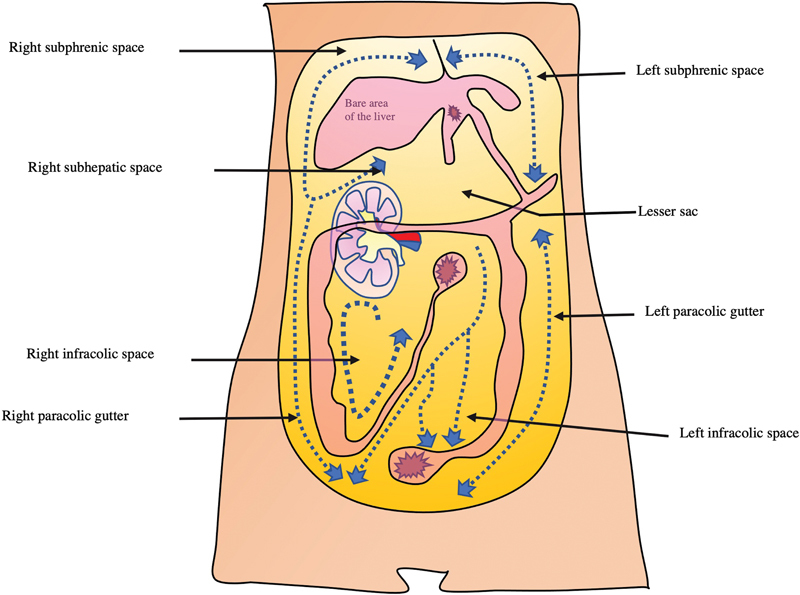

Transverse mesocolon divides the peritoneal cavity into two main compartments, supramesocolic and inframesocolic. Supramesocolic compartment is subdivided into right and left by falciform ligament. Right supramesocolic space is further divided into right subphrenic space, right subhepatic space (hepatorenal pouch or Morrison's pouch), and lesser sac. The focus of this article is to highlight the radiologic anatomy of right subhepatic space and imaging appearances of its various pathologies.

Morrison's Pouch (Hepatorenal Pouch/Right Subhepatic Space)

Morrison's pouch lies between the upper pole of the right kidney and inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver ( Fig. 1 ). Superiorly, it is bounded by the inferior layer of coronary ligament, posteriorly by the anterior surface of the upper pole of the right kidney, laterally by parietal peritoneum lining the right lateral abdominal wall, inferomedially by hepatic flexure of colon, transverse mesocolon and second part of duodenum. It is the most gravity-dependent space in supramesocolic compartment. 2 Hepatorenal space is separated from anterior pararenal space by parietal peritoneum. It communicates with the right paracolic space inferiorly and right subhepatic space superiorly.

Fig. 1.

Representative image of the peritoneal space. Right subhepatic space is the Morrison's pouch. Dotted line represents the direction of peritoneal flow through which the intraperitoneal spread of malignancy or infection can occur.

Peritoneal Spread of Disease

Peritoneal fluid is constantly circulating throughout the peritoneal spaces under the influence of gravity and intraperitoneal pressure. Intraperitoneal pressure is negative in subdiaphragmatic location and further decreases during inspiration. Negative pressure results in the flow of peritoneal fluid upward toward the diaphragm through paracolic spaces. Rectouterine pouch in females and rectovesical pouch in males is the most gravity-dependent intraperitoneal space. 3 Right paracolic space freely communicates with the supramesocolic compartment superiorly and pelvis inferiorly through which malignancy and infection can spread. In contrast, left paracolic space is smaller and superiorly phrenico-colic ligament partially limits the passage of peritoneal fluid to the supramesocolic compartment. 2

Imaging Modalities

Ultrasonography (USG) is a readily available, safe, and cost-effective imaging tool for investigation of intraperitoneal pathologies. It is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) for the detection of intraperitoneal fluid and is widely used in trauma settings for the same. 4 Right upper quadrant view or Morrison's pouch view is one of the four views used for the detection of hemoperitoneum during eFAST.

Multidetector CT allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of intraperitoneal pathologies. Good-quality sagittal and coronal reformats aid in delineating the full extent of the disease. 2

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has superior contrast resolution and better characterizes the contents of fluid collections. However, lower spatial resolution and motion artifacts are setbacks. 2

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan has a role in the detection of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Fusion FDG PET/CT imaging has higher sensitivity in its detection than PET or CT imaging alone. 5

Pathologies of Morrison's pouch

Fluid Collections

Ascites

In healthy individuals, the peritoneal cavity contains ∼50 to 75 mL of clear fluid. 4 Abnormal collection of fluid between parietal and visceral peritoneum is called ascites that may be caused by a variety of pathological entities. Ascitic fluid can have low protein concentration (transudate) or high protein concentration (exudate). Common causes of transudative ascites include cirrhosis, congestive cardiac failure, hypoproteinemia, and renal failure. Several conditions can result in exudative intraperitoneal collection such as peritonitis (bacterial or tubercular), malignant ascites, hepatic vein outflow tract obstruction, pancreatitis ( Fig. 2 ), chylous ascites, etc. Peritoneal, mesenteric thickening, and abnormal peritoneal enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT/MRI favors exudative causes. Infectious causes result in smooth peritoneal thickening and enhancement, whereas peritoneal and omental nodularity favors malignant causes. 6 However, tuberculosis can also result in nodular lesions and omental thickening mimicking malignant causes. 7 Unless loculated, ascitic fluid usually accumulates in Morrison's pouch ( Fig. 3 ).

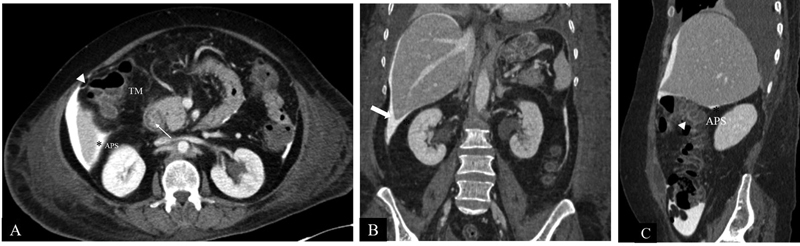

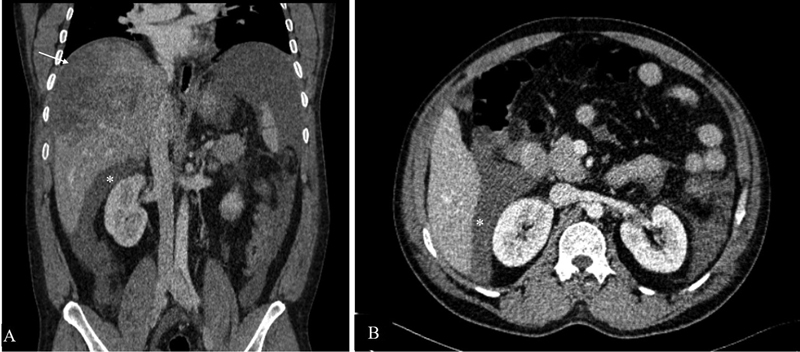

Fig. 2.

Ascites. Contrast-enhanced axial ( A ) and coronal ( B ) CT images in a 40-year-old patient in a patient with acute pancreatitis showing a large pseudocyst (central walled off cystic lesion) and ascitic fluid (arrow) accumulating in Morrison's pouch (*).

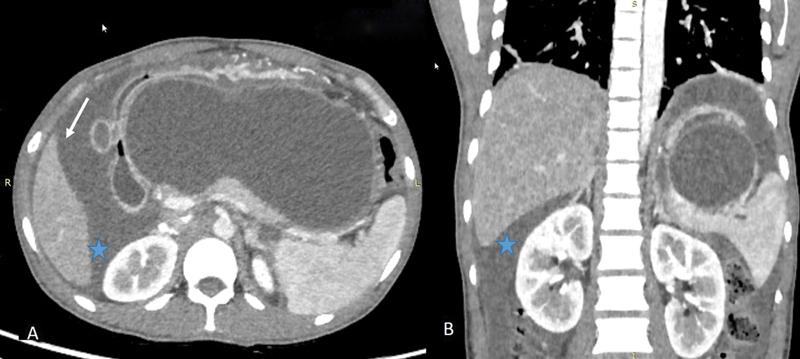

Fig. 3.

CT Anatomy of Morrison's pouch. Axial CECT image ( A ) shows intraperitoneal contrast outlining the peritoneum. Morrison's pouch (*) is the space between the right kidney and the right liver lobe. Hepatic flexure of the colon (arrowhead), transverse mesocolon (TM), and duodenum (line arrow) are seen anteromedially. Posteriorly, the parietal peritoneum separates the anterior pararenal space (APS) from Morrison's pouch (*). Coronal reformatted CT image ( B ) shows Morrison's pouch (*) between the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver and the upper pole of the right kidney. Laterally, limited by parietal peritoneum (block arrow) lining the right lateral abdominal wall. Sagittal-reformatted CT image ( C ) shows Morrison's pouch (*) between the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver and upper pole of the right kidney. Parietal peritoneum separates the anterior pararenal space (APS) from Morrison's pouch. Anteroinferiorly, hepatic flexure of the colon (arrowhead) is seen.

Hemoperitoneum

Hemoperitoneum can result from traumatic, nontraumatic, or iatrogenic causes. Common causes include trauma, complications of surgery, coagulopathies, rupture of the ovarian cyst or ectopic pregnancy, aneurysm rupture, or tumoral bleeding.

USG appearance is variable ranging from anechoic/hypoechoic fluid collections to echogenic organized hemorrhage. CT shows high attenuation fluid (>30 HU) with variable appearance depending upon the age, extent, and location of hemorrhage. Acute hemorrhage is hyperdense with attenuation of 30 to 45 HU. Organized hematoma is even more hyperdense with attenuation value of 45 to 70 HU ( Fig. 4 ). However, these values may differ depending upon the hemodynamic status of patient as hemoperitoneum in patients with low hematocrit level may have lesser attenuation values even during acute stage. 8

Fig. 4.

Hematoma. Contrast-enhanced arterial phase axial ( A ) and coronal ( B ) computed tomography images in a 28-year-old male patient with history of trauma showing a high-density hematoma in the perihepatic space (arrow) and in hepatorenal pouch (*).

In the setting of liver trauma or rupture of liver tumor, blood flows caudally from perihepatic space and gets accumulated in Morrison's pouch ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Hemoperitoneum. Contrast-enhanced coronal ( A ) and axial ( B ) CT scan in a 41-year-old patient with history of road traffic accident and positive extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST) showing grade 4 liver injury (arrow) along with high-density fluid in Morrison's pouch (*) suggestive of hemoperitoneum.

Adrenal Hemorrhage

A large adrenal hematoma can result in mass effect on surrounding organs and may bulge into Morrison's pouch. Trauma and nontraumatic conditions such as hypovolemia, stress, anticoagulants, bleeding diathesis, and adrenal tumors can result in adrenal hemorrhage. Its appearance varies depending upon the age. USG during acute stage shows a predominantly solid avascular echogenic mass in the suprarenal location. As it ages, central areas of hematoma liquefy and demonstrate mixed echogenicity. On CT, acute or subacute hematoma has higher attenuation. Attenuation decreases over time. The MR appearance of hematoma ( Fig. 6 ) changes according to the stage of hemoglobin degradation. 9

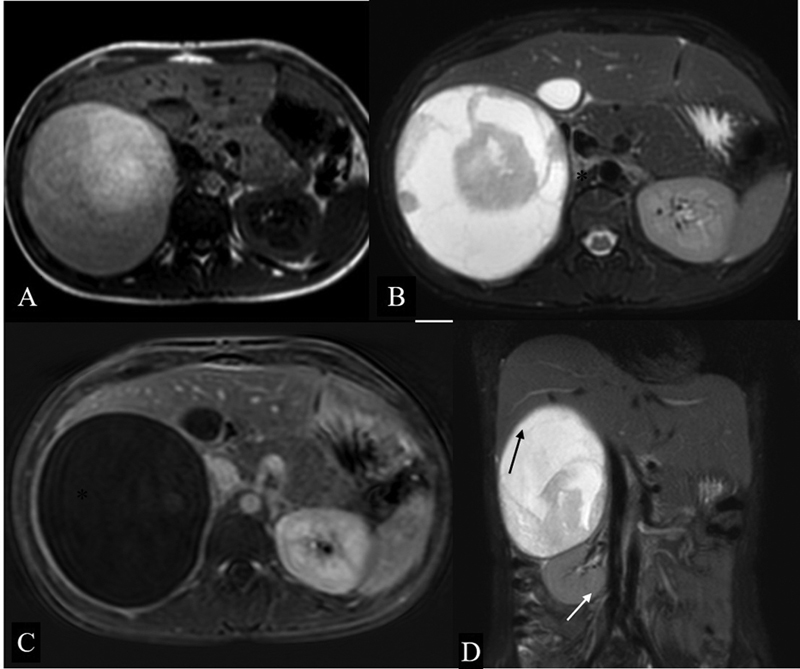

Fig. 6.

Adrenal hematoma. Axial T1-Weighted ( A ) and T2W FS ( B ) image showing a well-defined heterogeneously hyperintense lesion (*) in the right suprarenal location causing mass effect on the right lobe of the liver. Subtracted post contrast sequence ( C ) shows no enhancing component in this lesion. Coronal T2-weighted fat-saturated image ( D ) showing that the lesion is causing inferior displacement of the right kidney (white arrow), effacement of hepatorenal space, and mass effect on the liver (black arrow).

Infectious Conditions

Peritoneal Tuberculosis

Peritoneum is commonly involved in tuberculosis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis may reach the peritoneum by hematogenous or lymphatic route, direct extension from bowel, discharge of caseous material from the lymph nodes or peritoneal spill from tubercular salpingitis. Three types have been described: wet type, fibrotic type, and dry type. 10

Imaging features vary according to the type of peritoneal involvement although considerable overlap has been described in their imaging appearance. 10 Free or loculated ascites may be seen in the wet type of peritoneal tuberculosis. Free ascites favors dependent peritoneal spaces, including Morrison's pouch, and it may be accompanied by peritoneal thickening and enhancement ( Fig. 7 ). Fibrous adhesions, mesenteric thickening, and caseous nodules may be seen in the dry type. Fibrotic type shows omental and mesenteric thickening with cakelike masses. 10

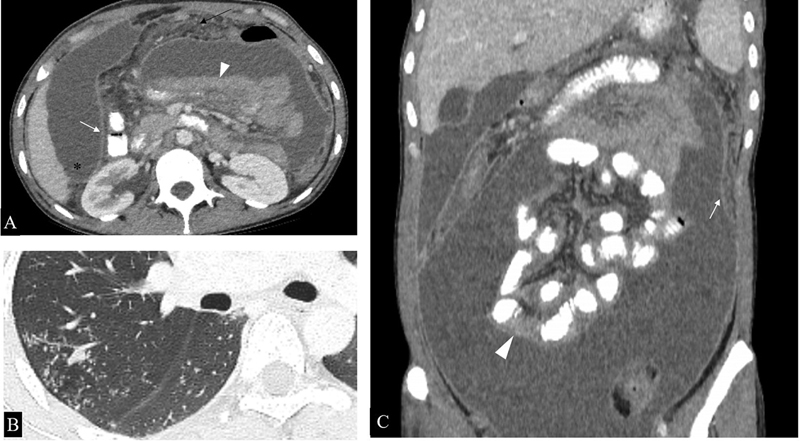

Fig. 7.

Peritoneal involvement in a microbiologically proven case of disseminated tuberculosis. ( A ). Axial CT sections show loculated ascites, smooth peritoneal thickening, and enhancement (white arrow), omental thickening (black arrow) and clumped bowel loops (arrowhead). Ascitic fluid can be seen extending into Morrison's pouch (*). ( B ) Axial section of the chest shows numerous centrilobular nodules in a tree and bud configuration (*), further supporting the imaging diagnosis of tuberculosis in this case. ( C ) Coronal reformatted image better demonstrates clumped small bowel loops (arrowhead) along with peritoneal thickening and enhancement (arrow).

Imaging differential diagnosis includes peritoneal carcinomatosis and primary peritoneal malignancies such as peritoneal mesothelioma. Irregular peritoneal thickening and nodular implants suggest peritoneal carcinomatosis, while smooth peritoneal thickening favors peritoneal tuberculosis. However, omental thickening and nodular peritoneal thickening in tuberculosis commonly occur and render differentiation from malignant causes difficult. 7

Abscess

An abscess is a localized collection of pus caused by bacterial, fungal, or amoebic infections. Spread of infection from the inframesocolic compartment through the right paracolic space or from supramesocolic pathologies such as ruptured hepatic abscess, subdiaphragmatic abscess, and retained gall stones can result in abscess formation in Morrison's pouch ( Fig. 8 ). Its radiological appearance is variable according to the stage and amount of liquefactive necrosis. In early stages, it appears as a soft tissue mass with surrounding fat stranding. Mature abscesses have a well-defined, irregular, and heterogeneously enhancing wall with central nonenhancing necrotic debris.

Fig. 8.

Ruptured hepatic abscess. ( A ) Sagittal sections of contrast-enhanced CT in a 52 year-old-male patient presenting with high-grade fever and pain in the abdomen showing hepatic abscess in segments VI and VII (*) with discontinuity in hepatic surface, subdiaphragmatic (black arrow), hepatorenal pouch fluid (white arrow) and, ipsilateral pleural effusion (arrowhead). ( B ) Axial sections of the same patient better demonstrate the hepatorenal pouch fluid collection (white arrow).

Inflammatory Conditions

Acute Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis is the most common inflammatory condition of the gallbladder. It can be seen in the setting of cholelithiasis, known as calculous cholecystitis or in the absence of gall stone disease in critically ill patients, known as acalculous cholecystitis. CT features of acute cholecystitis include gall bladder wall thickening, mural hyperenhancement, pericholecystic fat stranding, and pericholecystic fluid. This fluid may remain limited to pericholecystic location or may show extension posteriorly into Morrison's pouch ( Fig. 9 ). 11

Fig. 9.

Acute cholecystitis in a 75 year-old patient presenting with upper abdominal pain. Axial contrast-enhanced CT images show a distended gall bladder, enhancing wall, layering of the hyperdense sludge (arrow) and pericholecystic fluid extending into the hepatorenal pouch (*).

Retained Gall Stones

Retained gall stones is a frequent complication of cholecystectomy. Perforation of the gallbladder during the procedure results in gall stone spillage, incidence of which has increased with the use of laparoscopic technique. Morrison's pouch is one of the common sites. Patient may remain asymptomatic or may develop complications such as abscess and fistula formation. 12 Pigmented gallstones are more likely to be infected and, therefore are likely to result in abscess formation. 13 Abscesses associated with retained gall stones require surgical removal for definitive cure. 12

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus. These ectopic glands are hormonally responsive and undergo repeated bleeding resulting in inflammation and fibrosis. Pelvis is the most common site for these ectopic glands. Extra-pelvic endometriosis is a relatively rare condition. 14 Morrison's pouch implants are commonly associated with diaphragmatic endometriosis. 15 Ultrasound and CT features are non-specific. MR imaging is the preferred modality for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Endometriotic implants have a high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images due to the presence of methemoglobin. 14

Space-Occupying Lesions

Local Extension of Malignant Tumors

Morrison's pouch can be involved by neoplastic pathologies due to the contiguous spread from adjacent organs via serosal invasion or noncontiguous spread via intraperitoneal seeding along the flow of ascitic fluid.

Hepatic malignancies involving the right lobe, renal malignancies, adrenal tumors, and bowel malignancies from the colon/duodenum can spread to Morrison's pouch along the visceral peritoneal surface ( Fig. 10 ). Sometimes, abdomino-pelvic masses can be large enough to extend directly into supramesocolic spaces ( Fig. 11 ).

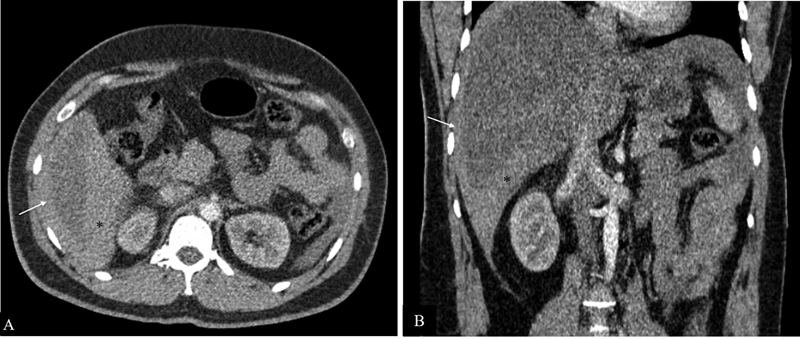

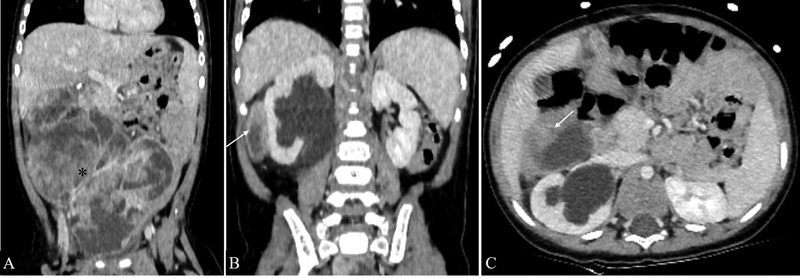

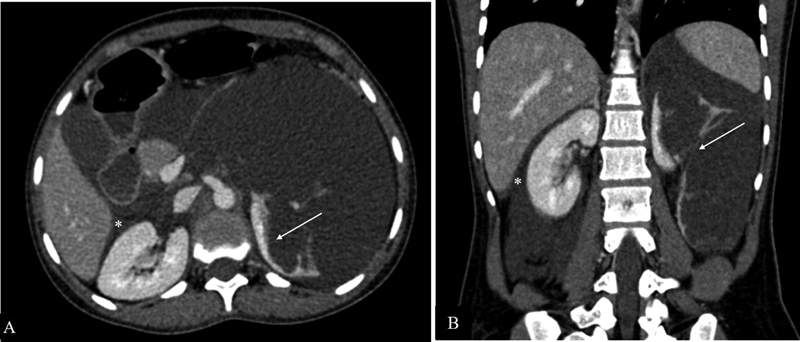

Fig. 10.

Renal cell carcinoma. Axial ( A ) and coronal ( B ) sections of nephrographic phase in a 55-year-old patient with incidentally detected right renal lesion on ultrasound showing a ball-type partially exophytic lesion (*) in the inferior pole of the right kidney with extension into the perinephric space (white arrow) and seen bulging into the hepatorenal pouch (black arrow).

Fig. 11.

Infantile fibrosarcoma in a 9-month-old male child. Coronal ( A and B ) and axial ( C ) sections of contrast-enhanced CT shows an ill-defined heterogeneously enhancing abdominopelvic soft tissue mass with large necrotic areas (*) extending into the hepatorenal pouch (arrows in B and C ).

Metastatic Deposits

Gastrointestinal and gynecological malignancies in their advanced stages reach the peritoneal surface and are disseminated throughout the peritoneal cavity. Gravity, gastrointestinal tract peristalsis, and diaphragm movement are responsible for the spread via the peritoneal fluid. 16 Morrison's pouch being the most dependent intraperitoneal space in the supramesocolic compartment is a common site of metastatic deposits ( Fig. 12 ). CT/MR features include irregular peritoneal thickening and enhancement, enhancing peritoneal nodules or masses. Ascites may or may not be present.

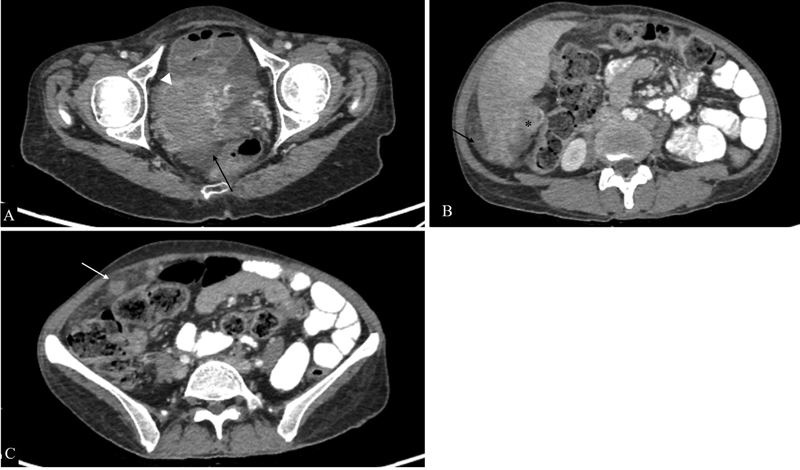

Fig. 12.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis from high-grade serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Axial sections of intravenous and oral contrast material-enhanced computed tomographic images showing the right adnexal mass (arrowhead in A ), soft-tissue deposits in hepatorenal pouch (* in B ), and omental nodularity (white arrow in C ) along with free fluid in pelvis (black arrows).

Metastatic Mature Teratomas

Metastatic mature teratomas are residual tumors that consist of mature teratomatous tissue elements at the sites of metastasis of malignant non-seminomatous germ cell tumors. They appear as partially cystic masses with enhancing septations. Fat and calcifications are also seen, which are more common in females ( Fig. 13 ). 17 Some of the proposed theories for this condition include “chemotherapeutic retro-conversion,” where there is induction of somatic maturation in malignant cells by chemotherapy and “selective destruction,” in which a chemotherapeutic agent destroys immature elements and mature elements that are resistant to chemotherapy are left behind. 18 When there is proliferation of these mature tissue elements during or after chemotherapy, in the setting of normal tumor markers, the condition is known as growing teratoma syndrome. Imaging features include an increase in the size and cystic component of metastatic mature teratoma. 17 In cases of ovarian germ cell tumors, the peritoneum has been described as the most commonly involved site in growing teratoma syndrome. 19

Fig. 13.

Metastatic mature teratoma. Axial ( A ) and coronal ( B ) contrast-enhanced CT sections of a 16-year old girl previously treated for immature teratoma showing a soft tissue deposit in Morrison's pouch (arrow) consisting of areas of fat and calcifications. Tumor markers were normal in this patient.

Lymphatic Malformations

Abdominal lymphatic malformations are rare benign vascular malformations, most commonly occurring in mesentery. Retroperitoneal lymphatic malformations are less common and renal lymphatic malformations are even rarer. Sonographically, their appearance varies from multilocular cystic lesions to almost solid-appearing lesions due to the presence of numerous internal septations creating multiple echogenic interfaces. CT shows insinuating mass with enhancing wall, internal septations and homogeneous low-attenuation fluid content ( Fig. 14 ). The MR appearance of internal contents resembles fluid. 20 However, the presence of proteinaceous contents or hemorrhage may result in a variable appearance. Mesenteric lesions may extend into Morrison's pouch due to their insinuating nature while retroperitoneal and perirenal lesions may bulge into hepatorenal space from perirenal space.

Fig. 14.

Lymphatic malformation. Contrast-enhanced axial ( A ) and coronal ( B ) computed tomographic images showing a large insinuating cystic lesion in the retroperitoneum causing distortion of the left renal parenchyma (white arrows in A and B ), crossing the midline to reach the contralateral perirenal space bulging into hepatorenal pouch (*).

Conclusion

Morrison's pouch is an important intraperitoneal space that may be involved in a wide variety of pathologies. Detailed knowledge of its anatomy, relationship with nearby organs, and mechanisms of spread of distant pathology are important for comprehensive diagnosis. Familiarity with the imaging spectrum of various conditions allows accurate diagnosis and aids in adequate patient management.

Acknowledgment

We sincerely thank Dr. Chandrashekhara S.H., Department of Radiodiagnosis, Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, for contributing two images.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Authors' Contributions

G.K. and M.B.B.S. contributed to the concept of the manuscript, wrote manuscript, contributed images and captions, final approval of the manuscript. T.K. and M.D. contributed to writing, preparing images and captions, final approval of the manuscript. C.J.D. and M.D. contributed to the concept of the manuscript, helped in writing of the manuscript, contributed images and captions, oversaw the process, final approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Le O. Patterns of peritoneal spread of tumor in the abdomen and pelvis. World J Radiol. 2013;5(03):106–112. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i3.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tirkes T, Sandrasegaran K, Patel A A. Peritoneal and retroperitoneal anatomy and its relevance for cross-sectional imaging. Radiographics. 2012;32(02):437–451. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyers M A. Distribution of intra-abdominal malignant seeding: dependency on dynamics of flow of ascitic fluid. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119(01):198–206. doi: 10.2214/ajr.119.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanbidge A E, Lynch D, Wilson S R.US of the peritoneum Radiographics 20032303663–684., discussion 684–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anthony M P, Khong P L, Zhang J. Spectrum of (18)F-FDG PET/CT appearances in peritoneal disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(06):W523-9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S, Kim T U, Lee J W. The perihepatic space: comprehensive anatomy and CT features of pathologic conditions. Radiographics. 2007;27(01):129–143. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira J M, Madureira A J, Vieira A, Ramos I. Abdominal tuberculosis: imaging features. Eur J Radiol. 2005;55(02):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubner M, Menias C, Rucker C. Blood in the belly: CT findings of hemoperitoneum. Radiographics. 2007;27(01):109–125. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawashima A, Sandler C M, Ernst R D. Imaging of nontraumatic hemorrhage of the adrenal gland. Radiographics. 1999;19(04):949–963. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.4.g99jl13949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrill J, Williams C J, Bain G, Conder G, Hine A L, Misra R R. Tuberculosis: a radiologic review. Radiographics. 2007;27(05):1255–1273. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith E A, Dillman J R, Elsayes K M, Menias C O, Bude R O. Cross-sectional imaging of acute and chronic gallbladder inflammatory disease. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(01):188–196. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nayak L, Menias C O, Gayer G.Dropped gallstones: spectrum of imaging findings, complications and diagnostic pitfalls Br J Radiol 201386(1028):2.0120588E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodfield J C, Rodgers M, Windsor J A. Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, complications, and management. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(08):1200–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamié L P, Ribeiro D MFR, Tiferes D A, Macedo Neto A C, Serafini P C. Atypical sites of deeply infiltrative endometriosis: clinical characteristics and imaging findings. Radiographics. 2018;38(01):309–328. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rousset P, Gregory J, Rousset-Jablonski C. MR diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(11):3968–3977. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusamura S, Baratti D, Zaffaroni N. Pathophysiology and biology of peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(01):12–18. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green D B, La Rosa F G, Craig P G, Khani F, Lam E T. Metastatic mature teratoma and growing teratoma syndrome in patients with testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumors. Korean J Radiol. 2021;22(10):1650–1657. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaaban A M, Rezvani M, Elsayes K M. Ovarian malignant germ cell tumors: cellular classification and clinical and imaging features. Radiographics. 2014;34(03):777–801. doi: 10.1148/rg.343130067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zagamé L, Pautier P, Duvillard P, Castaigne D, Patte C, Lhommé C.Growing teratoma syndrome after ovarian germ cell tumors Obstet Gynecol 2006108(3 Pt 1):509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy A D, Cantisani V, Miettinen M. Abdominal lymphangiomas: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(06):1485–1491. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.6.1821485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]