Abstract

Introduction

The study objective was to explore the impact of the complete virtual transition of in-hospital clinical training on students' academic performance and to assess students' perceptions of the overall experience.

Methods

In-hospital clinical training was delivered via distance learning using daily synchronous videoconferences for two successive weeks to 350 final-year pharmacy students. The Virtual Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University (VFOPCU) platform allowed trainees to virtually browse patient files interactively with their clinical instructors to simulate a typical rounding experience. Academic performance was evaluated through identical 20-question tests before and after training. Perceptions were assessed through an online survey.

Results

Response rates were 79% pretest and 64% posttest. The median score was significantly higher after receiving the virtual training (7/20 [6–9] out of 20 pretest vs. 18/20 [11−20] posttest, P < .001]. Training evaluations revealed high levels of satisfaction (average rating > 3.5/5). Around 27% of respondents were completely satisfied with the overall experience, providing no suggestions for improvement. However, inappropriate timing of the training (27.4%) and describing training as being condensed and tiring (16.2%) were the main disadvantages reported.

Conclusions

Implementing a distance learning method with the aid of the VFOPCU platform to deliver clinical experiences instead of physical presence in hospitals appeared to be feasible and helpful during the COVID-19 crisis. Consideration of student suggestions and better utilization of available resources will open the door for new and better ideas to deliver clinical skills virtually even after resolution of the pandemic.

Keywords: Virtual training, Platform, Student perception, Clinical pharmacy, Distance education, COVID-19

Introduction

In the past two years, COVID-19 has introduced substantial changes in the educational process. To slow the spreading of COVID-19 among the general population, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended drastic social distancing measures on 11 March 2020.1 , 2 Consequently, most educational institutions encountered a sudden shift to distance e-learning to deliver the same set of knowledge and skills they should have previously.3 , 4 These changes imposed many practical and logistic challenges, especially for final year students enrolled in different health-related educational institutions. In any health-related school, provision of problem-solving, clinical practice, and collaboration skills are educational aims. In most schools, this is achieved through exposure to many clinical cases in outpatient and inpatient settings. Unfortunately, in the presence of COVID-19, students could acquire and even transmit the virus unknowingly.1 Yet at the same time, there was an increasing demand for health services and providers.5

In Egypt, the Clinical Pharmacy program is one of the academic pharmacy programs offered by the Cairo University Faculty of Pharmacy. Clinical Pharmacy is a private, five-year program. Study in the program includes 175 credit hours in addition to six credit hours of university requirements, and the clinical curriculum is taught in the last two years of the program.6 According to the faculty's regulations, a two-week training period on clinical pharmacy services in hospitals is one of the mandatory requirements for graduation. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, this training was conducted during the summer vacation of the fourth academic year. The faculty used to offer training programs in accredited hospitals located within greater Cairo. The main aim of the training was to enhance students' clinical skills in reading patient files, identifying drug-related needs, checking recent guidelines and published papers, and designing a tailored pharmaceutical care plan. From 18 March 2020 to 17 October 2020, all face-to-face academic activities in Egypt had to be conducted virtually. During this period, all students remained at home with all assignments completed online except for final high school exams that were conducted on-site in June and July.7 , 8 These decisions interfered with the scheduled training time for pharmacy students. During summer 2020, conducting in-hospital training for pharmacy students at Cairo University was inapplicable due to hesitancy of the students and their parents on one side, and the hospitals' refusals or inabilities to provide any unnecessary services during the peak of the pandemic on the other side. Subsequently, as an alternative strategy to cope with government efforts to implement effective social distancing, the program administration in collaboration with the Clinical Pharmacy department redesigned and implemented a new model to deliver the clinical training online through a specially designed virtual training (VT) program.

In pharmacy education, distant education (DE) modalities were adopted before the COVID-19 crisis. DE programs were created to provide better access to clinical resources to pharmacists from different geographical locations and to increase class size.9 These programs were mainly targeted to postgraduate students such as doctor of pharmacy enrollees utilizing both synchronous and asynchronous learning.10 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the application of DE concepts extended to involve undergraduate and graduate pharmacy students.11 , 12 This transition to remote teaching in pharmacy education is becoming an inevitable need, especially with the fading of geographical barriers. The emergence of COVID-19 just helped in accelerating this need. According to the Asia-Pacific region's experience, the achievement of successful DE in pharmaceutical sciences requires continuous methodical working in designing and planning innovative teaching models, then evaluating each model to identify the present challenges and flaws in order to reach a nearly perfect approach for DE.11

Various experiences have been published regarding health-related educational institutions' DE strategies in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Despite varied level of satisfaction, most published studies agreed that distance e-learning can replace, to a large extent, the traditional method in delivering theoretical learning, but not clinical skills.13, 14, 15 Moreover, studies involving virtual learning strategies for clinical skills in health-related institutions are either scarce or not promising.12 , 14 , 15 Moreover, no published studies are available that address the success and students' perceptions about the complete shift of clinical training to DE among pharmacy students. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the situation of complete virtual clinical training and to identify satisfaction with, perception or, and impact of specially designed VT instead of physical presence in hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak on the intellectual, professional, and clinical skills of fifth-year clinical pharmacy students.

Methods

Platform design and development

A specially designed, new electronic platform was developed by the researchers, known as the Virtual Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University (VFOPCU) platform. VFOPCU is a web-based electronic platform specially designed using Hyper Text Markup Language-5 (HTML5), Cascading Style Sheets-3 (CSS3), and JavaScript. The platform allows trainees to virtually browse patient files interactively with their clinical instructors to explore all clinical information, including diagnosis, laboratory results, progressing notes, and medications, as if they were rounding in the hospital. In addition, the platform is equipped with all the sources and lectures required to develop and support trainees' knowledge and skills during clinical training. All the presented files were real cases transcribed from patients medical records specially designed for this purpose in a manner that protected the confidentiality of the patients and the hospitals. All files were hand-written to simulate the real files available in hospitals, so the students were exposed as close as possible to the real documents (see eFigure 1 for examples).

Study design and setting

The study was an observational, prospective, mixed-methods approach involving fifth-year pharmacy students (N = 350) at Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, Egypt. The study received exempt status from the Research Ethics Committee for Experimental and Clinical Studies, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University. The study evaluated the training program conducted during the end of summer break of the academic year 2019–2020 through winter break of the academic year 2020–2021. The training program progressed as follows.

(1) Evaluating the students baseline knowledge and clinical skills. A pretest was developed to assess the knowledge and clinical skills of undergraduate pharmacy students on designing and monitoring an appropriate pharmacotherapeutic plan (eFigure 2). The test was available online through Google Forms (Alphabet, Inc.), and the link was sent to all the students at the same time via their university email. Students were requested to answer the questions using their own knowledge without the help of any scientific sources (electronic or paper-based). Also, students were assured that taking the test was totally voluntary with no obligation. Responses were collected through the first day of VT.

(2) Conducting the two-week virtual training program. Students were divided into small groups of nine to 10 students maximum. For each group, the VT was conducted over a two-week period. There were multiple groups running over the same two-weeks. This cycle was repeated three times through an entire semester. The VT focused on the role of clinical pharmacists in formulating an appropriate pharmacotherapeutic regimen medical specialties such as critical care, oncology, hepatology, nephrology, infectious, and cardiovascular disease. Ten highly qualified and specialized clinical pharmacy practitioners from nine different hospitals were selected and contracted through Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University to act as the students' online preceptors. The training included a daily (five days/week) interactive synchronous online session of four hours' duration. Each daily session was handled by a different instructor (each student encountered the 10 instructors through 10 different sessions). The VT's aim, mission, and vision are available in eFigure 1.

Webex, version 42.4.4 (Cisco Systems, Inc.) was the main videoconferencing application used during VT. The instructors were able to switch between screens to display either a slide presentation, video, images, or the virtual patient files on the platform. Moreover, the instructors presented each patient's data in a stepwise manner to give students time to check recent guidelines and design a tailored pharmaceutical plan for every single case. Providing day to day patient progression allowed students to also react in real time to new clinical information presented, as would be done during an in-person clinical learning experience. The students were allowed to use computers and/or smartphones to access the training platform. In addition, they were asked to turn on their camera and were able to interact with both the instructor and with each other either verbally by using the microphone or through the chat features. An administrator from the faculty's information technology center was devoted to follow and report the trainees' absenteeism and to provide any needed technical support.

Flipped classroom and active exercises were applied to enhance problem-solving and critical-thinking skills to support learning in the virtual environment. The four hour sessions were designed to start with a five min quiz related to the topic of the day followed by around one hour of interactive lecture about the proposed topic covering pathophysiology, main symptoms, common diagnostic and laboratory data, treatment, and recent guidelines. The remaining three hours included interactive training on three to four clinical cases involving reviewing virtual patients' files, identifying their problem list, and designing an appropriate pharmaceutical plan. The sessions ended daily with the same five min quiz. All quizzes were graded automatically, and the grades were sent directly to the students through their university emails with another copy to the training program coordinator. These quizzes were included by the clinical program coordinator as one of the requirements to pass the training, but they were not for research purposes and thus were not included in the data analysis.

(3) Evaluating students' knowledge and clinical skills after finishing training program. The same test was offered to all students after finishing the VT to assess the impact of the training program on academic performance. Each trainee's official faculty email was required at the beginning of the online tests to allow for linking pretest and postest responses and to exclude duplicates. The pre- and posttests were identical and were composed of 20 closed-questions covering all topics taught. The question types included true and false, simple multiple choice questions (MCQs), and short case-based MCQs.

(4) Evaluating students' perceptions of training. Trainees were asked to complete an online survey to identify their perceptions about the overall experience, areas for improvement, and opinion about the instructors. The online survey was composed of 28 close-ended questions and one open-ended question. The complete online survey is available in eFigure 3. The close-ended questions included five-level Likert-type questions. The survey was composed of the following domains: (1) ease of handling and integrity of the specially-designed platform (5 questions), (2) design and layout of the platform (7 questions), (3) usefulness and acceptability of the scientific content uploaded on the platform (5 questions), and (4) professionalism of the instructors and the appropriateness of the overall training program (11 questions). At the end of the survey, trainees were asked to freely express their thoughts about the training, to report any barriers they encountered during the VT, and to provide any advice for improvement. The link for the survey was sent to trainees by email and was available in an online Microsoft Form (Microsoft Corp.). As with the online tests, official faculty email addresses were required at the beginning of the survey exclude duplicates. Since English was the main language used in teaching the scientific material, the survey and pre- and posttests were developed in English.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 25 (IBM Corp.). The parameters related to the pre- and posttests and the online survey were subjected to descriptive statistics by calculating percentage, frequency, mean, and standard deviation. The Shapiro-Wilks test was applied to check if continuous variables followed normal distribution. Total correct scores of the pre- and posttests were not normally distributed, and thus were compared before and after receiving the VT using the Wilcoxon signed rank sum test. For survey results, each level of the Likert scale was denoted by a number (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree), and the average (SD) level of satisfaction was determined. The chi-square test was applied to determine if there was a significant difference in the responses to particular statements in the survey. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

Of the 350 students who attended the VT, 278 (79.4%) students responded to the pretest and 224 (64%) to the posttest. The median correct score was 7 (6–9) out of 20 for the pretest and 18 (11−20) out of 20 for the posttest. When the questions were grouped based on the medical specialty, it was found that the frequency of total correct responses in the pretest were < 35% in all specialties except for critical care (50%). On the contrary, in the posttest, the frequency of total correct responses was >75% in all specialties (Fig. 1 ). After filtering responses based on the student's email, 172 (49.1%) students completed both the pre- and posttests. Comparing the total correct score of these students before and after receiving the VT revealed a statistically significant improvement in knowledge (P < .001).

Fig. 1.

Correct responses of final-year pharmacy students before and after virtual training (n = 172).

The online survey took about 8 min to complete. The response rate was 56.3% (n = 207). Table 1 shows satisfaction with the handling and design of the VFOPCU platform. The majority (n = 137, 69.5%) found the platform easy to use, and less than a quarter (n = 40, 20.3%) needed technical support to be able to use the platform. More than half of the students (n = 119, 60.4%) wanted to use the platform regularly. A majority of the respondents (n = 150, 76.1%) liked the overall look of the platform and declared the platform's design was appropriate for its purpose (n = 149, 75.6%).

Table 1.

Summary of satisfaction with the handling and layout of the VFOPCU platform (n = 197).

| Parameter | Strongly disagree, n (%) | Disagree, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Agree, n (%) | Strongly agree, n (%) | Mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think that I would like to use this platform frequently | 25 (12.7) | 9 (4.6) | 44 (22.3) | 67 (34) | 52 (26.4) | 3.57 (1.28) | < .001 |

| I thought the platform was easy to use | 20 (10.2) | 7 (3.6) | 26 (13.2) | 81(41.1) | 63 (32) | 3.81 (1.22) | < .001 |

| I think that I would not need the support of a technical person to be able to use this platform | 23 (11.7) | 17 (8.6) | 31 (15.7) | 71 (36) | 55 (27.9) | 3.60 (1.30) | < .001 |

| I found the various functions on this platform were well integrated | 18 (9.1) | 8 (4.1) | 38 (19.3) | 82 (41.6) | 51 (25.9) | 3.71 (1.17) | < .001 |

| I would imagine that most students would learn to use this platform very quickly | 16 (8.1) | 7 (3.6) | 37 (18.8) | 80 (40.6) | 57 (28.9) | 3.79 (1.15) | < .001 |

| The use of colors in the platform | 5 (2.5) | 11 (5.6) | 56 (28.4) | 70 (35.5) | 55 (27.9) | 3.81 (0.99) | < .001 |

| The fonts used in the platform | 0 (0) | 11 (5.6) | 61 (31) | 72 (36.5) | 53 (26.9) | 3.85 (0.88) | < .001 |

| The layout of the platform | 4 (2) | 9 (4.6) | 48 (24.4) | 70 (35.5) | 66 (33.5) | 3.94 (0.97) | < .001 |

| How professional did you feel the platform was to look at | 1 (0.5) | 11 (5.6) | 37 (18.8) | 75 (38.1) | 73 (37.1) | 4.06 (0.91) | < .001 |

| To what extent do you feel the design suited the purpose of the platform | 0 (0) | 8 (4.1) | 40 (20.3) | 83 (42.1) | 66 (33.5) | 4.05 (0.84) | < .001 |

| The look of the platform overall | 4 (2) | 8 (4.1) | 35 (17.8) | 85 (43.1) | 65 (33) | 4.01 (0.93) | < .001 |

| The design of the platform | 3 (1.5) | 9 (4.6) | 37 (18.8) | 76 (38.6) | 72 (36.5) | 4.04 (0.94) | < .001 |

VFOPCU = Virtual Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University.

As shown in Table 2 , the “virtual patient files” section was useful for a large number of students (n = 143, 72.5%), where most of the respondents (n = 130, 66%) described the scientific content on the platform as “supportive to them” to develop their patient assessment knowledge and skill. Slightly more than half of the respondents (n = 113, 57.4%) found the platform's content useful to simulating real training in health care facilities, while “not useful” and “not useful at all” were expressed by 22 (11.2%) and 13 (6.6%) respondents, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of evaluation of the scientific content uploaded on the VFOPCU platform (n = 197).

| Parameter | Not useful at all, n (%) | Not useful, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Useful, n (%) | Very useful, n (%) | Mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How detailed did you find the content of the platform | 5 (2.5) | 12 (6.1) | 50 (25.4) | 71 (36) | 59 (29.9) | 3.85 (1.00) | < .001 |

| How useful did you find the “Virtual Patient Files” section | 6 (3) | 8 (4.1) | 40 (20.3) | 65 (33) | 78 (39.6) | 4.02 (1.02) | < .001 |

| How useful did you find the “Surveys” the platform generated | 5 (2.5) | 16 (8.1) | 50 (25.4) | 73 (37.1) | 53 (26.9) | 3.78 (1.02) | < .001 |

| How sufficient did you feel the content of the platform was in supporting you to develop your patient assessment Knowledge and skills | 13 (6.6) | 22 (11.2) | 49 (24.9) | 67 (34) | 46 (23.4) | 3.84 (1.02) | < .001 |

| How sufficient did you feel the content of the virtual training platform was in simulating the real training in health care facilities | 4 (2) | 17 (8.6) | 46 (23.4) | 70 (35.5) | 60 (30.5) | 3.56 (1.16) | < .001 |

VFOPCU = Virtual Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University.

Table 3 shows the respondents' satisfaction for the overall training program. More than half (n = 121, 61.4%) found that the training program was well managed. The vast majority agreed or strongly agreed that instructors discussed several live cases and situations (n = 167, 84.8%) and encouraged participants to ask questions (n = 173, 87.8%). However, only 82 (41.6%) respondents were satisfied with the length of the training. Overall, it was found that the respondents were satisfied with the different aspects of the VT, as for each item the average rating was >3.5, which is generally considered as good.

Table 3.

Summary of satisfaction with the instructors and the appropriateness of the overall training program (n = 197).

| Parameter | Strongly disagree, n (%) | Disagree, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Agree, n (%) | Strongly agree, n (%) | Mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall the training program was of great interest to all trainees. | 13 (6.6) | 14 (7.1) | 49 (24.9) | 77 (39.1) | 44 (22.3) | 3.63 (1.11) | < .001 |

| The Program was well managed and venue was comfortable | 14 (7.1) | 22 (11.2) | 40 (20.3) | 80 (40.6) | 41 (20.8) | 3.57 (1.15) | < .001 |

| The instructors presented the materials satisfactorily and it was easy to understand | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 49 (24.9) | 98 (49.7) | 42 (21.3) | 3.86 (0.84) | < .001 |

| The instructors encouraged participants to ask questions | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 20 (10.2) | 96 (48.7) | 77 (39.1) | 4.23 (0.79) | < .001 |

| Several relevant cases/examples/live situations were discussed | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 22 (11.2) | 104 (52.8) | 63 (32) | 4.11 (0.83) | < .001 |

| This training was helpful in upgrading my skills | 6 (3) | 13 (6.6) | 41 (20.8) | 78 (39.6) | 59 (29.9) | 3.87 (1.02) | < .001 |

| The training programs help in bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical pharmacy practice | 8 (4.1) | 13 (6.6) | 37 (18.8) | 81 (41.1) | 58 (29.4) | 3.85 (1.05) | < .001 |

| The training contributes to a large extent in improving the confidence and commitment of the students | 6 (3) | 16 (8.1) | 49 (24.9) | 74 (37.6) | 52 (26.4) | 3.76 (1.03) | < .001 |

| The length of the training was appropriate. | 27 (13.7) | 37 (18.8) | 51 (25.9) | 52 (26.4) | 30 (15.2) | 3.11 (1.27) | .008 |

| The pace of the training program was appropriate | 25 (12.7) | 25 (12.7) | 51 (25.9) | 67 (34) | 29 (14.7) | 3.25 (1.23) | < .001 |

| The training content was relevant to the objectives | 6 (3) | 7 (3.6) | 36 (18.3) | 97 (49.2) | 51 (25.9) | 3.91 (0.93) | < .001 |

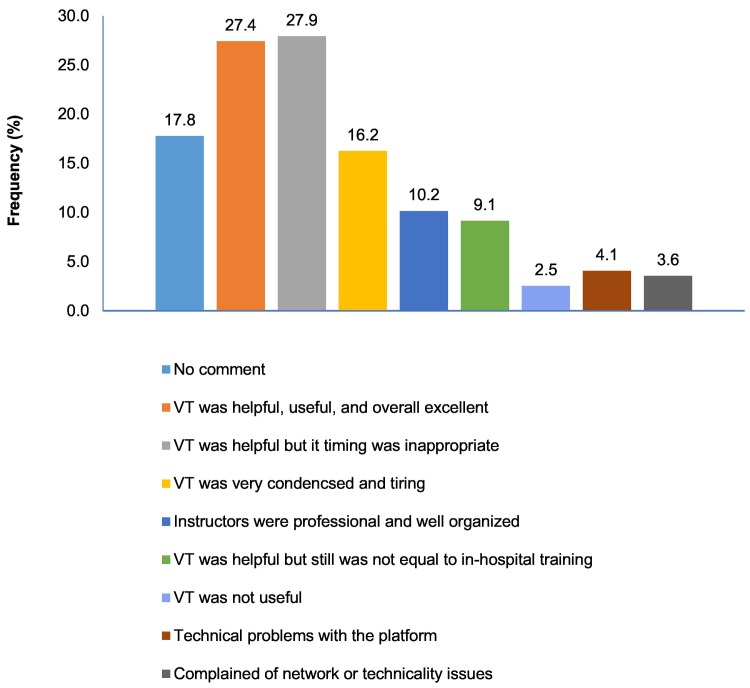

Many respondents (n = 162, 82.2%) left a comment when asked to express their thoughts about the training (Fig. 2 ), and 54 (27.4%) respondents indicated they were completely satisfied with the overall experience without providing any suggestions for improvement. Of these 54 respondents, 3 (5.6%) described the VT as a “creative solution during the COVID situation.” Fifty-five (27.9%) respondents stated that the VT was well organized and useful except for the timing of the training. They suggested that it would have been better if the training was conducted in the summer or mid-year vacation rather than in the middle of the semester, since it was very inconvenient for them to balance the VT and the day-time lectures and exams. The VT was described as condensed and tiring by 32 (16.2%) respondents, finding it exhausting to focus on computer screen for four hours during two successive weeks; they noted they would rather prefer to extend the training over a one-month period with more off-days between the sessions. Eighteen (9.1%) respondents agreed that although the VT was well organized and helpful, this was still not enough to simulate real training in hospitals. Twenty (10.2%) respondents cared to thank all instructors for their professionalism and patience while delivering the scientific information and clinical practice. However, 8 (4.1%) respondents commented that a few instructors did not provide much time for interaction and discussion. Eight (4.1%) respondents complained of technical problems with the platform, with 5 (62.5%) finding that it was a bit hard or slow to search for an information; 3 (37.5%) suggested providing an offline downloadable version of the platform to overcome network issues. Only 5 (2.5%) respondents described the VT as “not useful at all.”

Fig. 2.

Most frequent comments received from final-year pharmacy students when asked to freely express their thoughts about the training (n = 197).

VT = virtual training.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate final-year pharmacy students' experiences with the complete delivery of clinical skills via virtual (i.e. remote) modalities. The rapid rise of COVID-19 cases has led to a sudden shift of education from traditional face-to-face learning to distance e-learning. These changes have significantly impacted theoretical and clinical skills learning as well as training environments in the health-related educational institutions.16 Therefore, innovative solutions with the use of technology and new models of education were mandatory to maintain education sustainability during the COVID-19 outbreak.11 , 16 In this context, the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University was always interested in adopting new and innovative ideas for students learning and evaluation.17

The VT differed from the traditional in-hospital training in the following aspects. (1) Before COVID-19, students were distributed over different hospitals, so that each student had to attend the two-week training in a single hospital. The choice of the hospital depended on the student's preference and internal coordination based on their grade point average. Given that not all hospitals include all medical specialties (some are dedicated to oncological diseases, others to intensive care, etc.), the whole training focused on certain clinical pharmacy branches while totally missing others. However, in the VT, the students had the chance to attend all different specialties. This indicates the VT's ability to achieve the main goals of DE in pharmacy education, such as increasing access to different medical institutions, increasing class size, saving time, and eliminating geographical boundaries.10 (2) During traditional in-hospital training, the activities of each day were divided. First, the students attended one to two hours of lecture about the proposed topic presented by a clinical pharmacist practitioner in the hospital. Then every student was assigned different patient cases among those admitted to the hospital during the training. During the clinical rotation, students had to gather enough information to identify each patient's drug-related needs. Then, they had time to do their search and prepare their care plan. Finally, each student presented his/her suggested care plan and recommendations in a group discussion in the presence of the instructor. At the end of the day, the students were also assigned assignments and homework to be discussed the next day at the hospital. Within the VT, new teaching methods, such as flipped classroom, were applied besides the traditional activities. (3) Students' assessment during traditional in-hospital training was based on instructors' evaluations, students' attendance, and their commitments to deadlines. However, thanks to the use of technology and the platform during the VT, more student assessment tools were applied such as the quizzes, pretest, and posttest. Also, the implementation of technology enabled the electronic grading of the assignments, which saved time for the instructors and provided a more flawless and objective grading system. (4) The length of time dedicated to every activity in the VT was shorter than usual to fit the time restrictions imposed by synchronous online sessions. The maximum duration of any online session should not exceed 90 min and should include multiple pauses and breaks to help students recover their attentional resources.18

The results from the pre- and posttests indicated that VT had a positive impact on academic performance, knowledge, and clinical skills. The evaluation of the posttest's correct answers did not appear to show significant differences between different medical specialties. This may indicate that instructor performance, applied active exercises, and material delivery were nearly equivalent among the different sessions. Similar to the current study's finding, Darr et al19 reported that virtual learning provided similar experiences as the traditional live classroom in delivering a laboratory course to pharmacy students as the virtual setting did not hinder students' performance based on there being no statistical difference between grades on several assessments across two learning modalities. Given the document-based nature of patient files, guidelines, and medications reviews included in both the current and Darr et al19 studies, this might have helped in the success of the virtual shifting of the clinical training and the laboratory course, respectively. However, it will likely be more difficult and challenging for laboratory courses emphasizing manual skills, such as physical examination or substance analysis using certain dangerous chemicals, to be replicated at home. For these reasons, several studies reported that distance e-learning was challenging and unsuccessful in delivering practical medical skills compared to theoretical learning,14 , 15 while clinical training was deferred in others.1 , 20

Regarding students' perceptions, the results showed positive feedback about the platform, instructors, and the scientific content. Instructors' competence (mean 4.23), live case discussions (mean 3), and the design of the platform (mean 4.06) achieved the highest satisfaction levels among the students. The authors believe that instructors played an important role in the success of this experience, since they were responsible for many aspects of the VT. Firstly, they prepared all the scientific materials and clinical cases uploaded on the platform. Secondly, they were responsible of running the online session in interactive way, either during the one-hour lecture or during the practical application on problem-solving and clinical skills. This was achieved by giving the students enough time to think and look for the required information, to ask questions, and by encouraging every student to participate in every activity and discussion.

Unlike a Jordanian experience that evaluated the utilization of DE in medical education,15 the VT achieved fairly good satisfaction by respondents. This may be attributed to the fact that this study was able to overcome many challenges against effective DE reported in previous studies.12 , 15 , 21 Firstly, before the VT, all students gained some experience with the many components related to different DE platforms (such as Google Classrooms and Blackboard) and e-learning methods. Since the curfew in March 2020, about half of the theoretical and practical curricula were taught through interactive videoconferencing, as requested by authorities.7 Secondly, besides their expertise in their medical specialty, the instructors received the necessary training to provide medical content compatible with online delivery and to provide highly interactive environments for the students. Finally, < 10% of the respondents complained of either technical, connectivity, or network issues. This might favor the overall experience, given that connectivity issues and weak infrastructural techniques were the most commonly reported challenges to DE in previous studies.12 , 15 , 22 This might explain the positive views of the respondents on many items related to the platform use and VT.

In line with the survey results, most of the respondent's comments on the overall VT, VFOPCU platform, and the instructors were positive. The most reported complaint was the timing of the training (27.9%). Due to logistics and technical issues, the VT had to be conducted for some students in the middle of the final-year's semester instead of being conducted in the summer or winter break. This might have put some students under more stress than others, and consequently may have impacted their educational attainment and satisfaction. In addition, four-hour online sessions for two successive weeks together with daily assignments and day-time lectures and labs were exhausting for some students. One of the signs of the VT success is that only 9% of the respondents found the VT not equivalent to the in-hospital training, although they found it helpful. Unfortunately, those students did not mention the reason, except two who suggested to include some technologies for patient simulation and interviewing.

The following areas of development could be concluded from this experience: (1) re-scheduling the training over a longer period with aim of shortening the online-sessions duration to be less than four hours per day, (2) incorporation of some technologies for patient interviewing, (3) provision of an offline access to the scientific content uploaded on the platform, and (4) designing a smarter search engine to extract the desired information from the platform in an easier or faster way.

Unlike previously published studies that were interested in either assessing the situation of DE in delivering theoretical learning or the hybrid integration of both face-to-face and virtual learning to deliver clinical skills,12 , 15 , 20 the current study showed that VT with the aid of the VFOPCU platform was successful to deliver remote clinical, but not laboratory, skills for pharmacy students. Given the growing interest among educators in the electronic learning in medical fields,23 the authors believe that these findings will encourage many universities to adopt VT techniques for pharmacy education.

In addition to the inappropriate timing of the training previously mentioned, other limitations in the study have been identified. A sampling bias may have occurred since only 56.3% of the students completed the online survey. The students were requested to take the survey by their free will without any obligations, and usually diligent students are the one who care to respond which may have positively affected the results. Another limitation of the study is the absence of comparable data coming from students who experienced the traditional in-hospital training. This was not feasible due to the sudden transition of universities activities to DE.

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 crisis, our VT was a successful modality in delivering clinical skills to the final-year pharmacy students. Although VT lacked some features of the traditional in-hospital experience, such as patient simulation and interviewing, it offered a better solution than postponing all clinical training until after the recession of the pandemic, which would have delayed student's graduation. The design of the platform, instructors' performance and interaction, and lack of major connectivity issues were the main reasons for the success of the current experience. These findings may open the door for more ideas based on students' suggestions and reported comments with the aim of adopting DE methodologies to deliver clinical training to pharmacy students, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Although the VT was developed due to COVID-19, the concepts of this VT could be applied even after resolution of the pandemic, especially for postgraduate education, to eliminate geographical barriers and to provide greater access of pharmacy learning to place restrained students. But for undergraduate education, the authors suggest a blended approach to the clinical training, utilizing both the DE and face-to-face in-hospital training, where the use of the platform could help in the implementation of flipped classrooms, students' assessment, and assignment submission and grading. Online sessions can also assure students are exposed to all different specialties, something that cannot be guaranteed in traditional in-hospital training due to cost and time restrictions. Face-to-face in-hospital training may then be saved for practical applications where students will be distributed over different hospitals. This blended approach could increase class size, save instructor time, reduce training costs, and increase achievement of student learning outcomes.

Disclosure(s)

None.

Statement of authorship

Sandra Naguib conducted all statistical analysis, and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. Watheq AlSetohy designed the VFOPCU platform, and prepared the data collection tools. Nirmeen Sabry designed the methodology, supervised the findings of the work, and revised the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the instructors for their outstanding effort: Ahmed Elnady, Emam Mahmoud. Hend Ibrahim, Moaz Masoud, Nada Abd El-Rahman, Nader Shawky, Rana Salah, Yara Mohsen, and Yasmin Kamel. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the information technology members who provided all needed technical supports. Finally, the authors thank the respondents that took part in the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2023.02.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

eFig. 1. Example materials from the Virtual Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University platform.

eFig. 2. Virtual training pre- and posttest.

eFig. 3. Virtual training satisfaction survey.

References

- 1.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrel M.N., Ryan J.J. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 2020;12(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marinoni G., Van’t Land H., Jensen T. May 2020. The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world.https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf IAU Global Survey Report International Association of Universities. Accessed 23 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binks A.P., LeClair R.J., Willey J.M., et al. Changing medical education, overnight: the curricular response to COVID-19 of nine medical schools. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(3):334–342. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1891543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fessell D., Cherniss C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and beyond: micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(6):746–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical Pharmacy Program. Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University; 2023. https://www.pharma.cu.edu.eg/English/ClinicalPharmacyProgram/WhyThisProg.aspx Accessed 23 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egypt Closes Schools and Universities for Two Weeks over Coronavirus Concerns. 14 March 2020. https://english.ahram.org.eg/News/365268.aspx Ahram Online. Accessed 23 February 2023.

- 8.Egypt Pushes New School Year Back to 17 October, No Decision Yet on In-Classroom Learning: Ministry. 16 July 2020. https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/374675/Egypt/Politics-/Egypt-pushes-new-school-year-back-to--October,-no-.aspx Ahram Online. Accessed 23 February 2023.

- 9.Harrison L.C., Congdon H.B., DiPiro J.T. The status of US multi-campus colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):124. doi: 10.5688/aj7407124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motycka C.A., St Onge E.L., Williams J. Asynchronous versus synchronous learning in pharmacy education. J Curric Teach. 2013;2(1):63–67. doi: 10.5430/jct.v2n1p63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons K.M., Christopoulos A., Brock T.P. Sustainable pharmacy education in the time of COVID-19. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(6):8088. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altwaijry N., Ibrahim A., Binsuwaidan R., Alnajjar L.I., Alsfouk B.A., Almutairi R. Distance education during COVID-19 pandemic: a college of pharmacy experience. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:2099–2110. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S308998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajab M.H., Gazal A.M., Alkattan K. Challenges to online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos-Morcillo A.J., Leal-Costa C., Moral-García J.E., Ruzafa-Martínez M. Experiences of nursing students during the abrupt change from face-to-face to e-learning education during the first month of confinement due to COVID-19 in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5519. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Balas M., Al-Balas H.I., Jaber H.M., et al. Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur A., Soklaridis S., Crawford A., Mulsant B., Sockalingam S. Using rapid design thinking to overcome COVID-19 challenges in medical education. Acad Med. 2021;96(1):56–61. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabry N.A., Kamel A., Farid S.A. Designing and using an online survey as a tool for teaching pharmacy students about COVID-19: innovation in experiential learning or assessment. Pharm Educ. 2020;20(2):19–20. doi: 10.46542/pe.2020.202.1920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gegenfurtner A., Zitt A., Ebner C. Evaluating webinar-based training: a mixed methods study of trainee reactions toward digital web conferencing. Int J Train Dev. 2020;24(1):5–21. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darr A.Y., Kyner M., Fletcher R., Yoder A. Comparison of pharmacy students’ performance in a laboratory course delivered live versus by virtual facilitation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(2):8072. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qandil A.M., Abdel-Halim H. Distance e-learning is closer than everybody thought: a pharmacy education perspective. Health Profess Educ. 2020;6(3):301–303. doi: 10.1016/j.hpe.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubey P., Pandey D. Distance learning in higher education during pandemic: challenges and opportunities. Int J Indian Psychol. 2020;8(2):43–46. doi: 10.25215/0802.204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussain F.N., Al-Mannai R., Agouni A. An emergency switch to distance learning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: experience from an internationally accredited undergraduate pharmacy program at Qatar University. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1393–1397. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweileh W.M. Global research activity on e-learning in health sciences education: a bibliometric analysis. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(2):765–775. doi: 10.1007/S40670-021-01254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFig. 1. Example materials from the Virtual Faculty of Pharmacy Cairo University platform.

eFig. 2. Virtual training pre- and posttest.

eFig. 3. Virtual training satisfaction survey.