Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted mental health, health-related behaviours such as drinking and illicit drug use and the accessibility of health and social care services. How these pandemic shocks affected ‘despair’-related mortality in different countries is less clear. This study uses public data to compare deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide in the United States and the United Kingdom to identify similarities or differences in the impact of the pandemic on important non-COVID causes of death across countries and to consider the public health implications of these trends.

Study design and methods

Data were taken from publicly available mortality figures for England and Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland and the United States of America, 2001–2021, and analysed descriptively through age-standardised and age-specific mortality rates from suicide, alcohol and drug use.

Results

Alcohol-specific deaths increased in all countries between 2019 and 2021, most notably in the United States and, to a lesser extent, England and Wales. Suicide rates did not increase markedly during the pandemic in any of the included nations. Drug-related mortality rates rose dramatically over the same period in the United States but not in other nations.

Conclusions

Mortality from ‘deaths of despair’ during the pandemic has displayed divergent trends between causes and countries. Concerns about increases in deaths by suicide appear to have been unfounded, whereas deaths due to alcohol have risen across the United Kingdom and in the United States and across almost all age groups. Scotland and the United States had similarly high levels of drug-related deaths pre-pandemic, but the differing trends during the pandemic highlight the different underlying causes of these drug death epidemics and the importance of tailoring policy responses to these specific contexts.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health, Alcohol, Drugs, Suicide, Mortality

Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic dramatically changed daily life for most people in high-income countries. The early months of the pandemic saw the closure of schools, bars and restaurants and severe restrictions on social interactions. The resulting social isolation raised concerns about potential increases in depression and suicide.1 Similar concerns were voiced about increases in heavy drinking and substance misuse to cope with stress of the pandemic. Subsequent data showed significant deteriorations in mental health during the pandemic, particularly among women, young people and those on low incomes.2 Before the pandemic, increasing levels of mortality from alcohol, drugs and suicide – so-called ‘deaths of despair’ – had been well documented in the United States.3 Some have identified this as a uniquely American phenomenon;4 however, disaggregating the constituent nations of the United Kingdom highlights some dramatic trends. In recent years, Scotland has seen drug-related deaths and male suicide rates rise on a par with increases seen in the United States, whereas alcohol-related deaths have fallen. At the same time, deaths attributable to alcohol have risen consistently in England and Northern Ireland.5

While tax data suggested that there was no notable change in overall alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom during the first 2 years of pandemic,6 individual-level surveys showed an increase in heavier drinking, suggesting greater polarisation of drinking behaviour in England,7 , 8 although not necessarily in Scotland.9 Survey data in the United States showed more drinking days per month and heavier drinking, particularly for women.10 The pandemic also led to significant changes in accessibility of services, including mental health care and specialist alcohol and drug treatment services, that have benefitted some groups, but restricted access to others.11 , 12

Whether the dire predictions around increased mortality from alcohol, drugs and suicide – so-called ‘deaths of despair’ played out during the pandemic is not clear. Some studies suggest little impact on suicide rates,13 but notable increases in alcohol deaths in the United Kingdom14 in 2020 as well as substantial increases in alcohol and drug-related mortality in the United States.15 , 16 We use publicly available mortality data from 2001 to 2021 to compare mortality rates from these three causes across nations to better understand the wider impacts of the pandemic on public health.

Methods

We used mortality data for England and Wales from the ‘21st Century Mortality File’ published by the Office for National Statistics,17 for Northern Ireland from the Annual Reports of the Registrar General published by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency,18 for Scotland from the Vital Events Reference Tables published by National Records of Scotland19 and for the United States from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's WONDER Underlying Cause of Death data (for 2001–2020) and Multiple Cause of Death data (provisional) (for 2021).20 Data were available by International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code, sex and in 5-year age bands for all countries. Deaths were categorised based on the underlying cause of death as being attributable to alcohol, drugs or suicide in non-overlapping categories on the basis of standard ICD-10 code definitions (see supplementary table S1 for the list of included ICD-10 codes).5 , 21 Age-standardised mortality rates per 100,000 population for each cause from 2000 to 2021 were calculated using the European Standard Population22 and population estimates from the Human Mortality Database.23

Results

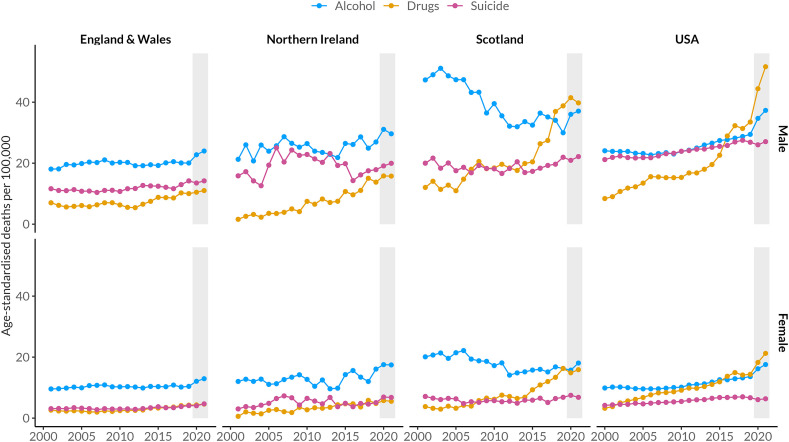

Age-standardised mortality rates for each cause, by sex and country, are illustrated in Fig. 1 and summarised in Table 1 . In all countries, suicide rates did not change much during the pandemic period. In the United States, the rates for both men and women dipped slightly below the pre-pandemic trend, while there was a small increase for both men and women in Northern Ireland. Suicide rates in England and Wales and Scotland were essentially stable. Changes in alcohol-specific deaths during the pandemic were more noticeable. Mortality increased for both men and women in England and Wales and the United States. In England and Wales, women saw an increase from 10.4 to 12.9 per 100,000 in alcohol-specific deaths from 2019 to 2021, a relative increase of 24.1%, compared with an increase of 19.6% in men. The United States saw even greater increases in alcohol-specific deaths of 29.1% in women and 26.7% in men, and the rates rose to a lesser extent for both men and women in Northern Ireland. Deaths from alcohol increased among Scottish men (23.7% relative increase) after a consistently declining pre-pandemic trend. The picture for drug-related deaths was more mixed, with a continuation of the gradually rising pre-pandemic trend in England and Wales and Northern Ireland. Both Scotland and the United States had seen sharp rises in drug-related deaths in the years immediately before the pandemic, but this trend levelled off in Scotland while accelerating dramatically in the United States, particularly among men. Drug-related deaths among men in the United States rose from 33.5 to 51.6 per 100,000 from 2019 to 2021, a 54.1% relative increase. For women in the United States, the increase was also substantial, from 14.4 to 21.2 per 100,000 (47.9% increase).

Fig. 1.

Age-standardised rates of 'deaths of despair' mortality 2001-2021. Shaded grey areas represent the pandemic period.

Table 1.

Changes in age-standardised rates of ‘deaths of despair’ mortality 2019–2021.

| Country | Sex | Cause | Age-standardised deaths per 100,000 |

Change 2019–2021 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Absolute | Relative | |||

| England and Wales | Male | Alcohol | 20.1 | 22.8 | 24.0 | 3.9 | 19.6% |

| Drugs | 10.0 | 10.5 | 11.0 | 1.0 | 9.9% | ||

| Suicide | 14.2 | 13.5 | 14.2 | 0.0 | 0.1% | ||

| Female | Alcohol | 10.4 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 2.5 | 24.1% | |

| Drugs | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 7.8% | ||

| Suicide | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 14.0% | ||

| Northern Ireland | Male | Alcohol | 27.0 | 31.1 | 29.6 | 2.7 | 9.9% |

| Drugs | 13.8 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 2.0 | 14.3% | ||

| Suicide | 17.9 | 19.1 | 20.0 | 2.1 | 11.7% | ||

| Female | Alcohol | 16.1 | 17.5 | 17.4 | 1.4 | 8.4% | |

| Drugs | 4.8 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 15.0% | ||

| Suicide | 5.1 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 1.7 | 33.8% | ||

| Scotland | Male | Alcohol | 30.0 | 36.0 | 37.1 | 7.1 | 23.7% |

| Drugs | 38.8 | 41.5 | 39.8 | 1.0 | 2.5% | ||

| Suicide | 21.9 | 20.9 | 22.2 | 0.2 | 1.0% | ||

| Female | Alcohol | 16.3 | 15.7 | 18.1 | 1.8 | 10.9% | |

| Drugs | 16.3 | 14.9 | 15.9 | −0.4 | −2.6% | ||

| Suicide | 6.8 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 0.0 | −0.1% | ||

| USA | Male | Alcohol | 29.4 | 34.7 | 37.3 | 7.9 | 26.7% |

| Drugs | 33.5 | 44.4 | 51.6 | 18.1 | 54.1% | ||

| Suicide | 26.9 | 26.0 | 27.1 | 0.2 | 0.7% | ||

| Female | Alcohol | 13.6 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 4.0 | 29.1% | |

| Drugs | 14.4 | 18.3 | 21.2 | 6.9 | 47.9% | ||

| Suicide | 6.7 | 6.1 | 6.3 | −0.3 | −5.2% | ||

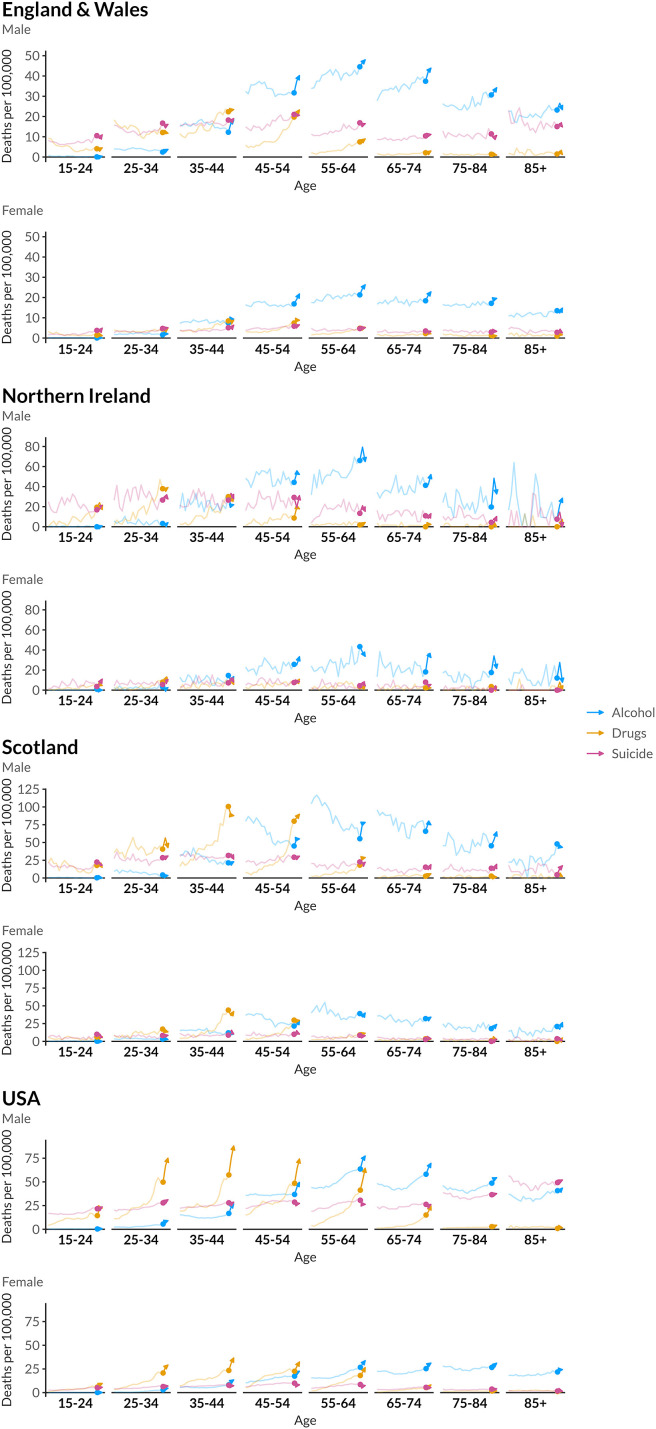

We examined differences in these trends by age in Fig. 2 . In England and Wales, alcohol-specific deaths rose for everyone except the youngest age groups, whereas increases in drug-related deaths were largely confined to 45- to 64-year-old age groups that had seen rising pre-pandemic rates of drug-related mortality. There are few clear age patterns for Northern Ireland, although there is some evidence of an increase in alcohol deaths among those aged >65 years. In Scotland, alcohol-specific deaths rose sharply in men aged >45 years, reversing sharp declines for many years before the pandemic. While drug-related mortality in Scotland had risen steeply in recent years, deaths fell for those aged 35–44 years during the pandemic but continued to rise among 45- to 54-year-old men. Finally, age-specific data for the United States paints an alarming picture, with both alcohol and drug deaths rising sharply across almost every age group.

Fig. 2.

Age-specific rates of 'deaths of despair' mortality 2001-2021. Bold colours represent the pandemic period. Note the y-axis differs between nations.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted daily life on an unprecedented scale, closing schools and businesses and restricting social interactions for many months. Concerns about the mental health impacts of social isolation and other disruptions were raised early on, but it is unclear how much this translated into increased non-COVID mortality. We summarised mortality from three ‘despair’-related causes (alcohol, drug-related, suicide) in the USA and UK nations over the pandemic and compared them to pre-pandemic trends. Despite these concerns, we found little apparent association between the pandemic on deaths by suicide. The most consistent increase across countries was in alcohol-specific deaths. The United States stood alone in its dramatic increase in drug-related deaths, compounding already very high levels. England and Wales and Northern Ireland saw slight increases in drug-related deaths in line with upward previous trends, while changes in drug deaths in Scotland were flat despite a strong upward trend in recent years. These patterns were largely consistent across age groups, with no evidence that younger age groups suffered more.

The COVID-19 pandemic was expected to impact substance use for many reasons. COVID disrupted most aspects of daily life and increased social isolation, potentially increasing the demand for alcohol and drugs to cope with stress. Supply was also impacted by the closures of typical venues for social drinking, such as pubs and restaurants. A priori, the closing of spaces for social drinking could reduce overall drinking if drinking happens less often at home. On the other hand, the pandemic was a shock to people's routines, and working from home could have made it easier to drink at home. Evidence from England and Wales does suggest shifts towards more heavy drinking during the pandemic,7 , 8 , 24 but this is less clear in Scotland.9 In the United States and the United Kingdom, sales of alcohol spiked in March 2020 in anticipation of stay-at-home orders,10 , 25 and surveys suggested more drinking and heavy drinking days in the months that followed. People may have substituted alcohol for legal or illegal drugs that were harder to obtain during the pandemic.26 The consistent increase in alcohol-specific deaths across countries suggests that levels of heavy drinking did increase during the pandemic. Most alcohol-specific deaths are due to alcohol-related liver disease,27 which typically develops over many years,28 in contrast to poisoning, which is more acute but makes up a small percentage of alcohol-specific deaths. Given the sharp increase in alcohol deaths since the pandemic, this suggests that the pandemic induced extra drinking among already heavy drinkers who were near the threshold of succumbing to liver disease.

It is also likely that access to treatment and harm reduction services was reduced during the time of pandemic restrictions, increasing the potential lethality of these behaviours.29 Drug supply shortages can also drive consumption of riskier substances and behaviours such as sharing injecting equipment.30 People may also purchase larger quantities of drugs at one time when they have the opportunity, increasing the risk of overdose. The extent and nature of these issues will vary substantially depending on the local context and the types of drugs implicated in drug-related deaths. In particular, we might expect them to differ between the United States, where rising drug-related deaths are primarily linked to prescription opioids and, more recently, fentanyl,31 and Scotland where the rise in drug-related deaths is strongly linked to ‘street’ benzodiazepines.32

There are some limitations to our analyses. ICD-10 code–based definitions are imperfect, and the use of codes may vary between countries. Our definitions of each cause of death are in line with previous, similar, studies,21 but these do not align completely with existing definitions of ‘alcohol-specific/induced’ deaths as used in the United Kingdom and the United States. We exclude several, generally rare, causes such as alcoholic polyneuropathy (ICD-10 code G62.1), as these cannot be disaggregated in the public mortality data we have used, whereas we have included hepatitis and cirrhosis of the liver (ICD-10 codes K73-74), of which approximately 70% of deaths are estimated to be due to alcohol.33 A comparison of these two definitions shows close alignment of trends (see supplementary material). This approach remains likely to significantly underestimate the true burden of alcohol mortality, as we exclude other conditions for which alcohol is a contributing cause, such as cancers and cardiovascular disease.34 For drug-related and suicide mortality, our approach yields similar figures to the official ‘drug poisoning’/‘drug-induced causes’ and suicide figures published within each country (see supplementary material), with differences accounted for largely by the fact that we have defined our causes of death to be non-overlapping, whereas deaths from deliberate overdoses, for example, may be included in published figures for both suicide and drug-related deaths. Our approach does not account for deaths where multiple causes are implicated, for example, combined alcohol and opioid poisonings, which have been shown to account for a substantial minority of all deaths from alcohol and drug poisoning in the United States.35 Finally, it should be noted that the relatively smaller populations of Northern Ireland and, to a lesser extent Scotland, mean that data for these countries is inherently subject to greater random variation year-on-year and greater caution should therefore be exercised when interpreting annual fluctuations.

Our analysis of age-standardised mortality trends provides straightforward description of changes in these rates during the pandemic. We do not estimate excess mortality by cause, which could more formally incorporate previous trends but is beyond the scope of this analysis. The United States observed substantial differences in drug-related mortality by racial and ethnic group over the pandemic, with overdose mortality particularly accelerating in Black relative to White groups.36 Although beyond the scope of this study, this would be important to incorporate in future explorations of drug-related mortality. Finally, we did not consider socio-economic differences in ‘deaths of despair’, although it has been widely documented that these deaths are clustered in those with lower socio-economic status, particularly in the United States,3 and it is likely that the pandemic widened existing socio-economic gaps in mortality.37 Further investigation of these socio-economic and ethnic differences in mortality trends during the pandemic, and how these may be linked to aspects of the COVID response and wider government policy may help to understand the full impacts of the pandemic on health inequalities.

The data presented here paint a mixed picture of the impact of the pandemic on ‘deaths of despair’ in the USA and UK nations. There is little evidence of an increase in deaths by suicide, a marked increase in deaths due to alcohol and notably different trends in drug-related deaths between countries. The increases in alcohol and drug misuse deaths in the United States are particularly stark and suggest that policy action is urgently required. However, the many-faceted interactions between pre-pandemic trends, the existing policy landscape, the direct impact of the pandemic and pandemic response measures, and the broader societal consequences of these mean that it is vital any public health policy response is tailored to the specific circumstances of both the country and affected populations.

The fact that we have seen further increases in mortality rates in 2021 on top of sharp increases in 2020 for alcohol and, in some cases, drug misuse deaths may suggest that these trends are linked more strongly to wider societal impacts of the pandemic, rather than the short-term policy responses to the initial COVID wave in March 2020. Whether these increases in mortality will return to pre-pandemic levels in the coming years represents a major public health concern, and understanding their underlying drivers is an important challenge that may inform short-term policy responses and guide planning for future pandemics.

Author statements

Ethical approval

All analyses use public available data and ethical approval was not required.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding from the Leverhulme Trust Large Centre Grant, Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science (A.M.T. and J.B.D.) and the European Research Council grant ERC-2021-CoG-101002587 (A.M.T. and J.B.D.), the John Fell Fund, University of Oxford (C.A. and J.B.D.) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AA028009 (C.B.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests

None declared.

Data availability and sharing

All data analysed in this study are publicly available. Code to process these data and reproduce the analysis presented here can be found at https://github.com/VictimOfMaths/DeathsOfDespair/blob/master/DataInsight/DodPandemicPaperFinal.r

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.02.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Aknin L.B., Andretti B., Goldszmidt R., Helliwell J.F., Petherick A., Neve J.E.D., et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. Lancet Public Health. 2022 May 1;7(5):e417–e426. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Han H., Barry C.L. Trends in psychological distress among US adults during different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jan 24;5(1) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Case A., Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015 Dec 8;112(49):15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sterling P., Platt M.L. Why deaths of despair are increasing in the US and not other industrial nations—insights from neuroscience and anthropology. JAMA Psychiatr. 2022 Apr 1;79(4):368–374. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowd J.B., Angus C., Zajacova A., Tilstra A.M. Midlife “deaths of despair” trends in the US, Canada, and UK, 2001-2019: is the US an anomaly? [Internet] medRxiv. 2022 https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.10.22280916v1 [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 6.HM Revenue & Customs. Alcohol Bulletin [Internet]. GOV.UK. [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/alcohol-bulletin.

- 7.Jackson S.E., Garnett C., Shahab L., Oldham M., Brown J. Association of the COVID-19 lockdown with smoking, drinking and attempts to quit in England: an analysis of 2019–20 data. Addiction. 2021;116(5):1233–1244. doi: 10.1111/add.15295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson S.E., Beard E., Angus C., Field M., Brown J. Moderators of changes in smoking, drinking and quitting behaviour associated with the first COVID-19 lockdown in England. Addiction [Internet] 2021;117(3) doi: 10.1111/add.15656. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/add.15656 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevely A.K., Sasso A., Hernandez Alava M., Holmes J. Public Health Scotland; Edinburgh: 2021. Changes in alcohol consumption in Scotland during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: descriptive analysis of repeat cross-sectional survey data [Internet] p. 86.https://www.publichealthscotland.scot/media/2983/changes-in-alcohol-consumption-in-scotland-during-the-early-stages-of-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollard M.S., Tucker J.S., Green H.D., Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Sep 29;3(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schofield J., Dumbrell J., Matheson C., Parkes T., Bancroft A. The impact of COVID-19 on access to harm reduction, substance use treatment and recovery services in Scotland: a qualitative study. BMC Publ Health. 2022 Mar 15;22(1):500. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12873-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bright Cordis. Make Every Adult Matter; 2020. Flexible responses during the Coronavirus crisis: rapid evidence gathering [Internet]http://meam.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/MEAM-Covid-REG-report.pdf [cited 2022 Dec 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirkis J., John A., Shin S., DelPozo-Banos M., Arya V., Analuisa-Aguilar P., et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatr. 2021 Jul 1;8(7):579–588. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes J., Angus C. Alcohol deaths rise sharply in England and Wales. BMJ. 2021 Mar 5;372:n607. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedegaard H., Miniño A., Spencer M.R., Warner M. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2021 Dec. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2020 [Internet]https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/112340 [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.White A.M., Castle I.J.P., Powell P.A., Hingson R.W., Koob G.F. Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2022 May 3;327(17):1704–1706. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office for National Statistics. Deaths registered in England and Wales – 21st century mortality [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/the21stcenturymortalityfilesdeathsdataset.

- 18.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Registrar General Annual Report [Internet]. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/births-deaths-and-marriages/registrar-general-annual-report.

- 19.National Records of Scotland. Vital Events reference tables [Internet]. National Records of Scotland. National Records of Scotland; [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/vital-events-reference-tables.

- 20.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/Deaths-by-Underlying-Cause.html.

- 21.Masters R.K., Tilstra A.M., Simon D.H. Explaining recent mortality trends among younger and middle-aged White Americans. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Feb 1;47(1):81–88. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pace M, Lanzieri G, Glickman M, Grande E, Zupanic T, Wojtyniak B, et al. Revision of the European standard population - Report of Eurostat's task force - 2013 edition [Internet]. Eurostat; [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2785/11470.

- 23.Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany), University of California, Berkeley (USA), and French Institute for Demographic Studies (France). HMD. Human Mortality Database [Internet]. Available from: www.mortality.org.

- 24.Angus C., Henney M., Pryce R. The University of Sheffield; 2022 Jul. Modelling the impact of changes in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic on future alcohol-related harm in England [Internet]https://figshare.shef.ac.uk/articles/report/Modelling_the_impact_of_changes_in_alcohol_consumption_during_the_COVID-19_pandemic_on_future_alcohol-related_harm_in_England/19597249/1 [cited 2022 Nov 11]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finlay I., Gilmore I. COVID-19 and alcohol—a dangerous cocktail. BMJ. 2020 May 20;369:m1987. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime . 2020. COVID-19 and the drug supply chain: from production and trafficking to use [Internet]https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf Vienna. [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office for National Statistics . 2022. Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK 2021 [Internet]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/alcoholspecificdeathsintheuk/2021registrations [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osna N.A., Donohue T.M., Kharbanda K.K. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):147–161. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v38.2.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacka B.P., Janssen T., Garner B.R., Yermash J., Yap K.R., Ball E.L., et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare access among patients receiving medication for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Apr 1;221 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otiashvili D., Mgebrishvili T., Beselia A., Vardanashvili I., Dumchev K., Kiriazova T., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on illicit drug supply, drug-related behaviour of people who use drugs and provision of drug related services in Georgia: results of a mixed methods prospective cohort study. Harm Reduct J. 2022 Mar 9;19(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s12954-022-00601-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Pol. 2019 Sep 1;71:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAuley A., Matheson C., Robertson J. From the clinic to the street: the changing role of benzodiazepines in the Scottish overdose epidemic. Int J Drug Pol. 2022 Feb 1;100 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaccard A., Blawat A., Ashton S., Belsman L., Gommon J., Webber L., et al. Public Health England; London: 2020. Alcohol-attributable fractions for England: an update [Internet]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/958648/RELATI_1-1.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rehm J., Gmel Sr G.E., Gmel G., Hasan O.S.M., Imtiaz S., Popova S., et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease—an update. Addiction. 2017;112(6):968–1001. doi: 10.1111/add.13757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckley C., Ye Y., Kerr W.C., Mulia N., Puka K., Rehm J., et al. Trends in mortality from alcohol, opioid, and combined alcohol and opioid poisonings by sex, educational attainment, and race and ethnicity for the United States 2000–2019. BMC Med. 2022 Oct 24;20(1):405. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02590-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman J.R., Hansen H. Evaluation of increases in drug overdose mortality rates in the US by race and ethnicity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatr. 2022 Apr 1;79(4):379–381. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokes A.C., Lundberg D.J., Elo I.T., Hempstead K., Bor J., Preston S.H. COVID-19 and excess mortality in the United States: a county-level analysis. PLoS Med. 2021 May 20;18(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data analysed in this study are publicly available. Code to process these data and reproduce the analysis presented here can be found at https://github.com/VictimOfMaths/DeathsOfDespair/blob/master/DataInsight/DodPandemicPaperFinal.r