Abstract

Background

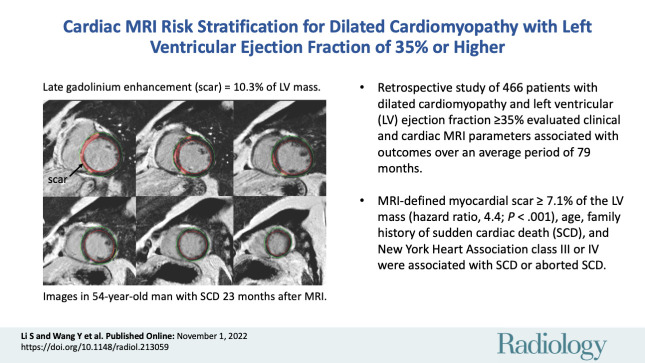

Studies over the past 15 years have demonstrated that a considerable number of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) who died from sudden cardiac death (SCD) had a left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or higher.

Purpose

To identify clinical and cardiac MRI risk factors for adverse events in patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or higher.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study, consecutive patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or higher who underwent cardiac MRI between January 2010 and December 2017 were included. The primary end point was a composite of SCD or aborted SCD. The secondary end point was a composite of all-cause mortality, heart transplant, or hospitalization for heart failure. The risk factors for the primary and secondary end points were identified with multivariable Cox analysis.

Results

A total of 466 patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or higher (mean age, 44 years ± 14 [SD]; 358 men) were included. During a mean follow-up of 79 months ± 30 (SD) (range, 7–143 months), 40 patients reached the primary end point and 61 reached the secondary end point. In the adjusted analysis, age (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03 per year [95% CI: 1.00, 1.05]; P = .04), family history of SCD (HR, 3.4 [95% CI: 1.3, 8.8]; P = .01), New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV (HR vs NYHA class I or II, 2.1 [95% CI: 1.1, 3.9]; P = .02), and myocardial scar at late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) MRI greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass (HR, 4.4 [95% CI: 2.4, 8.3]; P < .001) were associated with SCD or aborted SCD. For the composite secondary end point, LGE greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass (HR vs LGE <7.1%, 2.0 [95% CI: 1.2, 3.4]; P = .01), left atrial maximum volume index, and reduced global longitudinal strain were independent predictors.

Conclusion

For patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction of 35% or higher, cardiac MRI–defined myocardial scar greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass was associated with sudden cardiac death (SCD) or aborted SCD.

© RSNA, 2022

Summary

Late gadolinium enhancement MRI appears useful to identify patients who have dilated cardiomyopathy with left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or higher and who are at risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD) or aborted SCD.

Key Results

■ The relationship between clinical factors, cardiac MRI parameters, and outcomes was evaluated over an average of 79 months in 466 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy whose left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was 35% or higher.

■ In adjusted analysis, myocardial scar at cardiac MRI of 7.1% or more of the LV mass (hazard ratio, 4.4; P < .001), age, family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD), and New York Heart Association class III or IV were all associated with SCD or aborted SCD.

Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is characterized by left ventricular (LV) dilation and systolic dysfunction and has a 5-year mortality rate of 20% (1). Sudden cardiac death (SCD) has a prevalence of approximately 30% among patients with DCM and is a major cause of death in this group (2). An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is considered an effective approach to prevent SCD. Currently, the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology recommend ICDs for SCD prevention in those patients who meet the criteria for New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or III and have an LV ejection fraction (LVEF) lower than 35% (3,4).

However, studies over the past 15 years indicate that many patients with DCM who die of SCD tend to have only mild or moderate systolic dysfunction. A registry study of outpatients with DCM who experienced SCD found that approximately 70%–80% had an LVEF of 35% or higher (5). Additionally, a study by Gorgels et al (6) found that among 200 patients with SCD, only 38 (19%) had an LVEF under 30%, and 61 (30.5%) had an LVEF between 30% and 50%. Therefore, identifying specific risk factors for SCD in patients who have DCM and LVEF of 35% or higher is important for establishing therapeutic guidelines in this patient group for treatments such as ICD placement—with the ultimate goal of improving the outcomes of DCM.

Cardiac MRI is a noninvasive imaging study that uses multiplanar and multiparametric imaging to comprehensively assess myocardial structure, function, and tissue characteristics. Previous publications have reported that late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) has a strong prognostic value for SCD risk stratification in patients with DCM whose LVEF is 35% or higher and have recommended that it be incorporated as a part of the patient selection criteria for primary prevention treatments, such as ICD placement (7–9). However, these prior studies have mainly focused on the presence and the distribution of the LGE and did not further analyze the impact of the extent of the LGE (9). In addition, previous research has mostly focused on one cardiac MRI parameter (LGE) and has not combined clinical and laboratory tests and MRI parameters to form a final model for risk stratification of patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or higher (8).

Thus, we aimed to find the risk factors for SCD in patients with DCM and an LVEF of 35% or higher to further establish a model for predicting adverse events in this population.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was approved by our hospital ethics committee (approval no. 2019–1236). Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Consecutive patients with DCM who underwent gadolinium-enhanced cardiac MRI at our hospital between January 2010 and December 2017 were retrospectively enrolled in this study. As a routine clinical practice at our hospital, all patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy undergo MRI examinations unless they have contraindications or refuse MRI. The inclusion criteria for enrollment in this study were (a) diagnosis of DCM according to the World Health Organization and International Society and Federation of Cardiology definitions of DCM (10) based on a reduced LVEF and LV end-diastolic volume greater than 2 SDs from normal according to nomograms corrected for body surface area and age (11) and (b) LVEF of 35% or higher. Exclusion criteria were (a) any evidence indicating the presence of ischemic heart disease, an infarct pattern of LGE on cardiac MRI studies, and/or acute coronary syndrome or coronary revascularization during follow-up and (b) any evidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, moderate to severe valvular disease (12), or infiltrative disease. Clinical data and family history were also collected. Follow-up data were obtained by means of telephone interviews, hospital records, and clinical visits.

The primary end point was a composite of SCD or aborted SCD. SCD was defined as unexpected death within 1 hour of cardiac symptoms in the absence of any progressive cardiac deterioration, during sleep, or 24 hours or less of the patient last being seen alive (13). Aborted SCD was defined as an appropriate ICD shock for ventricular arrhythmia, a nonfatal episode of ventricular fibrillation, or spontaneous sustained ventricular tachycardia causing hemodynamic compromise and requiring cardioversion (14). The secondary end point was a composite of all-cause mortality, heart transplant, or hospitalization for heart failure. All outcome events were adjudicated by physicians blinded to the cardiac MRI data and confirmed from a combination of medical records, clinical visits, and telephone interviews. For composite end points, only the first event for each patient was included in the analysis. Overall survival was defined as the duration between the entry date and the date of end points or last follow-up (censored).

Cardiac MRI Protocols and Image Analysis

All studies were performed at 1.5 T (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Healthineers). Steady-state free-precession cine images were obtained in a four-chamber view and two-chamber view, as well as sequential short-axis sections from the mitral annulus to the LV apex during a breath hold with the following parameters: section thickness, 8 mm; section gap, 2 mm; repetition time, 3.0 msec; echo time, 1.1 msec; matrix size, 256 × 256; pixel size, 2.2 mm × 1.6 mm; and temporal resolution, 38–45 msec per frame depending on the R-R interval. A gradient-spoiled turbo fast low-angle shot sequence with phase-sensitive inversion-recovery technique was used for the LGE images. LGE images were acquired 15 minutes after the intravenous administration of the gadolinium contrast agent (0.15 mmol/kg, gadopentetate dimeglumine [Magnevist, Bayer Healthcare]) in the four-chamber view, two-chamber view, and a series of contiguous 6-mm LV short-axis sections that covered the entire left ventricle.

All cardiac MRI data were then transferred to an offline workstation with commercial postprocessing software Argus (VA60C, Siemens Healthineers) and CVI42 (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging). A radiologist (S.L., with 5 years of experience in cardiac MRI) who was blinded to the clinical data performed the image analysis. The image quality was evaluated by means of visual assessment before image analysis. Image sharpness and different types of artifacts were assessed. If image sharpness or the presence of artifacts interfered with visualization of the myocardium, preventing accurate image analysis, the image quality was considered poor. The left atrial dimension, LV end-diastolic diameter, LV and right ventricular end-diastolic volumes, LV and right ventricular end-systolic volumes, LV mass, LVEF, and right ventricular ejection fraction were measured by means of standard volumetric techniques (15,16). The biplane area-length method was used to calculate the maximum left atrial volume (in milliliters) according to the following equation (17): left atrial volume = 0.85 × (A2Ch × A4Ch)/L, where A2Ch and A4Ch refer to the left atrial areas on the two- and four-chamber views, respectively, and L is the shorter left atrial length (midpoint of the mitral annulus plane to the superior aspect of the left atrium) from either the two- or four-chamber view (18). LV end-diastolic and -systolic volumes, LV mass, and left atrial volume were adjusted for body surface area and expressed as indexes. LGE was semiautomatically quantified using the full width half maximum method (19). To measure strain, the endocardial and epicardial borders were traced on the entire stack of steady-state free-precession cine short-axis and two- and four-chamber long-axis images at end diastole by artificial intelligence, and then these contours were tracked throughout the entire cardiac cycle. Manual correction was performed in case tracking by the artificial intelligence was inadequate. The following myocardial strain parameters were derived: peak systolic global longitudinal strain (GLS), global radial strain (GRS), and global circumferential strain (GCS) (20).

Inter- and intraobserver variability were assessed in 20 randomly selected patients, such that one observer (S.L.) performed one measurement, and a second observer (M.L., with 15 years of experience in cardiac MRI) blinded to the first observer’s results performed measurements at two time points at least 1 week apart.

Statistical Analysis

According to the rule of thumb for Cox regression models, potential factors should have a minimum of 10 events per predictor variable for an adequate sample size (21). The 40 SCD or SCD-equivalent end points observed in this cohort allowed for using four prespecified candidate predictors to develop a model. Values were expressed as means ± SDs or numbers of patients with percentages. Inter- and intraobserver variability were calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient. Univariable comparisons were performed with use of the Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Fisher exact test for normally distributed, nonnormally distributed, and categorical variables, respectively. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to determine the best threshold for quantitative variables to detect the end points. The optimal cutoff point was identified using the Youden index, which was at the maximum of sensitivity + specificity − 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were calculated for each group of patients stratified by the optimal cutoff value, along with a log-rank test. Univariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to test the association between the end points and baseline or imaging parameters (unadjusted hazard ratios [HRs] and 95% CIs). Multivariable analyses were performed and reported with adjusted HRs and 95% CIs. For similar imaging parameters, one variable was introduced into the model at a time—for example, myocardial strain parameters were incorporated as GLS, GRS, or GCS individually. For the secondary end point, GLS, GRS, and GCS were each combined with variables that were statistically significant in the univariable Cox analysis (NYHA class, left atrial maximum volume index [LAVi], and LGE) to form the three final models. The proportional hazards assumptions were assessed by visual inspection of log-log plots. C-statistics were calculated to assess the discriminative ability of the model, with larger values indicating better discrimination. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 software (IBM) and R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Results were considered statistically significantly different if P < .05.

Results

Patients

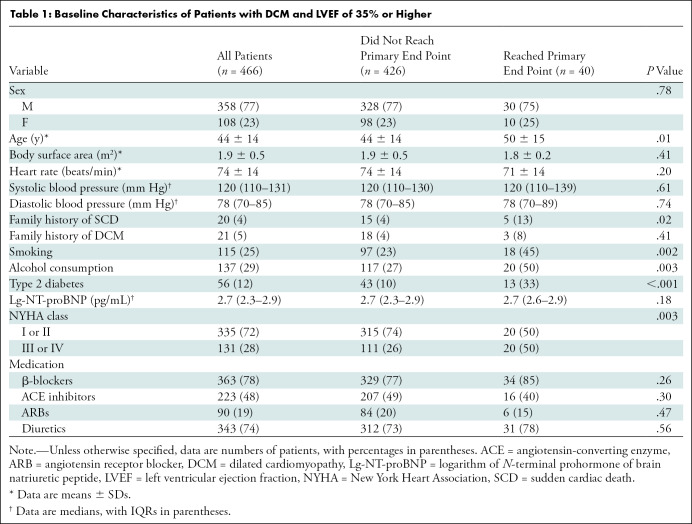

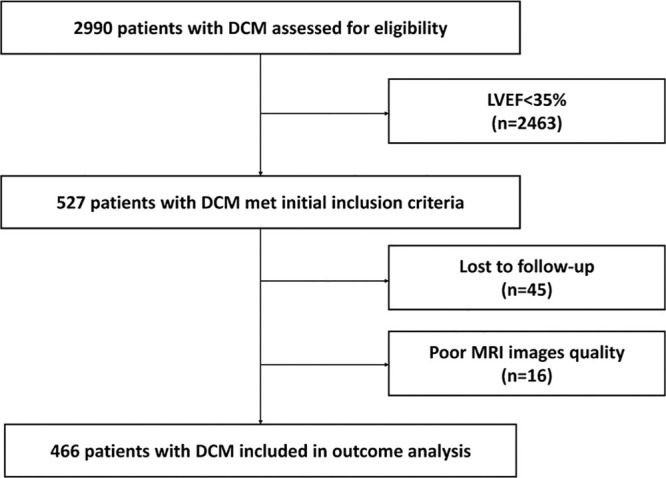

A total of 527 patients met the initial inclusion criteria. Of these, 45 were lost to follow-up and 16 had poor cardiac MRI quality (Fig 1). Thus, the final cohort consisted of 466 patients (358 men [77%]) with an average age of 44 years ± 14 (range, 14–80 years). Of the 466 patients, 21 had a family history of DCM and 20 had a family history of SCD. Most of the patients (335 of 466 [72%]) were in NYHA class I or II. The detailed baseline characteristics of the patient cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1:

Flowchart shows patient inclusion. DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy, LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or Higher

During a mean follow-up period of 79 months ± 30 (range, 7–143 months), a total of 40 patients reached the primary end point (cumulative event rate, 8.6%); 16 (16 of 466 [3.4%]) had SCD and 24 (5.2%) had aborted SCD (eight [1.7%] had a nonfatal episode of ventricular fibrillation, three [0.6%] had sustained ventricular tachycardia, and 13 [2.8%] had appropriate ICD shock). A total of 61 patients reached the secondary end point (cumulative event rate, 13%); 18 (18 of 466 [3.9%]) died of heart failure, 16 (3.4%) died of SCD, four (0.9%) underwent heart transplant, three (0.6%) died of other reasons (two of cancer [0.4%] and one of cerebral infarction [0.2%]), and 20 (4.3%) were hospitalized for heart failure.

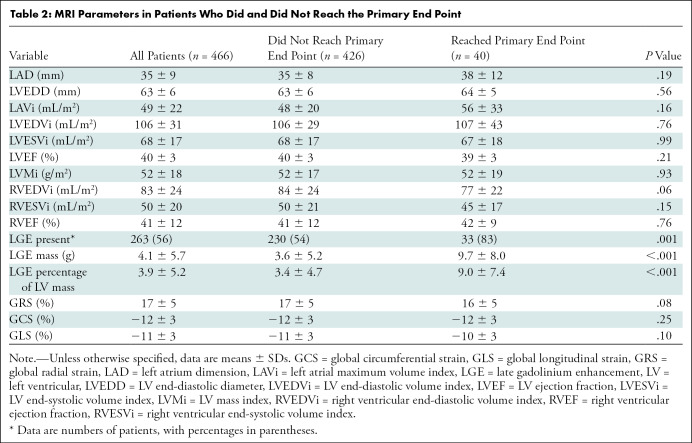

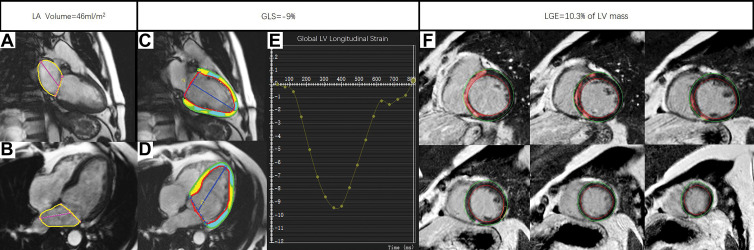

Patients who reached the primary end point were older (mean age, 50 years ± 15 vs 44 years ± 14; P = .01) and were more likely to be smokers (18 of 40 [45%] vs 97 of 426 [23%]; P = .002). There was no significant difference among sex, family history of DCM, and medications (all P > .05). More patients in the group that reached the primary end point had a family history of SCD (five of 40 [13%] vs 15 of 426 [3.5%]; P = .02). Fifty percent of the patients reaching the primary end point (20 of 40) were in NYHA class III or IV. There was no significant difference in LV end-diastolic diameter, LAVi, ventricular functional parameters, or strain parameters between the groups that did and did not reach the primary end point (all P > .05). A total of 263 patients (263 of 466 [56%]) had a nonischemic pattern of LGE, of whom 33 reached the primary end point and 230 did not (P = .001). Both the LGE mass and the LGE percentage of the LV mass were higher in the group that reached the primary end point than in the group that did not (both P < .001). The detailed MRI findings of the cohort are shown in Table 2. An example of a patient with DCM who experienced SCD is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2:

MRI Parameters in Patients Who Did and Did Not Reach the Primary End Point

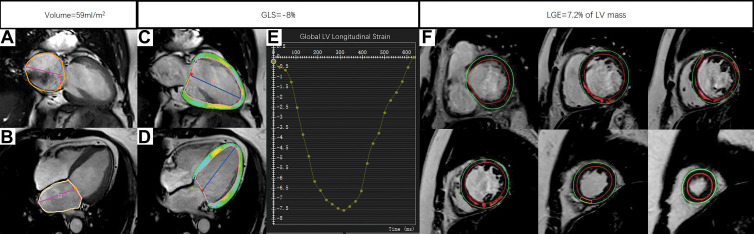

Figure 2:

Example MRI studies in a 54-year-old male patient who experienced sudden cardiac death 23 months after the cardiac MRI examination. The maximum left atrial volume index was calculated by the measuring the left atrial area (yellow outlines) and left atrial length (magenta lines) in (A) two-chamber view and (B) four-chamber view at end systole with use of the biplane area-length method. The global longitudinal strain (GLS) was obtained by tracing the endocardial (red) and epicardial (green) borders on the (C) two-chamber and (D) four-chamber long-axis images throughout the entire cardiac cycle, while the green, yellow, and cyan shading represents left ventricular (LV) longitudinal strain measurements. The blue lines indicate LV length. (E) The line plot of strain curve shows GLS to be −9%. The burden of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was quantified using the full width half maximum method by drawing the endocardial (red line) and epicardial (green line) borders on (F) a stack of LV short-axis LGE images. The red shading represents quantified LGE.

Patients who reached the secondary end point had higher LAVi (58 mL/m2 ± 29 vs 47 mL/m2 ± 20; P = .01), lower LVEF (39% ± 3 vs 40% ± 3; P = .03), and worse GLS (−10% ± 3 vs −11% ± 3; P = .003) (Table S1). An example of a patient with DCM who reached the secondary end point is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3:

Example MRI studies in a 59-year-old male patient who was hospitalized for heart failure 29 months after the cardiac MRI examination. The maximum left atrial volume index was calculated by the measurements of left atrial area (orange outlines) and left atrial length (magenta lines) in (A) two-chamber view and (B) four-chamber view at end systole with use of the biplane area-length method. The global longitudinal strain (GLS) was obtained by tracing the endocardial (red) and epicardial (green) borders on the (C) two-chamber and (D) four-chamber long-axis images throughout the entire cardiac cycle. The green, yellow, and cyan shading represents left ventricular (LV) longitudinal strain measurements, and the blue lines indicate LV length. (E) The strain curve derived from postprocessing shows GLS to be −8%. The burden of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was quantified using the full width half maximum method by drawing the endocardial (red) and epicardial (green) borders on (F) a stack of LV short-axis LGE images. The red shading represents quantified LGE.

MRI and Clinical Factors in Relationship to the Primary End Point

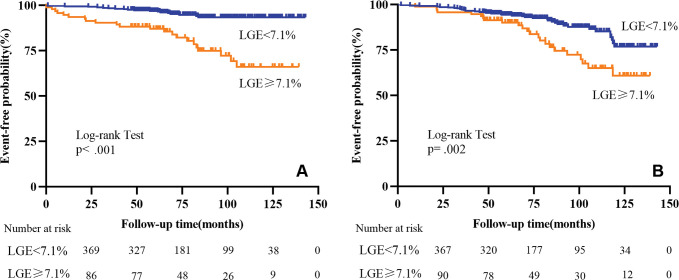

Age, NYHA class, family history of SCD, and LGE percentage of the LV mass were all associated with the primary end point (all P < .05) (Table S2). Receiver operating characteristic analysis demonstrated that the optimal cutoff value of the LGE percentage for the primary end point was 7.1% of the LV mass, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.73 (Table S2). Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that patients with an LGE percentage of 7.1% of the LV mass or greater were more likely to experience an SCD composite event (log-rank test: P < .001) (Fig 4A).

Figure 4:

Kaplan-Meier curves for late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and the (A) primary end point and (B) secondary end point for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or higher.

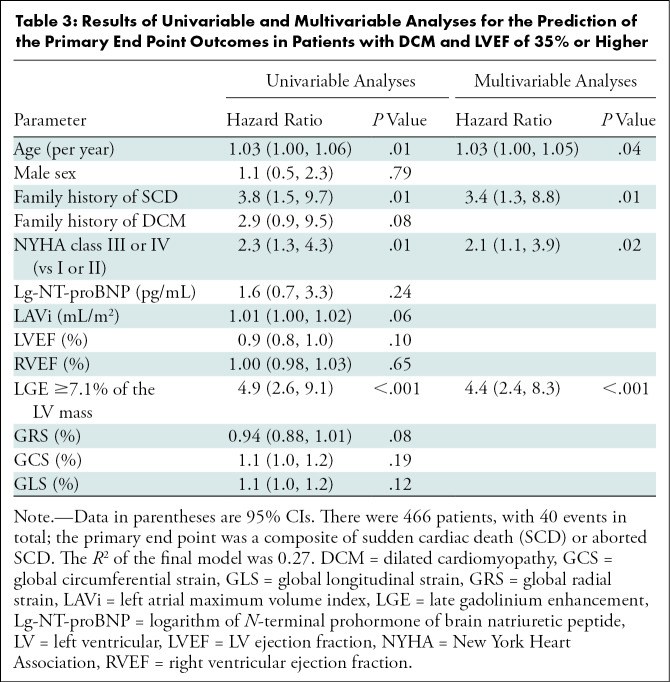

At univariable Cox regression analyses, age, family history of SCD, NYHA class III or IV, and LGE percentage of the LV mass all showed significant associations with the primary end point (all P < .05) (Table 3). Multivariable stepwise analyses showed that age, family history of SCD, NYHA class III or IV, and LGE percentage of the LV mass were associated with the primary end point (all P < .05) (Tables 3, S3). The LGE cutoff value of 7.1% of the LV mass gave the largest C-statistics for the primary end point (C-statistic, 0.75; P < .001), and the estimated adjusted HR for patients with LGE extent greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass was 4.4 (95% CI: 2.4, 8.3; P < .001) when compared with those with LGE less than 7.1% of the LV mass. The log-log plots of the variables were nearly parallel, which verified the proportional hazards assumption (Figure S1).

Table 3:

Results of Univariable and Multivariable Analyses for the Prediction of the Primary End Point Outcomes in Patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or Higher

MRI and Clinical Factors in Relationship to the Secondary End Point

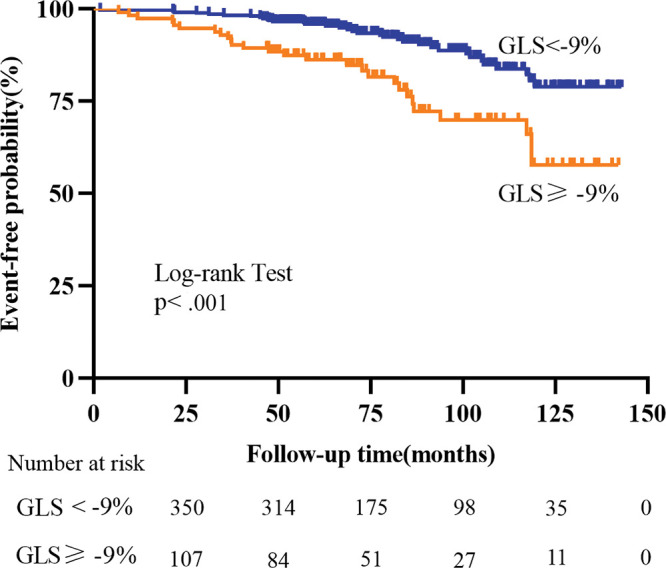

NYHA class, LVEF, LAVi, LGE percentage of the LV mass, GRS, GCS, and GLS were all associated with the secondary end point (all P < .05) (Table S4). Receiver operating characteristic analysis demonstrated that the optimal cutoff value for LVEF, LAVi, and the strain parameters GRS, GCS, and GLS were 40%, 47 mL/m2, 13%, −12%, and −9%, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that patients with LGE percentage greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass (log-rank test: P = .002) (Fig 4B) or GLS of −9% or greater (log-rank test: P < .001) (Fig 5) had significantly shorter survival.

Figure 5:

Kaplan-Meier curves for global longitudinal strain (GLS) and the secondary end point for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or higher.

At univariable Cox regression analyses, LAVi greater than or equal to 47 mL/m2, NYHA class III or IV, LVEF of 40% or lower, LGE greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass, GRS of 13% or lower, GCS of −12% or higher, and GLS of −9% or higher all showed significant associations with the secondary end point (all P < .05) (Table 4). After the inclusion of GRS, GCS, and GLS in the model, GLS had the largest C-statistic (0.71, P < .001) for the secondary end point (Table S5). In the adjusted model, GLS of −9% or higher showed a 2.5-fold greater risk of death, heart transplant, or hospitalization for heart failure. LGE greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass (HR, 2.0 [95% CI: 1.2, 3.4]; P = .01) was a significant predictor of the secondary end point in multivariable stepwise analysis. The log-log plots of the variables were nearly parallel, which verified the proportional hazards assumption (Figure S2).

Table 4:

Results of Univariable and Multivariable Analyses for the Prediction of the Secondary End Point Outcomes in Patients with DCM and LVEF of 35% or Higher

MRI Strain and Clinical Factors in Relationship to the Secondary End Point

We evaluated the role of myocardial strain in relationship to the secondary composite end point (Table 4). GRS, GCS, and GLS all had significant associations with all-cause mortality, heart transplant, or hospitalization for heart failure. However, at univariable analysis, GLS had the highest HR (2.6). Inclusion of GLS in the model had the largest C-statistic for the secondary end point (0.71, P < .001) (Table S5). At multivariable analysis, GLS of −9% or greater was an independent risk factor for the secondary end point (HR, 2.5 [95% CI: 1.5, 4.1]; P = .001). Strain parameters, including GRS, GCS, and GLS, were not associated with the SCD composite events at univariable analysis (all P > .05); therefore, they were not incorporated into the multivariable analysis of the primary end point.

Intra- and Interobserver Variability

Both intra- and interobserver variability were good to excellent for LV function, LGE, and strain parameters (Table S6). In particular, for LAVi and GLS, the intra- and interobserver intraclass correlation coefficients were both greater than 0.95.

Discussion

In our study, we identified risk factors for sudden cardiac death (SCD) composite events as well as all-cause mortality, heart transplant, and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy whose left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was 35% or higher. We found that patients who had late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) greater than or equal to 7.1% of the LV mass showed a 4.4-fold increased risk of SCD composite events, while patients who had global longitudinal strain of −9% or greater showed a 2.5-fold increased risk of death, heart transplant, or hospitalization for heart failure. We found that LGE percentage of the LV mass was an independent risk factor for both the primary and secondary end points in our study.

Prior studies have shown that the presence of LGE represents collagen or replacement fibrosis and is an independent predictor of cardiovascular death and ventricular arrhythmia events (22,23). A prior meta-analysis showed a significant association between LGE presence and arrhythmic end points in patients with DCM and a LVEF of 35% or higher (odds ratio, 5.2 [95% CI: 3.4, 7.9]; P < .001) (24). Interestingly, we also found GLS to be an independent risk factor for the secondary end point. Prior studies have suggested that GLS has a better prognostic value than LVEF in predicting major adverse cardiac events (25,26). Mignot et al (27) found that strain analysis is feasible and reliable in patients with depressed LV function and appears to have great accuracy for cardiovascular risk stratification. Sengeløv et al (28) have stated that myocardial strain is a better predictor of events because the strain technique directly investigates myocardial contraction segmentally. GCS was not significantly associated with the primary outcome in our study, which is similar to the results obtained by Chimura et al (29).

Higher NYHA functional class is a classic prognostic factor of poor outcome in heart failure (30). The NYHA class is related to the left atrial pressure, LVEF, and brain natriuretic peptide level. Gulati et al (31) found that NYHA class was associated with a 1.8-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality or cardiac transplant per class. Our results were similar. NYHA class III or IV was an independent predictor of SCD composite events (HR, 2.1 [95% CI: 1.1, 3.9]; P = .02) as well as all-cause mortality, heart transplant, and hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 2.0 [95% CI: 1.2, 3.3]; P = .01). However, we found that the HR for NYHA class was lower than that of GLS. The advantage of the NYHA class lies in its simplicity, and thus, it is widely used during clinical evaluation, but a disadvantage is that it depends on the patients’ subjective statements. Sometimes, there is a large gap between patient symptoms and examination findings, and there are also great differences in how individual patients perceive their own symptoms.

There are some limitations in our study. First, this was a single-center retrospective study that may be subject to referral bias. A randomized controlled trial with a larger sample size is needed to further validate the results of our study. Second, LGE was an independent risk factor for both the primary and secondary end points in our study. The incidence of adverse events in patients without LGE was not high, which limited our risk stratification of these patients. Third, the reproducibility of the ejection fraction is limited. Averaging multiple measurements may be a way to reduce bias. In addition, low P values do not always correspond to useful prediction. The C-statistics are modest; therefore, additional studies will be needed to determine if the variables identified in this study are strong enough to guide therapeutic decisions. Finally, as we only included patients with LVEF of 35% or higher, it impossible to comprehensively assess the relationship between LVEF and LGE in risk stratification of all patients with DCM.

In conclusion, both MRI-derived late gadolinium enhancement and global longitudinal strain can be used to identify a group of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or higher who are at an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD), all-cause mortality, heart transplant, and hospitalization for heart failure. Cardiac MRI assessment should be incorporated in this patient population and may be useful in the selection criteria for therapies aimed at preventing SCD, such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement.

S.L. and Y.W. contributed equally to this work.

A.E.A. and S.Z. are co–senior authors.

Supported by the Capital Clinically Characteristic Applied Research Fund (grant Z191100006619021), Construction Research Project of the Key Laboratory (Cultivation) of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (grant 2019PT310025), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81971588 and 81771811), Youth Key Program of High-level Hospital Clinical Research (grant 2022-GSP-QZ-5), and Clinical and Translational Fund of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (grant 2019XK320063).

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: S.L. No relevant relationships. Y.W. No relevant relationships. W.Y. No relevant relationships. D.Z. No relevant relationships. B.Z. No relevant relationships. J.X. No relevant relationships. J.H. No relevant relationships. G.Y. No relevant relationships. X.F. No relevant relationships. W.W. No relevant relationships. P.S. No relevant relationships. A.S. No relevant relationships. A.E.A. Licensing fees from Circle Cardiovascular Imaging; consulting fees from Bayer and Circle Cardiovascular Imaging; payment for lectures from Radcliffe; patent pending for perfusion quantification; participant on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for the National Institutes of Health. S.Z. No relevant relationships. M.L. No relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- DCM

- dilated cardiomyopathy

- GCS

- global circumferential strain

- GLS

- global longitudinal strain

- GRS

- global radial strain

- HR

- azard ratio

- ICD

- implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- LAVi

- left atrial maximum volume index

- LGE

- late gadolinium enhancement

- LV

- left ventricular

- LVEF

- LV ejection fraction

- NYHA

- New York Heart Association

- SCD

- sudden cardiac death

References

- 1. Gulati A , Jabbour A , Ismail TF , et al . Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy . JAMA 2013. ; 309 ( 9 ): 896 – 908 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tamburro P , Wilber D . Sudden death in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy . Am Heart J 1992. ; 124 ( 4 ): 1035 – 1045 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yancy CW , Jessup M , Bozkurt B , et al . 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America . J Am Coll Cardiol 2017. ; 70 ( 6 ): 776 – 803 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ponikowski P , Voors AA , Anker SD , et al . 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC . Eur Heart J 2016. ; 37 ( 27 ): 2129 – 2200 . [Published correction appears in Eur Heart J 2018;39(10):860.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stecker EC , Vickers C , Waltz J , et al . Population-based analysis of sudden cardiac death with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: two-year findings from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study . J Am Coll Cardiol 2006. ; 47 ( 6 ): 1161 – 1166 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gorgels AP , Gijsbers C , de Vreede-Swagemakers J , Lousberg A , Wellens HJ . Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest—the relevance of heart failure. The Maastricht Circulatory Arrest Registry . Eur Heart J 2003. ; 24 ( 13 ): 1204 – 1209 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Halliday BP , Gulati A , Ali A , et al . Association between midwall late gadolinium enhancement and sudden cardiac death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and mild and moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction . Circulation 2017. ; 135 ( 22 ): 2106 – 2115 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klem I , Klein M , Khan M , et al . Relationship of LVEF and myocardial scar to long-term mortality risk and mode of death in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy . Circulation 2021. ; 143 ( 14 ): 1343 – 1358 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Marco A , Brown PF , Bradley J , et al . Improved risk stratification for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy . J Am Coll Cardiol 2021. ; 77 ( 23 ): 2890 – 2905 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinto YM , Elliott PM , Arbustini E , et al . Proposal for a revised definition of dilated cardiomyopathy, hypokinetic non-dilated cardiomyopathy, and its implications for clinical practice: a position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases . Eur Heart J 2016. ; 37 ( 23 ): 1850 – 1858 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhuang B , Li S , Xu J , et al . Age- and sex-specific reference values for atrial and ventricular structures in the validated normal Chinese population: a comprehensive measurement by cardiac MRI . J Magn Reson Imaging 2020. ; 52 ( 4 ): 1031 – 1043 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishimura RA , Otto CM , Bonow RO , et al . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014. ; 148 ( 1 ): e1 – e132 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hicks KA , Tcheng JE , Bozkurt B , et al . 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards) . J Am Coll Cardiol 2015. ; 66 ( 4 ): 403 – 469 . [Published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66(8):982.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buxton AE , Calkins H , Callans DJ , et al . ACC/AHA/HRS 2006 key data elements and definitions for electrophysiological studies and procedures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (ACC/AHA/HRS Writing Committee to Develop Data Standards on Electrophysiology) . J Am Coll Cardiol 2006. ; 48 ( 11 ): 2360 – 2396 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li S , Wu B , Yin G , et al . MRI characteristics, prevalence, and outcomes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with restrictive phenotype . Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2020. ; 2 ( 4 ): e190158 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu J , Zhuang B , Sirajuddin A , et al . MRI T1 mapping in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: evaluation in patients without late gadolinium enhancement and hemodynamic obstruction . Radiology 2020. ; 294 ( 2 ): 275 – 286 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lang RM , Bierig M , Devereux RB , et al . Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology . J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005. ; 18 ( 12 ): 1440 – 1463 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He J , Sirajuddin A , Li S , et al . Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in hypertension patients: a myocardial MR strain study . J Magn Reson Imaging 2021. ; 53 ( 2 ): 527 – 539 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flett AS , Hasleton J , Cook C , et al . Evaluation of techniques for the quantification of myocardial scar of differing etiology using cardiac magnetic resonance . JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011. ; 4 ( 2 ): 150 – 156 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andre F , Steen H , Matheis P , et al . Age- and gender-related normal left ventricular deformation assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking . J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015. ; 17 ( 1 ): 25 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moons KG , Altman DG , Reitsma JB , et al . Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration . Ann Intern Med 2015. ; 162 ( 1 ): W1 – W73 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lehrke S , Lossnitzer D , Schöb M , et al . Use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance for risk stratification in chronic heart failure: prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy . Heart 2011. ; 97 ( 9 ): 727 – 732 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Assomull RG , Prasad SK , Lyne J , et al . Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy . J Am Coll Cardiol 2006. ; 48 ( 10 ): 1977 – 1985 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Di Marco A , Anguera I , Schmitt M , et al . Late gadolinium enhancement and the risk for ventricular arrhythmias or sudden death in dilated cardiomyopathy: systematic review and meta-analysis . JACC Heart Fail 2017. ; 5 ( 1 ): 28 – 38 . [Published correction appears in JACC Heart Fail 2017;5(4):316.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kalam K , Otahal P , Marwick TH . Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction . Heart 2014. ; 100 ( 21 ): 1673 – 1680 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He J , Yang W , Wu W , et al . Early diastolic longitudinal strain rate at MRI and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction . Radiology 2021. ; 301 ( 3 ): 582 – 592 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mignot A , Donal E , Zaroui A , et al . Global longitudinal strain as a major predictor of cardiac events in patients with depressed left ventricular function: a multicenter study . J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010. ; 23 ( 10 ): 1019 – 1024 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sengeløv M , Jørgensen PG , Jensen JS , et al . Global longitudinal strain is a superior predictor of all-cause mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction . JACC Cardiovasc Imaging . 2015. ; 8 ( 12 ): 1351 – 1359 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chimura M , Onishi T , Tsukishiro Y , et al . Longitudinal strain combined with delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance improves risk stratification in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy . Heart 2017. ; 103 ( 9 ): 679 – 686 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Piepoli M . Diagnostic and prognostic indicators in chronic heart failure . Eur Heart J 1999. ; 20 ( 19 ): 1367 – 1369 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gulati A , Ismail TF , Jabbour A , et al . Clinical utility and prognostic value of left atrial volume assessment by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy . Eur J Heart Fail 2013. ; 15 ( 6 ): 660 – 670 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]