Key Teaching Points.

-

•

Conduction system pacing with left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) is emerging as an alternative strategy to traditional coronary sinus pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Low and stable long-term thresholds make LBBAP an excellent option for physiologic pacing.

-

•

Long-term safety profile, lead integrity, lead-to-lead interaction, and risk of extraction of LBBAP leads need to be determined. LBBAP lead is well-anchored, deep into the interventricular septum, which increases the risk of lead-lead interaction from constant friction when placed near a defibrillator lead.

-

•

We report the first case of LBBAP lead failure due to interaction with a defibrillator lead. Adequate distance between the defibrillator lead and the LBBAP lead insertion site needs to be maintained at the time of implantation to avoid lead-lead interaction and potential lead failure.

Introduction

Atrioventricular (AV) node ablation and conduction system pacing using left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) is an excellent option for patients with atrial fibrillation and rapid ventricular rates refractory to medical therapy.1,2 Patients with severely reduced left ventricular systolic function benefit from implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for prevention of sudden cardiac death.3 Biventricular pacing using coronary vein lead has been shown to reduce heart failure hospitalization and mortality compared to right ventricular pacing in patients undergoing AV node ablation,4 but may be limited by anatomical challenges, nonphysiologic biventricular activation, phrenic nerve stimulation, and/or high pacing thresholds. Although His bundle pacing is an excellent option in these patients, it can be technically challenging and be associated with unexpected late threshold rise.5 In addition to better sensing, lower and more stable long-term thresholds are an advantage with LBBAP compared to His bundle pacing.6, 7, 8 Although LBBAP has been shown to be safe in multiple observational studies, concern regarding the long-term integrity of the LBBAP lead remains owing to a significant portion of the lead being buried deep in the interventricular septum. We report a case of LBBAP lead failure due to interaction with the defibrillator lead near the septal insertion site.

Case report

A 68-year-old man with hypertension, atrial fibrillation refractory to medical therapy and multiple ablations, and nonischemic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular ejection fraction of 25%–30% was referred for AV node ablation. He underwent AV node ablation and uncomplicated biventricular ICD placement using a 3830 SelectSecure® lead for LBBAP (LV port), Sprint Quattro® ICD lead in right ventricular apical septum, and 5076 CapSureFix® Novus lead (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN) in the right atrial appendage. First, the His region was identified using a double curved His delivery sheath (C315 Sheath) guided by local electrocardiogram, His capture, and fluoroscopy. The system, lead and sheath, was then advanced approximately about 2 cm distally toward the right ventricular apex and rotated counterclockwise to maintain perpendicular orientation to the septum. At this point, the lead was advanced into the septum with rapid clockwise rotations while monitoring for triggered ventricular beats, changes in impedance, current of injury, and local electrocardiogram amplitude and injury. The rotations were repeated until LBBAP was confirmed. The LBBAP lead demonstrated anodal capture threshold at 3 V and nonselective left bundle capture at 0.5 V at 0.4 ms. The device was programmed to pace from LBBAP lead and right ventricular lead with left ventricle–right ventricle delay of 80 ms. The patient lacked adequate internet coverage and refused remote monitoring. He had regular follow-up in the device clinic and cardiology clinic. On follow-up, he noted improvement in exercise capacity with improvement in NYHA functional class from III to II. A remarkable improvement was noted in left ventricular ejection fraction from 25%–30% at baseline to 49% at 12-month follow-up.

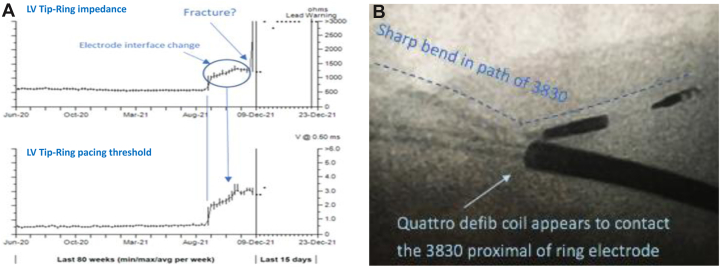

Twenty months after implant, he was seen in the heart failure clinic for dyspnea on exertion and fatigue. Acute rise in impedance and threshold with loss of capture of LBBAP lead was recorded on device check (Figure 1A), suggestive of lead fracture. Both the right ventricular defibrillator and atrial leads showed stable threshold and impedance (pacing and shocking) parameters. The patient was scheduled for LBBAP lead extraction and implantation of a new LBBAP lead. Preprocedural cinefluoroscopy of the system (Supplemental Video 1) revealed lead-lead interaction with the defibrillator coil sliding against the LBBAP lead near the ring electrode. Fluoroscopic images (Figure 1B) showed a sharp bend in the 3830 SelectSecure lead where the defibrillator coil appears to make contact. The LBBAP lead was easily extracted with manual traction and a new 3830 SelectSecure lead was placed deep in the mid septum away from the defibrillator coil with nonselective left bundle branch capture threshold of 0.6 V @ 0.4 ms. The patient tolerated the procedure well, without any complications.

Figure 1.

Impedance and threshold trend. A: Impedance and threshold rise in 3830 SelectSecure lead (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN), followed by open circuit and loss of capture. B: Fluoroscopic image demonstrating the defibrillator lead coil in contact with the proximal end of the ring electrode of 3830 SelectSecure lead. A sharp bend in the 3830 SelectSecure lead is seen where the defibrillator lead coil appears to make contact.

Gross inspection of the extracted LBBAP lead showed a break in insulation and conductor where the lead was in contact with the defibrillator coil (Figure 2A). Detailed analysis of the lead showed wear and tear through the outer insulation, outer coil, ethylene-tetrafluoroethylene on the tip conductor, and the tip conductor (Figure 2B). The source of the lead abrasion was determined to be the defibrillator coil. A longitudinal and 3-dimensional schematic (Figure 2C) of the SelectSecure lead provides a reference to compare the damage on the various components of the lead.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic image of the lead fracture. A: Apparent visible wear and tear on the 3830 SelectSecure lead (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN) after explanation. B: Wear through the outer insulation, outer coil, ethylene-tetrafluoroethylene on the tip conductor, and the tip conductor. C: Longitudinal and 3-dimensional schematic of the 3830 SelectSecure lead. (Images used with permission from Medtronic, plc © 2022.)

The patient reported significant improvement in functional status (NYHA II from NYHA III) on postimplant follow-up at 3 months. Repeat echocardiogram showed normalization of ejection fraction.

Discussion

The 3830 SelectSecure lead consists of a platinum/iridium ring electrode connected to an outer coil conductor, and ethylene-tetrafluoroethylene jacketed cable tip conductor, silicone inner insulation tubing, and polyurethane outer insulation tubing. It is a coaxial, bipolar, steroid-eluting, lumenless, fixed-screw pacing lead approved for selective site pacing and His bundle pacing. No cases of intracardiac lead failure due to lead-lead interaction of this lead have been reported so far.9 To our knowledge, this is the first report of 3830 SelectSecure lead failure due to intracardiac lead-to-lead interaction when used for conduction system pacing. The LBBAP lead in the initial implantation was located more posteriorly (Figure 3A), with the lead body proximal to the ring electrode coming in close contact with the defibrillator lead coil (Figure 1B). The septum likely acted as a fulcrum for the LBBAP lead and with cardiac motion, the lead body continuously rubbed against the defibrillator lead coil, resulting in progressive abrasion and ultimately lead failure. We hypothesize the effective area of the insulation breach was not large enough to cause a measurable drop in impedance before the rise in impedance owing to lead failure from interaction.

Figure 3.

Chest radiography and electrocardiogram of initial and final lead position. A: Chest radiograph showing the posterior location of the left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) lead after initial implantation with proximity of the ring electrode to the defibrillator lead coil. B: Chest radiograph showing a more anterior location of the LBBAP lead after reimplantation with adequate distance from the defibrillator lead. C: Pacing morphology of initial implant with anodal capture and nonselective left septal capture. D: Pacing morphology of new implant with anodal capture and nonselective left bundle selective capture.

The challenges of extracting the LBBAP lead in the deep septal location are currently unknown. It is unclear if extensive fibrosis will occur in this location along the length of the tip and the ring electrode intraseptally and around the insertion site, during long-term follow-up. In our case, the LBBAP lead was only 20 months old and was easily extracted with gentle traction. There was no significant fibrosis at the lead tip or insertion site. Reimplantation of a new LBBAP lead was done at a more anterior part of the septum (Figure 3B) to maintain adequate distance between the hinge point of the LBBAP lead and the ICD lead coil. Our case report highlights the possible risk of lead-lead interaction of the LBBAP lead with the defibrillator lead. Care should be taken to maintain adequate distance between the hinge-point of the LBBAP lead and the defibrillator coil.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures: Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman reports being a speaker and consultant for, and receiving research and fellowship support from, Medtronic; being a consultant for Abbott, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and patent for an HBP delivery tool. Parash Pokharel and Ankit Mahajan report no conflict of interests.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrcr.2022.10.007.

Supplementary Data

Cinefluoroscopy showing the defibrillator lead coil sliding against 3830 SelectSecureR lead near the implant site.

References

- 1.Zhang J., Wang Z., Cheng L., et al. Immediate clinical outcomes of left bundle branch area pacing vs conventional right ventricular pacing. Clin Cardiol. 2019;42:768–773. doi: 10.1002/clc.23215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijayaraman P., Mathew A.J., Naperkowski A., et al. Conduction system pacing versus conventional pacing in patients undergoing atrioventricular node ablation: non-randomized, on-treatment comparison. Heart Rhythm O2. 2022;3:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Khatib S.M., Stevenson W.G., Ackerman M.J., et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:e91–e220. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brignole M., Pentimalli F., Palmisano P., et al. AV junction ablation and cardiac resynchronization for patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and narrow QRS: the APAF-CRT mortality trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4731–4739. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beer D., Subzposh F.A., Colburn S., Naperkowski A., Vijayaraman P. His bundle pacing capture threshold stability during long-term follow-up and correlation with lead slack. Europace. 2020;23:757–766. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijayaraman P., Ponnusamy S., Cano Ó., et al. Left bundle branch area pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy: results from the International LBBAP Collaborative Study Group. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma P.S., Patel N.R., Ravi V., et al. Clinical outcomes of left bundle branch area pacing compared to right ventricular pacing: results from the Geisinger-Rush Conduction System Pacing Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu S., Su L., Vijayaraman P., et al. Left bundle branch pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy: nonrandomized on-treatment comparison with His bundle pacing and biventricular pacing. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barakat A.F., Inashvili A., Alkukhun L., et al. Use trends and adverse reports of SelectSecure 3830 lead implantations in the United States. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cinefluoroscopy showing the defibrillator lead coil sliding against 3830 SelectSecureR lead near the implant site.