Abstract

Progesterone receptor (PR) is expressed in a wide variety of human tissues, including both reproductive and non-reproductive tissues. Upon binding to the PR, progesterone can display several non-reproductive functions, including neurosteroid activity in the central nervous system, inhibition of smooth muscle contractile activity in the gastrointestinal tract, and regulating the development and maturation of the lung. PR exists as two major isoforms, PRA and PRB. Differential expression of these PR isoforms reportedly contributes to different biological activities of the hormone. However, the distribution of the PR isoforms in human tissues has remained virtually unexplored.

In this study, we immunolocalized PR expression in various human tissues using PR (1294) specific antibody, which is capable of detecting both PRA and PRB, and PRB (250H11) specific antibody. Tissues from the uterus, ovary, breast, placenta, prostate, testis, cerebrum, cerebellum, pituitary, spinal cord, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, pancreas, liver, kidney, urinary bladder, lung, heart, aorta, thymus, adrenal gland, thyroid, spleen, skin, and bone were examined in four different age groups (fetal, pediatric, young, and old) in male and female subjects. PR and PRB were detected in the nuclei of cells in the female reproductive system, in both the nuclei and cytoplasm of pituitary gland and pancreatic acinar cells, and only in the cytoplasm of cells in the testis, stomach, small intestine, colon, liver, kidney, urinary bladder, lung, adrenal gland, and skin. Of particular interest, total PRB expression overlapped with that of total PR expression in most tissues but was negative in the female fetal reproductive system. The findings indicate that progesterone could affect diverse human organs differently than from reproductive organs. These findings provide new insights into the novel biological roles of progesterone in non-reproductive organs.

Keywords: progesterone receptor, progesterone receptor isoform B, systemic distribution, human tissues

1. Introduction

The estrogen and progesterone sex steroids and their receptors have important roles in several organs and tissues. Progesterone has important functional roles in female reproductive organs. In particular, progesterone is required for the differentiation and maturation of endometrium [1-4], mediating luteinizing hormone (LH) dependent ovulation in the ovary [5], and ductal elongation and side branching in mammary glands [6]. Of particular interest, progesterone also acts as a neurosteroid and has important roles in the human nervous systems, including apoptosis, dendritic spine remodeling, neural pruning, and myelination of the central nervous system (CNS) [7-9]. In the CNS, progesterone induces anti-apoptotic cell survival pathways and bioenergetic reactions, such as increased glucose transport to cells, adenosine triphosphate production in mitochondria, and transcription of mRNA [10]. In addition, progesterone induces neural cell proliferation [11], regulates myelination [12], and promotes the proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells through progesterone-induced intracellular signaling and transcription in the myelin synthesis pathways [13-15]. In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, sex steroid hormones are reportedly involved in various functions, such as gastric emptying, GI transit, and smooth muscle contraction, which decrease during pregnancy [16]. In the pancreas, treatment with progesterone stimulates the proliferation of alpha and beta cells in pancreatic islets [17]. In the liver, progesterone also influences lipid metabolism by stimulating the clearance of very low density lipoprotein [18]. In the respiratory system, sex steroids have been demonstrated to play important roles in the development and maturation of lungs, and maintenance of normal lung function. Progesterone treatment reportedly increases mRNA encoding rat epithelial Na channel (rENaC) alpha and gamma subunits, which are crucial in reabsorbing alveolar fluid [19], as well as increasing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and surfactant proteins (SP)-B and –C [20], which both are markers of lung maturation [21] and increasing tidal volume. Progesterone treatment also decreases arterial PCO2 and enhances the ventilatory response to CO2 inhalation [22].

Several reports have demonstrated that sex steroids function in various organs in addition to the reproductive system, CNS, GI tract, and lungs through the differential expression of specific isoforms. In the reproductive system and CNS, estrogen receptor isoforms have been relatively well studied [23], while PR isoforms have not. PR has two main isoforms, PRA and PRB. PRA is 164 amino acids in length and is truncated at the N-terminus as compared to the full-length PRB [24]. The isoforms have different conformation and interact with different partners with distinct properties [25, 26]. PRB is distributed equally in cytoplasm and nuclei of cells, with distinctive extra-nuclear signaling. PRA is localized predominantly in the nuclei of cells with no extra-nuclear signaling [27, 28]. In the present study, we used antibody specific to the PRB isoform (PRB-250H11) [29] and antibody that recognizes both PRA and PRB (PR-1294) [30]. In contrast to previously reported PR isoform-specific antibodies, the PRB-specific 250H11 antibody conferred PRB specificity and immunoreactivity in 10% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue specimens without the need for blocking peptides [31-33]. This novel 250H11 antibody allowed us to analyze PRB and total PR immunolocalization in various tissues from different age groups to better understand the systemic biological actions of progesterone in human tissues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tissues and Subjects

Data of more than 1000 autopsy cases at Tohoku University Hospital, Sendai, Japan from 2005 to 2018 were analyzed. Cases of sudden death without history of apparent severe pathology were selected for this study. The 38 cases were all Japanese. Tissue sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin to evaluate whether there were any pathological findings and to assess the suitability of the tissues for further immunohistochemical study. Since organs could not be obtained from the autopsy cases, we used normal areas of surgically resected specimens. The 38 subjects were all Japanese. The 151 normal or non-pathological tissues did not harbor any significant histopathological abnormalities. These cases were tentatively classified into four different age groups. Six cases (35 tissues) were fetal (19 to 41 weeks prenatal), 12 cases (39 tissues) were pediatric (0 to 10 years old), 9 cases (39 tissues) were young age (21 to 42 years old), and 11 cases (38 tissues) were classified as old age (54 to 79 years old). The organs examined included uterus, ovary, breast, placenta, prostate, testis, cerebrum, cerebellum, pituitary, spinal cord, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, pancreas, liver, kidney, urinary bladder, lung, heart, aorta, thymus, adrenal gland, thyroid, spleen, skin, and bone. Each organ consisted of at least one tissue from each of the four age groups and were obtained from male and/or female subjects. The Ethics Committees of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine approved the protocol of this study.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Progesterone receptor (PR) and PRB immunostaining were performed as previously reported (60). Briefly, immunostaining was performed using a streptavidin-biotin amplification method employing the Histofine Staining Kit (Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan). Ten percent formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned (3 μm thickness) and mounted on 3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane coated slides (Matsunami Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The glass slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in alcohol, treated with citrate buffer (2 mM citric acid and 9 mM trisodium citrate dihydrate, pH 6.0), and autoclaved at 121°C for 5 min for antigen retrieval. Rabbit blocking solution (Nichirei Bioscience) was applied and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Primary antibodies recognizing PR/PRB (1294 PR, a specific mouse monoclonal antibody) [29] or PRB (250H11 PRB-specific mouse monoclonal antibody [mAb]) [30] were incubated at 4°C overnight. The reacted slides were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Nichirei Bioscience) for 30 min at room temperature. 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride solution (1 mM DAB, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.6, and 0.006% H2O2) was used to visualize antigen-antibody complexes with hematoxylin as a counterstain. We employed double immunostaining with DAB for LH (Novocastra, Japan), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH; DAKO, Japan) and prolactin (PRL; DAKO, Japan), and Vector-blue for PR and PRB. PR and PRB positive breast carcinoma tissues were used as a positive control for both antibodies (PR, 1294 and PRB, 250H11 mAb). Mouse immunoglobulin (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark; ref. No. X0936) was used as a negative control. No specific immunoreactivity was detected in the control slides.

2.3. Evaluation of immunoreactivity

Each organ was individually evaluated among different tissue structures and cell types. Immunoreactivity was evaluated using the modified histological score (H-score) by two of the authors (T.A. and R.S.) in an independent fashion [34]. A semi-quantitative analysis was used to determine the status of intra and extra-nuclear immunoreactivity. Positive cells were counted in estimated percentage: 0%, <1%, 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%. Relative immunointensity was tentatively classified into three different levels: 0 = negative, 1 = weak, and 2 = strong. The percentage and the relative immunointensity of positive cells were added to calculate the total score.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro software version 13.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) [35]. One-way ANOVA method was used for statistical analysis to evaluate the correlation between gender and age range based on the H-score immunoreactivity of PR and PRB. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05 using a two-sided test in this study.

3. Results

3.1. PR and PRB distribution in general organs

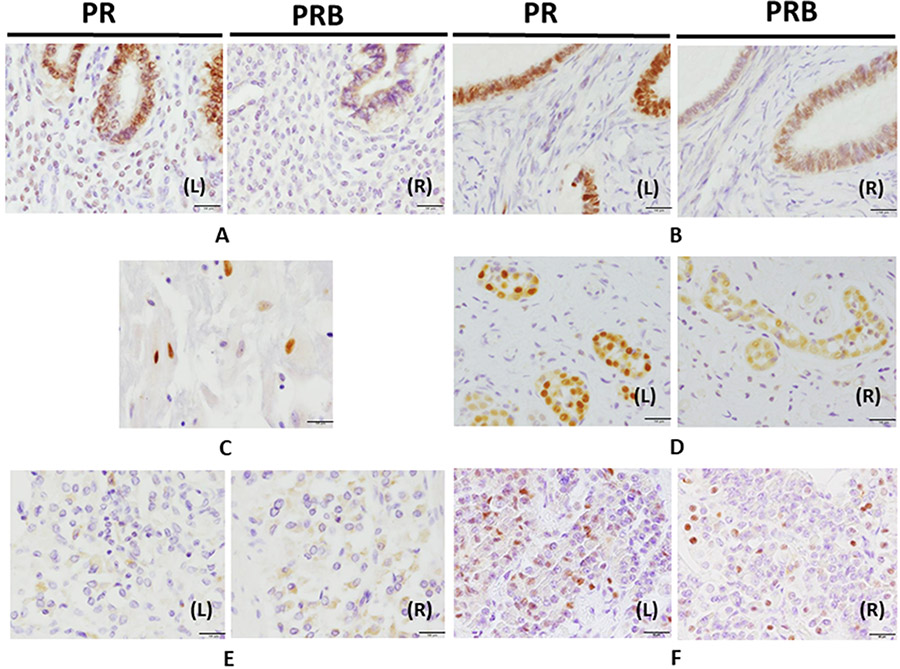

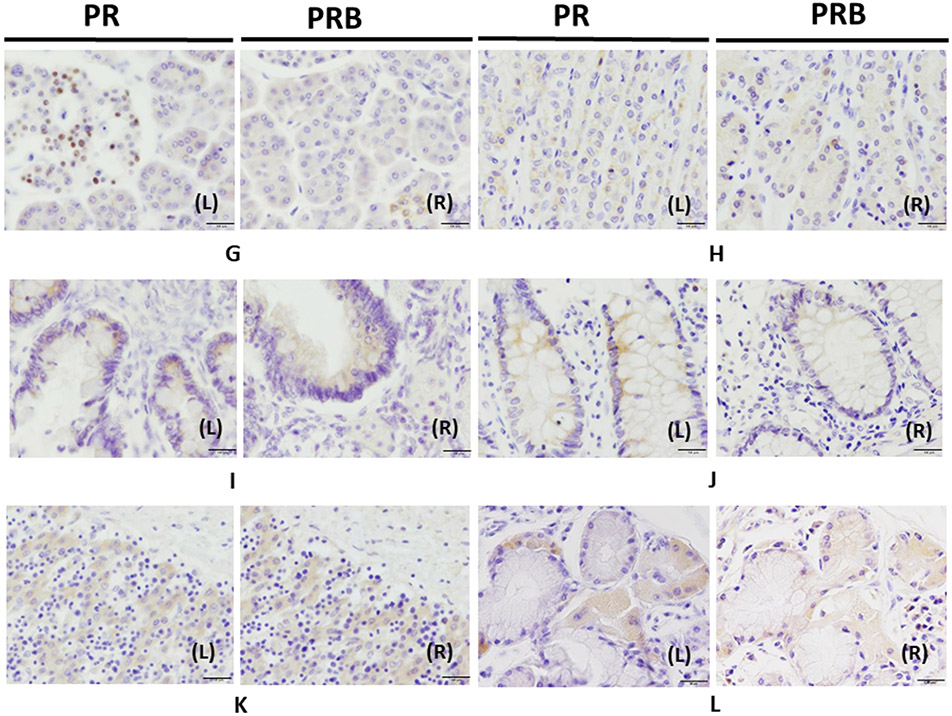

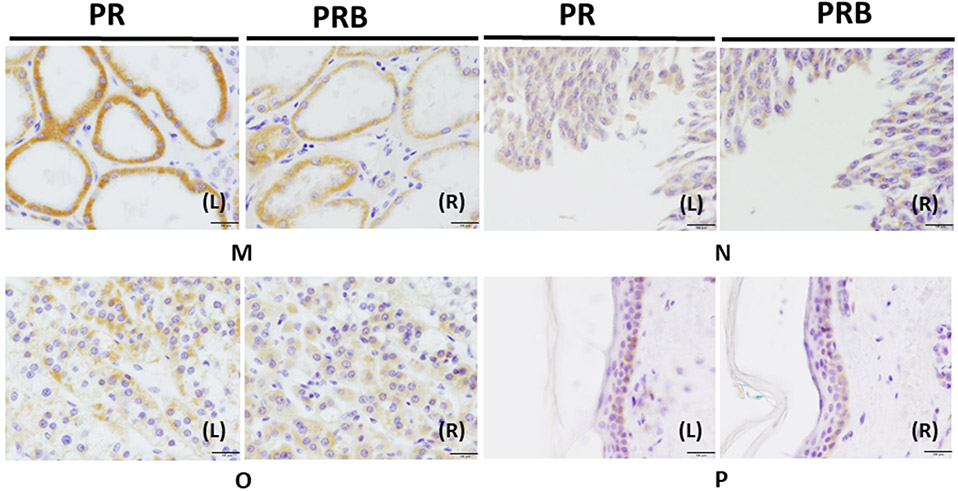

Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. In the reproductive system, both PR and PRB immunoreactivity was detected in the nucleus and cytoplasm, while immunoreactivity was detected only in the cytoplasm in other systems, except for some endocrine organs such as pituitary and pancreas (Table 1, Fig. 1A-E). In the female reproductive system, nuclear immunoreactivity of both PR and PRB was detected in endometrial epithelial cells (Fig. 1AL and R) as well as epithelial cells and granular cells of the ovary (Fig. 1BL and R) and fallopian tubal epithelial cells. Cytotrophoblasts demonstrated only nuclear PR immunoreactivity with little or no PRB immunoreactivity in the placenta (Fig. 1C). Ductal cells of mammary glands displayed both PR and PRB nucleus immunoreactivity (Fig. 1D).

Table 1.

Summary of PR and PRB distribution in human tissues

| Organs | Cell type | Cell localization |

|---|---|---|

| Uterus | Endometrial epithelial cells, endometrial stroma cells* | Nucleus |

| Ovary | Epithelial cells, granular cells, fallopian tube epithelium, luteinizing cells* | Nucleus |

| Breast | Ductal cells of mammary glands | Nucleus |

| Placenta | Cytotrophoblasts* | Nucleus |

| Pituitary | Endocrine cells of the anterior lobe | Nucleus and cytoplasm |

| Pancreas | Islet of Langerhans and acinar cells | Nucleus and cytoplasm |

| Stomach | Epithelial cells of fundic gland | Cytoplasm |

| Small intestine | Epithelial cells in the crypt | Cytoplasm |

| Colon | Epithelial cells in the crypt | Cytoplasm |

| Liver | Hepatocyte around central and portal vein | Cytoplasm |

| Kidney | Proximal and distal tubules | Cytoplasm |

| Urinary bladder | Urothelial epithelial cells | Cytoplasm |

| Testis | Leydig cells, epithelial cell of the epididymis | Cytoplasm |

| Lung | Submucosal glandular cells in the bronchus | Cytoplasm |

| Adrenal gland | Cortex (ZG ZF ZR) and medulla | Cytoplasm |

| Skin | Keratinocyte of the basal site of the epidermis | Cytoplasm |

= cell type that has little to no PRB expression

Table 2.

H-score summary of PR and PRB positivity in human tissues in each sex and range of age fetal cases (19 to 41 weeks prenatal), pediatric cases (0 to 10 years old), young cases (21 to 42 years old), and old cases (54 to 79 years old)

| Range of age | Fetal | Pediatric | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||

| Antibody | PR | PRB | PR | PRB | PR | PRB | PR | PRB |

| Pituitary (endocrine cells in anterior lobe) | None | None | None | None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| lung (bronchus submucosal gland) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Esophagus | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Stomach (fundic gland epithelial cells) | 5 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 60 | 60 |

| Small intestine (epithilial cell in crypt) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Colon (epithilial cell in crypt) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | 30 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| Pancreas (islet of Langerhans) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | 30 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| (acinar cells) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | 10 | 5 | 35 | 20 |

| Liver (central and portal vein) | Neg | Neg | 5 | 2 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Kidney (proximal and distal tubules) | 35 | 35 | 30 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 15 | 5 |

| Urinary bladder (epithelial cells) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | 5 | 5 | 40 | 10 |

| Adrenal gland (zona glomerulosa) | None | None | None | None | 1 | 1 | 30 | 10 |

| (zona fasciculata) | None | None | None | None | 90 | 30 | 90 | 80 |

| (zona reticularis) | None | None | None | None | 90 | 40 | 90 | 80 |

| (medulla) | None | None | None | None | 5 | 1 | 10 | 5 |

| Skin (keratinocye in epidermis) | None | None | None | None | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Testis (leydig cells) | 50 | 10 | None | None | Neg | Neg | None | None |

| (epithelial cell of epididymis) | Neg | Neg | None | None | Neg | Neg | None | None |

| Prostate | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Uterus (endometrial epithelial cells) | None | None | 30 | Neg | None | None | 50 | 50 |

| (endomtrial stromal cells) | None | None | 10 | <1 | None | None | 60 | <1 |

| Ovary (epithelial cells) | None | None | 10 | 1 | None | None | 20 | 5 |

| (glanular cells) | None | None | 40 | 40 | None | None | None | None |

| Range of age | Young | Old | ||||||

| Sex | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||

| Antibody | PR | PRB | PR | PRB | PR | PRB | PR | PRB |

| Pituitary (endocrine cells in anterior lobe) | 10 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 10 | 5 |

| lung (bronchus submucosal gland) | Neg | Neg | 30 | 10 | 50 | 30 | 20 | 20 |

| Esophagus | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Stomach (fundic gland epithelial cells) | 10 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 20 | 5 | 70 | 50 |

| Small intestine (epithilial cell in crypt) | 10 | 5 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Colon (epithilial cell in crypt) | Neg | Neg | 5 | 1 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 10 |

| Pancreas (islet of langerhans) | 30 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 20 | 10 | 40 | 1 |

| (acinar cells) | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| Liver (central and portal vein) | 30 | 5 | 50 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 20 | 20 |

| Kidney (proximal and distal tubules) | 70 | 40 | 70 | 50 | 80 | 30 | 40 | 20 |

| Urinary bladder (epithelial cells) | 5 | 1 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Adrenal gland (zona glomerulosa) | 50 | 50 | 80 | 80 | 10 | 5 | 80 | 80 |

| (zona fasciculata) | 90 | 70 | 90 | 90 | 60 | 40 | 90 | 90 |

| (zona reticularis) | 90 | 70 | 90 | 90 | 60 | 50 | 90 | 90 |

| (medulla) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Skin (keratinocye in epidermis) | 1 | Neg | Neg | Neg | 1 | 1 | 10 | 10 |

| Testis (leydig cells) | 40 | 30 | None | None | 50 | 40 | None | None |

| (epithelial cell of epididymis) | 1 | 1 | None | None | 70 | 5 | None | None |

| Prostate | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| Uterus (endometrial epithelial cells) | None | None | 90 | 1 | None | None | 1 | 1 |

| (endometrial stroma cells) | None | None | 40 | <1 | None | None | 30 | <1 |

| Ovary (epithelial cells) | None | None | 50 | 20 | None | None | 40 | 1 |

| (glanular cells) | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| (lutenizing cells) | None | None | 5 | <1 | None | None | None | None |

| (Fallopian tube epithelium) | None | None | 80 | 20 | None | None | 30 | 20 |

| Placenta (cytotophoblast) | None | None | 5 | <1 | None | None | None | None |

| Breast (ductal cells) | None | None | 50 | 1 | None | None | 70 | 30 |

Mark: None = no cases, Neg = negative for PR or PRB

Figure 1. Immunohistochemistry of PR and PRB in human organs.

Panels AL (left) and R (right), uterus was immunostained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels BL and R, the ovary. Panels C, the placenta. Panels DL and R, the breast was stained with PR and PRB staining. Panels EL and R, testis was stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels FL and R, the pituitary was stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels GL and R, the pancreas was stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels HL and R, the stomach was stained with PR and PRB staining, respectively. Panels IL and R, the small intestine was stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels JL and R, the colon was stained with PR and PRB staining, respectively. Panels KL and R, the liver was stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels LL and R lung were stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels ML and R, the kidney were stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels NL and R, the urinary bladder was stained with PR and PRB staining, respectively. Panels OL and R, the adrenal gland was stained with PR and PRB, respectively. Panels PL and R, the skin was stained with PR and PRB staining, respectively (magnification 400x) Bar: 50 μm.

In the male reproductive system, both PR and PRB immunolocalized in the cytoplasm of Leydig cells and epithelial cells of the testis epididymis (Fig. 1EL and R). There was no PR and PRB immunoreactivity detected in the prostate.

In the CNS, PR and PRB nuclear immunoreactivity were detected in endocrine cells of anterior lobe in the pituitary gland (Fig. 1FL and R). These PR positive cells were correlated with positive reactions for LH and PRL, but not FSH positive cells (Fig. S1). Neither PR and PRB were detected in the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

In the GI system, fundic gland epithelial cells of the stomach and epithelial cells in the crypt of both small intestine and colon demonstrated PR and PRB cytoplasmic immunoreactivity (Fig. 1H-J). In addition, acinar cells of the pancreas also demonstrated PR and PRB cytoplasmic immunoreactivity. Cells of the Langerhans islet in the pancreas nearly always demonstrated only PR nuclear immunoreactivity (Fig. 1GL and R). In the liver, hepatocytes around the central and portal vein had cytoplasmic PR and PRB immunoreactivity (Fig. 1KL and R).

The particular findings in other systems are described below. First, epithelial cells of proximal and distal tubules of the kidney (Fig. 1ML and R) and bladder urothelial epithelial cells (Fig. 1NL and R) demonstrated PR and PRB cytoplasmic immunoreactivity. In the respiratory tract, PR and PRB cytoplasmic immunoreactivity were also detected in submucosal glandular cells in the bronchus (Fig. 1LL and R). In the adrenal gland, both PR and PRB immunoreactivity was detected in the zona glomerulosa, zona fasiculata, zona reticularis, and medulla. PR and PRB displayed more cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in the zona fasiculata and reticularis than in the zona glomerulosa and medulla (Fig. 1OL and R). The skin also demonstrated cytoplasmic staining in both PR and PRB in keratinocytes of the basal site of the epidermis (Fig. 1PL and R).

In summary, immunopositivity of both PR and PRB in nuclei of cells was detected only in the female reproductive tissues. Both nuclear and cytoplasmic PR and PRB immunoreactivity were detected in the pituitary gland and pancreatic acinar cells. Cytoplasmic PR and PRB immunoreactivity were detected only in testis, stomach, small intestine, colon, liver, kidney, urinary bladder, lung, adrenal gland, and skin.

3.2. Statistical analysis of the comparison between PR and PRB H-score with genders and age groups

The statistically significant difference of PR or PRB H-scores between male and female subjects was observed only in the colon, in which colon tissues of males displayed significantly higher PR H-scores than those of females (Table 3). Among the age groups, in the pituitary gland and renal epithelial cells, PR H-score was significantly higher in the young and old groups (21-79 years old) than in the fetal and pediatric groups (prenatal 19 weeks to 10 years old) (Table 3). PR H-scores in adrenal medulla cells of the fetal and pediatric groups were significantly higher than that of the young and old groups (Table 3). No statistical differences between different age groups and PRB H-score were evident.

Table 3.

Association between H-score of PR and PRB with sex and age of human PR/PRB positive organs

| Organs | Clinical variables/ Categories |

PR H-s core | P-value | PRB H-score | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pituitary (endocrine cells in anterior lobe) | Sex Male | 5±6 | 0.974 | 3±3 | 0.789 |

| Female | 5±4 | 2±2 | |||

| Age Junior | 1±0 | 0.042* | 1±0 | 0.219 | |

| Senior | 8±3 | 4±2 | |||

| lung (bronchus submucosal gland) | Sex Male | 50±. | 0.212 | 30±. | 0.333 |

| Female | 25±7 | 15±7 | |||

| Age Junior | . | . | . | . | |

| Senior | 33±15 | 20±10 | |||

| Stomach (fundic gland) | Sex Male | 14±9 | 0.232 | 27±30 | 0.215 |

| Female | 32±10 | 6±3 | |||

| Age Junior | 28±23 | 0.360 | 24±25 | 0.233 | |

| Senior | 13±6 | 4±2 | |||

| Small intestine (crypt) | Sex Male | . | . | . | . |

| Female | . | . | |||

| Age Junior | . | . | . | . | |

| Senior | . | . | |||

| Colon (crypt) | Sex Male | 30±0 | 0.049* | 20±0 | 0.044* |

| Female | 12±8 | 7±5 | |||

| Age Junior | 20±9 | 0.898 | 15±7 | 0.601 | |

| Senior | 18±8 | 10±10 | |||

| Pancreas (islet of Langerhans) | Sex Male | 27±6 | 0.823 | 4±5 | 0.374 |

| Female | 30±26 | 1±0 | |||

| Age Junior | 16±21 | 0.212 | 1±0 | 0.542 | |

| Senior | 35±13 | 3±5 | |||

| (acinar cells) | Sex Male | 5±5 | 0.305 | 4±2 | 0.288 |

| Female | 17±16 | 10±9 | |||

| Age Junior | 23±18 | 0.101 | 13±11 | 0.153 | |

| Senior | 5±4 | 4±2 | |||

| Liver (central and portal vein) | Sex Male | 20±14 | 0.806 | 5±0 | 0.461 |

| Female | 25±23 | 11±9 | |||

| Age Junior | 5±. | 0.324 | 2±. | 0.386 | |

| Senior | 28±17 | 10±7 | |||

| Kidney (proximal and distal tubules) | Sex Male | 48±34 | 0.687 | 27±17 | 0.653 |

| Female | 39±23 | 20±21 | |||

| Age Junior | 21±14 | 0.008* | 12±16 | 0.061 | |

| Senior | 65±17 | 35±13 | |||

| Urinary bladder (epithelium) | Sex Male | 5±0 | . | 3±3 | 0.293 |

| Female | 40±. | 10±. | |||

| Age Junior | 23±25 | 0.667 | 8±4 | 0.374 | |

| Senior | 5±. | 1±. | |||

| Adrenal gland (zona glomerulosa) | Sex Male | 20±26 | 0.128 | 19±27 | 0.809 |

| Female | 63±29 | 10±. | |||

| Age Junior | 16±21 | 0.209 | 6±6 | 0.439 | |

| Senior | 55±33 | 28±32 | |||

| (zona fasciculata) | Sex Male | 80±17 | 0.374 | 47±21 | 0.300 |

| Female | 90±0 | 80±. | |||

| Age Junior | 90±0 | 0.542 | 55±35 | 1.000 | |

| Senior | 83±15 | 55±21 | |||

| (zona reticularis) | Sex Male | 80±17 | 0.374 | 53±15 | 0.270 |

| Female | 90±0 | 80±. | |||

| Age Junior | 90±0 | 0.542 | 60±28 | 1.000 | |

| Senior | 83±15 | 60±14 | |||

| (Medulla) | Sex Male | 2±2 | 0.638 | 1±0 | |

| Female | 4±5 | 5±. | |||

| Age Junior | 8±4 | 0.013* | 3±3 | 0.423 | |

| Senior | 1±0 | 1±0 | |||

| Skin (epidermis) | Sex Male | 2±3 | 0.410 | 1±1 | 0.401 |

| Female | 5±5 | 4±6 | |||

| Age Junior | 5±0 | 0.570 | 1±0 | 0.656 | |

| Senior | 3±5 | 3±5 |

To summarize, the colon yielded significantly different PR and PRB H-score between genders. However, in the pituitary gland, kidney, and medulla of the adrenal gland, significantly different in PR H-score was evident between age groups.

4. Discussion

PR has been reported in several human organs, including both reproductive and non-reproductive tissues [36-39]. However, PR isoforms (PRA and PRB) regulate cells in different manners [25, 26]. Therefore, it is necessary to study the distribution of these PR subtypes to evaluate the biological significance of progesterone activity in humans, especially in non-reproductive organs.

This is the first study to demonstrate the distribution of PR and PRB in the human body, and to reveal differences between males and females and among different age groups in a systemic fashion. We focused on two main antibodies, PR/PRB (1294 PR, a specific mouse monoclonal antibody) or PRB (250H11 PRB-specific mouse monoclonal antibody), to distinguish between PR and PRB immunoreactivity. PR 1294 antibody detect both PRA and PRB, while PRB 250H11 specific antibody detected only PRB. These antibodies have been well-validated and the sources and batch information for both antibodies were previously reported in the literature [29, 30]. The present results demonstrate the temporal, spatial, and gender-specific patterns of PR and PRB according to specific types of the cells in individual organs. Of particular interest, PR and PRB immunoreactivity was predominantly detected in the cytoplasm, except for the cells in the female reproductive system, islet cells in the pancreas, and endocrine cells of the pituitary, in which both PR and PRB immunoreactivity was predominantly detected in cell nuclei (Table 1). Therefore, in these cells, progesterone activity likely occurs predominantly through the nuclear signaling pathway [25]. However, in the GI and urogenital systems, progesterone likely acts predominantly through the extra-nuclear signaling pathway [40], although details of extra-nuclear signaling pathways in the aforementioned organs have remained virtually unknown. Prior results also indicated the potential cross-talk between nuclear and non-nuclear signaling of PR in reproductive tissues [41]. For instance, in the female mammalian reproductive system, the status of membrane-localized progestin/PR (mPR) was correlated with cumulus cell expansion in the ovary and the expression in ciliated cells; and mPR regulated the oocyte transportation from the ovary to the uterus, preparation of implantation in uterus, and up-regulated the transcriptional activity of nuclear PR in myometrium cells [42-47]. In the male mammalian reproductive system, mPR was also reported to induce the hyper-motility of sperm and acrosome reaction [48, 49].

Presently however, the status of total PR and PRB was different in the uterus, ovary, and placenta. For instance, in endometrial epithelial cells, nuclear PR was more abundant than PRB, which was immunolocalized more predominantly in endometrial stroma cells. PRA and PRB are reportedly expressed in comparable levels in the endometrial epithelium, with PRA being the predominant isoform in the stroma of uterus [50], which is consistent with the present results. These results also indicate more important roles of PRB in endometrial epithelial cells than in stroma cells. Further investigations are required to confirm this. In the ovary, PR and PRB were both immunolocalized in the ovarian surface epithelial cell, granular cells, and fallopian tubal epithelial cells, but little PRB was evident in luteinized cells. The present results are consistent with the detection of both PRA and PRB in fallopian tube tissues (synonymous with oviduct), where PRA was reported to be more abundant than PRB [51]. In addition, normal ovulation reportedly does not require PRB expression, which also suggests that PRB may play less important roles in the ovary compared to PRA [52]. However, in the breast, both PR and PRB were both immunolocalized in the ductal cell in the epithelium, which is consistent with the fact that the development of mammary glands cannot progress without the presence of PRB [52]. Therefore, progesterone signaling through PRB could play an important role in the breast but less so in uterus and ovary.

In the male reproductive system, both PR and PRB were detected equally in testis tissue, which is consistent with the actions of progesterone noted above and with the presence of cytoplasmic PR and PRB in Leydig or epithelial cells of the epididymis, which suggests the action of progesterone in these cells. We did not detect PR expression in the prostate, in contrast to previous studies [53-55]. However, the previous reports used benign or malignant specimens and detected PR expression in stromal cells [54, 55] and/or epithelium cells [53], which are different from the normal tissues we used.

In the CNS, the expression of the PR and PR isoforms were reported in rodent brain tissues including hypothalamus, frontal cortex, cerebellum, and pituitary gland using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and western blot analysis [56-58]. However, we detected PR and PRB nuclear immunoreactivity only in the pituitary gland. In addition, the PR positive cells in pituitary glands were co-localized with LH and PRL, but not FSH, consistent with observations in chicken pituitary tissue [59]. To the best of our knowledge, the correlation between PR expression and FSH, LH, or PRL secretion in the pituitary gland has not been reported. In other parts of the nervous system including the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and spinal cord, we did not detect PR expression. However, previous reports used western blot and RT-PCR analysis to demonstrate the presence of PR in rat brain [57, 58]. Moreover, in humans 16-65 years of age, mRNA for PR has been identified in the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and spinal cord [60]. RT-PCR and western blot analysis have indicated that estrogen can induce PR expression while progesterone reduces the expression of PR in the rat hypothalamus, frontal cortex, and cerebellum [57, 58]. The possibility that we did not examine specific PR positive brain regions or cell types exhibiting the highest PR status cannot be excluded. Further investigations are required for clarification. In addition, the RT-PCR detection of PR mRNA expression in the human brain has a higher sensitivity than immunohistochemistry analysis.

We also detected PR and PRB expression in the tissues of other non-reproductive organs. In the GI system, both PR and PR isoforms were detected in the human stomach using western blot analysis [61, 62]. However, tissues of the small intestine and colon displayed low or no PR expression [63, 64]. Thus, the present results are consistent with those of prior studies; PR and PRB were equally present in the fundic gland of the stomach, with relatively low levels in the crypt of the small intestine and colon. The status of PR in the human liver has remained unknown. PR is expressed in the liver of the lizard (Podarcis sicula) [65]. We also demonstrated both PR and PRB in human hepatocytes, especially around the central and portal veins. PR in the pancreas has been previously reported and several reports detected PR in endocrine cells of the pancreas [66-68]. Of particular interest, we detected both PR and PRB in acinar cells. However, relatively low levels of PRB were reported in the Islet of Langerhans compared to the whole PR including PRA and PRB. These results suggest that the progesterone signal through PRB is important in the exocrine system, rather than the endocrine system, of the human pancreas. Further investigations are required for conformation. In the urinary system, both PR and PRB were detected in renal distal tubules using western blot analysis [69]. We also detected the immunolocalization of PR and PRB in proximal and distal tubules of the human kidney. In the urinary bladder, PR in the urethral squamous epithelium was reported as PRA using RT-PCR [37]. PR and PRB were also detected in the epithelium of the urinary bladder, which is consistent with the results of the present study. PR expression in the adrenal gland has been reported [70]. Of particular interest, we also detected PR and PRB in both the adrenal cortex and medulla, and PR and PRB were detected in zona fasciculata and the zona reticularis more than in the zona glomerulosa and medulla. PR expression in the submucosal gland has been described [71]. We also observed this expression. Our results show that keratinocytes in the skin express PR, an observation also reported previously [72, 73].

Significant differences in the PR H-score were evident among the different age groups in the pituitary gland, kidney, and medulla of the adrenal gland. However, only colon demonstrated a significant difference of PRB H-score between males and females in non-reproductive organs. It is true that the number of cases was rather limited in our study. Further studies are required for clarification.

The association of PR expression in normal and cancer tissues was examined using public databases. Databases of PR expression in cancers including RNA in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) datasets and protein in The Human Protein Atlas were used for comparisons between high PR expression in normal tissues including stomach, kidney, testis, colon, lung, liver, uterus, ovary, breast, pancreas, and adrenal gland. However, adrenal cancer is rare and the data are rather limited. TCGA datasets revealed that the median RNA expression level in Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million were 0.02, 0.03, 0.03, 0.09, 0.11, 0.16, 0.20 0.32, 2.40, and 6.04 in liver cancer, colorectal cancer, testis cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, renal cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and endometrial cancer, respectively. However, this mode of comparison is limited because RNA expression was not studied in normal tissues in our study. In addition, we also compared our findings with The Human Protein Atlas. The number of cases examined in this database was also very limited and results differed among data sets. Therefore, further investigations are required to clarify this aspect.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to demonstrate that both PR and PRB are distributed in specific cell types in each organ. In endocrine tissues, PR was expressed widely in many cell types. However, non-endocrine tissues expressed PR in more limited cell types compared to endocrine tissues. In addition, most of the organs were positive for PR and PRB in the cytoplasm, except for the female reproductive system, islet of Langerhans in pancreas and pituitary, which were PR and/or PRB positive mainly in the nucleus. This was indicative of the involvement of the nuclear signaling pathway in organs that were PR positive in the nuclei of cells. In general, PRB was often detected in non-endocrine organs. This indicates that PR signaling pathways differ between endocrine and non-endocrine organs in humans. The present findings provide new sights into progesterone actions and will inform further development of novel therapies for progesterone manipulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

PR monoclonal antibody production was performed by the Protein and Monoclonal Antibody Production Core facility at the Baylor College of Medicine Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center (Houston, Texas, USA) and was supported by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA125123) to D.P.E. We thank Kurt Christensen and Karen Moberg in the BCM Core for PR antibody production and Celetta Callaway for antibody purification. Moreover, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Ethics approval

The Ethics Committees of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine approved the protocol of this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferenczy A, Bertrand G, Gelfand MM. Proliferation kinetics of human endometrium during the normal menstrual cycle. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1979;133(8):859–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michalas S, Loutradis D, Drakakis P, Kallianidis K, Milingos S, Deligeoroglou E, et al. A flexible protocol for the induction of recipient endometrial cycles in an oocyte donation programme. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 1996;11(5):1063–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nosarka S, Kruger T, Siebert I, Grove D. Luteal phase support in in vitro fertilization: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2005;60(2):67–74. https://doi.org: 10.1159/000084546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navot D, Anderson TL, Droesch K, Scott RT, Kreiner D, Rosenwaks Z. Hormonal manipulation of endometrial maturation. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1989;68(4):801–7. https://doi.org: 10.1210/jcem-68-4-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park O-K, Mayo KE. Transient expression of progesterone receptor messenger RNA in ovarian granuiosa cells after the preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge. Molecular endocrinology. 1991;5(7):967–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisken C, Park S, Vass T, Lydon JP, O'Malley BW, Weinberg RA. A paracrine role for the epithelial progesterone receptor in mammary gland development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(9):5076–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz KM, Sisk CL. The organizing actions of adolescent gonadal steroid hormones on brain and behavioral development. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2016;70:148–58. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigil P, Del Río JP, Carrera B, ArÁnguiz FC, Rioseco H, Cortés ME. Influence of sex steroid hormones on the adolescent brain and behavior: An update. The Linacre quarterly. 2016;83(3):308–29. https://doi.org: 10.1080/00243639.2016.1211863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiller CE, Johnson SL, Abate AC, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Reproductive Steroid Regulation of Mood and Behavior. Comprehensive Physiology. 2016;6(3):1135–60. https://doi.org: 10.1002/cphy.c150014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin RW, Yao J, Hamilton RT, Cadenas E, Brinton RD, Nilsen J. Progesterone and estrogen regulate oxidative metabolism in brain mitochondria. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):3167–75. https://doi.org: 10.1210/en.2007-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JM, Johnston PB, Ball BG, Brinton RD. The neurosteroid allopregnanolone promotes proliferation of rodent and human neural progenitor cells and regulates cell-cycle gene and protein expression. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(19):4706–18. https://doi.org: 10.1523/jneurosci.4520-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morriss MC, Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT, Hunter JV, Haselgrove JC. Changes in brain water diffusion during childhood. Neuroradiology. 1999;41(12):929–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taveggia C, Feltri ML, Wrabetz L. Signals to promote myelin formation and repair. Nature reviews Neurology. 2010;6(5):276–87. https://doi.org: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schumacher M, Hussain R, Gago N, Oudinet JP, Mattern C, Ghoumari AM. Progesterone synthesis in the nervous system: implications for myelination and myelin repair. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2012;6:10. https://doi.org: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung-Testas I, Schumacher M, Robel P, Baulieu EE. Demonstration of progesterone receptors in rat Schwann cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 1996;58(1):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Zheng TZ, Li W, Qu SY, He DY. Action of progesterone on contractile activity of isolated gastric strips in rats. World journal of gastroenterology. 2003;9(4):775–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieuwenhuizen AG, Schuiling GA, Liem SM, Moes H, Koiter TR, Uilenbroek JT. Progesterone stimulates pancreatic cell proliferation in vivo. European journal of endocrinology. 1999;140(3):256–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kissebah AH, Harrigan P, Wynn V. Mechanism of hypertriglyceridaemia associated with contraceptive steroids. Hormone and metabolic research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et metabolisme. 1973;5(3):184–90. https://doi.org: 10.1055/s-0028-1093969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweezey N, Tchepichev S, Gagnon S, Fertuck K, O'Brodovich H. Female gender hormones regulate mRNA levels and function of the rat lung epithelial Na channel. The American journal of physiology. 1998;274(2 Pt 1):C379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotter A, Kipp M, Schrader RM, Beyer C. Combined application of 17beta-estradiol and progesterone enhance vascular endothelial growth factor and surfactant protein expression in cultured embryonic lung cells of mice. International journal of pediatrics. 2009;2009:170491. https://doi.org: 10.1155/2009/170491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen HC, Torday JS. Sex differences in fetal rabbit pulmonary surfactant production. Pediatric research. 1981;15(9):1245–7. https://doi.org: 10.1203/00006450-198109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatsumi K, Mikami M, Kuriyama T, Fukuda Y. Respiratory stimulation by female hormones in awake male rats. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 1991;71(1):37–42. https://doi.org: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couse JF, Lindzey J, Grandien K, Gustafsson J-Ak, Korach KS. Tissue Distribution and Quantitative Analysis of Estrogen Receptor-α (ERα) and Estrogen Receptor-β (ERβ) Messenger Ribonucleic Acid in the Wild-Type and ERα-Knockout Mouse. Endocrinology. 1997;138(11):4613–21. https://doi.org: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, Stropp U, Tora L, Gronemeyer H, et al. Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B. EMBO J. 1990;9(5):1603–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell. 2002;108(4):465–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Turcotte B, Gaub M-P, Chambon P. The N-terminal region of the chicken progesterone receptor specifies target gene activation. Nature. 1988;333(6169):185–8. https://doi.org: 10.1038/333185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boonyaratanakornkit V, McGowan E, Sherman L, Mancini MA, Cheskis BJ, Edwards DP. The role of extranuclear signaling actions of progesterone receptor in mediating progesterone regulation of gene expression and the cell cycle. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md). 2007;21(2):359–75. https://doi.org: 10.1210/me.2006-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim CS, Baumann CT, Htun H, Xian W, Irie M, Smith CL, et al. Differential localization and activity of the A- and B-forms of the human progesterone receptor using green fluorescent protein chimeras. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md). 1999;13(3):366–75. https://doi.org: 10.1210/mend.13.3.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clemm DL, Sherman L, Boonyaratanakornkit V, Schrader WT, Weigel NL, Edwards DP. Differential hormone-dependent phosphorylation of progesterone receptor A and B forms revealed by a phosphoserine site-specific monoclonal antibody. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md). 2000;14(1):52–65. https://doi.org: 10.1210/mend.14.1.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asavasupreechar T, Saito R, Edwards DP, Sasano H, Boonyaratanakornkit V. Progesterone receptor isoform B expression in pulmonary neuroendocrine cells decreases cell proliferation. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2019;190:212–23. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham JD, Yeates C, Balleine RL, Harvey SS, Milliken JS, Bilous AM, et al. Characterization of progesterone receptor A and B expression in human breast cancer. Cancer research. 1995;55(21):5063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenzo F, Jolivet A, Loosfelt H, Thu vu Hai M, Brailly S, Perrot-Applanat M, et al. A rapid method of epitope mapping. Application to the study of immunogenic domains and to the characterization of various forms of rabbit progesterone receptor. European journal of biochemistry. 1988;176(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke CL, Zaino RJ, Feil PD, Miller JV, Steck ME, Ohlsson-Wilhelm BM, et al. Monoclonal antibodies to human progesterone receptor: characterization by biochemical and immunohistochemical techniques. Endocrinology. 1987;121(3):1123–32. https://doi.org: 10.1210/endo-121-3-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1998;11(2):155–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyashita M, Sasano H, Tamaki K, Hirakawa H, Takahashi Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) and FOXP3(+) lymphocytes in residual tumors and alterations in these parameters after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Breast Cancer Research : BCR. 2015;17(1):124. https://doi.org: 10.1186/s13058-015-0632-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han Y, Feng HL, Sandlow JI, Haines CJ. Comparing expression of progesterone and estrogen receptors in testicular tissue from men with obstructive and nonobstructive azoospermia. Journal of andrology. 2009;30(2):127–33. https://doi.org: 10.2164/jandrol.108.005157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tincello DG, Taylor AH, Spurling SM, Bell SC. Receptor isoforms that mediate estrogen and progestagen action in the female lower urinary tract. The Journal of urology. 2009;181(3):1474–82. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricketts D, Turnbull L, Ryall G, Bakhshi R, Rawson NS, Gazet JC, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in the normal female breast. Cancer research. 1991;51(7):1817–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lessey BA, Killam AP, Metzger DA, Haney AF, Greene GL, McCarty KS Jr. Immunohistochemical analysis of human uterine estrogen and progesterone receptors throughout the menstrual cycle. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1988;67(2):334–40. https://doi.org: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boonyaratanakornkit V, Edwards DP. Receptor mechanisms of rapid extranuclear signalling initiated by steroid hormones. Essays in biochemistry. 2004;40:105–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dressing GE, Goldberg JE, Charles NJ, Schwertfeger KL, Lange CA. Membrane progesterone receptor expression in mammalian tissues: a review of regulation and physiological implications. Steroids. 2011;76(1-2):11–7. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu HB, Lu SS, Ji KL, Song XM, Lu YQ, Zhang M, et al. Membrane progestin receptor beta (mPR-beta): a protein related to cumulus expansion that is involved in in vitro maturation of pig cumulus-oocyte complexes. Steroids. 2008;73(14):1416–23. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nutu M, Weijdegard B, Thomas P, Bergh C, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Pang Y, et al. Membrane progesterone receptor gamma: tissue distribution and expression in ciliated cells in the fallopian tube. Molecular reproduction and development. 2007;74(7):843–50. https://doi.org: 10.1002/mrd.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nutu M, Weijdegard B, Thomas P, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Billig H, Larsson DG. Distribution and hormonal regulation of membrane progesterone receptors beta and gamma in ciliated epithelial cells of mouse and human fallopian tubes. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E. 2009;7:89. https://doi.org: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashley RL, Clay CM, Farmerie TA, Niswender GD, Nett TM. Cloning and characterization of an ovine intracellular seven transmembrane receptor for progesterone that mediates calcium mobilization. Endocrinology. 2006;147(9):4151–9. https://doi.org: 10.1210/en.2006-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashley RL, Arreguin-Arevalo JA, Nett TM. Binding characteristics of the ovine membrane progesterone receptor alpha and expression of the receptor during the estrous cycle. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E. 2009;7:42. https://doi.org: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernandes MS, Pierron V, Michalovich D, Astle S, Thornton S, Peltoketo H, et al. Regulated expression of putative membrane progestin receptor homologues in human endometrium and gestational tissues. The Journal of endocrinology. 2005;187(1):89–101. https://doi.org: 10.1677/joe.1.06242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas P, Tubbs C, Garry VF. Progestin functions in vertebrate gametes mediated by membrane progestin receptors (mPRs): Identification of mPRalpha on human sperm and its association with sperm motility. Steroids. 2009;74(7):614–21. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhler ML, Leung A, Chan SY, Wang C. Direct effects of progesterone and antiprogesterone on human sperm hyperactivated motility and acrosome reaction. Fertility and sterility. 1992;58(6):1191–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mote PA, Balleine RL, McGowan EM, Clarke CL. Colocalization of progesterone receptors A and B by dual immunofluorescent histochemistry in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1999;84(8):2963–71. https://doi.org: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teilmann SC, Clement CA, Thorup J, Byskov AG, Christensen ST. Expression and localization of the progesterone receptor in mouse and human reproductive organs. The Journal of endocrinology. 2006;191(3):525–35. https://doi.org: 10.1677/joe.1.06565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Conneely OM. Defective mammary gland morphogenesis in mice lacking the progesterone receptor B isoform. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(17):9744. 10.1073/pnas.1732707100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grindstad T, Richardsen E, Andersen S, Skjefstad K, Rakaee Khanehkenari M, Donnem T, et al. Progesterone Receptors in Prostate Cancer: Progesterone receptor B is the isoform associated with disease progression. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11358-. https://doi.org: 10.1038/s41598-018-29520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luetjens CM, Didolkar A, Kliesch S, Paulus W, Jeibmann A, Bocker W, et al. Tissue expression of the nuclear progesterone receptor in male non-human primates and men. The Journal of endocrinology. 2006;189(3):529–39. https://doi.org: 10.1677/joe.1.06348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu Y, Liu L, Xie N, Xue H, Fazli L, Buttyan R, et al. Expression and function of the progesterone receptor in human prostate stroma provide novel insights to cell proliferation control. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(7):2887–96. https://doi.org: 10.1210/jc.2012-4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon A, Garrido-Gracia JC, Aguilar R, Sanchez-Criado JE. Understanding the regulation of pituitary progesterone receptor expression and phosphorylation. Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 2015;149(6):615–23. https://doi.org: 10.1530/rep-14-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guerra-Araiza C, Coyoy-Salgado A, Camacho-Arroyo I. Sex differences in the regulation of progesterone receptor isoforms expression in the rat brain. Brain research bulletin. 2002;59(2):105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guerra-Araiza C, Villamar-Cruz O, Gonzalez-Arenas A, Chavira R, Camacho-Arroyo I. Changes in progesterone receptor isoforms content in the rat brain during the oestrous cycle and after oestradiol and progesterone treatments. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2003;15(10):984–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gasc JM, Baulieu EE. Regulation by estradiol of the progesterone receptor in the hypothalamus and pituitary: an immunohistochemical study in the chicken. Endocrinology. 1988;122(4):1357–65. https://doi.org: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pang Y, Dong J, Thomas P. Characterization, neurosteroid binding and brain distribution of human membrane progesterone receptors δ and {epsilon} (mPRδ and mPR{epsilon}) and mPRδ involvement in neurosteroid inhibition of apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2013;154(1):283–95. https://doi.org: 10.1210/en.2012-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gan L, He J, Zhang X, Zhang Y-J, Yu G-Z, Chen Y, et al. Expression profile and prognostic role of sex hormone receptors in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(1):566. https://doi.org: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saqui-Salces M, Neri-Gomez T, Gamboa-Dominguez A, Ruiz-Palacios G, Camacho-Arroyo I. Estrogen and progesterone receptor isoforms expression in the stomach of Mongolian gerbils. World journal of gastroenterology. 2008;14(37):5701–6. https://doi.org: 10.3748/wjg.14.5701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slattery ML, Samowitz WS, Holden JA. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in colon tumors. American journal of clinical pathology. 2000;113(3):364–8. https://doi.org: 10.1309/5mhb-k6xx-qv50-pcjq. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pfaffl MW, Lange IG, Meyer HH. The gastrointestinal tract as target of steroid hormone action: quantification of steroid receptor mRNA expression (AR, ERalpha, ERbeta and PR) in 10 bovine gastrointestinal tract compartments by kinetic RT-PCR. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2003;84(2-3):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paolucci M, Di Cristo C. Progesterone receptor in the liver and oviduct of the lizard Podarcis sicula. Life sciences. 2002;71(12):1417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doglioni C, Gambacorta M, Zamboni G, Coggi G, Viale G. Immunocytochemical localization of progesterone receptors in endocrine cells of the human pancreas. Am J Pathol. 1990;137(5):999–1005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim SJ, An S, Lee JH, Kim JY, Song K-B, Hwang DW, et al. Loss of Progesterone Receptor Expression Is an Early Tumorigenesis Event Associated with Tumor Progression and Shorter Survival in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Patients. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51(4):388–95. https://doi.org: 10.4132/jptm.2017.03.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arnason T, Sapp HL, Barnes PJ, Drewniak M, Abdolell M, Rayson D. Immunohistochemical expression and prognostic value of ER, PR and HER2/neu in pancreatic and small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;93(4):249–58. https://doi.org: 10.1159/000326820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bumke-Vogt C, Bahr V, Diederich S, Herrmann SM, Anagnostopoulos I, Oelkers W, et al. Expression of the progesterone receptor and progesterone- metabolising enzymes in the female and male human kidney. The Journal of endocrinology. 2002;175(2):349–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Cremoux P, Rosenberg D, Goussard J, Bremont-Weil C, Tissier F, Tran-Perennou C, et al. Expression of progesterone and estradiol receptors in normal adrenal cortex, adrenocortical tumors, and primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease. Endocrine-related cancer. 2008;15(2):465–74. https://doi.org: 10.1677/erc-07-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marquez-Garban DC, Mah V, Alavi M, Maresh EL, Chen H-W, Bagryanova L, et al. Progesterone and estrogen receptor expression and activity in human non-small cell lung cancer. Steroids. 2011;76(9):910–20. https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pelletier G, Ren L. Localization of sex steroid receptors in human skin. Histology and histopathology. 2004;19(2):629–36. https://doi.org: 10.14670/hh-19.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Im S, Lee ES, Kim W, Song J, Kim J, Lee M, et al. Expression of progesterone receptor in human keratinocytes. Journal of Korean medical science. 2000;15(6):647–54. https://doi.org: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.6.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.