Summary

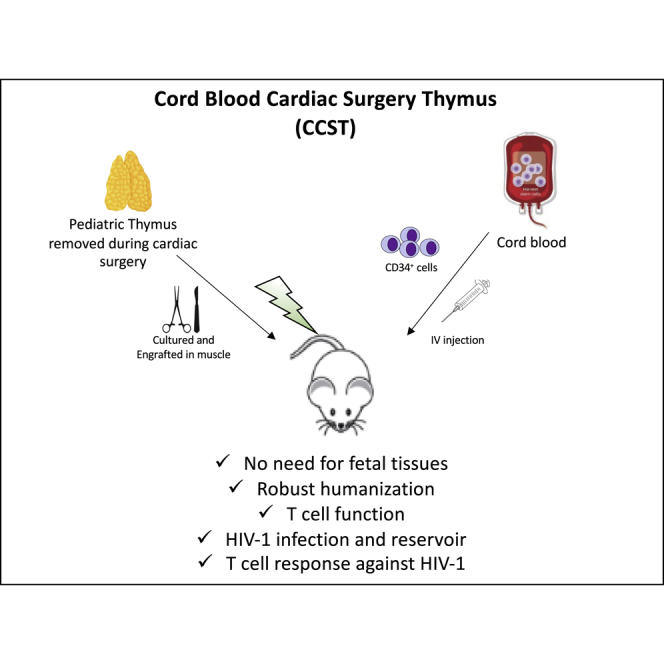

Humanization of mice with functional T cells currently relies on co-implantation of hematopoietic stem cells from fetal liver and autologous fetal thymic tissue (so-called BLT mouse model). Here, we show that NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice humanized with cord blood- derived CD34+ cells and implanted with allogeneic pediatric thymic tissues excised during cardiac surgeries (CCST) represent an alternative to BLT mice. CCST mice displayed a strong immune reconstitution, with functional T cells originating from CD34+ progenitor cells. They were equally susceptible to mucosal or intraperitoneal HIV infection and had significantly higher HIV-specific T cell responses. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) robustly suppressed viremia and reduced the frequencies of cells carrying integrated HIV DNA. As in BLT mice, we observed a complete viral rebound following ART interruption, suggesting the presence of HIV reservoirs. In conclusion, CCST mice represent a practical alternative to BLT mice, broadening the use of humanized mice for research.

Keywords: humanized mouse model, functional T cells, thymus, hematopoietic stem cells, HIV

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The CCST model is a robust humanized mouse model made without fetal tissues

-

•

T cell function is similar in CCST and gold-standard BLT mouse model

-

•

CCST mice are susceptible to HIV-1 infection and develop HIV reservoirs

-

•

A more robust T cell response against HIV is observed in CCST mice

We herein report a new humanized mouse model consisting of human cord blood hematopoietic stem cells and allogeneic pediatric thymic tissue obtained from cardiac surgery. This cord blood cardiac surgery thymus (CCST) mouse model allows for the development of a functional T cell compartment and supports efficient HIV infection and persistence during antiretroviral therapy.

Introduction

For the last three decades, the development of humanized mice aiming at modeling faithfully the human immune system has been an important quest. Indeed, several human diseases cannot be modeled in rodents, thus hindering research in immune pathophysiology and drug development. To obtain a humanized immune system, the most commonly used model is achieved by injecting human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull (NSG) mice (humNSG). This humNSG model allows for the development of partially functional lymphoid and myeloid human cells (Garcia and Freitas, 2012; Matsumura et al., 2003). Indeed, in the absence of a human thymic environment, HSC-derived T cell progenitors cannot undergo full maturation and education since the mouse thymus is atrophic in NSG mice and, in addition, does not express human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules (Lee et al., 2019). To address this issue, the bone-marrow-liver-thymus (BLT) model was developed (Garcia and Freitas, 2012; Kalscheuer et al., 2012; Lan et al., 2006). In this BLT model, fetal human thymic pieces are engrafted under the mouse kidney capsule, along with an intravenous (i.v.) injection of HSCs purified from the autologous fetal liver. This model allows a more authentic thymopoiesis and consequently displays an improved human T cell reconstitution and function compared with the humNSG (Garcia and Freitas, 2012; Kalscheuer et al., 2012; Lan et al., 2006). Humanized models that exhibit a multilineage immune reconstitution and a functional T cell compartment, such as the BLT, are paramount in studies of human-specific pathogens, such as HIV, that infect cells of the immune system.

Mice are not susceptible to HIV infection owing to the lack of essential virus-dependency host factors that HIV relies on to support viral entry, expression, and production of infectious particles (Morrow et al., 1987). Thus, the development of humanized mice represents a major advance in this field in that it enables studies of HIV replication, pathogenesis, immune responses, and sensitivity to therapeutics (Victor Garcia, 2016). When inoculated with HIV, humNSG mice develop high levels of viremia with HIV invading multiple tissues (Halper-Stromberg et al., 2014; Holt et al., 2010; Joseph et al., 2010; Watanabe et al., 2007). However, a caveat of the humNSG model is the absence of the adaptive human immune response, and in this context, the BLT model is superior and currently considered the most advanced and versatile small animal system to study HIV transmission, persistence, and treatment (Denton and Garcia, 2011; Hatziioannou and Evans, 2012). BLT mice infected with HIV have high levels of sustained viremia, display virus-induced CD4+ T cell depletion, and are capable of mounting virus-specific humoral and cellular immune responses (Brainard et al., 2009). Importantly, viral replication in BLT mice can be completely suppressed by antiretroviral therapy (ART), making the model useful to investigate HIV persistence and to develop experimental strategies for eliminating/controlling persistent HIV reservoirs (Dash et al., 2019; Kessing et al., 2017; Nixon et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2016).

The BLT mouse model is extensively used to study the human immune system and is conceivably the gold standard to study HIV and human immune system interactions. However, access to human fetal tissues is challenging or even impossible in several countries, making this model not broadly available for research worldwide. Moreover, given the size of fetal tissues, the number of mice that can be made from one donor is limited. This constraint increases the variability during pre-clinical investigations, underlining the need for a larger production of mice per donor. Our goal was to develop a humanized mouse model using easy-to-access pediatric thymic tissues obtained during cardiac surgeries (thymectomy is often performed during major cardiac surgeries) that could support an optimal T cell reconstitution when co-engrafted with human cord blood-derived HSCs. Here, we report that this cord blood cardiac surgery thymus (CCST) humanized mouse model exhibits a functional T cell compartment that derives from CD34+ cells and recapitulates key features of HIV infection and persistence.

Results

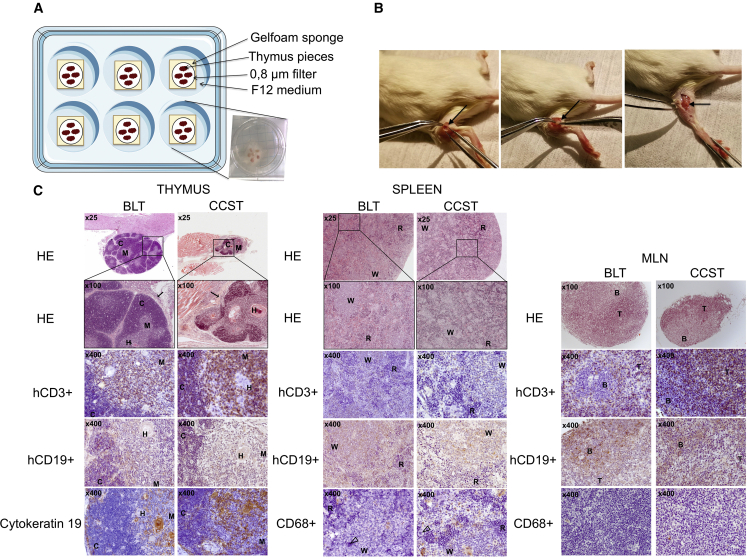

Histological structure of primary and secondary lymphoid organs recovered from BLT and CCST mice

The CCST model is based on the engraftment of pediatric thymic tissues, otherwise discarded during cardiac surgery, into the quadriceps femoris muscle. Thymic implantation is then followed by injection of cord bloodderived CD34+ within hours of the surgery (Figures 1A and 1B), similar to what is being done in human thymus transplantation (Markert et al., 2003, 2010). We first assessed the need to culture thymic pieces in vitro (as shown in Figure 1A) prior to engraftment in order to eliminate mature T cells. All mice (n = 6) engrafted with uncultured thymic pieces and HSC injection showed rapid engraftment of hCD3+ cells and died within 2 months from what appeared to be a graft-versus-host disease (GvHD)-like syndrome (Figure S1). In contrast, most mice (5 of 6) engrafted with previously cultured thymic pieces, as performed in human transplantation (Markert et al., 2003, 2010), survived for at least 20 weeks post-humanization (p = 0.0006, Figure S1). Consistent with this outcome, histological and flow-cytometry analyses showed that a cultured thymus had significantly fewer hCD3+ cells after 10 days in culture (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Pediatric thymus from cardiac surgery can be implanted into NSG mice as an alternative to fetal thymus

(A) Thymus retrieved from 3-day-old to 5-year-old donors undergoing cardiac surgery was cut into 1-mm2 pieces and put on a gelfoam sponge culture system for 7–21 days.

(B) Two to three pieces were engrafted into the quadriceps muscle of NSG mice along with an i.v. injection of 1–2 × 105 umbilical cord blood CD34+ (see Video S1).

(C) Left panels: representative thymic tissue sections from both BLT and CCST mice recovered at 30 weeks post humanization (left panels). Hematoxylin-phloxin-safran staining shows that engrafted tissues were well inserted in the surrounding tissues (arrow, in the kidney for BLT and in the quadriceps muscle for CCST). Both models showed typical thymus structure with cortex (C), medulla (M), and Hassall’s corpuscles (H). Immunochemistry staining shows the presence of hCD3+ (T cells) and hCD19+ (B cells). The thymus displayed medullar and cortical arrangement with thymic epithelium expressing cytokeratin 19. Middle panels: spleen tissues from both BLT and CCST displaying white (W) and red (R) pulp, T cells (hCD3+), B cells (hCD19+), and monocytes (hCD68+), as well as megakaryocyte (open arrowhead). Right panels: mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) recovered from BLT and CCST mice displayed germinal centers with B and T lymphocyte zones.

Fetal thymic pieces engrafted under the kidney capsule of BLT mice were capable of growing to more than ten times their size. In contrast, CST from CCST mice did not exhibit a size expansion and was indeed difficult to recover and separate from the muscle fiber. Nevertheless, histological analysis showed that in both cases the thymi were well integrated into the surrounding tissues with the presence of connective tissue (Figure 1C). Moreover, in both models, thymi were similarly populated with numerous CD3+ cells and some CD19+ cells. Hassall’s-like corpuscle structures were observed (Figure 1C, left) in both models, although larger in the CCST mice, indicating increased activity of the thymus. Unlike in mice humanized without a human thymus graft (humNSG), mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) with an organized structure, including germinal center with distinct T and B lymphocyte zones, were developed in both BLT and CCST mice (Figure 1C, right). As well, spleens with comparable structures were observed in both models (Figure 1C, middle). Hence, CCST mice developed primary and secondary lymphoid organs that were similar to those observed in the BLT model.

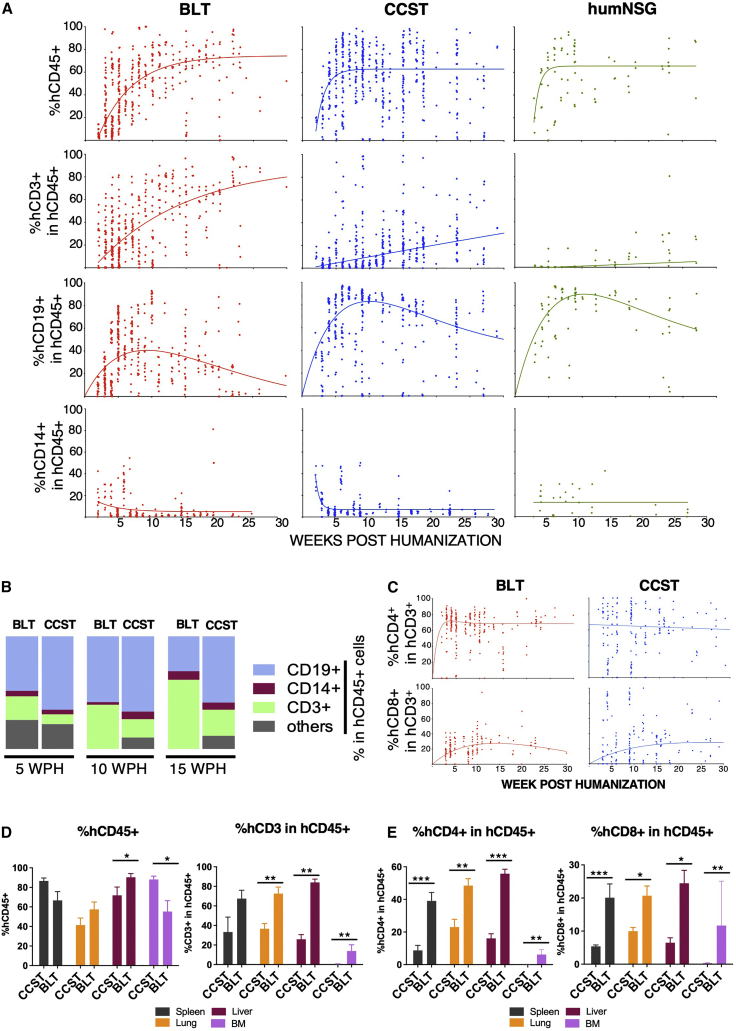

Human immune cell reconstitution in CCST mice

The kinetics of human immune cell reconstitution was assessed in peripheral blood. In BLT and CCST models, human CD45+ cells could be observed as early as 2 weeks after humanization (Figure 2A). All three models showed comparable kinetics and intensity of hCD45+ reconstitution (p = 0.4228, two-way ANOVA). Indeed, BLT showed a reconstitution going from an average of 56% ± 19% to an average of 73% ± 26% of hCD45+ cells between 10 and 20 weeks post humanization (wph) while CCST and humNSG both plateaued at approximately 60% by 5 wph (Figure 2A, upper graphs; averages of 64% ± 24% at 10 wph and 56% ± 33% at 20 wph for CCST; averages of 46% ± 5.2% at 10 wph and 64% ± 2% at 20 wph for humNSG). Significant differences between groups were observed for hCD3+ (calculated among hCD45+, Figure 2A) (p < 0.0001 for BLT versus CCST; p < 0.0001 for BLT versus humNSG; p < 0.001 for CCST versus humNSG; two-way ANOVA). While only less than 1% of hCD3+ cells were detected at 10 wph in humNSG, BLT mice supported the development of human T cells within 2–3 wph, resulting in a rapid and robust reconstitution of the hCD3+ population (average of 16% ± 24%; Figure 2A). As in BLT mice, CCST mice displayed early T cell reconstitution, with the detection of hCD3+ cells after 2 weeks (average of 3.6% ± 4.8%), which then increased gradually throughout the life of the mice (Figure 2A). Regarding hCD19+, although the shape of the reconstitution curve was similar in all three models, significant differences in the proportion of hCD19+ among hCD45+ were observed between the groups (p < 0.0001 for BLT versus CCST; p < 0.0001 for BLT versus humNSG; p < 0.01 for CCST versus humNSG; two-way ANOVA). No significant differences were found for the hCD14 population (p = 0.8420, two-way ANOVA).

Figure 2.

Unlike humanized mice without a thymus (humNSG), CCST and BLT humanized models allow for robust T cell reconstitution

(A) Peripheral blood from mice of the three models was harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for the level of human cell reconstitution (each dot represents a mouse analyzed at a given time point). Extent of the reconstitution of hCD45+ (calculated among total CD45+ cells [mouse and human]), hCD3+ (among hCD45+), hCD19+ (among hCD45+), and hCD14+ (among hCD45+) was as shown. A non-linear regression curve was calculated for each subpopulation using the growth exponential association model for all populations except hCD19, for which a two-phase exponential association model was applied.

(B) Graphic representation of the relative proportions of human T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD19+) and monocytic cells (CD14+) in BLT and CCST mice at 5, 10, and 15 weeks post humanization, showing an increase in T cell proportion over time for BLT mice.

(C) Dynamic changes in the level of human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within the hCD3+ population in peripheral blood of CCST and BLT mice. Non-linear regression curves were calculated using a two-phase exponential association model.

(D and E) (D) Proportions of human CD45+ and CD3+ and (E) levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in tissues of CCST and BLT mice at 25 weeks post humanization as measured by flow cytometry. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare ranks of two groups. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

The relative proportion of the different human immune cell populations in the blood was compared between BLT and CCST mice. In BLT mice, the hCD3+ population increased in proportion through time and stabilized with human cells composed of mainly T cells (hCD3+), followed by B cells (hCD19+) and monocytes (hCD14+) (Figure 2B). In contrast, CCST had predominantly hCD19+, balanced with hCD3+ and hCD14+ as well as other hCD45+ cells (Figure 2B). Interestingly, this cell distribution remained stable through time. Within the hCD3+ population, the proportions of hCD4+ and hCD8+ cell populations were comparable between BLT and CCST mice (p = 0.6500 for hCD4 between models and p = 0.0995 for hCD8; two-way ANOVA), although CCST data showed a higher variability between mice (Figure 2C). Analysis of the human cell immune population in the lung, liver, bone marrow, and spleen showed that levels of hCD45+ cells were overall comparable between the two models, while that of hCD3+ was significantly higher in tissues of BLT mice compared with CCST (Figure 2D). Consequently, human CD4+ and hCD8+ proportions among the human immune cells (hCD45+) were also significantly higher in tissues of BLT mice relative to CCST mice (Figure 2E). Altogether, the CCST model reconstituted a human immune system that was qualitatively and quantitatively an intermediate between BLT and humNSG mice, with a robust hCD3+ compartment and secondary lymphoid organs, two key characteristics for immune function.

One could argue that T cells observed in CCST mice are thymus-derived proliferating mature T cells, mimicking the model whereby NSG mice are injected with peripheral blood mononuclear cells. However, this is highly unlikely for several reasons. First, the kinetics of T cell count rise in CCST was slow and, as such, could not have been a result of proliferation of peripheral mature T cells (Figure 2A). Second, in the absence of cord blood CD34+ cells, NSG mice engrafted with a cardiac surgery thymus, which had been cultured under the same conditions as in CCST mice, had few circulating T cells (<1%, data not shown). Nevertheless, to formally rule out this possibility and confirm that T cells in CCST mice actually stemmed from CD34+ cells that seeded the thymus and differentiated into thymic progenitors and mature T cells, CCST mice were engrafted with CD34+ cells previously transduced with a GFP-expressing lentivirus (39% transduction efficiency). First, from the apparition of hCD3 until week 7 post humanization, our data suggest that there was a transient mix of T cells originating from CD34+ HSC and of T cells coming directly from the CST. Then, after week 7, based on GFP+hCD3+ proportion, these T cells originating from the implanted thymus seemed to have been replaced by the engrafted CD34+ cells. Indeed, after 7 wph, we observed that the percentage of GFP+ cells was similar in all lineages (B, T, or CD14+), strongly suggesting that, from this point on, T cells did originate from the CD34+ cell pools (Figure 3A). Otherwise, the hCD3+GFP+ population would have been lower than the hCD19+ GFP+ or hCD14+GFP+. Interestingly, the same was true for BLT mice, as illustrated in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

Circulating human immune cells in CCST and BLT mice originate from engrafted CD34+ hematopoetic stem cells

Human HSCs were transduced with a GFP-expressing lentivirus. Transduction efficiency was 39% at the time of mouse engraftment. (A and B) Immune reconstitution data from (A) CCST (n = 3) and (B) BLT (n = 2) mice up to 19 weeks post humanization (wph). T cell (hCD3+), B cell (hCD19+), and monocyte (CD14+) compartments exhibited similar proportions of GFP-expressing cells. The y axis is indicative of the percentage of GFP+ cells within the population indicated in the x axis (either hCD3+, hCD19+, or hCD14+).

(C) Flow-cytometry analysis of the different subpopulation of T cells, namely T central memory (CD3+CCR7+CD45RA−), T effector memory (CD3+CCR7−CD45RA−), T effector memory re-expressing CD45R (EMRA, CD3+CCR7−CD45RA+), and naive T cells (CD3+CCR7+CD45RA+) populations in both CD4+ (top graphs) and CD8+ T cells (bottom graphs) of the CCST and BLT models (left and right columns, respectively).

Flow-cytometry analyses of T cell subsets, namely T central memory (CD3+CCR7+CD45RA−), T effector memory (CD3+CCR7−CD45RA−), T effector memory re-expressing CD45RA (EMRA, CD3+CCR7−CD45RA+), and naive T cells (CD3+CCR7+CD45RA+) in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells revealed that CCST and BLT models did not have the same distributions. Indeed, while BLT mice had a distinct predominance of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, CCST mice showed more variability with a higher proportion of cells that are either central memory or EMRA compared with BLT (Figure 3C).

T cell function in CCST and BLT mice

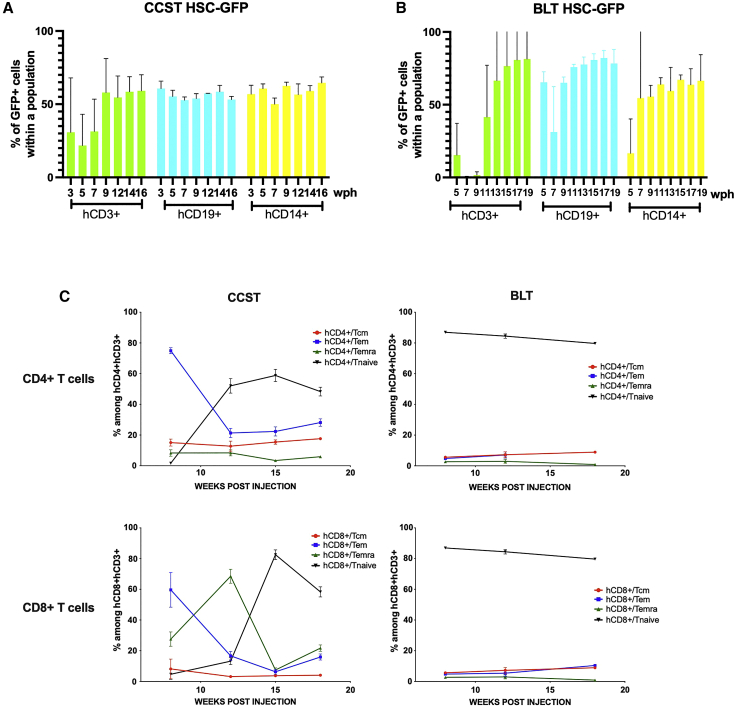

We tested T cell function using both an allogeneic human tumor challenge and an ex vivo phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-dependent proliferation assay. The tumor challenge was performed by injecting allogeneic luciferase-expressing human pre-B leukemic REH cell line (Figures 4A–4C). All REH-challenged humNSG reached high levels of luciferase expression 3–6 weeks following tumor cell injection and died within 7 weeks, while no REH leukemic cells were detected in any of the BLT mice, as shown by the absence of luciferase signal and 100% survival rate (Figures 4A–4C). In comparison, the response to REH challenge was more variable with CCST mice. Indeed, 5 out of the 14 CCST mice (35%) injected with REH controlled leukemic cell growth while the other CCST mice allowed for the establishment of leukemia, but with a significant delay in the kinetics of leukemic cell dissemination and, consequently, the survival (p < 0.001, Figures 4A–4C), compared with humNSG (p = 0.0002). Despite this relative control of leukemic growth, as a whole CCST mice had a higher luciferase activity (p = 0.0111) and poorer survival than BLT mice (p = 0.0135).

Figure 4.

Functional T cells are developed in CCST and BLT mice

(A) Pre-B leukemic REH cells expressing luciferase were injected in the three humanized models, and mice were imaged weekly by injecting D-luciferin to follow the progression of the leukemic cells. Depicted are representative BLT, CCST, and humNSG mice with different capabilities to respond to the REH challenge.

(B) Intensity of the luciferase expression (expressed in photons per cm2) was used as a surrogate marker of leukemia progression in BLT mice (red line), CCST mice (blue line), and humNSG mice (green line). Medians ± range are shown for the luciferase signal. p = 0.0111 between BLT and CCST, p = 0.0002 between humNSG and CCST, and p < 0.0001 between BLT and humNSG (two-way ANOVA).

(C) Survival curves show a significant difference (log-rank tests) between BLT (n = 10, red line), CCST (n = 14, blue line), and humNSG (n = 8, green line). BLT versus humNSG: p < 0.0001; BLT versus CCST: p = 0.0135; CCST versus humNSG: p = 0.0001.

(D) Proliferative capacity of peripheral blood T cells isolated from the three models of humanized mice was tested by ex vivo stimulation with 5 μg/mL PHA-L for 24 h in the presence of EdU. Representative flow-cytometry plots are shown for each model.

(E) Enumeration of hCD4+hCD8+EdU+ cells showed that T cells from CCST (n = 7) and BLT (n = 8) mice proliferated significantly more than humNSG (n = 7) mice (p = 0.0061 with CCST, p < 0.0001 with BLT). T cells isolated from CCST mice proliferated also less than BLT (p = 0.0466). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

In the context of PHA-dependent proliferation assay, both hCD4+ and hCD8+ T cells from CCST and BLT mice incorporated 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) following mitogen stimulation, albeit at a lower level for CCST mice (median of 46.67% for BLT and 21.62% for CCST, p = 0.0466, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). In contrast, T cells isolated from humNSG did not respond to PHA stimulation (Figures 4D and 4E, median of 5.69%, p = 0.0061 compared with CCST, p < 0.0001 compared with BLT; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). T cells isolated from BLT and CCST mice had respectively a mean of 8- and 5-fold more EdU+ cells than those from humNSG (Figure 4E, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA). Altogether, these data indicate that T cells from CCST mice were functionally capable of proliferating upon mitogen stimulation and rejecting tumor cell challenge.

Robustness of the CCST model

To assess whether it was possible to generate CCST mice with biobanked tissues, we compared animals made with fresh thymic tissues with those made with previously frozen thymic pieces. As shown in Figure S3, mice humanized with biobanked tissues were comparable with those generated with fresh tissues in terms of the level of CD3+ cells and T cell ability to reject infused leukemic cells. Overall, the success rate was 74.8% (242 mice; 27 groups, defined by mice made on the same day with the same tissues and HSCs). Mice within groups were widely homogeneous in that they were either all usable or not at all, except for 3 of the 27 groups in which there was a mix in the quality of the immune reconstitution, suggesting that the variability principally lay between the groups and not within a group. Finally, the impact of HLA compatibility between thymic pieces and injected CD34+ cells on the quality of immune reconstitution was assessed in 103 CCST mice, whereby no significant impact was detected (p = 0.9232, chi-squared test, Table S1). Similarly, the age of the engrafted thymus did not affect significantly the level of immune reconstitution (p = 0.0732, chi-squared test, Figure S4A) or T cell function, as evaluated by the ability to clear REH (p = 0.4805, two-sided chi-squared test, Figures S4B and S4C).

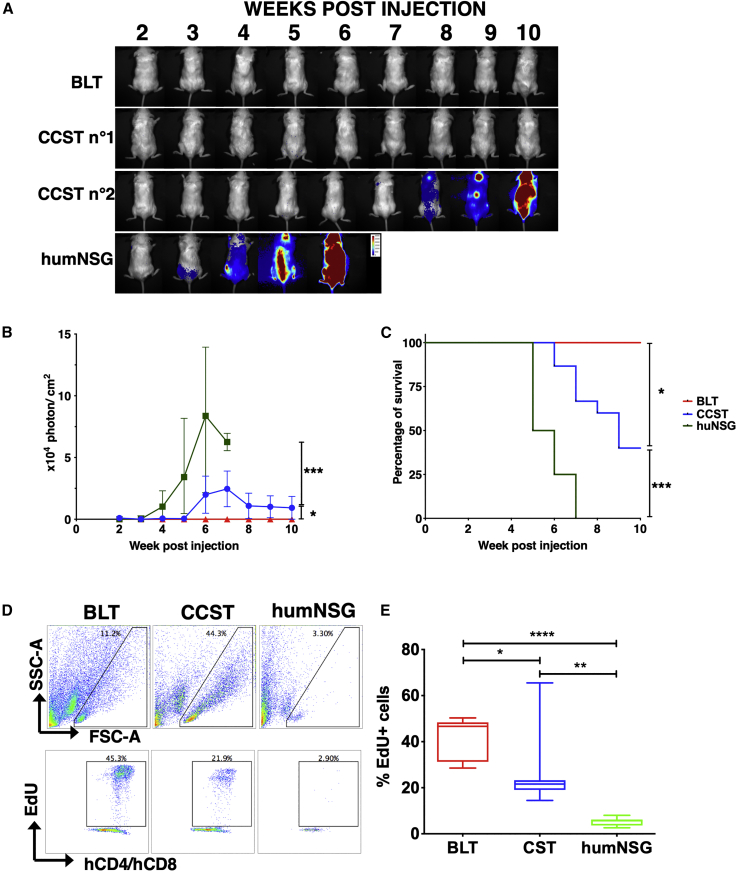

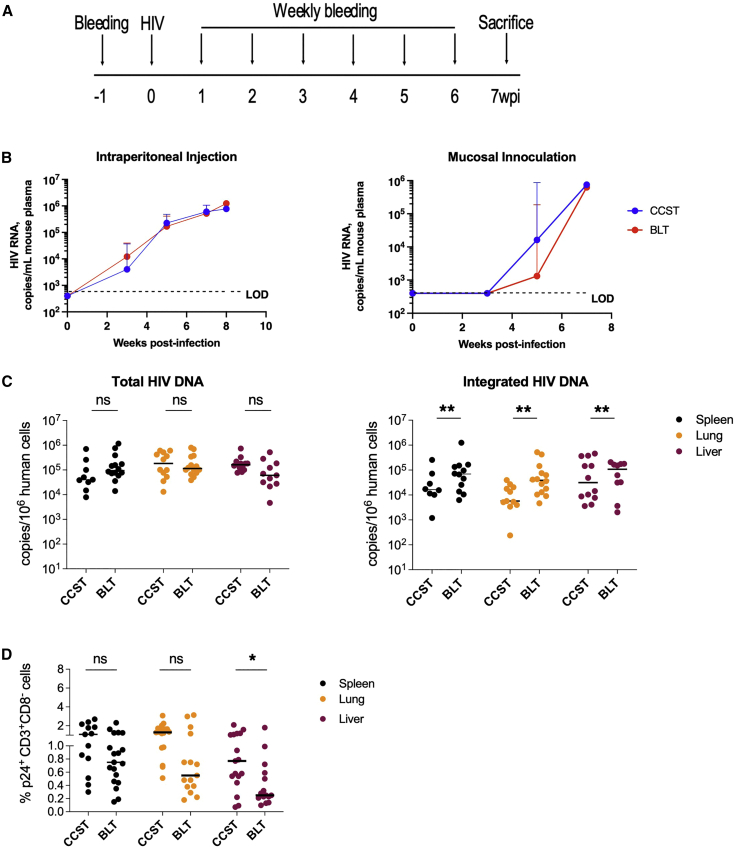

CCST mice support efficient HIV infection and mount robust HIV-specific T cell responses

As stated above, BLT mice are the gold standard of humanized mouse models to study pathogenesis and treatment of HIV infection (Denton and Garcia, 2011; Hatziioannou and Evans, 2012). We thus compared key characteristics of HIV infection in CCST and BLT models using HIV NL4.3-ADA-GFP (Figure 5A). First, we observed that both models were susceptible to HIV infection via the mucosal or intraperitoneal route, as viral loads were detectable at similar levels through time post infection (Figure 5B). As well, real-time PCR analysis showed nearly comparable abundance of total viral DNA in different tissues, although frequencies of integrated HIV DNA-positive cells in spleen, lung, and liver were significantly higher in BLT mice (Figure 5C). Interestingly, in CCST mice the frequency of productively infected (p24+) CD4+ T cells was higher in the liver, though not significantly different in spleen or lung tissues. (Figure 5D; gating strategy illustrated in Figure S5).

Figure 5.

CCST mice are as susceptible to HIV infection as BLT mice

(A) CCST and BLT mice were infected with 200,000 TCID50 of NL4.3-ADA-GFP HIV via intraperitoneal injection or vaginal inoculation and monitored for 7 weeks.

(B) Plasma viral load measured in CCST (blue lines) and BLT (red lines) mice following HIV infection. Shown are median values (+95% confidence interval) from 9–19 (depending on the time point) CCST and 15 BLT mice injected intraperitoneally and 7 CCST and 6 BLT mice inoculated vaginally.

(C) Levels of total and integrated HIV DNA in the spleen, lung, and liver, quantified by real-time PCR.

(D) Frequency of virus-expressing (p24+) human CD4+ T cells (as defined by hCD3+hCD8− owing to HIV-mediated CD4 downregulation) in the spleen, lung, and liver as measured by flow cytometry.

wpi, weeks post infection; LOD, limit of detection. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare ranks of two groups. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

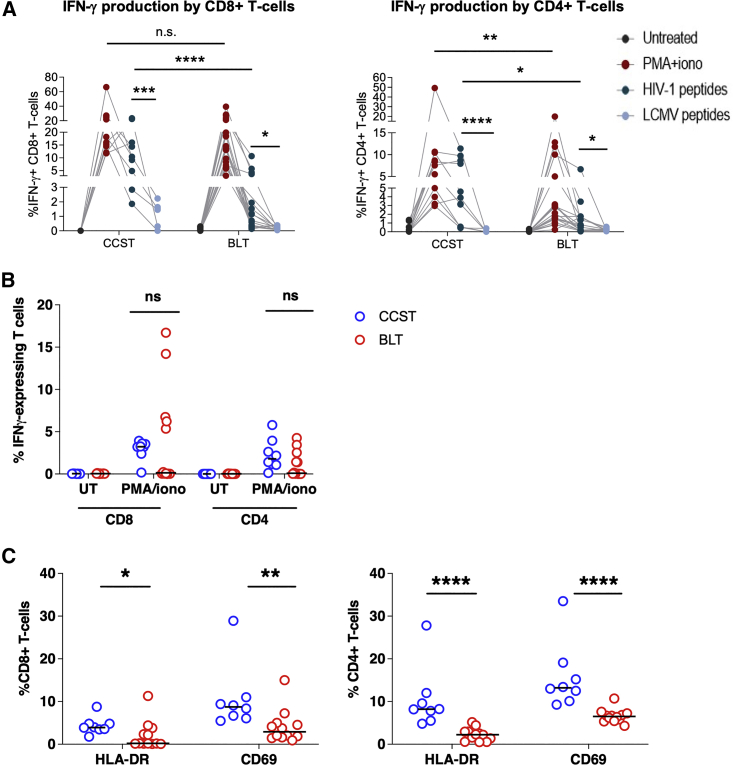

Having demonstrated that CCST mice were highly susceptible to HIV infection, we next asked whether T cells from infected animals could elicit T cell response upon ex vivo stimulation with HIV peptides. To this end, we pulsed T cells from the spleen with HIV peptide pools (Zhen et al., 2017) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and then assessed their capacity to produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ). To this end, we observed that in response to HIV peptides, significantly higher levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in CCST mice were producing IFN-γ compared with BLT mice (median: 10.4% versus 0.7%, p < 0.0001 for CD8+ T cells and 3.9% versus 0.7%; p < 0.01 for CD4+ T cells, respectively; p < 0.0001; Figures 6A and S6). As well, PMA stimulation resulted in more CD4+ T cells from CCST mice expressing IFN-γ although no differences were noted for CD8+ T cells. A similar analysis of splenic T cells from uninfected CCST and BLT mice showed that in response to mitogenic stimulation with PMA/ionomycin, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets were able to produce IFN-γ, highlighting once again that T cells developed in CCST mice are functional. However, we found no statistically significant difference in the frequency of IFN-γ-expressing T cells between CCST and BLT mice (Figure 6B), although T cells from the spleen of CCST mice expressed a higher level of activation markers HLA-DR and CD69 relative to those from BLT mice (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Comparison of general and HIV-specific T cell response in CCST and BLT mice

(A) Splenocytes from infected CCST and BLT mice were kept untreated or stimulated with PMA/ionomycin, pooled Clade B HIV peptides (env, gag, pol, nef) (2 μg/mL), or lymphocytic choreomeningitis virus (LCMV) peptides (GP61-80, GP276-286) (100 ng/mL). LCMV stimulation served as a specificity control for the assay. Frequencies of cytokine-expressing human T cells were measured intracellularly by flow cytometry. Depicted are overall data in different mice (CCST, 10 mice and BLT, 12 mice). Four dots connecting each line represent an individual mouse.

(B) Splenocytes from uninfected (UI), unstimulated CCST and BLT mice were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin and assessed for IFN-γ expression in T cells as described in (A).

(C) Surface expression of activation markers HLA-DR and CD69 on T cells from the spleen of uninfected CCST (blue) and BLT (red) mice was measured by flow cytometry.

In all panels, each dot is one mouse. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare ranks of two groups. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Overall, our findings revealed that CCST mice could be efficiently infected with HIV and that T cells developed in this model were functional and capable of expressing cytokines following antigenic stimulation.

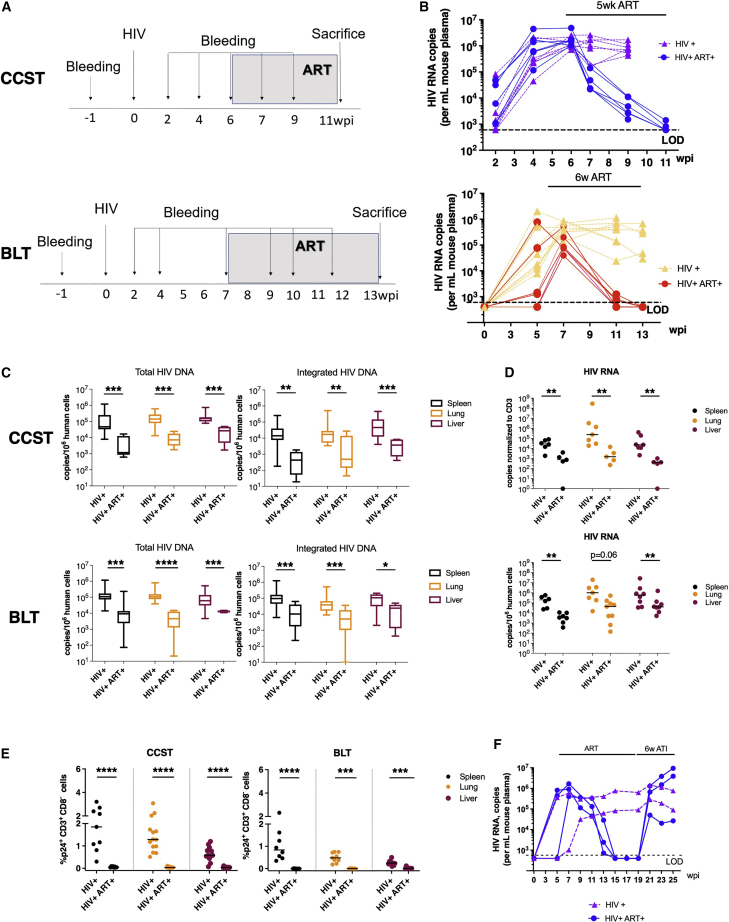

CCST mice as an investigative model to study HIV persistence during ART

Having shown that CCST mice were capable of supporting efficient infection and mounting an antigen-specific T cell response, we next wanted to establish whether this humanized mouse model could be used to characterize the development of HIV reservoirs. To study this aspect, we infected CCST and BLT mice and when the level of viremia started plateauing (about 6–7 weeks post infection), the animals were treated with an antiviral regimen containing emtricitabine, tenofovir, and raltegravir (Figure 7A). As expected, plasma viral loads were reduced to undetectable levels in ART-treated mice in both models (Figure 7B). Congruent with this observation, we observed a significant reduction in the level of total (5-to 24-fold) and integrated (12- to 33-fold) HIV DNA in different lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues (Figure 7C) in ART-treated mice. As well, ART resulted in a marked median reduction of cell-associated HIV RNA by at least 45- to 77-fold depending on organs (Figure 7D). Lastly, the proportion of p24+hCD3+hCD8− cells in tissues was suppressed to nearly undetectable levels in ART-treated mice in both models (Figure 7E, p < 0.001 in all ART conditions). Importantly, the fact that we observed a complete viral rebound upon treatment interruption demonstrates not only the presence of HIV reservoirs in infected CCST mice (Figure 7F) but also that CCST mice can be used as a model of HIV persistence during ART.

Figure 7.

Establishment of HIV latency in the CCST mouse model

(A) CCST mice were infected (intraperitoneal route) with 200,000 TCID50 of NL4.3-ADA-GFP HIV. At 6 weeks post infection (wpi), a group of infected mice was treated for up to 6 weeks with emtricitabine (100 mg/kg weight), tenofovir (50 mg/kg), and raltegravir (68 mg/kg). The control group was represented by untreated mice.

(B) Dynamic changes in plasma viral load over the course of infection and ART. Untreated mice are depicted in purple (CCST) and yellow (BLT), ART-treated mice in blue (CCST) and red (BLT).

(C) ART-induced changes in levels of total and integrated HIV DNA in different tissues of CCST and BLT mice.

(D) HIV RNA levels in tissues of untreated or ART-treated CCST and BLT mice.

(E) Effect of ART on the frequency of CD4+ T cells in tissues expressing viral protein p24.

(F) The presence of viral rebound following antiretroviral therapy treatment interruption (ATI, blue lines), supporting the existence of HIV latency in infected CCST mice. As a result of ATI, levels of viremia were increased to the level of untreated mice (green lines). Each line represents one mouse.

The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare ranks of two groups. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Discussion

Here, we describe a new model of humanized mice that fosters the development of functional T cells without the use of fetal tissues. This model comes in a timely fashion since research projects conducted with fetal tissues are becoming increasingly difficult to perform because of limitations in obtaining tissues. Therefore, there is a need for the development of new humanized mouse models that could substitute the BLT model without losing its advantages. In this study, we provide strong evidence that CCST mice could be a good alternative to BLT mice, especially for HIV research. Indeed, CCST mice displayed strong immune reconstitution, with T cells originating from CD34+ progenitor cells, proliferating efficiently in response to mitogenic stimulation ex vivo and capable of rejecting allogeneic human leukemic cells in vivo. These findings demonstrate the functionality of developed human T cells in CCST mice. Despite having fewer T cells than BLT mice, CCST mice were equally susceptible to mucosal or intraperitoneal HIV infection and mounted a stronger HIV-specific T cell response following infection. Importantly, the presence of integrated HIV DNA could be documented despite ART treatment and virological suppression, and viral rebound could be observed upon treatment interruption, indicating that CCST mice can be used as a model to study HIV persistence in the presence of antiretroviral therapy.

The CCST model is different from the recently developed NeoThy humanized mouse (Brown et al., 2018) in two major ways. In the latter model, neonatal thymic pieces of approximately 10-day-old neonates were implanted under the kidney capsule along with i.v. injection of CD34+ cells isolated from cord blood. Ours involves implantation of thymic tissues, which could be up to 5 years old, in the quadriceps instead of kidney capsule. We used this approach because initial attempts at implanting thymic pieces in the kidney capsule were repeatedly unsuccessful (data not shown), prompting us to ultimately adopt the procedure used for thymic transplantation in human (Markert et al., 2003, 2010) whereby the thymus is implanted in the quadriceps. According to our veterinary surgeon, the surgical procedure is less complex. Another advantage of this technique is that we could freeze thymic pieces and cord blood CD34+ cells to perform humanization when needed (Figure S3). Interestingly, as described in thymic transplantation in human (Markert et al., 2008), and as observed for the NeoThy model (Brown et al., 2018), HLA compatibility did not have an impact on the reconstitution of the immune system (Table S1). However, the use of pediatric thymi seems to require a pre-culture ex vivo to prevent rapid occurrence of a GvHD-like syndrome. In this context, we hypothesize that resident T lymphocytes from the thymic graft are capable of expanding and attacking recipient tissues and cells, leading to mouse death. As such, the pre-culture step is essential to eliminate potentially xenoreactive mature/maturing T cells from the engrafted thymus. Consequently, T cells developed in CCST mice, when the humanization is stabilized (after 7 weeks), are derived from the injected HSCs that are niched in the humanized mouse bone marrow, as demonstrated by the results from our GFP-transduced HSC experiments. The thymic culture could explain the differences observed in the reconstitution kinetics of hCD3+ cells in CCST mice compared with the BLT mice, whereby a pre-culture of fetal tissues is not needed. Kalscheuer et al. (2012) published a personalized model of immune-mediated disorders based on the engraftment of fetal thymus along with stem cells from adult patients. Interestingly, in this model it is necessary to administer anti-CD2 antibodies to eliminate mature T cells that might otherwise cause GvHD (Brown et al., 2018; Kalscheuer et al., 2012). This suggests that ex vivo culture or monoclonal antibody administration eliminates mature T cells from thymic pieces and reduces the occurrence of GvHD. Moreover, the T cell immune reconstitution observed in our CCST mice is similar to the one described in the NeoThy model (Brown et al., 2018), even though we injected a lower number of CD34+ cells.

The CCST humanized mice displayed organized primary and secondary lymphoid organs, suggesting the development of a functional immune system. The implanted thymus in CCST mice exhibited medullar and cortical arrangement with classical thymic epithelium expressing cytokeratin 19, as in the case with BLT mice. As well, the spleen from CCST mice shared similar structures with megakaryocytes observed in both models, indicating splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis. Lastly, MLNs displayed germinal centers having distinct T and B lymphocyte zones in both the BLT and CCST models.

The immune reconstitution in the peripheral blood of CCST mice was robust, albeit not as high as in the BLT, but clearly more efficient than in humNSG, particularly with respect to the T cell compartment. Interestingly, the replenishment of T cells in the CCST model was progressive, as observed after T cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation in human (Haddad et al., 1998). Similar to the BLT system, a transient first wave of T cells likely comprises mature T cells coming directly from the engrafted thymus; however, as humanization stabilizes, peripheral T cells observed in CCST mice are T cells stemming from HSCs that undergo a physiological differentiation in the transplanted thymus. This observation is supported by the similar distribution of GFP-expressing cells within hCD3, hCD19, and hCD14 cells. It is very unlikely that CD34+ cells differentiate in mouse thymus in the CCST mice given that we observed a good human thymic maturation with Hassal corpuscles and that humNSG mice did not display the same kinetics of T cell development. Moreover, the relative proportions of immune subpopulations remained stable through time in CCST mice. In addition, analyses of naive and memory T cell proportions showed that CCST mice have a transient population of EMRA T cells in the first weeks post humanization and that naive T cells become predominant after week 12. Altogether, these data suggest that the first “wave” of T cells coming out of a neonatal thymus (from an individual older than a fetus and living in a non-sterile environment) resulted in a lower proportion of naive T cells than T cells coming out of a fetal thymus. As time passed, naive T cells became predominant in both models, suggesting that the first wave of residing hCD3 exiting the thymus is replaced by new T cells stemming from the injected HSCs, which is consistent with the GFP data. As previously reported (Lan et al., 2006), the reconstitution of human CD45+ cells was slightly slower in BLT mice but ultimately reached higher levels. This difference in the reconstitution kinetics might be partially due to the source of hCD34+ (fetal liver versus cord blood), different numbers of injected cells (5 × 105 versus 1–2 × 105, respectively) and xenogeneic T cell proliferation.

Importantly, the CCST model recapitulated key T cell functions such as PHA-induced proliferation and allogeneic tumor rejection. This approach could be useful to study immune interactions with tumors, as one could model patient-derived xenograft and implant autologous immune system from the same patient’s HSCs together with an allogeneic thymus from cardiac surgery (either fresh or biobanked).

The classical humNSG model does not require the use of fetal tissues. Nevertheless, in the context of HIV research, the lack of a functional adaptive immune system in this model limits its capacity to help address important questions pertinent to virus-host interactions. Humanized NSG mice are also less susceptible to HIV infection through the mucosal route, which represents the main mode of viral transmission in human (Tebit et al., 2012). In this study, we demonstrate that CCST mice represent an efficient substitute for the BLT model for HIV study, and could be an option for research teams that cannot have access to fetal tissues. First, we show that CCST mice are equally susceptible to HIV infection through both the mucosal and intraperitoneal routes. Despite having fewer CD4+ T cells as targets for HIV infection, viral dissemination (plasma viral load) in CCST mice was comparable with that in BLT mice. Interestingly, we observed lower levels of integrated HIV DNA and higher levels of p24+ cells in certain organs of CCST mice. However, it remains to be established whether these differences were related to higher expression of HLA-DR and CD69 on T cells of CCST mice. It is tempting to speculate that the latter might be an inherent feature of the CCST system considering the source of the engrafted thymus (pediatric versus fetal as in BLT) and/or CD34+ cells (heterologous versus autologous as in BLT). This being said, despite these fundamental differences, we provide evidence showing that viral replication in CCST mice could be efficiently suppressed by ART and that there is bona fide viral rebound upon treatment interruption. The latter strongly supports the existence of authentic HIV reservoirs in these infected mice. Third, we demonstrate that HIV exposure leads to the development of a more vigorous HIV-specific T cell response in CCST mice compared with BLT. In this setting, CCST mice represent the first humanized animals generated without the need of fetal tissues and yet capable of eliciting antigen-driven immune responses, especially in the context of HIV infection.

Altogether, this new model of mouse humanization is robust and convenient by: (1) its wide range of potential thymus donors; (2) tissue abundance allowing for larger production; (3) the use of biobanked tissues; and (4) HLA independence. However, the CCST model has its own limitations. First, there is greater variability compared with the BLT model in terms of the overall reconstitution, relative distribution of immune subpopulations, and success rate (74.8%). The different distribution of immune cell subsets (Figure 2) might be linked in part to the technical difficulty in determining whether the thymic pieces to be implanted were components of the medulla and/or cortex. Since a fetal thymus is smaller than a pediatric thymus, pieces of the latter are more likely to comprise both the medulla and cortex than the former ones, which could explain the greater variability observed in the CCST model. However, although the level of T cells in CCST remains lower compared with BLT, this limitation does not constrain the levels of HIV viremia or the extent of viral infection.

In conclusion, the CCST model is a practical alternative to the BLT model that could prove to be better for HIV studies because of its robust antigen-specific T cell response. The ease by which the CCST model can be achieved, regarding surgery skills, availability of thymic material, and the fact that thymic sections can be cryopreserved and biobanked, could dramatically increase the availability of functional humanized mouse models worldwide and facilitate, among others, in vivo HIV research.

Experimental procedures

Resource availability

Corresponding author

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding authors, Elie Haddad (elie.haddad@umontreal.ca) or Éric A. Cohen (eric.cohen@ircm.qc.ca).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The authors are willing to share the data upon request. There is no code.

Study approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Center Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) Sainte-Justine institutional (CER #2126) and the CSSS Jeanne Mance review boards (Montreal, Canada), and was performed in accordance with federal and provincial laws. Human tissues were obtained following written informed consent to participate in this study. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by each institution’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IRCM, 2015-11 & 2018-06 and CIBPAR #582 & 593) following Good Laboratory Practices for Animal Research.

Tissue processing

Human autologous fetal thymus and liver were harvested and processed on the same day. The fetal liver was cut into small pieces and shaken at 230 rpm for 30 min at 37°C in a sterile complete RPMI medium (RPMI 1640 + GlutaMAX [Gibco by Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA]) + 10% decomplemented fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco by Life Technologies) and penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) (Wisent, St.-Jean Baptiste, QC, Canada) supplemented with 1 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), DNase I recombinant (Roche by Sigma-Aldrich), and sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich). The suspension was then filtered with a 70-μm cell strainer and washed with Dulbecco’s PBS without calcium or magnesium (dPBS−/−) (Gibco by Life Technologies) with 0.6% citrate phosphate dextrose (Sigma-Aldrich). Hepatocytes were then removed by low-speed centrifugation (18 × g, 5 min) and the supernatant spun again (470 × g, 5 min). Pelleted cells were collected and purified by density centrifugation using Ficoll (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). HSCs were then enriched by using the hCD34 Micro-Bead kit Ultrapure (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). hCD34+ cells were either resuspended in dPBS−/− and kept on ice until injection in mouse or were frozen in FBS + 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Human pediatric thymus tissues were obtained from patients undergoing cardiac surgery (n = 19, age ranges between 1 day and 5 years old; mean age 1 year 2 months, median 6 months) during their stay at CHU Sainte-Justine (Montreal, Canada). Upon reception, the thymus was washed in dPBS−/− and cut into small pieces (around 4–8 mm3). Pieces were either put in culture or frozen in decomplemented human serum type AB (Wisent) +10% DMSO (10–20 pieces/mL) as described by Kalscheuer et al. (2012). When put in culture, pieces were placed on top of a 0.8-μm isopore membrane filter (Sigma-Aldrich), on top of a 1-cm2 absorbable gelatin sponge (Pfizer, Kirkland, QC, Canada) in the presence of F12 medium (Gibco by Life Technologies) + 10% FBS + P/S + Fungizone (Gibco by Life Technologies) + HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich) (Figure 1A). Thymic pieces were kept in culture at 37°C for between 7 and 21 days. The fetal thymus was either used directly for surgery in mice or frozen as described above.

Cord blood CD34+ isolation

Human cord blood was obtained from the Cord Blood Research Bank of the CHU Sainte-Justine under the approval of the CHU Sainte-Justine institutional review board and written informed consent from donors. Mononuclear cells were purified by using SepMate (STEMCELL Technologies, Cambridge, MA, USA) using Ficoll. As described above, HSCs were then enriched by using the hCD34 Micro-Bead kit Ultrapure. hCD34+ cells were kept in culture at 37°C in either RPMI medium with human recombinant stem cell factor at 50 ng/mL (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), human recombinant thrombopoietin (PeproTech), or human recombinant Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (PeproTech) until injection in mice (within 3–6 h of culture), or were frozen in FBS + 10% DMSO.

Human tissue transplantation

NOD/LtSz-scid IL-2Rγc(null) (NSG) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free animal facility of CHU Sainte-Justine Research Center or at the animal core facility of the Montreal Clinical Research Institute. For all models, 6- to 10-week-old NSG mice were conditioned with sublethal (2.5 Gy) total-body irradiation on the day prior to humanization. HumNSG mice were simply injected i.v. with 1 × 105 pooled human cord blood CD34+ cells in 100 μL of dPBS. For BLT mice, human fetal thymus fragments (one per mouse) measuring about 1 mm3 were implanted underneath the recipient kidney capsule. Within 24 h, 3–5 × 105 human autologous fetal liver CD34+ cells in 100 μL of dPBS−/− were injected i.v. For CCST mice, three human pediatric thymus fragments were implanted in the left quadriceps muscle of the mouse and 1–2 × 105 pooled human cord blood CD34+ cells in 100 μL of dPBS were injected i.v. within 3–6 h after the surgery. When mentioned, CD34+ cells were transduced with a lentivirus coding for GFP. In brief, 1 × 105 CD34+ cells isolated from cord blood were plated on RetroNectin-coated wells and transduced with lentiviral particles based on baboon envelope pseudotyped (BaEV-LV) (Girard-Gagnepain et al., 2014) coding for the GFP under the control of the UCOE0.7-SFFV promoter (pHUS-GFP vector) at a multiplicity of infection of 1.4 (Colamartino et al., 2019). After 24 h, cells were harvested, pooled, washed, and injected into mice. All animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and treated with buprenorphine for postoperative pain management, and their drinking water was supplemented with Baytril antibiotic for 10 days post surgery.

Engraftment assessment

The presence of circulating human cells was then evaluated weekly in 50 μL of peripheral blood harvested through the saphenous vein and collected in heparinized tubes. The absolute number and proportion of cell subpopulation was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (Thermo Fisher) along with monoclonal antibodies directed against hCD45 (clone HI30), hCD3 (clone UCHT1), hCD19 (clone HIB19), and hCD14 (clone B159) (all from BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and mCD45 (clone 30-F11) (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Human CD45 percentages are calculated among all CD45+ cells (murine and human). The acquisition was carried out on a BD FACSCanto or FACS LSR Fortessa system (BD Biosciences). Mice were sacrificed when pre-defined limit points were reached. At the time of sacrifice, the thymus (if present), liver, mesenchymal lymph node (if present), blood, and spleen were harvested and evaluated by histopathology and flow cytometry.

Infection of mice and quantification of viral loads

CCST and BLT mice were infected with 200,000 TCID50 of NL4.3-ADA-GFP HIV in 100 μL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium via intraperitoneal injection or vaginal inoculation and monitored for up to 25 weeks depending on experiments. HIV viral load in the plasma of humanized mice was determined weekly using the quantitative COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HIV test, version 2.0 (Roche; detection limit, <20 copies/mL).

ART

Six-week-long daily ART, consisting of emtricitabine (100 mg/kg weight), tenofovir (50 mg/kg), and raltegravir (68 mg/kg), was initiated at usually 6–7 weeks post infection for a group of mice and maintained until sacrifice. The control group was represented by untreated mice.

Nucleic acid extraction and quantification of HIV genomes by real-time PCR

RNAs from spleen cells or other tissues were extracted using an RNeasy Mini plus kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and used as templates for HIV RNA analysis as detailed below. DNA from spleen cells, lung cells, and liver cells were extracted from gDNA eliminator columns using a Qiamp Fast DNA stool mini kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of total HIV DNA, integrated HIV DNA, and unspliced HIV RNA was performed by modified nested real-time PCR assay using Taq DNA polymerase (BioLabs) in the first PCR and TaqMax Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in the second PCR (Vandergeeten et al., 2014). DNA from serially diluted ACH2 cells (NIH AIDS Reagent Program, NIAID, NIH), which contain a single copy of the integrated HIV genome, was extracted and amplified in parallel to generate a standard curve from which unknown samples were enumerated. Human CD3 gene was used as a normalizer.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). Statistical tests applied for each experiment are stated in the legends of figures. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗, and ∗∗∗∗ in the figures signify p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine population size. Randomization was not used.

Author contributions

C.C., Y.L., C.S., W.L., A.B.L.C., and C.T.-L. performed the experiments pertaining to immune reconstitution and function. O.V., T.N.Q.P., and F.D. performed experiments and data analysis related to the HIV work in humanized mice. R.D. recruited participants and collected samples. J.G., N. Patey, S.V., and N. Poirier provided and processed the human tissues. C.C., O.V., K.B., and T.N.Q.P. wrote the manuscript. E.A.C. and E.H. conceptualized the study and wrote the manuscript. E.H. generated the hypotheses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Romas Geleziunas at Gilead Sciences for the gift of emtricitabine and tenofovir and Daria Hazuda at Merck for providing us with raltegravir. We are also grateful to the CHU Sainte-Justine Cord Blood for Research Purpose Biobank. We also thank Jaspreet Jain, Mélanie Laporte, and Oussama Meziane for their experimental support, and the animal and flow cytometry core facilities of the IRCM for their expertise and experimental support. This work was supported through funding from the Fondation Charles-Bruneau, a “Chaire de Recherche Banque de Montreal” from the Fondation Hopital Sainte-Justine to E.H. as well as by a grant supporting the Canadian HIV Cure Enterprise (CanCURE) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (HB2-164064) to E.A.C.. W.L. is supported by a “Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec” (FRQS) scholarship award and A.B.L.C. by a Cole Foundation scholarship award. C.T.-L. is supported by a CIHR scholarship award. E.A.C. is the recipient of the IRCM-Université de Montréal Chair of Excellence in HIV research.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: February 2, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.01.003.

Contributor Information

Éric A. Cohen, Email: eric.cohen@ircm.qc.ca.

Elie Haddad, Email: elie.haddad@umontreal.ca.

Supplemental information

References

- Brainard D.M., Seung E., Frahm N., Cariappa A., Bailey C.C., Hart W.K., Shin H.S., Brooks S.F., Knight H.L., Eichbaum Q., et al. Induction of robust cellular and humoral virus-specific adaptive immune responses in human immunodeficiency virus-infected humanized BLT mice. J. Virol. 2009;83:7305–7321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02207-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.E., Zhou Y., McIntosh B.E., Norman I.G., Lou H.E., Biermann M., Sullivan J.A., Kamp T.J., Thomson J.A., Anagnostopoulos P.V., et al. A humanized mouse model generated using surplus neonatal tissue. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;10:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colamartino A.B.L., Lemieux W., Bifsha P., Nicoletti S., Chakravarti N., Sanz J., Roméro H., Selleri S., Béland K., Guiot M., et al. Efficient and robust NK-cell transduction with baboon envelope pseudotyped lentivector. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2873. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P.K., Kaminski R., Bella R., Su H., Mathews S., Ahooyi T.M., Chen C., Mancuso P., Sariyer R., Ferrante P., et al. Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR treatments eliminate HIV-1 in a subset of infected humanized mice. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2753. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10366-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton P.W., García J.V. Humanized mouse models of HIV infection. AIDS Rev. 2011;13:135–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S., Freitas A.A. Humanized mice: current states and perspectives. Immunol. Lett. 2012;146:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard-Gagnepain A., Amirache F., Costa C., Lévy C., Frecha C., Fusil F., Nègre D., Lavillette D., Cosset F.L., Verhoeyen E. Baboon envelope pseudotyped LVs outperform VSV-G-LVs for gene transfer into early-cytokine-stimulated and resting HSCs. Blood. 2014;124:1221–1231. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-558163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad E., Landais P., Friedrich W., Gerritsen B., Cavazzana-Calvo M., Morgan G., Bertrand Y., Fasth A., Porta F., Cant A., et al. Long-term immune reconstitution and outcome after HLA-nonidentical T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency: a European retrospective study of 116 patients. Blood. 1998;91:3646–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halper-Stromberg A., Lu C.L., Klein F., Horwitz J.A., Bournazos S., Nogueira L., Eisenreich T.R., Liu C., Gazumyan A., Schaefer U., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies and viral inducers decrease rebound from HIV-1 latent reservoirs in humanized mice. Cell. 2014;158:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatziioannou T., Evans D.T. Animal models for HIV/AIDS research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:852–867. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt N., Wang J., Kim K., Friedman G., Wang X., Taupin V., Crooks G.M., Kohn D.B., Gregory P.D., Holmes M.C., Cannon P.M. Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-finger nucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:839–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A., Zheng J.H., Chen K., Dutta M., Chen C., Stiegler G., Kunert R., Follenzi A., Goldstein H. Inhibition of in vivo HIV infection in humanized mice by gene therapy of human hematopoietic stem cells with a lentiviral vector encoding a broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibody. J. Virol. 2010;84:6645–6653. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02339-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalscheuer H., Danzl N., Onoe T., Faust T., Winchester R., Goland R., Greenberg E., Spitzer T.R., Savage D.G., Tahara H., et al. A model for personalized in vivo analysis of human immune responsiveness. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:125ra130. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing C.F., Nixon C.C., Li C., Tsai P., Takata H., Mousseau G., Ho P.T., Honeycutt J.B., Fallahi M., Trautmann L., et al. In vivo suppression of HIV rebound by didehydro-cortistatin A, a “Block-and-Lock” strategy for HIV-1 treatment. Cell Rep. 2017;21:600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan P., Tonomura N., Shimizu A., Wang S., Yang Y.G. Reconstitution of a functional human immune system in immunodeficient mice through combined human fetal thymus/liver and CD34+ cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108:487–492. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.Y., Han A.R., Lee D.R. T lymphocyte development and activation in humanized mouse model. Dev. Reprod. 2019;23:79–92. doi: 10.12717/DR.2019.23.2.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert M.L., Devlin B.H., Chinn I.K., McCarthy E.A., Li Y.J. Factors affecting success of thymus transplantation for complete DiGeorge anomaly. Am. J. Transplant. 2008;8:1729–1736. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert M.L., Devlin B.H., McCarthy E.A. Thymus transplantation. Clin. Immunol. 2010;135:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert M.L., Sarzotti M., Ozaki D.A., Sempowski G.D., Rhein M.E., Hale L.P., Le Deist F., Alexieff M.J., Li J., Hauser E.R., et al. Thymus transplantation in complete DiGeorge syndrome: immunologic and safety evaluations in 12 patients. Blood. 2003;102:1121–1130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura T., Kametani Y., Ando K., Hirano Y., Katano I., Ito R., Shiina M., Tsukamoto H., Saito Y., Tokuda Y., et al. Functional CD5+ B cells develop predominantly in the spleen of NOD/SCID/gammac(null) (NOG) mice transplanted either with human umbilical cord blood, bone marrow, or mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells. Exp. Hematol. 2003;31:789–797. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow W.J., Wharton M., Lau D., Levy J.A. Small animals are not susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 1987;68:2253–2257. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-8-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon C.C., Mavigner M., Sampey G.C., Brooks A.D., Spagnuolo R.A., Irlbeck D.M., Mattingly C., Ho P.T., Schoof N., Cammon C.G., et al. Systemic HIV and SIV latency reversal via non-canonical NF-kappaB signalling in vivo. Nature. 2020;578:160–165. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1951-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebit D.M., Ndembi N., Weinberg A., Quiñones-Mateu M.E. Mucosal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Curr. HIV Res. 2012;10:3–8. doi: 10.2174/157016212799304689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P., Wu G., Baker C.E., Thayer W.O., Spagnuolo R.A., Sanchez R., Barrett S., Howell B., Margolis D., Hazuda D.J., et al. In vivo analysis of the effect of panobinostat on cell-associated HIV RNA and DNA levels and latent HIV infection. Retrovirology. 2016;13:36. doi: 10.1186/s12977-016-0268-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandergeeten C., Fromentin R., Merlini E., Lawani M.B., DaFonseca S., Bakeman W., McNulty A., Ramgopal M., Michael N., Kim J.H., et al. Cross-clade ultrasensitive PCR-based assays to measure HIV persistence in large-cohort studies. J. Virol. 2014;88:12385–12396. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00609-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor Garcia J. Humanized mice for HIV and AIDS research. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016;19:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Terashima K., Ohta S., Horibata S., Yajima M., Shiozawa Y., Dewan M.Z., Yu Z., Ito M., Morio T., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell-engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2Rgamma null mice develop human lymphoid systems and induce long-lasting HIV-1 infection with specific humoral immune responses. Blood. 2007;109:212–218. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen A., Rezek V., Youn C., Lam B., Chang N., Rick J., Carrillo M., Martin H., Kasparian S., Syed P., et al. Targeting type I interferon-mediated activation restores immune function in chronic HIV infection. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:260–268. doi: 10.1172/JCI89488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors are willing to share the data upon request. There is no code.