Abstract

The Escherichia coli rapA gene encodes the RNA polymerase (RNAP)-associated protein RapA, which is a bacterial member of the SWI/SNF helicase-like protein family. We have studied the rapA promoter and its regulation in vivo and determined the interaction between RNAP and the promoter in vitro. We have found that the expression of rapA is growth phase dependent, peaking at the early log phase. The growth phase control of rapA is determined at least by one particular feature of the promoter: it uses CTP as the transcription-initiating nucleotide instead of a purine, which is used for most E. coli promoters. We also found that the rapA promoter is subject to growth rate regulation in vivo and that it forms intrinsic unstable initiation complexes with RNAP in vitro. Furthermore, we have shown that a GC-rich or discriminator sequence between the −10 and +1 positions of the rapA promoter is responsible for its growth rate control and the instability of its initiation complexes with RNAP.

The transcription machinery in Escherichia coli consists of RNA polymerase (RNAP) and RNAP-associated proteins. The RNAP core enzyme is composed of four subunits, α2ββ′, and is capable of transcription elongation and termination at intrinsic terminators. After binding to any of the seven ς factors, the resulting RNAP holoenzyme (α2ββ′ς) is able to initiate transcription at specific sites called promoters in the bacterial chromosome (6, 6a). Several other proteins (NusA, GreA/GreB, and ω) bind core and/or holoenzyme RNAP and modify specific steps of the transcription cycle (1, 4, 9, 10, 13, 17, 34) or facilitate RNAP assembly (23).

Previously, we showed that the RNAP-associated protein RapA (110 kDa) binds both core and holoenzyme RNAP; however, it has a higher affinity to the former (35, 36). The RapA protein is a bacterial homolog of the SWI/SNF helicase-like protein family which is involved in chromatin remodeling and gene expression (39). RapA has ATPase activity that is stimulated by binding to RNAP, indicating that RapA interacts with RNAP both physically and functionally (36). However, RapA has only a marginal effect on transcription in vitro (24, 35), and the role of rapA in transcription has been elusive. The rapA gene (also called hepA) was originally identified downstream of the polB gene, which is controlled by DNA damage (18). However, we have shown that RapA is not likely to be involved in DNA repair (36), contrary to a previous report (24). The rapA promoter and its regulation have never been studied. In the present work we have analyzed the rapA promoter, determined the expression of rapA under different physiological conditions, and studied the interaction between RNAP and the rapA promoter in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The E. coli strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. The basic bacterial techniques used have been described elsewhere (22). The fis::kan allele was moved into different strains by phage P1 transduction with a lysate made from strain RLG1351, and Kanr transductants were selected. Strain DJ2543-47B was constructed in two steps. First the relA251::kan allele was moved into strain DJ2517-C2A by P1 transduction with a lysate made from strain CF1651, and Kanr transductants were selected. Second, the resulting strain was transduced with a P1 lysate made from strain CF4943, and Tetr transductants were selected. Because the spoT203 is linked with the zib563::Tn10 allele at a frequency of approximately 50%, the resulting Tetr colonies were scored for the spoT203 phenotype (small colonies). Note that cells harboring the spoT203 allele and a wild-type relA allele are not viable because the (p)ppGpp synthesized by the RelA protein cannot be degraded by the mutant SpoT protein, resulting in extremely high concentrations of (p)ppGpp (32). In relA251 spoT203 cells, the (p)ppGpp is synthesized from the mutant SpoT protein.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MG1655 | Wild-type E. coli K-12 | Laboratory collection |

| DJ480 | MG1655 lacX74 | Laboratory collection |

| CF1651 | MG1655 relA251::kan | 29 |

| CF4943 | MG1655 galK2 relA251::kan zib563::Tn10 spoT203 | 40 |

| RLG1351 | MG1655 lacX74 fis::kan λ rrnBpI (+88 to +1)::lacZ | 39 |

| DJ2517-C2A | DJ480 λ rapA (−211 to +77)::lacZ | This work |

| DJ2611-C1 | DJ480 λ rapA (−57 to +77)::lacZ | This work |

| DJ2611-C2 | DJ480 λ rapA (−36 to +77)::lacZ | This work |

| DJ2524-13E | DJ2517-C2A fis::kan | This work |

| DJ2621A | DJ2611-C1 fis::kan | This work |

| DJ2611-A1 | DJ480 λ rapA (−211 to +77; +1C→A)::lacZ | This work |

| DJ2543-47B | DJ2517-C2A relA251::kan zib563::Tn10 spoT203 | This work |

| DJ2611-B1 | DJ480 λ rapA (−211 to +77; discriminator mutant)::lacZ | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSA508 | pBR322-based vector | 10 |

| pDJ760 | rapA (−221 to +415) in vector pSA508 | This work |

| pDJ2506 | rapA (−221 to +77) in vector pSA508 | This work |

| pDJ2512 | rapA (−221 to +77; discriminator mutant) in vector pSA508 | This work |

Chemicals and reagents.

Nucleotides and 32P-labeled nucleotides were purchased from Amersham. Chemicals were from Sigma. RNAP was purified from strain MG1655 as described previously (14). Antibodies against RapA and RNAP have been described previously (35). The Fis protein was a gift from R. Johnson (University of California—Los Angeles).

Construction of lacZ fusions.

All lacZ fusions reported in this work were introduced into strain DJ480 as λ phage monolysogens. Vectors and methods were as described previously (33). Briefly, DNA fragments containing the rapA promoter were synthesized by PCR and cloned into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of the vector pRS415. The resulting plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing and recombined in vivo with the λRS45 phage. Blue recombinant phage plaques were purified twice for each fusion, and the resulting phages were used to obtain lysogens using E. coli DJ480 as host cells. Single-prophage integration was confirmed by PCR amplification as described previously (29).

Bacterial growth and β-galactosidase measurements.

All cultures were grown with vigorous agitation in a water bath at 37°C. For time course experiments, a fresh overnight culture was diluted 1/100 into fresh medium. For growth rate experiments, cells were grown in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) medium (25) supplemented with either 0.2% (vol/vol) glycerol or 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose, with or without 0.8% Difco Casamino Acids plus 50 μg of tryptophan/ml, or in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Growth was monitored by measuring the A600, and growth rates were calculated using the slopes of the growth curves.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (44). Culture aliquots were lysed in a microtiter plate and exposed to the chromogenic substrate o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG). Kinetic measurements were made using a SpectraMax 250 microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices) to obtain the Vmax. Units were presented as specific activities, which were calculated by dividing the Vmax by the A600 of the culture and then multiplying by 25. The specific activities thus obtained have been empirically determined to correspond with the standard Miller units. For each culture, triplicate samples were taken at each time course and results were expressed as the means of the three measurements. The standard deviations of the triplicates were less than 5%. In time course experiments where two or more strains were compared, duplicate cultures were assayed for each strain on the same day. The variations between the culture duplicates were less than 10%. Each set of experiments was repeated at least three times, and the differences between repetitions were less than 10%. For the growth rate experiments in each different medium, a whole time course covering different growth phases was performed. The maximal activity obtained at each growth rate was plotted as a function of growth rate.

Cloning and DNA manipulations.

All DNA manipulations and cloning techniques were carried out as described elsewhere (20). PCR amplifications were carried out using the High Fidelity Expand system (Roche). Sequencing was performed on a Genetic Analyzer using the d-rhodamine terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (both from Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems Division) according to the manufacturer's specifications.

All plasmids used in the in vitro transcription reactions were constructed by inserting PCR products (digested with the EcoRI and PstI restriction enzymes) into the EcoRI-PstI sites of plasmid pSA508, which contained a very strong Rho-independent terminator downstream of the two restriction sites (7). For PCRs, genomic DNA (MG1655) was used as the DNA template except as mentioned otherwise. The DNA sequences of the two primers used for the insert in plasmid pDJ760 were 5′-AGATCGAATTCGAATTCGGCCCGGAGCCGCTGGACTACCAACGTT (primer DJ144, upper strand) and 5′-CATGGCTGGTATGGTATCTGCAGGGTTGAACACGCGGTCA (lower strand). The two primers used for the insert in plasmid pDJ2506 were primers DJ144 and RAPATGPST (5′-ACCAAGTGTAACTGCAGATGTTGTTCGGGTCTATATCT). The insert in plasmid pDJ2512 containing the discriminator mutations was obtained in two steps. First, two independent DNA fragments (A and B) which share complementary sequence in the discriminator region were each amplified by PCR. The primers used to amplify fragment A were DJ144 for the upper strand and JC107H (5′-TCAGGTCCAGGAATGGAAAGGAATTTATGGTACTGGATG) for the lower strand. The primers used to amplify fragment B were JC107G (5′-GCCATCCAGTACCATAAATTCCTTTCCATTCCTGGACCTGA-3′) for the upper strand and RAPATGPST for the lower strand. Primers JC107G and JC107H are partially complementary and have mutations in the discriminator region (underlined in the above sequences). The second step was a PCR amplification with primers DJ144 and RAPATGPST and a mixture of fragments A and B as the DNA template.

Primer extension analysis.

Total RNA from E. coli cells and in vitro transcription reactions was isolated using an RNeasy kit from Qiagen according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer extension reactions were carried out with the avian myeloblastosis virus primer extension kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Using plasmid pDJ760 as the DNA template, the same primer used in the primer extension assays was used to generate the DNA sequencing ladder for mapping the transcription start points.

In vitro transcription assays.

Reactions were carried out essentially as described previously (43). Transcription reactions were carried out at ∼24°C in final volumes of 20 μl containing 2 to 3 nM concentrations of DNA templates and 25 nM RNAP. RNAP and DNA templates were preincubated for 15 min, and reactions were started by addition of nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) (0.2 mM for ATP, GTP, and CTP, and 0.02 mM for UTP, including about 5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP). Where indicated, heparin (100 μg/ml) was added with the NTPs to restrict transcription to a single round by binding to free RNAP molecules. After 15 min, reactions were stopped and products were analyzed on an 8% sequencing gel, followed by autoradiography. In the experiments where the kinetics of inactivation of open complexes were analyzed, heparin was added after preincubation of RNAP and the DNA template (time zero). At the times indicated after addition of the inhibitor, NTPs were added, and reactions were allowed to continue for 15 min before being stopped and analyzed as described above. Data were quantified with an ImageQuant PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Mapping the transcription start site of rapA.

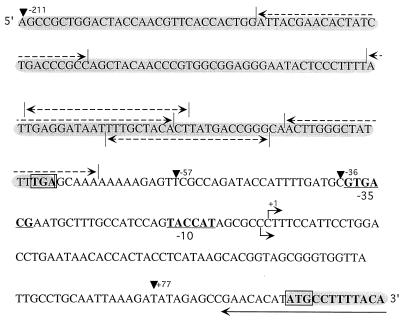

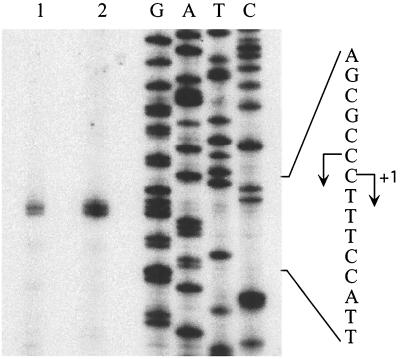

To identify the transcription start point of the rapA gene, we carried out primer extension analysis using a radiolabeled oligonucleotide that hybridizes with the translation initiation region of rapA mRNA (Fig. 1). We purified total RNA from E. coli MG1655 cells harboring plasmid pDJ760, which contains the promoter/regulatory region of rapA (Table 1), and from in vitro transcription reactions using plasmid pDJ760 as the template. In both cases, we found that the start sites of the rapA gene were at two cytosine residues located 94 and 95 bp upstream from the initiation codon ATG (Fig. 2). We also performed primer extension analysis using RNA purified from MG1655 cells and identified the same transcription start points, although the signals were very weak (data not shown). Thus, we have identified the transcription start points of the rapA gene and defined the second cytosine residue as the +1 position (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the rapA promoter. The coding regions of the polB and rapA genes are shaded. The translation initiation codon (ATG) for the RapA protein and the translation termination codon for the upstream gene polB (TGA) are boxed. The −10 and −35 regions of the rapAp are underlined, and the two transcription start points are indicated by bent arrows. The solid arrow indicates the oligonucleotide used in the primer extension experiments. Dashed arrows indicate the positions of the Fis binding sites predicted by the information theory algorithm (16); all predicted sites had scores between 3 and 7. Arrowheads show the boundaries of the transcriptional fusions used in this work.

FIG. 2.

Mapping the transcription start points of the rapA gene. Primer extension reactions were carried out with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide that hybridizes near the ATG region and 100 μg of total RNA from E. coli MG1655 cells harboring the pDJ760 plasmid (lane 1) or RNA from an in vitro transcription reaction with the pDJ760 plasmid as the template (lane 2). DNA sequencing reactions were carried out with the same labeled oligonucleotide (lanes G, A, T, and C) and electrophoresed in parallel on 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels. The sequence on the right corresponds to the nontemplate strand.

The rapA promoter is growth phase dependent.

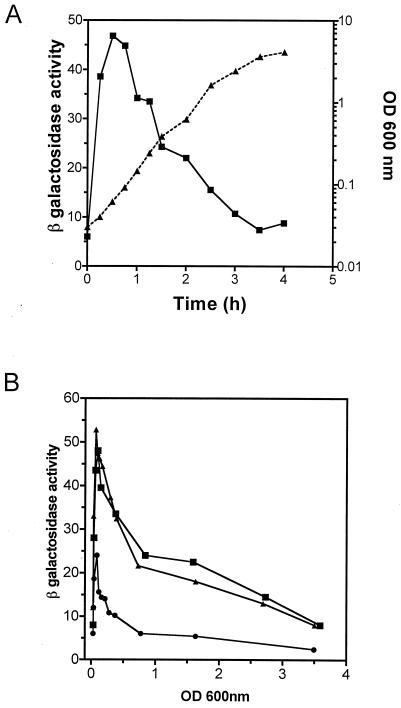

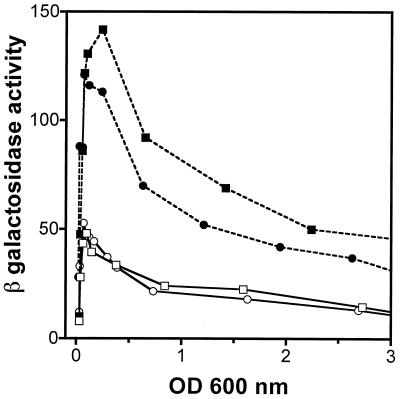

To study the rapA promoter activity in vivo, we fused the rapA promoter region (−211 to +77 [Fig. 1]) with the promoterless lacZ gene, followed by integration of this fusion in a single copy into the E. coli chromosome, resulting in strain DJ2517-C2A. Thus, expression of rapA could be monitored by β-galactosidase activity. First, we determined the expression of rapA as a function of cell growth (Fig. 3A). We found that rapA activity increased dramatically during the first doubling time after cultures were diluted in fresh medium. The peak of promoter activity was reached approximately during the first 30 to 45 min of growth. As cells continued to grow, however, the activity decreased, and it became minimal during the stationary phase. It should be noted that there are limitations in using the rapA-lacZ fusion to monitor rapA promoter activity due to the stability of β-galactosidase, levels of which are reduced in the cell only due to growth and dilution. Thus, our data suggest that after a burst of synthesis of rapA during the early log phage, the expression of rapA is essentially shut off, as the reduction of β-galactosidase activity can be explained by the growth and dilution of the cell in the cultures. Apparently, this expression pattern is specific for the rapA promoter, because the β-galactosidase activity expressed from several other promoters (λpL, lacUV5, and dsrA) exhibited no such expression pattern, as reported recently (30). We conclude from this experiment that rapA promoter activity is growth phase dependent.

FIG. 3.

rapA promoter activity is growth phase dependent. (A) DJ2517-C2A cells carrying a fusion between rapA (positions −211 to +77) and the lacZ gene were grown in LB medium at 37°C and monitored for both growth, expressed as optical density (OD) (triangles), and β-galactosidase activity (squares). (B) β-Galactosidase activity expressed from different fusions as a function of growth. Cells carrying positions −211 to +77 (strain DJ2517-C2A) (squares), −57 to +77 (strain DJ2611-C1) (triangles), or −36 to +77 (strain DJ2611-C2) (circles) of the rapA promoter region fused to the lacZ gene were grown in LB medium at 37°C. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. No significant differences in the growth rate were detected among the different fusions.

To define the sequences of the rapA promoter that are sufficient to maintain the promoter activity and the expression pattern observed above, we constructed two other, similar lacZ fusions with shorter upstream sequences of the rapA promoter region and determined the β-galactosidase activities of these fusions similarly. One fusion (DJ2611-C1), containing residues −57 to +77 of the rapA promoter (Fig. 3B), was almost indistinguishable from the DJ2517-C2A fusion containing residues −211 to +77 (Fig. 3B). This indicates that the determinants that provide both full promoter activity and growth phase regulation are located in the −57-to-+77 region. Another fusion (DJ2611-C2), containing residues −36 to +77 of the rapA promoter (Fig. 3B), still exhibited growth phase dependence for the expression of rapA, although it had only about half the peak activity of DJ2517-C2A. Together, these results indicate that residues −57 to −36 are required for full promoter activity and that the minimal promoter region from −36 to +77 is sufficient to provide growth phase regulation.

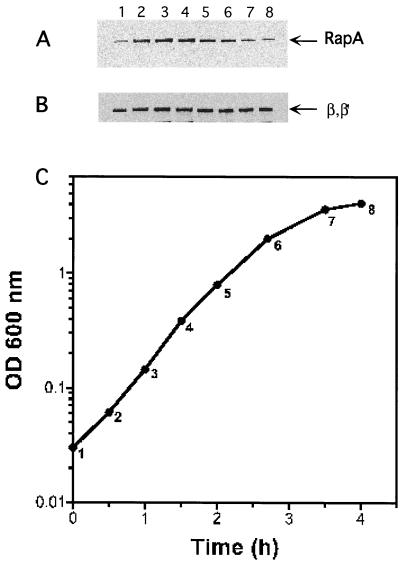

To address whether the growth phase regulation of rapA is also reflected in RapA protein levels, we determined RapA protein levels as a function of cell growth by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antibodies against RapA (Fig. 4). We found that RapA levels also increased dramatically during the first half-hour after cultures were diluted in fresh medium, reached maximal levels after 1 h, and then decreased and became minimal in the late-stationary phase (Fig. 4A). As a control, we probed the same samples in a parallel Western blot using an antibody against core RNAP. We found that the levels of the β and β′ subunits remained almost constant during different growth phases (Fig. 4B). At present, we do not know why there is a difference between the times of highest promoter activity (30 to 45 min) and peak protein accumulation (1 h). We speculate that it may be due to differences between the half-lives of the lacZ and rapA transcripts and/or differences between the translation efficiency of the β-galactosidase and RapA proteins. We conclude that RapA protein levels correlate reasonably well with promoter activity.

FIG. 4.

RapA levels as a function of cell growth. A culture of E. coli MG1655 cells was monitored for growth in LB medium at 37°C by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm (C). At the times indicated by the numbers along the curve, samples were taken and concentrated by centrifugation. Each sample was used in Western blot analyses with polyclonal antisera against RapA (A) and core RNAP (B). The same amount of cells (normalized using the OD at 600 nm) was loaded in each lane.

The growth phase regulation of rapA is independent of Fis.

Because the Fis protein also increases dramatically immediately after cultures are diluted in fresh medium (26), in a manner very similar to that of RapA described above, we asked if Fis was responsible for the growth phase regulation of rapA. Thus, we measured the expression of rapA in fis mutant cells and found that the rapA activity was still growth phase dependent, like that in the wild-type isogenic cells (Fig. 5). Interestingly, promoter activities were more than twofold higher in the fis cells than in wild-type cells. Taken together, our results suggest that Fis negatively regulates rapA but is not involved in the growth phase regulation of the rapA promoter.

FIG. 5.

rapA promoter activity in fis cells. β-Galactosidase activity expressed from the rapA-lacZ fusions in fis (solid symbols) and wild-type (open symbols) backgrounds is shown as a function of growth (expressed as optical density [OD] at 600 nm). Cells carrying fusions of −211 to +77 (strains DJ2517-C2A [open squares] and DJ2524-13E [solid squares]) or −57 to +77 (strains DJ2611-C1 [open circles] and DJ2621A [solid circles]) were grown in LB medium at 37°C. No significant differences in the growth rate were detected between isogenic strains.

To account for the negative effect of Fis on the expression of rapA, we searched for putative Fis binding sites in the promoter region using an information theory algorithm (16). We identified several potential Fis binding sites in the rapA promoter region (Fig. 1). However, compared to the well-known Fis binding sites in the ribosomal promoter rrnB P1, which have high scores between 10 and 15 by the algorithm indicating strong binding (16), the putative Fis binding sites in the rapA promoter are weak, with low scores ranging from 3 to 7. The results from gel shift assays with purified Fis and DNA fragments containing the Fis binding sites of the rapA and rrnB P1 promoters were consistent with the prediction (data not shown). However, we do not believe that these Fis binding site are responsible for the observed negative effect of Fis on the expression of rapA for the following two reasons. (i) All the predicted Fis binding sites in the rapA promoter region are located upstream of the nucleotide at −57 (Fig. 1). However, the promoter fusion (−57 to +77) lacking these putative binding sites (or any other putative Fis binding sites in the vector sequences upstream of the −57 position) still showed the negative effect of Fis on the promoter (Fig. 5). (ii) Purified Fis had no effect on RNA synthesis from the rapA promoter containing the Fis binding sites by in vitro transcription assays (data not shown). It is very likely that the in vivo negative effect of Fis on the expression of the promoter is indirect.

A mutation at the transcription start site alters the growth phase response of rapA.

Since both the rapA and fis promoters are subject to growth phase regulation, we analyzed the DNA sequences of the two promoters to determine if there is any similarity between them. Indeed, we found that some sequences near the initiation sites are conserved between the two promoters (Fig. 6A). In particular, both of the promoters use C as the transcription-initiating nucleotide. This is unlike most E. coli promoters, which have purines (A or G) for starting sites (15, 19). It has been reported that a fis promoter mutation that has replaced C with A in the transcription start point results in sustained activity, even during later growth phases (41). We asked if a similar mutation in the rapA promoter could also affect its growth phase regulation. Thus, we constructed a fusion containing a mutant rapA promoter with the +1 nucleotide altered from C to A, and we measured the β-galactosidase activity expressed from the mutant promoter (Fig. 6B). Indeed, in contrast to the wild-type promoter, the mutant rapA promoter showed higher activities in samples with optical densities higher than 0.3. This is similar to results for the mutant fis promoter mentioned above. Our results indicate that the presence of nucleotide C at the transcription start point of rapA is important for growth phase regulation.

FIG. 6.

A mutation in the transcription start point modifies the growth phase response of the rapA-lacZ fusion. (A) Sequence alignment of the transcription initiation regions of the rapA gene and the fis gene. The −10 and −35 regions are underlined. (B) β-Galactosidase activity expressed from the wild-type rapA promoter (strain DJ2517-C2A) (squares) and a mutant promoter with the +1 nucleotide changed to an A (strain DJ2611-A1) (triangles) as a function of growth (expressed as optical density [OD] at 600 nm). Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C, and no significant differences in the growth rate were detected between the two strains.

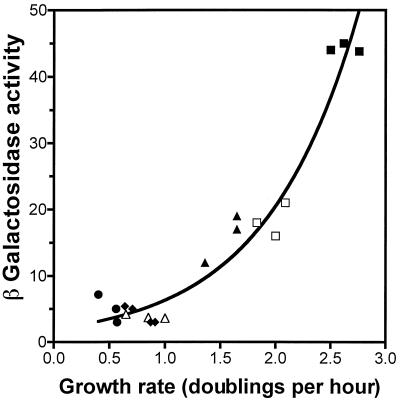

The rapA promoter is subject to growth rate regulation.

Note that between the −10 and +1 positions in the rapA promoter (Fig. 1) there is a GC-rich sequence called a “discriminator region” (37). Certain promoters that have a discriminator region are under growth rate-dependent control (8, 38, 42). To determine if rapA expression is subject to growth rate regulation, we performed the following two sets of experiments. First, we measured the β-galactosidase activity expressed from the rapA promoter at different growth rates by varying the richness of the growth medium. We found that the expression of rapA always peaked at or around the first doubling time after cultures were diluted in fresh medium (data not shown), although the values at peaks were different for different growth media. We then plotted the β-galactosidase activities at the peak expressions versus the growth rates in different growth media (Fig. 7). The wild type rapA::lacZ fusion showed an increase of approximately 10-fold in promoter activity when the growth rate was increased from 0.6 to 2.7 doublings per h. This result indicates that rapA is under growth rate control.

FIG. 7.

rapA promoter activity is growth rate dependent. β-Galactosidase activity expressed from the wild-type rapA promoter in wild-type (strain DJ2517-C2A) (solid symbols) and relA251 spoT203 (strain DJ2543-47B) (open symbols) backgrounds is plotted as a function of growth rate. Cells were grown in the following media: LB (squares), glucose Casamino Acids (triangles), glucose minimal (diamonds), and glycerol minimal (circles). Because rapA promoter activity was growth phase dependent, time course experiments were carried out in each medium and the maximal activity obtained during the early-logarithmic phase was plotted.

Next we determined the rapA promoter activity in a relA251 spoT203 strain that has higher than normal levels of intracellular (p)ppGpp and reduced growth rates compared to that of the isogenic wild-type strain in a given medium (32). For example, the growth rates in LB medium were 2.5 and 2.0 doublings per h for the wild-type strain and the relA251 spoT203 mutant, respectively, whereas in glucose plus Casamino Acids medium, the growth rates were 1.5 and 1.0 doublings per h for wild-type and mutant cells, respectively. We found that β-galactosidase activity expressed from rapA in the relA251 spoT203 mutant was also a function of the growth rate, independent of growth medium: an approximately fourfold increase in promoter activity was observed when the growth rate was increased from about 1.0 to 2.0. Importantly, the β-galactosidase activities expressed from the rapA promoter in the relA251 spoT203 mutant at different growth rates fitted very well in the same curve obtained for the wild-type strain (Fig. 7). Thus, our results demonstrate that similar rapA promoter activities are obtained at a given growth rate regardless of how that particular growth rate is achieved.

Mutations in the discriminator region reduce the growth rate dependence of the rapA gene.

To determine if the discriminator region of rapA is important for growth rate regulation, we constructed a strain containing a derivative of the rapA::lacZ fusion that replaced the GC-rich sequence with an AT-rich sequence between the −10 and +1 positions in the rapA promoter (Fig. 8A). We determined the β-galactosidase activity from the mutant rapA promoter in cells growing at different growth rates and found that the mutant promoter had significantly reduced sensitivity to the growth rate compared to that of the wild-type promoter (Fig. 8B). We conclude that the discriminator region of rapA is important for growth rate control.

FIG. 8.

A mutation in the discriminator region reduces the growth rate dependence of rapA promoter activity. (A) Comparison between the sequences of the wild-type rapA promoter (WT) and the discriminator mutant (D) promoter. Mutant nucleotides in the discriminator mutant promoter sequence are shaded. (B) β-Galactosidase activity expressed from the discriminator mutant rapA promoter as a function of growth rate (strain DJ2611-B1) (solid symbols). Cells were grown in the following media: LB (squares), glucose Casamino Acids (triangles), and glucose minimal (diamonds). Because rapA promoter activity was growth phase dependent, time course experiments were carried out in each medium and the maximal activity obtained during the early-logarithmic phase was plotted. β-Galactosidase expression from the wild-type rapA promoter as a function of the growth rate is also shown for comparison (asterisks).

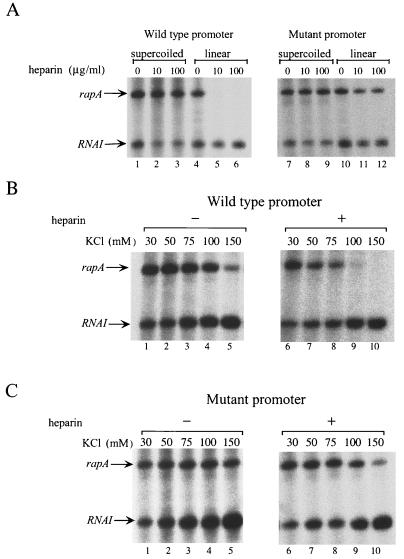

The complexes between RNAP and the rapA promoter are intrinsically unstable.

Another important feature of promoters containing a discriminator region is that they form intrinsically unstable complexes with RNAP during initiation (27, 28). Such a feature has been suggested as a regulatory step in gene regulation (43). To determine if the interaction between RNAP and the rapA promoter is also intrinsically unstable, we first cloned the wild type rapA promoter in front of a very strong simple terminator so that the transcript from the promoter could be synthesized on either a supercoiled or a linear DNA template. Then we analyzed RNA synthesis from the rapA promoter by in vitro transcription assays under different conditions which were known to affect the stability of initiation complexes (Fig. 9). In these experiments, the RNAI transcript from the same plasmid was used as a control. Indeed, as expected, transcription from the rapA promoter was very sensitive to supercoiling (Fig. 9A). Synthesis of the rapA transcript on a linear template was reduced compared to synthesis from a supercoiled template (Fig. 9A; compare lanes 4 and 1). Moreover, synthesis of the rapA transcript from a linear template was totally eliminated when the DNA competitor heparin was added at the same time as the NTPs (Fig. 9A; compare lanes 5 and 6 to lanes 2 and 3). In addition, even with supercoiled DNA, synthesis of rapA was very sensitive to the salt concentration (Fig. 9B, lanes 1 to 5), and the salt effect was further exaggerated in the presence of the DNA competitor heparin (Fig. 9B, lanes 6 to 10). Furthermore, the half-life of initiation complexes of the rapA promoter on supercoiled DNA was about 1 min (Fig. 10), whereas the half-life of initiation complexes of the RNAI promoter was longer than 30 min (Fig. 10). We concluded from these experiments that the interaction between RNAP and the rapA promoter is indeed very unstable.

FIG. 9.

In vitro transcription assays of the wild-type and discriminator mutant rapA promoters. Reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Where not otherwise indicated, the transcription buffer contained 50 mM KCl and the heparin concentration was 100 μg/ml. Arrows indicate the positions of the rapA and RNAI transcripts. (A) Effects of supercoiling and heparin on transcription. (B) Effects of salt concentration and heparin on transcription from the wild-type rapA promoter in a supercoiled DNA template. (C) Effects of salt concentration and heparin on transcription from the discriminator mutant rapA promoter in a supercoiled DNA template.

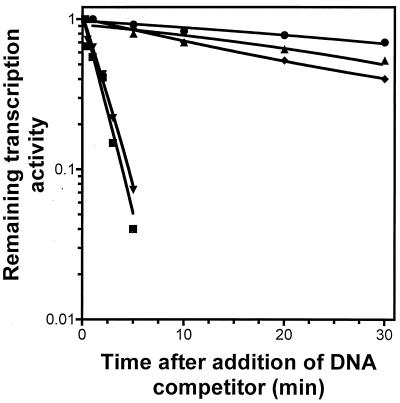

FIG. 10.

Determining the stability of initiation complexes of the rapA promoter with RNAP. The experiment was performed with 50 mM KCl in the presence of heparin (100 μg/ml) as described in Materials and Methods. Transcription activities from the wild-type and discriminator mutant rapA promoters were plotted as functions of time after inhibitor addition. Circles, RNAI promoter; squares, wild-type rapA promoter; diamonds, wild-type rapA promoter in the presence of 2 mM CTP; triangles, discriminator mutant rapA promoter; inverted triangles, wild-type rapA promoter in the presence of 2 mM ATP.

The discriminator region of rapA is important for the instability of complexes between RNAP and the promoter.

To analyze the effect of the discriminator region of rapA on the stability of initiation complexes with RNAP, we replaced the wild-type rapA promoter with the discriminator mutant promoter (Fig. 8A) and performed in vitro transcription assays under the conditions described above (Fig. 9). In contrast to the wild-type rapA promoter, RNA synthesis from the mutant promoter became insensitive to supercoiling and was competent on linear DNA even in the presence of heparin (Fig. 9A; compare lanes 11 and 12 to lanes 5 and 6). Furthermore, compared to that from the wild-type promoter, RNA synthesis from the mutant promoter on a supercoiled DNA template was more resistant to high salt concentrations both in the absence and in the presence of a DNA competitor (compare Fig. 9C, lanes 5 and 7 to 10, with Fig. 9B, lanes 5 and 7 to 10). These results indicate that the initiation complexes of the mutant rapA promoter were more stable than those of the wild-type promoter. Indeed, we determined the half-life of the complexes of the mutant rapA promoter and found that it was about 28 min, approximately 28-fold longer than that for the wild type promoter (Fig. 10). We concluded that the GC-rich sequence in the discriminator region of rapA is important for the instability of complexes between RNAP and the promoter.

The initiation nucleotide stabilizes the initiation complexes at the rapA promoter.

Gaal et al. (11) have shown that the extremely unstable complexes between the ribosomal promoter rrnB P1 and RNAP can be stabilized by increasing the concentration of the initiating nucleotide ATP. Because the complexes between the rapA promoter and RNAP are also unstable, we determined the effect of increasing the concentration of the initiating nucleotide CTP on the stability of initiation complexes at the rapA promoter. While the interaction between RNAP and the rapA promoter was extremely unstable in the presence of 0.2 mM CTP (half-life of initiation complex, about 1 min [Fig. 10]), it became stabilized with 2 mM CTP (half-life of initiation complex, 21 min [Fig. 10]). However, the stability of the complexes between RNAP and the rapA promoter was not affected in the presence of 2 mM ATP, a nucleotide that cannot be used for transcription initiation at the rapA promoter (Fig. 10). We concluded that the initiating nucleotide CTP stabilizes the complexes between RNAP and the rapA promoter.

DISCUSSION

We have studied the rapA promoter and its regulation in vivo and determined the interaction between RNAP and the promoter in vitro. We found that the transcription starting site for the rapA gene is C, a rare starting nucleotide for promoters in E. coli. Interestingly, the expression of rapA is growth phase dependent, peaking at the early log phase. In addition, the rapA promoter is subject to growth rate regulation in vivo, and it forms intrinsically unstable initiation complexes with RNAP in vitro.

Growth rate regulation.

A well-characterized growth rate-regulated promoter is the ribosomal promoter rrnB P1 (3, 12). As demonstrated in this paper, the rapA and rrnB P1 promoters share the following properties: (i) they are under growth rate-dependent control, (ii) they each have a discriminator sequence, and (iii) they form intrinsically unstable initiation complexes with RNAP. These similarities suggest that these two promoters may also share some mechanisms of regulation. Since rrnB P1 is subject to the stringent response, it is possible that the rapA promoter may be controlled by the stringent response as well. Consistent with this hypothesis, rapA promoter activities in cells that contain higher than normal levels of (p)ppGpp (the relA251 spoT203 strain) were two- to threefold lower than those in the wild-type strain (Fig. 7). Further experiments are warranted to determine whether the rapA promoter is regulated by the stringent response. Also, it has been suggested that modulation of the stability of initiation complexes at the rrnB P1 promoter and other similar promoters is a key regulatory step in transcription of the promoters (43). Interestingly, we found that a mutation in the discriminator region of the rapA promoter stabilizes the complexes with RNAP and renders the promoter insensitive to growth rate changes. This suggests that (i) the discriminator region of rapA is important for its growth rate control and (ii) modulation of the stability of initiation complexes at the rapA promoter is also an important element for the regulation of the promoter.

Growth phase regulation.

To the best of our knowledge, only a few genes, such as fis (41), cspA (5), and nuoA (40), have been reported to be preferentially expressed during early-log-phase growth. These genes can be divided into two groups: one group of genes, including rapA and fis, that contain a GC-rich or discriminator sequence between −10 and +1 in the promoter region and use C as the initiating nucleotide, and another, such as cspA and nuoAN, that lack such features in the promoter region.

Consequently, there is at least a similarity in the regulation of the rapA and fis promoters. It has been demonstrated that the initiation nucleotide C is an important element in determining growth phase control for the two promoters. The biological significance of this feature is speculative at present. It has been reported that among the four ribonucleotides in E. coli, the concentration of CTP is reported to be the lowest in the cell (21). In addition, it has been shown that CTP is a very poor initiating nucleotide compared to ATP and GTP (2). It is conceivable that the cellular CTP concentration is relatively high when E. coli just starts its growth at very early log phase and becomes reduced with more cell growth as synthesis of rRNA, tRNA, and others consume the NTP pool inside the cell. Because of the intrinsic instability of the complexes between RNAP and the rapA promoter, it is plausible that the concentration of CTP will modulate the stability of initiation complexes at the promoter and thus its transcription activity. We have shown that this is the case for the rapA promoter (Fig. 10). We predict that it is very likely to be the case for the fis promoter as well.

At present we do not know the biological significance of the pattern of rapA promoter activity: why it is highest at early log phase and with the fastest growth. It is relatively clear that the early-logarithmic-phase expression of Fis could be important for rapid adaptation of the cell for fast growth, because this protein affects the expression of a variety of genes; in particular, it activates transcription from the ribosomal promoters (31). Recently, we have found that RapA greatly activates transcription by stimulating RNAP recycling in vitro (M. V. Sukhodolets, J. E. Cabrera, and D. J. Jin, unpublished data). We speculate that the amount of available RNAP inside the cell is limiting during early-log-phase growth (after stationary phase) and that thus a peak level of RapA will facilitate RNAP recycling (in particular for a high growth rate), which in turn enhances transcription activity. We are currently testing this hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Thomas D. Schneider for prediction of Fis binding sites in the rapA promoter using the information theory algorithm. We are also grateful to John Lydon for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman C R, Solow-Cordero D E, Chamberlin M J. GreA-induced transcript cleavage in transcription complexes containing Escherichia coli RNA polymerase is controlled by multiple factors, including nascent transcript location and structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3784–3788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony D D, Goldthwait D A, Wu C W. Studies with the ribonucleic acid polymerase. II. Kinetic aspects of initiation and polymerization. Biochemistry. 1969;8:246–256. doi: 10.1021/bi00829a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett M S, Gourse R L. Growth rate-dependent control of the rrnBp1 core promoter in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5560–5564. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5560-5564.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borukhov S, Sagitov V, Goldfarb A. Transcript cleavage factors from E. coli. Cell. 1993;72:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandi A, Spurio R, Gualerzi C O, Pon C L. Massive presence of the Escherichia coli ‘major cold-shock protein’ CspA under non-stress conditions. EMBO J. 1999;18:1653–1659. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess R R, Erickson B, Gentry D, Gribskov M M, Hager D, Lesley S, Strickland M, Thompson N. RNA polymerase and the regulation of transcription. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science Publishing; 1987. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Burgess R R, Travers A A, Dunn J J, Bautz E K. Factor stimulating transcription by RNA polymerase. Nature. 1969;221:43–46. doi: 10.1038/221043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choy H E, Adhya S. Control of gal transcription through DNA looping: inhibition of the initial transcribing complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11264–11268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies I J, Drabble W T. Stringent and growth-rate-dependent control of the gua operon of Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology. 1996;142:2429–2437. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng G H, Lee D N, Wang D, Chan C L, Landick R. GreA-induced transcript cleavage in transcription complexes containing Escherichia coli RNA polymerase is controlled by multiple factors, including nascent transcript location and structure. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22282–22294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman D I, Gottesman M. Lytic mode of lambda development. In: Hendrix R W, Roberts J W, Stahl F W, Weisberg R A, editors. Lambda II. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1983. pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaal T, Bartlett M S, Ross W, Turnbough C L, Jr, Gourse R L. Transcription regulation by initiating NTP concentration: rRNA synthesis in bacteria. Science. 1997;278:2092–2097. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gourse R L, Gaal T, Bartlett M S, Appleman J A, Ross W. rRNA transcription and growth rate-dependent regulation of ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:645–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenblatt J, Li J. Interaction of the sigma factor and the nusA gene protein of E. coli with RNA polymerase in the initiation-termination cycle of transcription. Cell. 1981;24:421–428. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hager D A, Jin D J, Burgess R R. Use of Mono-Q high-resolution ion-exchange chromatography to obtain highly pure and active Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7890–7894. doi: 10.1021/bi00486a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harley C B, Reynolds R P. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hengen P N, Bartram S L, Stewart L E, Schneider T D. Information analysis of Fis binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4994–5002. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu L M, Vo N V, Chamberlin M J. Escherichia coli transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB stimulate promoter escape and gene expression in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11588–11592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis L K, Jenkins M E, Mount D W. Isolation of DNA damage-inducible promoters in Escherichia coli: regulation of polB (dinA), dinG, and dinH by LexA repressor. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3377–3385. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3377-3385.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Turnbough C L., Jr Effects of transcriptional start site sequence and position on nucleotide-sensitive selection of alternative start sites at the pyrC promoter in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2938–2945. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2938-2945.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathews C K. Biochemistry of deoxyribonucleic acid-defective amber mutants of bacteriophage T4. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:7430–7438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee K, Chatterji D. Studies on the omega subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase—its role in the recovery of denatured enzyme activity. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:884–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muzzin O, Campbell E A, Xia L, Severinova E, Darst S A, Severinov K. Disruption of Escherichia coli hepA, an RNA polymerase-associated protein, causes UV sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15157–15161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsson L, Verbeek H, Vijgenboom E, van Drunen C, Vanet A, Bosch L. FIS-dependent trans-activation of stable RNA operons of Escherichia coli under various growth conditions. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:921–929. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.921-929.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pemberton I K, Muskhelishvili G, Travers A, Buckle M. The G/C-rich discriminator region of the tyrT promoter antagonises the formation of stable preinitiation complexes. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:859–864. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pokholok D K, Redlak M, Turnbough C L, Dylla S, Holmes W M. Multiple mechanisms are used for growth rate and stringent control of leuV transcriptional initiation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5771–5782. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5771-5782.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell B S, Rivas M P, Court D L, Nakamura Y, Rivas M P, Turnbough C L., Jr Rapid confirmation of single copy lambda prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5765–5766. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Repoila F, Gottesman S. Signal transduction cascade for regulation of RpoS: temperature regulation of DsrA. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4012–4023. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.4012-4023.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross W, Thompson J F, Newlands J T, Gourse R L. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 1990;9:3733–3742. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarubbi E, Rudd K E, Cashel M. Basal ppGpp level adjustment shown by new spoT mutants affect steady state growth rates and rrnA ribosomal promoter regulation in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;213:214–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00339584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparkowski J, Das A. Location of a new gene, greA, on the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5256–5257. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5256-5257.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sukhodolets M V, Jin D J. RapA, a novel RNA polymerase-associated protein, is a bacterial homolog of SWI2/SNF2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7018–7023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sukhodolets M V, Jin D J. Interaction between RNA polymerase and RapA, a bacterial homolog of the SWI/SNF protein family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22090–22097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Travers A A. Promoter sequence for stringent control of bacterial ribonucleic acid synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:973–976. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.2.973-976.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Travers A A, Lamond A I, Weeks J R. Alteration of the growth-rate-dependent regulation of Escherichia coli tyrT expression by promoter mutations. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:251–255. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Chromatin remodeling and transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:182–191. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wackwitz B, Bongaerts J, Goodman S D, Unden G. Growth phase-dependent regulation of nuoA-N expression in Escherichia coli K-12 by the Fis protein: upstream binding sites and bioenergetic significance. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:876–883. doi: 10.1007/s004380051153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker K A, Atkins C L, Osuna R. Functional determinants of the Escherichia coli fis promoter: roles of −35, −10, and transcription initiation regions in the response to stringent control and growth phase-dependent regulation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1269–1280. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1269-1280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zacharias M, Goringer H U, Wagner R. Influence of the GCGC discriminator motif introduced into the ribosomal RNA P2- and tac promoter on growth-rate control and stringent sensitivity. EMBO J. 1989;8:3357–3363. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y N, Jin D J. The rpoB mutants destabilizing initiation complexes at stringently controlled promoters behave like “stringent” RNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2908–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Y N, Gottesman S. Regulation of proteolysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1154–1158. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1154-1158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]