Abstract

Using a large-scale corpus of 706 coronavirus cartoons by male and female Arab artists, this study takes a fresh and more cognitive look at sexism in multimodal discourse. Specifically, it examines the role of salience and grammar (and hence of metaphor and metonymy) in gender bias and/or in discrimination against women. It argues that both men and women are vulnerable to the influence of stereotypical and outdated beliefs that create unconscious bias. But this raises the crucial issue of whether we can speak of ‘overt’ sexism in images. Issues around terminology and conceptualization are thus also investigated. Importantly, this paper makes the following contributions to feminist and cross-cultural pragmatics: (i) it brings a distinctly Arabic perspective to gender and language; (ii) it expands socio-cognitive pragmatics beyond spoken and written communication; (iii) it shows a close coupling between an Arabic grammar and other aspects of culture; and (iv) it has the potential for impact beyond academia, specifically in the sphere of coronavirus care or of health communication.

Keywords: Arab minds, cartooning, gendered metaphors, gendered metonymies, sexism

Introduction

Metaphor is a cross-frame mapping (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). A source frame such as JOURNEY may be used to conceptualize a target frame such as LOVE. As a cognitive phenomenon, metaphor occurs not only in language, but also in other modalities, including gesture (e.g. Cienki and Müller, 2008). Metaphors are hardly gender-neutral. They can be feminized or masculinized (Abdel-Raheem, 2022a; Koller, 2004; Lazar, 2009; Velasco-Sacristán and Fuertes-Olivera, 2006). As an example of the former, consider the MATING metaphor in mergers and acquisitions discourse (Koller, 2004) or metaphors drawn from a swath of traditionally feminine activities, as in the following Naji Benaji cartoon depicting the globe as a well-manicured woman with fingernails painted and decorated with the flags of the world and having a large, coronavirus-shaped ring of gold on the Chinese ring finger of her left hand (Figure 1). As an instance of the latter, think of the BUSINESS IS WAR/FIGHTING metaphor. Importantly, women are excluded by reifying business as a male arena. In fact, a male-defined social sphere disadvantages men and women alike, as also noted by Koller. Yet, gendered metaphors can be investigated along two other main dimensions: the use of metaphors to describe different people of different sexes (Anderson and Sheeler, 2005; Edwards and Chen, 2000; Edwards and McDonald, 2010; Luchjenbroers, 1998, 2002; Pastor and Verge, 2021) and gender differences in metaphor use (Charteris-Black, 2012; Koller and Semino, 2009; see also the papers in Ahrens, 2009). Although the area of multimodality is gaining in importance, the third dimension is rarely addressed (cf. Gilmartin, 2001; Gilmartin and Brunn, 1998; Templin, 1999; Tipler and Ruscher, 2019; Zurbriggen and Sherman, 2010). This is probably due to the male domination of the film and television industries or of fine and illustrative arts (Abdel-Raheem, 2022b; Streeten, 2020; Swords, 1992). In any case, the idea of innate gender difference is, in fact, rejected by most contemporary scholars of gender and language. I, too, follow this social constructivist view on gender and language. In other words, the differences and similarities in the metaphoric choices made by men and women can be explained in terms of a range of sources of variation, such as age, class, race, political orientation, economic situation, goals, and audiences (Semino and Koller, 2009). Finally, metaphor often works in combination with other tropes, including metonymy, irony, and hyperbole. Despite the clear role that metonymy plays in expressing stereotypical gender identities, there has been very little acknowledgment of this in the literature.

Figure 1.

THE CORONAVIRUS AS A GOLDEN RING, Naji Benaji, 28 March 2020.

This paper examines instances of ‘creative’ forms of sexism in visuals. In particular, working from 706 Arab cartoons on the coronavirus pandemic, it investigates gendered metaphor and metonymy. The aim of the research can be summarized as follows:

To identify whether the coronavirus is feminized or masculinized. Or, to put the question differently, does salience (Giora, 2003) or the grammatical gender of such nouns as ‘corona’, ‘virus’, ‘covid’, ‘face mask’, and ‘hand sanitizer’ in Arabic predict the gender of personifications in cartoons?

To identify whether the CORONAVIRUS source domain is used to represent men and women. The frequencies of the metaphors MEN ARE THE CORONAVIRUS and WOMEN ARE THE CORONAVIRUS are thus examined.

To identify whether there are gender differences in the types of metaphors or in how metaphors are employed to depict the coronavirus pandemic. As shall be seen, there are variations on the same source domain. For instance, male Libyan artist Alajili Elabidi cartoons a house as a mousetrap catching Covid-19, while female Egyptian cartoonist Samah Farouq caricatures a male physician setting a mousetrap to catch the virus.

To identify whether doctors, patients, and medical scientists (all elements of the PANDEMIC frame) are represented as men and nurses as women (in roles subordinate to male figures). This involves a MEMBER FOR CATEGORY metonymy in which male doctors/male patients or female nurses stand for both men and women. Previous research points to the unequal representation of women physicians and scientists in media (e.g. González et al., 2017; Wood, 2011). For Domínguez and Sapiña (2022), the lack of significant gender differences may be due to the underrepresentation of women cartoonists in their data (with nine cartoons, representing 2.2% of the entire sample). This has a clear echo in Anna van Heeswijk’s ‘With newspapers so male-dominated, is it any surprise that women are portrayed the way they are? Changing the number of female writers and the ways in which women are portrayed in the media is crucial if we are serious about wanting a socially responsible press’ (Hill, 2012, para. 4). I, however, assume that women cartoonists also have implicit bias against their own gender (see also Warrell, 2016).

And to consider the implications of how metaphors and metonymies are used for healthcare professionals.

Initially, this study will consider some previous research on the types of sexism and offer a brief review of such approaches as feminist sociolinguistics, feminist discourse analysis, and feminist pragmatics. Specifically, it will address the question of whether such forms as overt or direct sexism and covert or indirect sexism (Mills, 2008) can be usefully extended to political cartoons and discuss sexism as a concept that partially overlaps with the term ‘impoliteness’ (Culpeper, 2011; Kaul de Marlangeon, 2020). Details of the methodology are then given, followed by an analysis of the cartoons. The article concludes with suggestions for future research.

Overt versus covert sexism

In contemporary research, the notion of what constitutes sexism is a difficult one (Mills and Mullany, 2011). Some consider it as the categorization of someone as belonging to a group that they do not associate themselves with or is about a text that may be judged as sexist, such as ‘Look at you crying over this film – women are so emotional’ (a description that relies on stereotypical and outdated beliefs (Mills, 2008)). Some argue that sexism influences men’s and women’s lives. Apparently, there are other forms of discriminatory language. Mills (2008) separates sexism and hate speech from one another (see also Richardson-Self, 2018). Indeed, whether the use of lyrics such as ‘smack my bitch up’ in some gangsta rap is intended to incite violence is hard to prove. There is also some overlap between sexism and impoliteness, as shall be seen. Mills contends that sexism takes two major forms: direct and indirect. The former, now declining, is overtly stated, while the latter, extremely common, takes place at the level of metaphors, presuppositions or inference, conflicting messages, humor, or irony. Indirect sexism is therefore extremely difficult to challenge.

In her discussion of overt sexism, Mills (2008) focuses on a wide range of elements: words and meaning (including naming, dictionaries, generic pronouns and nouns, insult terms for women, the semantic derogation of women, and the use of first names, surnames and titles for women) and processes (including an examination of transitivity, reported speech, and jokes). Examples of overt sexism include the use of generic ‘he’ and ‘man’ and the traditional loss of name on marriage in English-speaking countries. In Arabic-speaking cultures, women (except first ladies such as Suzan Mubarak and Jehan Sadat) retain their own surname but often change their name to ʔumm ‘mother’+ their eldest (male) child’s name on giving birth. Men often also take their eldest son’s name (or, if they have only daughters, their eldest daughter’s name) preceded by the noun ʔabu ‘father of’. After all, the micro-level of individual experiences and interpretations cannot be overlooked (van Dijk, 2014). In other words, the assumption that a text will be read as unequivocally sexist by all readers is highly problematic (Mills and Mullany, 2011). Indeed, some young women choose to stay at home, putting their children ahead of their own career needs.

But a great deal of sexism is simply inferred rather than intended (Mills and Mullany, 2011). Specifically, sexism in visual genres such as cartooning and advertising is often masked by humor and irony, hence the difficulty in classifying it as sexism. In other words, it is ‘a form of sexism which has been modified because of feminist pressure and because of male responses to feminism’ (Mills, 2008: 133), hence the term ‘indirect sexism’. For Velasco Sacristán (2009), advertising gender metaphors may give rise to sexist readings that are ‘often covertly or weakly overt communicated’ (p. 119). Or, to put it another way, some may question the notion of overt sexism in pictures, but for different reasons: ostensive pictures cannot communicate coded, explicit information (given that this is what explicatures convey) ‘or, to reformulate, there would then be no visuals that on their own, unaccompanied by language, transmit explicit assumptions’ (Forceville, 2020: 76; cf. Abdel-Raheem, 2020; Forceville and Clark, 2014). In her analysis of complaints to the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), Cameron (2006) also reported that the majority of the complaints about sexism in advertisements were regarded to be ‘reflecting the special sensitivities of a politicized minority’ rather than reflecting the views of a large majority of readers and viewers (p. 41). I return to the problem of working out intentionality and that of political correctness in more detail later. For now, one can note that overtness admits degrees: Some female cartoonists may avoid visual clichés in male cartoons, such as the depiction of the globe as a man or the characterization of a nation as a woman; they may explicitly resist metaphors they have produced, those imposed upon them by men, or metaphors that they find to be disadvantageous to women; they may be radical feminists, discriminating against men on the grounds of their sex alone. And in spite of that these same women cartoonists may have implicit bias against their own gender. I follow this up in more detail in the analysis of a range of examples from my corpus.

Earlier, Swim and Cohen (1997) also suggested that there are three forms of sexism: overt sexism, where there is direct discrimination, treating women less favorably based on gender; covert sexism, including less direct and less revealed discrimination; and subtle sexism, involving ‘unequal and unfair treatment of women that is not recognized by many people because it is perceived to be normative, and therefore does not appear unusual’ (p. 117). Only subtle sexism has therefore been claimed to be probably unconscious and/or not maliciously intended (Sue and Capodilupo, 2008). No doubt these categories are used somewhat differently from Mills’ usage above. An example of overt sexism is telling a woman she would not be hired because of her gender. Covert sexism can be exemplified by not voting for a female president (asking oneself if the country is really ready for a woman president, or failing to grasp that the next commander-in-chief may wear a pantsuit) despite claiming to be ‘liberal’ or ‘gender-neutral’ (Nadal, 2010). Finally, an example of subtle sexism is representing an authority figure or professional (e.g. boss, comedian, professor, or doctor) as a ‘he’ or verifying that a stereotypical member (e.g. secretary or nurse) is a woman without knowing the gender of the said person. This latter example may in fact fit into Mills’ category of overt sexism. It is discussed under the heading of salience in Giora (2003). According to Giora’s graded salience hypothesis, a response (e.g. a meaning) is salient (i.e. foremost on one’s mind) if it is stored or coded in the mental lexicon (e.g. the ‘male’ and ‘female’ characteristic of doctor) and if it ranks high on prominence due to cognitive and usage-based dimensions, including individual experiential familiarity. Particularly interesting then is to examine whether there is a clear correspondence between the degree of salience of meanings and personified gender in art (see also Abdel-Raheem and Goubaa, 2021). The role of cognitive and cultural salience in the creation of conceptual metonymies (e.g. MEMBER FOR CATEGORY) is also rarely discussed. Exploring salience-frame relationships in detail can also be seen as offering a particularly rich area for further theory building. More of this will be heard below.

Sexism and impoliteness: A partial overlap

Research on gender stereotypes points to sexism in the media. Consider the highly sexualized images of women in cartooning, advertising, and films. The overt ways in which women such as Hillary Clinton, Sarah Palin, or Angela Merkel are represented in the media are in fact potentially offensive. Pinar-Sanz (2018) analyzes a Guardian cartoon in which then-German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, is depicted as a sadistic dominatrix along with three little blue creatures, Smurfs, who obey and follow her: Christine Lagarde (then-Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund), Herman van Rompuy (then-President of the European Council), and Mario Draghi (then-President of the European Central Bank). The 15 May 2012 cartoon, by Steve Bell, is entitled ‘Austerity electing a new Greek people’ and inspired by Delacroix’ painting ‘Liberty leading the people’, as facilitated by the textual signal ‘after Delacroix’ in the top right-hand corner. Pinar-Sanz claims that the purpose of the implied reference to the world of sadomasochism is to reinforce the offense intended against Merkel: Germany’s chancellor (as often with Bell) is a dominating woman (especially one who inflicts pain for pleasure, thinks she is invincible, and/or who is in close connection with abuse, violent pornography, or perversion). By this she apparently means that the cartoon is an instance where an impolite stance or attitude seems to be indicated through implying something (for pictorial implicature, see Abell, 2005; Forceville, 2020). Both particularized and generalized implicatures of (im)politeness are acknowledged by Terkourafi’s (2001, 2005, 2009) frame-based account (see also Leech, 2014: 71–74), although she ‘reserves the lion’s share for the latter and none of them amount to politeness (or impoliteness) by themselves’ (Culpeper and Terkourafi, 2017: 27).

Compare this with a Guardian cartoon blending Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and the murder of the dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, for which the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, is ‘liable’. The cartoon is captioned ‘Steve Bell on Donald Trump’s defence of the Saudi regime’. In the cartoon, bin Salman (=‘Venus’) stands nude in the giant scallop shell washing himself in blood, while the Trump administration somehow attends to the bloodshed he is responsible for (the brutal assassination of Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul). In particular, on the right-hand side of the cartoon then-US President Donald Trump, nude and toilet-headed, holds out the American flag, ready to place it round the shoulders of the crown prince. The nymph extending a purple cloak is thus mapped onto Trump. The toilet implies excretion via a CONTAINER (TOILET) FOR CONTENT (URINE/SOLID WASTE) or DEVICE (TOILET) FOR PURPOSE (EMPTYING THE BODY OF URINE AND SOLID WASTE) metonymy. There is also a HEAD FOR BRAIN FOR MIND FOR INTELLIGENCE FOR THINKING PERSON metonymy (see Kraska-Szlenk, 2019). Of particular interest is also the metaphorical use of nakedness as a source of shame. On the left-hand side of the picture, Donald Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner (=‘the wind god Zephyr’), carries his wife, Trump’s eldest daughter Ivanka (=‘Aura’). Both look on admiringly at bin Salman bathing in the blood of Khashoggi (instead of intervening or condemning him). The cartoon is transparently contingent on numerous circumscribed themes (murder, nudity, or excretion). It is pragmatically an accusation of the Saudi regime and the Trump administration. The conceptualization of bin Salman and Trump in terms of women (BIN SALMAN AS VENUS and TRUMP AS A NYMPH) is potentially derogatory and sexist, given (i) the direction of conceptualization, from a lower source to a higher target in patriarchal societies in which men are generally considered to be above women (Lakoff, 1996) and (ii) the negative cultural associations with women (emotional, in need of protection, etc.). If seen as a metaphor (a feature of cartoons) or irony, the reference, under the guise of satire, may be deemed ‘permissible’ (Edwards, 1997: 26). In other words, ‘[h]umor aids in the task of ridicule, but it also “neutralizes” hostility’ (Edwards, 2014: 113; scare quotes added). This also fits with Mills’ suggestion that impoliteness has to be considered as part of a Community of Practice (CofP) (Wenger, 1998), ‘a loosely defined group of people who are mutually engaged on a particular task’ (Mills, 2003: 30). In this respect, folklinguistic/first-order (im)politeness/(im)politeness1 must be distinguished from theoretical linguistic definitions of (im)politeness/second-order (im)politeness/politeness2 (Mills, 2003). This understanding of impoliteness, however, conflates the concepts ‘sanctioning’ (or ‘legitimating’) and ‘neutralizing’ (Culpeper, 2011). That is, there can be situations where the employment of impoliteness is sanctioned but participants may still feel bad or take offense – the contexts are not necessarily neutralized. Thus, the subjects depicted in cartoons may be offended by the type of depiction, even though they know that it is all a cartoon. As with ritualized banter, the neutralization of impoliteness, then, requires that the situation competes with the salience of the impoliteness signal – but despite such signals as smiles and laughter, people may still feel offended (Culpeper, 2011).

Of course, humor’s ambiguity can facilitate negative behaviors and resistance, enabling humorists to go ahead with the utterance of something potentially offensive or sexist without fear of recrimination (Grugulis, 2002; Haugh, 2016; Kahn, 1989). Mills (1998) analyzes a number of advertisements where conflicting messages are given about gender and feminism. For Mills (2008), these conflicting messages are a type of indirect sexism. But then a query arises as to whether political cartoons also constitute cases where there is a complex interplay of non-sexist/gender-neutral and sexist attitudes, or what is termed mixed messages, which ‘are very often designed to be ambivalent as to the producer’s “genuine” intentions, [and hence] often give rise to a range of different evaluations on the part of participants’ (Culpeper et al., 2017a: 349; single quotes in the original; see also Haugh and Chang, 2015 for Chinese; Furman, 2013 for Russian; Maíz-Arévalo, 2015 for Spanish). Investigating the metapragmatics of mixed messages– be it sarcasm, jocular mockery, ritual insults, mock impoliteness, mock politeness, insincere or manipulative politeness, or some other form– in different languages, cultures, and modalities, the nature of their ‘mix’, their functions (affective, instrumental, and interpersonal, and, like all pragmatic phenomena, invariably fitted to the specifics of the context in which the mixed message actually occurs) and their relationship to evaluations of (im)politeness, sexism and offense (or the perception of mixed messages) can move sexism and impoliteness scholarship forward ‘from the analysis of what is commonly known to an exploration of not simply what we do not know but what we are not yet aware we do not know’ (Culpeper et al., 2017a: 350).

After all, the ‘same’ cartoon may be acceptable in one period or culture, libelous, abusive, or sexist in another (see Abdel-Raheem, 2021). For instance, Jordanian cartoonist Emad Hajjaj was arrested in Jordan Wednesday 28 August 2020 for criticizing the agreement between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to normalize relations and after publishing a drawing depicting the UAE leader, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al-Nahyan, holding a dove with an Israeli flag on it spitting in his face, the spit taking the form of an F-35. The picture has a caption in Arabic, which translates as follows: ‘Israel asks America not to sell F-35 aircrafts to the Emirates’. The cartoon was deemed ‘offensive for the United Arab Emirates’, and the cartoonist was charged with seeking to undermine Jordan’s relations with a ‘friendly country’. Similarly, many US cartoonists have got death threats because of cartoons that seem to have angered government authorities or challenged persons’ deeply felt identities (Edwards, 2014). It appears useful, however, to distinguish between appropriate face-attack (reasonable hostility) and unreasonable face-attack (Tracy, 2008), and suggest why the former is essential in political cartooning. Tracy’s concept of reasonable hostility, involving ‘emotionally marked criticism of the past or future actions of public persons’ (p. 170), permits face threatening acts (FTAs) within legal contexts (including police interviewing and courtroom examination) both to be anticipated and to serve a positive and necessary function subject to certain conventions (Harris, 2001, 2011). A similar case can be made for political cartoons. Indeed, ‘[i]f ordinary democracy is to flourish, not only must hostile expression be permitted, but the positive function it serves must be recognized’ (Tracy, 2008: 188). That being said, ‘anger, frustration, humor will and should enter political argument’ (Stokes, 1998: 166). It can be argued, however, that the notion of reasonable hostility, following Tracy, is problematic, in that it can be perceived in different ways by different participants: the targets of the face-attacks (e.g. politicians), or those whose interests align with them, will judge cartoonists making such visual or multimodal comments to be rude, offensive, unfair, etc. despite recognizing that the comments were not (fully) intended to be so (see also Culpeper et al., 2017a; Stollznow, 2020, whereas cartoonists and others in the public situation are likely to regard such contested actions or criticisms as reasonable hostility (i.e. aiming to express righteous indignation). As such, this position aligns with Haugh’s (2007) ‘how an implicature is understood by hearers is just as important as what the speaker might have “intended” in terms of what implicature arises in an interaction’ (p. 93; scare quotes added). The judgment that a disparaging comment is an example of reasonable hostility, however, depends ‘not only on what was said and how, but by whom and to whom’ (Tracy, 2008: 186). In other words, whether a face-attack a cartoonist initiates is reasonable hostility can be decided neither by the cartoonist nor by the target but by ‘a subset of people in a community, or a particular category of others (people of a certain race, ethnicity, religion)’ (p. 186). That is, reasonable hostility represents ‘a group-level judgment’ (p. 186). But, practically, how can the analyst arrive at a decision that the cartoon s/he is analyzing is sexist or impolite in the first place? Moreover, notions like ‘aggravated’ and ‘hostility’ are frequently employed in the provisions of current law in England and Wales on hate crime and indeed the Law Commission Report (Culpeper et al., 2017b). This all leads to the more interesting research questions such as: Can sexism and impoliteness research be usefully extended to the analysis of the language and cartoons manifested as racially or religiously aggravated hate crime (i.e. not only to socially proscribed actions but also to ones that incur legal sanctions)? What are the linguistic and non-linguistic characteristics of cartoons deemed by feminists or legal authorities as having the potential to be an indicator of sexism or racially or religiously aggravated offenses?

As noted by Richardson-Self (2018), detailed analyses of hate speech targeting women are rare. To begin to answer the first question posed above, there is then a need to consider linguistic sexism or impoliteness and to take into account that each mode, medium, or genre has its own technical, institutional, financial, and ideological affordances and constraints (e.g. cartoons are mass-communicative pictures and are read from paper or from a screen [in this latter case, the removal of supposedly offensive or otherwise inappropriate comments on sites by webmasters is another form of censorship]) (see Forceville, 2020). Using naturally occurring language data (particularly records of conversations that make one ‘feel bad’ (e.g. hurt, offended, embarrassed, humiliated, etc.)) and drawing on findings from linguistic pragmatics and social psychology, Culpeper (2011) identifies the following four evidence sources, ordered in terms of their weight in guiding his understanding of impoliteness: (i) co-text (e.g. ‘rude’, ‘abusive’, ‘insulting’, and/or any other explicit impoliteness metalanguage); (ii) retrospective comments (those made after the event in question and often taking the shape of long discussions by participants and/or observers about whether X is rude or impolite); (iii) certain non-verbal (or emotional) reactions (though bear in mind that participants can strategically control emotion displays to some extent); and (iv) the employment of conventionalized impoliteness formulas, such as insults (including personalized negative vocatives, assertions, references, etc.), incitement, and taboo words (of course, in the given context, since an insult can be used in a context where it is interpreted as banter). These Culpeperian sources of evidence are strikingly similar to Thomas’ (see Thomas, 1995: 204–207). Obviously, (ii) and (iii) constitute subcategories of (i) in some ways, and all three capture the notion that impoliteness is reacted to in certain ways, not least of all via the display of emotions (Culpeper, 2011). All these four evidence sources can be usefully extended to sexism research (see Abdel-Raheem, 2022a).

Tendentious versus non-tendentious humor

Tendentious, but not non-tendentious (or non-aggressive), humor (Freud, 1960 [1905]) typically involves a butt or target (the person or human-related activity that is taken as the object of the hostile, sexual, or racist aggressiveness), besides the person making the joke (the humorist) and the one in whom the joke’s goal of producing pleasure is achieved (the recipient). But, of course, the target and the recipient can be one and the same person. So can the target and the humorist, as in ‘gallows humor’ (Freud, 1905). In addition to traditional authority figures (e.g. elected or appointed officials), the targets of political cartoons may include (i) advocates for a specific issue or ideology (such as televangelists and feminists) and (ii) ‘John and Jane Q. Public who are often cast as implied or actual victims of officialdom and its transgressions [e.g. apathetic voters]’ (Edwards, 1997: 25). For this author, even where humor is not targeting a specific person in authority, there is a superiority element at play when one recipient is being amused at the expense of a naïve fool (the cartoon’s victim or the disparaged other(s)) (p. 26).

Relevant for our discussion then is Dynel’s (2013) so-called ‘disaffiliative humor’, involving ingroup-outgroup polarization and jointly explained by superiority and incongruity theories (see also Zillmann and Cantor, 1976). However, this Dynel notion is hardly plausible, for several reasons. First, ideological discourses, whether humorous or non-humorous, are typically polarized (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). Though crucial for the social definition of group polarization, fundamental categories such as identities, actions, intentions and goals, norms and values, reference groups (allies/enemies), resources or interests, and the knowledge of the participants are in any case marginalized or ignored by Dynel and many others (van Dijk, 2008). These contextual categories also imply a theory of relevance (cf. Forceville, 2020; Yus, 2016), a notion that is to a greater or lesser extent implicit in Dynel’s (2011) ‘the speaker means to be truly [?] abusive and demeaning to one hearer but humorous to another’ (p. 112) as well as in her ‘the butt of disaffiliative humour will not find it amusing [?], even if he/should [sic] recognise that fact that an utterance may be potentially humorous to someone else’ (Dynel, 2013: 134; for responses to mockery or teasing and self-denigrating humor, cf. Glenn, 2003; Pawluk, 1989; Schnurr and Chan, 2011). Given the importance of feeling or emotion here, little has been done (Culpeper and Hardaker, 2017). Indeed, many of the most popular studies on (im)politeness pay lip service to emotions and feelings without seriously discussing their effect or role within interpersonal pragmatics and in cognitive processes of sense-making (Langlotz and Locher, 2017). Importantly, emotions are connected to (cultural) contexts via cognition (see also Kádár, 2013; Langlotz and Locher, 2017), and intentionality should not be assumed to be free from cultural conditioning (Culpeper and Hardaker, 2017).

As pointed out by Culpeper (2011), emotions, in particular moral emotions (Haidt, 2003; Rozin et al., 1999), are activated for both the producer and target of impoliteness (be they individuals, groups, or institutions), can be positively or negatively valenced (a possible example of the former is gratitude), and involve cognitive appraisal rather than being simply biological reflexes (see also Kaul de Marlangeon, 2017; Wilutzky, 2015). But what kind (or kinds) of emotion is sexism or impoliteness associated with? Are different kinds of sexism/impoliteness associated with different kinds of emotion? Culpeper distinguishes between impoliteness resulting from violations of sociality rights and that caused by violations of face (for the emotional consequences of face loss, see Goffman, 1967), on the grounds that the former is more likely to be accompanied by other-condemning emotions (such as anger, disgust, and contempt) and the latter by self-conscious emotions (such as embarrassment and shame) (though it ‘could additionally involve other-condemning emotions if the face-attack [or face-aggravation] is considered unfair’ (Culpeper, 2011: 62). As noticed by this pragmatician, this in fact is in line with Spencer-Oatey’s (2002) claim that sociality rights are not regarded as face issues, ‘in that an infringement of sociality rights may simply lead to annoyance or irritation, rather than to a sense of face threat or loss (although it is possible, of course, that both will occur)’ (p. 541). Related to these rights then is morality – an important theme in the literature on metalanguage (Cameron, 2004). But we should not think that morality has nothing to do with face (for reciprocity as a key principle in the contextual dynamics of (im)politeness, see Culpeper, 2011).

For Culpeper (2011), impoliteness or, I would say, sexism has an intimate connection with moral order, that is, ‘beliefs about how things ought to be’ (p. 74). In their analysis of offensive comments posted under an inappropriate Facebook photograph of Iranian actress Golshifteh Farahani, Parvaresh and Tayebi (2018) show how impoliteness activates, and is activated by, moral order expectancies (such as prudency, decency, etc.), and reveal that its considerations depend heavily upon the development of communities whose members seem both to share and to demand common beliefs and similar social norms (i.e. the moral order). Similarly, Parvaresh (2019), in his study of aggressive language on Instagram, discusses how people employ a number of seemingly socially-shared assumptions and expectations (having their roots in moral values) to justify their assignment of blame, in general, and their employment of impolite language, in particular. Of course, an enormous quantity of data would be required to determine whether this phenomenon can go further than that (Parvaresh and Tayebi, 2018). Such a discussion, however, raises two further questions: Can impoliteness be designed as much for the over-hearing audience as for the target addressee? Can that audience be entertained? The answer to both is yes (Culpeper, 2011). The same can said of sexism. This only goes to show that researchers in (im)politeness or sexism phenomena in different sociocultural contexts need to expand their discussions beyond the very narrowly defined interactive frame, the dyad comprised of speaker/producer and hearer/target (Culpeper, 2011). The same is likely to apply to the interpretation of cartoons as sexist, impolite, aggressive, or offensive.

Turning back to intentionality, when proposing features of (im)politeness or sexism, the attention should then be shifted away from ‘speaker only’ bias to accommodate awareness (or perception) (Bousfield, 2010; Culpeper and Hardaker, 2017; Pavesi and Formentelli, 2019). When El Refaie (2011) discussed a Daily Mail cartoon on the subject of ‘gay marriage’ with the artist, he was at pains to emphasize that he was not ‘having a go at gay people’, that he was ‘really just having a laugh’, that the original ‘was given to or sold to somebody who was a homosexual and who appreciated the humor in it’, and that it would be hateful for him to think of having hurt or offended anyone, ‘unless a politician has done something terribly wrong’ (p. 97). Of course, sometimes an act is construed as both unintentional and offensive, and also described as rude or impolite (Culpeper and Hardaker, 2017)– a finding that Culpeper (2011) explains by arguing that not all impoliteness or, I would say, sexism is deliberate, since (ii) sometimes the producer of something sexist, taboo, or impolite is not aware of the sexism or impoliteness effects s/he is causing (cf. Malle and Knobe, 1997) and (ii) failing to avoid doing unintended but foreseen harm often leads to judgments of moral culpability (see Ferguson and Rule, 1983). Importantly, ‘the claim that something is just intended as a joke is often used as a defensive strategy and does not necessarily tell us anything about where a humorist’s real sympathies lie’ (El Refaie, 2011: 97). This is consistent with the idea that ‘in a world of multiple realities and constructed meanings the speaker of a comic utterance does not “own” the meaning and cannot control hearer meaning’ (Willis, 2005: 135). One way of accommodating all this is to regard intentionality, following Culpeper (2011), as a scalar term. Under the influence of cultural background and religious beliefs and regardless of what the (political) humorist’s attitudes are perceived to be, the hearer or reader-viewer may also refuse to be entertained by the stimulus (El Refaie, 2011: 99; see also Haugh, 2014), a fact that goes against Dynel’s (2013) ‘[t]he hearer who is meant to be amused cannot [. . .] sympathise with the butt to an extent that the commiseration will eclipse humour’ (p. 134). This is in tune with Bergson’s (1911: 5) argument that laughter ‘demands something like a momentary anaesthesia of the heart’ (for experimental support, see also El Refaie, 2011). Some people may then reject humor because they feel sympathy for the ‘butt’, or because they do not want to be identified with attitudes they perceive to be prevalent among reader-viewers and which some of them can also attribute to the text. This only goes to show that humor allows people to ‘display, read, and negotiate identity’ (Glenn, 2003: 2). In short, determining whether or not the potentially ‘tendentious’ nature of a humorous stimulus contributes to its enjoyment by some of the reader-viewers requires a detailed psychological assessment of them (El Refaie, 2011).

Finally, there is empirical evidence that people, though clearly recognizing fictional characters of the political cartoon genre, tend to treat depicted scenarios as ‘real-like’ (El Refaie, 2011). One consequence of this finding, according to this cognitivist, is that analysts must reject the common argument that people can draw a line between the ‘real thing’ and ‘make-believe’ and that humor should be allowed without restriction.

Sample and methods

My analysis of sexism in Covid-19 art is based on a corpus of 706 cartoons created by male and female Arab professional cartoonists (12 male and 15 female; aged 31–54) and published between 1 March 2020 and 8 February 2022, corresponding to the first weeks of the coronavirus outbreak in the Chinese city of Wuhan in early 2020 or the pre-vaccine phase of the pandemic. The cartoons were collected via Cartoon Movement’s online image database (https://cartoonmovement.com/, last accessed 8 March 2022) and taken from Tomato Cartoon’s Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/tomatocartoon/, last accessed 10 February 2022), using the same keywords (e.g. ‘coronavirus’ and ‘COVID-19’) and criteria (focusing on Arabic as a non-European language with a complex two-gender system (Abdel-Raheem and Goubaa, 2021)). The male subcorpus contains 363 cartoons, compared to 343 cartoons in the female subcorpus. Table 1 summarizes the annotated datasets.

Table 1.

Annotated data.

| Cartoonist | Age | Gender | Nationality | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omayya Joha | 44 | Female | Palestinian | 11 |

| Safaa Odah | 41 | Female | Palestinian | 5 |

| Muhammad Sabaaneh | 43 | Male | Palestinian | 79 |

| Alaa Allagta | 49 | Male | Palestinian | 42 |

| Amr Fahmy | 53 | Male | Egyptian | 55 |

| Hany Tolba | – | Male | Egyptian | 15 |

| Doaa Eladl | 42 | Female | Egyptian | 140 |

| Sahar Essa | – | Female | Egyptian | 9 |

| Naglaa Fawzi | 43 | Female | Egyptian | 15 |

| Marwa Elgallad | 30 | Female | Egyptian | 10 |

| Amany Hashem | 42 | Female | Egyptian | 11 |

| Houida Ibrahim | 42 | Female | Egyptian | 11 |

| Samah Farouq | 35 | Female | Egyptian | 47 |

| Naji Ben Naji | 42 | Male | Moroccan | 11 |

| Riham El Hour | 44 | Female | Moroccan | 29 |

| Alajili Alabidi | 51 | Male | Libyan | 70 |

| Amna Al Hammadi | 43 | Female | Emirati | 21 |

| Emad Hajjaj | 54 | Male | Jordanian | 28 |

| Osama Hajaaj | 50 | Male | Jordanian | 10 |

| Nasser Ibrahem | 44 | Male | Iraqi | 22 |

| Amine Labter | 39 | Male | Algerian | 6 |

| Siham Zebiri | 38 | Female | Algerian | 18 |

| Amin Al-Habarah | 41 | Male | Saudi | 15 |

| Hana Hajjar | – | Female | Saudi | 3 |

| Rashad Alsamei | 40 | Male | Yemen | 10 |

| Dalal El-ezzi Kaissi | 40 | Female | Lebanese | 5 |

| Amany Alali | 38 | Female | Syrian | 8 |

| Total = 706 | ||||

The analysis had two phases: a quantitative stage to identify metaphor types and a qualitative stage to identify metaphor use – both supported by computer software. To examine the influence of salience and the grammatical gender of Arabic nouns on the gender of personifications in my corpus, I excluded the following categories of cartoons: in 135 the personified gender was unclear (e.g. there were only non-gender-specific hands) and in 288 the portrayal was non-human (e.g. animal, inanimate object, etc.). The duplicates (40) were also removed. And 171 contained no visual representation of the virus. A naïve coder (not familiar with the grammatical genders of nouns in Arabic) carried out all of these judgments. The sample I analyzed included 32 distinct entities, including ‘corona’, ‘coronavirus’, ‘covid’, sulaal-ah or mutaHawir ‘variant’, ‘covid-ah’, kimaam-ah ‘face masks’, and muʕqim ‘hand sanitizer’. Initially, I classified metaphors according to their source domains: for example THE CORONAVIRUS AS A PERSON (a MAN or a WOMAN) and the reversed mapping A PERSON (e.g. TRUMP, or an ISRAELI SOLDIER, or a WOMAN/WIFE) AS THE VIRUS. These account for 72 and 49 occurrences respectively. Non-sexist images (those that do not refer to men or women) were removed. The characterizations of women as the CORONAVIRUS occur only in the Alajili Alabidi sample. In any case, the number of occurrences (two across the overall corpus) is too small to be indicative of any sociocultural trend, as shall be seen. Core elements of the PANDEMIC or MEDICAL INTERACTION frame (including doctors, nurses, patients, medical researchers, vaccine manufacturers, and people profiteering from the pandemic crisis) were then also classified into (i) men, (ii) women, (iii) both sexes, (iv) non-gender-specific (e.g. due to protective medical clothing), and (v) non-human (e.g. when money is substituted for a patient) (see also Domínguez and Sapiña, 2022). The variables were tested with independent intercoder reliability tests. Ten percent of the sample (52 cartoons) was coded by two independent researchers. Results showed substantial agreement according to Cohen’s kappa coefficient (Landis and Koch, 1977). Patients appeared in 220 cartoons, and healthcare workers in 301 cartoons. The characters were interpreted as doctors, nurses, patients, or medical researchers by means of metonymy type CLOTHING/INSTRUMENT/ACTION FOR AGENT. For example, a white coat is worn over everyday clothes by a doctor in a hospital or a scientist; a stethoscope is an instrument that a doctor uses to listen to a patient’s heart and breathing; etc. Sometimes patients have also been represented by cultural icons (e.g. a male snake charmer or a woman with a bindi is a metonym for India). Specifically, things such as ‘shifting perspective’, ‘zooming in on’, and ‘focusing on’ seem to be appropriate descriptions of what takes place in metonymy, whereas ‘mapping features’ is what occurs in metaphor (Forceville, 2009; Littlemore, 2015). I also distinguished between metaphorical and non-metaphorical representation: For example, a doctor is often depicted as a soldier, a superhero, a football player, St. George, or Atlas. The characterizations of a politician as a DOCTOR or a NURSE are notably absent from my data. Finally, some Gestalt principles of foreground-background and center-margin were applied to the cartoons in order to examine whether the role of women was more active or passive than that of men (Kress and van Leeuween, 2006). There was moderate agreement among coders.

The identification of visual metaphor also had two phases: a phase to determine who cartoons what to whom under what conditions, why and in what way or whether it is to be taken literally (relevance assessment) and another to cluster the elements or characters that belong together and to pick out those that do not belong (fine-tuning the analysis) (for details, see Abdel-Raheem, 2021).

Finally, this study adopted a metalanguage to describe the linguistic/multimodal phenomena that relate to sexism or impoliteness. Specifically, it examined emotional reactions for Facebook users, such as Love, Haha, Wow and Angry. Explicit impoliteness metapragmatic comments and/or metalanguage (e.g. ‘sexist’ and ‘insulting’) might give us good evidence that sexism or impoliteness was perceived (Figure 2).

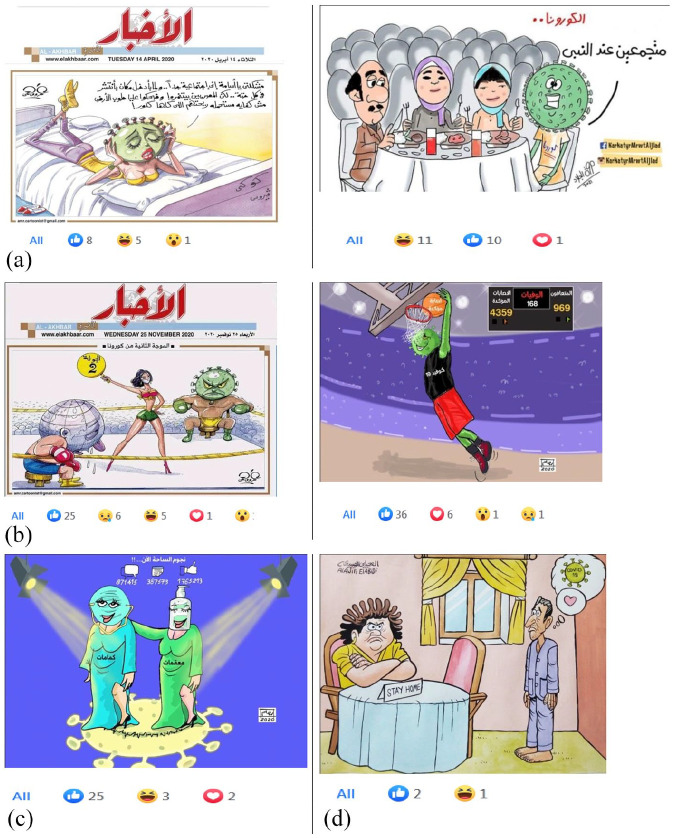

Figure 2.

Grammar and salience in coronavirus cartoons. (a) THE CORONAVIRUS AS A WOMAN. 1. Amr Fahmy, 13 April 2020. 2. Marwa Elgallad, 25 November 2021. (b) THE CORONAVIRUS AS A MAN. 1. Amr Fahmy, 25 November 2020. 2. Riham El Hour, 30 April 2020. (c) MASKS AND SANITIZERS AS WOMEN; Riham El Hour, 12 March 2020. (d) WOMEN/WIFE AS THE VIRUS; Alajili Alabidi, 27 March 2020.

Results: Salience and grammatical gender in Covid-19 cartoons

The gender of the virus

Nouns in Arabic are either of masculine or feminine gender. The feminine gender is usually the marked form, and the masculine gender the default marked one. The most common feminine marker is the taa’ marbuuTah–ah/-at. This suffix is replaced by -aat in the case of the sound feminine plural. Less often the suffix ʾalif mamduudah -aaʾ or ʾalif maqSuurah -aa is attached to a feminine noun. As a rule of thumb, a word without a feminine suffix is masculine. For example, ‘Covid’ or ‘virus’ is masculine, whereas ‘corona’ or kimaam-ah ‘face mask’ is a noun of feminine gender. ‘Covid’ is feminized by adding the suffix ‘ah’. The relative frequency of the feminine noun ‘Covid-ah’ in the cartoons of Doaa Eladl and Naglaa Fawzi is interesting because this feminine word is notably absent from the male subcorpus.

The results showed that grammatically feminine entities were more likely to be personified as male (35% female, 65% male), and that grammatically masculine entities were more likely to be personified as male (0% female, 100% male) (Table 2). Cell B = 0, and hence it may be that cell B represents an event so rare that only a truly huge sample (or even the entire population of all images) might reveal a count. The 2 × 2 (crosstabulation table) analysis results report the items highlighted in the yellow boxes for the chi-square and phi correlation coefficient. The statistical significance could be reported as p < 0.00001. The Cohen d effect size is moderate (with reference to the Cohen d interpretation guidelines from table 1 in Ferguson, 2009) – likewise the phi coefficient (Table 3). The results were thus statistically significant – but I needed to add 1 to every cell (what is referred to as ‘additive smoothing’ in order to avoid the ‘invalid’ results (because of a division by zero when using cell B). It is an unusual or rare but known issue when a single cell in a 2 × 2 table occurs. After all, sensitivity was very low: This is the probability that an actual (outcome) observed event is predicted correctly, that is Cell A/(Cell A + Cell C).

Table 2.

Number of female and male personifications shown by grammatical gender.

| Grammatical gender | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feminine | Masculine | |

| Personified as female | 13 (A) | 0 (B) |

| Personified as male | 24 (C) | 35 (D) |

Table 3.

Dichotomous relationships and decision table statistics.

| Observed frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes/Agree/Success | No/Disagree/Fail | Totals | |

| Yes/Agree/Success | 14 | 1 | 15 |

| No/Disagree/Fail | 25 | 36 | 61 |

| Totals | 39 | 37 | 76 |

| Expected Frequencies | |||

| Yes/Agree/Success | No/Disagree/Fail | Totals | |

| Yes/Agree/Success | 7.6974 | 7.3026 | 15 |

| No/Disagree/Fail | 31.3026 | 29.6974 | 61 |

| Totals | 39 | 37 | 76 |

For example, the feminine noun ‘corona’ is frequently portrayed as a woman. In a cartoon by female Moroccan cartoonist Riham El Hour, grammatically feminine entities such as kimaam-aat ‘face masks’ and muʕqim-aat ‘hand sanitizers’ are also personified as female. In contrast, the masculine word ‘Covid’ or ‘variant’ is usually personified as male. But grammar is only one of the forces that may affect the gender of personification in cartoons. Particularly interesting then is the role of salience in a cartoonist’s decisions in personification. For example, ‘male’ is the more frequent/stereotypical/salient feature of pilots, boxers, soldiers, presidents, arm-wrestlers, police officers, letter carriers, customers sitting in a coffee shop, and footballers or athletes, hence the high frequency of male personifications (i.e. of the characterizations of the coronavirus as a SPORTSMAN, a POLICEMAN, a PRESIDENT, a MALE SOLDIER, a MAILMAN, a WAITER, a MALE BOXER, or an ARM-WRESTLER) in my data (e.g. Figure 2b). In contrast, ‘female’ is the more frequent feature of, say, belly-dancers. That is, the use of metaphors such as WAR, SPORTS, and DANCING also plays a role in widening the gender gap.

It is important, however, to explore variation in metaphor use. For example, the woman coronavirus has been sexualized by Egyptian cartoonist Amr Fahmy. Consider Figure 2a1 above, where the virus is depicted as a slim young woman lying on her stomach, her breast supported by a pillow. The woman is named ‘Kuukii virus’ (a diminutive of coronavirus). A sexually explicit picture that objectifies and portrays women as sexual objects is potentially humorous, but also sexist. Another cartoon by Fahmy depicts the virus as an obese mother wearing a blue skin-tight dress. Compare this with the non-sexualized body of the woman virus in the Marwa Elgallad cartoon in Figure 2a2. Particularly of interest is the more frequent use by women cartoonists (Doaa Eladl, Marwa Elgallad, Amany Hashem, Naglaa Fawzi, and Samah Farouq) of the non-sexualized metaphor CORONAVIRUS AS A MOTHER, with Covid variants (including Delta and Omicron) as CHILDREN. A cartoon by female Moroccan artist Riham El Hour depicts face masks and hand sanitizers as sexualized belly-dancers, however (Figure 2c). Alaa Allagta further portrays the coronavirus as a fat bride. The virus and the bride are blended together in a form of superimposition or fusion.

Women are depicted as the virus in only two cartoons, by Alajili Alabidi. One of them features an angry housewife with hair that is made to look like the coronavirus spike protein (HOUSEWIFE AS CORONAVIRUS). The wife is sitting down to eat, hands crossed, while her sad husband is standing about a meter from her with thought bubbles above his head displaying the images of coronavirus and a red love heart (Figure 2d). The sign on the dinner table alerts the husband to stay home. In many societies, home is a place where women typically rule, that is, the kingdom of women or the society where a husband is rarely the boss. The reverse is the case outside the family unit (see Kyratzis and Guo, 1996). The cartoon implies that husbands must take some precautions against their ‘coronavirus wives’ to reduce exposure and transmission. The other cartoon shows a woman seeing herself in the mirror as a coronavirus (WOMAN AS CORONAVIRUS). Both cartoons/multimodal jokes are potentially sexist.

The characterizations of the virus as a SPORTSMAN occur in the cartoons by Riham El Hour (4) and Amr Fahmy (2). El Hour depicts the coronavirus as a MLAE GOALKEEPER, a MALE BASKETBALL PLAYER, a MALE LONG JUMPER, or a MARATHON RUNNER, whereas Fahmy portrays the virus as a MALE BOXER or a MALE OLYMPIC ATHLETE (Figure 2b). Alajili Alabidi further cartoons the virus as a MALE TANK COMMANDER, while El Hour caricatures Covid-19 as a MALE MUSICIAN or a MALE CLOWN. Alabidi also depicts the coronavirus as a TEENAGE BOY, a POLICEMAN, a NEWS PRESENTER, and a POSTMAN, among other male figures.

Especially prevalent in sexism and other forms of prejudice, then, are MEMBER OF A CATEGORY FOR THE CATEGORY metonymies, but also PART FOR WHOLE ones (see Littlemore, 2015). The representation of doctors as men or the underrepresentation of men nurses also illustrates this point, as we shall see. The influence of stereotypes on metonymy is well-documented (Radden and Kovecses, 1999). Crucially, stereotypical over non-stereotypical is one of the key principles that reflect cultural preferences, or that account for why certain kinds of expressions and images tend to be chosen as metonymic sources and others do not. The genre of political cartooning relies strongly on stereotypical ideas to portray categories of people (Bounegru and Forceville, 2011), simply because stereotypes seem to be more accessible or cognitively salient than less stereotypical concepts and therefore tend to get employed as a point of access to other notions (Littlemore, 2015). A case in point is the WOMEN’S UNDERWEAR FOR WOMEN metonymy. This also means that assuming that this type of text will be judged as unequivocally sexist by all recipients is problematic (Mills and Mullany, 2011). In other words, ‘whereas some individuals may be damaged by sexist discourse, others will recognize it for what it is, resist it, laugh at it and/or become empowered in the process’ (Sunderland, 2004: 194). But note that repetition makes sexist language and frames (including sexist metaphors and metonymies) normal, everyday language and everyday ways to think about men and women. That is, sexist prejudices or stereotypes are ‘presupposed and taken for granted as if it were socioculturally shared knowledge’ (van Dijk, 2014: 104). This may make sexism hard to detect. Indeed, a female cartoonist does not necessarily or always draw as a woman (see van Dijk, 2014). In contrast, taboo or impolite language, albeit probably part of people’s brains, does not come to be accepted as normal. Hence, people may resist a metaphor not because it is sexist, but because it is taboo or impolite. It thus makes sense to distinguish between first- and second-order sexism, just as is the case with impoliteness (Watts et al., 1992). The former refers to perceptions of what sexist behavior is, whereas the latter denotes scholarly conceptualizations of sexism with precise definitions formulated for research purposes. That being said, responses to sexist abuse – funny, ferocious, etc. – are context-dependent (Figure 2).

The ‘humorous’ cartoon in Figure 2d is based on the assumption that wives tend to dominate their husbands at home, an assertion that can be categorized as sexist for most analysts, since it seems to be asserting that gender and family happiness are linked. Because this is a stereotypical view of housewives, it is available for use by individual cartoonists. However, this stereotypical depiction may not go unchallenged. The dehumanizing metaphor is, of course, an aggravated insult. It is thus mediated by humor. This is an example of a cartoon that is classified as sexist based on the stereotypical knowledge. But there are cartoons that can be judged as linguistically sexist (as would be the case with the personified gender of abstract entities).

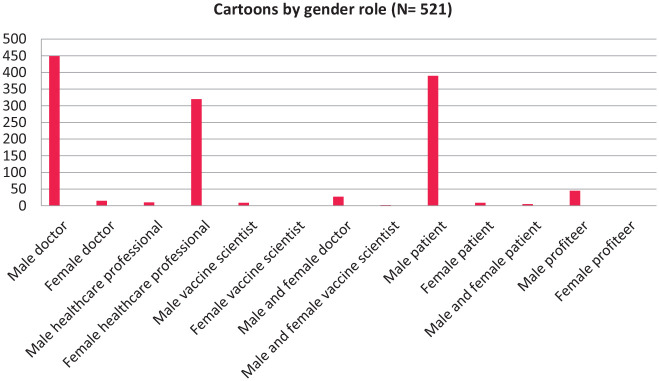

The gender of a patient or of a healthcare professional

Covid-19 patients, doctors, scientists, and those profiteering from the coronavirus crisis are predominantly represented as men in 97% of the cases (Figure 3). Most cartoons also represent nurses as women. For instance, female Egyptian cartoonist Doaa Eladl depicts a male doctor suffocating a male patient by choking up the throat (Figure 4a1). The doctor asks a female nurse whether the patient has footed the bill. ‘Let us check’, the female nurse replies. Eladl criticizes the private health system’s devotion to profits over patients. She thus also draws two male ambulance attendants putting money (a contextual metaphor for patients) on a stretcher. The irony is that Eladl screams out against some metaphors for women (including depictions of women as animals and objects) but applies the same metaphors to men, or that she is an ardent feminist but is influenced by gender stereotypes, overrepresenting men at the expense of women. Correspondingly, female Egyptian artist Houida Ibrahim cartoons the globe as a man who takes his hat off to a male physician. Male Jordanian cartoonist Emad Hajjaj further portrays a female nurse praying for a Covid-19 victim (Figure 4a2) – something that is traditionally attributed to women. He also cartoons male medical scientists looking through a microscope. A male patient, a male healthcare professional, or a female nurse is a MEMBER FOR CATEGORY metonymy, that is, a hidden shortcut in language, thought, and communication (see Littlemore, 2015). It is through the processes of conventionalization that such cognitive phenomena as metonymies and metaphors ‘become hidden and do not need to be accessed upon interpretation’ (p. 128). Unconscious sexism is so embedded in culture that men and women often fail to recognize when they are reinforcing it. In other words, it is not just male cartoonists who hold unconscious bias toward women; female cartoonists can also have implicit bias against their own gender. The role of cognitive and cultural salience in sexism cannot therefore be overstated.

Figure 3.

Cartoons by gender role.

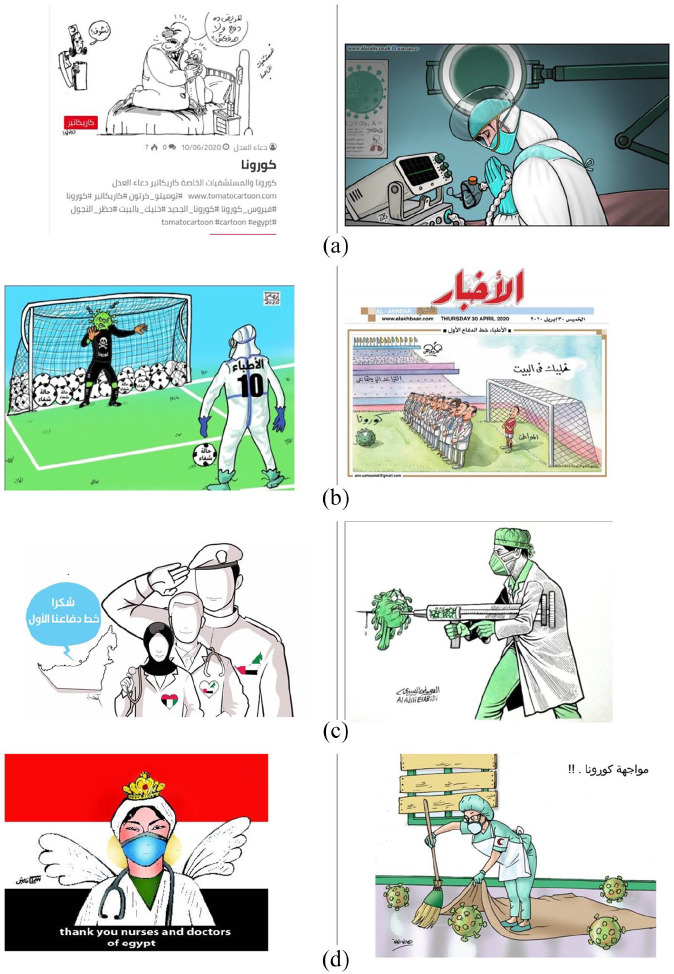

Figure 4.

Healthcare professionals in the time of pandemic. (a) Non-metaphor. 1. Doaa Eladl, 10 June 2020. 2. Emad Hajjaj, 31 March 2020. (b) SPORTS/FOOTBALL. 1. Riham El Hour, 3 April 2020. 2. Amr Fahmy, 30 April 2020. (c) WAR/FIGHTING. 1. Amna Al Hammadi, 2020. 2. Alajili Elabidi, 3 April 2020. (d) Feminized metaphors. 1. FEMALE DOCTOR AS QUEEN-ANGEL, Samah Farouq, 15 April 2020. 2. SWEEPING CORONAVIRUS UNDER THE CARPET, Hany Tolba, 28 November 2020.

Especially relevant for us, then, is the use of masculinized and feminized metaphors. The frequent use of war/fighting and sports metaphors is especially interesting. Both Doaa Eladl and Riham El Hour cartoon a doctor as a male footballer, while Amr Fahmy caricatures men and women healthcare workers as a wall of defenders (Figure 4b). But women doctors sometimes also appear in the foreground in front of male physicians or soldiers, as in the Amna Al Hammadi cartoon in Figure 4c1. Compare this with the Alajili Elabidi cartoon in Figure 4c2, where a male doctor is depicted wielding a syringe as a weapon. Doaa Eladl, albeit an ardent feminist, also cartoons a male doctor fighting a dragon-coronavirus, treading on coronavirus particles, or protecting a male patient from the virus. Interestingly, the representation of doctors as women is altogether absent from her sample. Some cartoonists, including Naglaa Fawzi, further caricature a male doctor as Superman. In addition, Samah Farouq cartoons a male physician bombing the virus. Moreover, Naji Ben Naji depicts a male healthcare professional as a bullfighter. The metaphoric view of the pandemic as war or sports is highly masculinized and therefore helps maintain medicine or science as a male-dominated domain. Still, the type of violent physical action is gendered. For instance, it is typical of Egyptian women to beat someone with a shoe or slipper. Hence, Houida Ibrahim caricatures an Egyptian housewife (a potential victim of Covid-19) beating the virus with a slipper. Similarly, the depiction of a female nurse (a metonym for the public health sector) sweeping the coronavirus crisis under the carpet is highly feminized – cleaning has traditionally been the domain of women (Figure 4d2). Likewise, Samah Farouq depicts a female doctor with angel’s wings (Figure 4d1). The metaphor can be verbalized as FEMALE DOCTOR AS ANGEL. To complicate matters, milking a cow by hand is predominantly considered a female activity (at least in Egypt), but business is a male-dominated area – hence the depiction of a vaccine manufacturer as a man milking a coronavirus cow. The COVID-19 VACCINES AS A COW MILKED BY PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES metaphor occurs more frequently in the Osama Hajaaj and Naji Ben Naji samples, but notably absent from the female cartoons.

Finally, male and female physicians are drawn together in only 5% of the sample. These appear in cartoons by Amr Fahmy (1), Emad Hajjaj (2), Naji Benaji (3), and Amna Al Hammadi (1), among others. In this category, women’s role is often more subordinate than active or equal.

Discussion and conclusion

In the studied cartoons, salience and grammar have influenced an artist’s decisions in personification, guiding his/her choice of metaphors and metonymies, and therefore also reinforced double standards. Not only do women cartoonists fail to recognize latent sexism in men cartoonists, they are often unaware of their own. The coronavirus discourse is dominated by male representations. The virus is often personified as male. It is portrayed as a soldier, a boxer, a president, or an athlete, whereas a woman coronavirus or face mask frequently appears sexualized (a belly-dancer, a young girl laying down on the bed, etc.). Male figures are repeatedly used to metonymically represent doctors and patients, whereas nurses are predominantly represented as women in most cartoons. The cartoons, including those made by female cartoonists, commonly show a man as a doctor with no female companion. Despite the impact of feminism and the changes that have come in the wake of women’s integration into the workforce, men and women cartoonists have not changed much. Women healthcare professionals are usually portrayed praying for victims of the virus, or sweeping the crisis under the carpet, or as angelic queens, while men healthcare workers are typically depicted as soldiers, footballers, or arm-wrestlers (that is, in more active, athletic or fighting poses).

Apart from being disadvantageous to women, the underrepresentation of women physicians and scientists in coronavirus cartoons is also far from being entirely beneficial for men either. This seems particularly true in the case of social spheres and practices characterized as sites of aggression (Koller, 2004). A case in point is also the representation of coronavirus profiteers as men. These biases – thought patterns, assumptions, or interpretations – hold men and women back from reaching their true potential. Of course, cartoonists (men or women) are sensitive to degrees of cultural and cognitive salience. Hence, sexism is again a graded, rather than either-or, notion. Sexist representations such as the portrayal of physicians, patients, and medical researchers as men do not seem to operate in the same way as sexism in examples such as the depiction of women/housewives as the coronavirus. The latter may still work through humor and playfulness and therefore can be seen as an example of covert or indirect sexism. However, a sexist cartoon (i.e. a cartoon that is too threatening to a man’s or woman’s core sense of identity) can create anger and social alienation, but not amusement (El Refaie, 2011). After all, different readers can perceive a cartoon in different ways and it can be described as sexist or offensive despite the butt recognizing that it has not been (fully) intended to be so (see Abdel-Raheem, 2022a; Culpeper, 2011). I have therefore considered the role of Facebook ‘reactions’ (Like, Love, Haha, Wow, Sad, or Angry) in guiding my interpretation. A distinction has also been made between first- and second-order sexism.

Repeating sexist metaphors and phrases parrot-fashion can, of course, be seen as playing a crucial role in maintaining the status quo. In other words, male and female cartoonists must unlearn current stereotypes and relearn new beliefs. They must resist gendered metaphors and metonymies that they have created, gendered metaphors and metonymies that are imposed upon them, or metaphors and metonymies that they perceive to be sexist/offensive or that negatively stigmatize others (for how metaphors are resisted, see Gibbs and Siman, 2021). Hence, this paper is considered of interest for feminist media studies, including feminist pragmatics, feminist critical discourse analysis, and feminist cognitive linguistics, but also for intra- and cross-cultural research. Second-wave feminist linguists have shown incredible strength in consciousness raising, compiling thesauruses of sexist language and advising on the avoidance of such words as ‘gossip’, which is frequently used to define and degrade women (Kramarae and Treichler, 1985; Miller and Swift, 1982; for the effect of gender-neutral language on evaluations and judgments, see Tavits and Pérez, 2019). Constructing dictionaries of sexist multimodal metaphors and metonymies and calling for artists and advertisers to avoid such depictions is no less important.

Author biography

Ahmed Abdel-Raheem is currently a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Bremen. His work appeared in more than 30 journal articles (e.g. in Social Semiotics, Intercultural Pragmatics, Journal of Pragmatics, Pragmatics and Cognition, Discourse and Society, and Review of Cognitive Linguistics) and one monograph (Pictorial Framing in Moral Politics: A Corpus-based Experimental Study, Routledge, 2019).

Footnotes

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work on this research was made possible by a grant to the author from the University of Bremen (CRDF-Positions No. 23 and 24).

References

- Abdel-Raheem A. (2020) Do political cartoons and illustrations have their own specialized forms for warnings, threats, and the like? Speech acts in the nonverbal mode. Social Semiotics. Epub ahead of print 10June2020. DOI: 10.1080/10350330.2020.1777641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Raheem A. (2021) Conceptual blending and (im)politeness in political cartooning. Multimodal Communication 10(3): 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Raheem A. (2022. a) The “menstruating” Muslim Brotherhood: Taboo metaphor, face attack, and gender in Egyptian culture. Social Semiotics. Epub ahead of print 22May2022. DOI: 10.1080/10350330.2022.2063714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Raheem A. (2022. b) Taboo metaphtonymy, gender, and impoliteness: How male and female Arab cartoonists think and draw. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Raheem A, Goubaa M. (2021) Language and cultural cognition: The case of grammatical gender in Arabic and personified gender in cartoons. Review of Cognitive Linguistics 19(1): 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Abell C. (2005) Pictorial implicature. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 63(1): 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens K. (2009) Politics, Gender, and Conceptual Metaphors. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KV, Sheeler KH. (2005) Governing Codes: Gender, Metaphor, and Political Identity. Oxford: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson H. (1911) Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic. London: Macmillan; (first published in French in 1900). [Google Scholar]

- Bounegru L, Forceville C. (2011) Metaphors in editorial cartoons representing the global financial crisis. Visual Communication 10(2): 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield D. (2010) Issues in impoliteness research. In:Locher M, Graham SL. (eds.) Interpersonal Pragmatics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp.101–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D. (2004) Out of the bottle: The social life of metalanguage. In: Jaworski A, Coupland N, Galasi’nski D. (eds.) Metalanguage: Social and Ideological Perspectives. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp.311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D. (2006) Language and Sexual Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris-Black J. (2012) Shattering the Bell Jar: Metaphor, gender, and depression. Metaphor and Symbol 27(3): 199–216. DOI: 10.1080/10926488.2012.665796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cienki A, Müller C. (eds) (2008) Metaphor and Gesture. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper J. (2011) Impoliteness: Using Language to Cause Offence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper J, Hardaker C. (2017) Impoliteness. In: Culpeper J, Haugh M, Kádár DZ. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Linguistic (Im)Politeness. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper J, Haugh M, Sinkeviciute V. (2017. a) (Im)politeness and mixed messages. In: Culpeper J, Haugh M, Kádár DZ. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Linguistic (Im)Politeness. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper J, Iganski P, Sweiry A. (2017. b) Linguistic impoliteness and religiously aggravated hate crime in England and Wales. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict 5(1): 1–29. doi 10.1075/jlac.5.1.01cul [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper J, Terkourafi M. (2017. a) Pragmatic approaches (im)politeness. In: Culpeper J, Haugh M, Kádár DZ. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Linguistic (Im)Politeness. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez M, Sapiña L. (2022) She-Coronavirus: How cartoonists reflected women health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Women s Studies 29: 282–297. [Google Scholar]

- Dynel M. (2011) Entertaining and enraging: The functions of verbal violence in broadcast political debates. In: Tsakona V, Popa D. (eds) Studies in Political Humor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp.109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dynel M. (2013) Impoliteness as disaffiliative humour in film talk. In: Dynel M. (ed.) Developments in Linguistics Humor Theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp.105–144. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Chaiken S. (1993) The Psychology of Attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JL. (1997) Political Cartoons in the 1988 Presidential Campaign: Image, Metaphor, and Narrative. New York & London: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JL. (2014) Cartoons. In: Attardo S. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Humor Studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp.112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JL, Chen HR. (2000) The first lady/first wife in editorial cartoons: Rhetorical visions through gendered lenses. Women’s Studies in Communication 23(3): 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JL, McDonald CA. (2010) Reading Hillary and Sarah: Contradictions of feminism and representation in 2008 campaign political cartoons. American Behavioral Scientist 54(3): 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- El Refaie E. (2011) The pragmatics of humor reception: Young people’s responses to a newspaper cartoon. Humor - International Journal of Humor Research 24(1): 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ. (2009) An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 40(5): 532–538. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TJ, Rule BG. (1983) An attributional perspective on anger and aggression. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein EI. (eds) Aggression: Theoretical and Empirical Reviews, vol. I.London and New York: Academic Press, pp.41–74. [Google Scholar]

- Forceville C. (2009) Metonymy in visual and audiovisual discourse. In Moya J, Ventola E. (eds.) The World Told and the World Shown: Issues in Multisemiotics. Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave MacMillan, pp.56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Forceville C. (2020) Visual and Multimodal Communication. Applying the Relevance Principle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forceville C, Clark B. (2014) Can pictures have explicatures? Linguagem em (Dis)Curso 14(3): 451–472. DOI: 10.1590/1982-4017-140301-0114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1905) Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewussten (Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious). Leipzig: Deuticke. [Translation by Brill AA, London:Kegan Paul]. [Google Scholar]

- Furman M. (2013) Impoliteness and mock-impoliteness. A descriptive analysis. In: Thielemann N, Kosta P. (eds) Approaches to Slavic Interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp.237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RW, Siman J. (2021) How we resist metaphors. Language and Cognition 13(4): 670–692. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin P. (2001) Still the angel in the household. Women & Politics 22(4): 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin P, Brunn S. (1998) The representation of women in political cartoons of the 1995 World Conference on Women. Women’s Studies International Forum 21: 535–549. [Google Scholar]

- Giora R. (2003) On Our Mind: Salience, Context, and Figurative Language. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn P. (2003) Laughter in Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. (1967) Interactional Ritual: Essays on Face-to-face Behavior. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- González D, Mateu A, Pons E, et al. (2017) Women scientists as decor: The image of scientists in Spanish Press Pictures. Science Communication 39(4): 535–547. [Google Scholar]

- Grugulis I. (2002) Nothing serious? Candidates’ use of humor in management training. Human Relations 55(4): 387–40. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. (2003) The moral emotion. In: Davidson RJ, Sherer KR, Goldsmith HH. (eds) Handbook of Affective Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.852–870. [Google Scholar]

- Harris S. (2001) Being politically impolite: Extending politeness theory to adversarial political discourse. Discourse & Society 12(4): 451–472. [Google Scholar]

- Harris S. (2011) The Limits of Politeness Revisited: Courtroom discourse as a case in Point. In: Linguistic Politeness Research Group (ed.) Discursive Approaches to Politeness. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp.167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh M. (2007) The discursive challenge to politeness research: An interactional alternative. Journal of Politeness Research 3(7): 295–317. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh M. (2014) Im/Politeness Implicatures. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh M. (2016) ‘Just kidding’: Teasing and claims to non-serious intent. Journal of Pragmatics 95: 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh M, Chang WLM. (2015) Understanding im/politeness across cultures: An interactional approach to raising sociopragmatic awareness. IRAL: International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 53(4): 389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. (2012) Sexist stereotypes dominate front pages of British newspapers, research finds. The Guardian, 14October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2012/oct/14/sexist-stereotypes-front-pages-newspapers (Accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Kádár DZ. (2013) Relational Rituals and Communication: Ritual Interaction in Groups. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn WA. (1989) Toward a sense of organizational humor: Implications for organizational diagnosis and change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 25(1): 45–63. DOI: 10.1177/0021886389251004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul de, Marlangeon S. (2017) Tipos de descortesía verbal y emociones en contextos de cultura hispanohablante. Pragmática Sociocultural/Sociocultural Pragmatics 5(1): 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul de, Marlangeon S. (2020) Impoliteness and sexist behaviours reproduced by women in the River Plate culture. Texts in Process 5(2): 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Koller V, Semino E. (2009) Metaphor, politics, and gender: A case study from Germany. In: Ahrens K. (ed.) Politics, Gender, and Conceptual Metaphors. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Koller V. (2004) Metaphor and Gender in Business Media Discourse: A Critical Cognitive Study. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kraska-Szlenk I. (2019) Metonymic extensions of the body part ‘head’ in mental and social domains. In: Kraska-Szlenk I. (ed.) Embodiment in Cross-Linguistic Studies: The ‘Head’. Leiden/Boston: Brill, pp.136–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kramarae C, Treichler P. (1985) A Feminist Dictionary. London: Pandora. [Google Scholar]

- Kress G, Van Leeuwen T. (2006) Reading Images (2nd edition). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kyratzis A, Guo J. (1996) ‘separate worlds for girls and boys?’ views from U.S. And Chinese mixed-sex friendship groups. In: Slobin DI, Gerhardt J, Kyratzisand A, et al. (eds) Social Interaction, Social Context and Language: Essays in Honor of Susan Ervin-Tripp. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp.555–577. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G. (1996) Moral Politics: How Conservatives and Liberals Think. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G, Johnson M. (1980) Metaphors We Live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33: 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlotz A, Locher MA. (2017) (Im)politeness and emotion. In: Culpeper J, Haugh M, Kádár DZ. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Linguistic (Im)Politeness. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.287–322. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar M. (2009) Gender, war and body politics: A critical multimodal analysis of metaphor in advertising. In: Ahrens K. (ed.) Politics, Gender, and Conceptual Metaphors. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Leech GN. (2014) The Pragmatics of Politeness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Littlemore J. (2015) Metonymy: Hidden Shortcuts in Language, Though, and Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luchjenbroers J. (1998) ‘Animals, embryos, thinkers and doers: Metaphor and gender representation in Hong Kong English’. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 21(2): 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Luchjenbroers J. (2002) Gendered features of Australian English discourse: Discourse strategies in negotiated talk. Journal of English Linguistics 30(2): 200–216. [Google Scholar]

- Maíz-Arévalo C. (2015) Jocular mockery in computer-Mediated Communication: A Contrastive Study of a Spanish and English Facebook community. Journal of Politeness Research 11(2): 289–327. [Google Scholar]

- Malle BF, Knobe J. (1997) The folk concept of intentionality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 33(2): 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, Swift K. (1982/1989) The Handbook of Non-sexist Writing. London: Women’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills S. (1998) Post-feminist text analysis. Language and Literature 7(3): 234–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mills S. (2003) Gender and Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills S. (2008) Language and Sexism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills S, Mullany L. (2011) Language, Gender and Feminism: Theory, Methodology and Practice. London and New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL. (2010) Gender microaggressions: Implications for mental health. In: Plaudi MA. (ed.) InFeminism and Women’s Rights Worldwide, vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, pp.155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Parvaresh V. (2019) Moral impoliteness. In: Kádár DZ, Parvaresh V. (eds) Morality and Language Aggression. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp.79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Parvaresh V, Tayebi T. (2018) Impoliteness, aggression and the moral order. Journal of Pragmatics 132: 91–107. [Google Scholar]