Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised air transport stakeholders' concerns about the state of the market, the potential timing of recovery, and recouping long-haul traffic. Passengers’ travel confidence must be restored, and air travel safety awareness raised. This paper estimates the immediate and long-term effects of COVID-19 on air transport markets and forecasts timescales for recovery of the markets for domestic and international flights in nine African countries. Intervention analysis and SARIMAX are employed for the analysis, using monthly time-series data from August 2003 to December 2021. The empirical results show that air transport is significantly elastic to the pandemic. It is forecast that air transport recovery may take around 28 months for domestic flights and 34 months for international flights, starting from 2020. The simulation analysis suggests that passenger flights may rebound to pre-crisis levels between 2022 and 2023. In general, the pandemic-induced fluctuations in the aviation market and the nature of the rebound may be considered to be part of a cyclical process rather than a structural change.

Keywords: Air transport, COVID-19, Africa, Aviation recovery

1. Introduction

In a tightly connected and integrated world, the impacts of COVID-19 beyond mortality and morbidity have become apparent. Economies have slowed down, with interruptions to production and disruptions to global supply chains (McKibbin and Fernando, 2021; Del Rio-Chanona et al., 2020). The aviation and hospitality industries have been hardest hit economically by the COVID-19 pandemic (Sun et al., 2020), which has caused a steep decline in air travel, leaving airlines uncertain about regaining passengers.

COVID-19 is having multilayered impacts on African economies and the aviation industry, with lost traffic and revenues, and uncertain prospects. African carriers' revenues fell by $8 billion in 2020 (Abouk and Heydari, 2021), and 70% of the seven million jobs in the continent's aviation and tourism industry sectors have been lost (African Development Bank, 2020). With air traffic falling by nearly 90% (IATA, 2020a), some airlines will inevitably succumb to the pressures. As various restrictions are imposed in international markets, airlines based in small domestic markets may face particular challenges during the recovery process (Czerny et al., 2021). Examining the immediate and long-term effects of the pandemic on domestic and international flights may inform the implementation of support schemes and recovery processes.

However, African aviation is returning to the skies (IATA, 2021). As countries continue to ease lockdown measures and lift restrictions on international travellers, passengers are regaining their confidence and the industry is recovering (Gudmundsson et al., 2021). Passengers must feel confident about aviation safety and be assured that the rules on access to other countries are clear and will not cause disruption. This will depend partly on pandemic trends and vaccination progress in each country (Chen et al., 2020). Moreover, airlines may be conservative in redeploying their networks, and may need encouragement to return to airports (Dube et al., 2021). Countries are implementing various measures to help the industry survive the pandemic and facilitate the resumption of air transport to pre-COVID-19 levels. However, industry stakeholders have concerns about the timescales for recovery and the restoration of long-haul traffic.

Each airline defines long-haul differently. A long-haul flight is generally defined as a direct or non-stop flight with a journey time between 6 and 12 h. This paper defines long-haul traffic as intercontinental flights. This contextual definition is provided for simplicity and it's important to note, however, that it might not hold in other cases. Intercontinental flights can be short, medium, long, or ultra-long hauls. Africa is such a huge continent that even some intra-African travel may qualify as ultra-long haul. As indicated above, however, this study considers only intercontinental flights as long-haul flights.

African states and the aviation market have reacted to the pandemic in various ways, including lockdowns, rescheduled capacity, and financial, operational and regulatory measures (IATA, 2020a). COVID-19 has had a significant effect on both domestic and international flights. Due to unevenness in states' actions and individual airlines' reactions, the aviation market's responsiveness may vary across countries. Hence, the air transport market's long- and short-term responses to COVID-19 in different African countries must be examined. This study seeks to quantify the elasticities of domestic and international flights to the COVID-19 outbreak in immediate and long-run scenarios. Its two main objectives are to estimate the immediate and long-term effects of COVID-19 on air transport markets in Africa, and to forecast timescales for recovery of domestic and international flights in nine African countries. Similar studies have been conducted in developed economies (Gudmundsson et al., 2021; Andreana et al., 2021) however it is rare to find a robust analysis in Africa and this paper fills the gap.

Performing the study in an immediate and long-term time frame is important. The immediate effects are a reflection of the early stage of the pandemic, and they lay the groundwork for long-term effects. Different immediate policy interventions were implemented to maintain infection levels below the capacity of health care systems. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, these policies restricted mobility, and during the late stages of the pandemic, they have severe effects on air travel and the entire economy. Therefore, understanding the immediate effects would lay a foundation for analyzing the long-run effects and projecting how long the industry would take to recover.

Besides analyzing the immediate and long-term impacts of the pandemic, it is also important to forecast when air transport will fully recover. The empirical results of the forecast would assist policymakers and planners in their decision-making processes. Practical policy measures have been observed for both short-term responses and long-term strategies. There were two objectives of these policies: preventing the spread of the pandemic on the one hand, and helping the air transportation sector recover from the shock on the other. To combat the pandemic, entry restrictions and quarantine requirements were imposed on countries at high risk. A long-term strategy would be to replace quarantine with testing and vaccination certificates. Government-backed loans and grants helped the industry during the first stages of the pandemic. Recapitalization and nationalization of airlines were among the long-term recovery strategies.

In the remainder of this paper, Section 2 summarises the responses of African states and the aviation market to the pandemic, Section 3 describes the data and elucidates the methodology framework used, Section 4 presents the study results and analysis, and Section 5 draws some conclusions.

2. Responses of African states and the aviation industry to COVID-19

Aviation has often been a target for policy interventions, and particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, most firm-specific measures have targeted air transport (OECD, 2020), and the aviation sector has responded to state actions amidst the pandemic. Countries' actions and aviation market responses can be considered from two perspectives, as countries have implemented restrictions and the air transport sector has adjusted its scheduled capacity, while countries have also designed support schemes for the sector's recovery.

2.1. State restrictions and reduced scheduled capacity

Around March 2020, some African countries implemented restrictions to entry and/or mandated quarantine of travellers from high-risk countries. The latter generally included countries with high numbers of COVID-19 cases in Asia and Europe, but later also included the US and the UK. Countries tightened screening measures either onboard aircraft or in airports, or both. By the end of March, this had swiftly progressed to closing international borders and restricting domestic travel. Around the end of April and beginning of May 2020, domestic travel restrictions were removed in Ghana, the Seychelles, Namibia and Tanzania (InterVISTAS, 2021). Fig. 1 summarises the broad responses of African states and airlines to the COVID-19 crisis.

Fig. 1.

Governments' and airlines' responses to COVID-19.

Source: InterVISTAS (2021); IATA (2021); press statements by African airlines

On a continent where most airlines are state-owned (CAPA, 2016), airlines’ reactions and responses have been mixed, with drop-offs in demand and consequent losses in revenues. COVID-19 has been episodic (Gössling et al., 2020), so airlines have had to make rolling changes in response to unpredictable state measures. Most airlines operating scheduled services to Asia, particularly Air Mauritius, RwandAir, Kenya Airways, Royal Air Maroc and South African Airways, temporarily suspended these routes towards the end of January/beginning of February 2020. Ethiopian Airlines suspended flights to 30 countries and 80 destinations on 20 March 2020 (IATA, 2020a). From mid-March to the beginning of April 2020, most African airlines progressively reduced their capacity and ceased services altogether, both internationally and domestically (African Development Bank, 2020). Managing constantly changing restrictions has been challenging for airlines and airports, in terms of the resources required to enforce restrictions and increasingly complex passenger itinerary tracking, particularly with code-sharing across airlines and network carriers (Dube et al., 2021). Accordingly, African airlines have struggled. Most notably, Air Mauritius went into voluntary administration, and Comair Limited filed for business rescue, using bankruptcy protection measures under their domestic legislation. However, South African Airways and South African Airways Express were in administration even prior to the onset of COVID-19. Distressed airlines and airports placed staff on unpaid leave or signalled their intention to cut jobs.

Analyses of the effects of lockdowns and airlines’ responses to COVID-19 reveal substantial implications in terms of lost revenues, jobs at risk and reduced contributions to national economies. Table 1 summarises the implications of lost airline traffic for several African countries.

Table 1.

Implications of lost airline traffic for African countries.

| Passengers reduced (million) | Revenues lost (billion $) | Jobs at risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | 14.5 | 3.02 | 252,100 |

| Nigeria | 4.7 | 0.99 | 125,400 |

| Ethiopia | 2.5 | 0.43 | 500,500 |

| Kenya | 3.5 | 0.73 | 193,300 |

| Tanzania | 1.5 | 0.31 | 336,200 |

| Mauritius | 2.1 | 0.54 | 73,700 |

| Mozambique | 0.7 | 0.13 | 126,400 |

| Ghana | 1.4 | 0.38 | 184,300 |

| Senegal | 1.3 | 0.33 | 156,200 |

| Cape Verde | 1.2 | 0.20 | 46,700 |

Source: IATA (2020a); CAPA (2016); InterVISTAS (2021).

2.2. Economic responses by African states

To combat the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, IATA engaged in a campaign lobbying for support for the global aviation industry (IATA, 2020b). Broadly, it called for direct financial support, loans, tax relief, loan guarantees and support for the corporate bond market. Fig. 2 provides an overview of the various types of support received by airlines around the globe. Measures involving financial injections usually aim to maintain an airline's cash flow (Abate et al., 2020). Many measures were implemented at the onset of the crisis owing to its urgency.

Fig. 2.

Most common types of support received by airlines.

Source: IATA (2020b); African Development Bank (2020); InterVISTAS (2021).

While developed economies have injected substantial cash into their aviation industries, little support has been mobilised for the sector in developing and emerging markets, especially in Africa. African states' economic responses have varied, and the tourism and aviation industry has been granted little emergency assistance (see Fig. 3 ). African states’ financial support for their flag carriers has been small compared with worldwide practice. Some state-owned carriers that were uncompetitive prior to the crisis have collapsed, including South African Airways and Air Namibia. From March 2020, South African Airways was grounded and its operations suspended until the government nationalised the airline and provided support. It was able to resume operations in mid-September 2021 when the government agreed to sell a 51% stake to a group of investors (IATA, 2021). On the other hand, Air Namibia has been unable to survive the COVID-19 crisis and resume business. After years of struggle and reliance on handouts from the Namibian government to keep flying, in February 2021 it announced that it had ceased operations and was entering voluntary liquidation (see Appendix A4).

Fig. 3.

African and worldwide examples of direct government support for airlines.

Source: IATA (2020b); Bloomberg; FlightGlobal; African Development Bank (2020).

However, some Africa countries have taken direct action to support aviation and minimise the impact of the outbreak on the broader economy. According to the African Development Bank (2020), Senegal announced $128 million in relief for its tourism and air transport sector, and Seychelles waived all landing and parking fees from April to December 2020. South Africa deferred payroll, income and carbon taxes across all industries, which will also have benefited airlines domiciled in that country. Similarly, Cote d’Ivoire waived its tourism tax for transit passengers, and Zimbabwe announced a $20 million stimulus package for the tourism sector. Egypt also decided to lend Egyptair $191 million, stating that it would support the airline until it returns to 80% of 2019 operations (IATA, 2020b). Rwanda allocated $152 million of its national budget to RwandAir for recovery from the pandemic (see Fig. 3). Furthermore, whereas the Moroccan government granted a budget to support Royal Air Maroc, Ethiopian Airlines managed to stay afloat without government help or involuntary furloughs (IATA, 2020b).

The measures implemented by African states focused on keeping the industry alive by ensuring that the sudden halt in passenger traffic and subsequent low levels of demand did not cause lack of liquidity that might lead to airlines’ bankruptcy. As mentioned above, financial and non-financial support for the aviation market was uneven across African countries. Consequently, the longer-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the aviation market in each country may differ, and industry recovery times may vary. This study estimates these effects and forecasts industry recovery paths for nine African countries. The estimation considers the immediate and long-term effects on domestic and international markets.

3. Data and methodology

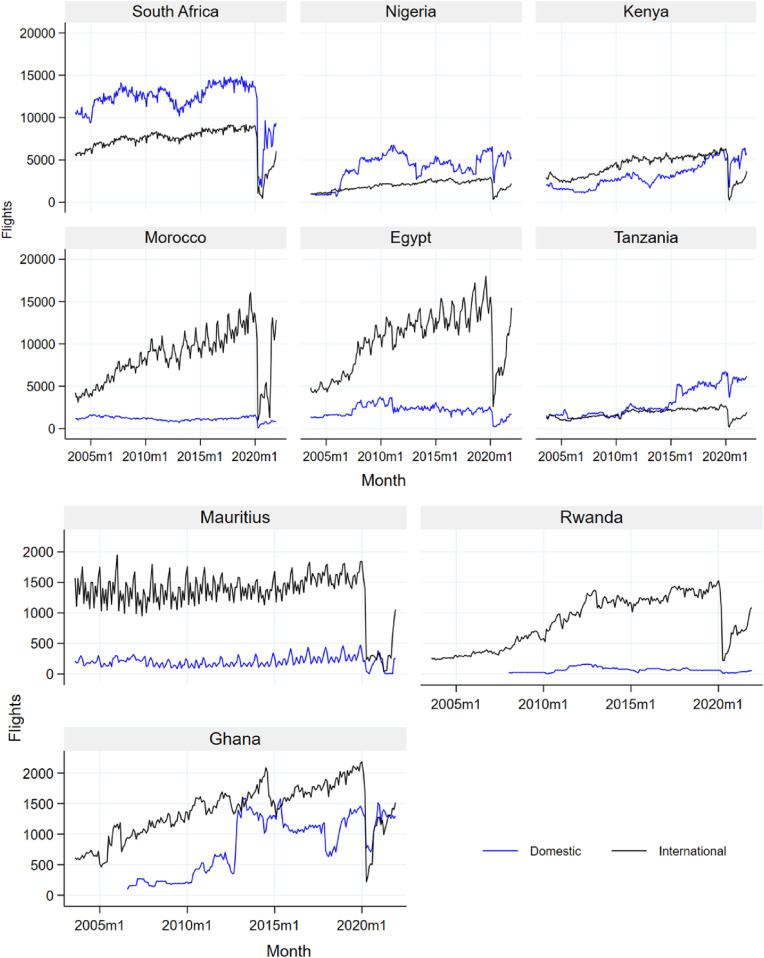

This paper assesses the air transport industry's responses to the COVID-19 crisis and estimates the timescale for its recovery. The air transport market is proxied by the number of domestic and international flights in each country. To closely observe the dynamics of the market, monthly time-series data from August 2003 to December 2021 are employed. Fig. 4 illustrates trends in domestic and international flights and COVID-19 interventions over this period. The sample countries were selected using a systematic sampling technique taking account of the growth of air transport services, availability of data and geographical locations. Considering the aforementioned factors, three countries from each geographical region were selected to represent the geographical regions of the continent. Morocco, Egypt, and Algeria from north Africa; Kenya, Tanzania, and Rwanda from east Africa; South Africa, Mozambique and Angola from Southern Africa; and Senegal, Ghana, and Nigeria from west Africa. Due to a lack of data, Algeria, Mozambique, Angola, and Senegal were excluded from the sample. Mauritius has instead been included in the sample to improve the sample size. As a result, nine countries were selected as samples for the study.

Fig. 4.

Trends in flight frequency and COVID-19 interventions.

Source: Authors' elaboration using SRS Analyzer

April 2020 was chosen as a point of intervention to assess the effects of COVID-19 and make forecasting specifications because restrictions were being strictly implemented, and the data series shows a significant change starting from this month. It is widely accepted that the effects of the pandemic occurring after April 2020 can be regarded as long-run effects (Himmels et al., 2021; Abouk and Heydari, 2021). This timeframe is used to define the immediate and long-term effects of the study. The delineation is also supported by the rising trends of the pandemic and the declining series of air travel. Air traffic in the sample countries was lowest in April 2020, as shown in Fig. 4. Furthermore, Andreana et al. (2021) showed that the fall in seats, frequencies, and ASKs was dramatic and had reached its bottom by the end of March/beginning of April 2020. This lowest point lasted for a variety of time periods. However, it was the threshold point for the countries involved in the study and therefore considered a delineation point between the immediate and long-term timeframes. Data on the number of domestic and international flights were obtained from SRS Analyzer.1

Air transport market operation depends on both supply capacity and demand generated within the existing economic and regulatory environment. Therefore, analyzing market dynamics using both sides of the data may yield more robust empirical evidence. As aviation regulation mainly determines the supply side, employing this data without demand side data could also result in robust analysis results. In spite of this, using only the supply side of the industry in the analysis is acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

The aims of this study are to estimate the immediate and long-term effects of COVID-19 on air transport markets in Africa, and to estimate the recovery period for both domestic and international flights. To accomplish these objectives, two related methods are employed: intervention analysis and seasonal auto-regressive integrated moving average with exogenous factors (SARIMAX).

COVID-19 has had significant effects on the air transport market. However, measuring these effects requires a feasible method. Critical responses by the air transport market to COVID-19 can be captured through intervention analysis, which forms part of autoregressive moving-average (ARMA) modelling. Box and Tiao (1975) pioneered this type of analysis to solve Los Angeles's pollution problem. Intervention analysis is the application of modelling procedures to incorporate the effects of exogenous forces or interventions into time-series analysis (Box-Steffensmeier et al., 2014). Unlike traditional dummy-variable analysis, it enables exploration of the timing of effects, and considers feedback from events through the dynamics of the series itself (Enders, 2008). In other words, intervention analysis allows formal testing of changes in the mean of a time series. For the first-order autoregressive process, the intervention analysis in this study can be modelled as:

| (1) |

where denotes flight frequency and . is an intervention variable that takes a value of zero before April 2020 and unity thereafter, and is a white-noise disturbance.

Prior to the intervention, the long-run mean of the series is ). Following the COVID-19 event, effects are labelled as immediate or long-run. The immediate effect of on is calculated as the magnitude of the coefficient , and the anticipated occurrence of the event is period t. For additional effects expected to occur beyond period t, describes the long-run effects of the intervention, expressed as follows:

| (2) |

The SARIMAX technique is also applied to determine the timescale for recovery of domestic and international flights. The SARIMAX model upgrades the ARIMA model with the Diebold-Mariano forecast comparison test inclusion of seasonality and exogenous variables (Chatfield, 2000). Seasonality captures variations in the air transport market that occur at regular intervals. COVID-19 has exogenous effects on the aviation market through market restrictions and drops in demand due to reduced travel confidence. Time-series techniques based on ARIMA models have been employed in forecasting to evaluate the presence of large shocks (Phillips,1996; Enders, 2008). The specified ARIMA model complemented with is defined as follows:

| (3) |

where denotes the non-seasonal autoregressive (AR) order, is the non-seasonal moving average (MA) order, is non-seasonal difference order, indicates the seasonal AR order, is the seasonal MA order, D is seasonal difference order, and is the length of the repeating seasonal pattern.

To estimate the intervention effects and forecast market recovery, the following procedures are applied. First, pre-intervention observations are used to find plausible ARIMA (SARIMAX) models. This step identifies the best-fitting ARIMA model over the period August 2003 to March 2020. Using the model selection criteria, the models indicated in Table 2 are selected for each country. No predictable seasonal variations are revealed in the aviation markets of Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda and South Africa. In the remaining countries, expected annual seasonal market variations are identified, although these may vary between countries.

Table 2.

The best-fitting ARIMA (SARIMAX) models.

| Model | |

|---|---|

| Egypt | ARIMA (1,1,1)a SARIMA (1,1,1,12)b |

| Ghana | ARIMA (1,1,0) |

| Kenya | ARIMA (1,1,1) SARIMA (1,1,0,12) |

| Mauritius | ARIMA (1,1,1) SARIMA (1,1,1,12) |

| Morocco | ARIMA (1,1,1) SARIMA (1,1,1,12) |

| Nigeria | ARIMA (1,1,1) |

| Rwanda | ARIMA (1,1,1) |

| Tanzania | ARIMA (1,1,1) SARIMA (1,1,0,12) |

| South Africa | ARIMA (1,1,1) |

ARIMA (1,1,1) indicates p(1), d (1) and q(1), respectively.

SARIMA (1,1,1,12) shows P(1), D(1), Q(1), m(12), respectively.

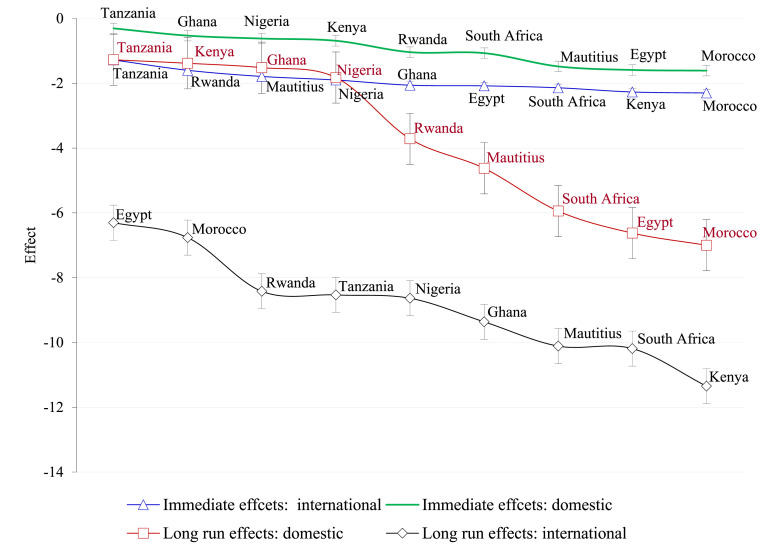

Second, the specified models are estimated over the entire sample period (pre- and post-intervention observations), including the effects of COVID-19. This step helps to identify the pandemic's immediate and long-term effects on the aviation market. The results of the estimation over the entire sample period are reported in Fig. 5 and Appendix A1.

Fig. 5.

Effects of COVID-19 on air transport markets.

Third, necessary and important diagnostic checks are performed for the estimated equations, including the Portmanteau test, ACFs and the distribution of residuals. This step is particularly important since pre- and post-intervention observations are merged. This step also indicates the strength of the model in forecasting the time taken for aviation markets to recover from the shock. The plots of autocorrelation, Appendix A8, showed that residuals are independent (white noise). The Q-Q plot, Appendix A5, also indicated that the residuals are normally distributed implying that the model inference is valid. The portmanteau test was used to examine whether the seasonal autocorrelations at multiple lags of time series are different from zero. The results fail to substantiate the lack of fit of SARIMAX models.

Finally, following analysis of the state of each country's aviation market, , recovery periods are forecast as the earliest month (year) in which the air transport market trend becomes higher than or equal to the pre-COVID-19 flight frequency level, . Finally, the Diebold-Mariano test is conducted to verify the accuracy of the forecast.

4. Results and discussion

This section presents the empirical results on how severely the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the air transport market and its estimated average recovery time. The immediate and long-term effects are evaluated to identify any consistent differences across countries for domestic and international flights. Estimates of recovery times for both domestic and international markets account for the shape of the likely rebound and the length of the recovery period.

4.1. Immediate and long-term effects on air transport services

Estimates of the immediate and long-term effects (see Fig. 5 and Appendix A1) indicate that air transport responded significantly to the outbreak. The analysis highlights that the market experienced sizable immediate effects, with few discrepancies between the sample countries. However, the long-term effects are considerably more severe than the immediate effects, with significant differences between countries. In both immediate and long-term effects, responses have been greater for international flights than domestic travel. Kim and Sohn (2022) highlight that international air transport demand has been affected more than domestic traffic and is also recovering more slowly.

Fig. 5 presents four scenarios for the effects of COVID-19 on African countries' aviation markets. Both immediate and long-term effects on domestic and international flights are assessed. More significant differences are observed across countries in the timing of effects (immediate versus long-run) than in types of market (domestic versus international). This may relate to changes in passengers’ behaviour, travel restrictions, the availability of alternative transport modes and the ensuing economic crisis resulting in reduced demand for air transport services (OECD, 2020).

The results show that the immediate effects were higher in Morocco, Egypt, Mauritius and South Africa than in the other countries in the sample. Morocco, Egypt and Mauritius are the top tourist destinations in the region, and South Africa is the economic and air-transport hub for southern Africa. This implies that air travel in these countries can be considered to be an essential mode of transport. The IEA (2020) suggests that in the immediate aftermath of crisis events, transport behaviour will change, as people reassess the costs and benefits of different transport modes. Transport patterns may also have changed significantly in response to both travel restrictions relating to the outbreak and the perceived risks of travelling (Shakibaei et al., 2021). Hence, the immediate effects of COVID-19 were a combination of government lockdowns and reductions in non-essential travel for fear of contracting or spreading the virus.

As indicated in Fig. 5, the pandemic's long-term effects on air transport markets are more severe than the immediate effects, for a broad range of reasons. The combination of reduced travel demand, supply shocks, and uncertainty about the long-run outlook have created considerable uncertainty for airline companies (Abate et al., 2020), affecting the whole aviation industry owing to inter-industry linkages. Moreover, the industry remains exposed to ongoing effects as authorities extend air travel restrictions to tackle infections. This may delay the industry's return to pre-crisis levels for some time (Gudmundsson et al., 2021).

In the long run, air transport services face uncertainties that may augment the pandemic's effects on the industry. International travel restrictions, the contraction of economic activity and changes in transport behaviour by cautious consumers may prevent a fast return to pre-crisis demand levels, even as lockdowns and domestic travel restrictions measures are loosened in many countries (OECD, 2020). Shamshiripour et al. (2020) claim that changes in consumer behaviour may result in structural changes to air transport demand, either through modal shifts, such as video-conferencing rather than travelling for business, or, to a lesser extent, through substitution with other modes of transport. Another uncertainty is that operating costs are likely to increase for both airlines and airports owing to additional health and safety requirements. According to Pearce (2020), the costs of air travel may continue to rise for a long period before reaching an equilibrium, as a result of increased turnaround times due to sanitisation, rises in infrastructure charges, and social distancing measures that may force reductions in the passenger load factor.

Furthermore, the long-run effects of the outbreak differ across countries. As shown in Fig. 5, international flights from Egypt and Morocco are likely to experience lower long-term effects than Kenya and South Africa. This deviation may depend on a range of factors, including perceptions of risk, cost and convenience, all of which affect people's travel decisions (Miao et al., 2021). Government policies may influence each of these factors differently, as governments may encourage and support their aviation industries, depending on their importance and contributions to the economy. The pandemic's effects may result in long-lasting reductions in air transport demand, especially where this sector is not considered essential to economic recovery (IEA, 2020).

4.2. Estimating the timescale for recovery of the air transport industry

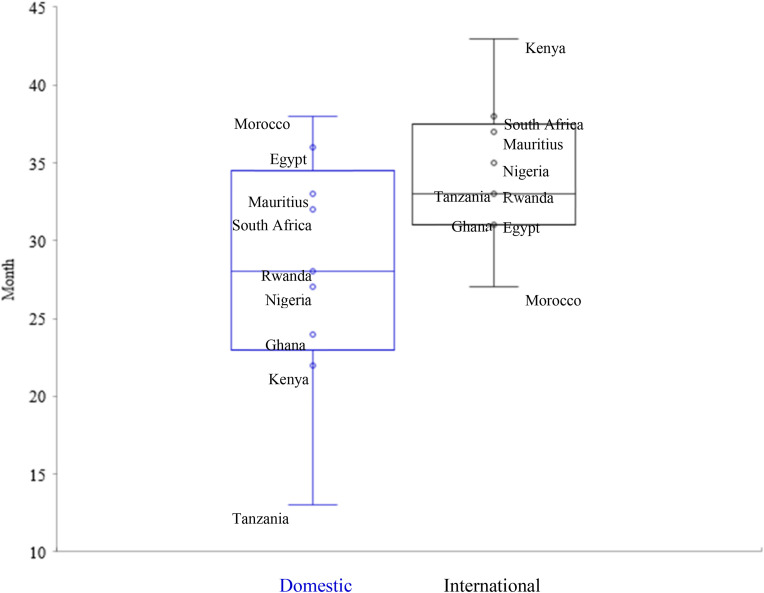

Estimates of recovery times reported in Fig. 6 show that air transport recovery will take on average 28 months ( 2.3 years) for domestic and 34 months ( 2.8 years) for international travel, starting from 2020. The simulation analysis indicates that 2019 passenger flight levels will be reached between 2022 and 2023. This is in line with Gudmundsson et al.’s (2021) empirical estimate that world recovery of passenger demand to pre-COVID-19 levels will take 2.4 years (recovery by late 2022). Similarly, Pearce (2012) found that international air travel rebounded within about 18 months after the low point of the 2008/2009 recession.

Fig. 6.

Estimated recovery times for domestic and international flights in Africa.

Analysis of recovery periods (see Fig. 6) shows uneven recovery paths across countries. Tanzania has the shortest estimated recovery time (13 months) for domestic flights, followed by Kenya (22 months) and Ghana (24 months). Tanzania announced the lifting of domestic travel restrictions in May 2020, earlier than other countries in the sample. The simulation indicates that Morocco's domestic flights will take longest to recover (38 months), and Egypt may take 36 months.

The analysis also shows that recovery patterns for international flights will differ across countries. On average, Morocco is likely to have the shortest recovery period ( 2.3 years), followed by Egypt ( 2.6 years) and Ghana ( 2.6 years). Recovery patterns will depend on specific aviation market characteristics and economic recovery trajectories. McKibbin and Fernando's (2021) empirical study indicates that these differences may rest on countries' specific institutional settings and economic structures, which determine their readiness for action and resilience during crisis periods. Gudmundsson et al. (2021) suggest that different recovery patterns may be ascribed to when the first outbreaks of COVID-19 were experienced and when lockdowns were relaxed in each country. In this study, specific supply-based characteristics of different countries are accounted for in the SARIMAX model, by estimating the model parameters based on past shock recoveries and the size of the shock in 2020 aviation output due to restrictive measures.

Fig. 6, Fig. 7 show that domestic flights will recover more quickly than international flights. This can be anticipated, given that lockdowns tend to be eased on domestic travel before restrictions are lifted on international flights. However, in Morocco and Egypt, international flights resumed earlier than domestic ones. This may relate to their proximity to Europe, and consequently international flights reflecting market conditions in the catchment area.

Fig. 7.

Forecast recovery times for domestic and international flights.

The shape of recovery also differs across countries (see Fig. 7). In most cases, aviation markets are likely to experience a V-shaped rebound, which may improve air transport businesses’ confidence in current and future profitability. This type of recovery pattern is preferable after a crisis because the recession period will be sharp but short, as witnessed in Tanzania, Nigeria, Kenya and Rwanda. Pearce (2012) also finds that air transport markets in developing economies experienced a V-shaped rebound following the 2008/9 global financial crisis.

An alternative scenario is a U-shaped rebound, as exhibited in the international flights markets of South Africa and Mauritius. In a U-shaped recovery, with a longer flat stretch at the bottom, recovery will take longer, which may mean that the air transport market will not immediately begin to recover after the low point of the recession. There are several reasons why this may occur. First, states that take longer to control surges in coronavirus cases may have to delay reopening their economies. In addition, if many businesses end up going bankrupt during periods of shutdown or are otherwise unable to reopen, there will be more economic dislocation. Finally, passengers may not be ready to start travelling when flights begin to operate again if they have not regained confidence. Abdullah et al. (2020) explain that trip purpose, mode choice, distance travelled and frequency of travel differ significantly since the pandemic compared with the period prior to its outbreak. Similarly, according to the OECD (2020), prolonged international travel restrictions, contractions in economic activities and changes in transportation behaviour will hinder fast restoration of pre-pandemic demand levels, even after countries have lifted their lockdowns and domestic travel restrictions. However, passengers’ willingness to travel may be restored if infection concerns can be reduced through vaccinations and greater awareness of air travel safety (Kim and Sohn, 2022).

In general, fluctuations in the air transport market relating to the pandemic may be considered as a cyclical business process rather than a structural change to the market. Gudmundsson et al. (2021) suggest that the COVID-19 recession will make temporary corrections to previous growth levels and will be transitory rather than permanent for the air transport industry. Similarly, Pearce (2012) finds that the air transport industry tends to bounce back fairly predictably to similar levels following major shocks. Dobruszkes and Van Hamme (2011) also indicate that the dynamics of the air transport market during the global financial crisis 2008/9 and its recovery path exhibited cyclical characteristics.

5. Conclusion

COVID-19 is having multilayered impacts on African economies and the aviation industry. Countries are implementing various measures to help the industry survive the pandemic and facilitate resumption of air transport to pre-COVID-19 levels. However, air transport stakeholders still have concerns about the state of markets, the timing of recovery and recouping long-haul traffic. These concerns must be addressed in order to restore passengers’ confidence in travelling, create air travel safety awareness and determine when to expect recovery.

This study has two central aims: to estimate the immediate and long-term effects of COVID-19 on the air transport markets of nine African countries, and to forecast timescales for recovery of domestic and international flights. To realise these objectives, two related methods are applied – intervention analysis and SARIMAX – using monthly time-series data from August 2003 to December 2021.

The empirical results show that air transport is significantly elastic to the pandemic. Lockdowns, travel restrictions and ensuing economic crises have resulted in reduced demand for air transport services. The combination of reduced travel demand, supply shocks and uncertainty about the long-term outlook create ambiguous prospects for airline companies.

The analysis highlights that the immediate effects of the pandemic were higher in Morocco, Egypt, Mauritius and South Africa than in the other countries in the sample. Morocco, Egypt and Mauritius are the top tourist destinations in the region, and South Africa is the economic and air-transport hub for southern Africa, so air travel in these countries may be considered to be an essential mode of transport. However, the pandemic's long-term effects will be considerably more severe than its immediate effects, with significant differences across countries. Furthermore, more significant deviations are observed across countries in the timing of the effects (immediate versus long-term) than in types of markets (domestic versus international). This may relate to changing passenger behaviour following the COVID-19 crisis, the availability of alternative transport modes, trends in the pandemic and vaccination progress in each country.

Estimates of recovery times show that air transport recovery will take on average 28 months (≈2.3 years) for domestic and 34 months (≈2.8 years) for international flights, starting from 2020. Tanzania's domestic flights are likely to recover quickest (13 months), followed by Kenya (22 months) and Ghana (24 months), while for international flights, Morocco is likely to have the shortest recovery period ( 2.3 years), followed by Egypt ( 2.6 years). This is in line with Gudmundsson et al.’s (2021) empirical estimate that world recovery of passenger demand to pre-COVID-19 levels will take 2.4 years. In general, the volatility of the air transport market following the outbreak of COVID-19 can be considered to be a cyclical business case rather than a structural change to the market. However, this does not mean that the market will be unaffected by behavioural changes by air transport passengers, accelerated by the transformation toward an e-society.

This study may have managerial and policy implications for airlines and other industries. It may help airlines design effective recovery plans. Forecasted recovery periods can serve as a reference point to outline strategies to resume flights and restore passenger confidence. From a policy perspective, it may facilitate the implementation of industry support programs within the forecasted timeline.COVID-19 has been episodic, so airlines are having to make rolling changes in response to unpredictable state measures. Moreover, further research is important to continuously monitor passengers' behavioural changes, industry responses and governmental policies, and to share relevant recommendations, as the COVID-19 crisis is not yet over. This study estimates the effects of the pandemic on the aviation industry and forecasts timescales for recovery. Future research might examine the pandemic's influence in accelerating the transformation towards an e-society, and its implications for post-pandemic air transport markets. Furthermore, it was not possible to estimate the change in the demand side of the market due to lack of data. In this paper, the supply side of the market is analysed specifically in terms of passenger flights. Incorporating the demand side of the market and cargo flights would be a useful insight for future research.

CRediT author statement

Tassew Dufera Tolcha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, & Writing.

Footnotes

SRS Analyzer is a subscription-based air transport database.

Appendix.

Appendix A1. Immediate and long-term effects of COVID-19 on domestic and international flights

| Pre-COVID-19 mean | Immediate effect | Long-term effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Nigeria | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Kenya | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Ghana | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Mauritius | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Rwanda | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Tanzania | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Morocco | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

| Egypt | ||||

| Domestic | * | * | ||

| International | * | * | ||

Notes: * statistically significant at the 1% level; ** statistically significant at the 5% level.

Appendix A2. Descriptive statistics of flight frequencies

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | Observations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic flights | overall | |||||

| between | ||||||

| within | T-bar | |||||

| International flights | overall | |||||

| between | ||||||

| within | ||||||

Appendix A3. African and worldwide examples of direct government support for airlines

| Government support (financial measures) | |

|---|---|

| American Airlines | $5.5 billion treasury loan |

| Lufthansa | $10.6 billion equity injection & convertible bonds |

| Alitalia | $3.5 billion injections of fresh capital |

| Air France–KLM | $8 billion government-backed loans & $4 billion loans and equity |

| Qatar Airways | $2 billion equity injection |

| Korean Air | $1 billion loans & grants |

| Cathay Pacific | $5 billion fresh capital & bridging loan facilities |

| South African Airways | $650 million equity injection |

| Royal Air Maroc | $624.8 million state-guaranteed loan |

| Kenya Airways | $500 million equity injection |

| Egyptair | $191 million long term financing loan |

| Air Côte d’Ivoire | $24 million injection in terms of grant |

| RwandAir | $152 million rescue loan |

Source: IATA (2020b), Bloomberg, FlightGlobal, African Development Bank (2021)

Appendix A4. Air Namibia's flight suspension and liquidation

Appendix A5. Residual distribution test of the model

Appendix A6. Portmanteau test of the model -case of Morocco

Appendix A7. Diebold-Mariano forecast comparison test

| MSE |

Difference | S(1) | P_value | Remark | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model II | Model I | |||||

| Morocco | 0.2558 | 0.5132 | −0.2574 | −2.88 | 0.004 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Egypt | 0.2831 | 0.4962 | −0.2131 | −3.61 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Ghana | 0.3091 | 0.4885 | −0.1794 | −2.72 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Kenya | 0.1883 | 0.3764 | −0.1881 | −2.15 | 0.002 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Mauritius | 0.3051 | 0.5730 | −0.2679 | −3.07 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Nigeria | 0.3180 | 0.6030 | −0.2850 | −3.71 | 0.004 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Rwanda | 0.4067 | 0.6481 | −0.2414 | −3.16 | 0.001 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| S. Africa | 0.1904 | 0.3561 | −0.1657 | −1.74 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Tanzania | 0.2052 | 0.4026 | −0.1974 | −2.02 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

: Forecast accuracy is equal.

| MSE |

Difference | S(1) | P_value | Remark | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model II | Model III | |||||

| Morocco | 0.3618 | 0.6122 | −0.2504 | −5.64 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Egypt | 0.2906 | 0.5531 | −0.2625 | −4.09 | 0.003 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Ghana | 0.1907 | 0.3724 | −0.1817 | −3.74 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Kenya | 0.2835 | 0.4792 | −0.1957 | −2.47 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Mauritius | 0.2778 | 0.5902 | −0.3124 | −4.16 | 0.003 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Nigeria | 0.3836 | 0.6172 | −0.2336 | −3.91 | 0.002 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Rwanda | 0.3357 | 0.5906 | −0.2549 | −3.04 | 0.001 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| S.Africa | 0.2855 | 0.5146 | −0.2291 | −3.01 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

| Tanzania | 0.3001 | 0.5022 | −0.2021 | −2.27 | 0.000 | Model_II is the better forecast |

: Forecast accuracy is equal.

Appendix A8. Autocorrelations of residuals

References

- Abate M., Christidis P., Purwanto A.J. Government support to airlines in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah M., Dias C., Muley D., Shahin M. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abouk R., Heydari B. vol. 136. AFRAA; Nairobi, Kenya: 2021. The immediate effect of COVID-19 policies on social-distancing behavior in the United States; pp. 245–252. (Public Health Reports). 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- African Development Bank COVID-19 pandemic offers African aviation a chance to reset. 2020. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/covid-19-pandemic-offers-african-aviation-chance-reset-39752 afdb.org, 4 December.

- Andreana G., Gualini A., Martini G., Porta F., Scotti D. The disruptive impact of COVID-19 on air transportation: an ITS econometric analysis. Res. Transport. Econ. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2021.101042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Box G.E.P., Tiao G.C. Intervention analysis with applications to economic and environmental problems. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1975;70(349):70–79. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1975.10480264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Box-Steffensmeier J., Freeman J., Hitt M., Pevehouse J. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2014. Time Series Analysis for the Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- CAPA Government ownership is the default position for Africa. 2016. https://cutt.ly/xTCrmmD CAPA [website], 30 May.

- Chatfield C. first ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC; London: 2000. Time-Series Forecasting. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.H., Freedman D.O., Visser L.G. COVID-19 immunity passport to ease travel restrictions? J. Trav. Med. 2020;27(5) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa085. art. taaa085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerny A.I., Fu X., Lei Z., Oum T.H. Post pandemic aviation market recovery: experience and lessons from China. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio-Chanona R.M., Mealy P., Pichler A., Lafond F., Farmer J.D. Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: an industry and occupation perspective. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Pol. 2020;36 doi: 10.1093/oxrep/graa033. Supp. 1), S94–S137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobruszkes F., Van Hamme G. The impact of the current economic crisis on the geography of air traffic volumes: an empirical analysis. J. Transport Geogr. 2011;19(6):1387–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dube K., Nhamo G., Chikodzi D. COVID-19 pandemic and prospects for recovery of the global aviation industry. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders W. 2008. Applied Econometric Time Series. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons) [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2020;29(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson S.V., Cattaneo M., Redondi R. Forecasting temporal world recovery in air transport markets in the presence of large economic shocks: the case of COVID-19. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;91 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.102007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmels J.P.W., Qureshi S.A., Brurberg K.G., Gravningen K.M. Norwegian Institute of Public Health; Oslo: 2021. COVID-19: Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 [Langvarige Effekter Av Covid-19. Hurtigoversikt 2021] [Google Scholar]

- IATA . IATA transport press briefing; 2020. Air passenger market analysis, COVID-19.https://cutt.ly/HTCpIfX December. [Google Scholar]

- IATA . Aviation Relief for African Airlines Critical as COVID-19 Impacts Deepen. IATA press release; 2020. https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-04-23-02/ 23 April. [Google Scholar]

- IATA Moderate rebound in September passenger demand. IATA transport press briefing. 2021 https://cutt.ly/JTnML7S 3 November. [Google Scholar]

- IEA . Changes in Transport Behaviour during the Covid-19 Crisis. International Energy Agency; 2020. https://www.iea.org/articles/changes-in-transport-behaviour-during-the-covid-19-crisis 27 May. [Google Scholar]

- InterVISTAS . Study Report for African Union Commission (AUC) IATA consulting by InterVISTAS and Simplicity; Geneva: 2021. Continental study on the benefits of the SAATM and communication strategy for SAATM advocacy. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Sohn J. Passenger, airline, and policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis: the case of South Korea. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2022;98 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin W., Fernando R. The global macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19: seven scenarios. Asian Econ. Pap. 2021;20(2):1–30. doi: 10.1162/asep_a_00796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L., Im J., Fu X., Kim H., Zhang Y.E. Proximal and distal post-COVID travel behavior. Ann. Tourism Res. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19) OECD Publishing; Paris: 2020. COVID-19 and the aviation industry: impact and policy responses. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce B. The state of air transport markets and the airline industry after the great recession. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2012;21:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2011.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce B. COVID-19: cost of air travel once restrictions start to lift. IATA Policy Analysis Report. 2020 https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/covid-19-cost-of-air-travel-once-restrictions-start-to-lift/ 5 May. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.F. Forecasting in the presence of large shocks. J. Econ. Dynam. Control. 1996;20(9–10):1581–1608. doi: 10.1016/0165-1889(96)00911-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shakibaei S., De Jong G.C., Alpkökin P., Rashidi T.H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel behaviour in Istanbul: a panel data analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021;65 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamshiripour A., Rahimi E., Shabanpour R., Mohammadian A. How is COVID-19 reshaping activity-travel behavior? Evidence from a comprehensive survey in Chicago. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100216. https://10.1016/j.trip.2020.100216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Wandelt S., Zhang A. How did COVID-19 impact air transportation? A first peek through the lens of complex networks. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]