Abstract

We have cloned a gene of Myxococcus xanthus with similarities to the permease for glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) of other bacteria. Expression of the gene increased significantly during the first hours of starvation. Swarming of the wild-type strain was inhibited and aggregation was delayed by G3P. Conversely, a ΔglpT strain aggregated even on rich medium. These results indicate that G3P may function to regulate the timing of aggregation in M. xanthus.

Myxococcus xanthus is a soil-dwelling bacterium that exhibits a complex developmental cycle upon starvation. After depletion of nutrients, cells migrate by gliding on a solid surface and pile up at certain points, where they create colored macroscopic structures known as fruiting bodies. Inside, the cells differentiate into dormant cells, the myxospores, which are resistant to several extreme environmental conditions (4).

A decade ago, it was found that M. xanthus possesses a family of eukaryotic-type protein serine/threonine kinases (28). Several protein kinases have been characterized (8, 18, 23, 27). These findings have revealed that phosphorylation of certain proteins must be an important event in the regulation of the developmental cycle. We reasoned that there must be other proteins that dephosphorylate the substrates phosphorylated by the kinases, reversing their action. These proteins will have phosphatase activity.

In order to identify and isolate genes that encode phosphatases, we constructed a library of M. xanthus DZF1 chromosomal DNA partially digested with Sau3AI (fragments of 3 to 4 kb) in pUC19 (25) digested with BamHI and dephosphorylated. The library thus constructed was used to transform Escherichia coli DH5 (7), and positive strains were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (16) containing 50 μg of ampicillin and 40 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) per ml. Because BCIP is a substrate for phosphatases, positive colonies should exhibit a blue color.

After analyzing more than 20,000 clones, 23 blue colonies were obtained. One of the clones was sequenced using the dideoxy terminator method (21) in an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer. Appropriate oligonucleotides were designed as primers. Analysis of the sequence revealed that this clone contained an open reading frame (ORF) with 96% of the codons using either G or C as the third base, a peculiarity of M. xanthus genes (12). The initiation codon was identified based on the observation that it is the first ATG that occurs after a termination codon in the same reading frame. In addition, a putative ribosome-binding site (AGAGG) is located seven bases upstream of the initiation codon. This ORF encoded a protein with a molecular weight of 51,736.

Comparison of the protein with others in the database by using the FASTA program, version 3.3t06 (20), revealed that it was very similar to the permease for glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) of other bacteria. For that reason, the gene was designated glpT. The M. xanthus GlpT protein exhibits 25.4% identity with the permease of Bacillus subtilis (19) and 24.6% with that of Vibrio cholerae (9). The respective similarities are as high as 40% if functionally similar amino acids are considered. This homology extended throughout the protein. M. xanthus GlpT is also a very hydrophobic protein, and as many as 12 stretches of amino acids that can potentially function as transmembrane domains were observed. It should be noted that other GlpT proteins also contain 12 transmembrane domains (5). The nucleotide sequence of the glpT gene has been deposited in the GenBank database with accession number AF157828

glpT is developmentally regulated.

In order to examine the temporal expression of the glpT gene, a strain bearing an M. xanthus glpT promoter fusion to the E. coli lacZ gene was constructed. A BamHI site was created in the glpT gene by PCR using the primer 5′-CCAGGGATCCAGCGACGACATGCAGC-3′, which anneals at positions 839 to 864, and the reverse primer 5′-AAACAGCTATGACCATG-3′, which anneals at the vector. The 0.85-kb amplified fragment was digested with XbaI and BamHI and ligated to pBluescript SK+ digested with the same enzymes. The plasmid thus obtained was designated pBS17Bam. This plasmid was sequenced to confirm that the BamHI site created in glpT was in the same reading frame as the BamHI site of the lacZ gene in plasmid pKM005 (15). Plasmid pBS17Bam was digested with XbaI and BamHI, and the 0.85-kb fragment was ligated to pKM005 digested with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid was designated pGLPZY. Finally, the kanamycin resistance gene was obtained by digestion of pUC7Skm(Pst−) (kindly provided by S. Inouye, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) with SalI, and the 1.3-kb fragment was inserted into the unique SalI site of pGLPZY. This final plasmid, pGLPZYkan, was introduced into M. xanthus by electroporation (13).

Several kanamycin-resistant colonies were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization to confirm that they bore the fusion. DNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin, and hybridization was carried out at 42°C in 50% formamide under the conditions reported previously (11). A kit for color detection with Nitro Blue Tetrazolium-BCIP was used. The strain thus obtained was designated glpZY. The glpZY strain was then plated in several media containing different concentrations of nutrients, and β-galactosidase activity was quantified using ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as a substrate, as previously described (14).

For the preparation of cell extracts, several 20-μl drops of concentrated cultures containing 2 × 1010 cells/ml were spotted on the appropriate medium, either CTT (10), 1/2CTT (identical to CTT medium but containing only half as much Bacto-Casitone), or CF agar (6). After incubation, cells were harvested by scraping off the cells on the surface of the plates. Vegetative cells were then resuspended in 200 μl of TM buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 8 mM MgSO4) and disrupted by sonication. Fruiting bodies were resuspended in 200 μl of glass beads equilibrated in TM buffer and sonicated as described previously (18). After sonication, cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The amount of protein in the supernatants was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay.

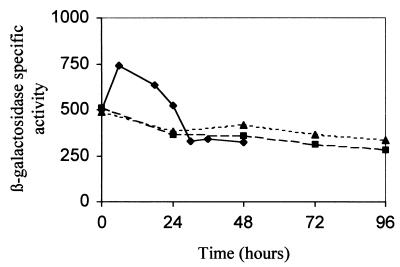

As shown in Fig. 1, on rich media (CTT and 1/2CTT), initial levels of β-galactosidase activity were quite high and then decreased slowly with incubation. In contrast, on CF medium, the levels of β-galactosidase activity increased immediately after spotting reaching a maximum at 8 h. Later, expression dropped until it reached the same level as observed for vegetative growth again. Hence, it can be concluded that glpT is expressed during vegetative growth, but its level of expression increases at the onset of development.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of expression of the glpT gene in CTT (■), 1/2CTT (▴), and CF (⧫) agar media. β-Galactosidase specific activity is expressed as nanomoles of ONP produced per milligram of protein in 1 min. The results shown are the average of three experiments.

G3P inhibits swarming and aggregation of M. xanthus.

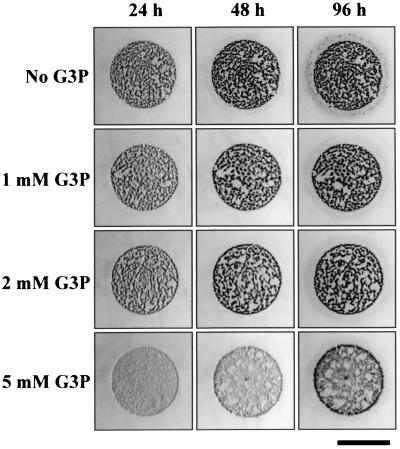

The effect of the addition of several concentrations of G3P to different culture media on the vegetative growth and development of the wild-type strain was also analyzed. The most evident effect of G3P on M. xanthus was a reduction of the swarming ability of the bacterium. A decrease in the diameter of the drops after incubation correlated with increasing concentration of G3P in all of the media tested. This inhibition was especially pronounced on rich media. As an example, the diameter of the drops after 1 week of incubation at 30°C on CTT medium containing 4 mM G3P was 11 mm, while the diameter observed on CTT with no G3P added was 20 mm (the original diameter of the drops was approximately 6 mm). On CF medium, on which M. xanthus follows the developmental cycle, the effect on swarming is not as dramatic (the diameter of the drops was reduced only from 12 to 9 mm on a medium containing 4 mM G3P). However, it was clearly observed that aggregation and fruiting body formation on CF medium containing G3P was delayed (Fig. 2). The addition of 1 mM G3P delayed aggregation by approximately 8 h, 2 mM G3P by 24 h, and 5 mM G3P by more than 3 days (Fig. 2). In the presence of 5 mM G3P, the fruiting bodies appeared quite abnormal and transparent (Fig. 2), although they contained myxospores (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of G3P on aggregation and fruiting body formation of the M. xanthus wild-type strain. Drops containing 2 × 1010 cells/ml were spotted on CF agar containing different concentrations of G3P. Bar, 5 mm.

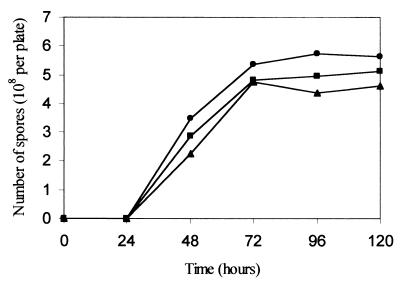

The addition of G3P, however, did not seem to significantly affect sporulation. Comparison of the number of myxospores produced by the wild-type strain on CF medium containing 2 mM G3P to CF medium containing no G3P revealed that the timing of sporulation was almost identical in both media (Fig. 3). However, the final yield of myxospores was slightly higher in the medium containing G3P.

FIG. 3.

Sporulation of wild-type strain on CF agar containing 2 mM G3P (●) or no G3P (■) compared with sporulation of the ΔglpT strain on CF agar without G3P (▴). The results shown are the average of three experiments. Ten drops (20 μl each) were spotted on an 9-cm petri dish containing CF agar. At different times, the fruiting bodies from one plate were harvested and resuspended in 200 μl of TM buffer. Fruiting bodies were dispersed, and rod-shaped cells were disrupted by sonication. Myxospores were counted in a Petroff-Hausser chamber.

Phenotype of a ΔglpT strain.

In order to study the role of G3P during both vegetative and developmental growth, a strain harboring a deletion in the glpT gene was constructed. For this construction, plasmid pBS17Bam (see above) was digested with KpnI and dephosphorylated. The linearized plasmid was then ligated to a 0.7-kb KpnI fragment, and the orientation was checked by digestion with SmaI. The plasmid with the correct orientation of the 0.7-kb KpnI fragment was designated pΔglp. This plasmid was linearized with BamHI and ligated to the kanamycin resistance gene obtained by digestion of pUC7SKm(Pst−) with the same enzyme. The resulting plasmid, designated pΔglpkan, was linearized with SacI for electroporation to M. xanthus. The double-crossover event was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization.

The phenotype of the ΔglpT strain was analyzed. Initially, the amount of G3P uptake by the ΔglpT strain was determined. Cells (either wild-type or ΔglpT strains) were grown in liquid CTT to an optical density at 600 nm of 1 and centrifuged. The pellets were resuspended in fresh liquid CTT containing 100 μM cold G3P. The volumes were adjusted to obtain the same optical density (0.7) for all the samples. The experiment was started by the addition of 10 μl of l-[U-14C]G3P per ml of culture. After 6 h of incubation, aliquots (100 μl) were withdrawn and diluted in 1 ml of fresh liquid CTT. These samples were immediately filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore), and the membranes were washed with 10 ml of liquid CTT. Membranes were then dried and dissolved with 200 μl of ethylene glycol monomethyl ether. Radioactivity bound to the filter was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

The results revealed that the 108 cells of the wild-type strain incorporated 436.37 ± 10.64 pmol in 1 h. In contrast, the same number of cells of the deletion strain incorporated 370.50 ± 7.10 pmol in the same time. The deletion of the glpT gene does not abolish the uptake of G3P in M. xanthus. This result is not surprising, because it is known that other bacteria possess an alternative transport system to introduce G3P, the ugp system (1, 22). While such a system has not been reported in M. xanthus, our results indicate that this bacterium must have other permeases responsible for the uptake of approximately 85% of the total G3P that cells can incorporate.

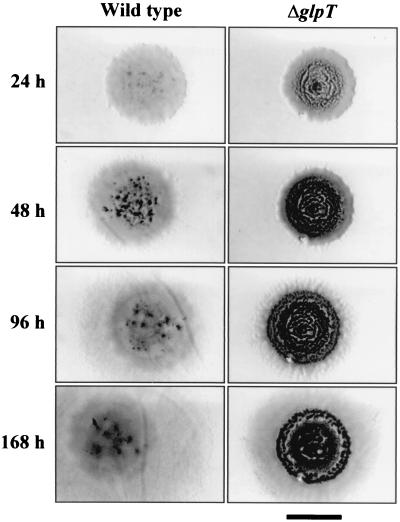

The phenotype of the deletion strain grown on solid 1/2CTT and CF media was also analyzed. On 1/2CTT agar, fruiting bodies of the ΔglpT strain were clearly observed after only 24 h of incubation (Fig. 4). These fruiting bodies were very stable on this medium, and although they appeared initially in the center of the drops, later they also appeared in the newly colonized area (Fig. 4). The morphology and opacity of the fruiting bodies were very similar to those obtained on CF agar, and they were full of spores.

FIG. 4.

Phenotype of ΔglpT strain on 1/2CTT medium compared with wild-type strain. Cells were grown in liquid CTT at approximately 3 × 108 cells/ml and concentrated to 2 × 1010 cells/ml in TM buffer. One drop (10 μl) was spotted in the center of a petri dish (5.5 cm) containing 1/2CTT agar. Bar, 5 mm.

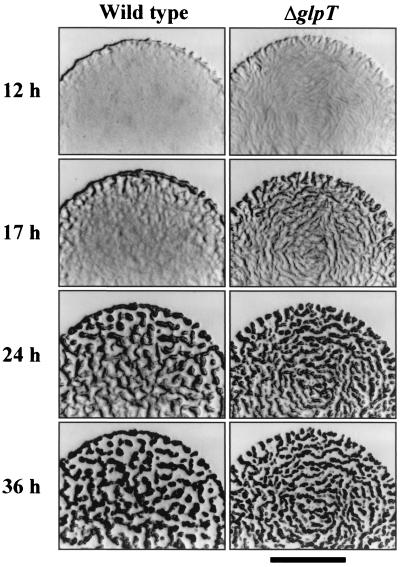

On CF agar, the ΔglpT strain could also form fruiting bodies that were very similar to those of the wild-type strain (Fig. 5), but aggregation occurred 4 to 6 h earlier in the mutant than in the wild-type strain. After a 12-h incubation, ripples could be observed in the wild-type strain on the edge of the drops. On the contrary, the ΔglpT strain formed ripples even in the center of the drops at that time. The ΔglpT strain had already aggregated at 24 h, whereas the wild-type strain originated well-formed fruiting bodies only on the edge of the drop. The center of the wild-type strain drop exhibited incompletely defined, translucent mounds. At 36 h of incubation, the aggregation stage was very similar for both strains (Fig. 5). Another remarkable difference was that the diameter of the drop of the wild-type strain after 1 week of incubation on CF agar was 12 mm, while for the ΔglpT strain the diameter was 15 mm. Both results, faster aggregation and larger diameter of the drops of the ΔglpT strain on CF agar, are exactly opposite those observed when the wild-type strain was spotted on CF medium containing G3P. In contrast, on 1/2CTT medium, the diameter of the drops of the ΔglpT strain was smaller (Fig. 4). However, it must be taken into consideration that in this medium, the wild-type strain grew vegetatively while the ΔglpT strain formed fruiting bodies and spores.

FIG. 5.

Phenotype of ΔglpT strain on CF medium compared with wild-type strain. The experiment was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Bar, 2 mm.

The timing of sporulation and the yield of spores, on the other hand, were similar in the mutant and the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). These results support our previous demonstration that G3P inhibited aggregation but had no significant effect on sporulation.

The fact that the ΔglpT strain that we have constructed does not exhibit a more dramatic phenotype is most likely due to its retained ability to transport G3P. However, several differences point to the notion that G3P inhibits swarming and aggregation. The addition of G3P to the cultures, either rich or low-nutrient media, inhibits swarming of the wild-type strain, and therefore the final size of the drops after several days of incubation is smaller in media containing G3P. There is a direct relationship between increasing concentrations of G3P in the medium and the reduction in the diameter of the drops. In contrast, the ΔglpT strain can swarm further away on CF medium. On media with low concentrations of nutrients, such as CF, the addition of G3P to the medium delayed aggregation of the wild-type strain. The ΔglpT strain, on the other hand, not only formed fruiting bodies earlier on CF medium, but also aggregated and sporulated on a medium such as 1/2CTT, in which the wild-type strain does not develop. While G3P might be used as a nutrient, so that it delays the developmental cycle, several lines of evidence demonstrate that this is not the case: (i) no significant growth on CF medium containing G3P was observed and (ii) sporulation took place with the same timing and yield of spores as in a medium with no G3P. Most likely, the effect of G3P on swarming and aggregation is due to an inhibition of gliding motility. It is possible that G3P interacts with one or several components of the gliding or chemiotactic machinery.

Finally, no significant differences were observed in the levels of the five phosphatases reported in M. xanthus (26) between the wild-type and the ΔglpT strains.

G3P must be produced by the activity of phospholipases on phospholipids, the activity of which increases during the first hours of development (17), a time that coincides perfectly with the maximum levels of expression of the glpT gene. As a result of the action of phospholipases, free fatty acids will appear in addition to G3P. These free fatty acids, known as autocides, have been reported to induce autolysis of M. xanthus (24), and branched-chain fatty acids constitute the E factor, a signal whose transmission is necessary for the completion of the developmental cycle (3). This signal is produced at 5 h of starvation (2).

Our results clearly indicate that G3P, the other product of phospholipase activity, represents a new type of small molecule that somehow regulates the timing of development of M. xanthus.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Takayama (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) for critical reading of the manuscript and S. Inouye (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) for kindly providing plasmids and strains.

This work has been supported by the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior, Spain (grant numbers PB98-1359 and PB94-0781).

REFERENCES

- 1.Brzoska P, Boos W. Characteristics of a ugp-encoded and phoB-dependent glycerolphosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase which is physically dependent on the Ugp transport system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4125–4135. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4125-4135.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downard J, Ramaswamy S V, Kil K S. Identification of esg, a genetic locus involved in cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7762–7770. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7762-7770.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downard J, Toal D. Branched-chain fatty acids-the case for a novel form of cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:171–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworkin M. Recent advances in the social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:70–102. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.70-102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gött P, Boss W. The transmembrane topology of the sn-glycerol-3-phosphate permease of Escherichia coli analysed by phoA and lacZ protein fusions. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagen D C, Bretscher A P, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenetic mutants in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1978;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanlon W A, Inouye M, Inouye S. Pkn9, a Ser/Thr protein kinase involved in the development of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:459–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.d01-1871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidelberg J F, Eisen J A, Nelson W C, Clayton R A, Gwinn M L, Dodson R J, Haft D H, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Umayam L A, Gill S R, Nelson K E, Read T D, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva M D, Vamthevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishman R D, Nierman W C, White O, Salzberg S L, Smith H O, Colwell R R, Mekalanos J J, Venter J C, Fraser C M. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 2000;406:477–483. doi: 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Cell-to-cell stimulation of movement in nonmotile mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2938–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inouye S, Inouye M. Oligonucleotide-directed site-specific mutagenesis using double-stranded plasmid DNA. In: Narang S, editor. Synthesis and applications of DNA and RNA. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inouye S, Hsu M-Y, Eagle S, Inouye M. Reverse transcriptase associated with the biosynthesis of the branched RNA-linked msDNA in Myxococcus xanthus. Cell. 1989;56:709–717. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90593-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashefi K, Hartzell P L. Genetic suppression and phenotypic masking of a Myxococcus xanthus frzF defect. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:483–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroos L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. A global analysis of developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1986;117:252–266. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masui Y, Coleman J, Inouye M. Multipurpose expression cloning vehicles in Escherichia coli. In: Inouye M, editor. Experimental manipulation of gene expression. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller C, Dworkin M. Effects of glucosamine on lysis, glycerol formation, and sporulation in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7164–7175. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7164-7175.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muñoz-Dorado J, Inouye S, Inouye M. A gene encoding a protein serine/threonine kinase is required for normal development of M. xanthus, a Gram-negative bacterium. Cell. 1991;67:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson R P, Beijer L, Rutberg B. The glpT and glpQ genes of the glycerol regulon in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:723–730. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulsson A R. DNA sequencing with chain terminators inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweizer H, Argast M, Boos W. Characteristics of a binding protein-dependent transport system for sn-glycerol-3-phosphate in Escherichia coli that is part of the pho regulon. J Bacteriol. 1982;163:392–394. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1154-1163.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Udo H, Muñoz-Dorado J, Inouye M, Inouye S. Myxococcus xanthus, a Gram-negative bacterium, contains a transmembrane protein serine/threonine kinase that blocks the secretion of β-lactamase by phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:972–983. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varon M, Cohen S, Rosenberg E. Autocides produced by Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1146–1150. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1146-1150.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, and M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberg R A, Zusman D R. Alkaline, acid, and neutral phosphatase activities are induced during development in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2294–2302. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2294-2302.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Inouye M, Inouye S. Reciprocal regulation of the differentiation of Myxococcus xanthus by Pkn5 and Pkn6, eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:435–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, Muñoz-Dorado J, Inouye M, Inouye S. Identification of a putative eukaryotic-like protein kinase family in the developmental bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5450–5453. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5450-5453.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]