Abstract

Background

Pressure ulcers affect approximately 10% of patients in hospitals and the elderly are at highest risk. Several studies have suggested that massage therapy may help to prevent the development of pressure ulcers, but these results are inconsistent.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the effects of massage compared with placebo, standard care or other interventions for prevention of pressure ulcers in at‐risk populations.

The review sought to answer the following questions: Does massage reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers of any grade? Is massage safe in the short‐ and long‐term? If not, what are the adverse events associated with massage?

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (8 January 2015), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 8 January 2015), Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process Other Non‐Indexed Citations 8 January 2015), Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 8 January 2015), and EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 8 January 2015). We did not apply date or language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We planned to include all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (Q‐RCTs) that evaluated the effects of massage therapy for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Our primary outcome was the proportion of people developing a new pressure ulcer of any grade.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently carried out trial selection. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Main results

No studies (RCTs or Q‐RCTs) met the inclusion criteria. Therefore, neither a meta‐analysis nor a narrative description of studies was possible.

Authors' conclusions

There are currently no studies eligible for inclusion in this review. It is, therefore, unclear whether massage therapy can prevent pressure ulcers.

Keywords: Humans, Massage, Massage/methods, Pressure Ulcer, Pressure Ulcer/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Massage therapy for preventing pressure ulcers

What are pressure ulcers?

Pressure ulcers (also called bed sores or pressure sores) are injuries caused by constant pressure or friction. They usually affect people who are immobilised or find it difficult to move themselves, for example the elderly or paralysed. Pressure ulcers frequently occur on bony parts of the body, such as the heels and hips, and also on the buttocks. Prolonged pressure on these areas leads to poor circulation, followed by cell death, skin breakdown, and the development of an open wound ‐ the pressure ulcer. Pressure ulcers take a long time to heal ‐ and some do not heal – so, if possible, it is important to prevent them from developing.

What is massage therapy?

Massage therapy is a treatment in which parts of the body are manipulated, held, moved and have pressure applied to them. Massage therapy can increase the volume of blood in an area, improve tissue suppleness, reduce swelling due to accumulation of fluid (oedema), and boost the immune system. Some studies have suggested that massage may help prevent the development of pressure ulcers in people who are at risk of developing them, but it is not known whether it really works.

The purpose of this review

This review investigated whether massage therapy is effective when given alone, or as part of a package of care, to prevent the development of pressure ulcers. The review authors were interested in massage therapy compared with sham (pretend) massage, or compared with standard care for prevention of pressure ulcers (that is special mattresses, regular turning and reduction of pressure on the immobile patient).

Findings of this review

The review authors searched the medical literature up to 8 January 2015, but could identify no relevant trials that investigated massage therapy for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Therefore, there is currently no evidence to support or reject massage therapy as a preventative treatment for pressure ulcers. There is an urgent need for trials to investigate this area to establish whether massage therapy works and is safe.

Background

Description of the condition

Pressure ulcers, also known as bedsores or pressure sores, are regions of localised damage to the skin and deeper tissue layers affecting muscle, tendon, and bone as a result of constant pressure due to impaired mobility (Reddy 2008; Whitney 2006). Pressure on the affected area leads to poor circulation and eventually contributes to cell death, skin breakdown, and the development of an open wound. If not adequately treated, open ulcers can become a source of pain and disability, and can become infected.

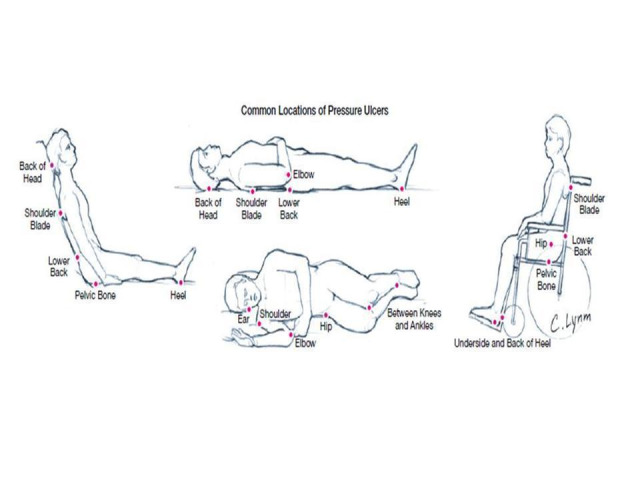

Pressure ulcers are widespread in the very old, the immobile and people of any age with medical conditions that impair sensation and /or mobility (e.g., spinal cord injury) (Moore 2014; Reddy 2006; Torpy 2003; Woodbury 2004; Zeller 2006). Reported prevalence rates for pressure ulceration vary from 8.8% to 53.2% (Davis 2001; Tannen 2006), and incidence rates from 7% to 71.6% (Scott 2006; Whittington 2004; Zhang 2013). This variability in reported prevalence and incidence rates may be partly explained by the fact that studies are conducted in different clinical settings (for example care homes or hospital), and populations (for example differences in baseline risk of ulceration. Development of pressure ulcers has been associated with a 4.5‐times greater risk of death than that for persons with the risk factors but without pressure ulcers (Staas 1991). Common sites for pressure ulcers include the sacrum (tailbone), back, buttocks, heels, back of the head and elbows (Torpy 2003; Zeller 2006) (Figure 1). Pressure ulcers are generally graded 1, 2, 3 and 4, according to the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel guidelines (EPUAP/NPUAP 2009) (see Appendix 1).

1.

From Pressure ulcers, JAMA, January 8, 2003: Vol 289, No.2

The treatment of pressure ulcers can represent a financial burden on healthcare systems, and a Dutch study found that costs associated with the care of pressure ulcers were the third highest after those for cancer and cardiovascular diseases (HCN 1999). The annual treatment cost of pressure ulcers has been estimated to range from GBP £1.4 to 2.1 billion; this is broadly equal to total UK National Health Service expenditure on mental illness, or the total cost of community health services (Bennett 2004). In the US in 2006 there were 503,300 hospital stays during which pressure ulcers were noted. In adults, the total hospital costs of these stays was USD 11 billion (Russo 2008). A study examining economic losses from pressure ulcers among hospitalised adult patients in Australia, estimated that annual opportunity costs totaled AUD 285 million (Graves 2005). Effective and adequate prevention is an important issue for patients, clinicians and policy makers.

Description of the intervention

Massage can be defined as manual soft tissue manipulation, and includes holding, causing movement, and/or applying pressure to the body (Kenny 2009). This kind of therapy is practised by accredited professionals to achieve positive physical, functional, and psychological outcomes in clients (AAMT 2012). As a complementary and alternative medical (CAM) practice, massage therapy encompasses different types of massage originating from different parts of the world (Ernst 2005). The two most common techniques are Swedish and Chinese massage (Duimel‐Peeters 2005a).

Swedish massage

Swedish massage is based on the Western concepts of anatomy and physiology, as opposed to energy work on 'meridians' in Chinese massage systems. Swedish massage involves the following techniques (Duimel‐Peeters 2005b;Ernst 2005; Moraska 2005):

Effleurage (stroking): performed using either the padded parts of the finger tips or the palm of the hand; it can be firm or light without dragging the skin. It consists of slow, rhythmic stroking hand movements moulded to the shape of the skin. It is believed to accelerate blood and lymph flow to improve tissue drainage and to reduce swelling (Duimel‐Peeters 2005b; Goats 1994; Huber 1981; Ironson 1996; Iwama 2002; Wakim 1976). Effleurage is thought to be the least harmful massage technique (Duimel‐Peeters 2005a).

Petrissage (kneading): performed with the palm of the hand and the surface of the fingers and the thumbs; this technique can only be applied to the fleshy regions of the body. In pétrissage a fold of skin, subcutaneous tissue, or muscle is squeezed, lifted, and rolled in a continuous circular motion against the underlying tissues (Goats 1994; Huber 1981; Wakim 1976). It is particularly useful for stretching contracted or adherent fibrous tissue and to relieve muscle spasm (Wakim 1976).

Tapotement (striking): consists of a rhythmic percussion, most frequently administered with the edge of the hand, a cupped hand, or the tips of the fingers. It is a stimulating movement in which the fingers, sides, or palms of the hands produce light tapping, quick pinching, or gentle slapping movements. It vibrates tissues and triggers cutaneous reflexes such as vasodilatation (widening of blood vessels), resulting in increasing muscle tone and promoting circulation of interstitial fluid (fluid surrounding tissue cells), reducing swelling and accelerating healing processes (Huber 1981; Wakim 1976).

Friction (compression): consists of an accurately‐delivered penetrating pressure applied in a small, localised area with the hands or fingers. It is a very effective way to break up adhesions or contracted connective tissue (Goats 1994; Wakim 1976).

Vibration (shaking): consists of a fine, gentle trembling movement of the tissues, and is performed by the hand or fingers in contact with the skin. In this technique the palm of the hand is often used on the part of the body or limb being treated.The purpose of vibration is to facilitate muscle relaxation and increase circulation (Benjamin 1996; Fritz 1995).

Chinese massage

Chinese massage therapy, also called Tui na, is believed to have originated around 2700 BC. It was practiced in tandem with acupuncture, acupressure and use of various Chinese medicinal herbs, and, therefore, formed one of the essential parts of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). The techniques involve compression, swing, friction, vibration, percussion, pinching and grasping and joint manipulation (CMT 2013).

Compression (pressure): applied by the fingers, limbs and palms to execute motions like nipping, pressing, stepping and twisting.

Friction (also known as rubbing, pushing, gliding and wiping): carried out to create heat on the body surface and improve the circulation underneath. Small, rhythmic circular movements are used for abdominal problems and gross scrubbing motions are used for the chest, limbs and back.

Swing (also named finger‐pushing, kneading and rolling): this is a common technique in TCM massage by pushing with one finger operation.

Joint manipulation (rotation, pulling): actions assist in increasing the range of joint motion and flexibility of the limbs and spine.

Percussion with finger tapping: this technique is used on the head, abdomen and chest regions; fist striking is used for the back, and palm patting for the waist, hip and limbs.

Pinching and grasping (rhythmic picking up and squeezing of the soft tissues): consists of twisting, holding, kneading and pinching with the operator's fingers.

Vibration (rapid vibration, shaking and rocking a selected region): resumes Qi movement, to get rid of stagnation and to enhance gastrointestinal functioning.

The cost of massage therapy is minimal when compared with the cost of some medications and other conventional treatments (Corbin 2005). Massage is widely considered to be safe for use in the general population, although adverse events have been reported. For example, one study reported that massage had caused some minor discomfort, but no major side‐effects occurred during the treatment session (Cambron 2007).

For the purposes of this review the term 'massage therapy' incorporates both western (Swedish) and Chinese techniques.

How the intervention might work

Massage is known to have the following advantageous effects that may help to prevent pressure ulcers; encouraging hyperaemia (localised increase in amount of blood) as a consequence of histamine release; increasing tissue suppleness; relaxing muscle tone; increasing parasympathetic activity; reducing oedema; relieving subcutaneous scar tissue; and activating mast cells (Olson 1989; Duimel‐Peeters 2005a; Duimel‐Peeters 2005b). However other authors have pointed out that massage might have adverse effects through the application of shear forces on vulnerable skin (NICE 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Several investigators have suggested that massage therapy might be helpful in preventing pressure ulcers (Duimel‐Peeters 2005a; Olson 1989), therefore, it is important to undertake a comprehensive assessment of all the available high level data on the benefits and harms of massage intervention for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Furthermore, the inclusion of massage therapy as part of a prevention strategy adds to the overall cost of the strategy, so it is important to explore whether use of this therapy provides potential benefit to patients.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the effects of massage compared with placebo, standard care or other interventions for prevention of pressure ulcers in at‐risk populations.

The review sought to answer the following questions:

Does massage reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers of any grade?

Is massage safe in the short‐ and long‐term? If not, what are the adverse events associated with massage?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (Q‐RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. We excluded cluster RCTs and cross‐over designs.

Types of participants

We planned to include trials involving people in any care setting, of any age or sex, without a pressure ulcer.

Types of interventions

The primary intervention was massage therapy applied to the skin with the aim of preventing the development of a pressure ulcer. Likely comparisons were with sham massage or no massage.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The proportion of people developing a new pressure ulcer of any grade at any point during the study (pressure ulcers are defined as a localised injury to the skin, underlying tissue, or both, usually over a bony prominence) (EPUAP/NPUAP 2009; Moore 2014).

Secondary outcomes

The severity of the new pressure ulcer (ulcer grade and volume).

Costs of intervention.

Pain (assessed using any validated pain scales).

Quality of life (assessed using any validated assessment tool, such as the Nottingham Health Profile scales (McKenna 1981)).

Adverse events associated with massage.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases in January 2015:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 8 January 2015);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 1);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 8 January 2015);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, 8 January 2015);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 8 January 2015); and

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 8 January 2015).

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) using the following search strategy:

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Massage] explode all trees #2 massag*:ti,ab,kw #3 #1 or #2 #4 MeSH descriptor: [Pressure Ulcer] explode all trees #5 (pressure next (ulcer* or sore* or injur*)):ti,ab,kw #6 (decubitus next (ulcer* or sore*)):ti,ab,kw #7 ((bed next sore*) or bedsore):ti,ab,kw #8 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 #9 #3 and #8

We adapted this strategy to search Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the EMBASE search with the Ovid EMBASE filter developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2013). We did not restrict studies with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

We searched the following clinical trials registries:

ClinicalTrials,gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) (8 January 2015)

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) (8 January 2015)

EU Clinical Trials Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/) (8 January 2015)

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of all retrieved, potentially‐relevant publications for reports of any potentially‐relevant trials and contacted experts in the field to ask for information relevant to this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Independently, two review authors reviewed titles and abstracts identified by the searches. We retrieved full reports of all potentially relevant trials for further assessment of eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. The first two review authors independently assessed all full text reports against the inclusion criteria; those reports not meeting the inclusion criteria were added to the table of excluded studies with full reasons for their exclusion noted. Any differences in opinion were resolved by discussion with a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors planned to extract data independently using a data extraction sheet; differences in opinion were to be resolved through discussion or consultation with a third review author if consensus could not be reached. Extraction of the following information was planned:

authors; title; year of publication;

country of study; setting of study (e.g. primary care);

characteristics of participants;

number of participants with new pressure ulcers; stage of new pressure ulcers;

inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for participants;

number of participants randomised to each trial arm; method of randomisation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and trial personnel;

setting of treatment;

details of the intervention (treatment and comparator); co‐intervention(s);

details of personnel delivering the intervention;

duration of intervention; frequency of intervention; duration of follow‐up;

outcome data for primary and secondary outcomes;

number of participants completing; number of withdrawals; reasons for participant withdrawal;

statistical methods used in the analysis; methods for handling missing data (per‐protocol or intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors planned to assess the methodological quality of the included studies independently using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011a). This tool covers six specific domains namely; sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (see Appendix 2). We planned to assess blinding and completeness of outcome data for each outcome separately. Disagreements were to be resolved by consultation with a third review author

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to perform meta‐analyses according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration, depending on the available data and event rate (Higgins 2011a), using the software package Review Manager (RevMan) 5.2 provided by the Cochrane Collaboration (RevMan 2011). For dichotomous data, we planned to calculate the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous variables, we planned to present mean differences (MD) with corresponding 95% CIs, or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs, depending upon the measures used across the studies. We planned to analyse time‐to‐event data (e.g. time to ulcer development) as survival data. The most appropriate way of summarizing time‐to‐event data is to use methods of survival analysis and express the intervention effect as a hazard ratio. (Deeks 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include cluster‐randomised trials (C‐RCTs) and studies with cross‐over designs because these are not appropriate designs to use in answering this research question. C‐RCTs are commonly used when it is appropriate or necessary to randomise groups of individuals and cross‐over designs are only appropriate when the intervention has a temporary effect and is used in the treatment of a stable condition.

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing from reports, we planned to attempt to contact the study authors to obtain missing information. If this was not successful, we would decide whether the data were missing 'at random' or 'not at random'.

Data are said to be 'missing at random' if the reason for being missing is unrelated to actual values of the missing data. For instance, if some quality‐of‐life questionnaires were lost in a postal system, this would be unlikely to be related to the quality of life of the trial participants who completed the forms. Data are said to be 'not missing at random' if the reason that they are missing is related to the actual missing data. For instance, in a trial if participants do not attend the final follow‐up interview because they have developed a pressure ulcer or are in pain, they are more likely to contribute to missing outcome data. Such data are 'non‐ignorable' in the sense that an analysis of the available data alone will typically be biased. Publication bias and selective reporting bias lead by definition to data that are 'not missing at random', and attrition and exclusions of individuals within studies often do as well (Higgins 2011b).

If data turned out to be missing at random, we planned to analyse the available information (completer analysis). If data were regarded as not missing at random, we planned to make explicit the assumptions of any methods we used to deal with the missing data, for example if the missing values were assumed to indicate a poor outcome. We planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of the assumptions we made. We planned to address the potential impact of any missing data on the findings of the review in the Discussion section (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity would be explored by the Chi2 and I2 tests. We planned to interpret Q test data with P values less than 0.10 as indicating significant statistical heterogeneity. In order to assess and quantify the possible magnitude of inconsistency (i.e. heterogeneity) across studies, we also planned to use the I2 statistic as a rough guide for interpretation (Higgins 2003); an I2 of 30% or under would indicate a low level of heterogeneity, 31% to 59% would indicate moderate heterogeneity, and values of 60% or over would indicate considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to investigate reporting biases using appropriate techniques (for example, examining funnel plot asymmetry).

Data synthesis

In future updates of this review, if suitable trials are identified for inclusion, we would undertake analysis of the data using RevMan software (RevMan 2011). We would plan to present the results with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and report estimates for dichotomous outcomes as RR, and continuous outcomes as MD or SMD. Data synthesis would depend on the quality, design and heterogeneity of the included trials. If data were not appropriate for pooling or analysis, we would undertake a narrative overview, which would be structured according to the study design that had been used. We would use a fixed‐effect model for the meta‐analysis where I2 is 30% or under, and a random‐effects model when I2 values lie between 31% to 59% we would not undertake meta‐analysis when I2 values are 60% or above.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to analyse potential sources of heterogeneity as follows: if sufficient data were available and significant heterogeneity were identified, we would undertake the following subgroup analysis: type of setting (community, inpatient, outpatient), as we hypothesized that the characteristics of patients seen in these settings may be different, and hence a source of heterogeneity.If substantial statistical or clinical heterogeneity were detected either by the I2 statistic or by observation, and could not be explained, we would not combine study results, but would present them in a descriptive summary.

Sensitivity analysis

If there were sufficient studies, we planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of study risk of bias on our results.

Results

Description of studies

We did not find any RCTs or Q‐RCTs that met the inclusion criteria.

Results of the search

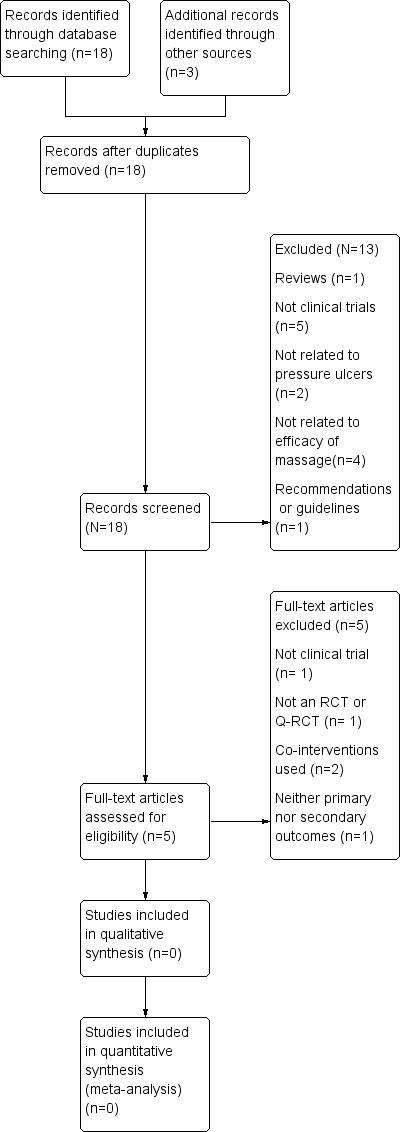

We excluded most of the citations retrieved by the searches at the title and abstract stage on the basis that the primary focus was not massage therapy for preventing pressure ulcers. We obtained full‐text papers for five studies for further assessment. None of these studies met the inclusion criteria and were added to the Characteristics of excluded studies table (Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

No studies (RCTs or Q‐RCTs) were included.

Excluded studies

The Characteristics of excluded studies table lists the reasons for the exclusion of five potentially eligible studies. In summary, one study was not a clinical trial (Duimel‐Peeters 2005); one study was not an RCT or a Q‐RCT (Acaroglu 2005); In addition, the other two studies were both cross‐over trials with a cluster randomisation (Duimel‐Peeters 2007; Duimel‐Peeters 2003). Finally Olson 1989 did not measure any of the primary or secondary outcomes of the review, being limited to the impact of massage on skin temperature.

Risk of bias in included studies

It was not possible to undertake a risk of bias assessment, because no studies met the inclusion criteria.

Effects of interventions

No studies met the inclusion criteria. Thus, neither a meta‐analysis nor a narrative synthesis of studies was possible.

Discussion

Our review highlights the lack of robust evidence for the use of massage in the prevention of pressure ulcers. We found no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐randomised trials comparing massage with placebo, standard care or with other therapies amongst people at risk of developing a pressure ulcer. We found a narrative study discussing the potential benefits of massage for this purpose (Acaroglu 2005), and three related randomised controlled trials, none of which met our inclusion criteria (Duimel‐Peeters 2003; Duimel‐Peeters 2007; Olson 1989). Two of these trials were cross‐over trials with a cluster randomisation (Duimel‐Peeters 2003; Duimel‐Peeters 2007), and one evaluated the effects of massage by measuring skin temperature at the sacral site (Olson 1989).

Consequently, although guidelines advise against the use of massage (Shahin 2009; EPUAP/NPUAP 2009; NICE 2014), there is a lack of evidence in this area. This means that we still do not know if massage has an effect when used as an intervention to prevent pressure ulcers. It is important to have an answer to this question, because massage is an intervention that is widely used by nurses to prevent pressure ulcers (Acaroglu 2005). Accordingly, an opportunity exists to trial some of the more common massage techniques against standard care to investigate whether massage is effective in the prevention of pressure ulcers.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We did not find any eligible randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs. At present, there is no evidence for either the effectiveness, or potential harms, of massage therapy when used to prevent the development of pressure ulcers. Therefore, until good quality evidence emerges, no definitive conclusions regarding massage therapy for prevention of pressure ulcers can be drawn.

Implications for research.

There is an urgent need for methodologically robust RCTs to compare massage with placebo, or standard care (such as mattresses, regular turning, and pressure relief of immobile patients) for prevention of pressure ulcers. Multicentre RCTs that can recruit larger sample sizes would be most desirable. In these trials it will be important to investigate the potential harms of massage therapy, as well as the potential benefits.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 5, 2013 Review first published: Issue 6, 2015

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to Sally Bell‐Syer for editorial advice during the preparation of this protocol. We would also like to thank the Wounds Group Editors and the peer referee for their comments (Patricia Danielsen; Hugh Macpherson; Anita Raspovic; Marialena Trivella; Joan Webster), and to the copy editor Elizabeth Royle.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81273823), Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20122327110007), Foundation of Outstanding Innovative Talents Support Plan of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (Grant No. 2012RCL01; 2012RCQ64).

Appendices

Appendix 1. NPUAP/EPUAP pressure ulcer classification

Introductory statements

This classification starts from the premise that the use of the terms 'Stage' and 'Grade' implies a natural progression from Stage/Grade 1 through to 4, which is not generally the case. The use of the term 'Category' is intended to be a neutral term, however, it is recognised that in the United States it may be more difficult to change from the use of 'Stages' to 'Categories' because of some regulations and legislation.

◆ Category I: Non‐blanchable redness of intact skin

Intact skin with non‐blanchable erythema (redness) of a localised area usually over a bony prominence. Discoloration of the skin, warmth, oedema (swelling), hardness, or pain may also be present. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching. Further description: the area may be painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler than adjacent tissue. Category I may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. May indicate 'at risk' persons.

◆ Category II: Partial‐thickness skin loss or blister

Partial‐thickness loss of dermis (skin) presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red‐pink wound bed, without slough (dead tissue). May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum‐filled or serosanguineous‐filled (fluid‐filled) blister. Further description: presents as a shiny, or dry shallow, ulcer without slough or bruising. This category should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, incontinence‐associated dermatitis, maceration, or excoriation (destruction of skin by scraping or chemicals).

◆ Category III: Full‐thickness skin loss (fat visible)

With full‐thickness skin loss subcutaneous fat may be visible, but bone, tendon, or muscle are not exposed. Some slough may be present. May include undermining and tunnelling. Further description: the depth of a Category III pressure ulcer varies according to anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput, and malleolus do not have (adipose, i.e. fat) subcutaneous tissue and Category III ulcers in these locations can be shallow. In contrast, areas of significant adiposity can develop extremely deep Category III pressure ulcers. Bone/tendon is not visible or directly palpable.

◆ Category IV: Full‐thickness tissue loss (muscle/bone visible)

Full‐thickness tissue loss that exposes bone, tendon, or muscle; slough or eschar (scab) may be present. These ulcers often include undermining and tunnelling. Further description: the depth of a Category IV pressure ulcer varies according to its anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput, and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue and ulcers in these areas can be shallow. Category IV ulcers can extend into muscle or supporting structures, or both (e.g. fascia, tendon, or joint capsule) making osteomyelitis or osteitis (inflammations of bone due to infection) likely to occur. Exposed bone/muscle is visible or directly palpable.

Additional categories for the United States of America

◆ Unstageable/unclassified: Full‐thickness skin or tissue loss‐depth unknown

Full‐thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, grey, green, or brown) or eschar (tan, brown, or black), or both, in the wound bed. Further description: until enough slough, eschar, or both, are removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth cannot be determined; but the ulcer will be either a Category III or IV. Stable (dry, adherent, intact without erythema or fluctuance, i.e. indication of infection), eschar on the heels serves as "the body's natural (biological) cover" and should not be removed.

◆ Suspected deep tissue injury

Purple or maroon localised area of discoloured intact skin or blood‐filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure, shear or both. Further description: the area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer, or cooler than the adjacent tissue. Deep tissue injury may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. Evolution may include a thin blister over a dark wound bed. The wound may evolve further and become covered by thin eschar. Evolution may be rapid, exposing additional layers of tissue, even with treatment.

Source: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel/European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. (in press)

Appendix 2. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias

1. Was the allocation sequence randomly generated?

Low risk of bias

The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random number table; using a computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots.

High risk of bias

The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, for example: sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; sequence generated by some rule based on date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by some rule based on hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear

Insufficient information provided about the sequence generation process to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

2. Was the treatment allocation adequately concealed?

Low risk of bias

Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation); sequentially‐numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

High risk of bias

Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on: using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non opaque or not sequentially‐numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure.

Unclear

Insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement, for example if the use of assignment envelopes is described, but it remains unclear whether envelopes were sequentially‐numbered, opaque and sealed.

3. Blinding ‐ was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome and the outcome measurement are not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others was likely to introduce bias.

Unclear

Either of the following.

Insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

The study did not address this outcome.

4. Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No missing outcome data.

Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias).

Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk were not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes was not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size.

Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

Reason for missing outcome data are likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes is enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size.

‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation.

Potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Unclear

Either of the following.

Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided).

The study did not address this outcome.

5. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Low risk of bias

Either of the following.

The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way.

The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon)

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported.

One or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified.

One or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect).

One or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis.

The study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

Unclear

Insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category.

6. Other sources of potential bias

Low risk of bias

The study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

High risk of bias

There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; or

has been claimed to have been fraudulent; or

had some other problem.

Unclear

There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

insufficient information provided to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; or

insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Acaroglu 2005 | Not a RCT or a Q‐RCT |

| Duimel‐Peeters 2003 | Cross over trial design |

| Duimel‐Peeters 2005 | Not clinical trial |

| Duimel‐Peeters 2007 | Cross over trial design |

| Olson 1989 | Did not address any of the reviews' primary or secondary outcomes, but considered only skin temperature |

Abbreviations

DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide cream Q‐RCT = quasi‐randomised controlled trial RCT = randomised controlled trial

Contributions of authors

Zhang Qinhong: developed, completed the first draft of, made an intellectual contribution to and approved the final version of the protocol prior to submission. Yue Jinhuan: conceived the review question, co‐ordinated the protocol development, performed part of writing or editing and advised on the protocol. Sun Zhongren: secured funding for, edited, advised on and acted as guarantor for the protocol.

Contributions of editorial base

Nicky Cullum: edited the protocol; advised on methodology, interpretation and review content and approved the final version of the review. Liz McInnes, Editor: approved the final protocol and review prior to submission. Sally Bell‐Syer: co‐ordinated the editorial process. Advised on methodology, interpretation and content. Edited the protocol and the review. Ruth Foxlee: designed the search strategy and edited the search methods section. Rachel Richardson: edited the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Wounds. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Healthp, UK.

Declarations of interest

Zhang Qinhong: none known Yue Jinhuan: none known Sun Zhongren: none known

New

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Acaroglu 2005 {published data only}

- Acaroglu R, Sendir M. Pressure ulcer prevention and management strategies in Turkey. Journal of Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing 2005;32(4):230‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duimel‐Peeters 2003 {published data only}

- Duimel‐Peeters IGP, Berger M, Halfens R, Snoeckz L. Evaluation of massage with an indifferent cream and massage with a cream that contains dimethyl sulfoxide as preventive methods for pressure sores. 13th Conference of the European Wound Management Association; 22‐24 May. Pisa, Italy, 2003:186.

Duimel‐Peeters 2005 {published data only}

- Duimel‐Peeters IG, Halfens RJ, Snoeckx LH, Berger MP. Massage for prevention of decubitus ulcer?‐‐2: Comparison of 3 interventions. Pflege Zeitschrift 2005;58(6):364‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duimel‐Peeters 2007 {published data only}

- Duimel‐Peeters 2008. Response to van Rossum's commentary on Duimel‐Peeters et al. (2007) "The effectiveness of massage with and without Dimethyl Sulfoxide in preventing pressure ulcers: a randomized, double blind cross‐over trial inpatients prone to pressure ulcers". International Journal of Nursing Studies 2008;45(1):157‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duimel‐Peeters IGP, Halfens RJG, Ambergen AW, Houwing RH, Berger MPF, Snoeckx LHE. The effectiveness of massage with and without dimethyl sulfoxide in preventing pressure ulcers: a randomized, double‐blind cross‐over trial in patients prone to pressure ulcers. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2007;44(8):1285‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossum JP. Commentary on Duimel‐Peeters et al's (2007), "The effectiveness of massage with and without dimethylsulfoxide in preventing pressure ulcers: a randomized, double blind cross‐over trial in patients prone to pressure ulcers". International Journal of Nursing Studies 2008;45(1):154‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olson 1989 {published data only}

- Olson B. Effects of massage for prevention of pressure ulcers. Decubitus 1989;2(4):32‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

AAMT 2012

- Australian Association of Massage Therapists Limited. What is massage?. Australian Association of Massage Therapists 2012; Vol. http://aamt.com.au/about‐massage/what‐is‐massage/#content, issue Accessed: 05 Jun 2012.

Benjamin 1996

- Benjamin PJ, Lamp SP. Understanding sports massage. Human Kinetics, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Bennett 2004

- Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing 2004;33(3):230‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cambron 2007

- Cambron JA, Dexheimer J, Coe P, Swenson R. Side‐effects of massage therapy: a cross‐sectional study of 100 clients. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2007;13(8):793‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CMT 2013

- Chinese Massage Therapy (CMT). Search filters. http://www.buzzle.com/articles/chinese‐massage‐therapy.html (accessed 14 October 2013).

Corbin 2005

- Corbin L. Safety and efficacy of massage therapy for patients with cancer. Cancer Control 2005;12(3):158‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davis 2001

- Davis CM, Caseby NG. Prevalence and incidence studies of pressure ulcers in two long‐term care facilities in Canada. Ostomy/Wound Management 2001;47(11):28‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2011

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group (editors). Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analysis. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Duimel‐Peeters 2005a

- Duimel‐Peeters IGP. Preventing pressure ulcers with massage?. American Journal of Nursing 2005;105(8):31‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duimel‐Peeters 2005b

- Duimel‐Peeters IGP, Halfens RJ, Berger MP, Snoeckx LH. The effects of massage as a method to prevent pressure ulcers: a review of the literature. Ostomy Wound Management 2005;51(4):70‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EPUAP/NPUAP 2009

- European Pressure Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Washington DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel 2009.

Ernst 2005

- Ernst E. The safety of massage therapy. Rheumatology 2003;42(9):1101‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fritz 1995

- Fritz S. Mosby's fundamentals of therapeutic massage. David Dusthimer, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Goats 1994

- Goats GC. Massage‐the scientific basis of an ancient art: Part 1. The techniques. British Journal of Sports Medicine 1994;28(3):149‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graves 2005

- Graves N, Birrell FA, Whitby M. Modeling the economic losses from pressure ulcers among hospitalized patients in Australia. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2005;13:462‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

HCN 1999

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Pressure ulcers. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands 1999; Vol. 23.

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson, SG, Deeks, JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011a

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Higgins 2011b

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 16: Special topics in statistics. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Huber 1981

- Huber E. When is it indicated to use massage? [Wann ist eine Massage indiziert?]. Zeitschirft für Allgemeinmedizin 1981;57:1485‐93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ironson 1996

- Ironson G, Field T. Massage therapy is associated with enhancement of the immune system’s cytotoxic capacity. International Journal of Neuroscience 1996;84(1‐4):205‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iwama 2002

- Iwama H, Akama Y. Skin rubdown with a dry towel activates natural killer cells in bedridden old patients. Medical Science Monitor 2002;8(9):555‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kenny 2009

- Kenny CW, Cohen M, Hughes T. The Effectiveness of Massage Therapy. Australian Association of Massage Therapy 2009; Vol. http://aamt.com.au/wp‐content/uploads/2011/11/AAMT‐Research‐Report‐10‐Oct‐11.pdf, issue accessed 5 June 2012.

Lefebvre 2011

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J, on behalf of the Cochrane Information Retrieval Methods Group. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

McKenna 1981

- McKenna S, Hunt S, McEwan J. Weighting the seriousness of perceived health problems using Thurstone's method of paired comparisons. Internatational Journal Epidemiology 1981;10(1):93‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2014

- Moore ZEH, Cowman S. Risk assessment tools for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006471.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moraska 2005

- Moraska A. Sports massage: a comprehensive review. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2005;45(3):370‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NICE 2014

- Pressure ulcer prevention: the prevention and management of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care. Commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. National Clinical Guideline Centre April 2014. [PubMed]

Reddy 2006

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Prevention of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296(8):974‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reddy 2008

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, Wu W, Anderson PJ, Rochon PA. Treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;300(22):2647‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2011 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Russo 2008

- Russo CA, Steiner C, Spector W. Hospitalizations related to pressure ulcers among adults 18 years and older, 2006. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: AHRQ. Statistical Brief #64 December 2008. [PubMed]

Scott 2006

- Scott JR, Gibran NS, Engrav LH, Mack CD, Rivara FP. Incidence and characteristics of hospitalized patients with pressure ulcers: State of Washington, 1987 to 2000. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery 2006;117(2):630‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SIGN 2013

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Search filters. http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html#random (accessed 7 February 2013).

Staas 1991

- Staas WE, Cioschi HM. Pressure sores‐a multifaceted approach to prevention and treatment. Western Journal of Medicine 1991;154(5):539‐44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tannen 2006

- Tannen A, Bours G, Halfens R, Dassen T. A comparison of pressure ulcer prevalence rates in nursing homes in the Netherlands and Germany, adjusted for population characteristics. Research in Nursing and Health 2006;29:588‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Torpy 2003

- Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. Pressure ulcers. JAMA 2003;289(2):254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wakim 1976

- Wakim KG. Physiologic effects of massage. In: Licht S editor(s). Massage, Manipulation and Traction. New York, NY: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, 1976:38‐43. [Google Scholar]

Whitney 2006

- Whitney JA, Phillips L, Aslam R, Barbu A, Gottrup F, Gould L, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2006;14(6):663‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whittington 2004

- Whittington KT, Briones R. National prevalence and incidence study: 6‐year sequential acute care data. Advances in Skin and Wound Care 2004;17(9):490‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Woodbury 2004

- Woodbury MG, Houghton PE. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Canadian healthcare settings. Ostomy Wound Management 2004;50(10):22‐38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zeller 2006

- Zeller JL, Lynm C, Glass RM. Pressure ulcers. JAMA 2006;296(8):1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang 2013

- Zhang QH, Sun ZR, Yue JH, Ren X, Qiu LB, Lv XL, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine for pressure ulcer: a meta‐analysis. International Wound Journal 2013; Vol. 10, issue 2:221‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

References to other published versions of this review

Shahin 2009

- Shahin ESM, Dassen T, Halfens RJG. Pressure ulcer prevention in intensive care patients: guidelines and practice. Journalof Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2009;15(2):370‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]