Abstract

Objective:

A growing literature suggests attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a heritable disorder. We evaluated children at risk for ADHD by virtue of having parents with ADHD and compared them with children of parents without ADHD to assess the degree of heritability of ADHD.

Method:

The sample for this study was derived from three longitudinal studies that tracked families with various disorders, including ADHD. Children were stratified based on presence of parental ADHD, and clinical assessments were taken to evaluate presence of ADHD and related psychiatric and functional outcomes in children.

Results:

Children with parental ADHD had significantly more full or subthreshold psychiatric disorders (including ADHD) as well as functional impairments compared to children without parental ADHD.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest that offspring of parents with ADHD are at significant risk for ADHD and its associated psychiatric, cognitive, and educational impairments. These findings aid in identifying early manifestations of ADHD in young children at risk.

Keywords: ADHD, children, heritability

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a prevalent and morbid neurobiological disorder estimated to affect at least 5% of children (Sayal et al., 2018). It has been associated with negative and costly outcomes that adversely impact all aspects of life including educational attainment (Loe & Feldman, 2007; May et al., 2021), self-esteem (Harpin et al., 2016), relationship difficulties (VanderDrift et al., 2019) as well as high rates of psychiatric comorbid disorders and addictions (Faraone et al., 2015), among many others. Considering the morbidity and dsyfunction associated with ADHD, there is a critical need for improved efforts in the identification of early manifestions of ADHD and related disorders.

Because of the well-documented genetic underpinnings of ADHD (Faraone et al., 2005), children of parents with ADHD are a potentially informative group that may provide insights on early manifestations of ADHD and its associated conditions. In addition to the genetic underpinning, the inattentive and impulsive nature of ADHD parents may also impact their children’s well-being. Although previous family and twin studies suggest that ADHD is overrepresented in parents and siblings of children with ADHD (Tistarelli et al., 2020), there is very limited information on the psychiatric presentation of children with parents who have ADHD.

A recent literature review on the subject documented an elevated risk for ADHD in children of parents with ADHD (Uchida et al., 2021), but the extant literaure on the subject comprises only four small studies with limited scopes of assessement. This state of affairs underscores the need for better powered studies on children at risk for ADHD to better understand the magnitude of risk for ADHD and related disorders. Further insight into the magnitude of the risk for ADHD and related conditions has important implications. It could aid in the early identification of children at high risk for ADHD and facilitate the development of early intervention strategies.

The main aim of this study is to assess the risk for ADHD and related disorders in children of parents with ADHD. To this end, we assessed the risk for ADHD and related disorders in opportunistic large samples of well-characterized children of parents with and without ADHD in multiple non-overlapping domains of functioning. We hypothesized that the risk for ADHD and associated disorders would be higher in children of parents with ADHD relative to controls (children with parents without ADHD). We also hypothesized that ADHD would be associated with psychopathological, cognitive, educational, and interpersonal deficits, which are well-documented correlates of ADHD. To our knowledge, this study is the largest and most comprehensive evaluation of children at risk for ADHD.

Methods

Subjects

The sample for this study was derived from three previous independent studies. The first two studies were identically designed longitudinal case-control family studies of psychiatrically and pediatrically referred youth of both sexes with and without ADHD (Biederman et al., 1992, 1999). These studies recruited male and female probands aged 6 to 17 years with and without ADHD and their first-degree biological relatives (Boys Study: N = 140 ADHD probands with N = 174 siblings and N = 280 parents, and N = 120 Control probands with N = 129 siblings and N = 239 parents; Girls Study: N = 140 ADHD probands with N = 143 siblings and N = 174 parents, and N = 122 Control probands with N = 131 siblings and N = 138 parents). Potential subjects were excluded from these two studies if they had major sensorimotor handicaps, psychosis, autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a Full-Scale IQ of less than 80.

The third study was a longitudinal case-control family study of parents with and without panic disorder and major depressive disorder who had at least one child in the age range of 2 to 6 years. The original recruitment of parents in this study (Rosenbaum et al., 2000) had been done in three groups: (1) 131 parents treated for panic disorder, their 227 children and 130 spouses, (2) 39 parents treated for major depression who had no history of either panic disorder or agoraphobia, their 67 children and 38 spouses, and (3) 61 comparison parents with neither major anxiety nor mood disorders, their 119 children and 61 spouses. Parents and adult offspring provided written informed consent to participate, and parents provided consent for offspring under the age of 18. Children and adolescents provided written assent to participate. All three studies had been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Massachusetts General Hospital.

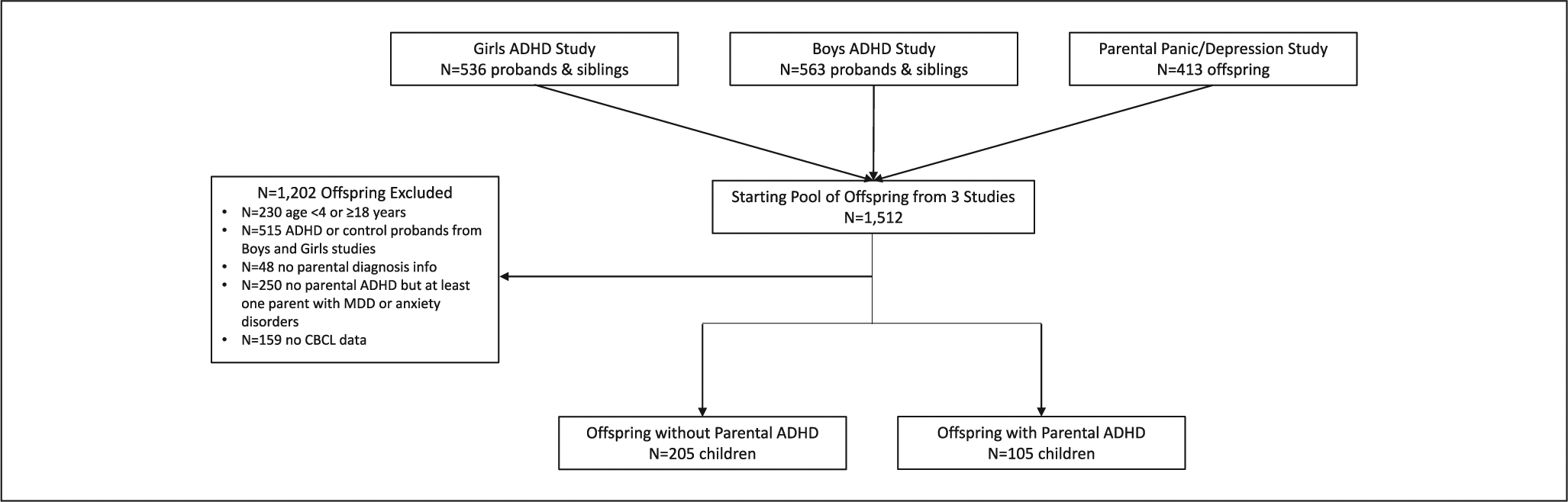

For the purpose of this analysis, we re-stratified the offspring from the three studies by the presence or absence of parental ADHD. Because the ADHD and control probands were recruited based on their diagnosis of ADHD, or lack thereof, these offspring were excluded from this analysis. Offspring that had parents with major depressive disorder (MDD) or anxiety disorders without ADHD were excluded due to the known high rates of comorbid psychopathology and dysfunction associated with these disorders. Additionally, the sample was restricted to offspring who were 4 to 17 years of age. After these exclusions (detailed description below in Results section), our final pool for analysis consisted of a total of 310 offspring (Figure 1); 205 offspring from 74 families with parental with ADHD and 105 offspring from 55 families without parental ADHD, MDD, and anxiety disorders.

Figure 1.

Diagram of analysis sample selection.

Assessment Procedures

In all three studies, adults ≥18 years of age were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (Spitzer et al., 1990) supplemented with modules from the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E) (Orvaschel & Puig-Antich, 1987) to assess childhood disorders. We made every effort to interview both parents from each family, regardless of marital status. Psychiatric assessments of children and adolescents ages 5 to 18 years of age were made using the K-SADS-E. Diagnoses of children had been based on independent interviews with mothers and direct interviews with children older than 12 years of age (Biederman et al., 2006; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2012). Data were combined such that endorsement of a diagnosis by either reporter resulted in a positive diagnosis.

All diagnostic assessments were conducted by highly selected, highly trained, and closely supervised raters. For all three studies, raters were blind to the ascertainment source of the families. To assess the reliability of our overall diagnostic procedures, we computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced, blinded, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and licensed experienced clinical psychologists diagnose subjects from audiotaped interviews made by the assessment staff. For the ADHD studies, based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was .98, and the kappa coefficients of agreement for individual diagnoses were .88 for ADHD, 1.0 for major depression, 0.95 for mania, 1.0 for separation anxiety, 1.0 for agoraphobia, and 0.95 for panic disorder. For the parental panic and major depressive disorder study, based on 173 interviews, the kappa coefficients of agreement for individual diagnoses were .86 for major depression, .96 for panic disorder, .90 for agoraphobia, .83 for social phobia, .84 for simple phobia, and .83 for generalized anxiety disorder.

We assessed socioeconomic status (SES) with the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (Hollingshead, 1975), which included information about both parents’ educational levels and occupations. A higher score indicates being of lower socioeconomic status.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The parent of each child completed the 1991 version of the CBCL for children ages 4 to 18 years. (Achenbach, 1991) The CBCL is a 113-item parent-rated assessment of a child’s behavior problems and social competence in the past 6 months. Raw scores are calculated and used to generate T-scores for eight clinical subscales, two composite scales, one total scale, and four competence scales. T-scores ≥70 are in the clinical range for the clinical subscales and T-scores ≥64 are in the clinical range for the composite scales and total scale.

Social Functioning

Social functioning was assessed in three ways: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Piersma & Boes, 1997), Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA) (John et al., 1987), and Family Environment Scale (FES) (Moos, 1990; Moos & Moos, 1994). The GAF is a clinician’s rating of an individual’s overall level of functioning based on psychological, social, and occupational functioning, where higher ratings indicate a higher level of functioning. The SAICA is a semi-structured, parent-rated interview to assess social functioning in the domains of activities, peer relations, family relations, and academic performance, where higher scores indicate worse social functioning. The FES is a parent-rated scale measuring the social-environmental characteristics of a family including the relationship dimensions of cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict, where higher scores indicate cohesion and expressiveness and lower scores indicate conflict.

Neurocognitive Assessments

Cognitive ability was measured using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Revised Version (WISC-R) (Wechsler, 1974). The WISC-R is an individually administered test of intelligence that generates a Full-Scale IQ score and scores in the domains of verbal comprehension, visual spatial abilities, fluid reasoning, working memory, and processing speed. Higher scores reflect better cognitive abilities.

Statistical Analysis

Children were stratified based on the presence or absence of parental ADHD. We compared baseline demographics and clinical characteristics using linear regression models for continuous data, logistic or exact logistic regression models for binary data, ordered logistic regression models for ordinal data, and truncated Poisson regression models for count data. For the truncated Poisson regression models, we used a lower limit of 0 and an upper limit of 7 for the number of psychiatric disorders, a lower limit of 32 and an upper limit of 81 for FES Conflict, a lower limit of 15 and an upper limit of 73 for FES Expression, and a lower limit of 1 and an upper limit of 69 for FES Cohesion. We also examined the moderating effects of age, sex, and study source individually by adding interaction terms (parental ADHD group-by-age, parental ADHD group-by-sex, and parental ADHD group-by-study source) to our models. All analyses controlled for socioeconomic status and were performed using regression models with robust standard errors to account for the non-independence of siblings. All tests were two-tailed and performed at the .05 alpha-level using Stata (Version 16) (StataCorp, 2019).

Results

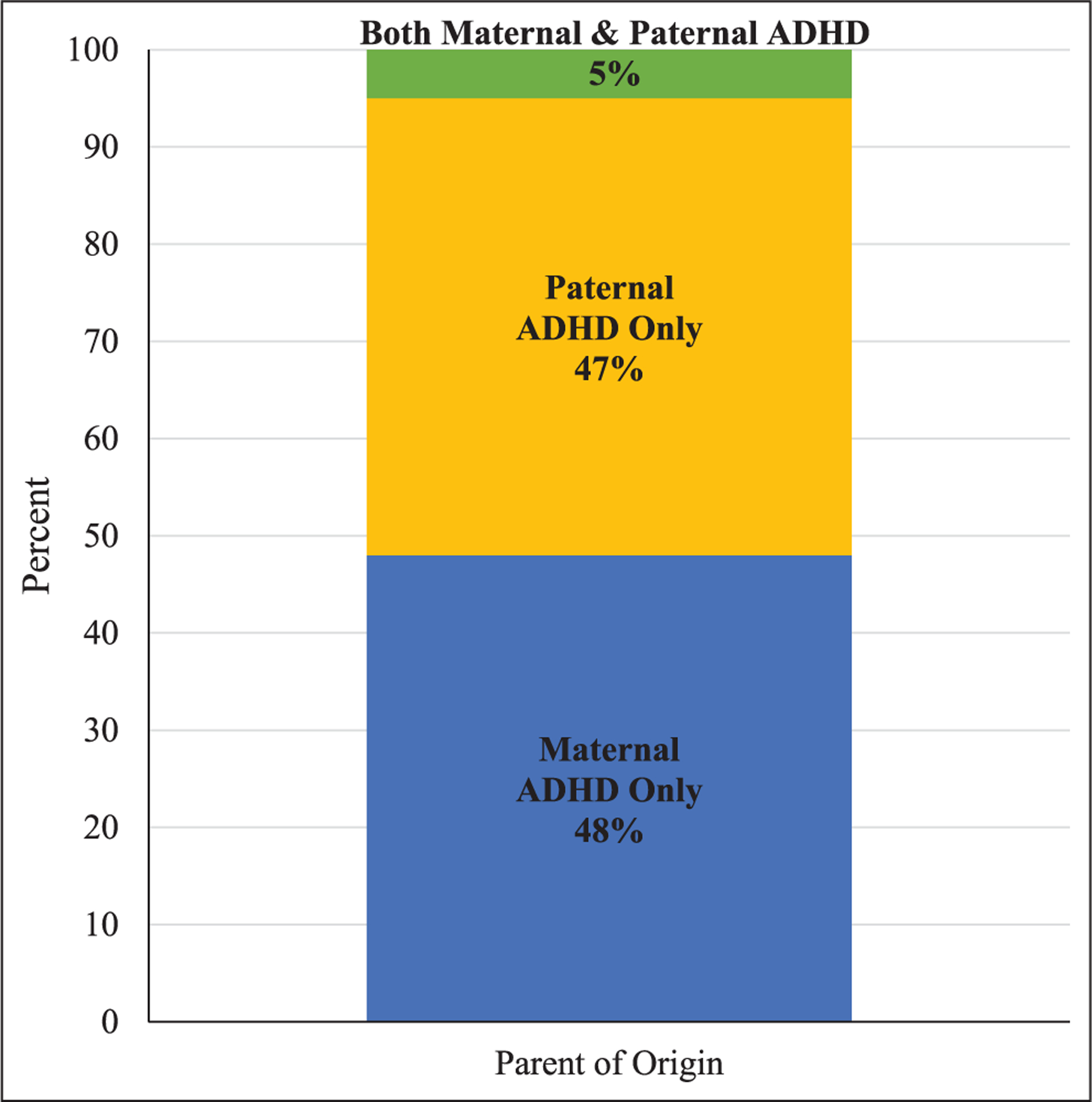

Of the 1,512 offspring available (Figure 1), 230 were excluded because they were outside the 4 to 17 year age range, 515 were excluded because they were ADHD or control probands from the ADHD studies, 48 were excluded because they were missing information about parental ADHD, MDD, or anxiety disorders, 250 were excluded because neither parent had ADHD but at least one parent had MDD or anxiety disorders, and 159 were excluded because they did not have CBCL data. Thus, our final sample consisted of 105 children from 74 families with at least one parent with ADHD and 205 children from 155 families with neither parent having ADHD, MDD, and anxiety disorders. As shown in Figure 2, of the 105 children with at least one parent with ADHD, 51 (48%) had maternal ADHD only, 49 (47%) had paternal ADHD only, and 5 (5%) had both maternal and paternal ADHD.

Figure 2.

Parent of origin for parental ADHD.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant difference in socioeconomic status (SES) between children with and without parental ADHD. Children with parental ADHD were of significantly lower SES compared to children without parental ADHD. Thus, all subsequent analyses controlled for SES. There were no significant differences in age, sex, race, or family intactness between the groups.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Children 4 to 17 Years of Age Stratified by Parental ADHD.

| Children without parental ADHD N = 205 | Children with parental ADHD N = 105 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p-Value | |

| Age | 10.3 ± 3.3 | 10.0 ± 3.2 | .54 |

| Socioeconomic status | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | .003 |

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Male | 112 (55) | 59 (56) | .79 |

| Race | .20 | ||

| Caucasian | 177 (86) | 93 (89) | |

| Not Caucasian | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 22 (11) | 12 (11) | |

| Family intactness | 194 (95) | 93 (89) | .79 |

Parental Diagnoses

Among children with parental ADHD, 13% (n = 14) also had parental bipolar disorder, 72% (n = 76) had parental MDD, and 66% (n = 69) had parental anxiety disorders. By design, none of the children without parental ADHD had parental MDD or anxiety disorders. However, a significantly greater proportion of children with parental ADHD also had parental CD/ASPD compared to children without parental ADHD (35% vs. 11%, p = .003). There was no difference between the two groups in the proportion with parental SUDs which were high in both groups (67% vs. 53%, p = .24).

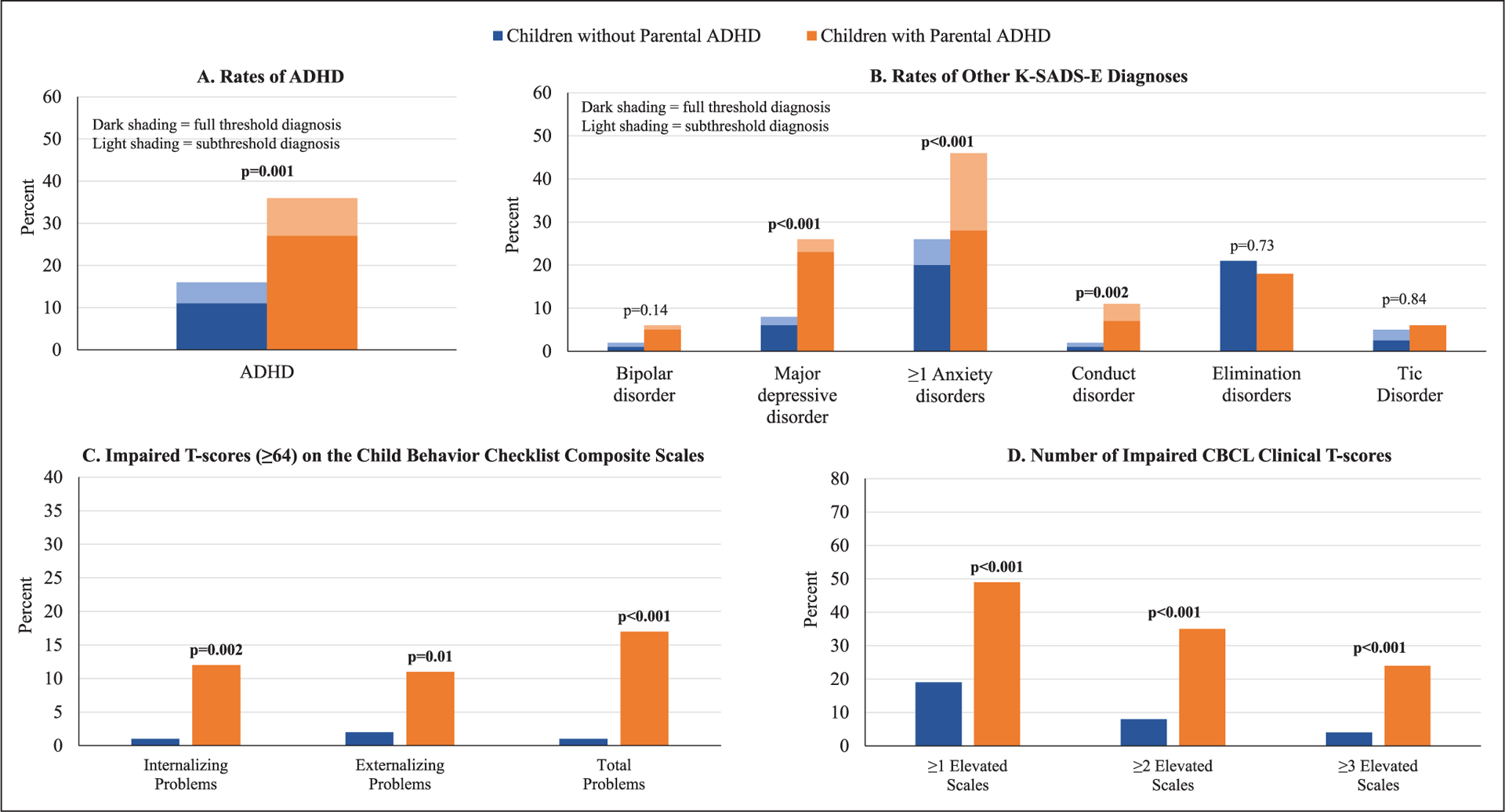

Child Diagnoses

Children with parental ADHD had significantly more full or subthreshold psychiatric disorders (including ADHD) compared to children without parental ADHD (1.5 ± 1.3 vs. 0.8 ± 0.9, p < .001). A significantly greater percentage of children with parental ADHD had full or subthreshold ADHD compared to children without parental ADHD (Figure 3a) and significantly higher rates of full or subthreshold MDD, anxiety disorders, and conduct disorder (Figure 3b). There was no significant difference between the two groups in rate of BP disorder, elimination disorders, or tic disorder.

Figure 3.

Psychopathology: (a) rates of ADHD, (b) rates of other K-SADS-E diagnoses, (c) impaired T-scores (≥64) on the child behavior checklist composite scales, and (d) number of impaired CBCL clinical T-scores.

Child Behavior Checklist Clinical and Composite Scales Findings

Compared to children without parental ADHD, children with parental ADHD had significantly higher proportions of impairment on all CBCL composite scales (T-scores ≥ 64) (Figure 3c) as well as a significantly more impairment on the individual CBCL clinical scales (Figure 3d).

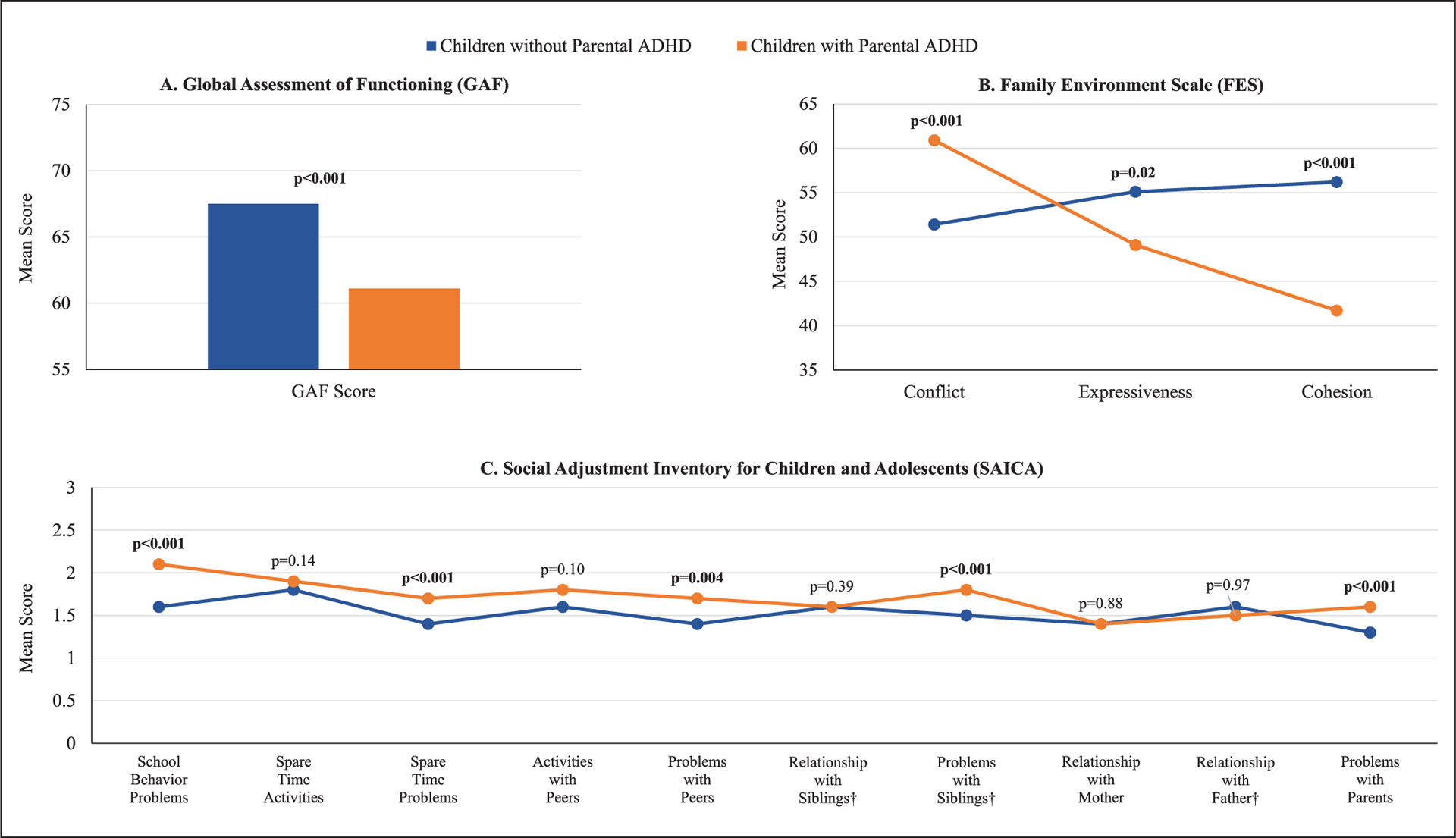

Social Functioning

Compared to children without parental ADHD, children with parental ADHD had significantly worse overall functioning, as assessed by the clinician-rated GAF (Figure 4a), significantly more family conflict and less expressiveness and cohesion, as assessed through the FES (Figure 4b), and significantly more impaired scores on five of the ten SAICA scales, all of which related to problems with school, peers, or family (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Social functioning: (a) global assessment of functioning (GAF), (b) family environment scale (FES), and (c) social adjustment inventory for children and adolescents (SAICA).

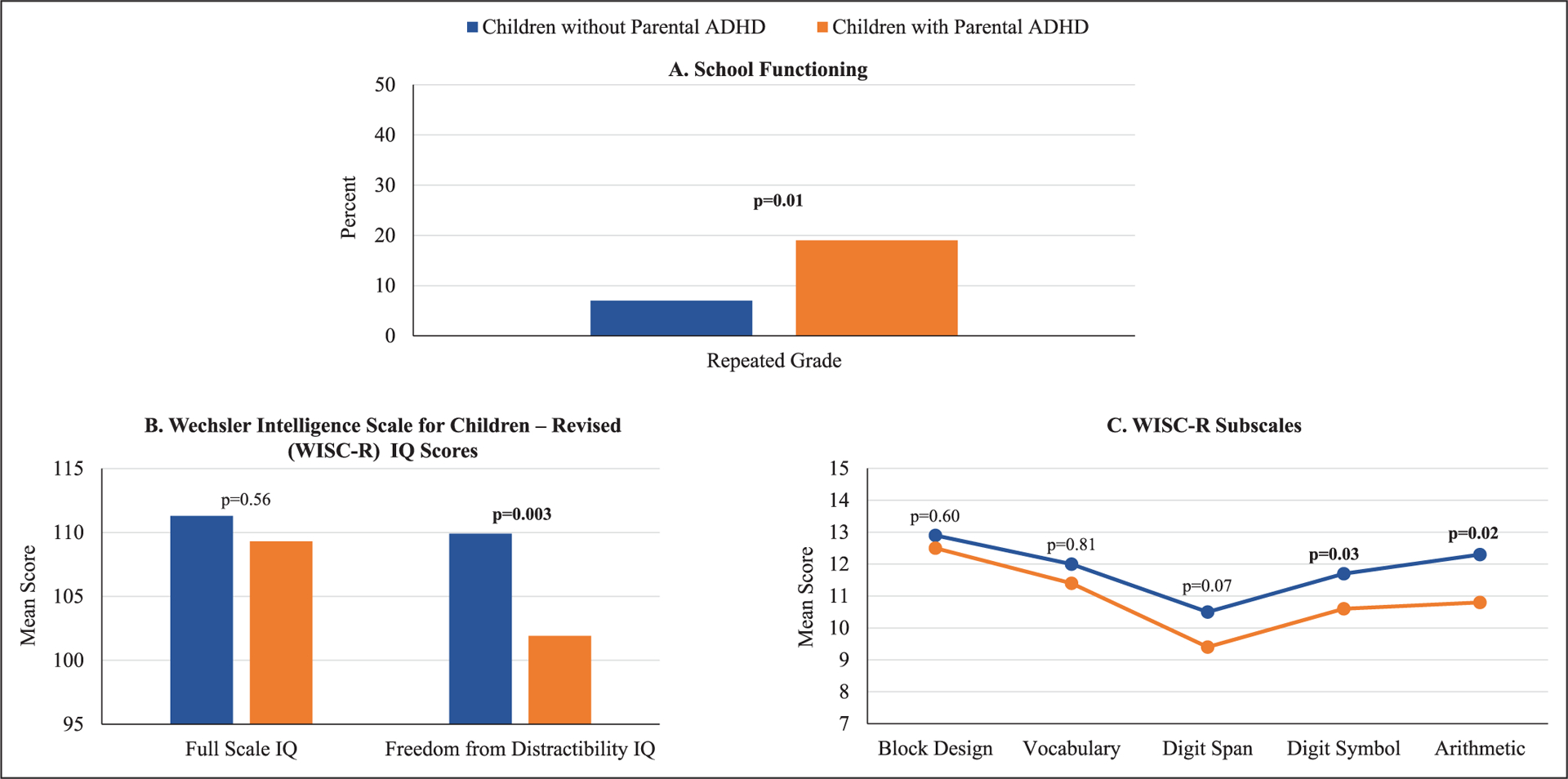

School and Neurocognitive Functioning

A significantly greater proportion of children with parental ADHD repeated a grade in school compared to children without parental ADHD (Figure 5a). As shown in Figure 5b, children with parental ADHD had significantly lower Freedom from Distractibility IQ scores compared to children without parental ADHD. They also had significantly lower Digit Symbol and Arithmetic scores as measured by the WISC-R (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

School and neurocognitive functioning: (a) school functioning, (b) Wechsler intelligence scale for children-revised (WISC-R) IQ scores, and (c) WISC-R subscales.

Analyses Controlling for the Number of Parental Comorbidities

The following measures lost significance when we controlled for the number of parental comorbidities: the CBCL Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems scales; the FES Expressiveness and Cohesion scales; the SAICA Problems with Peers and Problems with Siblings domains; ≥1 anxiety disorder based on the K-SADS-E; repeating a grade in school; and the WISC-R Freedom from Distractibility IQ, Digit Symbol, and Arithmetic measures. The WISC-R Block Design measure was the only outcome to gain significance after controlling for the number of parental comorbidities (p = .03).

Examining the Moderating Effects of Age, Sex, and Study Source

Results remained the same when we examined the moderating effects of age, sex, and study source.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to assess the risk for ADHD in children of parents with ADHD. Findings reveal that a significantly higher number of offspring of parents with ADHD had full and subthreshold ADHD than children of parents without ADHD. Offspring of parents with ADHD also had significantly higher levels of disruptive behavior disorders (ODD and CD), mood disorders (unipolar and bipolar), and anxiety disorders. Furthermore, children of parents with ADHD also had more educational and social problems than children of parents without ADHD. These findings suggest that offspring of parents with ADHD are at significant risk for ADHD and the presence of parental ADHD heralded associated psychiatric, cognitive and educational impairments, well-known correlates of ADHD. These findings extend the very limited literature on the subject providing further evidence that offspring of parents with ADHD are at high risk to develop ADHD and ADHD-associated correlates. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest high-risk study of offspring of parents with ADHD.

Our results show that children with parental ADHD were at higher risk for disruptive, mood and anxiety disorders, as well as social and academic deficits, than children without parental ADHD. Considering that these are well documented correlates of ADHD (Faraone et al., 2015), these findings suggest that these children were in fact affected with ADHD vera.

The finding that 36% of children of parents with ADHD had full or subsyndromal ADHD themselves is consistent with the small literature on high-risk offspring of parents with ADHD (Uchida et al., 2020), that documented that on average 40% of high-risk children of parents with ADHD develop ADHD. However, it is noteworthy that more than 60% of children at risk for ADHD do not develop ADHD, suggesting that the gentic risk for ADHD affects only a minority of children at risk.

While further work is needed to gain insights on the moderators of the risk for ADHD in high-risk offspring of parents with ADHD, this research can aid in identifying early manifestations of ADHD in young children at risk and in the development of preventive and early intervention strategies for children at risk for ADHD.

Our findings need to be viewed in light of some methodological limitations. While our study included a large sample of children at risk for ADHD, the original sample was asceratined from a case control family study of probands with and without ADHD and a study of children at risk for panic/agoraphobia and depression. Because the sample was largely Caucasian, our findings may not generalize to other ethnic groups.

Despite these limitations, our study shows that offspring of parents with ADHD are at a significant risk of manifesting full or subsyndromal forms of ADHD and associated psychiatric, cognitive, social, and educational impairments worthy of further clinical and scientific efforts.

Key Points and Relevance.

Previous research suggests ADHD is a heritable disorder.

We found that offspring of ADHD parents had significantly more ADHD and associated psychiatric disorders, as well as functional impairments, than offspring of healthy parents.

Children of parents with ADHD could benefit from close observations for signs of ADHD and associated symptoms.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Biographies

Mai Uchida, MD, is Director of the Child Depression Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the Harvard Medical School. Dr. Uchida is a Board Certified Child, Adolescent, and Adult Psychiatrist.

Maura DiSalvo, MPH, is the biostatistician for the Clinical and Research Programs in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD at the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Alan and Lorraine Bressler Clinical and Research Program for Autism Spectrum Disorders at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Daniel Walsh, BA, is a research assistant in the Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD. He has a bachelor’s degree from Colorado College and provides research support to the principal investigators in the department.

Joseph Biederman, MD, is Chief of the Clinical and Research Programs in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD at Massachusetts General Hospital, Director of the Alan and Lorraine Bressler Clinical and Research Program for Autism Spectrum Disorders at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and Professor of Psychiatry at the Harvard Medical School.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and the 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Benjamin J, Krifcher B, Moore C, Sprich-Buckminster S, Ugaglia K, Jellinek MS, Steingard R, Spencer T, Norman D, Kolodny R, Kraus I, Perrin J, Keller MB, & Tsuang MT (1992). Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(9), 728–738. 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090056010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Williamson S, Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Weber W, Jetton J, Kraus I, Pert J, & Zallen B (1999). Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: Findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(8), 966–975. 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty C, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Henin A, Faraone SV, Dang D, Jakubowski A, & Rosenbaum JF (2006). A controlled longitudinal 5-year follow-up study of children at high and low risk for panic disorder and major depression. Psychological medicine, 36(8), 1141–1152. 10.1017/S0033291706007781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Rohde LA, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Tannock R, & Franke B (2015). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 1, 15020. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, & Sklar P (2005). Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry, 57(11), 1313–1323. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpin V, Mazzone L, Raynaud JP, Kahle J, & Hodgkins P (2016). Long-term outcomes of ADHD: A systematic review of self-esteem and social function. Journal of attention disorders, 20(4), 295–305. 10.1177/1087054713486516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco JA, Henin A, Petty C, Faraone SV, Mazursky H, Bruett L, Rosenbaum JF, & Biederman J (2012). Psychopathology in adolescent offspring of parents with panic disorder, major depression, or both: A 10-year follow-up. The American journal of psychiatry, 169(11), 1175–1184. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four factor index of social status. Yale Press. [Google Scholar]

- John K, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA, & Warner V (1987). The social adjustment inventory for children and adolescents (SAICA): Testing of a new semistructured interview. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(6), 898–911. 10.1097/00004583-198726060-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe IM, & Feldman HM (2007). Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Journal of pediatric psychology, 32(6), 643–654. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May F, Ford T, Janssens A, Newlove-Delgado T, Emma Russell A, Salim J, Ukoumunne OC, & Hayes R (2021). Attainment, attendance, and school difficulties in UK primary schoolchildren with probable ADHD. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 442–462. 10.1111/bjep.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (1990). Conceptual and empirical approaches to developing family-based assessment procedures: Resolving the case of the family environment scale. Family Process, 29(2), 199–208; discussion 209–111. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1990.00199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, & Moos BS (1994). Family environment scale manul. (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, & Puig-Antich J (1987). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children: Epidemiologic version. Nova University. [Google Scholar]

- Piersma HL, & Boes JL (1997). The GAF and psychiatric outcome: A descriptive report. Community Mental Health Journal, 33(1), 35–41. 10.1023/a:1022413110345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Kagan J, Snidman N, Friedman D, Nineberg A, Gallery DJ, & Faraone SV (2000). A controlled study of behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(12), 2002–2010. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K, Prasad V, Daley D, Ford T, & Coghill D (2018). ADHD in children and young people: Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(2), 175–186. 10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30167-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, & First MB (1990). Structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R: Non-patient edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata statistical software: Release 16. Statacorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Tistarelli N, Fagnani C, Troianiello M, Stazi MA, & Adriani W (2020). The nature and nurture of ADHD and its comorbidities: A narrative review on twin studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 109, 63–77. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida M, Driscoll H, DiSalvo M, Rajalakshmim A, Maiello M, Spera V, & Biederman J (2021). Assessing the magnitude of risk for ADHD in offspring of parents with ADHD: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(13),1943–1948. 10.1177/1087054720950815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderDrift LE, Antshel KM, & Olszewski AK (2019). Inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity: Their detrimental effect on romantic relationship maintenance. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(9), 985–994. 10.1177/1087054717707043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1974). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised UK version. The Psychological Corporation Ltd. [Google Scholar]