Abstract

Duchene muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked neuromuscular disorder that affects about one in every 5000 live male births. DMD is caused by mutations in the gene that codes for dystrophin, which is required for muscle membrane stabilization. The loss of functional dystrophin causes muscle degradation that leads to weakness, loss of ambulation, cardiac and respiratory complications, and eventually, premature death. Therapies to treat DMD have advanced in the past decade, with treatments in clinical trials and four exon-skipping drugs receiving conditional Food and Drug Administration approval. However, to date, no treatment has provided long-term correction. Gene editing has emerged as a promising approach to treating DMD. There is a wide range of tools, including meganucleases, zinc finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases, and, most notably, RNA-guided enzymes from the bacterial adaptive immune system clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR). Although challenges in using CRISPR for gene therapy in humans still abound, including safety and efficiency of delivery, the future for CRISPR gene editing for DMD is promising. This review will summarize the progress in CRISPR gene editing for DMD including key summaries of current approaches, delivery methodologies, and the challenges that gene editing still faces as well as prospective solutions.

I. INTRODUCTION

Duchene muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most commonly heritable lethal neuromuscular disorder, with a global prevalence of about one in 5000 live male births.1–3 DMD is inherited as a recessive X-linked disorder due to loss of function mutations in the DMD gene encoding dystrophin, which is the largest human gene spanning 2.3Mb with 79 exons on chromosome Xp21.2. As a component of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC), dystrophin is a key protein for stabilizing the muscle membrane through connecting and mediating signaling between the cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix. In DMD, the preliminary symptoms characteristic of early muscle degradation emerge after the first years of life between the ages of 3–5 years with frequent falls, slow running, and a waddling gait.4,5 The patient then exhibits progressive muscle weakness, loss of independent ambulation, and cardiac or respiratory complications, which leads to premature death in their late teens or early twenties.4–6 With the improvement in cardiorespiratory management and early corticosteroid administration, survival rates have been extended to the late 20s.7,8 A related disease, Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), has mutations that typically preserve the open reading frame (ORF) of dystrophin. As a result, BMD patients produce a truncated but partially functional dystrophin protein, which can cause a milder muscle disorder, later onset, and longer survival.4,5

Over the past two decades, therapies for DMD have advanced from preclinical models to clinical trials with four drugs receiving conditional regulatory approval. Strategies to restore dystrophin include exon skipping, premature translational termination reading-through, and gene replacement. Exon-skipping approaches for DMD therapeutics are inspired by the finding that mutations preserving the reading frame result in milder BMD phenotypes. The aim is to restore the dystrophin reading frame by using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to manipulate pre-mRNA splicing to skip exons that restore the ORF. This approach may address as many as 83% of DMD patients with designed anti-sense oligonucleotide (ASOs) specific for target exons including exon 51 (13% of patients), exon 45 (8.1%), and exon 53 (7.7%).9 Four exon skipping-mediated drugs, casimersen (exon 45), eteplirsen (exon 51), golodirsen (exon 53), and viltolarsen (exon 53), have achieved dystrophin restoration in a small patient population.10–13 Although the restoration of induced dystrophin expression is still considerably low in the studies, those four drugs received conditional approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).14 Further studies to confirm and evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of exon skipping mediated therapies are currently ongoing (NCT03532542, NCT03985878, NCT03992430, NCT04060199, NCT04179409, NCT04768062, and NCT04956289). Although all approved medicines had promising results,15,16 there is still no definitive curative treatment approved for DMD. In addition to ASOs designed for exon skipping, because 15% of DMD cases are caused by a nonsense mutation that results in a premature stop codon, a small molecule therapy was developed to mask the premature stop.9,17 Ataluren (PTC124) is a small molecule that targets ribosomal machinery to promote the readthrough of premature stop codons so dystrophin can be translated into a functional protein.18 Although clinical trials for ataluren do not meet the primary end point, a delayed disease progression compared with placebo was demonstrated and had been granted approval in Europe.19,20 Importantly, read-through compounds and exon-skipping oligonucleotides are not permanent and require repeated administration.

Gene-replacement therapy has emerged as a promising approach to replace the dysfunction endogenous dystrophin. This effort aims to adapt adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a muscle-targeted carrier to deliver a replacement dystrophin gene. Dystrophin replacement is challenging due to the large size of full-length dystrophin cDNA (∼14kb) and the packaging limitation of AAV (∼4.7 kb). However, the development of mini- and microdystrophin, a functional but shortened version of dystrophin, aims to resolve the gene size problem, which can then be accommodated by AAV. Currently, there are several ongoing clinical trials that are investigating the safety and tolerability of this approach (NCT03368742, NCT03375164, NCT03362502, NCT03769116, and NCT05096221). One-year evaluation of systemic AAV-microdystrophin gene transfer (NCT03375164) indicates that this therapy was well tolerated, had minimal adverse events, and demonstrated functional improvement compared to the standard of care.21 Interim data from NCT03368742 showed meaningful clinical improvement and no safety issues in six patients. While these trials shed a promising light on a new therapy in DMD, there are many unknowns on the long-term efficacy of this approach.

Rapid advances in genome-editing technology have enabled a new era in gene therapy and accelerated the research toward a cure for DMD to correct the underlying pathology. Engineered DNA-cleaving enzymes, such as meganucleases (MGNs), zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR-Cas), have demonstrated the potential to restore the reading frame of mutated DMD.22–24 Among all the tools available for genome editing, CRISPR-mediated therapeutics have revolutionized the field, offering a simpler, more flexible, and efficient method of altering the genome.25,26 Despite many breakthroughs, delivering CRISPR components safely and efficiently for DMD therapeutic approaches remain a significant hurdle. This review summarizes the progress of CRISPR-Cas9 applications in DMD gene editing, the details of delivery methods used in CRISPR-DMD editing, and the challenges in delivering CRISPR-Cas9. This review further analyzes the currently available solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery for developing an efficient and low immunogenic delivery cargo for CRISPR-DMD therapeutics.

II. GENE EDITING FOR DUCHENNE MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY

Based on the structure, there are four main groups of DNA-editing nucleases: MGN, ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR. These genome editing toolboxes can be engineered to recognize and induce double-strand breaks (DSB) at target DNA sequences genome. These breaks are repaired by either the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway or the more precise homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway in the presence of a donor template. These nucleases have been adapted to correct DMD patient mutations in vitro with promising results. In the past decade, due to the simplicity and versatility of CRISPR, the genetic engineering field has rapidly expanded with new methods for gene correction in vitro and in vivo (Table I). Below, we highlight the methods for DMD editing with protein endonucleases and RNA-guided nucleases (CRISPR).

TABLE I.

Summary of in vitro and in vivo CRISPR-based preclinical work for DMD and their prominent findings. N/A: not tested.

| CRISPR in vitro experiment in DMD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Cas enzyme type | DMD target therapy | Method | Immune response | Off-target activity/mutagenesis | Notable finding | Reference | |

| Injection | mdx zygote | SpCas9 mRNA | Exon 23 | HDR-mediated exon correction | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in skeletal and heart muscle in corrected progeny mice. | 61 |

| Cas12a mRNA | Exon 23 | Exon frameshifting, HDR-mediated correction | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in skeletal muscle, heart muscle, and brain in corrected progeny mice. | 201 | ||

| Electroporation | DMD patient-derived iPSCs myoblast | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 44 and 45 | Splice site mutation, Exon frameshifting Exon insertion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored using all methods. | 23 |

| SaCas9 plasmid | IMTR of UTRN 3′ UTR | Transcriptional modulation | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Upregulation of utrophin at up-to twofold and restoration of DGC expression. | 82 | ||

| DMD patient-derived myoblast | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 45–55 | Exon deletion | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored using multi-exon deletion in treated cells and in myofiber after in vivo transplantation in immunodeficient mice. | 57 | |

| dCas9-VP160 plasmid | UTRN A or B promoter | Transcriptional modulation | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Upregulation of utrophin at up to three and sevenfold for UTRN A and B, respectively. | 80 | ||

| Nucleofection | DMD patient-derived iPSCs myoblast | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 45–55 | Exon deletion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in reframed exon | 58 |

| DMD patient-derived fibroblast | SpCas9 protein | Exon 44 | Exon frameshifting | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in myotubes from fibroblast trans-differentiation. | 261 | |

| DMD patient-derived iPSCs cardiomyocytes | nCas9 ABE, PE plasmid | Exon 52 | Splice site mutation, Exon frameshifting | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in cardiomyocytes after base editing and prime editing. PE edited cells can normalize contractile abnormality. | 73 | |

| LNP | DMD patient-derived myoblast | SpCas9 | Exon 50, Exon 54 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | Dystrophin expression is restored in corrected myotubes | 55 |

| mdx muscle-derived fibroblast | SpCas9 | Exon 23 | HDR-mediated exon correction | N/A | N/A | HDR correction of DMD mutations was performed on 1% of all cells using ssODN | 137 | |

| DMD patient-derived iPSCs cardiomyocytes | SaCas9-TAM plasmid | Exon 50 | Splice site mutation | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in cardiomyocytes with 95% of the reads acquired the intended mutation. | 74 | |

| GNP | mdx primary muscle cells | SpCas9 protein | Exon 23 | HDR-mediated exon correction | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in corrected myotubes. | 165 |

| VLP | DMD patient-derived iPSCs myoblast | SpCas9 protein | Exon 45 | Splice site mutation | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored in treated cells. | 175 |

| AdV | DMD patient-derived myoblast | SpCas9 protein | Exon 48–50, Exon 45–52 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | Dystrophin expression is restored in corrected myoblast. | 56 |

| Primary human myoblast | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 51 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | Exon deletion is detected in dystrophin gene. | 54 | |

| DMD patient-derived myoblast | eSpCas9 plasmid | Exon 48–50 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | Dystrophin expression is restored in targeted removal of mutational hotspots. | 133 | |

| DMD patient-derived myoblast | eSpCas9 plasmid | Exon 51, Exon 53 | Exon frameshifting | N/A | Additional NLS might reduce off-target activities | Dystrophin expression is restored in corrected myotubes. | 262 | |

| LV | DMD patient-derived myoblast | SpCas9 plasmid | Intron 2 | Duplicated exon deletion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | Dystrophin expression is restored about 7%–11% in western blot (WB) analysis. | 59 |

| CRISPR in vivo experiment in DMD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Cas enzyme type | DMD target therapy | Method | Immune/toxicity response | Off-target activity/mutagenesis | Length of study | Systemic/local | Notable finding | Reference | |

| Electro-poration | mdx mice | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 50, Exon 54 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | 7 days | Local | A large deletion of mutated exon in DMD gene (160 kb) leading to restoration of reading frame in skeletal muscle is achieved. | 55 |

| LNP | hEx45KI-mdx44 | SpCas9 mRNA | Exon 44 | Exon deletion | Repeated IM administration did not elicit immune response and showed no toxicity signs | No off-target mutations detected | 14 days to 12 months | Local | Dystrophin expression in skeletal muscle is stable for a year and repeated injections result in cumulative benefits. | 154 |

| ΔE × 44 mice | SpCas9 protein | Exon 44 | Exon deletion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 6 weeks | Local | Dystrophin expression in skeletal muscle is restored about 4.2% in WB analysis. | 155 | |

| Golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) | SpCas9 plasmid | Intron 6, Exon 7 | Exon insertion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 3 months | Local | Dystrophin expression in skeletal muscle is minimally restored in HDR-mediated treatment. | 156 | |

| GNP | mdx mice | SpCas9 protein | Exon 23 | HDR-mediated exon correction | No elevation in plasma cytokine is detected up to two weeks post-injection and after multiple injections | Minimal off-target mutations detected | 2 weeks | Local | An improvement in skeletal muscle function is seen with 5.4% restoration of dystrophin expression in WB analysis | 165 |

| VLP | ΔE × 52 mice | SpCas9 protein | Exon 53 | Exon frameshifting | N/A | N/A | 1 week | Local | Dystrophin restoration is confirmed by IF. | 174 |

| AAV9 | ΔE × 50 dog | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 51 | Exon frameshifting | N/A (while high dose immune suppression was administered) | No off-target mutations detected | 3 weeks | Local | Dystrophin restoration up to 90% in immunohistochemical staining (IHC) is detected in skeletal and heart muscles. | 263 |

| mdx mice | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 23 | Exon deletion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 3–12 weeks | Local and systemic | Dystrophin expression in skeletal and heart muscle is restored within range of 5%–25% based on IHC. | 45 | |

| Exon frameshifting | N/A | Minimal change in off-target mutations detected after 18 months of treatment. | 18 months | Systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored 20% in heart and 2% in skeletal muscle based on WB. | 264 | ||||

| SpCas9, SaCas9 plasmid | Exon 23 | Exon deletion | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | 4 weeks | Local and systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored six in skeletal muscle and 1% in heart muscle after systemic treatment based on WB. | 47 | ||

| CjCas9 plasmid | Exon 23 | Exon frameshifting | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 8 weeks | Local | Dystrophin restoration up to 40% based on IHC and improvement in muscle function are observed. | 265 | ||

| SaCas9 plasmid | Exon 23 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | 6 weeks | Local and systemic | AAV can transduce satellite cells population with a lesser degree of gene editing. | 116 | ||

| ΔE × 20 mice | nCas9-ABE plasmid | Exon 20 | Base editor-mediated correction | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 8 weeks | Local | Dystrophin expression is restored 17% in skeletal muscle based on IF. | 75 | |

| Dup 18–30 mice | SaCas9 plasmid | Exon 18–30 | Duplicated exon removal | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 7 weeks | Systemic | Dystrophin restoration ranging from 12% to 68% in skeletal muscle and 22%–36% in heart based on IF. | 266 | |

| Patient derived xenograft DMD mouse | Cas9, Cas12a plasmids | Exon 46–54 | Exon deletion | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected in both Cas proteins. Cas12a have fewer off-target sites with similar efficiency | 30 days | Local | Dystrophin expression is restored more than 10% in skeletal muscle based on IF in both Cas9 and Cas12. | 200 | |

| ΔE × 44 mice | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 42–46 | Exon deletion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 4 weeks | Local, Systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored more than 90% in skeletal heart muscle based on IF with muscle improvement. | 267 | |

| Exon 45 | Splice site mutation, Exon frameshifting | N/A | N/A | 4 weeks | Systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored ranging from 50% to 70% in skeletal and heart muscle based on WB. | 268 | |||

| Exon 45 | Exon frameshifting | Upregulation of genes related to immune system are detected in treated mice. | Minimal change in off-target mutations detected after 18 months of treatment. No off-target and minimal on-target AAV integration are observed. | 18 months | Systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored more than 40% in skeletal muscle based on WB | 269 | |||

| ΔE × 50 mice | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 51 | Splice site mutation | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 4–8 weeks | Local, systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored up to 90% in skeletal muscle and heart based on IHC with improvement in muscle function. | 63 | |

| SaCas9 plasmid | Exon 51 | Exon frameshifting | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 4 weeks | Systemic | Dystrophin expression is restored up to 40% in skeletal and heart muscle based on WB with muscle function improvement. | 270 | ||

| ΔE × 52 mice | SaCas9 plasmid | Exon 47, Exon 58 | Exon deletion | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 6 weeks | Systemic | Dystrophin expression is confirmed in heart based on WB. | 128 | |

| Exon 52, Exon 52–79 | Exon insertion | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | 8 weeks | Local, systemic | Full-length dystrophin expression is observed by WB. | 178 | |||

| ΔE × 43 mice, ΔE × 45 mice, ΔE × 52 mice | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 53, Exon 44 | Exon deletion, Exon frameshifting | N/A | No off-target mutations detected | 3 weeks | Local | Dystrophin expression is restored ranging from 14% to 50% based on WB in all type of mice. | 271 | |

| ΔE × 52 pig | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 51 | Exon deletion | N/A | No off-target effects are detected at systemic dose | 6 weeks | Local, systemic | Dystrophin expression and function are restored in skeletal muscle. Survival rate and cardiac improvement are observed after treatment. | 272 | |

| AAV8 | mdx mice | SaCas9 plasmid | Exon 23 | Exon deletion | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | 8 weeks | Local | Dystrophin expression is restored up to 8% based on WB with muscle function improvement. | 46 |

| Immune responses against SaCas9 nuclease are detected in adult but not in newborn dystrophic mice | Minimal change in off-target mutations after 1 year treatment. Unintended vector integrations are detected in target sites. | 12 months | Local, systemic | A decrease in dystrophin staining after local administration and an increase after systemic treatment. | 194 | |||||

| AAV6 | mdx4cv mice | SpCas9, SaCas9 plasmids | Exon 52–53 | HDR-mediated correction | N/A | Minimal off-target mutations detected | 4 weeks | Local | Dystrophin expression is restored up to 23% in skeletal muscle based on WB. | 62 |

| AdV | mdx mice | SpCas9 plasmid | Exon 21–23 | Exon deletion | N/A | N/A | 3 weeks | Local | Dystrophin expression is restored up to 50% in skeletal muscle based on WB. | 136 |

| Exon 23 | HDR-mediate exon correction | N/A | N/A | 4 weeks | Local | Up to 8% dystrophin restoration in skeletal muscle after transplantation of corrected muscle stem cells. | 137 | |||

A. Protein endonucleases

Meganucleases (MGNs) are homing endonucleases that have five families based on sequence and peptide motif similarities. The largest and most engineered MGN is the LAGLIDADG family that can recognize a large DNA target site (12–45 bp).27,28 As a proof-of-principle for DMD, the I-SceI and RAG1 MGN were reported to efficiently restore the expression of dog microdystrophin containing frameshift mutation in human myoblast in vitro and Rag/mdx mouse muscle fibers in vivo with local injections.22 MGN has also demonstrated the capability to target various introns and exons in the human dystrophin gene.29,30 However, the complexity of re-engineering MGNs, due to DNA recognition and endonuclease activity being located in the same protein motif, limits its application.27

ZFNs are endonucleases engineered for gene-editing and created by fusing the zinc-finger DNA-binding domain to the FokI endonuclease DNA-cleavage domain.31 The DNA-binding domain consists of up to six zinc finger protein domains, each of which recognizes the DNA targets with 3 bps, and can target a sequence of up to 18 bps.32 ZFNs have been used to restore the reading frame of human dystrophin expression by targeting exon 50 and a splice site in exon 51.24,30 The limited ability of DNA-binding domains to target any desired sequence and the difficulty and high cost of designing ZFNs have become major challenges and drawbacks of genome engineering with ZFNs.

TALEs are naturally found in Xanthomonas spp. proteobacteria and encode a DNA-binding domain with 33–35 amino acid repeat monomers that each recognize one target base. Similar to ZFNs, TALENs are created by fusing DNA-binding domains and the FokI endonuclease catalytic domain. TALE repeats can be linked together to target the desired sequence.26,33 The successful introduction of small deletions, with no off-target mutagenesis, in exons 45 and 51 resulted in a frameshift of the DMD reading frame and restored dystrophin expression in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells and myoblasts, respectively.23,34 Although the TALEN system is easier to design than ZFNs and versatile enough to target almost any DNA region, the construction of TALENs is laborious, challenging, and time-consuming, and the large, highly repetitive construct makes delivery a significant challenge.

B. RNA-guided endonucleases: CRISPR

The discovery of CRISPR was heralded by reports of mysterious repetitive sequences consisting of short regions of unique DNA sequences called spacers separated by short palindromic repeats in the genome of certain bacteria species.35,36 The discovery that the spacer sequences share homology with phage DNA conferring resistance to phage infection identified CRISPR as a bacterial adaptive immune system.37–40 This system captures foreign DNA sequences and encodes the sequences as a recorded spacer in the host's DNA to recruit CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins to destroy the associated pathogen in future invasions. In 2012, the CRISPR system was reprogrammed for RNA-guided DNA targeting, a powerful tool for genome editing.41 The system has since been adapted for use in mammalian cells,42–44 in animal models of disease,45–47 and now in clinical trials48 (NCT04774536 and NCT03872479).

The key features of the CRISPR-Cas9 system are the guide RNA, Cas9 protein, and the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). In the native bacterial system, short spacer sequences are integrated into the CRISPR locus and transcribed into CRISPR RNA (crRNA). These crRNAs anneal to trans-activating crRNAs (tracrRNAs) which are transcribed upstream of the CRISPR locus to form an RNA duplex that binds and directs the Cas protein to cleave the matching target DNA (protospacers) containing a suitable PAM. PAM sequences, a DNA marker allowing the differentiation between self-and non-self, vary based on the type of bacteria.49 For gene-editing applications, the spacer navigation system was repurposed into a programmable single guide RNA (sgRNA) by fusing the crRNA and tracrRNA.41 Cas proteins can be divided into two classes: multiprotein complex for cleavage (class I) and single protein for cleavage (class II). As a gene editing platform, class II is the most studied with Cas9 being the most common variant. The exploration of Cas9 variants from the initial Streptococcus pyogenes (Sp) Cas941 to many other organisms including Staphylococcus aureus (Sa), Staphylococcus thermophilus (St), Campylobacter jejuni (Cj), etc.,50–52 and other types of Cas protein, such as Cas12a53 have increased the versatility of the system to target virtually any gene. Diverse approaches have been examined to restore the function and expression of dystrophin using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. 1).

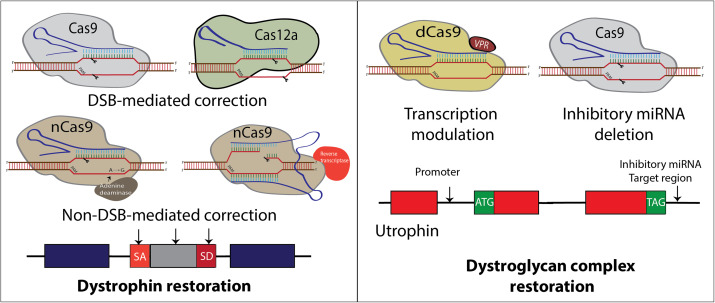

FIG. 1.

Summary of CRISPR-mediated approaches to treat DMD mutations. (a) CRISPR-DMD approaches mainly target dystrophin to precisely correct specific mutation(s) including (1) Cas9 dual DSBs to excise exons restoring reading frame or single DSBs knocking out splice sites, (2) ABE substitutions mutating splice sites, and (3) prime-editing mutating splice sites or deleting and adding integrase recognition sites for future replacement. (b) Alternative approaches target utrophin, an autosomal homolog of dystrophin, to upregulate its expression supplanting dystrophin.

In early in vitro work, the first generation of the CRISPR-Cas9 system effectively restored dystrophin expression via targeted deletion of single to multi exons in both human and mouse myoblasts.23,54–58 Several groups have also successfully applied CRISPR-Cas9 and Cas12 for modifying DMD mutations in vitro with HDR correction and duplication removal approaches.59–61 Early in vivo studies demonstrated the efficacy of CRISPR genome editing to delete mutated DMD exon 23 using AAV vector transduction in mdx mice,45–47 delete exons 52–53 in mdx4c mice,62 and exon 50 in ΔE × 50 mice.63 These approaches rely primary on targeted deletion, removal of splice sites, or frameshifting [Fig. 1(a)]. The completed CRISPR-DMD studies are listed in Table I, which indicate that programmable CRISPR complexes can be used for many different approaches with various delivery modalities to restore dystrophin expression in cells or animal models.

C. CRISPR-based correction of DMD without DSBs

The first demonstration of targeted DSB DNA cleavage using Cas9 variants has progressed beyond the original role of DSB generation to scarless editing. Cas9 has been engineered by mutating one of the nuclease domains, resulting in the generation of Cas9 nickase (Cas9n), which only induces a single-stranded nick.41,42 Mutating both nuclease domains results in a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) that holds no nuclease activity. Cas9n has been fused with deaminases to chemically modify DNA bases for single base editing.64,65 Cytosine base editors (CBE) use Cas9n fused with a cytosine deaminase and an inhibitor of uracil DNA glycosylase (UGI) to convert cytosine (C) to uracil (U) without creating a DSB and preventing base excision repair that changes the U back to C mutation.64 Adenine base editors (ABE) use Cas9n fused with a protein engineered adenine deaminase to convert an A-T base pair to a G–C base pair.65 The extensive optimizations of base editors to reduce packaging size, reduce RNA editing and off-targets, and expand targeting capacity have increased the specificity and efficiency of base editors.66 However, bystander edits due to the large editing window of base editors, specifically adenine base editors, remains an issue.67 In addition to base editors, Cas9n fusion with a Molony-murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase generates a CRISPR-prime editor, which create edits without breaking both strands of DNA.68 Prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs), in addition to the spacer sequence and gRNA scaffold, contain a 3′ extension consisting of a primer binding site (PBS) that hybridizes to the opposite strand of the spacer binding site and a reverse transcriptase template encoding the desired edit.69 Prime editors have been used to encode small deletions or insertions and large deletions and insertions using PRIME-del and PEDAR, respectively.69,70 While prime editing is flexible and reduces off-targets, the efficiency of prime editing in vitro and in vivo is lower compared to base editing and CRISPR-Cas9-produced indels.69,71 Furthermore, the large size of prime editors make it difficult to package.72 In DMD, both adenine base editing and prime editing have been used to target splice donor sites and reframe the dystrophin ORF, respectively, in cardiomyocytes derived from the human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model of DMD.73 The development of a diverse CRISPR toolbox builds an essential bridge to drive major advances in gene therapy for many genetic diseases, especially DMD.

RNA splicing is a critical mechanism to modify protein expression. Base editors have the capability of precise single nucleotide substitution in dystrophin splice sites, which results in skipping the mutated exon and restoring dystrophin expression in cultured cells and mice.23,74,75 dCas9 has the capacity to regulate gene expression. dCas9 can interfere with transcription by occupying the gene physically and has been engineered to behave as transcription activators (CRISPRa) or inhibitors (CRISPRi),76–78 and a versatile tool for modifying the epigenetic landscape.79 In DMD, this strategy is applied by introducing dCas9 fused to transcriptional activator VP160 targeting the utrophin promoter to upregulate utrophin expression [Fig. 1(b)].80 Increased utrophin expression is associated with an improved DMD phenotype.80 This provides an opportunity for mutation-independent approaches for upregulating compensatory genes in muscle disease more broadly.81 Another approach used nuclease active Cas9 to target miRNA sites in the utrophin 3′ untranslated region to upregulate expression.82

D. CRISPR-associated transposases

All CRISPR methods mentioned above are mainly utilized for deletion, sequence modification, or transcription factor alteration; however, integration of large DNA fragments into the genome remains a challenge. While HDR can be used to insert large genes into target loci, it is not effective in post-mitotic cells and consequently is inefficient in skeletal muscle.83 One study compared HDR-mediated correction to deletions in DMD demonstrating that only a small portion of skeletal muscle cells in dystrophic muscles successfully exhibited HDR-mediated correction following CRISPR-Cas9 editing.62 To overcome the inefficiency of the HDR pathway, several integration approaches based on NHEJ or micro-homology-mediated-end-joining (MMEJ) have tried to address these concerns. However, the efficiency in certain cell types including muscle cells and potential off-target insertions still needs improvement.84,85 Recently, transposon-associated CRISPR-Cas9 systems are emerging as a robust approach that combines the RNA-guided DNA targeting function of the CRISPR system and the DNA-insertion mechanism of transposons. Furthermore, this system obviates the need for double-strand breaks in target DNA and host DNA repair, signifying a major advancement in gene-editing technology. Several groups have demonstrated potential tools such as CAST (CRISPR-associated transposase), INTEGRATE (insert transposable elements by guide RNA-assisted targeting), TwinPE (Twin Prime Editor), and PASTE (Programmable Addition via Site-specific Targeting Elements) that could enable potential therapies that require targeted integration.86–89

III. IN VIVO DELIVERY OF CRISPR

Safe and efficient delivery is the biggest barrier to the translation of CRISPR therapies for DMD. Current delivery methods include physical, viral vectors, and non-viral vectors. Viral vectors, including adeno-associated virus (AAV), adenovirus (AdV), and lentivirus, are the most widely used in DMD gene therapy (Fig. 2). AAV delivery is the most studied vehicle in preclinical work because of its natural tropism to muscle tissue, long-term expression, and relatively higher safety profile compared to alternative methods.90,91 While AAV delivery has advanced to clinical trials for microdystrophin replacement, researchers are still maximizing the potential of non-viral vectors to overcome the limitations of viral and physical delivery methods. Viral vectors have been reported to integrate their genome into host chromosomes, which may lead to insertional mutagenesis. In addition, AAV has a small gene encoding capacity. Physical delivery methods, such as electroporation, nucleofection, and microinjection, have a high delivery efficiency in vitro with limited in vivo and clinical therapeutic application.48

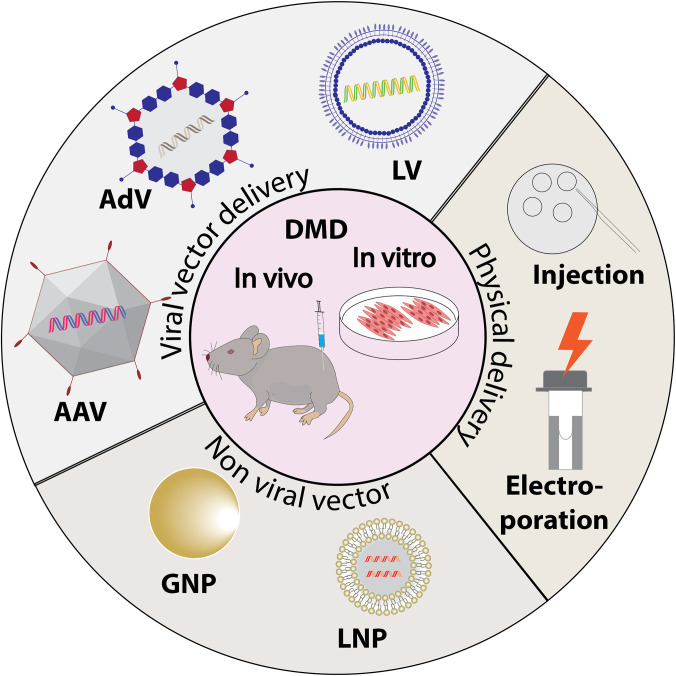

FIG. 2.

Summary of the delivery vectors that have been used in CRISPR-DMD research. Physical and non-viral vector delivery are mostly applied in in vitro stage, while viral vectors are heavily used in preclinical work in mice and dog models of DMD.

Recently, lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery has advanced for in vivo gene editing92,93 and as a vaccine platform.94,95 Although the efficiency of skeletal muscle delivery of the non-viral vector is low compared to viral methods, nanoparticle delivery offers the unique advantage of low immunogenicity, reduced cytotoxicity, and ease of synthesis in the laboratory.96,97 Below, we detail the delivery methods, viral and non-viral, used in DMD animal models.

A. Viral vector delivery

1. AAV

AAV, a non-enveloped viral vector classified as dependoparvovirus from the family Parvoviriade, is a single-stranded DNA virus that contains replication genes (rep), capsid genes (cap), and assembly activating protein (AAP). Despite its simplicity, AAV is capable of transducing both dividing and non-diving cells.98 Currently, 11 AAV serotypes have been isolated from nature with each AAV serotype varies in its capsid sequence, primary attachment receptors, and co-receptor specificity.99,100 The AAV capsid serves as the primary determinant of tissue tropism—the ability of the virus to infect specific tissue. While the tissue tropism can be distinct in each serotype, several tissues such as the liver, skeletal muscle, and heart, can be transduced by multiple serotypes. Skeletal muscle is the second most commonly transduced organ after the liver, with AAV1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and rh10 serotypes used in vivo with various efficiency.100–102 Efficient transduction to muscle tissue in systemic delivery requires high AAV dosages, presenting a challenge for clinical translation. Efforts to improve the selectivity for transduction by engineering AAV capsid using rational design or directed evolution have emerged. Two recent capsid variants of AAV with enhanced skeletal muscle tropism have been reported: AAVMYO and Myo-AAV. These variants have shown preferential transduction of muscle tissue by 5–10 fold and enabled potent delivery of gene therapeutics in muscle from lower and safer therapeutic doses.103,104

Despite the AAV's favorable editing in skeletal muscle, for CRISPR-Cas9 DMD application, AAV has another challenge due to its small packaging capacity of ∼4.7 kb.105 This is about the size of the SpCas9 nuclease (∼4.3 kb) and far below the length of full dystrophin cDNA (∼14 kb). Many exciting approaches to overcome the AAV size limit for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 complex have been made: (1) switching the SpCas9 to smaller Cas9 so the Cas9 and gRNA can fit into one vector or (2) using dual AAV vectors to carry either Cas9 and gRNA-donor template complex separately or to deliver split SpCas9, split base-editors, or split prime-editors (see Table I). Smaller Cas9 orthologous such as SaCas9, CjCas9, and Nme2 encode ∼3.2, ∼2.9, and ∼3.2 kb, respectively, leaving room for gRNAs and AAV regulatory sequences.51,52,106 Despite its large size, SpCas9 is still an attractive choice given its least restrictive PAM sequence. Moreover, delivering SpCas9 and gRNA in separate vectors allows gRNA vector levels to be adjusted. It was found that a higher gRNA/Cas9 ratio restores dystrophin more effectively and improves muscle function more pronouncedly.107 Splitting SpCas9 into two by using trans-splicing inteins, an autocatalytic protein that enables ligation of flanking exteins (polypeptide) into a functional protein, can be as effective as full-size SpCas9.108 The size of the adenine base editor (ABE) and prime editor (PE) are significantly larger than AAV size, around ∼5.4 and ∼6.3 kb, respectively. Both editors can be split into two and delivered in a similar fashion as split SpCas9 does and conserve the editing efficiency when compared to its native form.72,109 Multiple AAV vectors have also been used in dystrophin gene transfer to overcome the size limit. Researchers have demonstrated that dual AAV with overlapping vectors can deliver mini-dystrophin.110–112 A full-length dystrophin reconstitution has also been shown, albeit in a very low efficiency, with triple AAV vectors utilizing hybrid inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and trans-splicing.113

Therapeutic adaptation of AAV to treat DMD began with gene replacement. The first evidence of systemic AAV microdystrophin transduction showed functional improvement of limb muscle in mdx mice.114 Several mini- and microdystrophin sequences have been engineered to produce a shortened but functional dystrophin with a size of about 4 kb. The milestones in the development of microdystrophin have been excellently reviewed elsewhere.115 Currently, there are several ongoing clinical trials for AAV microdystrophin gene transfer (NCT03368742, NCT03375164, NCT03362502, NCT03769116, and NCT05096221). CRISPR-mediated preclinical studies have also presented promising dystrophin restoration using AAV in DMD animal models using different serotypes of AAV (Table I). AAV8 and 9 have been demonstrated to mediate targeted gene editing in satellite cells, thus may provide a long term gene repair effect for DMD.47,116,117

While having shown as a safe and efficient vector for preclinical and clinical studies, the FDA has approved two AAV-based gene therapies for retinal disease and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). However, safety concerns regarding the recombinant AAV vector integration in the host genome are still being investigated. Early evidence of insertional mutagenesis in AAV gene delivery has been shown in the mucopolysaccharidosis type VII mouse model. It was reported that mice that received the systemic recombinant AAV treatment develop hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic angiosarcoma.118 Since this initial finding, researchers are characterizing the AAV integration events in more detail. From several mouse studies that report cancer formation after AAV gene delivery, it is suggested that the insertional mutagenesis is potentially mediated by multiple factors such as the age of mice, vector promoter, vector dose, and underlying liver disease.119 Although the risk of oncogene activation associated with AAV integration in humans remains theoretical—since lack of data available to date, this potential risk needs to be included in therapeutic safety evaluation.

2. Lentivirus

Lentiviruses (LV) are enveloped RNA retroviruses with the unique capacity to transduce a wide range of cell types, both mitotic and post-mitotic cells. LV vectors have prolific use in gene therapy applications due to their comparatively large capacity (∼8kb) and stability of transgene expression. The most common and well-characterized LV serotype is derived from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and has demonstrated long-term episomal transgene expression in vivo and in vitro.120–122 While derived from HIV, most lentiviruses are generally nonpathogenic in humans; moreover, the third-generation of lentiviral vectors produce virus with enhanced biosafety by eliminating HIV accessory gene tat and introducing deletions in 3′ Long Terminal Repeats (LTR) thus reducing the likelihood of activating nearby genes.123 Although LVs with improved semi-random insertional mutagenesis profiles have been developed, there is still a risk of insertional mutagenesis.124

For muscle gene therapy, the capacity of LVs to integrate and transduce muscle cell progenitors, such as satellite cells, gives an advantage over episomal-based delivery vectors such as AdV and AAV. However, in general, this integration ability provides both advantages and disadvantages in therapeutic application. Genomic integration gives a sustained therapeutic expression, but the semi-random pattern of LV integrations may result in insertional mutagenesis leading to oncogene activation. Although current available studies for newer LV generation reported no oncogenesis cases related to LV insertion, previously LV has been reported to induce cancer in mice.125 Based on the random integration property of the LV vector and lack of systemic bioavailability to skeletal muscle, it has not been tested by systemic administration to animal models of DMD.

For DMD therapy, LV has been used to package anti-sense RNAs to induce exon skipping to restore dystrophin expression in patient-derived DMD myoblasts.126,127 CRISPR-mediated restoration of the DMD reading frame through paired gRNA exon deletions has been accomplished in patient-derived myoblasts using LVs to transport CRISPR.59,128

3. Adenovirus

Adenovirus (AdV), a non-enveloped dsDNA virus, is a robust vector for gene delivery and gene-based immunization. The most widely used adenoviral vector for these applications is derived from human AdV5. As one of the earliest vectors used in gene therapy, half of the total gene therapy clinical trials worldwide employed AdV as a delivery vector, typically for cancer therapies and vaccines.129 AdV has been considered as an ideal vector delivery for skeletal muscle, due to its ability to transduce postmitotic cells and large viral insert capacity. However, numerous reports demonstrated that AdV only transduces efficiently in immature or regenerative muscle cells but not in mature skeletal muscle fibers.130 This low transduction efficiency occurs because aged skeletal muscle cells lose coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR), a primary receptor for AdV. Groups have developed multiple strategies to improve the efficiency of AdV in skeletal muscle by modifying fibers, knobs, and capsid of the virus.131,132 In addition, AdV safety was also actively being improved which resulted in the third-generation, high-capacity AdV (HC-AdV) that lack all viral coding sequences. Thus, making it significantly less cytotoxic and less immunogenic enabling sustained expression of therapeutic genes as well as providing a larger capacity (∼37 kb).133

Unlike lentivirus, AdV lacks native integration machinery, and thus is generally considered to be a non-integrating vector.134 However, several studies reported random integration into host chromosomes after AdV treatment.134,135 Safety considerations in clinical trial translation could be one of the reasons for limited reports about AdV-mediated CRISPR delivery for DMD. While limited, in vitro studies in DMD myoblast cells successfully removed up to 500-kb fragments comprising a major DMD mutational hotspot.56,133 CRISPR-AdV5 intramuscular delivery also demonstrated successful dystrophin restoration of up to 50% and systematic improvement of the mdx mice muscle function.136 AdV has also shown to be an efficient vector to deliver HDR-mediated correction in muscle stem cells that show dystrophin restoration in transplanted mdx mice.137

B. Non-viral vector delivery

1. Organic (lipids and polymers)

Non-viral vectors are a chemically diverse gene delivery toolbox. As vectors with potentially lower immunogenicity compared to viral vectors, the clear benefits of using non-viral delivery in various biomedical applications are countered by the lack of delivery efficiency to skeletal muscle body-wide and concerns about the lack of adequate data regarding their toxicity. Currently, the most explored non-viral delivery is lipid nanoparticles (LNP). LNP delivery modalities were first approved as a carrier for siRNA138 and gained broad use as the first approved vaccines in the US for SARS-CoV-2.95,139

Usually, LNPs are composed of an ionizable lipid, a phospholipid, a sterol, and a lipid-anchored polyethylene glycol (PEG).140 A vast range of LNPs has been used to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 components. The lipid composition of the LNP formulation significantly affects CRISPR-Cas9 drug delivery. Recently, several reports have demonstrated that LNP offers the most efficient in vivo delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components to the liver.141–143 There are many commercially available cationic lipids, but there is still a vast chemical space available for LNP optimization.144 For in vivo gene delivery, LNPs encapsulating mRNA (mRNA-LNPs) must surmount various intracellular and extracellular barriers such as avoiding nuclease degradation, retaining mRNA stability in physiological fluids, escaping endosomes for productive translation to proteins, and avoiding kidney and phagocyte clearance.145,146 Lipid molecules are comprised of three domains: a hydrophilic head, a hydrophobic tail group, and a linker connecting the two moieties. There are three types of lipids: cationic, ionizable, and other types of lipids such as cholesterol, polyethylene glycol (PEG), and phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Cationic lipids are positively charged lipids such as 1,2-di-O-octadecenyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTMA), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), and 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP).147,148 Although positively charged, ionizable lipids are neutral in a physiological pH. Ideally, the LNP formulation contains a cationic or ionizable lipid with a sterol or phospholipid.143,149 The addition of PEG or cholesterol can improve the stability, delivery efficacy, and biodistribution of nanoparticles.150

A few reports have used LNPs to deliver CRISPR-mediated DMD therapies in animal models. LNP delivery of Cas9 has resulted in a reduction of off-targets and an adaptive immune response to LNPs carrying a Cas9-expressing plasmid in particular.151–153 The main challenge in delivering Cas9 formulated as mRNA or protein is maintaining the stability of the mRNA or protein after LNP delivery.151 A study investigating the stability of Cas9 mRNA and gRNA inside an LNP demonstrated that encapsulated mRNA and gRNA were stable and intact for at least 24 h with low immunogenicity that permitted repeated administration of the LNP in vivo. In the same study, it was additionally demonstrated that dual guide excision of exon 45 restored functional dystrophin expression in DMD-patient myoblasts and a humanized mouse model with an exon 44 deletion using intramuscular injections of the same mRNA formulation encapsulated in an LNP.154 Additional LNPs engineered for enhanced encapsulation of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) successfully deleted exon 45, restoring dystrophin expression in the E × 44 mouse model.155 A commercial LNP encapsulating plasmid expressing Cas9 and sgRNAs also successfully restored dystrophin expression through an HDR-mediated insertion of exon 7 in the GRMD model using a donor plasmid.156 These studies collectively demonstrate the potential of LNPs to facilitate gene-editing restoring the open reading frame with the reduced mounting of an immune response compared to viral delivery.

Alternatively, polymers and polymer coatings have been used to deliver Cas9 to muscle. A nanocapsule containing a GSH cleavable polymer coating a ribonucleoprotein composed of Cas9 protein complexed with a gRNA efficiently edited HEK293 cells without causing significant cytotoxicity effects compared to lipofectamine.157 Moreover, the nanocapsules were also found to induce effective gene editing in vivo in the eyes and muscles of transgenic mice. Finally, it was exhibited that the nanocapsules produced could retain stability upon freeze-drying, were more versatile due to surface modification, and were less cytotoxic. To date, no efficient systemic skeletal muscle gene editing has been demonstrated with LNPs or polymers.

2. Inorganic

Gold nanoparticles (GNP) have also been used as a method to transport genes, drugs, proteins, and small molecules.151 Their advantage as a delivery system includes their diverse surface coatings,158 nontoxic core, and the range of their core sizes.159 With a range of golden core sizes from 1 to 150 nm, the nanoparticles can better correspond to the size of the biomolecule, allowing for easier transport and dispersal.160 Their nontoxicity and surface coatings are key elements to their target efficiency. With evidence showing that they are continuously nontoxic after multiple days,161 GNPs are considered an inert platform for therapeutic delivery.162

GNP has promising outlooks as potential therapy so far. Recent studies have turned to use them in novel instances in conjunction with CRISPR as a transport mechanism, termed CRISPR-Gold.163,164 CRISPR-Gold has been used to resolve point mutations causing DMD. Lee et al. were the first to apply GNP in CRISPR-DMD editing and assessed the host immune response against the nanoparticle.164 Pro-inflammatory cytokines in the plasma were not initially up-regulated after CRISPR-Gold editing, suggesting the absence of a broad immune response. However, although the concentration of plasma cytokines was stable two weeks post-injection of CRISPR-Gold, increased numbers of CD45+ and CD11+ leukocytes were detected, suggesting the recruitment of innate immune cells and inflammation in the treated sites.164

3. Virus-like particles (VLPs)

Recently, virus-like particles (VLPs) assembled by viral proteins but lacking a viral genome, which have been previously used to deliver mRNA, have been developed for delivering gene editing machinery. VLPs are capable of packaging mRNA, RNPs, or proteins containing CRISPR components and are highly modular for engineering packaging sizes and tissue targets.165,166 The transient delivery of VLP-encapsulated cargos preserves the targeting capabilities of viruses without the associated risks of viral genome integrations and sustained expression. Most VLPs are developed using retroviruses due to a spherical envelope shape and a large diameter (100–200 nm).167 Furthermore, because specificity is determined by glycoproteins expressed on the surface of the viral envelope, the viral envelope can be modified to target different cell or tissue types.166,168

The components of VLP retroviruses include a core structural capsid protein for retroviruses, gag, which self-assembles into the capsid and the envelope proteins, providing targeting specificity.169 VLP-encapsulated RNPs for CRISPR-Cas9 and base editors have successfully accomplished high in vitro and in vivo editing rates.166,170–173 For DMD, an extracellular vesicle presenting the VSV-G protein containing an RNP targeting exon 53 successfully restored dystrophin expression in a the del52hDMD/mdx model, which is a humanized model with an exon 52 deletion.174 Furthermore, a VLP delivery system termed NanoMEDIC was developed has achieved over 90% exon skipping in DMD patient-derived iPS-myoblast, sustained exon skipping in a luciferase reporter mouse model, and 1.6% exon 23 skipping in the mdx model.175

IV. KEY CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTIVE SOLUTIONS

A. The complex nature of DMD

The etiology and pathogenesis of DMD offer unique and significant obstacles for gene therapy development. The first and foremost challenge is that the size of dystrophin is 2.3 Mb with 79 exons; thus, making it susceptible to highly sporadic mutations.176 Although exon 45–55 appears to be the hot spots, this heterogenous mutation makes the mutation-based therapy only work for up to 60% of patients.177 The idea to broaden the patient spectrum by replacing the mutated dystrophin is conceptually ideal. However, this idea is extraordinarily challenging due to the size of full-length dystrophin cDNA that surpasses the packaging capacity of the AAV vector and the large percentage of muscle in the body. Striated muscles, both skeletal and cardiac muscles, are hard to edit due to their high level of organization of the sarcolemma membrane and fascia separation in each muscle. While the challenge of the size of the dystrophin cDNA has apparently been resolved by the discovery of microdystrophin, there are concerns about the functionality of this shortened dystrophin. An attempt to restore full-length dystrophin by delivering superexon donor encoding exon 52–79 to replace the mutated region after exon 52 has shown a promising result.178 However, this approach does not compare the phenotypic difference between microdystrophin and full-length cDNA dystrophin expression.

The immune environment of DMD presents a specific challenge for gene therapies. DMD is characterized by a lack of dystrophin-mediated structural stability resulting in cyclical myofiber degeneration and regeneration that stimulates innate immune and inflammatory responses. Exposure of cytoplasmic materials containing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) to post-contraction damage in DMD tissue activates chronic innate inflammation due to pattern recognition receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLRs). It has been demonstrated that the ablation of TLR2 and TLR4 proteins that responds to certain endogenous host DAMPs improves the pathophysiology of mdx mice through the reduction of pro-inflammatory gene expression, macrophage infiltration, pro-inflammatory polarization, and fibrosis.179,180 Recruitment of immune cells due to muscle damage further promotes DMD pathology through cytokine signaling reinforcing the pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Macrophages have a key role in skeletal muscle regeneration including classically pro-inflammatory macrophages aiding in damaged cell removal and pro-regenerative macrophages promoting regeneration through satellite cell crosstalk, which results in high macrophage localization in DMD tissues.181 Granulocytes such as mast cells and neutrophils recruited at sites of tissue damage additionally secrete cytokines that up-regulate inflammation and damage surrounding cells due to the nonspecific release of granules containing degrading substances such as reactive oxidation species (ROS).182,183 The high concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines and immune sentinels localized in DMD tissue present a significant challenge for the transduction of gene therapies. Due to the high level of immune activity in DMD tissues, developing increasingly immune-evasive transport mechanisms is a goal for DMD applications.

B. Toxicity and off-target accumulation

An ideal delivery vehicle for in vivo gene editing would maximize cargo delivery to target cells (e.g., skeletal and cardiac muscle) and minimize off-target tissue accumulation and toxicity. AAV and LNPs frequently lead to off-target distribution such as delivering the therapeutic gene to non-muscle tissue such as the brain, lung, salivary gland, bone marrow, and predominantly liver.102,184,185 As the largest organ in the body, effectively delivering a systemic AAV therapy for DMD requires an exceptionally high dose of viruses (>1014 vg/kg).115 Thus, there is significant interest to design novel AAV variants which can exhibit superior potency and proceed efficiently through all stages of transduction when compared to the natural capsid AAV variants.186 Systemic delivery of AAV9 administration in infants with SMA has resulted in hepatic toxicity along with successful motor neuron transduction in different animal models. Therefore, to ensure the safety of the approach while transducing the spinal motor neurons to higher animals, Hinderer et al., injected high doses of a neurotropic AAV vector closely related to AAV9 (AAVhu68) to three juvenile non-human primates and three piglets carrying a human survival motor neuron (SMN) transgene.187 It was demonstrated that the nonhuman primates (NHPs) exhibited elevated levels of transaminase enzyme leading to acute liver failure. Piglets showed proprioceptive deficits and ataxia, thereby requiring euthanasia. These results imply that regardless of the capsid serotype or transgene, intravenous delivery of AAV vectors at high concentrations may cause systemic and sensory neuron toxicity. Wienmann et al., identified a myotropic AAV (AAV9 mutant), namely, AAVMYO. Compared to the 183 AAV capsid variants, AAVMYO was found to be highly efficient in transducing the muscle cells after the systemic delivery of moderate doses. The authors also validated the results on the protein level by injecting mdx mice intravenously with 2 × 1011 vg and 1 × 1012 vg.104 When compared to the traditional AAV9, AAVMYO yielded higher microdystrophin expression and was observed to be much superior in terms of transducing multiple types of muscle fibers [type I (for slow-twitch), IIa and IIb (for fast-twitch)]. El Andari et al., recently published a study where they employed a semirational, combinatorial bioengineering approach that consists of AAV capsids and myotropic AAV peptide library screens. The authors identified two peptides displaying chimeric AAV capsids known as AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3. It was observed that AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 efficiently targeted the affected organs (skeletal muscle, heart, and diaphragm), thereby reducing the off-target expression in mouse models of X-linked myotubular myopathy and DMD. The chimeric AAV, AAVMYO3, induced significantly higher microdystrophin expression and improved muscle function and the chimeric AAVs, AAVMYO3 and AAVMYO4 increases the life span, reinstated the muscle strength, and corrected the muscle morphology of Mtm1-KO (myotubular myopathy) mice.188 Tabebordbar et al., modified the outer protein shell of the AAV, specifically between amino acid number 588 and 589 with a random 7-mer peptide sequence and created AAV capsid libraries for directed evolution.103 The capsid protein was expressed under CK8 or MHCK7 promotors in HEK293 cells for quantification and subsequent library generation. After nearly three rounds of in vivo selection, the authors selected a variant that comprised a random heptamer peptide (RGDLTTP) named “MyoAAV 1A.” In a similar titer, this variant has a higher production yield of recombinant AAV compared to AAV9. MyoAAV 1A was found to transduce the mouse muscle cells and NHPs with higher efficiency than AAV9 after systemic delivery. Dystrophin expression, determined using immunofluorescence and western blot assay, revealed that dystrophin was restored to a wider area when injected with MyoAAV 1A. Additionally, the capsid variants showed no indication of toxicity accumulation in the liver or other unfavorable side effects in all mice or NHP subjects. Thus, MyoAAV 1A demonstrates significantly improved effectiveness and safety for muscle delivery compared to conventional and broadly used AAV9. These properties of the AAV capsid variant are expected to attract the attention of researchers involved in the rational design of AAV-based gene therapy for treating DMD.

C. Immune responses against CRISPR and delivery vectors

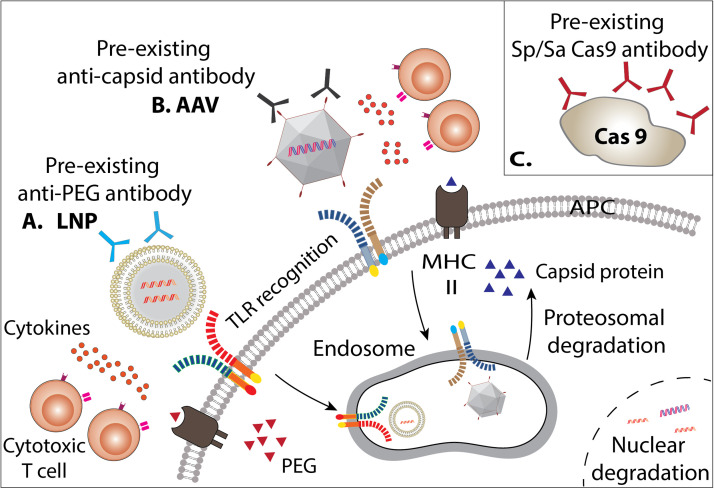

The immune system remains a significant barrier for delivery vectors and CRISPR components including Cas9 and gRNA (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Schematic figure of cellular and humoral immune response against CRISPR therapeutic delivery. (a) Immune responses targeting LNPs include neutralizing preexisting antibodies against PEG and other LNP surface components, which result in APC endocytosis clearing the LNPs and inciting an immune response. Cytotoxic T cells can recognize LNPs and secrete inflammatory cytokines. Endosomal LNP recognition and MHC II presentation can result in mounting an inflammatory response and degradation of internal components can occur after nuclear entry. (b) Immune responses targeting AAV include neutralizing pre-existing antibodies against the AAV capsid, resulting in APC endocytosis clearing the AAV and inciting an immune response. Cytotoxic T cells can recognize AAV and secrete inflammatory cytokines. Endosomal recognition of AAV and MHC II presentation of AAV capsid proteins to T cells and B cells will also mount an immune response. Degradation of internal components can occur after nuclear entry. (c) Preexisting antibodies against Cas9 have been detected, neutralizing, and clearing the protein.

1. Immune response against Cas9

The abundance of infections caused by bacteria harboring commonly used CRISPR systems (e.g., S. aureus and S. pyogenes) result in preexisting immunity against the widely used Cas9 types. Cas9 preexisting immunity in humans has been reported in a high prevalence ranging from 10% to 96% for SpCas9 and 2.5%–78% for SaCas9.189–191 Consequently, this immunity limits the efficiency of gene editing in mice and compromise dystrophin expression in canine models.192,193 Furthermore, a single administration of AAV-Cas9 can trigger an adaptive immune response in mice. A long-term study in DMD mice reported that treated adult mice elicit a humoral immune response against the SaCas9 protein, while no immune responses were detected in treated neonate mice.194 Mice treated with AAV encoding dSaCas9 similarly developed humoral immunity to SaCas9 and increased liver enzymes.195 In adult wild-type mice, Cas9 expression in the tibialis anterior muscle resulted in a swelling of the lymph nodes with elevated cell counts and an elevation of CD45+ hematopoietic cell frequencies.108 A recent study in a larger animal model reported a local and systemic administration of AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 vector for DMD therapy stimulated a humoral and cellular immune response against Cas9 and muscle inflammation, while AAV without Cas9 showed minimal or undetectable cellular immunity.192 Taken together, the reports suggest that Cas9 immunity represents a major obstacle for CRISPR therapy.

To modulate immune responses against Cas9, several groups are aiming to evade preexisting immunity by eliminating immunodominant Cas9 epitopes while maintaining function196 and deriving Cas9 orthologs from bacteria with a lower incidence of human infection such as IgnaviCas9 from a hyperthermophilic bacterium found in Yellowstone Park.197 Other potential strategies include using T regulatory cells to induce immune tolerance against the Cas9 protein and controlling SpCas9-reactive T effector responses.191,198 Another possible solution is exploring the suitability of other Cas families for genome editing applications. For example, Cas12a is a more immune evasive substitute for Cas9 since it is derived from nonpathogenic bacteria (Acidaminococcus sp. and Lachnospiraceae bacterium).53 Cas12a, also known as CRISPR from Prevotella and Francisella 1 (Cpf1), is a type V-A endonuclease and a class II CRISPR-Cas9 system.199 It has been confirmed that Cas12a-mediated genome editing could correct DMD mutations as efficiently as Cas9.200,201 Although these types of Cas proteins are less likely to be detected by preexisting host immune responses, a model predicting Cas12a cellular and humoral immune reactivity also demonstrated that some peptides in Cas12a proteins could bind to common human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I or class II alleles.202 To date, there is no report about Cas12a's preexisting immunity or immune responses related to Cas12a activity.

The other alternative solution to reduce Cas9 immunity is by delivering a less immunogenic form of Cas9. An alternative to plasmid delivery is messenger RNA (mRNA), which does not integrate into the genome.146 The modification of mRNA with uridine depletion can also reduce the innate immune response of mRNA.203 Cas9 protein is also a promising alternative to reduce the risk of harmful immunogenic events.152 However, protecting the Cas9 from serum is a challenge.

2. Immune response against viral delivery modalities

After a significant setback for gene therapy in 1999, when a clinical trial patient died from a systemic inflammatory reaction against an adenoviral gene therapy vector, biotechnology companies, and research laboratories considered the immune response to gene therapy a primary safety concern.204 Viral vectors were the prominent choice for gene delivery as the virus is naturally efficient to deliver DNA. Adenoviruses are notoriously inflammatory delivery vehicles and are primarily used as vaccines and oncolytic applications. In contrast, AAV has a milder inflammatory profile and is used as gene therapy for numerous target tissues.205

Since 2009, 14 muscular dystrophy clinical trials have been conducted and many of them have been completed using an AAV vector. Based on the safety data reported, there were minimal adverse events and zero deaths attributed directly to the immune response to AAV capsids.206 However, Solid Biosciences halted its Phase I/II clinical trial after one subject had adverse reactions in response to a high dose of AAV-9 microdystrophin vector administration. Similarly, Pfizer was put on clinical hold in their phase III CIFFREO by FDA after three severe adverse events of muscle weakness and heart inflammation. This hold has been lifted recently after the investigation stated the adverse effect is associated with certain gene mutations.207,208 Pfizer also halted their enrollment in phase 1b PF-06939926 after unexpected death of a participant in the clinical trial.207 While the cause of death was not fully described yet, high-dose systemic AAV administration needs more consideration and extensive analysis.

AAV immunity presents an additional challenge to developing AAV-CRISPR therapies as a substantial portion of the population has AAV preexisting immunity in the form of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs).209 This adaptive immunity can limit therapeutic efficacy. The first completed trial in muscular dystrophy using an AAV vector is the limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LMGD-2D) gene replacement therapy.210 Phase I clinical trial data of three LMGD-2D patients after 6 weeks to 3 months of observation reported that AAV1 neutralizing antibodies were very low before the treatment and started to rise and peak as early as one week after the treatment. However, it was shown that Nabs titers have no influence on gene expression. Cellular immunity to AAV1 capsids following intramuscular injection was also detected from weeks 2 to 12.210 Therefore, current gene therapy clinical trial enrollment uses preexisting antibody titers as exclusion criteria.211

Recent in vivo data indicate that employing different AAV serotypes or Cas9 orthologs can overcome the immune barrier in multiple administration of CRISPR-AAV.193 Clinically, cellular immune responses to the AAV capsid can be managed with transient immunosuppressants such as steroids. The fact that the AAV vector genome can persist long-term also raises concerns about the accumulation of off-target damage and immunogenicity due to the prolonged exposure of Cas9152,165 However, several long-term observations in CRISPR-DMD gene editing reported that there are insignificant changes in off-target mutations in treated mice at one month or after one year of treatment (Table I). Despite being shown to not increase off-target activity, since a large fraction of the human population may have NAbs to AAV (up to 50% depending on the assay and cutoff titer), engineering AAV vectors to escape these immune responses is a major focus of research labs and biotechnology companies.

Low immunogenic AAV capsids were engineered by rationally mutating or replacing multiple amino acid residues, such as serine (S), threonine (T), lysine (K), and tyrosine (Y), in the AAV capsid to avoid ubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated capsid degradation.212–214 Avoiding proteasomal capsid degradation will prevent T-cells recognition, thus escaping the host immune response against the vectors. Another potential improvement is modifying the AAV cassette. Modifications using tissue-specific promoters and combining the AAV vector genome with small viral peptides (ICP47 and US6) were shown to reduce CTL-mediated clearance.215,216 Removal of CpG motifs in the ITR also potentially reduces the immunogenicity of AAV.217–219 Rational engineering of CpG motifs-free ITR showed no effect on the elimination of the biological function of the AAV vector; micro-dystrophin expression and histological evaluation resulted in similar findings when compared to unmodified AAV vector.220

3. Immune response against non-viral delivery modalities

For non-viral delivery, improving immunogenicity includes optimizing the payload (DNA or mRNA) and the vector. For LNP-mRNA prophylactic vaccines, the intrinsic immunogenicity of LNP formulated mRNA through pattern recognition receptors is beneficial to induce a potent human primary immune response.221 However, for LNP-CRISPR-based gene therapy applications, the immune response from delivery modalities should be minimized, to prevent unwanted immunogenicity to the gene-corrected target cells. Interactions of LNPs with the innate immune system, which mostly depend on their chemical properties, can have various immune effects such as immune cell activation, inflammation, adaptive immune responses, and complement activation or complement activation-related pseudo allergy (CARPA).222,223 Many researchers have explored the relationship of structure-activity and showed that LNP properties such as particle size, component molar fractions, and surface chemistry affect the interaction of LNP and the immune system.223,224

The size of LNPs has a major impact on the uptake of these materials by cells (particularly phagocytes of the innate immune system),225 the initiation of an innate immune response, and their overall bio-distribution in vivo. With an increase in size, the surface-to-volume ratio of LNPs decreases, which affects their interactions with the innate immune system by activating or avoiding the complement system.223 While the relationship between the size of LNPs and innate immune response does not seem linear,222,223 a recent study reported that LNP size has a substantial influence on mRNA vaccine immunogenicity. It was demonstrated that any particle size yielding a robust immune response in NHP with smaller diameters was substantially less immunogenic in mice.225 Modifying the surface properties of LNPs will also alter their immune response. A recent study developed a new LNP formula that alters the surface charge of the LNP from positive to neutral. A neutral surface charge is important in reducing the immune uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) system,155 and it was also reported that raising PEG density on the surface of LNPs could minimize their immune-provoking activity.226 Ionizable lipids are the major component of LNP that influence the efficacy and tolerability of LNP-based therapy. These lipids are recognized as a key element of LNPs for cellular uptake and endosomal escape. As the ionizable lipid in the first approved RNAi drug, DLin-MC3-DMA is highly potent and demonstrated good tolerability in several clinical trials.227 However, further lipid design optimization that incorporates biodegradability such as L319 is needed.228,229 L319 has demonstrated swift clearance from tissues and plasma in mice and NHP, reducing the immune response and toxicity, without compromising the efficacy.228 An ionizable lipid with hydrophobic tails formulation also displayed the advantage in tackling immune response. This formulation allows repeated intramuscular administration of CRISPR-Cas9 mRNA in DMD mice with low immunogenicity, thus enabling the accumulation of therapeutic effect.154 Current literature on LNP-CRISPR-based DMD therapy preclinical studies is mainly focused on therapeutic efficacy in cells and intramuscular injections in mice, which offers very limited LNP-host immune response safety data.

PEG shielding has been identified as a method to avoid immune recognition by reducing LNP interaction with serum complement. However, increasing the concentration of PEG in the lipid mol. % of the LNP formulation not only reduced the complement activation, cytokine production, and macrophage recognition in mouse models, but also reduced their efficacy.226 Therefore, to design an effective LNP, it is important to optimize the ratio of PEG surface density that provides the best defense for LNP without diminishing the efficacy.

Anti-PEG immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies production, due to preexisting antibodies against PEG or induced by the long circulation of nanoparticles, leads to a loss of effectiveness upon repeated LNP administration.229 Furthermore, a clinical trial was terminated after the patients showed an immediate immune response due to preexisting PEG-specific antibodies.230 Recently, Senti et al., demonstrated that anti-PEG antibodies elicit complement activation (classical pathway and alternate pathway) by PEGlytaed liposomes and LNPs. The loss of membrane integrity due to membrane attack complex (MAC) formation led to reduced lipid packing integrity and safety of the PEGylated lipid formulations.231 Another study reported that the concentration of Anti-PEG IgG and IgM antibodies rose significantly after the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The LNP-mRNA formulation in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine include small amounts of PEG. It was concluded from this study that anti-PEG antibodies led to systemic reactions and enhanced PEG particle–leukocyte association in human blood.232 Although, there is evidence that PEG-mediated antibody responses can be reduced by altering the alkyl chain of the PEG-lipid conjugate,233 exploring PEG alternatives for coating strategies such as hydrophilic synthetic polymers will be vital for future LNP development.234

D. Off-target and on-target mutagenesis

Several studies have demonstrated that Cas9 binds to off-target sites, which induce cleavage at outside target sites.235–237 Efforts to mitigate the unintended off-target cleavage by synthesizing various high-fidelity Cas enzyme variants (Cas-HF1 and Hypa-Cas9) have been shown to reduce off-target editing, however, this also affects the enzymatic efficiency of on-target DNA cleavage.238,239 Therefore, there is a need to further develop engineered Cas9 enzymes that reduce off-targets and maintain or improve efficiency. The next generation of CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes such as base editors and prime editors may reduce the impact of off-target mutations since they do not create double-strand breaks. However, these modalities are very goal-specific, so not all gene editing experiments can incorporate these methods.

To apply the CRISPR-Cas9 system as a therapeutic modality in humans, a complete understanding of their off-target effects and a standard pipeline to detect these events to minimize the possibility of detrimental consequences are required. Small frequencies of unintended alterations in non-target locations could raise significant issues because ex vivo and in vivo therapy will need the alteration of extensive cell populations. Since the first introduction of CRISPR in 2012, concerns about measuring its safety have been progressively addressed. There are several methods to screen for off-target editing, each with advantages and disadvantages: (a) Whole genome resequencing is unbiased but costly to sequence at the depth needed to detect rare off-target events,240 (b) Deep sequencing to identify mutations at off-target sites is performed by determining sequence similarity with on-target sequences or binding site libraries. These approaches are highly sensitive but potentially biased by the in silico selection of off-target sites and the potential to miss large rearrangments,235–237 (c) Immunoprecipitation protocols can be used to identify dCas9 binding sites and DNA repair proteins at off-target sites,241,242 (d) Digenome-seq is an in vitro assay that uses double-strand breaks to enrich at off-target loci but requires larger sequencing reactions,243 (e) GUIDE-seq in a cell culture method where integration of an oligonucleotide is detected at global off-target sites and is not as sensitive as in vitro methods,244 (f) CIRCLE-seq and CHANGE-seq are in vitro assays that use DSB for targeted enrichment of circularized DNA and is very sensitive and requires smaller sequencing output.245,246 Ideal methods may use a combination of highly sensitive methods (broad net) followed by more specific methods to assess risks of off-target mutagenesis.

In addition to off-target mutagenesis, on-target mutagenesis such as unintended large deletions and complex genomic rearrangements with potentially undesirable consequences at the targeted sites are also detected after Cas9 cleavage.247–251 Loss of heterozygosity in edited cells and truncation of a partial or full chromosome are also described as unwanted on-target complications of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing.252–256 These issues might go unnoticed since genotyping analysis of the targeted site is typically performed in conventional short-range PCR and amplicon short-read sequencing. Large deletions in the 5′ or 3′ region will be missed since the PCR priming will not occur because of the deleted primer binding region. To detect on-target mutations, several pipelines to thoroughly investigate the events in the targeted region have been developed. A combination of long-range PCR genotyping and long-read sequencing has shown to capture the unseen large deletions and genome rearrangements.250 Other alternatives for simple and cost-effective detection are quantitative genotyping PCR (qgPCR) and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping-based tools.257 Recently developed long-read sequencing techniques such as nanopore Cas9-targeted sequencing (nCATS) and droplet-based target enrichment coupled have also been demonstrated to enrich a large fragment of genomic DNA while maintaining native modifications and avoiding amplification bias.256,258 Unidirectional amplification and short read sequencing has been used to identify large deletions, inversions, and vector integrations in preclinical work.194,259,260

V. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE OUTLOOK