Abstract

The COVID-19 disease causes pneumonia in many patients that in the most serious cases evolves into the Acute Distress Respiratory Syndrome (ARDS), requiring assisted ventilation and intensive care. In this context, identification of patients at high risk of developing ARDS is a key point for early clinical management, better clinical outcome and optimization in using the limited resources available in the intensive care units. We propose an AI-based prognostic system that makes predictions of oxygen exchange with arterial blood by using as input lung Computed Tomography (CT), the air flux in lungs obtained from biomechanical simulations and Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) analysis. We developed and investigated the feasibility of this system on a small clinical database of proven COVID-19 cases where the initial CT and various ABG reports were available for each patient. We studied the time evolution of the ABG parameters and found correlation with the morphological information extracted from CT scans and disease outcome. Promising results of a preliminary version of the prognostic algorithm are presented. The ability to predict the evolution of patients’ respiratory efficiency would be of crucial importance for disease management.

Introduction

The COVID-19 disease, due to the new coronavirus discovered in 2019, causes pneumonia in many patients that in the most serious cases evolves into the Acute Distress Respiratory Syndrome (ARDS), requiring assisted ventilation and intensive care [1]. The fragile segments of the population (i.e., elderly and chronically ill) are the most afflicted by the disease, showing a high mortality rate [2–4]. Intensive care units suffered from a shortage of beds and ventilation equipment for COVID-19 affected people during the pandemic outbreak in years 2020-2021. Thus, the identification of patients at high risk of developing ARDS is a key point for early clinical management, better clinical outcome and optimization of the use of the limited resources in the intensive care units.

The dimension of the pandemic promoted a huge research effort word wide and in particular Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been widely used for diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19. Several AI algorithms analyze medical images like X-rays and CT and showed a great potential not only for COVID-19 diagnosis but also for segmentation of related lung lesions, providing information on the severity of the disease. High diagnostic accuracy has been previously reported but several limitations reduce their real clinical applicability, namely due to biases in small datasets and large variability in larger publicly available datasets used for training, together with the lack of standardization in acquisition protocols. In case of prognostic applications, there is the further difficulty of integrating clinical and imaging data. Comprehensive reviews on this topic can be found in [5, 6].

In this work, we propose and study the feasibility of an AI based algorithm to make predictions of patients’ respiratory efficiency based on Computed Tomography (CT) scan, usually taken at some point of patient hospitalization, Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) analysis, routinely used to monitor patient conditions [7], and biomechanical simulations of air flowing inside the lungs (see sec. 4).

In most of the prognostic literature published so far, the morphological information obtained from the imaging is used together with the clinical data and correlations are studied and exploited, although without any direct knowledge of the exact pathological mechanism underlying it [8–13]. To overcome this limitation and to optimize performances, in our proposed algorithm the prediction can be linked, at least in part, to the biomechanical causes underlying respiration, such as regional ventilation. Biomechanical simulations in fact allow to quantify, starting from the CT, the actual airflow in the alveolar zones, taking into account patient-specific anatomy and the eventual presence of co-morbidity, together with using gas exchange equations to assess the exchange of oxygen with the arterial system.

The proposed pipeline can be divided in 3 steps. In a first step lungs are extract from the chest CT and COVID-19 lesions are identified and segmented by a deep neural network. In a second step, a pathophysiological model is constructed and simulation of air flow are performed, so that the regional fluxes are quantified. In the third step the fraction of lesions in lung parenchyma and the air fluxes are merged with ABG acquired at days subsequent to the CT scan and used as input for the prognostic algorithm, which aims to predict patients’ respiratory capability, at subsequent times. Eventually, the algorithm can take into account newly acquired ABG data in a recurrent manner to deliver more accurate predictions.

The purpose of the present paper is to illustrate the conceptual steps devised to analyze radiological and clinical data by a joint AI-driven and knowledge-based approach. At the time of writing, the simulations are still in the validation phase and are not used in the prognostic algorithm. They will be integrated at a later time.

The segmentation deep neural network has been trained and tested on public COVID-19 databases (see Sect. 2). A small database of proven COVID-19 cases with various ABG reports for each patient and unlabeled CT scans were provided by the hospital “Santa Croce e Carle” (Cuneo, Italy). Due to the limited number of cases available, a high-statistic artificial dataset is generated, with the same characteristics of the real one, to further develop and test the prognostic algorithm.

Patient databases

The anonymized database used to setup the prognostic algorithm was provided by the Radiology Department of the hospital “Santa Croce e Carle” (Cuneo, Italy). This database consists of ABG reports and lung CT scans of 61 proved COVID-19 patients with age ranging from 39 to 88 years, and hospitalized during Spring 2020. Eleven of these patients died and 11 were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) at some point. Six of the patients admitted in ICU died. Few patients have more than one CT scan while the number of recorded ABG for each patient ranges between 1 and 195 with different time interval between subsequent reports. Thirty patients have at least two ABGs available. ABGs are available in PDF format that are converted into text files using an optical character recognition algorithm [14]. Since this process may be inaccurate, we performed an extensive and rigorous quality control in order to clean up the data, recognize, and correct possible misinterpreted data. The ABG parameters available to us were: blood values (pH, pO, pCO, pO/FiO, cHCO(p), cBase(B), cBase(ECF)), oxymetric values (ctHB, sO, FOHb, FCOHb, FMetHb), and electrolytic values (K, Na, Cl, Ca, C a(7.4), anionic gap). Metabolic values like glucose and lactate were also available for a total of 21 parameters, from now on referred as ABG parameters. Information as the date of birth, the period of hospitalization, the date of the taken medical exams and the presence of comorbidities were also recorded.

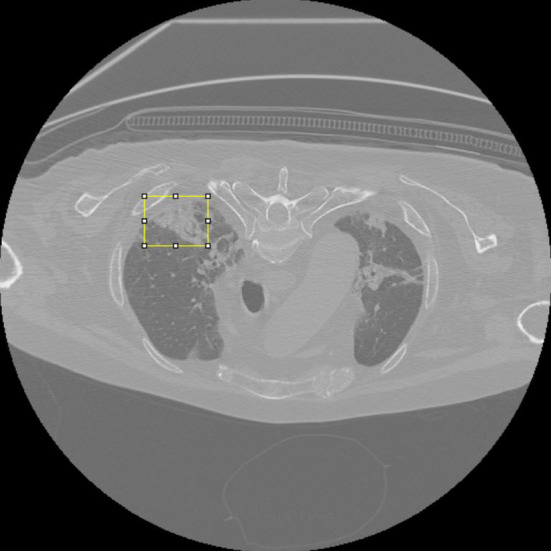

The CT scans were saved as 16-bit files as vtk image formats, with x-y resolution of 700 m and slice thickness ranging from 0.675 mm to 2.5 mm. Figure 1 shows a slice chosen from one of the CT of this database.

Fig. 1.

Lung CT slice of a patient from the “Santa Croce e Carle” database. The yellow box highlights a lesion with ground glass opacities

This database was used to study the correlation of the lung lesions, quantifiable from the CT scan as the count of COVID-19 specific lesions in the lung tissues, with the time evolution of the ABG parameters and the disease outcome. The CT scans were also used as input to biomechanical simulations.

Since the CT from the above database were not annotated, a lesion segmentation algorithm has been developed. Two public databases were used to train and test the COVID-19 lesion segmentation network (described in Sect. 3). In both of them, patients are anonymous and a lesion segmentation map was available. The images of these databases were annotated by expert radiologists and annotations include lung field and COVID-19 lesions, sometimes grouped into the typical Ground Glass Opacities (GGO) and Consolidations (CL).

The first public database is composed of 750 lung CT slices from 150 CT scans of COVID-19 confirmed cases, saved as 8-bit images in jpg format from the KISEG study [15], whose resolution is 1.0 mm. Each slice has a corresponding ground truth annotation, or mask, saved as a separate file in png format, needed as target for the segmentation training. The annotations were obtained through a manual segmentation at the pixel contrast level by five expert radiologists with at least 10 years of experience, and reviewed by a second tier of three senior independent radiologists, each with over 20 years of clinical experience. Each pixel is assigned to four classes of segmentation regions: background, lung field, GGO and CL.

The second public database, published on the Zenodo repository on April 20th, 2020 [16], contains 20 labeled COVID-19 CT scans made of a variable number of slices, with an overall good quality. The 3D volumes of this collection have a variable shape from 512 512 200 up to 12 512 301 voxels with a variable resolution from 0.76 0.76 1.5 mm up to 0.68 0.68 1.0 mm. The ground-truth masks (files available in nifti format), instead, are manually annotated with 4 different labels that are: background, left lung, right lung and infection (without separating GGO and CL). The annotations were performed by two radiologists and verified by an experienced radiologist.

Covid lesion segmentation network

Image segmentation is a long-standing challenge in medical image analysis. As stated in Sect. 1, focusing on the specific task of segmenting the different areas of the lungs to accurately identify lesions, many AI approaches providing high accuracy in a reduced time have been developed, but with possible methodological limitations due, for example, to biases in the used datasets.

Among the different possibilities, two dimensional (2D) algorithms, that perform the segmentation task on a slice by slice basis, retain the lowest computational cost and the fastest prediction time, suiting well, also, for real-time uses. One of the state-of-the-art 2D model, the U-net [17] was specifically designed for biomedical image segmentation, achieving important results that outperformed, at that time, others Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) applied to this field. We chose a DeepLabv3 [18] model already used for segmenting COVID-19 lesions in [8]. DeepLabv3 is a type of CNN designed to improve segmentation tasks. Regarding the training process, we used a combination of cross entropy and dice coefficient as a loss function optimized via stochastic gradient descent with batch size equal to four images per iteration and for a total of 200 training epochs. All the training process was done on an NVIDIA DGX-1 system using two Tesla V100 GPUs with 32GB of memory each.

Each pixel is assigned by the network to three mutually exclusive classes: 0 for background, 1 for lung field and 2 for COVID-19 lesions thus merging GGO and CL classes in the Kiseg dataset. All images were pre-processed to reduce the impact of possible differences like for example in the acquisition protocol, by conversion to 8-bit format and z-scoring. The model has been trained on 80 of the Kiseg dataset and tested on the remaining 20. The average accuracy over the slices, calculated as the fraction of correctly classified pixels, is 98 in the test set. As a figure of merit, we also considered the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC), which is a similarity measurement defined as twice the intersection divided by the union of two samples, which in this case are the segmented pixel counts and the ground truth (the lesions segmented by the radiologists). The DCS over the COVID-19 lesions is 89. We studied the performances on a dataset never saw by the network by applying it on the Zenodo dataset, obtaining a pixel accuracy of 96 and a DSC of 74.

The trained segmentation network is applied to the CT images from the “Santa Croce e Carle.” The lungs are initially segmented from the chest y employing the open source network “lungmask” [19] before the pre-processing step begins. The output of the network is used to compute the COVID-19 lesion fraction, defined as the number of voxels assigned to lesions over the total number of voxels in the lungs, without distinction of the airways from the parenchyma. We used on our Cuneo images the COVID-19 lesion segmentation network available in MONAI (https://monai.io/), which was trained on a third independent database. The standard deviation of the difference between the fraction of lesioned tissue obtained with our and MONAI network is 5, which can be considered as a systematic error on our measurement.

Biomechanical simulations

Biomechanics of breathing is a multi-step process. At first, it uses a specialized imaging software for reconstructing the lungs airways and tissues to construct a digital twin of the lungs. It is then followed by solving the equations that govern the dynamics of the air flow during the breathing cycle, the Navier-Stokes equation of aerodynamics. Such computational framework is often employed in engineering applications, known as Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), to reproduce the flow structure in complex environments. Here the method is customized to solve air motion in respiratory organs in the presence of physio-pathological conditions.

Simulations were based on an accurate three-dimensional reconstruction of the airways and the lung tissues. It is then followed by the definition of a physio-pathological model for the parenchyma and by taking into account the Covid lesions, followed by the numerical solution of the equations that govern air motion. For this work, we use the proprietary software from MedLea to deliver both the digital twin three-dimensional reconstruction of the respiratory organs and the biomechanics of regional ventilation.

The starting point of simulations is the patient-specific anatomical geometry obtained by post-processing the CT acquisition, by reconstructing the entire organ and by including the COVID-19 lesions as part of the segmentation process. The pipeline is fully automatic such that, starting from the chest CT scan, it sequentially performs lung and identification of the pulmonary lobes followed by detecting the trachea and bronchial airways. A special image filter is used to enhance the presence of filament- and tubular-like structures as employed to subsequently generate the airways morphology to the finest resolution accessible by the CT acquisition equipment.

This preliminary phase identifies up to the seventh generation of the airways, which typically corresponds to the finest diameter of 0.5 mm, the airways are then treated by a regularization method to eliminate finite-resolution artifacts. In order to convey air into the distal regions of the lungs, the airways are prolonged by a synthetic airways by a generation method that takes into account the scaling laws obeyed bifurcating airways in terms of characteristic length, diameters and tapering effects. The entire airways structure has the form of a topologically consistent, hole-free, surface mesh that is directly utilized by the numerical solver to convey air into the five main pulmonary lobes.

In such model the parenchyma is taken to be any part of the lungs that does not belong to the airways (e.g., the so-called dead space). The parenchyma is modeled by accounting for the spongy characteristics of the lung tissues that for the healthy tissue produces a uniform medium where air diffuses. The model for the spongy tissues was found to reproduce known ventilatory results in healthy patients [20]. The pulmonary lobes further define sub-volumes where air flows in a containerized fashion. The presence of air bubbles arising from emphysema is identified by a knowledge-based algorithm that is based on a pre-determined contrast interval.

Our model includes the local permeability of healthy tissues by considering a spatially averaged set of parameters without considering the fine structure of tissues. The model further includes the pathological conditions as extracted by processing the CT data. The lesions associated to Covid (namely the GGO and CL patterns provided by the lesion segmentation network) and to emphysema (the so-called air bubbles) are identified and transformed into special zones that take into account the impaired local ventilation by modeling them as having zero air flux. The complete model is crucial to quantify the perfusion of air to the blood stream in the available healthy regions, while those with GGO, CL and emphysema are taken to be unavailable to gas exchange. To summarize, the final physio-pathological model contains the detailed morphological information and, in order to probe the functional response, a rather small number of coefficients that represent i) the breathing cycle with patient-specific inspiration volumes and rates, ii) the airways and healthy part of the parenchyma and iii) the GGO, CL and emphysema regions.

The relevant physics of air passage is encoded by a numerical framework that operates under the constraints set by the biomechanical model. MedLea’s technology is based on an optimized Lattice Boltzmann numerical solver that achieves an automatic conversion of the CT scan to the structural model, setup and execution of simulations, being performed on CPU and GPU architectures. At its roots, the Lattice Boltzmann method is time-explicit and its large manageability stems from the underlying structure of the volumetric mesh based on cubic voxels. Figure 2 shows the model obtained for a patient of the “Santa Croce e Carle” database.

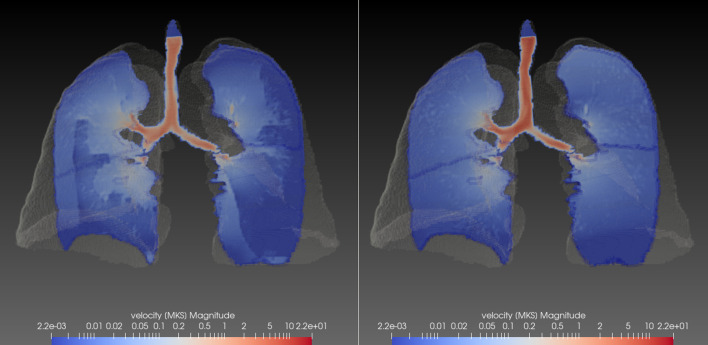

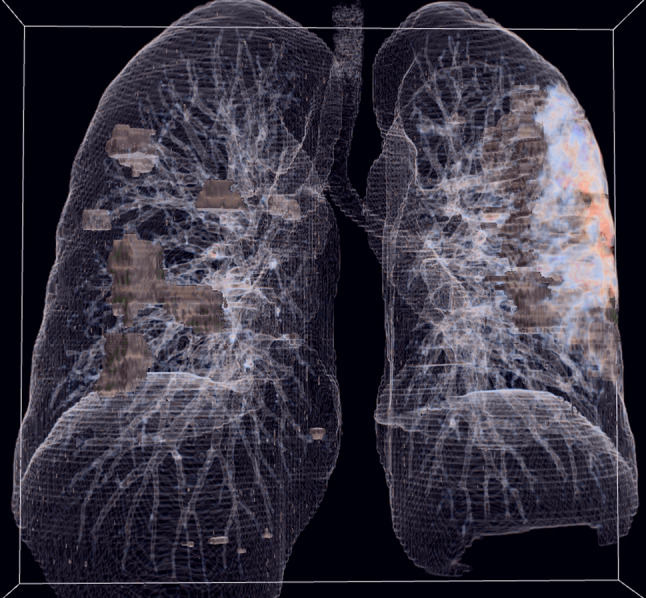

Fig. 2.

Example of the model for a patient of the “Santa Croce e Carle” dataset. The volumetric rendering shows the lungs, the trachea and the internal airways. The presence of GGO is represented as a solid object. The extraction of airways and parenchyma and the identification of lesions is the starting basis for biomechanical model and the subsequent simulations

The CFD method is inherently weakly compressible and well suited for reproducing transient flows under moderately Mach numbers (<0.3), as pertinent to airflow in the large and small airways. For studying respiratory patterns, the Lattice Boltzmann method offers outstanding versatility in the variety of transport conditions encountered in the breathing organ and describes a broad variety of flow patterns [21].

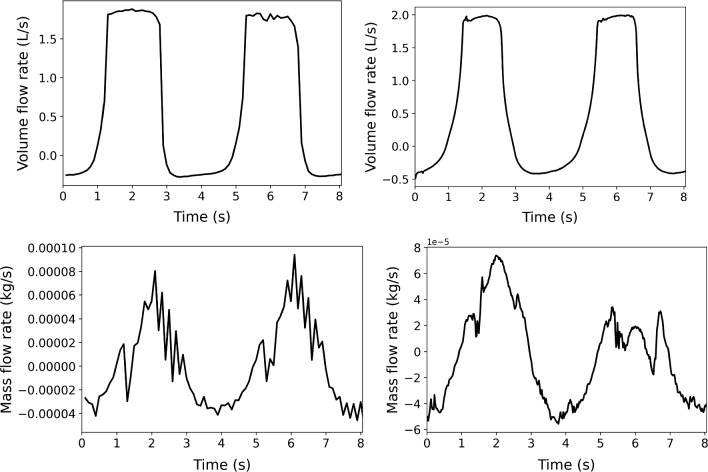

Figure 3 shows the effecu of the Covid lesions on the biomechanical simulations for a selected patient presenting substantial lesions. The effect of bilateral lesions is the presence of regions of low ventilation and low local air fluxes. Figure 4 shows the volumetric flow rate in the trachea and the mass flow rate in the healthy region of the parenchyma acquired over two respiratory cycles, each having a duration of 4s. The second respiratory cycle is used to compute ventilatory statistics. The presence of 28 of lesions reduces the total mass flow rate by 42.

Fig. 3.

Example of results of biomechanical simulations for a patient presenting 28% of Covid lesions. In the left panel the Covid lesions are taken into account in the biomechanical model where in the right panel the lesions are substituted by a completely healthy parenchyma. The contours of the velocity magnitude (units in m/s and in logarithmic scale), are shown on a reference frontal slice and at the maximum inspiration during the breathing cycle

Fig. 4.

Example of results of biomechanical simulations for the same patient of Fig. 3 reporting volumetric flow rate in the trachea (upper panels) and the mass flow rate (lower panel) in the healthy region of the parenchyma acquired over two respiratory cycles, each having a duration of 4s. The second respiratory cycle is used to compute ventilatory statistics. The left and right panels are for the case with Covid and without-Covid lesions, respectively, as in Fig. 3. The presence of 28% of lesions reduces the total mass flow rate by 42%

From the lung model of each patient, the air flux inside the lung during a respiratory cycle can be computed, which can be used in turn as input of the prognostic system.

ABG analysis

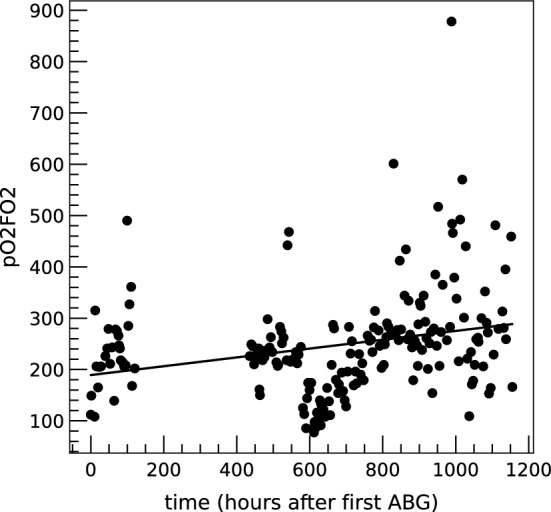

The ABG parameters as a function of time have been considered for patients with more than one ABG and fitted to a linear function to intercept the trend. As an example, Fig. 5 shows the time evolution of the ABG parameter pO/FiO (oxygen partial pressure divided by the fraction of inspired oxygen) with a linear fit superimposed for a patient who needed intensive care and was monitored for several days. As seen in the plot, large fluctuations in data can be attributed in this case to abrupt responses to changes in the assisted ventilation conditions. Other possible sources of variability, common to other ABG parameters, are operator variability (protocol, human errors) and intra-patient variability (time of the day, temperature etc.).

Fig. 5.

pO/FiO as a function of time for a patient of the “San Croce e Carle” database. A linear fit is superimposed

Prognostic algorithm

The proposed AI based prognostic algorithm takes as input the fraction of COVID-19 lesions, the ABG parameters at times close to the time of CT and the air flux from the biomechanical simulations, to predict the ABG parameters at subsequent times. The idea at the basis of our algorithm is that the morphological information from the CT (lung damage), the functional information from the biomechanical simulations (regional air fluxes) and ABG parameters are correlated with the evolution of the disease. It is fair to assume that this correlation can become weaker as time passes due to abrupt changes in patient conditions. To mitigate this problem, the algorithm can be recurrent, i.e., it can self-update on the basis of new ABG data that are acquired at subsequent moments. At the time of writing the biomechanical simulations are underway thus air flux is not included in the following.

We chose a Support Vector Regression (SVR) algorithm for this task [22], which takes as input the COVID-19 lesion fraction and ABG parameters at times close to the CT time and outputs the ABG parameters over the next 20 hours. Since the “Santa Croce e Carle” database is quite small, we studied the feasibility of this approach on a synthetic dataset, i.e., in which fictitious ABG data and COVID-19 lesion fraction are generated according to the distributions observed on the real patients. The original database contains 30 patients with more than one ABG, each of them having its own COVID-19 lesion fraction determined by the segmentation network. As described in Sect. 5, the time evolution of each ABG parameter for each patient was obtained from linear fits. Thus in the “Santa Croce e Carle” database, 21 ABG parameters at the CT time, a COVID-19 lesion fraction and 20 slopes for the ABG parameters time evolution are associated to each of the 30 patients with more than one ABG. In order to build the synthetic dataset, we first used a family of rotation-based iterative Gaussianization (RBIG) transforms [23], that transforms the original multidimensional distribution to a multivariate Gaussian distribution. The dataset is then generated according to the multivariate Gaussian distribution obtained in this way and then transformed back with the RBIG inverse transformation. This procedure is necessary since common programming languages provide tools for generation according to multivariate Gaussian distributions, while our initial distributions were not Gaussian. For each synthetic patient the time evolution corresponding to 120 hours, in steps of 4 hours, was generated. Possible fluctuations of ABG parameters, as observed on data, are included. Five hundred patients were generated in this way; the SVR has been trained using 80 of the patient synthetic dataset and tested on the remaining 20.

Results

The “lungmask” network and the COVID-19 lesion segmentation network described in Sect. 3 have been applied to the CT from the “Santa Croce e Carle” database. For each CT, the fraction of the COVID-19 lesions was computed.

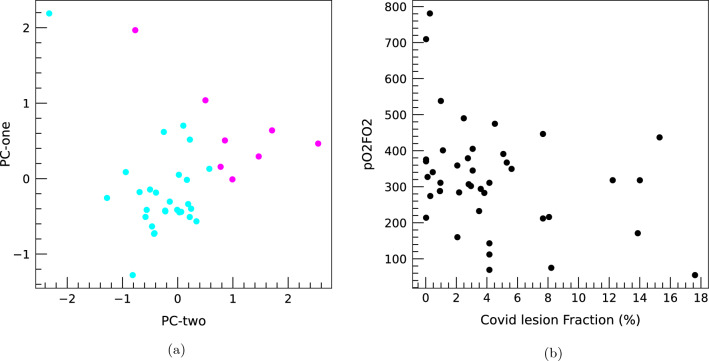

In order to study the correlations of the ABG parameters with the severity of the disease, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) [24]. For each patient with more than 1 ABG available, the ABG parameters at the CT time and their slopes are considered. The resulting principal component contains the hemoglobin (ctHB) and parameters related to the acid-base unbalance (pCO, HCO-, cBase). The most important parameters of the second component are related to the presence of oxygen in the arterial blood (pO, sO). The percentage of the explained variance for the first two components is 24 and 16, respectively, indicating that they are not sufficient to describe the complexity of the data. Figure 6a shows the two first PCA components for patients with different disease outcome: the plot shows there is a clustering of the most serious cases with respect to the less serious ones in this space.

Fig. 6.

a First two components in the PCA analysis described in the text. Each point corresponds to a patient. In purple there are the patients that needed intensive care at some point and/or died while in light blue there are the less severe cases. b Correlation plot between the pO/FiO ratio at the CT time versus the COVID-19 lesion fraction

In a second step, we investigated the relation between ABG parameters and the fraction of COVID-19 lesions, which contains the morphological information from the CT scan. Pearson correlations were computed between the COVID-19 lesion fraction with both ABG parameters at the CT time and their slopes. The highest correlations, equal or greater than 50 (in absolute value), were found with hemoglobin (ctHB, -55), cHCO (+54), cBase(B) (+51), cBase(Ecf) (+52), partial pressure of CO (pCO, + 50). The pO/FiO ratio has a correlation of -33 while other correlations are lower than 30 (in absolute value). The correlations with the slopes are much lower, below 15. As an example, Fig. 6b shows the correlation plot between the pO/FiO ratio at the CT time versus the COVID-19 lesion fraction.

We then moved to the training of the SVR prognostic algorithm using the 80 of the patients of the synthetic dataset generated for this purpose, to predict the value of ABG parameters for the 20 hours subsequent to the CT. We evaluated the performances of the algorithm on the test set by computing the correlations between the predicted and the true values of the ABG parameter slopes. As an example, the correlation between the true slope of the ABG parameter sO with the slope extracted by the values predicted by the algorithm corresponds to a Pearson correlation coefficient of 45 and to a p-value of a paired t-Student test of 0.33, indicating that the averages of the two distributions are compatible. sO is one of the most important parameters to describe patients’ respiratory capability and to monitor the course of the COVID-19 disease.

Discussion

In this study, we described an AI prognostic system which aims to make predictions of ABG parameters, in particular of oxygen levels, for patients affected by COVID-19. Such a system would allow a more effective management and a more efficient use of hospital resources. The system is based on three ingredients: lung CT scan, ABG analysis taken at different times, biomechanical simulations. We used a small database from the Italian hospital “Santa Croce e Carle” (Cuneo, Italy) for our preliminary analysis.

The first step of our pipeline is the implementation of a deep neural network to segment COVID-19 lesions from lung CT, which provides the degree of lung damage, computed as the fraction of the lesioned tissue over the total lung volume. We used a state-of-the-art model that we developed and trained using two publicly available databases. The performances of this segmentation network are quite good, but more recently developed methods can be considered to achieve top generalization and accuracy score like, for example, Vision Transformers [25]. One of the well-known problems of segmentation networks is in fact generalization, i.e., the capability to guarantee good performances on images (CT in this case) from databases not used in the training process. More studies on different CT databases about generalization capability of our network are needed.

The second step are the biomechanical simulations which constitute the link between the morphological information from the CT and the physiological information that ultimately correlates with ABGs. The simulations take the segmented CT as input and provide the local air flux inside the lung tissues.

Finally, a prognostic algorithm is built from the information above (COVID-19 lesion fraction, air flux) with ABG analysis taken at times around the CT time. The algorithm is designed to provide the ABG parameters at subsequent times and of particular relevance are parameters related to oxygen levels in the blood. Since at the time of writing the biomechanical simulations were underway, we did not include them in the preliminary version of the algorithm.

The idea at the base of such system is that a correlation exists between the degree of lung damage at a given time, ABG data at the same time, with the evolution of the disease. In order to check this hypothesis we studied the CT and the ABG reports of the “Santa Croce e Carle” database. In the database, together with the initial CT, multiple ABG are available for most of the patients. The study of the ABG parameters as a function of time shows large fluctuations that can be in part attributed to inter-operator and intra-patient variability. A possible method to overcome this limit is to average several ABG parameters, for example over one day, which would reduce fluctuations. To apply this method a larger database with many patients with a large number of ABG reports per day is needed.

The ABG parameters at the CT time were correlated with the severity of the disease through a PCA. This analysis shows that there is indeed a correlation between ABG and disease outcome since the most severe cases (need of ICU at some point and death) tend to cluster in the bi-dimensional space of the first 2 principal components. These results point in the direction that the information encoded in the ABG parameters are useful to predict the outcome of the disease.

We also made an attempt to correlate the morphological information from the CT with the ABG data. The time evolution of the ABG parameters were fit to a linear function to intercept the trend for each patient with more than one ABG available. The ABG parameters at the CT time and their slopes were correlated with the fraction of the COVID-19 lesions in the lungs. There is nowadays a large literature about this topic. Saturation (sO) is not among the most correlated variables with the COVID-19 lesion fraction in our database (Pearson correlation coefficient of -20) but the value we obtain is in qualitative agreement with several works, see for example [8] and [26], where also the correlation with hemoglobin agrees. In [27] a correlation of FiO/PO with COVID-19 lesion fraction in agreement with our finding is reported. This parameter is of potential relevance for linking ABG values to biomechanical simulations since it is related to the oxygen in arterial blood independently of possible assisted ventilation. The most relevant correlations we found were for parameters related to acid base balance (pCO, HCO, Base). The slopes of the ABG parameters are less correlated with the lesion fraction (Pearson correlation coefficient less than <15). From the above results, we can conclude that there exists a correlation between CT and ABG parameters.

We then studied the feasibility of building a SVR prognostic algorithm to predict patient respiratory capability. The algorithm predicts ABG parameters in a time interval of 20 hours after the CT time. The correlation between actual and predicted slope of the ABG parameter is of the order of 45 and statistical tests indicate that the averages of the two distributions are compatible. This result can be improved by implementing the algorithm in a recurrent manner, i.e., by taking into account ABG measurement that are taken at times subsequent to the CT acquisition. The main limitation of our study is that the SVR was trained on synthetic data given the smallness of the available clinical database, while a real large database to include more biological variability is needed. If a large real dataset was available more complex algorithm can be eventually used. We also plan to integrate the results of biomechanical simulations that will add valuable information for the predictions.

Conclusions

In this paper we propose an AI-based prognostic algorithm to make predictions of ABG parameters, in particular those related to oxygen levels, from lung CT and ABG data, with the help of biomechanical simulations of air flux inside the lungs. We studied a small database of proven COVID-19 cases and we found correlations between lung damage, ABG data and disease outcome. A first simplified version of the prognostic algorithm has been developed which shows promising results and various directions for improvements have been identified. Such a prognostic algorithm would allow for better therapeutic strategies and management of hospital resources by indicating patients more likely to develop a critical condition in advance.

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to thank Enzo La Bua from Azienda Ospedaliera S.Croce e Carle of Cuneo, Italy, and Dr. Dante Chiappino from Ospedale del Cuore G. Pasquinucci, Fondazione Monasterio, Massa, Italy, for valuable discussions and insights.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, the preparation of the database and the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by MedLea Srls.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Authors’ comment: The data that support the findings of this study are available from MedLea Srls but restrictions apply to the availability of these data and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Medlea Srls].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Focus Point on Progress in Medical Physics in Times of CoViD-19 and Related Inflammatory Diseases. Guest editors: E. Cisbani, S. Majewski, A. Gori, F. Garibaldi.

References

- 1.Gibson PG, Qin L, Hon Puah S. Med. J. Aust. 2020;213(2):54–6. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, Chow N, Cohn A, Dowling N, Ellington S, Gierke R, Hall A, MacNeil J, Patel P, Peacock G, Pilishvili T, Razzaghi H, Reed N, Ritchey M, Sauber-Schatz E. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell T, Bellin E, Ehrlich AR. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hast.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Mao B, Liang S, Yang JW, Lu HW, Chai YH, Wang L, Zhang L, Li QH, Zhao L, He Y, Gu XL, Ji XB, Li L, Jie ZJ, Li Q, Li XY, Lu HZ, Zhang WH, Song YL, Qu JM, Xu JF. Eur. Respir. J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01112-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabavi S, Ejmalian A, Ebrahimi Moghaddam M, Ali Abin A, Frangi AF, Mohammadi M, Saligheh Rad H. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;135:104605. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M.R.D. Driggs, M. Thorpe, J. Gilbey, M. Yeung, S. Ursprung, A.I. Aviles-Rivero, C. Etmann, C. Mc Cague, L. Beer, J. R.Weir-McCall, Z. Teng, E. Gkrania-Klotsas, J.H.F. Rudd, E. Sala, C.-B. Schönlieb, Nature Machine Intelligence (2021) 10.1038/s42256-021-00307-0

- 7.Bezuidenhout MC, Wiese OJ, Moodley D, Maasdorp E, Davids MR, Koegelenberg CFN, Lalla U, Khine-Wamono AA, Zemlin AE, Allwood BW. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0004563220972539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang K, Liu X, Shen J, Li Z, Sang Y, Wu X, Zha Y, Liang W, Wang C, Wang K, Ye L, Gao M, Zhou Z, Li L, Wang J, Yang Z, Cai H, Xu J, Yang L, Cai W, Xu W, Wu S, Zhang W, Jiang S, Zheng L, Zhang X, Wang L, Lu L, Li J, Yin H, Wang W, Li O, Zhang C, Liang L, Wu T, Deng R, Wei K, Zhou Y, Chen T, Yiu-Nam Lau J, Fok M, He J, Lin T, Li W, Wang G, Cell J. Cell. 2020;181(6):1423–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turcato G, Panebianco L, Zaboli A, Scheurer C, Ausserhofer D, Wieser A, Pfeifer N. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canovi S, Besutti G, Bonelli E, Iotti V, Ottone M, Albertazzi L, Zerbini A, Pattacini P, Giorgi Rossi P, Colla R, Fasano T, Infectious Diseases BMC. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;1:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05855-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quattrocchi CC, Mallio CA, Stortoni L, D’Alessio P, Galdino I, Mattei A, Gallì B, Di Giorgio E, Donatiello MG, Agrò FE. J. Xiangya Med. 2020 doi: 10.21037/jxym-20-109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portale G, Ciolina F, Arcari L, Di Lazzaro Giraldi G, Danti M, Pietropaolo L, Camastra G, Cordischi C, Urbani L, Proietti L, Cacciotti L, Santini C, Melandri S, Ansalone G, Sbarbati S, Sighieri C. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021;10:2075–81. doi: 10.1007/s42399-021-00986-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mergen V, Kobe A, Blüthgen C, Euler A, Flohr T, Frauenfelder T, Alkadhi H, Eberhard M. Eur. J. Radiol. Open. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2020.100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.S. Hoffstaetter, J. Bochi, M. Lee, L. Kistner, R. Mitchell, E. Cecchini, J. Hagen, D. Morawiec, E. Bedada, U. Akyüz, Python Library (2021) https://pypi.org/project/pytesseract/

- 15.LiuKai X, Wang W, Chen T, Zhang K, Wang G. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assisted Interv. 2020 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59719-1_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun M, Cheng G, Yixin W, Xingle A, Jiantao G, Ziqi Y, Minqing Z, Xin L, Xueyuan D, Shucheng C, Hao W, Sen M, Xiaoyu Y, Ziwei N, Chen L, Lu T, Yuntao Z, Qiongjie Z, Guoqiang D, Jian H. Zenodo Dataset. 2020 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3757476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, T. Brox, arXiv (2015) arXiv:1505.04597

- 18.Liang-Chieh Chen, G. Papandreou, F. Schroff, H. Adam, arXiv (2017) arXiv:1706.05587

- 19.Hofmanninger J, Prayer F, Pan J, Röhrich S, Prosch H, Langs G. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s41747-020-00173-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.J.B. West, Pulmonary physiology and pathophysiology: an integrated, case-based approach, 2nd edition, Lippincott Wilkins and Williams

- 21.Bernaschi M, Melchionna S, Succi S. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2019 doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.91.025004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smola AJ, Schölkopf B. Stat. Comput. 2004 doi: 10.1023/B:STCO.0000035301.49549.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laparra V, Camps-Valls G, Malo J. Neural Netw. IEEE Trans. 2016 doi: 10.1109/TNN.2011.2106511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wold S, Esbensen K, Gelad P. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1987 doi: 10.1016/0169-7439(87)80084-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A. Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, D. Weissenborn, X. Zhai, T. Unterthiner, M. Dehghani, M. Minderer, G. Heigold, S. Gelly, J. Uszkoreit, N. Houlsby, arXiv (2021) arXiv:2010.11929

- 26.E. Jimenez-Solem, T. S. Petersen, C. Hansen, C. Hansen, C. Lioma, C. Igel, W. Boomsma, O. Krause, S. Lorenzen, R. Selvan, J. Petersen, M.E. Nyeland, M. Zöllner Ankarfeldt, G.M. Virenfeldt, M. Winther-Jensen, A. Linneberg, M. Mehdipour Ghazi, N. Detlefsen, A.D. Lauritzen, A.G. Smith, M. de Bruijne, B. Ibragimov, J. Petersen, M. Lillholm, J. Middleton, S. Hasling Mogensen, H.-C. Thorsen-Meyer, A. Perner, M. Helleberg, B. Skov Kaas-Hansen, M. Bonde, A. Bonde, A. Pai, M. Nielsen, M. Sillesen, Sci. Rep. (2021) 10.1038/s41598-021-81844-x

- 27.Ippolito D, Ragusi M, Gandola D, Maino C, Pecorelli A, Terrani S, Peroni M, Giandola T, Porta M, Talei Franzesi C, Sironi S. Eur. Radiol. 2021;31:2726–2736. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Authors’ comment: The data that support the findings of this study are available from MedLea Srls but restrictions apply to the availability of these data and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Medlea Srls].