Abstract

Background. Policies mandating the use of lower cost biosimilars in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have created concerns for patients who prefer their original biologic. Purpose. To inform the cost-effectiveness of biosimilar infliximab treatment in IBD by systematically reviewing the effect of infliximab price variation on cost-effectiveness for jurisdictional decision making. Data Sources. MEDLINE, Embase, Healthstar, Allied and Complementary Medicine, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, Mental Measurements Yearbook citation databases, PEDE, CEA registry, HTA agencies. Study Selection. Economic evaluations of infliximab for adult or pediatric Crohn’s disease and/or ulcerative colitis published from 1998 through 2019 in which drug price was varied in sensitivity analysis were included. Data Extraction. Study characteristics, main findings, and results of drug price sensitivity analyses were extracted. Studies were critically appraised. The cost-effective price of infliximab was determined based on the stated willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds for each jurisdiction. Data Synthesis. Infliximab price was examined in sensitivity analysis in 31 studies. Infliximab showed favorable cost-effectiveness at a price ranging from CAD $66 to $1,260 per vial, depending on jurisdiction. A total of 18 studies (58%) demonstrated cost-effectiveness ratios above the jurisdictional WTP threshold. Limitations. Drug prices were not always reported separately, WTP thresholds varied, and funding sources were not consistently reported. Conclusion. Despite the high cost of infliximab, few economic evaluations examined price variation, limiting the ability to infer the effects of biosimilar introduction. Alternative pricing strategies and access to treatment could be considered to enable IBD patients to maintain access to their current medications.

Highlights

In an effort to reduce public drug expenditures, Canadian and other jurisdictional drug plans have mandated the use of lower cost, but similarly effective, biosimilars in patients with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease or require a nonmedical switch for established patients. This switch has created concerns for patients and clinicians who want to maintain the ability to make treatment decisions and remain with the original biologic.

It is customary for economic evaluations to assess the robustness of results to variations in high-cost items such as medications. In the absence of economic evaluations of biosimilars, examining biologic drug price in sensitivity analysis provides insight into the cost-effectiveness of biosimilar alternatives. A total of 31 economic evaluations of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease varied the infliximab price in sensitivity analysis.

The infliximab price deemed to be cost-effective within each study ranged from CAD $66 to CAD $1,260 per 100-mg vial. A total of 18 studies (58%) demonstrated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio above the jurisdictional willingness-to-pay threshold. If policy decisions are based on price, then originator manufacturers could consider reducing the price or negotiating alternative pricing models to enable patients with inflammatory bowel disease to remain on their current medications.

Keywords: biosimilars, economic evaluations, inflammatory bowel disease, infliximab, pharmaceutical policy, review

Tumor necrosis factor antagonists (anti-TNF), a class of biologics used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), were the most costly class of biologics to provincial public payers in Canada, comprising 8.3% of total drug expenditures in 2018.1 In 2018, anti-TNF drugs such as infliximab cost the Canadian health system $1.2 billion dollars,1 and Canada spent $208 per capita on biologics, the third highest amount in the world. Biosimilar biologics were recently introduced in Canada as a lower cost alternative for payers; however, their uptake has been slow.2 Originator biologics have the advantage of longer-term safety and efficacy data, an established usage and acceptance among patients and clinicians, and established patient support programs, but evidence to support the efficacy and safety of biosimilars is increasing.3,4

A biosimilar biologic is similar to its reference biologic drug but is not identical. Biologics are made from living cells and are naturally variable, as opposed to generic drugs, which are chemically synthesized small molecules containing identical medicinal ingredients to its reference drug. Both originator and biosimilar infliximab are in the class of therapeutic agents known as monoclonal antibodies, and they exert their therapeutic effect with a mechanism of action of blocking anti-TNF production in the immune system. Infliximab has been widely used in treating moderate-to-severe IBD in addition to other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Biosimilar infliximab has been shown to be comparably clinically efficacious and safe for the treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).5–9 In 2012, 10.2% of persons with CD and 3.3% of persons with UC received publicly funded infliximab in Ontario, and expenditures of anti-TNFs are increasing.1,10 The average price of one 100-mg vial of originator and biosimilar infliximab in Canada is CAD $999 and CAD $528, respectively, based on provincial formulary prices.11 Typically, treatment is given as a series of induction doses followed by chronic maintenance therapy at regular intervals. The common maintenance schedule of infliximab for IBD is 5 mg/kg every 8 wk, irrespective of treatment with biosimilar or originator. This translates into approximately CAD $4,000 per dose for a 70-kg person. A regimen of 4 vials per dose costs CAD $26,000 per year with originator pricing and CAD $13,730 per year with biosimilar pricing. Based on a national prescription drug spending report, the average yearly cost per person for an anti-TNF treatment is CAD $19,211.1

The high cost of treatment with originator infliximab and the entry of lower cost biosimilars has prompted British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario to adopt a policy that requires newly diagnosed patients insured by public plans be prescribed a biosimilar. In addition, British Columbia and Alberta have mandated, and Manitoba and Ontario are considering mandating, that current patients switch to a biosimilar unless contraindicated. The rationale for these policies has been to increase patient access to medications and to reduce expenditures by public drug programs.12 However, the policy has created controversy among some gastroenterologists and patients due to a lack of long-term data on the safety and efficacy of biosimilars and the rationale behind nonmedical switching.3,13 Because IBD is a chronic lifelong condition, gastroenterologists have indicated a preference for data covering longer than a 1-y follow-up period, particularly in switching patients from originator to biosimilar, due to the potential for immunogenicity and variability of maintenance of response over time.9,14 Although the NOR-SWITCH randomized trial demonstrated that switching from originator to biosimilar was noninferior with continued maintenance therapy over a 52-wk period with a noninferiority margin of 15%, that study was not powered to show noninferiority in individual diseases, and Canadian gastroenterologists have expressed concern that a 15% clinical margin may be too wide.15,16 Furthermore, in a joint position statement, the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada have recommended against nonmedical switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar in patients with stable IBD but suggest that biosimilar infliximab may be started in anti-TNF–naïve patients with active disease.17 To address any suggestion of bias in their position, it is important to note that these organizations acknowledge support from manufacturers/distributors of both originator and biosimilar products.17,18

Since the high cost of originator infliximab was the impetus for the nonmedical switch policy and since biologics cost significantly more than biosimilar IBD treatment does, it was of interest to examine the effect of infliximab price variation on cost-effectiveness analysis results in IBD. It is customary for economic evaluations to assess the robustness of results to variations in high-cost items such as medications. In the absence of economic evaluations of biosimilars, examining sensitivity analyses of biologic drug price conducted as part of economic evaluations of originator infliximab provides insight into the cost-effectiveness of biosimilar alternatives. The objective was to perform a systematic review of economic evaluations in IBD in which infliximab price was varied in sensitivity analysis to inform an assessment of the cost-effectiveness of biosimilar infliximab for individual jurisdictions.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted following the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA).19 The review was not registered, and the protocol was not published.

Study Eligibility

Only economic evaluations that contained a 1-way sensitivity analysis of infliximab price were eligible. Costing studies were excluded. Eligible studies could include originator infliximab, biosimilar infliximab, or both, either as an exclusive comparator or used in sequence with other treatments as part of the treatment paradigm.

Literature Search

A literature search was performed for articles with infliximab as the treatment for IBD and in which the parameter of drug price was examined in 1-way sensitivity analysis. Included studies were English-language economic evaluations in CD and/or UC conducted in any country and published or in press between January 1998 (the year originator infliximab was first approved in the United States) and October 2019, with a final publication year of 2020. Adult or pediatric populations were included. MEDLINE, Embase, Healthstar, Allied and Complementary Medicine, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, and the Mental Measurements Yearbook databases were searched. Search terms included the following: infliximab, crohn*s disease, ulcerative colitis, colitis, inflammatory bowel diseases, cost benefit analysis, cost effectiveness, cost minimization, and cost utility analysis. Search parameters included the automatic removal of duplicates by the OVID search platform within each database. Websites of publicly available economic evaluations such as the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health,20 the SickKids Paediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) Project,21 and the Tufts Medical Centre Center for the Evaluation of Risk and Value in Health Cost-effectiveness Analysis Registry22 were searched as sources of peer-reviewed economic evaluations. Although the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) was not searched directly, these repositories may include NICE economic evaluations. Review articles and conference abstracts were excluded. The search strategy is shown in the PRISMA diagram23 in Figure 1. Eight hundred forty-four abstracts were obtained. Following an initial independent review, 2 abstract reviewers agreed on 147 full-text papers for screening. Any disagreements between the 2 reviewers regarding abstracts that should proceed to full article screen were resolved by discussion and consensus. Following review of the 147 full-text articles by 2 independent reviewers, disagreements regarding eligibility were addressed by discussion and consensus, resulting in 31 eligible studies.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search screening and study inclusion based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA).

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data related to publication year, jurisdiction, study population, treatment strategy, analytic technique, type of IBD, whether originator or biosimilar infliximab was evaluated, time horizon, payer perspective, jurisdictional willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold, and sponsorship were extracted and tabulated by a single reviewer. Each publication was critically appraised by a single reviewer using the Drummond Checklist,24 and the number of criteria met were determined. From the 31 articles, the infliximab price used in the reference case and the price range used in the 1-way sensitivity analyses were identified. The reference case price was converted into 2019 CAD using annual average exchange rates listed by the Bank of Canada and the Canadian Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Products Consumer Price Index up to December 2019 (2019 CAD $1 = 2019 US $ 0.7536).25–27 As this review focused on a specific health intervention, infliximab, a context-specific method for inflating costs rather than a generic tool such as the Campbell Collaboration Converter,28 was preferred. The cost-effective price of infliximab based on the WTP threshold stated in each article was documented, although the stated WTP threshold was not always consistent with the jurisdictional WTP threshold. stated WTP thresholds most often varied in papers taking a US or Canadian third-party payer perspective due the lack of formally published jurisdictional thresholds. European and Asian studies generally reported their jurisdictional thresholds. While the cost-effective price was converted to CAD to facilitate interpretation and comparison, it is important to determine cost-effectiveness based on the threshold provided by the author, as the threshold can vary by jurisdiction based on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and the domestic budget constraint.29,30 Cost-effective prices for each country were plotted as a function of stated WTP thresholds.

Ethics

As a literature review not involving human subject data, ethics review was not required. No external grant funding for this study, other than salary support, was obtained.

Results

The literature search identified 844 abstracts based on the search terms. Based on screening of the abstracts, 147 articles were deemed potentially eligible as they were related to health economics, IBD, and referred to infliximab. Examination of the 147 full-text articles revealed 31 (21%) that met the eligibility criteria and contained a 1-way sensitivity analysis on the price of infliximab. Ineligible studies were not economic evaluations (n = 87) or did not contain a 1-way sensitivity analysis on infliximab price (n = 29). Studies that included a probabilistic sensitivity analysis of infliximab price were excluded because a defined infliximab price range used for the sensitivity analysis could not be determined. The 31 evaluated articles were conducted in a variety of jurisdictions including the United States (13), Canada (6), Spain (2), and 1 each from Sweden, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Italy, Japan, China, and Iran. Two studies included multiple European perspectives.

The title and primary findings of the 31 included articles are shown in Table 1. Table 2 indicates summaries of the comparison type, the analytic technique, the type of IBD, whether the study used biosimilar or originator infliximab or both, the time horizon, the payer perspective, the sponsor, and the number of Drummond checklist criteria met. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 contain expanded findings for each study. A detailed critical appraisal is found in supplemental Table 3.

Table 1.

Description of Studies

| First Author, Country | Study Title | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Findings, Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio | ||

| 1 | Aliyev et al.,31 United States | Cost-effectiveness comparison of ustekinumab, infliximab, or adalimumab for the treatment of moderate-severe Crohn’s disease in biologic-naive patients |

| IFX dominated ADA and UST; NMB of IFX v. UST = US

$29,798 NMB IFX v. ADA = US $9,943 | ||

| 2 | Ananthakrishnan et al.,32 United States | Can mucosal healing be a cost-effective endpoint for biologic therapy in Crohn’s disease? A decision analysis |

| ICER of mucosal healing v. clinical response = $47,278/QALY gained | ||

| 3 | Arseneau et al.,33 United States | Cost-utility of initial medical management for Crohn’s disease perianal fistulae |

| 6MP/met + 3 infusions of IFX + 6MP as second-line therapy

(intervention 1) ICER v. 6MP/met = US $355,450/QALY

gained IFX + episodic reinfusion v. 6MP/met (intervention 2) ICER = US $360,900 6MP/met + IFX as second-line therapy (intervention 3) ICER = US $377,000 | ||

| 4 | Baji et al.,34 Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Netherlands, United Kingdom | Cost-effectiveness of biological treatment sequences for fistulising Crohn’s disease across Europe |

| ICER of bsIFX (most cost-effective single treatment) v. standard

care: Belgium: €38,420/QALY gained; France: €43,721/QALY gained; Germany: €72,551/QALY gained; Hungary: €34,684/QALY gained; Italy: €44,059/QALY gained; Netherlands: €59,101/QALY gained; Spain: €54,427/QALY gained; Sweden: €69,491/QALY gained; UK: €63,908/QALY gained; ICER of IFX v. standard care: Belgium: €38,420/QALY gained; France: €43,721/QALY gained; Germany: €95,540/QALY gained; Hungary: €49,286/QALY gained; Italy: €58,215/QALY gained; Netherlands: €59,101/QALY gained; Spain: €64,898/QALY gained; Sweden: €79,663/QALY gained; UK: €69,793/QALY gained; bsIFX v. bsIFX + ADA, bsIFX v. bsIFX + VEDO, bsIFX + ADA v. bsIFX + ADA + VEDO also reported | ||

| 5 | Bashir et al.,35 Canada | Cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes of early anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha intervention in pediatric Crohn’s disease |

| ICER public payer: CAD $2,756/wk in steroid-free remission

gained Societal: CAD $2,968/wk in steroid-free remission gained | ||

| 6 | Beilman et al.,36 Canada | Early initiation of tumor necrosis factor antagonist-based therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease reduces costs compared with late initiation |

| NMB of early initiation of IFX = CAD $16,975 NMB of late initiation of IFX = NMB: −$103,184 Early v. late initiation of ADA also reported | ||

| 7 | Blackhouse et al.,37 Canada | Canadian cost-utility analysis of initiation and maintenance treatment with anti-TNF-alpha drugs for refractory Crohn’s disease |

| ICER of IFX v. usual care = CAD $222,955/QALY gained ICER of ADA v. usual care = CAD $193,305/QALY gained ICER of IFX v. ADA = CAD $451,165/QALY gained | ||

| 8 | Bolin et al.,38 Sweden | The cost-effectiveness of biological therapy cycles in the management of Crohn’s disease |

| ICER of continued combination with IFX + metabolites (treatment

1) v. withdrawal of IFX (treatment 2) = SEK 755, 449/QALY

gained ICER of treatment 1 v. continued IFX – metabolites (treatment arm 3) = SEK −79,933 | ||

| 9 | Candia et al.,39 Canada | Cost-utility analysis: thiopurines plus endoscopy-guided biological step-up therapy is the optimal management of postoperative Crohn’s disease |

| ICER of thiopurines postsurgery plus endoscopy-guided biological step-up therapy v. endoscopy-guided full step-up therapy = CAD $26,305/QALY gained | ||

| 10 | Catt et al.,40 United Kingdom | Value assessment and quantitative benefit-risk modelling of biosimilar infliximab for Crohn’s disease |

| INHB of bsIFX v. originator IFX = 0.04 | ||

| 11 | Chen et al.,41 China | Cost-effectiveness of reimbursing infliximab for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease in China |

| ICER of reimbursing IFX v. not reimbursing IFX = ¥42,198/QALY gained | ||

| 12 | de Groof et al.,42 Netherlands | Cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic ileocecal resection versus infliximab treatment of terminal ileitis in Crohn’s disease: the LIR!C trial |

| ICER of laparoscopic resection v. IFX (QALYs): €−85, 802/QALY; laparoscopic ileocecal resection was dominant | ||

| 13 | Hernandez et al.,43 Japan | Cost-effectiveness analysis of vedolizumab compared with other biologics in anti-TNF-naive patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in Japan |

| ICER of VEDO v. IFX = ¥4,687,692/QALY gained ICER of VEDO v. ADA = ¥4,821,940/QALY gained | ||

| 14 | Hughes et al.,44 Canada | Cost-utility analysis of switching from reference to biosimilar infliximab compared to maintaining reference infliximab in adult patients with Crohn’s disease. |

| Switching to bsIFX was less costly with incremental savings of CAD $46,194 and loss in QALYs of −0.13. | ||

| 15 | Jaisson-Hot et al.,45 France | Management for severe Crohn’s disease: a lifetime cost-utility analysis. |

| ICER of IFX episodic retreatment v. conventional therapy = €63,700.82/QALY gained; ICER of IFX maintenance infusions every 8 wk v. conventional therapy = €784,057.49/QALY | ||

| 16 | Kaplan et al.,46 United States | Infliximab dose escalation v. initiation of adalimumab for loss of response in Crohn’s disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis |

| ICER of IFX dose escalation v. ADA = US $332,032/QALY gained | ||

| 17 | Marchetti et al.,47 Italy | Cost-effectiveness analysis of top-down versus step-up strategies in patients with newly diagnosed active luminal Crohn’s disease |

| Top down IFX v. step-up IFX was dominant and had a cost savings of €773 and increased 0.14 QALYs | ||

| 18 | Moradi et al.,48 Iran | Economic evaluation of infliximab for treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis in Iran: cost-effectiveness analysis |

| ICER of IFX v. conventional treatment = US $240,903/QALY gained | ||

| 19 | Park et al.,49 United States | Cost-effectiveness analysis of adjunct VSL# 3 therapy versus standard medical therapy in pediatric ulcerative colitis |

| ICER of standard care + VSL #3 v. standard therapy = US $79,910/QALY gained | ||

| 20 | Park et al.,50 United States | Cost-effectiveness of early colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis versus standard medical therapy in severe ulcerative colitis |

| ICER of standard therapy + IPAA v. standard therapy = US $1,476,783/QALY gained | ||

| 21 | Rencz et al.,51 Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom | Cost-utility of biological treatment sequences for luminal Crohn’s disease in Europe |

| ICER of bsIFX v. standard care: Belgium = €37,545/QALY gained;

France = €42,951/QALY gained; Germany = €72,147/QALY gained;

Hungary = €34,580/QALY gained; Italy = €43,277/QALY gained;

Netherlands = €58,912/QALY gained; Spain = €54,603/QALY gained;

Sweden = €77,062/QALY gained; UK = €65,548/QALY

gained ICER of IFX v. standard care: Belgium = €37,545/QALY gained; France = €42,951/QALY gained; Germany = €94,847/QALY gained; Hungary = €48,931/QALY gained; Italy = €57,267/QALY gained; Netherlands = €58,912/QALY gained; Spain = €64,943/QALY gained; Sweden = €87,118/QALY gained; UK = €71,353/QALY gained ICER of bsIFX + ADA v. bsIFX: Belgium = €76,385/QALY gained; France = €70,277/QALY gained; Germany = €162,069/QALY gained; Hungary = €79,360/QALY gained; Italy = €88,677/QALY gained; Netherlands = €92,260/QALY gained; Spain = €94,178/QALY gained; Sweden = €99,469/QALY gained; UK = €72,782/QALY gained ICER of bsIFX + VEDO v. bsIFX: Belgium = €183,963/QALY gained; France = €246,540/QALY gained; Germany = €257,969/QALY gained; Hungary = €256,937/QALY gained; Italy = €189,943/QALY gained; Netherlands = €179,875/QALY gained; Spain = €313,944/QALY gained; Sweden = €233,356/QALY gained; UK = €263,643/QALY gained bsIFX + ADA + VEDO v. bsIFX + ADA: Belgium = €212,182/QALY gained; France = €284,985/QALY gained; Germany = €298,431/QALY gained; Hungary = €296,376/QALY gained; Italy = €220,096/QALY gained; Netherlands = €206,266/QALY gained; Spain = €363,232/QALY gained; Sweden = €271,323/QALY gained; UK = €305,393/QALY gained Other treatment sequences also reported | ||

| 22 | Taleban et al.,52 United States | Colectomy with permanent end ileostomy is more cost-effective than ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for Crohn’s colitis |

| ICER of IPAA v. permanent end ileostomy = US $70,715/QALY gained | ||

| 23 | Tang et al.,53 United States | Cost-utility analysis of biologic treatments for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease |

| IFX was dominant strategy compared with ADA, CERT, and NAT; cost of IFX = US $22,663 and effectiveness of IFX = 0.796 QALY gained; ICER not reported | ||

| 24 | Trigo-Vicente et al.,54 Spain | Cost-effectiveness analysis of infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, vedolizumab and tofacitinib for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in Spain |

| ICER of bsIFX v. ADA = €43,928.07/QALY; bsIFX v. GOL = €31,340.69/QALY; bsIFX v. VEDO = €122, 890/QALY; bsIFX v. TOFAC = €270,503.19 | ||

| 25 | Trigo-Vicente et al.,55 Spain | Cost-effectiveness analysis of infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and vedolizumab for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in Spain |

| ICER of IFX v. ADA = €45,582/QALY; ADA v. GOL = €2,175,992; ADA v. VEDO = €90,532 | ||

| 26 | Ung et al.,56 Canada | Real-life treatment paradigms show infliximab is cost-effective for management of ulcerative colitis |

| ICER of IFX v. ongoing steroid medical therapy = US $71,000/QALY gained at 5 y; IFX dose escalation v. ongoing medical therapy = US $114,000 to US $306,000/QALY gained at 5 y | ||

| 27 | Vasudevan et al.,57 United States | Cost-effectiveness of initial immunomodulators or infliximab using modern optimization strategies for Crohn’s disease in the biosimilar era |

| ICER for IFX + AZA v. AZA = US $511,384/QALY gained; ICER for IFX v. AZA = US $1,102,946/QALY | ||

| 28 | Velayos et al.,58 United States | A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab |

| Testing strategy dominant compared with empiric dose escalation; testing strategy cost = US $31,870 with 0.801 QALYs; empiric dose escalation cost = US $37,266 with 0.800 QALYs | ||

| 29 | Yen et al.,59 United States | Cost-effectiveness of 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis |

| ICER of maintenance 5-ASA with option of treatment escalation v. no maintenance 5-ASA and 5-ASA for flare with option of treatment escalation = US $224,000/QALY gained | ||

| 30 | Yokomizo et al.,60 United States | Cost-effectiveness of adalimumab, infliximab or vedolizumab as first-line biological therapy in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. |

| Cost of IFX = US $99,171/mucosal healing achieved; cost ADA = US $316,378/mucosal healing achieved; cost VEDO = US $301,969/mucosal healing achieved; ICER of 10 mg/kg IFX = ICER: US $1,243, 310/additional mucosal healing achieved | ||

| 31 | Yu et al.,61 United States | Cost utility of adalimumab versus infliximab maintenance therapies in the United States for moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease |

| ADA was dominant; ADA greater QALYs = 0.014 compared with IFX; ADA less cost = US −$4,852 compared with IFX |

5-ASA, 5–aminosalicylic acid; 6MP, 6-mercaptopurine; ADA, adalimumab; AZA, azathioprine; bsIFX, biosimilar infliximab; CERT, certolizumab pegol; GOL, golimumab; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; IFX, infliximab; INHB, incremental net health benefit; IPAA, early colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; MET, metronidazole; NAT, natalizumab; NMB, net monetary benefit; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; TOFAC, tofacitinib; UK, United Kingdom; UST, ustekinumab; VEDO, vedolizumab.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies and Parameters Examined

| Parameter Examined | Number of Studies | % |

|---|---|---|

| Comparators | ||

| Treatment combinations | 17 | 54.8 |

| Treatment sequences | 4 | 12.9 |

| Treatment timing | 4 | 12.9 |

| Treatment outcomes | 2 | 6.5 |

| Postsurgical treatment strategies | 2 | 6.5 |

| Treatment switching | 1 | 3.2 |

| Reimbursement strategies | 1 | 3.2 |

| Analytic technique | ||

| CUA | 28 | 90.3 |

| CEA | 2 | 6.5 |

| Risk-benefit analysis | 1 | 3.2 |

| Type of IBD | ||

| CD | 22 | 71.0 |

| UC | 9 | 29.0 |

| Type of IFX examined | ||

| Originator | 25 | 80.6 |

| Biosimilar | 2 | 6.5 |

| Both | 4 | 12.9 |

| Time horizon, y | ||

| 1 | 9 | 29.0 |

| 2–3 | 4 | 12.9 |

| 5 | 8 | 25.8 |

| 10 | 3 | 9.7 |

| Lifetime | 8 | 25.8 |

| Perspective | ||

| Third-party payer | 14 | 45.2 |

| Public payer | 13 | 41.9 |

| Societal | 6 | 19.4 |

| Study sponsor | ||

| Public | 15 | 48.4 |

| Private | 7 | 22.6 |

| Unspecified | 9 | 29.0 |

| Adherence to Drummond checklist | ||

| All 10 | 22 | 71.0 |

| 9 of 10 | 8 | 25.8 |

| 8 of 10 | 1 | 3.2 |

CD, Crohn’s disease; CEA, cost-effectiveness analysis; CUA, cost-utility analysis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IFX, UC, ulcerative colitis.

Of 31 economic evaluations included, 22 studies (71%) were conducted in CD and 9 (29%) in UC. Twenty-eight studies (90%) were cost-utility analyses, 2 (6%) were cost-effectiveness analyses, and 1 study was classified as a risk-benefit assessment but included a 1-way sensitivity analysis on infliximab price. Twenty-five studies (81%) used originator infliximab, 2 (6%) used biosimilar infliximab, and 4 (13%) used originator and biosimilar infliximab. Seventeen studies (55%) compared treatment combinations, 4 (13%) compared treatment sequences, 4 (13%) compared treatment timing, 2 (6.5%) compared treatment outcomes, 2 (6.5%) compared postsurgical treatment strategies, 1 (3.2%) compared treatment switching, and 1 (3.2%) study compared reimbursement strategies. The papers described studies from publication years of 2001 to 2020 with a 1-y to lifetime time horizons. Thirty studies (96.8%) met 9 or 10 Drummond criteria, indicating a large proportion of high-quality economic evaluations. Fifteen studies (48%) listed public sources of funding, 7 (23%) were funded by private sources, and 9 (29%) did not specify their funding source.

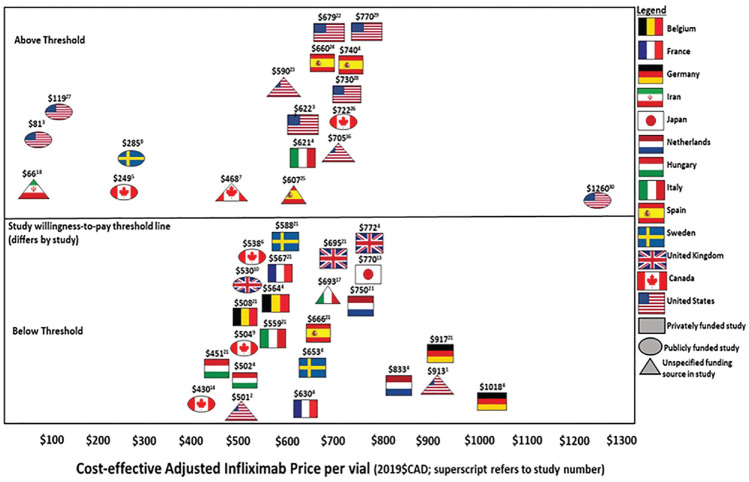

Table 3 outlines the main findings, jurisdiction, whether the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was reported as above or below the paper’s listed WTP threshold, the base price of infliximab in the article’s local currency, each study’s cost-effective price of infliximab, the range studied in sensitivity analysis, and the effects of 1-way sensitivity analyses on the ICER. The reference case price for infliximab ranged from CAD $501 to CAD $1,355 per 100-mg vial in the various studies and jurisdictions. The infliximab price deemed to be cost-effective within each study ranged from CAD $66 to CAD $1,260 per 100-mg vial. A total of 18 studies (58%) demonstrated an ICER above the jurisdictional WTP threshold (Figure 2). Nine of these were conducted in the United States. Of the 15 publicly funded studies, 8 reported an ICER above and 7 reported an ICER below the study’s chosen WTP threshold. Of the 7 privately funded studies, 5 reported an ICER above and 2 reported an ICER below the listed WTP threshold. Out of the 9 studies with unreported funding, 5 reported an ICER above and 4 reported an ICER below the designated WTP threshold.

Table 3.

Summary of Infliximab Price Sensitivity Analyses

| Author, Country | Above or below Authors’ Stated WTP Threshold | IFX Base Price (in Article Currency); (2019 CAD $) | IFX Cost-Effective Base Price per 100-mg Vial (2019 CAD $) | Range Tested in Sensitivity Analysis | Sensitivity Analysis Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliyev et al.,31 United States | Below $150,000/QALY WTP threshold | US $656/vial (2017 dollars) ($858) | $912.71 | US $657–920/vial (±20%) | At US $920 above, ADA is the treatment with the highest NMB |

| Ananthakrishnan et al.,32 United States | Below $50,000/QALY WTP threshold | Infliximab bundled drug costs (5 mg/kg dose) US

$2,634 ($2,640); price per vial not able to be determined |

$501.16 | Costs of infliximab tested: 1) US $1,000 (US $500/vial) 2) $2,000 3) $3,000 4) $4,000 |

ICER when IFX costs $1,000 = $13,268 |

| Arseneau et al.,33 United States | Below only if society is willing to pay $350,000/QALY | Bundled cost per 5-mg/kg dose; US $2,030 ($1,999); single dose ($3,236); if assumed approximately 4 vials per dose ($810) | $80.98 | Threshold analysis | Cost effective at =85% Reduction in cost (US $304) Intervention 1: US $96,550 Intervention 2: US $54,050 Intervention 3: US $127,200 |

| Baji et al.,34 Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Netherlands, United Kingdom | Use of biosimilar IFX reduces ICER below the 2× GDP per capita

WTP threshold in all 9 countries; 2× GDP per capita (in 2015

current prices in national currency and in US $) Belgium: €72,725 (US $80,913) France: €67,821 (US $75,457) Germany: €74,183 (US $82,535) Hungary: HUF 6,838,832 (US $24,041) Italy: €53,654 (US $59,695) Netherlands: €79,694 (US $88,666) Spain: €47,326, (US $52,654) Sweden: SEK 828,415 (US $97,932) UK: £57,175 (US $88,236) |

Originator: Belgium: €389 ($564) France: €434 ($630) Germany: €934 ($1,355) Hungary: €492 ($714) Italy: €571 ($828) Netherlands: €574 ($833) Spain: €616 ($894) Sweden: €553 ($802) UK: €591 ($858) Biosimilar (100 mg) Belgium: €389 ($564) France: €434 ($630) Germany: €702 ($1,018) Hungary: €346 ($502) Italy: €428 ($621) Netherlands: €574 ($833) Spain: €510 ($740) Sweden: €450 ($653) UK: €532 ($772) (2015 Euros) |

Base price of bsIFX cost-effective in all countries; $502.06

(Hungary price assumed to be the lowest cost of all countries

assessed to be deemed cost-effective Belgium: $564 France: $630 Germany: $1,018 Hungary: $502 Italy: $621 Netherlands: $833 Spain: $740 Sweden: $653 UK: $772 |

30% decrease in IFX and bsIFX price | ICER of IFX v. standard care: Belgium: €27,141 France: €30,807 Germany: €67,762 Hungary: €34,585 Italy: €41,228 Netherlands: €42,558 Spain: €46,575 Sweden: €63,206 UK: €52,137 ICER of bsIFX v. standard care: Belgium: €27,141 France: €30,807 Germany: €51,670 Hungary: €24,364 Italy: €31,319 Netherlands: €42,558 Spain: €39,245 Sweden: €56,086 UK: €48,017 (see Baji et al. for additional results) |

| Bashir et al.,35 Canada | WTP unknown Above if WTP threshold was $2,500/wk in steroid-free remission; below if WTP threshold was $3,500/wk in steroid-free remission |

$988 (2017); ($995) | $248.71 | Varying price of infliximab: 150%, 50%, 37.5%, 25% of IFX | Reducing to 37.5%: ICER $143/wk in steroid-free

remission Reducing to 25%: resulted in savings of CAD $372 in steroid-free remission |

| Beilman et al.,36 Canada | Below $50,000/QALY WTP threshold | Price per vial not reported; however, formulary price was $963 (2014) | $537.70 | Lower and upper ends of 95% CI for costs and subanalysis with biosimilar cost | One-way IFX costs: When the cost of active disease was varied between its 95% CI, the NMB ranged from −$123,515 to $56,811 for early initiation and from −$219,569 to −$19,697 for late initiation. When the cost of remission was varied between its 95% CI, the NMB ranged from −$57,044 to $13,863 for early initiation and from −$133,777 to −$77,822 for late initiation Biosimilar: Lifetime cost savings (early v. late): $40,645 QALY: 0.67 NMB: Early: $133,882 Late: $59,575 |

| Blackhouse et al.,37 Canada | Above common WTP thresholds but below if WTP = $208,000/QALY | $952/vial (2010); ($926) | $468.17 | 1) 50% reduction in unit drug costs 2) 50% increase in unit drug costs |

IFX v. ADA: ICER = 1) $212,970 2) 689,774 IFX v. usual care: ICER = 1) $100,807 2) $345,105 |

| Bolin et al.,38 Sweden | Above if using informal Swedish WTP threshold of SEK 50,000/QALY (€49,020/QALY) | Price per vial was not able to be determined; however, monthly pharmaceutical treatment costs were estimated to be SEK 483 IFX per 8 wk (2017) | $285.45 | ±10% of cost | The IFX threshold price threshold for combination therapy to be cost-effective = SEK 192/100 mg |

| Candia et al.,39 Canada | Below, if assuming $50,000/QALY WTP threshold for thiopurines postsurgery plus endoscopy-guided biological step-up therapy | Price per vial not able to be determined Bundled costs for infliximab (induction first 2 mo): $5,772 (±735) and monthly maintenance: $1,924 (±245) (2014) |

$503.90 | Decrease of up to 75% in cost of biologics | Sensitivity threshold is less than 44% of the original cost, and an alternative strategy is combination therapy immediately postsurgery |

| Catt et al.,40 United Kingdom | Dominant for £30,000/QALY | IFX £420/vial (2018); ($740); bsIFX £378/vial (2018); ($666) | $530.33 | 1) 50%–100% of originator IFX price: £189 to £420/vial 2) A 2-way sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the interaction between the development of antibodies to IFX and the price differential between the 2 drugs 3) Scenario analyses: originator IFX price drops by 25% |

1) INHB varied from 0.000 to 0.2 with tested range 2) bsIFX remained the preferred option provided it is priced below £410 per vial Even in a worst-case scenario of all patients developing antibodies to IFX, a vial of bsIFX could be priced up to £395, and it would remain the treatment of choice with a positive INHB 3) bsIFX is associated with a positive INHB across the scenarios tested, with the exception of scenario 1, where the price of originator iFX is reduced by 25% |

| Chen et al.,41 China | Below if WTP threshold = 2018 China GDP per capita = ¥64,644 (US $9,769) | Price per vial not determinable; bundled costs for the annual treatment acquisition associated with infliximab for induction therapy, first-year maintenance therapy, and maintenance therapy beyond the first year were ¥49,000, ¥39,200, and ¥29,400, respectively (2018 Chinese ¥) | Price per vial not determinable | Each model variable was changed within its 95% CI or ±25% of its baseline value on the ICER | Increasing the price of IFX increased the ICER of reimbursing IFX to ¥110,223 |

| de Groof et al.,42 Netherlands | Dominant assuming UK threshold £20, 000–30,000/QALY (€22,756–€38,028/QALY) | €369/vial (2014); ($CAD 600) | Price per vial not determinable | 1) Costs of originator IFX were lowered to bsIFX price, but

exact price was not reported; total bundled costs were:

€17,543 for an average single infusion |

ICER: £18,948/QALY The break-even point in societal costs at which biosimilars would become rapidly more expensive than resection was reached at approximately 14 mo after the start of treatment with the biosimilar |

| Hernandez et al.,43 Japan | Below ¥5,000,000/QALY WTP threshold | ¥80,426/vial (2018); $962 | $769.76 | ±20% | Lower bound, with a decrease of 20% in IFX cost reduced ICER to ¥3,09,66,856 |

| Hughes et al.,44 Canada | Below $50,000/QALY WTP threshold | IFX CAD $995/vial; bsIFX $525 (2018) | $429.96 | $795.95 (20% discount on originator IFX to $279.07; 72% discount on IFX) | With 20% discount: incremental cost = −$30,011; incremental

effect = −0.13 With 72% discount: incremental cost = −$61,245; incremental effect = −0.13 |

| Jaisson-Hot et al.,45 France | Assuming WTP threshold range of $50,000 to $100,000/QALY (€56,085 to €112,170/QALY); option 1 falls within this range, whereas option 2 is above | Price not determinable (2003 Euros) | Price not determinable | Details not provided | Variation in the cost of infliximab infusion did not lead to a change in model findings |

| Kaplan et al.,46 United States | Above $80,000/QALY | Price per vial not determinable; bundled average cost: US $4,639 (2006); range: US $2,498–$7,749 |

$705.46 | One-way SA: IFX (10 mg/kg) dosing costs: $2,498, $2,846, $3,055,

$3,220, $4,832, $7,749 Two-way SA on cost of IFX and cost of ADA where values were varied from $ 0 to the 2006 average wholesale price |

$2,498 (strategy in which ICERs were equivalent):

dominant $2,846: ICER = $49,962/QALY $3,055: ICER = $79,977/QALY $3,220: ICER = $103,587QALY $4,832: ICER = $333,032/QALY $7,749: ICER = $754,099/QALY Two-way SA: If the price of ADA was doubled, the ICER approached $100,000/QALY, and the IFX strategy was dominant; when the estimated cost of infliximab was reduced by one-third, and when the value was halved, the infliximab dose-escalating strategy was dominant |

| Marchetti et al.,47 Italy | Below €20,000/QALY WTP threshold | IFX 100 mg: €512 (2012); (CAD $693) | $692.60 | 1) €700/vial 2) €1,000/vial |

1) ICUR = €1,214/QALY 2) ICUR = €12,114/QALY Top-down strategy would not be cost saving if IFX cost no more than €666 per vial |

| Moradi et al.,48 Iran | Above 3× GDP per capita of Iran in 2014 (US $5,586/QALY) WTP threshold | US $587/vial (2014); ($664) | $66.45 | Up to 90% reduction in price of IFX | Cost is the most important factor affecting the ICER; up to 90% decrease in price brings ICER in below the 3× GDP threshold |

| Park et al.,49 United States | Above $50,000 to $100,000/QALY WTP threshold | Price per vial not determinable; bundled costs were US $28,947 for 3 induction infusions and US $57,894 per year for 6 maintenance infusions (2009) | Price per vial not determinable | Bundled costs $14,474−$57,894 (induction); $14,474−$115,788 (maintenance) | QoL after colectomy was the most sensitive parameter; cost of IFX did not significantly affect outcomes |

| Park et al.,50 United States | Above US $50,000/QALY WTP threshold | Price per vial not determinable; bundled costs were US $28,947 for induction infusions and US $4,825/month for maintenance (2009) | Price not determinable | $14,474−$57,894 (induction per month); $2,412−$9,649 (maintenance per month) | The utility of stable health after colectomy + IPAA was the most sensitive parameter; ICER was not sensitive to IFX cost |

| Rencz et al.,51 Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom | For bsIFX ICERs below threshold of 2 to 3× GDP (in 2015 current

prices in national currency and in US $) Belgium: €72,725 (US $80,913) to €109,088 (US $121,369) France: €67,821 (US $75,457) to €101,732 (US $113,185) Germany: €74,183 (US $82,535) to €111,275 (US $123,802) Hungary: HUF 6,838,832 (US $24,041) to HUF 10,258,248 (US $36,062) Italy: €53,654, (US $59,695) to €80,482 (US $89,542) Netherlands: €79,694 (US $88,666) to €119,541 (US $132,999) Spain: €47,326 (US $52,654) to €70,989 (US $78,981) Sweden: SEK 828,415 (US $97,932) to SEK 1,242,623 (US $146,898) UK: £57,175 (US $88,236) to £85,762 (US $132,353) |

Originator: Belgium: 389 ($564) France: 434 ($630) Germany: 934 ($1,355) Hungary: 492 ($714) Italy: 571 ($828) Netherlands: 574 ($833) Spain: 616 ($894) Sweden: 553 ($802) UK: 591 ($858) Biosimilar (100 mg) Belgium: 389 ($564) France: 434 ($630) Germany: 702 ($1,018) Hungary: 346 ($501) Italy: 428.01 ($621) Netherlands: 573.99 ($833) Spain: 510.29 ($740) Sweden: 450.29 ($653) UK: 531.92 ($772) |

Belgium = $507.84; Hungary = $451.20; Italy = $558.96; France = $567.31; Sweden = $588.05; Spain = $666.41; UK = $694.66; Netherlands = $749.60; Germany = $916.59 | ±10% on price of biologics | Only moderate effect on ICER when price changed by ±10% |

| Taleban et al.,52 United States | Above $50,000/QALY WTP threshold | Price per vial not determinable; bundled costs were US $15,144 for 6 mo (2014) | $678.71 | US $2,354–$4,871 for 500 mg of IFX | IFX cost was the second most sensitive variable in the 1-way SA |

| Tang et al.,53 United States | Above if $100,000/QALY WTP threshold, but relative comparisons among strategies | US $736 (2011); ($738) | $590.36 | US $589–$920/vial (approximately ±25% of price) | IFX cost is the fifth most sensitive variable in the 1-way SA |

| Trigo-Vicente et al.,54 Spain | Above €30,000/QALY WTP threshold | €423 (2018); ($660) | $659.67 | ±20% price per vial (€338–€508/vial) | ICER was not sensitive to price |

| Trigo-Vicente et al.,55 Spain | Above €30,000/QALY WTP threshold | €558 EU (2017); ($823) | $606.73 | ±20% price per vial | A 10% discount in the price of bsIFX affected could be cost-effective compared with ADA and GOL |

| Ung et al.,56 Canada | Above or below depending on comparator with US $80,000/QALY WTP threshold | CAD $963; ($963) | $722.01 | ±25% of price | Cost was the most sensitive variable |

| Vasudevan et al.,57 United States | Above US $100,000/QALY WTP threshold | bsIFX: US $904 (2018); ($1,194) | $119.36 | 10% of current cost ($90.40/100 mg) | IFX + AZA: ICER = $161,643/QALY; IFX v. AZA: ICER = greater than $500,000/QALY; with 5-y extended time horizon, IFX + AZA: ICER = $109,385/QALY |

| Velayos et al.,58 United States | Above US $50,000 to $100,000/QALY WTP threshold | US $756 (2010); ($730) | $730.48 | $3,780/unit dose | Test-based strategy still dominant but with greater cost savings |

| Yen et al.,59 United States | Above US $50,000 to $100,000/QALY WTP threshold | US $927 charged; US $583 paid (2004); ($1,222) | $769.94 | Cost of IFX US $1,520−$2,720/mo | IFX cost had a minimal impact on the result since it was used very downstream; most sensitive variables in SA were the relative risk of a flare on maintenance 5-ASA and the cost of 5-ASA |

| Yokomizo et al.,60 United States | Above US $50,000 to $100,000/mucosal healing achieved WTP threshold | US $1,114 (2014); ($1,260) | $1,260.14 | US $500−$1,500/vial | Cost of ADA and VEDO were the primary cost drivers; infusion cost for IFX was the most sensitive variable; base price was assumed to be cost-effective |

| Yu et al.,61 United States | Above US $50,000 to $100,000 WTP threshold but still considered cost-effective | US $581 (2007); ($622) | $621.93 | IFX wastage was tested in SA; IFX price not tested | Excess unused drug reduced incremental costs; base price assumed to be cost-effective |

| Meana (s) | 792.18 (206.28) | 555.61 (261.93) | |||

| Mediana (IQR) | 756.15 (254.36) | 564.03 (263.71) | |||

| Minimum | 501.34 | 66.45 | |||

| Maximum | 1,355.28 | 1,260.14 | |||

| Meanb (s) | 792.18 (206.28) | 607.79 (231.40) | |||

| Medianb (IQR) | 756.15 (254.36) | 621.49 (229.43) | |||

| Minimum | 501.34 | 66.45 | |||

| Maximum | 1,355.28 | 1,260.14 |

5-ASA, 5–aminosalicylic acid; ADA, adalimumab; AZA, azathioprine; bsIFX, biosimilar infliximab; CI, confidence interval; GDP, gross domestic product; GOL, golimumab; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ICUR, incremental cost-utility ratio; IFX, originator infliximab; INHB, incremental net health benefit; IPAA, early colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; IQR, interquartile ratio; NMB, net monetary benefit; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; QoL, quality of life; SA, sensitivity analysis; VEDO, vedolizumab; WTP, willingness-to-pay.

Mean and median per study was determined. For Baji et al. and Rencz et al., the lowest cost in Europe was included for the mean and median costs shown.

Mean and median for each country is reported.

Figure 2.

Cost-effective base price of a 100-mg vial of infliximab determined in each study to 2019 Canadian dollars. Bold numbers above each study flag represent the cost-effective adjusted infliximab price per vial. Studies below the midline were considered below the willingness-to-pay threshold, and studies above the line were considered above the willingness-to-pay threshold. Ovals represent publicly funded studies, and rectangles represent privately funded studies. Triangles represent studies with an unspecified funding source.

Discussion

To provide insight into how the high cost of originator infliximab may be prompting policies to enable access to less costly biosimilars, the present review examined the impact of infliximab price on cost-effectiveness studies in IBD. Infliximab price was examined in sensitivity analysis in only 21% of studies. Infliximab showed favorable cost-effectiveness at a price ranging from CAD $66 to $1,260 per vial depending on the jurisdiction. Internationally, the mean price deemed cost-effective based on reported WTP thresholds was CAD $608 (s = $231) per vial. Important considerations related to overall cost-effectiveness of infliximab in IBD, policy development, pricing strategies, and access are discussed in detail below.

Economic Evaluations of Infliximab

Since the introduction of infliximab its cost has been significantly greater than other IBD treatments such as corticosteroids and immunomodulators putting pressure on public and private drug plans. Numerous cost-effectiveness analyses of infliximab have been conducted, but only 21% examined price in a 1-way sensitivity analysis. Other reviews of economic evaluations in IBD have been conducted; however, they focused on cost-effectiveness of treatment outcomes. Tang et al.62 reviewed 38 economic evaluations and costing studies in which different scenarios with biologics were evaluated for the treatment of CD. They concluded that infliximab and adalimumab were cost-effective compared with standard therapy for luminal CD when provided as an induction therapy followed by episodic therapy over 5 or more years using a WTP threshold of US $100,000/QALY.62 Lachaine et al.63 evaluated 48 studies using various treatment strategies including biologics, mesalamine, immunosuppressants, and surgery for UC and CD and concluded that biological therapies were dominant in 23% of the analyses and were cost-effective in 41% in the studies at a CAD $50,000/QALY WTP threshold and were cost-effective in 62% of the studies at a CAD $100,000/QALY threshold. Pillai et al.64 examined 49 articles that included pharmacologic and surgical interventions for adults with UC and CD. They converted costs and ICERs to reflect 2015 purchasing power parity (PPP). Infliximab and adalimumab induction and maintenance treatments were cost-effective compared with standard care in patients with moderate or severe CD, but in patients with conventional drug-refractory CD, fistulizing CD and for maintenance of surgically induced remission, biologic ICERs were above jurisdictional cost-effectiveness thresholds (above 100,000 PPP/QALY). They concluded that while biologic agents helped improve outcomes, they were not cost-effective, owing to their high cost, particularly for use as maintenance therapy.64 Huoponen and Blom65 reviewed 25 economic evaluations in IBD and assessed each study’s methodological quality based on the CHEERS guidelines. Following conversion of results to 2014 euros, Huoponen and Blom65 concluded that in patients refractory to conventional medical treatment, the ICER of biologics ranged from dominance to €549,335/QALY when compared with conventional medical treatment. They also concluded that biologics seemed to be cost-effective at a WTP threshold of €35,000/QALY when used for the induction phase of active and severe IBD.65 Similar to other reviews, Marchetti and Liberato66 acknowledged that the cost of biological treatments and the variability in the manifestation of disease influence the cost-effectiveness of these treatments. They also stated that biologics appear to be cost-effective for the induction phase of treatment IBD. Smart and Selinger67 acknowledged the costliness of infliximab and stated that determining cost-effectiveness in CD was challenging due to the heterogeneity in treatment strategies, time horizons, costs, and patient populations. However, based on UK WTP thresholds of £50,000 for nonfistulating CD and £100,000/QALY for fistulating disease, infliximab could be deemed cost-effective for the treatment of moderate-to-severe CD when the disease is not limited to the terminal ileum.67 To date, reviews of cost-effectiveness studies with biologics for IBD have underscored the costliness of biologic treatment as a whole and the heterogeneity of the cost-effectiveness study results. Nevertheless, the reviews have concluded that biologics seem to be cost-effective in the induction treatment of refractory moderate-to-severe disease. Private or public study sponsorship did not seem to affect whether the ICER was above or below a WTP threshold as most studies had ICERs above a WTP threshold regardless of sponsorship source. While these studies support the use of biologics in the treatment of IBD, no review has thus far examined the sensitivity of infliximab price on the results of economic evaluations.

Considerations in Infliximab and Biologic Treatment Policy

Owing to the high cost of originator infliximab and policies favoring biosimilar infliximab implemented in some Canadian provinces and elsewhere, concerns remain regarding whether originator infliximab will be easily accessible to patients who have managed well and prefer it. Further, trying to maintain their patients on originator infliximab may add to physicians’ administrative burden. It remains uncertain how access to originator infliximab will evolve and be influenced by public health directives, such as those pertaining to COVID-19, that have disrupted implementing some forced switch policies.68 There have been reports that the originator infliximab manufacturer did offer to reduce its price to provincial governments in closed-door meetings and provide incentives to infusion clinics.69–71 However, a reduced price for originator infliximab has not yet appeared in Canadian provincial formularies.

The Complexity of Pricing in Biologics

While this review focused on the cost-effectiveness of infliximab in IBD, access and pricing issues are relevant to informing biologic treatment policies in many jurisdictions worldwide as new biosimilar and new originator biologics enter the market for multiple indications and as biologics come off patent. The patents on Remicade expired in Europe in February 2015, and in Canada, biosimilar competition entered the market starting in 2014–2015.72,73 In Europe, the entrance of biosimilars increased price competition and affected the price of both the originator product and the price of the product class in certain markets.74 However, the impact varies by market as well as therapeutic area. With the introduction of biosimilar infliximab, the prices of originator infliximab decreased in France, the United Kingdom, and Germany, for example.75 In Canada, the annual treatment costs in public plans for Remicade continued to increase after 2015 despite the availability of biosimilars.76,77

In Canada, achieving a balance between sustainable health care costs, fair access to the Canadian market for market entrants, and equitable access for patients is a challenge. The present analysis indicated that the mean cost-effective price across 26 studies, albeit with different study designs and comparators, was CAD $608 (s = CAD $231), which is close to the current average price of biosimilar infliximab in Canada at CAD $528 per vial and much lower than the current median price of CAD $986 for originator infliximab.11 Manufacturers’ strategies for lowering brand name drug prices depend on many factors that include global marketing strategy, Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) regulatory oversight, pricing negotiations by the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance, provincial drug plan requirements, as well as patent expiration and market competition. Pricing strategies may vary by province depending on these factors as well as the provincial biologics access polices. Proposed changes to PMPRB guidelines include consideration of a new medicine’s pharmacoeconomic value in Canada, the medicine’s Canadian market size, the medicine’s price in other markets, and the Canadian GDP per capita.2 Such regulatory oversight may also prevent manufacturers from raising prices to just under known WTP thresholds, although it is unknown to what extent this occurs. Considering the effort required by originator manufacturers to achieve product listing and considering the relatively small size of the Canadian market, policies that challenge competition may discourage manufacturers from launching in Canada, ultimately preventing Canadian patients access to new treatments.

To maintain access to originator infliximab for patients and physicians given concerns with forced switching, international payers and suppliers may want to consider various pricing strategies. These strategies have been summarized by Comer78 and include financial risk-based contracts, health outcomes–based contracts, mortgage models, subscription models, and indication-specific pricing.

Access to Treatment

Some biologic treatments such as infliximab are administered by infusion in private clinics with an ongoing patient support program. The patient support program often includes navigating through the complex drug coverage process, scheduling of appointments, nursing support, and ongoing pharmacovigilance. The cost of patient support programs is absorbed by the manufacturer, but the convenience of the support programs is realized by the patient. While biosimilar switch policies help to reduce the public payer costs and facilitate the adoption of new treatments, treatment switch policies should also consider the potential inconvenience to patients if they must also switch their routine and location of where to access their treatment. Patient support programs have had a positive effect on patient treatment adherence based on a study sponsored by Abbvie, the manufacturer for originator adalimumab.79 Whether patient treatment adherence remains unaffected or whether long-term real-world evidence collected by patient support programs is compromised remains to be seen. Furthermore, differences in eligibility for access to originator infliximab that arise between public and private drug plans will create inequities between those patients who can access originator infliximab through private plans compared with those restricted to using public plans.

Strengths and Limitations

Unlike previous reviews of economic evaluations examining biologics in IBD, the present review comprehensively examined the impact of the price of infliximab—a key input into determining cost-effectiveness—on the results of economic evaluations. In addition, this review examined infliximab use as monotherapy, as part of combination treatment, and as part of sequential treatment. Furthermore, this review used economic evaluation findings to suggest potential cost-effective price estimates for this treatment across global jurisdictions.

Despite the in-depth review, challenges were encountered in the analysis. The present review included 22 studies in CD and 9 in UC. The cost-effectiveness results were not studied separately, and it is not known to what extent individual jurisdictions require condition-specific cost-effectiveness analysis or set indication-specific prices. While the source of funding was examined, it was not possible to ascertain in all cases whether or not the sponsor was the manufacturer. While a 1-way sensitivity analysis was conducted in all included papers, the price of infliximab was sometimes bundled with other costs such as administration costs or aggregated over time such as a monthly cost. As such, determining a cost-effective price per vial was not possible in 5 studies. Future economic evaluations of biologics should ensure that all relevant costs are disaggregated when reported and that an appropriate price range is tested in sensitivity analysis. It is also recognized that domestic infliximab prices may change after study publication due to patent expiry or other factors, and this would affect inferences regarding relative cost-effectiveness. Another limitation was the large variation in stated WTP thresholds across jurisdictions. Whether a price was considered cost-effective was dependent on the threshold used as a reflection of the domestic budget constraint. Thresholds were stated at the discretion of study authors and therefore may not reflect WTP thresholds used by government agencies or drug plans in evaluating cost-effectiveness. This variation in WTP thresholds may have contributed to studies considering treatment with infliximab as cost-effective in some jurisdictions but not in others. Infliximab prices negotiated between private insurance payers and suppliers are confidential and may be less than formulary list prices. Lastly, the negotiated cost of administering infliximab through preferred infusion clinics was not publicly available.

Conclusions

Most economic evaluations in IBD examined infliximab price in sensitivity analyses. This review showed that most studies (58%) demonstrated an incremental cost-effectiveness of infliximab in IBD that exceeded their jurisdictional WTP threshold. While this review focused on cost-effectiveness of infliximab around the globe, issues concerning patient access to treatment, patient and clinician preferences for treatment, pricing strategies, and repercussions for future market entrants can inform biosimilar policies in domestic markets as more biosimilars and biologics are introduced.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mpp-10.1177_23814683231156433 for Infliximab Pricing in International Economic Evaluations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease to Inform Biologic and Biosimilar Access Policies: A Systematic Review by Naazish S. Bashir, Avery Hughes and Wendy J. Ungar in MDM Policy & Practice

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support in the form of a Hospital for Sick Children Restracomp Postdoctoral Research Fellowship awarded to Naazish S. Bashir and the Canada Research Chair in Economic Evaluation and Technology Assessment in Child Health awarded to Wendy J. Ungar. All data extracted for the purpose of this review and the analytic methods are summarized in the article and supplemental files.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided in part by a Hospital for Sick Children Restracomp Postdoctoral Research Fellowship awarded to NSB and in part by the Canada Research Chair in Economic Evaluation and Technology Assessment in Child Health awarded to WJU. The funding agreements ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

The work was conducted at Technology Assessment at Sick Kids (TASK), Program of Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Toronto, Canada. The work has been presented at the 2020 annual meetings of the Canadian Agency of Drugs, and Health Technologies and the Society of Medical Decision Making. The video presentations by Dr. Bashir are available on our research Web site here: https://lab.research.sickkids.ca/task/videos/.

ORCID iDs: Naazish S. Bashir  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-6189

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-6189

Wendy J. Ungar  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0762-0101

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0762-0101

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material for this article is available on the MDM Policy & Practice website at https://journals.sagepub.com/home/mpp.

Contributor Information

Naazish S. Bashir, Program of Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada

Avery Hughes, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Wendy J. Ungar, Program of Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada; Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

References

- 1. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2019: A Focus on Public Drug Programs. Ottawa (Canada): Canadian Institute for Health Information; ; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Biologics in Canada. Part 1: market trends, 2018. 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pmprb-cepmb/documents/reports-and-studies/chartbooks/biologics-part1-market-trends.pdf

- 3. Kaplan GG, Ma C, Seow CH, Kroeker KI, Panaccione R. The argument against a biosimilar switch policy for infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease living in Alberta. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2020;3(5):234–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murdoch B, Caulfield T. The law and ethics of switching from biologic to biosimilar in Canada. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2020;3(5):228–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blair HA, Deeks ED. Infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13; infliximab-dyyb): a review in autoimmune inflammatory diseases. BioDrugs. 2016;30(5):469–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM, Danese S, Gokhale SB, Woollett G. Switching reference medicines to biosimilars: a systematic literature review of clinical outcomes. Drugs. 2018;78(4):463–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ebada MA, Elmatboly AM, Ali AS, et al. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis about the safety and efficacy of infliximab biosimilar, CT-P13, for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019:34(10):1633–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feagan BG, Lam G, Ma C, Lichtenstein GR. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of switching patients between reference and biosimilar infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(1):31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Komaki Y, Yamada A, Komaki F, Micic D, Ido A, Sakuraba A. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agent (infliximab), in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(8):1043–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murthy SK, Begum J, Benchimol EI, et al. Introduction of anti-TNF therapy has not yielded expected declines in hospitalisation and intestinal resection rates in inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based interrupted time series study. Gut. 2020;69(2):274–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ontario Ministry of Health. Drugs and devices division. Formulary. Available from: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/odbf_mn.aspx

- 12. Government of British Columbia. Biosimilars initiative for patients: Government of British Columbia; 2020. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/health-drug-coverage/pharmacare-for-bc-residents/what-we-cover/biosimilars-initiative-patients?

- 13. Community Academic Research Education. Gastroenterology faculty analysis: biosimilars and access to innovation for gastroenterologists managing patients with IBD. Community Academic Research Education (CARE); Canada 2021. Available from: : https://careeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Gastroenterology_Needs_Assessment_Results_Biosimilars_IBD.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teshima CW, Thompson A, Dhanoa L, Dieleman LA, Fedorak RN. Long-term response rates to infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease in an outpatient cohort. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;23(5):348–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Community Academic Research Education. CARE perspectives on the NOR-SWITCH trial. Canadian Community Academic Research Education (CARE); Canada: 2017. Available from: https://careeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CAREPerspectivesonNOR-SWITCHv2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. ; NOR-SWITCH study group. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moayyedi P, Benchimol EI, Armstrong D, Yuan C, Fernandes A, Leontiadis GI. Joint Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and Crohn’s Colitis Canada position statement on biosimilars for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2020;3(1):e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. Non-medical Switch: Biosimilars. Crohn’s and Colitis Canada; Toronto, Canada. 2019. Available from: https://crohnsandcolitis.ca/Get-Involved/Advocating-for-change/Non-Medical-Switch-Biosimilars [Google Scholar]

- 19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Health Technology Review. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/health-technology-review [Google Scholar]

- 21. SickKids. Pediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) project. Toronto (Canada): Hosptial for Sick Children; 2022. Available from: http://pede.ccb.sickkids.ca/pede/index.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 22. Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk. Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health CEA Registry: Tufts University. Available from: https://cevr.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/

- 23. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. PRISMA group the PRISMA group preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 4th ed. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bank of Canada. Statistics. 2022. Available from: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/

- 26. Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index, monthly, not seasonally adjusted, table: 18-10-0004-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0020). Ottawa (Canada): Statistics Canada; 2022. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000401 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted, table: 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021). 2022. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000501

- 28. Campbell Collaboration. CCEMG-EPPI-Centre cost converter. Available from: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/

- 29. Nimdet K, Chaiyakunapruk N, Vichansavakul K, Ngorsuraches S. A systematic review of studies eliciting willingness-to-pay per quality-adjusted life year: does it justify CE threshold? PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health. 2016;19(8):929–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aliyev ER, Hay JW, Hwang C. Cost-effectiveness comparison of ustekinumab, infliximab, or adalimumab for the treatment of moderate-severe crohn’s disease in biologic-naïve patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39(2):118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ananthakrishnan AN, Korzenik JR, Hur C. Can mucosal healing be a cost-effective endpoint for biologic therapy in Crohn’s disease? A decision analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arseneau KO, Cohn SM, Cominelli F, Connors AF., Jr. Cost-utility of initial medical management for Crohn’s disease perianal fistulae. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(7):1640–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baji P, Gulácsi L, Brodszky V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of biological treatment sequences for fistulising Crohn’s disease across Europe. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(2):310–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bashir NS, Walters TD, Griffiths AM, Ito S, Ungar WJ. Cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes of early anti–tumor necrosis factor–α intervention in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(8):1239–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beilman CL, Kirwin E, Ma C, McCabe C, Fedorak RN, Halloran B. Early initiation of tumor necrosis factor antagonist–based therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease reduces costs compared with late initiation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(8):1515–24.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blackhouse G, Assasi N, Xie F, et al. Canadian cost-utility analysis of initiation and maintenance treatment with anti-TNF-α drugs for refractory Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(1):77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bolin K, Hertervig E, Louis E. The cost-effectiveness of biological therapy cycles in the management of Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(10):1323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Candia R, Naimark D, Sander B, Nguyen GC. Cost–utility analysis: thiopurines plus endoscopy-guided biological step-up therapy is the optimal management of postoperative crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(11):1930–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Catt H, Bodger K, Kirkham JJ, Hughes DA. Value assessment and quantitative benefit-risk modelling of biosimilar infliximab for Crohn’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(12):1509–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen H, Shi J, Pan Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of reimbursing infliximab for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease in china. Adv Ther. 2020;37(1):431–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Groof EJ, Stevens TW, Eshuis EJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic ileocaecal resection versus infliximab treatment of terminal ileitis in Crohn’s disease: the LIR! C Trial. Gut. 2019;68(10):1774–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hernandez L, Kuwabara H, Shah A, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of vedolizumab compared with other biologics in anti-TNF-naive patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in Japan. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(1):69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hughes A, Marshall JK, Moretti ME, Ungar WJ. A cost-utility analysis of switching from reference to biosimilar infliximab compared to maintaining reference infliximab in adult patients with crohn’s disease. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2020;4(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jaisson-Hot I, Flourié B, Descos L, Colin C. Management for severe Crohn’s disease: a lifetime cost-utility analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(3):274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaplan G, Hur C, Korzenik J, Sands B. Infliximab dose escalation vs. initiation of adalimumab for loss of response in Crohn’s disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(11–12):1509–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marchetti M, Liberato NL, Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR. Cost-effectiveness analysis of top-down versus step-up strategies in patients with newly diagnosed active luminal Crohn’s disease. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(6):853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moradi N, Tofighi S, Zanganeh M, Akbari Sari A, Khedmat H, Zarei L. Economic evaluation of infliximab for treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis in Iran: cost-effectiveness analysis. Iran J Pharm Sci. 2016;12(4):33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Park K, Perez F, Tsai R, Honkanen A, Bass D, Garber A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of adjunct VSL# 3 therapy versus standard medical therapy in pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(5):489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Park K, Tsai R, Perez F, Cipriano LE, Bass D, Garber AM. Cost-effectiveness of early colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastamosis versus standard medical therapy in severe ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2012;256(1):117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rencz F, Gulácsi L, Péntek M, et al. Cost-utility of biological treatment sequences for luminal Crohn’s disease in Europe. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(6):597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Taleban S, Van Oijen MG, Vasiliauskas EA, et al. Colectomy with permanent end ileostomy is more cost-effective than ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for Crohn’s colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(2):550–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tang DH, Armstrong EP, Lee JK. Cost-utility analysis of biologic treatments for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(6):515–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trigo-Vicente C, Gimeno-Ballester V, López-Del Val A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, vedolizumab and tofacitinib for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in Spain. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;27(6):355–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Trigo-Vicente C, Gimeno-Ballester V, Montoiro-Allué R, López-Del Val A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and vedolizumab for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in Spain. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(3):321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ung V, Thanh NX, Wong K, et al. Real-life treatment paradigms show infliximab is cost-effective for management of ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(11):1871–8.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vasudevan A, Ip F, Liew D, Van Langenberg DR. The cost-effectiveness of initial immunomodulators or infliximab using modern optimization strategies for Crohn’s disease in the biosimilar era. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(3):369–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Velayos FS, Kahn JG, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG. A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(6):654–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yen EF, Kane SV, Ladabaum U. Cost-effectiveness of 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3094–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yokomizo L, Limketkai B, Park K. Cost-effectiveness of adalimumab, infliximab or vedolizumab as first-line biological therapy in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yu AP, Johnson S, Wang S-T, et al. Cost utility of adalimumab versus infliximab maintenance therapies in the United States for moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(7):609–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]