Abstract

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is associated with long-lasting and pervasive impacts on survivors’ sexual health, particularly on their sexual satisfaction. Dispositional mindfulness has been found to be associated with greater sexual satisfaction among adult CSA survivors. However, the mechanisms involved in this association remain understudied. The present study examined the role of sexual self-concept (i.e., sexual esteem, sexual preoccupation, and sexual depression) in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction among CSA survivors. A total of 176 adult CSA survivors (60.6% women, 39.4% men) completed an online survey assessing dispositional mindfulness, sexual self-concept, and sexual satisfaction. Path analyses revealed that dispositional mindfulness was positively related to sexual satisfaction through a significant indirect effect of higher sexual esteem and lower sexual depression. The integrative model explained 66.5% of the variance in sexual satisfaction. These findings highlight the key roles that dispositional mindfulness and sexual self-concept play in CSA survivors’ sexual satisfaction. Implications for interventions based on trauma-sensitive mindfulness targeting the sexual self-concept are discussed, as they may promote sexual satisfaction in adult CSA survivors.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, sexual self-concept, mindfulness, sexual satisfaction, path analysis

Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is widely recognized as a form of trauma associated with long-lasting and pervasive impacts on survivors’ sexual satisfaction (Bigras et al., 2020). These impacts can be understood in light of the traumatic sexualization that can result from CSA. Traumatic sexualization refers to one of the four dynamics (i.e., trauma-causing factors) of the Traumagenic Dynamics Model developed by Finkelhor and Browne (1985), which postulates that the abusive context in which sexuality was introduced to a child may impair psychosexual development. Therefore, traumatic sexualization may increase the risk of suffering from a wide range of sexual sequelae later in life (e.g., using sexuality to meet emotional needs, sexual dysfunction, sexual aversion or compulsion, flashbacks, etc.). Such sexual sequelae may especially contribute to lower sexual satisfaction in adulthood (Bigras et al., 2015; Rellini et al., 2011). Sexual satisfaction refers to the subjective appreciation of the positive and negative aspects of one’s sexual relationships (Lawrance & Byers, 1995). Sexual satisfaction can occur independently from sexual function and can be a key focus in treatment (Ferenidou et al., 2008), especially in CSA survivors who may be particularly impaired in this respect. Several studies have investigated how to foster satisfying sex lives among CSA survivors (see reviews of Bigras et al., 2020; Guyon, Fernet, Canivet et al., 2020a). Mindfulness has been identified as a promising determinant of resilience in the sexual sphere (Dussault et al., 2020; Godbout et al., 2020), but empirical evidence regarding the link between mindfulness and sexual satisfaction among CSA survivors remains limited.

Dispositional Mindfulness and Sexual Satisfaction

Mindfulness has been conceptualized as receptivity and awareness of, and attention to internal and external experiences as they occur (Brown & Ryan, 2003). All individuals have the capacity to cultivate mindfulness (Baer et al., 2006), even though an individual’s mindfulness dispositions may vary in function of the levels of practice and integration throughout life. Mindfulness can be achieved through meditation, which aims to develop awareness (Kabat-Zinn, 2015). However, Langer (1989) suggests that mindfulness includes situational awareness, sensitivity to changes in the environment, and control over one’s thoughts, which are not limited simply to the context of meditation. In this sense, mindfulness can be practiced daily and can manifest as an inherent capacity or trait (i.e., dispositional mindfulness; Brown & Ryan, 2003).

Dispositional mindfulness has been associated with more adaptive sexual outcomes, such as greater sexual functioning (e.g., orgasm capacity, arousal), sexual well-being, and sexual satisfaction in community and clinical samples (e.g., Déziel et al., 2018; Godbout et al., 2020; Khaddouma et al., 2015; Newcombe & Weaver, 2016; Pepping et al., 2018). Specifically, Khaddouma et al. (2015) found that attending to and noticing internal and external stimuli was related to increased sexual satisfaction. Similarly, Pepping et al. (2018) found that the association between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction was mediated by emotional regulation. Another study investigating this link in victimized individuals found that cumulative childhood interpersonal trauma was related to lower dispositional mindfulness, which in turn led to lower sexual satisfaction (Godbout et al., 2020). The previous findings, combined with those attesting to the significant potential of mindfulness-based interventions to improve the sexual satisfaction of survivors of sexual trauma (Brotto et al., 2012; Esper & da Silva Gherardi-Donato, 2019), support the need to better understand what may link these two variables using empirical data. However, research documenting the mechanisms involved in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction are lacking.

Although studies have found that CSA can negatively affect sexual function, and in turn, sexual satisfaction (Lacelle et al., 2012), few have specifically examined the effects of CSA on sexual satisfaction from an identity perspective. Yet, CSA can profoundly disrupt survivors’ sense of self (Saha et al., 2011), which refers to one’s experience within the world in terms of a sense of individuality, unity, and continuity (Cicchetti & Beeghly, 1990), and impair sexual identity development (Bigras et al., 2015). In particular, survivors may come to see themselves as sex objects, fundamentally broken, or as bad people because of the abuse they endured; this can taint their relationship with sexuality in the longer term (Maltz, 2012). These identity and self-perception outcomes, grouped under the dimension of sexual self-concept, are associated with lower sexual satisfaction in CSA survivors (Bigras et al., 2015; Guyon et al., 2020a). Thereby, sexual self-concept could be a mechanism explaining the link between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction; however, this postulate remains to be empirically examined.

Sexual Self-Concept

Sexual self-concept refers to the ideas, thoughts, and feelings individuals have about themselves as sexual persons, and is an important component of sexual health (Deutsch et al., 2014). Sexual self-concept develops mostly during adolescence through sexual growth and experience, and is shaped by social expectations (O’Sullivan et al., 2006). Snell and Papini (1989) were among the first to conceptualize and operationalize sexual self-concept by developing a measure that has become a landmark in the scientific literature. According to these authors, sexual self-concept is a construct encompassing sexual esteem (i.e., positive outlook on and confidence in one’s capacity to experience sexuality in a satisfying and enjoyable way), sexual depression (i.e., feelings of depression regarding one’s sex life), and sexual preoccupation (i.e., the tendency to think about sex excessively).

Studies show that dispositional mindfulness can encourage introspection, with authenticity and acceptance (Chen & Murphy, 2019; Shapiro et al., 2006), greater self-awareness, and less self-evaluation (Hanley & Garland, 2017; Verplanken et al., 2007). Individuals who exhibit enhanced mindfulness may have more space to process their stressful experiences and perceive them as something that can contribute positively to their lives (i.e., positive reappraisal; Garland et al., 2011). Thus, CSA survivors with greater mindfulness dispositions may evaluate themselves less negatively or present less rigid thought patterns when appraising themselves as sexual beings (i.e., sexual self-concept); this may be due to the fact that they are more likely to have a nuanced view of their trauma and its impact on themselves as sexual beings. Dispositional mindfulness can also promote greater mental clarity in terms of thoughts and emotions (Kang et al., 2015). This can be particularly important among trauma survivors, as they are more prone to automatic functioning (i.e., undertaking actions with little awareness) on a daily basis (Evans et al., 2015). This may hinder their ability to connect with their sexual self and, ultimately, to positively evaluate their sexuality (i.e., sexual satisfaction).

Although no study has directly examined the role of sexual self-concept in the link between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction, previous studies provide evidence for this underlying mechanism. Notably, past studies have shown that sexual esteem, one of the components of sexual self-concept, may act as an explanatory mechanism for sexual satisfaction in university students (Peixoto et al., 2018) and CSA survivors (Lemieux & Byers, 2008). Antičević et al. (2017) have shown that lower sexual self-esteem and higher sexual depression were linked to lower sexual satisfaction in the general Croatian population. Similarly, a study conducted among CSA survivors demonstrated that those who displayed higher levels of sexual depression tended to be less sexuality satisfied, while those with higher levels of sexual esteem were more sexually satisfied (Guyon, Fernet & Godbout, 2020b). Taken together, these findings support the plausibility that dispositional mindfulness might be positively associated with greater sexual self-concept, which in turn could lead to higher sexual satisfaction in CSA survivors. These associations are yet to be tested simultaneously in an empirical study.

Research Aims and Hypotheses

This study aimed to examine the role of sexual self-concept (i.e., sexual esteem, sexual preoccupation, and sexual depression) in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction among adult CSA survivors. Based on theoretical and empirical assumptions, we hypothesized that: (H1) higher levels of dispositional mindfulness would be associated with greater sexual self-concept (i.e., more sexual self-esteem, and less sexual depression and sexual preoccupation; (H2) greater sexual self-concept would be associated with higher levels of sexual satisfaction; and (H3) dispositional mindfulness would be positively associated with sexual satisfaction through the indirect effect of sexual self-concept. More precisely, we predicted that dispositional mindfulness would be associated with greater sexual self-concept, which in turn would be associated with sexual satisfaction. We also hypothesized that all three dimensions of sexual self-concept would be intercorrelated (H4).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited through social media posts, printed posters, and word of mouth in community organizations intended for CSA survivors. To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years old and have had experienced at least one occurrence of CSA as defined by the Criminal Code of Canada (1985); this code refers to any sexual act, with or without contact, between a child under the age of 16 and a person older by five or more years or in a position of authority, with or without the use of physical force or the child’s consent, or any unwanted sexual acts before the age of 18. Participants signed a consent form in which the study’s objectives, procedure, potential risks and benefits, and confidentiality were detailed. Then, they completed an approximately 40-minute survey on a secure website (i.e., Lime Survey). A list of support resources was provided at the end of the questionnaire. This study was approved by the Université du Québec à Montréal’s institutional research ethics board.

The final sample was comprised of 175 participants (60.6% women, 39.4% men) aged between 18 and 70 years (M = 41.2, SD = 13.0) who had experienced CSA. Participants were born in Canada (75.7%), Eastern Europe (22.0%), or the Caribbean (2.3%). They self-identified as heterosexual (73.3%), homosexual (10.8%), bisexual (8.0%) or another sexual orientation (i.e., queer, questioning, asexual; 8.0%). Participants reported being employed (57.4%), students (18.2%), unemployed (7.4%), or having another occupational status (e.g., retired, disabled; 17.0%). They had completed an undergraduate (34.9%), graduate (22.9%), or a college/professional (26.9%) degree, or had a primary or secondary school education (5.4%). Most (45.1%) were single, while 26.9% were in a common-law partnership or cohabiting, 14.0% were married, 12.0% were in a committed, non-cohabiting relationship, and 1.1% were divorced. CSA characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA) Characteristics.

| Participants (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sexual acts | |

| Without contact (voyeurism, exhibitionism, viewing of sex scenes) | 64.8 |

| Fondling | 92.0 |

| Penetration (oral, vaginal, anal) | 70.5 |

| Perpetrator’s identity | |

| Stranger | 22.9 |

| Friend or Acquaintance | 55.7 |

| Romantic partner | 17.0 |

| Immediate or extended family member | 58.0 |

| Frequency of CSA | |

| 1 time | 22.2 |

| 2 to 10 times | 34.7 |

| 10 to 20 times | 14.8 |

| 20 to 50 times | 8.5 |

| Too many times to count | 29.5 |

| Duration of CSA | |

| Less than 3 months | 32.4 |

| 3 months to 1 year | 17.0 |

| 1 to 5 years | 32.4 |

| More than 5 years | 26.7 |

Note. Cumulative percentage exceeds 100% as participants could report more than one experience of CSA.

Measures

Sociodemographic information including age, gender, sexual orientation, birthplace, occupation, education level, and relational status were collected. CSA-related information was also assessed, where participants indicated the types of sexual acts they experienced, their relationship to the abuser(s), and the frequency and duration of the CSA experience(s).

Dispositional Mindfulness

A 5-item French adaptation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003, translated into French by Jermann et al., 2009) was used to assess participants’ daily mindfulness dispositions. Participants indicated the frequency at which they experienced or did not experience mindfulness dispositions (e.g., “I find myself doing things without paying attention”) on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Total scores ranged from 5 to 30, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of dispositional mindfulness. The original scale demonstrated good internal reliability in previous samples (α = .89; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007). Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .88.

Sexual Self-Concept

A French adaptation of the short version of the Sexuality Scale (SS; Snell & Papini, 1989; Wiederman & Allgeier, 1993) was used to assess sexual self-concept. For the purpose of this study, the original scale was translated into French using the back-translation method (Vallerand, 1989). This scale is comprised of three 5-item subscales: (1) Sexual esteem (e.g., “I am confident about myself as a sexual partner”); (2) Sexual preoccupation (e.g., “I think about sex more than anything else”), and (3) Sexual depression (e.g., “I feel down about my sex life”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Disagree) to 5 (Agree). Total scores for each subscale ranged from 5 to 25. The original version of this scale showed excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .90 to .93 (Snell et al, 1992). Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .92 to .94 in the present study.

Sexual Satisfaction

A French version of the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (Lawrance & Byers, 1995; translated into French by Bois et al., 2013) was used to assess overall sexual satisfaction, which is comprised of five 7-point bipolar scales: bad–good, unpleasant–pleasant, negative–positive, unsatisfying–satisfying, and worthless–valuable. Total scores ranged from 5 to 35, with higher scores representing greater sexual satisfaction. The original scale showed excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .95 to .96 (Byers & Macneil, 2006). Cronbach’s alpha was .92 in the present sample.

Analyses

This study used a cross-sectional design where the sequence of model variables was determined based on theoretical and empirical evidence, suggesting that mindfulness is positively related to childhood trauma survivors’ higher sexual satisfaction (e.g., Godbout et al., 2020). This theoretically grounded analytic strategy, often privileged in the trauma literature (e.g., Godbout et al., 2014), is commonly recommended for such analyses (Byrne, 2013).

Firstly, descriptive and correlational analyses were performed on the study variables using SPSS version 26. To test the hypothesized integrative model, path analyses were conducted using Mplus version 8.4, which accounts for missing data using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation method. In line with many authors’ recommendations (see Hayes & Rockwood, 2017; Kline, 2010; McDonald & Ho, 2002), model fit was tested using the following indices: model χ2, χ2 to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The model was determined to fit well if most indices met or exceeded generally accepted values. While it is assumed that model χ2 should be non-significant if the model fits well, relying solely on χ2 to evaluate model fit is not recommended due to its many limitations (Brown, 2015). According to Kline (2010), good model fit is obtained when CFI is greater than or equal to 0.9, SRMR is below 0.08, and RMSEA is below or equal to 0.06 (Kline, 2010). Lastly, bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017) were conducted in order to test the indirect effect of each sexual self-concept dimension (i.e., sexual esteem, sexual preoccupations, and sexual depression) on the association between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction. This method is robust in cases of non-normal distributions and can minimize measurement error (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017). An indirect effect is considered significant if the resulting bootstrap confidence intervals do not contain zero (MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009). Standardized direct, specific indirect, total indirect, and total effects were estimated.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 2. Statistically significant correlations were found between all study variables except for sexual preoccupation, which was only significantly correlated with the other two sexual self-concept dimensions. Correlations were also computed between study variables and sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, birthplace, sexual orientation, relationship status). Age and relationship status were the only sociodemographic variables to significantly correlate with sexual satisfaction. They were therefore included as control variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dispositional mindfulness (1–6) | 4.24 | 1.19 | — | .23** | −.13 | −.36*** | .35*** | .01 | .09 |

| 2. Sexual esteem (1–5) | 3.17 | 1.04 | — | .16* | −.52*** | .69*** | −.06 | .17* | |

| 3. Sexual preoccupation (1–5) | 2.28 | 1.07 | — | .15* | .04 | −.07 | −.07 | ||

| 4. Sexual depression (1–5) | 2.43 | 1.23 | — | −.67*** | .13 | −.16* | |||

| 5. Sexual satisfaction (1–7) | 4.62 | 1.51 | — | −.25** | .25** | ||||

| 6. Age | 41.17 | 13.04 | — | −.02 | |||||

| 7. Relationship status (0–1)a | — | — | — |

Relationship status was dichotomized and coded as 0 = single and 1 = currently in a relationship.

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

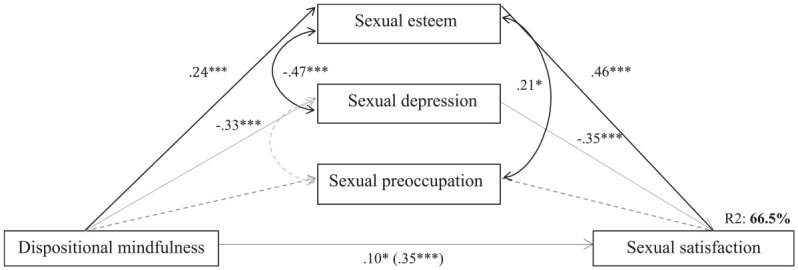

The direct path from dispositional mindfulness to sexual satisfaction was statistically significant (β = .35, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.20, 0.49], p < .001) and explained 12.4% of the variance in sexual satisfaction. Sexual self-concept dimensions (i.e., sexual self-esteem, sexual preoccupation, and sexual depression) and covariates (i.e., age and relationship status) were then added and tested as an integrative model. Dispositional mindfulness was significantly and positively associated with sexual esteem (β = .24, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.10, 0.38], p = .001), and negatively associated with sexual depression (β = −.33, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [–0.47, –0.20], p < .001). Dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction were not significantly associated with sexual preoccupation (respectively β = –.15, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [–0.03, 0.01], p = .06); β = .04, SE = .05, 95% CI [–0.09, 0.19], p = .46). As per path analysis recommendations, insignificant paths (i.e., between dispositional mindfulness and sexual preoccupation; between sexual preoccupation and sexual satisfaction) were removed from the final model (McDonald & Ho, 2002). However, as it is an integral part of sexual self-concept, sexual preoccupation was maintained as a covariate.

Path analyses for the integrative model indicated good fit: CFI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.042, CI [0.000, 0.119], χ2 = 6.507, p = .260, χ2/df = 1.301, SRMR = 0.037. A significant indirect path between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction was found through sexual esteem (β = .11, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.07, 0.27], p = .002) and sexual depression (β = .12, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.08, 0.26], p = .001). The direct path from dispositional mindfulness to sexual satisfaction remained significant in the final model (β = .10, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.19], p = .031), suggesting partial mediation. Overall, the model accounted for 66.5% of the variance in sexual satisfaction.

An alternative model that positioned sexual self-concept as an independent variable, dispositional mindfulness as a mediator and sexual satisfaction as a dependent variable, was tested. Results yielded that dispositional mindfulness did not have a significant indirect effect between any of the three dimensions of sexual self-concept and sexual satisfaction. In addition, this alternative model showed a slightly lower fit to the data for all indices (CFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.052, CI [0.000, 0.120], χ2 = 8.849, p = .182, Ratio χ2/dl = 1.475, SRMR = 0.041) compared to the hypothesized model. Thereby, the hypothesized model seems to offer a better representation of the links between dispositional mindfulness, sexual self-concept, and sexual satisfaction.

The final model including standardized coefficients for significant paths is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Final model illustrating the indirect effect of sexual esteem and sexual depression on the association between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the role of sexual self-concept (i.e., sexual esteem, sexual preoccupation, and sexual depression) in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction among adult CSA survivors. Path analyses confirmed the hypothesis of an indirect effect of sexual self-concept on this relationship. Dispositional mindfulness was linked with higher sexual esteem and lower sexual depression, which in turn was associated with greater sexual satisfaction. Two components of sexual self-concept—sexual esteem and sexual depression—were found to act as mechanisms explaining the association between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction. As such, survivors that are more prone to act with awareness during their daily activities may evaluate themselves more positively as sexual partners and feel less depressed when they think about their sexuality; this in turn may lead to overall positive appraisals of their sex lives. The positive association identified between dispositional mindfulness (i.e., focused attention and acting with awareness; Brown & Ryan, 2003) and sexual self-concept is a new finding that highlights the importance of sexual self-perceptions in CSA survivors’ sexual satisfaction, and ultimately, in their recovery process. While this avenue has been sparingly addressed in previous studies, this study may contribute to advance trauma research and treatment options for CSA survivors, as its findings support the relevance of mindfulness and sexual self-concept as key intervention targets for the promotion of sexual satisfaction.

The present findings can be interpreted in light of the various mental and emotional processes involved in mindfulness. Notably, anchoring oneself in the present moment and connecting to what is experienced internally can promote greater emotional and cognitive clarity (Kang et al., 2015), especially in trauma survivors. Indeed, children’s bodies are invaded during CSA events, which may be associated with pain and strong emotions such as fear, helplessness, and shame (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985). Thus, survivors may develop coping strategies that dissociate them from the present, their bodies, as well as from thoughts deemed too painful during and after their trauma (Schimmenti & Caretti, 2016). Given the sexual nature of CSA, dissociative coping strategies may spill over into their sex lives (e.g., sexual dissociation; Bird et al., 2014). As such, greater mindfulness dispositions may allow CSA survivors to remain engaged and connected with a broader range of emotions (Berenz et al., 2018), while acting as a protective factor against the perpetuation or crystallization of cognitive schemas associated with negative affect (Smith et al., 2011). A greater “tolerance” of distressing emotions may enhance sexual satisfaction, as it can help survivors better cope with factors that negatively affect sexual satisfaction, such as self-criticism, low self-esteem, discomfort with intimacy, and performance anxiety (del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014).

Research has also found dispositional mindfulness to be positively and uniquely related to positive reappraisal (i.e., perceiving stressful events as meaningful to oneself; Garland et al., 2011). According to the Mindful Coping Model (Garland et al., 2009), mindfulness can bring a certain detachment from thoughts and emotions, the latter of which can be perceived as ephemeral or transitory. This metacognitive state promotes psychological flexibility and an integrative understanding of past and current stressful events, thereby increasing positive reappraisal that promotes positive affect and well-being following adverse life situations (Garland et al., 2009). Progressively, CSA survivors’ experience of the present moment might become less contaminated by past traumatic sexual experiences (e.g., fewer intrusive memories and related negative thoughts). Thus, mindfulness dispositions may help CSA survivors to evaluate themselves less negatively or rigidly as sexual beings. In turn, mindfulness and the psychological flexibility of one’s sex life may have a positive impact on sexual self-concept (e.g., distancing oneself from social norms regarding sexual performance to promote better sexual esteem; Reese et al., 2010). Survivors with more positive sexual self-perceptions may present higher levels of sexual satisfaction, as they may be less likely to define their sexuality solely in light of the negative aspects of their sexual past.

The current findings also offer a possible explanation for the effects of mindfulness, specifically on sexual esteem and sexual depression. When individuals purposely direct their attention to the present moment, they may be more focused on the tasks or activities at hand and allocate fewer cognitive resources to the cultivation of negative thoughts about themselves, such as rumination (Kang et al., 2015). This is particularly important considering that many CSA survivors engage in repetitive negative thinking (Mansueto et al., 2021) and that one’s sexual self-concept can be influenced by past sexual experiences (Snell & Papini, 1989). It is therefore plausible that survivors who are more mindful are also less likely to dwell on distressing or unsatisfying past sexual experiences when they think about or evaluate their sexuality. These survivors are therefore more protected from the integration of negative experiences into their sexual self-concept. Moreover, it is also possible that survivors who are high in dispositional mindfulness are more likely to have responded to the questionnaire items with their present experiences and feelings instead of with their past negative experiences in mind. This would thus result in a more positive evaluation of the sexual self.

The current results parallel those of previous research having found that CSA survivors are more likely to report lower sexual esteem, which can in turn negatively affect their sexual satisfaction (Barnum & Perrone-McGovern, 2017). Further, Heppner and Kernis (2007) postulated that higher levels of mindfulness dispositions could have an effect on self-esteem. Notably, they explained that individuals with “fragile” self-esteem (i.e., unstable, contingent, and discrepant) tend to have feelings of self-worth that are superficially anchored (i.e., derived from superficial and external elements). These individuals can be easily undermined when challenged. In addition, individuals with fragile self-esteem tend to use maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., dissociation, denial), contrary to individuals with more “secure” self-esteem. However, dispositional mindfulness may foster higher levels of “secure” self-esteem and authenticity (i.e., unimpeded functioning of one’s true or core self in daily life; Heppner & Kernis, 2007). The notion of authentic self has also been recognized as a mechanism explaining the relationship between mindfulness and psychological well-being (Chen & Murphy, 2019). The present findings offer evidence to support a similar process that may take place in sexuality, where a more integrated and authentic sexual self-concept would promote sexual satisfaction.

The current results have also shown that sexual preoccupation did not have an indirect effect on the association between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction, but that it was significantly associated with sexual esteem. Sexual preoccupation—the tendency to think about sex to an excessive degree (Snell & Papini, 1989)—can involve frequent positive thoughts about sexuality (e.g., having fantasies, frequently thinking about pleasurable sexual encounters), or on the contrary, ruminations (e.g., frequently thinking about negative aspects of one’s sexuality). These opposite manifestations of sexual preoccupation could potentially explain its nonsignificant effect on the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and sexual satisfaction.

Finally, descriptive analyses revealed that the present sample of CSA survivors presented similar levels of dispositional mindfulness to those found in community samples of undergraduate students (Osman et al., 2016; Wiederman & Allgeier, 1993). However, CSA survivors show relatively higher rates of sexual depression than those found in these samples. The present sample’s high levels of dispositional mindfulness and sexual esteem could reflect survivors’ healing trajectories, suggesting survivors may be coping with their trauma using strategies aimed at managing CSA experiences and associated suffering using dispositional mindfulness, which can in turn foster sexual esteem. Since participants’ mean age was relatively high (M = 41.17; SD = 13.04) and many reported using support services, they may potentially have had the time, opportunities, and tools to metabolize their trauma. However, their high levels of sexual depression may indicate that, despite survivors’ positive adaptation and resilience, sexuality can still be a challenging aspect of their lives, considering the nature of their trauma.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study bears some limitations. First, the study is based on self-reported data, which are prone to social desirability bias, especially considering the sensitive nature of the examined topics (i.e., CSA and sexuality). Second, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for causality to be determined between variables in the model. Sexual self-concept may be understood as a process evolving over time, and future studies investigating the links between mindfulness, sexual self-concept, and sexual satisfaction would benefit from a longitudinal design. In addition, since relationship status can influence sexual satisfaction (Birnie-Porter & Hunt, 2015) and that the way individuals perceive themselves can be influenced by their relationship’s dynamic (Mund et al., 2015), it would be relevant to study CSA survivors’ sexual self-concept using a dyadic approach. Third, even though our model explained a substantial proportion of variance in sexual satisfaction, the unexplained variance nonetheless indicates that other variables may explain sexual satisfaction in CSA survivors. It would be relevant to examine other variables related to the sexual self that were not assessed in this study (e.g., sexual consciousness, sexual monitoring). Fourth, although the MAAS questionnaire (Brown & Ryan, 2003) assesses individuals’ focused attention and conscious action in daily life, it does not consider other mindfulness dimensions or particularities of the sexual context. Thus, future studies could test the present model using the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer et al., 2006) or the Sexual Mindfulness Measure (Leavitt et al., 2019). Similarly, the short version of the SS has limitations. Notably, as Weiderman and Allgeier (1993) suggested, future studies should confirm the structural validity of this measure. Moreover, although this measure is widely used in studies among adults (e.g. Antičević et al., 2017; Pearlman-Avnion et al., 2017), it may not capture the complexity of sexual self-concept and does not account for the specificities that CSA survivors may experience (e.g., perceiving oneself as a sexual object). Future studies could thereby document the diverse manifestations of male and female CSA survivors’ sexual self-concept and develop comprehensive measures that reflect their particular reality. Fifth, despite recruitment efforts, the sample did not include enough participants who were born outside of Canada, or from sex and gender minorities. Further study is needed to confirm if the current results might be generalized to adults from cultural, sexual, or gender diversities, given they are more vulnerable to sexual victimization (Martin-Storey et al., 2018) and may experience unique challenges (e.g., minority stress). Similarly, because participants were primarily recruited through community organizations serving CSA survivors, the results are not necessarily representative of those who do not use these services. It is also possible that survivors who avoid discussing CSA experiences or sexuality were less likely to participate in this study. Since this is the reality for many CSA survivors, the results therefore do not represent this entire population. Thus, it would be important to test the present model with larger and more diverse samples and deploy recruitment methods that reach survivors with different sexual and help-seeking trajectories. Lastly, it would be relevant to test the model within a non-victim population or with survivors who endured other types of childhood trauma to test whether the model is specific to CSA survivors. Likewise, it would be beneficial to test the gender invariance of such a model using a larger sample.

Implications for Practice

These empirical findings support the relevance of mindfulness-based interventions aimed at improving CSA survivors’ sexual satisfaction. Such interventions could focus on the development of knowledge and skills involved in mindfulness, such as focused attention, acting with awareness, self-regulation, and detachment. In particular, mindfulness and the detachment it can foster may help survivors understand that their CSA experiences, while being a source of suffering and negative outcomes in their lives, do not define their sexual self.

The current findings also support the importance of inviting survivors to reflect on their sexual self, such as on one’s needs, desires, and values, in order to better understand themselves as sexual beings and partners (i.e., sexual self-concept). As such, survivors could benefit from experiencing their sexuality more authentically and detached from previous traumatic experiences. Deconstructing what belongs to the aftermath of CSA and what defines survivors’ identities could also potentially contribute to the building of a more coherent, positive, and holistic sexual self. Likewise, increasing awareness of the negative emotions that may have been embedded in survivors’ sexual self-concept as a result of CSA (e.g., depressive thoughts about sexuality, a perception of oneself as a bad sexual partner) can foster a better understanding of how these emotions can influence survivors’ behaviors, cognitions, and sexual satisfaction. This study emphasizes the need for intervention aimed at developing survivors’ sexual esteem to promote a more satisfying sex life (e.g., reflection exercises on what is an adequate sexual partner or sexuality, sexual self-discovery, and appraisal of oneself as a valuable sexual partner). As these interventions are likely to revive painful emotions and flashbacks related to CSA, it is important to ground them in a secure context guided by a trauma-sensitive approach. Working with the window of tolerance (model of autonomic arousal; Siegel, 1999), practitioners could improve survivors’ metabolization of their trauma while tolerating and remaining attentive to the unpleasant emotions that emerge. At the same time, practitioners can ensure that survivors do not become emotionally dysregulated or re-traumatized by teaching survivors to identify psychological and physical cues that may indicate they are no longer within their window of tolerance and supporting emotion regulation skills, which can also be useful in sexual contexts.

Conclusion

Previous studies have documented the positive effects of mindfulness on individuals’ sexuality. However, mindfulness’s effects on CSA survivors’ sexual satisfaction remain little investigated. The present study found that sexual self-concept, and more specifically, its sexual esteem and sexual depression dimensions, do act as explanatory mechanisms. These findings support survivors’ sexual empowerment and suggest that having a fulfilling sex life is possible despite traumatic experiences. Nevertheless, further research is needed to understand the complex interplay between mindfulness and sexual self-concept. A better understanding of how mindfulness can promote greater sexual self-concept would ultimately contribute to treatment options’ effectiveness and ultimately, survivors’ recovery.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to the survivors who participated in this project and the community services that were involved.

Author Biographies

Roxanne Guyon, is a PhD student in sexology at the University of Quebec at Montreal. Her research is focused on relational and sexual functioning of child sexual abuse survivors as well as their recovery and resilience processes.

Mylène Fernet, PhD, is a professor in the department of sexology at the University of Quebec at Montreal. Her research is focused on interpersonal and sexual violence in both youth and adults as well as women’s sexuality from a prevention and health promotion perspective.

Marianne Girard, is a PhD student in sexology at the University of Quebec at Montreal. Her research is focused on the impact of childhood sexual abuse on survivors’ adjustment regarding domestic violence, mental health problems and sexuality.

Marie-Marthe Cousineau, PhD, is a professor in the School of Criminology at University of Montreal. Her research is focused on life trajectories of victimized women as well as in penal policies and practices.

Monique Tardif, PhD, is a professor in the department of sexology at the University of Quebec at Montreal and also a therapist. Her research is focused on childhood sexual abuse, particularly from the perspective of the adolescent perpetrator and their families.

Natacha Godbout, PhD, is a professor in the department of sexology at the University of Quebec at Montreal and also a therapist. Her research is focused on the impacts of relational trauma on sexual, psychological and relational functioning in adulthood.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This research was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (#430-2016-00951) awarded to Mylène Fernet and by a scholarship from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Société et Culture (#2022-B2Z-297045) and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#752-2021-2334) awarded to Roxanne Guyon.

ORCID iDs: Roxanne Guyon  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1303-0618

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1303-0618

Mylène Fernet  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1961-2408

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1961-2408

Marianne Girard  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4728-2749

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4728-2749

References

- Antičević V., Jokić-Begić N., Britvić D. (2017). Sexual self-concept, sexual satisfaction, and attachment among single and coupled individuals. Personal Relationships, 24(4), 858–868. 10.1111/pere.12217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R. A., Smith G. T., Hopkins J., Krietemeyer J., Toney L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum E. L., Perrone-McGovern K. M. (2017). Attachment, self-esteem and subjective well-being among survivors of childhood sexual trauma. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 39(1), 39-55. 10.17744/mehc.39.1.04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berenz E. C., Vujanovic A., Rappaport L. M., Kevorkian S., Gonzalez R. E., Chowdhury N., Dutcher C., Dick D. M., Kender K. S., Amstadter A. (2018). A multimodal study of childhood trauma and distress tolerance in young adulthood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(7), 795–810. 10.1080/10926771.2017.1382636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigras N., Godbout N., Briere J. (2015). Child sexual abuse, sexual anxiety, and sexual satisfaction: The role of self-capacities. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(5), 464–483. 10.1080/10538712.2015.1042184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigras N., Vaillancourt-Morel M. P., Nolin M. C., Bergeron S. (2020). Associations between childhood sexual abuse and sexual well-being in adulthood: A systematic literature review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 30(3), 1–21. 10.1080/10538712.2020.1825148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird E. R., Seehuus M., Clifton J., Rellini A. H. (2014). Dissociation during sex and sexual arousal in women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(5), 953–964. 10.1007/s10508-013-0191-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnie-Porter C., Hunt M. (2015). Does relationship status matter for sexual satisfaction? The roles of intimacy and attachment avoidance in sexual satisfaction across five types of ongoing sexual relationships. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 24(2), 174–183. 10.3138/cjhs.242-A5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bois K., Bergeron S., Rosen N. O., McDuff P., Grégoire C. (2013). Sexual and relationship intimacy among women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: Associations with sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and pain self-efficacy. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(8), 2024–2035. 10.1111/jsm.12210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto L. A., Seal B. N., Rellini A. (2012). Pilot study of a brief cognitive behavioral versus mindfulness-based intervention for women with sexual distress and a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 38(1), 1–27. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. W., Ryan R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byers E. S., Macneil S. (2006). Further validation of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 32(1), 53–69. 10.1080/00926230500232917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Murphy D. (2019). The mediating role of authenticity on mindfulness and wellbeing: A cross cultural analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 10(1), 40–55. 10.1080/21507686.2018.1556171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D., Beeghly M. (Eds.). (1990). The self in transition: Infancy to childhood. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes M., Santos-Iglesias P., Sierra J. C. (2014). A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 14(1), 67–75. 10.1016/S1697-2600(14)70038-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch A. R., Hoffman L., Wilcox B. L. (2014). Sexual self-concept: Testing a hypothetical model for men and women. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(8), 932–945. 10.1080/00224499.2013.805315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déziel J., Godbout N., Hébert M. (2018). Anxiety, dispositional mindfulness, and sexual desire in men consulting in clinical sexology: A mediational model. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(5), 513–520. 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussault É., Fernet M., Fernet N. (2020). A metasynthesis of qualitative studies on mindfulness, sexuality, and relationality. Mindfulness, 11(12), 2682–2694. 10.1007/s12671-020-01463-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esper L. H., da Silva Gherardi-Donato E. C. (2019). Mindfulness-based interventions for women victims of interpersonal violence: A systematic review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(1), 120–130. 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G. J., Reid G., Preston P., Palmier-Claus J., Sellwood W. (2015). Trauma and psychosis: The mediating role of self-concept clarity and dissociation. Psychiatry Research, 228(3), 626–632. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenidou F., Kapoteli V., Moisidis K., Koutsogiannis I., Giakoumelos A., Hatzichristou D. (2008). Women’s sexual health: Presence of a sexual problem may not affect women’s satisfaction from their sexual function. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(3), 631–639. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00644.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Browne A. (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55(4), 530–541. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland E., Gaylord S., Park J. (2009). The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore, 5(1), 37–44. 10.1016/j.explore.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland E. L., Gaylord S. A., Fredrickson B. L. (2011). Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: An upward spiral process. Mindfulness, 2(1), 59–67. 10.1007/s12671-011-0043-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout N., Bakhos G., Dussault É., Hébert M. (2020). Childhood interpersonal trauma and sexual satisfaction in patients seeing sex therapy: Examining mindfulness and psychological distress as mediators. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(1), 43–56. 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1626309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout N., Briere J., Sabourin S., Lussier Y. (2014). Child sexual abuse and subsequent relational and personal functioning: The role of parental support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(2), 317–325. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon R., Fernet M., Canivet C., Tardif M., Godbout N. (2020. a). Sexual self-concept among men and women child sexual abuse survivors: Emergence of differentiated profiles. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104, 104481. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon R., Fernet M., Godbout N. (2020. b). “A journey back to my wholeness”: A qualitative metasynthesis on the relational and sexual recovery process of child sexual abuse survivors. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Resilience, 7(1), 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley A. W., Garland E. L. (2017). Clarity of mind: Structural equation modeling of associations between dispositional mindfulness, self-concept clarity and psychological well-being. Personality and individual differences, 106, 334–339. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F., Rockwood N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner W. L., Kernis M. H. (2007). “Quiet ego” functioning: The complementary roles of mindfulness, authenticity, and secure high self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 248–251. 10.1080/10478400701598330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jermann F., Billieux J., Larøi F., d’Argembeau A., Bondolfi G., Zermatten A., Van der Linden M. (2009). Mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS): Psychometric properties of the French translation and exploration of its relations with emotion regulation strategies. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 506–514. 10.1037/a0017032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2015). Mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1481–1483. 10.1007/s12671-015-0456-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Gray J. R., Dovidio J. F. (2015). The head and the heart: Effects of understanding and experiencing lovingkindness on attitudes toward the self and others. Mindfulness, 6(5), 1063–1070. 10.1007/s12671-014-0355-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khaddouma A., Gordon K. C., Bolden J. (2015). Zen and the art of sex: Examining associations among mindfulness, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction in dating relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(2), 268–285. 10.1080/14681994.2014.992408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2010). Promise and pitfalls of structural equation modeling in gifted research. In Thompson B., Subotnik R. F. (Eds.), Methodologies for conducting research on giftedness (3rd ed., pp. 147–169). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lacelle C., Hébert M., Lavoie F., Vitaro F., Tremblay R. E. (2012). Sexual health in women reporting a history of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(3), 247–259. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer E. J. (1989). Mindfulness. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance K. A., Byers E. S. (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 2(4), 267–285. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt C. E., Lefkowitz E. S., Waterman E. A. (2019). The role of sexual mindfulness in sexual wellbeing, relational wellbeing, and self-esteem. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(6), 497–509. 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1572680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux S. R., Byers E. S. (2008). The sexual well-being of women who have experienced child sexual abuse. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(2), 126–144. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00418.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J., Anderson E. J. (2007). Further psychometric validation of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(4), 289–293. 10.1007/s10862-007-9045-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Fairchild A. J. (2009). Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 16–20. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltz W. (2012). The sexual healing journey: A guide for survivors of sexual abuse. New York, NY: William Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Mansueto G., Cavallo C., Palmieri S., Ruggiero G. M., Sassaroli S., Caselli G. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and repetitive negative thinking in adulthood: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(3), 557–568. 10.1002/cpp.2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A., Paquette G., Bergeron M., Dion J., Daigneault I., Hébert M., Ricci S. (2018). Sexual violence on campus: Differences across gender and sexual minority status. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(6), 701–707. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. P., Ho M. H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mund M., Finn C., Hagemeyer B., Zimmermann J., Neyer F. J. (2015). The dynamics of self-esteem in partner relationships. European Journal of Personality, 29(2), 235–249. 10.1002/per.1984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe B. C., Weaver A. D. (2016). Mindfulness, cognitive distraction, and sexual well-being in women. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 25(2), 99–108. 10.3138/cjhs.252-A3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Lamis D. A., Bagge C. L., Freedenthal S., Barnes S. M. (2016). The mindful attention awareness scale: Further examination of dimensionality, reliability, and concurrent validity estimates. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(2), 189–199. 10.1080/00223891.2015.1095761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan L. F., Meyer-Bahlburg H. F., McKeague I. W. (2006). The development of the sexual self-concept inventory for early adolescent girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 139–149. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00277.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman-Avnion S., Cohen N., Eldan A. (2017). Sexual well-being and quality of life among high-functioning adults with autism. Sexuality and Disability, 35(3), 279–293. 10.1007/s11195-017-9490-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto M. M., Amarelo-Pires I., Pimentel Biscaia M. S., Machado P. P. (2018). Sexual self-esteem, sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction in Portuguese heterosexual university students. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(4), 305–316. 10.1080/19419899.2018.1491413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepping C. A., Cronin T. J., Lyons A., Caldwell J. G. (2018). The effects of mindfulness on sexual outcomes: The role of emotion regulation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1601–1612. 10.1007/s10508-017-1127-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese J. B., Keefe F. J., Somers T. J., Abernethy A. P. (2010). Coping with sexual concerns after cancer: the use of flexible coping. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18(7), 785–800. 10.1007/s00520-010-0819-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellini A. H., Meston C. M. (2011). Sexual self-schemas, sexual dysfunction, and the sexual responses of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(2), 351–362. 10.1007/s10508-010-9694-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Chung M. C., Thorne L. (2011). A narrative exploration of the sense of self of women recovering from childhood sexual abuse. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 24(2), 101–113. 10.1080/09515070.2011.586414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Caretti V. (2016). Linking the overwhelming with the unbearable: Developmental trauma, dissociation, and the disconnected self. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 33(1), 106–128. 10.1037/a0038019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S. L., Carlson L. E., Astin J. A., Freedman B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. 10.1002/jclp.20237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind. New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. W., Ortiz J. A., Steffen L. E., Tooley E. M., Wiggins K. T., Yeater E. A., Montoya J. D., Bernard M. L. (2011). Mindfulness is associated with fewer PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, physical symptoms, and alcohol problems in urban firefighters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(5), 613–617. 10.1037/a0025189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell W. E., Jr., Fisher T. D., Schuh T. (1992). Reliability and validity of the sexuality scale: A measure of sexual-esteem, sexual-depression, and sexual-preoccupation. Journal of Sex Research, 29, 261–273. 10.1080/00224499209551646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snell W. E., Jr., Papini D. R. (1989). The sexuality scale: An instrument to measure sexual-esteem, sexual-depression, and sexual-preoccupation. Journal of Sex Research, 26, 256–263. 10.1080/00224498909551510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand R. J. (1989). Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française [Towards a methodology for cross-cultural validation of psychological questionnaires: Implications for French language research]. Canadian Psychology, 30(4), 662–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken B., Friborg O., Wang C. E., Trafimow D., Woolf K. (2007). Mental habits: Metacognitive reflection on negative self-thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 526–541. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman M. W., Allgeier E. R. (1993). The measurement of sexual-esteem: Investigation of Snell and Papini’s (1989) sexuality scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 27(1), 88–102. [Google Scholar]