Abstract

Adaptive control processes that minimise distraction often operate in a context-specific manner. For example, they may minimise distraction from irrelevant conversations during a lecture but not in the hallway afterwards. It remains unclear, however, whether (a) salient perceptual features or (b) task sets based on such features serve as contextual boundaries for adaptive control in standard distractor-interference tasks. To distinguish between these possibilities, we manipulated whether the structure of a standard, visual distractor-interference task allowed (Experiment 1) or did not allow (Experiment 2) participants to associate salient visual features (i.e., colour patches and colour words) with different task sets. We found that changing salient visual features across consecutive trials reduced a popular measure of adaptive control in distractor-interference tasks—the congruency sequence effect (CSE)—only when the task structure allowed participants to associate these visual features with different task sets. These findings extend prior support for the task set hypothesis from somewhat atypical cross-modal tasks to a standard unimodal task. In contrast, they pose a challenge to an alternative “attentional reset” hypothesis, and related views, wherein changing salient perceptual features always results in a contextual boundary for the CSE.

Keywords: Cognitive control, conflict adaptation, task set

Introduction

Humans match new information to prior experiences in order to predict future events. While drinking a cup of coffee at a local café, for example, a student may recall an associated memory of a friend who usually arrives at the café at around the same time. The student may then prepare to purchase a second cup of coffee expecting the friend to arrive soon. On some occasions, however, a change in episodic context requires humans to override previous control settings. For instance, if the student’s friend has another appointment one morning, then the student should resist the urge to purchase an extra cup of coffee. As this example shows, the ability to flexibly adapt to changing episodic contexts is an important aspect of adaptive control, which is crucial for enabling goal-driven behaviour (Miller & Cohen, 2001).

To investigate adaptive control in the laboratory, researchers use distractor-interference tasks (Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974; Eriksen & Schultz, 1979; Kunde & Wühr, 2006; Simon & Rudell, 1967). In each trial of the prime-probe task, for example, a distractor precedes a target that study participants are supposed to identify. Participants respond more slowly in incongruent trials, wherein the distractor and target indicate different responses, than in congruent trials, wherein these stimuli indicate the same response. However, this congruency effect is smaller after incongruent (versus congruent) trials. Many researchers attribute this congruency sequence effect (CSE) to control processes that minimise distraction and adapt to recent events (Botvinick et al., 2001; Egner, 2008; Gratton et al., 1992).

However, under certain conditions, other processes also contribute to the CSE. First, feature integration processes may engender a CSE when the nature of stimulus and/or response repetitions across trials is confounded with whether trial congruency repeats or alternates (Hommel et al., 2004; Mayr et al., 2003). For example, in a 2-alternative-forced-choice (2-AFC) Stroop task involving word-colour distractor-target pairs, exact stimulus and response repetitions occur only when trial congruency repeats in consecutive trials (e.g., RED-red -> RED-red) while partial repetitions occur only when trial congruency alternates (e.g., RED-red -> RED-blue). Since response times are faster for exact repetitions than for partial repetitions, this feature integration confound engenders a CSE.

Second, contingency learning processes may engender a CSE when a distractor’s identity predicts a congruent response to the target with greater-than-chance accuracy (Schmidt & De Houwer, 2011). This can occur in tasks with more than two possible stimuli and responses, wherein there are fewer unique congruent stimuli than unique incongruent stimuli. To equate the number of congruent and incongruent trials, researchers sometimes present each unique congruent stimulus more frequently than each unique incongruent stimulus (e.g., RED-red might appear three times as often as RED-blue). This procedure leads participants to prepare the “high-contingency” congruent response more strongly than each “low-contingency” incongruent response, which increases the size of the congruency effect. Since such preparation is greater when the previous trial was “high-contingency” (i.e., congruent) relative to “low-contingency” (i.e., incongruent), contingency learning processes can engender a CSE.

Critically, a CSE can appear even in the absence of feature integration and contingency learning confounds. This occurs in “confound-minimized” tasks (Jiménez & Méndez, 2014; Kim & Cho, 2014; Schmidt & Weissman, 2014), which lack these confounds. Therefore, these tasks allow researchers to isolate the contribution of cognitive control processes to the CSE.

The episodic retrieval view of the CSE

The episodic retrieval view posits that a CSE occurs when the current trial triggers the retrieval of a memory of the previous trial (Dignath et al., 2019; Egner, 2014; Frings et al., 2020; Hazeltine et al., 2011; Spapé & Hommel, 2008; Weissman et al., 2016). In this view, various features (i.e., stimuli, responses, salient perceptual features, task sets, etc.) are “bound” within an episodic memory of the previous trial (Hommel, 2004). Reencountering any of these features in the current trial then triggers the retrieval of the remaining features such as, for example, the control settings that a participant employed to minimise distraction in a previous incongruent trial. This biases control processes to adopt the same settings (e.g., to inhibit the response cued by the distractor), leading to a smaller congruency effect after incongruent trials than after congruent trials (i.e., a CSE).

The episodic retrieval view predicts that changing salient perceptual features across consecutive trials should reduce the CSE by impairing the ability to retrieve an episodic memory of the previous trial (Spapé & Hommel, 2008). In line with this prediction, changing the stimulus format (i.e., colour words vs. colour patches; Dignath et al., 2019), the voice gender of a spoken, auditory distractor word (i.e., male vs. female; Spapé & Hommel, 2008), the stimulus colour (Braem, Hickey, et al., 2014), or even the entire task (Kiesel et al., 2006) reduces the CSE. As we describe next, two variants of the episodic retrieval view posit that such contextual boundaries for the CSE arise for different reasons.

Before proceeding, however, it is important to define three terms. First, we define a “task” as a set of cognitive operations and stimulus-response mappings that a participant can implement to respond quickly and accurately to goal-relevant stimuli (Rogers & Monsell, 1995). For instance, in each trial of a Stroop colour word task, participants employ a set of cognitive operations and stimulus-response mappings to indicate the ink colour (e.g., red) in which an irrelevant colour word (e.g., GREEN) appears. Second, we define a “task set” as an intention to perform a task, which involves maintaining a task in working memory (Rogers & Monsell, 1995). For instance, to perform the Stroop task, participants need to retrieve a representation of the task from long-term memory and keep it active in working memory during the experiment. Third, we define a “dimension” as a feature of a stimulus (e.g., its colour, location, sensory modality, etc.) that can take on any of multiple values (e.g., red, blue, or green for the colour dimension) (Egner, 2008; Kornblum et al., 1990). For instance, in the Stroop task, the task-relevant stimulus dimension is ink colour and the task-irrelevant stimulus dimension is word identity.

The attentional reset hypothesis

According to the attentional reset hypothesis, changing salient perceptual features associated with the task-relevant stimulus dimension (i.e., target-related information) reduces the CSE by triggering the formation of a new event, or episode, in working memory (Kreutzfeldt et al., 2016). Here, changing salient perceptual features renders previous-trial control processes irrelevant, leading to an attentional reset in the current trial and, consequently, a reduced CSE. Critically, a change in perceptual features should trigger an attentional reset even when the overall task remains the same across consecutive trials. Thus, the attentional reset hypothesis posits that salient perceptual features on their own serve as boundaries for the CSE.

The attentional reset hypothesis fits with views, developed largely using unimodal visual tasks, wherein adaptive control processes underlying the CSE are specific to the task-relevant stimulus dimension. For instance, consider the influential conflict-monitoring view. Here, a CSE occurs because control processes increase attention to the task-relevant stimulus dimension after high-conflict incongruent trials (Botvinick et al., 2001). This reduces the influence of the distractor on performance in the next trial and thereby minimises the congruency effect. Critically, according to Braem, Abrahamse, et al. (2014), the conflict-monitoring model implies that a CSE should not appear if the task-relevant stimulus dimension—a highly salient perceptual feature—changes (for a related view, see Egner, 2014). These authors argue that since the heightened focus of attention after incongruent trials is specific to that dimension, it should vanish if that dimension changes. In line with this possibility, changing the task-relevant stimulus dimension can eliminate indices of adaptive control including the CSE (Notebaert & Verguts, 2008; Wühr et al., 2015). However, the presence of feature integration confounds in these prior studies makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about whether such effects index contextual boundaries for (a) adaptive control or (b) experimental confounds.

The task set hypothesis

The task set hypothesis posits that changing salient perceptual features reduces the CSE only when it leads participants to change the task set (i.e., representation of the current task in working memory) that underlies performance (Grant et al., 2020; Hazeltine et al., 2011; Schumacher & Hazeltine, 2016). In this view, participants use salient perceptual features (e.g., the sensory modality in which task stimuli appear) to distinguish between different subsets of trials. This allows participants to divide a complex task (e.g., a cross-modal task with visual and auditory trials) into two or more simpler tasks (e.g., a visual task and an auditory task), which reduces the complexity of the overall stimulus-response (S-R) mapping (Hazeltine et al., 2011). Critically, switching to a new task set disrupts the ability to retrieve an episodic memory of the previous trial, thereby reducing the CSE (Hazeltine et al., 2011; Spapé & Hommel, 2008). In other words, task sets based on salient perceptual features, rather than such features on their own, serve as boundaries for the CSE.

Recent findings from a confound-minimised, cross-modal prime-probe task that we designed support the task set hypothesis (Grant et al., 2020). Similar to Hazeltine et al. (2011, Experiment 1), in our first experiment the initial distractor and subsequent target both appeared in (a) the visual modality (50% of trials) or (b) the auditory modality (50% of trials). Here, participants could easily classify each trial as “visual” or “auditory.” They could also orient to the sensory modality in which the distractor appeared to prepare for the upcoming target, which always appeared in the same modality. Therefore, they were likely to form modality-specific task sets. In our second experiment, the sensory modality of the distractor varied independently of the sensory modality of the target. Here, participants could not (a) classify each trial as visual or auditory, or (b) orient to the distractor’s modality to prepare for the upcoming target. Consequently, they were likely to form a single, modality-general task set. Consistent with the task set hypothesis, but not with the attentional reset hypothesis, we found that a change in sensory modality reduced the CSE in Experiment 1 but not in Experiment 2.

Does an attentional reset explain contextual boundaries for the CSE in unimodal tasks?

Despite such evidence supporting the task set hypothesis, some findings suggest that the attentional reset hypothesis may explain contextual boundaries for the CSE in unimodal tasks. These findings show that changing salient perceptual features in unimodal tasks reduces the CSE even when orienting to the perceptual features of the distractor—the basis of task set formation in our cross-modal study (Grant et al., 2020)—cannot facilitate identification of the target (Braem, Hickey, et al., 2014; Spapé & Hommel, 2008). For instance, consider a prior study wherein participants indicated whether an auditory target was a high- or low-frequency tone while ignoring an irrelevant auditory distractor word (“high” vs. “low”) spoken in a male or female voice (Spapé & Hommel, 2008). Although orienting to the voice gender of the auditory distractor cannot aid identification of the target, changing the voice gender in consecutive trials reduces the CSE. Analogous findings from a unimodal visual task indicate that changing the stimulus colour in consecutive trials reduces the CSE even when this feature is completely irrelevant to identifying a relevant target (Braem, Hickey, et al., 2014). These findings suggest the possibility that, in unimodal tasks, salient perceptual features on their own—rather than task sets based on such features—serve as contextual boundaries for the CSE. However, the presence of feature integration confounds in these studies makes it difficult to determine whether salient perceptual features serve as boundaries for (a) adaptive control or (b) experimental confounds.

The present study

The goal of the present study is to distinguish between the task set and attentional reset hypotheses in a standard visual task that lacks both feature integration and contingency learning confounds. To achieve this goal, we employ a prime-probe task wherein the stimuli are colour words and colour patches (Dignath et al., 2019). In Experiment 1, the task structure allows participants to associate these distinct stimulus formats (i.e., salient perceptual features) with different task sets. Thus, both hypotheses predict a smaller CSE when the stimulus format changes than when it repeats as in Dignath et al. (2019). In Experiment 2, the task structure does not allow participants to associate these stimulus formats with different task sets. Thus, while the attentional reset hypothesis continues to predict a smaller CSE when the stimulus format changes (vs. repeats), the task set hypothesis no longer predicts such a reduction.

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we conducted a conceptual replication of Experiment 2 from Dignath et al. (2019). As we described earlier, in this experiment both hypotheses predict a smaller CSE when the stimulus format changes than when it repeats. Therefore, we reasoned that replicating this finding, which has only been reported in one prior study, would provide important information (e.g., about effect sizes) for subsequently distinguishing between the task set and attentional reset hypotheses in a second experiment.

Methods

Participants.

Prior to data collection, we registered all hypotheses, methods, and analyses on the Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://osf.io/8p5n6). As described there, we conducted a power analysis (G*Power 3.1.9.4; Faul et al., 2007) based on the three-way interaction among format transition, current trial congruency, and previous trial congruency (α = .05, ) that Dignath et al. (2019) observed in their second experiment. The results of this analysis indicated that collecting usable data from 48 participants would provide more than 95% power to observe the same interaction in the present experiment. The University of Michigan’s Behavioural Sciences Internal Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol.

Fifty-three undergraduates from the University of Michigan participated for course credit. We excluded data from a total of five participants. Four self-reported neurological disorders and/or using psychoactive medications and one performed the task with less than 75% accuracy. None of the remaining 48 participants (11 male, 37 female; 44 right-handed, 3 left-handed; 1 ambidextrous; age range: 18–23 years; mean age: 18.75 years, standard deviation of age: 1 year) reported any history of head trauma, uncorrected visual or hearing impairments, seizures, or neurological disorders. We uploaded the raw data from these 48 participants to the OSF (osf.io/354tj).

Stimuli and apparatus.

The stimuli were colour words and colour patches. As in Dignath et al. (2019), distractor colour words (Red: 3.1° × 1.6°, Blue: 3.6° × 1.6°, Green: 4.7° × 1.6°, Yellow: 5.2° × 1.6°) and distractor colour patches (RED: 1.6° × 1.6°, BLUE: 1.6° × 1.6°, GREEN: 1.6° × 1.6°, YELLOW: 1.6° × 1.6°) were larger than target colour words (Red: 2.1° × 1.0°, Blue: 2.6° × 1.0°, Green: 3.1° × 1.0°, Yellow: 3.6° × 1.0°) and target colour patches (RED: 1.0° × 1.0°, BLUE: 1.0° × 1.0°, GREEN: 1.0° × 1.0°, YELLOW: 1.0° × 1.0°), respectively. We employed the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997), a MATLAB plug-in, on three Windows PC computers to present the task stimuli and to record participants’ responses. We positioned each study participants’ eyes approximately 55 cm away from the computer screen.

Experimental design.

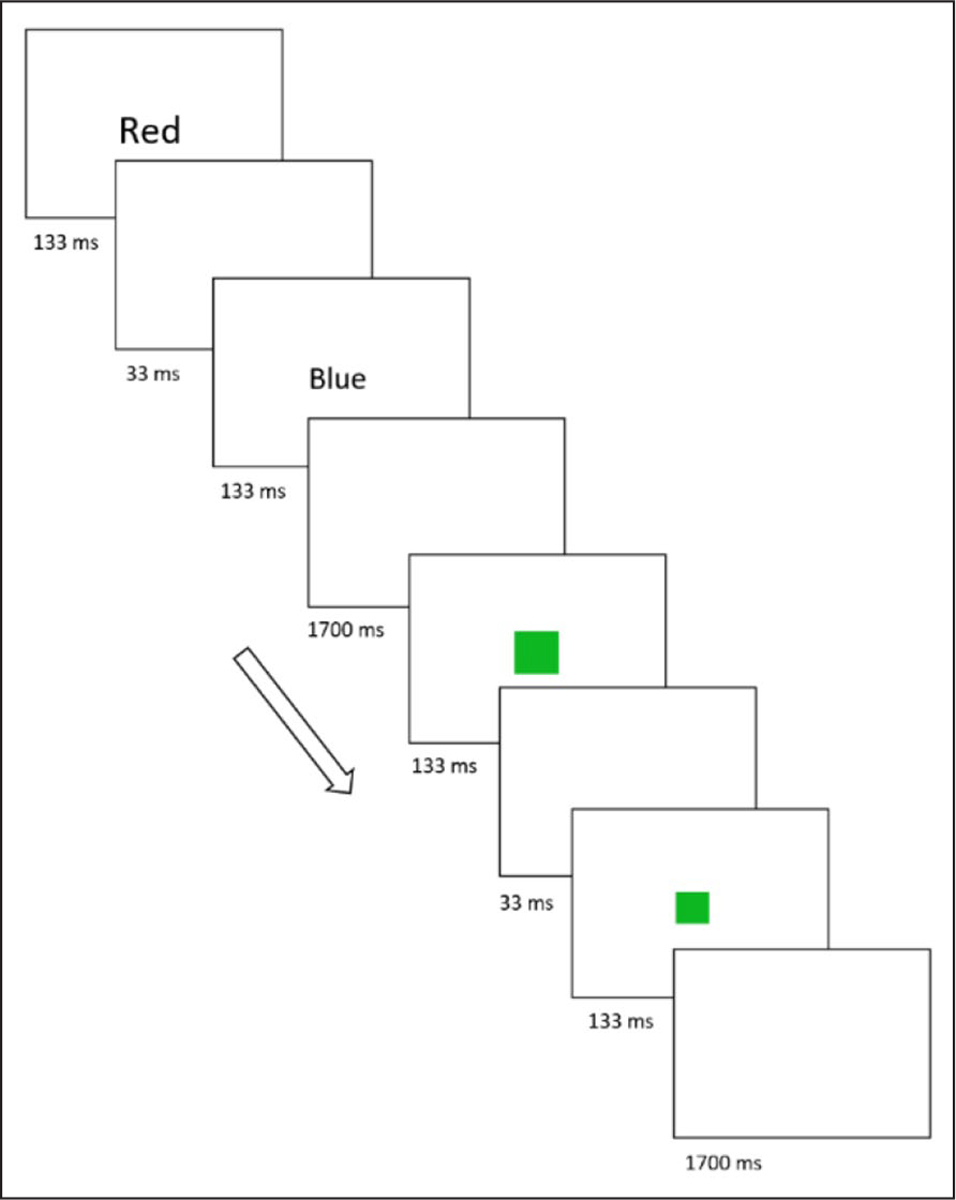

The experiment consisted of a 64-trial practice block followed by ten test blocks with 96 trials each. Each block started and ended with a 2 s fixation cross (0.48° × 0.48°). In each 2 s trial (Figure 1), there were four sequential events: (a) a distractor (duration, 133 ms), (b) a blank screen (duration, 33 ms), (c) a target (duration, 133 ms), and (d) a second blank screen (duration, 1700 ms). In half the trials, the distractor and target were colour words (red, blue, green, or yellow) while in the other half they were colour patches (red, blue, green, or yellow). All of the stimuli appeared on a black background.

Figure 1.

The prime-probe task in Experiment 1. This figure illustrates two sequential trials: an incongruent trial with colour word stimuli followed by a congruent trial with colour patch stimuli. The number beneath each box indicates the length of the corresponding trial component in milliseconds (ms). The arrow indicates the passage of time.

We created 16 distractor-target pairs (i.e., trial types). Eight consisted of colour patches and eight consisted of colour words. Within each set of eight pairs, four were congruent (red-red; blue-blue; green-green; yellow-yellow) and four were incongruent (red-blue; blue-red, green-yellow; yellow-green). Each of these pairs preceded and followed each other equally often, separately for odd and even trials. In each block, one pair appeared one less time than the other pairs since no trial preceded the first trial. However, since we created a unique trial sequence for every block, the less-frequent pair varied randomly across blocks.

To isolate adaptive control processes, we employed a confound-minimised task protocol (Schmidt & Weissman, 2014; Weissman et al., 2014, 2015). This involved creating a pair of 2-alternative-forced-choice (2-AFC) tasks: one with red and blue words and patches and one with green and yellow words and patches. To avoid feature integration (e.g., stimulus repetition) confounds (Hommel et al., 2004; Mayr et al., 2003), we presented stimuli from the red-blue task in the odd trials of each block and stimuli from the green-yellow task in even trials of each block. To avoid contingency learning (i.e., stimulus frequency) confounds, we presented the two congruent and two incongruent distractor-target pairs in each 2-AFC task equally often in every block (Schmidt & De Houwer, 2011).

Procedure.

Participants provided informed written consent prior to starting the experiment. Next, a research assistant read the task instructions to the participant. The instructions indicated that participants should respond as quickly and as accurately as possible to the second stimulus (i.e., the target) in each trial while ignoring the first stimulus (i.e., the distractor). In particular, participants were instructed to indicate whether the target was a red, blue, green, or yellow patch/word by pressing the “D” (right index finger), “F” (right middle finger), “G” (right ring finger), or “H” (right pinkie finger) key, respectively, on a QWERTY keyboard. If a participant pressed the wrong key in a given trial, or failed to respond within 1500 ms, the word “Error” appeared centrally for 200 ms.

Data analyses.

In our analyses of mean reaction time (RT), we excluded (a) practice trials, (2) the first trial of each block, (3) outliers in RT greater than 3Sn (Rousseeuw & Croux, 1993)1 from the conditional mean, (4) trials with omitted or incorrect responses (errors), and (5) trials immediately following errors. We excluded the same trial types from our analyses of mean error rate (ER) with the exception of errors, which were the dependent measure. On average, 9.9% of the trials were errors and 4.3% were outliers.

Following these exclusions, we calculated mean RT and mean ER for each trial type. We then conducted separate repeated-measures ANOVAs on mean RT and mean ER. In each ANOVA there were four within-participants factors: current trial stimulus format (colour patch, colour word), format transition (repeat, switch), previous trial congruency (congruent, incongruent), and current trial congruency (congruent, incongruent). We included current trial stimulus format as a factor only to account for the extra variance that it produced and, hence, do not report findings related to this factor. We note, however, that this factor did not influence the critical three-way interaction among format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency.

Results

Mean RT.

There were three significant effects. First, we observed a main effect of current trial congruency (i.e., a congruency effect), F(1, 47) = 345.17, p < .001, , because mean RT was longer in incongruent trials (774 ms) than in congruent trials (639 ms). Second, we observed a two-way interaction between previous trial congruency and current trial congruency (i.e., a CSE), F(1, 47) = 37.72, p < .001, , because the congruency effect was smaller after incongruent trials (120 ms) than after congruent trials (151 ms). Third, we observed an interaction among format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency, F(1, 47) = 8.41, p = .006, . As expected, the CSE was larger when the stimulus format repeated across consecutive trials, 47 ms; F(1, 47) = 32.67, p < .001, , than when the stimulus format switched, 15 ms; F(1, 47) = 5.03, p = .030, , (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The congruency sequence effect (CSE) in each of the two critical trial types of Experiment 1: format repeat trials and format switch trials. Previous trial congruency varies on the x-axis (Prev Cong: previous congruent trial; Prev Incong: previous incongruent trial). Current trial congruency varies with line type (dashed line: incongruent; black line: congruent). Reaction time (in ms) appears on the y-axis.

Error bars indicate ± 1 standard error of the mean.

Mean ER.

We observed a significant main effect of current trial congruency, F(1, 47) = 16.83, p < .001, . As expected, mean ER was higher in incongruent relative to congruent trials (8.65% vs. 5.99%). No other effects were significant.

Exploratory analysis

Frings and colleagues (2020) proposed that the influence of episodic memory on adaptive control reflects two processes: (1) binding, or encoding, distinct features within an episodic memory of the previous trial and (2) retrieving this memory in the current trial. Therefore, one may wonder whether episodic binding in the previous trial and episodic retrieval in the current trial separately influence the formation of a CSE boundary. There are two logical possibilities. First, episodic binding in the previous trial may be stronger for some perceptual features (e.g., colour words) than for others (e.g., colour patches). This view predicts a larger reduction of the CSE when the stimulus format changes if the previous trial contains a strongly (vs. weakly) bound stimulus format. That is, greater episodic binding for one stimulus format than for another in the previous trial should lead to an interaction among previous-trial stimulus format, format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency. A second possibility is that some perceptual features (e.g., colour words) serve as stronger retrieval cues for an episodic memory of the previous trial than others (e.g., colour patches). This view predicts a smaller reduction of the CSE when the stimulus format changes if the current trial contains a stimulus format that serves as a more (vs. less) effective retrieval cue. That is, greater episodic retrieval triggered by one stimulus format than by another in the current trial should lead to an interaction among current-trial stimulus format, format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency.

To explore these possibilities, we conducted two within-participants ANOVAs on mean RT. The factors in the first ANOVA were previous trial stimulus format (colour patch, colour word), format transition (repeat, switch), previous trial congruency (congruent, incongruent), and current trial congruency (congruent, incongruent). The factors in the second ANOVA were current trial format (colour patch, colour word), format transition (repeat, switch), previous trial congruency (congruent, incongruent), and current trial congruency.

The first ANOVA revealed a significant four-way interaction among previous trial stimulus format, format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency, F(1, 47) = 5.22, p = .027, . We observed this interaction because the difference in CSE magnitude between format-repeat trials and format-switch trials was larger after colour-word trials, 52 ms; F(1, 47) = 12.79, p < .001, , than after colour-patch trials (12 ms, F < 1) (see Figure 3). Follow-up analyses of the data from format-switch trials revealed that the CSE was significant after colour-patch trials, 26 ms, F(1, 47) = 8.16, p = .006, , but not after colour-word trials (4 ms, F < 1). These findings suggest that differences related to episodic binding between the two stimulus formats influenced the formation of CSE boundaries.

Figure 3.

The CSE in each of the four possible combinations of format transition (repeat, switch) and previous trial stimulus format (colour word, colour patch) in Experiment 1. Format transition varies on the x-axis. Previous trial format varies by line type. CSE Magnitude (in ms) appears on the y-axis.

Error bars indicate ± 1 standard error of the mean.

The second ANOVA did not reveal a significant four-way interaction among current trial stimulus format, format transition, previous trial congruency, current trial congruency (F < 1). Thus, there was no evidence to suggest that differences in episodic retrieval related to the two stimulus formats influenced the formation of CSE boundaries. Given that these were exploratory analyses, however, future studies should investigate the dissociation we observed in an a priori fashion.

Discussion

In line with both hypotheses, changing the stimulus format in Experiment 1 reduced the CSE. This finding replicates the key result of Dignath et al. (2019). Exploratory analyses further revealed that changing the stimulus format reduced the CSE more when colour words (vs. colour patches) appeared in the previous trial. However, it remains unclear whether task sets based on stimulus formats or stimulus formats on their own serve as boundaries for the CSE. We distinguish between these possibilities in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

The goal of Experiment 2 was to distinguish between the task set and attentional reset hypotheses. To this end, we independently varied the stimulus format (colour patch or colour word) of (a) the distractor and (b) the target. Consequently, the distractor and target in each trial were equally likely to appear in the same format (i.e., colour patch/colour patch or colour word/colour word) or in different formats (i.e., colour patch/colour word or colour word/colour patch). Under such conditions, participants cannot classify each trial as involving only colour words or only colour patches. They also cannot orient to the format of the distractor to prepare for a target that always appears in the same format. Therefore, they are unlikely to create format-specific task sets.

Critically, the task set and attentional reset hypotheses make opposing predictions. The task set hypothesis predicts that changing the stimulus format will not reduce the CSE, because the task structure prevents participants from creating format-specific task sets. In other words, participants should form a single, format-general task set and, consequently, a robust CSE should appear regardless of whether the stimulus format changes or repeats. In contrast, the attentional reset hypothesis predicts that changing the target’s stimulus format will reduce the CSE exactly as in Experiment 1. According to this hypothesis, changing the target’s stimulus format biases the system to create a new episode, which signals that previous-trial control settings are no longer relevant and, consequently, “resets” attentional processes (Kreutzfeldt et al., 2016).

Methods

Participants.

As in Experiment 1, we registered all hypotheses, methods, and analyses on the OSF (https://osf.io/mz24a) prior to data collection. To determine an appropriate sample size, we conducted a power analysis (G*Power 3.1.9.4; Faul et al., 2007) using the three-way interaction among format transition, current trial congruency, and previous trial congruency in Experiment 1 (α = .05, ). The results indicated that collecting usable data from 70 participants would provide over 90% power to observe an analogous three-way interaction among target format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency in the present experiment.2 The University of Michigan’s Behavioural Sciences IRB approved the study protocol.

Eighty-one undergraduates from the University of Michigan participated for course credit. We excluded the data from 11 participants due to computer issues (two participants) and for performing the task with less than 75% accuracy (nine participants). None of the remaining 70 participants (21 male, 49 female; 68 right-handed, 2 left-handed; age range: 18–21 years; mean age: 18.74 years, standard deviation of age: 0.88 years) reported any history of head trauma, uncorrected visual or hearing impairments, seizures, or neurological disorders. We uploaded the raw data from these 70 participants to the OSF (https://osf.io/jx74f).

Stimuli and apparatus.

The stimuli and apparatus were identical to those in Experiment 1.

Experimental design.

The experimental design was the same as that in Experiment 1 with two exceptions. First, to vary the stimulus format of (a) the distractor (colour patch, colour word) and (b) the target (colour patch, colour word) independently across trials, we created 32 (rather than 16) distractor-target pairs. Second, in each block we employed a first-order counterbalanced trial sequence in which there were four “same format” trial types (word congruent, word incongruent, patch congruent, patch incongruent) and four “different format” trial types (word-patch congruent, word-patch incongruent, patch-word congruent, and patch-word incongruent). These trial types preceded and followed each other equally often in every block—separately in odd and even trials—except for one that appeared one time less because no trial preceded the first trial of each block. Finally, as in Experiment 1, we created a different trial sequence for every block, separately for each participant.

Procedure.

The procedure was the same as in Experiment 1 with one exception. The experiment consisted of a 64-trial practice block followed by five 128-trial (versus ten 64-trial) test blocks. We inserted a rest break halfway through each block to equate the number and frequency of rest breaks to those in Experiment 1.

Data analyses.

We excluded the same trials from our analyses as in Experiment 1. On average, 11.4% of the trials were errors and 2.6% were outliers. Following these exclusions, we calculated mean RT and mean ER for each trial type. We then conducted separate repeated-measures ANOVAs on mean RT and mean ER. In each ANOVA, there were four within-participants factors: distractor format transition (repeat, switch), target format transition (repeat, switch), previous trial congruency (congruent, incongruent) and current trial congruency (congruent, incongruent).

Results

Mean RT.

We observed two significant main effects. First, we observed a main effect of previous trial congruency, F(1, 69) = 7.70, p = .007, , because mean RT was longer after incongruent trials (661 ms) than after congruent trials (657 ms). This “post-conflict” slowing is commonly observed in distractor-interference tasks and likely reflects slower response times following conflict to reduce the possibility of making an erroneous response (Ullsperger et al., 2005; Verguts et al., 2011). Second, we observed a main effect of current trial congruency, F(1, 69) = 419.31, p < .001, , because mean RT was longer in incongruent trials (704 ms) than in congruent trials (613 ms).

We also observed a pair of significant interactions. First, we observed an interaction between target format transition and previous trial congruency, F(1, 69) = 8.30, p = .005, . Although mean RT was always longer after incongruent (vs. congruent) trials, this effect was larger when the target format switched across consecutive trials, 7 ms; F(1, 69) = 14.6, p < .001, , than when it repeated (1 ms; F < 1). Second, we observed an interaction between previous trial congruency and current trial congruency (i.e., a CSE), F(1, 69) = 80.60, p < .001, . As expected, the congruency effect was smaller after incongruent trials, 78 ms; F(1, 69) = 320.0, p < .001, , than after congruent trials, 103 ms; F(1,69) = 436.0, p < .001, .

No other effects were significant including the three-way interactions among distractor format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency (F < 1) and target format transition, previous trial congruency, and current trial congruency (F < 1). The four-way interaction was also not significant, F(1, 69) = 1.82, p = .18, ).3 Indeed, the CSE was similarly robust when both formats repeated (30 ms), only the distractor’s format repeated (22 ms), only the target’s format repeated (24 ms), and when neither the distractor’s format nor the target’s format repeated (28 ms) (all four p values < 0.001; see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The congruency sequence effect (CSE) in each of the four possible combinations of distractor format transition (repeat, switch) and target format transition (repeat, switch) in Experiment 2. Previous trial congruency varies on the x-axis (Prev Cong: previous congruent trial; Prev Incong: previous incongruent trial). Current trial congruency varies by line type (Dashed line: incongruent; Black line: congruent). Reaction time (in ms) appears on the y-axis.

Error bars indicate ± 1 standard error of the mean.

Mean ER.

We observed two significant main effects. First, we observed a main effect of previous trial congruency, F(1, 69) = 8.21, p = .006, , because mean ER (a) was lower after incongruent trials (8.0%) than after congruent trials (8.7%). Second, we observed a main effect of current trial congruency, F(1, 69) = 37.16, p < .001, , because mean ER was lower in congruent trials (7.0%) than in incongruent trials (9.7%). No other effects were significant.

Exploratory across-experiment comparisons

Our results thus far support the task set hypothesis: changing the stimulus format reduces the CSE only when the task structure allows participants to create format-specific task sets (i.e., in Experiment 1 but not Experiment 2). As a further test of this hypothesis, we explored whether changing the stimulus format reduced the CSE more in Experiment 1 than in Experiment 2.

Specifically, we conducted a mixed ANOVA on mean RT wherein Experiment (1, 2) served as the across-participants factor and current trial stimulus format (colour patch, colour word), format transition (repeat, switch), previous trial congruency (congruent, incongruent), and current trial congruency (congruent, incongruent) served as the within-participants factors.4 To facilitate this across-experiment comparison, we employed the same trial types as in Experiment 1. Critically, we observed a significant four-way interaction, F(1,116) = 4.69, p = .032, (see Figure 5). Consistent with the task set hypothesis, changing the stimulus format from one trial to the next reduced the CSE more in Experiment 1 (32 ms) than in Experiment 2 (−1 ms).

Figure 5.

Across-experiment analysis. Whether the format of the distractor and target both repeated or both switched varies on the x-axis, separately for Experiment 1 (dotted line) and Experiment 2 (dashed line). The y-axis plots CSE magnitude (in ms) in each of these four conditions.

At first glance, these findings provide further support for the task-set hypothesis. However, an alternative interpretation is that across-experiment differences in processing demands led to a larger CSE boundary in Experiment 1 than in Experiment 2. Specifically, independently varying the formats of the distractor and target in Experiment 2 may have led participants to recruit greater cognitive control (and/or working memory) than in Experiment 1. To test this possibility, we conducted a second exploratory analysis to investigate across-experiment differences in overall reaction time, overall error rate, and the congruency effect. We reasoned that if cognitive control and/or working memory requirements were higher in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1, then overall mean RT should be longer and overall mean ER should be higher in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1. Further, the congruency effect should be larger in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1, because increasing processing demands on working memory increases the interference from irrelevant stimuli (Lavie et al., 2004).

Contrary to this view, overall mean RT was shorter (rather than longer) in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1, 706 ms vs. 659 ms; t(116) = 2.97, p = .004, Cohen’s d = 0.56, and overall mean ER did not differ between the two experiments (p > .20). Further, the congruency effect in mean RT was smaller (rather than larger) in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1, 135 ms vs. 90 ms; t(116) = 5.66, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.06; this effect did not appear in the mean ER data, t(116) = − 0.013, p = .99. In line with the task-set hypothesis, these findings suggest that processing demands were lower when the task structure biased participants to create a single, format-general task set in Experiment 2 than when the task structure biased participants to create different, format-specific task sets (and, therefore, engage in multitasking) in Experiment 1.

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 favour the task set hypothesis over the attentional reset hypothesis. Specifically, unlike in Experiment 1, alternating the target’s stimulus format across consecutive trials did not reduce the CSE. These findings suggest that participants perceived colour words and colour patches as belonging to the same task set in Experiment 2 rather than to separate task sets as in Experiment 1. In line with this view, the exploratory analyses further revealed that changing the target’s stimulus format reduced the CSE less in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1. These findings suggest that task sets based on stimulus formats, rather than stimulus formats on their own, serve as boundaries for the CSE in standard visual tasks.

The perceived task-relevance of the distractor’s stimulus format may influence whether participants create format-specific task sets or a format-general task set. In Experiment 1, the distractor’s format (e.g., colour patch) matched the upcoming target’s format (e.g., colour patch) in every trial. Thus, participants could orient attention to the distractor’s relevant (i.e., predictive) stimulus format to prepare for the upcoming target (Grant et al., 2020). In Experiment 2, however, the distractor’s format (e.g., colour patch) matched the upcoming target’s format in only half of the trials. Thus, participants could not consistently orient attention to the distractor’s irrelevant (i.e., non-predictive) stimulus format to prepare for the upcoming target. In sum, the perceived task-relevance of the distractor’s stimulus format may influence whether participants associate different stimulus formats with the same task set or with different task sets.

General discussion

We sought to distinguish between the task set and attentional reset accounts of contextual boundaries for the CSE in a purely visual task. To this end, we employed a prime-probe task wherein participants could (in Experiment 1) or could not (in Experiment 2) use distinct stimulus formats (i.e., colour patches and colour words) to create format-specific task sets. Consistent with the task set hypothesis, but not with the attentional reset hypothesis, we found that changing the stimulus format reduced the CSE only when participants could create format-specific task sets (i.e., only in Experiment 1). As we describe next, these findings have important implications for our understanding of the contextual boundaries that limit the scope of adaptive control.

Implications for the task set hypothesis

The present findings extend prior data indicating that task sets serve as boundaries for the confound-minimised CSE in a cross-modal task (Grant et al., 2020) to a unimodal visual task. This is important because researchers employ unimodal tasks to investigate the boundaries of adaptive control far more often than they employ cross-modal tasks. Thus, the present findings reveal the nature of CSE boundaries under conditions that are more typical in the literature.

Our findings also speak to the idea that distinct visual features on their own are not sufficiently “salient” to trigger task set formation (Hazeltine et al., 2011, Experiment 2). Hazeltine et al. argued that the task instructions must map the stimuli associated with distinct features to fingers on different hands in order for those features to serve as task set boundaries for the CSE. Doing so makes the features informative regarding the hand participants should use to respond and, hence, sufficiently “salient” (i.e., distinct) to trigger task set formation. Contrary to this view, we found that participants are able to form distinct task sets related to distinct visual features if a task maps the stimuli associated with those features to the same fingers. This discrepancy may indicate that the visual features that allow participants to distinguish between different subsets of stimuli are more salient in the present task (i.e., colour patches and colour words) than in Hazeltine et al.’s task (i.e., central letters and peripheral circles). It may also reflect our use of a confound-minimised protocol or greater statistical power in the present study due to the larger sample size that we employed (i.e., 48 participants vs. 16 participants).

In line with the possibility that some visual features are more salient than others, the results of the exploratory analyses in Experiment 1 suggest that colour words are more strongly bound in a memory of the previous trial than colour patches, resulting in a larger task set boundary for the CSE. This outcome fits with an emerging view wherein episodic binding and episodic retrieval make separable contributions to adaptive control (Frings et al., 2020). It also suggests the possibility that visual features vary on a continuum of salience, such that task set boundaries for the CSE are easier to create (or observe) for some features than for others. Future studies could investigate what determines whether the visual features that distinguish between different subsets of trials are salient enough to trigger task set formation.

Future studies could also investigate whether orienting attention to the distractor’s stimulus format triggers task set formation in the task we employed in Experiment 1, analogous to the manner in which orienting attention to the distractor’s sensory modality triggers task set formation in cross-modal tasks (e.g., Grant et al., 2020, Experiment 1). To investigate this possibility, researchers could employ a study design that is analogous to Experiment 3 in Grant et al.’s (2020) cross-modal study with the exception that the stimuli are colour patches and colour words in the visual modality, rather than directional words in the visual and auditory modalities. The distractor’s format would predict the upcoming target’s format about 90% of the time (format valid trials) but not the rest of the time (format invalid trials).

If participants orient attention to the distractor’s format to prepare for an upcoming target in the same format, then they should respond more slowly in format invalid trials than in format valid trials. Moreover, this format validity effect should be larger than in a design like that of the present Experiment 2, wherein participants are unlikely to orient attention to the distractor’s format because it does not consistently predict the target’s format. Finally, one should observe format-specific CSEs, although these might be small given the presence of mixed-format trials that discourage orienting to some degree. Consistent with these predictions, we reported exactly analogous effects in our cross-modal tasks (Grant et al., 2020). Most important, observing such effects in a purely visual task would suggest that orienting attention to the stimulus properties of a distractor is a relatively general mechanism for triggering task set formation.

Implications for the attentional reset hypothesis

The present data do not support the attentional reset hypothesis, but it remains possible that boundaries for the CSE in other tasks reflect an attentional reset. This may explain, for example, why changing the gender (male or female) of a spoken auditory distractor word reduces the CSE even though orienting attention to voice gender cannot facilitate the identification of a gender-neutral target (a high- or low-pitched tone) (Spapé & Hommel, 2008). This may also explain why changing irrelevant stimulus colours reduces the CSE even when identifying a target requires attention to a different feature (i.e., stimulus format) (Braem, Hickey, et al., 2014). Alternatively, these findings may indicate that participants create format-specific task sets even when orienting attention to the perceptual features of the distractor cannot facilitate the identification of the target. To resolve this ambiguity, future researchers could attempt to distinguish between the attentional reset and task set hypotheses in tasks like those above.

It is also possible that Garner interference (Algom & Fitousi, 2016; Fitousi, 2016; Garner, 1974) contributes to the formation of CSE boundaries in tasks like those above. Garner interference indexes the inability to ignore variation along an irrelevant stimulus dimension, leading to response slowing that is independent of semantic and response conflict (Algom & Fitousi, 2016). Critically, minimising Garner interference may require control resources that overlap with those that produce a CSE (c.f., Egner, 2008). If so, then the CSE boundaries above may have appeared because control resources were recruited to minimise Garner interference rather than to produce a CSE. Future studies could investigate this potential explanation.

Implications for views wherein adaptive control is dimension-specific

The results of Experiment 2 contradict a central assumption of the conflict-monitoring model (Botvinick et al., 2001; Egner, 2014), which is that adaptive control processes are specific to the task-relevant stimulus dimension. Specifically, we observed a robust CSE even when the task-relevant stimulus dimension changed (i.e., from colour patches to colour words, or vice-versa). Since the conflict-monitoring model is highly influential in the literature on adaptive control, this outcome may appear surprising. Recent data from other confound-minimised tasks, however, further suggest the possibility that the conflict-monitoring model cannot fully explain the CSE.

For example, the size of the CSE in the prime-probe task does not vary with whether there is a large congruency effect in mean RT or no congruency effect at all (Weissman et al., 2015) even though, in the latter case, conflict is unlikely to differ between congruent and incongruent trials (Yeung et al., 2011). Further, when there is no overall congruency effect, the CSE is associated with a positive congruency effect after congruent trials and with a negative, or reverse, congruency effect after incongruent trials (i.e., faster mean RT in incongruent trials than in congruent trials). A reverse congruency effect is consistent with models wherein control processes modulate (e.g., inhibit) the response cued by the distractor after incongruent trials (Ridderinkhof, 2002). However, it does not fit with the conflict-monitoring model wherein control processes shift attention towards the target and away from the distractor after incongruent relative to congruent trials (Botvinick et al., 2001). Indeed, even shifting all of one’s attention away from the distractor could eliminate the congruency effect but not reverse it. The present findings, therefore, add to a growing body of data indicating that the conflict-monitoring model does not provide an adequate explanation of the CSE in the prime-probe task.

The results of Experiment 2 also inform inhibitory views of the CSE wherein adaptive control processes are specific to the task-irrelevant (i.e., distractor) stimulus dimension (Kim et al., 2015; Lee & Cho, 2013). Specifically, the size of the CSE did not vary with whether the distractor’s stimulus format repeated or switched in consecutive trials. Given prior findings indicating that a modulation (e.g., inhibition) of the response cued by the distractor contributes to the CSE (Ridderinkhof, 2002; Stürmer et al., 2002; Weissman et al., 2015), we do not reject the claim that the CSE indexes a modulation of response activation. However, as we explain next, this modulation may occur more strongly when the task set that underlies performance specifies the format in which the distractor appears (Grant et al., 2020).

Specifically, our view is as follows. When participants create format-specific task sets, as in the present Experiment 1, they create separate task sets for stimuli that appear in different stimulus formats (e.g., colour words and colour patches). Each task set includes information about stimuli that appear in just a single stimulus format (e.g., colour word or colour patch). The current-trial distractor must therefore appear in the previous-trial stimulus format to trigger the retrieval of the previous trial’s event file. Consequently, control processes modulate the response cued by the current-trial distractor, thereby engendering a CSE, only if its stimulus format matches the stimulus format of the previous trial. In contrast, when participants create a format-general task set, as in the present Experiment 2, they form a single task set for colour words and colour patches. This task set includes information about both stimulus formats (i.e., colour word and colour patch). The current-trial distractor can therefore appear in either format to trigger the retrieval of the previous trial’s event file. Hence, control processes modulate the response cued by the distractor, thereby engendering a CSE, regardless of whether its stimulus format matches or mismatches the stimulus format of the previous trial. To test this view, future studies could use force-sensitive keys to determine whether task sets serve as boundaries for finger-specific modulations of response activation that occur after the distractor appears (Weissman, 2019).

Finally, one may wonder how our findings relate to other data suggesting that task-relevant stimulus dimensions do not serve as task set boundaries for the CSE (Kim et al., 2015; Lim & Cho, 2021). Consider Experiment 1 of Kim et al. (2015), wherein the task (Stroop or Simon) alternated on every trial. Here, the task-relevant dimension differed between the Stroop (word) and Simon (colour) tasks while the task-irrelevant dimension remained the same (arrow). The authors observed a CSE and, therefore, concluded that the CSE is specific to the task-irrelevant dimension (arrow), rather than to the task-relevant dimension (i.e., word or colour). In other words, they concluded that changing the task-relevant dimension does not reduce the CSE. This conclusion may appear inconsistent with the task set hypothesis and with our findings in the present Experiment 1, wherein we observed a significant reduction of the CSE when the task-relevant dimension changed across consecutive trials.

These two sets of findings, however, are consistent with each other and with the task set hypothesis when viewed from the perspective of task set formation based on the task-irrelevant dimension. In Experiment 1 of Kim et al. (2015), the task-irrelevant dimension was an arrow in both word (Stroop) and colour (Simon) trials. Thus, participants could not use this dimension to predict whether the task-relevant dimension would be a “word” or a “colour.” For this reason, they were unlikely to create format-specific task sets. In Experiment 1 of the present study, however, the format of the task-irrelevant dimension (“colour word” or “color patch”) predicted the format of the task-relevant dimension. Thus, participants could use the distractor’s stimulus format to categorise each trial as “color word” or “color patch” and to create format-specific task sets (i.e., by orienting attention to the distractor’s stimulus format to prepare for a target in the same format). From this perspective, the present findings do not contradict the view that task-irrelevant stimulus dimensions play an important role in determining CSE boundaries (Kim et al., 2015; Lim & Cho, 2021). They simply suggest that task sets based on task-irrelevant dimensions, rather than such dimensions on their own, determine the boundaries of the CSE.

Implications for our understanding of “domain-general” adaptive control

The present finding that task sets—rather than stimulus dimensions—determine the scope of adaptive control speaks to a paradox in the literature on adaptive control. As we described earlier, most studies report an elimination of the CSE when salient perceptual features, or even entire tasks, change across trials (Braem, Hickey, et al., 2014; Dignath et al., 2019; Kiesel et al., 2006; Spapé & Hommel, 2008). However, a growing minority report robust CSEs effects even when stimuli and tasks change radically (Adler et al., 2020; Hsu & Novick, 2016; Kan et al., 2013). For instance, experiencing conflict during a sentence-reading or perceptual task reduces interference during a subsequent Stroop task (e.g., Kan et al., 2013).

The literature offers two potential explanations for such “domain-general” CSEs, the first of which appears consistent with the episodic retrieval view. First, domain-general CSEs may occur if the boundary between two tasks is not very salient, leading to the creation of a single task set (Hazeltine et al., 2011) (e.g., if the task structure biases participants to categorise sentence-reading trials and colour-naming Stroop trials as part of the same overall task). Since participants form only a single task set in this situation, the repetition of any previous-trial feature in the current trial—including the task-set (Egner, 2014; Frings et al., 2020)—triggers the retrieval of the previous trial’s event file and engenders a CSE. Second, domain-general CSEs may appear when participants can simultaneously maintain two task sets in working memory, because the two task sets are so different that they do not interfere with each other (Braem, Abrahamse, et al., 2014). According to this view, simultaneously maintaining two task sets in working memory allows adaptive control processes to transfer from one task set to another.

In our view, the present findings motivate an account of domain-general CSEs wherein participants associate different perceptual features with the same task set. However, they do not rule out the alternative working memory hypothesis described above. Future studies could investigate this hypothesis by determining whether participants simultaneously maintain non-interfering task sets in working memory. If they do, then taxing the working memory processes that maintain either task set should reduce or eliminate domain-general CSEs (c.f., Soutschek et al., 2013).

Limitations

The present study has two limitations. First, although we argued that participants switched between format-specific task sets in Experiment 1, we did not observe an effect of format transition—or task switch costs—in either the mean RT or the mean ER data. In the absence of such switch costs, the overall analyses do not provide independent evidence that participants formed distinct, format-specific task sets in Experiment 1. Future studies could investigate whether such evidence appears in other tasks. Regardless of the outcome, the present findings show that task structure influences whether or not salient perceptual features serve as boundaries for the CSE, which is highly consistent with the task set hypothesis.

Two factors may account for the absence of switch costs in the present study. First, to avoid feature integration confounds, we did not permit stimuli and/or responses to repeat across consecutive trials. The absence of such repetitions may reduce the extent to which participants retrieve an irrelevant task set in task switch trials (Frings et al., 2020; Kiesel et al., 2010) and thereby reduce task switch costs (Schmidt & Liefooghe, 2016). Consistent with this view, relatively weak (or absent) task-switch costs have been observed in several recent studies of the confound-minimised CSE (Dignath et al., 2019; Grant et al., 2020). Second, as in Dignath et al. (2019), participants used conceptually overlapping S-R mappings in colour-patch and colour-word trials (i.e., they pressed the same key for a given colour word—e.g., red—and the conceptually related colour patch—e.g., red). Thus, the two task sets may have been less distinct than in typical task-switching paradigms (Cookson et al., 2016, 2020), further reducing task switch costs.

Second, our findings do not indicate why task sets serve as partial boundaries for the CSE in some studies but as complete boundaries in others. Specifically, while some researchers report a reduced—but still significant—CSE when the task set changes (e.g., Dignath et al., 2019, Experiment 1), others report the complete absence of a CSE (e.g., Kiesel et al., 2006; Kreutzfeldt et al., 2016). One possibility is that the manner in which task sets are stored in episodic memory influences whether they serve as partial or complete boundaries for the CSE. Along these lines, task sets may serve as partial boundaries if they are stored in independent, binary bindings with other features (Hommel, 1998, 2007; Huffman et al., 2020). According to this view, repeating a feature from the previous trial could trigger the retrieval of the task set from that trial even if the current trial involves a different task set. Alternatively, task sets may serve as complete boundaries for the CSE if they are stored at the top level of a hierarchical task representation (Kleinsorge & Heuer, 1999; Schumacher & Hazeltine, 2016). Here, switching between high-level task sets could alter the effects of lower-level feature repetitions on performance (Altmann, 2011; Rogers & Monsell, 1995), resulting in the complete absence of a CSE. Future studies could distinguish between these theoretically interesting possibilities.

Conclusion

The present findings indicate that task sets based on salient perceptual features, rather than such features on their own, serve as boundaries for the CSE in a visual distractor-interference task. They also suggest that task set boundaries for the CSE are easier to observe for some visual features than for others. These findings extend an emerging episodic retrieval view of the CSE while posing a challenge to views wherein adaptive control processes are specific to the task-relevant stimulus dimension. They also further motivate a task set account of “domain-general” CSEs. Future work investigating the potentially separable contributions of stimulus salience, episodic binding (in the previous trial), and episodic retrieval (in the current trial) to task set formation may provide additional insights into the boundaries of adaptive control.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrea Dai, Cathryn Goldman, Ceren Ege, Al-Amin Ali, Alexis Salinas, Jiaxu Li, Kristina Lyons, and Daphne Samuel for assisting with data collection.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Programme under Grant No. (DGE1256260). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

We employed a robust estimator of scale called Sn to identify outliers in RT because of its relatively low type I and type II error rates relative to other estimators of scale (e.g., standard deviation; Jones, 2019).

In our preregistration, we proposed to examine only the four-way interaction. However, examining the three-way interaction provides a more specific test of the view that adaptive control processes are specific to the task-relevant stimulus dimension (Kreutzfeldt et al., 2016). It is also more consistent with our use of the three-way interaction from Experiment 1 to guide the power analysis.

Exploratory analyses revealed that this four-way interaction remained non-significant (F < 1) when we included only the same trial types as in Experiment 1, wherein the distractor and target always appeared in the same format.

To ensure we were comparing the same trial types in the across-experiment comparison, we analysed only the trials wherein the distractor and target appeared in the same stimulus format (i.e., both words or both patches). Also, as in Experiment 1, we analysed current trial stimulus format only to account for the variance this factor produced.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data accessibility statement

The data from the present experiment are publicly available at the Open Science Framework website: osf.io/354tj and osf.io/jx74f

References

- Adler RM, Valdés Kroff JR, & Novick JM (2020). Does integrating a code-switch during comprehension engage cognitive control? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 46(4), 741–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algom D, & Fitousi D (2016). Half a century of research on Garner interference and the separability–integrality distinction. Psychological Bulletin, 142(12), 1352–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann EM (2011). Testing probability matching and episodic retrieval accounts of response repetition effects in task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37(4), 935–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, & Cohen JD (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braem S, Abrahamse EL, Duthoo W, & Notebaert W (2014). What determines the specificity of conflict adaptation? A review, critical analysis, and proposed synthesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braem S, Hickey C, Duthoo W, & Notebaert W (2014). Reward determines the context-sensitivity of cognitive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40(5), 1769–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH (1997). The psychophysics toolbox. Spatial Vision, 10, 433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson SL, Hazeltine E, & Schumacher EH (2016). Neural representation of stimulus-response associations during task preparation. Brain Research, 1648, 496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson SL, Hazeltine E, & Schumacher EH (2020). Task structure boundaries affect response preparation. Psychological Research, 84, 1610–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignath D, Johannsen L, Hommel B, & Kiesel A (2019). Reconciling cognitive-control and episodic-retrieval accounts of sequential conflict modulation: Binding of control-states into event-files. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 45, 1265–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T (2008). Multiple conflict-driven control mechanisms in the human brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(10), 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T (2014). Creatures of habit (and control): A multi-level learning perspective on the modulation of congruency effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen BA, & Eriksen CW (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 16, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW, & Schultz DW (1979). Information processing in visual search: A continuous flow conception and experimental results. Perception & Psychophysics, 25, 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, & Buchner A (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavioral Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitousi D (2016). Simon and Garner effects with color and location: Evidence for two independent routes by which irrelevant location influences performance. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78(8), 2433–2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings C, Hommel B, Koch I, Rothermund K, Dignath D, Giesen C, Kiesel A, Kunde W, Mayr S, Moeller B, Möller M, Pfister R, & Philipp A (2020). Binding and Retrieval in Action Control (BRAC). Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24, 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner WR (1974). The stimulus in information processing. In Sensation and measurement (pp. 77–90). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Grant LD, Cookson SL, & Weissman DH (2020). Task sets serve as boundaries for the congruency sequence effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 46(8), 798–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MGH, & Donchin E (1992). Optimizing the use of information: Strategic control of activation of responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 121, 480–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazeltine E, Lightman E, Schwarb H, & Schumacher EH (2011). The boundaries of sequential modulations: Evidence for set-level control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37(6), 1898–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B (1998). Event files: Evidence for automatic integration of stimulus-response episodes. Visual Cognition, 5(1–2), 183–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B (2004). Event files: Feature binding in and across perception and action. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(11), 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B (2007). Feature integration across perception and action: Event files affect response choice. Psychological Research, 71(1), 42–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B, Proctor RW, & Vu KP (2004). A feature-integration account of sequential effects in the Simon task. Psychological Research, 68, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu NS, & Novick JM (2016). Dynamic engagement of cognitive control modulates recovery from misinterpretation during real-time language processing. Psychological Science, 27(4), 572–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman G, Hilchey MD, Weidler BJ, Mills M, & Pratt J (2020). Does feature-based attention play a role in the episodic retrieval of event files? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 46(3), 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez L, & Méndez A (2014). Even with time, conflict adaptation is not made of expectancies. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PR (2019). A note on detecting statistical outliers in psychophysical data. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81, 1189–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan IP, Teubner-Rhodes S, Drummey AB, Nutile L, Krupa L, & Novick JM (2013). To adapt or not to adapt: The question of domain-general cognitive control. Cognition, 129(3), 637–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesel A, Kunde W, & Hoffmann J (2006). Evidence for task-specific resolution of response conflict. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesel A, Steinhauser M, Wendt M, Falkenstein M, Jost K, Philipp AM, & Koch I (2010). Control and interference in task switching—A review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 849–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, & Cho YS (2014). Congruency sequence effect without feature integration and contingency learning. Acta Psychologica, 149, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee SH, & Cho YS (2015). Control processes through the suppression of the automatic response activation triggered by task-irrelevant information in the Simon-type tasks. Acta Psychologica, 162, 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinsorge T, & Heuer H (1999). Hierarchical switching in a multi-dimensional task space. Psychological Research, 62(4), 300–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kornblum S, Hasbroucq T, & Osman A (1990). Dimensional overlap: Cognitive basis for stimulus-response compatibility—A model and taxonomy. Psychological Review, 97(2), 253–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzfeldt M, Stephan DN, Willmes K, & Koch I (2016). Shifts in target modality cause attentional reset: Evidence from sequential modulation of crossmodal congruency effects. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23, 1466–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunde W, & Wühr P (2006). Sequential modulations of correspondence effects across spatial dimensions and tasks. Memory & Cognition, 34(2), 356–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie N, Hirst A, De Fockert JW, & Viding E (2004). Load theory of selective attention and cognitive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(3), 339–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, & Cho YS (2013). Congruency sequence effect in cross-task context: Evidence for dimension-specific modulation. Acta Psychologica, 144(3), 617–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CE, & Cho YS (2021). Response mode modulates the congruency sequence effect in spatial conflict tasks: Evidence from aimed-movement responses. Psychological Research, 85(5), 2047–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr U, Awh E, & Laurey P (2003). Conflict adaptation effects in the absence of executive control. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 450–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, & Cohen JD (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notebaert W, & Verguts T (2008). Cognitive control acts locally. Cognition, 106(2), 1071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof RK (2002). Micro-and macro-adjustments of task set: Activation and suppression in conflict tasks. Psychological Research, 66(4), 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RD, & Monsell S (1995). Costs of a predictible switch between simple cognitive tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 124(2), 207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw PJ, & Croux C (1993). Alternatives to the median absolute deviation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88(424), 1273–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JR, & De Houwer J (2011). Now you see it, now you don’t: Controlling for contingencies and stimulus repetitions eliminates the Gratton effect. Acta Psychologica, 138, 176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JR, & Liefooghe B (2016). Feature integration and task switching: Diminished switch costs after controlling for stimulus, response, and cue repetitions. PLOS ONE, 11(3), Article e0151188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JR, & Weissman DH (2014). Congruency sequence effects without feature integration or contingency learning confounds. PLOS ONE, 9(7), Article e102337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher EH, & Hazeltine E (2016). Hierarchical Task Representation: Task files and Response Selection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Simon JR, & Rudell AP (1967). Auditory S-R compatibility: The effect of an irrelevant cue on information processing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 51, 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutschek A, Strobach T, & Schubert T (2013). Working memory demands modulate cognitive control in the Stroop paradigm. Psychological Research, 77(3), 333–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spapé MM, & Hommel B (2008). He said, she said: Episodic retrieval induces conflict adaptation in an auditory Stroop task. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(6), 1117–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürmer B, Leuthold H, Soetens E, Schröter H, & Sommer W (2002). Control over location-based response activation in the Simon task: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 28(6), 1345–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger M, Bylsma LM, & Botvinick MM (2005). The conflict adaptation effect: It’s not just priming. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 5(4), 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verguts T, Notebaert W, Kunde W, & Wühr P (2011). Post-conflict slowing: Cognitive adaptation after conflict processing. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(1), 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DH (2019). Let your fingers do the walking: Finger force distinguishes competing accounts of the congruency sequence effect. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26(5), 1619–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DH, Egner T, Hawks Z, & Link J (2015). The congruency sequence effect emerges when the distracter precedes the target. Acta Psychologica, 156, 8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DH, Hawks ZW, & Egner T (2016). Different levels of learning interact to shape the congruency sequence effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 42(4), 566–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DH, Jiang J, & Egner T (2014). Determinants of congruency sequence effects without learning and memory confounds. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40(5), 2022–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wühr P, Duthoo W, & Notebaert W (2015). Generalizing attentional control across dimensions and tasks: Evidence from transfer of proportion-congruent effects. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68(4), 779–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung N, Cohen JD, & Botvinick MM (2011). Errors of interpretation and modeling: A reply to Grinband et al. NeuroImage, 57(2), 316–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the present experiment are publicly available at the Open Science Framework website: osf.io/354tj and osf.io/jx74f