Abstract

Background:

Racial/ethnic inequities in mother's milk provision for hospitalized preterm infants persist. The extent to which primary language contributes to these racial/ethnic inequities is unknown.

Objective:

Examine associations of maternal race/ethnicity and primary language with (1) any/exclusive mother's milk at hospital discharge and (2) the time to cessation of mother's milk provision during the hospitalization.

Methods:

We examined 652 mother/very-low-birthweight (VLBW) infant dyads at 9 level 3 neonatal intensive care units in Massachusetts from January 2017 to December 2018. We abstracted maternal race/ethnicity and language from medical records, and examined English and non-English-speaking non-Hispanic White (NHW), non-Hispanic Black (NHB), and Hispanic mothers of any race. We examined associations of race/ethnicity and language with (1) any/exclusive mother's milk at discharge (yes/no) using mixed-effects logistic regression and (2) cessation of mother's milk during the hospitalization using cox proportional hazard models, adjusting for gestational age, birthweight, and accounting for clustering by plurality and hospital.

Results:

Fifty-three percent were English-speaking NHW, 22% English-speaking NHB, 4% non-English-speaking NHB, 14% English-speaking Hispanic, and 7% non-English-speaking Hispanic. Compared with English-speaking NHW, NHB mothers (English adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.28 [0.17, 0.44]; and non-English-speaking aOR 0.55 [0.19, 0.98]), and non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers (aOR 0.29 [0.21, 0.87]) had lower odds of any mother's milk at discharge. In time-to-event analyses, non-English-speaking Hispanic (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 4.37 [2.20, 6.02]) and English-speaking NHB mothers (aHR 3.91 [1.41, 7.61] had the earliest cessation of mother's milk provision.

Conclusion:

In Massachusetts, maternal primary language was associated with inequities in mother's milk provision for VLBW infants with a differential effect for NHB and Hispanic mothers.

Keywords: language disparities, breastfeeding, very-low-birthweight infants, neonatal intensive care unit

Introduction

Very-low-birthweight (VLBW infants; ≤1500 g) are at substantially higher risk of chronic health problems and neurodevelopmental disabilities compared with term infants.1 It is well established that the duration of mother's milk provision during the birth hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is associated with reduced risk of multiple prematurity-related morbidities.2–5 While the rate of provision of mother's milk in the United States has increased in the last decade, racial/ethnic inequities persist.6 Similarly, in Massachusetts, our statewide neonatal quality collaborative previously reported stark racial/ethnic inequities in continuation of mother's milk provision throughout the NICU hospitalization, whereby Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black (NHB) mothers were significantly more likely to cease providing milk to their infants sooner than their non-Hispanic White (NHW) counterparts.7 Our results contrast with the findings in other U.S. states like California8 in that in our cohort, Hispanic mothers had the largest differences in milk provision.7

Understanding the key contributing factors that underlie the observed racial/ethnic inequities in mother's milk provision is needed to devise and implement tailored interventions. Because the majority of non-English-speaking adults in Massachusetts are Hispanic, we hypothesized that maternal language could be associated with the large Hispanic/White difference observed in our state, and potentially also the Black/White difference. However, the relationship between maternal non-English primary language and breastfeeding in the preterm population is complex. On one hand, non-English primary language may serve as a proxy for social and cultural norms that are often positively and strongly associated with breastfeeding.9 On the other hand, breastfeeding among mothers of preterm infants imposes unique challenges (i.e., pump dependence, delayed lactogenesis)10; and language barriers may hinder the intensive breastfeeding support practices that are needed to establish milk provision in the NICU.11

Finally, non-English primary language in the United States often coexists with adverse socioeconomic factors (i.e., poverty, transportation difficulties),12 which may prevent non-English-speaking mothers from being present in the NICU, where breastfeeding support practices such as skin-to-skin occur.11 The extent that non-English primary language contributes to racial and ethnic differences in provision of mother's milk among the high-risk VLBW population has not been investigated.

To date, literature examining inequities in breastfeeding among the VLBW population has primarily focused on race and ethnicity. This approach is partly due to limitations of existing datasets of perinatal health outcomes. For instance, the Vermont Oxford Network (VON), the largest quality benchmarking organization for NICUs that care for VLBW infants, only collects race/ethnicity as a social factor.13 Large data registries like the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative (CPQCC) additionally capture variables such as income and education, but lack maternal language.14 Other national surveillance data systems such as the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) are limited to English and Spanish,15 thereby impeding examination of outcomes of underrepresented mothers that speak an array of other languages. These datasets are all limited to data collection on breastfeeding among VLBW infants at single time points (at discharge for VON and CPQCC, and initiation and the time of the interview for PRAMS).

In light of previous research gaps, we leveraged a statewide cohort of hospitalized VLBW infants with data collection on maternal race/ethnicity, primary language, and measures of provision of mother's milk over several time points. We aimed to examine the extent that maternal race/ethnicity and primary language are associated with any and exclusive mother's milk at NICU discharge; and to compare the time to cessation of mother's milk provision throughout the NICU hospitalization among racial/ethnic and language groups. We hypothesized that non-English-speaking NHB and Hispanic mothers would be less likely to provide their own milk to their infants at hospital discharge compared with English-speaking NHW mothers. We also hypothesized that, within NHB and Hispanic groups, having non-English (vs. English) as primary language would be associated with earlier discontinuation of mother's milk provision during the NICU hospitalization.

Methods

Study population and setting

This study is a secondary analysis of a cohort of mother/VLBW infant dyads included in the Human Milk Neonatal Quality Improvement Collaborative (NeoQIC) from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2018 across 9 level 3 NICUs with birth centers in Massachusetts.16 This statewide collaborative aimed to reduce disparities in mother's milk provision among mothers of VLBW infants (≤1500 g or <30 weeks of gestation at birth). We excluded infants who died (n = 51), infants with missing discharge information (n = 10), those ineligible to receive their mother's milk (n = 40), and those missing data on maternal race/ethnicity (n = 82) or primary language (n = 70). Furthermore, we excluded mothers of Asian (n = 30), American Indian Alaska Native (n = 5), and other race (n = 25) as these small sample sizes precluded stratified analyses by maternal primary language and NHW mothers who did not speak English (n = 8), leaving 652 mother/VLBW infant dyads for analysis. We refer to breastfeeding people as mothers; however, we acknowledge that people who breastfeed may identify with any gender.

The Institutional Review Board at Boston Medical Center/Boston University deemed this study as nonhuman subjects' research.

Exposure variables

Maternal race/ethnicity and primary language were abstracted from the medical records at participating hospitals. Racial/ethnic groups were categorized as NHW, NHB, and Hispanic of any race; and then each racial/ethnic group was further stratified by primary language (English vs. non-English) resulting in five groups: English-speaking NHW (NHW hereafter), English-speaking NHB, non-English-speaking NHB, English-speaking Hispanic, and non-English-speaking Hispanic. Among Black mothers, non-English languages included Haitian Creole (n = 13), Cape Verdean Creole (n = 10), other (n = 7), and Spanish (n = 1). Among Hispanic mothers, non-English languages included Spanish (n = 43) and Portuguese (n = 1).

Outcome variables

Mother's milk provision

Infant feeding information was abstracted from the medical records on days of life 7, 14, 21, 28, 42, 56, 70, 84, and then in the 24 hours before discharge or transfer. We examined mother's milk provision at these time points among infants that received any feedings (infants that were NPO at any of these individual time points were excluded for analysis at that time point). Outcomes for mother's milk provision included exclusive mother's milk, which was defined as 100% of “base” milk from the mother, with or without any fortifier (human or bovine); and any mother's milk, which was defined as any amount of mother's milk, with or without the addition of donor human milk, formula, and/or any fortifier. Mother's milk was considered initiated if the infant received any mother's milk on day of life 7.

Hospital breastfeeding support practices

Local hospital teams collected data on four breastfeeding hospital support practices. These hospital practices included categorical measures of: (1) prenatal education regarding human milk benefits as documented in prenatal consultation notes by neonatal physicians or nurse practitioners among mothers that received a prenatal consultation; (2) first milk expression within 6 hours after birth, either by hand expression or by pumping; (3) lactation consultation by board-certified lactation consultant within 24 hours after birth; and (4) any skin-to-skin care documented at any time during four audit days (day of life 7, 14, 21, or 28).

Covariates

Continuous covariates included infant gestational age, birthweight, and length of stay. Categorical covariates included birth hospital and plurality.

Statistical analyses

First, we examined differences in infant characteristics and mother's milk provision according to maternal race/ethnicity and primary language groups using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Then, we used mixed effects logistic regression models to examine associations between racial/ethnic and language groups (NHW as reference) with (1) any and exclusive mother's milk at day of life 7, 28, and at NICU discharge and (2) the four hospital breastfeeding support practices outlined above. We adjusted models for infant gestational age and birthweight and included plurality and birth hospital as random effects. The random effect for hospital was included to account for correlation between mothers within a given hospital who may receive similar care practices that may influence outcomes. In models examining mother's milk provision at discharge, we additionally adjusted for length of hospital stay because the duration of the infant's hospitalization influences opportunities for mother's milk provision. We present odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Then, among mothers who initiated provision of their milk, we performed Cox proportional hazards models17 to compare the time to discontinuation of mother's milk over the course of the NICU hospitalization among groups. Models were adjusted for infant gestational age and birthweight, clustering by plurality and hospital. We compared all five groups having NHW mothers as reference because this group had the highest rates of milk provision. We also performed within-group analyses separately for NHB and Hispanic mothers stratified by primary language having English-speaking mothers as reference. We present hazard ratios and 95% CIs and Kaplan–Meier plots to illustrate these differences.

Results

Among the 652 mother/VLBW dyads included in this study, 348 (53.4%) were NHW, 143 (21.9%) were English-speaking NHB, 27 (4.2%) were non-English-speaking NHB, 90 (13.8%) were English-speaking Hispanic, and 44 (6.8%) were non-English-speaking Hispanic (Table 1). VLBW infants in this statewide cohort had a mean birthweight of 1109.6 ± 292 g and a mean gestational age of 28.8 ± 2.7 weeks. Mean hospital stay duration was 44.4 ± 4 days.

Table 1.

Infant and Mother Characteristics According to Maternal Race/Ethnicity and Primary Language Group

| Characteristics | All subjects N = 652 | NHW |

NHB |

Hispanic |

p a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English N = 348 | English N = 143 | Non-English N = 27 | English N = 90 | Non-English N = 44 | |||||||||

| Infant characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Birthweight, grams, mean (SD) | 1109.6 | 292 | 1131.1 | 289.8 | 1068.9 | 308.8 | 996.1 | 282.2 | 1098.4 | 271.3 | 1165 | 272.8 | 0.03 |

| Gestational age, week, mean (SD) | 28.8 | 2.7 | 28.9 | 2.6 | 28.5 | 2.8 | 29.3 | 2.7 | 28.8 | 2.9 | 28.8 | 2.5 | 0.53 |

| Birthweight for gestational age z score, mean (SD) | −0.5 | 1.1 | −0.5 | 1.0 | −0.5 | 1.3 | −1.1 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 1.0 | −0.3 | 1.1 | 0.03 |

| Discharge weight for gestational age z score, mean (SD) | −0.9 | 1.8 | −1.0 | 1.1 | −0.9 | 1.3 | −1.5 | 1.8 | −0.7 | 3.6 | −1.1 | 1.3 | 0.37 |

| Weight z change from birth to initial disposition, mean (SD) | −0.4 | 1.5 | −0.5 | 0.7 | −0.4 | 0.7 | −0.4 | 1.5 | −0.1 | 3.5 | −0.8 | 0.9 | 0.24 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 338 | 51.8 | 186 | 53.5 | 72 | 50.4 | 18 | 66.7 | 43 | 47.8 | 19 | 43.2 | 0.67 |

| Multiple gestation, n (%) | 187 | 28.7 | 106 | 30.5 | 34 | 23.8 | 13 | 48.2 | 22 | 24.4 | 12 | 27.3 | 0.09 |

| Initial disposition transfer (vs home), n (%) | 231 | 35.4 | 132 | 37.9 | 40 | 28.0 | 14 | 51.9 | 29 | 32.2 | 16 | 36.4 | 0.09 |

| Length of stay, d, mean (SD) | 44.4 | 4.4 | 44.9 | 4.4 | 44.7 | 4.7 | 42.2 | 3.6 | 43.4 | 3.8 | 43.6 | 4.0 | 0.004 |

| Mother's milk provision at specific time points, n (%) | |||||||||||||

| Day 7 any mother's milk | 501 | 82.7 | 275 | 84.1 | 101 | 77.7 | 19 | 86.4 | 69 | 82.1 | 37 | 86.1 | 0.51 |

| Day 7 exclusive mother's milk | 375 | 61.9 | 219 | 67.0 | 75 | 57.7 | 11 | 50.0 | 50 | 59.5 | 22 | 51.2 | 0.048 |

| Day 28 any mother's milk | 401 | 79.4 | 222 | 85.1 | 89 | 73.6 | 13 | 76.5 | 49 | 68.1 | 23 | 67.6 | 0.04 |

| Day 28 exclusive mother's milk | 321 | 63.6 | 189 | 72.4 | 66 | 54.6 | 9 | 52.9 | 41 | 56.9 | 18 | 52.9 | 0.001 |

| Discharge/transfer any mother's milk | 393 | 61.7 | 255 | 74.2 | 60 | 44.1 | 14 | 53.8 | 52 | 58.4 | 17 | 39.5 | <0.001 |

| Discharge/transfer exclusive mother's milk | 290 | 45.5 | 193 | 56.1 | 41 | 30.2 | 8 | 30.8 | 38 | 42.7 | 15 | 35.7 | <0.001 |

| Hospital support practices, n (%) | |||||||||||||

| Prenatal consultation with education on human milk benefitsb | 206 | 76.3 | 91 | 71.1 | 55 | 75.3 | 11 | 68.8 | 30 | 88.2 | 15 | 83.3 | 0.05 |

| First milk expression within 6 hours | 321 | 60.7 | 186 | 66.4 | 71 | 56.8 | 6 | 30.0 | 37 | 52.1 | 21 | 63.6 | 0.005 |

| First lactation visit within 24 hours | 213 | 70.1 | 109 | 74.2 | 56 | 65.1 | 14 | 73.7 | 21 | 67.7 | 13 | 61.9 | 0.55 |

| Any skin-to-skin with the mother on day 7, 14, 21, or 28 | 293 | 44.9 | 174 | 50.0 | 58 | 40.6 | 14 | 51.6 | 41 | 45.6 | 13 | 29.5 | <0.001 |

ANOVA was used for continuous variables and the chi-squared test was used for categorical variables.

The denominator for prenatal consultation with education regarding human milk benefits is the 270 VLBW infants whose mothers received prenatal consultation. Bold indicates p < 0.5.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; NHB, non-Hispanic Black; NHW, non-Hispanic White; SD, standard deviation; VLBW, very-low-birthweight.

In adjusted models examining the associations of maternal race/ethnicity and primary language with provision of mother's milk at specific time points (Table 2), we found no difference in initiation of mother's milk across groups. However, compared with NHW mothers, English-speaking NHB mothers had lower adjusted odds of any and exclusive mother's milk provision on day 28, and NHB mothers of any language had lower odds of any and exclusive mother's milk provision at hospital discharge. Compared with NHW mothers, non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers had lower odds of any and exclusive mother's milk both on day 28 and at hospital discharge. Regarding hospital practices, compared with NHW mothers, non-English-speaking NHB mothers were less likely to have their first milk expression within 6 hours of birth while non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers were less likely to perform any skin-to-skin on audited days during the first month of life.

Table 2.

Associations of Maternal Race/Ethnicity and Primary Language with Mother's Milk Provision and with Receipt of Hospital Support Practices (English-Speaking Non-Hispanic White as Reference, n = 348)

| NHB |

Hispanic |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English n = 143 | Non-English n = 27 | English n = 90 | Non-English n = 44 | |

| Mother's milk provision at specific time points | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) |

| Day 7 any mother's milk | 0.61 (0.36–1.04) | 1.27 (0.35–4.62) | 0.87 (0.45–1.66) | 1.10 (0.43–2.83) |

| Day 7 exclusive mother's milk | 0.64 (0.40–1.00) | 0.53 (0.20–1.40) | 0.89 (0.43–1.83) | 0.54 (0.32–1.01) |

| Day 28 any mother's milk | 0.51 (0.30–0.88) | 1.58 (0.33–7.59) | 0.59 (0.31–1.13) | 0.42 (0.18–0.92) |

| Day 28 exclusive mother's milk | 0.37 (0.23–0.60) | 0.41 (0.14–1.20) | 0.52 (0.24–1.12) | 0.35 (0.20–0.62) |

| Discharge/transfer any mother's milka | 0.28 (0.17–0.44) | 0.55 (0.19–0.98) | 0.63 (0.24–1.00) | 0.29 (0.21–0.87) |

| Discharge/transfer exclusive mother's milka | 0.30 (0.18–0.48) | 0.34 (0.14–0.84) | 0.59 (0.30–1.16) | 0.47 (0.22–0.73) |

| Hospital support practices | ||||

| Prenatal consultation with education on human milk benefits | 0.91 (0.42–1.98) | 0.54 (0.14–2.07) | 4.43 (0.92–21.3) | 6.24 (0.74–52.59) |

| First milk expression within 6 hours | 0.66 (0.44–1.03) | 0.23 (0.08–0.64) | 0.54 (0.32–1.00) | 0.90 (0.42–1.94) |

| First lactation visit within 24 hours | 0.71 (0.38–1.30) | 1.03 (0.32–3.30) | 0.87 (0.36–2.11) | 0.69 (0.25–1.95) |

| Any skin-to-skin with the mother on day 7, 14, 21, or 28 | 0.81 (0.52–1.22) | 1.39 (0.56–2.43) | 0.97 (0.58–1.63) | 0.66 (0.32–0.89) |

Models adjusted for gestational age, birthweight, and clustering by plurality and hospital. Infants that were NPO at each time point were excluded in the respective models (day 7, 4.3%; day 28, 2.6%; discharge/transfer, 2.3%).

Additional adjustment for length of stay. Bold indicates p < 0.5.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

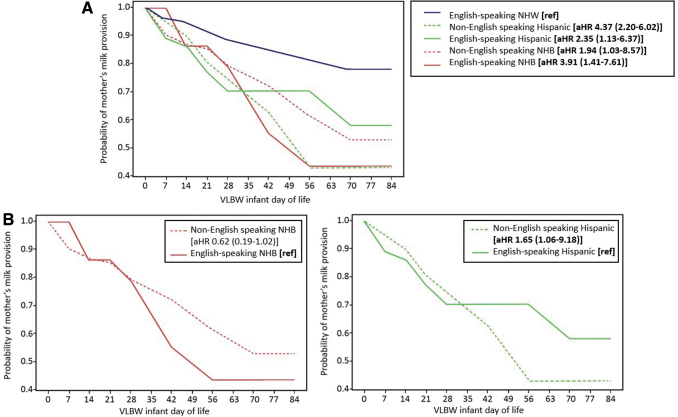

Figure 1 illustrates differences in the time to cessation of mother's milk provision over the course of the NICU hospitalization by race/ethnicity and language groups. We found that non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 4.37; 95% CI: 2.20–6.02), and English-speaking NHB mothers (aHR: 3.91; 95% CI: 1.41–7.61) had the earliest cessation of mother's milk provision. In within-group time-to-event analyses among Hispanic mothers only, we found that non-English-speaking mothers stopped providing their milk to their infants earlier than English-speaking mothers (aHR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.06–9.18). Conversely, among NHB mothers, we observed a trend toward earlier cessation in milk provision for English-speaking compared with non-English-speaking mothers (aHR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.19–1.02), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

FIG. 1.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier plots representing discontinuation of mother's milk provision during the NICU hospitalization by race/ethnicity and primary language groups. The analysis included 610 infants who received mother's milk by day 7. HRs are adjusted for infant birthweight, gestational age, and clustering by plurality and hospital. (A) Between-group differences (English-speaking NHW mothers as reference). (B) Within-group differences (English-speaking mothers as reference). Bold indicates p < 0.05. HRs, hazard ratios; NHB, Non-Hispanic Black, NHW, Non-Hispanic White; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Discussion

In line with previous reports,7,18,19 racial/ethnic inequities in continuation of mother's milk provision in this cohort of mother-VLBW infant dyads unfolded over the course of the prolonged NICU hospitalization. NHB and Hispanic mothers provided their milk to their infants for a shorter duration compared to NHW mothers. Adding to the extant literature, we found a differential influence of maternal primary language among racial and ethnic minority mothers in Massachusetts. Non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers had substantially lower rates of any mother's milk at hospital discharge compared with English-speaking Hispanic mothers; whereas non-English-speaking NHB mothers had higher rates of any mother's milk at hospital discharge compared with English-speaking NHB mothers. These findings underscore the important heterogeneity that exists among racial/ethnic groups in the United States and the need to better understand the complex interplay of cultural and social determinants of breastfeeding in the NICU setting to achieve breastfeeding equity.

Race/ethnicity is a social construct and racial/ethnic inequities in health outcomes, including breastfeeding, are thus rooted in social and cultural factors.20 Our study—which studied the influence of language as one such factor that may partly explain racial/ethnic inequities in breastfeeding—revealed important differences within the Hispanic and NHB communities in our state. We hypothesize that primary language influenced breastfeeding findings for the Hispanic and NHB groups in multiple ways. First, non-English primary language may serve as a proxy for cultural norms and attitudes toward breastfeeding. Second, non-English language may be associated with lower socioeconomic status (i.e., lower income and educational attainment), which is associated with lower breastfeeding rates in the United States.20 Third, non-English language may signal communication barriers that prevent mothers from interacting with hospital staff who provide breastfeeding support.

Regarding Hispanic mothers of VLBW infants, our findings differ from national studies of Hispanic mothers of term infants, where rates of breastfeeding were higher for Spanish-speaking compared with English-speaking mothers.21 Our results also differ from a recent California study, which showed that Hispanic mothers of VLBW infants, 51% of whom were foreign born, had the highest breastfeeding rates.8 Foreign-born mothers are more likely to speak a language other than English, and the cultural norms associated with country of birth are known contributors to breastfeeding.22 We, therefore, hypothesize that our findings for non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers may be influenced by the cultural makeup of Hispanic mothers in our state. Hispanic mothers in Massachusetts are primarily of Puerto Rican and Dominican origin,23 and these groups have historically had lower breastfeeding rates. In comparison, Hispanic mothers of Mexican or South American ancestry, who live more frequently in other areas of the United States, such as California, have historically had higher breastfeeding rates.24

Additionally, our results may be partly explained by high rates of poverty or near poverty among non-English-speaking Hispanics in Massachusetts.25 Mothers of VLBW infants living in poverty face substantial challenges for continuing milk provision because of systemic barriers to NICU visitation11 (i.e., childcare, transportation, and need for early return to work after childbirth) that limit exposure to breastfeeding promoting practices such as skin-to-skin.7 In support of this hypothesis, non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers in our cohort had significantly lower rates of any skin-to-skin during the first month of life compared with NHW mothers.

Furthermore, the observed low breastfeeding rates at NICU discharge among non-English-speaking Hispanic mothers in our cohort may be related to suboptimal quality of breastfeeding support from NICU staff due to language barriers. Despite national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care,26 emerging studies in the NICU demonstrate that the quality of care varies substantially by caregiver primary language.11,27,28 Sirgurdson et al categorized care to non-English-speaking families as “neglectful,” whereby non-English speakers received less quality care than English speakers11; Palau et al showed that interpreters were used only 39% of the time to communicate with Spanish-speaking families in the NICU.28 In the NICU, mothers rely heavily on the technological expertise and support of NICU professionals for establishing and maintaining milk production with a pump,10 as opposed to mothers of healthy-term infants who may rely on support from family and friends to assist with lactation. Thus, it is possible that language barriers and other social determinants affected ongoing delivery of lactation support for non-English-speaking Hispanics in our cohort.

Regarding NHB mothers, our findings of higher rates of breastfeeding continuation among non-English compared with English-speaking NHB mothers may be influenced by both facilitators of breastfeeding among non-English-speaking NHB mothers as well as barriers to breastfeeding among English-speaking NHB mothers. Cultural factors may have played an important role. In a cohort of U.S.-born and foreign-born Black mothers of term infants, Safon et al found that despite lower socioeconomic status and educational attainment, odds of breastfeeding were seven-fold higher among foreign-born than U.S.-born Black mothers; and these findings were partly mediated by strongly positive attitudes and social norms toward breastfeeding.29 Because foreign-born mothers are more likely to have non-English as their primary language, similar positive cultural norms may have contributed to higher rates of milk provision among non-English-speaking NHB mothers in our cohort.

Qualitative work with U.S.-born English-speaking Black mothers has also identified that breastfeeding is often not a normative behavior in this population, in part, due to historical factors and traumas that have been generationally passed down and integrated into Black families in the United States.30 We hypothesize that early cessation of milk provision among English-speaking NHB mothers of VLBW infants may be related to structural, interpersonal, or institutional racism,31 as well as health care provider bias and discrimination.32–34 More research in this area is needed to inform family-centered and culturally relevant strategies to advance breastfeeding equity in the United States.

Strengths of our study include the examination of primary language, in addition to race/ethnicity as a social determinant of mother's milk provision for VLBW infants using a diverse, statewide cohort. We also had measurements of milk provision over several time points of the NICU hospitalization, enabling a richer understanding of the changes in cessation of mother's milk provision over time. This contrasts to most existing literature, which is limited to measurements of mother's milk for VLBW infants at the point of discharge only, which underestimates the extent to which infants may have received mother's milk during the course of the entire hospitalization. Limitations of this study include the lack of data on other important factors, such as nativity and sociodemographic characteristics, neighborhood-level factors, mother's perceived experiences of discrimination or cultural beliefs and intentions to breastfeed. We also did not have other detailed data about the medical morbidities of the infant, pump type and frequency, use of interpreters, or mothers' frequency of visiting the NICU and interacting with lactation support professionals over time.

Further population-level studies, including a broader array of social and cultural factors are needed to inform the development of interventions to equitably support breastfeeding continuation among mothers of VLBW infants.

Conclusions

In this Massachusetts cohort, we found a different and opposite effect of language on mother's milk provision among NHB and Hispanic mothers in Massachusetts, highlighting the vast heterogeneity within racial/ethnic minority groups in our state. Among Hispanic mothers, non-English vs. English-speaking mothers had lower rates of milk provision. Among Black mothers, non-English vs. English-speaking NHB mothers had higher rates of milk provision. These differences likely reflect the complex interplay of social and cultural factors that influence continuation of mother's milk provision among underrepresented minority mothers of VLBW infants. At a minimum, state and national datasets should capture maternal language data. Tracking breastfeeding outcomes by maternal language status can serve to identify and address disparities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of local hospitals that participated in the NeoQIC Human Milk Quality Improvement Collaborative, who contributed data for this project.

Authors' Contributions

E.G.C.-R.: conceptualization (lead), formal analysis (lead), writing—original draft (lead). P.M.: data curation (lead), methodology (lead), formal analysis (supporting); writing—review and editing (equal). N.S.K.: writing—review and editing (equal). M.-M.P.: writing—review and editing (equal). M.B.B.: writing—review and editing (equal). M.G.P.: Conceptualization (lead); Writing—original draft (supporting); Writing—review and editing (equal).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Dr. E.G.C.-R. is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through BU-CTSI Grant Number 1KL2TR001411.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. (Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds.) National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2007, National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson TJ, Patel AL, Bigger HR, et al. Cost savings of human milk as a strategy to reduce the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Neonatology 2015;107(4):271–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel AL, Johnson TJ, Engstrom JL, et al. Impact of early human milk on sepsis and health-care costs in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 2013;33(7):514–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel AL, Johnson TJ, Robin B, et al. Influence of own mother's milk on bronchopulmonary dysplasia and costs. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102(3):F256–f261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lechner BE, Vohr BR. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed human milk: A systematic review. Clin Perinatol 2017;44(1):69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parker MG, Greenberg LT, Edwards EM, et al. National trends in the provision of human milk at hospital discharge among very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173(10):961–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parker MG, Gupta M, Melvin P, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mother's milk feeding for very low birth weight infants in Massachusetts. J Pediatr 2019;204:134–141.e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu J, Parker MG, Lu T, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in human milk intake at neonatal intensive care unit discharge among very low birth weight infants in California. J Pediatr 2020;218:49–56.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hohl S, Thompson B, Escareño M, et al. Cultural norms in conflict: breastfeeding among hispanic immigrants in rural Washington State. Matern Child Health J 2016;20(7):1549–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, et al. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics 2003;112(3 Pt 1):607–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sigurdson K, Morton C, Mitchell B, et al. Disparities in NICU quality of care: A qualitative study of family and clinician accounts. J Perinatol 2018;38(5):600–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cordova-Ramos EG, Tripodis Y, Garg A, et al. Linguistic disparities in child health and presence of a medical home among United States Latino children. Acad Pediatr 2021;22(5):736–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vermont Oxford Network. Manual of Operations. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gould JB. The role of regional collaboratives: The California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative model. Clin Perinatol 2010;37(1):71–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shulman HB, D'Angelo DV, Harrison L, et al. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Overview of design and methodology. Am J Public Health 2018;108(10):1305–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parker MG, Burnham LA, Melvin P, et al. Addressing disparities in mother's milk for VLBW infants through statewide quality improvement. Pediatrics 2019;144(1):e20183809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee ET, Go OT. Survival analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health 1997;18:105–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pineda RG. Predictors of breastfeeding and breastmilk feeding among very low birth weight infants. Breastfeed Med 2011;6(1):15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoban R, Bigger H, Patel AL, et al. Goals for human milk feeding in mothers of very low birth weight infants: How do goals change and are they achieved during the NICU hospitalization? Breastfeed Med 2015;10(6):305–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Standish KR, Parker MG. Social determinants of breastfeeding in the United States. Clin Ther 2022;44(2):186–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKinney CO, Hahn-Holbrook J, Chase-Lansdale PL, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2016;138(2):e20152388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Provini LE, Corwin MJ, Geller NL, et al. Differences in infant care practices and smoking among hispanic mothers living in the United States. J Pediatr 2017;182:321–326.e321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. U.S. Census Bureau. American Factfinder. Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010. Census Summary File 1: Massachusetts (QT-P10). Available from: https://archive.ph/20200213010024/https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/DEC/10_SF1/QTP10/0400000US25#selection-263.0-263.32 [Last accessed February 14, 2022].

- 24. Pew Research Center. Demographics and Economic Profiles of Hispanics by State and Country, California 2014. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/states/state/ca [Last accessed February 21, 2022].

- 25. Pew Research Center. Demographics and Economic Profiles of Hispanics by State and Country, Massachusetts 2014. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/states/state/ma [Last accessed February 14, 2022].

- 26. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. Available at https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas [Last accessed June 22, 2022].

- 27. Kalluri NS, Melvin P, Belfort MB, et al. Maternal language disparities in neonatal intensive care unit outcomes. J Perinatol 2022;42(6):723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palau MA, Meier MR, Brinton JT, et al. The impact of parental primary language on communication in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 2019;39(2):307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Safon CB, Heeren TC, Kerr SM, et al. Disparities in breastfeeding among U.S. black mothers: Identification of mechanisms. Breastfeed Med 2021;16(2):140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DeVane-Johnson S, Giscombe CW, Williams R, 2nd, et al. A qualitative study of social, cultural, and historical influences on African American women's infant-feeding practices. J Perinat Educ 2018;27(2):71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Witt RE, Malcolm M, Colvin BN, et al. Racism and quality of neonatal intensive care: Voices of black mothers. Pediatrics 2022;150(3):e2022056971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robinson K, Fial A, Hanson L. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health 2019;64(6):734–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Racial segregation and inequality in the neonatal intensive care unit for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173(5):455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adams SY, Davis TW, Lechner BE. Perspectives on race and medicine in the NICU. Pediatrics 2021;147(3):e2020029025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]