Abstract

Background and aims

Fentanyl is primarily responsible for the current phase of the overdose epidemic in North America. Despite the benefits of treatment with medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), there are limited data on the association between fentanyl, MOUD type and treatment engagement. The objectives of this analysis were to measure the impact of baseline fentanyl exposure on initiation and discontinuation of MOUD among individuals with prescription-type opioid use disorder (POUD).

Design, setting and participants

Secondary analysis of a Canadian multi-site randomized pragmatic trial conducted between 2017 and 2020. Of the 269 randomized participants, 65.4% were male, 67.3% self-identified as white and 55.4% had a positive fentanyl urine drug test (UDT) at baseline. Fentanyl-exposed participants were more likely to be younger, to self-identify as nonwhite, to be unemployed or homeless and to be currently using stimulants than non-fentanyl-exposed participants.

Interventions

Flexible take-home dosing buprenorphine/naloxone or supervised methadone models of care for 24 weeks.

Measurements

Outcomes were (1) MOUD initiation and (2) time to (a) assigned and (b) overall MOUD discontinuation. Independent variables were baseline fentanyl UDT (predictor) and assigned MOUD (effect modifier).

Findings

Overall, 209 participants (77.7%) initiated MOUD. In unadjusted analyses, fentanyl exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of treatment initiation [odds ratio (OR) = 0.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.08–0.36] and shorter median times in assigned [20 versus 168 days, hazard ratio (HR) = 3.61, 95% CI = 2.52–5.17] and any MOUD (27 versus 168 days, HR = 3.32, 95% CI = 2.30–4.80). The negative effects were no longer statistically significant in adjusted models, and no interaction between fentanyl and MOUD was observed for any of the outcomes (all P > 0.05).

Conclusions

Both buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone may be appropriate treatment options for people with prescription-type opioid use disorder regardless of fentanyl exposure. Other characteristics of fentanyl-exposed individuals appear to be driving the association with poorer treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, clinical trial, fentanyl, methadone, opioid use disorder, prescription opioids

INTRODUCTION

Canada and the United States continue to face a devastating opioid overdose epidemic. While the beginning of the opioid crisis was largely attributed to over-prescription and non-medical use of pharmaceutical opioids, in more recent years there has been a transition with illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids, in particular fentanyl, becoming the main drivers of this epidemic [1]. In 2020, illicitly manufactured fentanyl contributed to more than 80% of opioid-related overdose fatalities in both countries [2, 3].

Initiation and long-term retention on medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is the recommended first-line treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), as it is associated with improved outcomes compared with psychosocial treatment alone or treatments of shorter duration [4]. In particular, engagement in MOUD has been associated with a two- to threefold risk reduction in all-cause and overdose mortality [5, 6]. Unfortunately, early dropout from MOUD is common. For example, studies document that approximately 40% of individuals initiating methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone (the most frequently used MOUD) discontinue treatment within the first 6 months [7, 8], with even higher discontinuation rates for extended-release naltrexone [9].

Although several studies have demonstrated improved retention rates with methadone compared to buprenorphine/naloxone [7, 10, 11], this relative advantage of methadone has not been observed among individuals with prescription-type OUD (POUD) [12], or when optimal doses of both medications were utilized among people with OUD whose substance of choice was heroin [11]. However, the quality of evidence for populations with POUD is low [12]. In addition, most studies have been conducted in the United States, and pre-date the upsurge of fentanyl in the street drug market [7, 11, 12]. Fentanyl may also differentially affect initiation on methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone. In particular, given buprenorphine’s high affinity to the μ-opioid receptor but partial agonist properties, when used in the context of another opioid with weaker binding affinity but high potency and lipophilic characteristics such as fentanyl [13] it can displace it, precipitating withdrawal. However, research on potential fentanyl-related induction challenges is also scant.

Given the rise of fentanyl in the illicit drug supply across North America, the resultant opioid overdose crisis and the limited evidence available to guide MOUD choice in this high-risk population, there is an urgent need to prospectively evaluate the impacts of fentanyl on MOUD engagement and whether these varied by type of MOUD. Understanding these differences is important because, due to different safety and tolerability profiles, these two medications are offered through very different models of care, with buprenorphine/naloxone generally offered for take-home dosing and methadone often provided via witnessed daily ingestion. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to assess the impact of fentanyl use on (1) MOUD initiation and (2) MOUD discontinuation, as well whether the assigned MOUD moderated these associations among individuals with POUD initiating methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone as part of a pan-Canadian pragmatic clinical trial.

METHODS

Design

OPTIMA (Optimizing Patient Centered-Care: A Pragmatic Randomized Control Trial Comparing Models of Care in the Management of Prescription Opioid Misuse) was a multi-site Phase IV open-label two-arm pragmatic parallel randomized controlled trial that evaluated the relative effectiveness of buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone models of care among individuals with POUD in four Canadian provinces between October 2017 and July 2020 [14, 15]. OPTIMA’s primary outcome was the proportion of opioid-free urine drug screens (UDS) over 24 weeks, with retention in the assigned treatment as a key secondary outcome. Research Ethic Boards at participating sites approved the study, and the study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03033732). Although the initial focus of OPTIMA was prescription-type opioids, given the rise of fentanyl in the unregulated drug supply during the conduct of the trial, this secondary analysis evaluated the effects of fentanyl exposure on MOUD initiation and discontinuation. This research question was not included in the original trial protocol and the analysis was not pre-registered. The findings must therefore be regarded as exploratory.

Participants

Full eligibility criteria have been described previously [14, 15]. In brief, the main eligibility criteria included adults (aged 18–64 years) meeting criteria for OUD attributed to prescription-type opioids (e.g. licit or illicit, prescribed or not, including opioid analgesics and fentanyl) and interested in receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone. Individuals who self-reported heroin as their most frequent opioid or were enrolled in treatment with MOUD in the 30 days prior to screening, those with unstable psychiatric or medical conditions precluding safe participation, those who were pregnant or breastfeeding or who were planning to conceived were not eligible for the study.

Procedures/interventions

After providing informed consent and completing baseline questionnaires and urine drug testing (UDT), eligible participants from seven addiction community-based clinics across Canada were randomized at a 1:1 ratio to receive 24 weeks of buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone as per local standard of care. Randomization was stratified by site and life-time (ever) heroin use. The study allowed for a 14-day window to initiate their assigned MOUD, given that some participants may have not been physiologically ready to start treatment at the time of randomization (e.g. need for a period of opioid abstinence for induction into buprenorphine). Despite this window, some participants may have failed to initiate treatment altogether. Both medications were prescribed in accordance with provincial and national recommendations for the management of OUD [4]. Typically, these guidelines suggest that methadone be dispensed through daily witnessed ingestion with a target dose of 60–120 mg/day, and take-home doses permitted after 2 to 3 months. Conversely, for buprenorphine/naloxone, guidelines allow take-home doses at the physician’s discretion as soon as the patient is clinically stable, with a maximum daily dose that should not typically exceed 24/6 mg. Given the pragmatic nature of the trial, induction procedures, initial and maintenance doses and titration speed, as well as ancillary medications and supports, varied according to clinical judgement and the site’s practices. Similarly, reflecting real-world practice, after treatment initiation participants were allowed to switch to other MOUD if clinically indicated.

Once treatment was initiated, participants attended bi-weekly study visits throughout the 24-week duration of the study, during which they completed UDT and interviewer-administered questionnaires. Baseline and follow-up assessments elicited information on demographics, substance use patterns, medical and psychiatric comorbidities [e.g. depression, anxiety, pain, HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV)], health-care utilization, quality of life, criminal activity, medication dispensation and dose and adverse events. UDT were analyzed using a Rapid Response™ multi-drug one step screen test panel that tested for presence of morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, benzodiazepines, cocaine, amphetamine, Δ−9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), buprenorphine and methadone, and single test strips for hydromorphone and 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM).

Analysis population

For this analysis we considered all eligible OPTIMA participants who were randomized and had valid baseline UDT results for fentanyl (positive or negative).

Measures

Our primary outcomes were (1) MOUD initiation and (2) MOUD discontinuation, defined using information that was abstracted from participants’ electronic medical records or pharmacy records. MOUD initiation was defined as dispensation of more than one dose of the assigned MOUD within 14 days of randomization. Among participants who initiated MOUD, time to MOUD discontinuation was calculated as days in treatment from the first dose of the assigned MOUD (i.e. methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone) to (a) the last day of the assigned MOUD dispensation during the 24 weeks of treatment (i.e. discontinuation of the assigned MOUD) and (b) the last day of dispensation of any MOUD (i.e. discontinuation of any MOUD). Given that no survival differences have been observed between methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone [6], the latter outcome was included to account for potential treatment switches during the trial. Both definitions consider dispensation gaps ≤ 14 days as still engaged in MOUD [9], and participants who were lost to follow-up or died were considered ‘discontinued’.

For all the analyses, the main predictor variable was baseline fentanyl UDT, with a secondary focus on the assigned MOUD (buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone) as potential effect modifier. We also considered other variables that have been shown to influence MOUD outcomes [7, 16]. Specifically, we included the following baseline participant characteristics: demographics (age, sex, race, highest level of education); comorbidities [pain severity and interference as assessed by the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI-SF)] [17], and depression severity as assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II) [18]; substance-use-related factors (life-time heroin use, severity of OUD as assessed by the DSM-5 checklist, concurrent use of other substances as measured by UDT positive for other opioids, including oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, morphine, hydromorphone and 6-MAM, stimulants including cocaine and amphetamine, THC and benzodiazepines and alcohol intoxication in the last 30 days as assessed by the Addiction Severity Index-Self Report [19]); as well as health-care- and structural-level factors, including prior MOUD treatment (no; yes, the same as the assigned MOUD; yes, different from the assigned MOUD), province of residence (British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec), current housing situation and employment in the last 30 days [4].

Statistical analyses

We initially summarized baseline characteristics of the study sample, stratified by pre-treatment fentanyl exposure, using Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon’s rank sum test for continuous variables.

To estimate the impact of fentanyl on MOUD initiation we used logistic regression, with a confounder model approach previously described by Maldonado & Greenland [20] that we have used extensively in previous research [21]. In brief, beginning with a full model including the primary predictor variable (i.e. UDT positive for fentanyl), assigned MOUD (hypothesized effect modifier) and covariates that were associated with the outcome in bivariable analyses at P < 0.10, we manually removed covariates that produce the smallest relative change in the fentanyl coefficient in a stepwise manner, using backward elimination. This process was continued until the minimum relative change exceeded 5%. To investigate whether the effects of fentanyl on the outcome varied by type of MOUD, we examined an interaction term between these two variables. In the case of a significant interaction (P < 0.05), we conducted stratified analyses by type of MOUD. The final multivariable models were also adjusted by calendar year of enrolment to account for changes in the illicit drug market and quality of care (e.g. updated guidelines, availability of other MOUD) over time.

Secondly, we evaluated the impact of fentanyl on time to (assigned or any) MOUD discontinuation, restricted to participants who initiated treatment. We used the Kaplan–Meier method, with a log-rank test to calculate and compare the cumulative rates of MOUD discontinuation, stratified by baseline fentanyl UDT results. To evaluate the independent effect of fentanyl on (assigned or any) MOUD discontinuation, we used Cox proportional hazard models, with a confounder model approach, as described above, including the approach for covariate selection, adjustment by calendar year and testing for interaction between fentanyl and type of MOUD. Participants who did not discontinued MOUD were right-censored at 24 weeks (i.e. 168 days) after treatment initiation (i.e. end of data collection).

To assess the robustness of our estimate of the independent effect of fentanyl on the three outcomes in our multivariable models we performed a sensitivity analysis, where we fitted multivariable models including all covariates regardless of their bivariable associations. Analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.5; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and all P-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

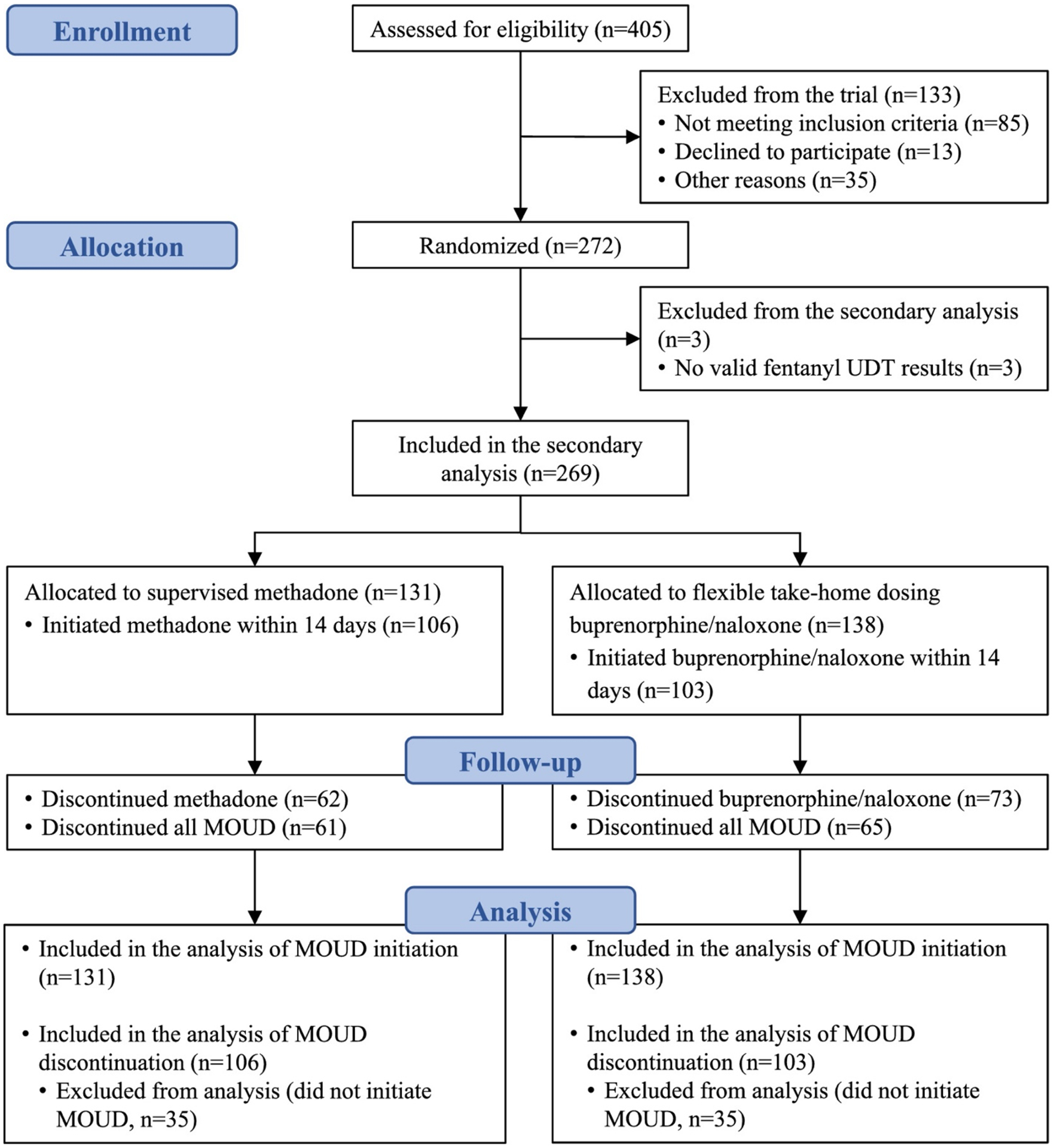

Of the 272 eligible and randomized individuals with POUD, three had missing baseline UDT results and were therefore excluded, resulting in a total analytical sample of 269 (98.9%). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [22] flow diagram of participants included in the present secondary analysis is presented in Fig. 1, and selected characteristics of the study sample, stratified by baseline fentanyl exposure, are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 38 years [interquartile range (IQR) = 31–46], 176 (65.4%) were male and 181 (67.3%) self-identified as white. Of the 85 participants self-identifying as black, Indigenous or other people of colour (BIPOC), the majority (70.6%) were of Indigenous ancestry. Almost all participants had a diagnosis of moderate/severe OUD (97.8%), and approximately half had a history of prior MOUD treatment (56.1%). Current use of opioids and other substances, as assessed by UDT, was high: 55.4% for fentanyl, 84.0% for other opioids, 66.5% for stimulants and 45.0% for cannabis.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of OPTIMA participants included in the secondary analyses of the impact of fentanyl on MOUD initiation and discontinuation.

MOUD = medication of opioid use disorder; UDT = urine drug test; OPTIMA = Optimal Personalized Treatment of early breast cancer using Multi-parameter Analysis

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of 269 randomized people with POUD in the OPTIMA, stratified by fentanyl UDT results

| Total, n (%) (N = 269) |

UDT fentanyl, n (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 149) |

Negative (n = 120) |

|||

| Assigned MOUD | 0.334 | |||

| Methadone | 131 (48.7) | 77 (51.7) | 54 (45.0) | |

| Buprenorphine | 138 (51.3) | 72 (48.3) | 66 (55.0) | |

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age (median, IQR) | 38 (31–46) | 37 (29–42) | 40 (33–51) | 0.002a |

| Male sex | 176 (65.4) | 90 (60.4) | 86 (71.7) | 0.070 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| White | 181 (67.3) | 81 (54.4) | 100 (83.3) | |

| BIPOC | 85 (31.6) | 66 (44.3) | 19 (15.8) | |

| High school education or higher | 218 (81.0) | 126 (84.6) | 92 (76.7) | 0.107 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| BDI-II score (median, IQR) | 25 (17–34) | 26 (19–36) | 21 (15–31) | 0.005a |

| BPI severity score (median, IQR) | 2.9 (0.0–5.5) | 3.0 (0.0–5.8) | 2.8 (0.0–5.3) | 0.618a |

| BPI interference score (median, IQR) | 2.5 (0.0–6.4) | 3.0 (0.0–7.0) | 1.0 (0.0–5.6) | 0.147a |

| Substance use-related factors | ||||

| Life-time heroin use | 185 (68.7) | 125 (83.9) | 60 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| OUD moderate/severe | 263 (97.8) | 149 (100.0) | 114 (95.0) | 0.019 |

| UDT positive for opioids (excluding fentanyl) | 226 (84.0) | 120 (80.5) | 106 (88.3) | 0.117 |

| UDT positive for stimulants (cocaine/amphetamines) | 179 (66.5) | 136 (91.3) | 43 (35.8) | <0.001 |

| UDT positive for benzodiazepines | 39 (14.5) | 18 (12.1) | 21 (17.5) | 0.280 |

| UDT positive for THC | 121 (45.0) | 64 (43.0) | 57 (47.5) | 0.534 |

| Alcohol intoxication last 30 days | 44 (16.4) | 10 (6.7) | 34 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Health-care-related factors | ||||

| Prior enrolment in MOUD | <0.001 | |||

| No | 118 (43.9) | 41 (27.5) | 77 (64.2) | |

| Yes: same as assigned MOUD | 103 (38.3) | 77 (51.7) | 26 (21.7) | |

| Yes: different from assigned MOUD | 48 (17.8) | 31 (20.8) | 17 (14.2) | |

| Structural-level factors | ||||

| Province | <0.001 | |||

| British Columbia | 68 (25.3) | 57 (38.3) | 11 (9.2) | |

| Alberta | 79 (29.4) | 70 (47.0) | 9 (7.5) | |

| Ontario | 52 (19.3) | 19 (12.8) | 33 (27.5) | |

| Quebec | 70 (26.0) | 3 (2.0) | 67 (55.8) | |

| Current homelessness | 100 (37.2) | 75 (50.3) | 25 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Employment last 30 days | 77 (28.6) | 34 (22.8) | 43 (35.8) | 0.022 |

MOUD = medication for opioid use disorder; BIPOC = black, Indigenous and people of colour; BDI-II = Beck Depression Index, version 2; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; UDT = urine drug test; THC = Δ−9tetrahydrocannabinol. IQR = interquartile range; POUD = prescription-type opioid use disorder; OPTIMA = Optimal Personalized Treatment of early breast cancer using Multi-parameter Analysis.

Wilcoxon’s rank sum test.

The prevalence of pre-treatment fentanyl exposure increased over time, from 11.1% in 2017 to 66.4% in 2019/2020. Relative to individuals with negative fentanyl UDT, fentanyl-exposed participants were more likely to be younger, to self-identify as BIPOC, to be unemployed or homeless, to have greater depressive symptomatology, to report life-time history of heroin use and MOUD treatment and were more likely to be currently using stimulants. Randomization was well balanced, with 131 (48.7%) individuals randomized to methadone and 138 (51.3%) to buprenorphine/naloxone, with no statistically significant differences in treatment allocation between the two fentanyl groups (P = 0.334).

Impact of fentanyl on MOUD initiation

In total, 209 participants (77.7%) initiated MOUD (106 methadone and 103 buprenorphine/naloxone). Bivariable and multivariable results (including covariates remaining in the final confounder model) of the relationship between baseline fentanyl exposure and MOUD initiation are presented in Table 2. Although baseline fentanyl exposure was negatively associated with MOUD initiation in unadjusted analysis [odds ratio (OR) = 0.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.08–0.36], this association was attenuated and became statistically insignificant in the adjusted model [adjusted OR (aOR) = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.16–1.63]. There was no interaction between MOUD and fentanyl (P = 0.632).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression model of the association between baseline fentanyl UDT and MOUD initiation among 269 people with POUD in the OPTIMA trial

| Unadjusted | Adjusted†‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) |

P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

P-value | |

| Main explanatory variable | ||||

| UDT positive for fentanyl at baseline | 0.18 (0.08–0.36) | <0.001* | 0.55 (0.17–1.71) | 0.312 |

| Assigned MOUD | ||||

| Buprenorphine/naloxone (versus methadone) | 0.69 (0.39–1.24) | 0.218 | 0.56 (0.29–1.07) | 0.080 |

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age (per year older) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.006* | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 0.167 |

| Male sex | 1.23 (0.67–2.23) | 0.488 | ||

| White (versus BIPOC) | 2.29 (1.26–4.14) | 0.006* | 1.16 (0.58–2.27) | 0.675 |

| High school education or higher | 0.97 (0.45–1.99) | 0.942 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| BDI-II score (per 1 point higher) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.945 | ||

| BPI severity score (per 1 point higher) | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.998 | ||

| BPI interference score (per 1 point higher) | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) | 0.683 | ||

| Substance use related factors | ||||

| Life-time heroin use | 0.54 (0.26–1.03) | 0.073* | 0.89 (0.37–2.10) | 0.785 |

| OUD moderate/severe (versus mild) | 0.69 (0.04–4.40) | 0.739 | ||

| UDT positive for opioids (excluding fentanyl) | 1.89 (0.90–3.82) | 0.081* | ||

| UDT positive for stimulants (cocaine/amphetamines) | 0.13 (0.05–0.32) | <0.001* | 0.27 (0.08–0.83) | 0.029 |

| UDT positive for benzodiazepines | 1.37 (0.60–3.54) | 0.481 | ||

| UDT positive for THC | 1.19 (0.67–2.14) | 0.558 | ||

| Alcohol intoxication last 30 days | 1.63 (0.72–4.18) | 0.269 | ||

| Health-care-related factors | ||||

| Prior enrolment in MOUD (ref: no) | ||||

| Yes, same as assigned MOUD | 0.54 (0.28–1.04) | 0.067* | ||

| Yes, different from assigned MOUD | 0.47 (0.21–1.04) | 0.059* | ||

| Structural-level factors | ||||

| Province (ref: British Columbia) | ||||

| Alberta | 0.42 (0.20–0.85) | 0.018* | 0.49 (0.21–1.11) | 0.090 |

| Ontario | 1.19 (0.49–2.99) | 0.706 | 0.54 (0.17–1.70) | 0.292 |

| Quebec | 6.32 (1.96–28.32) | 0.005* | 2.00 (0.40–11.75) | 0.410 |

| Current homelessness | 0.55 (0.31–0.99) | 0.044* | ||

| Employment last 30 days | 2.07 (1.04–4.43) | 0.047* | 0.62 (0.36–1.06) | 0.081 |

MOUD = medication for opioid use disorder; BIPOC = black, Indigenous and people of colour; UDT = urine drug test; THC = Δ−9-tetrahydrocannabinol; BDI-II = Beck Depression Index, version 2; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; OPTIMA = Optimal Personalized Treatment of early breast cancer using Multi-parameter Analysis; POUD = prescription-type opioid use disorder; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

P < 0.10 in the unadjusted analyses and considered for inclusion in the multivariable model.

Only the variables included in the final multivariable confounder model are presented in this column.

Model also adjusted for calendar-year of enrolment.

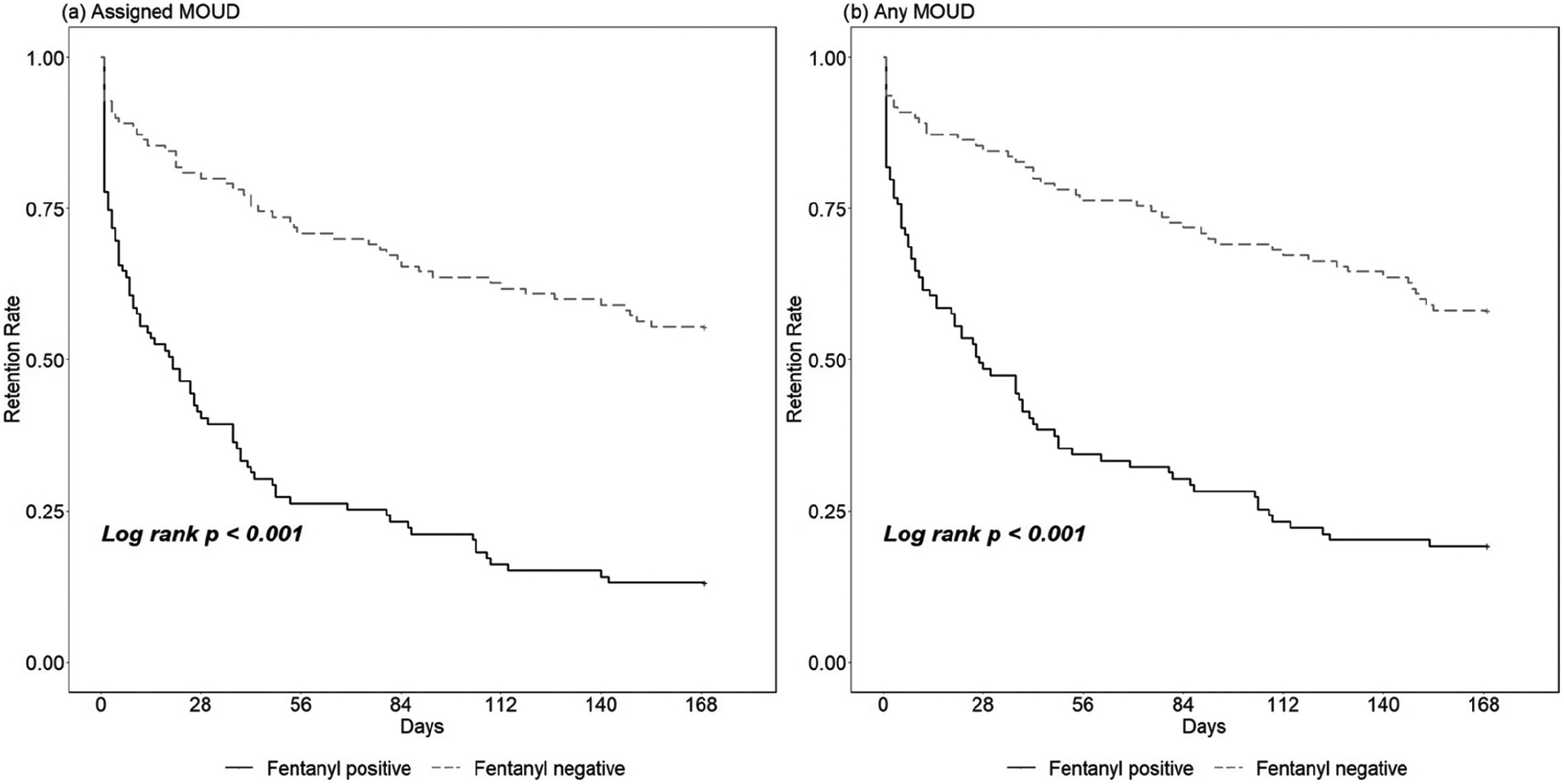

Impact of fentanyl on time to assigned or any MOUD discontinuation

Figure 2a,b displays survival curves of time in the assigned or any treatment, respectively, among participants who initiated treatment (n = 209), stratified by pre-treatment fentanyl UDT.

FIGURE 2.

Survival curves of time in the (a) assigned or (b) any MOUD, stratified by baseline fentanyl UDT.

MOUD = medication of opioid use disorder; UDT = urine drug test

The median time in the assigned MOUD was 55 days (IQR = 9–168), with shorter duration for fentanyl-exposed participants (median = 20 days, IQR = 3–75) compared to non-exposed (median = 168, IQR = 45–168, P < 0.001).

In total, there were 41 treatment switches in the trial, with higher rates among fentanyl-exposed individuals than among non-exposed participants (27.3 versus 12.8%, P = 0.015). Reflecting this, when discontinuation from any MOUD was considered, overall the time in treatment increased (median = 93 days, IQR = 13–168), but fentanyl-exposed participants still had shorter durations than non-exposed participants (median 27 versus 168 days, respectively, P < 0.001).

Available UDT results indicated high rates of opioid use prior to MOUD discontinuation, with differences between the two fentanyl groups. Specifically, among fentanyl-exposed individuals. 86.7 and 86.2% of UDT were positive for fentanyl (76.7 and 82.8% for other opioids) at the time of assigned or any MOUD discontinuation, respectively. Among non-exposed participants, these numbers were 3.4 and 4.0% for fentanyl and 58.6 and 68.0% for other opioids, further validating distinct opioid use patterns in these two sub-populations of people with POUD.

As indicated in Table 3, although at the bivariable level baseline positive fentanyl UDT was associated with shorter time in both assigned or any MOUD [hazard ratio (HR) = 3.61, 95% CI = 2.52–5.17 and HR = 3.32, 95% CI = 2.30–4.80, respectively], these associations were no longer statistically significant in the adjusted Cox models (aHR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.73–2.06 and aHR = 1.35, 95% CI = 0.78–2.33, respectively). No interaction between fentanyl and MOUD was observed for any of the discontinuation outcomes (P > 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression of the association between baseline fentanyl UDT and time to (a) assigned or (b) any MOUD discontinuation among 209 people with POUD in the OPTIMA trial who initiated treatment

| Assigned MOUD discontinuation | Any MOUD discontinuation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR†‡ (95% CI) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR†‡ (95% CI) | |

| Main explanatory variable | ||||

| UDT positive for fentanyl at baseline | 3.61 (2.52–5.17)* | 1.23 (0.73–2.06) | 3.32 (2.30–4.80)* | 1.35 (0.78–2.33) |

| Assigned MOUD | ||||

| Buprenorphine/naloxone (versus methadone) | 1.28 (0.91–1.79) | 1.44 (0.99–2.08) | 1.04 (0.73–1.48) | 1.10 (0.75–1.62) |

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age (per year older) | 0.98 (0.97–1.00)* | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00)* | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) |

| Male sex | 0.65 (0.46–0.92)* | 0.65 (0.46–0.94)* | ||

| White (versus BIPOC) | 0.52 (0.37–0.75)* | 1.00 (0.68–1.48) | 0.53 (0.37–0.67)* | 0.85 (0.56–1.29) |

| High school education or higher | 1.18 (0.76–1.85) | 1.05 (0.67–1.65) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| BDI-II score (per 1 point higher) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | ||

| BPI severity score (per 1 point higher) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | ||

| BPI interference score (per 1 point higher) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 1.01 (0.95–1.06) | ||

| Substance use related factors | ||||

| Life-time heroin use | 1.76 (0.21–2.57)* | 1.20 (0.75–1.92) | 1.59 (1.08–2.34)* | |

| OUD moderate/severe (versus mild) | 0.93 (0.35–2.53) | 0.80 (0.29–2.16) | ||

| UDT positive for opioids (excluding fentanyl) | 0.67 (0.42–1.05)* | 0.72 (0.45–1.15) | ||

| UDT positive for stimulants (cocaine/amphetamines) | 3.07 (2.09–4.50)* | 1.62 (0.97–2.71) | 2.93 (1.97–4.38)* | 1.60 (0.93–2.76) |

| UDT positive for benzodiazepines | 0.53 (0.30–0.91)* | 0.76 (0.43–1.35) | 0.55 (0.31–0.97)* | |

| UDT positive for THC | 0.95 (0.68–1.33) | 0.91 (0.64–1.29) | ||

| Alcohol intoxication last 30 days | 0.73 (0.45–1.17) | 0.71 (0.43–1.15) | ||

| Health-care-related factors | ||||

| Prior enrolment in MOUD (ref: no) | ||||

| Yes, same as assigned MOUD | 1.77 (1.22–2.57)* | 1.77 (1.21–2.59)* | ||

| Yes, different from assigned MOUD | 1.63 (1.00–2.66)* | 1.26 (0.74–2.13) | ||

| Structural-level factors* | ||||

| Province (ref: British Columbia) | ||||

| Alberta | 0.63 (0.42–0.97)* | 0.52 (0.32–0.83) | 0.70 (0.45–1.0.8) | |

| Ontario | 0.38 (0.24–0.61)* | 0.45 (0.25–0.80) | 0.46 (0.29–0.74)* | |

| Quebec | 0.11 (0.06–0.19)* | 0.15 (0.07–0.30) | 0.12 (0.07–0.22)* | |

| Current homelessness | 1.84 (1.30–2.59)* | 2.10 (1.47–2.99)* | 1.18 (0.77–1.80) | |

| Employment last 30 days | 0.68 (0.47–1.00)* | 0.82 (0.54–1.23) | 0.65 (0.44–0.97)* | 0.76 (0.47–1.20) |

BIPOC = black, Indigenous and people of colour; OUD = opioid use disorder; UDT = urine drug test; THC = Δ−9-tetrahydrocannabinol; BDI-II = Beck Depression Index, version 2; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; MOUD = medication for opioid use disorder; HR = hazard ratio; OPTIMA = Optimal Personalized Treatment of early breast cancer using Multi-parameter Analysis; POUD = prescription-type opioid use disorder.

P < 0.10 in the unadjusted analyses and considered for inclusion in the multivariable model.

Only the variables included in the final multivariable confounder model are presented in this column.

Models also adjusted for calendar-year of enrolment and assigned MOUD.

Sensitivity analyses

Our sensitivity analyses yielded similar results. Specifically, after adjusting for all hypothesized confounders, fentanyl exposure was not associated with treatment initiation (aOR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.14–1.88) or with time to assigned or any MOUD discontinuation (aHR = 1.37, 95% CI = 0.77–2.41 and aHR = 1.29, 95% CI = 0.82–2.01, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Using data from a pragmatic clinical trial conducted in outpatient Canadian clinical settings among individuals with POUD during a well-documented opioid overdose epidemic, our study provides important clinical evidence on potential impacts of fentanyl exposure on engagement in MOUD. Specifically, while in crude analyses baseline fentanyl exposure was associated with reduced odds of MOUD initiation and shorter time in treatment, these negative effects of fentanyl were no longer observed in adjusted analyses. In addition, there was no interaction between MOUD and fentanyl. Altogether, these findings suggest that both buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone may be considered appropriate first-line treatment options for people with POUD regardless of fentanyl use or exposure, and that other characteristics of fentanyl-exposed individuals, rather than intrinsic characteristics of fentanyl, may be driving the association with poorer MOUD outcomes.

Consistent with Canadian epidemiological evidence [2], fentanyl exposure was common in this sample of treatment-seeking adults with POUD, particularly among individuals from the western provinces (i.e. British Columbia and Alberta). Also, similar to other studies, fentanyl-exposed individuals were more likely to have a past history of heroin use and prior experience with MOUD, as well as to be concurrently using stimulants [23–25]. However, different from these past reports [23–25], in our analysis participants with UDT positive for fentanyl were more likely to self-identify as BIPOC (mainly Indigenous ancestry), to be homeless or unemployed and were using other opioids at similarly high rates. These results may reflect characteristics of our study sample potentially comprising two distinct groups of people with POUD, one with preferences for pharmaceutical opioids only and the other for both pharmaceutical opioids and illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Our unadjusted analyses indicated that fentanyl-exposed participants were less likely to initiate MOUD, as well as to remain in treatment once initiated. However, and in line with an emerging but limited body of evidence [25–27], we did not find evidence of a negative impact of baseline fentanyl exposure on either of these outcomes in adjusted analyses. A possible explanation for these discordant findings may be that, rather than distinct pharmacological characteristics of fentanyl (e.g. high potency and lipophilicity) [13], other socio-demographic or clinical characteristics of fentanyl-exposed participants in our study may be mainly responsible for the negative effects on MOUD engagement. For example, as described above, people with POUD in our study who tested positive for fentanyl at enrolment were more likely to be concurrently using stimulants, as well as to present markers of socio-structural marginalization, all of which (in particular stimulant use) have been associated with more complicated treatment trajectories [7, 16, 28]. Altogether, findings suggest that while fentanyl use at treatment intake might not negatively impact MOUD outcomes per se, clinicians could use this information as a potential red flag for other patient characteristics underpinning poorer outcome prognosis that may require additional interventions. Future research should seek to more systematically characterize socio-demographic and clinical differences as well as potential differential treatment response in these sub-populations of people with POUD [13, 29], particularly given increasing prevalence of methamphetamine use among people with OUD [30]. More clearly understanding these differences could allow to identify potential modifiable factors of fentanyl-exposed patients to improve clinical outcomes in that population.

Also encouraging is the lack of evidence of effect modification by type of MOUD for the association between fentanyl and treatment initiation and discontinuation. Although pre-clinical data suggest that full opioid agonists (e.g. methadone) may be more effective than partial agonists (e.g. buprenorphine) in blocking the effects of high-potency opioids such as fentanyl, whether or not these findings can be extrapolated to humans is largely unknown [13]. In addition, some advantages of buprenorphine/naloxone relative to methadone (e.g. better tolerability, lower programmatic intensity, including take home dosing) may have contributed to the absence of differential treatment response of type of MOUD based on fentanyl exposure.

Findings from this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, this study was conducted among a sample of treatment-seeking adults with POUD in Canada, a setting with a universal health system, where both methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone are covered under provincial drug plans for those with low income and readily available for dispensation by community pharmacies [31]. In addition, participants consented to be randomized to methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone, and providers from the Canadian clinics where the study took place were skilled in seamless transitions between MOUD modalities. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to other populations with OUD or other settings. Secondly, we relied upon UDT to define fentanyl exposure, and therefore we were not able to determine whether this was licit or illicit and whether the use was intentional or unintentional, which may have implications for clinical decision-making. While initial reports from Canada and the United States have indicated that the majority of fentanyl exposure was unintentional (e.g. use of fentanyl-laced drugs), more recent studies suggest that the prevalence of intentional use has been increasing [32]. In addition, the test strips used have a short detection window and may not detect all fentanyl analogues, and thus the true prevalence of fentanyl exposure may have been underestimated. Thirdly, our primary outcome was based on continuous engagement in MOUD. Although we acknowledge that cycles of engagement and disengagement of MOUD are common, we decided to focus upon the first episode of continuous treatment, given that even short periods off MOUD are associated with increased mortality risk, particularly periods immediately after MOUD discontinuation [5, 6]. Finally, our analysis only considered fentanyl exposure as a dichotomous variable (yes versus no) and only included baseline values. To more clearly understand the relationship between fentanyl use, type of MOUD and outcomes, further research is warranted to explore the impacts of different frequencies of fentanyl and doses of MOUD, as well as changes over time.

In conclusion, this secondary analysis of a pan-Canadian pragmatic clinical trial comparing flexible take-home dosing buprenorphine/naloxone and supervised methadone models of care among people with POUD found that fentanyl exposure did not negatively impact MOUD initiation or retention. Our findings suggest that both buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone may be effective first-line treatment options for people who use fentanyl, particularly in settings where both options are offered in primary care, and as long as a comprehensive patient-centred approach is taken, inclusive of polysubstance use and social determinants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; grant numbers: SMN-139148, SMN-139149, SMN-139150, SMN-139151) through the Canadian Research Initiative on Substance Misuse (grant numbers: CIS-144301, CIS144302, CIS-144303, CIS-144304). M.E.S. is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and St Paul’s Foundation Scholar Award. D.J.A. holds a research scholar award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé. B.L.F. is supported by a clinician scientist award from the Department of Family and Community Medicine and by the Addiction Psychiatry Chair of the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto. J.B. is partly supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research chair in Addiction Medicine. E.W. is partly supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Addiction Medicine. All funders had no role in trial design, conduct, analysis or reporting. The authors are grateful to all participants and clinical and research staff. The authors specially thank Jill Ficowski, Denise Adams, Oluwadamilola Akinyemi, Farihah Ali, Katrina Blommaert, Emma Garrod, Nirupa Goel, Wendy Mauro-Allard, Kirsten Morin, Benita Okocha, Eve Poirier, Aïssata Sako, Geneviève St-Onge, José Trigo, Angela Wallace and Amel Zertal for research and administrative assistance.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

M.E.S. has received partial support from Indivior’s Investigator Initiated Study programme for work outside this study. B.L.F. receives or has received support from Pfizer Global Research Awards in Nicotine Dependence (GRAND) programme, Brainsway, Bioprojet, Alkermes, Canopy, ACS and non-financial support from Aurora for work outside this study. J.B.B. receives or has received support from Gilead Sciences and AbbVie outside this study. E.W. is the Chief Medical Officer of a mental health company called Numinus Wellness. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

Available at: clinicaltrials.gov NCT03033732.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donroe JH, Socias ME, Marshall BDL. The deepening opioid crisis in North America: historical context and current solutions. Curr Addict Rep. 2018; 5: 454–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. Opioids and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. Available at: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants Accessed 7 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad F, Rossen L, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm Accessed 7 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruneau J, Ahamad K, Goyer ME, Goyer MÈ, Poulin G, Selby P, et al. Management of opioid use disorders: a national clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J. 2018; 190: E247–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, Zhou H, Homayra F, Slaunwhite A, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020; 368:m772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017; 357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor AM, Cousins G, Durand L, Barry J, Boland F. Retention of patients in opioid substitution treatment: a systematic review. PLOS ONE. 2020; 15:e0232086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network (MODRN), Brown E, Schutze M, Taylor A, Jorgenson D, McGuire C, et al. Use of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder among US Medicaid enrollees in 11 states, 2014–2018. JAMA. 2021; 326: 154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Leff JA, Linas BP, Walley AY. Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018; 85: 90–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: a systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016; 35: 22–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 2:CD002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen S, Larance B, Degenhardt L, Gowing L, Kehler C, Lintzeris N. Opioid agonist treatment for pharmaceutical opioid dependent people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 5:CD011117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comer SD, Cahill CM. Fentanyl: receptor pharmacology, abuse potential, and implications for treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019; 106: 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socias ME, Ahamad K, Le Foll B, Lim R, Bruneau J, Fischer B, et al. The OPTIMA study, buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone models of care for the treatment of prescription opioid use disorder: study design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018; 69: 21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jutras Aswad D, Le Foll B, Ahamad K, et al. Flexible buprenorphine/naloxone model of Care for Reducing Opioid use in individuals with prescription-type opioid use disorder: An open-label, pragmatic, non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2022; in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krawczyk N, Williams AR, Saloner B, Cerda M. Who stays in medication treatment for opioid use disorder? A national study of outpatient specialty treatment settings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021; 126:108329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis BB, Roshanov PS, Bawor M, Paul J, Varenbut M, Daiter J, et al. Usefulness of the brief pain inventory in patients with opioid addiction receiving methadone maintenance treatment. Pain Physician. 2016; 19: E181–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seignourel PJ, Green C, Schmitz JM. Factor structure and diagnostic efficiency of the BDI-II in treatment-seeking substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008; 93: 271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen CS, Henson BR, Finney JW, Moos RH. Consistency of self-administered and interview-based addiction severity index composite scores. Addiction. 2000; 95: 419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993; 138: 923–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Socias ME, Choi J, Lake S, Wood E, Valleriani J, Hayashi K, et al. Cannabis use is associated with reduced risk of exposure to fentanyl among people on opioid agonist therapy during a community-wide overdose crisis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021; 219:108420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008; 337:a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gryczynski J, Nichols H, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Hill P, Wireman K. Fentanyl exposure and preferences among individuals starting treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019; 204:107515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi K, Milloy MJ, Lysyshyn M, DeBeck K, Nosova E, Wood E, et al. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018; 183: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook RR, Torralva R, King C, Lum PJ, Tookes H, Foot C, et al. Associations between fentanyl use and initiation, persistence, and retention on medications for opioid use disorder among people living with uncontrolled HIV disease. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021; 228:109077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone AC, Carroll JJ, Rich JD, Green TC. Methadone maintenance treatment among patients exposed to illicit fentanyl in Rhode Island: safety, dose, retention, and relapse at 6 months. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018; 192: 94–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakeman SE, Chang Y, Regan S, Yu L, Flood J, Metlay J, et al. Impact of fentanyl use on buprenorphine treatment retention and opioid abstinence. J Addict Med. 2019; 13: 253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLaughlin MF, Li R, Carrero ND, Bain PA, Chatterjee A. Opioid use disorder treatment for people experiencing homelessness: a scoping review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021; 224:108717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanger N, Bhatt M, Singhal N, Panesar B, D’Elia A, Trottier M, et al. Treatment outcomes in patients with opioid use disorder who were first introduced to opioids by prescription: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2020; 11:812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, Cicero TJ. Twin epidemics: the surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018; 193: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brissette S, Kerr T, Marsh DC, Schackman BR, et al. A call for evidence-based medical treatment of opioid dependence in the United States and Canada. Health Aff. 2013; 32: 1462–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ickowicz S, Kerr T, Grant C, Milloy MJ, Wood E, Hayashi K. Increasing preference for fentanyl among a cohort of people who use opioids in Vancouver, Canada, 2017–2018. Subst Abuse. 2022; 43: 458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]