Racial inequity in mental health care quality is influenced by many systems-level factors, as elucidated by critical race theory and other keystone frameworks.1 A growing body of literature also suggests provider-level bias to be a key driver.1–3 There is specific evidence that racism is an important driver of health inequities among youth4 and that it is mediated, in part, by provider-level processes related to diagnosis and treatment.2 For example, in child and adolescent psychiatry, youth who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) experience disproportionate rates of delayed diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorder, overdiagnosis of conduct disorder, and underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.4 Black and multiracial adolescents are at highest risk of suicide,5 yet are least likely to receive preventive psychotherapy.4

Despite these findings, available evidence suggests a reluctance among mental health providers to acknowledge their role in perpetuating racialized disparities. A 2010 American Psychiatry Association (APA) survey found that only 12% of psychiatrists were familiar with research on racial inequities in psychiatric care and that 60% believed that racial disparities were more likely to exist in other providers’ practices than in their own.6 More recently, a 2020 APA survey of more than 500 psychiatrists revealed that 43% did not believe that provider-level decisions in management reinforce racial disparities in quality of care.7 For these reasons, addressing racial bias among mental health care providers is a priority and undeniably long overdue.

As clinicians, we are dedicated to providing our patients with the highest level of care possible. Accomplishing this requires addressing unexamined racial bias by way of refining our clinical skills. Training clinicians offers an opportunity to minimize provider bias and reduce downstream effects on quality of care. Antiracist training is in high demand among child and adolescent psychiatry clinicians,8 indicating that trainings are likely to be well received.

Currently, there are few published educational models for teaching clinicians about racism and fewer designed for psychiatry. None of these models use evidence-based principles or target provider-level bias. Given the sensitivity of this issue, which involves asking providers to reflect on their own unique and potentially deeply rooted biases, individualized self-guided curricula hold promise. Further supporting this approach are study findings that self-discovery in a private context facilitates reflective processes crucial to addressing racial bias.3 Self-guided lessons have the potential to guide careful reflection on unexamined attitudes, cognitions, and behaviors that maintain racism. Core strategies might challenge maladaptive beliefs about race, mitigate feelings of defensiveness, and facilitate empathetic perspective-taking.1,3

Intervention delivery methods must be carefully considered, especially with regard to efficiency and effectiveness, given the high workload that child and adolescent psychiatry clinicians often face. Possibilities for self-guided programming include traditional workbook-style, web-based, and mobile phone–delivered modalities. It is important that the intervention be tailored to the needs of individual providers, as this is known to increase the likelihood of success.9 There is a growing literature base supporting the use of digital devices in the practice of medicine and public health.9 These methods might be most familiar to clinicians, such as devices that assist patients with managing their health conditions through habit tracking or wearable technology. In contrast to these patient-level interventions, digital public health efforts operate at all levels, such as at the provider or community level.9 This is primary prevention because it addresses upstream factors to reduce risk of disease development or negative outcomes. At the provider level, technology-assisted education can be used to improve patient care.9 In fact, it has been successfully used to improve physician knowledge, clinical skills, and outcomes related to cancer, diabetes, and hypertension.9 In mental health care, digital coaching has been shown to improve shared decision making between clinicians and BIPOC adult patients.10 We envision a novel self-guided, interactive, learning module to be delivered to child and adolescent psychiatry providers through internet-capable devices.

A digital approach to antiracism provider education has many advantages and is supported by a growing body of scholarly work.9,11 First, it offers a flexible delivery system, through either web-based or mobile devices, to meet the diverse needs of providers. Web-based options are a possibility and may be preferred by clinicians who do not have access to a smartphone. Other providers, especially trainees, may find mobile device–accessible programming to be a better fit with their busy and variable workloads. Flexible content delivery can be especially important when addressing racism in real time. Digital tools can bolster a provider’s ability to practice new antiracist skills and self-monitor reactions to racism soon after it is encountered.9 Numerous digital antiracist applications outside of health care have harnessed this method in various ways. For example, Australia’s Welcome to Country application alerts users when entering Aboriginal land and provides real-time teaching about their racialized history.11 The American Civil Liberties Union applications Copwatch and Stop and Frisk provide self-monitoring and autonomous documentation of structural violence experienced or witnessed by users.11

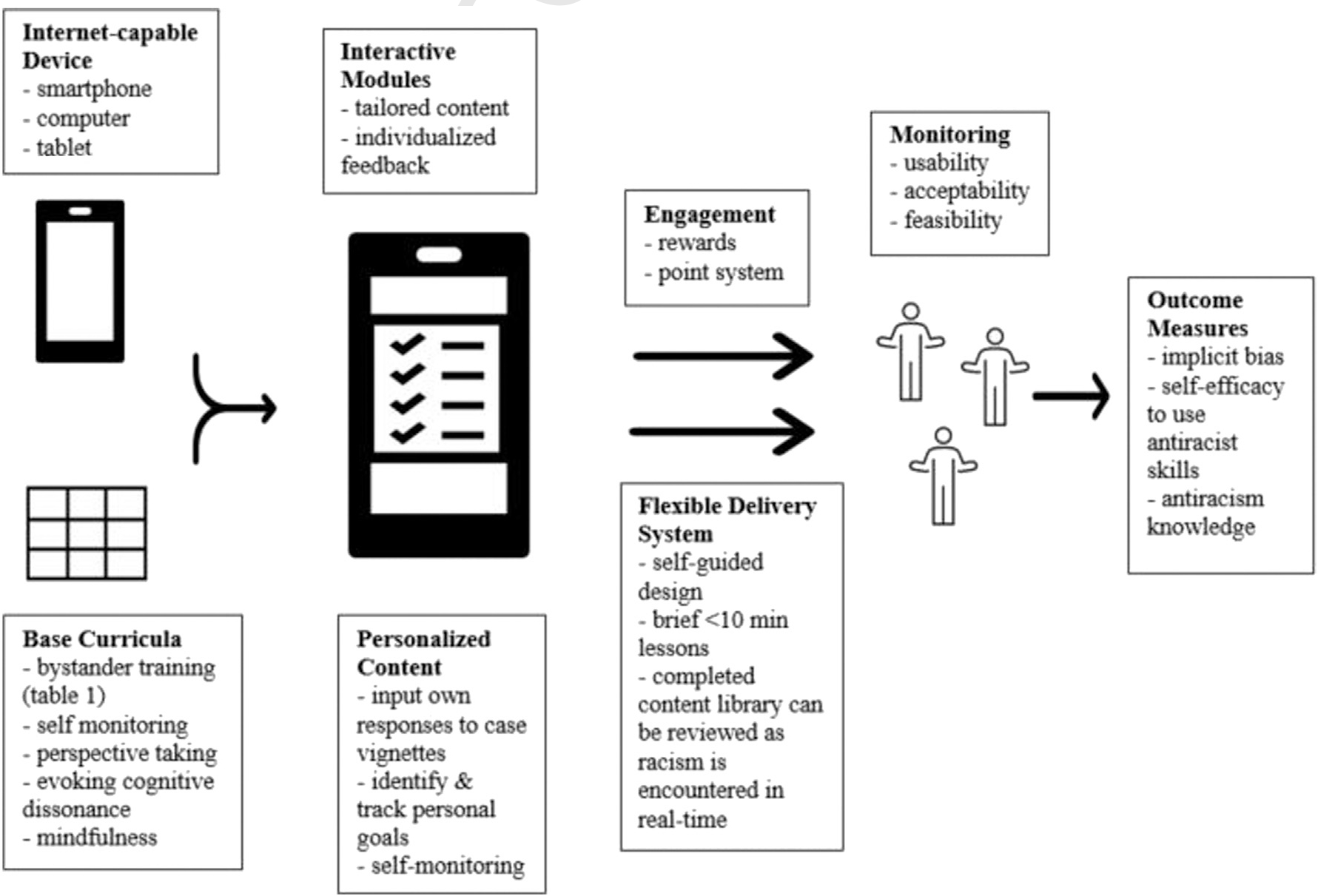

Second, in contrast to passive learning through lectures, mandatory workshops, or PowerPoint presentations, web-based programming allows for customization and individualization of educational content to promote more active learning. As depicted in Figure 1, digital educational content may be personally tailored and interactive, well-established predictors of behavioral intervention effectiveness.9–11 Configuration of rewards and individualized feedback are known to further promote engagement and effectiveness.9 In addition, process measures can be collected digitally to allow for systemic, iterative, and ongoing monitoring and real-time adjustments to meet the needs of users. Finally, compared to in-person interventions, web-based programming can often be developed and disseminated more rapidly and at a lower cost.9

FIGURE 1.

Digital Technology–based Implementation Schematic for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Provider Antiracism Education

Design of any behavioral intervention must be firmly rooted in evidence. To date, a number of methods have shown effectiveness in reducing racial bias in laboratory and field studies.3 This includes the cognitive-behavioral strategies of structured self-monitoring, challenging problematic core beliefs, and building self-efficacy.3 Other strategies, such as bystander response training,12 careful induction of cognitive dissonance, perspective-taking, and mindfulness-based practices, have also demonstrated effectiveness and have the potential to be incorporated within an interactive digitally delivered curriculum.3 Standard base curricula may be developed using these evidence-based principles and then further individualized using digital tools to meet the unique needs of individual providers. Table 1 represents a base example of bystander response training content that might be presented to providers in digital format. Here, the goal is to promote self-efficacy to disrupt racism encountered in the workplace, which can be accomplished if providers avoid passivity and confront racism in the moment.12 Case vignettes depict common situations encountered in child and adolescent psychiatry that tend to involve provider-level bias and are broken down into antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Passive provider behaviors maintain racism and lead to unfavorable consequences for patients. Conversely, active behaviors disrupt racism and create more favorable outcomes. Prior research has illuminated key factors that facilitate active bystander responses, 3 of which are taught in the cases: knowledge of what racism is, awareness of harm caused by racism, and desire to educate the perpetrator.12 For instance, in the context of overdiagnosis of conduct disorder among Black children, passively continuing inaccurate prior chart diagnoses can lead to inappropriate and ineffective patient care. Knowledge that this passivity contributes to racial disparities may encourage more thoughtful mental health history-taking and may avoid harmful patient outcomes. Figure 1 depicts how the base educational content described in Table 1 can be integrated within a digital delivery system and personally tailored to the needs of individual providers. For example, users may input personally formulated potential responses to the case vignette antecedents to check for understanding. They may explore and document which key bystander factors might best motivate their own active antiracist behaviors or brainstorm in which situations in their own workplace they might be most likely to encounter racism and practice active bystander responses. Users may also engage in goal setting related to frequency of active responses they would like to practice, which may be tracked through data analytics. Designed with guidance from available literature on evidence-based techniques to address racial bias, the social-ecological model of behavior change, adult learning theory, and years of clinical expertise, such an intervention would aim to provide concrete solutions to seemingly complex problems, anchored within an emotional context to enhance retention.

TABLE 1.

Lesson Confronting Suspected Racism in the Moment as a Bystander

| Case 1: Overdiagnosis of conduct disorder in Black boys | ||||

|

| ||||

| Antecedent | Potential passive behavior | Potential consequences: Racism maintained | Potential active behavior: Facilitated by knowledge of what racism is | Potential consequence: Antiracism initiated |

| A 12-year-old Black boy with a history of early childhood abuse presents to a child psychiatry clinic for intake with a chart diagnosis of CD made by his pediatrician. His teachers report frequent verbal outbursts. His prior psychiatrist noted that his failing grades are attributable to “violent behavior in the classroom.” There is no prior workup or evaluation for ADHD, intellectual disability, PTSD, or anxiety. | Keep CD at the top of the differential diagnosis and start on risperidone daily while planning to obtain some information to evaluate for ADHD. | The patient and his family miss the next 2 appointments and the patient gains 25 lb in 2 months. His teacher expresses concern that he is falling asleep in class and failing tests. He is subsequently lost to follow-up, maintains a chart CD diagnosis throughout his adolescence, later dropping out of school and eventually becoming institutionalized in the juvenile justice system. | Re-evaluate the patient and family, probing for alternative explanations for the presentation with sensitivity to the overdiagnosis of CD in black boys. Obtain necessary information before initiating appropriate treatment. | On further evaluation, you find that the patient is experiencing hyperarousal stemming from PTSD, exacerbated by untreated ADHD. An intake for psychotherapy is arranged. Plans to target PTSD and ADHD with evidence-based psychopharmacology are developed in collaboration with the patient and parents. Psychoeducation is given to the family and patient. A letter is written to his school to advocate for an IEP. With medication changes and access to on-site learning therapists, the patient begins to improve his school performance. His temper outbursts cease. He receives all As and Bs on his report card and feels hopeful in his intelligence and abilities for the first time in his life. |

| Case 2: Delay in diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder | ||||

|

| ||||

| Antecedent | Potential passive behavior | Potential consequences: Racism maintained | Potential active behavior: Facilitated by awareness of harm caused by racism | Potential consequence: Antiracism initiated |

| A 17-year-old Black girl presents to the ED for evaluation of impulsive selfinjurious behaviors (cutting, head banging) in the setting of depression precipitated by a break-up. She is highly irritable on interview and endorses that her symptoms will “never” get better and has significant difficulty processing precipitants of her distress. She was recently evaluated by a therapist for lifelong interpersonal difficulties and was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. On examination, you notice the patient’s cognitive rigidity, black and white thinking, and significant difficulty navigating social stressors. | Interpret your examination as further congruency with borderline personality disorder and make a referral to a DBT program. | The patient is promptly discharged from the DBT program for “treatment-interfering behaviors” related to poor attendance and verbal altercations with co-attendees. She becomes progressively more isolated and depressed, culminating in a suicide attempt. | You are aware that girls with autism can present with symptoms that resemble cluster B traits. You are also aware that Black youth are at high risk of misdiagnosis with regard to autism. With awareness of and sensitivity to these issues, you obtain a detailed history and examination. | Closer evaluation reveals a long-term history of social/emotional impairments, highly restricted interests, and behaviors focused on sameness and sensory avoidance. You review this information with the patient and her family and propose that autism may better explain her presentation than cluster B traits. You explain that this designation is important to ensure appropriate management. You provide the family and patient with educational materials on autism and refer them to outpatient specialists in ASD. The patient begins intensive psychotherapy with an ASD specialist. She begins to recognize connections between cognitive rigidity stemming from underlying ASD, symptoms of depression, and difficulty with problem solving. She gradually achieves remission in her MDD symptoms and embraces her difference thanks to community and online resources. |

| Case 3: Suicide risk assessment in multiracial youth | ||||

|

| ||||

| Antecedent | Potential passive behavior | Potential consequence: Racism maintained | Potential active behavior: Facilitated by desire to educate perpetrator | Potential consequence: Antiracism initiated |

| You are working in the ED with a white colleague. They are discussing the most recent patient they saw, a “Black” 16-year-old girl they were planning to discharge from the ED. Your colleague tells you that she came in with SI but that “the kid seemed fine.” Admits that the girl was not giving much information in the interview and seemed pretty shut down, but they were able to develop a safety plan with her and her mom. | You realize that your colleague was unlikely to have screened for multiracial identity and related suicide risk factors, such as sense of connectedness to community and belonging. You are worried they may be miscalculating suicide risk, but are not sure how to bring it up and think that it will probably be okay. | The patient is discharged from the ED. Five days later, the parents find a suicide note on her bed and she does not return home from school on Friday. Her suicide note describes intense feelings of loneliness and feeling like she “doesn’t fit anywhere." She describes the difficulty of not having a sense of community at school. She is eventually found unresponsive in a nearby park and brought to the ED for resuscitation owing to an intentional overdose on alcohol. |

You recognize this interaction as an opportunity to provide education on suicide risk assessment in multiracial youth. In a nonjudgmental tone, you ask your colleague about the case, uncovering the assumption about the patient’s race and missing aspects of a comprehensive suicide risk assessment. You state the importance of these measures and ask them to clarify and repeat their reasoning for discharging the patient without more workup. |

Your colleague initially seems aggravated, but goes to reevaluate the patient. They apologize to the patient for making assumptions about their race and finds that she is much more open than before. She reveals her plan to overdose at school on Friday and they both agree that she would benefit from admission at that time. Following inpatient stabilization and revealing difficulty with racial identity formation, the patient’s mother is encouraged to arrange therapy with a psychotherapist specializing in race conflict. This work builds self-esteem and helps to stabilize her dysregulation. |

Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; CD = conduct disorder; DBT = dialectical behavioral therapy; ED = emergency department; IEP = Individualized Education Program; MDD = major depressive disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SI = suicidal ideation.

Design and implementation of any complex educational intervention, regardless of delivery method, requires significant investment of time and funds, which are often in short supply in racial disparities research. Nonetheless, research in this area, including pilot, feasibility, and acceptability studies, is needed to assess aspects of safety, privacy, and cost-effectiveness and to further develop evidence-based techniques for combating racism in child and adolescent psychiatry. Investigation of which educational frameworks and strategies are most effective to be delivered in digital format will also be important. These interventions warrant more research, but provide a promising arena for testing how the scenarios depicted in Table 1 can be transformed into personally tailored digital content to meet the unique needs of child and adolescent psychiatry providers.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Jansen, Brown, and Xu are supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R25 MH112473–01, of which Dr. Glowinski is the co–principal investigator). These funding sources had no role in the study design, implementation, or interpretation of results. However, the mission of the grant is the recruitment, mentoring, and retention of clinician scientists including underrepresented minority (URM) clinician scientists, which is relevant to this article.

The authors would like to acknowledge Eric Lenze, MD, and Katie Keenoy, MA, for their helpful review of the manuscript and recommendations through a Washington University School of Medicine mHealth Research Core consultation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Drs. Jansen, Brown, Xu, and Glowinski have reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

This article is part of a special series devoted to addressing bias, bigotry, racism, and mental health disparities through research, practice, and policy. The series is edited by Assistant Editor Eraka Bath, MD, Deputy Editor Wanjikũ F.M. Njoroge, Associate Editor Robert R. Althoff, MD, PhD, and Editor-in-Chief Douglas K. Novins, MD.

Contributor Information

Madeline O. Jansen, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri..

Tashalee R. Brown, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.; William Greenleaf Eliot Division of Child Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Kevin Y. Xu, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri..

Anne L. Glowinski, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.; William Greenleaf Eliot Division of Child Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO. UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown TR, Xu KY, Glowinski AL. Cognitive behavioral therapy and the implementation of antiracism. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:819–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:979–987. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birtel MD, Crisp RJ. Psychotherapy and social change: Utilizing principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy to help develop new prejudice-reduction interventions. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1771. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu W Child and adolescent mental disorders and health care disparities: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2011–2012. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28:988–1011. 10.1353/hpu.2017.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu CH, Stevens C, Wong SH, Yasui M, Chen JA. The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among US college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:8–17. 10.1002/da.22830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallinger JB, Lamberti JS. Psychiatrists’ attitudes toward and awareness about racial disparities in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:173–179. 10.1176/ps.2010.61.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatry Association (APA). Task Force on Addressing Structural Racism Throughout Psychiatry Survey. 2020.

- 8.Kronsberg H, Bettencourt AF, Vidal C, Platt RE. Education on the social determinants of mental health in child and adolescent psychiatry fellowships. Acad Psychiatry. 2022;46:50–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soloe C, Burrus O, Subramanian S. The effectiveness of mHealth and eHealth tools in improving provider knowledge, confidence, and behaviors related to cancer detection, treatment, and survivorship care: a systematic review. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36:1134–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alegria M, Nakash O, Johnson K, et al. Effectiveness of the decide interventions on shared decision making and perceived quality of care in behavioral health with multi-cultural patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:325–335. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lentin A Looking as white: Anti-racism apps, appearance and racialized embodiment. Identities. 2019;26:614–630. 10.1080/1070289X.2019.1590026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson JK, Dunn KM, Paradies Y. Bystander anti-racism: A review of the literature. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy. 2011;11:263–284. 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2011.01274.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]