Abstract

Background

Substance use management in hospitals can be challenging. In response, a Canadian hospital opened an overdose prevention site (OPS) where community members and hospital inpatients can inject pre-obtained illicit drugs under supervision. This study aims to: (1) describe program utilization patterns; (2) characterize OPS visits; and (3) evaluate overdose events and related outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed at one hospital in Vancouver, Canada. All community members and hospital inpatients who visited the OPS between May 2018 and July 2019 were included. Client measures included: hospital inpatient status, use of intravenous access line for drug injection, and substances used. Program measures included: number of visits (daily/monthly), overdose (fatal/non-fatal) events and overdose-related outcomes.

Results

Overall, 11,673 OPS visits were recorded. Monthly visits increased from 306 to 1198 between May 2018 and July 2019 respectively. On average, 26 visits occurred daily. Among all visits, 20% reported being a hospital inpatient, and 5% reported using a hospital intravenous access line for drug injection. Opioids (56%) and stimulants (24%) were the most common substances used. Overall 39 overdose events occurred - 82% required naloxone reversal, 28% required transfer to the hospital’s emergency department and none were fatal. Overdose events were more common among hospital inpatients compared to community clients (6.6 vs 2.2 per 1000 visits respectively; p value = 0.046).

Conclusions

This unique OPS is an example of a hospital-based harm reduction initiative. Use of the site increased over time among both groups with no fatal overdose events occurring.

Keywords: Overdose prevention, Supervised consumption, Injection drugs, Harm reduction, Hospital

1. INTRODUCTION

Substance use in the hospital setting is common. Among studies of individuals hospitalized in the United States (US) for injection-related infections, over one-third (34–41%) reported using illicit substances during their hospital stay (Eaton et al., 2020;Fanucchi et al., 2018). Similarly, almost half (44%) of the 1028 people who use illicit drugs and participate in one of two prospective cohort studies in Vancouver, Canada reported illicit drug use in the hospital setting while admitted (Grewal et al., 2015).

Despite the high prevalence of active substance use in acute care settings, many hospitals continue to enforce abstinence-based policies for addiction management. Accordingly, individuals with a substance use disorder (SUD) may resort to the adoption of risky drug use behaviours while hospitalized to adequately treat their pain or withdrawal symptoms (Ti et al., 2015a). Examples of such behaviours may include syringe sharing or using illicit drugs alone (e.g., in hospital washrooms), both of which are known risk factors for adverse health outcomes including infectious disease transmission, overdose and death (McNeil et al., 2014;Ti et al., 2015b). Additionally, people who inject drugs are 4 times more likely to leave hospital against medical advice (AMA) compared to individuals who do not inject drugs (Anis et al., 2002). Leaving hospital AMA is a strong predictor for frequent (and costly) hospital readmissions (Anis et al., 2002;Jeremiah et al., 1995;Palepu et al., 2003) and may result in poor health outcomes (due to inadequate treatment and increased likelihood for antibiotic drug resistance) (Jeremiah et al., 1995;Palepu et al., 2003), as well as contribute to significant disruptions in the therapeutic relationship between patient and provider (Chan et al., 2004).

While efforts to improve access to addiction treatment are underway in some hospital settings (Englander et al., 2019;Wakeman et al., 2017;Weinstein et al., 2018), the implementation of evidence-based harm reduction initiatives may offer a feasible strategy to mitigate the harms associated with ongoing substance use in hospital settings and promote pathways to addiction treatment. An overdose prevention site (OPS) is one example. An OPS is a designated space whereby individuals may inject pre-obtained illicit drugs under supervision. OPS clients are monitored post-injection so that in case of an overdose, a rapid response (e.g., naloxone administration, transfer to emergency department) can be undertaken. OPS’ are also well-positioned to act as a low-barrier entry point for people who inject drugs to access other harm reduction services (e.g., sterile injecting equipment, overdose prevention education), as well as healthcare and social services (including referral to addiction treatment) (Government of British Columbia [BC], 2021). In Canada, OPS’ offer a feasible alternative to supervised consumption services (SCS) at present as they are managed by health authorities (in partnership with community organizations) and do not require municipalities to seek an exemption from federal drug laws (as is required for SCS’) as declared under the province’s existing public health emergency (Government of British Columbia, 2021; Wallace et al., 2019).

Data associated with OPSs at present are scarce. More specifically OPS sites that have been studied to date have not been hospital-based, and evaluations are predominantly limited to proof of concept papers (Shorter et al., 2022;Wallace et al., 2019) or are qualitative-based (Boyd et al., 2018;Foreman-Mackay et al., 2019). SCS’ however have been robustly evaluated and, internationally, have been associated with a number of positive outcomes. Insite, the operation of an SCS in Vancouver, Canada, was associated with a 35% reduction in overdose deaths in its surrounding area (Marshall et al., 2011), a 69% reduced likelihood of sharing needles (Milloy and Wood, 2009), a reduction in the number of syringes discarded in public and public drug use (Wood et al., 2004), and the prevention of 5–6 HIV infections per year (Pinkerton, 2011). Furthermore, no increase in crime, violence, or drug trafficking was observed in the area following the program’s implementation (Wood et al., 2006). Similarly, studies of Australian and European SCS’ observed a reduction in injection-related waste in the surrounding areas of the SCS (Hedrich, 2004; Salmon et al., 2007). One Australian-based SCS demonstrated a 68% reduction in overdose related ambulance calls during the facility’s operational hours (Salmon et al., 2010; van Beek et al., 2004), as well no increase in local drug-related crime, violence, and trafficking (Fitzgerald et al., 2010; Freeman et al., 2005).

While generalizability of these findings to hospital settings is unknown, the actual feasibility of implementing an OPS in a hospital setting and characterizing its use is a critical first step that, to our knowledge, has not yet been described.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Design

The Thomus Donaghy OPS at St. Paul’s Hospital (SPH) in Vancouver, Canada was implemented in May 2018. A retrospective review of the OPS’ online database was undertaken during the initial 15 months of the program (May 2018 - July 2019) to: (1) describe utilization patterns of the program; (2) characterize visits to the OPS; and (3) evaluate fatal and nonfatal overdose events and other related outcomes occurring at the OPS over the study period.

2.2. Setting

SPH is an acute care hospital located in downtown Vancouver, Canada. The hospital is close to Vancouver’s downtown eastside neighbourhood – an area severely impacted by poverty, homelessness, mental illness and substance use. To our knowledge, the SPH OPS is the only hospital-based OPS in Canada. While one other similar service exists at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Alberta, Canada it has a federal exemption to operate as a formal supervised consumption service (Dong et al., 2020). The SPH OPS is small with just 4 injecting booths and overdose response is provided exclusively by peer support specialists (i.e., individuals with lived or living experience). The site is funded by a local health authority (Vancouver Coastal Health), is operated by Rain City Housing (a Vancouver-based non-profit organization) and is open 11 am-10:30 pm seven days a week. Harm reduction supplies and drug testing services are also available at the site, as are referrals to addiction treatment and other health and social services.

2.3. Sample and measurements

SPH’s OPS is available for use by any individual who injects drugs. The facility provides a witnessed setting for the injection of substances for both hospital inpatients and community clients. Data was populated from visitor self-report and peer-support worker entries during check-in and check-out from the site on a per visit basis. Client measures included: hospital inpatient status, intravenous access line used for injection drug use (i.e., whereby a participant injects drugs into an existing intravenous catheter in situ), and substances used at the OPS. Program measures included: number of visits (daily and monthly) and overdose (fatal and non-fatal) events and outcomes over time. Rates of use were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Differences in overdose rates between user groups were analyzed using Fisher’s Exact Test (performed on STATA/MP 15.1).

This project was completed as part of a clinical service evaluation and was deemed exempt from requiring approval by the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care in Vancouver Canada.

3. RESULTS

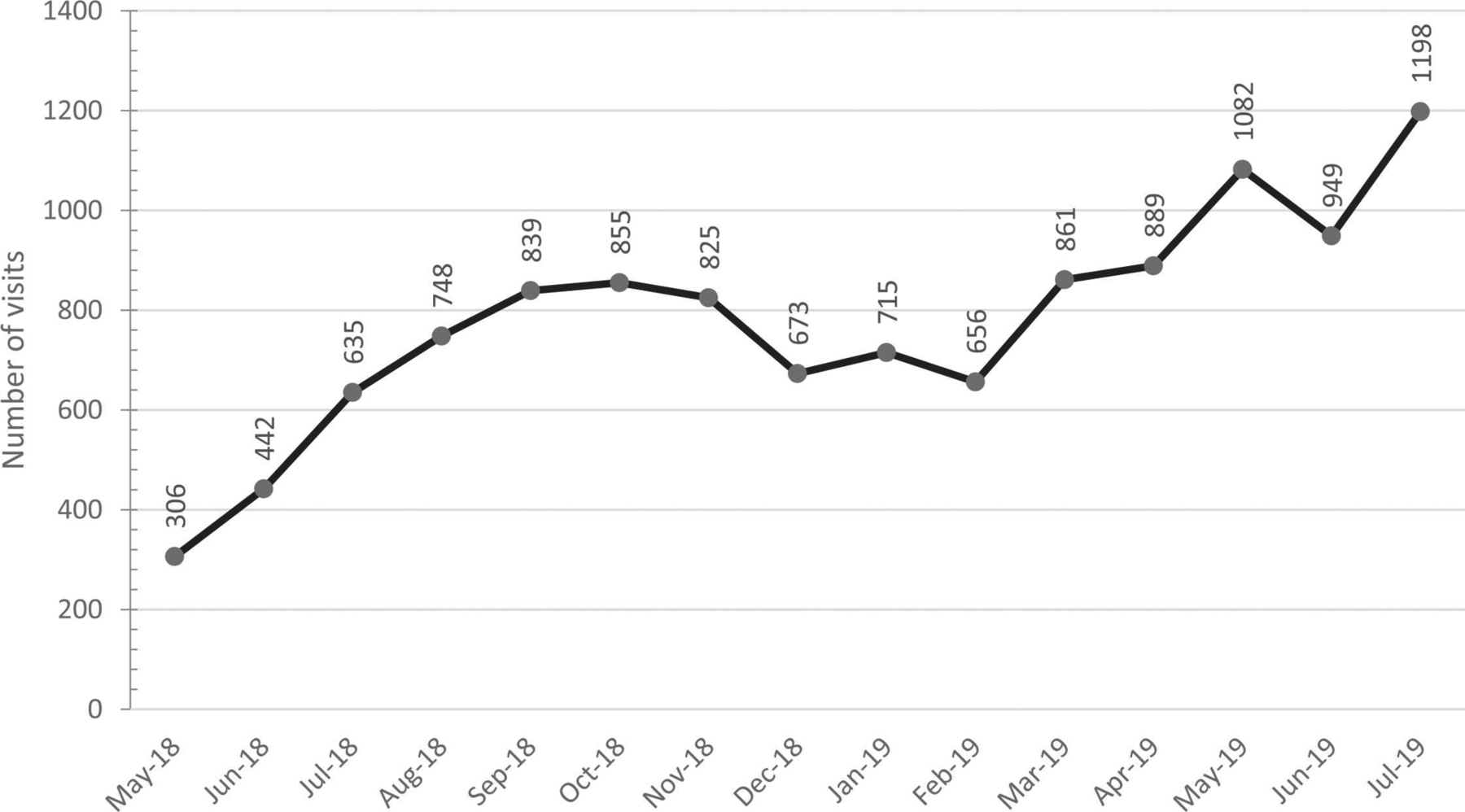

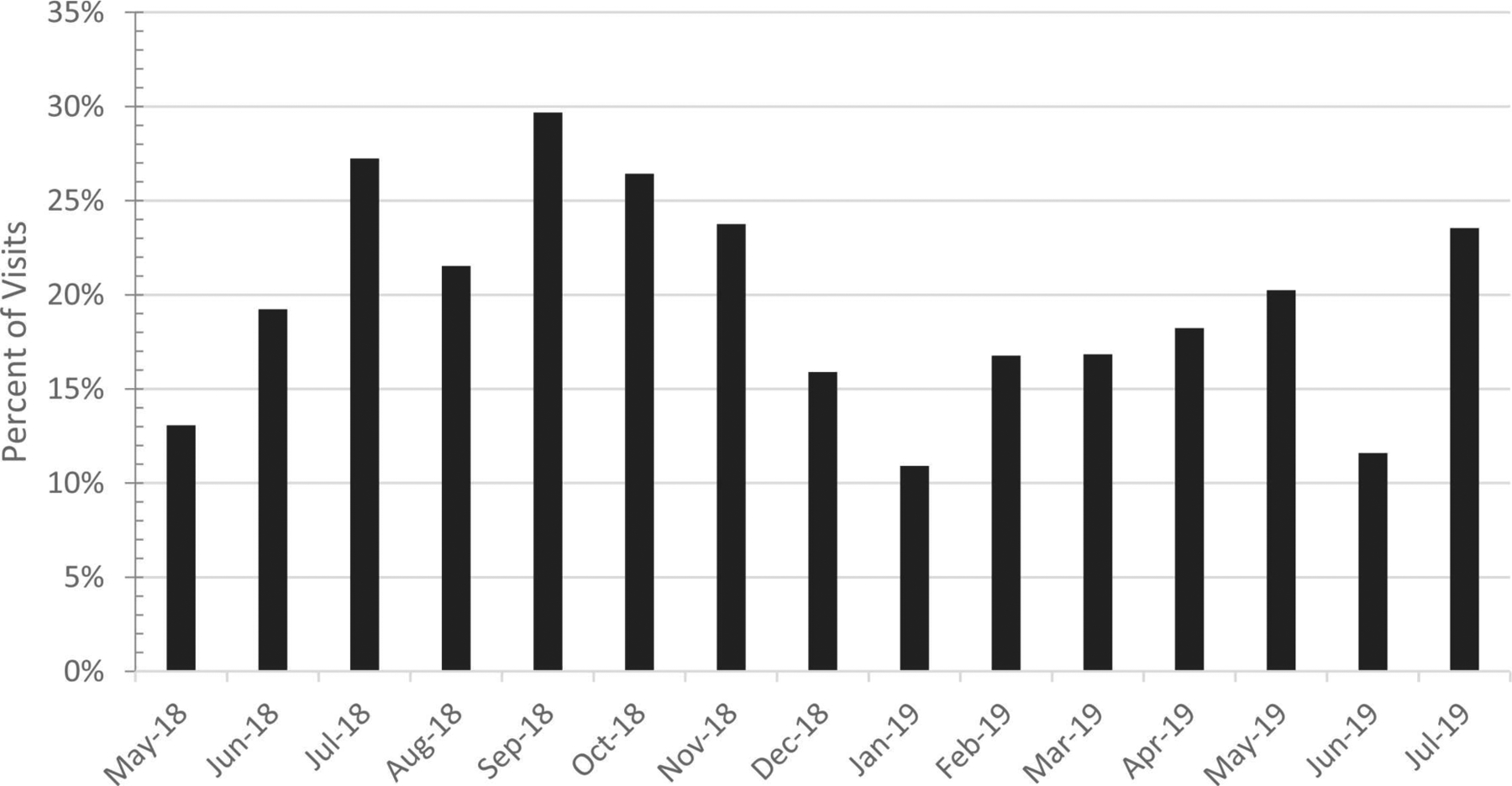

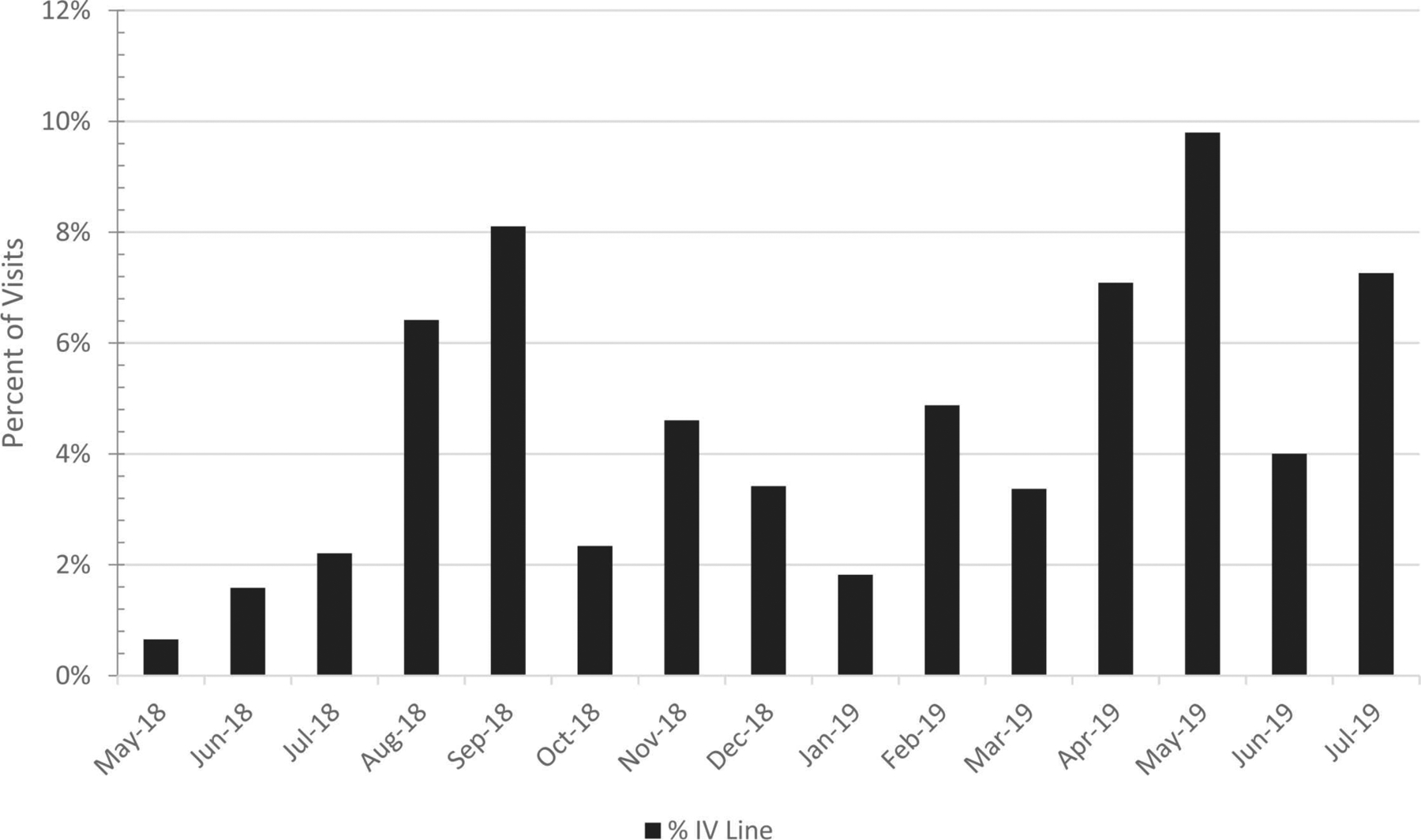

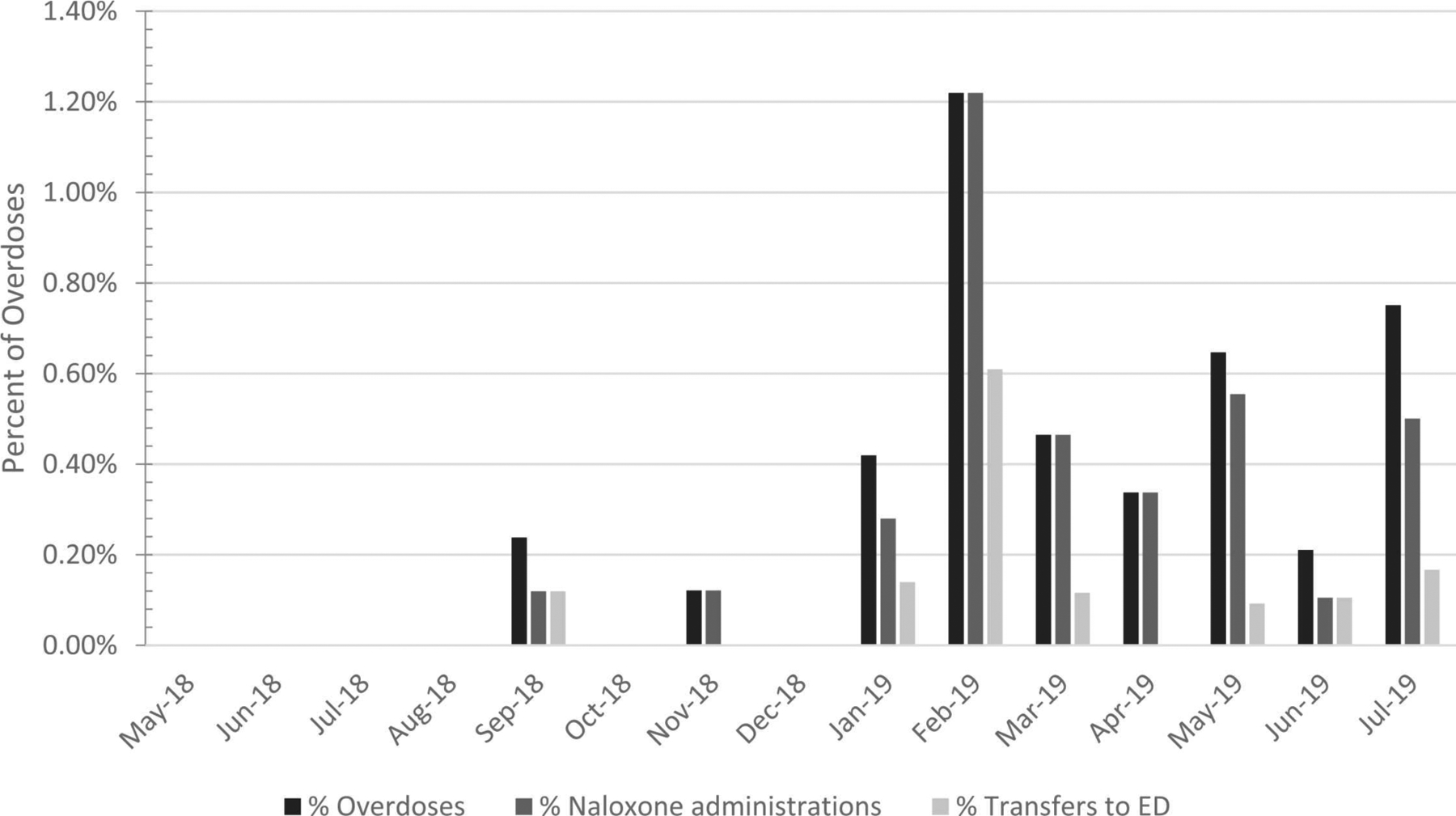

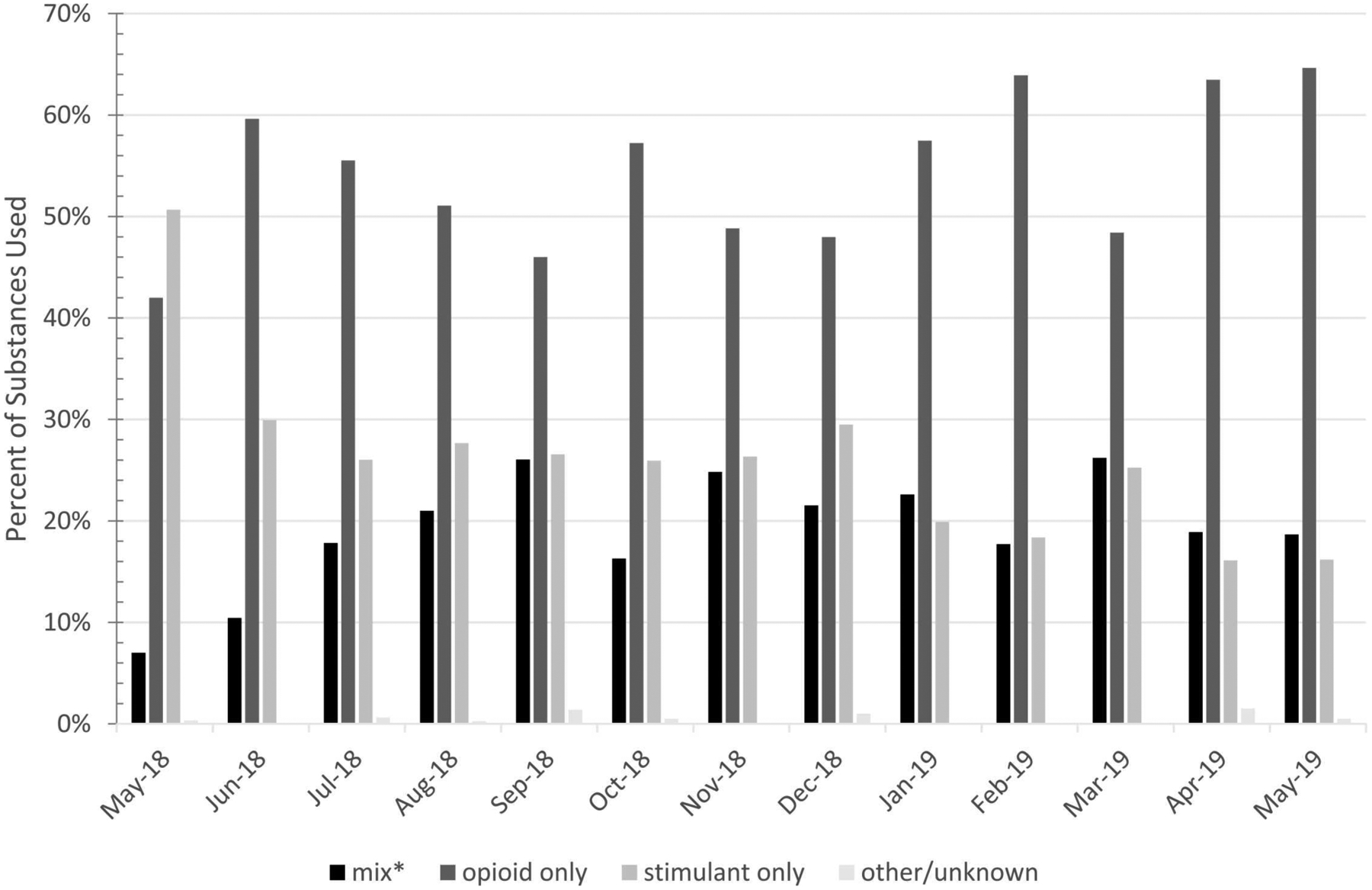

Between May 2018 and July 2019 a total of 11,673 visits to the hospital’s OPS were recorded. The monthly number of site visits more than tripled in just over a year, with 306 visits in May 2018 (at program inception) to 1198 visits in July 2019 (Fig. 1). On average, the site observed 26 visits per day (range 1–58). Among all OPS visits, 2343 (20%) reported being an inpatient of the hospital with this number increasing over time (13% in May 2018 compared to 24% in July 2019) (Fig. 2). A hospital issued intravenous access line was reportedly used for the injection of drugs in 588 visits during the study period (5% of overall visits) (Fig. 3). A total of 39 overdoses were recorded at the hospital OPS, which represents approximately 0.3% of overall visits. Naloxone was administered in 32 of the overdose events (82%), while 11 overdose events (28%) required a transfer to the hospital’s emergency department and no overdoses were fatal (Fig. 4). Of note, hospital inpatients experienced significantly more overdose events compared to community clients (6.6 vs 2.2 per 1000 visits respectively; 95% confidence intervals: 3.4–11.5 per 1000 visits and 1.2–3.7 per 1000 visits respectively; p value = 0.046). No statistically significant difference was found in the need for naloxone administration and/or transfer to the hospital’s emergency department for overdose events between community clients or hospital inpatients (p value = 0.153). Substance use data was only recorded for the first year of operation (May 2018 – May 2019). Opioids and stimulants were the most common substances used at 56% and 24% respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 1.

Total number of monthly visits to the St. Paul’s Hospital’s Overdose Prevention Site (SPH OPS), Vancouver, Canada (May 2018 – July 2019).

Figure 2.

Percentage of monthly visits to the St. Paul’s Hospital’s Overdose Prevention Site (SPH OPS) by hospital inpatients, Vancouver, Canada (May 2018 – July 2019).

Figure 3.

Percentage of monthly visits where a hospital-issued intravenous access line was reported to have been used for the injection of drugs at the St. Paul’s Hospital’s Overdose Prevention Site (SPH OPS), Vancouver, Canada (May 2018 – July 2019).

Figure 4.

Percentage of monthly visits resulting in an overdose event recorded at the St. Paul’s Hospital Overdose Prevention Site (SPH OPS) and responses taken, Vancouver, Canada (May 2018 – July 2019).

Figure 5.

Substances Used at the St. Paul’s Hospital Overdose Prevention Site e (SPH OPS), VancouVancouver, Canada (May 2018 – May 2019). *mix: any drug mixture that was not solely opioid or stimulant.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study describes the utilization patterns of a hospital-based OPS. Use of the site increased over time with monthly visits more than tripling over the study period. Opioids were the most commonly used substance and there was a small percentage of visits in which a hospital issued intravenous access line was used for the injection of drugs. No fatal overdoses were observed and there was significantly more overdose events among hospital inpatients compared to community clients.

Increased use of the OPS over time by both community clients and hospital inpatients suggests a general demand exists for this type of harm reduction service. This is consistent with observations in other settings. BC, for example, declared a public health emergency due to the unprecedented number of overdose deaths in April 2016. This facilitated the rapid sanctioning, implementation and rapid scale-up of OPS’ provincially - with over 20 being established within the first year resulting in 550,000 visits and no overdose deaths (Wallace et al., 2019). At present, it is estimated that more than 120 OPS’ are operational (either sanctioned or unsanctioned) in over 10 countries internationally (Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Switzerland and the United States) (Drug Policy Alliance, 2021).

While our findings further support the notion that OPS’ are in demand, its nuance pertains to the appetite that exists for this type of harm reduction intervention specifically among individuals admitted to hospital. Globally, we are aware of 5 supervised consumption services that are located in an acute care setting. Three of these are located in Europe (Paris and Strasbourg in France and Barcelona in Spain) but offer services only to outpatients - despite being located on hospital grounds (Daigre et al., 2010;Jauffret-Roustide, 2016). The Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton, Alberta obtained a federal exemption to operate as a formal supervised consumption service in 2018 and provides services exclusively to hospital inpatients (Dong et al., 2020). The SPH OPS is unique in that it operates without a federal exemption (as sanctioned by the province’s ongoing public health emergency) and, as previously described, offers services to both hospital inpatients and community clients.

Use of the hospital-OPS increased among inpatients in our study over time, indicating high and growing demand for this service. These findings are consistent with a 2015 needs assessment that reported over two-thirds (68%) of 732 people who use drugs would be willing to access an in-hospital supervised injecting facility (Ti et al., 2015b). Similarly, a 2021 study demonstrated 76% of individuals (n = 70) at a Toronto-based specialty HIV hospital were also supportive of implementing a supervised injection service for inpatient use (Rudzinski et al., 2021). Though the trend of use over time has not been reported for Alberta’s hospital-based SCS, the site observed 7856 visits in the first 20 months of operation (Dong et al., 2020). Given increasing uptake of services, with no overdose deaths, a hospital-based OPS appears to offer a feasible and acceptable option for individuals to safely consume illicit drugs while hospitalized.

Hospital inpatients who accessed the study’s OPS were found to be at significantly higher risk for experiencing a nonfatal overdose compared to community clients. Though more research is needed to further explore reasons for this, potential explanations may include: (1) a loss of tolerance due to hospitalization resulting in an overestimation of safe amounts for use; (2) acute illness; or (3) concurrent opioid (or other sedatives) prescribed in hospital for acute pain or withdrawal management (including opioid agonist therapy such as methadone maintenance treatment) – all of which may increase one’s risk for an overdose (Peles et al., 2010;Strang et al., 2003;Tjagvad et al., 2016). Several strategies could be implemented to mitigate this risk. More specifically, identification of hospital inpatients at the time of OPS check-in may help flag those at increased overdose risk so OPS staff can provide enhanced monitoring. Additionally, peer support specialists (trained in overdose response) could be routinely integrated as part of the hospital’s health care team to facilitate the safe transfer of inpatients between the hospital and OPS. Lastly, cross communication between OPS staff and hospital prescribers regarding inpatient overdose events (without adopting a punitive approach to care) may help to inform the development and revision of addiction treatment plans that are both safe and effective for patients.

Approximately 5% of overall visits to the study’s OPS reported using a hospital issued intravenous access line for injection drug use. These findings are consistent with other studies. More specifically, Alberta’s hospital-based supervised consumption service also reported 5% of patients used their intravenous catheters for injection drug use (Dong et al., 2020). Further, a review of 10 international studies of outpatient antibiotic therapy that included 800 individuals who inject drugs demonstrated tampering or misuse of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in 4 studies (prevalence ranged between 0% and 2%) (Suzuki et al., 2018). While difficult to ascertain in our study if use of the hospital issued catheters for injection drug use occurred exclusively among hospital inpatients (e.g., may include community clients who are undergoing outpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy, or those who left hospital AMA with their hospital intravenous line in-situ), the actual intravenous line used at the OPS was confirmed to be issued in a hospital setting. Few studies explore this practice or outcomes related to it. Two studies in particular have compared venous access adverse events among those who did and did not inject drugs (n = 198 total) and neither found a statistically significant difference in the development of line infections (Dobson et al., 2017;Vazirian et al., 2018). Further, one US-based study interviewed 33 people who use drugs and were admitted to hospital with a PICC. Overall, 94% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “the PICC line makes you desire to inject drugs through it” and 97% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “the PICC line makes your cravings worse” (Fanucchi et al., 2018). Further research investigating potential reasons for use of a hospital issued intravenous catheter for injection drug use in an OPS setting and outcomes related to this are urgently needed.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, our findings represent access and use at one hospital-based OPS over time and may therefore not be generalizable to other acute care settings. Second, data from the OPS was collected per visit (not per person), limiting its ability for interpretation on an individual patient or client level. Thirdly, substance use data was not specifically linked to individual visit data thus limiting our ability to determine if overdose events may have been associated with specific type of substance used. Lastly, our study’s data was self-report and may not be entirely representative as participants may have been hesitant to disclose certain details (e.g., use of hospital-issued PICC line for injection drug use). Despite this, our study does demonstrate the demand that exists for this harm reduction intervention among hospitalized individuals and the successful management of overdose events that can be achieved if regulatory and other barriers to implementation (e.g., stigma) can be removed.

4.2. Conclusions

The SPH OPS is a unique example of a hospital-based harm reduction intervention. Use of the site increased over time among both community clients and hospital inpatients, with no fatal overdose events observed. Consideration should be given for the implementation of OPS’ in other acute care settings as a way to mitigate the harms associated with ongoing substance use in a hospital setting. Furthermore, additional research should be undertaken to explore the impact of OPS’ on health outcomes among hospital inpatients (e.g., ongoing illicit drug use in hospital, AMA discharges, hospital catheter use for drug injection) as well as the impacts of the program on hospital wide concerns (e.g., discarded needles, visible injection drug use and overdoses on hospital wards).

HIGHLIGHTS.

Substance use management in hospitals can be challenging.

To address this, one Canadian hospital opened an Overdose Prevention Site (OPS).

Between May 2018 and July 2019, 11,673 visits occurred at the OPS.

39 overdose events occurred – 82% required reversal with naloxone.

Use of the OPS increased over time and no fatal overdoses occurred.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Raincity Housing, Vancouver Coastal Health and St. Paul’s Hospital for their commitment to operationalizing the Thomus Donaghy OPS and for providing data for this manuscript. We would also like to thank clients of the Thomus Donaghy OPS for their contributions to this research, as well as current and past staff at the facility.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Samantha Young is supported by the Research in Addiction Medicine Scholars Program funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) [#R25DA033211]. Evan Wood is supported by the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Addiction Medicine. Dr. Wood is also the Chief Medical Officer of Numinus Wellness a mental health company focussed on psychedelic medicines. Seonaid Nolan is financially supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the University of British Columbia’s Steven Diamond Professorship in Addiction Care Innovation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Evan Wood is the Chief Medical Officer of Numinus Wellness a mental health company focussed on psychedelic medicines.

REFERENCES

- Anis AH, Sun H, Guh DP, Palepu A, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV: Leaving hospital against medical advice among HIV-positive patients. CMAJ 2002; 167: pp. 633–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Collins JB, Mayer S, Maher L, Kerr T, McNeil R: Gendered violence and overdose prevention sites: a rapid ethnographic study during an overdose epidemic in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction 2018; 113: pp. 2261–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan ACH, Palepu A, Guh DP, Sun H, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. : HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospitals against medical advice. The mitigating role of methadone and social support. JAIDS 2004; 35: pp. 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigre C, Comin M, Rodriguez-Cintas L, et al. : Users’ perception of a harm reduction program in an outpatient drug dependency treatment center. Gac. Sanit 2010; 24: pp. 446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson PM, Loewenthal MR, Schneider K, Lai K: Comparing injecting drug users with others receiving outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Open Forum Infect. Dis 2017; 4: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong K, Brouwer J, Johnston C, Hyshka E: Supervised consumption services for acute care hospital patients. CMAJ 2020; 192: E476–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Policy Alliance, 2021. Overdose Prevention Centres [Internet]. https://drugpolicy.org/issues/supervised-consumption-services (Accessed December 2021).

- Eaton E, Westfall A, McClesky B, Paddock C, Lane P, Cropsey K, et al. : In-hospital illicit drug use and patient directed discharge: barriers to care for patients with injection-related infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis 2020; 7: ofaa74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, Nicolaidis C, Graven P, Dorfman C, et al. : Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity matched analysis. J. Gen. Intern Med 2019; 34: pp. 2796–2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanucchi L, Lofwall M, Nuzzo PW: In-hospital illicit drug use, substance use disorders, and acceptance of residential treatment in a prospective pilot needs assessment of hospitalized adults with severe infections from injecting drugs. J. Subst. Abus. Treat 2018; 92: pp. 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Burgess M, Snowball L, 2010. Trends in Property and Illicit drug crime around the Medically Supervised Injecting Centre in Kings Cross: An update. Crime and Justice Statistics [Internet]. https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Publications/BB/bb51.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackay A, Bayoumi AM, Miskovic M, Kolla G, Strike C: ‘It’s our safe sanctuary’: experiences of using an unsanctioned overdose prevention site in Toronto, Ontario. Int J. Drug Policy 2019; 73: pp. 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, Jones CGA, Weatherburn DJ, Rutter S, Spooner CJ, Donnelly N: The impact of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre (MSIC) on crime. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005; 24: pp. 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of British Columbia, 2021. Overdose prevention. [Internet]. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/overdose/what-you-need-to-know/overdose-prevention.

- Grewal H, Ti L, Hayashi K, Dobrer S, Wood E, Kerr T: Illicit drug use in acute care settings. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015; 34: pp. 499–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D, 2004. European report on drug consumption rooms [Internet]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/34710918.pdf (Accessed May 29, 2021).

- Jauffret-Roustide M: Les salles de consummation à moindre risque: apprendre à vivre avec les drogues. Esprit 2016; 429: pp. 115–123. (Novembre; n°) [Google Scholar]

- Jeremiah J, O’Sullivan P, Stein MD: Who leaves against medical advice?. JGIM 1995; 10: pp. 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BD, Milloy MJ, Wood E, Montaner JS, Kerr T: Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet 2011; 377: pp. 1429–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T: Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethnoepidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc. Sci. Med 2014; 105C: pp. 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Wood E: Emerging role of supervised injecting facilities in human immunodeficiency virus prevention. Addiction 2009; 104: pp. 620–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Sun H, Kuyper L, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, Anis AH: Predictors of early hospital readmission in HIV-infected patients with pneumonia. JGIM 2003; 18: pp. 242–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Schreiber S, Adelson M: 15-Year survival and retention of patients in a general hospital-affiliated methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) center in Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010; 107: pp. 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton SD: How many HIV infections are prevented by Vancouver Canada’s supervised injection facility?. Int J. Drug Policy 2011; 22: pp. 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzinski K, Xavier J, Guta A, Carusone SC, King K, Phillips JC, et al. : Feasibility, acceptability, concerns, and challenges of implementing supervised injection services at a specialty HIV hospital in Toronto, Canada: perspectives of people living with HIV. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: pp. 1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon AM, Thein HH, Kimber J, Kaldor JM, Maher L: Five years on: What are the community perceptions of drug-related public amenity following the establishment of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre?. Int J. Drug Policy 2007; 18: pp. 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon AM, Van Beek I, Amin J, Kaldor J, Maher L: The impact of a supervised injecting facility on ambulance call-outs in Sydney, Australia. Addiction 2010; 105: pp. 676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter GW, Harris M, McAuley A, Trayner KM, Stevens A: The United Kingdom’s first unsanctioned overdose prevention site; a proof of concept evaluation. Int J. Drug Policy 2022; 104: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, et al. : Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: follow up study. BMJ 2003; 326: pp. 959–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Johnson J, Montgomery M, Hayden M, Price C: Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy among people who inject drugs: A review of the literature. Open Forum Infect. Dis 2018; 5: pp. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ti L, Voon P, Dobrer S, Montaner J, Wood E, Kerr T: Denial of pain medication by health care providers predicts in-hospital illicit drug use among individuals who use illicit drugs. Pain. Res Manag 2015; 20: pp. 84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ti L, Buxton J, Harrison S, Dobrer S, Montaner J, Wood E, et al. : Willingness to access an in-hospital supervised injection facility among hospitalized people who use illicit drugs. J. Hosp. Med 2015; 10: pp. 301–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjagvad C, Skurtveit S, Linnet K, Andersen LV, Christoffersen DJ, Clausen T: Methadonerelated overdose deaths in a liberal opioid maintenance treatment programme. Eur. Addict. Res 2016; 22: pp. 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek I, Kimber J, Dakin A, Gilmour S: The Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre: reducing harm associated with heroin overdose. Crit. Public Health 2021; 14: pp. 391–406. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09581590400027528 [Google Scholar]

- Vazirian M, Jerry JM, Shrestha NK, Gordon SM: Outcomes of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in patients with injection drug use. Psychosomatics 2018; 59: pp. 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA: Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J. Gen. Intern. Med 2017; 32: pp. 909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B, Pagan F, Pauly B: The implementation of overdose prevention sites as a novel and nimble response during an illegal drug overdose public health emergency. Int J. Drug Policy 2019; 66: pp. 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein Z, Wakeman S, Nolan S: Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin. North Am 2018; 102: pp. 587–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Marsh DC, Montaner JSG, et al. : Changes in public order after the opening of a medically supervised safer injecting facility for illicit injection drug users. Cmaj 2004; 171: pp. 731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Lai C, Montaner JSG, Kerr T: Impact of a medically supervised safer injecting facility on drug dealing and other drug-related crime. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2006; 1: pp. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]