Abstract

In humans, skin blood flux (SkBF) and eccrine sweating are tightly coupled, suggesting common neural control and regulation. This study was designed to separate these two sympathetic nervous system end-organ responses via nonadrenergic SkBF-decreasing mechanical perturbations during heightened sudomotor drive. We induced sweating physiologically via whole body heat stress using a high-density tube-lined suit (protocol 1; 2 women, 4 men), and pharmacologically via forearm intradermal microdialysis of two steady-state doses of a cholinergic agonist, pilocarpine (protocol 2; 4 women, 3 men). During sweating induction, we decreased SkBF via three mechanical perturbations: arm and leg dependency to engage the cutaneous venoarteriolar response (CVAR), limb venous occlusion to engage the CVAR and decrease perfusion pressure, and limb arterial occlusion to cause ischemia. In protocol 1, heat stress increased arm cutaneous vascular conductance and forearm sweat rate (capacitance hygrometry). During heat stress, despite decreases in SkBF during each of the acute (3 min) mechanical perturbations, eccrine sweat rate was unaffected. During heat stress with extended (10 min) ischemia, sweat rate decreased. In protocol 2, both pilocarpine doses (ED50 and EMAX) increased SkBF and sweat rate. Each mechanical perturbation resulted in decreased SkBF but minimal changes in eccrine sweat rate. Taken together, these data indicate that a wide range of acute decreases in SkBF do not appear to proportionally decrease either physiologically- or pharmacologically induced eccrine sweating in peripheral skin. This preservation of evaporative cooling despite acutely decreased SkBF could have consequential impacts for heat storage and balance during changes in body posture, limb position, or blood flow restrictive conditions.

Keywords: limb dependency, skin blood flux, sweat glands, venoarteriolar response

INTRODUCTION

The maintenance of internal temperature in humans during heat stress is contingent on the coupling of skin-surface evaporation and vasodilation to offload generated and passively gained heat. Thus, optimal and proportional matching of sweating to skin blood flux (SkBF) would appear to be essential and thus tightly regulated. Supporting this thermoregulatory effector coupling, clinical data from patients with anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (1) and pharmacological data utilizing an acetylcholine vesicle release inhibitor (2) indicate that absence of sweat glands or blocking sudomotor signals abates active cutaneous vasodilation, respectively. Abating vasodilation in turn also affects sweating, as sustained local ischemia decreases sweat function (3–6).

Because coupling is not strictly an “on” versus “off” phenomenon, other investigators have attempted to alter one parameter or the other, with varying levels of success. Pharmacological reductions in local SkBF using an adrenergic agonist (norepinephrine) attenuate sweating increases during a systemic heat stress (7). However, this standard method of decreasing SkBF likely also engaged receptors on the eccrine sweat gland (8). Alternately, Ravanelli et al. (9) identified an inflection point difference between onset of sweating and vasodilation. This indicates a potential difference in timing of sudomotor and vasomotor signal to effector transduction but does not address the extent of coupling of these two thermoregulatory effectors. Cramer et al. (10) utilized an iso-osmotic hypovolemia perturbation to decrease SkBF while maintaining sweat rate. This unique approach engages the systemic baroreflex to alter vaso- but not sudomotor activity. Although this approach is insightful, one cannot exclude the possibility that systemic changes are acting on more than these cutaneous thermoregulatory effector responses. Thus, the precise relationships between moderate and acute changes in SkBF on sweat function are still unclear.

Considering the above experimental difficulties, uncoupling the two responses appears to require modulating SkBF during high sudomotor drive via nonpharmacologic and nonsystemic means. Local venous distention, such as what occurs during limb dependency or venous occlusion, causes vasoconstriction of muscle, subcutaneous adipose tissue, and skin in a manner that is independent of central neural control (11–13). This local venous distention reflex is blocked by local anesthetics but is independent of local and systemic adrenergic blockade (14, 15) and is mediated by venoarteriolar and myogenic reflexes (16). Thus, venoarteriolar and myogenic reflex vasoconstriction appear to provide an experimental approach to alter SkBF via nonpharmacologic and nonsystemic mechanisms.

In the present study, our primary aim was to uncouple these sympathetic nervous system cutaneous end-organ responses by inducing eccrine sweating while decreasing peripheral SkBF. Our secondary aim was to assess the robustness of the observed responses by repeating perturbations and measures in the leg as well as the arm. We accomplished our primary aim via three mechanical nonadrenergic perturbations: 1) limb dependency; 2) limb venous occlusion via cuff inflation to supra-venous pressure; and 3) limb arterial occlusion via cuff inflation to supra-arterial pressure. We performed these perturbations during induction of eccrine sweating both physiologically via whole body heat stress (protocol 1) and pharmacologically via two steady-state doses of local cholinergic agonist (pilocarpine) (protocol 2). We hypothesized that compared with the sweat-inducing protocol alone, 1) reducing SkBF via limb dependency and limb venous occlusion during physiologic and pharmacologic sweat induction will result in attenuated sweat rate and 2) eliminating SkBF via limb arterial occlusion during physiological and pharmacological sweat induction will result in abated sweating.

METHODS

Participants

Six healthy participants [4 male and 2 female (self-identified); age 26 ± 1 yr, height 171 ± 6 cm, weight 72 ± 23 kg, and body mass index (BMI) 24 ± 4 kg/m2; mean ± SD] completed protocol 1 (physiological sweat induction). Seven healthy participants (3 male and 4 female; age 24 ± 1 yr, height 175 ± 10 cm, and weight 81 ± 22 kg, and BMI 26 ± 6 kg/m2; mean ± SD) completed protocol 2 (pharmacological sweat induction). Three individuals participated in both studies, separated by at least 48 h. An additional three unique participants were recruited to perform various control experiments such as the extended time protocol (protocol 2b). Using β = 0.80 and α = 0.05 and effect size from a previous study (17), we estimated a sample size of six participants to be sufficient to detect a difference in sweat rate (18). We assessed participant health by medical history and physical exam, including a 12-lead electrocardiogram for protocol 1. Participants were nonsmokers, nondiabetic, nonhypertensive (<140/90 mmHg), not severely obese (BMI <35 kg/m2); free from known neural, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or muscular complications or diseases; and not taking any medication or supplement that would affect neural, cardiovascular, or muscular responses. We instructed participants to refrain from alcohol, caffeine, and vigorous physical activity for 24 h and from food intake for 2 h before testing. Participants provided a urine sample upon arrival before instrumentation to assess hydration status; if a participant’s urine specific gravity was >1.030, we rescheduled the participant. In addition, we assessed participants’ vital signs (arterial blood pressure, heart rate, oral temperature, and pulse oximetry; Carescape V100, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) at that time. If vital signs were not within normal ranges or were not comparable to those obtained during the health history and physical exam, we rescheduled the participant. All participants were euhydrated before the start of experimentation. Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before participating in this study. The protocol and informed consent were approved by the Marian University Institutional Review Board (B17.002) and conformed to the articles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: physiological sweat induction.

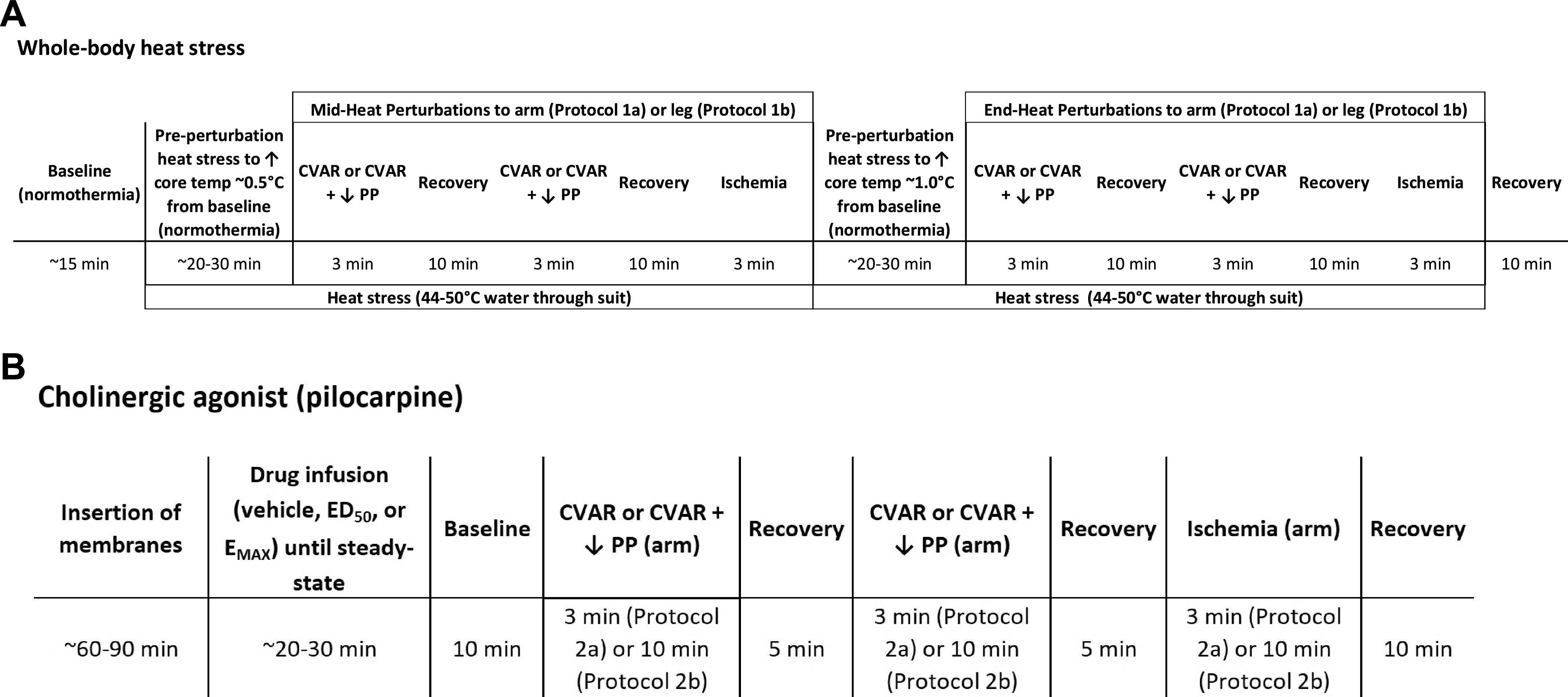

To determine the effect of reduced skin perfusion on whole body heat stress-induced eccrine sweating, we used three mechanical perturbations (limb dependency, venous occlusion, and arterial occlusion) that each reduce SkBF by a different dose and combined mechanism. After a ∼15-min baseline normothermia period, participants underwent one mechanical SkBF perturbation series. Following this normothermic perturbation series, participants underwent whole body heat stress. Participants underwent a second perturbation series at the heat stress midpoint (+0.5°C) and a third at the heat stress completion (+1.0°C). A 15-min recovery period followed the heat stress or normothermic control time period. Figure 1A depicts the protocol 1 timeline.

Figure 1.

Protocol timeline for protocol 1: physiological sweat induction (A) and protocol 2: pharmacological sweat induction via the cholinergic agonist pilocarpine (B). For protocols 1 and 2, cutaneous venoarteriolar response (CVAR) was induced via limb dependency of ∼30 cm below heart level, CVAR plus decreased perfusion pressure (CVAR + ↓ PP) was induced via proximal cuff inflation to ∼45 mmHg, and ischemia was induced by proximal cuff inflation to ∼200 mmHg.

Mechanical SkBF perturbation series.

A series consisting of the following three left arm perturbations was completed in a partially randomized and counterbalanced order (1 and 2, with 3 always occurring last): 1) CVAR: limb dependency (forearm lowered ∼30 cm from heart level) to engage the CVAR; 2) CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure: venous occlusion via upper arm cuff (SC10, Hokanson, Bellevue, WA) inflation to ∼45 mmHg (E20, Hokanson) to engage the CVAR and to decrease perfusion pressure; and 3) ischemia: arterial occlusion via the same upper cuff inflation system to ∼200 mmHg to cause circulatory arrest. Arterial occlusion was the final perturbation in the series because of the potential for prolonged SkBF and sweat gland recovery times following occlusion and reactive hyperemia (3). We maintained each perturbation for 3 min with a recovery period of at least 10 min between perturbations.

Whole body heat stress.

We established normothermia and heat stress conditions by pumping neutral (34°C) and hot (44–50°C) water through a high-density tube-lined suit (Med-Eng Systems, Ottawa, Canada) to either maintain internal temperature or increase it by ∼0.5°C and then ∼1.0°C. The upper range of hot water was used during active warming periods, and the lower range was used to reduce the rise in temperature during data collection. We averaged hemodynamic and thermal data during both normothermic and heat stress periods while the participant rested quietly in the supine position.

Protocol 1b: limb comparisons.

To verify the effect of reduced skin perfusion on whole body heating-induced eccrine sweating in areas that could have exaggerated postural effects (15, 16), we also separately performed three mechanical perturbations in the left leg. These included 1) limb dependency (leg lowered ∼30 cm from heart level); 2) venous occlusion via upper leg cuff (CC17, Hokanson) inflation to ∼45 mmHg (E20, Hokanson); and 3) arterial occlusion via the same upper leg inflation system to ∼200 mmHg.

Repeatability.

We repeated both arm and leg venous occlusion via proximal cuff inflations to ∼45 mmHg to reengage the CVAR and to decrease perfusion pressure in two of the protocol 1 participants to ensure that multiple inductions of the CVAR did not affect subsequent CVAR responses. In these participants, we identified consistent results for both arm and leg venous occlusion, indicating that repeated CVAR does not appear to alter subsequent responses (data not shown).

Protocol 2: pharmacological sweat induction with acute SkBF reduction.

To determine the effect of reduced skin perfusion on pilocarpine-induced eccrine sweating, we placed three intradermal microdialysis membranes (MD-2000, BASi, West Lafayette, IN) in dorsal left forearm skin to perfuse two doses of the cholinergic agonist pilocarpine nitrate [0.01 and 1.66 mg/mL, corresponding to the ED50 and EMAX from previous dose-response modeling (17); Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO] or vehicle (lactated Ringer’s, Baxter, Deerfield, IL) with randomization of forearm site. In brief, membranes were inserted without analgesia via a small diameter needle (25 G, Baxter) and subsequently connected to a 1 mL syringe pump (SP101i, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) set at 5 µL/min flow rate. A baseline period of 60–90 min after membrane insertion allowed for abatement of the local histamine response (19).

Mechanical SkBF perturbation series.

Forearm SkBF was decreased by engaging a similar series of mechanical perturbations as protocol 1 in a partially randomized and counterbalanced order (1 and 2, with 3 always occurring last) for 3 min each with a recovery period of 5 min in between: 1) CVAR (forearm lowered ∼30 cm from heart level); 2) CVAR plus a decrease in perfusion pressure (venous occlusion by proximal cuff inflation); and 3) followed by ischemia (arterial occlusion by proximal cuff inflation). Figure 1B depicts the protocol 2 timeline.

Protocol 2b: pharmacological sweat induction with extended SkBF reduction.

To verify the effect of prolonged versus acute reductions in skin perfusion on pilocarpine-induced eccrine sweating, we repeated protocol 2 on three additional participants. We extended the SkBF reductions to 10 min for arm drop, venous occlusion, and arterial occlusion perturbations. A 10-min recovery period separated each perturbation.

Measurements

We measured eccrine sweat rate via capacitance hygrometry. Briefly, this involved perfusing compressed medical air (200 mL/min) across the skin surface through a custom ventilated chamber (0.6 cm2 chamber window) connected in series with a sensitive humidity sensor (RH-300, Sable Instruments, Las Vegas, NV) with three measurement chambers placed in close proximity to the laser-Doppler probes on uncovered dorsal forearm or shin skin.

We measured skin temperature via thermocouples (T-type, Omega Engineering, Norwalk, CT, connected to a meter, TC-2000, Sable Instruments) placed on skin areas covered and uncovered by the tube-lined suit in protocol 1 and near the microdialysis membranes in protocol 2. We used uncovered skin temperature in data analysis. We calculated mean skin temperature using the weighted average of four thermocouples attached to the skin (20). For protocol 1, we obtained internal temperature at 10-s intervals via an ingestible pill telemetry system (CorTemp, HQ Incorporated, Palmetto, FL) ingested at least 2 h before the experiment.

We monitored beat-by-beat arterial blood pressure via index finger photoplethysmography on the nonexperimental (right) arm (Finometer Pro, FMS, Amsterdam, NLD). We calculated cardiac output via ModelFlow analysis of the arterial waveform (BeatScope, FMS); we acknowledge that ModelFlow assumptions are less valid during whole body heat stress (21) but since these data are supportive, they were retained only to verify that heat stress caused standard changes in the cardiovascular system (22). We measured heart rate via standard limb lead electrocardiogram (ECG100C, BioPac Systems, Goleta, CA). Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was also measured via upper arm cuff and Dinamap algorithm (Carescape V100, GE Healthcare).

We measured the following recorded variables for dorsal forearm and shin skin (protocol 1) or forearm skin only (protocol 2): skin blood flux (SkBF), eccrine sweat rate, and skin temperature. We measured SkBF via laser-Doppler flowmetry integrative probes (LabFlow, Moor Instruments, Devon, GBR). We indexed cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) by dividing laser-Doppler flux by MAP and expressed it as a percentage of the preperturbation value (before mechanical perturbation). We also reported SkBF because some of the perturbations caused experimental manipulation of arterial pressure at the measurement site (see results). In addition to the presentation of absolute data, we expressed SkBF, CVC, and sweat rate as a percentage change from the preperturbation value. Although this method of reporting is less standard, we believe it may be more appropriate because of the site-specific repeated measures design of the study, because we did not standardize to maximal SkBF (see Limitations), and because one perturbation altered MAP (see results). In addition, we support this reporting since we robustly tested responses at many different levels of sweat induction. We defined the preperturbation value as 100% of the normothermic, preheating value for protocol 1, and 100% of the prepilocarpine value for protocol 2.

We measured all parameters during baseline, preperturbation, mechanical perturbation, and postperturbation (recovery) periods.

Data Analysis

Data were collected at 62.5 Hz via a data acquisition system and software (MP 150 & Acqknowledge 4.4, BioPac Systems). We analyzed measurements in 1-min increments before the perturbation and during the last minute of the perturbation. We used two-way repeated measures ANOVA to analyze whether differences existed between conditions (perturbation vs. control period) and across timepoints (normothermia, midpoint of heat stress, and final heat stress) for each perturbation (CVAR, CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure, and ischemia) in protocol 1 and whether differences existed between conditions and across cholinergic agonist conditions (vehicle control, ED50, and EMAX) for each perturbation in protocol 2. To assess intestinal temperature for protocol 1, we used one-way repeated measures ANOVA to analyze whether differences existed across timepoints and to assess skin temperatures for protocol 1, we used two-way repeated measures ANOVA to analyze whether differences existed between conditions (covered vs. uncovered) and across timepoints. We conducted Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc analyses when significant main effects were observed in the above analyses. All values are reported as means ± SE unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS

Protocol 1: Physiological Sweat Induction

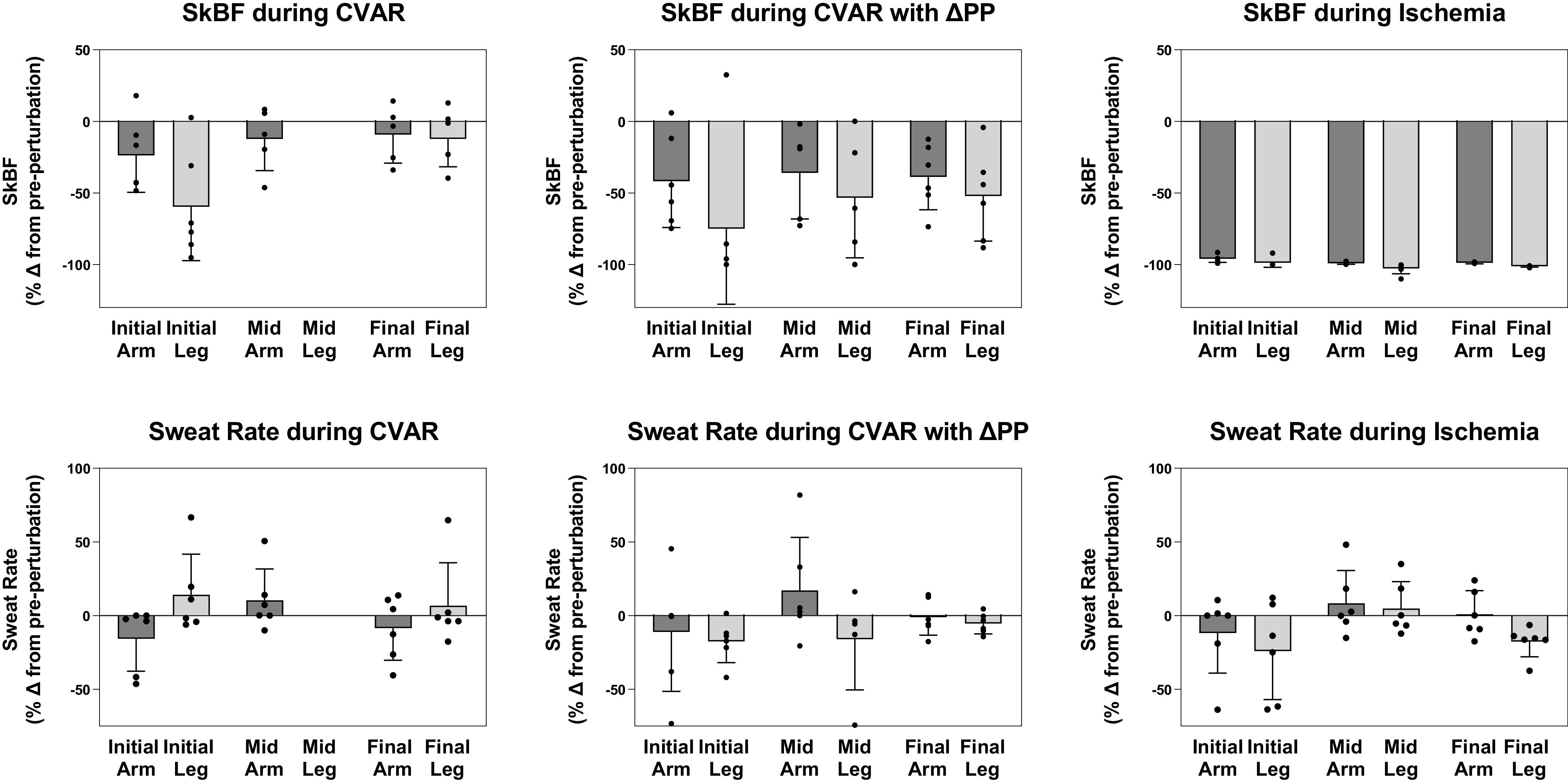

Covered and uncovered skin temperatures were within normal ranges during normothermia with covered being slightly higher than uncovered (Table 1). For each perturbation (CVAR, CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure, and ischemia), we observed main effects of perturbation on the change in arm and leg CVC (all P < 0.035). During normothermia, forearm and shin CVC decreased during CVAR (24 ± 1 and 59 ± 16%), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (42 ± 13 and 75 ± 22%), and ischemia (96 ± 1 and 99 ± 1% for the arm and leg, respectively) compared with a control period immediately before the perturbation (see Fig. 2 for SkBF data). Despite these decreases in CVC, there were no significant effects on transepithelial water loss (Fig. 2). At the midpoint of heat stress, forearm and shin CVC decreased during CVAR (forearm 21 ± 7%; no data for shin due to technical issues), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (37 ± 14 and 55 ± 18%), and ischemia (99 ± 1 and 100 ± 1% for the arm and leg, respectively) compared with a control period immediately before the perturbation (see Fig. 2 for SkBF data). Despite these decreases in CVC, eccrine sweat rate was not significantly affected (Fig. 2). Heat stress increased internal temperature, heart rate, covered and uncovered limb skin temperatures (Table 1), forearm CVC, and forearm sweat rate (Table 2). At the end point of heat stress, forearm and shin CVC also decreased during CVAR (20 ± 8 and 14 ± 8%), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (39 ± 10 and 52 ± 13%), and ischemia (99 ± 1 and 100 ± 1% for the arm and leg, respectively) compared with a control period immediately before the perturbation (see Fig. 2 for SkBF data). Despite the decreases in CVC during each perturbation, change in eccrine sweat rate was not significantly altered across heat stress timepoints (all P > 0.16; Fig. 2). Table 2 provides absolute values for skin blood flux, CVC, sweat rate, and hemodynamic data.

Table 1.

Thermal values during normothermia and heat stress

| Normothermic Baseline | Mid Heat Stress | End Heat Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal temperature (°C) | 37.1 ± 0.1 (36.8–37.3) | 37.6 ± 0.1* (37.4–37.9) | 38.0 ± 0.1* (37.7–38.2) |

| Skin temperature (°C) – limb (covered) | 32.2 ± 0.2^ (30.5–34.5) | 36.7 ± 0.3*^ (35.5–38.3) | 36.8 ± 0.3*^ (35.3–38.6) |

| Skin temperature (°C) – limb (uncovered) | 30.0 ± 0.3 (27.9–31.9) | 31.8 ± 0.6* (28.0–35.6) | 32.1 ± 0.7* (26.5–35.4) |

Values are means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 compared with normothermia. ^P < 0.05 compared with uncovered.

Figure 2.

Skin blood flux (SkBF) and sweat rate of arm and leg after acute mechanical perturbations during whole body heat stress. Top row: SkBF measured via laser-Doppler during normothermia [perfusion of tube-lined suit with thermoneutral water (34°C); Initial], midpoint of heat stress (Mid), and end of heat stress [perfusion of tube-lined suit with hot water (46°C–50°C); Final] after cutaneous venoarteriolar response (CVAR), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (CVAR with ΔPP), and ischemia. Bottom row: Transepithelial water loss or sweat rate measured via capacitance hygrometry during normothermia (Initial), midpoint of heat stress (Mid), and end (Final) of heat stress after CVAR, CVAR with ΔPP, and ischemia. SkBF and sweat rate are expressed as a percent change from a control period immediately before engagement of the mechanical perturbation. Due to technical issues with one parameter and timepoint, CVAR leg data are not included for the Mid heat stress timepoint. Values are expressed as means ± SE for six healthy volunteers.

Table 2.

Forearm and leg skin blood flow, cutaneous vascular conductance, sweat rate and mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate during Protocol 1

| Normothermia |

Mid Heat Stress |

End Heat Stress |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVAR |

CVAR + ΔPP |

Ischemia |

CVAR |

CVAR + ΔPP |

Ischemia |

CVAR |

CVAR + ΔPP |

Ischemia |

||||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| FA SkBF, au | 45 ± 11 | 36 ± 11 | 43 ± 9 | 28 ± 11 | 44 ± 12 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 237 ± 54 | 214 ± 72 | 177 ± 47 | 144 ± 66 | 256 ± 52 | 2 ± 0.5 | 292 ± 38 | 255 ± 38 | 288 ± 40 | 193 ± 46 | 259 ± 24 | 3 ± 0.6 |

| FA CVC, au/mmHg | 52 ± 12 | 43 ± 13 | 50 ± 10 | 32 ± 13 | 47 ± 11 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 330 ± 67 | 265 ± 72 | 238 ± 59 | 186 ± 78 | 333 ± 57 | 3 ± 0.5 | 473 ± 85 | 392 ± 84 | 428 ± 51 | 282 ± 73 | 384 ± 91 | 4 ± 0.8 |

| FA SR, mL/cm2/min | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.06 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 1.05 ± 0.25 | 1.17 ± 0.28 | 0.77 ± 0.33 | 0.76 ± 0.27 | 1.35 ± 0.33 | 1.40 ± 0.39 | 1.47 ± 0.33 | 1.46 ± 0.37 | 1.35 ± 0.28 | 1.34 ± 0.31 | 1.34 ± 0.33 | 1.40 ± 0.38 |

| Leg SkBF, au | 24 ± 9 | 14 ± 8 | 30 ± 12 | 9 ± 6 | 23 ± 11 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 165 ± 72 | 146 ± 73 | 258 ± 90 | 0 ± 0 | 281 ± 74 | 243 ± 58 | 274 ± 76 | 177 ± 84 | 226 ± 39 | 0 ± 0 | ||

| Leg CVC, au/mmHg | 26 ± 9 | 15 ± 8 | 33 ± 13 | 9 ± 7 | 24 ± 11 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 222 ± 91 | 182 ± 89 | 323 ± 98 | 0 ± 0 | 376 ± 83 | 320 ± 66 | 404 ± 108 | 259 ± 126 | 324 ± 70 | 0 ± 0 | ||

| Leg SR, mL/cm2/min | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 1.38 ± 0.74 | 0.96 ± 0.47 | 1.27 ± 0.48 | 1.26 ± 0.44 | 1.16 ± 0.37 | 1.13 ± 0.36 | 1.34 ± 0.44 | 1.27 ± 0.43 | 1.36 ± 0.47 | 1.04 ± 0.30 | ||

| MAP, mmHg | 84 ± 5 | 84 ± 4 | 85 ± 3 | 85 ± 2 | 89 ± 3 | 95 ± 6 | 74 ± 4 | 82 ± 4 | 80 ± 4 | 79 ± 2 | 79 ± 4 | 88 ± 4 | 78 ± 6 | 82 ± 4 | 77 ± 3 | 79 ± 4 | 89 ± 4 | 92 ± 5 |

| HR, beats/min | 66 ± 12 | 62 ± 13 | 66 ± 13 | 65 ± 10 | 66 ± 11 | 66 ± 12 | 96 ± 9 | 96 ± 11 | 88 ± 8 | 95 ± 11 | 94 ± 10 | 96 ± 10 | 95 ± 12 | 97 ± 12 | 99 ± 10 | 98 ± 13 | 96 ± 15 | 96 ± 16 |

MAP and HR are included for the arm portion of the protocol. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). Due to technical issues with one parameter and timepoint, CVAR leg data are not included for the Mid heat stress timepoint. CVC, cutaneous vascular conductance; FA, forearm; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; SkBF, skin blood flux; SR, sweat rate.

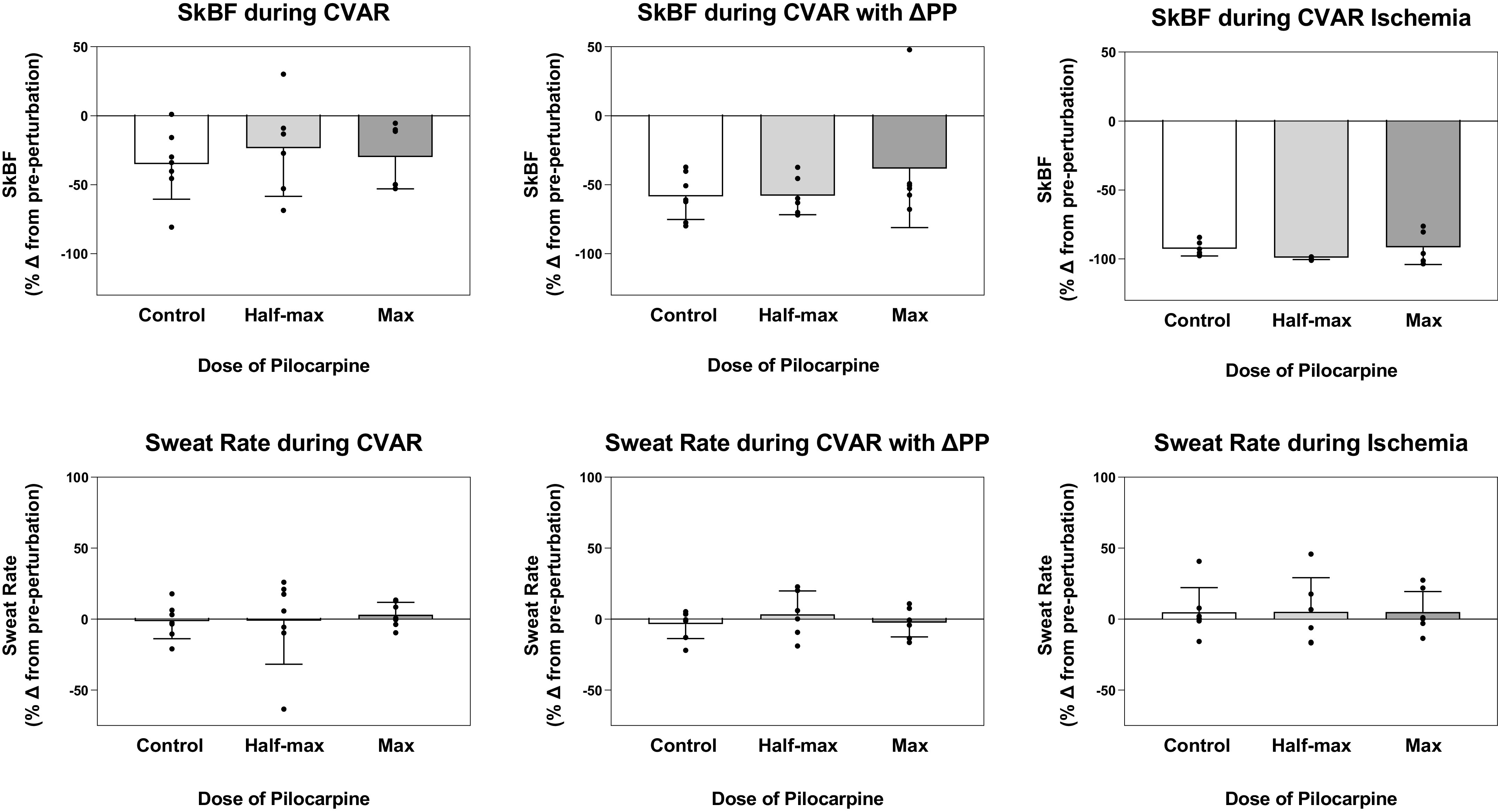

Protocol 2: Pharmacological Sweat Induction with Acute SkBF Reduction

Cholinergic agonist infusions increased SkBF (87 ± 18 and 57 ± 16 units) and sweating (0.37 ± 0.20 and 0.64 ± 0.15 mg/mL/min, for pilocarpine ED50 and EMAX, respectively). With the vehicle control, SkBF increased (8 ± 4 units) but there was no alteration in transepithelial water loss (−0.02 ± 0.09 mg/mL/min). For each perturbation (CVAR, CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure, and ischemia), we observed main effects of perturbation on the change in CVC (all P < 0.01). With the vehicle control, CVC decreased during CVAR (38 ± 9%), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (61 ± 8%), and ischemia (93 ± 2%) compared with a control period immediately before the perturbation (see Fig. 3 for SkBF data). Despite these decreases in CVC, there were no significant effects on transepithelial water loss (Fig. 3). At pilocarpine ED50, CVC decreased during CVAR (26 ± 14%), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (62 ± 7%), and ischemia (99 ± 1%) compared with a control period immediately before the perturbation (see Fig. 3 for SkBF data). Despite these decreases in CVC, eccrine sweat rate was not significantly affected (Fig. 3). At pilocarpine EMAX, CVC also decreased during CVAR (33 ± 9%), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (42 ± 20%), and ischemia (92 ± 5%) compared with a control period immediately before the perturbation (see Fig. 3 for SkBF data). Despite the decreases in CVC during each perturbation, change in eccrine sweat rate was not significantly altered across pilocarpine concentrations (all P > 0.22; Fig. 3). Local skin temperatures (28.4 ± 0.1°C) were unchanged during the duration of the experiment. Table 3 provides absolute values for skin blood flux, CVC, sweat rate, and hemodynamic data.

Figure 3.

Skin blood flux (SkBF) and sweat rate after mechanical perturbations during pilocarpine nitrate intradermal microdialysis infusion. Top row: SkBF measured via laser-Doppler during vehicle (lactated Ringer’s), pilocarpine ED50 (0.01 mg/mL) and EMAX (1.66 mg/mL) infusion and after cutaneous venoarteriolar response (CVAR), CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure (CVAR with ΔPP), and ischemia. Bottom row: Sweat rate measured via capacitance hygrometry during vehicle (lactated Ringer’s), pilocarpine ED50 (0.01 mg/mL) and EMAX (1.66 mg/mL) infusion and after CVAR, CVAR with ΔPP, and ischemia. SkBF and sweat rate are expressed as a percent change from a control period immediately before engagement of the mechanical perturbation. Values are expressed as means ± SE for seven healthy volunteers.

Table 3.

Forearm skin blood flow, cutaneous vascular conductance, sweat rate and mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate during Protocol 2

| Control |

Half-Max (ED50) |

Max |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVAR |

CVAR + ΔPP |

Ischemia |

CVAR |

CVAR + ΔPP |

Ischemia |

CVAR |

CVAR + ΔPP |

Ischemia |

||||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| SkBF, au | 27 ± 6 | 21 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | 11 ± 3 | 26 ± 6 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 80 ± 11 | 68 ± 22 | 97 ± 28 | 43 ± 16 | 78 ± 20 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 77 ± 30 | 58 ± 28 | 82 ± 33 | 40 ± 16 | 62 ± 33 | 2 ± 1.5 |

| CVC, au/mmHg | 30 ± 6 | 22 ± 6 | 30 ± 6 | 13 ± 5 | 28 ± 6 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 90 ± 22 | 79 ± 31 | 124 ± 40 | 59 ± 29 | 89 ± 28 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 77 ± 31 | 59 ± 29 | 104 ± 42 | 39 ± 14 | 68 ± 35 | 2 ± 1.6 |

| SR, mL/cm2/min | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.40 ± 0.20 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.50 ± 0.20 | 0.53 ± 0.23 | 0.60 ± 0.20 | 0.60 ± 0.17 | 0.63 ± 0.23 | 0.57 ± 0.20 | 0.60 ± 0.17 | 0.67 ± 0.23 |

| MAP, mmHg | 89 ± 7 | 93 ± 9 | 86 ± 7 | 91 ± 7 | 93 ± 7 | 96 ± 7 | ||||||||||||

| HR, beats/min | 68 ± 5 | 65 ± 4 | 67 ± 4 | 70 ± 4 | 68 ± 5 | 66 ± 5 | ||||||||||||

Values are means ± SE (n = 7). Because data were collected at the same timepoint, MAP and HR are the same for control, half-max, and max conditions. CVC, cutaneous vascular conductance; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; SkBF, skin blood flux; SR, sweat rate.

Protocol 2b: Pharmacological Sweat Induction with Extended SkBF Reduction

Similar to 3 min of CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure, 10 min of CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure did not appreciably alter forearm sweat rate. Because of the subject number in these control and verification experiments, we are describing but not analyzing these data. Consistent with data collected 50–85 yr ago (3–6), 10 min of arterial ischemia progressively decreased sweating. Again, this did not occur in 3 min of arterial ischemia.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we aimed to uncouple the sympathetic nervous system cutaneous end-organ responses by inducing eccrine sweating while decreasing associated SkBF. In partial support of our hypotheses: 1) during CVAR and CVAR with decreased perfusion pressure, SkBF was attenuated during both physiological and pharmacological sweat-inducing protocols, but this did not alter sweat rate; 2) during acute ischemia, SkBF was abated during both sweat-inducing protocols, but this did not proportionally decrease sweat rate. Prolonged ischemia, however, did reduce sweat rate, agreeing with previous findings (3–6). Taken together, these data could indicate a lack of thermoregulatory effector end-organ cross talk or independent control and regulation of cutaneous blood vessels and eccrine sweat glands during acute timeframes.

In this study, we included several additional experiments to strengthen our findings regarding the relationship between SkBF and sweating. First, physiological regulatory systems are often nonlinear and differentially controlled depending on the level of stimulus and/or rate of outflow. To account for this potential, we assessed sweating at multiple levels of direct cholinergic stimulation [previously identified ED50 and EMAX pilocarpine doses via intradermal microdialysis (17)] and indirect thermoregulatory reflex stimulation (increased internal temperature by 0.5 and then 1.0°C via passive heat stress). Our data interpretations were similar for all levels of pharmacologically and physiologically induced sweating, where acute SkBF modulation impacted neither moderate nor high levels of sweat secretion. Second, we tested CVAR in both the arm and leg because of the possibility of differences between upper and lower limb blood flow responses (15). Despite the potential for different amounts of sweating and changes between limbs in SkBF based on venoarteriolar and myogenic mechanisms, we did not observe an effect of acute changes of blood flow on sweat secretion rate. This also strengthens the findings because of increased generalizability, as peripheral sweating data are not confined to the forearm. Third, our data demonstrate a similar CVAR impact on sweat rate whether the reflex was engaged by itself or coupled with a decrease in perfusion pressure. Fourth, we performed repeatability experiments associated with CVAR reductions in blood flow. We did not observe differing effects and therefore do not believe that having serial reductions in SkBF independently affected subsequent CVAR responses. Combined, the results of these additional tests increase confidence in study findings and interpretations that acute decreases in SkBF do not modulate sweat rate.

Eccrine sweating and cutaneous vasodilation are both under systemic autonomic nervous system control and regulation. Heat stress increases sudomotor and vasomotor efferent nerve activity to the skin (23), increasing sweat secretion rate and SkBF. There are many methodological challenges in precisely identifying the origin of multiunit skin sympathetic nerve activity recordings (24); some transduction methods have been suggested (25), but these have not been widely adopted. Tracing the postganglionic sympathetic signal back to the central nervous system origin, sudomotor and vasomotor neurons appear to share some origins but are relayed through a series of separate pathways in the rodent brain (26, 27). Thus, differential control and regulation of these two thermoregulatory efferent pathways in humans has strong theoretical merit. For example, unloading baroreceptors decreases CVC but has limited effects on sudomotor neural outflow and sweating (28–33). Combined with the current data, this indicates that short-term alterations of SkBF do not compromise the potential for secretions and uninterrupted evaporative cooling. This ability to sustain evaporative cooling could have functional importance during conditions with changes in body or limb position or with blood flow restrictions.

A novel aspect of this study is our experimental avoidance of sympathetically induced noradrenergic vasoconstriction and direct adrenergic drug administration to alter SkBF. Instead, we used nonpharmacological approaches to alter vasomotor function and administered a cholinergic agonist via intradermal microdialysis to increase sudomotor function. Dual activation of adrenergic and cholinergic sweating receptors on sweat glands of both humans and other animals is well established (34–36). Although a minor agonist pathway in humans (37–39), β-adrenergic sweating may be more adaptable to increase in function with training (40, 41) and decrease in function with pathology (42, 43). We did not observe an alteration in sweating with mechanically induced decreases in SkBF, which indicates that the aforementioned studies utilizing norepinephrine or sympathetic noradrenergic mechanisms were likely not confounded by a multiple agonist effect on the sweat gland.

The lack of acute modulation of sweating with decreases in blood flow does not diminish the importance of SkBF in sweating or thermoregulation. SkBF has been identified as prerequisite for local sweat production (3, 44). This may be due to providing adequate interstitial fluid volume needed for fluid transport into the luminal spaces of the eccrine coil. In addition, there is strong evidence that ischemia leads to decreases and abatement of local sweating responses (3–6). We did not observe this effect with acute ischemia (3 min) but did during prolonged ischemia (10 min). Kuno (5) also observed gradual decreases (in minutes) in sweating with arterial occlusion in a small subset of individuals. We did not observe this phenomenon in our 3-min circulatory arrest conditions in either the arm or the leg but did with the longer, 10 min, timeframe. Thus, it appears that there is a time-course effect on the changes in sweating with reduced blood flow. Similar decreases in sweat rate are observed with ouabain administration in both isolated glands (45, 46) and in vivo (47, 48) as with nonacute ischemia. Thus, it is possible that the energy demand of these active exocrine glands causes a negative cellular ATP/ADP balance, which inhibits the Na+,K+-ATPase, leading to a decrease in secretion rate. This effect is not observed acutely but will result if blood flow is reduced for a prolonged time. Although it is also possible that ischemia caused changes in local signaling and increased metabolite production, these changes did not appear to cause compensatory changes in sweat rate.

Limitations

We selected various forms of mechanical perturbations to reduce and abate SkBF. It is possible that as the skin vasodilated, the role of the CVAR was in part diminished, and/or the standard cuff pressure used to engage the CVAR was not sufficient to overcome the increase in vascular volume associated with heat stress (22). This can occur with both local heating and vasodilator agonists (49) and during reflex vasodilation that occurs with whole body heat stress (50). Even if the vasoconstrictor stimulus was blunted, this is unlikely to have affected the interpretations, as the arterial occlusion data would have resulted in a greater decrease in SkBF and we are not directly comparing the responses across the heating or drug doses. Similarly, if cuff pressures were too low to cause venous occlusion in all subjects, the secondary perturbation of limb drop was able to cause decreases in skin blood flow in the arm and leg for all subjects. Thus, despite the possible cuff pressure limitation, the mean data and interpretations from both of these mechanical perturbations agree.

Summary and Implications

In summary, mechanically decreasing SkBF during eccrine sweat induction did not decrease sweat rate in an acute timeframe but did with a severely decreased SkBF in a longer timeframe. These data indicate that a short-term decrease in SkBF does not compromise sweating, but that a long-term decrease does. Utilizing a tight experimental approach, current data appear to corroborate previous systemic perturbation (9, 10) and adrenergic mechanism (7) interpretations indicating that sweat rate and SkBF can be uncoupled and not be acutely detrimental to thermoregulation. It is possible that acute alterations in SkBF failing to alter sweat rate and evaporative cooling could be an adaptive advantage. Upright posture and dependent limb positions occur frequently during heat and exercise-heat stresses; in these conditions a large percentage of the skin surface may be receiving reduced skin blood flow because of venoarteriolar and myogenic mechanisms. This preservation of evaporative cooling despite acute decreases in SkBF could have implications for heat storage and balance during changes in body posture, limb position, or blood flow restrictive conditions.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

Laboratory funding was provided by National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases Grant AR069912 (to T.E.W. and K.M.-W.). Additional personnel support was provided by the D.O. Research Fellowship Program from Marian University College of Osteopathic Medicine (to M.M.F., K.A., and J.W.D.) and by the Federal Work-Study program (to O.G.M.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.M.-W. and T.E.W. conceived and designed research; K.A., M.M.F., J.W.D., S.C.N., and T.E.W. performed experiments; K.M.-W., M.M.F., K.A., J.W.D., S.C.N., R.P.D., O.G.M., and T.E.W. analyzed data; K.M.-W., M.M.F., R.P.D., and T.E.W. interpreted results of experiments; K.M.-W., O.G.M., and T.E.W. prepared figures; K.M.-W., M.M.F., and T.E.W. drafted manuscript; K.M.-W., M.M.F., K.A., J.W.D., S.C.N., R.P.D., O.G.M., and T.E.W. edited and revised manuscript; K.M.-W., M.M.F., K.A., J.W.D., S.C.N., R.P.D., O.G.M., and T.E.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Hill-Rom Simulation Center and staff and the subjects for their willing participation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brengelmann GL, Freund PR, Rowell LB, Olerud JE, Kraning KK. Absence of active cutaneous vasodilation associated with congenital absence of sweat glands in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 240: H571–H575, 1981. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.4.H571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kellogg DL Jr, Pérgola PE, Piest KL, Kosiba WA, Crandall CG, Grossmann M, Johnson JM. Cutaneous active vasodilation in humans is mediated by cholinergic nerve cotransmission. Circ Res 77: 1222–1228, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collins KJ, Sargent F, Weiner JS. The effect of arterial occlusion on sweat-gland responses in the human forearm. J Physiol 148: 615–624, 1959. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Randall WC, Deering R, Dougherty I. Reflex sweating and the inhibition of sweating by prolonged arterial occlusion. J Appl Physiol 1: 53–59, 1948. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1948.1.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuno Y. Human Persipration. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elizondo RS, Banerjee M, Bullard RW. Effect of local heating and arterial occlusion on sweat electrolyte content. J Appl Physiol 32: 1–6, 1972. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wingo JE, Low DA, Keller DM, Brothers RM, Shibasaki M, Crandall CG. Skin blood flow and local temperature independently modify sweat rate during passive heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109: 1301–1306, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00646.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shamsuddin AK, Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Iontophoretic beta-adrenergic stimulation of human sweat glands: possible assay for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activity in vivo. Exp Physiol 93: 969–981, 2008. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ravanelli N, Jay O, Gagnon D. Sustained increases in skin blood flow are not a prerequisite to initiate sweating during passive heat exposure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 313: R140–R148, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00033.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cramer MN, Gagnon D, Crandall CG, Jay O. Does attenuated skin blood flow lower sweat rate and the critical environmental limit for heat balance during severe heat exposure? Exp Physiol 102: 202–213, 2017. doi: 10.1113/EP085915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rowell LB. Human Cardiovascular Control. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henriksen O. Local sympathetic reflex mechanism in regulation of blood flow in human subcutaneous adipose tissue. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 450: 1–48, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henriksen O, Sejrsen P. Local reflex in microcirculation in human skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand 99: 19–26, 1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crandall CG, Shibasaki M, Yen TC. Evidence that the human cutaneous venoarteriolar response is not mediated by adrenergic mechanisms. J Physiol 538: 599–605, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snyder KA, Shamimi-Noori S, Wilson TE, Monahan KD. Age- and limb-related differences in the vasoconstrictor response to limb dependency are not mediated by a sympathetic mechanism in humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 205: 372–380, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2012.02416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okazaki K, Fu Q, Martini ER, Shook R, Conner C, Zhang R, Crandall CG, Levine BD. Vasoconstriction during venous congestion: effects of venoarteriolar response, myogenic reflexes, and hemodynamics of changing perfusion pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1354–R1359, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00804.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morgan CJ, Friedmann PS, Church MK, Clough GF. Cutaneous microdialysis as a novel means of continuously stimulating eccrine sweat glands in vivo. J Invest Dermatol 126: 1220–1225, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39: 175–191, 2007. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anderson C, Andersson T, Andersson RG. In vivo microdialysis estimation of histamine in human skin. Skin Pharmacol 5: 177–183, 1992. doi: 10.1159/000211035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramanathan NL. A new weighting system for mean surface temperature of the human body. J Appl Physiol 19: 531–533, 1964. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shibasaki M, Wilson TE, Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Seifert T, Secher NH, Crandall CG. Modelflow underestimates cardiac output in heat-stressed individuals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R486–R491, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00505.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crandall CG, Wilson TE. Human cardiovascular responses to passive heat stress. Compr Physiol 5: 17–43, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cui J, Sathishkumar M, Wilson TE, Shibasaki M, Davis SL, Crandall CG. Spectral characteristics of skin sympathetic nerve activity in heat-stressed humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1601–H1609, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00025.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Macefield VG. Recording and quantifying sympathetic outflow to muscle and skin in humans: methods, caveats and challenges. Clin Auton Res 31: 59–75, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10286-020-00700-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sugenoya J, Iwase S, Mano T, Ogawa T. Identification of sudomotor activity in cutaneous sympathetic nerves using sweat expulsion as the effector response. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 61: 302–308, 1990. doi: 10.1007/BF00357617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Central nervous system circuits that control body temperature. Neurosci Lett 696: 225–232, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McAllen RM, Tanaka M, Ootsuka Y, McKinley MJ. Multiple thermoregulatory effectors with independent central controls. Eur J Appl Physiol 109: 27–33, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paull G, Dervis S, McGinn R, Haqani B, Flouris AD, Kondo N, Kenny GP. Muscle metaboreceptors modulate postexercise sweating, but not cutaneous blood flow, independent of baroreceptor loading status. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R1415–R1424, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00287.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schlader ZJ, Gagnon D, Lucas RA, Pearson J, Crandall CG. Baroreceptor unloading does not limit forearm sweat rate during severe passive heat stress. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 449–454, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00800.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cui J, Wilson TE, Crandall CG. Orthostatic challenge does not alter skin sympathetic nerve activity in heat-stressed humans. Auton Neurosci 116: 54–61, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wilson TE, Cui J, Crandall CG. Absence of arterial baroreflex modulation of skin sympathetic activity and sweat rate during whole-body heating in humans. J Physiol 536: 615–623, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0615c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilson TE, Cui J, Crandall CG. Mean body temperature does not modulate eccrine sweat rate during upright tilt. J Appl Physiol 98: 1207–1212, 2005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00648.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lynn AG, Gagnon D, Binder K, Boushel RC, Kenny GP. Divergent roles of plasma osmolality and the baroreflex on sweating and skin blood flow. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R634–R642, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00411.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cui CY, Schlessinger D. Eccrine sweat gland development and sweat secretion. Exp Dermatol 24: 644–650, 2015. doi: 10.1111/exd.12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quinton PM. Cystic fibrosis: lessons from the sweat gland. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 212–225, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robertshaw D. Neuroendocrine control of sweat glands. J Invest Dermatol 69: 121–129, 1977. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12497922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buono MJ, Tabor B, White A. Localized β-adrenergic receptor blockade does not affect sweating during exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R1148–R1151, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00228.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buono MJ, Gonzalez G, Guest S, Hare A, Numan T, Tabor B, White A. The role of in vivo beta-adrenergic stimulation on sweat production during exercise. Auton Neurosci 155: 91–93, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sawka MN, Wenger CB. Physiological responses to acute exercise-heat stress. In: Human Performance Physiology and Environmental Medicine at Terrestrial Extremes, edited by Pandolf KB, Sawka MN, Gonzalez RR.. Carmel, IN: Cooper Publishing Group, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Amano T, Shitara Y, Fujii N, Inoue Y, Kondo N. Evidence for β-adrenergic modulation of sweating during incremental exercise in habitually trained males. J Appl Physiol (1985) 123: 182–189, 2017. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00220.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Amano T, Fujii N, Kenny GP, Nishiyasu T, Inoue Y, Kondo N. The relative contribution of α- and β-adrenergic sweating during heat exposure and the influence of sex and training status. Exp Dermatol 29: 1216–1224, 2020. doi: 10.1111/exd.14208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Behm JK, Hagiwara G, Lewiston NJ, Quinton PM, Wine JJ. Hyposecretion of beta-adrenergically induced sweating in cystic fibrosis heterozygotes. Pediatr Res 22: 271–276, 1987. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salinas DB, Kang L, Azen C, Quinton P. Low beta-adrenergic sweat responses in cystic fibrosis and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-related metabolic syndrome children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol 30: 2–6, 2017. doi: 10.1089/ped.2016.0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith CJ, Kenney WL, Alexander LM. Regional relation between skin blood flow and sweating to passive heating and local administration of acetylcholine in young, healthy humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R566–R573, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00514.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Quinton PM. Effects of some ion transport inhibitors on secretion and reabsorption in intact and perfused single human sweat glands. Pflugers Arch 391: 309–313, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF00581513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sato K. Sweat induction from an isolated eccrine sweat gland. Am J Physiol 225: 1147–1152, 1973. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.5.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Louie JC, Fujii N, Meade RD, Kenny GP. The roles of the Na+/K+-ATPase, NKCC, and K+ channels in regulating local sweating and cutaneous blood flow during exercise in humans in vivo. Physiol Rep 4: e13024, 2016. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Louie JC, Fujii N, Meade RD, Kenny GP. The interactive contributions of Na(+)/K(+) -ATPase and nitric oxide synthase to sweating and cutaneous vasodilatation during exercise in the heat. J Physiol 594: 3453–3462, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Davison JL, Short DS, Wilson TE. Effect of local heating and vasodilation on the cutaneous venoarteriolar response. Clin Auton Res 14: 385–390, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s10286-004-0223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brothers RM, Wingo JE, Hubing KA, Del Coso J, Crandall CG. Effect of whole body heat stress on peripheral vasoconstriction during leg dependency. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 1704–1709, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00711.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.