Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer survivors experience a multitude of late treatment effects, resulting in greater unmet needs, elevated symptom burden, and reduced quality of life. Survivors can engage in appropriate self-management strategies post-treatment to help reduce the symptom burden. The objectives of this study were to: 1) survey the unmet needs of prostate cancer survivors using the validated Cancer Survivor Unmet Needs instrument; 2) explore predictors of high unmet needs; and 3) investigate prostate cancer survivors’ willingness to engage in self-management behaviors.

METHODS

Survivors were recruited from a prostate clinic and a cross-sectional survey design was employed. Inclusion criteria was having completed treatment two years prior. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. Univariate and multivariate analyses were done to determine predictors of unmet needs and readiness to engage.

RESULTS

A total of 206 survivors participated in the study, with a mean age of 71 years. Most participants were university/college-educated (n=123, 61%) and had an annual household income of ≥$99 999 (n=74, 38%). Participants reported erectile dysfunction (81%) and nocturia (81%) as the most frequently experienced symptoms with the greatest symptom severity χ̄=5.8 and χ̄=4.5, respectively). More accessible parking was the greatest unmet need in the quality-of-life domain (n=34/57, 60%). Overall, supportive care unmet needs were predicted by symptom severity on both univariate (p<0.001) and multivariate analyses (odds ratio [OR ] 1.81, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.92–1.00, p<0.001). Readiness to engage in self-management was predicted by an income of <$49 000 (OR 3.99, 95% CI 1.71–9.35, p=0.0014).

CONCLUSIONS

Income was the most significant predictor of readiness to engage in self-management. Consideration should be made to establishing no-cost and no-barrier education programs to educate survivors about how to engage in symptom self-management.

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers and approximately one in eight Canadian males is expected to develop the disease in their lifetime.1 In Canada, most prostate cancers are diagnosed at an early stage and the net five-year survival is approximately 93%.2 Recent diagnostic and therapeutic advancements in prostate cancer have enabled patients diagnosed with the disease to transition into post-treatment survivorship, resulting in a greater number of survivors; however, late post-treatment effects may lead to greater symptom burden,3,4 which translates to impacts on patients’ overall well-being, 5 quality of life,6 and greater costs to the healthcare system.7 As such, it is imperative that appropriate followup care and continued long-term support are provided as part of post-treatment prostate cancer management.

With limited capacity for survivorship care and a dearth of expertise in primary care, the opportunity to equip survivors in self-management warrants exploration. Cancer self-management is defined as, “What a person does, in collaboration with their healthcare team, to manage the symptoms, medical regimens, treatment side effects, physical changes, psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes following a cancer diagnosis and/or treatment.”8 Enabling prostate cancer survivors to become more involved in self-managing their symptoms can provide several benefits since patients are best able to identify and monitor their experience with symptom burden if appropriate training/preparation was available to them.9–11

Currently, few self-management strategies are routinely incorporated into the delivery of cancer care, including the survivorship phase of care.12 In addition, even when self-management supports are available, personal efforts to engage in survivorship care can be impeded by socio-economic factors, including the costs associated with accessing support programs (i.e., parking and time off work), location (i.e., rural areas that are geographically distant from supports),13 and lower socioeconomic status.14 If an appropriate and accessible level of support was provided, survivors could effectively reduce symptom burden on their own.9

While several guidelines have been developed to support healthcare providers in better caring for prostate cancer survivors, less guidance exists to equip prostate cancer survivors to self-manage. Many clinical studies have demonstrated the value of patient engagement with healthcare providers in terms of safer care and better health outcomes.15 Engaging patients and repositioning their role from passive recipients to active contributors can equip them to have clear expectations of care and the knowledge of who to approach for help.8,16

The objectives of this study were to: 1) survey the unmet needs of prostate cancer survivors; 2) explore the predictors of high unmet needs; and 3) investigate predictors of prostate cancer survivors’ self-management behaviors.

METHODS

This study employed a mixed-methods, cross-sectional design, and study approval was granted by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (UHN REB # 16-5831). Prostate cancer survivors receiving followup care at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre between May and November of 2017 were invited to complete a 20–30-minute, one-time, self-administered questionnaire. Inclusion criteria were: 18 years of age or older, able to read and write in English, and completed prostate cancer treatment two years prior. Depending on their preference, participants were given the option of completing a paper survey in clinic or an electronic survey. Completion of the questionnaire implied consent and participation was voluntary. Participant identification numbers were used to protect respondent identity.

Questionnaire

A survey package was developed to identify factors that could promote self-management among prostate cancer survivors. The survey also collected information on survivors’ supportive care needs, level of interest and ability in self-managing their survivorship care, and potential strategies to improve survivorship care. The survey package included a combination of validated measures and in-house developed measures. The in-house developed measures included a multi-item survey to ascertain survivor readiness to engage in survivorship care and a measure of survivor information needs and preferences. The surveys were developed using an iterative process, with several subject matter experts engaged, and were tested for face validity with survivors. Both in-house developed surveys underwent several rounds of revision before being finalized. The survey package consisted of five main sections, as described below.

Participant characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics

This section collected demographic variables, including age, education level, work-related activity, annual household income, marital status, and race. Additionally, participants were asked about the type of treatment they received and years since completing their treatment. To determine the types of symptoms experienced, participants were asked: 1) if they experienced the symptom; 2) to indicate the level of severity of the symptom using a 10-point scale with 0 being none and 10 being very severe; and 3) if they would be able to learn how to manage the symptom on their own.

Health literacy and self-efficacy measures

The validated Cancer Health Literacy Test 6-item measure (CHLT-6) was used to measure participants’ levels of health literacy by asking several questions related to cancer topics, such as treatment and side effect management. This tool was adapted from the CHLT 30-item instrument (CHLT-30) but was designed to rapidly identify patients with low cancer-related health literacy.17 Participants with adequate health literacy received a CHLT-6 score >4, while participants with inadequate health literacy received a CHLT-6 score of ≤4. To measure participants’ self-efficacy, the validated Stanford Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-item scale was used.18,19 The scale encompasses several chronic disease domains, which include questions about role function, emotional functioning, symptom control, and communication with healthcare providers. Included self-efficacy measures assessed participants’ confidence in managing a number of symptoms using a 10-point scale.

Cancer survivors’ unmet needs

A modified version of the validated Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs (CaSUN) instrument was used to evaluate prostate cancer survivors’ unmet needs. The CaSUN consists of 35 items separated into four major domains: 1) nine items within the Information Needs & Medical Care Issues domain; 2) nine items within the Quality-of-Life domain; 3) 10 items within the Emotional & Relationship Issues domain; and 4) seven items within the Life Perspective Issues domain. Respondents were asked to select whether the “need was fully met,” “need was not fully met,” or “not applicable” (Appendix; available at cuaj.ca). An overall CaSUN score is calculated by summing mean scores from all four domains, with a larger score indicating greater needs.

Managing survivorship care

The readiness to engage in survivorship care measure included eight items (Appendix; available at cuaj.ca). All items were measured using a five-point Likert scale, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” A total score was calculated by summing all items, with a maximum score of 40, and a mean score of 24. A score >24 indicates greater readiness to engage, and a score ≤24 indicates less readiness to engage in self-management. Participants were also asked how helpful it would be to play a bigger role in their survivorship care using a five-point Likert scale from “not at all helpful” to “very helpful.”

Information needs and preferences

Participants were asked how they would prefer to receive information about four topics: 1) cancer-related drugs and side effects; 2) lifestyle changes; 3) how to manage symptoms from cancer treatment; and 4) ongoing surveillance for cancer recurrence. Participants were asked if they wanted information on the topic, did not want information on the topic, or if the topic was not applicable, and were given a list of modalities to select from to indicate their preferred learning mode (e.g., consultation with the doctor, video, pamphlets, telephone, websites, podcasts, and e-learning).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described using means, standard deviations, medians, and ranges. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Cronbach Alpha was done to measure reliability of the Readiness to Engage measure and had a value of 0.868. A Cronbach Alpha value >0.8 is considered to have good internal consistency. Univariate analyses were done to identify the factors associated with prostate cancer survivors’ unmet needs and readiness to engage in survivorship care. Marital status (coupled and uncoupled) and employment (not working and working) were categorized for univariate analyses. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to estimate adjusted odds based on variables that were found to be statistically significant from univariate analyses (p<0.05). For readiness to engage, data was only available on 186 participants and those were used throughout the univariate analyses. For multivariable logistic regression, 14 responses were missing and analyses were done for 172 cases. For CaSUN, data was available for all 206 patients, and those were used in univariate analysis. For multivariable regression analyses, 20 responses were missing and analyses were done for 186 cases. R Studio statistical software was used for analyses.

RESULTS

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 206 patients completed the survey. Demographic information is reported in Table 1. The mean reported age was 71, most respondents were Caucasian (n=152, 78%), and married (n=162, 82%). Greater than half of the respondents were retired (n=130, 64%) and were college- or university-educated (n=123, 61%), and most had an annual household income of >$99 000 (n=74, 38%). Most received radiation treatment for their prostate cancer (n=126, 61%), followed by surgery (n=113, 55%) and were last treated 4–10 years prior (n=96, 60%). Most respondents had adequate health literacy scores (n=160, 77%) and the mean reported self-efficacy score was 8.3 (standard deviation [SD ] 2.0). Further details are shown in Table 1. Mean symptom severity was 1.8 (SD 1.3) and symptoms most frequently reported were erectile dysfunction (81%) and nocturia (81%). The highest reported symptom severity was erectile dysfunction (χ̄=5.8) and anejaculation (χ̄=4.5). Further details are shown in Table 2

Table 1.

Prostate cancer survivors’ demographic & clinical characteristics

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) (n=203) | – | |

| Mean (SD) | 70.6 (7.5) | – |

| Median (range) | 72 (47, 89) | |

|

| ||

| Employment status (n=206) | ||

| Retired | 131 | 63.6% |

| Working | 68 | 33.0% |

| Unemployed | 3 | 1.5% |

| Receiving disability payment | 2 | 1.0% |

| Other | 2 | 1.0% |

|

| ||

| Education (n=201) | ||

| College/university to graduate school | 123 | 61.2 |

| High school to some college/university | 48 | 23.9 |

| Grade school to some high school | 30 | 14.9 |

|

| ||

| Marital status (n=198) | ||

| Married | 162 | 81.8 |

| Single | 11 | 5.6 |

| Divorced | 11 | 5.6 |

| Separated | 7 | 3.5 |

| Widowed | 6 | 3.0 |

| Other | 1 | 0.5 |

|

| ||

| Income (n=193) | ||

| More than $99 999 | 74 | 38.3 |

| $50 000–74 999 | 38 | 19.7 |

| $25 000–49 000 | 33 | 17.1 |

| $75 000–99 999 | 33 | 17.1 |

| Less than $25 000 | 15 | 7.8 |

|

| ||

| Race (n=195) | ||

| Caucasian/European | 152 | 77.9 |

| Black/African | 13 | 6.7 |

| East Asian | 7 | 3.6 |

| South Asian | 7 | 3.6 |

| Other | 5 | 2.6 |

| Arab/West Asian | 4 | 2.1 |

| Latin American | 4 | 2.1 |

| I prefer not to answer | 3 | 1.5 |

|

| ||

| Previous cancer treatment* (n=206) | ||

| Radiation | 125 | 60.7 |

| Surgery | 113 | 54.9 |

| Hormone | 34 | 16.5 |

| Chemotherapy | 4 | 1.9 |

| Other | 5 | 2.4 |

|

| ||

| Years since treatment (n=160) | ||

| 4–10 years | 96 | 60.0 |

| <4 years | 43 | 26.9 |

| >10 years | 21 | 13.1 |

|

| ||

| Health literacy (0–6) (n=206) | ||

| Inadequate health literacy (CHLT-6 <4) | 47 | 22.7 |

| Adequate health literacy (CHLT-6 >4) | 160 | 77.3 |

|

| ||

| Self-efficacy (n=190) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (1.95) | – |

| Median (min, max) | 8.8 (1.6–10.0) | – |

|

| ||

| Symptom severity score (n=188) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.3) | – |

| Median (min, max) | 1.6 (0–6.5) | – |

Respondents selected >1 response. CHLT: Cancer Health Literacy Test; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2.

Prostate cancer survivors’ symptom experience & severity

| Symptom | Survey responses, n | Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

Not sure n (%) |

Mean symptom severity (0–10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erectile dysfunction | 176 | 142 (80.7) | 25 (14.2) | 9 (5.1) | 5.8 |

| Nocturia | 180 | 145 (80.6) | 31 (17.2) | 4 (2.2) | 4.0 |

| Anejaculation | 171 | 114 (66.7) | 47 (27.5) | 10 (5.8) | 4.5 |

| Decreased libido | 180 | 118 (65.6) | 51 (28.3) | 11 (6.1) | 3.8 |

| Urinary urgency | 176 | 111 (63.1) | 57 (32.4) | 8 (4.5) | 3.5 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 184 | 95 (51.6) | 79 (42.9) | 10 (5.4) | 1.9 |

| Dribbling/persistent leakage of urine | 179 | 90 (50.3) | 81 (45.3) | 8 (4.5) | 2.2 |

| Fear of cancer recurrence | 186 | 89 (47.8) | 74 (39.8) | 23 (12.4) | 2.5 |

| Fatigue/decreased activity | 183 | 82 (44.8) | 74 (40.4) | 27 (14.8) | 2.0 |

| Rectal/fecal urgency | 185 | 74 (40.0) | 97 (52.4) | 14 (7.6) | 2.1 |

| Hot flushes | 181 | 37 (20.4) | 129 (71.3) | 15 (8.3) | 0.9 |

| Diarrhea | 182 | 65 (35.7) | 101 (55.5) | 16 (8.8) | 1.4 |

| Excessive gas | 182 | 63 (34.6) | 95 (52.2) | 24 (13.2) | 1.7 |

| Distress | 182 | 62 (34.1) | 96 (52.7) | 24 (13.2) | 1.5 |

| Irregular bowels | 185 | 53 (28.6) | 119 (64.3) | 13 (7.0) | 1.3 |

| Climacturia | 171 | 40 (23.4) | 107 (62.6) | 24 (14.0) | 1.2 |

| Cramps | 187 | 40 (21.4) | 126 (67.4) | 21 (11.2) | 1.0 |

| Decline in muscle mass | 185 | 38 (20.5) | 101 (54.6) | 46 (24.9) | 0.8 |

| Painful urination | 177 | 19 (10.7) | 152 (85.9) | 6 (3.4) | 0.6 |

| Urinary retention | 182 | 31 (17.0) | 140 (76.9) | 11 (6.0) | 0.8 |

| Anal sphincter dysfunction | 184 | 29 (15.8) | 143 (77.7) | 12 (6.5) | 0.6 |

| Financial problems | 175 | 26 (14.9) | 144 (82.3) | 5 (2.9) | 0.7 |

| Relationship problems | 179 | 20 (11.2) | 147 (82.1) | 12 (6.7) | 0.7 |

| Osteoporosis | 182 | 16 (8.8) | 119 (65.4) | 47 (25.8) | 0.4 |

| Challenges with body image | 177 | 12 (6.8) | 152 (85.9) | 13 (7.3) | 0.4 |

| Return to work problems | 169 | 11 (6.5) | 154 (91.1) | 4 (2.4) | 0.4 |

| Bone fracture | 180 | 8 (4.4) | 106 (58.9) | 29 (16.1) | 0.1 |

Met and unmet supportive care needs

The overall CaSUN unmet needs score was 11.2 (SD 10.6) of a possible 36. Overall, the proportion of participants reporting unmet needs was low; however, the top-reported unmet needs included more accessible hospital parking (n=34/57, 60%) and an ongoing case manager to whom patients can go to find out about services when they are needed (n=21/38, 55%). The majority of met needs were from the Information Needs & Medical Care Issues domain, with the top-reported item being to know that concerns about care were addressed well (n=133/142, 94%). Further details are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Prostate cancer survivors’ top-reported met and unmet needs, per domain

| Domain* | Mean (SD), range, median (IQR) | CaSUN item | “Need was fully met” n (%) | “Need was not fully met” n (%) | Not applicable n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Information needs and medical care issues | 5.1 (3.7), 0–18 | To know that concerns about my care are addressed well (n=187) | 133 (71%) | 9 (5%) | 45 (24%) |

| To feel like I am able to manage my health together with the medical team (n=188) | 133 (71%) | 6 (3%) | 49 (26%) | ||

| The very best medical care (n=187) | 119 (64%) | 7 (4%) | 61 (33%) | ||

| Information provided in a way that I can understand (n=186) | 114 (61%) | 4 (2%) | 68 (37%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Quality of life | 2.2 (2.9), 0–13 | Help to manage ongoing symptoms and side effects (n=182) | 55 (30%) | 16 (9%) | 111 (61%) |

| Help to adjust to changes in my quality of life as a result of cancer (n=187) | 56 (30%) | 14 (8%) | 117 (63%) | ||

| Help to reduce stress in my life (n=189) | 40 (21%) | 17 (9%) | 132 (70%) | ||

| More accessible hospital parking (n=184) | 23 (13%) | 34 (19%) | 127 (69%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Emotional & relationship issues | 2.8 (3.7), 0–18 | Help to manage my concerns about the cancer coming back (n=184) | 82 (45%) | 16 (9%) | 86 (47%) |

| To talk to others who have had cancer (n=183) | 39 (21%) | 4 (2%) | 140 (77%) | ||

| Help to address problems with my/our sex life (n=179) | 36 (20%) | 28 (16%) | 115 (64%) | ||

| An ongoing case manager to whom I can go to find out about services whenever they are needed (n=181) | 17 (9%) | 21 (12%) | 143 (79%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Life perspective | 1.2 (2.4), 0–12 | Help to try to make decisions about my life in the context of uncertainty (n=179) | 26 (15%) | 7 (4%) | 146 (82%) |

| How to deal with my own and/or others expectations of me as a “cancer survivor” (n=180) | 26 (14%) | 9 (5%) | 145 (81%) | ||

| Help to move on with my life (n=180) | 26 (14%) | 5 (3%) | 149 (83%) | ||

| Help to make my life count (n=169) | 22 (13%) | 3 (2%) | 144 (85%) | ||

Univariate analysis was conducted to explore whether unmet needs were associated with employment, education, income, marital status, years since treatment, treatment modality, age, and symptom severity. Univariate analysis revealed that greater unmet needs were associated with patients who were younger (p=0.046) and those who had greater symptom severity (p<0.001) (Table 4). Multivariate analysis revealed symptom severity (odds ratio [OR ] 1.81, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.92–1.00, p<0.001) to be the strongest predictor of unmet needs, with an 81% increase in the odds of having unmet needs per increase in symptom severity score, when adjusted for age.

Table 4.

Factors associated with prostate cancer survivors’ unmet needs

| Survey responses | Total sample (n=206) | Need met (n=102) | Unmet need (n=104) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Employment | 204 | 0.66 | |||

| Unemployed | 136 (67%) | 69 (68%) | 67 (65%) | ||

| Employed | 68 (33%) | 32 (32%) | 36 (35%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Education | 201 | 0.56 | |||

| College/university to graduate school | 123 (61%) | 57 (58%) | 66 (65%) | ||

| Grade school to some high school | 30 (15%) | 17 (17%) | 13 (13%) | ||

| High school to some college/ university | 48 (24%) | 25 (25%) | 23 (23%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Income | 193 | 0.16 | |||

| <$49 999 | 48 (25%) | 23 (24%) | 25 (26%) | ||

| $50 000–74 999 | 38 (20%) | 24 (25%) | 14 (14%) | ||

| $75 000–99 999 | 33 (17%) | 12 (13%) | 21 (21%) | ||

| >$99 999 | 74 (38%) | 36 (38%) | 38 (39%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Marital status | 198 | 0.27 | |||

| Coupled | 162 (82%) | 82 (85%) | 80 (78%) | ||

| Uncoupled | 36 (18%) | 14 (15%) | 22 (22%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Years since treatment | 160 | 0.1 | |||

| <4 | 43 (27%) | 13 (19%) | 30 (33%) | ||

| >10 | 21 (13%) | 11 (16%) | 10 (11%) | ||

| 4–10 | 96 (60%) | 46 (66%) | 50 (56%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Previous cancer treatment | 206 | ||||

| Radiation | 0.2 | ||||

| No | 81 (39%) | 45 (44%) | 36 (35%) | ||

| Yes | 125 (61%) | 57 (56%) | 68 (65%) | ||

| Surgery | 0.78 | ||||

| No | 93 (45%) | 45 (44%) | 48 (46%) | ||

| Yes | 113 (55%) | 57 (56%) | 56 (54%) | ||

| Hormone therapy | 0.85 | ||||

| No | 172 (83%) | 86 (84%) | 86 (83%) | ||

| Yes | 34 (17%) | 16 (16%) | 18 (17%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.62 | ||||

| No | 202 (98%) | 101 (99%) | 101 (97%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| Other | 1 | ||||

| No | 201 (98%) | 100 (98%) | 101 (97%) | ||

| Yes | 5 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Age | 0.046 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 203 | 70.6 (7.5) | 71.7 (7.6) | 69.6 (7.3) | |

| Median (min, max) | 72 (47, 89) | 73 (47, 89) | 71 (53, 83) | ||

|

| |||||

| Symptom severity | 188 | <0.001 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.3 (1) | 2.2 (1.4) | ||

| Median (min, max) | 1.6 (0, 6.5) | 1.2 (0, 4.5) | 2 (0, 6.5) | ||

SD: standard deviation.

Managing survivorship care

Readiness to engage in survivorship care

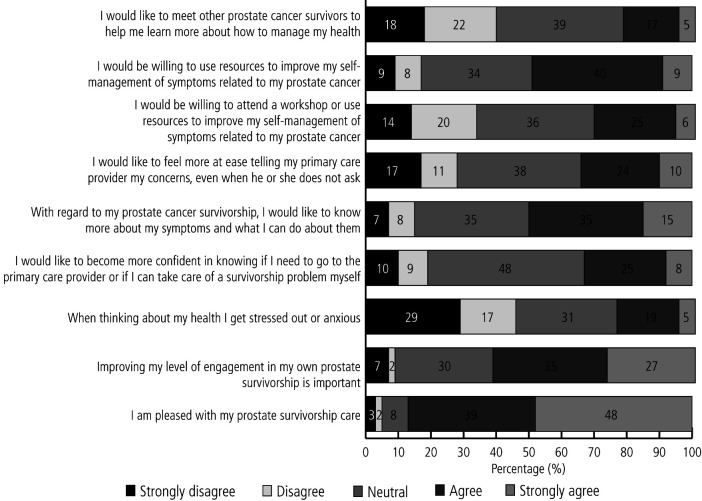

Most respondents agreed to strongly agreed that they were satisfied with their prostate cancer survivorship care (n=166/191, 87%) and half agreed to strongly agreed that they would like to know more about symptoms and what they can do about them (n=89/178, 50%) (Figure 1). Just under half of respondents said it would be helpful to very helpful to have a bigger role in managing their survivorship care (84/173, 49%). The mean readiness to engage score was 24.0 (SD 6.8, range 6–39). The majority of respondents felt that prostate cancer survivors could play a bigger role in managing their cancer-related health needs (n=111/147, 76%).

Figure 1.

Prostate cancer survivors’ readiness to engage in their survivorship care.

Univariate analysis revealed that greater readiness to engage in survivorship care was higher in survivors with an income of <$49 000 (p<0.001), uncoupled survivors (p=0.034), and survivors with greater symptom severity (p=0.018) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with prostate cancer survivors’ readiness to engage in their survivorship care

| Survey responses | Full sample (n=186) | Lack of readiness to engage (n=96) | Readiness to engage (n=90) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Employment | 185 | 0.54 | |||

| Not working | 121 (65%) | 60 (63%) | 61 (68%) | ||

| Working | 64 (35%) | 35 (37%) | 29 (32%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Education | 182 | 0.84 | |||

| College/university to graduate school | 116 (64%) | 61 (66%) | 55 (62%) | ||

| Grade school to some high school | 26 (14%) | 13 (14%) | 13 (15%) | ||

| High school to some college/ university | 40 (22%) | 19 (20%) | 21 (24%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Income | 177 | 0.0038 | |||

| >$99 999 | 68 (38%) | 44 (49%) | 24 (28%) | ||

| $50 000–74 999 | 34 (19%) | 17 (19%) | 17 (20%) | ||

| $75 000–99 999 | 31 (18%) | 16 (18%) | 15 (17%) | ||

| <$49 999 | 44 (25%) | 13 (14%) | 31 (36%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Marital status | 181 | 0.037 | |||

| Coupled | 147 (81%) | 82 (87%) | 65 (75%) | ||

| Uncoupled | 34 (19%) | 12 (13%) | 22 (25%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Years since treatment | 161 | 0.44 | |||

| <4 | 44 (27%) | 19 (23%) | 25 (32%) | ||

| >10 | 21 (13%) | 12 (14%) | 9 (12%) | ||

| 4–10 | 96 (60%) | 52 (63%) | 44 (56%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Radiation | 0.45 | ||||

| No | 72 (39%) | 40 (42%) | 32 (36%) | ||

| Yes | 114 (61%) | 56 (58%) | 58 (64%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Surgery | 1 | ||||

| No | 82 (44%) | 42 (44%) | 40 (44%) | ||

| Yes | 104 (56%) | 54 (56%) | 50 (56%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Hormone therapy | 0.7 | ||||

| No | 154 (83%) | 78 (81%) | 76 (84%) | ||

| Yes | 32 (17%) | 18 (19%) | 14 (16%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.62 | ||||

| No | 182 (98%) | 93 (97%) | 89 (99%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Other | 1 | ||||

| No | 181 (97%) | 93 (97%) | 88 (98%) | ||

| Yes | 5 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Age | 184 | 0.98 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 70.2 (7.4) | 70.2 (8) | 70.2 (6.7) | ||

| Median (min, max) | 72 (47,85) | 72 (47,85) | 71.5 (52,83) | ||

|

| |||||

| Symptom severity | 185 | 0.016 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Median (min, max) | 1.7 (0,6.5) | 1.2 (0,6.5) | 1.9 (0,5.5) | ||

SD: standard deviation.

On multivariate analysis, higher readiness to engage in survivorship care was predicted by an income of <$49 000 (OR 3.99, 95% CI 1.71–9.35, p=0.0014) and greater symptom severity (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.07–1.78, p=0.013).

Information needs & communication preferences

Most prostate cancer survivors indicated they wanted information about all four topics: drug side effects (n=139, 82%), lifestyle changes (n=138, 81%), treatment side effects (n=153, 89%), and ongoing cancer surveillance (n=163, 95%). When asked to indicate the preferred modality for receiving this information, most participants indicated that one-on-one consultation with their doctor/nurse was preferred across all topics, followed by websites and pamphlets (Table 6).

Table 6.

Preferred modality for receiving information about survivorship topics

| Preference and modality | Cancer drug-related side effects | Lifestyle changes | Managing treatment side effects | Ongoing surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total responses | 171 | 171 | 172 | 172 |

| Yes (n, %) | 139, 82% | 138, 81% | 153, 89% | 163, 95% |

| One-on-one with doctor/nurse | 112, 54% | 96, 47% | 129, 63% | 146, 71% |

| Websites | 56, 27% | 63, 31% | 54, 26% | 43, 21% |

| Pamphlets | 40, 19% | 39, 19% | 32, 16% | 16, 8% |

| e-learning | 27, 13% | 30, 15% | 26, 13% | 16, 8% |

| Video | 18, 9% | 20, 10% | 20, 10% | 9, 4% |

| Telephone | 12, 6% | 11, 5% | 12, 6% | 12, 6% |

| Podcasts | 6, 3% | 9, 4% | 4, 2% | 1, 1% |

| Other | 6, 3% | 6, 3% | 2, 1% | 4, 2% |

| No | 6 | 10 | 7 | 2 |

| Not applicable | 26 | 23 | 12 | 7 |

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the literature, as it furthers our understanding of issues faced by prostate cancer survivors several years after treatment. Unmet needs of participants were low overall, likely due to low symptom burden.20,21 The most common unmet need identified by participants was accessible hospital parking, which is reinforced in the literature,22 and has been endorsed by patients as a top health service need.23

We found that the strongest predictor of unmet needs in prostate cancer survivors was symptom severity. Erectile dysfunction was the most commonly reported symptom with the highest symptom severity score. This aligns with results by Watson et al, demonstrating that enduring symptoms are associated with greater unmet needs in prostate cancer survivors,21 and that >80% of prostate cancer survivors continue to report poor sexual function (e.g., erectile dysfunction) as a severe and persistent issue several months to years after treatment.21,22 Without appropriate education, there may be greater use of services to help address concerns about sexual function3 and greater out-of-pocket costs for survivors.24 Studies have shown that erectile dysfunction results in reduced quality of life,25 body image concerns,26 and elevated distress about partner satisfaction.27,28

Our findings regarding high symptom severity, unmet needs relating to supportive care, and willingness to engage in symptom self-management suggest that current self-management preparation/education of survivors may not be sufficient, and traditional biomedical interventions that have been developed to help address these issues have thus far been inadequate on their own.29 Recent research demonstrating the efficacy and utility of biopsychosocial interventions has shown promise, as they incorporate a “holistic” approach to therapy.29 In one study examining the effectiveness of a sexual rehabilitation intervention, prostate cancer survivors and partners received sexual health education from trained health professionals virtually over a 12-week period in order to build the skills, knowledge, and confidence required to manage their symptoms and concerns on their own.29 The intervention was found to be feasible, with the majority of participants completing the entire program and reporting high levels of satisfaction.30 These findings suggest that with appropriate education and support, survivors can be equipped to engage in self-management.

Self-management support largely depends on appropriate tailoring of survivorship care. Some survivors may require pharmacological management through prescription of oral medications to treat erectile dysfunction (for example, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors); some may need to engage in specific exercises, such as pelvic floor exercises or bladder retraining, to help alleviate nocturia; and some may require a combination of both strategies.21 Further, beginning these discussions closest to treatment is considered a “teachable moment,” as survivors are most receptive and willing to learn how to self-manage symptoms early on.31,32

Some evidence indicates that survivors may be more likely to discuss symptoms such as bowel and urinary issues at followup, as opposed to sexual changes, suggesting there may also be a lack of awareness or comfort discussing what some may perceive to be a sensitive topic.33 This may, in turn, lead to survivors neglecting their symptoms, leading to elevated symptom burden and lower quality of life.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that prostate cancer survivors in low-income groups are more ready to engage in their care than their higher-income counterparts; however, while this population of cancer survivors may be more willing to engage in self-management, they still may not do so due to an inability to access interventions because of temporal or geographical constraints. The literature reports that survivors in low-income groups are at heightened risk for not discussing followup care with their provider and often do not receive followup care as needed.34 Possible reasons for the lack of discussion about followup care may include fatalistic beliefs, being told that symptoms are normal, or perceiving their concerns to not be severe enough (e.g., emergency symptoms) to warrant professional help.35 Further, survivors in low-income groups have also been reported to be less likely to attend survivorship care programs that are offered in-person33 due to scheduling difficulties and temporal and financial restrictions, such as inability to take time off work, distance from the cancer centre,36 transportation, and having limited childcare options.37

Taken together, our results suggest that while survivors in lower-income groups may be willing to engage in self-management, lack of knowledge, awareness, and access to programs may prevent them from seeking appropriate followup care.38–40 The use of virtual self-management education programs may be a feasible solution, and training healthcare experts to offer online support and targeted resources may help improve access for this population of prostate cancer survivors.14,41 This issue also highlights the need to train healthcare providers to identify at-risk groups and to be proactive in discussing potential concerns with survivors such that referrals are made to appropriately tailored programs.

Our findings have important implications for the development of comprehensive self-management programs addressing acute and long-term treatment effects of prostate cancer survivors. The use of virtual interventions may be an ideal approach for delivering survivorship care due to their ability to standardize the delivery of information and promote greater reach.33,41 The literature indicates that survivors feel more comfortable discussing their symptoms over the phone or via a virtual platform42 and have been shown to be more likely to continue to use survivorship programs if there is an improvement in their symptoms.33 Further research is warranted to elucidate the specific role of survivors in engaging in their own survivorship care, such as access, cost, and format, as well as receptivity to virtual survivorship care plans.

Limitations

This study has some limitations, including the nature of the cross-sectional survey design and use of non-probability sampling, thus it may not be possible to generalize the study results. The participant population was better educated and less diverse than the local population. As discussed, most of the participants in this study had high levels of education. This could be a result of an English-language-only survey, and a non-response sample bias where the method of data collection unintentionally biased individuals with lower education attainment to decline participation in the study. Although we made efforts to mitigate this possibility by writing the study questions in plain language and using short measures where possible, participants were still required to complete a long survey package. It is also possible that voluntary surveys such as this will recruit those most well-adapted to managing life after cancer treatment in comparison with the general patient population, and future studies may need to use purposive sampling to better reach patients of different social strata.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostate cancer survivors continue to experience symptoms years after treatment, and symptom severity is the strongest predictor of unmet needs in this population. Survivors in low-income groups reported being more ready to engage in their survivorship care. Further research is needed to explore barriers and facilitators to survivors’ self-management and use of virtual survivorship self-management support.

KEY MESSAGES.

■ Erectile dysfunction and nocturia were the most frequently experienced symptoms by prostate cancer survivors, with the highest symptom severity.

■ Prostate cancer survivors’ unmet needs were predicted by symptom severity.

■ Prostate cancer survivors’ readiness to engage in self-management was predicted by an income of <$49 000.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Appendix available at cuaj.ca

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr. Catton has been an advisory board member for AbbVie, Bayer, Knight, and TerSera. Dr. Papadakos has received an education grant to develop educational videos for prostate cancer patients and caregivers from Astra Zeneca. The remaining authors do not report any competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

FUNDING: This work was supported by grant funding provided by the CARO-SANO FI Award, Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology, Ontario, Canada, and the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society Prostate cancer statistics. [Accessed December 14, 2021]. Available at: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/prostate/statistics.

- 2.Canadian Cancer Society Survival statistics for prostate cancer. [Accessed December 14, 2021]. Available at: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/prostate/prognosis-and-survival/survivalstatistics.

- 3.Skolarus TA, Wittmann D, Hawley ST. Enhancing prostate cancer survivorship care through self-management. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:564–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou ES, Bober SL, Nekhlyudov L, et al. Physical and emotional health information needs and preferences of long-term prostate cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:2049–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung WY, Aziz N, Noone AM, et al. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: A comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:343–54. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penson DF, Litwin MS. Quality of life after treatment for prostate cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2003;4:185–95. doi: 10.1007/s11934-003-0068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goonewardene SS, Persad R. In: Unmet needs and problems faced by prostate cancer survivors In prostate cancer survivorship. Goonewardene SS, Persad R, editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2018. pp. 177–178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Care Ontario. Self-management in cancer: Quality standards. Toronto, Canada: 2018. [Accessed September 30, 2022]. Available at: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/types-of-cancer/57371. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterson C, Jones M, Rattray J, et al. Identifying the self-management behaviors performed by prostate cancer survivors: A systematic review of the evidence. J Res Nurs. 2014;20:96–111. doi: 10.1177/1744987114523976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernat JK, Wittman DA, Hawley ST, et al. Symptom burden and information needs in prostate cancer survivors: A case for tailored long-term survivorship care. BJU Int. 2016;118:372–8. doi: 10.1111/bju.13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The individual and family self-management theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57:217–225e6. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ose D, Winkler EC, Berger S, et al. Complexity of care and strategies of self-management in patients with colorectal cancer. Patient Prefer Adher. 2017;11:731–42. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S127612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blusi M, Kristiansen L, Jong M. Exploring the influence of Internet-based caregiver support on experiences of isolation for older spouse caregivers in rural areas: A qualitative interview study. Int J Older People Nurs. 2015;10:211–20. doi: 10.1111/opn.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauvin J, Rispel L. Digital technology, population health, and health equity. J Public Health Policy. 2016;37:145–53. doi: 10.1057/s41271-016-0041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson AN, Brundage MD, Siemens R. Approach to primary care followup of patients with prostate cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:204–10. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18272636 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien R, Rose P, Campbell C, et al. “I wish I’d told them”: A qualitative study examining the unmet psychosexual needs of prostate cancer patients during followup after treatment”. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumenci L, Matsuyama R, Riddle DL, et al. Measurement of cancer health literacy and identification of patients with limited cancer health literacy. J Health Commun. 2014;19(Suppl 2):205–24. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.943377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, et al. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Self-Management Resource Center. Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-Item Scale. [Accessed September 30, 2022]. Available at: https://selfmanagementresource.com/wp-content/uploads/English_-_self-efficacy_for_managing_chronic_disease_6-item.pdf.

- 20.Gilbert SM, Dunn RL, Wittmann D, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction among prostate cancer patients followed in a dedicated survivorship clinic. Cancer. 2015;121:1484–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson E, Shinkins B, Frith E, et al. Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: implications for redesigning followup. BJU Int. 2016;117:E10–9. doi: 10.1111/bju.13122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazariego CG, Juraskova I, Campbell R, et al. Long-term unmet supportive care needs of prostate cancer survivors: 15-year followup from the NSW Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:5511–20. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall A, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. Top priorities for health service improvements among Australian oncology patients. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2021;12:83–95. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S291794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Oliveira C, Bremner KE, Ni A, et al. Patient time and out-of-pocket costs for long-term prostate cancer survivors in Ontario, Canada. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:9–20. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messaoudi R, Menard J, Ripert T, et al. Erectile dysfunction and sexual health after radical prostatectomy: Impact of sexual motivation. Int J Impot Res. 2011;23:81–6. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2011.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyde MK, Zajdlewicz L, Wootten AC, et al. Medical help-seeking for sexual concerns in prostate cancer survivors. Sex Med. 2016;4:e7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley SA, Foley SM, Wittmann D, et al. Sexual health concerns among cancer survivors: Testing a novel information-need measure among breast and prostate cancer patients. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:588–94. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuen W, Witherspoon L, Wu E, et al. Sexual rehabilitation recommendations for prostate cancer survivors and their partners from a biopsychosocial Prostate Cancer Supportive Care Program. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:1853–61. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthew AG, Trachtenberg LJ, Yang ZG, et al. An online Sexual Health and Rehabilitation eClinic (TrueNTH SHAReClinic) for prostate cancer patients: A feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:1253–60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06510-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wibowo E, Wassersug RJ, Robinson JW, et al. An educational program to help patients manage androgen deprivation therapy side effects: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14:1557988319898991. doi: 10.1177/1557988319898991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santa Mina D, Matthew AG, Hilton WJ, et al. Prehabilitation for men undergoing radical prostatectomy: A multicenter, pilot, randomized controlled trial. BMC Surg. 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agochukwu NQ, Skolarus TA, Wittmann D. Telemedicine and prostate cancer survivorship: A narrative review. Mhealth. 2018;4:45. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2018.09.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiMartino LD, Birken SA, Mayer DK. The relationship between cancer survivors’ socioeconomic status and reports of followup care discussions with providers. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32:749–55. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitch M, Nicoll I, Lockwood G. Exploring the reasons cancer survivors do not seek help for their concerns: A descriptive content analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002313. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38:976–93. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longo CJ, Fitch MI, Loree JM, et al. Patient and family financial burden associated with cancer treatment in Canada: A national study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:3377–86. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05907-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedden L, Pollock P, Stirling B, et al. Patterns and predictors of registration and participation at a supportive care program for prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:4363–73. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04927-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maddison AR, Asada Y, Urquhart R. Inequity in access to cancer care: A review of the Canadian literature. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:359–66. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asada Y, Kephart G. Equity in health services use and intensity of use in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez CJ, Edwards B, Langelier DM, et al. Delivering virtual cancer rehabilitation programming during the first 90 days of the COVID-19 pandemic: A multimethod study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:1283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Head BA, Keeney C, Studts JL, et al. Feasibility and acceptance of a telehealth intervention to promote symptom management during treatment for head and neck cancer. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.