Keywords: circumferential wall tension, esophageal elongation, esophagus, stress-strain ratio

Abstract

Evidence obtained ex vivo suggests that physical elongation of the esophagus increases esophageal circumferential stress-strain ratio, but it is unknown whether this biomechanical effect alters esophageal function in vivo. We investigated the effects of physical or physiological elongation of the cervical esophagus on basal and active circumferential tension in vivo. The esophagus was elongated, using 29 decerebrate cats, either physically by distal physical extension of the esophagus or physiologically by stimulating the hypoglossal nerve, which activates laryngeal elevating muscles that elongate the esophagus. Hyoid, pharyngeal, and esophageal muscles were instrumented with electromyogram (EMG) electrodes and/or strain gauge force transducers. Esophageal intraluminal manometry was also recorded. We found that physical or physiological elongation of the cervical esophagus increased esophageal circumferential basal as well as active tension initiated by electrical stimulation of the pharyngo-esophageal nerve or the esophageal muscle directly, but did not increase esophageal intraluminal pressure or EMG activity. The esophageal circumferential response to the esophago-esophageal contractile reflex was increased by distal physical elongation, but not orad physiological elongation. We conclude that physical or physiological elongation of the esophagus significantly increases esophageal circumferential basal and active tension without muscle activation. We hypothesize that this effect is caused by an increase in esophageal stress-strain ratio by a biomechanical process, which increases circumferential wall stiffness. The increase in esophageal circumferential stiffness increases passive tension and the effectiveness of active tension. This increase in cervical esophageal circumferential stiffness may alter esophageal function.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Physical or physiological esophageal elongation increases esophageal circumferential active or passive tension by a biomechanical process, which causes a decrease in esophageal circumferential elasticity. This increased stiffness of the esophageal wall likely promotes esophageal bolus flow during various esophageal functions.

INTRODUCTION

The biomechanical effects of distension of the circumferential oriented tissue of the esophagus have been investigated ex vivo by examining the effects of varying intraluminal pressure. It was found that the esophageal circumferential stress-strain relationship was little effected until the intraluminal pressure doubled the resting diameter of the esophagus (1). Therefore, biomechanical effects of bolus distension have little effect on esophageal function until the esophagus is largely distended. This finding is supported by other ex vivo (2–5) and in vivo (6) studies which found that the elastic modulus of the circumferential oriented tissue of the esophagus is low at physiologically normal intraluminal pressure or distension.

On the other hand, the esophagus has a large longitudinal stress-strain ratio such that the esophagus shortens 35% longitudinally when excised (7). In addition, ex vivo studies have found that physical elongation of the esophagus, thereby applying a high longitudinal stress, significantly increases the esophageal circumferential stress-strain ratio (2). These studies suggest that, as opposed to circumferential distension, esophageal elongation might have a significant effect on esophageal circumferential motor function.

Other ex vivo studies have found that the esophageal stress, strain, and modulus of elasticity are greatest in the cervical portion of the esophagus (4). Therefore, it is expected that if esophageal elongation has a biomechanical effect on esophageal function it would most likely occur in the cervical esophagus.

Although prior studies found that physical elongation of the extracted nonfunctional, i.e., ex vivo, esophagus increases esophageal circumferential stress-strain ratio, the aim of this study was to determine whether physical or physiological elongation of the intact functional, i.e., in vivo, cervical esophagus has a biomechanical effect on esophageal circumferential basal or active tension.

METHODS

Experimental Model

We chose to use the decerebrate cat for these studies for three reasons. No other research animal has all of the identified human esophageal reflexes (8–10), and the esophageal reflexes of the decerebrate cat have a similar sensitivity as the same reflexes in the awake human (10). No other mammal used for research has both striated and smooth muscle esophagus in both layers similar to humans (11). The decerebrate cat is an excellent model, as it allows research investigation without the neural inhibition caused by analgesics or anesthetics (12–14).

Animal Preparation

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Cats (n = 29; 7.8 ± 0.3 mo old; 3.5 ± 0.1 kg; 15 males, 14 females) were fasted overnight and decerebrated. The animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (3%), the ventral neck region was exposed, the trachea was intubated, and the carotid arteries were ligated. The skull was exposed, and a hole over a parietal lobe was made using a trephine. The hole was enlarged using rongeurs, the central sinus was ligated and cut, and the brain was severed midcollicularly using a metal spatula. The forebrain was then suctioned out of the skull, and the blood vessels of the Circle of Willis were coagulated by suction through cotton balls soaked in warm saline. The boney sinuses were filled with bone wax, the exposed brain was covered with paraffin oil-soaked cotton balls, and the skin over the skull was sewn closed. The animals were then placed supine on a heating pad (Harvard Homeothermic monitor), and the body temperature was maintained between 38°C and 40°C.

After decerebration, the animals received the following surgical preparation. An incision was made on the ventral surface of the neck, and the esophagus was exposed. Electromyogram (EMG) electrodes were placed on the thyropharyngeus (TP, n = 27), cricopharyngeus (CP, n = 27), and esophagus (Eso) 2 (n = 27) and/or 4 (n = 10) cm from the CP. The CP is the primary muscle (15) of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), and its actions are considered responses of the UES. Strain gauge force transducers were sewn onto the esophagus 2–4 cm from the CP (n = 16) to record circumferential (n = 22) and/or longitudinal muscle tension (n = 11). The abdomen was then opened along the ventral midline and a fistula of the proximal stomach was formed using a 3 mL plastic syringe that exited the abdominal cavity. This fistula was used to insert devices into the esophagus without disturbing the pharynx or larynx. In some animals (n = 9) a short (1 cm long) segment of polyethylene tubing (PE 160, 1 cm in diameter) was inserted into the cervical esophagus through the gastric fistula and sewn to the cervical esophagus 5–6 cm from the CP. A long suture (2-0) was attached to this tubing, which exited the esophagus through the gastric fistula. This suture was attached to a force-displacement transducer (described under Force or tension recording) to record orad tension of the cervical esophagus and to pull the cervical esophagus distally. This tubing allowed the esophagus to be pulled distally while maintaining an open lumen of the esophagus to allow the entrance of a manometric catheter or exit of swallowed boluses. The neck incision was then closed and the wires from the strain gauges exited the incision, and the abdomen was then closed.

Experimental Techniques and Protocols

Esophageal elongation.

We stretched the esophagus longitudinally by two methods: 1) physically by pulling the cervical esophagus distally (n = 9), or 2) physiologically by stimulating the motor nerve of the hyoid muscles (n = 10). For distal physical elongation, the cord attached to the cervical esophageal intraluminal tube was attached to a force-displacement transducer and a known distal force was applied to the cervical esophagus. For orad physiological elongation, the hypoglossal nerve (HG) was transected and stimulated (20–60 Hz, 0.2 ms, 1–10 V) peripherally to activate the suprahyoid muscles. The suprahyoid muscles pull the larynx orad and the larynx is attached to the esophagus at the UES, therefore, contraction of the geniohyoideus and mylohyoideus act to pull the cervical esophagus in an orad direction (16).

Esophageal contraction stimulation.

We stimulated esophageal contraction reflexly, neurally, or directly. For reflex contraction, we stimulated the esophago-esophageal contractile reflex (EECR) by distending a 1 cm long balloon in the thoracic esophagus at 1 mL, 3 mL, and 5 mL air inflation (n = 14). For neural activation, we stimulated the proximal esophageal motor nerve, the pharyngo-esophageal nerve (PEN), using 20–40 Hz, 0.2 ms, and 1–5 V (n = 4). For direct stimulation, we stimulated the esophageal muscle directly through the EMG electrodes using 20–40 Hz, 0.2 ms, and 1–5 V (n = 4).

Ex vivo esophageal stimulation.

We excised the proximal esophagus from the neck with the strain gauges still attached and placed it in a bath of warm saline. We pulled the esophagus longitudinally by hand and recorded circumferential and longitudinal tension (n = 4).

Recording Techniques

All recorded signals were acquired and analyzed using CODAS hardware and software and stored in a computer.

Electromyography.

Bipolar Teflon-coated stainless-steel wires (AS 636; Cooner Wire) bared for 2–3 mm were placed in the muscles, and the wires were fed into differential amplifiers (A-M Systems 1800). The electrical activity was filtered (bandpass of 0.1–3.0 KHz) and amplified 1,000 or 10,000 times before feeding into the computer. The electrical activity was quantified by determining the area under the curve of the EMG response by first rectifying the signal then calculating the integral of the moving average of the responses using CODAS software.

Force or tension recording.

Esophageal wall tension was recorded using strain gauge force transducers composed of precision strain gauge elements (EA-06-031DE-120, Micromeasurements Group) glued onto a copper-beryllium shims, which were waterproofed using polysulfide coating (M Coat JL, Micromeasurements Group) and embedded in Silastic rubber. The strain gauge was recorded from an area of tissue 1 cm long and 0.5 cm wide. The strain gauges were connected to amphenol plugs by Teflon-coated silver-plated copper wires and connected to quarter Wheatstone bridge circuits. Tensions, of pulling the cervical esophagus distally, were recorded and quantified using a Statham force-displacement transducers as described earlier. The implanted strain gauges and force-displacement transducers were attached to low-level DC amplifiers with high-frequency filter at 15 Hz (Grass Instruments 7 P122).

We tested whether the output of the strain gauges was linear by recording successive responses to the addition of known weights. This was important to ensure that the observed changes caused by stimulation of esophageal muscle contraction plus esophageal elongation were due to the esophagus and not to the strain gauge.

Manometry.

A solid-state manometric catheter with six sensors 3 cm apart (Gaeltec 16CT) was inserted into the esophagus through the gastric fistula, and the proximal sensor was placed 2 cm below the UES. The manometric catheter was attached to low-level DC amplifiers with high frequency set at 15 Hz (Grass Model 7 P122).

Data reduction and analysis.

The data were acquired and stored using CODAS hardware and software and statistics quantified using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Differences between control and experimental procedures or between two variables were tested using Student’s t test and when the same animals were tested before and after a procedure, the paired Student’s t test was used. The Pearson correlation coefficient (R2) was calculated to determine whether variables were related to each other. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant, and values were expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Linearity of Strain Gauges

We added a known weight, in the range observed physiologically, to determine whether the strain gauge gives the same output regardless of the basal tension. We found that adding 10 g to a basal tension of 10 g increased the strain tension output to 19.2 ± 1.2 g, which was 0.8 ± 0.09 g (P < 0.01, n = 5) less than the actual weight. Therefore, the strain gauges do not produce an output higher than the actual added tension.

Effect of Esophageal Elongation

Basal circumferential tension.

Physical elongation of cervical esophagus.

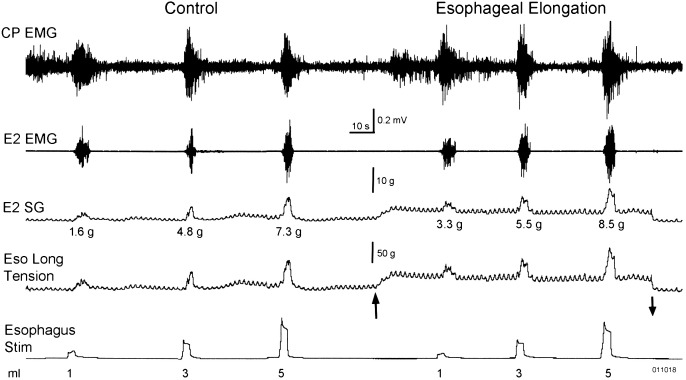

We found that applying 50–100 g of distal longitudinal tension to the cervical esophagus increased the basal circumferential tension of the cervical esophagus (5.8 ± 0.8 g, n = 7, P < 0.05), and this increase in wall tension was not associated with any change in EMG activity (Fig. 1). We examined the effects of distal longitudinal tension of the cervical esophagus on proximal esophageal EMG and in all cases at 2 cm (n = 11) and 4 (n = 8) cm from the UES, no esophageal muscle activation was observed. Therefore, the increase in basal circumferential tension caused by physical elongation is not due to an increase in activation of the esophageal muscle.

Figure 1.

Effect of esophageal physical elongation on basal circumferential tension and reflex activated contraction of the esophagus. The figure shows that applying a force of 50 g (Eso Long Tension at the upward arrow) to pull the cervical esophagus distally increased the basal circumferential tension of the esophagus (E2 SG) about 5 g and increased the maximal response of the esophago-esophageal contractile reflex (EECR) at each distension volume. Note that the changes in E2 SG with increased (up arrow) or decreased (down arrow) esophageal elongation tension were not associated with changes in E2 EMG activity. Therefore, physical esophageal elongation increases both basal and active esophageal circumferential tension without a change in EMG. CP, cricopharyngeus; E#, esophagus number of centimeters from the CP; Eso Long, esophageal longitudinal; EMG, electromyography; g, gram; SG, strain gauge; Stim, EECR stimulation volume distension.

Physiological elongation of cervical esophagus.

We found that electrical stimulation of the HG (3–5 V, 0.2 ms, 30 Hz) increased (5.1 ± 1.2 g, n = 6, P < 0.01) the basal circumferential tension (Fig. 2) of the cervical esophagus and activated contraction of the GH with a mean maximum force of 12 ± 4 g (n = 5). HG stimulation had no significant effect (P > 0.05, n = 9) on cervical esophageal intraluminal manometric pressure (Fig. 3). Electrical stimulation of the HG caused electrical artifact in the EMG recordings (Figs. 2 and 3). Therefore, the increase in circumferential tension due to the physiological elongation of the esophagus does not cause an increase in intraluminal pressure.

Figure 2.

Effect of esophageal physiological elongation on basal esophageal tension. This figure shows that stimulation of the hypoglossal nerve (HG) activates the geniohyoideus (GH) and increases circumferential tension of the esophagus (E2 SG). Contraction of the GH elevates the larynx and elongates the attached cervical esophagus. In addition, increasing stimulation parameters increased contractile strength of the GH and circumferential tension of the esophagus (E2 SG) proportionally. Therefore, physiological elongation of the esophagus increases basal esophageal circumferential tension. CP, cricopharyngeus; E#, esophagus number of centimeters from the CP; EMG, electromyography; g, gram; GH, geniohyoideus; Hz, Hertz; SG, strain gauge; TP, thyropharyngeus; V, volt.

Figure 3.

Lack of effect of physiological elongation of the esophagus on esophageal intraluminal pressure. This figure shows that stimulation of the HG, which contracted the GH and elevated the larynx and cervical esophagus and increased E2 SG tension, had no effect of esophageal intraluminal pressure at 2, 5, and 8 cm from the CP recorded by manometry. Therefore, physiological elongation of the esophagus which increases esophageal circumferential tension does not increase esophageal intraluminal pressure. E#, esophagus number of centimeters from the CP; EMG, electromyography; GH, geniohyoideus; HG Stim, hypoglossal nerve stimulation: g, gram; Hz, Hertz; Mano, manometry; SG, strain gauge; V, volt.

Ex vivo elongation.

After excising the esophagus, we found that stretching the esophagus longitudinally by hand increased (Fig. 4) the magnitude of basal circumferential tension of the cervical esophagus by 6.4 ± 0.8 g (n = 4). The change in circumferential tension was directly related (mean R2 = 0.875 ± 0.048, P < 0.05, n = 4) to the magnitude of the distending tension (Fig. 4). The time delays between the onset and peak of the stimuli applied longitudinally to the esophagus and the circumferential esophageal tension responses were 0.029 ± 0.004 s and 0.036 ± 0.006 s (n = 4), respectively. Therefore, physical elongation of the physiologically disabled esophagus caused an increase in circumferential tension that is very closely related in time and strength to the elongation.

Figure 4.

Effect of esophageal physical elongation on esophageal circumferential tension ex vivo. This figure shows that after the esophagus was excised from the animal, pulling longitudinally on the esophagus caused an increase in esophageal circumferential tension. Note the strong correlation in magnitude and timing between the circumferential and longitudinal tensions. Therefore, the increase in circumferential tension caused by esophageal elongation is a function of the biomechanics of the tissue and not an active muscular response. The vertical arrow shows the short delay from stimulus, i.e., longitudinal tension, to response, i.e., circumferential tension. E#, esophagus number of centimeters from the cricopharyngeus; g, grams; SG, strain gauge.

Physiologically activated circumferential tension.

EECR.

We found that physically pulling the cervical esophagus distally at a force of 50–100 g (Figs. 1 and 5) significantly (P < 0.05) increased the magnitude of EECR recorded by strain gauge, but had no effect on the EECR responses recorded by EMG (Fig. 6). On the other hand, physiologically extending the esophagus longitudinally in the orad direction by stimulation of the HG (Figs. 7 and 8) failed to significantly (P > 0.05) alter the EECR responses. Therefore, physical but not physiological elongation of the esophagus increased the motor effectiveness of an esophageal contractile reflex.

Figure 5.

Quantitative effect of esophageal physical elongation on reflex activated contraction of the esophagus. This figure shows that elongation of the esophagus distally using a force from 50 to 100 g significantly increased the magnitude of the EECR responses of the cervical esophagus. Therefore, the effect of esophageal elongation on reflex contraction of the esophagus is statistically significant. *P < 0.05, n = 6. The horizontal bars are mean and SE. Ctl# or Exp#, control or experimental EECR response activated by number of milliliters stimulation. EECR, esophago-esophageal contractile reflex.

Figure 6.

Quantitative effect of esophageal physical elongation on reflex activated cervical esophageal EMG response. This graph shows that pulling distally on the cervical esophagus using a force from 50 to 100 g did not cause a statistically significant increase in EMG activity (P > 0.05, n = 5) caused by activation of the EECR. Therefore, esophageal elongation increases reflex activated contraction of the esophagus without any significant increase in activation of the esophageal striated muscle. The horizontal bars are mean and SE. # mL or # mL +, number of milliliters stimulation of EECR without (# mL) or with (# mL +) esophageal elongation. EECR, esophago-esophageal contractile reflex; EMG, electromyography.

Figure 7.

The effect of cervical esophageal physiological elongation on reflex activation of the esophagus. This figure shows that stimulation of the HG activates contraction of the GH, which elevates the larynx and elongates the esophagus and increases the magnitude of the esophageal circumferential tension, but not intraluminal pressure, at each volume of stimulation of the EECR. However, the increases in esophageal circumferential tension during simultaneous activation of EECR and HG stimulation are not greater than with EECR stimulation alone. Therefore, physiological elongation of the esophagus increases basal but not reflex activated circumferential esophageal tension. EECR, esophago-esophageal contractile reflex; E#, number of centimeters from the cricopharyngeus; EMG, electromyography; g, grams; GH, geniohyoideus; HG, hypoglossal nerve; Hz, Hertz; Mano, manometry; SG, strain gauge; Stim, stimulation; V, volt.

Figure 8.

Quantitation of the effect of physiological elongation of the esophagus on the reflex activation of esophageal circumferential tension. This graph shows that stimulation of the HG does not significantly [P > 0.05 (n = 5) for 1, 3, or 5 mL] increase the effects of EECR. The horizontal bars are mean and SE. Ctl# or Exp#, control or experimental EECR response activated by number of milliliters stimulation; HG, hypoglossal nerve.

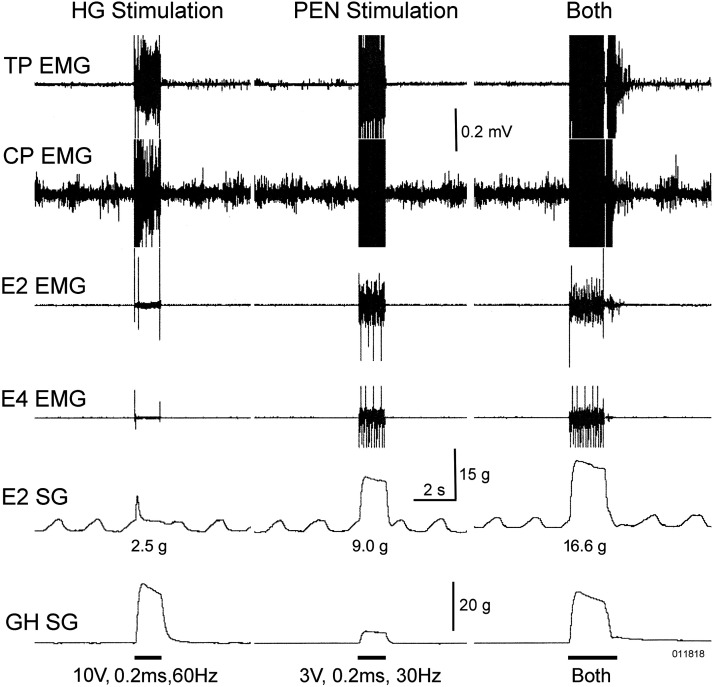

PEN stimulation.

We found that the magnitude of PEN-stimulated contraction of the cervical esophagus was significantly increased physically by pulling (Fig. 9) the cervical esophagus distally at 50–100 g (5.3 ± 0.8 g vs. 7.0 ± 1.2 g (P < 0.02, n = 5) or physiologically by stimulation (Fig. 10) of the HG [7.4 ± 3.1 g vs. 8.0 ± 3.2 g (P < 0.03, n = 3)]. Therefore, physical and physiological elongation of the esophagus increased the circumferential motor effectiveness of motor nerve activation of the esophagus.

Figure 9.

Effect of physical elongation of the cervical esophagus on the physiological activation of circumferential esophageal tension. This figure shows that applying distal forces of 50–100 g to the cervical esophagus increased the contractile response of the cervical esophagus to stimulation of the motor nerve of the cervical esophagus, i.e., the pharyngeal esophageal nerve (PEN). In addition, greater distal tension of about 100 g, i.e., the first increase in distal tension, had a greater effect than distal tension of about 50 g, i.e., the second increase in distal tension. CP, cricopharyngeus; E#, number of centimeters from the cricopharyngeus; EMG, electromyography; Eso Long Tension, longitudinal tension applied to the esophagus; g, grams; SG, strain gauge; TP, thyropharyngeus; V, volt.

Figure 10.

Effect of physiological elongation of the esophagus on the physiological activation of circumferential esophageal tension. This figure shows that stimulation of the HG increased the cervical esophageal circumferential response to stimulation of the PEN. The simultaneous stimulation of the PEN and HG increased (16.6 g) esophageal circumferential tension greater than the stimulation of PEN (9 g) and HG (2.5 g) individually. CP, cricopharyngeus; E#, number of centimeters from the CP; EMG, electromyography; g, grams; GH, geniohyoideus; HG, hypoglossal nerve; Hz, Hertz; PEN, pharyngo-esophageal nerve; SG, strain gauge; TP, thyropharyngeus; V, volt.

Direct esophageal stimulation.

We found that stimulation of the HG (Fig. 11) significantly increased the magnitude of circumferential response to direct stimulation of the cervical esophagus. The simultaneous stimulation of the esophagus and HG increased the esophageal circumferential tension to a level (14.2 ± 1.3 g) which was greater than the addition of responses to stimulation of esophagus (9.7 ± 1.4 g) and HG (1.9 ± 0.3 g) separately. The esophageal response (12.3 ± 1.1 g) to direct esophageal stimulation, with the added HG stimulation, was significantly higher (P < 0.02, n = 4) than the esophageal response to direct esophageal stimulation alone (9.7 ± 1.4 g). Therefore, physiological elongation of the esophagus increased the effectiveness of direct stimulation of the circumferential motor fibers of the esophagus.

Figure 11.

Effect of physiological elongation of the esophagus on esophageal tension responses to direct stimulation of the esophagus. This figure shows that stimulation of the HG increased the esophageal circumferential response to direct electrical stimulation of the cervical esophageal muscle. That is, the simultaneous stimulation of HG and the esophagus directly (17.8 g) was greater than the addition of the HG (3.0 g) and esophagus (12.2 g) stimulated separately. CP, cricopharyngeus; E#, number of centimeters from the CP; Eso, esophagus; g, gram; HG, hypoglossal nerve; Hz, Hertz; TP, thyropharyngeus; V, volt.

DISCUSSION

We found, using the functionally intact, i.e., in vivo, esophagus, that physical as well as physiological elongation of the cervical esophagus significantly increases circumferential cervical esophageal wall basal or active tension. This finding is consistent with ex vivo studies, which found that physical esophageal elongation increases esophageal circumferential stress-strain ratio in nonfunctional extracted esophagus (2). We found that this increase in esophageal wall tension was not associated with an increase in esophageal EMG activity. The cervical esophagus of the cat is composed of striated muscles (11), and all active contractions of striated muscles are accompanied by an increase in EMG activity (17). Therefore, it is likely that this observed increase in esophageal circumferential tension is not due to muscle contraction. Physiological elongation of the esophagus by activation of the laryngeal elevating muscles did not significantly increase intraluminal manometric pressure, indicating that physiological esophageal elongation altered basal circumferential tension without activating contraction of the esophageal circular muscle. Intraluminal manometric pressure of the esophagus is increased by reduction in the luminal diameter caused by the contraction of circular muscle fibers (18). Therefore, we conclude that the esophageal elongation-induced increase in circumferential wall tension was not due to active striated muscle contraction of the esophagus, but due to biomechanical tightening of the circular oriented fibers of the cervical esophagus. Our findings that elongation of the excised, i.e., ex vivo, cervical esophagus also significantly increased basal esophageal circumferential tension confirmed our conclusion that this effect was not mediated by a neural response, but by a biomechanical process.

The physical or physiological elongation of the cervical esophagus not only increased circumferential esophageal basal wall tension, but also the magnitude of esophageal contractile responses stimulated reflexly, i.e., EECR, neurally, i.e., PEN stimulation, or directly, i.e., direct esophageal muscle stimulation. These effects were due to increased esophageal tension, not increased strain gauge output, as our control studies found that the outputs of the strain gauges were not greater than the applied tensions. Given that esophageal elongation increased esophageal contractility due to EECR, PEN, or direct esophageal stimulation, but did not increase EMG responses to EECR, we conclude that these effects on active contractions were also mediated biomechanically.

Although esophageal elongation caused by distal physical tension significantly increased the esophageal circumferential responses to EECR, proximal physiological elongation caused by laryngeal elevation did not. A difference between the responses of the EECR and the other methods used to activate esophageal contraction was the variability, i.e., SE of the responses. The SE’s of the EECR responses were greater than those for PEN or direct esophageal stimulation. This difference in variability of EECR responses compared with other stimuli was probably due to increased complexity of a reflex response compared with motor nerve or direct muscle stimulation. This difference probably contributed to the lack of significance in EECR responses to HG stimulation. Another issue accounting for the difference between HG stimulation and distal longitudinal tension on circumferential esophageal responses during EECR was probably the greater longitudinal tension caused by the distal physical elongation. These differences suggest that an increase in EECR response, or perhaps any physiologically complex muscular response, caused by biomechanical factors requires significant elongation.

We hypothesize that the mechanism for these increases in cervical esophageal circumferential tension during esophageal elongation involve the increase in circumferential wall stiffness that results from increased circumferential stress-strain ratio. The esophagus, especially in the mucosa and submucosa, has significant connective tissue content composed largely of collagen fibers (3, 5, 6). Muscle contractions must first consume the flexibility of the tissue before they are capable of constricting the tissue. Therefore, we hypothesize that the increase in circumferential stress-strain ratio caused by esophageal elongation reduces the esophageal circumferential wall flexibility. This stiffened circumferential esophageal wall allows the esophageal contractile force to more efficiently constrict the esophageal wall. This increased efficiency of constriction causes an increase in wall tension without an increase in active contractile force.

Prior studies found that physical elongation of extracted nonfunctional esophagus increased esophageal circumferential stress-strain ratio, but our studies extended this conclusion in three significant ways. We found that not only did esophageal elongation increase circumferential tension of the extracted nonfunctional esophagus, but also of the fully functional intact esophagus. In addition, not only does physical elongation cause this circumferential effect, but also physiological elongation. Finally, not only does esophageal elongation increase basal esophageal circumferential tension, but also physiologically stimulated active tension of the circumferential fibers of the esophagus. Therefore, although prior studies using extracted nonfunctional esophagus suggested that esophageal elongation may have some esophageal functional role, our studies have proven that such an action is not only possible but highly likely. As such, we hypothesize that this biomechanical process may function under normal physiological conditions, as there are at least two physiological processes that involve significant increases in esophageal elongation, i.e., swallowing (17) and vomiting (19).

In this study, we investigated the cervical esophagus only because in all mammalian species the cervical esophagus is composed of striated muscle, therefore, our study applies to all mammalian species including humans. However, esophageal elongation or stress can occur along the entire esophagus during bolus transport or the longitudinal contraction of peristalsis that could impart a biomechanical effect on the circumferential fibers. Our study demonstrated that such an effect is possible, it is up to future studies to provide a more specific functional and clinical application and understanding of this effect.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This study was supported by NIH grant RO1 DK132082.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.M.L. and R.S. conceived and designed the research. I.M.L. and B.K.M. performed the experiments. I.M.L. analyzed the data. I.M.L. and R.S. interpreted the results of experiments. I.M.L prepared figures. I.M.L. drafted the manuscript. I.M.L., B.K.M., and R.S. edited and revised the manuscript. I.M.L., B.K.M., and R.S. approved final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goyal RK, Biancani P, Phillips A, Spiro HM. Mechanical properties of the esophageal wall. J Clin Invest 50: 1456–1465, 1971. doi: 10.1172/JCI106630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Assentoft JE, Gregersen H, O'Brien WD Jr.. Determination of biomechanical properties in guinea pig esophagus by means of high frequency ultrasound and impedance planimetry. Dig Dis Sci 45: 1260–1266, 2000. doi: 10.1023/a:1005579214416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Natali AN, Carniel EL, Gregersen H. Biomechanical behavior of oesophageal tissues: material and structural configuration, experimental data and constitutive analysis. Med Engn Physics 31: 1056–1062, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vanags I, Petersons A, Ose V, Ozolanta I, Kasyanov V, Laizans J, Vjaters E, Gardovskis J, Vanags A. Biomechanical properties of oesophagus wall under loading. J Biomech 36: 1387–1390, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00160-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stavropoulou EA, Dafalias YF, Sokolis DP. Biomechanical and histological characteristics of passive esophagus: experimental investigation and comparative constitutive modeling. J Biomech 42: 2654–2663, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Orvar KB, Gregersen H, Christensen J. Biomechanical characteristics of the human esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 38: 197–205, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF01307535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu X, Gregersen H. Regional distribution of axial strain and circumferential residual strain in the layered rabbit oesophagus. J Biomech 34: 225–233, 2001. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lang IM, Medda BK, Jadcherla SR, Shaker R. Characterization and mechanisms of the pharyngeal swallow activated by stimulation of the esophagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 311: G827–G837, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00291.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Mechanisms of reflexes induced by esophageal distension. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G1246–G1263, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Mechanism of UES relaxation initiated by gastric air distension. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307: G452–G458, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00120.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stevens CE. Comparative Physiology of the Vertebrate Digestive Tract. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lang IM, Dean C, Medda BK, Aslam M, Shaker R. Differential activation of vagal medullary nuclei during phases of swallowing. Brain Res 1014: 145–163, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Differential activation of pontomedullary nuclei by acid perfusion of different regions of the esophagus. Brain Res 1352: 94–107, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Differential activation of medullary vagal nuclei caused by stimulation of different esophageal mechanoreceptors. Brain Res 1368: 119–133, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lang IM. Upper esophageal sphincter. In: Goyal and Shaker's GI Online, edited by Goyal RK, Shaker R.. New York: Nature Publishing Group, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hadley AJ, Kolb I, Tyler DJ. Laryngeal elevation by selective stimulation of the hypoglossal nerve. J Neural Engn 10: 046013, 2013. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/4/046013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Close RI. Dynamic properties of mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev 52: 129–197, 1972. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1972.52.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brasseur JG, Dodds WJ. Interpretation of intraluminal manometric measurements in terms of swallowing mechanics. Dysphagia 6: 100–119, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF02493487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lang IM, Sarna SK, Dodds WJ. Pharyngeal, esophageal, and proximal gastric responses associated with vomiting. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 265: G963–G972, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.