Abstract

RNA viruses have been the most destructive due to their transmissibility and lack of control measures. Developments of vaccines for RNA viruses are very tough or almost impossible as viruses are highly mutable. For the last few decades, most of the epidemic and pandemic viral diseases have wreaked huge devastation with innumerable fatalities. To combat this threat to mankind, plant-derived novel antiviral products may contribute as reliable alternatives. They are assumed to be nontoxic, less hazardous, and safe compounds that have been in uses in the beginning of human civilization. In this growing COVID-19 pandemic, the present review amalgamates and depicts the role of various plant products in curing viral diseases in humans.

1. Introduction

The continuous increase in the human population has made globalization and contact between people, domestic animals, and wildlife inevitable. This increased connectivity between man and the wild has led to some devastating diseases from wildlife reservoirs with a heavy mortality toll. Some of them like the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), H1N1 influenza, the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza, Nipah virus, Hendra virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Ebola virus (EBOV), and more recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have created havoc in the world [1, 2]. Studies of decades show that the RNA viruses are the most common class of virus, which are often highlighted as the preeminent member of pathogen class that is behind new human diseases, with a rate of 2 to 3 novel viruses being exposed each year [3, 4]. Meanwhile, vaccine development is introduced each time after the advent of new threats. Currently, a number of vaccines are considered to be a critical component in the prevention of viral infections [5], but most of them show side effects, and many of the viruses acquired resistance against them [6]. Therefore, the unavailability of potent vaccines increased mortality numbers. Vaccines are approximately only 50% effective; hence, there is a strong need for antiviral compounds with the ability to suppress viruses, devoid of any or any major side effects [6]. Fascinatingly, traditional medicine has been used in several parts of the worlds like in Asian, African, European, and South American countries. Because the traditional healthcare system is easily culturally acceptable and relatively cheaper compared to costly orthodox medicines [7]. Starting from past to present, wild plants are used traditionally due to having their medicinal properties in between rural communities and the societies to making a bridge in generation after generation, standing in this present scenario where the communication technology developed faster and spread data in wide distances that helps the people to enrich their traditional knowledge, which are essential in our daily life [8]. In addition, as compared to the orthodox system, plant-based natural pharmacotherapy can be used easily as proper alternatives for treating viral diseases [9]. In this review article, our main motive is to highlight the protective measures of RNA viral diseases in humans by using easily available medicinal plants, crude extracts, or active compounds.

2. Potential Pharmacological Targets of RNA Viruses in Host

RNA viruses contain RNA molecule to carry their genetic information. However, it also contains the information required for the synthesis of its own protein. These proteins may help in replication and spread to other susceptible host. Due to their reduced coding capacity, they are dependent on host cell to complete multiplication cycle [10]. This generalized strategy is followed by many other RNA viruses like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [11]. Corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the RNA virus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a serious threat to mankind as well as the world economy [2]. Most interestingly, host RNA-binding protein is attached with the specific architecture of RNA. In case of SARS-CoV-2, infection cycle is started by the interaction of receptor-binding domain (RBD) with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors present on the cell surface of human. After binding, transmembrane protease and serine 2 cleaved S protein facilitate the entry of virus. The SARS-CoV-2 particles enter the host through either direct membrane fusion or endocytosis. After its translation to polypeptides, the main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) cleaved the translated polypeptides to release nonstructural proteins (nsps), whereas RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase (RdRp) facilitates RNA transcription and replication. On the other hand, its mRNA is translated to produce structural and accessory proteins in endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Then, structural proteins are assembled with nucleocapsid into the secretory vesicles (lumen). Finally, the assembled SARS-CoV-2 particles were released by following the exocytosis method [12].

3. Efficiency of RNA Viruses for Pathogenesis

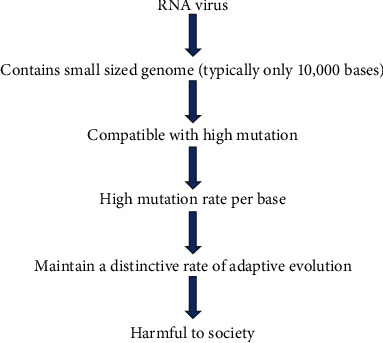

Till now, 13 families of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and 1 family of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus have been included in virus classification [13]. ssRNA viruses are further classified with having either positive or negative sense strands [14]. Those viruses are capable to modify cellular metabolism upon successful infection [15]. They invariably use host cell ribosomes for the production of protein and related enzymes [16]. Interestingly, RNA viruses have tremendous adaptability to a new environment. They can also be able to handle harsh situations related to different selection pressures encountered, though the selective pressures not only include the host's immune system and defense mechanisms but are also encountered by challenges created through the application of drugs such as protease inhibitors of hepatitis B and C virus and inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase [1]. Due to exceptionally shorter generation times and faster evolutionary rates, in a very short-time span, only the RNA viruses are able to transmit a disease to new host species [1]. The fast evolutionary rate of RNA viruses incurred due to the rapid rate of replication errors [17]. It is justified by many studies that the rate of mutation of RNA viruses is about six times greater than that of their cellular hosts. This is remarkably due to high mutation rate, which helps to maintain a distinctive rate of adaptive evolution that is shown in Figure 1 [1]. Basic mode of infection related to other factors are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Natural outline of RNA viruses in causing disease.

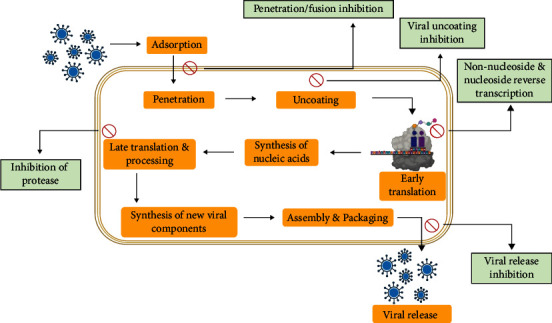

Figure 2.

Basic mode of action and related inhibitory factors of virus.

4. Plant-Based Therapies against RNA Viral Disease

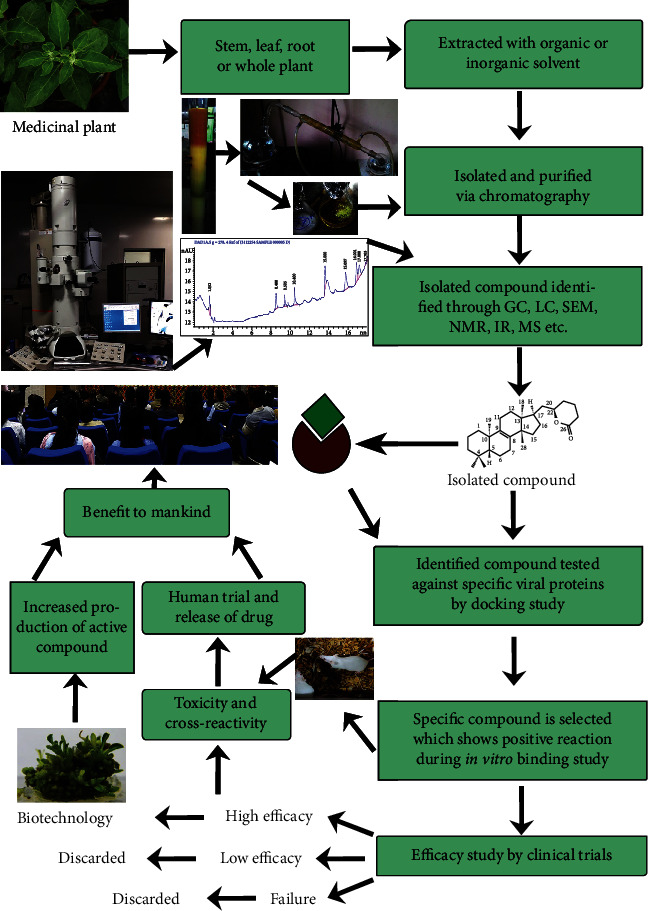

Medicinal plant (MP) contains a substantial amount of pharmacologically important secondary metabolites that can be used for therapeutic purposes. Since the very past, different plant parts or extracts had been utilized by local people to prevent many diseases up till now [18]. Interestingly, viral infections with sharp mortality and morbidity rates are one of the most key concerns of human deaths worldwide [6]. In this irresistible situation of global pandemic, world research has been shifted to find out potential vaccines [4]. Due to the lack of vaccines and other standard therapies, viral diseases grow rapidly throughout the world. In this situation, discovery of the novel antiviral drugs is of utmost importance. Moreover, cost-effectiveness and high efficacy are always a matter of concern for drug discovery [19]. In many cases, the synergistic effect of plant extract in combinations with other compounds has shown better results against these diseases [20]. Since the very early times, active compounds were isolated and identified by following the bioassay-guided fractionation techniques that take longer time and most of the times do not show positive results. The recent methods of drug discovery are more efficient due to quick isolation and faster progression of novel drug formulation that also includes rapid clinical trials [21]. A concise strategy for natural drug discovery is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive scheme of natural drug discovery from the medicinal plants.

On the other hand, commonly used natural plant products in Ayurveda are clearly mentioned in Susruta Samhita and Charaka Samhita or it can be obtained through traditional knowledges [22]. Conventionally used extracts of specific plant parts like roots, bark, stem, seeds, fruits and flowers, dietary supplements, plant derivatives (phyto-constituents), and nutraceuticals found wide applications in the treatment of wide range of diseases. Besides that, the survey report indicates that among commonly used medicines, one quarter of the compounds are isolated from plant sources [22]. Hence, the scientists working on drug discovery are trying to focus on the medicinal plants used in ethnobotany and trying to document them to establish their natural, inherent, and positive effects against specific diseases [7, 23]. But in comparison with the investigation of antimicrobial properties, the investigation of plant-derived antiviral substances is insufficient [24, 25].

4.1. Herbal Extracts against RNA Viral Diseases of the Human

Traditionally, medicinal plants are being used to cure various human diseases. Most of the Asian countries like China, Japan, and India have a great past history of usage of medicinal plant and mushroom extracts [26]. Amalgamation of conventional knowledge and advance research techniques in the field of natural drug discovery imports a huge number of novel products from plants. Due to less side effects and toxicity, it has been preferred by the common users. Not only that the cost-effectiveness of those natural products provides a value addition and also increased its accessibility [27]. Those products can be able to provide broad spectrum protective measures to numerous health hazards including viral infections. In case of the treatment of SARS-CoV-2, a formulation composed of 6.6% of each of the 15 plants, viz., Zingiber officinale (ginger), Adhatoda vasica (malabar nut), Piper longum (long pepper), Andrographis paniculata (bitterweed), Tragia involucrata (Indian stinging nettle), Syzygium aromaticum (clove), Terminalia chebula (chebulic myrobalan), Hygrophila auriculata (kokilaksha), Cyperus rotundus (java grass), Plectranthus amboinicus (Indian borage), Clerodendrum serratum (bharangi), Tinospora cordifolia (guduchi), Saussurea costus (costus), Sida acuta (teaweed), and Anacyclus pyrethrum (akarkara), has been recommended by the Ministry of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Unani, Yoga, and Naturopathy, Siddha, and Homoeopathy), Government of India [28]. The antiviral activity of many plant extracts and compounds of plant origin has been reported, which includes aqueous extracts of Cassine xylocarpa stem (Celastraceae), Maytenus cuzcoina root & bark (Celastraceae) [9], and crude methanolic extract of roots of four Lamiaceae members, viz., Thymus carmanicus (Thyme), Thymus vulgaris, Thymus kotschyanus, and Thymus daenensis [9, 29], which are used to cure HIV infection; aqueous extract of Nerium oleander (kaner, Apocynaceae) is used against Poliovirus type 1 [30]; methanolic extract of Bryophyllum pinnatum (life plant, Crassulaceae), Mondiawhitei (white's ginger, Periplocaceae), Terminalia ivorensis (black afara, Combretaceae), Ageratum conyzoides (goat weed, Asteraceae) are used to cure echovirus [7]; aqueous and ethanol extracts of dried leaves of Andrographis paniculata (Acanthaceae) and Gynostemma pentaphyllum (poor man's ginseng, Cucurbitaceae) are used to prevent avian influenza virus (H5N1) [31] etc. Table 1 summarizes the use of plant extracts against the human RNA-viral diseases.

Table 1.

Plant extract used as anti-RNA viral activity in human.

| S. no. | Family | Plant name | Antiviral activity against | Traditional use of plant | Name of city and countries where these were used | Extraction method and parts used | Mechanism of action/reduction of disease intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acanthaceae | Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees [Bitterweed] | Dengue virus (DENV) | By tribal healers, ojha, baidya, medicine men of Bihar | Bihar (state of India) [32] | Crude extract of whole plant | Inhibits the activity of DENV-1 in infected Vero cells in in vitro assay [33] |

| 2. | Acanthaceae | Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees [Bitterweed] | Avian influenza virus (H5N1) | Aerial parts and roots used as traditional medicine in India, China, Thailand, and other Southeast Asian countries to treat many diseases | India, China, and Thailand (countries of Asia) [34] | Water and ethanol extract of leaves [31] | Induce upregulation of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression that inhibit viral replication in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in an in vitro investigation [31] |

| 3. | Moraceae | Ficus fistulosa Reinw. ex BI. [Kelampung Bukit] | Hepatitis C virus | In folk medicine against respiratory disorder, convulsion, and tuberculosis [35] | 80% population of some Asian and African countries and Bangladesh (country in South Asia) [36] | Ethanolic extract of leaves [37] | Inhibition of viral entry [37] |

| 4. | Anacardiaceae | Schinus molle L. [American pepper] | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | In folk medicine for treating ulcers, wounds, diarrhea, toothache, menstrual disorders, rheumatism, and respiratory problem that are found in many Brazilian medical literature, as stimulant, antitumor, antifungal, antiseptic, tonic, diuretic, anti-plasmodic, antioxidant, antibacterial agent | Brazil (country of South America) [38] | Crude methanolic extract of leaves [39] | Protects MT-2 T-lymphoblastoid cell from cytopathic effect of HIV [39] |

| 5. | Cucurbitaceae | Gynostemmapentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino [Southern Ginseng or Miracle Plant] | Avian influenza virus (H5N1) | In Southeast Asian countries as herbal medicine to treat diabetes, as antioxidant, antitumor, cholesterol-lowering agent, treatment of chronic tracheitis, bronchitis, infectious hepatitis, pyelitis and gastroenteritis in Chinese medicine | China, (countries in East-Asia) and southeast Asian countries [31] | Water and ethanol extract of dried leaves [31] | Induce upregulation of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression that inhibit viral replication in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in an in vitro investigation [31] |

| 6. | Equisetaceae | Equisetum giganteum L. [Southern giant horsetail] | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | In herbal medicine in Central and South America, diuretic agent in ethnomed [40] icine | Brazil (country of South America) and some other countries of Central and South America [41] | Crude methanolic extract of stem [39] | Protects MT-2 T-lymphoblastoid cell from cytopathic effect of HIV [39, 41] |

| 7. | Zingiberaceae | Curcuma longa L. [turmeric] | Avian influenza virus (H5N1) | Traditional medicine in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and China, as antiseptic for cuts, bruises, and burns in South Asia | India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan (countries in South-Asia) and China (country in East-Asia) [42] | Water and ethanol extract of root [31] | Induce upregulation of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression that inhibits viral replication in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in an in vitro investigation [31] |

| 8. | Apocynaceae | Calotropis procera (Aiton) W.T.Aiton [Calotrope] | Dengue virus (DENV) | By tribal healers, ojha, baidya, medicine men of Bihar | Bihar (state of India) [33] | Crude extract of leaf and bark [33] | Kills larvae of Aedes aegypti [43] |

| 9. | Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. [papaya] | Dengue virus (DENV) | By traditional healers and local people of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh; local practitioners and traditional healers of Goa, local people of north eastern plain zone of India | Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Goa (states of India) and north eastern plain zone of India (country in South Asia) [33, 44] | Leaf extract [45] | Increases platelets due to administration of extract [45] |

| 10. | Meliaceae | Azadirachta indica A. Juss. [neem] | Dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) | By traditional healers and tribals of various districts of Bihar | Bihar (state of India) [33] | Leaf extract [33] | In vitro and in vivo study showed reduction of virus [33] |

| 11. | Zingiberaceae | Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker [Thai ginseng] | Avian influenza virus (H5N1) | In Thai medicine to treat leucorrhoea, oral disease, stomach discomfort, health promotion, as antifungal, antiflatulent, antiplasmodial agent, powder with ethanol used to cure peptic ulcers, diabetes, asthma | Thailand (country in Asia) | Water and ethanol extract of root [31] | Induce upregulation of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression that inhibit viral replication in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in an in vitro investigation [31] |

| 12. | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia officinalis Rehder & Wilson [Houpo magnolia] | Dengue virus type 2 | In eastern medicine, Chinese medicine Hou-Pu that have been used in analgesic, distension, or anxiety relief [46] | China (country in East Asia) | Methanolic extract of bark [47] | Inhibits intracellular DENV-2 replicon [47] |

| 13. | Lamiaceae | Thymus carmanicus Jalas [Avishan] | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) | Decoction and infusion used for cold in Iranian traditional medicine, as anti-inflammatory, digestive, carminative agents | Iran (country in Western Asia) | Methanolic extract of root [29] | Effect on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) toxicity and HIV-1 replication [29] |

| 14. | Lamiaceae | Thymus vulgaris L. [thyme] | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) | Decoction and infusion used for cold in Iranian traditional medicine, in folk medicine for asthma and bronchitis, as anti-inflammatory, digestive, carminative, antiseptic, antifungal, antiviral, antimicrobial agents | Iran (countries in Western Asia) | Methanolic extract of root [29] | Effect on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) toxicity and HIV-1 replication [29] |

| 15. | Lamiaceae | Thymus kotschyanus Boiss. & Hohen. [thyme] | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) | Decoction and infusion used for cold in Iranian traditional medicine, as anti-inflammatory, digestive, carminative agents | Iran (country in Western Asia) | Methanolic extract of root [29] | Effect on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) toxicity and HIV-1 replication [29] |

| 16. | Lamiaceae | Thymus daenensis Celak [thyme] | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) | Decoction and infusion used for cold in Iranian traditional medicine, as anti-inflammatory, digestive, carminative agents | Iran (countries in Western Asia) | Methanolic extract of root [29] | Effect on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) toxicity and HIV-1 replication [29] |

| 17. | Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. [guava] | Avian influenza virus (H5N1) | In South-Eastern Nigeria to treat cough, malaria, stomach disorders, and loss of appetite | Nigeria (country in West Africa) [48] | Water and ethanolic extract of dried leaves [31] | Induce upregulation of IFN-β and TNF-α mRNA expression that inhibit viral replication in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in an in vitro investigation [31] |

| 18. | Verbenaceae | Clerodendrum serratum (L.) Moon. [Bharangi] | Yellow fever virus | Used in Yunani, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Japanese Kampo medicine | China, Japan (countries in East Asia) [49] | Ethanolic and methanolic extract of whole plant [50] | Prevent viral infection through the bite of mosquito vector [50] |

| 19. | Combretaceae | Terminalia chebula Retz. [Chebulic myrobalan] | Enterovirus | Used in Yunani, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Japanese Kampo medicine | China, Japan (countries in East Asia) [49] | Ethanolic and methanolic extract of leaves [50] | Inhibits viral replication [50] |

| 20. | Vitaceae | Ampelocissus tomentosa (Heyne ex Roth) Planch. [hairy wild grape] | Chikungunya virus | Used in Yunani, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Japanese Kampo medicine | China, Japan (countries in East Asia) [49] | Ethanolic and methanolic extract of root [50] | Inhibits viral replication [50] |

| 21. | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. [flaming Katy] | Chikungunya virus | Used in Yunani, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Japanese Kampo medicine | China, Japan (countries in East Asia) [49] | Ethanolic and methanolic extract of leaves [50] | Inhibits viral replication [50] |

| 22. | Cupressaceae | Thuja orientalis L. [Chinese thuja] | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | In traditional medicine and homeopath, to treat bronchitis, skin infection, excessive menstruation, arthritic pains, coughs, dysentery, named as Chinese Thuja, in other regions of the Asian continent | China (country in East Asia) and in other regions of the Asian continent | Oil extract of plant [51] | Inhibits viral replication [51] |

| 23. | Cupressaceae | Juniperus oxycedrus L. [Cade juniper] | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | In infectious disease, colds, fungal infections, cough, gynecological disease, wounds in Turkish folk medicine, as anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive | Turki (lying partly in Asia and partly in Europe) [52] | Oil extract of plant [51] | Inhibits viral replication [51] |

| 24. | Elaeagnaceae | Hippophae rhamnoidesL. [Sea buckthorn] | Dengue virus type-2 (DENV-2) | In Tibetan traditional and Chinese medicine | Tibet is a part of China (country of East Asia) [53] | Alcoholic extract of leaves [33] | Decreases THF-α, increases INF-γ production, increases cell viability in in vitro assay against dengue virus type-2 [33] |

| 25 | Menispermaceae | Tinospora cordifolia (Thunb.) Miers [Guduchi] | Dengue virus (DENV) | In traditional folk medicine of India for treating diabetes | India (country in South Asia) [54] | Decoction of stems [55] | Reduce inflammation and fever, enhance the killing ability of macrophages [55] |

There is not a single medicine, which is globally accepted for the treatment of dengue fever. However, extracts obtained from different plants are expected to lower the severity of dengue viruses by increasing the platelet count, which includes Carica papaya leaf extract that is used by the local people of North Eastern plain zone of India, Madhya Pradesh [33, 56], whole plant of Andrographis paniculata (bitterweed), Alternanthera sessilis (sessile joyweed), Achyranthus aspera (prickly chaff flower), and Solanum xanthocarpum (yellow-fruit nightshade), and leaf and bark of Calotropis procera (calotrope) used in Bihar by traditional healers [32, 33]. In some clinical trials, it has been confirmed that the administration of leaf extract of Carica papaya (papaya) on patients with dengue fever increases their platelet count [33, 45]. More specifically, as we are facing SARS-CoV-2 in present days, so it is required to know the name of the phytochemicals and their classes to check the intensity of this virus [57]. Table 2 represents a list of phytochemicals acting against various targets of SARS-CoV-2, where most of the phytochemical binds with spike protein ACE2 (like anthraquinone, emodin, rhein, and cinnamaldehyde) or inhibits main protease (Mpro) (like somniferine, isorientin, and gallocatechin-3-gallate) [57].

Table 2.

List of phytochemicals acting against various targets of SARS-CoV-2.

| Sl no. | Phytochemical | Class of phytochemical | Targets | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Fisetin | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein like hACE2-S | [58] |

| 2. | Quercetin | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein | [58] |

| 3. | Dithymoquinone | Terpene | Inhibits spike glycoprotein-ACE2 interface | [59] |

| 4. | Glycyrrhizic acid | Saponin | Binds with spike protein RBD-ACE2 | [60, 61] |

| 5. | Hesperidin | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein ACE2 | [62] |

| 6. | Emodin | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein ACE2 | [62] |

| 7. | Carvacrol | Phenol | Interacts with spike protein ACE2 | [59] |

| 8. | Rhein | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein ACE2 | [62] |

| 9. | Kaempferol | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein hACE2-S | [58] |

| 10. | Cinnamaldehyde | Flavonoid | Interacts with spike protein ACE2 | [59] |

| 11. | Cinnamyl acetate | Styrene | Interacts with spike protein ACE2 | [59] |

| 12. | Chrysin | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein ACE2 | [62] |

| 13. | Anthraquinone | Flavonoid | Bind with spike protein ACE2 | [62] |

| 14. | Anethole | Flavonoid | Interacts with spike protein ACE2 | [59] |

| 15. | Geraniol | Terpene | Interacts with spike protein ACE2 | [59] |

| 16. | L-4-terpineol | Terpene | Interacts with spike protein ACE2 | [59] |

| 17. | Andrographolide | Terpenoid | Inhibits Mpro protease | [63] |

| 18. | Withanoside V | Inhibits Mpro protease | [64] | |

| 19. | Somniferine | Inhibits Mpro protease | [64] | |

| 20. | Epigallocatechin gallate | Phenol | Inhibits Mpro protease | [65] |

| 21. | Gallocatechin-3-gallate | Phenol | Inhibits Mpro protease | [65] |

| 22. | Tinocordiside | Inhibits Mpro protease | [64] | |

| 23. | Vicenin | Inhibits Mpro protease | [64] | |

| 24. | Isorientin | Inhibits Mpro protease | [64] | |

| 25. | Berbamine | Targets on spike protein ACE2 | [66] | |

| 26. | Castanospermine | Reduced viral RNA | [67] | |

| 27. | Epicatechin gallate | Phenol | Inhibits Mpro protease | [65] |

Ethanolic and methanolic extracts of Ampelocissus tomentosa (root), Clerodendrum serratum (whole plant), and Terminalia chebula (leaves) are effective against chikungunya virus, yellow fever virus, and entero virus, respectively [50]. Flavonoid extract of Litchi chinensis inhibits 3CLpro [51, 68], and plant extracts of Juniperus oxycedrus (cade juniper), Laurus nobilis (bay tree), Thuja orientalis (thuja) act as viral growth inhibitor [51] against SARS-CoV. Ethanolic extract of Broussnetia papyrifera (paper mulberry) containing Kazinol F and Broussochalcone A, and 3′-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-3′,4,7-trihydroxyflavane showed noncompetitive inhibition on papain like protease (PLpro) of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, respectively [69, 70]. The flavonoids like cinnamaldehyde, chrysin, and anethole bind with spike protein ACE2 of SARS-CoV-2 virus [59, 62]; tinocordiside, somniferine, and withanoside V [64] inhibit Mpro protease, which cleaved translated polypeptides to liberate nonstructural proteins.

4.2. Plant-Derived Active Compounds for Prevention of RNA Viral Diseases in Human

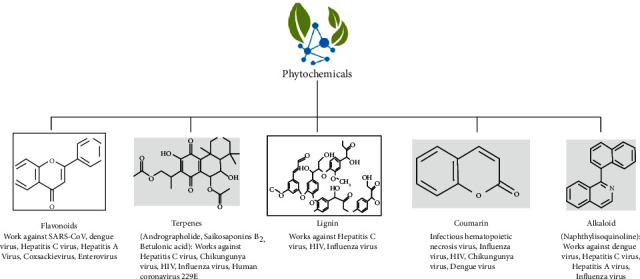

Nowadays, huge proportions of global population choose easily available natural product from their nearby sources to get relief from the emerging health problems. This awareness of common people has induced the interest of the scientists to invent new formulations of plant extracts on the basis of traditional ethnopharmacological knowledge. Sequentially, many pharmaceutical companies are now engaged to produce natural antimicrobial formulations to meet the demand of the global market [71]. Ignatov (2020) explained that high levels of potassium reported from Moringa oleifera helps the patient of COVID-19 to decrease the rate of infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Different plants induce the production of numerous secondary metabolites such as phenolics, essential oils, glycosides, coumarins, alkaloids, terpenoids, and peptides mainly in response to microbial infections or to avoid herbivores and other organisms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Important phytochemicals obtained from medicinal plants.

These metabolites have been accepted to play an essential role in boosting of the immune system and manifesting of antiviral potential [27, 72]. There are several phytochemicals, which are found to be effective against different RNA viruses also; some of which are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Lists of phytochemicals against RNA viruses causing human diseases.

| RNA type | Name of viruses | Family | Therapeutic phytochemicals | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue virus | Flaviviridae | Flavonoid, alkaloid, phenol, and coumarins | [73, 74] |

| Hepatitis C virus | Flaviviridae | Flavonoid, alkaloid, lignan, terpenes, and terpenoids | [75, 76] | |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | Flaviviridae | Flavonoid | [77] | |

| Zika virus | Flaviviridae | Flavonoid | [78] | |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Coronaviridae | Flavonoid (luteolin, curcumin, myricetin, quercetin), anthraquinone (emodin) | [51] | |

| Chikungunya virus | Togaviridae | Flavonoid, terpenes, coumarins, and terpenoids | [73, 76, 79] | |

| Coxsackievirus | Picornaviridae | Flavonoids | [80] | |

| Hepatitis A virus | Picornaviridae | Flavonoids and alkaloids | [81] | |

| Enterovirus | Picornaviridae | Flavonoids | [74] | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Retroviridae | Terpenes and terpenoid lignan, and coumarin | [82, 83] | |

|

| ||||

| Negative-sense ssRNA | Respiratory syncytial virus | Paramyxoviridae | Lignan | [84] |

| Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus | Rhabdoviridae | Coumarin | [85] | |

| Influenza virus (H3N2, H5N2, H5N1, H1N1) | Orthomyxoviridae | Flavonoid, alkaloid, lignan, coumarin, terpenes, and terpenoid | [86, 87] | |

Few recurrent and non-recurrent viral infections include human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and 2 (HIV-2) [27], hepatitis C virus [6], dengue virus [33], and poliovirus. Furthermore, the control and prevention of different emerging viral diseases are imposing a great challenge to the society [88]. About 500,000 plant species are estimated to be present in the world. Interestingly, 10-15% among them are being used as drugs and 10% as a source of food [89]. However, the rapid extinction of some species leads to irretrievable loss of potential phytochemicals and also imposes another serious threat. The anti-RNA viral activity of active compounds from some medicinal plants have been reviewed and summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Medicinally important plant-derived active compounds used for curing human RNA viral diseases.

| S. no. | Family | Plant name | Active compound | Family of virus | Virus name | Type of viral RNA | Human diseases | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. | Theaceae | Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze [tea] | Theaflavin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | [90] |

| 6. | Acanthaceae | Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees [Kalmegh] | Andrographolide | Togaviridae | Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Chikungunya fever | [91] |

| 7. | Ancistrocladaceae | Ancistrocladuskorupensis D.W. Thomas & Gereau | Naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from root bark | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [27] |

| 8. | Berberidaceae | Berbaris amurensis Rupr. [Amur barberry] | Berbamine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [66] |

| 9. | Ancistrocladaceae | Ancistrocladus congolensis J, Léonard | Michellamine-type dimeric naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from root bark | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [92] |

| 10. | Fabaceae | Castanospermum australe A.Cunn & C.Fraser ex Hook. [Blackbean] | Castanospermine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [67] |

| 11. | Halymeniaceae | Cryptonemiacrenulata (J.Agardh) J.Agardh | Galactan | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus type 2, 3 and 4 (DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [39] |

| 12. | Apiaceae | Bupleurum sp. | Triterpene glycosides (named Saikosaponins B2) | Coronaviridae | Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-22E9) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Nosocomial respiratory viral infection (NRVI) | [93] |

| 13. | Fabaceae | Tephrosia madrensis Seem. [Hoarypea] | Glabranine and 7-O-methyl-glabranine from leaves and flowers | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus (DENV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [94] |

| 14. | Apiaceae | Heteromorpha sp. | Triterpene glycosides (named Saikosaponins B2) | Coronaviridae | Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-22E9) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Nosocomial respiratory viral infection (NRVI) | [93] |

| 15. | Moraceae | Broussnetiapapyrifera (L.) Vent. [paper mulberry] | Kazinol F, Broussochalcone A from roots | Coronaviridae | Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome | [69, 70] |

| 16. | Nelumbonaceae | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. [lotus] | Isoliensinine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [95] |

| 17. | Nelumbonaceae | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. [lotus] | Liensinine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [95] |

| 18. | Moraceae | Broussnetiapapyrifera (L.) Vent. [paper mulberry] | 3′-(3-Methylbut-2-enyl)-3′,4,7-trihydroxyflavane from roots | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [70] |

| 19. | Polygonaceae | Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke | Emodin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 20. | Ranunculacea | Thalictrum podocarpum Kunth ex DC. [Meadow-rue] | Hernandezine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [96] |

| 21. | Polygonaceae | Rheum officinale L. [Chinese rhubarb] | Emodin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 22. | Zingiberaceae | Curcuma longa L. [turmeric] | Curcumin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 23. | Nelumbonaceae | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. [lotus] | Neferine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [95, 96] |

| 24. | Myricaceae | Myrica faya Ait. [fire tree] | Myricetin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 25. | Meliaceae | Toona sinensis (A.Juss.) M.Roem. [Chinese mahogany] | Quercetin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 26. | Rubiaceae | Cinchona officinalis L. [Lojabark] | Quinacrine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [97] |

| 27. | Linaceae | Linum usitatissimum L. [Flax] | Herbacetin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51, 68] |

| 28. | Lamiaceae | Scutellaria lateriflora L. [blue skullcap] | Scutellarein | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 29. | Fabaceae | Pterocarpus santalinus L. f. [red sanders] | Savinin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 30. | Cupressaceae | Chamaecyparis obtusa var. formosana [Taiwan yellow cypress] | Betulonic acid, Savinin, Hinokinin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 31. | Celastraceae | Triterygium regelii Sprag. & Takeda [Regel's threewingnut] | Iguesterin, Tingenone, Pristimerin, Celastrol | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 32. | Brassicaceae | Isatisindigotica fortune [Chinese woad] | Sinigrin, Hesperetin | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 33. | Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum L. [garlic] | Allyl trisulfide, allyl disulfide | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51, 98] |

| 34. | Acanthaceae | Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees [Kalmegh] | Andrographolide | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [88] |

| 35. | Meliaceae | Aglaia sp. | Silvestrol | Coronaviridae | Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Nosocomial respiratory viral infection (NRVI) | [70, 99] |

| 36. | Meliaceae | Aglaia sp. | Silvestrol | Coronaviridae | Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome | [99] |

| 37. | Ranunculaceae | Nigella sativa L. [black cumin] | Dithymoquinone | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [59] |

| 38. | Solanaceae | Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal [Ashwagandha] | Withanoside V | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [64] |

| 39. | Solanaceae | Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal [Ashwagandha] | Somniferine | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [64] |

| 40. | Phyllophoraceae | Gymnogongrusgriffithsiae (Turner) C. Martius | Sulphated polysaccharide (named kappa carrageenan) from whole plants | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [94] |

| 41. | Solanaceae | Atropa belladonna L. [belladonna] | l-hyoscyamine, atropine, Belldonic, Scopoletin (l-methyl aesculetin), hyoscine, and pyridine and N-methyl praline | Filoviridae | Ebola virus | Negative-sense ssRNA | Ebola haemorrhagic fever (Ebola HF) | [100, 101] |

| 42. | Scrophulariaceae | Scrophularia scorodonia L. [Balm-leaved Figwort] | Triterpene glycosides (named Saikosaponins B2) | Coronaviridae | Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-22E9) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Nosocomial respiratory viral infection (NRVI) | [93] |

| 43. | Chordariaceae | CladosiphonokamuranusTokida [Mozuku] | Fucoidan from whole plants | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [94] |

| 44. | Fabaceae | Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit [white leadtree] | Galactomanan from seeds | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus (DENV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [94] |

| 45. | Theaceae | Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze | Epicatechin gallate | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [65] |

| 46. | Menispermaceae | Tinospora cordifolia (Thunb.) Miers [Gurjo] | Tinocordiside | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [64] |

| 47. | Fabaceae | Mimosa scabrella Benth. [Bracatinga] | Galactomanan from seeds | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus (DENV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [94] |

| 48. | Celastraceae | Cassine xylocarpa Vent. [Marbletree] | Pentacyclic lupane-type triterpenoids | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [9] |

| 49. | Celastraceae | Maytenus cuzcoina Loes. | Pentacyclic lupane-type triterpenoids | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [9] |

| 50. | Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus emblica L. [Indian gooseberry] | Highly oxygenated norbisabolane sesquiterpenoids (Phyllaemblicins H1-H14) from root | Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A virus strain H3N2 | Negative-sense ssRNA | Influenza (flu) | [9] |

| 51. | Lamiaceae | Ocimum sanctum L. [Tulsi] | Vicenin | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [64] |

| 52. | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia officinalis Rehder & Wilson [Houpo magnolia] | Honokiol | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [9] |

| 53. | Lamiaceae | Ocimum sanctum L. [Tulsi] | 4′-O-glucoside 2″-O-p-hydroxybenzoagte | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [64] |

| 54. | Fabaceae | Tephrosia madrensis Seem. | Methyl-hildgardtol A from leaves and flowers | Flaviviridae | Dengue virus (DENV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Dengue (Breakbone fever) | [94] |

| 55. | Lamiaceae | Ocimum sanctum L. [Tulsi] | Isorientin | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [64] |

| 56. | Theaceae | Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze | Gallocatechin-3-gallate | Coronaviridae | Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) | Positive-sense ssRNA | COVID-19 | [65] |

| 57. | Fabaceae | Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit [White leadtree] | Epicatechin gallate | Flaviviridae | Yellow fever virus | Positive sense ssRNA | Yellow fever | [94] |

| 58. | Papaveraceae | Chelidonium majus L. [greater celandine] | Low-sulfated poly-glycosaminoglycan moiety from freshly prepared crude extract | Retroviridae | Retrovirus (HIV) | ssRNA | AIDS | [27] |

| 59. | Gentianaceae | Swertia bimaculata (Siebold & Zucc.) Hook. f. & Thomson ex C.B. Clarke [double-spotted Swertia] | Sesterterpenoid | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [27, 102] |

| 60. | Gentianaceae | Swertia punicea Hemsl. | Xanthone | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [27] |

| 61. | Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia neriifolia L. [Indian Spurge Tree] | Diterpenoids (named eurifoloids E and F) | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [27] |

| 62. | Menispermaceae | Stephania tetrandra S. Moore [Fen Fang Ji] | Tetrandrine, Cepharanthine, Fangchinoline | Coronaviridae | Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) | Positive-sense ssRNA | — | [70, 103] |

| 63. | Acanthaceae | Rhinacanthus nasutus (L.) Kurz [Snake jasmine] | Lawsone methyl ether from leaves | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | AIDS | [27] |

| 64. | Lauraceae | Laurus nobilis L. [bay tree] | Beta-ocimene, 1,8-cineole, alpha-pinene, beta-pinene in extracted oil from plant | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Positive-sense ssRNA | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | [51] |

| 65. | Ranunculaceae | Nigella sativa L. [black cumin] | Thymoquinone, nigellimine | Coronaviridae | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), | Positive-sense ssRNA | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | [104] |

Few preidentified compounds from different traditional medicinal plants of China showed protective actions against SARS-CoV-2 like betulinic acid, lignin, and sugiol on replication and chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro); coumaroyltyramine, cryptotanshinone, kaempferol, N-cis-feruloyltyramine, quercetin, and tanshinone IIa on papain like protease (PLpro) and 3CLpro; desmethoxyreserpine on replication, 3CLpro, and entry; dihydrotanshinone on entry and spike protein; and dihomo-c-linolenic and moupinamide on 3CLpro and PLpro, respectively, to prevent COVID-19 [70, 105]. Furthermore, theaflavin of Camellia sinensis (tea) shows biological action by binding on RNA-dependent RNA polymerase against SARS-CoV-2 [90]. Several drugs, which are previously approved by FDA for other diseases, are again used for the treatment of COVID-19 patients. These drugs include chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which are generally used as inhibitors of endosomal acidification fusion and auranoin for redox enzymes that helps to treat rheumatoid arthritis [106, 107]. Allyltrisulfide and allyldisulfide isolated from Allium sativum (garlic) act as ACE2 receptor inhibitors [51, 98]; herbacetin from Linum usitatissimum (flax) [51, 68], betulonic acid, savinin, and hinokinin from Chamaecyparis obtusa var. formosana (Taiwan yellow cypress) act as 3CLpro inhibitor against SARS-CoV; Scutellaria lateriflora (blue skullcap) helps to prevent SARS-CoV by scutellarein as helicase inhibitor [51]. Furthermore, thymoquinone and andnigellimine from Nigella sativa (fennel flower) show the blocking of virus entry into pneumocyes and increasing the Zn2+ uptake to boost host immune response against SARS-CoV-2 [104]. The recent evidences showed that vicenin, isorientin, and 4′-O-glucoside 2″-O-p-hydroxybenzoagte obtained from Ocimum sanctum L. inhibit Mpro protease activity during SARS-CoV-2 viral infection [64].

In case of the treatment of Ebola virus, many alkaloids are isolated from Atropa belladonna that gives a positive result and cure of Ebola haemorrhagic fever (Ebola HF) [100, 101], whereas a sulfated polysaccharide, fucoidan isolated from Cladosiphon okamuranus, and sulphated polysaccharide (named kappa carrageenan) from whole plants of Gymnogongrus griffithsiae [94] worked against dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2). Cytarabine and matrine are two important active constituents found in the extract of Gillan's plants such as chuchaq and trshvash, respectively, whereas these compounds have the potentiality of better binding interaction with the receptors and show anti SARS-CoV-2 activity by inhibiting the initiation of viral infection [108].

There are three species of Tephrosia (viz. T. crassifolia, T. madrensis, and T. viridiflora), which can able to produce huge number of flavonoids and show antiviral activity against dengue virus. Among them, glabranine and 7-O-methyl-glabranine isolated from T. madrensis showed strong inhibitory effects on dengue virus replication in LLC-MK2 cells. Interestingly, moderate to low inhibitory effect was observed by methyl-hildgardtol A isolated from T. crassifolia. However, hildgardtol A of T. crassifolia and elongatine of T. viridiflora do not show any inhibitory effect on viral growth [94]. Honokiol (a lignin biphenol) derived from Magnolia tree has antiviral activity against serotype 2 dengue virus (DENV-2). This novel molecule can be able to interfere on the endocytosis of virus to reduce its double-strand RNA, by abrogating the colocalization of DENV envelope proteins. Inhibitory activity of honokiol was proved by suppressing the replication of DENV-2 in baby hamster kidney (BHK) and human hepatocarcinoma Huh7 cells [9, 47].

In the Chinese herbal medicine, extracts of Lonicerae japonicae (Japanese honeysuckle), Flos (ragged-robin), and Fructus forsythia (Lianqiao) are used together as an antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agent. Interestingly, chito-oligosaccharide in combination with herbal mixture can also act as an anti-influenza agent [64].

5. Major Challenges and Future Perspectives

Nowadays, the acceptance of herbal medicines is increasing for many reasons as it is less expensive, with less or null side effects and better patient tolerance. From the past to recent studies, it can be speculated that quality and safety study of plant-derived compounds with medicinal importance is required. Therefore, scientific, accurate, and informative studies are obligatory for any potent compound, which have isolated from plants [21]. About half million plants with medicinal properties are estimated to be present around the world. Surprisingly as well as grievously, most of them are yet not investigated [109]. It is required to give more attention to taxonomic characters and identification of wide range of medicinal plants throughout the world [21]. Various pharmacologically important peptides or proteins obtained from different medicinal plants can be introduced in the production of vaccines and therapeutics. The main challenge in this field of research is the extraction procedure. In this connection after establishment of a compound as a potent therapeutic agent, researchers have to increase its production in both in vitro and ex vitro conditions. This is also very challenging but can be resolved by using sophisticated techniques of recombinant DNA technology, elicitation, etc. [26]. Along with these, identification of biosynthetic pathway of that particular product and application of transgenic approach can be used as feasible way to enhance the production of that particular product. Different scientific approaches can also be taken to identify the newer plant-derived compounds with potential pharmacological activities. This can be considered as an emerging field of scientific research with global profit. Furthermore, it was already expected by [21] that within the year of 2020, the whole market in Asia-Pacific for herbal supplements reached more than US$115 billion and about more than that much turnover happened in 2021, i.e., US$140 billion [21]. It is also explained in the report of Asia Pacific Nutritional Supplements Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report with a report ID of GVR-4-68038-105-4 that it is expected that it will expand about 6.1% at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) starting from 2022 to 2030. So, it is clear that the use of herbal supplements and ethnic medicines are increasing day by day. In the recent days, several RNA interference (RNAi)-based technologies and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas technology have appeared to control viruses. It helps by either directly targeting the viral RNA or DNA or by inactivating plant host susceptibility gene [110]. The CRISPR-Cas system is a technology, which uses in diagnosis of various infectious RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. This is undertaken as a potential technology for its accuracy both in therapeutic and molecular diagnosis [111].

6. Conclusion

Standing in the current circumstance of global pandemic of COVID-19, that causes huge damage of human health and also destroys economic backbone of a country, researchers are constantly trying to find out the way by which mankind will be safe from the fourth or fifth wave of virus onslaught. At this time of high crisis period, we all want something to eradicate or bypass the disease. We reviewed the plant extracts and/or extracted and identified active compounds from the medicinal plants that are useful for prevention of many RNA viral diseases, focusing on plant extracts and phytochemicals that have already reached in clinical trials and having highlighting properties to prevent the viruses. Along with disruption of global health, RNA viruses have immense potential to stop the economic growth of a country. However, for prevention of those diseases and to secure human populations, antiviral drug discovery is needed. Till date, many traditional medicinal plants were reported to have strong antiviral activities. Medicinal plants contain active compounds like alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, tannins, polysaccharides, proteins, and peptides. These compounds can help in the prevention of viral diseases by blocking the virus entry and/or via the inhibition of viral replication at the different stages by regulating the enzyme actions as well and specially without having any known side effects. Finally, the improvement of newly discovered medicinal plant products is vital and required for controlling the constant threats of deadly contagious RNA viruses. This review enlightens some way with lesser hazard to combat in this epidemic era of RNA virus like COVID-19. It is necessary to further examine by highlighting drug delivery system of antiviral phytochemical to reach successfully in their intended site of action.

Contributor Information

Krishnendu Acharya, Email: krish_paper@yahoo.com.

Ram Prasad, Email: ramprasad@mgcub.ac.in.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

Authors' Contributions

Anamika Paul, Krishnendu Acharya, and Ram Prasad are responsible for the conceptualization; Nilanjan Chakraborty, Anuj Ranjan, and Abhishek Chauhan for the investigation, data collection, and resource; Anamika Paul and Anik Sarkar for the formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation; Nilanjan Chakraborty for the writing—review and editing; Shilpi Srivastava, Akhilesh kumar Singh, Iqra Mubeen, and Ashutosh Kumar Rai for the data analysis and editing; Ram Prasad for the writing, review, and editing; and Krishnendu Acharya for the supervision. All authors read the final manuscript. Anamika Paul and Nilanjan Chakraborty contributed equally to this work. All authors agree mutually to the publication of this work.

References

- 1.Carrasco-Hernandez R., Jácome R., López Vidal Y., Ponce de León S. Are RNA viruses candidate agents for the next global pandemic? A review. ILAR Journal . 2017;58(3):343–358. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai W., He L., Zhang X., et al. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cellular & Molecular Immunology . 2020;17(6):613–620. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg R. Detecting the emergence of novel, zoonotic viruses pathogenic to humans. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences . 2015;72(6):1115–1125. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1785-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamid S., Mir M. Y., Rohela G. K. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a pandemic (epidemiology, pathogenesis and potential therapeutics) New microbes and new infections . 2020;35, article 100679 doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afrough B., Dowall S., Hewson R. Emerging viruses and current strategies for vaccine intervention. Clinical and Experimental Immunology . 2019;196(2):157–166. doi: 10.1111/cei.13295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashfaq U. A., Idrees S. Medicinal plants against hepatitis C virus. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG . 2014;20(11):2941–2947. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i11.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogbole O. O., Akinleye T. E., Segun P. A., Faleye T. C., Adeniji A. J. In vitro antiviral activity of twenty-seven medicinal plant extracts from Southwest Nigeria against three serotypes of echoviruses. Virology Journal . 2018;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12985-018-1022-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varga F., Šolić I., Dujaković M. J., Łuczaj Ł., Grdiša M. The first contribution to the ethnobotany of inland Dalmatia: medicinal and wild food plants of the Knin area, Croatia. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae . 2019;88(2) doi: 10.5586/asbp.3622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Shabat S., Yarmolinsky L., Porat D., Dahan A. Antiviral effect of phytochemicals from medicinal plants: applications and drug delivery strategies. Drug Delivery and Translational Research . 2020;10(2):354–367. doi: 10.1007/s13346-019-00691-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embarc-Buh A., Francisco-Velilla R., Martinez-Salas E. RNA-binding proteins at the host-pathogen interface targeting viral regulatory elements. Viruses . 2021;13(6):p. 952. doi: 10.3390/v13060952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilen C. B., Tilton J. C., Doms R. W. HIV: cell binding and entry. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine . 2012;2(8) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science . 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma R. Viral diseases and antiviral activity of some medicinal plants with special reference to Ajmer. Journal of Antivirals & Antiretrovirals . 2019;11(3):p. 183. doi: 10.35248/1948-5964.19.11.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poltronieri P., Sun B., Mallardo M. RNA viruses: RNA roles in pathogenesis, coreplication and viral load. Current Genomics . 2015;16(5):327–335. doi: 10.2174/1389202916666150707160613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez E. L., Lagunoff M. Viral activation of cellular metabolism. Virology . 2015;479-480:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaitanya K. V. Genome and Genomics . Springer; 2019. Structure and organization of virus genomes; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu H., Stratton C. W., Tang Y. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. Journal of Medical Virology . 2020;92(4):401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sofowora A., Ogunbodede E., Onayade A. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention. African journal of traditional, complementary and alternative medicines . 2013;10(5):210–229. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i5.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck J. R. How to evaluate drugs. Journal of the American Medical Association . 1990;264(1):83–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450010087037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mundy L., Pendry B., Rahman M. Antimicrobial resistance and synergy in herbal medicine. Journal of Herbal Medicine . 2016;6(2):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2016.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamshidi-Kia F., Lorigooini Z., Amini-Khoei H. Medicinal plants: past history and future perspective. Journal of herbmed pharmacology . 2018;7(1):1–7. doi: 10.15171/jhp.2018.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganjhu R. K., Mudgal P. P., Maity H., et al. Herbal plants and plant preparations as remedial approach for viral diseases. Virus . 2015;26(4):225–236. doi: 10.1007/s13337-015-0276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henkin J. M., Sydara K., Xayvue M., et al. Revisiting the linkage between ethnomedical use and development of new medicines: a novel plant collection strategy towards the discovery of anticancer agents. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research: Planta Medica . 2017;11(40):621–634. doi: 10.5897/jmpr2017.6485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandhi G. R., Barreto P. G., dos Santos Lima B., et al. Medicinal plants and natural molecules with in vitro and in vivo activity against rotavirus: a systematic review. Phytomedicine . 2016;23(14):1830–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lelešius R., Karpovaitė A., Mickienė R., et al. In vitro antiviral activity of fifteen plant extracts against avian infectious bronchitis virus. BMC Veterinary Research . 2019;15(1):178–210. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1925-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakraborty N., Banerjee A., Sarkar A., Ghosh S., Acharya K. Mushroom polysaccharides: a potent immune-modulator. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry . 2021;11:8915–8930. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salehi B., Kumar N. V. A., Şener B., et al. Medicinal plants used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2018;19(5):p. 1459. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad A., Muthamilarasan M., Prasad M. Synergistic antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2 by plant-based molecules. Plant Cell Reports . 2020;39(9):1109–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00299-020-02560-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farsani M. S., Behbahani M., Isfahani H. Z. The effect of root, shoot and seed extracts of the Iranian Thymus L.(family: Lamiaceae) species on HIV-1 replication and CD4 expression. Cell Journal (Yakhteh) . 2016;18(2):p. 255. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2016.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanna G., Madeddu S., Serra A., et al. Anti-poliovirus activity of Nerium oleander aqueous extract. Natural Product Research . 2021;35(4):633–636. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2019.1582046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sornpet B., Potha T., Tragoolpua Y., Pringproa K. Antiviral activity of five Asian medicinal pant crude extracts against highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine . 2017;10(9):871–876. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahu U., Tiwari S. P., Roy A. Comprehensive notes on anti diabetic potential of medicinal plants and polyherbal formulation. Pharmaceutical and Biosciences Journal . 2015;3(3):57–64. doi: 10.20510/ukjpb/3/i3/89427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh P. K., Rawat P. Evolving herbal formulations in management of dengue fever. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine . 2017;8(3):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sagadevan P., Suresh S. N., Ranjithkumar R., Rathishkumar S., Sathish S., Chandarshekar B. Traditional use of Andrographis paniculata: review and perspectives. International Journal of Biosciences and Nanosciences . 2015;2(5):123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuete V., Ngameni B., Simo C. C. F., et al. Antimicrobial activity of the crude extracts and compounds from Ficus chlamydocarpa and Ficus cordata (Moraceae) Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2008;120(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raka S. C., Rahman A., Kaium M. K. H. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of methanolic extract of Ficus fistulosa leaves: an unexplored phytomedicine. PharmacologyOnline . 2019;1:354–360. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wahyuni T. S., Tumewu L., Permanasari A. A., et al. Antiviral activities of Indonesian medicinal plants in the East Java region against hepatitis C virus. Virology Journal . 2013;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salem M. Z. M., Zayed M. Z., Ali H. M., El-Kareem A., Mamoun S. M. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of extracts from Schinus molle wood branch growing in Egypt. Journal of Wood Science . 2016;62(6):548–561. doi: 10.1007/s10086-016-1583-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdel-Malek S., Bastien J. W., Mahler W. F., et al. Drug leads from the Kallawaya herbalists of Bolivia. 1. Background, rationale, protocol and anti-HIV activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 1996;50(3):157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)01380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alavarce R. A. S., Saldanha L. L., Almeida N. L. M., Porto V. C., Dokkedal A. L., Lara V. S. The beneficial effect of Equisetum giganteum L. against Candida biofilm formation: new approaches to denture stomatitis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2015;2015:9. doi: 10.1155/2015/939625.939625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feitosa I. S., Reinaldo R. C. P., Santiago A. C. P., Albuquerque U. P. “Equisetum giganteum L.” medicinal and aromatic plants of South America . Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verma R. K., Kumari P., Maurya R. K., Kumar V., Verma R. B., Singh R. K. Medicinal properties of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.): a review. International Journal of Chemical Studies . 2018;6(4):1354–1357. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butt A., Butt B. Z., Vehra S. E. Larvicidal potential of Calotropis procera against Aedes aegypti. International Journal of Mosquito Research . 2016;3(5):47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devi S., Gupta C., Jat S. L., Parmar M. S. Crop residue recycling for economic and environmental sustainability: the case of India. Open Agriculture . 2017;2(1):486–494. doi: 10.1515/opag-2017-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasture P. N., Nagabhushan K. H., Kumar A. A multi-centric, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, prospective study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Carica papaya leaf extract, as empirical therapy for thrombocytopenia associated with dengue fever. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India . 2016;64(6):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young-Jung L., Yoot M. L., Chong-Kil L., Jae K., Sang B., Jin T. Therapeutic applications of compounds in the Magnolia family. Pharmacology & therapeutics . 2011;130(2):157–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang C.-Y., Chen S.-J., Wu H.-N., et al. Honokiol, a lignan biphenol derived from the magnolia tree, inhibits dengue virus type 2 infection. Viruses . 2015;7(9):4894–4910. doi: 10.3390/v7092852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nwinyi O. C., Chinedu N. S., Ajani O. O. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of Pisidium guajava and Gongronema latifolium. Journal of medicinal plants research . 2008;2(8):189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patwardhan B. Drug discovery and development: traditional medicine and ethnopharmacology perspectives . SciTopics.(Online); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joshi B., Panda S. K., Jouneghani R. S., et al. Antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anthelmintic activities of medicinal plants of Nepal selected based on ethnobotanical evidence. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2020;2020:14. doi: 10.1155/2020/1043471.1043471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yonesi M., Rezazadeh A. Plants as a Prospective Source of Natural Anti-Viral Compounds and Oral Vaccines against COVID-19 Coronavirus . Preprints; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akkol E. K., Güvenç A., Yesilada E. A comparative study on the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of five Juniperus taxa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2009;125(2):330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zakynthinos G., Varzakas T. Hippophae rhamnoides: safety and nutrition. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science Journal . 2015;3(2):89–97. doi: 10.12944/CRNFSJ.3.2.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sangeetha M. K., Balaji Raghavendran H. R., Gayathri V., Vasanthi H. R. Tinospora cordifolia attenuates oxidative stress and distorted carbohydrate metabolism in experimentally induced type 2 diabetes in rats. Journal of Natural Medicines . 2011;65(3-4):544–550. doi: 10.1007/s11418-011-0538-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lalla J. K., Ogale S., Seth S. A review on dengue and treatments. Research and reviews. Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology . 2014;2(4):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devi S., Kumar D., Kumar M. Ethnobotanical values of antidiabetic plants of MP region India. Journal of medicinal plants studies . 2016;4:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharanya C. S., Sabu A., Haridas M. Potent phytochemicals against COVID-19 infection from phyto-materials used as antivirals in complementary medicines: a review. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2021;7(1):p. 113. doi: 10.1186/s43094-021-00259-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pandey P., Rane J. S., Chatterjee A., et al. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of COVID-19 with naturally occurring phytochemicals: an in silico study for drug development. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2021;39(16):1–11. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1796811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kulkarni S. A., Nagarajan S. K., Ramesh V., Palaniyandi V., Selvam S. P., Madhavan T. Computational evaluation of major components from plant essential oils as potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Journal of Molecular Structure . 2020;1221, article 128823 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bailly C., Vergoten G. Glycyrrhizin: an alternative drug for the treatment of COVID-19 infection and the associated respiratory syndrome? Pharmacology & Therapeutics . 2020;214(107618, article 107618) doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu R., Chen L., Lan R., Shen R., Li P. Computational screening of antagonists against the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) coronavirus by molecular docking. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents . 2020;56(2, article 106012) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Basu A., Sarkar A., Maulik U. Molecular docking study of potential phytochemicals and their effects on the complex of SARS-CoV2 spike protein and human ACE2. Scientific Reports . 2020;10(1, article 17699) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Enmozhi S. K., Raja K., Sebastine I., Joseph J. Andrographolide as a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: an in silico approach. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2020;39(9):1–7. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1760136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shree P., Mishra P., Selvaraj C., et al. Targeting COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease through active phytochemicals of ayurvedic medicinal plants – Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha), Tinospora cordifolia (Giloy) and Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) – a molecular docking study. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2022;40(1):190–203. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1810778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhardwaj V. K., Singh R., Sharma J., Rajendran V., Purohit R., Kumar S. Identification of bioactive molecules from tea plant as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2021;39(10):1–10. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1766572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang L., Yuen T. T. T., Ye Z., et al. Berbamine inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection by compromising TRPMLs-mediated endolysosomal trafficking of ACE2. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy . 2021;6(1):p. 168. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clarke E. C., Nofchissey R. A., Ye C., Bradfute S. B. The iminosugars celgosivir, castanospermine and UV-4 inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication. Glycobiology . 2021;31(4):378–384. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwaa091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jo S., Kim H., Kim S., Shin D. H., Kim M. Characteristics of flavonoids as potent MERS-CoV 3C-like protease inhibitors. Chemical Biology & Drug Design . 2019;94(6):2023–2030. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park J.-Y., Yuk H. J., Ryu H. W., et al. Evaluation of polyphenols from Broussonetia papyrifera as coronavirus protease inhibitors. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry . 2017;32(1):504–512. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1265519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mani J. S., Johnson J. B., Steel J. C., et al. Natural product-derived phytochemicals as potential agents against coronaviruses: a review. Virus Research . 2020;284, article 197989 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Balkrishna A., Gupta A. K., Gupta A., et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of an ayurvedic formulation Khadirarishta. Journal of Herbal Medicine . 2022;32, article 100509 doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2021.100509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takshak S., Agrawal S. B. Defense potential of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants under UV-B stress. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology . 2019;193:51–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gómez-Calderón C., Mesa-Castro C., Robledo S., et al. Antiviral effect of compounds derived from the seeds of Mammea americana and Tabernaemontana cymosa on Dengue and Chikungunya virus infections. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2017;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1562-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Min N., Leong P. T., Lee R. C. H., Khuan J. S. E., Chu J. J. H. A flavonoid compound library screen revealed potent antiviral activity of plant-derived flavonoids on human enterovirus A71 replication. Antiviral Research . 2018;150:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chung C.-Y., Liu C.-H., Burnouf T., et al. Activity-based and fraction-guided analysis of Phyllanthus urinaria identifies loliolide as a potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus entry. Antiviral Research . 2016;130:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghildiyal R., Prakash V., Chaudhary V. K., Gupta V., Gabrani R. Plant-derived bioactives . Springer; 2020. Phytochemicals as antiviral agents: recent updates; pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fan W., Qian S., Qian P., Li X. Antiviral activity of luteolin against Japanese encephalitis virus. Virus Research . 2016;220:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Le Lee J., Loe M. W. C., Lee R. C. H., Chu J. J. H. Antiviral activity of pinocembrin against Zika virus replication. Antiviral Research . 2019;167:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rohini M. V., Padmini E. Preliminary phytochemical screening of selected medicinal plants of polyherbal formulation. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry . 2016;5(5):p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Galochkina A. V., Anikin V. B., Babkin V. A., Ostrouhova L. A., Zarubaev V. V. Virus-inhibiting activity of dihydroquercetin, a flavonoid from Larix sibirica, against coxsackievirus B4 in a model of viral pancreatitis. Archives of Virology . 2016;161(4):929–938. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ohemu T. L., Agunu A., Chollom S. C., Okwori V. A., Dalen D. G., Olotu P. N. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening and Antiviral Potential of Methanol Stem Bark Extract of Enantia Chlorantha Oliver (Annonaceae) and Boswellia Dalzielii Hutch (Burseraceae) against Newcastle Disease in Ovo. European Journal of Medicinal Plants . 2018;25(4):1–8. doi: 10.9734/EJMP/2018/44919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kazakova O. B., Smirnova I. E., Baltina L. A., Boreko E. I., Savinova O. V., Pokrovskii A. G. Antiviral activity of acyl derivatives of betulin and betulinic and dihydroquinopimaric acids. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry . 2018;44(6):740–744. doi: 10.1134/S1068162018050059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.LeCher J. C., Diep N., Krug P. W., Hilliard J. K. Genistein has antiviral activity against herpes B virus and acts synergistically with antiviral treatments to reduce effective dose. Viruses . 2019;11(6):p. 499. doi: 10.3390/v11060499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hui Q. X., Lw Y. Y. D. H. E., Zhang S. Extraction of total lignans from Radix isatidis and its ant-RSV virus effect. Clinical Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics . 2019;1(1):p. 1005. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hu Y., Chen W., Shen Y., Zhu B., Wang G.-X. Synthesis and antiviral activity of coumarin derivatives against infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters . 2019;29(14):1749–1755. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li C., Wei Q., Zou Z.-H., et al. A lignan and a lignan derivative from the fruit of Forsythia suspensa. Phytochemistry Letters . 2019;32:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2019.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chernyshov V. V., Yarovaya O. I., Fadeev D. S., et al. Single-stage synthesis of heterocyclic alkaloid-like compounds from (+)-camphoric acid and their antiviral activity. Molecular Diversity . 2020;24(1):61–67. doi: 10.1007/s11030-019-09932-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mourya D. T., Yadav P. D., Ullas P. T., et al. Emerging/re-emerging viral diseases & new viruses on the Indian horizon. The Indian Journal of Medical Research . 2019;149(4):447–467. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1239_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chattopadhyay D., Mukherjee H., Bag P., Ghosh S., Samanta A., Chakrabarti S. Ethnomedicines in antiviral drug discovery. International Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2009;3(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lung J., Lin Y. S., Yang Y. H. La estructura química potencial de la ARN polimerasa dependiente de ARN anti-SARS-CoV-2. Revista chilena de infectología . 2020;92(6):693–697. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wintachai P., Kaur P., Lee R. C. H., et al. Activity of andrographolide against chikungunya virus infection. Scientific Reports . 2015;5(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bringmann G., Steinert C., Feineis D., Mudogo V., Betzin J., Scheller C. HIV-inhibitory michellamine-type dimeric naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from the Central African liana Ancistrocladus congolensis. Phytochemistry . 2016;128:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin L. T., Hsu W. C., Lin C. C. Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine . 2014;4(1):24–35. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.124335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abd Kadir S. L., Yaakob H., Mohamed Zulkifli R. Potential anti-dengue medicinal plants: a review. Journal of Natural Medicines . 2013;67(4):677–689. doi: 10.1007/s11418-013-0767-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang Y., Yang P., Huang C., et al. Inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2 infection of neferine by blocking Ca2+-dependent membrane fusion. Journal of Medical Virology . 2021;93(10):5825–5832. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.He C. L., Huang L. Y., Wang K., et al. Identification of bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids as SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors from a library of natural products. Signal transduction and targeted therapy . 2021;6(1):p. 131. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00531-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]