Abstract

The Tri5 gene encodes trichodiene synthase, which catalyzes the first reaction in the trichothecene biosynthetic pathway. In vitro, a direct relationship was observed between Tri5 expression and the increase in deoxynivalenol production over time. We developed a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay to quantify Tri5 gene expression in trichothecene-producing strains of Fusarium species. We observed an increase in Tri5 expression following treatment of Fusarium culmorum with fungicides, and we also observed an inverse relationship between Tri5 expression and biomass, as measured by β-d-glucuronidase activity, during colonization of wheat (cv. Avalon) seedlings by F. culmorum. RT-PCR analysis also showed that for ears of wheat cv. Avalon inoculated with F. culmorum, there were different levels of Tri5 expression in grain and chaff at later growth stages. We used the Tri5-specific primers to develop a PCR assay to detect trichothecene-producing Fusarium species in infected plant material.

Several Fusarium species, including the small-grain cereal pathogens Fusarium culmorum, Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph, Gibberella zeae), Fusarium poae, Fusarium crookwellense, Fusarium sporotrichoides, and Fusarium sambucinum (teleomorph, Gibberella pulicaris), produce trichothecene mycotoxins (4). Trichothecenes are sesquiterpene epoxides which inhibit eukaryotic protein synthesis and occur naturally in Fusarium-infected cereal grains (16, 26). Contamination with these compounds results in serious economic losses (21) and has been linked to mycotoxicosis of both humans and animals (14).

Trichothecenes may play an important role in the aggressiveness of fungi towards plant hosts (3, 5, 24). However, few investigations have focused on the production of trichothecenes in planta, and little is known about the factors that influence regulation of this pathway. The effect of fungicides on trichothecene production by Fusarium species is not clear. There have been reports that fungicides reduce both Fusarium head blight and the trichothecene content (generally, the deoxynivalenol [DON] content) of grain (2, 31); in other instances fungicides have reduced disease levels or toxin levels but not both (2, 19). In at least one case, fungicide treatment was associated with increased levels of nivalenol in infected cereal grains (9).

Our long-term goal is to use gene expression studies to better understand regulation of the trichothecene biosynthetic pathway. Tri5 encodes trichodiene synthase (4), which catalyzes the first step in the trichothecene biosynthetic pathway, the isomerization and cyclization of farnesyl pyrophosphate to trichodiene (11). Northern blot analysis was used previously to study Tri5 gene expression in vitro (12), but this method is not sensitive enough for in planta studies.

Our objectives in this study were (i) to develop a Tri5-specific reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay to detect and quantify Tri5 gene expression, (ii) to investigate the relationship between Tri5 expression and trichothecene (DON) production by F. culmorum, (iii) to measure the in vitro effect of fungicides on Tri5 gene expression, (iv) to determine the relationship between fungal biomass and Tri5 expression during pathogenesis, and (v) to determine if Tri5 is differentially expressed in F. culmorum when growing on grain or chaff. Our results increased our understanding of the effects of different host tissues and chemical control agents on trichothecene production and further elucidated the role of Tri5 expression and trichothecene production by phytopathogenic Fusarium species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal and plant material.

Isolates of Fusarium species were obtained from the John Innes Centre facultative pathogen culture collection (Table 1). The culture media, maintenance conditions, and methods used to produce conidial inocula have been described previously (7). Wheat plants (cv. Avalon) grown in 1-liter pots in John Innes compost no. 2 in an unheated glasshouse were inoculated at midanthesis with F. culmorum, F. poae, or F. graminearum (7) (Table 1) and were harvested at growth stage (GS) 90 (32). F. culmorum β-d-glucuronidase (GUS) transformant G514 (which constitutively expresses GUS) was used as the inoculum for both an in vitro experiment and a seedling experiment.

TABLE 1.

Designations and origins of fungal isolates

| Taxon | Strain(s)a | Origin | Tri5b |

|---|---|---|---|

| F. culmorum | Fu 3, Fu 5, Fu 15, Fu 42, Fu 60 | United Kingdom | + |

| F 77, F 200, F 400 | France | + | |

| F. graminearum | F 86, F 500, F 508, F 604, F 700, F 740 | France | + |

| GZ 3639 | United States | + | |

| F. poae | Fu 53, F 18, CSL8, 4/3084, 4/3155, 4/4343 | United Kingdom | + |

| F 62 | Poland | + | |

| F. crookwellwense | C 108, C 233, C 581, C 582, C 804, C 1160 | Poland | + |

| F. sambucinum | F 64, F 133 | France | + |

| F 108, F 111 | Poland | + | |

| F 153 | Germany | + | |

| F. sporotrichioides | F 95 | Poland | + |

| F 627 | France | + | |

| F. avenaceum | Fu 17, 96UKR2, 239 | United Kingdom | − |

| 76-1, 78-1 | Canada | − | |

| FARS41.1 | France | − | |

| F. tricinctum | F 308, F 402 | France | − |

| G. fujikuroi (F. moniliforme) | A3733 (mating population A), B3853 (mating population B), C53, C93, C95 (mating population C), D3736, C95 (mating population D) | United States | − |

The following strains were used to test the specificity of Tri5 PCR primers Tri5F and Tri5R: F. culmorum Fu 5, Fu 15, Fu 42, F 77, F 200, and F 400; F. graminearum F 86, F 500, F 508, F 604, F 700, F 740, and GZ 3639; F. poae Fu 53, CSL8, 4/3084, 4/3155, 4/4343, and F 62; F. crookwellwense C 108, C 223, C 581, C 582, C 804, and C 1160; F. sambucinum F 64, F 133, F 108, F 111, and F 153; F. sporotrichioides F 95 and F 627; F. avenaceum Fu 17, 96UKR2, 239, 76-1, 78-1, and FARS41.1; F. tricinctum F 308 and F 402; and G. fujikuroi A3733, B3853, C53, C93, C95 (mating population C), D3736, and C95 (mating population D). The following strains were used to inoculate wheat ears in glasshouse trials: F. culmorum Fu 3, Fu 15, Fu 42, and Fu 60; F. graminearum GZ 3639; and F. poae Fu 53, F 18, and CSL8. The following isolates were used to test the RT-PCR assay: F. culmorum Fu 5, Fu 42, and F 400; F. graminearum F 500 and F 700; F. poae F 62; and F. sporotrichioides F 95.

Determined by the Tri5-specific PCR. +, PCR amplification product detected; −, no product detected.

DNA and RNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from fungal cultures, grain, and whole wheat ears (7). Total RNA was extracted (18) and was quantified spectrophotometrically by determining the optical density at 260 nm. RNA (20 μg) was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Pharmacia Biotech, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) (27), resuspended in 30 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, and stored at −20°C.

Primer design.

Primers for Tri5 (primer Tr5F [5′-AGCGACTACAGGCTTCCCTC-3′] and primer Tr5R [5′-AAACCATCCAGTTCTCCATCTG-3′]) were derived from conserved regions of Tri5 in F. culmorum (30), F. graminearum (24), F. poae (8), F. sporotrichioides (11), and F. sambucinum (12). The following three β-tubulin primers were used: forward β-tubulin primer BT2a (10); reverse β-tubulin primer Bt2b (10); and reverse primer B531R (5′-GACTGACCGAAAACGAAGTTG-3′), which was derived from a region conserved in the G. pulicaris β-tubulin gene (tub2) (GenBank accession no. U27303) and a Neurospora crassa benomyl-resistant mutant (23).

Tri5 PCR analysis.

Tri5 primers Tr5F and Tr5R were tested with a range of Fusarium species (Table 1) and also with DNA extracts from wheat ears and grain inoculated with F. culmorum, F. graminearum, or F. poae. An approximately 544-bp fragment was expected for Tr5F-Tr5R genomic DNA PCR amplification. The reaction mixtures contained 10 μg of fungal DNA or the DNA from 0.8 mg (dry weight) of plant material. The PCR negative control reaction mixtures contained no DNA. The PCR reaction mixtures (7) contained 10 pmol of each of the Tri5-specific primers (Tr5F and Tr5R). The program used included 30 cycles consisting of 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 45 s; the fastest possible transition between temperatures was used.

Development of Tri5-specific RT-PCR assay.

GYEP medium (100 ml) (11) was inoculated with an F. culmorum Fu 42 conidial suspension to a final concentration of 5 × 104 conidia per ml. Flasks were incubated at 25°C and 150 rpm and were harvested 24, 36, 48, and 96 h postinoculation (two flasks per time point), and RNA extracts were used to develop a Tri5 RT-PCR assay. RT was performed as described previously (25), except that the reaction mixtures contained 1 μg of total RNA, 100 U of Superscript reverse transcriptase (GibcoBRL, Paisley, United Kingdom), and 0.5 μg of oligo(dT) (GibcoBRL), 0.5 μg of random hexamers (GibcoBRL), or 34 pmol of primer Tr5R and were incubated at 42°C for 30 min. The RT reaction mixtures were diluted to a volume of 100 μl with sterile distilled H2O, and 10 μl of each mixture was used for Tri5-specific PCR amplification as described above, except for an initial 3 min of incubation at 95°C. RT-PCR control reaction mixtures contained either water or 10 ng of F. culmorum Fu 42 DNA. Because Tr5F and Tr5R flank a 59-bp intron within the Tri5 gene of F. culmorum (28), the expected product size for the RT-PCR analysis of RNA was smaller (485 bp) than the expected product size for the RT-PCR analysis of genomic DNA (544 bp). The assay was tested with a range of Fusarium species (Table 1), RNA extracts of which were obtained from GYEP medium cultures inoculated with three 7-day-old 8-mm mycelial plugs and harvested 2 days postinoculation. This RT-PCR assay was also used to detect Tri5 gene expression in in vitro and in planta experiments.

Development and use of quantitative Tri5-specific RT-PCR assays.

RT was performed as described above by using primer Tr5R and either primer Bt2b or primer B531R. PCR amplification was performed as described above by using 10 pmol of Tr5F, 10 pmol of Tr5R, and either 10 pmol of Bt2a and Bt2b or 10 pmol of Bt2a plus 10 pmol of B531R and an annealing temperature of 60°C. The coamplification assay was tested with a range of Fusarium species (Table 1). Constitutive expression of β-tubulin was tested by using RNA extracts from F. culmorum GUS transformant G514 GYEP medium cultures (25 ml) inoculated with conidia, incubated as described above, and harvested 24, 48, 72, and 96 h postinoculation. Aliquots (10 μl) of the Tri5–β-tubulin RT products were coamplified with serial dilutions of F. culmorum Fu 5 genomic DNA (5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 ng) in β-tubulin-specific PCR assays. Following separation by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%, [wt/vol] agarose), all quantitative RT-PCR products were analyzed by using Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The ratios of cDNA to genomic DNA allowed us to determine the relative amounts of β-tubulin mRNA present in the original RNA extracts (nanogram of mRNA per nanogram of genomic DNA).

A quantitative Tri5 RT-PCR was used to study F. culmorum Tri5 expression in vitro and in planta (except that the reaction mixtures contained 2 μg of total RNA for in planta experiments). The ratio of Tri5 to β-tubulin PCR products was determined within the linear range of coamplification (i.e., by using 10 μl of RT products), and this ratio was used as an index of the relative Tri5 expression in samples (nanograms of Tri5 mRNA per nanogram of β-tubulin mRNA). All RT-PCR were performed at least twice.

Relationship between DON production and Tri5 expression.

GYEP medium cultures (25 ml), that were inoculated with F. culmorum GUS transformant G514 conidia and incubated as described above were harvested 24, 48, 72, and 96 h postinoculation. The mycelium was harvested, the RNA was extracted, and a Tri5 quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed as described above. Aliquots (2 ml) of the supernatants were extracted with 3 volumes of ethyl acetate, vacuum dried, and resuspended in 2 ml of methanol. Extracts were diluted in 10% (vol/vol) methanol to obtain the appropriate DON concentration, which was quantified by using a RIDASCREEN FAST enzyme immunoassay kit (R-Biopharm GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Fungicide experiment.

GYEP medium cultures (100 ml) were inoculated with F. culmorum Fu 42 conidia and incubated as described above. After 24 h, the fungicides prochloraz (Agrevo, Hauxton, United Kingdom) and tebuconazole (Bayer, Bury St. Edmunds, United Kingdom) were added at concentrations of 2 and 8 μg of active ingredient ml of medium−1. Water was added to control cultures. Two flasks per treatment were harvested 36 h postinoculation. The mycelia were freeze-dried and stored at −70°C.

Seedling experiment.

Nine wheat (cv. Avalon) seedlings per pot were grown at 20°C in plant propagators containing John Innes compost no. 1. After 10 days, 2-cm sterile silicon tubing collars were placed around stem bases, and the plants were inoculated with 300 μl of F. culmorum GUS transformant G514 (6) (5 × 105 conidia per ml of 1% Bacto Agar [Difco]) or with 1% Bacto Agar. The plants were covered until they were harvested to maintain high humidity. AT 10, 17, 24, 27, and 41 days postinoculation, 10 pots were harvested per treatment (corresponding to the second, third, fourth, fourth, and fifth leaves unfolded, respectively). Stem base sections (4 cm) from each pot were combined, and five samples per treatment were used to analyze GUS activity, as described previously (6); in addition, five samples were freeze-dried and stored at −70°C for RT-PCR analysis.

Head blight experiment.

Ears from wheat plants (cv. Avalon) that were cultivated and inoculated with F. culmorum Fu 42 were harvested at either GS 70 (watery ripe grain) or GS 80 (late milky ripe grain) (four ears per harvest), separated into grain, chaff, and rachis components, freeze-dried, and stored at −70°C.

Statistical analysis.

The significance of the differences observed between both the RT-PCR and the GUS activity results within experiments was tested with the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (29) at the 5% level of significance. This test was performed by using Minitab, release 10.1 (Minitab Inc.).

RESULTS

Tri5-specific PCR analysis.

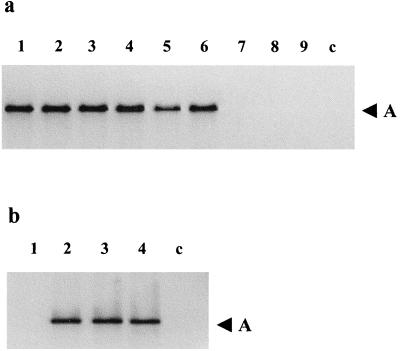

Primers Tr5F and Tr5R amplified a single 544-bp fragment (Fig. 1a) from genomic DNA extracts of F. culmorum, F. graminearum, F. poae, F. sambucinum, F. sporotrichioides, and F. crookwellense isolates but not from Gibberella fujikuroi, Fusarium tricinctum, or Fusarium avenaceum isolates (Table 1). Tri5-specific PCR also detected a single 544-bp fragment in DNA extracts of wheat ears and grain from F. culmorum-, F. graminearum-, and F. poae-inoculated plants (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

Detection of the Tri5 PCR signal in DNA extracts from various Fusarium species (a) and from Fusarium-infected wheat (cv. Avalon) ears and grains (b). (a) Lanes 1 through 9, F. culmorum Fu 3, F. graminearum GZ 3639, F. poae F 62, F. crookwellense C 108, F. sporotrichioides F 95, F. sambucinum F 64, F. avenaceum 76-1, F. tricinctum F 308, and G. fujikuroi A3733, respectively. (b) Lane 1 uninoculated wheat ears; lane 2, wheat ears inoculated with F. culmorum Fu 3, Fu 15, Fu 42, and Fu 60; lane 3, wheat ears inoculated with F. graminearum GZ 3639; lane 4, wheat ears inoculated with F. poae Fu 53, F 18, and CSL8. Lanes c contained a negative PCR control reaction mixture (no DNA added). The arrowheads indicate the position of the 544-bp Tri5 genomic DNA PCR product.

Tri5-specific qualitative RT-PCR analysis.

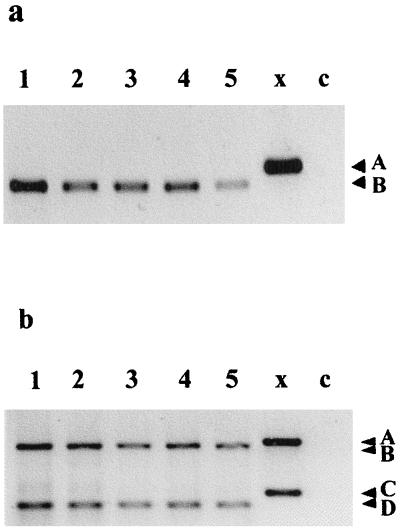

Tri5 expression was detected in GYEP medium-grown F. culmorum at all time points examined (24, 36, 48, and 96 h postinoculation). Following Tri5-specific RT-PCR amplification of F. culmorum DNA, a single amplification fragment of the expected size (485 bp) was detected with cDNA synthesized by using Tr5R (Fig. 2a, lane 1). Higher concentrations of Tri5 cDNA and more specific amplification occurred when primer Tr5R was used for RT instead of oligod(T) or random hexamers (results not shown). This Tri5-specific RT-PCR assay was tested with RNA extracts obtained from GYEP medium cultures of a range of Fusarium species (Fig. 2a), and only a single band at 485 bp was detected.

FIG. 2.

Development of Tri5- and Tri5–β-tubulin-specific RT-PCR assays: Tri5 RT-PCR analysis (a) and Tri5–β-tubulin RT-PCR analysis (b) of various Fusarium species grown in GYEP medium for 48 h. Lanes 1 through 5, mRNA (10 μl) from F. culmorum Fu 3, F. graminearum GZ 3639, F. poae F 62, F. sambucinum F 64, and F. sporotrichioides F 95, respectively; lanes x, F. culmorum genomic DNA; lanes c, negative control. Arrowheads A, B, C, and D indicate the positions of 544-bp Tri5 genomic DNA, 485-bp Tri5 RNA, 286-bp β-tubulin genomic DNA, and 244-bp β-tubulin RNA RT-PCR products, respectively.

Tri5-specific quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

In the quantitative RT-PCR analysis, inclusion of primer Bt2b in Tri5 RT reaction mixtures resulted in generation of multiple products (≤150 bp) in addition to the products expected following Tri5–β-tubulin PCR (485 and 244 bp). Inclusion of B531R in Tri5 RT reaction mixtures resulted in amplification of only products of the expected sizes (Fig. 2b). Quantification of β-tubulin expression in RNA extracts obtained in a GYEP medium time course experiment in which genomic DNA was used as a competitor template showed that β-tubulin expression was constant over time (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

β-Tubulin expression, Tri5 expression, and DON production over time in GYEP medium

| Harvest time (h postinoculation) | β-Tubulin expression (ng of mRNA/ng of genomic DNA) | Tri5 expression (ng of mRNA/ng of β-tubulin mRNA) | DON production (ppm/24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 4.4 ± 0.13a | 0.68 ± 0.02a | 25 ± 12a |

| 48 | 4.5 ± 0.09 | 0.81 ± 0.03 | 47 ± 3 |

| 72 | 4.3 ± 0.21 | 1.2 ± 0.04 | 1,700 ± 23 |

| 96 | 4.4 ± 0.34 | 1.1 ± 0.10 | 1,500 ± 270 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

Relationship between DON production and Tri5 expression.

Tri5 expression in GYEP medium at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h postinoculation was quantified relative to expression of β-tubulin, and the DON contents of culture supernatants were determined (Table 2). We observed that there was a direct power relationship between Tri5 expression and DON content (R2 = 0.95; y = 408x7.91).

In vitro effect of fungicides on Tri5 expression.

At 36 h postinoculation (12 h after fungicides were added) the Tri5/β-tubulin RT-PCR product ratios for cultures amended with 2 and 8 μg of the prochloraz active ingredient ml−1 were 0.93 and 1.11, respectively. The ratios for tebuconazole were 0.93 and 1.14, respectively. These values were significantly higher than the values obtained for control cultures (0.69) but were not significantly different from one another.

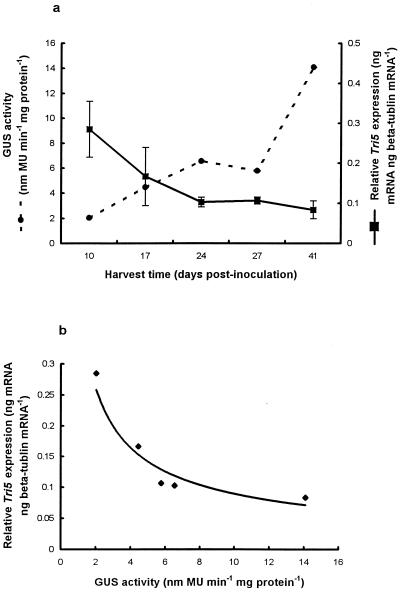

GUS activity and Tri5 expression during colonization of seedlings.

We determined the relationship between active fungal biomass, as measured by GUS activity (we assumed that GUS was constitutively expressed in planta), and Tri5 expression during colonization of wheat seedlings by F. culmorum GUS transformant G514 (Fig. 3). GUS activity (expressed in nanomoles of methylumbelliferone per minute per milligram of protein) generally increased from 10 to 41 days postinoculation and was highest in samples harvested 41 days postinoculation (Fig. 3a). Negligible GUS activity (≤0.8 nmol/min−1/mg−1) was detected in uninoculated samples.

FIG. 3.

(a) GUS activity and relative Tri5 gene expression during pathogenesis of F. culmorum GUS transformant G514 on inoculated wheat (cv. Avalon) seedlings. (b) Relationship between GUS activity and Tri5 expression. MU, methylumbelliferone.

We detected Tri5 mRNA in extracts obtained from most of the inoculated seedlings (Fig. 3a) but not in any of the extracts obtained from uninoculated seedlings. Unlike the results of the in vitro fungicide experiment, we detected two bands for β-tubulin in 95% of the samples (results not shown). Tri5 was quantified relative to the 244-bp β-tubulin product. The levels of Tri5 expression (nanograms of Tri5 mRNA per nanogram of β-tubulin mRNA) decreased from 10 to 17 to 24 days postinoculation, while the levels of expression were similar for samples harvested 24, 27, and 41 days postinoculation (Fig. 3a). When the mean GUS activity was plotted against mean Tri5 expression, an inverse power relationship was observed (R2 = 0.9), with Tri5 expression decreasing as GUS activity increased (y = 0.415x−0.67) (Fig. 3b).

Tri5 expression during colonization of wheat ears.

The level of Tri5 expression in colonized wheat kernels was generally lower than the level of Tri5 expression observed during colonization of seedlings, and Tri5–β-tubulin coamplification was not always possible. Therefore, Tri5 expression and β-tubulin expression were quantified separately relative to genomic DNA. Aliquots (10 μl) of the Tri5–β-tubulin RT products were coamplified with serial dilutions of F. culmorum Fu 5 genomic DNA (1, 5, 10, 15, and 25 ng of genomic DNA for Tri5 and 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 ng of genomic DNA for β-tubulin) in separate Tri5- and β-tubulin-specific PCR assays. This allowed us to determine the amounts of Tri5 and β-tubulin mRNA in the RNA extracts relative to the amount of genomic DNA (nanograms of mRNA per nanogram of genomic DNA). The amount of Tri5 mRNA was then expressed relative to the amount of β-tubulin mRNA (nanograms of Tri5 mRNA per nanogram of β-tubulin mRNA). We determined the mean levels of Tri5 expression in both grain and chaff. At GS 70, the level of Tri5 expression was significantly higher in chaff (0.08) than in grain (0.03). No Tri5 expression was detected in grain at GS 80, while the level in chaff (0.08) was similar to the level detected at GS 70.

DISCUSSION

We developed a RT-PCR assay for detection and quantification of Tri5 gene expression relative to expression of β-tubulin, which has been used previously as a measure of mRNA extraction efficiency (1) and fungal biomass (17). We showed that β-tubulin expression in vitro was constitutive and constant over time. However, it is difficult to assess β-tubulin expression in planta, where it may be influenced by environmental factors. The β-tubulin and Tri5 primer sets both flanked introns within the respective genes, which allowed size differentiation of amplified genomic DNA and mRNA. Unlike the results of the other experiments, two PCR products were generally detected for β-tubulin in the RNA extracts obtained from F. culmorum-inoculated wheat seedlings. The second β-tubulin product may have been due to contamination of seedlings by an unknown fungus, or it may have been due to processing of transcripts. In a study of virulence gene expression in Cochliobolus carbonum during conidial germination (15), the two products detected following β-tubulin-specific RT-PCR were presumed to be due to the splicing out of introns between the primers. In our study, only a single β-tubulin product was detected for in vitro cultures and ear tissue, suggesting that splicing was not the cause of the second product.

Both Tri5 and β-tubulin mRNA coamplification and independent amplification systems for RT-PCR quantification were used in the present work. Independent amplification is necessary when the target gene is expressed at low levels compared to expression of the endogenous control genes, as in our head blight experiment. Our quantitative Tri5 RT-PCR assay was based on PCR coamplification of an external competitor template (genomic DNA) and the Tri5 cDNA target sequence, two sequences which compete for the same primers. β-Tubulin, quantified in a similar manner, was used to normalize the Tri5 expression results and thus accounted for any variability arising from the RNA quantification or RT step. Similar assays have been used to analyze gene expression in other fungi (1, 17).

In vitro, expression of Tri5 in F. culmorum was increased by the fungicides prochloraz and tebuconazole. These compounds were studied because previous work (9, 13) showed that both them reduced Fusarium head blight of wheat caused by F. culmorum. Further work is required to establish the effects of different doses of these fungicides on Tri5 gene expression and toxin accumulation.

GUS activity was used to measure active fungal biomass in seedlings. Previous work in our laboratory has shown that GUS expression in GYEP liquid medium cultures is constant per unit of biomass for 48 h (unpublished data). Maximal Tri5 expression in the Fusarium-susceptible wheat cultivar Avalon occurred 10 days postinoculation, while GUS activity was maximal at 41 days postinoculation, at which time Tri5 expression was relatively low. The inverse relationship observed between GUS activity and Tri5 expression and the early induction of Tri5 expression support the hypothesis that trichothecenes play an important role in the initial establishment of the pathogen in host tissue. Indeed, disruption of Tri5 in F. graminearum significantly reduces the aggressiveness of the fungus towards seedlings and ears of wheat under both growth chamber and field conditions (5, 24).

Following inoculation of wheat ears with F. culmorum at the midanthesis stage, higher levels of Tri5 expression were detected in chaff than in grain at both GS 70 and GS 80. The higher levels of Tri5 expression in chaff may be related to the unfavorable nature of chaff as a substrate. Miller et al. (20) showed that stressful conditions favor trichothecene production by F. graminearum. The results of our head blight experiment are consistent with the results of Snijders and Krechting (30), who found that for a Fusarium-susceptible wheat genotype, the amounts of DON detected in chaff were similar at 28 and 56 days postinoculation (midanthesis), whereas the amount of DON detected in grain decreased from day 28 to day 56.

In the course of this work we developed a Tri5-specific PCR assay for detection of potential trichothecene-producing Fusarium species both in vitro and in planta. A Tri5-specific PCR assay has been described previously and has been used to detect trichothecene-producing Fusarium species in contaminated wheat malt samples (22). The Tri5 PCR assays could provide a screening tool for detection of trichothecene-producing Fusarium species in plant tissue.

Overall, this work showed that the level of Tri5 expression and, therefore, the level of trichothecene production appear to be dependent on the host tissue type and can be significantly influenced by factors such as fungicide treatment. In the future, RT-PCR assays should allow workers to perform more detailed investigations of the factors that affect and regulate Tri5 gene expression in trichothecene-producing Fusarium species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F.M.D. was supported by AgrEvo U.K. Ltd. The work of the Cereals Department is supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogan B W, Schoenike B, Lamar R T, Cullen D. Mangenese peroxidase mRNA and enzyme activity levels during bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-contaminated soil with Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2381–2386. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2381-2386.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyacioglu D, Hettiarachchy N S, Stack R W. Effects of three systemic fungicides on deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin) production by Fusarium graminearum in wheat. Can J Plant Sci. 1992;72:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desjardins A E, Hohn T M, McCormick S. Effect of gene disruption of trichodiene synthase on the virulence of Gibberella pulicaris. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1992;5:214–222. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-5-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desjardins A E, Hohn T M, McCormick S P. Trichothecene biosynthesis in Fusarium species: chemistry, genetics, and significance. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:595–604. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.595-604.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desjardins A E, Proctor R H, Bai G, McCormick S P, Shaner G, Buechley G, Hohn T M. Reduced virulence of trichothecene-nonproducing mutants of Gibberella zeae in wheat field tests. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1996;9:775–781. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doohan F M, Smith P, Parry D W, Nicholson P. Transformation of Fusarium culmorum with the β-d-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene: a system for studying host-pathogen relationships and disease control. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1998;53:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doohan F M, Parry D W, Nicholson P. Fusarium ear blight of wheat: the use of quantitative PCR and visual disease assessment in studies of disease control. Plant Pathol. 1999;48:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fekete C, Logrieco A, Giczey G, Hornok L. Screening of fungi for the presence of the trichodiene synthase encoding sequence by hybridization to the Tri5 gene cloned from Fusarium poae. Mycopathologia. 1997;138:91–97. doi: 10.1023/a:1006882704594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gareis M, Ceynowa J. The influence of the new fungicide Matador (Tebuconazole-Triademol) on mycotoxin production by Fusarium culmorum. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1994;198:244–248. doi: 10.1007/BF01192603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass N L, Donaldson G C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplified conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1323–1330. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1323-1330.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohn T M, Beremand P D. Isolation and nucleotide sequence of sesquiterpene cyclase gene from the trichothecene-producing fungus Fusarium sporotrichioides. Gene. 1989;79:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohn T M, Desjardins A E, McCormick S P. Analysis of Tox5 gene expression in Gibberella pulicaris strains with different trichothecene production phenotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2359–2363. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2359-2363.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutcheon J A, Jordan V W L. Proceeding of the BCPC—Pests and Diseases, 1992. Vol. 2. Farnham, United Kingdom: Brighton Crop Protection Conference Publication; 1992. Fungicide timing and performance for Fusarium control in wheat; pp. 633–638. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joffe A. Fusarium poae and Fusarium sporotrichioides as principal causes of alimentary toxic aleukia. In: Wyllie T D, Morehouse L G, editors. Handbook of mycotoxins and mycotoxicosis. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1978. pp. 21–86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones M J, Dunkle L D. Virulence gene expression during conidial germination in Cochliobolus carbonum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:476–479. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacey J. Mycotoxins in U. K. cereals and their control. Aspects Appl Biol. 1990;25:395–405. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamar R T, Schoenike B, Vanden Wymelenberg A, Stewart P, Dietrich D M, Cullen D. Quantitation of fungal mRNAs in complex substrates by reverse transcription PCR and its application to Phanerochaete chrysosporium-colonized soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2122–2126. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2122-2126.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logemann J, Schell J, Willmitzer L. Improved method for the isolation of RNA from plant tissues. Anal Biochem. 1987;163:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin R A, Johnston H W. Effects and control of Fusarium diseases of cereal grains in the Atlantic provinces. Can J Plant Pathol. 1982;4:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller J D, Taylor A, Greenhalgh R. Production of deoxynivalenol and related compounds in liquid culture by Fusarium graminearum. Can J Microbiol. 1983;29:1171–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss M O. Economic importance of mycotoxins—recent incidences. Int Biodeterior. 1991;27:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neissen M L, Vogel R F. A molecular approach to the detection of potential trichothecene producing fungi. In: Mesterhazy A, editor. Cereals research communications. Proceeding of the Fifth European Fusarium Seminar, Szeged, Hungary—1997. Szeged, Hungary: Cereals Research Institute; 1997. pp. 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orbach M J, Porro E B, Yanofsky C. Cloning and characterization of the gene for β-tubulin from a benomyl-resistant mutant of Neurospora crassa and its use as a dominant selectable marker. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2452–2461. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proctor R H, Hohn T M, McCormick S P. Reduced virulence of Gibberella zeae caused by disruption of a trichothecene toxin biosynthetic gene. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:593–601. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rashtchian, A. 1994. Amplification of RNA. PCR Methods Applic. Suppl. S83–S97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ryu J-C, Yang J S, Song Y S, Kwon O H, Park J, Chang I M. Survey of natural occurrence of trichothecene mycotoxins in Korean cereals in 1992 using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Food Add Contam. 1996;13:333–341. doi: 10.1080/02652039609374416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith P. Ph.D. thesis. Norwich, United Kingdom: University of East Anglia; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snedecor G W, Cochran W G. Statistical methods. Ames: The Iowa State University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snijders C H A, Krechting C F. Inhibition of deoxynivalenol translocation and fungal colonization in Fusarium head blight resistant wheat. Can J Bot. 1992;70:1570–1576. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suty A, Mauler-Machnik A, Courbon R. Proceeding of the BCPC—Pests and Diseases, 1996. Vol. 2. Farnham, United Kingdom: Brighton Crop Protection Conference Publication; 1996. New findings on the epidemiology of Fusarium ear blight of wheat and its control; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zadoks J C, Chang T T, Konzak C F. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res. 1974;14:415–421. [Google Scholar]