Abstract

We investigated the ability of a detoxified derivative of a Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2)-encoding bacteriophage to infect and lysogenize enteric Escherichia coli strains and to develop infectious progeny from such lysogenized strains. The stx2 gene of the patient E. coli O157:H7 isolate 3538/95 was replaced by the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene from plasmid pACYC184. Phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) was isolated after induction of E. coli O157:H7 strain 3538/95 with mitomycin. A variety of strains of enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), Stx-producing E. coli (STEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), and E. coli from the physiological stool microflora were infected with φ3538(Δstx2::cat), and plaque formation and lysogenic conversion of wild-type E. coli strains were investigated. With the exception of one EIEC strain, none of the E. coli strains supported the formation of plaques when used as indicators for φ3538(Δstx2::cat). However, 2 of 11 EPEC, 11 of 25 STEC, 2 of 7 EAEC, 1 of 3 EIEC, and 1 of 6 E. coli isolates from the stool microflora of healthy individuals integrated the phage in their chromosomes and expressed resistance to chloramphenicol. Following induction with mitomycin, these lysogenic strains released infectious particles of φ3538(Δstx2::cat) that formed plaques on a lawn of E. coli laboratory strain C600. The results of our study demonstrate that φ3538(Δstx2::cat) was able to infect and lysogenize particular enteric strains of pathogenic and nonpathogenic E. coli and that the lysogens produced infectious phage progeny. Stx-encoding bacteriophages are able to spread stx genes among enteric E. coli strains.

Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains have emerged as a serious foodborne pathogen that has caused large-scale outbreaks of intestinal diseases in the developed countries (10). Whereas E. coli O157:H7 is the predominant STEC serotype isolated from patients in the United States, Canada, and Japan (3, 10), STEC strains belonging to other serotypes (non-O157 STEC) have been responsible for outbreaks and sporadic cases of human disease in continental Europe (6). Pathogenic STEC strains share several determinants implicated in pathogenesis. These include Stx and a pathogenicity island termed LEE, the latter encoding proteins responsible for the intimate adherence of STEC to the intestinal mucosa and for the subsequent characteristic destruction of the microvilli termed “attaching and effacing” lesions (15, 18).

Stx are the major pathogenicity factors of these organisms, and there is evidence that they are involved in the development of extraintestinal complications, such as the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (25). Stx of E. coli are a family of proteins which are cytotoxic to eucaryotic cells expressing the glycolipid receptor globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) (17). They function as rRNA-N-glycosidases and inhibit protein biosynthesis in target cells (9). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that Stx may induce apoptosis in renal tubular cells (37). The members of the Stx family of E. coli share genetic, structural, and functional features and consist of Stx1, Stx2, and variants of Stx2 (18). Stx1 is nearly identical to Stx of Shigella dysenteriae type 1, but it shares only 55% amino acid sequence identity with Stx2 (18). In addition, Stx1 and Stx2 are not neutralized by heterologous antisera (34, 36).

Stx1 and Stx2 are encoded in the genomes of several lambdoid prophages (8, 13, 22, 36). It has been shown that such Stx-encoding phages are heterogeneous in their genetic structure and size (39). The Stx1-converting bacteriophages H19J (24) and H19B (35), originally isolated from Stx-producing O26:H11 strain H19, and the Stx2-converting bacteriophage 933W derived from E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (24) have been characterized intensively (12, 21, 35, 36). It has been demonstrated that the stx1 and stx2 genes in STEC O157:H7, O26, and O111 are closely associated with a p-like gene which is similar to the p gene of bacteriophage λ (8). This implicated that the stx genes of different Stx-converting bacteriophages were located in the same site. This was confirmed in a later study which also demonstrated the presence of an ileX tRNA gene upstream of the stx2 gene in STEC O157:H7, O26:H11, O103:H2 and O111:H2 strains (33). In addition, Neely and Friedman (21) characterized a 17-kb DNA segment of the Stx1-encoding phage H19B that covers an analogue of the λ Q transcription activator, the stx1 gene, and an open reading frame homologous to the λ holin lysis gene. They suggested a role for the λ-like Q protein and the holin lysis genes in the regulation of stx expression and release of the protein from the bacterial cell. They also showed that the Stx2-encoding phage 933W had a similar structure in this region (21). The complete sequence of phage 933W was recently published and also provides evidence for the linkage of phage induction and stx expression (27).

Recently, Stx2-converting bacteriophages originating from E. coli O157:H7 outbreak strains isolated in Japan were characterized. The authors described one phage, Stx2φ-I, which resembled phage 933W and another phage, Stx2φ-II, which had properties distinct from those of Stx2φ-I (38). Stx2φ-I was demonstrated to use the FadL protein as a receptor and the receptor for Stx2φ-II was the LamB protein (38).

Stx-encoding phages may be the major cause for the spread of stx genes among wild-type E. coli and for the emergence of new STEC types. Evidence for this has been provided by Acheson et al. (1) who showed that a derivative of bacteriophage H19B was able to transduce an E. coli recipient laboratory strain in the murine gastrointestinal tract.

In this study, we constructed a detoxified derivative of a Stx2-converting phage—φ3538(Δstx2::cat)—which conferred chloramphenicol resistance to assess the range of infectivity of this bacteriophage and to study its postuptake integration, stability, and inducibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and bacteriophages.

Most of the E. coli wild-type strains used in this study were from our strain collection and were isolated during routine diagnostic work in recent years from stools of patients with diarrhea or HUS. Pure cultures of wild-type isolates were stored in stab cultures. All in all, from the initial isolation up to the phage experiments, isolates were passaged four times at most. They included 25 STEC (17 serotype O157:H7 or O157:H− and 8 non-O157 serotypes), 11 enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), 6 enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), 5 enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), and 3 enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) strains. Six E. coli strains were isolated from stools of healthy individuals and do not belong to any of the enteric E. coli pathogroups. E. coli O157:H7 strain 3538/95 was isolated from a patient with HUS in Würzburg, Germany, in 1995. This strain carried stx2, eae, and E-hly and was cytotoxic to Vero cells. The EAEC O111 strain DEF 53 was kindly provided by Anna Giammanco, University of Palermo, Italy.

E. coli DH5α (29) was used as a host strain for plasmids and phages and as an indicator strain. E. coli SM10λpir (thi-1 thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu Kmr λpir) served as a donor for conjugation experiments with plasmid pGP704 (11). The E. coli K-12 derivative C600 strain was used as a positive control in transduction experiments with phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) and as an indicator strain. Plasmid pACYC184 (7) was used as a source of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene. Plasmids pUC18 (Apr) and pGP704 (Apr ori R6K mob RP4 MCS of M13tg131) were used as cloning vectors; the latter delivered suicide functions. Stx2-converting phage 933W was prepared from E. coli C600(933W) (24) and used as a control in the plaque assays with wild-type E. coli strains.

Culture techniques.

Mutants of E. coli O157:H7 strain 3538/95 resistant to nalidixic acid were obtained by sequential incubation of this strain in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing increasing concentrations of nalidixic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany) ranging from 0.5 to 40 μg/ml. A single colony resistant to 40 μg of nalidixic acid per ml was stored and designated 3538/95 (Nalr).

Filter mating of E. coli SM10 λpir/pHS3 and E. coli O157:H7 3538/95 (Nalr) was performed according to the method of Miller (19) in a ratio of 1:4 with minor modifications. The LB agar plate containing the mating mixture was incubated for 8 h at 37°C. Selection of transconjugants was performed on agar plates containing 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 μg of nalidixic acid per ml that were incubated for 48 h at 37°C.

MICs of chloramphenicol were determined with E-test strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plaque assay and preparation of stock lysates of φ3538(Δstx2::cat).

A log-phase culture (optical density at 600 nm of 0.5) of strain 3538/95(Δstx2::cat) in tryptone soya broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) containing 5 mM CaCl2 was adjusted to a final mitomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) concentration of 0.5 μg/ml, and the cultivation was continued overnight. Bacterial cells were sedimented at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane filter (Schleicher & Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany). In the plaque assay, 100 μl of the filtrate, 100 μl of an overnight culture of E. coli C600, and 125 μl of 0.1 M CaCl2 solution were mixed with 3 ml of LB soft agar (0.7%) at 48°C and poured onto an LB agar plate containing 2% agar. Plaques were observed after overnight incubation at 37°C. A high-titer stock lysate of φ3538(Δstx2::cat) was prepared from a single plaque according to the method described by Sambrook et al. (29) for phage λ. This stock lysate contained 108 PFU/ml.

Infection of enteric E. coli strains with φ3538(Δstx2::cat).

One hundred microliters of log-phase cultures of enteric E. coli containing 107 CFU was mixed with 100 μl of a 1:1,000 dilution of φ3538(Δstx2::cat) stock lysate (104 PFU), and the ability of wild-type E. coli to form plaques and to develop lysogens was investigated. The plaque assay was performed as described above, with the exception that the LB basal layer contained 0.5 μg of mitomycin per ml.

For the detection of lysogens, bacterial cultures were initially incubated with φ3538(Δstx2::cat) for 4 h at 37°C. Then they were transferred to 4 ml of LB broth containing 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and selective enrichment of lysogenic (chloramphenicol resistant [Camr]) bacteria was performed for 48 h at 37°C and 180 rpm. Bacteria were then harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min and transferred to LB agar plates containing 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml (Cam-agar) by single-colony streaking. Colonies grown on Cam-agar after overnight incubation were confirmed to be lysogens by PCR with stx2-specific primers HSB1 and HSB3. The appearance of a 1.57-kb PCR product proved the presence of the cat gene linked to the pieces of stx2 (Fig. 1D) and thus lysogenization of the strains with φ3538(Δstx2::cat).

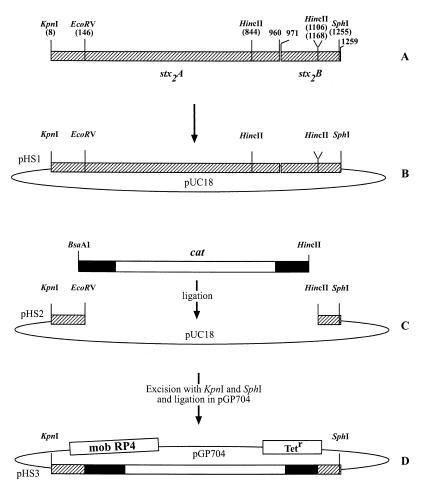

FIG. 1.

Construction of a vector for gene replacement mutagenesis of the stx2 gene. (A) PCR product of the entire stx2 gene obtained by amplification with primers HSB1 and HSB3. (B) Ligation of the PCR product in vector pUC18. (C) Replacement of an internal EcoRV-HincII fragment of the stx2 gene with an BsaAI-HincII fragment of pACYC184 covering the cat gene. (D) Ligation of the Δstx2::cat construct in suicide vector pGP704. Restriction sites are depicted. The numbering in panel A corresponds to the beginning of the PCR product. Hatched bars depict the stx2A and stx2B subunit genes. The fragment derived from pACYC184 is noted by a dark box, and the cat gene is noted by a light box.

General recombinant DNA techniques.

Plasmids were purified with the Nucleobond AX100 Preparation kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Restriction, ligation, and cloning experiments as well as the preparation of phage DNA were performed according to standard methods (29). Total DNA was prepared as described by Datz et al. (8).

For Southern blot hybridization experiments, either plaques from LB plates or DNA fragments from agarose gels were transferred to nylon membranes (Zeta-probe GT; Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) by standard procedures (29). DNA was fixed with a cross-linker (Stratalinker UV Crosslinker 1800; Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) by using the autocross-link mode (120,000 μJ/cm2). Stringent hybridization was achieved with the DIG (digoxigenin) DNA labelling and detection kit (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A 1,343-bp BsaAI-HincII fragment of pACYC184 containing the cat gene was randomly labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP and used as a probe.

Nucleotide sequences were determined by Taq cycle sequencing with universal and reverse primers for pUC/M13 vectors and HSB1 and HSB3 complementary to the sequences of the stx2 gene as described previously (30). Nucleotide sequence analysis was performed with the Lasergene program package (Dnastar, Madison, Wis.).

PCR.

Primers HSB1 (5′-CCC GGT ACC ATG AAG TGT ATA TTA TTT AAA TGG-3′) and HSB3 (5′-CCC GCA TGC TCA GTC ATT ATT AAA CTG CAC-3′) were designed to amplify the entire stx2 gene, yielding a 1,259-bp PCR product containing KpnI and SphI restriction sites at the respective 5′ ends. PCRs were performed with the GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Perkin-Elmer-Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) in a volume of 50 μl containing each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at 200 μM, 30 pmol of each primer, 5 μl of 10-fold-concentrated polymerase synthesis buffer, 3 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 solution, and 2.0 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems). The DNA was denatured at 94°C for 30 s, annealed at 53°C for 60 s, and then extended for 60 s at 72°C. After 30 cycles were completed, a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C was conducted.

Construction of an stx2-negative derivative of φ3538 which encodes chloramphenicol resistance.

From sequence studies, we did not expect alteration of essential phage functions by mutagenesis in the stx region. Therefore, the stx gene was chosen as a target for mutagenesis of the phage. The entire stx2 gene of strain 3538/95 was amplified with primers HSB1 and HSB3. The resulting 1,259-bp PCR product (Fig. 1A) was separated on a 0.6% agarose gel, excised from the gel, and then purified with the Prep-a-Gene kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). After restriction with KpnI and SphI, the fragment was again purified and ligated in plasmid pUC18, which was digested with the same enzymes (Fig. 1B). This plasmid was designated pHS1. Plasmid pHS1 was then digested with EcoRV and HincII, which cleaved at positions 146 and 1168 in the stx2 gene (Fig. 1A), and electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel. One of the resulting DNA fragments with a size of 2,875 bp was excised from the gel. It contained plasmid vector pUC18 with the remaining short fragments of 138 bp (A subunit gene) and 87 bp (B subunit gene) of the stx2 gene (Fig. 1C). A 1,343-bp BsaAI-HincII fragment prepared from pACYC184 was ligated with the 2,875-bp fragment resulting in plasmid pHS2 (Fig. 1C). This plasmid now conferred resistance to chloramphenicol and carried short stx2 sequences (Fig. 1C) on both sides of the cat gene. The whole Δstx2::cat construct was then excised from pHS2 with KpnI and SphI and ligated in suicide vector pGP704, digested with the same enzymes. This yielded pHS3 (Fig. 1D). The ligation samples were transformed in E. coli SM10 λpir. Transformants were checked to carry the Δstx2::cat construct by PCR with primers HSB1 and HSB3. A 1,567-bp product was detected, proving the presence of the cat gene. Nucleotide sequence analysis with primers HSB1 and HSB3 also confirmed that the Δstx2::cat cassette was inserted correctly.

Plasmid pHS3 was then transferred into E. coli O157:H7 strain 3538/95 (Nalr) by filter mating. Transconjugants were selected on agar plates containing nalidixic acid and chloramphenicol. Only recipient strains containing the recombinant suicide plasmid pHS3 could grow on these plates. Since the recipients did not express the π protein, pHS3 got lost in subsequent culture passages; only those recipients which had integrated the cat gene in their chromosome by homologous recombination could grow. One such isolate was characterized. PCR with primers HSB1 and HSB3 showed that the Δstx2::cat fusion was present in the E. coli O157:H7 recipient. In addition, plasmids the size of pHS3 could not be detected by preparation methods. The lack of tetracycline resistance also gave evidence that the suicide plasmid was absent. The transconjugant was then confirmed to be a derivative of its parental strain by serotyping, PCR, and sequencing. However, it was not cytotoxic for Vero cells. The strain was designated E. coli 3538/95(Δstx2::cat).

Induction of E. coli 3538/95(Δstx2::cat) with mitomycin and subsequent plaque assay with DH5α as an indicator confirmed the presence of infectious particles of φ3538(Δstx2::cat). In addition, φ3538(Δstx2::cat) converted its laboratory host strain DH5α to express resistance to chloramphenicol.

RESULTS

Transduction of various enteric E. coli strains with φ3538(Δstx2::cat).

In order to investigate the ability of φ3538(Δstx2::cat) to spread among enteric E. coli strains, we performed transduction experiments which exploited the fact that the phage could convert its host to express chloramphenicol resistance. Before starting these experiments, we determined the MIC of chloramphenicol for all 57 wild-type strains. The MICs ranged from 0.5 to 4.0 μg/ml and were mostly ≤3.0 μg/ml. The MICs for E. coli C600 and DH5α were 1.5 and 4.0 μg/ml, respectively, and that for strain 3538/95(Δstx2::cat) was 128 μg/ml. Since the breakpoint for sensitivity of E. coli to chloramphenicol is ≤8 μg/ml (20), all strains used in this study except for 3538/95(Δstx2::cat) were sensitive to chloramphenicol. The concentration of 30 μg/ml that represented a 10-fold MIC for more than half of the wild-type strains and inhibited growth of all of them was chosen for selection of lysogens. The MICs for the relevant strains are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Infection of enteric E. coli strains with φ3538(Δstx2::cat) and production of lysogens

| Bacterial strain | Serotype | stx geno-typea | MIC (μg/ml)b | E. coli group | Source or referencec | Result of infection with φ3538(Δstx2::cat)d

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque formation on mitomycin-LB | Growth of infected cells on Cam-LB | PCR for detection of lysogense | Inducibility of lysogens with mitomycin | Plaque hybridi-zation with cat probe (%)f | ||||||

| 11-1/87 | O111:H2 | − | 3.0 | EPEC | SC | − | + | + | + | + (0.5) |

| 6416/87 | O26:H− | − | 4.0 | EPEC | SC | − | + | + | + | + (0.1) |

| EDL933 | O157:H7 | 1, 2 | 4.0 | STEC | 23 | − | + | + | + | + (2.0) |

| 778/98 | O157:H7 | 1, 2 | 4.0 | STEC | SC | − | + | + | + | + (0.2) |

| 3574/92 | O157:H7 | 2 | 3.0 | STEC | 28 | − | + | + | + | + (52.0) |

| 2987/98 | O157:H7 | 1, 2, 2c | 4.0 | STEC | SC | − | + | + | + | + (0.1) |

| 1249/87 | O157:H7 | 2, 2c | 3.0 | STEC | 28 | − | + | + | + | + (63.0) |

| 1658/91 | O157:H7 | 2, 2c | 3.0 | STEC | 28 | − | + | + | + | + (10.0) |

| 1193/89 | O157:H− | 1 | 3.0 | STEC | 28 | − | + | + | + | + (82.0) |

| 7513/91 | O157:H− | 2c | 3.0 | STEC | 28 | − | + | + | + | + (60.0) |

| 5291/92 | O157:H− | 1, 2c | 3.0 | STEC | 28 | − | + | + | + | + (53.0) |

| 427/89 | O157:H− | 1, 2c | 2.0 | STEC | SC | − | + | + | − | NPg |

| 3901/97 | O26:H− | 1, 2 | 3.0 | STEC | SC | − | + | + | + | + (30.0) |

| DEF 53 | O111:HND | − | 4.0 | EAEC | AG | − | + | + | + | + (0.2) |

| 4140-86 | O44:HND | − | 3.0 | EAEC | SC | − | + | +h | NP | NP |

| 12860 | O124:HND | − | 1.0 | EIEC | SC | + | + | + | + | + (100.0) |

| 7 | NDi | − | 4.0 | PSj | SC | − | + | + | + | + (15.0) |

| C600 | ND | − | 1.5 | LSk | SC | + | + | + | + | + (100.0) |

stx1 was detected by amplification with primers KS7 and KS8 (32), and the stx2 and stx2c genes were both amplified with primers GK3 and GK4 and differentiated from each other by restriction analysis with HaeIII and FokI (28). −, stx negative.

MIC of chloramphenicol for wild-type E. coli strains.

SC, strain collection; AG, strain from Anna Giammanco, Palermo, Italy.

Mitomycin-LB, LB agar plates containing 0.5 μg of mitomycin per ml; Cam-LB, LB agar plates containing 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml.

Primers HSB1 and HSB3 were used to amplify the cat gene within the Δstx2::cat fusion in the genome of φ3538(Δstx2::cat).

Percentage of the total number of plaques present on matrix LB agar plates.

NP, not performed.

PCR was positive with a pool of colonies; a single PCR-positive colony was not found.

ND, not determined.

PS, strain of physiological intestinal microflora.

LS, laboratory strain.

In the experiments, 107 CFU of log-phase cultures of the test strains were exposed to 104 PFU of phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat), and development of plaques and production of lysogens were determined. Only 1 of 57 wild-type strains, EIEC 12860, formed plaques upon infection with φ3538(Δstx2::cat) (Table 1). None of the other wild-type strains used as indicator strains supported the formation of plaques. The same results were obtained when the Stx2-converting phage 933W and the original (unlabeled) phage φ3538/95 were used as positive controls to infect these strains.

Since the phage-associated cat gene confers resistance to chloramphenicol, the ability to grow on Cam-agar was used as a marker to screen for lysogens. The 57 wild-type strains were subjected to the selective chloramphenicol enrichment procedure after having been exposed to φ3538(Δstx2::cat). Camr colonies developed in 26 of 57 strains. PCR with primers HSB1 and HSB3 performed with 15 pooled colonies of each of these Camr strains confirmed that 17 of the 26 strains were lysogenized with φ3538(Δstx2::cat). From the remaining nine PCR-negative strains, up to 100 colonies were subsequently investigated, but the presence of the phage could not be demonstrated.

Control experiments were conducted under the same conditions with wild-type strains that had not been exposed to φ3538(Δstx2::cat). Only two strains developed Camr colonies, with a frequency of 4 × 10−8 during the selective enrichment procedure.

In total, lysogenization with φ3538(Δstx2::cat) occurred in 2 of 11 EPEC strains, 2 of 7 EAEC strains, 1 of 3 EIEC strains, and 1 of 6 physiological E. coli strains. None of five ETEC strains was lysogenized. Among the STEC strains tested, 1 of 8 non-O157 strains and 10 of 17 O157 strains were lysogenized by φ3538(Δstx2::cat). The 17 strains that produced lysogens are characterized in Table 1.

The laboratory strain E. coli C600 was used as a positive control in φ3538(Δstx2::cat) transduction experiments. As demonstrated in Table 1, the strain formed plaques upon infection with the phage and produced lysogens from which infectious phage particles were induced by treatment with mitomycin.

Location of the cat gene in the lysogens.

In order to determine whether the lysogens had inserted φ3538(Δstx2::cat) into the chromosome or into a plasmid, plasmid and total DNA were prepared from five selected lysogens. Among these there were stx-negative as well as stx-carrying strains. The DNA preparations were restricted with EcoRV and HincII and separated in parallel on agarose gels. Hybridization with the cat probe demonstrated a signal with a size of approximately 2,800 bp in the total DNA preparations of all strains tested. However, no hybridization signals were present in the respective plasmid preparations (data not shown). These experiments clearly proved the association of the cat gene with the bacterial chromosome.

Induction of φ3538(Δstx2::cat) from the lysogens.

Sixteen of 17 lysogens were further investigated for their ability to produce infectious particles of phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) after induction with mitomycin. The EAEC strain 4140-86 was excluded from this study because we were not able to isolate lysogens from the PCR-positive colony pool (Table 1). As demonstrated in Table 1, 15 of 16 lysogens could be induced with mitomycin and produced phage progeny that formed plaques on a lawn of the indicator strain E. coli C600.

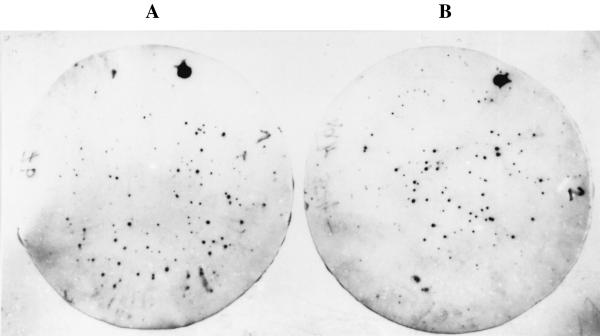

We hybridized these plaques with a probe specific for the cat gene. Signals, examples of which are shown in Fig. 2, were obtained from plaques of all of the lysogens. However, in 14 of 15 lysogens, only some of the plaques hybridized with the cat probe; the proportion of the φ3538(Δstx2::cat)-associated plaques ranged from 0.1% to 82% (Table 1). To ensure that the hybridization signals were specific, control hybridization experiments were performed. All 15 parental E. coli strains (not transduced with φ3538(Δstx2::cat) were also induced, and the supernatants were investigated for plaque formation. Plaques were observed with supernatants of 12 of the 15 strains. Plaque hybridization with the cat probe was performed and was negative in all cases, demonstrating that no cat-like sequences were present in the parental E. coli strains. Moreover, hybridization of chromosomal DNA of all 57 wild-type strains with the same probe was also negative.

FIG. 2.

Plaque hybridization. Phage lysates prepared from the lysogens E. coli O157:H− strain 1193/89(Δstx2::cat) (A) and E. coli O157:H7 strain 3574/92(Δstx2::cat) (B) after mitomycin induction were mixed with E. coli C600 indicator bacteria in soft agar and poured onto LB agar. Plaques were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled cat gene probe. Plasmid pACYC184 DNA was used as a positive control and is seen in the upper part of the membranes (large dots). stx1B and stx2B PCR products, respectively, were used as negative controls on the membranes.

In addition, phages isolated from five selected lysogens were tested for the ability to transduce chloramphenicol resistance into the laboratory strain DH5α. After mitomycin induction, we were able to isolate phages containing the cat gene from all lysogens. Laboratory strain DH5α was transduced with these phages, and the cat-harboring phages could be reisolated from such transductants. Control experiments were performed with mitomycin-induced supernatants of the parental strains not harboring φ3538(Δstx2::cat). However, DH5α could not be converted to chloramphenicol resistance by any of the supernatants.

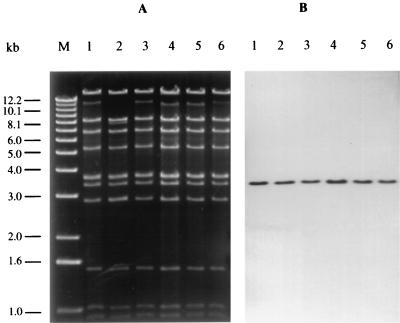

In order to study putative recombination events that could have occurred in the phage during the alternating lysogenic and lytic cycles, we compared restriction fragment profiles of the original phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) and the phages that we have isolated from the DH5α transductants as described above. It could be demonstrated (Fig. 3) that the phages had identical restriction patterns. Hybridization experiments demonstrated that the same restriction fragment of the phage DNAs hybridized with the cat probe.

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis (A) and Southern blot hybridization (B) of phage DNA restricted with EcoRI. DNA of the original phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) (lanes 1) was compared with DNA from phage progeny that has been isolated from the lysogens 1193/89(Δstx2::cat) (lanes 2), 3574/92(Δstx2::cat) (lanes 3), 12860(Δstx2::cat) (lanes 4), 7513/91(Δstx2::cat) (lanes 5), and 1249/87(Δstx2::cat) (lanes 6) and processed in E. coli laboratory strain DH5α as described in the text. M, molecular weight standard (1-kb DNA ladder; Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany).

DISCUSSION

STEC strains demonstrate a broad range of genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Until now, the mechanisms by which this heterogeneity has evolved have been poorly understood. Besides recombination events and spontaneous mutations, mobile genetic elements could play a role. Although Stx are known to be encoded by temperate, lambdoid prophages, the role of these phages in the spread of stx genes has not been well elucidated.

STEC strains belong to more than 100 serotypes (14), and transduction of stx genes by phages to other enteric E. coli strains may contribute to the observed heterogeneity in STEC serotypes. Acheson et al. (1) demonstrated that it was possible to infect and lysogenize an E. coli laboratory strain with an Stx1-converting phage in the murine gastrointestinal tract. In addition, transductants which produced infectious phage particles were isolated. Although these experiments were the first evidence for in vivo transduction activity of Stx-encoding phages, wild-type isolates were not used as recipients.

Similar experiments were performed with CTXφ, a filamentous Vibrio cholerae bacteriophage which encodes cholera toxin (16). Using a model with suckling CD1 mice, Lazar and Waldor showed transduction of CTXφ from a lysogen to a recipient strain in the small intestine (16). It was also reported that lysogenic conversion from a nonpathogenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae strain to a toxinogenic strain could occur in the upper respiratory tract (26).

Recently, Beutin et al. (4) demonstrated that Stx produced by a Shigella sonnei isolate was encoded by a bacteriophage which could be transduced to a nontoxinogenic S. sonnei reference strain and E. coli laboratory strains.

In the present study, we demonstrated that the detoxified phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat), which was isolated from a pathogenic STEC O157:H7 strain, was able to infect and lysogenize certain wild-type strains of E. coli. Moreover, lysogenic transductants produced infectious virus particles upon induction with mitomycin.

In total, we were able to detect 17 of 57 wild-type E. coli strains transduced with the phage, and these belonged to a broad spectrum of various enteric pathogroups as well as to the physiological intestinal microflora.

There are some limitations to the techniques used for the detection of lysogens described in this paper. First, the selection of lysogens depended on both the initial MIC of chloramphenicol for the host strains and the ability to develop spontaneous chloramphenicol resistance during the selective enrichment procedure.

To address this, we determined the MICs for all strains used in this study and found them to be low. All wild-type strains were sensitive to chloramphenicol. In control experiments, two of the wild-type strains which were not exposed to the phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) developed chloramphenicol resistance during the selective enrichment procedure. In these strains, the frequency of the appearance of Camr colonies was 4 × 10−8. This means that spontaneous mutation to Camr is a relatively rare process.

In contrast, after exposure to the phage, we found 26 Camr strains. From these, 17 strains contained phage φ3538(Δstx2::cat) and 9 did not. The nature of the Camr in the latter strains is not known.

Second, we were able to isolate lysogens from strains which did not support the formation of plaques. This may reflect the methodology used, lysogen isolation being more sensitive because of the selective chloramphenicol enrichment step. Without this step, we would not have been able to isolate any lysogen from wild-type isolates. In contrast, selective enrichment was not necessary for the isolation of lysogens from laboratory E. coli strains (31).

The lysogenized E. coli O157:H7/H− strains contained stx1, stx2, and stx2c genes alone or in combination. Since it was shown in earlier studies that Stx1 and Stx2 are generally phage encoded (8, 21, 36), this was assumed for the E. coli O157 strains tested here. The fact that it was possible to lysogenize such strains with φ3538(Δstx2::cat) indicates that the Stx-encoding prophages which were likely to be present in these strains were different from φ3538(Δstx2::cat). Otherwise superinfection immunity would have prevented infection.

The presence of temperate Stx-converting phages that were not related to φ3538(Δstx2::cat) could explain why in most of the lysogens, only a part of plaques hybridized with the cat probe (Table 1). Natural E. coli strains frequently contain sequences which are related to phage λ and presumed to be cryptic prophages (2). The most intensively studied were those present in E. coli K-12, whose chromosome contains, besides phage λ itself, four phage-related elements, including DLP12, Rac, Qin, and e14 (5). Cryptic prophages can alter the host phenotype and directly or indirectly interact with active phages. They can mediate superinfection immunity, recombine with active phage DNA, or modify the host surface properties (5). Moreover, natural E. coli strains can harbor active lambdoid prophages, examples of which are HK022, P2, and 434 (5). In order to successfully infect a host cell, Stx-converting phages probably have to compete with naturally occurring phages or phage-related elements. This could lead to the failure of establishment of the superinfecting phage.

The obvious presence of several prophages in E. coli isolates could also contribute to the failure of the labeled phage to establish in the chromosome in a way that the insertion sites could be occupied, and therefore the phage could not replicate.

Another interesting aspect of our study concerns the genetic stability of φ3538(Δstx2::cat). We could not detect any recombination of this phage with extant phages of E. coli O157 strains, even under chloramphenicol selection.

In conclusion, using a model of a detoxified derivative of an Stx2-converting bacteriophage, we have demonstrated that Stx2-converting bacteriophages are able to spread among enteric E. coli strains and may thus contribute to the genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity observed in the STEC family. The findings described here suggest a role for Stx-encoding bacteriophages in the spread of stx genes among enteric E. coli strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Beatrix Henkel for excellent technical assistance and Phil I. Tarr for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grant Ka 717/3-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acheson D W K, Reidl J, Zhang X, Keusch G T, Mekalanos J J, Waldor M K. In vivo transduction with Shiga toxin 1-encoding phage. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4496–4498. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4496-4498.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anilionis A, Riley M. Conservation and variation of nucleotide sequences within related bacterial genomes: Escherichia coli strains. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:355–365. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.355-365.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell B P, Goldoft M, Griffin P M, Davis M A, Gordon D C, Tarr P I, Bartleson C A, Lewis J H, Barrett T J, Wells J G, Baron R, Kobayashi J. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from hamburgers. The Washington experience. JAMA. 1994;272:1349–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutin L, Strauch E, Fischer I. Isolation of Shigella sonnei lysogenic for a bacteriophage encoding gene for production of Shiga toxin. Lancet. 1999;353:1498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell A M. Cryptic prophages. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Brooks Low K, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2041–2046. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caprioli A, Tozzi A E. Epidemiology of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in continental Europe. In: Kaper J B, O’Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datz M, Janetzki-Mittmann C, Franke S, Gunzer F, Schmidt H, Karch H. Analysis of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 DNA region containing lambdoid phage gene p and Shiga-like toxin structural genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:791–797. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.791-797.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endo Y, Tsurugi K, Yutsudo T, Takeda Y, Ogasawara T, Igarashi K. Site of action of a Vero toxin (VT2) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and of Shiga toxin on eukaryotic ribosomes. RNA N-glycosidase activity of the toxins. Eur J Biochem. 1988;171:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin P M. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. In: Blaser M J, Smith P D, Ravdin J I, Greenberg H B, Guerrant R L, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 739–762. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang A, De Grandis S, Friesen J, Karmali M, Petric M, Congi R, Brunton J L. Cloning and expression of the genes specifying Shiga-like toxin production in Escherichia coli H19. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:375–379. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.375-379.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang A, Friesen J, Brunton J L. Characterization of a bacteriophage that carries the genes for production of Shiga-like toxin 1 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4308–4312. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4308-4312.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson R P, Clarke R C, Wilson J B, Read S C, Rahn K, Renwick S A, Sandhu K A, Alves D, Karmali M A, Lior H, McEwen S A, Spika J S, Gyles C L. Growing concerns and recent outbreaks involving non-O157:H7 serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Food Prot. 1996;59:1112–1122. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.10.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaper J B, Elliott S, Sperandio V, Perna N T, Mayhew G F, Blattner F R. Attaching-and-effacing intestinal histopathology and the locus of enterocyte effacement. In: Kaper J B, O’Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazar S, Waldor M K. ToxR-independent expression of cholera toxin from the replicative form of CTXφ Infect. Immun. 1998;66:394–397. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.394-397.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lingwood C A. Verotoxins and their glycolipid receptors. Adv Lipid Res. 1993;25:189–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melton-Celsa A R, O’Brien A D. Structure, biology, and relative toxicity of Shiga toxin family members for cells and animals. In: Kaper J B, O’Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A3. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neely M N, Friedman D I. Functional and genetic analysis of regulatory regions of coliphage H-19B: location of shiga-like toxin and lysis genes suggests a role for phage functions in toxin release. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1255–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newland J W, Strockbine N A, Miller S F, O’Brien A D, Holmes R K. Cloning of Shiga-like toxin structural genes from a toxin converting phage of Escherichia coli. Science. 1985;230:179–181. doi: 10.1126/science.2994228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien A D, Lively T A, Chen M E, Rothman S W, Formal S B. Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains associated with haemorrhagic colitis in the United States produce a Shigella dysenteriae 1 (SHIGA) like cytotoxin. Lancet. 1983;i:702. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91987-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien A D, Newland J W, Miller S F, Holmes R K, Smith H W, Formal S B. Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea. Science. 1984;226:694–696. doi: 10.1126/science.6387911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obrig T G. Interaction of Shiga toxins with endothelial cells. In: Kaper J B, O’Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pappenheimer A M, Jr, Murphy J R. Studies on the molecular epidemiology of diphtheria. Lancet. 1983;ii:923–926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90449-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plunkett G, III, Rose D J, Durfee T J, Blattner F R. Sequence of Shiga toxin 2 phage 933W from Escherichia coli O157:H7: Shiga toxin as a phage late gene-product. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1767–1778. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1767-1778.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rüssmann H, Schmidt H, Heesemann J, Caprioli A, Karch H. Variants of Shiga-like toxin II constitute a major toxin component in Escherichia coli O157 strains from patients with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:338–343. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-5-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt H, Beutin L, Karch H. Molecular analysis of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1055–1061. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1055-1061.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt, H., M. Bielaszewska, and H. Karch. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 32.Schmidt H, Rüssmann H, Schwarzkopf A, Aleksic S, Heesemann J, Karch H. Prevalence of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli in stool samples from patients and controls. Int J Med Microbiol Virol Parasitol Infect Dis. 1994;281:201–213. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt H, Scheef J, Janetzki-Mittmann C, Karch H. An ileX tRNA gene is located close to the Shiga toxin II operon in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 and non-O157 strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;149:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scotland S M, Smith H R, Rowe B. Two distinct toxins active on Vero cells from Escherichia coli O157. Lancet. 1985;ii:885–886. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith H W, Green P, Parsell Z. Vero cell toxins in Escherichia coli and related bacteria: transfer by phage and conjugation and toxic action in laboratory animals, chickens and pigs. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:3121–3137. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-10-3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strockbine N A, Marques L R M, Newland J W, Smith H W, Holmes R K, O’Brien A D. Two toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 933 encode antigenically distinct toxins with similar biologic activities. Infect Immun. 1986;53:135–140. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.135-140.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taguchi T, Uchida H, Kiyokawa N, Mori T, Sato N, Horie H, Takeda T, Fujimoto J. Verotoxins induce apoptosis in human renal tubular epithelium derived cells. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1681–1688. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watarai M, Sato T, Kobayashi M, Shimizu T, Yamasaki S, Tobe T, Sasakawa C, Takeda Y. Identification and characterization of a newly isolated Shiga toxin 2-converting phage from Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4100–4107. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4100-4107.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willshaw G A, Smith H R, Scotland S M, Field A M, Rowe B. Heterogeneity of Escherichia coli phages encoding Vero cytotoxins: comparison of cloned sequences determining VT1 and VT2 and development of specific gene probes. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1309–1317. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-5-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]