Abstract

Objective

Genicular artery embolization (GAE) is a novel, minimally invasive procedure for treatment of knee osteoarthritis (OA). This meta-analysis investigated the safety and effectiveness of this procedure.

Design

Outcomes of this systematic review with meta-analysis were technical success, knee pain visual analog scale (VAS; 0–100 scale), WOMAC Total Score (0–100 scale), retreatment rate, and adverse events. Continuous outcomes were calculated as the weighted mean difference (WMD) versus baseline. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) and substantial clinical benefit (SCB) rates were estimated in Monte Carlo simulations. Rates of total knee replacement and repeat GAE were calculated using life-table methods.

Results

In 10 groups (9 studies; 270 patients; 339 knees), GAE technical success was 99.7%. Over 12 months, the WMD ranged from −34 to −39 at each follow-up for VAS score and −28 to −34 for WOMAC Total score (all p < 0.001). At 12 months, 78% met the MCID for VAS score; 92% met the MCID for WOMAC Total score, and 78% met the SCB for WOMAC Total score. Higher baseline knee pain severity was associated with greater improvements in knee pain. Over 2 years, 5.2% of patients underwent total knee replacement and 8.3% received repeat GAE. Adverse events were minor, with transient skin discoloration as the most common (11.6%).

Conclusions

Limited evidence suggests that GAE is a safe procedure that confers improvement in knee OA symptoms at established MCID thresholds. Patients with greater knee pain severity may be more responsive to GAE.

Keywords: GAE, Genicular artery embolization, Knee, Pain, Osteoarthritis

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative disease of the synovial joints characterized by progressive chondral wear and bony remodeling which manifests clinically as joint pain and dysfunction. Although OA was once considered a sequela of a degenerative wear and tear process, the pathogenesis is more complex and now known to be a biomechanical whole-organ disease with a strong inflammatory component [1,2]. Knee OA is the leading cause of disability in older adults [3] and its prevalence is anticipated to increase in the coming decades [4]. More than 1 in 3 Americans over 60 years have radiographic evidence of knee OA, and approximately 40% of these individuals report bothersome symptoms [5]. While a variety of non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments for knee OA are available, these conservative measures are often clinically ineffective with regards to pain and fail to modify the disease process [6]. While total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the standard of care for individuals with severe knee OA, only 9%–33% of patients with severe knee OA are willing to consider TKA [[7], [8], [9]] and approximately 20% of patients who undergo TKA report dissatisfaction with the procedure [10] due to persistent pain mostly thought to be related to synovitis [11,12]. Thus, there is potential benefit to a large cadre of patients in enhancing the armamentarium of available minimally invasive procedures for knee OA.

Genicular artery embolization (GAE) is a novel, minimally invasive, nonsurgical intervention for patients with symptomatic knee OA who are refractory to other treatments yet reluctant to undergo or ineligible for TKA such as patients with mild-to-moderate OA or patients who are not a surgical candidate. The procedure involves selective catheterization of the genicular arteries supplying the synovial lining of the knee during an angiogram to target aberrant neovasculature that appear as tumor blush-type enhancement in the arterial phase on angiogram and correspond to areas of knee pain or tenderness. Embolization is performed by selective intra-arterial injection of embolic material to the site of knee pain and abnormal vascularity. GAE targets synovial arterial hypervascularity of the knee joint, which plays a significant role in the pathogenesis and progression of knee OA [13]. The procedure treats knee OA pain by reducing synovial blood flow, which is hypothesized to reduce knee pain related to inflammation, neovascularity, and neoinnervation [[14], [15], [16]]. While no studies have demonstrated structure-modifying effects of GAE for treatment of knee OA, improvements in synovitis using the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Scoring (WORMS) system [17] have been reported.

Current evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of GAE for treatment of knee OA is limited, with only three systematic reviews published to date [[18], [19], [20]]. Among these reviews, the most recent included studies published through 2020. Several relevant studies have since been published, warranting reappraisal of the evidence. Further, none of the previous reviews attempted to determine the clinical importance of the outcomes with GAE, or identify factors associated with these outcomes. Therefore, the primary objective of this systematic review with meta-analysis was to provide a contemporary evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of GAE for treatment of knee OA pain. A secondary objective of this review was to identify potential factors that may influence clinical outcomes following GAE for knee OA pain.

2. Methods

The systematic review protocol was prospectively registered at www.researchregistry.com (reviewregistry1430). Review methods followed the statement on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [21].

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Randomized trials, nonrandomized controlled studies, and case series of GAE for symptomatic knee OA were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. We excluded studies with a sample size of less than 10 patients, studies of patients treated with concomitant surgeries, duplicate publications, studies published in non-English language journals, studies published as abstracts or posters only, and studies that did not report any outcomes prespecified in this review.

2.2. Search strategy

We performed systematic searches of Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for potentially eligible studies. The search strategy included combinations of diagnosis-related (knee and osteoarthrit∗) and treatment-specific (genicula∗ or emboli∗) keywords. We purposely used a broad keyword strategy to maximize search sensitivity. Additional searches were conducted in the Directory of Open Access Journals and Google Scholar. We performed manual searches of the reference lists of included papers and relevant meta-analyses. Two researchers (LM, DF) with expertise in systematic reviews independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full-text manuscripts were obtained for all potentially relevant studies. Disagreements related to study eligibility were resolved by discussion and consensus. The final search was performed in August 2022.

2.3. Data extraction and outcomes

Data were extracted independently from eligible studies by two researchers (LM, DF) using standardized data collection forms developed a priori. Data included study characteristics, patient characteristics, periprocedural outcomes, risk of bias, efficacy outcomes, and safety outcomes. Data extraction discrepancies between the two researchers were resolved by discussion. The National Institute of Health assessment tool was applied to before-after studies to evaluate the methodological quality of eligible studies [22]. Efficacy outcomes included knee pain assessed on a visual analog scale (VAS) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Total score, which were extracted at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Knee pain VAS scores were converted to a 0 to 100 scale for analysis, with higher values indicating more severe pain. The WOMAC score measures pain and dysfunction associated with OA of the lower extremities by assessing 5 pain-related activities, 17 functional activities, and 2 stiffness categories [23]. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 scale, where 0 represents none and 4 represents extreme. The scores are then normalized to a 0 to 100 scale, where a higher score represents a worse outcome. Extraction of WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Stiffness scores was not possible due to insufficient data in the available studies. Retreatments and adverse events (AEs) were characterized through the final follow-up visit in each study.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Treatment effects for VAS knee pain and WOMAC total score were calculated as the weighted mean difference (WMD) relative to baseline at each follow-up interval using a random effects meta-analysis model with inverse variance weighting to account for anticipated inter-study heterogeneity. For each outcome, the WMD and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for each study and the overall pooled result. To facilitate clinical interpretation of meta-analysis results, we reported treatment effects using several patient-centric metrics. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is the smallest amount an outcome must change to be meaningful to patients [24]. The substantial clinical benefit (SCB) is the magnitude of improvement that a patient perceives as clinically considerable [25]. The MCID for knee pain VAS score was defined as a 20-point reduction (on a 0 to 100 scale) from baseline, greater than that cited in established norms, providing a conservative estimate of MCID [26]; no known SCB values for VAS pain were available. The MCID and SCB for WOMAC Total Score on a 0 to 100 scale were set at 16.8 points and 26.4 points, respectively [27]. We additionally calculated the standardized MCID as the WMD divided by the MCID [28,29]. Treatment effects below 0.5 MCID units indicate that patients are unlikely to obtain a clinically important benefit; treatment effects between 0.5 and 1 MCID units indicate that a moderate number of patients will obtain a clinically important benefit; and treatment effects above 1 MCID unit indicate that many patients would obtain a clinically important benefit from treatment [28,29]. We also performed Monte Carlo simulations where the variability in clinical outcomes was simulated in 1000 trials and the estimated percentage of patients achieving the MCID and SCB was reported. The cumulative rate of TKR and repeat GAE was calculated with life-table methods by determining the number of patients at risk, the number of procedures, and the number of censored patients at distinct intervals [30]. Adverse events were reported as weighted frequencies. We estimated heterogeneity among studies with the I2 statistic where a value of 0% represented no heterogeneity and larger values represented increasing heterogeneity [31]. We explored potential sources of heterogeneity using a random effects metaregression for any outcome reported in at least eight studies and with substantial heterogeneity (I2>50%). The metaregression model is a linear regression of the study effect sizes on moderators where the associations are adjusted for study size. The moderators that were included in the metaregression were baseline knee pain VAS score, body mass index, study design (prospective vs. retrospective), number of patients, number of knees, Kellgren-Lawrence grade, age, median year of treatment, number of treated arteries, and female gender proportion. P-values were two-sided with a significance level of < 0.05. Analyses were performed using Review Manager v5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata v. 16.1 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, United States).

3. Results

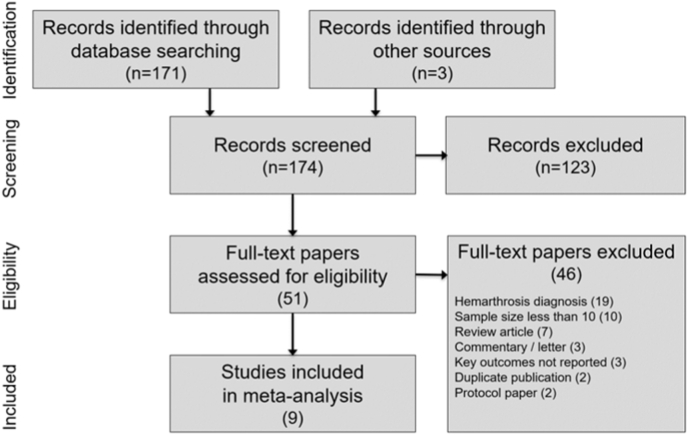

Among 174 papers identified in the literature search, 9 studies of GAE for treatment of knee OA were included in the systematic review [17,[32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. Among the full-text papers that were reviewed, 46 were excluded, with hemarthrosis diagnosis (19) and inadequate sample size (10) as the most common reasons for exclusion (Fig. 1). Only one study included a control group [33]; therefore, we extracted data only from the GAE arm of each study for the meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

The risk of bias was rated low for six studies, moderate for two studies, and high for one study (Supplement Table 1). Patient follow-up ranged from 1 to 48 months (median = 12 months) (Table 1). Among the included studies, 270 patients (339 knees) were included, 69% of patients were female, median age was 65 years, and median BMI was 28 kg/m2. Baseline knee OA characteristics included a study-wide median Kellgren-Lawrence score of 2.5, knee pain VAS score of 69, and WOMAC Total score of 54 (Supplement Table 2). Genicular artery embolization treatment details were reported inconsistently. The median number of treated arteries was 2.3 (range 1.5–5.0), procedure time ranged from 79 to 81 min, fluoroscopy time ranged from 14 to 29 min, and procedural radiation dose ranged from 49 to 128 mGy. The overall technical success rate was 99.7% (95% CI: 97.1–100%). However, technical success definitions among studies were inconsistent (Supplement Table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Study design | Treatment dates | Country (No. sites) | Patients | Knees | Key eligibility criteria | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagla [2020] [32] | P | 2017–2018 | US (2) | 20 | 20 | Age ≥40 yr | 6 |

| K-L grade 1-3 | |||||||

| Knee pain ≥5/10 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Bagla [2022] [33] | P | 2018–2019 | US (2) | 14 | 14 | Age >40 yr | 1 |

| K-L grade 1-3 | |||||||

| Knee pain >5/10 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Choi [2020] [34] | R | 2019 | Korea (1) | 18 | 28 | Intractable knee pain due to OA | 3 |

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Landers [2020] [35] | P | 2016–2017 | Australia (1) | 10 | 10 | Age 18–75 yr | 24 |

| K-L grade 1-2 | |||||||

| Moderate or severe knee pain | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Lee [2019] [36] | R | 2017–2018 | Korea (1) | 41 | 71 | K-L grade 1-4 | 12 |

| Knee pain ≥2/10 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Little [2021] [37] | P | 2018–2020 | UK (1) | 38 | 38 | Age ≥45 yr | 12 |

| K-L grade 1-3 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Okuno [2017] [17] | P | 2012–2016 | Japan (1) | 72 | 95 | Age 40–80 yr | 48 |

| K-L grade 1-3 | |||||||

| Knee pain >5/10 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Padia [2021] [38] | P | 2019–2020 | US (1) | 40 | 40 | Age 40–80 yr | 12 |

| K-L grade 2-4 | |||||||

| Knee pain >4/10 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure | |||||||

| Sun [2022] [39] | P | 2020–2021 | China (1) | 17 | 23 | Age >50 yr | 6 |

| Knee pain ≥5/10 | |||||||

| Conservative therapy failure |

K-L, Kellgren-Lawrence; OA, osteoarthritis; P, prospective; R, retrospective; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

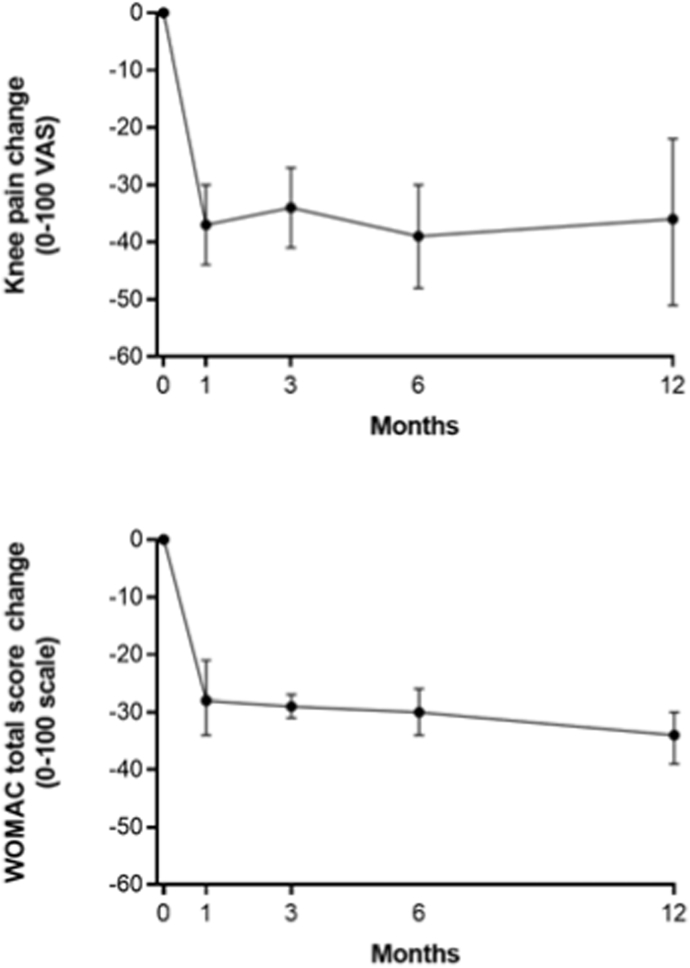

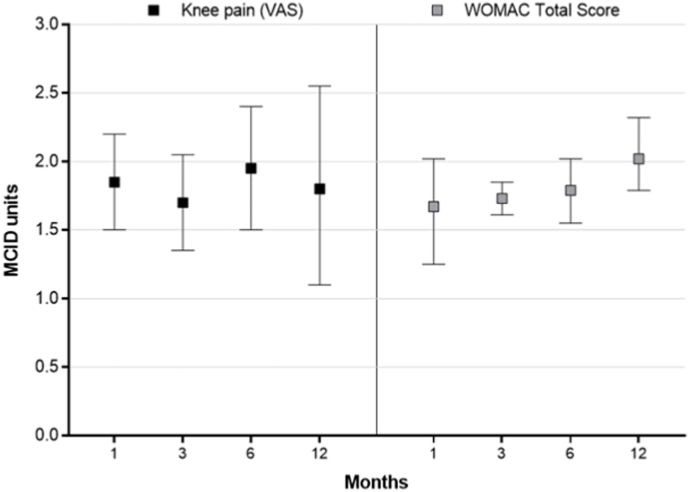

Knee OA symptoms significantly improved following GAE and the changes from baseline were statistically significant and clinically important at all follow-up intervals. The WMD for knee pain VAS score was −37 (95% CI: −44 to −30) at 1 month (8 cohorts), −34 (95% CI: −41 to −27) at 3 months (7 cohorts), −39 (95% CI: −48 to −30) at 6 months (6 cohorts), and −36 (95% CI: −51 to −22) at 12 months (5 cohorts) (all p < 0.001 vs. baseline) (Fig. 2a, Supplement Table 4). The WMD for WOMAC Total Score was −28 (95% CI: −34 to −21) at 1 month (5 cohorts), −29 (95% CI: −31 to −27) at 3 months (4 cohorts), −30 (95% CI: −34 to −26) at 6 months (4 cohorts), and −34 (95% CI: −39 to −30) at 12 months (2 cohorts) (all p < 0.001 vs. baseline) (Fig. 2b, Supplement Table 4). The improvement in knee OA symptoms in relation to the MCID ranged from 1.7 to 2.0 MCID units for knee pain and 1.7 to 2.0 MCID units for WOMAC Total Score at each follow-up interval (Fig. 3). In Monte Carlo simulations, the percentage of patients achieving the MCID was 76%, 78%, 87%, and 78% for knee pain VAS score at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. The percentage of patients achieving clinical benefit for WOMAC Total score at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months was 68%, 83%, 86%, and 92% when using MCID and 44%, 60%, 66%, and 78% when using SCB.

Fig. 2.

Temporal trends in knee pain and WOMAC Total score following genicular artery embolization. Plotted data are weighted mean and 95% confidence interval. P < 0.001 at each follow-up interval.

Fig. 3.

Improvement in knee osteoarthritis symptoms from baseline following genicular artery embolization reported in standardized minimal clinically important difference (MCID) units with 95% confidence interval. The MCID was set at 20 points for knee pain (0–100 scale) and 16.8 points for WOMAC Total score (0–100 scale). Treatment effects below 0.5 MCID units indicate that it is unlikely that an appreciable number of patients will show a clinically important benefit, treatment effects between 0.5 and 1 MCID units indicate that a treatment may be beneficial to an appreciable number of patients, and treatment effects above 1 MCID unit indicate that many patients may gain important benefits from treatment [28,29].

Change in knee pain VAS score at 1 month was the only variable reported in a sufficient number of studies for which significant heterogeneity was identified to explore potential sources of variability in metaregression. Greater reductions in knee pain at 1 month were observed in patients with higher baseline VAS scores (p < 0.001), patients with higher body mass index (p = 0.002), and in prospective studies (p = 0.008) (Supplement Table 5).

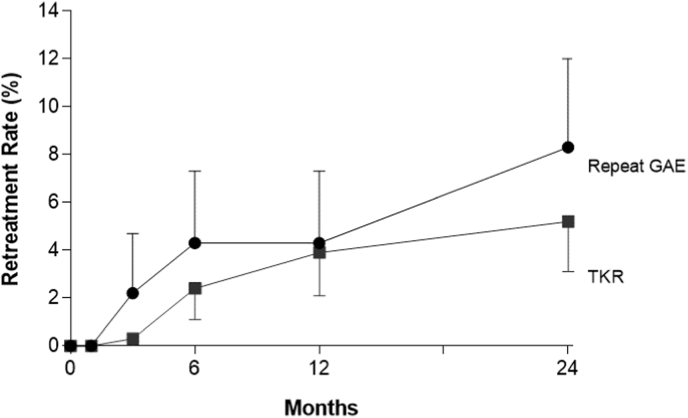

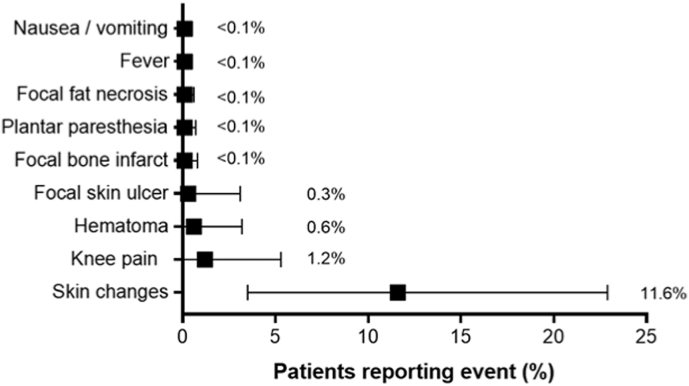

Over 2 years of follow-up, 5.2% (95% CI: 3.1–8.4%) of patients underwent TKR and 8.3% (95% CI: 5.6–12.0%) received repeat GAE (Fig. 4). Adverse events with GAE were typically minor and transient with 2.0% of patients requiring medication and 0.3% of patients requiring hospitalization. The most common adverse events with GAE were transient skin discoloration (11.6%; 95% CI: 3.5–22.9%), knee pain (1.2%; 95% CI: 0.0–5.3%), access site hematoma (0.6%; 95% CI: 0.0–3.2%), and focal skin ulcer (0.3%; 95% CI: 0.0–3.1%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Cumulative retreatment rate following genicular artery embolization (GAE). Plotted data are cumulative event rate and 95% confidence interval. At 2 years follow-up, the rate was 5.2% (95% CI = 3.1%–8.4%) for total knee replacement (TKR) and 8.3% (95% CI = 5.6%–12.0%) for repeat GAE.

Fig. 5.

Frequency of adverse events following genicular artery embolization. Plotted values are weighted event frequency and 95% confidence interval.

4. Discussion

Genicular artery embolization is a novel treatment option for knee pain in patients with knee OA. We performed a systematic review with meta-analysis of the safety and effectiveness of GAE for treatment of knee OA to provide a comprehensive and objective appraisal of the current literature. Our review demonstrated that GAE was technically successful in 99.7% of cases with few minor, transient complications. The magnitude of improvement in knee symptoms as reported on the pain VAS and WOMAC Total scales exceeded the value of published MCIDs over 1 year of follow-up. Finally, the rate of retreatment was low which could potentially suggest treatment durability following a single GAE procedure, versus ineffectiveness of initial treatment and patient reluctance for retreatment; retreatment data are therefore difficult to interpret without additional characterization.

Limited randomized controlled trial data is available to assess the magnitude of placebo effect associated with GAE. Bagla et al. [33] conducted a small randomized trial in which 14 patients were randomized to GAE and 7 to a sham procedure. All patients assigned to the sham procedure crossed over to GAE at the 1-month follow-up visit. Through 1 month, knee pain severity (0–100 scale) decreased by 51 points with GAE and 1 point with sham treatment (p < 0.01). Similarly, WOMAC Total scores (0–96 scale) decreased by 30 points and 5 points, respectively (p = 0.02). Based on this single study, the placebo effect from GAE appears minimal, unlike other knee OA treatments [40]. Additionally, most patients in the current meta-analysis met the MCID for knee pain VAS and WOMAC Total score at 12 months, beyond the expected duration of a placebo effect [40].

The results of our metaregression suggest that studies that included patients with greater knee pain severity at baseline demonstrated greater responsiveness to GAE. Specifically, based on the model intercept and point estimate provided by the metaregression results, and assuming an MCID of 20 points on the knee pain VAS [26], studies with mean knee pain baseline VAS scores over 50 points seem to show greater responsiveness to GAE. These results should be considered hypothesis-generating only and warrant further study.

This meta-analysis has certain limitations that may influence interpretation. Heterogeneity in study design, treatments, and outcomes among studies was frequently observed, which confounded data interpretation. There was also considerable variation in the completeness of data reported among studies. Consequently, we were unable to analyze WOMAC Pain or WOMAC Stiffness outcomes due to insufficient data. Next, the studies that informed this meta-analysis were primarily case series with limited sample sizes. Thus, the comparative safety and effectiveness of GAE relative to other knee OA treatments remains unclear. Finally, meta-regression analysis is subject to risks pertaining to ecological fallacy since inference about individuals is attempted using only study-level information. Consequently, readers are cautioned against drawing causal inference from the results of this study.

5. Conclusion

Limited evidence suggests that GAE is a safe procedure that is associated with improvement in knee OA symptoms, exceeding established MCID values. While an association between greater baseline knee pain and responsive to GAE was observed, this hypothesis warrants further study.

Author contributions

Conception and design: All authors. Analysis of data: L. Miller. Interpretation of data: B. Taslakian, L. Miller, T. Mabud. Drafting of the article: B. Taslakian, L. Miller, T. Mabud. Critical review of the article: All authors. Final approval of the article: All authors.

Role of the funding source

This work is supported by a research grant from Varian Medical, Inc. The funder was not involved in any aspect of this work including study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

L. Miller received research support from NYU Langone Health, related to the present manuscript. B. Taslakian received research support from Varian Medical Systems, related to the present manuscript.

W. Macauly discloses board membership with AAHKS, CORR, JoA, and Hip Society, and stock ownership of OrthAlign, unrelated to the present manuscript. A. Sista discloses grant payment from NIH, unrelated to the present manuscript. B. Taslakian discloses payment from Advarra for DSMB participation, unrelated to the present manuscript.

E. Alaia, M. Attur, R. Hickey, R. Kijowski, T. Mabud, and J. Samuels report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Fay, PhD for assistance with literature review and data extraction.

Handling Editor: H Madry

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2023.100342.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikeda K., Nakagomi D., Sanayama Y., Yamagata M., Okubo A., Iwamoto T., et al. Correlation of radiographic progression with the cumulative activity of synovitis estimated by power Doppler ultrasound in rheumatoid arthritis: difference between patients treated with methotrexate and those treated with biological agents. J. Rheumatol. 2013;40:1967–1976. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults--United States, 2005. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2009;58:421–426. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19407734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palazzo C., Ravaud J.F., Papelard A., Ravaud P., Poiraudeau S. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillon C.F., Rasch E.K., Gu Q., Hirsch R. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey 1991-94. J. Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271–2279. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17013996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford D.C., Miller L.E., Block J.E. Conservative management of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a flawed strategy? Orthop. Rev. 2013;5:e2. doi: 10.4081/or.2013.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawker G.A., Guan J., Croxford R., Coyte P.C., Glazier R.H., Harvey B.J., et al. A prospective population-based study of the predictors of undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3212–3220. doi: 10.1002/art.22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawker G.A., Wright J.G., Badley E.M., Coyte P.C. Perceptions of, and willingness to consider, total joint arthroplasty in a population-based cohort of individuals with disabling hip and knee arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:635–641. doi: 10.1002/art.20524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawker G.A., Wright J.G., Coyte P.C., Williams J.I., Harvey B., Glazier R., et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Med. Care. 2001;39:206–216. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsh J., Joshi I., Somerville L., Vasarhelyi E., Lanting B. Health care costs after total knee arthroplasty for satisfied and dissatisfied patients. Can. J. Surg. 2022;65:E562–E566. doi: 10.1503/cjs.006721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sideris A., Malahias M.A., Birch G., Zhong H., Rotundo V., Like B.J., et al. Identification of biological risk factors for persistent postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2022;47:161–166. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2021-102953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurien T., Kerslake R.W., Graven-Nielsen T., Arendt-Nielsen L., Auer D.P., Edwards K., et al. Chronic postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty: the potential contributions of synovitis, pain sensitization and pain catastrophizing-An explorative study. Eur. J. Pain. 2022;26:1979–1989. doi: 10.1002/ejp.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mapp P.I., Walsh D.A. Mechanisms and targets of angiogenesis and nerve growth in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012;8:390–398. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh D.A., Bonnet C.S., Turner E.L., Wilson D., Situ M., McWilliams D.F. Angiogenesis in the synovium and at the osteochondral junction in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:743–751. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohnsack M., Meier F., Walter G.F., Hurschler C., Schmolke S., Wirth C.J., et al. Distribution of substance-P nerves inside the infrapatellar fat pad and the adjacent synovial tissue: a neurohistological approach to anterior knee pain syndrome. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2005;125:592–597. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyu S.R., Chiang J.K., Tseng C.E. Medial plica in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a histomorphological study. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010;18:769–776. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0946-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuno Y., Korchi A.M., Shinjo T., Kato S., Kaneko T. Midterm clinical outcomes and MR imaging changes after transcatheter arterial embolization as a treatment for mild to moderate radiographic knee osteoarthritis resistant to conservative treatment. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2017;28:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sajan A., Mehta T., Griepp D.W., Chait A.R., Isaacson A., Bagla S. Comparison of minimally invasive procedures to treat knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2022;33:238–248 e234. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casadaban L.C., Mandell J.C., Epelboym Y. Genicular artery embolization for osteoarthritis related knee pain: a systematic review and qualitative analysis of clinical outcomes. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2021;44:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02687-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torkian P., Golzarian J., Chalian M., Clayton A., Rahimi-Dehgolan S., Tabibian E., et al. Osteoarthritis-related knee pain treated with genicular artery embolization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/23259671211021356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gotzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:W65–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institutes of Health. Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. [Accessed November 2, 2022].

- 23.Bellamy N., Buchanan W.W., Goldsmith C.H., Campbell J., Stitt L.W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J. Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3068365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGlothlin A.E., Lewis R.J. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312:1342–1343. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nwachukwu B.U., Chang B., Fields K., Rebolledo B.J., Nawabi D.H., Kelly B.T., et al. Defining the "substantial clinical benefit" after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017;45:1297–1303. doi: 10.1177/0363546516687541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Concoff A., Rosen J., Fu F., Bhandari M., Boyer K., Karlsson J., et al. A comparison of treatment effects for nonsurgical therapies and the minimum clinically important difference in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. JBJS Rev. 2019;7:e5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim M.S., Koh I.J., Choi K.Y., Sung Y.G., Park D.C., Lee H.J., et al. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the WOMAC and factors related to achievement of the MCID after medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy for knee osteoarthritis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021;49:2406–2415. doi: 10.1177/03635465211016853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston B.C., Patrick D.L., Thorlund K., Busse J.W., da Costa B.R., Schunemann H.J., et al. Patient-reported outcomes in meta-analyses-part 2: methods for improving interpretability for decision-makers. Health Qual. Life Outcome. 2013;11:211. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston B.C., Thorlund K., Schunemann H.J., Xie F., Murad M.H., Montori V.M., et al. Improving the interpretation of quality of life evidence in meta-analyses: the application of minimal important difference units. Health Qual. Life Outcome. 2010;8:116. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tierney J.F., Stewart L.A., Ghersi D., Burdett S., Sydes M.R. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagla S., Piechowiak R., Hartman T., Orlando J., Del Gaizo D., Isaacson A. Genicular artery embolization for the treatment of knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2020;31:1096–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2019.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagla S., Piechowiak R., Sajan A., Orlando J., Hartman T., Isaacson A. Multicenter randomized sham controlled study of genicular artery embolization for knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2022;33:2–10 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi J.W., Ro D.H., Chae H.D., Kim D.H., Lee M., Hur S., et al. The value of preprocedural MR imaging in genicular artery embolization for patients with osteoarthritic knee pain. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2020;31:2043–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landers S., Hely R., Page R., Maister N., Hely A., Harrison B., et al. Genicular artery embolization to improve pain and function in early-stage knee osteoarthritis-24-month pilot study results. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2020;31:1453–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S.H., Hwang J.H., Kim D.H., So Y.H., Park J., Cho S.B., et al. Clinical outcomes of transcatheter arterial embolisation for chronic knee pain: mild-to-moderate versus severe knee osteoarthritis. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2019;42:1530–1536. doi: 10.1007/s00270-019-02289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little M.W., Gibson M., Briggs J., Speirs A., Yoong P., Ariyanayagam T., et al. Genicular artEry embolizatioN in patiEnts with oSteoarthrItiS of the knee (GENESIS) using permanent microspheres: interim analysis. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2021;44:931–940. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02764-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padia S.A., Genshaft S., Blumstein G., Plotnik A., Kim G.H.J., Gilbert S.J., et al. Genicular artery embolization for the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. JB JS Open Access. 2021;6 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun C.H., Gao Z.L., Lin K., Yang H., Zhao C.Y., Lu R., et al. [Efficacy analysis of selective genicular artery embolization in the treatment of knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis] Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2022;102:795–800. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20210926-02166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fazeli M.S., McIntyre L., Huang Y., Chevalier X. Intra-articular placebo effect in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a survey of the current clinical evidence. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet Dis. 2022;14 doi: 10.1177/1759720X211066689. 1759720X211066689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.